Peroxisomes perform key metabolic functions in eukaryotic cells. Loss of peroxisome function causes peroxisome biogenesis disorders and severe childhood diseases with disrupted lipid metabolism. One mechanism regulating peroxisome abundance is degradation via selective autophagy (pexophagy). However, the mechanisms regulating pexophagy remain poorly understood in mammalian cells. Here, we find that the evolutionarily conserved AAA-ATPase p97/VCP and its adaptor UBXD8/FAF2 are essential for maintaining peroxisome abundance. From quantitative proteomics studies, we show that loss of UBXD8 affects the abundance of many peroxisomal proteins and that the depletion of UBXD8 results in a loss of peroxisomes. Loss of p97-UBXD8 and inhibition of p97 catalytic activity increase peroxisomal turnover through autophagy and can be rescued by depleting key autophagy proteins and E3 ligases or overexpressing the deubiquitylase USP30. We find increased ubiquitylation of PMP70 and PEX5 in cells lacking UBXD8 or p97. Our findings identify a new role of the p97-UBXD8 in regulating peroxisome abundance by removing ubiquitylated peroxisome membrane proteins to prevent pexophagy.

Introduction

Peroxisomes are ubiquitous, dynamic organelles with central roles in lipid metabolism (Mast et al., 2020; Schrader et al., 2020). These functions include purine catabolism, bile acid, ether phospholipid synthesis, and β- and α-oxidation of very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) and branched-chain fatty acids (Mast et al., 2020; Schrader et al., 2020; Terlecky and Fransen, 2000). Peroxisomes are also essential for detoxifying reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (Chen et al., 2020; Wanders et al., 2010). Peroxisome homeostasis is maintained by a group of peroxin (PEX) proteins that coordinate peroxisome biogenesis, import, and fission. Given their central roles, loss of peroxisomes or defects in PEX can result in dramatic alterations to the cellular lipidome and lead to a host of human diseases broadly termed peroxisome biogenesis disorders (PBDs) (Aubourg and Wanders, 2013; Schrader et al., 2020). These include neonatal adrenoleukodystrophy, Zellweger spectrum disorders, and Refsum disease, among others, which affect multiple organs with a prominent neurological phenotype (Weller et al., 2003).

Peroxisome abundance is maintained through de novo biogenesis, fission of mature peroxisomes, and degradation through a selective form of autophagy known as pexophagy (Germain and Kim, 2020; Terlecky and Fransen, 2000). Environmental stressors, including nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, and high ROS levels, can trigger pexophagy (Germain and Kim, 2020). Several findings suggest that PEX involved in peroxisome biogenesis, as well as the import of matrix proteins, contribute to pexophagy (Germain and Kim, 2020). For example, depletion of peroxisome biogenesis proteins PEX16 or overexpression of PEX3 induces ubiquitylation of peroxisome membrane proteins, leading to pexophagy (Germain and Kim, 2020; Wei et al., 2021; Yamashita et al., 2014). During amino acid starvation, the peroxisome-resident E3 ligase PEX2 can ubiquitylate the import receptor PEX5 and the peroxisomal membrane protein 70 (PMP70/ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 3 [ABCD3]) (Sargent et al., 2016). Ubiquitylated PEX5 recruits the autophagy adaptor proteins, sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1/p62) and neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 (NBR1), which target peroxisomes for pexophagy (Deosaran et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015a). Despite the importance of maintaining peroxisome homeostasis, the molecular mechanisms regulating pexophagy in mammalian cells are not comprehensively understood (Zalckvar and Schuldiner, 2022).

p97, also known as valosin-containing protein, is an evolutionarily conserved, homohexameric AAA-ATPase that is essential for ubiquitin-dependent protein quality control (Neuber et al., 2005; Stach and Freemont, 2017). Consecutive ATP hydrolysis by p97 monomers in the hexamer causes the unfolding of bound ubiquitylated substrates as they pass through the central pore of the homohexamer (Cooney et al., 2019; Twomey et al., 2019). While p97 has well-established roles in the degradation of ubiquitylated proteins by the 26S proteasome, recent studies indicate that it also participates in early and late steps in autophagy (Ahlstedt et al., 2022; Papadopoulos et al., 2017; Tanaka et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2022). p97 associates with over 30 adaptors that interact with its N or C termini, enabling recruitment of p97 to various organelles and ubiquitylated substrates (Stach and Freemont, 2017). One such adaptor, UBXD8 (also known as Fas-associated factor 2, FAF2), is localized to the ER via a hydrophobic hairpin (HP) motif that inserts into the outer leaflet of the ER membrane. At the ER, the p97-UBXD8 complex facilitates ER-associated degradation (ERAD), wherein misfolded proteins in the ER lumen or membrane are ubiquitylated, retrotranslocated to the cytosol, and degraded by cytosolic proteasomes (Neuber et al., 2005; Ruggiano et al., 2014). UBXD8 recognizes ubiquitylated substrates and p97 through its ubiquitin-associated (UBA) and ubiquitin X (UBX) domains, respectively. Recent studies suggest that UBXD8 also localizes to and regulates the functions of lipid droplets and mitochondria (Olzmann et al., 2013; Song et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2022a).

In previous published work from our group, we used quantitative tandem mass tag (TMT) proteomics to determine how the cellular proteome is remodeled in UBXD8 knockout (KO) cells generated by CRISPR editing (Ganji et al., 2023). Further analysis of this proteomics dataset led to the surprising finding that numerous peroxisomal proteins were depleted in UBXD8 KO cell lines compared with wild-type (WT) cells. We explored this unexpected finding further and found that loss of UBXD8 leads to a significant reduction in peroxisomes in multiple cell lines. We further show that loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 KO cells causes an increase in VLCFAs and a decrease in catalase activity. Moreover, we find endogenous UBXD8 localizes to peroxisomes, and loss of p97-UBXD8 increases the degradation of peroxisomes in a manner that is dependent on ubiquitylation of peroxisomal membrane proteins, p97 catalytic activity, and autophagy. Taken together, we show that the p97-UBXD8 complex controls peroxisome abundance and function by suppressing their degradation through autophagy.

Results

Quantitative proteomics identifies altered levels of peroxisomal proteins in UBXD8 KO cells

In previous work from our group, we evaluated how the loss of UBXD8 impacted the cellular proteome. We generated UBXD8 KO HeLa and HEK293T cell lines and performed multiplexed, quantitative proteomics from whole-cell extracts and ER–mitochondria contacts using TMTs on triplicate WT and UBXD8 KO cells (Table S1). This study elucidated a novel role of the p97-UBXD8 complex in regulating ER–mitochondria contact sites by modulating lipid desaturation and membrane fluidity (Ganji et al., 2023).

Intriguingly, further analysis of the whole-cell proteomics dataset indicated that numerous peroxisomal proteins were reproducibly depleted in both HeLa and HEK293T UBXD8 KO cells (61 in HeLa and 65 in HEK293T) (Fig. 1 A; Fig. S1, A and B; and Table S1). 10 of these proteins displayed a statistically significant depletion in UBXD8 KO HeLa cells relative to WT (log2 fold change [KO: WT] >0.65 and −log10 P >1.5) (Fig. 1 A and Table S1). Depleted proteins were involved in various peroxisomal processes ranging from import to metabolic functions, suggesting global peroxisome alterations (Fig. S1 C). We identified proteins crucial for biogenesis (PEX3, PEX16, and PEX26), as well as enzymes involved in distinct lipid metabolic reactions such as ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 1, ABCD3, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase family member 11, and acyl-CoA oxidase 3 to be impacted (Fig. 1 B). We validated our results by immunoblotting for a subset of these peroxisomal proteins in HeLa and HEK293T cells and found significant depletion in both cell lines (Fig. 1, C and D). While we did not find changes in PEX19 protein levels from the whole-cell proteomics dataset, we did find depletion of this biogenesis factor by immunoblotting whole-cell extracts. This may be due to loss of PEX19 associated with peroxisomes that are lost in UBXD8 KO cells (see below and Discussion). Loss of peroxisomal proteins was not due to deficits in transcription as transcript levels of most peroxisomal mRNAs were generally not altered between WT and UBXD8 KO cells (Fig. S1 D). Taken together, our quantitative proteomics studies suggest UBXD8 maintains the abundance of many peroxisomal proteins.

Quantitative proteomics identifies a role of UBXD8 in regulating peroxisome protein abundance. (A) Volcano plot of the (−log10-transformed P value versus the log2-transformed ratio of UBXD8 KO to WT) proteins identified from HeLa cells. N = 3 biologically independent samples for each genotype. P values were determined by empirical Bayesian statistical methods (two-tailed t test adjusted for multiple comparisons using Benjamini–Hochberg’s correction method) using the LIMMA R package; for parameters, individual P values, and q values, see Supplementary Dataset in Ganji et al. (2023). Peroxisomal proteins (green-filled), important for biogenesis (blue outlines) and metabolism (red outlines), are highlighted. This dataset has been previously published (Ganji et al., 2023) and is reanalyzed here. (B) Schematic pathways regulating peroxisome abundance and function with highlighted TMT proteomics hits. (C) Peroxisomal proteins identified in A show reduced expression in UBXD8 KO compared with WT HeLa and HEK293T cells by immunoblot. (D) Quantification of C. ****P < 0.0001, N = 3, unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Quantitative proteomics identifies a role of UBXD8 in regulating peroxisome protein abundance. (A) Volcano plot of the (−log10-transformed P value versus the log2-transformed ratio of UBXD8 KO to WT) proteins identified from HeLa cells. N = 3 biologically independent samples for each genotype. P values were determined by empirical Bayesian statistical methods (two-tailed t test adjusted for multiple comparisons using Benjamini–Hochberg’s correction method) using the LIMMA R package; for parameters, individual P values, and q values, see Supplementary Dataset in Ganji et al. (2023). Peroxisomal proteins (green-filled), important for biogenesis (blue outlines) and metabolism (red outlines), are highlighted. This dataset has been previously published (Ganji et al., 2023) and is reanalyzed here. (B) Schematic pathways regulating peroxisome abundance and function with highlighted TMT proteomics hits. (C) Peroxisomal proteins identified in A show reduced expression in UBXD8 KO compared with WT HeLa and HEK293T cells by immunoblot. (D) Quantification of C. ****P < 0.0001, N = 3, unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Quantitative proteomics of WT and UBXD8 KO cells identifies loss of peroxisomal proteins. (A) Volcano plot of the (−log10-transformed P value versus the log2-transformed ratio of UBXD8 KO to WT) proteins identified from HEK293T cells. n = 3 biologically independent samples for each genotype. P values were determined by empirical Bayesian statistical methods (two-tailed t test adjusted for multiple comparisons using Benjamini–Hochberg’s correction method) using the LIMMA R package; for parameters, individual P values, and q values, see Ganji et al. (2023) for dataset. Peroxisomal proteins are shown in green-filled circles. Outlines indicate proteins involved in biogenesis (blue) and metabolism (red). (B) Correlation of two HEK293T UBXD8 KO clones used for TMT analysis. (C) Bubble plot representing significantly enriched GO clusters identified from TMT proteomics of CRISPR UBXD8 KO (black) and WT (blue) cells. The size of the circle indicates the number of genes identified in each cluster. (D) RT-qPCR assessment of different peroxisomal transcripts in WT and UBXD8 KO cells. N = 3 independent experiments. The graph shows the mean and std.dev. NS: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test.

Quantitative proteomics of WT and UBXD8 KO cells identifies loss of peroxisomal proteins. (A) Volcano plot of the (−log10-transformed P value versus the log2-transformed ratio of UBXD8 KO to WT) proteins identified from HEK293T cells. n = 3 biologically independent samples for each genotype. P values were determined by empirical Bayesian statistical methods (two-tailed t test adjusted for multiple comparisons using Benjamini–Hochberg’s correction method) using the LIMMA R package; for parameters, individual P values, and q values, see Ganji et al. (2023) for dataset. Peroxisomal proteins are shown in green-filled circles. Outlines indicate proteins involved in biogenesis (blue) and metabolism (red). (B) Correlation of two HEK293T UBXD8 KO clones used for TMT analysis. (C) Bubble plot representing significantly enriched GO clusters identified from TMT proteomics of CRISPR UBXD8 KO (black) and WT (blue) cells. The size of the circle indicates the number of genes identified in each cluster. (D) RT-qPCR assessment of different peroxisomal transcripts in WT and UBXD8 KO cells. N = 3 independent experiments. The graph shows the mean and std.dev. NS: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test.

Deletion of UBXD8 decreases peroxisome abundance

We next asked whether the loss of peroxisomal proteins in UBXD8 KO cells impacted peroxisome abundance. WT and UBXD8 KO cells were stained with an antibody to catalase (a peroxisomal matrix marker) and PMP70 (a membrane marker). Peroxisome number per cell and size were measured using AggreCount, an automated image analysis script developed in the laboratory (Klickstein et al., 2020). We observed that the number of peroxisomes was decreased, and the size of peroxisomes was increased in the absence of UBXD8 in HeLa cells (even accounting for changes in cell area, which can cause scaling of peroxisome numbers) (Fig. 2, A–D and data not shown). Notably, ∼10% of UBXD8 KO cells were completely devoid of peroxisomes (Fig. S2, A–D). Reduction in the number of peroxisomes was further validated in HEK293T UBXD8 KO cells (Fig. S2, E–H) and by transient depletion with two distinct siRNAs (Fig. 2, E–G). We next asked whether overexpressing UBXD8 increased peroxisome numbers. Indeed, WT HeLa cells overexpressing UBXD8 had a modest but significant increase in peroxisome number (Fig. 2, H–J). We used both KO cells and siRNA depletion in the following studies. We note that UBXD8 deletion or depletion in other cell lines consistently reduced peroxisome abundance, but the increase in peroxisome size was unique to HeLa cells. In summary, UBXD8 is necessary to maintain the cellular pool of peroxisomes.

Deletion of UBXD8 perturbs peroxisome abundance. (A) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells were stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix marker catalase. (B) Quantification of average peroxisome per cell and average peroxisome size from A. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (C) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using PMP70. (D) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell and peroxisome size in C. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (E) HeLa cells were transfected with control and two different UBXD8 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (F) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell and peroxisome size from E. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ns: not significant, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (G) Immunoblot showing UBXD8 depletion. (H) Overexpression of UBXD8 increases peroxisomes in WT HeLa cells. WT HeLa cells were transfected with UBXD8-HA and stained for catalase. (I) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell in WT, UBXD8 KO, and WT transfected with UBXD8-HA. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. *P < 0.0169, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, two-way ANOVA. (J) Immunoblot of UBXD8-HA expression. The scale bar is 10 μM (A, C, and H) and 5 μM (E). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

Deletion of UBXD8 perturbs peroxisome abundance. (A) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells were stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix marker catalase. (B) Quantification of average peroxisome per cell and average peroxisome size from A. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (C) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using PMP70. (D) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell and peroxisome size in C. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (E) HeLa cells were transfected with control and two different UBXD8 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (F) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell and peroxisome size from E. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ns: not significant, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (G) Immunoblot showing UBXD8 depletion. (H) Overexpression of UBXD8 increases peroxisomes in WT HeLa cells. WT HeLa cells were transfected with UBXD8-HA and stained for catalase. (I) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell in WT, UBXD8 KO, and WT transfected with UBXD8-HA. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. *P < 0.0169, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, two-way ANOVA. (J) Immunoblot of UBXD8-HA expression. The scale bar is 10 μM (A, C, and H) and 5 μM (E). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

UBXD8 deletion leads to loss of peroxisomes in HeLa and HEK293T cell lines. (A) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix protein catalase. (B) Peroxisome numbers in WT and UBXD8 KO cells that have either no peroxisomes or <10 peroxisomes per cell as measured by catalase. ns: not significant, **P < 0.001, unpaired t test. (C) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using PMP70. (D) Peroxisome numbers in WT and UBXD8 KO cells that have either no peroxisomes or <10 peroxisomes per cell as measured by PMP70. ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, unpaired t test. (E) HEK293T WT and UBXD8 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix protein catalase. (F) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell and peroxisome size from E. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, N = 3, unpaired t test. (G and H) Same as (E and F) but stained for PMP70. The scale bar is 10 μM (A, C, E, and G).

UBXD8 deletion leads to loss of peroxisomes in HeLa and HEK293T cell lines. (A) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix protein catalase. (B) Peroxisome numbers in WT and UBXD8 KO cells that have either no peroxisomes or <10 peroxisomes per cell as measured by catalase. ns: not significant, **P < 0.001, unpaired t test. (C) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using PMP70. (D) Peroxisome numbers in WT and UBXD8 KO cells that have either no peroxisomes or <10 peroxisomes per cell as measured by PMP70. ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, unpaired t test. (E) HEK293T WT and UBXD8 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix protein catalase. (F) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell and peroxisome size from E. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, N = 3, unpaired t test. (G and H) Same as (E and F) but stained for PMP70. The scale bar is 10 μM (A, C, E, and G).

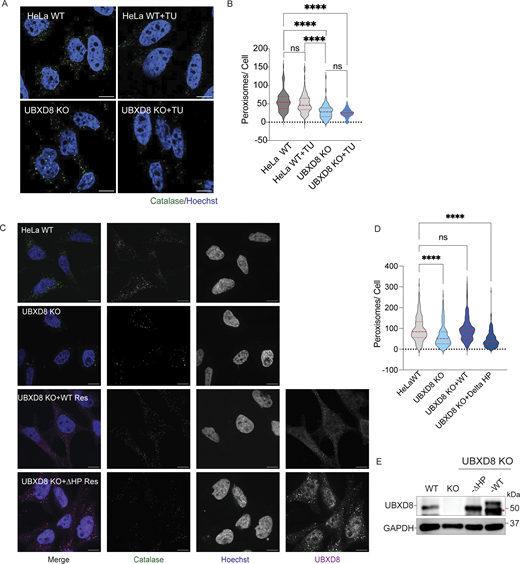

Loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 null cells is not due to ER stress or ERAD inhibition

UBXD8 has essential functions in ERAD to help alleviate ER stress (Schuberth and Buchberger, 2008). Given that the ER can regulate peroxisome biogenesis, it is possible that loss of UBXD8 and subsequent inhibition of ERAD could cause ER stress, thus leading to perturbed peroxisome abundance. We systematically tested whether the loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 KO cells was a secondary consequence of ER stress. First, we asked whether the depletion of two major E3 ligases that execute ERAD, HMG CoA reductase degradation 1 (HRD1) and GP78 (Schulz et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2015b), impacted peroxisome abundance. HRD1 depletion with one of the two siRNAs tested resulted in a small increase in peroxisome numbers (Fig. 3, A–C). GP78 KO HEK293T cell lines generated by CRISPR editing (Bersuker et al., 2018) had a small increase in peroxisome abundance (Fig. 3, D–F). Thus, loss of ERAD E3s did not reproducibly result in a significant loss of peroxisomes as observed in UBXD8 KO cells. Second, we asked whether alternate p97 ERAD adaptors, such as UBXD2 (Liang et al., 2006), regulated peroxisome abundance. We measured peroxisome number in a HeLa UBXD2 KO cell line and observed no significant change in peroxisome abundance (Fig. 3, G and H). Third, we asked whether increasing ER stress impacted peroxisome numbers. We treated WT and UBXD8 KO cells with tunicamycin, which causes protein misfolding in the ER by preventing N-linked glycosylation, but observed no impact on the peroxisome number in either cell line (Fig. S3, A and B). Nevertheless, given that the estimated half-life of peroxisomes is between 1.3 and 2.2 days, our analysis may not be capturing peroxisome turnover in the 4-h treatment window. We were not able to treat for longer time points due to cell toxicity (Zientara-Rytter and Subramani, 2016). To further explore this, we asked whether there was increased ER stress in UBXD8 KO cells by assessing levels of the ER chaperone binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP), activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) by immunoblot, and transcript levels of x box binding protein 1 spliced (xbp1s) by quantitative real-time PCR. WT cells were treated with dithiothreitol (DTT), to induce ER stress as a positive control. We found increased BiP, ATF4, and xbp1s levels in WT cells treated with DTT. However, the levels of these markers were unchanged in UBXD8 KO cells (Fig. 3, I and J). Thus, to the extent measured, we conclude that the decrease in peroxisome abundance in UBXD8 KO cells is likely not due to altered ER protein homeostasis.

ER stress does not contribute to loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 null cells. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with control or two different HRD1 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (B) Quantification of the number of peroxisomes per cell, at least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ns: not significant, ****P < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Immunoblot showing depletion of Hrd1. (D) HEK293T WT cells and GP78 KO cells stained for catalase. (E) Quantification of peroxisome per cell in C. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (F) Immunoblot of GP78. (G) HeLa WT and UBXD2 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using catalase. (H) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from C. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ns: not significant, unpaired t test. (I and J) Immunoblots of HeLa WT (untreated or treated with DTT) and UBXD8 KO cells for ER stress markers BiP and ATF4. N = 3. (J) RT-qPCR of xbp1 total and xbp1 spliced (xbp1s) mRNA transcripts in WT and UBXD8 KO cells treated with 1.5 mM DTT for 4 h. N = 3. ns: not significant, *P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis. The scale bar is 10 μM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

ER stress does not contribute to loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 null cells. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with control or two different HRD1 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (B) Quantification of the number of peroxisomes per cell, at least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ns: not significant, ****P < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Immunoblot showing depletion of Hrd1. (D) HEK293T WT cells and GP78 KO cells stained for catalase. (E) Quantification of peroxisome per cell in C. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (F) Immunoblot of GP78. (G) HeLa WT and UBXD2 KO cells stained for peroxisomes using catalase. (H) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from C. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ns: not significant, unpaired t test. (I and J) Immunoblots of HeLa WT (untreated or treated with DTT) and UBXD8 KO cells for ER stress markers BiP and ATF4. N = 3. (J) RT-qPCR of xbp1 total and xbp1 spliced (xbp1s) mRNA transcripts in WT and UBXD8 KO cells treated with 1.5 mM DTT for 4 h. N = 3. ns: not significant, *P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis. The scale bar is 10 μM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

Role of ER stress and UBXD8 HP domain in regulation of peroxisomes. (A) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells were treated with tunicamycin (2.5 μM for 4 h) and stained for catalase. (B) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from A. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ns: not significant, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Rescue of peroxisome number in UBXD8 KO cells transfected with either UBXD8-HA or UBXD8-ΔHP. Cells were stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix marker catalase. (D) Quantification of average peroxisomes per cell from C. Peroxisome numbers were quantified in cells expressing tagged UBXD8 constructs only. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (E) Immunoblots of constructs transfected. The scale bar is 10 μM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

Role of ER stress and UBXD8 HP domain in regulation of peroxisomes. (A) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells were treated with tunicamycin (2.5 μM for 4 h) and stained for catalase. (B) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from A. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ns: not significant, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Rescue of peroxisome number in UBXD8 KO cells transfected with either UBXD8-HA or UBXD8-ΔHP. Cells were stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix marker catalase. (D) Quantification of average peroxisomes per cell from C. Peroxisome numbers were quantified in cells expressing tagged UBXD8 constructs only. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (E) Immunoblots of constructs transfected. The scale bar is 10 μM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

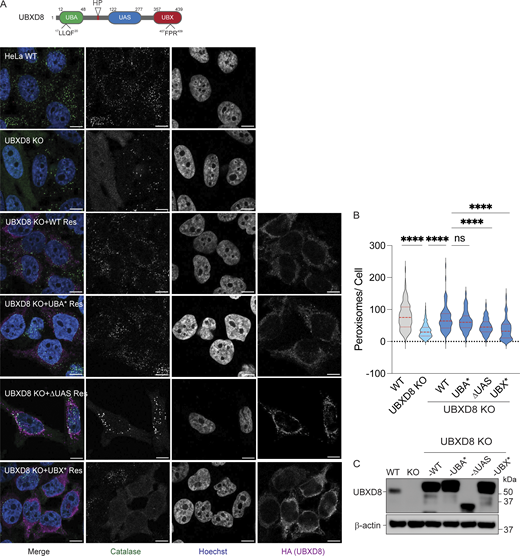

Apart from the UBA and UBX domains, UBXD8 also harbors a HP domain for membrane insertion, a UAS domain that associates with long-chain unsaturated fatty acids (Fig. 4 A) (Ganji et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2013). We asked which of these functions were important in the role of UBXD8 in regulating peroxisome abundance. UBXD8 KO cells were transfected with HA-tagged WT UBXD8 or individual UBA or UBX domain point mutants that we have previously verified to lose interaction with ubiquitin and p97, respectively (Ganji et al., 2023). We also transfected cells with a HP or UAS domain deletion mutant. While the expression of WT UBXD8 and the UBA point mutant rescued peroxisome abundance in UBXD8 KO cells (Fig. 4, A–C), the UBX, HP, or UAS domains did not rescue peroxisome numbers (Fig. 4, A–C and Fig. S3, C–E). Indeed, there were fewer peroxisomes in the HP and UBX mutants compared with KO cells, suggesting that they may be dominant negatives. These results suggest that membrane localization and p97 interaction are important for the role of UBXD8 in maintaining peroxisome abundance.

Role of functional domains in UBXD8 in maintaining peroxisome abundance. (A) Top: schematic of domains in UBXD8. Bottom: complementation of UBXD8 KO cells with WT UBXD8-HA, UBXD8-UBA*-HA, UBXD8-ΔUAS-HA, or UBXD8-UBX*-HA. Cells were stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix marker catalase. (B) Quantification of average peroxisomes per cell from images (A). Peroxisome numbers were quantified in cells expressing low levels of HA-tagged UBXD8 constructs only. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Immunoblots of constructs transfected. The scale bar is 10 μM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Role of functional domains in UBXD8 in maintaining peroxisome abundance. (A) Top: schematic of domains in UBXD8. Bottom: complementation of UBXD8 KO cells with WT UBXD8-HA, UBXD8-UBA*-HA, UBXD8-ΔUAS-HA, or UBXD8-UBX*-HA. Cells were stained for peroxisomes using peroxisomal matrix marker catalase. (B) Quantification of average peroxisomes per cell from images (A). Peroxisome numbers were quantified in cells expressing low levels of HA-tagged UBXD8 constructs only. At least 100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Immunoblots of constructs transfected. The scale bar is 10 μM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

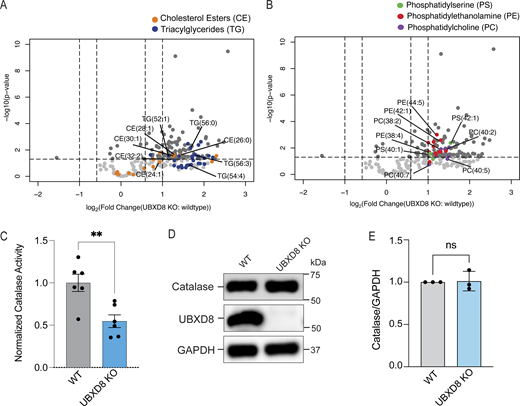

UBXD8 KO cells have dysfunctional peroxisomes

Loss of peroxisomes (e.g., in PBD) causes decreased plasmalogen and cholesterol levels and an accumulation of VLCFAs and phytanic acid (Aubourg and Wanders, 2013; Faust and Kovacs, 2014). We had previously performed lipidomics in WT and UBXD8 KO cells and reanalyzed that dataset to evaluate acyl chain lengths in the major classes of lipids. We observed a significant accumulation of very long-chain fatty acyl chains in cholesterol esters (CE), triacylglycerides (TG), and distinct phospholipid species in UBXD8 KO cells compared with WT cells (Fig. 5, A and B). These lipids were conjugated with acyl chains ranging from 28 to 56 hydrocarbons, indicating an increase in VLCFAs (Fig. 5, A and B). We also investigated peroxisome function by evaluating catalase activity in WT and UBXD8 KO cells and observed a decrease in catalase activity in UBXD8 KO cells compared with WT cells (Fig. 5 C). However, catalase levels were comparable between WT and UBXD8 KO cells likely due to the known redistribution of catalase to the cytoplasm in cells lacking peroxisomes (Fig. 5, D and E). Thus, the loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 KO cells leads to dysfunctional peroxisomes with perturbed lipid metabolism and decreased catalase activity.

Depletion of UBXD8 results in an increase of VLCFAs and a loss in catalase activity. (A) Volcano plot of the total CE and triacylglycerol species identified using lipidomics of whole-cell extracts of HEK293T cells (−log10-transformed P value versus the log2-transformed ratio of UBXD8 KO to WT). VLCFA species indicated for CE (orange) and TG (dark blue). This dataset has been previously published in Ganji et al. (2023) and is reanalyzed here. (B) VLCFA species indicated for PS (green), PE (red), and PC (violet). Lipids were measured by LC-MS/MS following normalization by total protein amount (n ≥ 3 biologically independent experiments were performed, each with duplicate samples). This dataset has been previously published (Ganji et al., 2023) and is reanalyzed here. (C) Catalase activity in WT and UBXD8 KO cells was quantified using a commercial kit. N = 3 independent experiments. **P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (D) Immunoblots of catalase levels in whole-cell lysates of HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells. (E) Quantification of catalase levels in D. N = 3 independent experiments. ns: not significant, unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Depletion of UBXD8 results in an increase of VLCFAs and a loss in catalase activity. (A) Volcano plot of the total CE and triacylglycerol species identified using lipidomics of whole-cell extracts of HEK293T cells (−log10-transformed P value versus the log2-transformed ratio of UBXD8 KO to WT). VLCFA species indicated for CE (orange) and TG (dark blue). This dataset has been previously published in Ganji et al. (2023) and is reanalyzed here. (B) VLCFA species indicated for PS (green), PE (red), and PC (violet). Lipids were measured by LC-MS/MS following normalization by total protein amount (n ≥ 3 biologically independent experiments were performed, each with duplicate samples). This dataset has been previously published (Ganji et al., 2023) and is reanalyzed here. (C) Catalase activity in WT and UBXD8 KO cells was quantified using a commercial kit. N = 3 independent experiments. **P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (D) Immunoblots of catalase levels in whole-cell lysates of HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells. (E) Quantification of catalase levels in D. N = 3 independent experiments. ns: not significant, unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

UBXD8 localizes to peroxisomes

While UBXD8 is localized to the ER, recent studies have demonstrated that endogenous UBXD8 can also localize to mitochondria and lipid droplets to regulate organelle function (Olzmann et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2022). Intriguingly, a recent proteomics analysis of purified peroxisomes identified UBXD8 as a putative peroxisome-localized protein (Ray et al., 2020). We therefore asked whether UBXD8 could localize to peroxisomes. We transiently transfected COS-7 and HeLa cells with UBXD8-GFP and RFP-SKL (a type 1 peroxisome targeting sequence). Cells were also labeled with BODIPY (665/676) to label lipid droplets. As previously reported, GFP-UBXD8 was seen on the surface of lipid droplets (Fig. 6, A and C). Notably, we observed robust localization of UBXD8 to peroxisomes (Fig. 6, A–D). We also observed endogenous UBXD8 localized to peroxisomes (Fig. 6, E and F). We do not observe endogenous UBXD8 forming rings around lipid droplets as we observed for overexpressed UBXD8. Previous studies have reported that UBXD8 migrates to lipid droplets from the ER when it is overexpressed as it can no longer bind to its ER retention factor UBAC2 which is limiting in cells (Olzmann et al., 2013). Our data suggest that UBXD8 is unique among p97 adaptors in its ability to localize to distinct organelle membranes including peroxisomes. However, further studies are needed with improved resolution to understand whether UBXD8 localizes to peroxisome membranes or to ER–peroxisome membrane contacts. If UBXD8 does localize directly to peroxisomes, the players that mediate its localization also remain to be determined (see Discussion).

UBXD8 localizes to peroxisomes. (A) Airyscan images of COS-7 cells transfected with GFP-UBXD8 and RFP-SKL and stained with BODIPY (665/676) to label lipid droplets. (B) Quantification of RFP-SKL colocalization to GFP-UBXD8 by Mander’s colocalization coefficient. Error bars indicate the mean ± SE, COS-7 cells (n = 17) and HeLa cells (n = 8). The RFP channel is rotated 90° right to quantify random colocalization. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. The scale bar is 2 μM. (C and D) Identical to A and B except in HeLa cells. (E) Airyscan images of HeLa cells transfected with GFP-SKL and stained for endogenous UBXD8. (F) Quantification of GFP-SKL colocalization to endogenous UBXD8 by Mander’s colocalization coefficient. Error bars indicate the mean ± SE, n = 13. The GFP channel is rotated 90° right to quantify random colocalization. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. The scale bar is 5 μM.

UBXD8 localizes to peroxisomes. (A) Airyscan images of COS-7 cells transfected with GFP-UBXD8 and RFP-SKL and stained with BODIPY (665/676) to label lipid droplets. (B) Quantification of RFP-SKL colocalization to GFP-UBXD8 by Mander’s colocalization coefficient. Error bars indicate the mean ± SE, COS-7 cells (n = 17) and HeLa cells (n = 8). The RFP channel is rotated 90° right to quantify random colocalization. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. The scale bar is 2 μM. (C and D) Identical to A and B except in HeLa cells. (E) Airyscan images of HeLa cells transfected with GFP-SKL and stained for endogenous UBXD8. (F) Quantification of GFP-SKL colocalization to endogenous UBXD8 by Mander’s colocalization coefficient. Error bars indicate the mean ± SE, n = 13. The GFP channel is rotated 90° right to quantify random colocalization. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. The scale bar is 5 μM.

p97-UBXD8 suppresses peroxisome degradation via pexophagy

Given the role of p97-UBXD8 in extracting and degrading organelle localized membrane proteins and the loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 KO cells, we asked whether this complex participated in pexophagy. We used a peroxisomal flux reporter consisting of a tandem eGFP and mCherry chimera fused to the transmembrane domain of PEX26 (Deosaran et al., 2013; Pankiv et al., 2007). Both mCherry and eGFP fluorescence (yellow puncta) are observed for functional peroxisomes or those residing in autophagosomes. However, peroxisomes in lysosomes only harbor the mCherry signal as the eGFP fluorophore is quenched in the acidic lumen of the lysosome (Fig. 7 A). WT and UBXD8 KO cells were transiently transfected with eGFP-mCherry-PEX26, and cells were treated with Torin1, a pan-mTOR inhibitor to stimulate pexophagy. As expected, Torin1 treatment resulted in the activation of pexophagy and the loss of peroxisomes in WT cells and UBXD8 KO cells (Fig. S4, A and B). We quantified the ratio of eGFP to mCherry and identified a significant loss in eGFP signal in UBXD8 KO cells compared with WT cells under basal conditions, which was further stimulated in the presence of Torin1 (Fig. 7, B and C). To assess the role of p97 in this process, we used siRNA to knock down p97 and showed that the loss of p97 also enhanced pexophagy in untreated and Torin1-treated cells (Fig. 7, D and F). To determine whether p97 ATPase activity was necessary for suppressing pexophagy, we treated cells expressing the flux reporter with CB-5083, a highly potent and selective inhibitor of p97 that targets the D2 ATPase domain of p97 (Anderson et al., 2015). Cells treated with 10 μM CB-5083 for 2 h showed enhanced pexophagy, indicating that p97 catalytic activity is necessary for this process (Fig. 7 G). Together, our results suggest that both p97 and UBXD8 suppress peroxisome degradation through pexophagy.

p97-UBXD8 suppresses peroxisome flux through autophagy. (A) Schematic for pexophagy flux reporter eGFP-mCherry-PEX26. (B) Representative images of WT and UBXD8 KO cells transfected with eGFP-mCherry-PEX26. (C) WT and UBXD8 KO cells were transfected with the flux reporter and treated with 150 nM Torin1 for 18 h. Quantification showing the ratio of eGFP to (eGFP+mCherry+) in HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test. (D) Representative images of HeLa control or p97 siRNAs and eGFP-mCherry-PEX26. (E) Quantification showing the ratio of eGFP to (eGFP+mCherry+) in HeLa control, or p97-depleted cells. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (F) Immunoblot showing p97 depletion. (G) Quantification showing the ratio of eGFP to (eGFP+mCherry+) in HeLa untreated, or CB5083 (10 μM for 2 h)-treated cells. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. **P < 0.001, unpaired t test. The scale bar is 10 μM and 5 μM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

p97-UBXD8 suppresses peroxisome flux through autophagy. (A) Schematic for pexophagy flux reporter eGFP-mCherry-PEX26. (B) Representative images of WT and UBXD8 KO cells transfected with eGFP-mCherry-PEX26. (C) WT and UBXD8 KO cells were transfected with the flux reporter and treated with 150 nM Torin1 for 18 h. Quantification showing the ratio of eGFP to (eGFP+mCherry+) in HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test. (D) Representative images of HeLa control or p97 siRNAs and eGFP-mCherry-PEX26. (E) Quantification showing the ratio of eGFP to (eGFP+mCherry+) in HeLa control, or p97-depleted cells. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (F) Immunoblot showing p97 depletion. (G) Quantification showing the ratio of eGFP to (eGFP+mCherry+) in HeLa untreated, or CB5083 (10 μM for 2 h)-treated cells. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. **P < 0.001, unpaired t test. The scale bar is 10 μM and 5 μM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Role of autophagy in UBXD8 regulation of peroxisome numbers. (A) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells were treated with Torin1 (1 mM for 16 h) stained for peroxisomes using catalase. (B) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell. 100–150 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells were depleted of ATG5 using siRNA. Cells were stained for peroxisomes using catalase. (D) Quantification of peroxisome abundance from A. 100–150 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (E) Immunoblot showing ATG5 depletion. (F) Immunoblot showing HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells treated with Torin1 (1 mM for 4 h) and bafilomycin A (50 nM for 4 h) indicating UBXD8 stabilization. Scale bars are 5 μM (A) and 10 μM (C). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Role of autophagy in UBXD8 regulation of peroxisome numbers. (A) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells were treated with Torin1 (1 mM for 16 h) stained for peroxisomes using catalase. (B) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell. 100–150 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells were depleted of ATG5 using siRNA. Cells were stained for peroxisomes using catalase. (D) Quantification of peroxisome abundance from A. 100–150 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (E) Immunoblot showing ATG5 depletion. (F) Immunoblot showing HeLa WT and UBXD8 KO cells treated with Torin1 (1 mM for 4 h) and bafilomycin A (50 nM for 4 h) indicating UBXD8 stabilization. Scale bars are 5 μM (A) and 10 μM (C). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

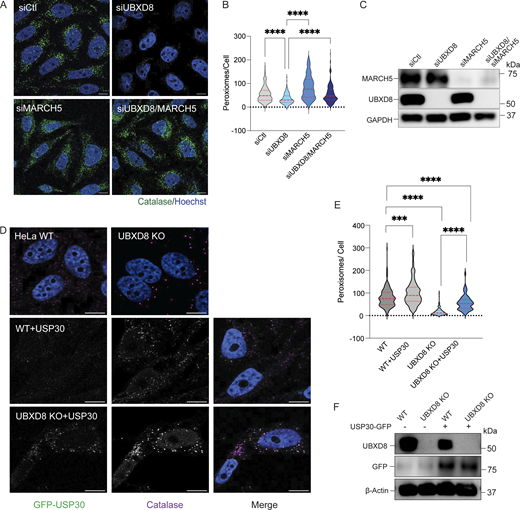

Depletion of autophagy factors ATG5 and NBR1 rescues the pexophagy defect in UBXD8 loss-of-function cells

To confirm that increased autophagy was responsible for the loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 loss-of-function cells, we depleted ATG5, an essential autophagy protein responsible for phagophore elongation (Kuma et al., 2004; Mizushima et al., 2001). We found that codepletion of ATG5 in UBXD8 knockdown cells resulted in a significant increase in peroxisome number (Fig. 8, A and C). Similarly, siRNA depletion of ATG5 in UBXD8 KO cells also rescued peroxisome numbers (Fig. S4, C and E). To further explore the role of autophagy, we depleted cells of NBR1, a key autophagy receptor for pexophagy (Deosaran et al., 2013). Depletion of NBR1 in UBXD8-depleted cells rescued peroxisome numbers to WT levels (Fig. 8, D and F). We also immunostained WT and UBXD8 KO cells for NBR1 and catalase and observed increased colocalization of peroxisomes with NBR1 in UBXD8 KO cells (Fig. 8, G and H). Immunoblot analysis further demonstrates that UBXD8 protein levels are stabilized following lysosomal inhibition with bafilomycin A, consistent with UBXD8 being subject to lysosomal turnover during pexophagy (Fig. S4 F). Taken together, our results demonstrate that the loss of peroxisomes upon UBXD8 deletion is via autophagy.

Depletion of ATG5 and overexpression of USP30 rescue pexophagy in UBXD8 KO cells. (A) Representative images of HeLa cells transfected with control, UBXD8, and ATG5 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (B) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from A. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Immunoblot of UBXD8 and ATG5 depletion. (D) Representative images of HeLa cells transfected with control, UBXD8, or NBR1 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (E) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from D. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. Violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (F) Immunoblot of UBXD8 and NBR1 depletion. (G) WT and UBXD8 KO HeLa cells were stained with NBR1 and catalase. (H) Mander’s colocalization of images in G. 100–120 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. The scale bar is 10 μM (A and D) and 5 μM (D and G). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F8.

Depletion of ATG5 and overexpression of USP30 rescue pexophagy in UBXD8 KO cells. (A) Representative images of HeLa cells transfected with control, UBXD8, and ATG5 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (B) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from A. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Immunoblot of UBXD8 and ATG5 depletion. (D) Representative images of HeLa cells transfected with control, UBXD8, or NBR1 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (E) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from D. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. Violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (F) Immunoblot of UBXD8 and NBR1 depletion. (G) WT and UBXD8 KO HeLa cells were stained with NBR1 and catalase. (H) Mander’s colocalization of images in G. 100–120 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. The scale bar is 10 μM (A and D) and 5 μM (D and G). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F8.

MARCH5 depletion and overexpression of USP30 rescue pexophagy defect in UBXD8 loss-of-function cells

MARCH5 has recently been identified as an E3 ligase that is dually localized to mitochondria and peroxisomes. At peroxisomes, MARCH5 has been shown to mediate the ubiquitination of PMP70 in Torin1-induced pexophagy (Zheng et al., 2022b). We asked whether depletion of MARCH5 rescues peroxisome loss in UBXD8-depleted cells by preventing ubiquitylation of membrane proteins. Knockdown of MARCH5 increased peroxisome numbers in control cells and was also able to rescue loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8-depleted cells (Fig. 9, A and C). Next, we overexpressed GFP-USP30, a deubiquitylating enzyme that removes ubiquitin from peroxisome membrane proteins to suppress pexophagy during amino acid starvation (Marcassa et al., 2018; Riccio et al., 2019). GFP-USP30 expression in UBXD8 KO cells rescued peroxisome numbers (Fig. 9, D–F). Our results suggest that ubiquitylation of peroxisomal membrane proteins is necessary for the role of UBXD8 in preventing pexophagy.

Depletion of NBR1 and MARCH5 rescues pexophagy in UBXD8 null cells. (A) Representative images of HeLa cells transfected with control, UBXD8, and MARCH5 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (B) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from A. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Immunoblot of UBXD8 and MARCH5 depletion. (D) Representative images of HeLa cells (WT and UBXD8 KO) transfected with GFP-USP30. Cells were stained for catalase. (E) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell in GFP-USP30–transfected cells. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (F) Immunoblot of GFP-USP30 expression. The scale bar is 10 μM (A and D). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F9.

Depletion of NBR1 and MARCH5 rescues pexophagy in UBXD8 null cells. (A) Representative images of HeLa cells transfected with control, UBXD8, and MARCH5 siRNAs and stained for catalase. (B) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell from A. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Immunoblot of UBXD8 and MARCH5 depletion. (D) Representative images of HeLa cells (WT and UBXD8 KO) transfected with GFP-USP30. Cells were stained for catalase. (E) Quantification of peroxisomes per cell in GFP-USP30–transfected cells. 50–100 cells were analyzed in N = 3 independent experiments. The violin plot shows median and 95% confidence intervals. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (F) Immunoblot of GFP-USP30 expression. The scale bar is 10 μM (A and D). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F9.

Persistent PEX5 and PMP70 ubiquitylation in cells depleted of p97-UBXD8

Ubiquitylation of peroxisomal membrane proteins is the signal for pexophagy. A number of studies have demonstrated that the membrane protein PMP70 and the import receptor PEX5 are ubiquitylated under various settings to stimulate pexophagy (Ott et al., 2022, Preprint; Sargent et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2022b). We asked whether depletion of p97 or UBXD8 resulted in persistent ubiquitylation of PEX5 or PMP70. We transfected cells with His-ubiquitin and HA-PEX5 and performed denaturing SDS lysis, followed by HA pulldowns that were probed for ubiquitin. Indeed, loss of p97 or UBXD8 resulted in increased ubiquitylated PEX5 (Fig. 10 B). Similar results were observed for PMP70 upon p97 or UBXD8 depletion (Fig. 10 C). The total abundance of these proteins was also increased in p97-UBXD8–depleted cells (Fig. 10, A and B). Collectively, our studies suggest that loss of p97-UBXD8 causes failure to degrade PMP70 and PEX5, which serves as a signal to degrade peroxisomes via pexophagy (Fig. 10 C).

Persistent PEX5 and PMP70 ubiquitylation in cells depleted of p97-UBXD8. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with His-ubiquitin, PEX5-3xHA, and siRNAs to control, UBXD8, or p97. Cells were lysed in SDS, and denaturing HIS immunoprecipitations were performed. Immunoblots of indicated proteins showing increased ubiquitylation of PEX5 in cells depleted of UBXD8 and p97. N = 3 independent experiments. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-ubiquitin and siRNAs to control, UBXD8, or p97. Cells were lysed in SDS, and denaturing HA immunoprecipitations were performed. Immunoblots of indicated proteins showing increased ubiquitylation of PMP70 in cells depleted of UBXD8 and p97. N = 3 independent experiments. (C) Model showing p97-UBXD8 suppression of pexophagy. UBXD8 on peroxisomes recruits p97 to ubiquitylated peroxisome proteins such as PEX5 and PMP70. p97 ATPase activity extracts and degrades substrates to prevent their recognition by autophagy receptors. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F10.

Persistent PEX5 and PMP70 ubiquitylation in cells depleted of p97-UBXD8. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with His-ubiquitin, PEX5-3xHA, and siRNAs to control, UBXD8, or p97. Cells were lysed in SDS, and denaturing HIS immunoprecipitations were performed. Immunoblots of indicated proteins showing increased ubiquitylation of PEX5 in cells depleted of UBXD8 and p97. N = 3 independent experiments. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-ubiquitin and siRNAs to control, UBXD8, or p97. Cells were lysed in SDS, and denaturing HA immunoprecipitations were performed. Immunoblots of indicated proteins showing increased ubiquitylation of PMP70 in cells depleted of UBXD8 and p97. N = 3 independent experiments. (C) Model showing p97-UBXD8 suppression of pexophagy. UBXD8 on peroxisomes recruits p97 to ubiquitylated peroxisome proteins such as PEX5 and PMP70. p97 ATPase activity extracts and degrades substrates to prevent their recognition by autophagy receptors. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F10.

Discussion

In this study, we find a novel role of p97 and its adaptor UBXD8 in the maintenance of normal peroxisome numbers by suppressing pexophagy. Notably, our study has been corroborated by two recent studies that have reported similar findings (Kim et al., 2024, Preprint; Koyano et al., 2024). Our previous study examining how the proteome was altered by deletion of UBXD8 identified widespread loss of peroxisomal proteins in UBXD8 KO cells (Fig. 1) (Ganji et al., 2023). We show that the loss of peroxisomal proteins in UBXD8 KO cells is due to the significant depletion of peroxisomes (Fig. 2). UBXD8 has been extensively characterized as a p97 adaptor in ERAD. The ER is essential for peroxisome homeostasis and acts as the site for the biogenesis of pre-peroxisomal vesicles (Kim et al., 2006; van der Zand et al., 2012). It is also a donor of membrane lipids via ER–peroxisome contact sites (Joshi, 2021; Kors et al., 2022). Thus, it is possible that peroxisome loss in UBXD8 KO cells is a secondary consequence of perturbed ER function. However, using a suite of complementary studies, we find that the loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8-deficient cells is independent of its role in ERAD (Fig. 3). However, we cannot completely rule out the role of UBXD8 and ERAD in regulating peroxisome numbers. Contact sites between the ER and peroxisomes are reported to provide lipids for the growth of peroxisomal membranes (Joshi, 2021; Kors et al., 2022). The peroxisomal membrane protein acyl-CoA binding domain containing 5 (ACBD5) tethers peroxisomes to the ER through interaction with vesicle-associated membrane protein–associated proteins B (VAPB) (Kors et al., 2022). This tethering complex may help facilitate lipid transport from the ER to peroxisomes. Notably, we have shown that p97-UBXD8 regulates ER–mitochondria contact sites, and UBXD8 is enriched at these contacts (Ganji et al., 2023). It remains to be determined whether UBXD8 also localizes to and regulates ER–peroxisome contacts and warrants future investigation. Importantly, the regulation of peroxisomes by UBXD8 is unique as loss of UBXD2, another ER-localized p97 adaptor, did not impact peroxisomes.

UBXD8 is localized to mitochondria and lipid droplets where it has been demonstrated to recruit p97 for the extraction and degradation of membrane proteins (Olzmann et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2022a). In this study, we determined that UBXD8 localized to peroxisomes (Fig. 6). Intriguingly, a previous study by the Kopito group found that PEX19 was essential for inserting UBXD8 into the ER (Schrul and Kopito, 2016). That study also determined that sites of insertion were in close apposition to peroxisomes using a semi-permeabilized system and in vitro translated UBXD8. While we observe localization of UBXD8 to peroxisomes, given the resolution limitation of our imaging studies, it is possible that these peroxisomes may be in contact with ER-localized UBXD8. Notably, the recent study by Koyano et al. also showed that UBXD8 is localized to peroxisomes using similar approaches used in our studies (Koyano et al., 2024). Higher resolution studies such as immuno-EM, biochemical purification of peroxisomes, and super-resolution imaging will support our findings that UBXD8 may be localized to peroxisome membranes. These findings will enable studies to identify how UBXD8 is inserted into peroxisomes, either directly after translation or by migration from the ER via pre-peroxisomal vesicles. While we did not identify changes in PEX19 protein levels in UBXD8 KO cells from TMT proteomics, which was performed from whole-cell lysates, we did find that its abundance was depleted in immunoblots of whole-cell lysates. We speculate that this may be due to the presence of some PEX19 docked to peroxisomes during client insertion that is then lost upon pexophagy. However, this idea needs to be rigorously tested.

Several lines of evidence support the finding that the loss of peroxisomes in UBXD8 null cells is due to increased pexophagy (Figs. 7, 8, 9, and 10). Using a peroxisomal flux reporter, we show that loss of p97 or UBXD8 increases flux of peroxisomes through autophagy in untreated cells and increases under conditions that stimulate pexophagy. We further show that peroxisome numbers in UBXD8 null cells can be restored to WT levels by depleting the autophagy-initiating protein ATG5 or the autophagy receptor NBR1. The Koyano et al. study showed that the autophagy receptor optineurin in addition to NBR1 facilitates pexophagy (Koyano et al., 2024). p97–adaptor complexes are known to regulate other selective autophagy processes such as mitophagy and lysophagy (Ahlstedt et al., 2022; Papadopoulos et al., 2017; Tanaka et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2022a), so perhaps it is not surprising that it also regulates the selective degradation of peroxisomes. However, we would like to draw a key distinction for the role of p97-UBXD8 in pexophagy versus other forms of selective autophagy. While loss of p97 activity inhibits mitophagy and lysophagy, we find that p97-UBXD8 depletion enhances pexophagy. In mitophagy and lysophagy, p97 mediates the selective extraction of K48-linked ubiquitylated substrates for proteasomal degradation. This degradation may help expose K63-linked ubiquitylated substrates for efficient recruitment of autophagy receptors (Papadopoulos et al., 2017). The ubiquitin linkage types on peroxisomes are largely unexplored. Notably, a recent study demonstrated that another AAA-ATPase, ATAD1, may be involved in the degradation of PEX5 when it cannot be recycled from peroxisomes (Ott et al., 2022, Preprint).

Ubiquitylation of peroxisomal proteins serves as a signal for autophagic degradation. Early studies demonstrated that ubiquitin fused to PEX3 or PMP34 on the peroxisomal membrane was sufficient for the recognition of peroxisomes by the autophagy receptor p62 and NBR1 (Kim et al., 2008). E3 ligases such as PEX2 and MARCH5 and deubiquitylating enzymes such as USP30 maintain peroxisomal pools by balancing ubiquitylation and de-ubiquitylation of membrane proteins (Marcassa et al., 2018; Riccio et al., 2019; Sargent et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2022b). We find that the depletion of MARCH5 or overexpression of USP30 is sufficient to rescue peroxisome number in UBXD8 loss-of-function cells (Fig. 9). Importantly, the depletion of p97 and UBXD8 led to the accumulation of ubiquitin-modified PMP70 and PEX5 (Fig. 10). Our rescue studies (Fig. 4) suggest that the HP, UAS, and UBX domains are important for the role of UBXD8 in inhibiting pexophagy, but the UBA domain is dispensable. This is somewhat surprising since ubiquitin interaction via the UBA domain should be necessary for degradation of substrates to prevent pexophagy. However, prior studies suggest that the UBA domain in UBXD8 may be dispensable for ubiquitin interaction and that other domains in the C terminus such as the coiled coil may be more important for substrate recognition. Indeed, the Koyano et al. study found that deletion of the coiled coil did not rescue peroxisome loss in UBXD8 null cells (Christianson et al., 2011; Fujisawa et al., 2022; Koyano et al., 2024). PMP70 and PEX5 are the most well-characterized peroxisomal proteins whose ubiquitylation triggers pexophagy. Given the promiscuity of other autophagy E3 ubiquitin ligases, there are likely additional peroxisomal membrane proteins that are ubiquitylated to trigger pexophagy that remain to be identified. While a number of studies have systematically identified ubiquitylated proteins on the surface of mitochondria and lysosomes (Kravić et al., 2022; Ordureau et al., 2014; Sargent et al., 2016), this has not been done in the case of peroxisomes. An inventory of these proteins is needed to fully understand the mechanisms regulating pexophagy. Our findings lead to a model wherein E3 ligases ubiquitylate peroxisomal membrane proteins that serve as a signal to recruit autophagy factors to enforce pexophagy. The p97-UBXD8 complex acts as a brake to this process by recognizing ubiquitylated substrates and extracting, unfolding, and degrading them via ATP hydrolysis. This prevents loss of peroxisomes through pexophagy (Fig. 10). Our findings raise many questions, for instance, to what extent does basal ubiquitylation occur on peroxisomes, and what factors trigger this process? What processes suppress p97-UBXD8 function on peroxisomes to promote degradation when warranted, and when is deubiquitylation by USP30 preferred over degradation by the proteasome? Answering these questions is necessary to comprehensively understand peroxisome quality control and its relation to PBDs and other disorders.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatments

HeLa-Flp-IN-TREX (Cat #R71407; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with introduced Flp-In site (Flp-In T-REx Core Kit, Cat #K650001; Thermo Fisher Scientific, a gift from Brian Raught, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada), COS7, and HEK293T (ATCC) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. For siRNA transfections, cells were either forward- or reverse-transfected with 20 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) in a 12- or 6-well plates according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 24 or 48 h, depending on the study, cells were split into 12-well plates for further analysis. 48 or 72 h after transfection, cells were harvested for immunoblot or fixation for immunofluorescence. For DNA transfections, constructs were forward-transfected into cells seeded in either a 6-well or 12-well plate using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). We used 0.5 µg of HA/FLAG-tagged WT UBXD8 or UBA, UAS, and UBX domain deletions or point mutations of the UBA domain (LLQF to AAAA) or UBX domain (FPR to AAA), previously described in Ganji et al. (2023). GFP-USP30 (0.25 µg) (Riccio et al., 2019), RFP-SKL (0.25 µg) (Kim et al., 2006), and GFP-Cherry-PEX26TM (0.5 µg) (Riccio et al., 2019) were all gifts from Peter K. Kim, Senior Scientist at Hospital for Sick Children and Associate Professor in the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. The cells were then harvested 48 or 72 h after transfection. Cells were lysed in mammalian cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, HALT Protease inhibitors [Pierce], and 1 mM DTT). Cells were incubated at 4°C for 10 min and then centrifuged at 19,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was estimated using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad).

Antibodies and chemicals

The p97 (10736-1-AP; WB: 1:2,000), UBXD8 (16251-1-AP; WB: 1:2,000), UBXD2 (21052-1-AP; WB: 1:2,000), HRD1 (13473-1-AP; WB: 1:2,000), AMFR/GP78 (16675-1-AP; WB: 1:2,000), VAPB (14477-1-AP; WB: 1:2,000), PEX5 (12545-1-AP; WB: 1:500), PEX19 (14713-1-AP; WB: 1:1,000), MLYCD (15265-1-AP; WB: 1:2,000), PECR (14901-1-AP; WB: 1:1,000), DECR (25855-1-AP; WB: 1:1,000), PMP70/ABCD3 (66697-1-Ig; WB: 1:1,000; IF: 1:400), PEX3 (10946-1-AP; WB: 1:1,000), ACBD5 (21080-1-AP; WB: 1:1,000), GFP(66002-1-AP; WB: 1:2,000), MARCH5 (12213-1-AP; WB: 1:1,000), and ATG5 (10181-2-AP; WB: 1:1,000) antibodies were from Proteintech Inc. The pan-ubiquitin (P4D1; sc8017; WB: 1:2,000), c-Myc (9E10; sc40; WB: 1:2,000), β-actin (AC-15; sc69879; WB: 1:2,000), and GAPDH (O411; sc47724; WB: 1:2,000) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies. LC3B (D11; 3868S; WB: 1:1,000), catalase (12980; WB: 1:1,000; IF: 1:800), NBR1 (20145; WB: 1:1,000), and BiP (C50B12; 3177T; WB: 1:2,000) were from Cell Signaling Technologies. p97 (A300-589A; WB: 1:2,000) was from Bethyl Laboratories. The following antibodies anti-HA (16B12; MMS-101P, WB: 1:2,500; Covance) and anti-FLAG (M2; F3165; WB: 1:5,000; Sigma-Aldrich) were used for immunoblotting. HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (W401B; WB: 1:10,000) and anti-mouse (W402B; WB: 1:10,000) secondary antibodies were from Promega. Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 (Cat #A-11004; IF: 1:10,000), and Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (Cat #A-11001; IF: 1:10,000) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. CB-5083 was from Selleckchem. siRNAs were purchased from Ambion (Thermo Fisher Scientific): UBXD8-0 (s23260) and UBXD8-9 (s23259). HRD1-3 (D-007090-03) and HRD1-4 (D-007090-04) were purchased from GE Dharmacon. siControl (SIC001) was from MilliporeSigma. MARCH5 (s122980) and NBR1 (s227479) siRNAs were purchased from Invitrogen. p97 siRNAs (2-HSS111263 and 3-HSS111264) and UBXD8-C-HA/FLAG construct were previously published (Raman et al., 2011). The UBXD8 rescue constructs, including UBA* (17LLQF20 mutated to 17AAAA20), ΔUAS (deleted amino acids between 122 and 277), and UBX* (407FPR409 mutated to 407AAA409), were cloned using overlap PCR followed by Gibson assembly (NEB) cloning into pHAGE-C-HA/FLAG. Torin1 (502050475) and clofibrate (08-241-G) are from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Cycloheximide (97064-724) is from VWR International.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

HeLa and HEK293T cells were plated on #1.5 glass coverslips in a 12-well plate. Following the indicated treatments, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (15710-S; Electron Microscopy Sciences) diluted in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Next, cells were washed in PBS and permeabilized in ice-cold 100% methanol at −20°C for 10 min. Cells were washed three times in PBS and incubated in a blocking buffer (1% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies were diluted to the indicated concentrations in blocking buffer, and coverslips were incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Coverslips were washed three times in PBS and incubated in secondary antibodies diluted to the indicated concentrations in a blocking buffer for 1.5 h at room temperature. The secondary antibody solution was replaced with Hoechst diluted in blocking buffer and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Coverslips were washed three times with PBS and mounted to slides with ProLong Gold antifade mounting media (P36930; Invitrogen). All images were collected using a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope equipped with Airyscan using Zeiss Zen Black 2.3 software. Images were taken with an optimal pinhole and a 63× oil immersion objective (NA 1.4) at 25°C. The indicated fluorophores were excited with a 405-, 488-, or 594-nm laser line.

Image analysis

Images were analyzed using FIJI (https://imagej.net/fiji). Peroxisome number per cell and size were measured using an automated image analysis script (AggreCount), allowing segmentation and single-cell resolution (Klickstein et al., 2020). For rescue studies in Fig. 4, we only analyzed peroxisome numbers in cells that expressed low levels of the transfected mutants (based on thresholding) using AggreCount. Since peroxisome numbers can scale with cell size, we measured cell size using CellMask (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and normalized peroxisome numbers to cell size. We found that cell size was consistent between WT and UBXD8 KO cells with and without drug treatment. Furthermore, when peroxisome numbers were normalized to cell area the results were unchanged (data not shown). The ImageJ JACoP plugin was used for colocalization analysis. The total number of peroxisomes in each cell was counted using the ImageJ “analyze particle” tool. Merging images from red and green channels determined peroxisome (red) colocalization with UBXD8 (green). The color threshold tool was used to select yellow puncta (hue value 25–60) that indicate colocalization and were quantified using the ImageJ analyze particle tool.

For flux reporter assays, the background was subtracted and ROIs were generated based on the mCherry signal. ROIs were transferred to the GFP channel, and the GFP intensity was measured. Images in each replicate were carefully examined, and GFP threshold intensity was empirically determined for all images in a given replicate. The number of puncta with GFP above the predetermined intensity was calculated for the ratio.

Sample preparation, digestion, and TMT labeling

The TMT-based proteomics was performed exactly as previously described (Ganji et al., 2023; please refer to the Supplementary Information in that manuscript for the individual datasets). Raw data are available via the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (Perez-Riverol et al., 2022) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD-39061. Briefly, 100 μg protein of each sample was obtained by cell lysis in lysis buffer (8 M urea, 200 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(3-propane sulfonic acid), pH 8.5) followed by reduction using 5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, alkylation with 14 mM iodoacetamide, and quenching using 5 mM DTT. The reduced and alkylated protein was precipitated using methanol and chloroform. The protein mixture was digested with LysC (Wako) overnight, followed by trypsin (Pierce) digestion for 6 h at 37°C. The trypsin was inactivated with 30% (vol/vol) acetonitrile. The digested peptides were labeled with 0.2 mg per reaction of 4-plex TMT reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (126, 127N, 129N, and 129C) at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction was quenched using 0.5% (vol/vol) hydroxylamine for 15 min. A 2.5 μl aliquot from the labeling reaction was tested for labeling efficiency. TMT-labeled peptides from each sample were pooled together at a 1:1 ratio. The pooled peptide mix was dried under vacuum and resuspended in 5% formic acid for 15 min. The resuspended peptide sample was further purified using C18 solid-phase extraction (Sep-Pak, Waters).

Offline basic pH reversed-phase fractionation

We fractionated the pooled, labeled peptide sample using basic pH reversed-phase HPLC (Wang et al., 2011). We used an Agilent 1,200 pump with a degasser and a detector (set at 220- and 280-nm wavelengths). Peptides were subjected to a 50-min linear gradient from 5 to 35% acetonitrile in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8, at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min over an Agilent 300Extend C18 column (3.5 μm particles, 4.6 mm ID and 220 mm in length). The peptide mixture was fractionated into 96 fractions, which were consolidated into 24 super-fractions (Paulo et al., 2016a). Samples were subsequently acidified with 1% formic acid and vacuum-centrifuged to near dryness. Each consolidated fraction was desalted via StageTip, dried again via vacuum centrifugation, and reconstituted in 5% acetonitrile and 5% formic acid for LC-MS/MS processing.

Liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) data were collected on an Orbitrap Lumos mass spectrometer coupled to a Proxeon NanoLC-1000 UHPLC. The 100-µm capillary column was packed with 35 cm of Accucore 150 resin (2.6 μm, 150 Å; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The scan sequence began with an MS1 spectrum (Orbitrap analysis, resolution 120,000, 350–1,400 Th, automatic gain control (AGC) target 5 × 105, maximum injection time 50 ms). Data were acquired for 150 min per fraction. SPS-MS3 analysis was used to reduce ion interference (Gygi et al., 2019; Paulo et al., 2016b). MS2 analysis consisted of collision-induced dissociation, quadrupole ion trap analysis, AGC 1 × 104, normalized collision energy (NCE) 35, q-value 0.25, maximum injection time 60 ms, isolation window at 0.5 Th. Following acquiring each MS2 spectrum, we collected an MS3 spectrum in which multiple MS2 fragment ions were captured in the MS3 precursor population using isolation waveforms with multiple frequency notches. MS3 precursors were fragmented by HCD and analyzed using the Orbitrap (NCE 65, AGC 3.0 × 105, isolation window 1.3 Th, maximum injection time 150 ms, resolution was 50,000). Data are available via ProteomeXchange with the identifier PXD-39061.

Note on ratio compression. Even though peptide abundance is analyzed in MS3 mode, some interference or ratio compression exists in these samples. This can happen when (1) a low abundance protein is being analyzed, and it has very few peptides (low summed signal), (2) the peptides are not ionized well (low overall signal), (3) the protein shares many peptides with other proteins, or (4) there is actual interference from another more signal-dominant peptide that coelutes within the same isolation window, but has a different sequence and originates from a different protein. This is why even though the UBXD8 KO cell line has no detectable UBXD8, there is not an infinite ratio between WT and UBXD8 KO cells for UBXD8 abundance in the volcano plot in Fig. 1. We use both unique and razor (shared) peptides in the calculation of log2 fold change values; however, we have provided a list of all unique and razor peptides identified in Table S1.

Data analysis

Spectra were converted to mzXML via MSconvert (Chambers et al., 2012). Database searching included all entries from the Human UniProt Database (downloaded: August 2018). The database was concatenated with one composed of all protein sequences for that database in the reversed order. Searches were performed using a 50-ppm precursor ion tolerance for total protein-level profiling. The product ion tolerance was set to 0.9 Da. These expansive mass tolerance windows were chosen to maximize sensitivity with Comet searches and linear discriminant analysis (Beausoleil et al., 2006; Huttlin et al., 2010). TMT tags on lysine residues and peptide N termini (+229.163 Da for TMT) and carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.021 Da) were set as static modifications.

In comparison, the oxidation of methionine residues (+15.995 Da) was set as a variable modification. Peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) were adjusted to a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) (Elias and Gygi, 2007; Elias and Gygi, 2010). PSM filtering was performed using a linear discriminant analysis described previously (Huttlin et al., 2010) and then assembled further to a final protein-level FDR of 1% (Elias and Gygi, 2007). Proteins were quantified by summing reporter ion counts across all matching PSMs (McAlister et al., 2012). Reporter ion intensities were adjusted to correct for the isotopic impurities of the different TMT reagents according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The signal-to-noise measurements of peptides assigned to each protein were summed, and these values were normalized so that the sum of the signal for all proteins in each channel was equivalent to account for equal protein loading. Finally, each protein abundance measurement was scaled such that the summed signal to noise for that protein across all channels equaled 100, thereby generating a relative abundance (RA) measurement. Downstream data analyses for TMT datasets were carried out using the R statistical package (v4.0.3) and Bioconductor (v3.12; BiocManager 1.30.10). TMT channel intensities were quantile-normalized, and then, the data were log-transformed. The log-transformed data were analyzed with a limma-based R package, where P values were FDR-adjusted using an empirical Bayesian statistical procedure. Differentially expressed proteins were determined using a log2 (fold change [WT versus UBXD8 KO]) threshold of greater than ±0.65.

Lipidomics: Sample preparation, MS, and identification

HEK293T WT and UBXD8 KO cells were seeded in triplicate for each independent lipidomics experiment. Two of the three samples for each condition were used for lipidomics (i.e., lipids from duplicate samples were extracted and analyzed in parallel to determine technical variation). The third sample was used to determine the total protein concentration. Cells were washed with PBS, scraped into cold 50% methanol, and centrifuged, and the cell pellets were frozen. Next, cells were resuspended in cold 50% methanol and transferred to glass vials. Chloroform was added, gently vortexed, and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Lipids were transferred to a clean glass vial using a glass Hamilton syringe. Lipids were extracted twice using chloroform before being dried under nitrogen gas. Samples were normalized according to protein concentration when resuspended in a 1:1:1 solution of methanol:chloroform: isopropanol before MS analysis. The samples were stored at 4°C in an autosampler during data collection.