The interplay between ribosomal protein (RP) composition and mitochondrial function is essential for energy homeostasis. Balanced RP production optimizes protein synthesis while minimizing energy costs, but its impact on mitochondrial functionality remains unclear. Here, we investigated haploinsufficiency for RP genes (rps-10, rpl-5, rpl-33, and rps-23) in Caenorhabditis elegans and corresponding reductions in human lymphoblast cells. Significant mitochondrial morphological differences, upregulation of glutathione transferases, and SKN-1–dependent oxidative stress resistance were observed across mutants. Loss of a single rps-10 copy reduced mitochondrial activity, energy levels, and oxygen consumption, mirrored by similar reductions in mitochondrial activity and energy levels in lymphoblast cells with 50% lower RPS10 transcripts. Both systems exhibited altered translation efficiency (TE) of mitochondrial electron transport chain components, suggesting a conserved mechanism to adjust mitochondrial protein synthesis under ribosomal stress. Finally, mitochondrial membrane and cytosolic RPs showed significant RNA and TE covariation in lymphoblastoid cells, highlighting the interplay between protein synthesis machinery and mitochondrial energy production.

Introduction

The coordinated expression of ∼79 ribosomal proteins (RPs) is essential for cellular health and development. In humans, the haploinsufficiency or point mutations of RP genes leads to a range of ribosomopathies (Paolini et al., 2017), including Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA) (Ulirsch et al., 2018), and has been linked to an increased susceptibility to certain cancers, such as myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia (Vlachos et al., 2012; Goudarzi and Lindström, 2016). With its hallmark features of hematological dysfunction and an increased risk of malignancies, DBA exemplifies the systemic consequences of RP deficits (Lipton, 2006; Ellis and Lipton, 2008).

DBA and other ribosomopathies are rare genetic disorders. However, hemizygous losses of RP genes are frequently observed (∼40%) in tumors (Ferreira et al., 2014; Ajore et al., 2017) and impact cellular proliferation and oncogenesis (Amsterdam et al., 2004; Kulkarni et al., 2017; Guimaraes and Zavolan, 2016). Specifically, RP mutations are associated with higher mutational load in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) patients (Sulima et al., 2019; Girardi et al., 2017). Hemizygous deletion of RPL5 occurs in 11–34% of multiple tumor types, and reduced expression of this gene is correlated with poor survival in glioblastoma and breast cancer (Fancello et al., 2017; De Keersmaecker et al., 2013). Conversely, overexpression of RPL15 and RPL28 leads to increased metastatic growth (Ebright et al., 2020; Labriet et al., 2019). The phenotypes associated with these genetic disruptions allude to the roles that these proteins play beyond protein synthesis.

Considering the significant energy demands of ribosome biogenesis (Warner, 1990), mitochondrial function and ribosome production are interconnected to ensure optimal cellular energy equilibrium. A reciprocal connection between ribosomal and mitochondrial DNA copy number is observed across individuals (Gibbons et al., 2014). Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction leads to retrograde signaling that alters the accumulation of extra chromosomal ribosomal DNA circles (Borghouts et al., 2004). One potential mechanistic link between these processes is RNAse MRP, which is involved both in the processing of ribosomal RNA in the nucleolus, and in priming DNA replication in mitochondria (Yuan et al., 1989; Topper and Clayton, 1990; Topper et al., 1992; Stohl and Clayton, 1992; Lee et al., 1996).

Other observations supporting the connection between ribosome biogenesis and mitochondrial function include: (1) translation of mitochondrial transcripts are reduced and mitochondrial structure and oxygen consumption are altered in response to the deletion of ribosome biogenesis factor, Bud23, in mouse cardiomyocytes (Baxter et al., 2020). (2) Yeast Asc1 (RACK1 ortholog) mutants, exhibit reduced translation of cytosolic and mitochondrial ribosome transcripts and lower fitness in a non-fermentable carbon source suggesting decreased mitochondrial activity (Thompson et al., 2016). (3) The inhibition of ribosomal RNA synthesis through the depletion of the RNA polymerase I component, RPOA-2, in C. elegans results in a significant decrease in mitochondrial RPs without affecting their transcript levels (Zhao et al., 2023; Freeman et al., 2023). These observations suggest that altering ribosome biogenesis could alter mitochondrial components or function across different species. Reciprocal to the evidence provided, the biogenesis of cytosolic ribosomes also requires functional mitochondria. For instance, Rli1p, a protein carrying Fe/S clusters and thus requiring mitochondrial protein machinery, is associated with ribosomes and Hcr1p, which is involved in 20S pre-rRNA processing and translation initiation (Kispal et al., 2005).

Interestingly, a notable parallel has been observed between DBA and Pearson syndrome, which results from mitochondrial DNA losses (Fontenay et al., 2006). Their symptoms are strikingly similar; in one instance, ∼5% of patients initially diagnosed with DBA were found to have significant mitochondrial DNA loss, leading to their reclassification as Pearson syndrome patients (Gagne et al., 2014). Similarly, expression analysis within a large family carrying a single-copy SNP variant in RPL11 (Narla et al., 2016; Carlston et al., 2017) suggested altered mitochondrial expression, indicating that coordination between mitochondria and ribosomes may be disrupted upon single-copy loss of RP genes (Panici et al., 2021).

Despite the known links between ribosome biogenesis and mitochondria, the ways in which mitochondrial function and oxidative stress relate to RP haploinsufficiency have yet to be explored. Mitochondria not only produce ATP but also play an important role in regulating oxidative stress through reactive oxygen (ROS) production. Disruptions in mitochondrial function can lead to oxidative stress (Jones, 2006).

In C. elegans, the transcription factor SKN-1 (homologous to mammalian NRF2) regulates the oxidative stress response by activating detoxification genes such as gluthatione S-transferases (gst) (Settivari et al., 2013; Blackwell et al., 2015). Changes in RP level may affect SKN-1 activity and oxidative stress pathways, but this connection hasn’t been thoroughly investigated. Previous studies hint at a connection between ribosome biogenesis and mitochondrial function in maintaining cellular homeostasis. However, the specific effects of RP haploinsufficiency on mitochondrial morphology and oxidative stress were not well characterized.

Here, we investigate the effects of single-copy loss for four RP genes (rps-10, rpl-5, rpl-33, and rps-23) in C. elegans, along with corresponding reductions in human lymphoblast cells. Our investigations revealed significant mitochondrial morphological alterations with increased oxidative stress resistance across these RP haploinsufficient mutants and a conserved mechanism that coordinates the translation of mitochondrial components in response to compromised ribosomal machinery. Notably, a reduction in the cytoplasmically assembled RPS-10 in C. elegans (rps-10(0)/+ mutant) exhibited altered mitochondrial function and reduced cellular energy—a phenomenon mirrored by a 50% reduction in RPS10 abundance in human cells. These observations are further supported by significant expression covariation between mitochondrial membrane components and RPs across lymphoblastoid cells derived from a diverse group of individuals, suggesting an adaptive conserved mechanism of mitochondrial function in response to ribosomal expression alterations.

Results

Developmental and physiological consequences of ribosomal protein gene haploinsufficiency in C. elegans

We sought to determine the impact of haploinsufficiency of RP genes in C. elegans and focused on the single-copy losses of two large subunit RPs, rpl-5 and rpl-33, along with two small subunit RPs, rps-10 and rps-23 (Cenik et al., 2019). We prioritized these four RP genes due to their involvement in human ribosomopathies, with rpl-5, rpl-33, and rps-10 relating to DBA (Farrar et al., 2008), and rps-23 relating to microcephaly and intellectual disability without the blood phenotypes (Paolini et al., 2017). Moreover, the protein products of these RP genes are incorporated into nascent ribosomes at different stages (nucleolar, nuclear, and cytoplasmic) (de la Cruz et al., 2015). We observed developmental delays across these RP haploinsufficient mutants compared with wild-type counterparts (Fig. 1, A and B; and Fig. S1 A). Protein levels were evaluated using semiquantitative proteomics against stage-matched controls, revealing reductions of ∼50% for RPL-33 and RPS-23, 25% for RPL-5, and 10% for RPS-10 (Fig. 1 C and Table S1). The developmental delays observed in haploinsufficient strains, as compared with their time-matched controls, were found to generally correspond with the degree of protein reduction resulting from the loss of a single copy (Fig. 1 C). These findings suggest a correlation between the extent of protein level reduction and the timing of developmental processes.

Ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency results in developmental delays and variable body size without affecting lifespan in C. elegans. (A) The development of single copy large subunit ribosomal protein (RP) mutants alongside their wild-type counterparts after 96 h of incubation from embryo at 16°C. Images show ∼1 day of growth delay (left) and differences in vulval development (right), with a scale bar of 50 µm. Differential interference contrast images were taken with a 20× objective. (B) The developmental stage of animals after 72 and 96 h of incubation from embryo at 16°C were determined and plotted, with a stacked bar chart indicating the relative proportion of larvae at each stage. (C) Log2 fold-change estimates of ribosomal protein levels in haploinsufficient RP mutants compared to stage-matched control animals are shown. Relative protein amounts were predicted by Differential Expression Proteomics (DEP package, R) based on three replicates of semi-quantitative proteomics analysis. (D) Body area measurements of stage-matched animals (at late L4 stage), normalized to the median body area of each wild type/balancer group are shown. Differences in the average normalized body area of mutant and control animals were determined using a two-tailed Welch’s two-sample t test. The central line represents the median and the bars represent interquartile distribution. (E) Brood size of each haploinsufficient RP mutant, normalized to the median of their respective wild-type controls is shown. Each dot represents the number of progeny per individual animal. Differences in the mean normalized brood size of each mutant, compared to its respective control, were analyzed using an independent two-tailed Student’s t test. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (F) Lifespan of small subunit RP mutants (top) and large subunit RP mutants (bottom) alongside their respective wild-type controls are shown. Lifespan data are presented in a survival plot, analyzed using the Log-rank test and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Superscript numbers denote the specific wild type balancer chromosomes and are used to compare between an RP mutant and the wild-type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1. All experiments were performed in at least three biological replicates, and the animals were grown at 16°C. In panels C–F, RP mutants are color-coded for clarity: rpl-33(0)/+3 in green, rpl-5(0)/+3 in orange, rps-10(0)/+1 in blue, and rps-23(0)/+2 in red. The “n=” on the graphs indicates the total number of animals analyzed.

Ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency results in developmental delays and variable body size without affecting lifespan in C. elegans. (A) The development of single copy large subunit ribosomal protein (RP) mutants alongside their wild-type counterparts after 96 h of incubation from embryo at 16°C. Images show ∼1 day of growth delay (left) and differences in vulval development (right), with a scale bar of 50 µm. Differential interference contrast images were taken with a 20× objective. (B) The developmental stage of animals after 72 and 96 h of incubation from embryo at 16°C were determined and plotted, with a stacked bar chart indicating the relative proportion of larvae at each stage. (C) Log2 fold-change estimates of ribosomal protein levels in haploinsufficient RP mutants compared to stage-matched control animals are shown. Relative protein amounts were predicted by Differential Expression Proteomics (DEP package, R) based on three replicates of semi-quantitative proteomics analysis. (D) Body area measurements of stage-matched animals (at late L4 stage), normalized to the median body area of each wild type/balancer group are shown. Differences in the average normalized body area of mutant and control animals were determined using a two-tailed Welch’s two-sample t test. The central line represents the median and the bars represent interquartile distribution. (E) Brood size of each haploinsufficient RP mutant, normalized to the median of their respective wild-type controls is shown. Each dot represents the number of progeny per individual animal. Differences in the mean normalized brood size of each mutant, compared to its respective control, were analyzed using an independent two-tailed Student’s t test. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (F) Lifespan of small subunit RP mutants (top) and large subunit RP mutants (bottom) alongside their respective wild-type controls are shown. Lifespan data are presented in a survival plot, analyzed using the Log-rank test and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Superscript numbers denote the specific wild type balancer chromosomes and are used to compare between an RP mutant and the wild-type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1. All experiments were performed in at least three biological replicates, and the animals were grown at 16°C. In panels C–F, RP mutants are color-coded for clarity: rpl-33(0)/+3 in green, rpl-5(0)/+3 in orange, rps-10(0)/+1 in blue, and rps-23(0)/+2 in red. The “n=” on the graphs indicates the total number of animals analyzed.

Ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency results in developmental delays and reduced brood size without affecting lifespan in C. elegans. (A) Development of small subunit RP haploinsufficient mutants and their respective wild-type counterparts are shown after 96 h of incubation from embryo at 16°C. Images depict a delay in growth and vulval development. Images taken with differential interference contrast, using a 20× objective. Scale bar represents 50 µm. (B) The brood size of RP mutants and their respective controls were counted and plotted with respect to time. Each line represents a single animal. (C) The lifespan of small subunit RP mutants (top) and large subunit mutants (bottom) were plotted along with their respective controls in the presence of FuDR (5-fluorodeoxyuridine). The y-axis represents percent survival and “n” represents the total number of animals. All experiments were done in three biological replicates with animals grown at 16°C. Statistical analysis was performed using Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction. Superscript numbers denote the specific balancers compared between an RP mutant and its wild type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1, +4 = nT1. (D) L4 worms were pulse-labeled with puromycin for 4 h. After labeling, equal amounts of protein were loaded for puromycin and actin Western blots, and puromycin levels were quantified and normalized to actin. Representative western blots for puromycin and actin are shown on the left. In the right-side plot, the y-axis represents actin-normalized puromycin intensity, with each point indicating a biological replicate. The median is marked by a horizontal line, and standard error is shown as a vertical line. For comparisons, each RP haploinsufficient sample was compared to its respective wild-type control using a one-tailed Student’s t test. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. All P values were >0.5, indicating that overall translation was not significantly reduced in stage-matched RP haploinsufficient animals. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1 D.

Ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency results in developmental delays and reduced brood size without affecting lifespan in C. elegans. (A) Development of small subunit RP haploinsufficient mutants and their respective wild-type counterparts are shown after 96 h of incubation from embryo at 16°C. Images depict a delay in growth and vulval development. Images taken with differential interference contrast, using a 20× objective. Scale bar represents 50 µm. (B) The brood size of RP mutants and their respective controls were counted and plotted with respect to time. Each line represents a single animal. (C) The lifespan of small subunit RP mutants (top) and large subunit mutants (bottom) were plotted along with their respective controls in the presence of FuDR (5-fluorodeoxyuridine). The y-axis represents percent survival and “n” represents the total number of animals. All experiments were done in three biological replicates with animals grown at 16°C. Statistical analysis was performed using Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction. Superscript numbers denote the specific balancers compared between an RP mutant and its wild type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1, +4 = nT1. (D) L4 worms were pulse-labeled with puromycin for 4 h. After labeling, equal amounts of protein were loaded for puromycin and actin Western blots, and puromycin levels were quantified and normalized to actin. Representative western blots for puromycin and actin are shown on the left. In the right-side plot, the y-axis represents actin-normalized puromycin intensity, with each point indicating a biological replicate. The median is marked by a horizontal line, and standard error is shown as a vertical line. For comparisons, each RP haploinsufficient sample was compared to its respective wild-type control using a one-tailed Student’s t test. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. All P values were >0.5, indicating that overall translation was not significantly reduced in stage-matched RP haploinsufficient animals. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1 D.

Similar to previous reports of reduced body size in RP mutants in other species (Marygold et al., 2007; Oliver et al., 2004), our examination revealed that, when given sufficient time to reach the same developmental stage, C. elegans RP haploinsufficient mutants were slightly smaller in body size than wild-type controls with one exception (Fig. 1 D). Specifically, we observed that rps-10(0)/+ animals were slightly larger in body size compared with their stage-matched controls (Fig. 1 D, P = 0.02, independent Student’s t test). The increased body size could be associated with increased cell volume, altered cytoskeletal dynamics, or metabolism due to changes in signaling pathways such as TGF-β, MAPK, or cGMP (Hirose et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 2005). These results are also reminiscent of the larger wing sizes and wing discs observed in Drosophila following the single copy loss of RpL38 and RpL5 (Marygold et al., 2005). However, why single copy loss of certain RP genes leads to increased organ or body growth remains unclear.

We further conducted fecundity assays to assess impacts on reproduction. Except for rpl-5(0)/+ animals, which exhibited a significant reduction in progeny size (∼25% reduction; P = 0.03, independent Student’s t test), the progeny sizes of all other RP haploinsufficient mutants were similar to those of the controls (Fig. 1 E). The onset of peak fertility was delayed in all mutants except for rps-10(0)/+ animals (Fig. S1 B). Additionally, RP mutants remained fertile for extended periods, thereby compensating for the overall progeny size, except for rpl-5(0)/+ mutants. Reduced fertility was observed in Drosophila minute mutants, characterized by the lack of a single copy of an RP gene (Marygold et al., 2007). The observation of similar brood sizes in the majority of RP strains in C. elegans suggests the involvement of compensatory mechanisms within the germline.

Finally, we investigated lifespan in C. elegans RP mutants. Our lifespan analysis did not reveal significant differences for the majority of RP haploinsufficient mutants compared with wild-type controls, regardless of treatment with the egg-laying inhibitor fluorodeoxyuridine (FuDR). The only exception was rps-23(0)/+ mutants that displayed a modest but significant extension of lifespan only in the absence of FuDR (Fig. 1 F and Fig. S1 C, P = 0.007 for rps-23(0)/+ mutants, Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction). Reduced protein translation or the knockdown of RP genes is typically linked to increased lifespan (Syntichaki et al., 2007; Steffen et al., 2012; Rogers et al., 2011; Chiocchetti et al., 2007; Curran and Ruvkun, 2007; Tiku et al., 2017). However, our results suggest that haploinsufficiency for single RP genes negate the typical lifespan extension benefits associated with decreased protein synthesis due to imbalances in RP expression and the associated stress. To determine whether overall translation levels were reduced in response to RP haploinsufficiency, we quantified puromycin incorporation in stage-matched animals over a limited time period. Our results suggest that haploinsufficiency for single RP genes does not result in a significant reduction in overall translation when compared to stage-matched respective controls (Fig. S1 D, P value >0.05, one-tailed Student’s t test). Taken together, our phenotypic characterization of the haploinsufficiency of RP genes in C. elegans reveals a range of developmental and physiological consequences that broadly mimic those observed in other model organisms such as Drosophila and mice (Marygold et al., 2007; Oliver et al., 2004).

Adaptive cellular responses to ribosomal protein loss highlights SKN-1–dependent enhanced oxidative stress resistance

To understand the cellular mechanisms triggered by single copy losses of RP genes in C. elegans, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on stage-matched mutant and control animals at the L4 stage (Table S2). This analysis, which included stage-matched controls to mitigate any developmental delay effects, revealed a uniform gene expression response across all mutants. This response was characterized by overexpression of ribosomal machinery, glutathione transferase activity, and genes involved in innate immunity and stress responses, indicating a systemic adaptation to RP loss (Fig. 2 A, top, significantly enriched gene ontology [GO] categories provided in Table S3). Conversely, genes related to mitochondrial activity, fatty acid biosynthesis, cell polarity, and amino acid metabolism were significantly underexpressed (Fig. 2 A, bottom, Table S3), suggesting a reprogramming of cellular metabolism in response to RP haploinsufficiency.

Adaptive cellular responses to ribosomal protein loss highlights SKN-1 dependent enhanced oxidative stress resistance. (A) Investigation of significantly differentially expressed genes at the RNA level across all haploinsufficient RP mutants, with a focus on significant gene ontology (GO) enrichments are shown. Log2 fold-change gene expression estimates of representative GO categories that were enriched for overexpression (top) and underexpression (bottom) were plotted. All significantly enriched GO categories are provided in Table S3. The y-axis displays predicted RNA-seq log2 fold change estimate distribution for each GO category as predicted by edgeR. GO categories are annotated on the side, where “N” denotes the number of differentially expressed genes within a category, and “X” represents the total number of genes in that category. Each dot signifies an individual gene identified as underexpressed or overexpressed, with their distribution across the categories visualized through violin plots. (B) RNA expression log2 fold-change estimates of glutathione transferase genes annotated in the C. elegans genome across all mutants compared with their controls. (C) An acute time course of oxidative stress survival for large subunit RP mutants (first plot, rpl-5(0)/+ and rpl-33(0)/+) and small subunit RP mutants (second plot, rps-23(0)/+ and rps-10(0)/+), alongside wild-type control strains and daf-2(e13270) mutants serving as positive controls. All RP mutants showed significantly more resistance to acute oxidative stress (P < 0.001) compared with wild-type controls. rpl-5(0)/+; skn-1(zj15) double mutant animals were significantly less resistant to oxidative stress compared with rpl-5(0)/mutants (P = 0.016, third plot). Conversely, rpl-5(0)/+; daf-16(mu86) animals displayed similar responses to oxidative stress as rpl-5(0)/+ animals (P = 0.51, fourth plot). The “n=” on the graphs indicates the total number of animals analyzed. “n” indicates the total number of animals used in the study, and all experiments were performed using three biological replicates and all animals were grown at 16°C. rpl-33(0)/+3 in green, rpl-5(0)/+3 in orange, rps-10(0)/+1 in blue, and rps-23(0)/+2 in red. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1. For statistical analysis of oxidative stress resistance, Log-rank analysis with Bonferroni correction was performed for multiple comparisons. (D) Log2 fold-change estimates of SKN-1 targets in all RP mutants were plotted. SKN-1 targets were identified from differentially expressed genes upon the constitutive activation of SKN-1 (Nhan et al., 2019).

Adaptive cellular responses to ribosomal protein loss highlights SKN-1 dependent enhanced oxidative stress resistance. (A) Investigation of significantly differentially expressed genes at the RNA level across all haploinsufficient RP mutants, with a focus on significant gene ontology (GO) enrichments are shown. Log2 fold-change gene expression estimates of representative GO categories that were enriched for overexpression (top) and underexpression (bottom) were plotted. All significantly enriched GO categories are provided in Table S3. The y-axis displays predicted RNA-seq log2 fold change estimate distribution for each GO category as predicted by edgeR. GO categories are annotated on the side, where “N” denotes the number of differentially expressed genes within a category, and “X” represents the total number of genes in that category. Each dot signifies an individual gene identified as underexpressed or overexpressed, with their distribution across the categories visualized through violin plots. (B) RNA expression log2 fold-change estimates of glutathione transferase genes annotated in the C. elegans genome across all mutants compared with their controls. (C) An acute time course of oxidative stress survival for large subunit RP mutants (first plot, rpl-5(0)/+ and rpl-33(0)/+) and small subunit RP mutants (second plot, rps-23(0)/+ and rps-10(0)/+), alongside wild-type control strains and daf-2(e13270) mutants serving as positive controls. All RP mutants showed significantly more resistance to acute oxidative stress (P < 0.001) compared with wild-type controls. rpl-5(0)/+; skn-1(zj15) double mutant animals were significantly less resistant to oxidative stress compared with rpl-5(0)/mutants (P = 0.016, third plot). Conversely, rpl-5(0)/+; daf-16(mu86) animals displayed similar responses to oxidative stress as rpl-5(0)/+ animals (P = 0.51, fourth plot). The “n=” on the graphs indicates the total number of animals analyzed. “n” indicates the total number of animals used in the study, and all experiments were performed using three biological replicates and all animals were grown at 16°C. rpl-33(0)/+3 in green, rpl-5(0)/+3 in orange, rps-10(0)/+1 in blue, and rps-23(0)/+2 in red. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1. For statistical analysis of oxidative stress resistance, Log-rank analysis with Bonferroni correction was performed for multiple comparisons. (D) Log2 fold-change estimates of SKN-1 targets in all RP mutants were plotted. SKN-1 targets were identified from differentially expressed genes upon the constitutive activation of SKN-1 (Nhan et al., 2019).

Given the pronounced overexpression of glutathione transferase (gst) genes (∼2.8-fold enrichment, P < 0.001, GO enrichment), we assessed the expression patterns of gst genes across all RP mutants (Fig. 2 B). The general overexpression signature aligns with previously established links between glutathione transferase activity and oxidative stress resistance (Ayyadevara et al., 2005; Burmeister et al., 2008), prompting us to assess the mutants’ resilience to oxidative stress.

In acute survival assays using high doses of paraquat, we observed that all RP haploinsufficient strains exhibited significantly enhanced resistance to oxidative stress compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 2 C, first and second plot, P < 0.01, Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction). This widespread increase in stress resistance suggests a robust, adaptive mechanism that compensates for elevated ROS levels.

Perturbations in ribosome biogenesis have been shown to elicit proteotoxicity (Tye et al., 2019). Moreover, RP haploinsufficiency reduces ribosome levels (Khajuria et al., 2018), which could lead to a decrease in overall protein synthesis. To determine whether the observed elevated levels of oxidative stress in the mutants were due to proteotoxic stress or were related to a reduction in protein synthesis, we pretreated wild-type animals with inhibitors targeting key pathways: the proteasome (bortezomib), ribosome biogenesis and the translation regulator TORC1 (rapamycin), and translation elongation (cycloheximide) before assessing survival under acute oxidative stress conditions. These treatments significantly enhanced the stress response of wild-type animals (P < 0.05 for each drug, Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction), supporting the role of these pathways in mediating elevated oxidative stress resistance (Fig. S2 A, left panel). Moreover, the combined use of the inhibitors did not further improve survival rates in wild-type animals (Fig. S2 A, right panel). Finally, none of the treatments altered the survival outcomes of rpl-5(0)/+ mutants under oxidative stress (P ≥ 0.4, Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction), suggesting that rpl-5(0)/+ mutants inherently possess an elevated baseline oxidative stress response (Fig. S2 B).

Stress responses in RP haploinsufficient mutants. (A) Survival fractions analyzed after 8 h of acute oxidative stress after pretreatment of rapamycin, bortezomib, and cycloheximide in wild-type animals are shown (left). Wild-type animals pretreated with double combinations of rapamycin, bortezomib, and cycloheximide and survival fraction within 8 h of acute oxidative stress was determined (right). (B) Survival fractions analyzed after 8 h of acute oxidative stress after pretreatment of rapamycin, bortezomib, and cycloheximide in rpl-5(0)/+ mutants are shown. In A and B each point represents a biological replicate and bars represent the median of all biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction. P values are provided on the top of the plot. For the right plot in A all samples were compared to no drug control. The “n = ” on the graphs or legends indicates the total number of animals analyzed. (C) An acute oxidative stress survival time course for skn-1(zj15) and daf-16(mu86), alongside wild-type animals, is shown. skn-1(zj15) and daf-16(mu86) animals are comparable in acute oxidative stress survival compared to wild-type animals (P values are 0.52 and 0.08 for skn-1(zj15) and daf-16(mu86) respectively). (P = 0.85 for comparison of skn-1(zj15) versus daf-16(mu86)). P values were obtained using a Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction to compare the survival distributions of two or more groups for three biological replicates. (D) Density plots of log2 RNA expression differences of HSF-1 targets across all RP haploinsufficient mutants were plotted. HSF-1 targets are the significantly overexpressed genes in response to HSF-1 overexpression (Sural et al., 2019). (E) Acute heat stress survival was assessed in RP mutants, balancer controls, and daf-2(e1370) heat-stress-tolerant mutants after 2 h at 37°C. Statistical analyses were performed using Log-rank test, with Bonferroni correction for multiple samples. All experiments were conducted in three biological replicates, all animals were grown at 16°C. “n” in A–C represents the number of animals. Superscript numbers denote the specific balancers compared between an RP mutant and its wild type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1.

Stress responses in RP haploinsufficient mutants. (A) Survival fractions analyzed after 8 h of acute oxidative stress after pretreatment of rapamycin, bortezomib, and cycloheximide in wild-type animals are shown (left). Wild-type animals pretreated with double combinations of rapamycin, bortezomib, and cycloheximide and survival fraction within 8 h of acute oxidative stress was determined (right). (B) Survival fractions analyzed after 8 h of acute oxidative stress after pretreatment of rapamycin, bortezomib, and cycloheximide in rpl-5(0)/+ mutants are shown. In A and B each point represents a biological replicate and bars represent the median of all biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction. P values are provided on the top of the plot. For the right plot in A all samples were compared to no drug control. The “n = ” on the graphs or legends indicates the total number of animals analyzed. (C) An acute oxidative stress survival time course for skn-1(zj15) and daf-16(mu86), alongside wild-type animals, is shown. skn-1(zj15) and daf-16(mu86) animals are comparable in acute oxidative stress survival compared to wild-type animals (P values are 0.52 and 0.08 for skn-1(zj15) and daf-16(mu86) respectively). (P = 0.85 for comparison of skn-1(zj15) versus daf-16(mu86)). P values were obtained using a Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction to compare the survival distributions of two or more groups for three biological replicates. (D) Density plots of log2 RNA expression differences of HSF-1 targets across all RP haploinsufficient mutants were plotted. HSF-1 targets are the significantly overexpressed genes in response to HSF-1 overexpression (Sural et al., 2019). (E) Acute heat stress survival was assessed in RP mutants, balancer controls, and daf-2(e1370) heat-stress-tolerant mutants after 2 h at 37°C. Statistical analyses were performed using Log-rank test, with Bonferroni correction for multiple samples. All experiments were conducted in three biological replicates, all animals were grown at 16°C. “n” in A–C represents the number of animals. Superscript numbers denote the specific balancers compared between an RP mutant and its wild type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1.

Unfolded protein and oxidative stress responses are mediated through SKN-1, which is orthologous to human NRF2 (Glover-Cutter et al., 2013; Oliveira et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2017; Inoue et al., 2005). SKN-1 further induces a transcriptional response that results in stress resistance when protein translation is inhibited (Wang et al., 2010). Moreover, TORC1 signaling pathway and rapamycin regulate both SKN-1 and DAF-16, orthologous to human FOXO3 (Robida-Stubbs et al., 2012). Additionally, DAF-16 is involved in the repression of RP genes, serving for resistance to hypoxia resistance (Hemphill et al., 2022). Thus, we hypothesized that SKN-1 and DAF-16 might be regulators of the oxidative stress response observed in RP mutants. To dissect these regulatory pathways, we evaluated the oxidative stress survival of rpl-5(0)/+ mutants in combination with mutations in skn-1 and daf-16 genes. The skn-1(zj15) hypomorphic mutation (Tang et al., 2016) in the rpl-5(0)/+ mutant background significantly diminished oxidative stress survival (Fig. 2 C, third plot, P = 0.02, Log-rank test), suggesting that SKN-1 is essential for the resistance of oxidative stress in rpl-5(0)/+ mutants. skn-1(zj15) mutants were not resistant to oxidative stress suggesting that SKN-1 is likely chronically activated in rpl-5(0)/+ mutants (Fig. S2 C, P = 0.52, Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction). We did not observe a significant survival change in rpl-5(0)/+ mutants when crossed with the daf-16(mu86) mutation (Lin et al., 1997), highlighting SKN-1’s unique contribution (Fig. 2 C, fourth plot, P = 0.5, Log-rank test). daf-16(mu86) mutants did not display differential resistance to acute oxidative stress compared with wild-type controls (Fig. S2 C, P = 0.08, Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction). We also observed a mild overexpression of genes upregulated in response to skn-1 gain of function across the RNA-seq datasets for RP haploinsufficient mutants (Fig. 2 D [Nhan et al., 2019]). This finding suggests that SKN-1 activity may not be limited to rpl-5(0)/+ mutants but likely extends to other RP mutants as well.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, aberrations in ribosome biogenesis lead to the upregulation of targets of Hsf1, a key regulator of proteotoxic stress response (Li et al., 2017; Tye et al., 2019; Albert et al., 2019). To investigate whether a similar pattern occurred in our RP haploinsufficient mutants, we examined the expression levels of genes that are known targets of HSF-1 overexpression (Sural et al., 2019). Our analysis indicates a trend toward overexpression of HSF-1-regulated genes in two of the mutants, rpl-33(0)/+ and rps-23(0)/+ (Fig. S2 D). However, the overexpression of HSF-1 targets did not translate into observable differences in acute heat resistance over a 2-h period (Fig. S2 E, P > 0.05). Notably, in C. elegans, the responses to oxidative stress and heat stress act in opposition and attenuate each other’s effects (Crombie et al., 2016). Taken together, these observations suggest that while there may be alterations in the expression of HSF-1 targets under RP haploinsufficiency, this does not necessarily indicate activation of HSF-1 or enhanced stress tolerance. It may point to a complex interplay in the cellular stress response which requires further investigation.

Translational regulation ensures balanced ribosomal expression despite haploinsufficiency

To investigate the impact of single-copy RP gene loss on translation, we used ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) alongside RNA-seq to analyze stage-matched mutant and control C. elegans animals at the L4 developmental stage. This approach allowed us to identify translational efficiency (TE) alterations across four RP mutants (Table S4). Notably, genes such as ccdc-47, ddb-1, F32D1.5, pab-1, and rad-50 exhibited significantly decreased TE across all RP mutants (padj < 0.05), with pab-1 and rad-50 also showing RNA overexpression, hinting at a potential compensatory mechanism in response to reduced TE (Fig. S3 A).

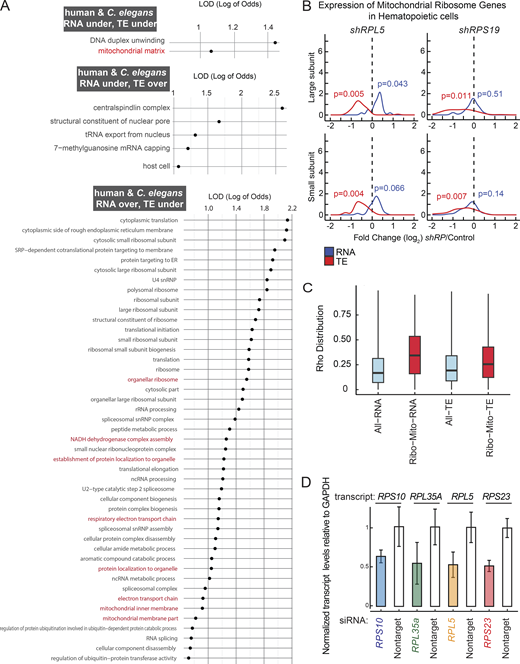

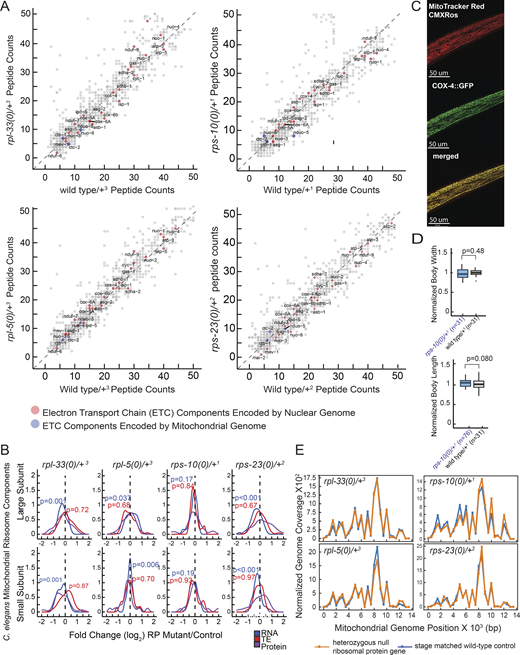

Gene expression and translation efficiency (TE) differences in RP haploinsufficient mutants. (A) RNA and TE log2 ratio estimates for the top five most significant genes for all RP haploinsufficient mutants were plotted. The y-axis shows the log2 fold change predictions, with TE and RNA levels for each mutant labeled in distinct colors. Superscript numbers denote the specific balancers compared between an RP mutant and its wild type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1, +4 = nT1. (B) Heatmap depicting the log2 fold change of each RP gene expression at the RNA, TE, and protein levels for all four different mutants. The heatmap scale on the left represents non-scaled log2 fold ratio estimates. (C) The 28S/18S rRNA ratio was calculated based on area measurements from Bioanalyzer RNA results. The top chart represents an example of a Bioanalyzer result. In the bottom plot, the y-axis shows the 28S/18S ratios, with each point representing a biological replicate. Each RP haploinsufficient mutant sample was compared to stage-matched wild-type control sample using a Student’s t test. All P values were >0.5, indicating no significant differences in the ratios were observed. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (D) RNA expression and TE differences were plotted along the y-axis for all ribosomal protein genes that belong to large subunit (top) and small subunit (bottom) were plotted for shRPL5 and shRPS19 knockdown in hematopoietic cells (Khajuria et al., 2018). For statistical analysis of changes in expression of large and small subunit ribosomal protein genes at RNA and TE level, ROAST multivariate gene expression analysis was conducted (Wu et al., 2010).

Gene expression and translation efficiency (TE) differences in RP haploinsufficient mutants. (A) RNA and TE log2 ratio estimates for the top five most significant genes for all RP haploinsufficient mutants were plotted. The y-axis shows the log2 fold change predictions, with TE and RNA levels for each mutant labeled in distinct colors. Superscript numbers denote the specific balancers compared between an RP mutant and its wild type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1, +4 = nT1. (B) Heatmap depicting the log2 fold change of each RP gene expression at the RNA, TE, and protein levels for all four different mutants. The heatmap scale on the left represents non-scaled log2 fold ratio estimates. (C) The 28S/18S rRNA ratio was calculated based on area measurements from Bioanalyzer RNA results. The top chart represents an example of a Bioanalyzer result. In the bottom plot, the y-axis shows the 28S/18S ratios, with each point representing a biological replicate. Each RP haploinsufficient mutant sample was compared to stage-matched wild-type control sample using a Student’s t test. All P values were >0.5, indicating no significant differences in the ratios were observed. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (D) RNA expression and TE differences were plotted along the y-axis for all ribosomal protein genes that belong to large subunit (top) and small subunit (bottom) were plotted for shRPL5 and shRPS19 knockdown in hematopoietic cells (Khajuria et al., 2018). For statistical analysis of changes in expression of large and small subunit ribosomal protein genes at RNA and TE level, ROAST multivariate gene expression analysis was conducted (Wu et al., 2010).

Further analysis revealed distinct expression trends. Cell matrix adhesion and defense response genes were overexpressed at both RNA and TE levels (Fig. 3 A, “RNA and TE over,” Table S4, significantly enriched GO category list provided in Table S5). In contrast, genes involved in histone H3K36 methylation and sister chromatid segregation were underexpressed at both levels, suggesting a systematic downregulation in these functional categories (Fig. 3 A, “RNA and TE under,” Tables S4 and S5). Given the involvement of H3K36 methylation in processes such as RNA polymerase II–mediated elongation (Carrozza et al., 2005) and the regulation of alternative splicing (Luco et al., 2010), a reduction in the expression of components of this pathway could further contribute to alterations in transcription and the diversity of transcript isoforms being produced.

Translational regulation ensures ribosome balance despite haploinsufficiency. (A) Genes were filtered based on log2 fold-change estimates from RNA-seq, Ribo-seq, and translation efficiency (TE), using the following criteria: (1) over or under expression at both the RNA and TE levels across all mutants, and (2) expression changes in opposite directions at the RNA or TE levels, indicating potential buffering effects. Significant gene ontology (GO) enrichment was performed for each of these categories (upper black panels: RNA and TE over, RNA under TE over, RNA over TE under, RNA and TE under). Log2 fold-change distributions from edgeR predictions were plotted for selected significant GO categories, showing RNA-seq levels (blue), Ribo-seq levels (Ribo, cyan), and TE levels (TE, red). Significant GO annotations are provided below (X/N), where X denotes the number of significantly expressed genes and N represents the total number of genes in the GO category. Each dot in the plot represents a gene differentially expressed in the significant GO category annotated below. (B) Density plots of log2 fold change estimates (RP mutant/control) in RNA, TE, and protein expression for all detected ribosomal protein (RP) genes (large or small subunit) in response to the single-copy loss of each RP haploinsufficient mutant, relative to stage-matched control animals generated. The density lines represent different data types: blue for RNA, red for TE and purple for protein levels. Each RP haploinsufficient mutant genotype is labeled at the top of the plots. The y-axis represents large subunit RP genes in the top row and small subunit RP genes in the bottom row. The x-axis displays the log2 fold-change estimate distributions for RP haploinsufficient/control comparisons. ROAST multivariate gene expression analysis was conducted to calculate P values for RNA and TE level expression differences in small and large subunit RP gene expression. P values provided on the plots (blue and red values represent RNA TE level differences respectively) and indicates significant overexpression of both small and large subunit RP genes at the RNA level in all mutants, while showing significantly decreased TE levels for both subunits across all RP haploinsufficient mutants, except for rps-10(0)/+1. Log2 fold changes in rps-10(0)/+1 are smaller in magnitude, likely due to the relatively modest decrease in RPS-10 protein levels (∼10% decrease, Fig. 1 C).

Translational regulation ensures ribosome balance despite haploinsufficiency. (A) Genes were filtered based on log2 fold-change estimates from RNA-seq, Ribo-seq, and translation efficiency (TE), using the following criteria: (1) over or under expression at both the RNA and TE levels across all mutants, and (2) expression changes in opposite directions at the RNA or TE levels, indicating potential buffering effects. Significant gene ontology (GO) enrichment was performed for each of these categories (upper black panels: RNA and TE over, RNA under TE over, RNA over TE under, RNA and TE under). Log2 fold-change distributions from edgeR predictions were plotted for selected significant GO categories, showing RNA-seq levels (blue), Ribo-seq levels (Ribo, cyan), and TE levels (TE, red). Significant GO annotations are provided below (X/N), where X denotes the number of significantly expressed genes and N represents the total number of genes in the GO category. Each dot in the plot represents a gene differentially expressed in the significant GO category annotated below. (B) Density plots of log2 fold change estimates (RP mutant/control) in RNA, TE, and protein expression for all detected ribosomal protein (RP) genes (large or small subunit) in response to the single-copy loss of each RP haploinsufficient mutant, relative to stage-matched control animals generated. The density lines represent different data types: blue for RNA, red for TE and purple for protein levels. Each RP haploinsufficient mutant genotype is labeled at the top of the plots. The y-axis represents large subunit RP genes in the top row and small subunit RP genes in the bottom row. The x-axis displays the log2 fold-change estimate distributions for RP haploinsufficient/control comparisons. ROAST multivariate gene expression analysis was conducted to calculate P values for RNA and TE level expression differences in small and large subunit RP gene expression. P values provided on the plots (blue and red values represent RNA TE level differences respectively) and indicates significant overexpression of both small and large subunit RP genes at the RNA level in all mutants, while showing significantly decreased TE levels for both subunits across all RP haploinsufficient mutants, except for rps-10(0)/+1. Log2 fold changes in rps-10(0)/+1 are smaller in magnitude, likely due to the relatively modest decrease in RPS-10 protein levels (∼10% decrease, Fig. 1 C).

Interestingly, ribosomal component genes were overexpressed at the RNA level but had reduced TE, notable in both large and small subunit genes (Fig. 3 A, “RNA under TE over” and “RNA over TE under,” respectively, Tables S4 and S5). This differential regulation highlights a complex response that balances transcription and translation in response to RP haploinsufficiency to maintain overall ribosome numbers.

In S. cerevisiae, mutations in small subunit genes do not impact the expression of large subunit genes, resulting in an accumulation of unpaired large subunits (Cheng et al., 2019). In contrast, our observations in C. elegans indicate a coordinated response across both subunits at the RNA and TE levels: reductions in RPs from either subunit led to a generalized overexpression at the RNA levels (P ≤ 0.01 except rps-10(0)/+, ROAST–rotation gene set testing [Wu et al., 2010]), but a decrease in TE levels (P ≤ 0.05 for rpl-33(0)+ and rpl-5(0)/+, ROAST) (Fig. 3 B and Fig. S3 B). To assess the potential accumulation of unpaired subunits, we analyzed 28S/18S ratios by measuring the area underneath 28S and 18S peaks in total RNA samples from RP haploinsufficient and wild-type animals using Bioanalyzer. We did not observe significant changes in this ratio (Fig. S3 C, P > 0.05; RP haploinsufficient mutants were compared to wild-type controls using Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction). Given that such a response was not observed in yeast, we asked whether a similar response occurs in response to DBA-specific RP gene reductions in human hematopoietic cells (Khajuria et al., 2018). Reanalyzing the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq datasets from this study revealed that the results in C. elegans mirror those from human RPL5 and RPS19 knockdowns in hematopoietic cells, where TE of all subunits are significantly decreased (Fig. S3 D, P < 0.05, ROAST, Table S6). Hence, the human cellular response is more similar to that in C. elegans, in comparison to yeast, highlighting a potentially conserved regulatory mechanism regulating translation for maintaining ribosome production under conditions of single-copy loss of RP genes.

Mitochondrial translation and morphology differences in response to ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency

In RP haploinsufficient mutants, we observed upregulation of glutathione transferase activity and potential activation of SKN-1, a critical factor in maintaining cellular redox balance and facilitating mitochondrial retrograde signaling (Palikaras et al., 2015; Dinkova-Kostova and Abramov, 2015). These observations suggest a potential impairment in mitochondrial function. In particular, genes of the electron transport chain (ETC) require coordinated translation by both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ribosomes, creating a vulnerability in proteostasis (Soto et al., 2022).

We next compared changes in RNA expression and TE of ETC components across RP mutants. While we did not observe significant changes in the expression of nuclear-encoded or mitochondrially encoded ETC components at the RNA level (Fig. 4 A, left, P > 0.1, ROAST), a distinct pattern emerged at the TE level. Nuclear-encoded components remained unaffected (P > 0.4), whereas mitochondrial-encoded ETC components showed reduced TE across all mutants (Fig. 4 A, right, P < 0.005 for rpl-33(0)/+ and rpl-5(0)/+ and P ≤ 0.16 for rps-10(0)/+ and rps-23(0)/+, ROAST). This discrepancy suggests that the impaired mitochondrial translation may indirectly affect the stoichiometry of ETC. Although proteomics-level measurements lacked sufficient coverage to quantify corresponding changes in protein abundance for ETC components, the mitochondrially encoded Complex-I component, NDUO-5, was notably underexpressed in rps-10(0)/+ animals (∼70% reduction, Padj = 0.2, Fig. S4 A and Table S1).

Mitochondrial translation and morphology in response to RP haploinsufficiency in C. elegans. (A) Log2 fold change estimates in RNA and translation efficiency (TE) levels were plotted along the y-axis for mitochondrial-encoded (mito) or nuclear-encoded (nuclear) electron transport chain (ETC) genes, as well as for a randomly selected gene set, for each RP haploinsufficient mutant. Log2 fold changes for RNA and TE were plotted on the left and right sections, respectively, and are labeled at the top. Each row represents a different RP haploinsufficient mutant, with the genotype labeled on the right-most side. On the x-axis, “mito” and “nuclear” represent mitochondrially and nuclear-encoded ETC component genes, respectively. The “random” set represents a group of random genes, equal in size to the nuclear-encoded ETC component gene set. For statistical comparison of RNA and TE expression differences in mitochondrial or nuclear-encoded ETC genes. ROAST multivariate gene expression analysis was conducted (Wu et al., 2010). The P values derived from the ROAST analysis are indicated on each box plot. According to this analysis, mitochondrially encoded transcripts are translated significantly less in rpl-5(0)/+ and rpl-33(0)/+ mutants (P < 0.005). While the overall distribution is lower in rps-10 (0)/+ and rps-23(0)/+, the changes are more modest and not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Superscript numbers denote the specific wild type balancer chromosomes and are used to compare an RP mutant and the wild-type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1. (B) Representative mitochondrial morphology images using mitochondrial and nuclear-localized GFP in body wall muscle cells in RP mutants as well as stage-matched wild-type controls. Day 3 adult animals, which were transferred from 16°C to 23°C on the last 2 days were imaged. RP mutants in this analysis do not have a balancer chromosome. Images were taken with Stellaris Confocal with a 63× objective, and the scale bar represents 10 µm. (C) Distribution of mitochondrial morphological measurements of mutant and control animals. GFP signal localized to mitochondria was used to identify mitochondrial objects. Each mitochondrion was measured using convexity (degree to which shape differs from its convex hull), defect area (area outside of convex hull), and skeleton branch length. Mean measurements are represented as points, and the black dashed line corresponds to the wild-type mean. A two-sided Welch’s two-sample t test was used to compare differences in the mean measurement across each mutant relative to the wild type. Experiments in B and C were conducted with three biological replicates, analyzing multiple body wall muscle cells from at least nine animals per group (with >103 mitochondria measurements per strain). Two mitochondria images per mutant and wild type were shown in B to represent variability of mitochondrial morphology per body wall cell.

Mitochondrial translation and morphology in response to RP haploinsufficiency in C. elegans. (A) Log2 fold change estimates in RNA and translation efficiency (TE) levels were plotted along the y-axis for mitochondrial-encoded (mito) or nuclear-encoded (nuclear) electron transport chain (ETC) genes, as well as for a randomly selected gene set, for each RP haploinsufficient mutant. Log2 fold changes for RNA and TE were plotted on the left and right sections, respectively, and are labeled at the top. Each row represents a different RP haploinsufficient mutant, with the genotype labeled on the right-most side. On the x-axis, “mito” and “nuclear” represent mitochondrially and nuclear-encoded ETC component genes, respectively. The “random” set represents a group of random genes, equal in size to the nuclear-encoded ETC component gene set. For statistical comparison of RNA and TE expression differences in mitochondrial or nuclear-encoded ETC genes. ROAST multivariate gene expression analysis was conducted (Wu et al., 2010). The P values derived from the ROAST analysis are indicated on each box plot. According to this analysis, mitochondrially encoded transcripts are translated significantly less in rpl-5(0)/+ and rpl-33(0)/+ mutants (P < 0.005). While the overall distribution is lower in rps-10 (0)/+ and rps-23(0)/+, the changes are more modest and not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Superscript numbers denote the specific wild type balancer chromosomes and are used to compare an RP mutant and the wild-type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1. (B) Representative mitochondrial morphology images using mitochondrial and nuclear-localized GFP in body wall muscle cells in RP mutants as well as stage-matched wild-type controls. Day 3 adult animals, which were transferred from 16°C to 23°C on the last 2 days were imaged. RP mutants in this analysis do not have a balancer chromosome. Images were taken with Stellaris Confocal with a 63× objective, and the scale bar represents 10 µm. (C) Distribution of mitochondrial morphological measurements of mutant and control animals. GFP signal localized to mitochondria was used to identify mitochondrial objects. Each mitochondrion was measured using convexity (degree to which shape differs from its convex hull), defect area (area outside of convex hull), and skeleton branch length. Mean measurements are represented as points, and the black dashed line corresponds to the wild-type mean. A two-sided Welch’s two-sample t test was used to compare differences in the mean measurement across each mutant relative to the wild type. Experiments in B and C were conducted with three biological replicates, analyzing multiple body wall muscle cells from at least nine animals per group (with >103 mitochondria measurements per strain). Two mitochondria images per mutant and wild type were shown in B to represent variability of mitochondrial morphology per body wall cell.

Analysis of electron transport chain (ETC) component peptide counts, mitochondrial ribosome expression, mitoTracker CMXRos staining and mitochondrial abundance and DNA coverage in haploinsufficient RP mutants. (A) Raw peptide counts from all three replicates were combined to analyze the ETC components, differentiating between those encoded by nuclear genes (red) and those encoded by mitochondrial genes (blue). Although coverage of mitochondrially encoded ETC components was lower, nuclear-encoded components showed a nearly diagonal pattern, indicating minimal deviation from expected levels. The y-axes of all four graphs display peptide reads from heterozygous ribosomal protein mutants, while the x-axes correspond to stage-matched wild-type controls. (B) Overall, RNA expression, TE, and protein level changes of all mitochondrial RP genes were plotted in RP haploinsufficient mutants. Y-axes show mitochondrial ribosomal proteins that belong to large or small subunits (top and bottom plots, respectively) and x-axes show log2 fold changes that were predicted by EdgeR for RNA and TE, and by DEP for proteins. For statistical analysis, ROAST multivariate gene expression analysis was conducted (Wu et al., 2010). (C) Staining specificity was assessed through co-localization studies using a C. elegans strain with a CRISPR-engineered knock-in of cox-4 gene tagged with GFP (cox-4::GFP), serving as a marker for mitochondrial inner membranes. These co-localization analyses were conducted using a Leica Stellaris Confocal System equipped with a 63× objective. A representative image is shown with MitoTracker CMXRos staining (left), COX::GFP (middle) and merged images (right). Yellow color indicates co-localization of the staining with the mitochondrial inner membrane marker, COX-4. (D) Body length and width were assessed for stage-matched rps-10(0)/+ and wild-type controls used in oxygen consumption experiments depicted in Fig. 5 C. (E) Mitochondrial genome coverage was charted for heterozygous C. elegans mutants and stage-matched wild-type controls. The x-axes represent mitochondrial genome positions, and the y-axes show mitochondrial genome coverage normalized to the nuclear genome. Orange lines indicate heterozygous mutant animals, and blue lines represent stage-matched wild-type controls at the L4 stage. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4 C.

Analysis of electron transport chain (ETC) component peptide counts, mitochondrial ribosome expression, mitoTracker CMXRos staining and mitochondrial abundance and DNA coverage in haploinsufficient RP mutants. (A) Raw peptide counts from all three replicates were combined to analyze the ETC components, differentiating between those encoded by nuclear genes (red) and those encoded by mitochondrial genes (blue). Although coverage of mitochondrially encoded ETC components was lower, nuclear-encoded components showed a nearly diagonal pattern, indicating minimal deviation from expected levels. The y-axes of all four graphs display peptide reads from heterozygous ribosomal protein mutants, while the x-axes correspond to stage-matched wild-type controls. (B) Overall, RNA expression, TE, and protein level changes of all mitochondrial RP genes were plotted in RP haploinsufficient mutants. Y-axes show mitochondrial ribosomal proteins that belong to large or small subunits (top and bottom plots, respectively) and x-axes show log2 fold changes that were predicted by EdgeR for RNA and TE, and by DEP for proteins. For statistical analysis, ROAST multivariate gene expression analysis was conducted (Wu et al., 2010). (C) Staining specificity was assessed through co-localization studies using a C. elegans strain with a CRISPR-engineered knock-in of cox-4 gene tagged with GFP (cox-4::GFP), serving as a marker for mitochondrial inner membranes. These co-localization analyses were conducted using a Leica Stellaris Confocal System equipped with a 63× objective. A representative image is shown with MitoTracker CMXRos staining (left), COX::GFP (middle) and merged images (right). Yellow color indicates co-localization of the staining with the mitochondrial inner membrane marker, COX-4. (D) Body length and width were assessed for stage-matched rps-10(0)/+ and wild-type controls used in oxygen consumption experiments depicted in Fig. 5 C. (E) Mitochondrial genome coverage was charted for heterozygous C. elegans mutants and stage-matched wild-type controls. The x-axes represent mitochondrial genome positions, and the y-axes show mitochondrial genome coverage normalized to the nuclear genome. Orange lines indicate heterozygous mutant animals, and blue lines represent stage-matched wild-type controls at the L4 stage. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4 C.

Given the marked reduction in the TE of mitochondrial-encoded ETC components across all mutants, we investigated if there was a corresponding change in the abundance of mitochondrial ribosomes. Mitochondrial RP mRNAs were generally mildly reduced (P < 0.05 for rpl-33(0)/+, rpl-5(0)/+ and rps-23(0)/+; P < 0.2 for rps-10(0)/+, ROAST); however, no consistent changes were observed at the TE levels (Fig. S4 B, P > 0.5 for all mutants). Similarly, changes at the protein level were not consistent with a wider distribution of mitochondrial RPs in rps-23(0)/+ animals (Fig. S4 B). These results suggest that the observed variations in TE across ETC components may be due to impaired mitochondrial translation rather than differences in mitochondrial ribosome abundance.

The trend of elevated expression of gst genes and SKN-1-mediated oxidative stress regulation, both indicative of increased ROS, alongside reduced TE of mitochondrially encoded ETC components in RP mutants, pointed toward potential mitochondrial dysfunction. Previous studies on mitochondrial dynamics established a link between mitochondrial dysfunction and morphological changes, particularly under stress (Zemirli et al., 2018). Specifically, fission-induced mitochondrial fragmentation, characterized by round mitochondria as opposed to networked mitochondria, is associated with increased ROS and elevated oxidative stress (Yu et al., 2006; Qi et al., 2011).

To investigate the impact of RP haploinsufficiency on mitochondrial morphology, we introduced a body-wall-specific nuclear and mitochondrial GFP marker into the backgrounds of RP haploinsufficient mutants (Ahnn and Fire, 1994). No differences were observed at 16°C up to the L4 stage, but upon transferring the L4 animals to 23°C and imaging by day 3 of adulthood, we detected partially penetrant increases in mitochondrial fragmentation across all mutants (Fig. 4 B). To quantify fragmentation, we measured the convexity (the degree to which shape differs from its convex hull), defect area (area outside of convex hull) and skeleton branch length of each individual mitochondria. Our results reveal that on average, mitochondria from rps-10(0)/+, rps-23(0)/+, and rpl-5(0)/+ are significantly more convex, or less networked, compared with wild-type control animals (Fig. 4 C, first plot, P < 0.001, Student’s t test). Similarly, all four mutants had a significant average decrease in mean defect area and branch length relative to wild-type control animals (Fig. 4 C, second and third plots, P < 0.001, Student’s t test). Together, these results suggest that RP mutants have increased mitochondrial fragmentation that may indicate underlying mitochondrial dysfunction that is both temperature-sensitive and age-related. These results suggest that RP mutants struggle to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis, particularly under moderately higher temperatures, pointing toward a vulnerability in their ability to adapt to environmental conditions.

Mitochondrial function is compromised in rps-10(0)/+ mutants

The changes in mitochondrial morphology among RP mutants prompted us to investigate mitochondrial function. Given the link between mitochondrial structure and metabolism (Westermann, 2010), we next evaluated mitochondrial membrane potential using MitoTracker Red CMXRos staining (Sarasija and Norman, 2018) (Fig. S4 C) and analyzed the overall energy status of the animals by measuring their relative ADP/ATP ratios (Palikaras et al., 2015).

The rps-10(0)/+ mutants exhibited significant decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential, as indicated by significant MitoTracker accumulation (P < 0.001, independent Student’s t test) and elevated ADP/ATP ratios (P = 0.003, paired Student’s t test), compared with stage-matched controls (Fig. 5, A and B). These results reveal that the rps-10(0)/+ mutants display a significant disruption in cellular energy homeostasis in addition to compromised mitochondrial membrane potential.

Mitochondrial function and energy levels are compromised in rps-10(0)/+ mutants. (A) Mitochondrial activity, quantified via the uptake of fluorescent MitoTracker Red CMXRos dye in each RP mutant compared to its wild-type counterpart. MitoTracker intensity per area was measured, and the values for RP animals were normalized to the median of stage-matched wild-type controls and plotted. P values represent the results of a two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction comparing each RP haploinsufficient mutant sample to its stage-matched wild-type control. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (B) The ADP/ATP ratio, reflecting overall energy levels of RP haploinsufficient animals normalized to stage-matched controls is shown for each mutant. Measurements were taken from ∼50 RP mutant and wild-type animals per biological replicate, with each replicate represented as a single dot on the plot. (C) The relative oxygen consumption of rps-23(0)/+ and rps-10(0)/+ mutants compared to wild type was plotted. Animals were stage-matched to ensure similar body sizes, and oxygen consumption rates were normalized to the number of animals utilized in each assay. In B and C each point reflects the ratio of RP haploinsufficient animals to respective wild-type controls per biological replicate. The bold line represents the median. P values represent the results of a paired, two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction comparing each RP haploinsufficient mutant to its stage-matched wild-type control. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (D) The genetic modification strategy for the rps-10 gene is illustrated. The wild-type rps-10 gene with the PAM sequence highlighted in purple is shown on top; the introduction of tandem early stop codons, generating the rps-10(0) variant with a new PAM sequence in purple is indicated in the middle; the restoration of rps-10(0) to its wild-type sequence marked in green is demonstrated at bottom. (E) The normalized MitoTracker intensity was compared in wild type and two [rps-10(0) to wild-type] rescued strains (rescue-1, rescue-2). P values represent the results of a two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction comparing each rescue strain to the stage-matched wild-type controls. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (F) The normalized oxygen consumption was compared in wild type and two [rps-10(0) to wild-type] rescued strains (rescue-1, rescue-2). P values represent the results of a paired, two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction comparing each rescue strain to the stage-matched wild-type control. (G) The relative intensity distribution of TOMM-20::TagRFP and COX-4::GFP levels in rps-10 (0)/+ mutants and stage-matched wild-type controls are shown. Fluorescence intensities rps-10 (0)/+ mutant animals were normalized to the median of stage matched wild-type intensities. P values represent a two-tailed Student’s t test. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. The bar represents interquartile distribution and the bold horizontal line represents the median. (H) Normalized oxygen consumption rates were plotted for gcn-1(n4827) mutants and gcn-1 RNAi compared to their controls (wild type and non-target RNAi) (left). The effects of rps-10 and rps-23 RNAi in a wild-type background (middle), alongside the rps-10 and gas-1 RNAi effects in gcn-1(n4827) mutants (right), with respective controls for each group are shown. Each point represents the ratio of gene-specific RNAi to the respective non-target RNAi for each biological replicate. The bold line indicates the median. P values represent the results of a paired, two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction, comparing each gene-specific RNAi to the non-target RNAi control. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. All experiments were performed in at least three biological replicates, and the animals were grown at 16°C. Superscript numbers denote the specific balancers compared between an RP mutant and its wild type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1, +4 = nT1. “n” at the top of each graph represents the total number of animals when all biological replicates combined. For comparisons, roughly equal number of animals were used.

Mitochondrial function and energy levels are compromised in rps-10(0)/+ mutants. (A) Mitochondrial activity, quantified via the uptake of fluorescent MitoTracker Red CMXRos dye in each RP mutant compared to its wild-type counterpart. MitoTracker intensity per area was measured, and the values for RP animals were normalized to the median of stage-matched wild-type controls and plotted. P values represent the results of a two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction comparing each RP haploinsufficient mutant sample to its stage-matched wild-type control. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (B) The ADP/ATP ratio, reflecting overall energy levels of RP haploinsufficient animals normalized to stage-matched controls is shown for each mutant. Measurements were taken from ∼50 RP mutant and wild-type animals per biological replicate, with each replicate represented as a single dot on the plot. (C) The relative oxygen consumption of rps-23(0)/+ and rps-10(0)/+ mutants compared to wild type was plotted. Animals were stage-matched to ensure similar body sizes, and oxygen consumption rates were normalized to the number of animals utilized in each assay. In B and C each point reflects the ratio of RP haploinsufficient animals to respective wild-type controls per biological replicate. The bold line represents the median. P values represent the results of a paired, two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction comparing each RP haploinsufficient mutant to its stage-matched wild-type control. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (D) The genetic modification strategy for the rps-10 gene is illustrated. The wild-type rps-10 gene with the PAM sequence highlighted in purple is shown on top; the introduction of tandem early stop codons, generating the rps-10(0) variant with a new PAM sequence in purple is indicated in the middle; the restoration of rps-10(0) to its wild-type sequence marked in green is demonstrated at bottom. (E) The normalized MitoTracker intensity was compared in wild type and two [rps-10(0) to wild-type] rescued strains (rescue-1, rescue-2). P values represent the results of a two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction comparing each rescue strain to the stage-matched wild-type controls. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (F) The normalized oxygen consumption was compared in wild type and two [rps-10(0) to wild-type] rescued strains (rescue-1, rescue-2). P values represent the results of a paired, two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction comparing each rescue strain to the stage-matched wild-type control. (G) The relative intensity distribution of TOMM-20::TagRFP and COX-4::GFP levels in rps-10 (0)/+ mutants and stage-matched wild-type controls are shown. Fluorescence intensities rps-10 (0)/+ mutant animals were normalized to the median of stage matched wild-type intensities. P values represent a two-tailed Student’s t test. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. The bar represents interquartile distribution and the bold horizontal line represents the median. (H) Normalized oxygen consumption rates were plotted for gcn-1(n4827) mutants and gcn-1 RNAi compared to their controls (wild type and non-target RNAi) (left). The effects of rps-10 and rps-23 RNAi in a wild-type background (middle), alongside the rps-10 and gas-1 RNAi effects in gcn-1(n4827) mutants (right), with respective controls for each group are shown. Each point represents the ratio of gene-specific RNAi to the respective non-target RNAi for each biological replicate. The bold line indicates the median. P values represent the results of a paired, two-tailed Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction, comparing each gene-specific RNAi to the non-target RNAi control. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. All experiments were performed in at least three biological replicates, and the animals were grown at 16°C. Superscript numbers denote the specific balancers compared between an RP mutant and its wild type counterpart. Balancer chromosomes are denoted as follows: +1 = tmC20, +2 = tmC5, +3 = mIn1, +4 = nT1. “n” at the top of each graph represents the total number of animals when all biological replicates combined. For comparisons, roughly equal number of animals were used.

Having observed disruptions in mitochondrial function in rps-10(0)/+ but not large subunit RP mutants, we assayed oxygen consumption rates in small subunit RP mutants. rps-10(0)/+ mutants showed a reduction in oxygen consumption in comparison to stage-matched controls (P < 0.05, paired Student’s t test), a trend not observed in rps-23(0)/+ (P > 0.1, paired Student’s t test) (Fig. 5 C). To ensure decreased oxygen consumption is not due to smaller body size, we quantified the body length and width of rps-10(0)/+ animals, relative to controls, and found no significant difference between them (Fig. S4 D, width P = 0.48, length P = 0.080).

Given that energy and mitochondrial functionality changes were specific to the rps-10(0)/+ mutants, we sought to determine if they were caused by a background mutation introduced during the CRISPR-mediated early stop integration or possibly due to the maternal inheritance of defective mitochondria. To address these possibilities, rps-10(0)/+ hermaphrodites were used to reintroduce the wild-type rps-10 sequence, leveraging the unique SuperPAM (GGNGG) sequence inserted during the creation of the mutation (Fig. 5 D). This procedure yielded two independent wild-type rescue strains from the F1 generation, each carrying two copies of the reverted wild-type rps-10 gene. These strains displayed MitoTracker intensities and oxygen consumption rates comparable with control groups, suggesting the observed mitochondrial defects are specific to the single-copy loss of the rps-10 gene and not related to mitochondrial biogenesis or maternal inheritance (Fig. 5, E and F, P > 0.4, independent and paired Student’s t test, respectively).

Additionally, we investigated whether mitochondrial defects observed in rps-10(0)/+ mutants stemmed from changes in mitochondrial biogenesis or overall abundance. Specifically, we measured mitochondrial DNA levels and observed no differences in mitochondrial DNA content when compared with stage-matched wild-type controls (Fig. S4 E). Furthermore, we integrated fluorescent reporters for outer and inner mitochondrial membrane components (TOMM-20::Tag-RFP and COX-4::GFP [Raiders et al., 2018]) into rps-10(0)/+ mutants and detected no significant differences in fluorescence intensity compared with stage-matched controls (Fig. 5 G, P > 0.3, independent Student’s t test). Taken together, these results indicate that the observed mitochondrial respiration deficits in rps-10(0)/+ animals are due to defects in mitochondrial functionality rather than decreased abundance.