Autoantibody-mediated glomerulonephritis (AGN) arises from dysregulated renal inflammation, with urgent need for improved treatments. IL-17 is implicated in AGN and drives pathology in a kidney-intrinsic manner via renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs). Nonetheless, downstream signaling mechanisms provoking kidney pathology are poorly understood. A noncanonical RNA binding protein (RBP), Arid5a, was upregulated in human and mouse AGN. Arid5a−/− mice were refractory to AGN, with attenuated myeloid infiltration and impaired expression of IL-17–dependent cytokines and transcription factors (C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ). Transcriptome-wide RIP-Seq revealed that Arid5a inducibly interacts with conventional IL-17 target mRNAs, including CEBPB and CEBPD. Unexpectedly, many Arid5a RNA targets corresponded to translational regulation and RNA processing pathways, including rRNAs. Indeed, global protein synthesis was repressed in Arid5a-deficient cells, and C/EBPs were controlled at the level of protein rather than RNA accumulation. IL-17 prompted Arid5a nuclear export and association with 18S rRNA, a 40S ribosome constituent. Accordingly, IL-17–dependent renal autoimmunity is driven by Arid5a at the level of ribosome interactions and translation.

Introduction

The global burden of renal disease is substantial and growing, with as many as 10% of adults affected worldwide (Biswas, 2018). Autoantibody-mediated glomerulonephritis (AGN) describes a heterogeneous group of conditions caused by an inappropriate immunopathologic response to renal autoantigens, such as glomerular basement membrane (GBM) protein (Kurts et al., 2013). Although standard treatment with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide increases survival, such regimens are often not effective and can be associated with severe side effects.

Given the enormous medical burden of kidney disease, there is a major unmet need to define immune events that protect the kidney (Lahmer and Heemann, 2012). However, our understanding of organ-specific immune events within the kidney remains relatively underdeveloped. Although the initiators of AGN differ among diseases and are still not well understood, the terminal events in end-organ renal damage share many common hallmarks (Biswas, 2018; Krebs et al., 2017). Elucidating renal immune responses could therefore inform development of treatments with potential applicability to multiple manifestations of glomerulonephritis. Though AGN is often considered to be B cell dependent, T cells are strongly linked to glomerular and tubular damage (Shlomchik et al., 2001). Numerous studies in recent years have implicated the Th17 pathway in driving AGN, both in humans and preclinical animal models, although the clinical potential of IL-17 in kidney has yet to be adequately explored (Biswas, 2018; Doke et al., 2022; Hunemorder et al., 2015; Kurts et al., 2013; Pisitkun et al., 2012).

IL-17 is produced by conventional CD4+ Th17 cells and innate lymphocyte populations (collectively, “Type 17” cells). Since their recognition in 2005, considerable effort has focused on defining mechanisms in T cells that regulate IL-17 production (Majumder and McGeachy, 2021). In contrast, IL-17 mediates downstream signaling on nonhematopoietic cell types, mainly through the IL-17RA–IL-17RC heterodimer, thereby serving as a bridge between the immune system and affected tissues. In experimental models of AGN, IL-17 acts selectively on renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs), which line renal tubules and mediate nutrient absorption and electrolyte balance. In response to injury, RTECs are key sources of the immune effectors that amplify destructive inflammation (Li et al., 2021; Ramani et al., 2018a).

IL-17 is part of a unique subclass of cytokine receptors (Novatchkova et al., 2003), and to date, its mechanisms of signal transduction remain comparatively poorly defined compared to other cytokine families. Much of what is known about IL-17 signaling has come from analysis of its characteristic target gene signature, comprised of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, antimicrobial proteins, and transcriptional/posttranscriptional regulators (Amatya et al., 2017; Bechara et al., 2023; Li et al., 2019; Majumder and McGeachy, 2021). Several of these, including IL-6 and Lcn2 (lipocalin 2, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin), are implicated in kidney disease (Berti et al., 2015; Haase et al., 2011; Su et al., 2017; Viau et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2012) and regulated by the IL-17–inducible CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) transcription factors (TFs) (Maitra et al., 2007; Ruddy et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2023). IL-17 also activates several posttranscriptional signaling pathways, orchestrated by a network of RNA binding proteins (RBPs), but how this circuitry functions is not well understood (Bechara et al., 2023; Li et al., 2019).

Dissecting the specific signaling events that are operative in autoimmunity could in principle provide opportunities for ameliorating disease while sparing host-defensive signaling events. Arid5a (AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 5A) belongs to a family of DNA/RNA helix turn–helix binding proteins (Patsialou et al., 2005) and exerts selective activities in driving Th17/IL-17 autoimmunity. Originally described as a TF, Arid5a was shown to bind and stabilize Il6 mRNA in the context of TLR4 signaling in macrophages (Masuda et al., 2013, 2016). Arid5a similarly stabilizes Il6 and chemokine mRNAs in fibroblasts (Amatya et al., 2018) and stabilizes transcripts that drive Th17 cell differentiation including Il6 and Stat3 (Amatya et al., 2018; Hanieh et al., 2018; Li et al., 2023; Masuda et al., 2013, 2016; Nyati et al., 2017, 2020; Parajuli et al., 2021). Accordingly, mice lacking Arid5a are resistant to experimental models of multiple sclerosis (experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [EAE]) and pancreatitis (Lv et al., 2022; Masuda et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2022). Even so, Arid5a is dispensable for antifungal host defense in candidiasis (Taylor et al., 2023).

Here, we demonstrate that Arid5a is not expressed in healthy kidney but is upregulated in human crescentic glomerulonephritis biopsies and in mouse kidneys in a model AGN, thus pointing to this RBP as a biomarker of this condition. Arid5a−/− mice were fully refractory to pathology in AGN, with abrogated expression of IL-17 signature genes and impaired myeloid cell infiltration to kidney. Arid5a was required for IL-17–dependent induction of C/EBPδ, which drives these inflammatory pathways. IL-17 enhanced nuclear export of Arid5a and prompted its association with ribosomes, most prominently the small (40S) subunit. Transcriptome-wide analysis of Arid5a binding targets by RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (RIP-Seq) revealed unexpectedly that IL-17 treatment specifically promoted binding of Arid5a to RNAs involved in ribosomal RNA (rRNA) processing and translational machinery, including rRNA constituents of 40S and 60S subunits. Moreover, Arid5a deficiency attenuated global translation in RTECs. Thus, AGN is driven and sustained by Arid5a in substantial part through IL-17–inducible association of Arid5a with ribosomes and enhancement of RNA translation.

Results

Arid5a is induced in human and mouse autoantibody-induced kidney disease

Severe AGN is characterized by glomerular crescents comprised of proliferating epithelial cells and tubulointerstitial inflammation (Kurts et al., 2013; McAdoo and Pusey, 2017). To evaluate the IL-17–Arid5a axis in human crescentic GN, the most severe manifestation of this condition, we interrogated public datasets for ARID5A expression in renal biopsies. Consistent with prior reports (Kurts et al., 2013; Velden et al., 2012), IL17RA mRNA was higher in various forms of autoantibody-induced GN compared with healthy tissues (European Renal cDNA Bank, GSE104948). Likewise, ARID5A mRNA was elevated in many of these conditions (Fig. 1 a). We then evaluated ARID5A in renal biopsies by RNAScope in situ hybridization. ARID5A was undetectable in healthy tissues (Fig. 1 b), which is consistent with published datasets in which ARID5A is undetectable in kidney cells and expressed at low levels in renal-associated lymphocytes at homeostasis (Fig. S1, a and b) (Lindstrom et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2019). However, ARID5A was consistently upregulated in renal biopsies from anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated GN patients (Fig. 1 b).

Arid5a is elevated in human and mouse renal epithelium during AGN. (a) The European Renal cDNA Biobank database was interrogated for ARID5A and IL17A mRNA in the following populations (both sexes): IgA nephropathy (n = 27); focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS; n = 18); membranous nephropathy (MN, n = 21); ANCA (n = 22); tumor nephrectomy (n = 5); and healthy control (n = 21). Each symbol indicates one subject, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons, comparing each column to healthy controls. (b) Left: Renal biopsies from patients with ANCA-associated GN or healthy controls were stained with a custom ARID5A probe. Red dots indicate amplified ARID5A mRNA. Representative images are shown. Size bar = 100 µm. Right: Quantitation of RNAScope images. Each symbol represents one individual (control, n = 4; ANCA n = 12). Data show mean ± SEM, analyzed by Student's t test. (c) Timeline of AGN model. IF, immunofluorescence. (d) C57BL/6 WT and Act1−/− mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. Indicated kidney mRNAs were assessed on day 7 by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 4–7), pooled from two independent experiments. (e) Frozen kidney sections from WT mice subjected to AGN for 7 days were stained for DAPI and Arid5a. Representative images indicating renal cortex and medulla are shown. Size bar = 100 µm. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Arid5a is elevated in human and mouse renal epithelium during AGN. (a) The European Renal cDNA Biobank database was interrogated for ARID5A and IL17A mRNA in the following populations (both sexes): IgA nephropathy (n = 27); focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS; n = 18); membranous nephropathy (MN, n = 21); ANCA (n = 22); tumor nephrectomy (n = 5); and healthy control (n = 21). Each symbol indicates one subject, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons, comparing each column to healthy controls. (b) Left: Renal biopsies from patients with ANCA-associated GN or healthy controls were stained with a custom ARID5A probe. Red dots indicate amplified ARID5A mRNA. Representative images are shown. Size bar = 100 µm. Right: Quantitation of RNAScope images. Each symbol represents one individual (control, n = 4; ANCA n = 12). Data show mean ± SEM, analyzed by Student's t test. (c) Timeline of AGN model. IF, immunofluorescence. (d) C57BL/6 WT and Act1−/− mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. Indicated kidney mRNAs were assessed on day 7 by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 4–7), pooled from two independent experiments. (e) Frozen kidney sections from WT mice subjected to AGN for 7 days were stained for DAPI and Arid5a. Representative images indicating renal cortex and medulla are shown. Size bar = 100 µm. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Arid5a expression in human and murine AGN (associated with Figs. 1 and 2 ). (a)ARID5A levels according to the Human Cell Atlas single-cell RNA-Seq datasets (Stewart et al., 2019). ARID5A and ATP1A1 (ATPase Na+/K+ transporting subunit α1) are indicated, analyzed by Adifa. PT, proximal tubule. dPT, distinct proximal tubule. EPC, epithelial progenitor cell. PC, principal cell. PE, pelvic epithelium. TE, transitional epithelium of ureter. CNT, connecting tubule. LOH, loop of Henle. IC, intercalated cells. podo, podocyte. Fib, fibroblast. MFib, myofibroblast. GE, glomerular endothelium. DVRE/AVRE, descending/ascending vasa recta endothelium. PCE, peritubular capillary endothelium. NK, natural killer. (b)ARID5A and ATP1A1 in the Human Nephrogenesis Atlas by single-cell RNA-Seq (Lindström et al., 2021). (c) Mice were given PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN and analyzed on day 7. qPCR analysis of Zc3h12a normalized to Gapdh. Each symbol represents one mouse. Results were pooled from two independent experiments (n = 2–6). Analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. (d) Sections from WT and Arid5a−/− kidneys were stained for DAPI and anti-Arid5a by IF. Representative images are shown. Scale bar = 500 µm. (e) Mice were given PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN and analyzed on day 7. Serum BUN was assessed by ELISA. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Results were pooled from two independent experiments (n = 5–7). (f) Indicated mRNAs in kidney were assessed on day 7 by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–7) pooled from two independent experiments. (g) Mice were administered PBS or AA1, and serum BUN was assessed by ELISA on day 6. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 6–9), pooled from two to three independent experiments. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. *P < 0.05, **** < 0.0001.

Arid5a expression in human and murine AGN (associated with Figs. 1 and 2 ). (a)ARID5A levels according to the Human Cell Atlas single-cell RNA-Seq datasets (Stewart et al., 2019). ARID5A and ATP1A1 (ATPase Na+/K+ transporting subunit α1) are indicated, analyzed by Adifa. PT, proximal tubule. dPT, distinct proximal tubule. EPC, epithelial progenitor cell. PC, principal cell. PE, pelvic epithelium. TE, transitional epithelium of ureter. CNT, connecting tubule. LOH, loop of Henle. IC, intercalated cells. podo, podocyte. Fib, fibroblast. MFib, myofibroblast. GE, glomerular endothelium. DVRE/AVRE, descending/ascending vasa recta endothelium. PCE, peritubular capillary endothelium. NK, natural killer. (b)ARID5A and ATP1A1 in the Human Nephrogenesis Atlas by single-cell RNA-Seq (Lindström et al., 2021). (c) Mice were given PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN and analyzed on day 7. qPCR analysis of Zc3h12a normalized to Gapdh. Each symbol represents one mouse. Results were pooled from two independent experiments (n = 2–6). Analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. (d) Sections from WT and Arid5a−/− kidneys were stained for DAPI and anti-Arid5a by IF. Representative images are shown. Scale bar = 500 µm. (e) Mice were given PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN and analyzed on day 7. Serum BUN was assessed by ELISA. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Results were pooled from two independent experiments (n = 5–7). (f) Indicated mRNAs in kidney were assessed on day 7 by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–7) pooled from two independent experiments. (g) Mice were administered PBS or AA1, and serum BUN was assessed by ELISA on day 6. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 6–9), pooled from two to three independent experiments. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. *P < 0.05, **** < 0.0001.

We next evaluated Arid5a expression and function in a murine preclinical model of AGN that recapitulates the key hallmarks of crescentic kidney disease. Disease is generated by immunization with rabbit IgG followed by rabbit anti-GBM protein serum (Biswas, 2018; Krebs et al., 2017), triggering tubular inflammation, glomerular crescent formation, and kidney dysfunction. Pathology is dependent on IL-17RA signaling through Act1 (Fig. 1 c) (Hunemorder et al., 2015; Krohn et al., 2018; Paust et al., 2009; Pisitkun et al., 2012; Ramani et al., 2014; Riedel et al., 2016). In this setting, Arid5a was induced in an IL-17–dependent manner as Act1−/− mice showed impaired Arid5a induction in nephritic kidney. This was accompanied by a reduced IL-17 signature, e.g., IL6, Lcn2, and Zc3h12a (Regnase-1) (Fig. 1 d and Fig. S1 c). Similar to ANCA-GN patients, Arid5a protein was undetectable at homeostasis but elevated in RTECs during AGN (Fig. 1 e and Fig. S1 d). Thus, Arid5a is prominently expressed in AGN in the major IL-17–responsive cell type of the kidney.

Arid5a potentiates AGN pathology

Arid5a−/− mice (Taylor et al., 2022) were next evaluated for kidney pathology after AGN induction. At baseline, Arid5a−/− mice exhibited no obvious renal impairment, showing normal levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine, with no detectable expression of Arid5a in the kidney (Fig. 2, a and b). BUN and creatinine were elevated in WT but not Arid5a−/− mice following AGN, assessed at days 7 and 14 (Fig. 2 a and Fig. S1 e). Histological assessment showed reduced numbers of abnormal glomeruli in Arid5a−/− mice (Fig. 2 a). IL-17–associated mRNAs linked to AGN were not upregulated in Arid5a−/− kidneys, such as Il6, chemokines (Ccl2, Ccl20, Cxcl1), damage markers (Lcn2, Kim1), and Il17a (Fig. 2 b and Fig. S1 f). Monocytes (CDllb+Ly6C+Ly6G−) and macrophages (F4/80+CDllb+) were also reduced in Arid5a−/− renal tissue (Fig. 2 c and Fig. S2, a and b), commensurate with impaired expression of Ccl2 (MCP1) (Fig. S1 f). Although Il17a was diminished in human and murine AGN (Fig. 1 a and Fig. 2 b), the numbers and frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells infiltrating kidney were not altered in Arid5a-deficient animals. Similarly, there were no changes in dendritic cell (DC) or neutrophil cell numbers (Fig. S2, c and d).

Arid5a is required for AGN pathology. The indicated mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. (a) Top: Serum BUN and creatinine were evaluated by ELISA on day 14. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–8) pooled from two independent experiments. Bottom: H&E staining of kidney sections with clinical scoring. Representative images are shown. Size bar = 200 µm. Percent of abnormal glomeruli within each field is indicated. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 3–4). Data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. (b) Indicated mRNAs in kidney were assessed on day 7 by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–7) pooled from two independent experiments. (c) C57BL/6 WT and Arid5a−/− mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. Kidneys were analyzed on day 7. Representative flow cytometry plots and percentages are shown for macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+) and inflammatory monocytes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−). Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–7), pooled from two independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. (d) C57BL/6 WT or Arid5a−/− mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with femoral BM from reciprocal donors. After 6 wk, mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. On day 14, serum BUN and creatinine were measured by ELISA. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 7–8) pooled from two independent experiments. Data analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Arid5a is required for AGN pathology. The indicated mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. (a) Top: Serum BUN and creatinine were evaluated by ELISA on day 14. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–8) pooled from two independent experiments. Bottom: H&E staining of kidney sections with clinical scoring. Representative images are shown. Size bar = 200 µm. Percent of abnormal glomeruli within each field is indicated. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 3–4). Data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. (b) Indicated mRNAs in kidney were assessed on day 7 by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–7) pooled from two independent experiments. (c) C57BL/6 WT and Arid5a−/− mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. Kidneys were analyzed on day 7. Representative flow cytometry plots and percentages are shown for macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+) and inflammatory monocytes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−). Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–7), pooled from two independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. (d) C57BL/6 WT or Arid5a−/− mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with femoral BM from reciprocal donors. After 6 wk, mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. On day 14, serum BUN and creatinine were measured by ELISA. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 7–8) pooled from two independent experiments. Data analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Immune cell levels in Arid5a −/− mice during AGN (associated with Figs. 2 and 3 ). WT and Arid5a−/− mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. On day 7, renal homogenates were analyzed by flow cytometry. (a) Gating strategy for flow cytometry. (b) Total numbers of macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+) and inflammatory monocytes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−). (c) Total numbers of DCs, neutrophils, CD4+, and CD8+ cells. (d) Percentage of the indicated subpopulations within CD45+ subset. Results were pooled from two independent experiments (n = 5–7). Data analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01.

Immune cell levels in Arid5a −/− mice during AGN (associated with Figs. 2 and 3 ). WT and Arid5a−/− mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. On day 7, renal homogenates were analyzed by flow cytometry. (a) Gating strategy for flow cytometry. (b) Total numbers of macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+) and inflammatory monocytes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−). (c) Total numbers of DCs, neutrophils, CD4+, and CD8+ cells. (d) Percentage of the indicated subpopulations within CD45+ subset. Results were pooled from two independent experiments (n = 5–7). Data analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01.

Arid5a has documented activities in many immune cell types (Masuda et al., 2013, 2016; Nyati et al., 2020), in contrast to IL-17, which functions in non-hematopoietic cells (Li et al., 2019; Majumder and McGeachy, 2021). To determine where Arid5a function is required in AGN, femoral bone marrow (BM) was adoptively transferred from WT or Arid5a−/− mice into reciprocal, lethally irradiated hosts. After engraftment, mice were subjected to AGN. WT mice receiving WT or Arid5a−/− BM exhibited similar degrees of kidney dysfunction, whereas Arid5a−/− hosts were resistant to disease signs regardless of BM source (Fig. 2 d). Thus, the contributions of Arid5a in murine AGN occur within a radioresistant cellular compartment.

Given its inducibility in kidney, we asked whether Arid5a participates in fibrotic renal damage, triggered experimentally by administration of aristolochic acid 1 (AA1), a nephrotoxin found in traditional herbal medicines (Eddy, 2014). Arid5a−/− mice given AA1 showed the same degree of kidney damage as WT controls (Fig. S1 g), indicating that Arid5a is not required for the fibrotic process, and is consistent with findings that IL-17R signaling is not required for kidney fibrosis in this model (Ramani et al., 2018b; Dey et al., 2024).

Arid5a is documented to drive cell growth (Anwar et al., 2018), prompting us to ask whether the kidney pathology observed was due to impaired proliferative processes. However, there were no changes in proliferation, cell cycle frequency, or apoptosis in WT versus Arid5a−/− renal cells (CD45−CD133+) during AGN, determined by Ki67 staining or BrdU incorporation (Fig. 3, a–c). Similarly, proliferation of cultured Arid5a−/− primary fibroblasts was indistinguishable from WT controls and did not change with IL-17 treatment (Fig. 3 d). Arid5a−/− fibroblasts were also able to fill an artificial gap in a cell monolayer with normal kinetics (Liang et al., 2007) (Fig. 3 e). Thus, Arid5a does not affect proliferation of renal cells or fibroblasts in the context of AGN or IL-17 signaling.

Cell proliferation is not altered in the absence of Arid5a. (a) C57BL/6 WT and Arid5a−/− mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. On day 7, renal cell proliferation was determined by staining for CD45−CD133+Ki67+ absolute cell number (left) and percentages (right) in the CD45− population. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 3–4). (b) BrdU was injected i.p. on 6 days after AGN induction. On day 7, renal cell homogenates were assessed by flow cytometry. CD133−CD45+ (top) and CD133+CD45− (bottom). (c) Percentage of cells within the indicated cell cycle stages in CD133+CD45− (left) and CD133−CD45+ (right) populations were quantified. Data analyzed by ordinary one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 2–3). (d) Representative Ki-67 staining in WT or Arid5a−/− primary fibroblasts isolated from mouse ear and treated ± IL-17 (200 ng/ml) for 3 or 6 h. Plot is representative of three independent experiments. (e) WT and Arid5a−/− primary ear fibroblasts were plated and recovered in a standard scratch assay was monitored at the indicated time points. Each number represents one monitored area (n = 18), pooled from six independent samples. Data analyzed by two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test with no significant differences observed between WT and Arid5a−/− cells. Representative images are shown. Scale bar = 400 µm.

Cell proliferation is not altered in the absence of Arid5a. (a) C57BL/6 WT and Arid5a−/− mice were administered PBS (Control) or subjected to AGN. On day 7, renal cell proliferation was determined by staining for CD45−CD133+Ki67+ absolute cell number (left) and percentages (right) in the CD45− population. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 3–4). (b) BrdU was injected i.p. on 6 days after AGN induction. On day 7, renal cell homogenates were assessed by flow cytometry. CD133−CD45+ (top) and CD133+CD45− (bottom). (c) Percentage of cells within the indicated cell cycle stages in CD133+CD45− (left) and CD133−CD45+ (right) populations were quantified. Data analyzed by ordinary one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 2–3). (d) Representative Ki-67 staining in WT or Arid5a−/− primary fibroblasts isolated from mouse ear and treated ± IL-17 (200 ng/ml) for 3 or 6 h. Plot is representative of three independent experiments. (e) WT and Arid5a−/− primary ear fibroblasts were plated and recovered in a standard scratch assay was monitored at the indicated time points. Each number represents one monitored area (n = 18), pooled from six independent samples. Data analyzed by two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test with no significant differences observed between WT and Arid5a−/− cells. Representative images are shown. Scale bar = 400 µm.

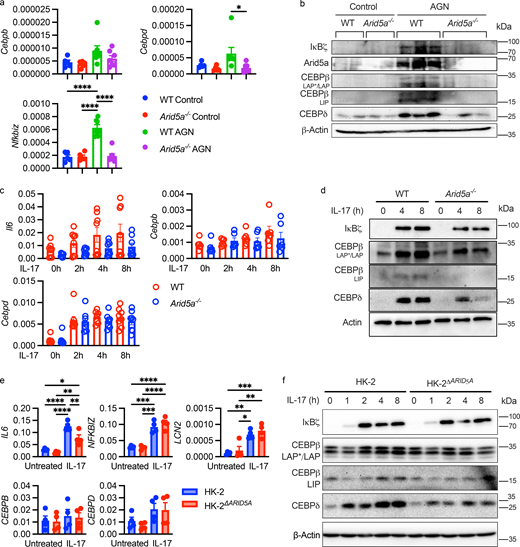

Arid5a regulates C/EBP TFs at the level of protein accumulation

IL-17 integrates multiple inflammatory TFs to orchestrate downstream signaling and upregulates C/EBPβ (Cebpb), C/EBPδ (Cebpd), and IκBζ (Nfkbiz) (Bechara et al., 2022; Johansen et al., 2015; Ruddy et al., 2004; Shen et al., 2006, 2009; Taylor et al., 2023; Willems et al., 2016). In kidneys from WT mice, neither Cebpb nor Cebpd mRNA levels were enhanced upon AGN, whereas Nfkbiz was markedly upregulated (Fig. 4 a). Loss of Arid5a did not alter Cebpb levels and affected Cebpd mRNA only marginally. In contrast, Nfkbiz mRNA was strongly reduced in Arid5a−/− mice (Fig. 4 a). However, at the protein level, all three TFs were reduced in the absence of Arid5a (Fig. 4 b and Fig. S3 a). In primary murine RTECs treated with IL-17, Arid5a deficiency similarly led to reduced C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ protein levels without affecting Cebpb or Cebpd mRNA (Fig. 4, c and d). IκBζ was also reduced modestly. Together, these data suggested that Arid5a regulates C/EBPs and IκBζ in nephritic kidney and controls C/EBP accumulation in response to IL-17 mainly at the level of protein rather than mRNA.

Arid5a regulates C/EBP transcription factors. (a) The indicated mice were administered PBS or subjected to AGN. Expression of IL-17–induced TFs in AGN kidney was assessed on day 7 by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–7) pooled from two independent experiments. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. (b) The indicated proteins were assessed in whole kidney homogenates by immunoblotting. Each lane depicts lysates from an individual mouse. (c) Primary RTECs isolated from WT or Arid5a−/− kidneys were stimulated with IL-17. The indicated genes were assessed by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 8), pooled from six independent experiments and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s test for multiple comparisons for each time point. (d) Cell lysates from primary murine RTECs were subjected to immunoblotting. C/EBPβ isoforms: LAP/LAP*, liver enriched activator protein; LIP, liver enriched inhibitor protein. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (e) HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells were stimulated with human IL-17 at the following time points: LCN2 and NFKBIZ at 2 h, IL6, CEBPB, and CEBPD at 8 h. Expression was assessed by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Each symbol represents one sample, pooled from four independent experiments. (f) HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells were treated with IL-17 for the indicated times, and lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. Image representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Arid5a regulates C/EBP transcription factors. (a) The indicated mice were administered PBS or subjected to AGN. Expression of IL-17–induced TFs in AGN kidney was assessed on day 7 by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 5–7) pooled from two independent experiments. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. (b) The indicated proteins were assessed in whole kidney homogenates by immunoblotting. Each lane depicts lysates from an individual mouse. (c) Primary RTECs isolated from WT or Arid5a−/− kidneys were stimulated with IL-17. The indicated genes were assessed by qPCR normalized to Gapdh. Each symbol represents one mouse (n = 8), pooled from six independent experiments and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s test for multiple comparisons for each time point. (d) Cell lysates from primary murine RTECs were subjected to immunoblotting. C/EBPβ isoforms: LAP/LAP*, liver enriched activator protein; LIP, liver enriched inhibitor protein. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (e) HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells were stimulated with human IL-17 at the following time points: LCN2 and NFKBIZ at 2 h, IL6, CEBPB, and CEBPD at 8 h. Expression was assessed by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Each symbol represents one sample, pooled from four independent experiments. (f) HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells were treated with IL-17 for the indicated times, and lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. Image representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Arid5a-mediated C/EBP regulation (associated withFig. 4,). (a) Densitometric quantitation of blots (Fig. 4 b) was determined by ImageJ. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. C/EBPβ isoforms: LAP/LAP*, liver enriched activator protein; LIP, liver enriched inhibitor protein. (b) HK-2 cells were stimulated with human IL-17 for the indicated times, and expression of mRNAs implicated in AGN was measured by qPCR normalized to GAPDH. Each number represents an individual sample, pooled from up to six independent experiments (n = 2–6). Data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s test, comparing each time point to the control (0 h) sample. (c) RNA stabilization was determined by Roadblock-PCR (Watson et al., 2020) in HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells ± IL-17 (200 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Data analyzed by one phase decay best-fit. (d) HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells were treated with human IL-17 at the indicated times. Left: Cytoplasmic or nuclear RNA assessed by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH (cytoplasm) or MALAT1 (nucleus). Right: Validation of cellular fractionation was confirmed by immunoblotting for YY1 (nucleus) or tubulin (cytoplasm). Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Each symbol represents an individual sample (n = 6), pooled from two independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

Arid5a-mediated C/EBP regulation (associated withFig. 4,). (a) Densitometric quantitation of blots (Fig. 4 b) was determined by ImageJ. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. C/EBPβ isoforms: LAP/LAP*, liver enriched activator protein; LIP, liver enriched inhibitor protein. (b) HK-2 cells were stimulated with human IL-17 for the indicated times, and expression of mRNAs implicated in AGN was measured by qPCR normalized to GAPDH. Each number represents an individual sample, pooled from up to six independent experiments (n = 2–6). Data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s test, comparing each time point to the control (0 h) sample. (c) RNA stabilization was determined by Roadblock-PCR (Watson et al., 2020) in HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells ± IL-17 (200 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Data analyzed by one phase decay best-fit. (d) HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells were treated with human IL-17 at the indicated times. Left: Cytoplasmic or nuclear RNA assessed by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH (cytoplasm) or MALAT1 (nucleus). Right: Validation of cellular fractionation was confirmed by immunoblotting for YY1 (nucleus) or tubulin (cytoplasm). Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Each symbol represents an individual sample (n = 6), pooled from two independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

In a human renal proximal tubular epithelial cell line (HK-2) cell line, IL-17 similarly induced a gene signature characteristic of AGN, including ARID5A, IL6, LCN2, ZC3H12A, and NFKBIZ (Fig. S3 b). As in mouse kidney (Fig. 4, a–d), CEBPB and CEBPD mRNAs were not upregulated in response to IL-17 (Fig. 4 e and Fig. S3 b), but their corresponding protein levels were enhanced (Fig. 4 f). HK-2 cells engineered to lack ARID5A (HK-2ΔARID5A) showed impaired IL-17–dependent induction of IL6, though not NFKBIZ or LCN2. As in primary murine RTECs and total kidney, CEBPB, CEBPD, and NFKBIZ steady-state mRNA levels were not changed upon loss of Arid5a (Fig. 4 e), despite a mild reduction in CEBPB and CEBPD transcript longevity (Fig. S3 c). There were also no changes in CEBPD transcript levels in nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts (Fig. S3 d). However, at the protein level, IL-17–mediated induction of C/EBPδ and C/EBPβ was reduced in the absence of Arid5a with no impact on homeostatic baseline levels (Fig. 4 f), while IκBζ protein was unaffected. Together, these data indicate that IL-17 drives AGN through increases in C/EBP TFs that are controlled at the level of protein accumulation.

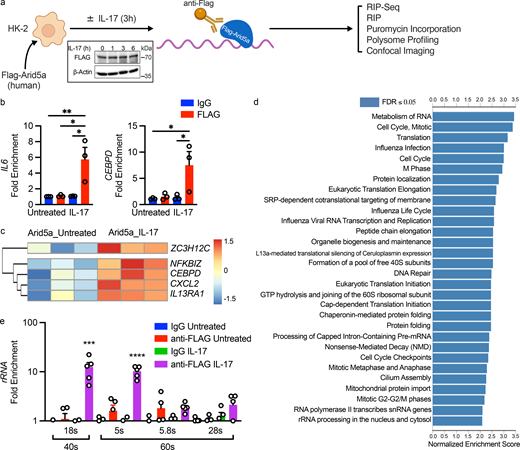

Identification of Arid5a RNA binding targets

RTECs are the most relevant IL-17–responsive renal cells in AGN, based on conditional deletion studies in mice (Li et al., 2021; Ramani et al., 2014). To elucidate the RNA binding activities of Arid5a in AGN, we evaluated its interactions with known IL-17 target transcripts by RIP (Zhu et al., 2023). To facilitate detection, HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated with IL-17 for 3 h and lysates were subjected to RIP with anti-Flag Abs (Fig. 5 a). An advantage of ectopic expression is that Arid5a levels are held constant regardless of cytokine treatment, thereby avoiding any confounding effects of dynamic changes in Arid5a cellular levels (Fig. 5 a, inset) (Amatya et al., 2018; Nyati et al., 2020). Importantly, transfection of Arid5a without IL-17 stimulation did not result in mRNA enrichment in anti-Flag pulldowns compared with control (IgG) pulldowns, showing that simply overexpressing Arid5a did not cause nonspecific interactions with mRNAs. However, following IL-17 treatment, anti-Flag RIPs were significantly enriched for IL6 and CEBPD mRNA (Fig. 5 b), offering proof-of-principle that Arid5a association with known target transcripts can be detected by RIP-Seq.

Identification of Arid5a target transcripts in RTECs. (a) Experimental design. Inset: HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a and treated ± IL-17 for the indicated times. Flag-Arid5a was assessed in cell lysates by immunoblotting, representative of three independent experiments. (b) HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, and enrichment of the indicated mRNAs after RIP was assessed by qPCR. Each symbol represents an individual sample, pooled from three independent experiments. Results were normalized to untreated IgG RIP controls. Data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. (c) HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, and lysates were subjected to RIP-Seq with anti-Flag or IgG isotype controls. Heatmaps show selected inflammatory mRNAs from three independent replicates. (d) GSEA pathway prediction of RIP-Seq comparing untreated and IL-17–treated samples, FDR < 0.05, minimum gene IDs in category = 5. (e) HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, and lysates subjected to RIP. Enrichment of rRNAs corresponding to 40S (18S) and 60S ribosomes (5S, 5.8S, 28S) were determined by qPCR, normalized to untreated IgG RIP controls. Data show mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Data were pooled from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Identification of Arid5a target transcripts in RTECs. (a) Experimental design. Inset: HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a and treated ± IL-17 for the indicated times. Flag-Arid5a was assessed in cell lysates by immunoblotting, representative of three independent experiments. (b) HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, and enrichment of the indicated mRNAs after RIP was assessed by qPCR. Each symbol represents an individual sample, pooled from three independent experiments. Results were normalized to untreated IgG RIP controls. Data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. (c) HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, and lysates were subjected to RIP-Seq with anti-Flag or IgG isotype controls. Heatmaps show selected inflammatory mRNAs from three independent replicates. (d) GSEA pathway prediction of RIP-Seq comparing untreated and IL-17–treated samples, FDR < 0.05, minimum gene IDs in category = 5. (e) HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, and lysates subjected to RIP. Enrichment of rRNAs corresponding to 40S (18S) and 60S ribosomes (5S, 5.8S, 28S) were determined by qPCR, normalized to untreated IgG RIP controls. Data show mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Data were pooled from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

To gain a transcriptome-wide view of IL-17–inducible Arid5a targets, we subjected anti-Flag pulldowns to Illumina sequencing and analyzed data with a customized RNA-Seq pipeline (Materials and methods). Specificity was confirmed by principal component analysis (PCA), which importantly identified no differences between IgG compared with Flag pulldowns (Fig. S4 a). However, IL-17–treated Flag-RIP samples robustly separated from untreated Flag-RIPs and IL-17–treated IgG control RIPs, demonstrating that IL-17 causes selective association of Arid5a with a specific subset of RNAs. Of these, 52% were annotated as coding mRNAs, and the remainder were rRNAs, pseudogenes, long noncoding RNAs, microRNAs, and other noncoding RNA species (Fig. S4 b). Reassuringly, among the IL-17–dependent Arid5a-bound mRNAs identified in this analysis were validated targets such as CEBPD and NFKBIZ (Fig. 5 c) (Amatya et al., 2018; Masuda et al., 2013; Nyati et al., 2020). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed, unexpectedly, that the top annotated pathways corresponded to RNA metabolism, control of translation, and rRNA processing (Fig. 5 d and Fig. S4 c). RIP-quantitative PCR (qPCR) demonstrated that Arid5a bound to 18S rRNA (RNA component of the 40S subunit) and 5S rRNA (60S subunit) (Fig. 5 e). Taken together, these data indicate that Arid5a binds to surprisingly few RNAs at baseline in HK-2 cells, but that IL-17 causes association with IL-17 signature inflammatory mRNAs (including CEBPD), and also to rRNAs and translation-associated transcripts.

Arid5a RIP-Seq analysis in RTECs (associated with Figs. 5 and 6 ). (a) HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated ± IL-17 for 3 h (n = 3). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag Abs or IgG controls and subjected to Illumina sequencing. PCA showing sample heterogeneity among groups captured by gene expression. (b) Biotype distribution of 2788 Arid5a associated RNAs enriched in IL-17–treated group. (c) Genes in Gene Ontology Translation geneset (GO:0006412) in IL-17–treated Arid5a (anti-Flag) pulldowns compared with untreated controls. (d) HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells were treated with IL-17 for 1 h, and cytoplasmic lysates were subjected to sucrose gradient fractionation. Fractions used for qPCR are indicated. (e) Translation efficiency for the indicated transcripts was calculated as the percentage of RNA compared to total RNA in large polysomes (fractions 11–13) or small polysomes (fractions 6–10)/non-polysome (fractions 2–5). Data are representative of two independent experiments. Supt, supernatant.

Arid5a RIP-Seq analysis in RTECs (associated with Figs. 5 and 6 ). (a) HK-2 cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a, treated ± IL-17 for 3 h (n = 3). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag Abs or IgG controls and subjected to Illumina sequencing. PCA showing sample heterogeneity among groups captured by gene expression. (b) Biotype distribution of 2788 Arid5a associated RNAs enriched in IL-17–treated group. (c) Genes in Gene Ontology Translation geneset (GO:0006412) in IL-17–treated Arid5a (anti-Flag) pulldowns compared with untreated controls. (d) HK-2 and HK-2ΔARID5A cells were treated with IL-17 for 1 h, and cytoplasmic lysates were subjected to sucrose gradient fractionation. Fractions used for qPCR are indicated. (e) Translation efficiency for the indicated transcripts was calculated as the percentage of RNA compared to total RNA in large polysomes (fractions 11–13) or small polysomes (fractions 6–10)/non-polysome (fractions 2–5). Data are representative of two independent experiments. Supt, supernatant.

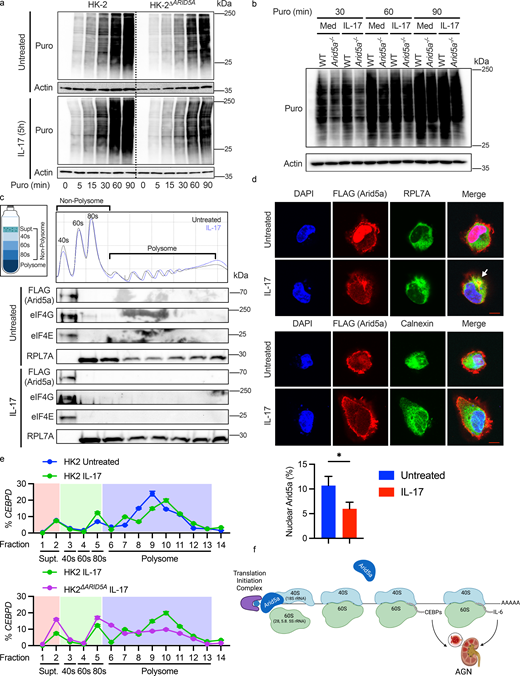

Arid5a interacts with ribosomes and facilitates protein translation

These unexpected RIP-Seq findings coupled with the observation that Arid5a deficiency limits C/EBP accumulation at the protein level raised the possibility that Arid5a augments RNA translation. To measure ongoing protein translation, HK-2 cells and primary murine RTECs were pulse-labeled with puromycin, which covalently incorporates into nascent polypeptide chains, disrupting protein synthesis (Starck et al., 2004). IL-17 alone did not detectably increase puromycin incorporation, which suggests that the bulk of protein synthesis reflected in this assay comes from housekeeping or homeostatic proteins that are not IL-17 inducible. However, there was a significant reduction in puromycin incorporation in Arid5a-deficient cells, supporting the hypothesis that Arid5a facilitates translation in some manner (Fig. 6, a and b). Since Arid5a bound to rRNAs, we assessed its presence in monosomes and polysomes. To that end, HK-2 cells transfected with Arid5a-Flag were treated ± IL-17 and analyzed by sucrose gradient fractionation and immunoblotting (Han et al., 2022). Arid5a was detectable within the 40S (small subunit) fraction, together with translational initiation complex components eIF4G and eIF4E, consistent with our prior report that Arid5a co-IPs with eIF4G (Amatya et al., 2018). Notably, ribosomes can act as protective barriers to limit RNA cleavage, which may explain the modest impact of Arid5a on CEBPB and CEBPD mRNA stabilization (Fig. S3 c) (Carpenter et al., 2014). Even though Arid5a also bound to one 60S rRNA (5S), Flag-Arid5a was not detectable in the 60S fraction (Fig. 5 e), suggesting that interaction of Arid5a with the 60S subunit is likely to be weak or dynamic. In agreement with the ribosome profiling results, confocal imaging showed IL-17–dependent colocalization of Flag-Arid5a with ribosomes (marked by RPL7A), but not with the endoplasmic reticulum (marked by calnexin) (Fig. 6 d). IL-17 also prompted a quantitative shift of Arid5a in subcellular localization from nucleus to cytoplasm, in line with observations made in macrophages in response to LPS (Higa et al., 2018).

Arid5a facilitates protein synthesis in RTECs. (a) HK-2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 5 h, labeled with puromycin, and immunoblotted with anti-puromycin or β-actin Abs, representative of three independent experiments. (b) Primary mouse RTECs were treated ± IL-17 for 5 h and labeled with puromycin. Lysates were immunoblotted with anti-puromycin or β-actin Abs, representative of three independent experiments. Med, media alone. (c) Cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a and treated ± IL-17 for 3 h. Cytoplasmic lysates were separated by sucrose gradient fractionation. Y-axis shows A260 absorbance. Expression of Flag (Arid5a), eIF4G, eIF4E, and RPL7A was assessed in three pooled fractions per sample. Data representative of three independent experiments. (d) HK-2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, stained with DAPI or Abs against Flag, RPL7A, or calnexin, and imaged by confocal microscopy. Size bar = 10 µm. Representative images are shown. Quantitation of nuclear Arid5a is shown below. Each value represents the percentage of colocalized volume from an individual cell (n = 218–225). Arrow denotes region of co-association of Arid5a with RPL7A. Analyzed by Student’s t test. (e) HK-2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 1 h, and CEBPD in two pooled fractions per sample was assessed by qPCR, presented as a percent of total CEBPD from all fractions. Shading: pink denotes supernatant (Supt), green denotes 40S, 60S, and 80S fractions, and blue denotes polysomes. (f) Proposed mechanism of Arid5a function in AGN: Arid5a binds to 18S rRNA (40S ribosome subunit). Arid5a also binds to the 5S rRNA (60S), though interactions are likely weak or transient. Arid5a enhances translational efficiency of CEBPD and IL6 among other RNAs, cumulatively promoting pathology in AGN. *P < 0.05. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Arid5a facilitates protein synthesis in RTECs. (a) HK-2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 5 h, labeled with puromycin, and immunoblotted with anti-puromycin or β-actin Abs, representative of three independent experiments. (b) Primary mouse RTECs were treated ± IL-17 for 5 h and labeled with puromycin. Lysates were immunoblotted with anti-puromycin or β-actin Abs, representative of three independent experiments. Med, media alone. (c) Cells were transfected with Flag-Arid5a and treated ± IL-17 for 3 h. Cytoplasmic lysates were separated by sucrose gradient fractionation. Y-axis shows A260 absorbance. Expression of Flag (Arid5a), eIF4G, eIF4E, and RPL7A was assessed in three pooled fractions per sample. Data representative of three independent experiments. (d) HK-2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, stained with DAPI or Abs against Flag, RPL7A, or calnexin, and imaged by confocal microscopy. Size bar = 10 µm. Representative images are shown. Quantitation of nuclear Arid5a is shown below. Each value represents the percentage of colocalized volume from an individual cell (n = 218–225). Arrow denotes region of co-association of Arid5a with RPL7A. Analyzed by Student’s t test. (e) HK-2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 1 h, and CEBPD in two pooled fractions per sample was assessed by qPCR, presented as a percent of total CEBPD from all fractions. Shading: pink denotes supernatant (Supt), green denotes 40S, 60S, and 80S fractions, and blue denotes polysomes. (f) Proposed mechanism of Arid5a function in AGN: Arid5a binds to 18S rRNA (40S ribosome subunit). Arid5a also binds to the 5S rRNA (60S), though interactions are likely weak or transient. Arid5a enhances translational efficiency of CEBPD and IL6 among other RNAs, cumulatively promoting pathology in AGN. *P < 0.05. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Consistent with a role for Arid5a in increasing translation of inflammatory mRNAs, CEBPD, CEBPB, and IL6 were enriched in actively translated polysome fractions polysomes upon IL-17 treatment, which was reduced in HK-2ΔARID5A cells (Fig. 6 e and Fig. S4, d and e). Nonetheless, even in unstimulated conditions CEBPD and CEBPB were found in polysomes, in agreement with their tonic baseline expression (Fig. 4 f). Collectively, these data suggest a model in which Arid5a is upregulated in RTECs during IL-17–driven renal inflammation; whereupon Arid5a exits the nucleus and interacts with the 40S ribosome to facilitate translation of key inflammatory TFs (e.g., C/EBPs). These TFs in turn activate inflammatory effectors that promote AGN (Fig. 6 f) (Bechara et al., 2021; Dey et al., 2024).

HK-2 cells are immortalized RTECs and thus represent a physiologically relevant cell type with respect to AGN (Li et al., 2021). However, they express quite low levels of Arid5a, which necessitated ectopic overexpression for these RIP-Seq studies. To evaluate whether similar activities of Arid5a are seen in an endogenous setting, we addressed Arid5a function in an IL-17–sensitive stromal cell line ST2 (Shen et al., 2005), where Arid5a was originally linked to the IL-17 signaling pathway (Amatya et al., 2018). As reported, IL-17 upregulated Arid5a mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 7 a and Fig. S5 a). Just as observed in HK-2 cells when Arid5a was overexpressed, IL-17 caused Arid5a to associate with rRNAs (assessed by formaldehyde crosslinking RIP-qPCR, fRIP) (Fig. 7 b). This interaction was specific and IL-17 dependent, because Arid5a did not bind to rRNAs in the absence of IL-17 stimulation, nor was there nonspecific binding in IgG control RIP samples. Polysome profiling similarly confirmed that endogenous Arid5a was located dominantly within the 40S ribosome fraction (Fig. 7 f). Also similar to HK-2 cells, IL-17 prompted nuclear export of Arid5a and increased its association with ribosomes (Fig. 7 g).

Arid5a binds rRNAs and facilitates protein synthesis in murine stromal cells. (a) Experimental design. Inset: ST2 cells were treated with murine IL-17 for 1, 3, or 6 h, and Arid5a and β-actin were assessed by immunoblotting, representative of two independent experiments. (b) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h and lysates were subjected to RIP with anti-Arid5a Abs or IgG controls. Enrichment of rRNAs corresponding to mouse 18S, 5S, 5.8S, and 28S were determined by qPCR, normalized to untreated IgG RIP controls. Data show mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal–Wallis test. Each symbol represents an individual experimental sample (18S n = 10; 5S, 5.8S, and 28S n = 6), pooled from two independent experiments. (c) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h and lysates were subjected to fRIP-Seq by Illumina with anti-Arid5a Abs. The plot shows differentially expressed mRNAs in IL-17–treated pulldowns compared to untreated controls (n = 3–4 independent replicates). NS, not significant. (d) GSEA pathway predictions of Arid5a-fRIP-Seq, comparing untreated controls and IL-17–treated samples. FDR < 0.25, minimum gene IDs in category = 15. (e) Intersection analysis comparing orthologs in Arid5a RIP-Seq from IL-17–treated ST2 and HK-2 cells (from ). Selected genes identified in the intersection dataset. (f) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h. Cytoplasmic lysates were separated by sucrose gradient fractionation. Arid5a and RPL7A were assessed in two pooled fractions per sample. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (g) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, stained with DAPI or Arid5a and RPL7A, and imaged by confocal microscopy. Arrows denote regions of co-association of Arid5a with RPL7A. Size bar = 10 µm. Quantitation of nuclear Arid5a is shown on the right. Each value represents the percentage of colocalized volume from an individual cell (n = 17–31). Analyzed by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Arid5a binds rRNAs and facilitates protein synthesis in murine stromal cells. (a) Experimental design. Inset: ST2 cells were treated with murine IL-17 for 1, 3, or 6 h, and Arid5a and β-actin were assessed by immunoblotting, representative of two independent experiments. (b) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h and lysates were subjected to RIP with anti-Arid5a Abs or IgG controls. Enrichment of rRNAs corresponding to mouse 18S, 5S, 5.8S, and 28S were determined by qPCR, normalized to untreated IgG RIP controls. Data show mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal–Wallis test. Each symbol represents an individual experimental sample (18S n = 10; 5S, 5.8S, and 28S n = 6), pooled from two independent experiments. (c) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h and lysates were subjected to fRIP-Seq by Illumina with anti-Arid5a Abs. The plot shows differentially expressed mRNAs in IL-17–treated pulldowns compared to untreated controls (n = 3–4 independent replicates). NS, not significant. (d) GSEA pathway predictions of Arid5a-fRIP-Seq, comparing untreated controls and IL-17–treated samples. FDR < 0.25, minimum gene IDs in category = 15. (e) Intersection analysis comparing orthologs in Arid5a RIP-Seq from IL-17–treated ST2 and HK-2 cells (from ). Selected genes identified in the intersection dataset. (f) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h. Cytoplasmic lysates were separated by sucrose gradient fractionation. Arid5a and RPL7A were assessed in two pooled fractions per sample. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (g) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h, stained with DAPI or Arid5a and RPL7A, and imaged by confocal microscopy. Arrows denote regions of co-association of Arid5a with RPL7A. Size bar = 10 µm. Quantitation of nuclear Arid5a is shown on the right. Each value represents the percentage of colocalized volume from an individual cell (n = 17–31). Analyzed by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Arid5a signaling in murine stromal (ST2) cells (associated with Fig. 7 ). (a) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h and expression of indicated mRNAs was assessed by qPCR, normalized to Gapdh. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Each symbol represents one replicate. (b) PCA showing sample heterogeneity. (c) Intersection analysis comparing orthologs in Arid5a RIP-Seq from HK-2 versus ST2 cells. ***P < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Arid5a signaling in murine stromal (ST2) cells (associated with Fig. 7 ). (a) ST2 cells were treated ± IL-17 for 3 h and expression of indicated mRNAs was assessed by qPCR, normalized to Gapdh. Mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Each symbol represents one replicate. (b) PCA showing sample heterogeneity. (c) Intersection analysis comparing orthologs in Arid5a RIP-Seq from HK-2 versus ST2 cells. ***P < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

In ST2 cells, Illumina RIP-Seq analyses confirmed that IL-17 promoted Arid5a interactions with a distinct and specific subset of RNA targets, which were in good agreement with results from HK-2 cells (Fig. S5 b). PCA confirmed robust statistical separation of Arid5a-bound RNAs based on (i) IL-17 stimulation status and (ii) IgG control pulldown. Among IL-17–induced Arid5a binding targets were Cebpd, Nfkbiz, and rRNA and ribosome processing pathway transcripts (Fig. 7 c). Furthermore, GSEA profiling showed enrichment of rRNA processing pathways cells (Fig. 7 d). In comparing the intersection between the HK-2 and ST2 RIP-Seq datasets, there was significant overlap between human RNAs associated with Arid5a compared to their mouse orthologs (Fig. 7 e), despite the differences between conditions (namely, endogenous versus overexpressed Arid5a, epithelial cells versus fibroblasts, human versus mouse cells) (Fig. 7 e, Fig. S5 c, and Table S1).

Collectively, these data reveal a conserved mechanism for Arid5a in directing protein translation through interactions with ribosomes/rRNA in response to IL-17, which ultimately drives deleterious inflammatory gene expression in autoimmune kidney disease.

Discussion

Inflammation-induced renal damage is potentiated by elevated inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that recruit immune cells to kidney, establishing a feed-forward circuit that leads to end-stage renal disease. Unchecked inflammation triggered by autoantibody deposition causes organ and vascular damage, e.g., in ANCA vasculitis, anti-GBM nephritis, and lupus (Cianciolo and Jennette, 2018; Jennette and Falk, 2014; Kurts et al., 2013). IL-17 and Type 17 cells are implicated in human GN and preclinical AGN models (Biswas, 2018; Hunemorder et al., 2015; Kurts et al., 2013). For example, ANCA-GN kidneys show IL-17 gene signatures (Velden et al., 2012) accompanied by elevated serum IL-17, IL-23, and Th17 cells that correlate with severity and relapse (Krajewska Wojciechowska et al., 2020; Martinez Valenzuela et al., 2019; Nogueira et al., 2010; Wilde et al., 2010). Tissue-resident memory Th17 cells are enriched in human GN and recognize commensal microbes associated with strong Th17 responses (Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans), rather than renal autoantigens (Krebs et al., 2020). Biologics targeting IL-17 thus far are not approved for GN, though tocilizumab, targeting IL-6 and thus Th17 cells indirectly, exhibited remission in a case study (Berti et al., 2015). Hence, understanding which pathways drive AGN may help inform clinical interventions.

While no experimental model perfectly mirrors human AGN, we made use of an autologous model of rapidly progressive nephritis (Du et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2007; Pisitkun et al., 2012) in which histopathology (glomerular crescent formation, mesangial and endocapillary hypercellularity, tubular atrophy, inflammation) and biomarkers of renal damage align well with human disease (Biswas, 2018; Krebs et al., 2017). In this and similar settings, IL-17RA and Act1 are required for pathogenesis (Pisitkun et al., 2012; Ramani et al., 2014; Riedel et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2012), and blockade of Th17 cell generation or IL-17 attenuates disease (Krebs et al., 2020; Ramani et al., 2014). IL-17 is produced by lymphocytes (in AGN, Th17, and γδ-T cells [Krebs et al., 2016; Krebs et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2012]), but generally signals in non-hematopoietic cell compartments. Although Arid5a can promote Th17 differentiation in a T cell–intrinsic manner (Masuda et al., 2013, 2016), we saw that Arid5a acts only in radioresistant cells in the AGN mouse model. This is consistent with the fact that the cells requiring IL-17RA are Cdh16+ RTECs (Li et al., 2019). In line with this, Arid5a was enhanced in RTECs in an IL-17/Act1-dependent manner, leading to disease hallmarks such as upregulation of renal IL-6 and inflammatory myeloid cell infiltration. Thus, there is good agreement between mice and humans regarding Arid5a expression and function in this condition.

IL-17 signals through multiple TFs, especially C/EBPs (Amatya et al., 2017; Balamurugan and Sterneck, 2013). C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are non-redundant for activation of many IL-17 target genes and are pivotal targets of Arid5a (Ruddy et al., 2004; Shen et al., 2006, 2009; Su et al., 2017). C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are intronless genes that are regulated transcriptionally but also posttranscriptionally and posttranslationally (Amatya et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Tsukada et al., 2011). We reported that C/EBPδ is prominently expressed in RTECs during AGN in an IL-17–dependent manner (Bechara et al., 2021) and is required for Thy1-induced renal inflammation, indicating a widespread role in kidney diseases (Takeji et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2022; Yamaguchi et al., 2015). However, mouse AGN models do not progress to end-stage renal fibrosis, which is the basis for organ failure in humans, and IL-17 signaling in mice is not required in a model of chemical-induced nephrotoxicity (Ramani et al., 2018b). Our new study shows that C/EBPδ is required for AGN pathogenesis but not chemical-induced fibrotic nephrotoxic injury (Dey et al., 2024). Therefore, C/EBPδ is a central and nonredundant IL-17–inducible TF underlying AGN, but its roles in kidney are clearly nuanced.

IL-17 exerts major impacts on posttranscriptional signaling (Bechara et al., 2023; Li et al., 2019). Act1 is critical for all known IL-17 functions, and functions as a scaffold, E3 ubiquitin ligase, and RBP, though which of these diverse activities specifically drive kidney inflammation is undefined (Draberova et al., 2020; Herjan et al., 2018; Pisitkun et al., 2012). The endoribonuclease Regnase-1 (Zc3h12a) is a feedback inhibitor of IL-17 signaling and Th17 cell differentiation in several autoimmune settings including AGN (Behrens et al., 2018, 2021; Garg et al., 2015; Jeltsch et al., 2014; Li et al., 2021; Monin et al., 2017). Arid5a counteracts the suppressive activities of Regnase-1 by competing for occupancy on the IL6 3′ UTR, but the extent to which this is a universal mechanism has not been systematically determined (Masuda et al., 2013). We confirmed that Arid5a binds to Regnase-1 (Zc3h12a) in ST2 cells (Amatya et al., 2018), whereas in HK-2 cells Arid5a bound more reproducibly to Regnase-3 (ZC3H12C), perhaps reflecting a cell-type-specific distinction. Hence, Arid5a is part of a network of RBP–RNA interactions that coordinate inflammation.

The best-characterized Arid5a effector functions binding and stabilizing mRNA (Amatya et al., 2018; Masuda et al., 2013, 2016; Zaman et al., 2016), though it also serves as a DNA-binding TF (Chalise et al., 2019). Our data indicate that Arid5a-dependent C/EBP expression contributes to its activity in AGN. Several observations led to a conclusion that the principle Arid5a-dependent contribution to increased C/EBP accumulation is at the level of translation. Despite modest reductions in the half-life of C/EBP-encoding mRNAs in the absence of Arid5a, total steady-state levels of these transcripts did not change and therefore could not account for increased C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ protein concentrations. CEBPB and CEBPD occupancy in large polysomes was concomitantly decreased in Arid5a-deficient cells, also indicative of Arid5a-facilitated translation. Unexpectedly, Arid5a-deficient RTECs (human and mouse) showed reduced global translation based on puromycin incorporation into nascent polypeptides. Given that IL-17 does not cause overall changes in cellular global protein synthesis, it is likely that many of Arid5a’s target proteins are undergoing tonic translation, supported by recent CLIP-Seq findings (von Ehr et al., 2024, Preprint). The specificity of Arid5a function in the IL-17 signaling pathway may come from the cytokine-induced nuclear export of Arid5a, documented here and elsewhere (Higa et al., 2018; von Ehr et al., 2024, Preprint). It is not surprising that Arid5a is multifunctional, as many RBPs (HuR and Act1, for example, in the IL-17 pathway) have both RNA stabilization and translation capabilities (Herjan et al., 2013, 2018; Nyati et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2011).

Most downstream IL-17–induced genes are expressed to a tonic degree at baseline, and thus IL-17–mediated gene upregulation is not usually a result of de novo transcription or opening of closed chromatin. Consistent with this, IL-17–regulated mRNAs such as the CEBP genes were present in polysomes even in the absence of Arid5a. RIP-Seq revealed that an unexpected class of RNAs that bind to Arid5a after IL-17 stimulation encoded RNA processing and translational machinery, notably rRNAs (18S, 5S). Importantly, total concentrations of rRNA and other translation-associated RNAs were not upregulated upon IL-17 signaling, so this enhanced association is not simply due to an increased pool of targets.

As noted, the subcellular localization of Arid5a is dynamic in response to inflammatory stimuli (Higa et al., 2018). In keeping with this, we observed that Arid5a was nuclear in the absence of stimulation, but cytoplasmic Arid5a levels increased after IL-17 treatment. Importantly, nuclear export occurred even when Arid5a was ectopically overexpressed, indicating that specific IL-17 signals actively drive this process. Once in the cytoplasm, Arid5a associated with ribosomes, mainly the 40S subunit/18S rRNA. In addition, IL-17 caused Arid5a to associate with 60S rRNAs, though Arid5a was not in 60S or 80S ribosome polysome fractions. These findings collectively suggest a model in which Arid5a binds stably to the 40S ribosome and interacts transiently and dynamically with 60S during translation initiation, likely dissociating once a stable ribosome is formed. This concept has precedent in a recently described translational facilitator, METTL16, which binds rRNAs and enhances RNA translational efficiency (Su et al., 2022). We did not perform studies to define the Arid5a target site, but previous reports have shown Arid5a preferentially interacts with an adenylate-uridylate–rich consensus sequence (Masuda et al., 2013; von Ehr et al., 2024, Preprint).

The success of Th17 targeting in psoriasis inspired efforts to determine the contribution of IL-17 to other clinical conditions (Gaffen et al., 2014; McInnes and Schett, 2007). A limitation of protein-based biologics is that they indiscriminately block signals activated by the targeted cytokine, not to mention high costs. Therefore, selectively blocking IL-17 signaling pathways with small-molecule inhibitors might be more selective and less prone to adverse side effects. Some evidence indicates that Arid5a could be an ideal target in this regard, as it is required for EAE and AGN pathogenesis yet is dispensable for IL-17–dependent immunity to opportunistic C. albicans fungal infections (Masuda et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2022). Hence, somewhat surprisingly, the signaling pathways required for host defense are not necessarily those that are essential for autoimmune inflammation. Arid5a was reported to be blocked by the antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine, though how this occurs is not clear (Masuda and Kishimoto, 2018). Aptamers or antisense oligonucleotides based on Act1 or Regnase-1 are effective in preclinical models, and therefore defining Arid5a RNA targets may illuminate avenues by which analogous inhibitors could be developed (Chen et al., 2022; Herjan et al., 2018; Tse et al., 2022). Ultimately, these findings advance our understanding of cytokine signaling nodes controlling inflammation and their significance in renal autoimmunity.

Materials and methods

Study design

The objective of this study was to determine the role and mechanistic basis of Arid5a in autoimmune kidney disease. To that end, we used human renal biopsies, public databases of kidney disease patients, cell culture studies, and a mouse model of AGN. Sample sizes were determined by power analyses from pilot studies or previously published data. No data were excluded. Mice were assigned randomly to experimental cohorts and both sexes were used. Experiments were done two to five independent times. Investigators were not blinded to groups except for histology assessments. Endpoints were selected based on experience from prior studies.

Mice

Arid5a−/− were described (Taylor et al., 2022) and backcrossed to the reference strain once (available at The Jackson Laboratory). Act1−/− mice were from National Institutes of Health (NIH) and backcrossed twice to the reference strain. B6.SJL-Ptprc (B6 CD45.1) mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. WT mice were obtained from breeding, Taconic Biosciences, or The Jackson Laboratory and cohoused with experimental cohorts for at least 2 wk in specific pathogen–free conditions. All mice were age- and sex-matched on the C57BL/6 background. Experiments complied with state and federal guidelines. Protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Public human datasets

The European Renal cDNA Biobank database was interrogated for expression of human ARID5A and IL17 mRNA in the following populations (both sexes): IgA nephropathy (n = 27); focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (n = 18); membranous nephropathy (n = 21); ANCA (n = 22); tumor nephrectomy (n = 5); and healthy control (n = 21). The Human Cell Atlas and Human Nephrogenesis Atlas datasets (Lindstrom et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2019) were evaluated for ARID5A and ATP1A1.

GN and renal fibrosis model

AGN was performed as described (Bechara et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). Briefly, rabbit IgG (0.1 mg/ml) in complete Freund’s adjuvant (2.5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected i.p. on day −3. On day 0, mice were immunized i.v. with heat-inactivated rabbit anti-mouse GBM serum (Lampire Biological Laboratories). On day 7 or 14, BUN was measured by ELISA (Bioo Scientific) and creatinine by QuantiChrom Creatinine Assay Kit (DICT-500; BioAssay Systems). H&E staining on 5–6-µm slices was visualized on an EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Slides were scored by investigators blinded to sample identity. Renal fibrosis was induced by i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg AA1 (Sigma-Aldrich) or PBS (Jawale et al., 2020). On day 6, BUN was measured by ELISA (Bioo Scientific).

Radiation chimeras

Mice were given sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim in drinking water for 10 d and then lethally irradiated (900 rad). 24 h later, 5 × 106 femoral BM cells were injected i.v. into recipients. After 6–8 wk, engraftment was verified by flow cytometry for congenic markers (CD45.1 and CD45.2). Mice with >90% engraftment were used for AGN analysis.

Cell culture and stimulation

HK-2 cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) with antibiotics and 10% FBS. If noted, HK-2 cells were transfected with a Flag-(human) ARID5A-encoding plasmid using FuGene HD (Promega). ST2 cells were cultured in α-MEM (Sigma-Aldrich) with L-glutamine, antibiotics, and 10% FBS. Recombinant mouse or human IL-17 (PeproTech) was used at 100–200 ng/ml. HK-2ΔARID5A cells were made by Synthego by electroporation with Cas9 and an Arid5a-specific single guide RNA (5′-AACGUGUACGACGAGCUGGG-3′). Clones were obtained by limiting dilution of a knockout pool, verified by Sanger sequencing and PCR (forward: 5′-AGTCCATGGCCCTAGGAGAG-3′; reverse: 5′-GCTTCAGCTCCCTCAGTGAG-3′). Sequencing results were analyzed using the Inference of CRISPR Edits tool (https://ice.synthego.com/#/). Cell growth was monitored on an EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

To obtain primary RTECs, kidney was digested by 1% of collagenase type V (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min and filtered in a 40-µm cell strainer (Falcon). Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) with 25 mM HEPES, 5% FBS, antibiotics, and hormone mixture (0.25 µg/ml EGF, 5 µg/ml insulin, 0.169 µg/ml triiodothyronine, 5 µg/ml transferrin, 1.73 ng/ml sodium selenite, 18 ng/ml hydrocortisone; Sigma-Aldrich). Medium was changed on day 2 and used for experiments on days 4–5.

Mouse primary fibroblasts were created from WT or Arid5a−/− ears by digestion in collagenase I (15 mg/ml; Millipore) and culture in DMEM (Gibco) with antibiotics, 5–15% FBS, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. Mouse primary fibroblasts were used on passages 3–5. For the scratch assay, primary fibroblasts were cultured in 15% FBS medium until confluent. A straight cell scratch was made using a sterile 200-µl tip. Scratch recovery was monitored on an EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RIP and RIP-Seq

RIP was performed as described (Amatya et al., 2018; Bechara et al., 2021). Cell extracts were isolated with RIP buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.0], 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, and 1 mM DTT), RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Lysates were precleared with protein A agarose (Roche) or protein G–conjugated magnetic Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG (F3165; Sigma-Aldrich) or IgG controls. Beads were washed with NT2 buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40) and digested with DNase I (Roche) and protease K (Sigma-Aldrich). Where indicated, samples were pre-incubated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, followed by incubation with 125 mM glycine for 5 min. After IP, cross-links were reversed in buffer (5 M NaCl, DNase I) at 37°C for 30 min followed by protease K (Roche) at 65°C for 1 h (Niranjanakumari et al., 2002; Selth et al., 2009).

RIP-Seq libraries of HK-2 cells (transfected with Flag-Arid5a) were generated using the SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA kit (Takara Biosciences), sequenced on a NextSeq 500 and analyzed by the University of Pittsburgh Computational Immunogenomics Core. After initial quality control and adapter trimming, the raw sequence data was aligned to hg38 (Gencode) using STAR, and Arid5a-enriched RNAs were quantified using RSEM software. After quantification, differentially enriched genes (pairwise analyses across the comparisons of interest) were identified using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014; Uren et al., 2012) Significantly differentially enriched genes (compared to IgG) were defined using a false discovery rate (FDR) (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P value) threshold of <0.05. GSEAs were performed using the WebGestalt tool to identify enrichment of genes in specific pathways (Liao et al., 2019).

For RIP-Seq in ST2 cells, the library was generated using the SMART-Seq Stranded kit (Takara) and sequenced on a NextSeq 2000 (Illumina). Differential expression analysis and pathway analysis were performed using the same methods and tools as above, except using g mm10 (Gencode) as a reference genome for alignment and FDR threshold of <0.25. We identified genes that were significantly differentially expressed in common between the murine and human datasets by using Orthogene R package (Schilder and Skene, 2022). Data are available at GEO: GSE269728 and GSE269729.

qPCR

RNA was isolated with RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized by iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). Real-time qPCR was performed with the SYBR Green FastMix ROX (Quanta Biosciences) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Primers were from QuantiTect Primer Assays (Qiagen) unless noted (Table S2). Roadblock-qPCR was performed as described (Watson et al., 2020). Briefly, HK-2 cells were primed with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 3 h and then stimulated with 400 µM 4-thiouridine (4sU; Sigma-Aldrich) ± IL-17 (200 ng/ml). After 65°C denaturation for 5 min, RNA was labeled by N-ethylmaleimide. cDNA was synthesized by SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with Oligo d(T).

Immunoblotting and IP

Western blotting and IPs were performed as described (Amatya et al., 2018; Bechara et al., 2021). Immunoblotting Abs (Table S3): IκBξ (9244 or 93726S; Cell Signaling), Arid5a (P18112; Invitrogen), C/EBPβ (3082; Cell Signaling or sc7962; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), C/EBPδ (2318; Cell Signaling or sc365546; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), β-actin (ab49900; Abcam), Puromycin (12D10; Millipore), RPL7A (15340-1-AP; Proteintech), eIF4G (2469S; Cell Signaling), eIF4E (9742S; Cell Signaling), FLAG M2 (F3165; Sigma-Aldrich), YY1 (sc1703; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and α-tubulin (ab40742; Abcam). Protein A and B Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were used for IP. Blots were visualized with a FluorChem E imager (ProteinSimple). Densitometry was performed by ImageJ.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Table S4 describes conditions for microscopic analyses. Frozen sections of murine kidney (8 μm) were fixed in 100% methanol and blocked with 5% goat serum (Life Technologies) in Triton X-100. Slides were incubated with anti-Arid5a (P18112; Invitrogen) followed by goat anti-mouse AF488 (A32723; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Slides were visualized on an EVOS FL system (Life Technologies). For H&E staining, 4-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and percent of abnormal glomeruli determined by experts blinded to sample identity.

HK-2 or ST2 cells were plated on glass slides. HK-2 cells were transfected with FLAG-Arid5a. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Cells were blocked in 5% goat serum with 0.3% Triton X-100 with 1% BSA and stained with anti-RPL7A (15340-1-AP; Proteintech), anti-Calnexin (ab22595; Abcam), anti-Arid5a (P18112; Invitrogen), or anti-FLAG (F3165; Sigma-Aldrich), then stained with fluorescence-conjugated secondary Abs and mounted using Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Cells were visualized on a Nikon A1 confocal microscope for image acquisition by NIS viewer and quantified by NIS-Elements (Nikon).

Flow cytometry

Kidneys were harvested following PBS perfusion. Tissue was digested with collagenase IV (1 mg/ml) in HBSS. Antibodies: anti-CD45 (30-F11; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-CD3 (BM10-37; BD Biosciences), anti-CD4 (RM4-5; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-CD8 (53-6.7; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-CD11b (M1/70; BioLegend), anti-CD11c (HL3; BD Biosciences), anti-Ly6G (1A8; BD Biosciences), anti-Ly6C (HK1.4; eBiosciences), anti-CD133 (13A4; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-F4/80 (BM8; eBioscience), anti-MHCII (M5/114.15.2; eBioscience), anti-Ki-67 (16A8; BioLegend). BrDU flow kit (552598; BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded using Ghost Dye (eBioscience). Data were acquired with an LSR Fortessa and analyzed by FlowJo (TreeStar).

Puromycin pulse labeling