Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a highly prevalent and genetically heterogeneous condition that results in decreased contractility and impaired cardiac function. The FK506-binding protein FKBP12 has been implicated in regulating the ryanodine receptor in skeletal muscle, but its role in cardiac muscle remains unclear. To define the effect of FKBP12 in cardiac function, we generated conditional mouse models of FKBP12 deficiency. We used Cre recombinase driven by either the α-myosin heavy chain, (αMHC) or muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter, which are expressed at embryonic day 9 (E9) and E13, respectively. Both conditional models showed an almost total loss of FKBP12 in adult hearts compared with control animals. However, only the early embryonic deletion of FKBP12 (αMHC-Cre) resulted in an early-onset and progressive DCM, increased cardiac oxidative stress, altered expression of proteins associated with cardiac remodeling and disease, and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak. Our findings indicate that FKBP12 deficiency during early development results in cardiac remodeling and altered expression of DCM-associated proteins that lead to progressive DCM in adult hearts, thus suggesting a major role for FKBP12 in embryonic cardiac muscle.

Introduction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) has an estimated prevalence in the human population from 1 in 250 to 1 in 2,500 and is characterized by extensive cardiac remodeling leading to left ventricular (LV) dilation, fibrosis, LV posterior and septal wall thinning, and decreased contractility (Hershberger et al., 2013; Weintraub et al., 2017; Reichart et al., 2019). Over 50 genetic variants are associated with DCM, encoding proteins in diverse cellular structures including sarcomeres, dystrophin complex, cytoskeleton, sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), nuclear envelop/nucleus, and mitochondria (McNally and Mestroni, 2017; Jordan et al., 2021). Ion channels and/or modulators of ion channels associated with DCM include RYR2 (Costa et al., 2021), CaV1.2 (Blaich et al., 2012), NaV1.5 (McNair et al., 2011; Moreau et al. 2015a, 2015b; Calloe et al., 2018), and junctophilin 2 (Jones et al., 2019). This genetic heterogeneity raises the important question (Towbin and Lorts, 2011) of whether there is a common and potentially targetable mechanism underlying DCM.

FK506 binding proteins (FKBP12 and FKBP12.6) are cis-trans prolyl isomerases that bind immunosuppressive drugs such as FK506 and rapamycin. In skeletal muscle, the primary role of FKBP12 is to stabilize the closed state of the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor, RYR1) to prevent SR Ca2+ leak (Brillantes et al., 1994). In cardiac tissue, FKBP12 binds to RYR2 with a KD of 200 nM and is expressed in mouse cardiac tissue at ∼1 µM, but only FKBP12.6 was found to inhibit RYR2 activity in permeabilized cardiomyocytes (Guo et al., 2010). While some studies have supported the lack of an effect of FKBP12 on RYR2 activity (Timerman et al., 1996; Guo et al., 2010), others have suggested that FKBP12 can either activate or inhibit RYR2 opening (Seidler et al., 2007; Galfré et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016; Asghari et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2023). Asghari et al. (2020) also found that FKBP12, FKBP12.6, and RYR2 phosphorylation together regulate RYR2 cluster size and tetramer formation in cardiomyocytes. These opposing findings underscore that the cardiac role of FKBP12 remains incompletely understood and merits further investigation.

In addition to the ex vivo studies described above, FKBP12 and FKBP12.6 levels have also been genetically manipulated in vivo. Fkbp1a knockout (KO) mice die during late embryonic development (E14.5) or after birth from heart and/or respiratory failure (Shou et al., 1998). These mice have severe cardiac defects including enlargement of the heart and outflow tracts, thinning of the left ventricular wall, increased ventricular trabeculation and noncompaction, and septal wall defects (Shou et al., 1998). Single-channel analyses of RYR2 isolated from the hearts of these Fkbp1a KO mice showed dramatic changes in single-channel gating behavior in planar lipid bilayers (Shou et al., 1998). The noncompaction and trabeculation ventricular septal defects in mouse hearts associated with FKBP12 deficiency partially arise from the loss of FKBP12 in cardiac endothelial cells since Tie2-Cre-LoxP directed ablation of FKBP12 mimics these aspects of the phenotype of the FKBP12 KO mice (Chen et al., 2013).

Unlike the Fkbp1a KO mice, mice with cardiomyocyte-specific αMHC-Cre-LoxP–mediated Fkbp1a deletion at ∼E9 survive to adulthood (Maruyama et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014), but cardiomyocytes from these mice display a large increase in Na+ currents without obvious cardiac defects (Li et al., 2012). In contrast, a novel chemical knockdown of FKBP12 in adult mice caused a decrease in cardiac function (ejection fraction, fractional shortening) and cardiac hypertrophy (Sun et al., 2019). In summary, the effect of FKBP12 on RYR2 activity, both in vitro and in vivo, remains controversial (Seidler et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2016; Asghari et al., 2020; Shou et al., 1998). Overexpression of FKBP12 (Maruyama et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2019) (αMyHC-Fkbp1a) in the heart led to a high incidence of sudden death (Maruyama et al., 2011), spontaneous atrial fibrillation, decreased sodium currents (INa), increased CaV1.2 protein levels, and increased Ca2+ current density (Pan et al., 2019). Possible explanations of these contradictory findings from different laboratories are differences in the level or timing of FKBP12 knockdown or over-expression and/or the efficacy and/or side-effects associated with the use of rapamycin and/or FK506 to remove FKBPs from RYRs.

In the current study, we compare two models of FKBP12 deficiency that differ in the timing of the decrease in FKBP12. We find that early, but not late, embryonic depletion of FKBP12 in cardiomyocytes induces a progressive, severe LV dilatation and systolic dysfunction that develops in the absence of any external stressors. Further differentiating these mouse models, we find elevation of oxidative stress, increase in SR Ca2+ leak, and upregulation of Ankyrin repeat domain 1 (ANKRD1), a critical stress response protein in the heart. These molecular changes were present in young mice before the development of DCM. These findings suggest a critical, cardiomyocyte-specific role for FKBP12 in early heart development that impacts adult heart function.

Materials and methods

Mice

All mouse studies were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Fkbp1a floxed mice were generated at BCM. B6.FVB-Tg (Myh6-cre) 2182Mds/J (MHC-Cre+) (Agah et al., 1997) were obtained from Dr. Michael Schneider while he was at BCM and were extensively backcrossed in our laboratory with C57BL/6J mice. The mice were maintained in a hemizygous state. B6.FVB(129S4)-Tg (Ckmm-cre) 5Khn/J (Brüning et al., 1998) (MCK-Cre+) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and were also extensively backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice prior to mating to Fkbp1a floxed mice (Lee et al., 2014) (FL). FKD mice (Fkbp1aloxP/loxP that express hemizygous MCK or MHC Cre+ recombinase) were routinely created by crossing male mice hemizygous Cre (MHC or MCK) mice with female Fkbp1aloxP/loxP mice. Fkbp1aloxP/loxP was frequently backcrossed with mice expressing MHC or MCK Cre-recombinase to refresh male FKD lines for mating. Both male and female mice were used in this study at the ages indicated. Age-matched hemizygous MHC-Cre+ and littermate FL mice were used as controls.

Materials

Liberase TH was purchased from Tocris Biosciences. The calcium dye Fluo 4 AM and the t-tubule marker FM4-64 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TGX Stain-free FastCast Acrylamide kit was purchased from Bio-Rad. A protease inhibitor cocktail and molecular weight marker for western blotting were purchased from GenDEPOT. Antibodies and dilutions used are listed in Table S1.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography on age- and sex-matched FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+, and MHC-FKD mice was performed using a VeVo 2100 Imaging System (VisualSonics) with a 40-MHz probe. Mice were initially anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane mixed with 100% O2 and placed on a heated pad where all four limbs were taped down onto surface electrodes for ECG monitoring. Anesthesia was maintained with 1.5% isoflurane through a nose cone. Body temperature was monitored with a rectal thermometer and maintained at 37 ± 1°C. Vevo LAB 5.7.1 software was used for echo data analysis.

Iodine-contrast microCT imaging

Iodine-contrast micro-CT imaging was performed following the protocol previously described (Hsu et al. 2016, 2019). Briefly, mouse neonates were collected at birth (P0) and euthanized by CO2. The samples were then immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for fixation at 4°C for 3 days. After fixation, the samples were further immersed in STABILITY buffer to prevent sample shrinkage and deformation. The samples were transferred to 50 ml conical tubes and immersed in 20 ml of STABILITY buffer (4% wt/vol paraformaldehyde, 4% wt/vol acrylamide, 0.05% wt/vol bis-acrylamide, 0.25% wt/vol VA044 initiator, 0.05% wt/vol Saponin in 1X PBS) and incubated at 4°C for 3 days allowing polymer diffusion through the samples. The crosslinking reaction was facilitated using the X-CLARITY hydrogel polymerization system (Logos Biosystem) under conditions at −90 kPa and 37°C for 3 h. Following this, the excess crosslinked polymer was removed completely, and samples were subjected to three washes in PBS for 1 h each, followed by an overnight wash at 4°C, and preserved in 1X PBS with 0.1% wt/vol sodium azide at 4°C until ready for imaging. For iodine contrasting, the samples were immersed in 0.1 N iodine solution for 7–10 days at room temperature. Prior to imaging, the samples were embedded in 1 % wt/vol agarose within a 6 ml transport tube (Cat# 89497-738; VWR). Back-projection images were acquired on Skyscan 1272 (Bruker). Each data set was acquired with the x-ray source set at 70 kV and 142 µA with a 0.5 mm aluminum attenuation filter. Each sample was rotated 180° along the anterior–posterior (AP) axis and a projection image at 2,016 × 1,344 pixels was generated every 0.3° at an average of three images. Acquired projection images were thus reconstructed utilizing the NRecon Reconstruction software (Version 1.7.4.2; Bruker). The reconstructed 3D data was rendered for volumetric visualization utilizing CTVox (Version 3.3.0; Bruker) or alternatively, 3D Slicer (Version 5.6.1; https://www.slicer.org), specifically in the coronal section plane to facilitate detailed morphological analysis of the neonates and cardiac structures.

Cardiomyocyte isolation

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from hearts of male age-matched FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+, and MHC-FKD mice using a gravity-fed Langendorff perfusion system. Hearts were removed from anesthetized mice and placed on a petri dish of frozen buffer. After removal of fat and other organs, hearts were cannulated and immediately perfused with warm, freshly made Myocyte Perfusion Buffer consisting of (in mM) 113 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, 22 D-glucose, 20 taurine, 5 Na-pyruvic acid, and 5 NaHCO3, pH 7.4. After the removal of blood, digestion was commenced by switching perfusion to Myocyte Digestion Buffer, consisting of Perfusion Buffer supplemented with 5 µg/μl Liberase TH, 10 mM BDM, and 0.1% BSA. Digestion of the heart was monitored using the perfusate drip rate and the texture of the heart. Once adequate digestion was achieved, ventricles were cut from the cannula and minced in myocyte stop buffer, consisting of perfusion buffer supplemented with 1% BSA and 20 µM CaCl2. Cardiomyocytes were isolated using sequential steps of gentle trituration and sedimentation in fresh Stop Buffer. Washes with the best myocyte viability were combined and underwent stepwise Ca2+ reintroduction until a final concentration of 1 mM was reached. Cardiomyocytes were plated on laminin-coated coverslips and submerged in Tyrodes buffer containing (in mM)140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 MgCl, 5 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 1.8 CaCl2; pH 7.4.

Ca2+ sparks in paced cardiomyocytes

Plated cardiomyocytes were loaded at room temperature for 30 min with 5 µM Fluo-4 AM dissolved in Tyrodes buffer. After a 30-min washout period, coverslips were inserted in a custom-made stimulation chamber connected to a MyoPacer Cell stimulator (IonOptix) and imaged on a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope with a 60× oil immersion objective. Fluo 4 was excited using an Argon 488 nm laser, and the emitted light was detected with a 505-nm long-pass filter. Quiescent myocytes were imaged in XT mode. After 30 s of 1 Hz pacing to establish steady-state conditions, a 30-s rest period was recorded for observation of spontaneous Ca2+ transients, Ca2+ waves, and Ca2+ sparks. Ca2+ sparks from the 20-s period after electrical stimulation were detected and analyzed in FIJI ImageJ using the Sparkmaster plugin (Picht et al., 2007). Ca2+ transient amplitude, rise time, and decay rate were measured in FIJI ImageJ using the Spikey plugin (Pasqualin et al., 2022) and in GraphPad Prism. Differences among the four groups were assessed with nested one-way ANOVAs. Some spontaneous Ca2+ wave data were determined using the IonOptix system (see Table S6).

Transverse-tubule (t-tubule) structure

To visualize t-tubules, cardiomyocytes were stained with the lipophilic styryl dye FM-4-64, as described previously (Lee et al., 2023). On the day of isolation, cardiomyocytes were plated on laminin-coated Mattek dishes and incubated at room temperature with 6.5 mM FM-4-64 for 10 min. XY images were obtained with a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscopy in Airyscan Super-Resolution mode. The FM-4-64 dye was excited at 561 nm and the emitted light >650 nM was captured with a long pass filter. T-tubule organization from the entire cardiomyocyte, excluding the external sarcolemmal membrane, was quantified using AutoTT (Guo and Song, 2014).

Western blotting

Hearts from FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+, and MHC-FKD mice at the ages and sex indicated were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Hearts in RIPA buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, were homogenized and lysed using a Precellys bead homogenizer (Bertin Instruments) Protein homogenates were treated with sulfhydryl alkylating reagent, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) at a final concentration of 5 mM and incubated for 30 min on ice. Protein concentrations were determined by BCA assay. 30–60 μg of proteins were mixed with SDS sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 6% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue, and 0.2 M 2-mercaptoethanol), denatured by boiling at 95°C for 3 min, and loaded on Bio-Rad Stain Free acrylamide gels for separation by SDS-PAGE before transfer to PVDF membrane (Immobilon-FL; Millipore). Membranes were blocked with EveryBlot blocking buffer (BioRad) and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with Starbright secondary antibodies (BioRad) for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were imaged on a Chemidoc MP system (BioRad) to visualize. Total protein and bands of interest were quantified by densitometry. Bands of interest were normalized to the total lane protein and expressed as a percentage of the average control (FL) value on the same blot.

OxyBlot

To determine the oxidative modification of proteins by oxygen free radicals and other reactive species during physiologic and pathologic processes, we performed OxyBlot following the manufacturer’s protocol (Cell Biolabs, Inc.). Hearts from FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+, and MHC-FKD mice were homogenized and lysed in RIPA buffer (Millipore Sigma) with bead homogenizer. After treating with 5 mM NEM (final concentration) on ice for 30 min, protein concentrations were measured by BCA assay. We used 60 μg of whole heart lysates for OxyBlot.

Immunoprecipitations

Hearts from FL, MHC-FKD, and MCK-FKD control mice were homogenized in six to eight volumes of IP buffer (wt/vol) (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4, 170 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40) including protease and phosphatase inhibitors using a bead homogenizer (Precellys tissue homogenizer). After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min, the cleared supernatant was incubated with primary antibodies and non-immunized IgG for 1 h (for RYR) and then overnight. After incubation with primary Ab, 40 μl of magnetic beads (Dynabeads Protein G; Invitrogen) were added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Magnetic beads were washed three times with IP buffer and twice with sterile PBS using a magnetic stand. Washed beads were trypsinized for MS/MS/PRM.

Mass spectrometry

Immunoaffinity purification followed by nanoHPLC-MS/MS analysis was used for interactome and PTM analysis as previously reported with minor modifications (Karki et al., 2021). Briefly, the affinity-purified protein and interacting proteins are digested on beads using Trypsin/Lys-C enzyme, and then the digested peptide is enriched and desalted by in-housed STAGE tip (Rappsilber et al., 2003) column with 2 mg of C18 beads (3 µm, Dr. Maisch GmbH) and vacuum-dried. Resuspended peptides are analyzed on nLC 1200 coupled with an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with an ESI source. The data acquisition is made in data-dependent analysis mode (DDA) for unbiased peptide detection, and targeted mass analysis (Parallel reaction monitoring, PRM) is used for selected target PTM sites for in-depth quantificational analysis. Obtained spectra are processed by the Proteome Discoverer 2.1 interface (PD 2.5; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the Mascot algorithm (Mascot 2.4; Matrix Science). Assigned peptides are filtered with a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) using percolator validation based on q-value. The calculated area under the curve of peptides was used to calculate iBAQ for protein abundance using in-housed software (Saltzman et al., 2018). The PTM sites were manually validated and quantified by Skyline Software. GraphPad Prism 10.3.1 was used for data analyses and figure generation. The mass spectrometry data for proteome profiling have been submitted via the MASSIVE repository (MSV0000 96593) to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) with the dataset identifier PXD058583. UCSD Computational Mass Spectrometry Website; https://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/user/login.jsp.

qRT-PCR

Fkbp1a 5′-GATTCCTCTCGGGACAGAAACA-3′ (forward)

Fkbp1a 5′-GACCCACACTCATCTGGGCTA-3′ (reverse)

Fkbp1b 5′-TGACCTGCACCCCTGATGT-3′ (forward)

Fkbp1b 5′-GGCATTGGGAGGGATGACAC-3′ (reverse)

Rn18s 5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′ (forward)

Rn18s 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′ (reverse).

RNA-seq

Isolated hearts were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) and cleared by centrifugation. For phase separation, 0.2 ml chloroform per 1 ml of TRIzol used for the initial homogenization was added to each tube. The tubes were capped securely, shaken by hand for around 15 s, and centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C. The aqueous phase containing RNA was carefully transferred into a new tube. To precipitate RNA, 0.5 ml isopropanol per 1 ml of TRIzol used for initial homogenization was added in each tube. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C. The total RNA forms a white gel-like pellet at the bottom of the tube. As a wash, 1 ml of 75% ethanol per 1 ml of TRIzol used for initial homogenization was added after discarding the supernatant. The samples were vortexed and centrifuged for 5 min at 7,500 × g and 4°C. The washing step was repeated twice with 75% ethanol. The final pellet was briefly dried via air exposure, resuspended in 20–50 µl RNase-free water, and/or incubated in 55–60°C for 10 min. Samples were sent to Azenta Life Sciences for library preparation with stranded polyA selection and HiSeq sequencing. Briefly, RNA samples were quantified using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies), and RNA integrity was checked using Agilent TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies). RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina following the manufacturer’s instructions (NEB). The samples were sequenced using a 2 × 150 bp paired-end (PE) configuration at 50 M reads on the Illumina instrument (4,000 or equivalent). Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from Illumina platform was converted into fastq files and demultiplexed using Illumina’s bcl2fastq 2.17 software. RNA-seq read quality from ACF samples were verified with FastQC (Simon Andrews, Babraham Institute, https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and MultiQC (Ewels et al., 2016). Quality and adapter trimming of the read ends was performed using Trim Galore (Felix Krueger, Babraham Institute, https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). Reads were mapped to the GRCm39 mouse reference genome using the STAR package, and transcripts were quantified as Ensembl gene IDs using the RSEM package (Li and Dewey, 2011; Dobin et al., 2013; Raney et al., 2024).

RNA-seq analysis

RNA-seq differential expression analysis on 24 whole-heart samples (6 each of FL; MHC-Cre+; MHC-FKD; and MCK-FKD) was performed in R using the EDASeq, limma, and edgeR packages (Robinson et al., 2010; Risso et al., 2011; McCarthy et al., 2012; Ritchie et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016). TRIM-Galore and FAST-QC were used for adapter trimming and quality control of raw fastq reads. STAR was used for read mapping to the reference genome and RSEM was used for transcript quantification using BAM files generated by STAR. The read count data were filtered for genes with at least 10 counts per million (CPM) in at least 12 samples with the sum of CPM for all 24 samples being at least 120. The batch was accounted for as an explanatory variable in the linear model. The data were normalized for sample library size using the weighted trimmed mean of M-values method and corrected for changes in variance across different mean CPMs using the Voom method (Law et al., 2014). For each of the five contrasts (MHC-FKD versus MHC-Cre+, MCK-FKD versus FL, MHC-Cre+ versus FL, MHC-FKD versus FL, and MHC-FKD versus MCK-FKD), the t-statistic and P value for each gene was determined by formulating the hypothesis tests with H0: |log2(fold change)| < log2(1.2) and Ha: |log2(fold change)| > log2(1.2). The output of the MHC-FKD versus Fl comparison was further analyzed with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (QIAGEN, Inc., https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/IPA) (Krämer et al., 2014). The 348 genes with (unadjusted) P value <0.05 (203 up and 145 down) were selected as the analysis-ready molecules. The raw P value and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P value were determined for Fisher’s exact test on the overlap between the set of analysis-ready genes and the set of genes in each toxicological function. Metadata, raw fastq files, and processed data were deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (NCBI). The GSE accession number for this manuscript is GSE262123.

Other statistical analyses

The number of repeats of each experiment was determined by Power calculations using preliminary data. The data shown are the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between the two groups were analyzed for significance using Student’s t tests. If the data failed normality tests, we performed a Mann–Whitney rank sum test. Differences between means of multiple groups were analyzed by one or two-way ANOVA and those with multiple individual myofibers per subject by nested (hierarchical) ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc tests. Mean differences between groups for longitudinal measurements as a function of age were analyzed by repeated measure ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests. Values of P < 0.05 (95% confidence) are considered statistically significant (unless otherwise indicated). Proteomic data were analyzed as previously described (Lee et al., 2023).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the percentage of cells per mouse that display spontaneous SCW in the absence of stimulation (Fig. S1 A) and during electrical stimulation (Fig. S2 B), examples of fast SCW (Fig. S1 C), slow SCW (Fig. S1 D) Ca2+ sparks (Fig. S1 E) and rare long Ca2+ sparks (Fig. S1 F). Fig. S2 shows the RNA-seq data for MHC-FKD compared with either MHC-Cre+ or MCK-FKD. Table S1 lists all antibodies used. Tables S2, S3, S4, and S5 provide the values for the echo parameters for 3- and 6-mo-old male and female mice, respectively, as mean ± SD. Table S6 provides the distribution of SCWs per mouse. Table S7 provides CT data as mean ± SD.

Results

Generation of mice with cardiac-specific deficiencies of FKBP12

Homozygous FKBP12 KO mice die at a late embryonic stage (Shou et al., 1998) and the phenotype is at least partially due to a role for FKBP12 in endothelial cells (Pan et al., 2019). To define the role of FKBP12 in cardiomyocytes, we created cardiomyocyte-specific FKBP12-deficient mice (FKD) using a Cre recombinase under the control of the α-myosin heavy chain (MHC) promoter crossed with Fkbp1aloxP/loxP (FL) mice (designated MHC-FKD). Cre recombinase under the control of the MHC promoter drives recombination only in the myocardium beginning at E9 and expresses in most cardiomyocytes by E11.5 (Zhang et al., 2020). We also created a second FKBP12 deficient mouse with FL mice and Cre recombinase under the control of the muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter (designated MCK-FKD). MCK-Cre+ recombinase expression in skeletal and cardiac muscle begins between E13 and birth (Mobley et al., 2020). We used both Fkbp1a floxed mice and hemizygous MHC-Cre+ mice as controls.

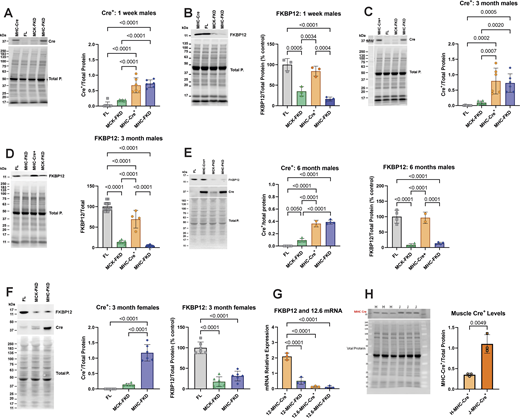

We examined the levels of both Cre+ recombinase and FKBP12 in cardiac homogenates from male mice at three ages: 1 wk, 3 mo, and 6 mo Cre+ recombinase levels were normalized to total protein rather than percentage control. FKBP12 levels were normalized to total protein and then plotted as percentage control (FL) to designate the extent of knockdown. Western blots and analyses of the Cre+ and FKBP12 expression in male mice are shown at 1 wk (Fig. 1, A and B), 3 mo (Fig. 1, C and D), and 6 mo (Fig. 1 E). FKBP12 levels were reduced to similar levels in all age groups, but FKBP12 levels in MCK-FKD mice are higher at 1 wk of age than at older ages. The levels of FKBP12 are not significantly different between MHC-FKD and MCK-FKD at 3- or 6-mo-old mice. Hearts of female mice show similar differences in Cre+ and FKBP12 at 3 mo of age and the extent of decrease in FKBP12 is not different between MHC-FKD and MCK-FKD (Fig. 1 F). Because FKBP12.6 has been shown to stabilize a closed state of RYR2 (Guo et al., 2010), we also used RT-PCR to determine if FKBP12.6 message levels were altered in the hearts of these mice. Fig. 1 G shows that the mRNA levels for FKBP12 were reduced but the mRNA for FKBP12.6 was not altered in the hearts of the MHC-FKD mice.

Cardiac Cre-recombinase and FKBP12 levels. (A) Cre+ levels in hearts from 1-wk-old male mice (n = 6 for each genotype). (B) FKBP12 levels in hearts from 1-wk-old male mice (n = 3). (C) Cre+ levels in hearts from 3-mo-old male mice (n = 6 for each genotype). (D) FKBP12 levels in hearts from 3-mo-old male mice (n = 14, 7, 4, and 14 for FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+, and MHC-FKD, respectively). (E) Cre+ levels and FKBP12 levels in hearts from 6-mo-old-male mice. (n = 4 for FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD, n = 2 for MHC-Cre+ only). (F) Cre+ levels and FKBP12 levels in hearts from 3-mo-old female mice (n = 6 for FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD. (G) Relative mRNA levels for FKBP12 and FKBP12.6 in MHC-Cre+ and MHC-FKD mice. (n = 3 for each). (H) MHC-Cre+ per total proteins in hearts of hemizygous MHC-Cre+ mice from Hamilton lab (H-MHC-Cre+) versus hemizygous mice from Jackson Laboratories (B6.FVB-g(Myh6-cre)2182Mds/J, which we designate J-MHC-Cre+), n = 3, 3-mo-old. In all panels, the levels of proteins were assessed by western blotting with representative western blots shown at the left in each panel. Proteins of interest were normalized to the total protein level in the same lane, normalized to the average expression level in FL hearts and expressed as %FL. Data were analyzed with one-way ANOVAs and P values indicated. Data are plotted as the mean ± SD. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Cardiac Cre-recombinase and FKBP12 levels. (A) Cre+ levels in hearts from 1-wk-old male mice (n = 6 for each genotype). (B) FKBP12 levels in hearts from 1-wk-old male mice (n = 3). (C) Cre+ levels in hearts from 3-mo-old male mice (n = 6 for each genotype). (D) FKBP12 levels in hearts from 3-mo-old male mice (n = 14, 7, 4, and 14 for FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+, and MHC-FKD, respectively). (E) Cre+ levels and FKBP12 levels in hearts from 6-mo-old-male mice. (n = 4 for FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD, n = 2 for MHC-Cre+ only). (F) Cre+ levels and FKBP12 levels in hearts from 3-mo-old female mice (n = 6 for FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD. (G) Relative mRNA levels for FKBP12 and FKBP12.6 in MHC-Cre+ and MHC-FKD mice. (n = 3 for each). (H) MHC-Cre+ per total proteins in hearts of hemizygous MHC-Cre+ mice from Hamilton lab (H-MHC-Cre+) versus hemizygous mice from Jackson Laboratories (B6.FVB-g(Myh6-cre)2182Mds/J, which we designate J-MHC-Cre+), n = 3, 3-mo-old. In all panels, the levels of proteins were assessed by western blotting with representative western blots shown at the left in each panel. Proteins of interest were normalized to the total protein level in the same lane, normalized to the average expression level in FL hearts and expressed as %FL. Data were analyzed with one-way ANOVAs and P values indicated. Data are plotted as the mean ± SD. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

We included MHC-Cre+ mice as controls in our functional studies because MHC-Cre+ expression alone can cause cytotoxicity in older mice (Pugach et al., 2015; Gillet et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023). Our MHC-Cre+ mice are from the same original strain (Agah et al., 1997) as those available from Jackson Laboratories and used for the Cre+ cytotoxicity studies. However, we have not detected cytotoxicity even in 1-year-old MHC-Cre+ mice. Our MHC-Cre+ mice have been extensively backcrossed for >10 years in our laboratory and maintained as a hemizygous colony. To determine why our mice were not showing the same phenotype as reported in other laboratories (Pugach et al., 2015; Gillet et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023), we compared Cre+ expression in hearts of our colony of MHC-Cre+ mice with those obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Both mice were hemizygous for the Cre+ but the MHC-Cre+ levels were higher (∼3×) in the hearts of the MHC-Cre+ mice directly from Jackson Laboratories compared with ours (Fig. 1 H). All echo values are summarized in Tables S2, S3, S4, and S5.

In summary, Fig. 1 demonstrates that FKBP12 deficiency begins at different times in the MHC-FKD mice, but by 6 mo of age hearts of both MCK-FKD and MHC-FKD mice had similar FKBP12 decreases. We also demonstrate that not all MHC-Cre+ mice, even derived from the same original strain, are equal with respect to the levels of MHC-Cre+ expression.

The phenotypes of the FKBP12 deficient mice

Only MHC-Cre+ driven FKBP12 deficiency negatively impacts cardiac function

To assess the effects of FKBP12 deficiency on cardiac function in adult mice, we performed echocardiography on male (Fig. 2, A–H) and female (Fig. 2, I–P) mice at 3 and 6 mo of age. MHC-FKD male and female mice are beginning to display signs of DCM at 3 mo with a decreased ejection fraction (Fig. 2, A and I, not significant in females), decreased fractional shortening (Fig. 2, B and J, not significant in females), and increased left ventricular interior diameter (LVIDd) (Fig. 2, C and K) with no difference in left ventricular anterior wall thickness (LVAWs) (Fig. 2, D and L) when compared with FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-Cre+ only male and female mice, respectively. At 6 mo of age, the DCM has worsened based on EF (Fig. 2, E and M), FS (Fig. 2, F and N), LVIDd (Fig. 2, G and O), and LVAWs (Fig. 2, H and P). No cardiac defects were detected in FL or MHC-Cre+ only male or female mice at 3 or 6 mo of age, possibly due to the presence of FKBP12 during a critical embryonic stage (E9–13). Because the phenotype of the female MHC-FKD mice is similar but milder than the male mice, we concentrated our studies on male mice.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on cardiac function in male and female mice. (A, E, I, and M) Ejection fraction (EF) for 3-mo-old male, 6-mo-old male, 3-mo-old female, and 6-mo-old female mice, respectively. (B, F, J, and N) Fractional shortening (FS) for 3-mo-old male, 6-mo-old male, 3-mo-old female, and 6-mo-old female mice, respectively. (C, G, K, and O) Left ventricular interior dimension in diastole (LVIDd) for 3-mo-old male, 6-mo-old male, 3-mo-old female, and 6-mo-old female mice, respectively. (D, H, L, and P) Left ventricular anterior wall thickness during systole (LVAWs) for 3-mo-old male, 6-mo-old male, 3-mo-old female, and 6-mo-old female mice, respectively. 3-mo-old male mice: n = 13 for FL, n = 7 for MCK-FKD, n = 15 for MHC-Cre+, and n = 17 for MHC-FKD. For 6-mo-old male mice: n = 11 for FL, n = 8 for MCK-FKD, n = 8 for MHC-Cre+, and n = 7 for MHC-FKD. For 3-mo-old female mice: n = 16 for FL, n = 10 for MCK-FKD, n = 13 for MHC-Cre+, and n = 13 for MHC-FKD. For 6-mo-old female mice: n = 10 for FL, n = 5 for MCK-FKD, n = 10 for MHC-Cre+, and n = 14 for MHC-FKD. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs and P value indicated. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on cardiac function in male and female mice. (A, E, I, and M) Ejection fraction (EF) for 3-mo-old male, 6-mo-old male, 3-mo-old female, and 6-mo-old female mice, respectively. (B, F, J, and N) Fractional shortening (FS) for 3-mo-old male, 6-mo-old male, 3-mo-old female, and 6-mo-old female mice, respectively. (C, G, K, and O) Left ventricular interior dimension in diastole (LVIDd) for 3-mo-old male, 6-mo-old male, 3-mo-old female, and 6-mo-old female mice, respectively. (D, H, L, and P) Left ventricular anterior wall thickness during systole (LVAWs) for 3-mo-old male, 6-mo-old male, 3-mo-old female, and 6-mo-old female mice, respectively. 3-mo-old male mice: n = 13 for FL, n = 7 for MCK-FKD, n = 15 for MHC-Cre+, and n = 17 for MHC-FKD. For 6-mo-old male mice: n = 11 for FL, n = 8 for MCK-FKD, n = 8 for MHC-Cre+, and n = 7 for MHC-FKD. For 3-mo-old female mice: n = 16 for FL, n = 10 for MCK-FKD, n = 13 for MHC-Cre+, and n = 13 for MHC-FKD. For 6-mo-old female mice: n = 10 for FL, n = 5 for MCK-FKD, n = 10 for MHC-Cre+, and n = 14 for MHC-FKD. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs and P value indicated. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

In summary, Fig. 2 shows that both male and female MHC-FKD, but not the MCK-FKD mice, display a DCM that progresses in severity with age.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on cardiomyocyte Ca2+ handling

FKBP12 deficiency increases spontaneous Ca2+ release in intact cardiomyocytes only from the MHC-FKD mice

To determine if RYR2 function in cardiomyocytes isolated from adult mice is altered by FKBP12 deficiency, we loaded quiescent cardiomyocytes isolated from 10- to 12-wk-old age-matched and/or littermate male MHC-Cre+, FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD mice with Fluo-4 AM. The cardiomyocytes were paced at 1 Hz for 30 s to attain steady-state Ca2+ transients and resting activity was recorded for an additional 30 s to identify spontaneous Ca2+ release events. Representative Ca2+ transients are shown in Fig. 3 A. Neither the amplitudes (Fig. 3 B), the time to peak (Fig. 3 C), nor decay rates (Fig. 3 D) of the Ca2+ transients were significantly different among the cardiomyocytes from mice of different genotypes, but spontaneous Ca2+ waves (SCW, analyzed in the first 20 s after cessation of electrical pacing) were detected at a higher frequency in cardiomyocytes from the MHC-FKD mice than in cardiomyocytes from FL and MCK-FKD mice (Fig. 3, A and E). We did not find a significant difference in the number of SCW in resting myocytes (Fig. S1 A and Table S6) or during stimulation (Fig. S1 B and Table S6). In assessing SCWs, we detected very fast, high amplitude events that we designate as spontaneous Ca2+ transients (Fig. 3, A and F; and Fig. S1 C), and smaller and slower Ca2+ waves (Fig. 3 G and Fig. S1 D). We did not detect significant differences in spontaneous Ca2+ transient or Ca2+ wave velocities among cardiomyocytes of the four genotypes of mice (Fig. 3, F and G). 64% of the spontaneous events in the MHC-FKD fibers were fast spontaneous transients. The lack of an effect of FKBP12 deficiency on the rate of return to baseline in voltage-activated Ca2+ transients suggests that SERCA activity was not altered. Caffeine-induced transients were not different, suggesting that SR Ca2+ stores have not changed (Fig. 3 H). Although there is a trend toward an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ in the cardiomyocytes from the MHC-FKD mice, this was not significant (Fig. 3 I). We also evaluated the occurrence of Ca2+ sparks. We detected an increase in the Ca2+ spark frequency (Fig. 3 J, representative sparks shown in Fig. S1 E) and spark amplitude (Fig. 3 K) in cardiomyocytes from the MHC-FKD mice. While other parameters (Fig. 3, L–P) such as time-to-peak (TtP), rate of decay (tau), full-width half maximal (FWHM), full-duration half maximal (FDHM), and spark mass were not different, we did occasionally detect long duration Ca2+ sparks (Fig. 3, L and P, representative image shown in Fig. S1 F). Given the similar decreases in FKBP12 in hearts of MHC-FKD and MCK-FKD mice at 3- and 6-mo-of age, the increase in Ca2+ spark frequency in cardiomyocytes only from the MHC-FKD mice suggests that the absence of FKBP12 alone is not causing SR Ca2+ leak. Instead, our data suggest that the absence of FKBP12 during a critical embryonic stage and subsequent changes, such as cardiac remodeling, are also required to cause increased SR Ca2+ leak in adult cardiomyocytes.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on Ca 2+ handling. (A) Representative Ca2+ transients in FL (top, black) and MHC-FKD (bottom, blue) cardiomyocytes. 1 Hz stimulation (E.S.) and spontaneous Ca2+ waves (SCW) are indicated with arrows. (B) Average amplitude with 1 Hz stimulation. (C) Time to the peak of the Ca2+ transient. (D) Rate of decay of the Ca2+ transient. (E) Percent of fibers per mouse with spontaneous Ca2+ transients or waves (SCW) occurring after electrical stimulation. (F) Velocity of the fast spontaneous Ca2+ transients. (G) Velocity of slow Ca2+ waves. (H) Caffeine-induced transients. FL: n = 4 mice, 13 cardiomyocytes, MHC-FKD: 5 mice, 11 cardiomyocytes, MHC-FKD: n = 4 mice, 14 cardiomyocytes. (I) Cytosolic Ca2+ levels were assessed with Fura 2. FL: n = 4 mice, 20 cardiomyocytes, MCK-FKD: n = 4 mice, 15 myocytes, MHC-FKD, n = 3 mice, 21 cardiomyocytes. (I and J) Ca2+ spark frequency. (K) Ca2+ spark amplitude. (L) Time to peak. (M) Decay rate (Tau). (N) Full-width half maximum (FWHM). (O) Full-duration half maximum (FDHM). (P) Calculated spark mass. Ca2+ transient and spark data: FL, n = 6 mice, 42 cardiomyocytes. MCK-FKD, n = 5 mice, 42 cardiomyocytes. MHC-Cre+, n = 5, 36 cardiomyocytes. MHC-FKD, n = 6 mice, 47 cardiomyocytes. Data were analyzed by a nested one-way ANOVA. Data were obtained from cardiomyocytes from male mice.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on Ca 2+ handling. (A) Representative Ca2+ transients in FL (top, black) and MHC-FKD (bottom, blue) cardiomyocytes. 1 Hz stimulation (E.S.) and spontaneous Ca2+ waves (SCW) are indicated with arrows. (B) Average amplitude with 1 Hz stimulation. (C) Time to the peak of the Ca2+ transient. (D) Rate of decay of the Ca2+ transient. (E) Percent of fibers per mouse with spontaneous Ca2+ transients or waves (SCW) occurring after electrical stimulation. (F) Velocity of the fast spontaneous Ca2+ transients. (G) Velocity of slow Ca2+ waves. (H) Caffeine-induced transients. FL: n = 4 mice, 13 cardiomyocytes, MHC-FKD: 5 mice, 11 cardiomyocytes, MHC-FKD: n = 4 mice, 14 cardiomyocytes. (I) Cytosolic Ca2+ levels were assessed with Fura 2. FL: n = 4 mice, 20 cardiomyocytes, MCK-FKD: n = 4 mice, 15 myocytes, MHC-FKD, n = 3 mice, 21 cardiomyocytes. (I and J) Ca2+ spark frequency. (K) Ca2+ spark amplitude. (L) Time to peak. (M) Decay rate (Tau). (N) Full-width half maximum (FWHM). (O) Full-duration half maximum (FDHM). (P) Calculated spark mass. Ca2+ transient and spark data: FL, n = 6 mice, 42 cardiomyocytes. MCK-FKD, n = 5 mice, 42 cardiomyocytes. MHC-Cre+, n = 5, 36 cardiomyocytes. MHC-FKD, n = 6 mice, 47 cardiomyocytes. Data were analyzed by a nested one-way ANOVA. Data were obtained from cardiomyocytes from male mice.

SCW without or before stimulation and during stimulation. (A and B) The percentage of fibers per mouse displaying SCW without or before stimulation (A) and during stimulation (between transients) (B). (C) Representative spontaneous Ca2+ transient after the stimulation. (D) Representative slow Ca2+ wave after stimulation. Representative long duration Ca2+ sparks after 1 Hz pacing. (E) Representative Ca2+ sparks were detected in the 20-s period after 1 Hz pacing of cardiomyocytes. (F) Representative long duration Ca2+ sparks after 1 Hz pacing. Scale bars are 1 s.

SCW without or before stimulation and during stimulation. (A and B) The percentage of fibers per mouse displaying SCW without or before stimulation (A) and during stimulation (between transients) (B). (C) Representative spontaneous Ca2+ transient after the stimulation. (D) Representative slow Ca2+ wave after stimulation. Representative long duration Ca2+ sparks after 1 Hz pacing. (E) Representative Ca2+ sparks were detected in the 20-s period after 1 Hz pacing of cardiomyocytes. (F) Representative long duration Ca2+ sparks after 1 Hz pacing. Scale bars are 1 s.

In summary, Fig. 3 shows that cardiomyocytes from the MHC-FKD, but not the MCK-FKD mice displayed a small, but significant increase in Ca2+ spark frequency with no change in the amplitude or kinetics of the Ca2+ transient or the levels of the SR Ca2+ stores, suggesting that the SR Ca2+ leak is compensated for by increased Ca2+ uptake into to the SR and/or increased extrusion of Ca2+ from the cardiomyocyte.

Underlying mechanisms for SR Ca2+ leak: The process of elimination

The lack of a phenotype in the MCK-FKD mice, despite a similar decrease in FKBP12 in adult hearts, suggests that FKBP12 plays an important role in embryonic heart development. If this is true, the impact of embryonic MHC-Cre+-driven FKBP12 deficiency (DCM and SR Ca2+ leak) manifests in adult hearts. This raises the critical question of what, if not the removal of FKBP12 from RYR2, causes SR Ca2+ leak in cardiomyocytes from the MHC-FKD mice. We considered and tested several possibilities including disrupted t-tubules, changes in the expression of ECC proteins, alterations in RYR2 binding proteins, and/or phosphorylation and oxidative stress.

T-tubule structure

T-tubule disruption has been shown to cause the appearance of Ca2+ sparks (Reynolds et al., 2016; Dibb et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). To assess the effects of decreasing FKBP12 on t-tubule architecture/integrity, we stained intact cardiomyocytes with the membrane marker FM4-64 (Fig. 4 A). We detected a decrease in t-tubule regularity in both models of FKBP12 deficiency (Fig. 4 B), suggesting that FKBP12 may be an important cofactor in t-tubule stability and/or structure. However, despite trends in spark amplitude (Fig. 3 K), no other spark parameter was statistically significantly different. We found no differences in the density of t-tubule elements or the sarcomere spacing among any of the groups tested (Fig. 4). T-tubule changes in the MCK-FKD cardiomyocytes, however, did not cause spontaneous Ca2+ release or later development of DCM.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on t-tubule structure. (A) FM-4-64-stained t-tubules in cardiomyocytes from hearts of FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD mice. (B–E) (B) Sarcomere spacing, (C) T-tubule regularity, (D) LE density, and (E) T-tubule integrity were analyzed using AutoTT (Guo and Song, 2014). Three male mice of each genotype were used for this study and a total of 23, 26, and 18 cardiomyocytes of the FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD mice. Data were analyzed with nested one-way ANOVAs with P values provided. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on t-tubule structure. (A) FM-4-64-stained t-tubules in cardiomyocytes from hearts of FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD mice. (B–E) (B) Sarcomere spacing, (C) T-tubule regularity, (D) LE density, and (E) T-tubule integrity were analyzed using AutoTT (Guo and Song, 2014). Three male mice of each genotype were used for this study and a total of 23, 26, and 18 cardiomyocytes of the FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD mice. Data were analyzed with nested one-way ANOVAs with P values provided. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Excitation–contraction coupling (ECC) proteins

SR Ca2+ leak in the cardiomyocytes could arise from alterations in the expression of proteins other than FKBP12 that modulate RYR2 activity. We evaluated the effects of FKBP12 deficiency on the expression of various ECC proteins. We found a significant decrease in the α1 subunit of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (CACNA1c, CaV1.2, also known as the dihydropyridine receptor, DHPR) in the hearts of adult MHC-FKD mice, but not the MCK-FKD mice (Fig. 5 A). There were no significant changes in levels of RYR2 (Fig. 5 B), p-2807 phosphorylation of RYR2 (Fig. 5 C), calsequestrin 2 (Fig. 5 D), or SERCA2a (Fig. 5 E) in either the MCK-FKD or the MHC-FKD mice compared with controls (FL, MHC-Cre+ only). We also detected a small but significant decrease in junctophilin 2 (JPH2) in the MHC FKD mice (Fig. 5 F, solid arrowhead). This may be secondary to SR Ca2+ leak and calpain activation since we also detected an increase in a 91 kDa JPH2 fragment (Fig. 5 F, open arrowhead) that is recognized by an antibody against amino acids (aa 565–580) in the C-terminus of JPH2 (Lee et al., 2023). Striated muscle preferentially expressed protein kinases, SPEGα and SPEGβ, regulate t-tubule structure and stabilize a closed state of RYR2 (Quick et al., 2017; Campbell et al., 2021). We have shown that both SPEG isoforms localize to dyads and triads in cardiac and skeletal muscle, respectively (Lee et al., 2023). Both SPEGα and SPEGβ levels were increased in the hearts of the MHC-FKD, but not MCK-FKD mice (Fig. 5 G). An upregulation of SPEG only in the MHC-FKD mice which display SR Ca2+ leak may represent a compensatory mechanism to attempt to decrease the Ca2+ leak in these mice. We also used oxyblots to assess relative levels of oxidative stress in each of the mouse models. As can be seen in Fig. 5 H, oxidative stress was highest in the MHC-FKD. It is, however, important to note that oxidative stress could arise from the SR Ca2+ leak (Santulli et al., 2015) or be the cause of the SR Ca2+ leak (Terentyev et al., 2008; Matecki et al., 2016; Gonzalez et al., 2014; Oda et al., 2015; Bovo et al., 2018).

Expression of ECC proteins. (A) 12-wk-old male hearts from FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-FKD and MHC-Cre mice were examined for (A) CaV1.2 expression. FL, n = 12, MCK-FKD, n = 12, MHC-Cre+, n = 8, MHC-FKD, n = 7. (B) Total RYR2 expression, FL, n = 16, MCK-FKD, n = 11, MHC-Cre+, n = 8, MHC-FKD, n = 13. (C) Phosphorylated RYR2 at S2807 FL, n = 8, MCK-FKD, n = 8, MHC-Cre+, n = 8, MHC-FKD, n = 6. (D) CASQ2 expression. FL, n = 16, MCK-FKD, n = 11, MHC-Cre+, n = 8, MHC-FKD, n = 14. (E) SERCA2a FL, n = 6, MCK-FKD, n = 6, MHC-Cre+, n = 6, MHC-FKD, n = 6. (F) Full-length JPH2 and its fragment expression FL, n = 21, MCK-FKD, n = 16, MHC-Cre+, n = 13, MHC-FKD, n = 18. (G) SPEG expression, FL, n = 17, MCK-FKD, n = 22, MHC-Cre+, n = 17, MHC-FKD, n = 20. (H) Oxyblot on cardiac homogenates from MHC-Cre+, FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD mice. (n = 6 for each group). Proteins of interest were normalized to the total protein level in the same lane, normalized to the average expression level in FL hearts, and expressed as %FL. Each band was analyzed. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs. P values are indicated. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Expression of ECC proteins. (A) 12-wk-old male hearts from FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-FKD and MHC-Cre mice were examined for (A) CaV1.2 expression. FL, n = 12, MCK-FKD, n = 12, MHC-Cre+, n = 8, MHC-FKD, n = 7. (B) Total RYR2 expression, FL, n = 16, MCK-FKD, n = 11, MHC-Cre+, n = 8, MHC-FKD, n = 13. (C) Phosphorylated RYR2 at S2807 FL, n = 8, MCK-FKD, n = 8, MHC-Cre+, n = 8, MHC-FKD, n = 6. (D) CASQ2 expression. FL, n = 16, MCK-FKD, n = 11, MHC-Cre+, n = 8, MHC-FKD, n = 14. (E) SERCA2a FL, n = 6, MCK-FKD, n = 6, MHC-Cre+, n = 6, MHC-FKD, n = 6. (F) Full-length JPH2 and its fragment expression FL, n = 21, MCK-FKD, n = 16, MHC-Cre+, n = 13, MHC-FKD, n = 18. (G) SPEG expression, FL, n = 17, MCK-FKD, n = 22, MHC-Cre+, n = 17, MHC-FKD, n = 20. (H) Oxyblot on cardiac homogenates from MHC-Cre+, FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD mice. (n = 6 for each group). Proteins of interest were normalized to the total protein level in the same lane, normalized to the average expression level in FL hearts, and expressed as %FL. Each band was analyzed. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs. P values are indicated. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

In summary, Fig. 5 shows that FKBP12 deficiency beginning during early embryonic development leads to decreases in CaV1.2α1c and JPH2, increases in proteolytic cleavage of JPH2, increases in the expression of SPEGα and SPEGβ, and increased oxidative stress. However, we detected no apparent changes in RYR2 phosphorylation at S2807.

JPH2 and RYR2 binding interactions

To further evaluate the effects of FKBP12 deficiency on interactions among dyadic proteins, we immunoprecipitated (IP) JPH2 and RYR2 from cardiac homogenates from FL, MCK-, and MHC-FKD mice. We chose JPH2 rather than RYR2 based on previous experience that antibodies to JPH2 give a cleaner and higher yield IPs (Lee et al., 2023). We previously used a Bio-ID approach with BirA-FKBP12 to demonstrate that JPH2 is in close proximity to the FKBP12 binding site on RYR1 in skeletal muscle (Lee et al., 2023). Specific proteins were identified in the JPH2 IPs from all three genotypes including (Fig. 6, A–C) JPH2, CASQ2, SPEG, RYR2, CACNA1c (CaV1.2), CACNB2 (voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit β-2), CACNB3 (voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit β-3), ESD (esterase D), CMYA5 (cardiomyopathy-associated protein 5, myospryn), and LRRC10 (leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 10). FKBP12.6 showed variable recovery and low levels in the JPH2 IP. We did not detect any significant differences among these proteins immunoprecipitated from the hearts of the three groups, suggesting that the removal of FKBP12 from the ECC complex is not greatly altering JPH2 interaction. We also immunoprecipitated RYR2 from the hearts of FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD. These immunoprecipitations were not as clean as the JPH2 IP, but several proteins were identified including RYR2, JPH2, SPEG, CAMKIIδ, FKBP12.6, phospholamban, and BCO48546. While none of these were significantly different among the RYR2 IPs from the three genotypes, there was a trend toward an increase in the FKBP12.6 associated with RYR2 in the hearts of MHC-FKD mice (Fig. 6 G). Using parallel reaction monitoring on some of these immunoprecipitates, we found no difference in the phosphorylation of either S2367/8 (Fig. 6 H), a putative target of SPEG (Campbell et al., 2020), or S2807 (Fig. 6 I), a putative target of PKA and CAMKIIδ (Guo et al., 2010). Hence, a deficiency in FKBP12 does not appear to alter RYR2 phosphorylation at these sites. It should be noted that calmodulin is not significantly immunoprecipitated with RYR2 or JPH2 under these conditions.

Immunoprecipitation of JPH2 and RYR2 from hearts of FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+ and MHC-FKD. JPH2 and RYR2 were immunoprecipitated from hearts of FL, MCK-FKD and MHC-FKD mice using procedures we have previously described (Lee et al., 2023). Proteins in the IP were identified by mass spectrometry. (A) Volcano plot of the JPH2 binding proteins from the hearts of FL mice. (B) A volcano plot of the JPH2 binding proteins from the hearts of MCK-FKD mice. (C) A volcano plot of the JPH2 binding proteins from the hearts of MHC-FKD mice. (D) Volcano plot of the RYR2 binding proteins from the hearts of FL mice. (E) Volcano plot of the RYR2 binding proteins from the hearts of MCK-FKD mice. (F) Volcano plot of the RYR2 binding proteins from the hearts of MHC-FKD mice. (G) Normalized FKBP12.6 in RYR2 IPs. (H) Phosphorylation of RYR2 from PRM at the SPEG phosphorylation site. In these studies, we could not distinguish between phosphorylation at S2367 and S2368. (I) Phosphorylation of RYR2 by PRM at the PKA phosphorylation site (S2807). No differences were detected among FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD in either the JPH2 or RYR2 IPs. JPH2 IPs: n = 11 for each genotype. RYR2 IPs, FL, n = 7, MCK-FKD, n = 10, MHC-FKD, n = 10. Data in G–I are shown as mean ± SD.

Immunoprecipitation of JPH2 and RYR2 from hearts of FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+ and MHC-FKD. JPH2 and RYR2 were immunoprecipitated from hearts of FL, MCK-FKD and MHC-FKD mice using procedures we have previously described (Lee et al., 2023). Proteins in the IP were identified by mass spectrometry. (A) Volcano plot of the JPH2 binding proteins from the hearts of FL mice. (B) A volcano plot of the JPH2 binding proteins from the hearts of MCK-FKD mice. (C) A volcano plot of the JPH2 binding proteins from the hearts of MHC-FKD mice. (D) Volcano plot of the RYR2 binding proteins from the hearts of FL mice. (E) Volcano plot of the RYR2 binding proteins from the hearts of MCK-FKD mice. (F) Volcano plot of the RYR2 binding proteins from the hearts of MHC-FKD mice. (G) Normalized FKBP12.6 in RYR2 IPs. (H) Phosphorylation of RYR2 from PRM at the SPEG phosphorylation site. In these studies, we could not distinguish between phosphorylation at S2367 and S2368. (I) Phosphorylation of RYR2 by PRM at the PKA phosphorylation site (S2807). No differences were detected among FL, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FKD in either the JPH2 or RYR2 IPs. JPH2 IPs: n = 11 for each genotype. RYR2 IPs, FL, n = 7, MCK-FKD, n = 10, MHC-FKD, n = 10. Data in G–I are shown as mean ± SD.

In summary, Fig. 6 shows no evidence that FKBP12 deficiency alters proteins interacting with RYR2 or JPH2 that can be detected by immunoprecipitation, nor does FKBP12 deficiency alter phosphorylation of RYR2 at S2367 or S2807, the two sites most consistently detected by mass spectrometry/PRM.

Changes in gene and protein expression

RNA-seq from the hearts of adult mice

To identify new candidates for the drivers of the altered cardiac phenotype in the MHC-FKD mice, we performed RNA-seq on hearts from FL, MHC-Cre+, MCK-FKD, and MHC-FDK mice. Volcano plots of significant (Padj < 0.05) changes in mRNA levels of the MHC-FKD, MCK-FKD, and MHC-Cre+ compared with FL are shown in Fig. 7, A–C. Venn diagrams showing the specific mRNAs shared and discrete in these data sets are shown in Fig. 7 D. Fkbp1a was, as expected, reduced in the hearts of both MCK-FKD and MHC-FKD. Kcne1 was upregulated in the hearts of both MCK-FKD and MHC-FKD mice, suggesting that the alteration in Kcne1 may be a direct effect of FKBP12 deficiency in adult hearts. Kcne1 encodes a regulatory subunit of the delayed rectifier channel, KCNQ1, that slows its opening and modulates its voltage dependence, which, in turn, regulates repolarization after an action potential (Barhanin et al., 1996; Sanguinetti et al., 1996; Nerbonne and Kass, 2005).

Differential expression and pathway enrichment analysis of RNA-seq on 12-wk-old mouse whole-heart samples by genotype. (A–C) Volcano plots of the log2 fold changes in gene expression and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values for (A) MHC-FKD, (B) MCK-FKD, and (C) MHC-Cre+ versus FL hearts. Black: Padj > 0.05 & abs(logFC) < 1; Orange: Padj < 0.05 & abs(logFC) < 1; Blue: Padj > 0.05 & abs(logFC) > 1; Red: Padj < 0.05 and abs(logFC) > 1. Genes with adjusted P value <0.05 are labeled. (D) Venn diagrams of the overlap in significantly downregulated and upregulated genes (adjusted P value <0.05) in MHC-FKD, MCK-FKD, and MHC-Cre+ versus FL hearts. (E) Plot of the most significantly enriched IPA cardiotoxicity functions as determined by the Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values for the Fisher’s exact tests on the overlap between the set of 348 analysis-ready genes with unadjusted P value <0.05 (203 up and 145 down) and the set of genes in each toxicological function. The set of differentially expressed analysis-ready genes associated with each cardiotoxicity function is displayed on the corresponding bar. N = 6 mice per genotype.

Differential expression and pathway enrichment analysis of RNA-seq on 12-wk-old mouse whole-heart samples by genotype. (A–C) Volcano plots of the log2 fold changes in gene expression and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values for (A) MHC-FKD, (B) MCK-FKD, and (C) MHC-Cre+ versus FL hearts. Black: Padj > 0.05 & abs(logFC) < 1; Orange: Padj < 0.05 & abs(logFC) < 1; Blue: Padj > 0.05 & abs(logFC) > 1; Red: Padj < 0.05 and abs(logFC) > 1. Genes with adjusted P value <0.05 are labeled. (D) Venn diagrams of the overlap in significantly downregulated and upregulated genes (adjusted P value <0.05) in MHC-FKD, MCK-FKD, and MHC-Cre+ versus FL hearts. (E) Plot of the most significantly enriched IPA cardiotoxicity functions as determined by the Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values for the Fisher’s exact tests on the overlap between the set of 348 analysis-ready genes with unadjusted P value <0.05 (203 up and 145 down) and the set of genes in each toxicological function. The set of differentially expressed analysis-ready genes associated with each cardiotoxicity function is displayed on the corresponding bar. N = 6 mice per genotype.

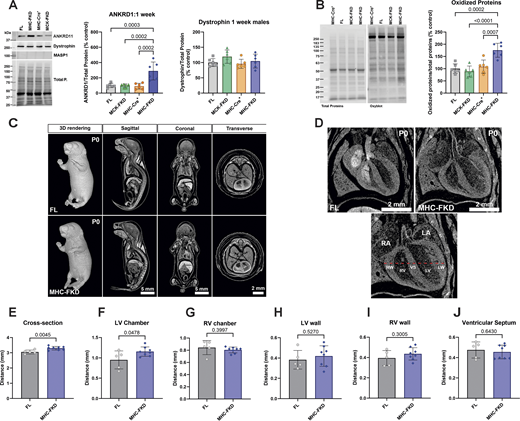

Three mRNAs (encoding dystrophin, ephrin B3, and interleukin 15) were significantly downregulated in the hearts of MHC-FKD mice. 18 mRNAs were upregulated only in the hearts of the MHC-FKD mice (Fig. 7 A). MHC-FKD upregulated genes included Masp1 (mannose-associated serine protease 1, which plays a role in the complement pathway in the innate and adaptive immune response), Ucp2 (mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2, which function to reduced mitochondrial oxidative stress), 2010001K21Rik (a 19-kDa protein of unknown function), Ankrd1 (ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 1), Mylpf (myosin light chain 11, primarily skeletal muscle, Fzd2 (frizzled 2, seven transmembrane spanning receptor), Cdkn1a (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A), Gm5790 (coronin, actin binding protein, 1C), Atp2a1 (SERCA1, ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 1, an isoform normally found in skeletal muscle fast twitch fibers), Lnx1 (ligand of numb-protein X 1, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase), Cntn2 (contactin 2, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily involved in cell adhesion), Epn3 (epsin 3, a membrane protein involved in membrane curvature and endocytosis), Edn3 (endothelin-3, a endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor peptide), Jpt1 (Jupiter microtubule associated homolog 1, a modulator of GSK2β signaling [Varisli et al., 2011]), Mybpc2 (myosin-binding protein C, fast-type), Kcnj14 (inward rectifier potassium channel Kir2.4), Grk5 (G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5), and Thbs4 (thrombospondin 4). Some of the proteins encoded by these genes could be involved in the cardiac remodeling in this mouse model. We used Ingenuity to assess pathways associated with mRNA changes between FL and MHC-FKD (P < 0.05) and found cardiac pathways associated with hypertrophy, enlargement of the heart, DCM, and arrhythmias to be significantly altered (Fig. 7 E). Fig. 7 E shows only the cardiac-specific toxicity pathways altered in MHC-FKD versus FL. Of the 18 mRNAs that were upregulated in MHC-FKD versus FL hearts, 6 were also upregulated in MHC-FKD versus MHC-Cre+ hearts (2010001K21Rik, Ankrd1, Edn3, Fzd2, Masp1, and Thbs4). Comparisons of MHC-FKD to MHC-Cre+ (rather than FL) and MHC-FKD to MCK-FKD are shown as volcano plots in Fig. S2.

Differentially expressed genes in total RNA from MHC-FKD versus MHC-Cre + hearts. (A) Volcano plot of the log2 fold changes in gene expression and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values for MHC-FKD versus MHC-Cre+ hearts. (B) Volcano plot of the log2 fold changes in gene expression and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values for MHC-FKD versus MCK-FKD hearts. Black: Padj > 0.05 and abs(logFC) < 1; Orange: Padj < 0.05 and abs(logFC) < 1; Blue: Padj >0.05 and abs(logFC) > 1; Red: Padj < 0.05 and abs(logFC) > 1.

Differentially expressed genes in total RNA from MHC-FKD versus MHC-Cre + hearts. (A) Volcano plot of the log2 fold changes in gene expression and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values for MHC-FKD versus MHC-Cre+ hearts. (B) Volcano plot of the log2 fold changes in gene expression and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values for MHC-FKD versus MCK-FKD hearts. Black: Padj > 0.05 and abs(logFC) < 1; Orange: Padj < 0.05 and abs(logFC) < 1; Blue: Padj >0.05 and abs(logFC) > 1; Red: Padj < 0.05 and abs(logFC) > 1.

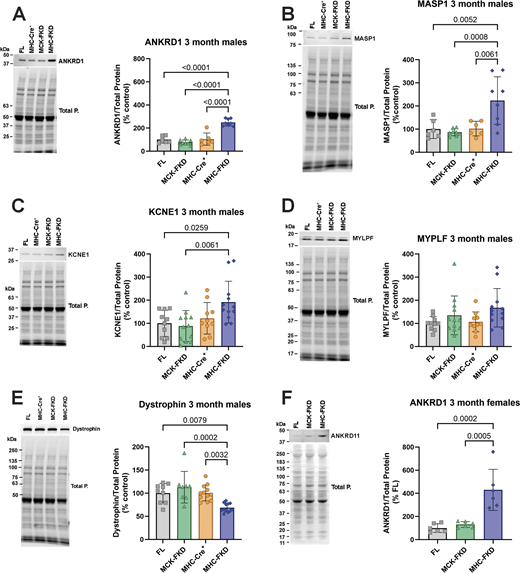

To confirm the RNA-seq data, we screened several of the putative up- or downregulated proteins by western blotting in cardiac homogenates from 3-mo-old male mice (Fig. 8, A–E). Consistent with the RNA-seq data, ANKRD1 (Fig. 8 A), MASP1 (Fig. 8 B), and KCNE1 (Fig. 8 C) were significantly increased only in the hearts of the MHC-FKD mice. We were unable to detect Thbs4 in western blots of cardiac homogenates. Dystrophin was significantly decreased (Fig. 8 E). The lack of an increase in KCNE1 in the hearts of the MCK-FKD mice was somewhat surprising given the increase in KCNE1 mRNA in these mice, but apparently, the change does not occur at the protein level. Despite the increase in mRNA for Mylpf in the hearts of MHC-FKD mice, we did not detect a change at the protein level (Fig. 8 D). We also demonstrated that ANKRD1 is elevated in the hearts of 3-mo-old female mice (Fig. 8 F).

Evaluation of proteins identified in RNA-seq. (A–F) Protein expression of several RNA-seq detected transcripts was validated using western blot of hearts from 3-mo-old mice. Proteins of interest were normalized to the total protein level in the same lane, normalized to the average expression level in FL hearts, and expressed as %FL. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs with P value indicated, n = 6 for all genotypes. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F8.

Evaluation of proteins identified in RNA-seq. (A–F) Protein expression of several RNA-seq detected transcripts was validated using western blot of hearts from 3-mo-old mice. Proteins of interest were normalized to the total protein level in the same lane, normalized to the average expression level in FL hearts, and expressed as %FL. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs with P value indicated, n = 6 for all genotypes. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F8.

In summary, Figs. 7 and 8 show that Ankrd1 and Masp1 mRNA and their encoded proteins were elevated only in the MHC-FKD mice. In addition, dystrophin mRNA and protein levels were decreased only in MHC-FKD mice. Kcne1 mRNA levels are elevated in the hearts of both MCK-FKD and MHC-FKD mice, but we only detected the protein increase in the hearts of MHC-FKD mice.

Changes in newborn to 1-wk-old mice

Since only the MHC-Cre+-mediated FKBP12 deficiency had major effects on adult cardiac function, we evaluated the effects of FKBP12 deficiency on protein expression detected in 7-day-old hearts. Of the proteins tested, only ANKRD1 was found to be elevated (Fig. 9 A) at day 7, suggesting the possibility that ANKRD1 is a contributor to the cardiac phenotype in the MHC-FKD mice. MASP1 was not detected, and dystrophin (Fig. 9 A) was not decreased in the hearts of 7-day-old MHC-FKD mice. We also found that oxidized proteins, as detected with an oxyblot are increased only in the hearts of the 1-wk-old MHC-FKD mice (Fig. 9 B) To explore the possibility that FKBP12 deficiency during embryonic development contributes to the cardiac defects in the MHC-FKD mice, we imaged FL and MHC-FKD at birth (P0) using iodine-contrast micro-CT imaging. Fig. 9 C shows the P0 pups (males and females combined) at different angles. Fig. 9 D shows an enlarged view of the hearts, and the measurements (see bottom panel in Fig. 9 D) are summarized in Fig. 9, E–J (see also Table S7). We found that the left ventricle of the P0 MHC-FKD mice was already enlarged compared with FL controls at birth, suggesting that the cardiac changes that lead to DCM are likely to begin at an embryonic stage. These data are the only data in this manuscript where male and female mice data are combined. Similar differences were obtained (but not significant) if males and females were separated.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on 1-wk-old mice. (A) Protein expression of several RNA-seq detected transcripts was validated using western blot of hearts from (A) 1-wk-old mice. Proteins of interest were normalized to the total protein level in the same lane, normalized to the average expression level in FL hearts, and expressed as %FL. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs with P value indicated. n = 6 for all genotypes. Data are shown as mean ± SD. (B) Oxyblot and analysis of oxidized proteins in hearts of 7-day-old mice of each genotype. (C) Iodine contrast microCT for cardiac phenotyping of P0 FL and MHC-FKD mice. Micro CT 3D imaging was performed on iodine contrasted FL (n = 5) and MHC-FKD (n = 8) neonates at birth (postnatal day 0, P0) to examine the gross morphology and phenotyping. 3D whole volume rendering and digitally sectioned at sagittal, coronal, and transverse axes and were a mixture of males and females (seven females, eight males). Sex differences were not detected. (D) Digital image showing cardiac structure of the right atrium (RA), left atrium (LA), right ventricular wall (RW), right ventricle (RV), ventricular septum (VS), left ventricle (LV), and left ventricular wall (LW) were examined. The thickness of the left/right ventricular walls and septum and the width of the left/right ventricles were measured along the dashed red line for each sample. (E and F) Quantitative analysis shows significant increases the (E) cross section of ventricles (P = 0.0045) and (F) LV Chamber width (P = 0.0478) in MHC-FKD neonates. (G and H) RV chamber (G), LV wall (H). (I and J) (I) RV wall and (J) ventricular septum (all datapoints provided) were not significantly different. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs with P value indicated. Data are shown are mean ± SD. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F9.

Effects of FKBP12 deficiency on 1-wk-old mice. (A) Protein expression of several RNA-seq detected transcripts was validated using western blot of hearts from (A) 1-wk-old mice. Proteins of interest were normalized to the total protein level in the same lane, normalized to the average expression level in FL hearts, and expressed as %FL. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs with P value indicated. n = 6 for all genotypes. Data are shown as mean ± SD. (B) Oxyblot and analysis of oxidized proteins in hearts of 7-day-old mice of each genotype. (C) Iodine contrast microCT for cardiac phenotyping of P0 FL and MHC-FKD mice. Micro CT 3D imaging was performed on iodine contrasted FL (n = 5) and MHC-FKD (n = 8) neonates at birth (postnatal day 0, P0) to examine the gross morphology and phenotyping. 3D whole volume rendering and digitally sectioned at sagittal, coronal, and transverse axes and were a mixture of males and females (seven females, eight males). Sex differences were not detected. (D) Digital image showing cardiac structure of the right atrium (RA), left atrium (LA), right ventricular wall (RW), right ventricle (RV), ventricular septum (VS), left ventricle (LV), and left ventricular wall (LW) were examined. The thickness of the left/right ventricular walls and septum and the width of the left/right ventricles were measured along the dashed red line for each sample. (E and F) Quantitative analysis shows significant increases the (E) cross section of ventricles (P = 0.0045) and (F) LV Chamber width (P = 0.0478) in MHC-FKD neonates. (G and H) RV chamber (G), LV wall (H). (I and J) (I) RV wall and (J) ventricular septum (all datapoints provided) were not significantly different. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs with P value indicated. Data are shown are mean ± SD. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F9.

In summary, Fig. 9 shows that, even at birth, the left ventricle of the MHC-FKD mice is slightly enlarged and in 1-wk-old mice, and ANKRD1 and oxidized proteins are elevated only in the MHC-FKD mice.

Discussion

A role for FKBP12 in stabilizing the closed state of RYR1 is controversial (Tang et al., 2004; Seidler et al., 2007; Galfré et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016; Asghari et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2023), but, nonetheless, FKBP12 binds to RYR2 (Guo et al., 2010). Guo et al. (2010) estimated that FKBP12 binds to RYR2 with a Kd of 200 nM and is expressed in cardiac tissue at ∼1 µM, while FKBP12.6 binds with much higher affinity but with a 10-fold lower tissue concentration (Guo et al., 2010), suggesting that 10–20% of the FKBP binding sites on RYR2 are occupied by FKBP12.6 and the remaining sites are potentially occupied by FKBP12. Using permeabilized cardiomyocytes and overexpression of FKBP12.6 and FKBP12, Guo et al. (2010) found that FKBP12.6, not FKBP12, inhibits RYR2 activity (Guo et al., 2010). These findings raise the question of what are the functional consequences, if any, of FKBP12 binding to RYR2. Different laboratories have different answers to this question (Tang et al., 2004; Seidler et al., 2007; Galfré et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016; Asghari et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2023), but some of the controversy is likely to have arisen from the use of drugs such as rapamycin and S107 to remove endogenously bound FKBPs and the markedly different experimental approaches and models used to test function. We used mouse models of FKBP12 deficiency to define the role of FKBP12 in heart function. Since FKBP12.6 mRNA levels were not altered in the hearts of our MHC-FKD compared with control mice, and the functional consequence of FKBP12.6 binding to RYR2 has been confirmed in several laboratories (Wehrens et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011), we concentrated on defining the consequences of FKBP12 deficiency on cardiac function.

We used two mouse models of FKBP12 deficiency with Cre recombinase driven by different promoters (MHC versus MCK) to illustrate that the timing of the FKBP12 deficiency is a critical determinant of whether the FKD develop oxidative stress, alterations in ECC protein expression, SR Ca2+ leak, and DCM. For all functional studies, we included both FL and MHC-Cre+ mice as controls, the latter because of the reports of cytotoxicity in older mice of high levels of expression of Cre+ (Pugach et al., 2015; Gillet et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023). We did not detect cytotoxicity of the MHC-Cre+ even in mice as old as 1 year, due, in part, to lower MHC-Cre+ expression in our mice (∼1/3 the level of Cre+ recombinase in the hemizygous αMHC-Cre+ mice from Jackson Laboratories). The reason for the difference is not known but could be related to the multiple backcrosses leading to the loss or inactivation of some copies of the MHC-Cre+ gene, housing conditions that cause epigenetic modifications, and/or genetic drift. Pugach et al. (2015) recommended that all studies using the αMHC-Cre+ to drive recombination include the α-MHC-Cre+ only as controls. Our studies show that all αMHC-Cre+ lines from the original strain (Agah et al., 1997) are not equivalent, suggesting that the levels of Cre+ expression should also be monitored when using the α-MHC-Cre+ recombinase mice.

MCK-FKD mice with Cre-recombinase that turn on at E13.5 have FKBP12 levels decreased by 6 mo of age to similar levels as MHC-FKD mice. However, the MCK-FKD mice never develop DCM. RYR2 is normally expressed in embryonic hearts by E10 (Takeshima et al., 1998). FKBP12 is also expressed at an early stage in cardiac development (Shou et al., 1998), and FKBP12 deficiency leads to multiple structural changes including the development of severe DCM. In contrast, FKBP12.6-deficient mice do not develop an obvious cardiomyopathy in the absence of stress. Wehrens et al. (2003) found that exercise caused ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in FKBP12.6 deficient mice. However, another strain of FKBP12.6 deficient mice did not display exercise-induced arrhythmias and/or sudden cardiac death (Xiao et al., 2007).

Mice with the FKBP12 deficiency driven by Cre+ recombinase under the control of the αMHC promoter or MCK promoter efficiently reduced FKBP12 by ∼90% in hearts isolated from adult mice. However, only the MHC-FKD mice developed DCM, and only cardiomyocytes from these mice displayed increased SR Ca2+ leak and increased spontaneous Ca2+ waves. If FKBP12 is not stabilizing the closed state of RYR2 as shown by Guo et al. (2010), it is important to determine what is causing the SR Ca2+ leak in cardiomyocytes isolated from the hearts of adult MHC-FKD mice. We used the process of elimination to identify the underlying differences in the cardiac phenotypes of the MHC-FKD and MCK-FKD. Initially, we hypothesized that there was a higher residual amount of FKBP12 in the hearts of the MCK-FKD mice compared with the MHC-FKD mice, which limited SR Ca2+ leak in the hearts of MCK-FKD mice (i.e., an inhibitory role of FKBP12 on RYR2 activity). While there is significantly higher FKBP12 in hearts of 7-day-old MCK-FKD versus MHC-FKD mice, a difference was not significant at 3 or 6 mo of age. An increase in FKBP12.6 in the hearts of the MCK-FKD mice could potentially compensate for the loss of FKBP12. However, in the RYR2 IPs, there was no difference in the amount of FKBP12.6 among the four genotypes (FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+ only, and MHC-FKD), and we did not detect any difference in the levels of FKBP12.6 mRNA.

Our second hypothesis was that the Ca2+ leak in the MHC-FKD mice arose from the loss of other inhibitory interactions within the ECC complex. By western blotting, we detected a decrease in CaV1.2α1c and JPH2 in the hearts of MHC-FKD mice and a small increase in a calpain cleavage product of the latter. These changes could decrease the gain of ECC and possibly alter protein–protein interactions among some ECC proteins. A JPH2-mediated change in dyad stability (Gross et al., 2021) could also alter RYR2 gating. Indeed, we detected some differences in t-tubule regularity in cardiomyocytes from the MHC-FKD mice, but similar changes were detected in the cardiomyocytes from the MCK-FKD mice.

To further assess changes in protein interactions, we immunoprecipitated both RYR2 and JPH2 from the hearts of these mice. Although this approach is limited to high-affinity interactions, we previously used this approach to identify RYR and JPH2 binding proteins in both cardiac and skeletal muscle that require SPEG kinase (Lee et al., 2023). In the current study, we did not detect any differences in the composition of RYR2 or JPH2 protein complexes in the hearts of MHC-FKD and MCK-FKD mice using immunoprecipitation/mass spectrometry. Nor did we detect differences in RYR2 phosphorylation at either S2367, a SPEG phosphorylation site (Quick et al., 2017; Campbell et al., 2020) or S2807, a PKA phosphorylation site (Dridi et al., 2020).

Finally, oxidative stress causes SR Ca2+ leak via modifications of RYR2 (Terentyev et al., 2008; Matecki et al., 2016; Gonzalez et al., 2014; Oda et al., 2015; Bovo et al., 2018). We detected an increase in oxidative modifications of proteins only in the hearts of the MHC-FKD mice. Whether this represents ROS-generated modifications of RYR2 to cause SR Ca2+ leak or SR Ca2+ leak causing mitochondrial ROS production is not yet known.

To gain further insight into molecular changes that drive the development of SR Ca2+ leak and DCM in hearts of MHC-FKD mice that are not found in the other genotypes of mice, we performed RNA-seq analysis of the hearts of the FL, MCK-FKD, MHC-Cre+ only, and MHC-FKD mice. We identified major changes in gene expression levels only in the hearts of MHC-FKD mice. 18 gene products were altered only in the MHC-FKD hearts compared with FL, including 2 genes that are known to be associated with DCM: dystrophin (downregulated) and Ankrd1 (upregulated). Both changes were confirmed at the protein level by western blotting. Increased expression of ANKRD1 (a nuclear and sarcomere localized member of the ankyrin repeat family) has been found in many individuals with DCM and in mice that develop DCM (Bogomolovas et al., 2015; Ling et al., 2017; Kempton et al., 2018). We also detected an increase in MASP1 (mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 1), a serine protease involved in the lectin pathway of complement activation, suggesting an inflammatory involvement in the MHC-FKD cardiac phenotype (Németh et al., 2023). Masp1 mRNA levels increased in MHC-FKD hearts, and an increase in MASP1 protein level was confirmed by western blotting. We detected an elevation in the mRNA and protein levels of KCNE1, the regulatory subunit of the delayed rectifier channel (Wu and Larsson, 2020), but the significance of this upregulation remains to be explored. Increases in ANKRD1, MASP1, and KCNE1 and decreases in dystrophin and FKBP12 were not detected in hearts of MHC-Cre+ mice, supporting our conclusions from the echocardiography and biochemical data that none of the alterations in cardiac function associated with FKBP12 deficiency are due to Cre recombinase cardiotoxicity (Gillet et al., 2019; Rehmani et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023).

Pathway analyses of the genes in RNA-seq data from MHC-FKD mice that were significantly different from FL (using P < 0.05 to increase the number of potential candidates above the 18 genes identified by Padj) indicate that the changes in the MHC-FKD mice were associated with changes in pathways involved in cardiac enlargement, including hypertrophy and dilation, as well as arrhythmias, cardiac damage, and cardiac fibrosis, suggesting that significant cardiac remodeling has occurred.