Autophagy is a conserved degradative process that promotes cellular homeostasis under stress conditions. Under nutrient starvation, autophagy is nonselective, promoting indiscriminate breakdown of cytosolic components. Conversely, selective autophagy is responsible for the specific turnover of damaged organelles. We hypothesized that selective autophagy may be regulated by signaling pathways distinct from those controlling starvation-induced autophagy, thereby promoting organelle turnover. To address this question, we conducted kinome-wide CRISPR screens to identify distinct signaling pathways responsible for the regulation of basal autophagy, starvation-induced autophagy, and two types of selective autophagy, ER-phagy and pexophagy. These parallel screens identified both known and novel autophagy regulators, some common to all conditions and others specific to selective autophagy. More specifically, CDK11A and NME3 were further characterized to be selective ER-phagy regulators. Meanwhile, PAN3 and CDC42BPG were identified as an activator and inhibitor of pexophagy, respectively. Collectively, these datasets provide the first comparative description of the kinase signaling that defines the regulation of selective autophagy and bulk autophagy.

Introduction

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is driven by the formation of a double-membrane vesicle called an autophagosome that sequesters cytosolic cargo for degradation (Kaur and Debnath, 2015). Autophagosome formation is mediated through the activity of a conserved group of autophagy-related (ATG) proteins (Kaur and Debnath, 2015). ULK1, a serine/threonine kinase, promotes autophagosome biogenesis by phosphorylating and activating multiple ATG proteins, thereby driving stress-induced autophagy (Russell et al., 2013; Alsaadi et al., 2019; Park et al., 2016, 2018; Di Bartolomeo et al., 2010). Maturation of the autophagosome and sequestration of targeted cargo require the lipidation of ATG8 family members (LC3A, LC3B, and LC3C, GABARAP, GABARAPL1, and GABARAPL2) to the lipid phosphatidylethanolamine (Martens and Fracchiolla, 2020). LC3B is the best studied member of the ATG8 family in mammals (Lystad et al., 2019; Mizushima et al., 2011). Autophagy was originally described as a bulk degradation pathway that indiscriminately engulfs and degrades cytosolic components (Mortimore and Schworer, 1977). However, the importance of autophagy as a targeted degradation pathway has been established in normal and disease biology (Levine and Kroemer, 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2023).

The targeted degradation of cargo by the autophagy pathway is called selective autophagy, which can be categorized into various subgroups based on the specific cellular components targeted for degradation (Svenning and Johansen, 2013; Kim et al., 2016). Selective autophagy not only requires all the core ATG proteins of bulk autophagy, but also includes a class of proteins called autophagy receptors (Zaffagnini and Martens, 2016; Shuling et al., 2017). Autophagy receptors can be divided into ubiquitin-bound and membrane-associated groups (Kim et al., 2016; Vargas et al., 2023). Well-known ubiquitin-bound receptors, such as SQSTM1/p62, NBR1, NDP52, and OPTN, typically contain both LC3-interacting region (LIR) and ubiquitin-binding domains that allow them to recruit ubiquitinated targets to autophagosomes for degradation (Kim et al., 2016). Membrane-bound receptors localize to, or are constitutively present on the target organelles and are responsible for damaged organelle recognition by autophagy machinery (Anding and Baehrecke, 2017). Importantly, defective selective autophagy has been implicated in several human diseases (Ryter et al., 2013; Ichimiya et al., 2020). Despite increasing evidence for defects in selective autophagy receptors in disease, comparatively less is known about the upstream regulation governing the selective acquisition of autophagic cargo.

Mitophagy (mitochondrial degradation) and xenophagy (pathogen clearance) have been extensively studied, but ER-phagy (endoplasmic reticulum removal) and pexophagy (peroxisomal degradation) remain underexplored (Cho et al., 2018; Reggiori and Molinari, 2022). Thus, in this study, we chose ER-phagy and pexophagy as our models of selective autophagy. Selective autophagic degradation of the ER is a homeostatic mechanism that regulates the maintenance of ER size, the removal of aggregated or misfolded proteins, and the turnover of ER membranes following damage (Mochida and Nakatogawa, 2022). To date, at least six ER-phagy receptors have been identified in mammals, including FAM134B, RTN3L, CCPG1, SEC62, TEX264, and ATL3 (Chen et al., 2019b; Smith et al., 2018; Grumati et al., 2017; An et al., 2019; Chino et al., 2019; Fumagalli et al., 2016; Khaminets et al., 2015). These receptors localize to ER subcompartments and are capable of recruiting autophagy machinery to the ER through LIR/GABARAP-interacting regions (Chino and Mizushima, 2020). For instance, FAM134B primarily facilitates the degradation of sheet ER, while ATL3 and RTN3L mediate degradation of tubular ER (Chen et al., 2019b; Grumati et al., 2017; Khaminets et al., 2015). Some receptors, such as CCPG1 and TEX264, also interact with upstream autophagy complexes like FIP200 and WIPI2 to promote phagophore expansion at the ER (Smith et al., 2018; Chino et al., 2019). In addition to autophagy receptors, new pathways including mitochondrial metabolism and UFMylation have been reported to regulate ER-phagy (Liang et al., 2020). While the key receptors and core machinery involved in ER-phagy have been identified, the regulatory pathways that determine its activation over other selective autophagy pathways remain poorly understood.

Peroxisomes are single membrane–bound organelles essential for reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism and fatty acid oxidation (Lazarow and De Duve, 1976; Mihalik et al., 1995; Poirier et al., 2006). Their homeostasis is regulated by peroxin (PEX) proteins, and stress conditions like starvation or ROS disrupt this balance, triggering autophagic degradation (Walter et al., 2014; Sargent et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2015; Germain and Kim, 2020). Proper matrix protein import, involving PEX2, PEX5, PEX13, and PEX14, is crucial for peroxisome function and quality control (Germain and Kim, 2020; Demers et al., 2023). Under stress, PEX2 ubiquitinates peroxisomal membrane protein 70 (PMP70) and PEX5, targeting peroxisomes for degradation via NBR1 and p62 (Sargent et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2015). PEX14 and PEX13 also promote pexophagy during starvation, while elevated ROS and hypoxia enhance PEX5 ubiquitination (Hara-Kuge and Fujiki, 2008; Demers et al., 2023; Germain and Kim, 2020; Zhang et al., 2015; Schönenberger and Kovacs, 2015). Conversely, the AAA-type ATPase PEX1-PEX6-PEX26 and the deubiquitinase USP30 remove ubiquitinated peroxisomal proteins from the membrane, thereby inhibiting pexophagy (Law et al., 2017; Marcassa et al., 2018; Riccio et al., 2019).

Kinase-mediated phosphorylation plays important roles in the regulation of autophagy initiation. Induction of the autophagy pathway is best characterized in the context of nutrient starvation, where nutrient-sensitive kinases, including mTORC1 and AMPK, are critical for modulating autophagy activation (Balgi et al., 2009; Garcia and Shaw, 2017; Kim et al., 2011; Jung et al., 2010). Under nutrient sufficiency, mTORC1 suppresses autophagy through direct phosphorylation of several components associated with autophagy induction including ULK1 (King et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2011; Shang et al., 2011; Puente et al., 2016). Specifically, upon starvation, mTORC1 is inactivated, which results in ULK1 release from inhibitory phosphorylation and subsequent autophagy induction (Alers et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2011). AMPK activity under energy and nutrient starvation can regulate autophagy through modulation of ULK1 and mTORC1 activity (Kim et al., 2011; Gwinn et al., 2008; Alers et al., 2012). In addition, AMPK and mTORC1 have been reported to directly regulate the activity of the VPS34 kinases, ensuring a precisely controlled initiation of autophagy in response to various cellular stresses (Yuan et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013). Collectively, these nutrient-dependent kinases play an essential role in mediating the activation of bulk autophagy in response to starvation.

Several genome- and kinome-wide screens have identified bulk autophagy regulators using LC3 or p62 reporters and RNAi or CRISPR/Cas9 targeting (Lipinski et al., 2010; Szyniarowski et al., 2011; Frankel et al., 2011; Hale et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2018; Mimura et al., 2021; DeJesus et al., 2016; Chan et al., 2007; McKnight et al., 2012; Morita et al., 2018). Focus has more recently shifted toward selective autophagy regulation. For example, a genome-wide screen using an ER-phagy–specific reporter identified the UFMylation pathway as a mediator of ER-phagy (Liang et al., 2020). Meanwhile, a different screen for regulators of PARKIN stability revealed transcriptional repression as a mediator of mitophagy (Potting et al., 2018). Identification of signaling specificity underlying selective autophagy by comparing results in the studies above is significantly limited by the use of different reporters, stress conditions, cell lines, and screen-related experimental variation. To uncover signaling that demarcates selective vs. bulk autophagy, screening conditions must be carefully designed to rule out changes in total autophagy, crosstalk between selective and bulk autophagy, reporter limitations, and generation of secondary or artifactual hits.

We hypothesized that uncharacterized kinase signaling influences cargo-specific autophagy, akin to how mTORC1 and AMPK regulate starvation-induced autophagy. To explore this, we created a stable monoclonal HEK293A cell line expressing the DsRed-IRES-GFP-p62 autophagy reporter, enabling sensitive, real-time tracking of both selective and bulk autophagy via a single validated readout. Using this cell line, we conducted pooled kinome-wide CRISPR screens under different acute stressors, keeping the cell population constant. This approach revealed stress-specific signaling pathways regulating ER-phagy and pexophagy, distinct from those controlling basal or starvation-induced autophagy.

Results

A kinome-scale CRISPR screen using an autophagic flux reporter

To measure autophagy rates in a high-throughput, quantitative manner, we first generated a stable cell line with a fluorescent marker of autophagy flux, p62. p62 was chosen for this study because it binds diverse ubiquitinated cargo and functions across nearly all forms of selective autophagy, making it a common reporter for comparing both selective and bulk autophagy. To measure changes in autophagic flux, we constructed a dual-fluorescence reporter cell line expressing DsRed-IRES-GFP-p62 (Fig. 1 A). HEK293A cells were stably transduced with constructs expressing GFP-tagged p62 with an internal DsRed control (DsRed-IRES-GFP-p62, Fig. 1 A). To mitigate expression changes from lentiviral insertion, we generated monoclonal reporter populations and assessed responses to amino acid starvation, a potent inducer of autophagy, using flow cytometry; measuring p62 levels (GFP) while controlling for nonselective changes in protein abundance (DsRed control, Fig. 1 A, right panel). Levels of p62 decrease during autophagy activation, resulting in a left shift in the GFP fluorescence signal (Fig. 1 A, right panel). Conversely, autophagy inhibition leads to a right shift in the GFP signal (Fig. 1 A, right panel). We benchmarked our DsRed-IRES-GFP-p62 reporter line under acute amino acid starvation, a potent inducer of autophagy, using both western blot (WB) and flow cytometry. Acute starvation led to robust clearance of tagged p62 without affecting the DsRed control, with maximal p62 degradation observed at 3 h (Fig. 1 B, left panel). Flow cytometry confirmed a similar reduction in GFP signal, while DsRed fluorescence remained unchanged (Fig. 1 B, right panel).

Generation of an autophagic flux reporter sensitive to differential autophagy-inducing stressors. (A) Schematic representation of the autophagic flux reporter DsRed and GFP-tagged p62. p62 is selectively incorporated into and degraded along with the autophagosomal membrane. Therefore, the level of GFP-p62, relative to DsRed, is inversely proportional to autophagic flux. Examples of autophagy activation and inhibition were demonstrated using the histogram in the right panel. (B) HEK293A reporter cell line was treated with starvation in time- and concentration-dependent manners. WB was used to examine DsRed and GFP-p62 signals. FACS was employed to investigate GFP and DsRed fluorescence of the reporter cells treated with amino acid–free media (-AA) for 3 h. Histograms were used to depict changes in GFP-p62 and DsRed levels. (C) Reporter cell line was incubated with tunicamycin in time- and concentration-dependent manners. DsRed and GFP-p62 were analyzed using WB. FACS was used to examine GFP and DsRed signals of the reporter cells exposed to tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. Histograms were used to depict changes in GFP-p62 and DsRed levels. (D) Reporter cells were incubated with clofibrate in time- and concentration-dependent manners. DsRed and p62 levels were examined using WB. FACS was employed to investigate GFP and DsRed fluorescence of the reporter cells treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. Histograms were used to depict changes in GFP-p62 and DsRed levels. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Generation of an autophagic flux reporter sensitive to differential autophagy-inducing stressors. (A) Schematic representation of the autophagic flux reporter DsRed and GFP-tagged p62. p62 is selectively incorporated into and degraded along with the autophagosomal membrane. Therefore, the level of GFP-p62, relative to DsRed, is inversely proportional to autophagic flux. Examples of autophagy activation and inhibition were demonstrated using the histogram in the right panel. (B) HEK293A reporter cell line was treated with starvation in time- and concentration-dependent manners. WB was used to examine DsRed and GFP-p62 signals. FACS was employed to investigate GFP and DsRed fluorescence of the reporter cells treated with amino acid–free media (-AA) for 3 h. Histograms were used to depict changes in GFP-p62 and DsRed levels. (C) Reporter cell line was incubated with tunicamycin in time- and concentration-dependent manners. DsRed and GFP-p62 were analyzed using WB. FACS was used to examine GFP and DsRed signals of the reporter cells exposed to tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. Histograms were used to depict changes in GFP-p62 and DsRed levels. (D) Reporter cells were incubated with clofibrate in time- and concentration-dependent manners. DsRed and p62 levels were examined using WB. FACS was employed to investigate GFP and DsRed fluorescence of the reporter cells treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. Histograms were used to depict changes in GFP-p62 and DsRed levels. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

We next investigated the autophagic response to ER stress and peroxisomal stress. ER stress was induced by tunicamycin using established ranges and concentrations (Ohoka et al., 2005; Abdullahi et al., 2017). Tunicamycin hinders the first stage of N-linked glycan production in proteins and leads to the accumulation of improperly folded proteins. We found that tunicamycin (10 µg/ml, 6 h) robustly triggered autophagy-dependent p62 clearance via both WB (Fig. 1 C) and flow cytometry (GFP-p62 reduction, Fig. 1 C, right panel). To initiate peroxisomal stress, we treated cells with clofibrate in a time- and dose-dependent manner, finding that 1mM for 6 h induced the most robust and consistent reduction in p62 levels and GFP-p62 fluorescence without affecting DsRed (Fig. 1 D).

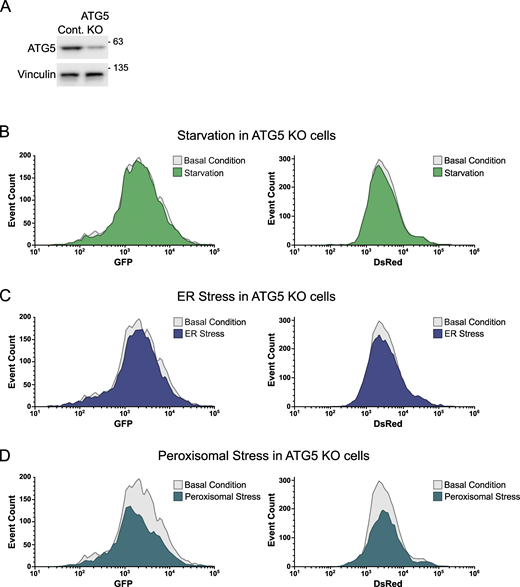

Collectively, these experiments establish that our reporter cell line gives a robust readout of both selective and bulk autophagy flux. Moreover, we established the time points that correspond to the first wave of p62 autophagic degradation in response to starvation, peroxisomal stress, and ER stress, which is important to minimize potential confounds of secondary or compensatory effects caused by prolonged exposure of these stimuli. All time points were within the dynamic range of the onset of p62 degradation and yielded comparable p62 clearance by flow cytometry, facilitating comparison of stress responses. Importantly, we confirmed that these responses were dependent on autophagy as they were lost in the absence of ATG5 (Fig. S1, A–D).

Analysis of autophagy flux in ATG5 KO cells. (A) ATG5 KO efficiency was examined by WB. (B–D) HEK293A reporter cells were transduced with viruses carrying sgRNA targeting ATG5. These cells were then treated with amino acid–free media for 3 h (B), tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h (C), or clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h (D). Next, they were examined using FACS. Histogram overlays compare either GFP or DsRed signals of the treated ATG5 KO reporter cells with those signals of the untreated ATG5 KO ones. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Analysis of autophagy flux in ATG5 KO cells. (A) ATG5 KO efficiency was examined by WB. (B–D) HEK293A reporter cells were transduced with viruses carrying sgRNA targeting ATG5. These cells were then treated with amino acid–free media for 3 h (B), tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h (C), or clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h (D). Next, they were examined using FACS. Histogram overlays compare either GFP or DsRed signals of the treated ATG5 KO reporter cells with those signals of the untreated ATG5 KO ones. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

CRISPR-based screens identify shared and distinct stress-selective autophagic pathways

To gain insight into differences in signaling that impact selective autophagic flux, we conducted kinome-wide CRISPR-based screens using the validated DsRed-IRES-GFP-p62 reporter line (Fig. 2 A). Briefly, cells were transduced with the Brunello kinome library, a pooled lentiCRISPRv2 library containing 3,052 unique sgRNAs targeting 763 human kinase genes (4 guides per target) at a multiplicity of infection of 0.3 to promote single virus integration (Doench et al., 2016). Infected cells were selected with puromycin for 3 days and expanded for 16 days, maintaining at least 1,000× representation. On day 16, cells were exposed to either amino acid–free media (3 h; starvation), tunicamycin (10 μg/ml, 6 h; ER stress), or clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h; peroxisomal stress), or left untreated (basal), and then fixed and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to compare stress responses from identical cell replicates. The top and bottom deciles of the GFP/DsRed ratio were sorted as autophagy activators and inhibitors, respectively (Fig. 2 A). Genomic DNA from sorted and presort populations was extracted, and sgRNAs were amplified and analyzed by next-generation sequencing. Each of the four conditions was screened in four independent experiments, totaling 16 kinome screens, and datasets were integrated to identify both shared and unique autophagy regulators (Fig. 2 A).

Tandem CRISPR screens identify stress-specific regulators of autophagy. (A) Screening strategy used to identify positive regulators and negative regulators of autophagy pathways. (B) Venn diagrams depict shared and distinct activators or inhibitors among four examined conditions. (C and D) Volcano plots from the four screens. For each gene, the x axis indicates its enrichment or depletion, determined by the mean of all four sgRNAs targeting the gene, in the sorted population compared with the corresponding unsorted population. The y axis represents the statistical significance, as indicated by the FDR-corrected P value. The horizontal dashed line represents an FDR-value threshold of 0.1. Red dots on the graph denote shared regulators across all four conditions, hits specific to different conditions are colored accordingly, and all other genes are represented as gray dots. (E) Gene ontology analysis was performed on screen candidates across the four examined conditions. The top 5 enriched Reactome pathways and corresponding –log10(P values) are shown.

Tandem CRISPR screens identify stress-specific regulators of autophagy. (A) Screening strategy used to identify positive regulators and negative regulators of autophagy pathways. (B) Venn diagrams depict shared and distinct activators or inhibitors among four examined conditions. (C and D) Volcano plots from the four screens. For each gene, the x axis indicates its enrichment or depletion, determined by the mean of all four sgRNAs targeting the gene, in the sorted population compared with the corresponding unsorted population. The y axis represents the statistical significance, as indicated by the FDR-corrected P value. The horizontal dashed line represents an FDR-value threshold of 0.1. Red dots on the graph denote shared regulators across all four conditions, hits specific to different conditions are colored accordingly, and all other genes are represented as gray dots. (E) Gene ontology analysis was performed on screen candidates across the four examined conditions. The top 5 enriched Reactome pathways and corresponding –log10(P values) are shown.

We conducted analysis of sgRNA enrichment and depletion between the sorted populations and the corresponding unsorted populations across experimental replicates for each stress condition using CRISPRBetaBinomial (Jeong et al., 2019). Hits were identified using a false discovery rate (FDR; adjusted P values) and positive log2 fold change (log2FC), where log2FC reflects gene enrichment or depletion in sorted high or low GFP/DsRed populations compared with unsorted controls, averaged across four sgRNAs per gene (Table 1 and Table S1). FDR indicates the statistical significance of sgRNA abundance in sorted versus unsorted samples. While some autophagy activators and inhibitors were shared across all conditions, many hits were unique to specific stressors (Fig. 2 B). Volcano plots of FDR and log2FC values were generated to visualize these regulators (Fig. 2, C and D). Due to greater statistical power for detecting sgRNA enrichment than depletion, subsequent analyses focused on genes with FDR <0.1 and positive log2FC, excluding hits with conflicting significance in both activator and inhibitor groups (Rousseaux et al., 2018). Table 1 summarizes common and distinct regulators, with previously known autophagy genes in plain text and novel screen-identified hits in italics.

Summary of hits that satisfy log2FC and FDR cutoffs

| Condition . | Hits . | |

|---|---|---|

| Basal condition | Activators | PIK3R4, PIK3C3, ULK1, PIKFYVE, MET, CDK1, SBK1, CSNK2A1, ADCK4, FGFRL1, INSR, PRKCG, TGFBR2, AATK, RIPK4, PHKA2, SEPHS2, CDK5R1, MAPK1, STK32A, FLT1, GK2, IP6K3, ITPKC, LATS1, CKMT1B, BCKDK, TPK1, PDGFRL, PHKG1, BCR, ERN2, NTRK1 |

| Inhibitors | MAP4K2, TKFC, MARK2, CDC42BPG, CHKA, PKMYT1, PGK1, ABCC1, NEK1, AGK, EXOSC10, RPS6KL1, TPR | |

| Starvation | Activators | PIK3R4, ULK1, PIK3C3, PIKFYVE, PHKG1, ROS1, INSRR, LATS1, CSNK1A1L, PLK1, CSNK2A2, ACVR2B, CPNE3 |

| Inhibitors | MAP4K2, TKFC, RPS6KL1, CAMKK1, ROCK1, CDC42BPG, NEK1, CDC42BPB, CLP1, NEK9, PRKAG2, RPS6KA4, MAP3K11, PFKFB2, VRK1, BTK, MASTL, PRKAB1, PRKD1, ITPK1, NME1-NME2, ACVR1, CDK12, PMVK, MAPK3, UCK1, RIPK3, MOK, RPS6KC1, MAP2K2, HUNK, PKDCC, PRKAR2A | |

| ER stress | Activators | PIK3C3, PIKFYVE, ULK1, PIK3R4, ATMIN, CDK11A, ADCK3, PRKD2, STRADA, PAK4, CDK14, CSNK2A2, GK2, PHKA2, TESK1, TRIM27, GSG2, ROR1, CDC42BPB, FGFRL1, MVK, TK1, TRIO, EIF2AK3, RIOK3 |

| Inhibitors | TKFC, MAP4K2, PMVK, RPS6KA4, NME3, SCYL1, CHEK2, STK11, AMHR2, BRD3, CLK3, CSNK2B, MST1, PGM2L1, SBK3, TSSK4, TTBK2 | |

| Peroxisome stress | Activators | PIK3C3, PIK3R4, ULK1, PIKFYVE, CSNK2A2, BMP2K, PAN3, PIP5KL1, TGFBR1, IDNK, ADPGK, SBK2, CLK3, CERKL |

| Inhibitors | TKFC, MAP4K2, CDC42BPG, PDPK1, KIAA1804, MAP3K11, LMTK2, RPS6KA4, SRC, PFKFB4, BAZ1B, MAPK15, MTOR, STK11, ACVR1, MST1, CDK2 | |

| Condition . | Hits . | |

|---|---|---|

| Basal condition | Activators | PIK3R4, PIK3C3, ULK1, PIKFYVE, MET, CDK1, SBK1, CSNK2A1, ADCK4, FGFRL1, INSR, PRKCG, TGFBR2, AATK, RIPK4, PHKA2, SEPHS2, CDK5R1, MAPK1, STK32A, FLT1, GK2, IP6K3, ITPKC, LATS1, CKMT1B, BCKDK, TPK1, PDGFRL, PHKG1, BCR, ERN2, NTRK1 |

| Inhibitors | MAP4K2, TKFC, MARK2, CDC42BPG, CHKA, PKMYT1, PGK1, ABCC1, NEK1, AGK, EXOSC10, RPS6KL1, TPR | |

| Starvation | Activators | PIK3R4, ULK1, PIK3C3, PIKFYVE, PHKG1, ROS1, INSRR, LATS1, CSNK1A1L, PLK1, CSNK2A2, ACVR2B, CPNE3 |

| Inhibitors | MAP4K2, TKFC, RPS6KL1, CAMKK1, ROCK1, CDC42BPG, NEK1, CDC42BPB, CLP1, NEK9, PRKAG2, RPS6KA4, MAP3K11, PFKFB2, VRK1, BTK, MASTL, PRKAB1, PRKD1, ITPK1, NME1-NME2, ACVR1, CDK12, PMVK, MAPK3, UCK1, RIPK3, MOK, RPS6KC1, MAP2K2, HUNK, PKDCC, PRKAR2A | |

| ER stress | Activators | PIK3C3, PIKFYVE, ULK1, PIK3R4, ATMIN, CDK11A, ADCK3, PRKD2, STRADA, PAK4, CDK14, CSNK2A2, GK2, PHKA2, TESK1, TRIM27, GSG2, ROR1, CDC42BPB, FGFRL1, MVK, TK1, TRIO, EIF2AK3, RIOK3 |

| Inhibitors | TKFC, MAP4K2, PMVK, RPS6KA4, NME3, SCYL1, CHEK2, STK11, AMHR2, BRD3, CLK3, CSNK2B, MST1, PGM2L1, SBK3, TSSK4, TTBK2 | |

| Peroxisome stress | Activators | PIK3C3, PIK3R4, ULK1, PIKFYVE, CSNK2A2, BMP2K, PAN3, PIP5KL1, TGFBR1, IDNK, ADPGK, SBK2, CLK3, CERKL |

| Inhibitors | TKFC, MAP4K2, CDC42BPG, PDPK1, KIAA1804, MAP3K11, LMTK2, RPS6KA4, SRC, PFKFB4, BAZ1B, MAPK15, MTOR, STK11, ACVR1, MST1, CDK2 | |

Known hits are displayed in normal texts, and novel hits are shown in italic texts.

Gene ontology analysis with PANTHER assessed candidate kinase enrichment in signaling pathways (Fig. 2 E and Table S2). We found that basal autophagy candidates were significantly enriched in metabolism and insulin receptor signaling pathways, whereas candidates involved in stress-induced autophagy were enriched in pathways such as autophagy and mitophagy. This analysis also identified synthesis of PIPs at the late endosomal membrane as a shared pathway among all four screen conditions. Notably, our gene ontology identified autophagy and autophagy-related pathway enrichment, which is consistent with an autophagy-regulating role of these kinases.

Autophagy activators

Our kinome screens identified a total of 66 autophagy activators that met the selection criteria above. Notably, the autophagy activators that were found in all four conditions have all previously been linked to autophagy activation, reinforcing the quality of our screen results. The common activators were ULK1, PIK3C3, PIK3R4, and PIKFYVE (Fig. 2 C). The protein kinase ULK1 along with the lipid kinase containing PIK3R4 and PIK3C3 is an important factor in core autophagy machinery and has been well characterized to tightly regulate autophagy initiation. The role of PIKFYVE in autophagy has been characterized more recently, and was reported to be important for lysosomal function in the autophagy pathway, which is a common requirement for bulk and selective autophagy (Hasegawa et al., 2022).

We also found multiple genes encoding members of the casein kinase family (CSNK) among the four autophagy screens. Several reports have demonstrated both activating and inhibiting roles of this family in autophagy regulation, with the role varying based on the cell type and stress condition tested (Li et al., 2020; Chino et al., 2022; Hoenigsperger et al., 2024; Carrino et al., 2019; Cheong et al., 2015). In our analysis, we found CSNK2A1 was involved in autophagy activation under basal conditions, while CSNK1A1L and CSNK2A2 were implicated in activating starvation-induced autophagy. CSNK2A2 was also associated with autophagy activation under ER stress and peroxisomal stress (Table 1).

Autophagy inhibitors

We identified a total of 63 shared and distinct autophagy inhibitors across the four screens. We found that TKFC and MAP4K2 are shared autophagy inhibitors among all conditions (Fig. 2 D and Table 1). Triokinase/flavin mononucleotide (FMN) cyclase (TKFC) is an enzyme involved in cellular processes related to the metabolism of carbohydrates and FMN, which is a type of flavin coenzyme (Rodrigues et al., 2019). There is no known link between TKFC and autophagy to date. MAP4K2, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 2, is a serine/threonine kinase essential for innate immune responses and cell signaling (Chuang et al., 2016). Little is known about the relationship between MAP4K2 and autophagy. However, MAP4K2 has been recently reported to induce autophagy upon energy stress through LC3 phosphorylation (Seo et al., 2023). MAP4K2 inclusion in all four investigated conditions underscores its role as a general inhibitor of autophagy.

Our screens also identified genes encoding members of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (RPS6K) family across four tested conditions. Like casein kinases, various reports have indicated that this family plays both activating and inhibitory roles in the regulation of autophagy (Hać et al., 2021; Blommaart et al., 1995; Scott et al., 2004; Armour et al., 2009; Zeng and Kinsella, 2008). In our study, we observed RPS6K in the negative autophagy regulator screens. Specifically, RPS6KL1 was identified in the basal condition. RPS6KA4, RPS6KC1, and RPS6KL1 were enriched in starvation-induced autophagy conditions. Finally, RPS6KA4 was enriched in both ER stress– and peroxisomal stress–induced autophagy.

Collectively, our comprehensive kinome screens have identified a total of 129 kinases with a significant FDR and positive log2FC values. In addition to the common activators and inhibitors of all conditions, we also found several kinases that overlapped between two or more conditions, which may imply common upstream regulation between these types of autophagy. There is a precedent for this type of overlap in selective autophagy regulators from the study of autophagy receptors. For example, BNIP3L has been reported to induce pexophagy and mitophagy (Wilhelm et al., 2022). These results reinforce the hypothesis that in addition to autophagy receptors, signal transduction directs and coordinates organelle-specific autophagy initiation.

Selection of top hits for characterization

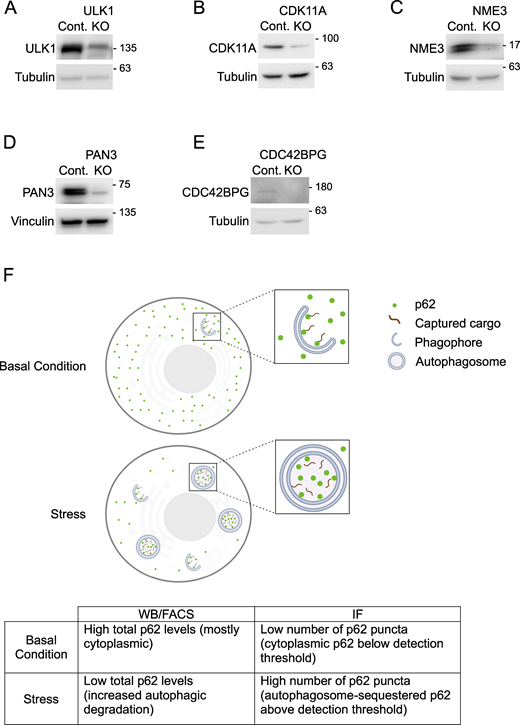

To validate hits that were potential unique regulators of selective autophagy, we generated polyclonal knockout (KO) cell lines using CRISPR/Cas9 for the top activators or inhibitors for both ER stress– and peroxisomal stress–induced autophagy and validated them using WB as an orthogonal system. An additional ULK1-positive control, which was shared among all conditions, was also generated in the same manner. We evaluated p62 flux via WB following the same treatment paradigms used in the screens (Fig. S2, A and B; and Fig. S3, A and B). From this experiment, we chose the top hits for each category (ER-phagy/pexophagy activator/inhibitor), which showed the largest average regulatory effect and had not previously been implicated in regulation of the corresponding selective autophagy pathway. These hits were cyclin-dependent kinase 11A (CDK11A; ER-phagy activator), NME1 (ER-phagy repressor), PAN3 (pexophagy activator), and CDC42BPG (pexophagy inhibitor); KO efficiencies of these cell lines were confirmed by WB (Fig. S4, A–E). We employed multiple methods to investigate p62 regulation during autophagy. WB and FACS reveal reduced total p62 levels upon autophagy activation, while immunofluorescence (IF) shows increased p62 puncta due to its localization in autophagosomes under stress (Fig. S4 F) (Klionsky et al., 2016). As a result of these differences in detection methods, decreased total p62 by WB and FACS and increased p62 puncta by IF are both consistent with increases in autophagy flux.

Validation of candidates associated with ER stress–induced autophagy. (A and B) Wild-type HEK293A cells were infected with both lentiviruses harboring both Cas9 and sgRNA targeting indicated positive (A) or negative (B) regulators. Polyclonal KO cells were then incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. Autophagy flux was examined through blots of p62. Experiments were repeated six times. P values denote statistical significance of treated KO cells compared with treated control cells and were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Validation of candidates associated with ER stress–induced autophagy. (A and B) Wild-type HEK293A cells were infected with both lentiviruses harboring both Cas9 and sgRNA targeting indicated positive (A) or negative (B) regulators. Polyclonal KO cells were then incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. Autophagy flux was examined through blots of p62. Experiments were repeated six times. P values denote statistical significance of treated KO cells compared with treated control cells and were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Validation of candidates associated with peroxisomal stress–induced autophagy. (A and B) Wild-type HEK293A cells were infected with both lentiviruses harboring both Cas9 and sgRNA targeting indicated positive (A) or negative (B) regulators. Polyclonal KO cells were then incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. Autophagy flux was examined through blots of p62. Experiments were repeated six times. P values denote statistical significance of treated KO cells compared with treated control cells and were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Validation of candidates associated with peroxisomal stress–induced autophagy. (A and B) Wild-type HEK293A cells were infected with both lentiviruses harboring both Cas9 and sgRNA targeting indicated positive (A) or negative (B) regulators. Polyclonal KO cells were then incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. Autophagy flux was examined through blots of p62. Experiments were repeated six times. P values denote statistical significance of treated KO cells compared with treated control cells and were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Depletion efficiency of KO cells. (A–E). Whole-cell lysates of polyclonal KO cells were immunoblotted for the levels of depleted proteins using the antibodies indicated. (F) Diagram and table illustrating p62 patterns detected through WB, IF, or FACS approaches. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Depletion efficiency of KO cells. (A–E). Whole-cell lysates of polyclonal KO cells were immunoblotted for the levels of depleted proteins using the antibodies indicated. (F) Diagram and table illustrating p62 patterns detected through WB, IF, or FACS approaches. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

CDK11A is a selective ER-phagy activator

Our analysis suggested that CDK11A may be a novel activator of ER-phagy (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S2 A). CDK11A, a member of the cyclin-dependent kinase family, is implicated in the regulation of transcription, cell cycle control, and basal autophagy regulation (Trembley et al., 2002; Loyer et al., 2005; Wilkinson et al., 2011). However, it has no known role in selective autophagy or ER-phagy. We treated control 293A and CDK11A KO cells with tunicamycin, and observed a decrease of p62 in control cells, but not in CDK11A KO cells (Fig. 3 B). Moreover, we observed an increase in basal p62 in CDK11A KO cells, which is expected when an activator of autophagy is ablated (Fig. 3 B) (Jung et al., 2009). In addition to p62, we assessed autophagy via LC3B signaling, where lipidated LC3B-II (detected as the lower band by WB) serves as a marker for autophagy flux (Klionsky et al., 2016). Elevated LC3B-II levels can indicate impaired autophagosome clearance, so measurements were performed with bafilomycin A1 (Baf) to block lysosomal degradation. In control, but not CDK11A KO, cells, we detected induction of autophagy by tunicamycin, as measured by LC3B-II accumulation in the presence of Baf (Fig. 3 B). CHOP levels, a marker of the unfolded protein response (UPR), increased equally in both control and KO lines, ruling out UPR dysregulation as a cause of impaired p62 degradation (Fig. 3 B) (Lei et al., 2017).

CDK11A activates ER-phagy. (A) CDK11A is represented as a prominent blue dot on the volcano plot. Red dots on the graph denote common regulators across all four conditions. (B) Control and CDK11A KO HEK293A cells were treated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Levels of p62 and LC3B were analyzed using WB. The effectiveness of tunicamycin was assessed through CHOP analysis. (C) Control and KO cells were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h p62 and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (D) Control and KO cells were treated with tunicamycin in the presence or absence of Baf. FAM134B levels were then examined using WB. (E) Indicated cells were incubated with tunicamycin for 6 h. FAM134B puncta were quantified by IF. (F) Control and KO cells were incubated with tunicamycin for 6 h. FAM134B and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. White arrows depict LC3B and FAM134B colocalization. Scale bars, 10 µM. Scale bars for the magnification images, 2.5 µM. (G) Control and CDK11A KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL reporter were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. ER-phagy was assessed through the processing of ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL. (H) Control and CDK11A KD cells containing ER-phagy reporter KDEL were treated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. GFP, RFP, and p62 signals were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (I) Control and KO HEK293A cells were incubated with either acute amino acid starvation (1.5 h, -AAa) or tunicamycin (10 µg/ml, 6 h). Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using the antibodies indicated. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

CDK11A activates ER-phagy. (A) CDK11A is represented as a prominent blue dot on the volcano plot. Red dots on the graph denote common regulators across all four conditions. (B) Control and CDK11A KO HEK293A cells were treated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Levels of p62 and LC3B were analyzed using WB. The effectiveness of tunicamycin was assessed through CHOP analysis. (C) Control and KO cells were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h p62 and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (D) Control and KO cells were treated with tunicamycin in the presence or absence of Baf. FAM134B levels were then examined using WB. (E) Indicated cells were incubated with tunicamycin for 6 h. FAM134B puncta were quantified by IF. (F) Control and KO cells were incubated with tunicamycin for 6 h. FAM134B and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. White arrows depict LC3B and FAM134B colocalization. Scale bars, 10 µM. Scale bars for the magnification images, 2.5 µM. (G) Control and CDK11A KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL reporter were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. ER-phagy was assessed through the processing of ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL. (H) Control and CDK11A KD cells containing ER-phagy reporter KDEL were treated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. GFP, RFP, and p62 signals were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (I) Control and KO HEK293A cells were incubated with either acute amino acid starvation (1.5 h, -AAa) or tunicamycin (10 µg/ml, 6 h). Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using the antibodies indicated. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

p62 directly interacts with LC3B when loading cargo into autophagosomes. Thus, we used IF microscopy to measure the impact of CDK11A KO on the formation of p62- and LC3B-positive autophagosomes during ER stress. In response to ER stress, control cells showed an increase in p62 and LC3B (lipidated LC3B) dual-positive puncta (Fig. 3 C). In CDK11A KO cells, we observed a slightly lower induction of LC3B puncta that were not p62-positive, indicating a defect in p62 recruitment and cargo loading in response to ER stress (Fig. 3 C).

To better link CDK11A function to ER-phagy induction, we sought to analyze the ER-resident autophagy receptor FAM134B. FAM134B is the best-characterized ER-phagy receptor, which, like p62, binds LC3B-II and is degraded in the autophagosome (Khaminets et al., 2015; Leonibus et al., 2020). We treated control and CDK11A KO cells with tunicamycin in the presence of Baf and analyzed FAM134B levels (Fig. 3 D). As anticipated, in control cells, FAM134B was degraded in response to ER stress, which was blocked by Baf treatment. However, in CDK11A KO cells we observed that FAM134B was insensitive to both ER stress and inhibitors of autophagy, further indicating that CDK11A is important for ER-phagy (Fig. 3 D). To confirm CDK11A regulates ER-phagy beyond the HEK293A background, CDK11A was knocked down in HCT116 cells (Fig. S5 A). Like HEK293A cells, CDK11A depletion impaired FAM134B degradation upon tunicamycin (Fig. S5 B).

Validation of CDK11A role in ER-phagy regulation using the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL approach. (A) CDK11A KD efficiency was examined by WB. (B) Control and CDK11A KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL reporter were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. FAM134B levels were then examined using WB. (C and D) Control and KD ER-phagy reporter cells were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) or prolonged amino acid starvation (-AAp) for 6 h. The processing of ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL was analyzed by WB (C) or visualized by IF (D). Scale bars, 10 µM. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS5.

Validation of CDK11A role in ER-phagy regulation using the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL approach. (A) CDK11A KD efficiency was examined by WB. (B) Control and CDK11A KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL reporter were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. FAM134B levels were then examined using WB. (C and D) Control and KD ER-phagy reporter cells were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) or prolonged amino acid starvation (-AAp) for 6 h. The processing of ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL was analyzed by WB (C) or visualized by IF (D). Scale bars, 10 µM. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS5.

We next immunostained for FAM134B to determine whether FAM134B loading into autophagosomes upon ER stress requires CDK11A. Interestingly, we observed that FAM134B puncta were elevated in both tunicamycin-treated control and CDK11A KO cells (Fig. 3 E). FAM134B interacts with LC3B through LIR motifs, which guides the sequestration and engulfment of ER fragments within autophagosomes (Khaminets et al., 2015). To distinguish whether FAM134B puncta were associated with functional autophagosomes, we repeated the experiment while costaining for LC3B. As expected, control cells showed an induction of LC3B-associated FAM134B puncta under ER stress conditions, indicating an activation of ER-phagy (Fig. 3 F). However, in CDK11A-deficient conditions, we could not detect colocalization between FAM134B and LC3B puncta, indicating stalled autophagic structures (Fig. 3 F). This is consistent with our WB analysis (Fig. 3 D) and previous reports of stalled autophagic structures in autophagy-deficient cells (Jung et al., 2009; Komatsu et al., 2005; Zachari et al., 2020). Interestingly, ER stress induced LC3-negative FAM134B puncta in CDK11A KO cells (Fig. 3 F), indicating CDK11A regulates ER-phagy after FAM134B oligomerization, but before LC3B binding.

To further verify the role of CDK11A in ER-phagy across cell lines, a HCT116 line expressing doxycycline (Dox)-inducible ER-phagy reporter (ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL) was generated (Chino et al., 2019). Following Dox treatment and the induction of ER-phagy, the GFP signal is quenched due to its sensitivity to lysosomal proteases and pH, yielding an RFP fragment detectable by WB and IF. CDK11A knockdown (KD) in these cells (validated by WB; Fig. S5 A) abolished tunicamycin-induced free RFP fragment production, which was reversible with Baf in controls (Fig. 3 G). Additionally, IF revealed an increase in RFP single-positive puncta, which colocalized with p62, indicative of ER-phagy induction in tunicamycin-treated control cells, but no such processing occurred in CDK11A KD cells (Fig. 3 H). These results, consistent with WB data, confirm the essential role of CDK11A in ER-phagy across cellular contexts.

We next explored whether the requirement for CDK11A for ER-phagy is limited to ER stress induced by tunicamycin or extended to other inducers of ER-phagy. Prolonged amino acid starvation (6 h) is known to strongly induce ER-phagy, whereas bulk autophagy is typically triggered within a shorter timeframe (1–3 h). Using our ER-phagy reporter cell line, we induced ER-phagy by amino acid starvation for 6 h or tunicamycin treatment and observed ER-phagy induction under both stresses in our control line (Fig. S5, C and D). We found that the KD of CDK11A abrogated ER-phagy induction stimulated by prolonged amino acid starvation or tunicamycin treatment (Fig. S5, C and D). Collectively, these data indicate that CDK11A is essential for the induction of ER-phagy in response to diverse ER stressors.

To determine whether CDK11A acts selectively on ER-phagy, we tested how its loss of function affects starvation-induced autophagy. To make this head-to-head comparison, we incubated control and CDK11A KO HEK293A cells with amino acid–free media or tunicamycin. Amino acid starvation begins to induce ER-phagy after 6 h, so a 1.5-h amino acid starvation was employed to induce bulk autophagy without activating ER-phagy. As expected, we observed an efficient induction of starvation-induced autophagy and ER-phagy in control cells as shown by the degradation of p62 and FAM134B, respectively (Fig. 3 I). We observed that CDK11A KO cells were competent in the induction of starvation-induced autophagy, but deficient for ER-phagy (Fig. 3 I). Collectively, these data nominate CDK11A as a selective activator of ER-phagy.

NME3 is a selective ER-phagy inhibitor

Nucleoside diphosphate (NDP) kinase 3 (NME3) is best known for its ability to regulate nucleotide metabolism and signaling (Boissan et al., 2018; Abu-Taha et al., 2017). Recent research indicates that NME3 serves two distinct functions, regulation of mitochondrial dynamics and NDP kinase activity, both of which are required to maintain cell viability under glucose starvation (Chen et al., 2019a). Additionally, during the preparation of this manuscript, NME3 was reported to be involved in mitophagy regulation (Chen et al., 2024). Our analysis of the top screen hits indicated that NME3 may be a selective repressor of ER-phagy (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S2 B). We first tested the ability of NME3 KO cells to increase autophagic flux upon ER stress. We found that NME3 KO cells showed enhanced autophagic flux during ER stress, with lower p62 levels and more complete p62 degradation compared with controls (Fig. 4 B). Tunicamycin-treated NME3 KO cells also exhibited a greater increase in LC3B-II in the presence of Baf, indicating NME3 inhibits ER stress–induced autophagy (Fig. 4 B). NME3 KO resulted in elevated p62 punctum formation and enhanced colocalization of p62 with LC3B during ER stress (Fig. 4 C). Additionally, NME3 depletion led to a more robust reduction in FAM134B levels compared with those of the control cells upon ER stress, and this degradation was blocked by Baf (Fig. 4 D), with similar effects seen in HCT116 cells (Fig. S6, A and B). We also observed that NME3 KO cells had an enhanced production of LC3B-positive FAM134B puncta compared with control cells upon ER stress (Fig. 4 E). Furthermore, NME3 KD showed a more pronounced increase in ER-phagy reporter probe processing, blocked by Baf (Fig. 4 F), and in RFP-positive p62 puncta upon tunicamycin treatment (Fig. 4 G). NME3 KD efficiency was also verified (Fig. S6 A). In addition to tunicamycin, prolonged starvation further increased ER-phagy markers in NME3 KD reporter cells using WB and IF, confirming that NME3-dependent regulation of ER-phagy could be triggered by various stimuli (Fig. S6, C and D). Finally, NME3 KO selectively enhanced p62 and FAM134B degradation during ER stress but not acute amino acid starvation (Fig. 4 H), demonstrating NME3 is a selective upstream inhibitor of ER-phagy.

NME3 inhibits ER-phagy. (A) NME3 is represented as a prominent blue dot on the volcano plot. Red dots on the graph denote common regulators across all four conditions. (B) Control and NME3 KO HEK293A cells were treated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Changes in p62 and LC3B levels were analyzed using WB. The effectiveness of tunicamycin was assessed through CHOP analysis. (C) Control and KO cells were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. p62 and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (D) Control and KO cells were treated with tunicamycin in the presence or absence of Baf. FAM134B signaling was then examined using WB. (E) Indicated cells were incubated with tunicamycin. FAM134B and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. White arrows depict LC3B and FAM134B colocalization. Scale bars, 10 µM. Scale bars for the magnification images, 2.5 µM. (F) Control and NME3 KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL reporter were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. ER-phagy was assessed through the processing of ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL. (G) Control and NME3 KD cells expressing ER-phagy reporter KDEL were treated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. GFP, RFP, and p62 signals were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (H) Control and KO HEK293A cells were incubated with either acute amino acid starvation (1.5 h, -AAa) or tunicamycin (10 µg/ml, 6 h). Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using the antibodies indicated. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

NME3 inhibits ER-phagy. (A) NME3 is represented as a prominent blue dot on the volcano plot. Red dots on the graph denote common regulators across all four conditions. (B) Control and NME3 KO HEK293A cells were treated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Changes in p62 and LC3B levels were analyzed using WB. The effectiveness of tunicamycin was assessed through CHOP analysis. (C) Control and KO cells were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. p62 and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (D) Control and KO cells were treated with tunicamycin in the presence or absence of Baf. FAM134B signaling was then examined using WB. (E) Indicated cells were incubated with tunicamycin. FAM134B and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. White arrows depict LC3B and FAM134B colocalization. Scale bars, 10 µM. Scale bars for the magnification images, 2.5 µM. (F) Control and NME3 KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL reporter were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. ER-phagy was assessed through the processing of ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL. (G) Control and NME3 KD cells expressing ER-phagy reporter KDEL were treated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h. GFP, RFP, and p62 signals were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (H) Control and KO HEK293A cells were incubated with either acute amino acid starvation (1.5 h, -AAa) or tunicamycin (10 µg/ml, 6 h). Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using the antibodies indicated. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Validation of NME3 role in ER-phagy regulation using the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL approach. (A) NME3 KD efficiency was examined by WB. (B) Control and NME3 KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL reporter were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. FAM134B levels were then examined using WB. (C and D) Control and KD ER-phagy reporter cells were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) or prolonged amino acid starvation (-AAp) for 6 h. The processing of ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL was analyzed by WB (C) or visualized by IF (D). Scale bars, 10 µM. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS6.

Validation of NME3 role in ER-phagy regulation using the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL approach. (A) NME3 KD efficiency was examined by WB. (B) Control and NME3 KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL reporter were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. FAM134B levels were then examined using WB. (C and D) Control and KD ER-phagy reporter cells were incubated with tunicamycin (10 µg/ml) or prolonged amino acid starvation (-AAp) for 6 h. The processing of ss-RFP-GFP-KDEL was analyzed by WB (C) or visualized by IF (D). Scale bars, 10 µM. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS6.

PAN3 is an activator of pexophagy

Our screen validation identified poly(A)-specific ribonuclease subunit 3 (PAN3) as a potential regulator of clofibrate-driven pexophagy (Fig. 5 A and Fig. S3 A). PAN3 plays a crucial role in mRNA degradation and regulation of gene expression in eukaryotic cells (Chen et al., 2017). It is a component of the PAN2-PAN3 de-adenylation complex responsible for shortening the poly(A) tail of mRNA molecules (Wolf and Passmore, 2014; Wolf et al., 2014). PAN3 has a PKc kinase domain but may be a pseudokinase and has no known targets (Wolf et al., 2014). To test whether PAN3 regulates peroxisomal stress–induced autophagy, control and PAN3 KO cells were treated with clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h). In control cells, clofibrate reduced p62 levels, an effect blocked by Baf, and increased LC3B-II, indicating autophagy induction (Fig. 5 B). In contrast, PAN3 KO cells failed to show p62 flux or LC3B-II accumulation under stress, suggesting impaired autophagy (Fig. 5 B). IF revealed increased LC3B-positive p62 puncta in clofibrate-treated control cells, but no change in PAN3 KO cells, which maintained low p62 puncta regardless of treatment (Fig. 5 C). These results demonstrate that PAN3 is essential for autophagic induction in response to peroxisomal damage.

PAN3 activates pexophagy. (A) PAN3 is represented as a prominent teal dot on the volcano plot. Red dots on the graph denote common regulators across all four conditions. (B) Control and PAN3 KO HEK293A cells were treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Changes in p62 and LC3B levels were analyzed using WB. (C) Control and KO cells were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. p62 and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (D) Control and KO cells were treated with clofibrate in the presence or absence of Baf. WB was then used to examine the pexophagy receptor, PMP70. (E) Indicated cells were incubated with clofibrate. PMP70 signal was visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (F) Control and PAN3 KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the RFP-GFP-SKL reporter were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Pexophagy was assessed through the processing of RFP-GFP-SKL. (G) Control and PAN3 KD cells expressing pexophagy reporter SKL were treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. GFP, RFP, and p62 signals were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 5 µM. (H) Control and KO HEK293A cells were incubated with either acute amino acid starvation (1.5 h, -AAa) or clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h). Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using the antibodies indicated. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

PAN3 activates pexophagy. (A) PAN3 is represented as a prominent teal dot on the volcano plot. Red dots on the graph denote common regulators across all four conditions. (B) Control and PAN3 KO HEK293A cells were treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Changes in p62 and LC3B levels were analyzed using WB. (C) Control and KO cells were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. p62 and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (D) Control and KO cells were treated with clofibrate in the presence or absence of Baf. WB was then used to examine the pexophagy receptor, PMP70. (E) Indicated cells were incubated with clofibrate. PMP70 signal was visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (F) Control and PAN3 KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the RFP-GFP-SKL reporter were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Pexophagy was assessed through the processing of RFP-GFP-SKL. (G) Control and PAN3 KD cells expressing pexophagy reporter SKL were treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. GFP, RFP, and p62 signals were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 5 µM. (H) Control and KO HEK293A cells were incubated with either acute amino acid starvation (1.5 h, -AAa) or clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h). Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using the antibodies indicated. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Next, to determine the impact of PAN3 on peroxisome turnover, we used an established peroxisomal marker, PMP70. Upon stress, PMP70 is ubiquitinated by peroxisomal E3 ubiquitin ligase PEX2 and promotes pexophagy, thus maintaining peroxisome quality (Sargent et al., 2016). Consistent with previous reports, we found that in control cells clofibrate caused a reduction in PMP70, blocked by Baf treatment, which indicates a reduction in peroxisomes through autophagy (Fig. 5 D) (Zhang et al., 2015). Interestingly, clofibrate-treated PAN3 KO cells showed elevated PMP70 levels compared with treated controls, suggesting defective pexophagy activation (Fig. 5 D). Similarly, PAN3 KD HCT116 cells (Fig. S7 A) blocked pexophagy, as detected by PMP70 analysis, confirming that the role of PAN3 in pexophagy is not cell line–specific (Fig. S7 B). Furthermore, PMP70 staining showed decreased peroxisome density in clofibrate-treated control cells, but no loss in PAN3 KO cells (Fig. 5 E), demonstrating PAN3 is required for peroxisome clearance upon clofibrate.

Validation of PAN3 role in pexophagy regulation using the RFP-GFP-SKL approach. (A) PAN3 KD efficiency was examined by WB. (B) Control and PAN3 KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the RFP-GFP-SKL reporter were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. PMP70 levels were then examined using WB. (C and D) Control and KD pexophagy reporter cells were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h) or Torin1 (Tor, 200 nM, 24 h). The processing of RFP-GFP-SKL was analyzed by WB (C) or visualized by IF (D). Scale bars, 5 µM. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS7.

Validation of PAN3 role in pexophagy regulation using the RFP-GFP-SKL approach. (A) PAN3 KD efficiency was examined by WB. (B) Control and PAN3 KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the RFP-GFP-SKL reporter were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. PMP70 levels were then examined using WB. (C and D) Control and KD pexophagy reporter cells were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h) or Torin1 (Tor, 200 nM, 24 h). The processing of RFP-GFP-SKL was analyzed by WB (C) or visualized by IF (D). Scale bars, 5 µM. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS7.

To further investigate the role of PAN3 in pexophagy, we developed an HCT116 cell line with the stable expression of a pexophagy reporter, consisting of the peroxisomal targeting sequence SKL and the fluorescent proteins RFP and GFP (RFP-GFP-SKL), as previously described (Zheng et al., 2021). We found that PAN3 KD blocked clofibrate-induced pexophagy probe processing by both WB and IF, while stressed control cells showed increased free RFP signals, blocked by autophagy inhibitors, and elevated RFP puncta (Fig. 5, F and G). Additionally, p62 puncta colocalized with the pexophagy probe in control but not PAN3 KD reporter cells upon clofibrate (Fig. 5 G).

We next examined whether PAN3-dependent regulation of pexophagy is specific to clofibrate or more broadly to other pexophagy inducers. Prolonged treatment of Torin1, an inhibitor of the mechanistic target of rapamycin, has been described to stimulate pexophagy and reduce PMP70 levels (Zheng et al., 2021). Using our pexophagy reporter cells, we treated with both clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h) and Torin1 (200 nM, 24 h) and observed an increase in RFP fragments detected by WB (Fig. S7 C) and GFP-free RFP density examined by IF (Fig. S7 D). This effect is lost in PAN3 KD cells (Fig. S7, C and D). Together, these experiments nominate PAN3 as an important activator of pexophagy induced by multiple stress conditions.

Lastly, we asked whether PAN3 specifically regulates pexophagy or is involved in bulk autophagy. In addition to clofibrate treatment, we incubated the control and PAN3 KO cells with the acute starvation medium protocol where pexophagy is not activated and PMP70 levels are not affected (Fig. 5 H). We then investigated the changes in p62 levels. While PAN3 KO cells exhibited a defect in clofibrate-stimulated pexophagy, they exhibited a normal induction of starvation-induced autophagy (Fig. 5 H). Taken together, these data demonstrate that PAN3 is a selective activator of pexophagy.

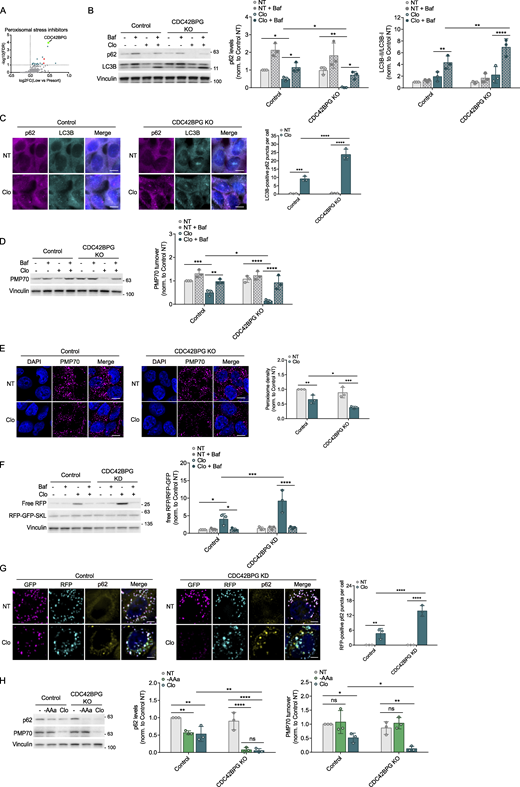

CDC42BPG is an inhibitor of pexophagy

CDC42-binding protein kinase gamma (CDC42BPG) is a serine/threonine protein kinase known to interact with the small GTPase CDC42 and is involved in cytoskeletal organization, cell division, and cell migration (Unbekandt and Olson, 2014). To date, CDC42BPG has not been linked to autophagy regulation or peroxisomes. Our kinome screen and subsequent analysis revealed involvement of CDC42BPG in the suppression of autophagy triggered by peroxisomal stress (Fig. 6 A and Fig. S3 B). Notably, CDC42BPG is the shared candidate inhibiting autophagy under basal condition, starvation, and peroxisomal stress. We decided to further validate CDC42BPG as it appears as a top novel hit displaying highly significant FDR and log2FC values, and its depletion showed the most robust response upon clofibrate treatment (Fig. S3 B). Treatment of CDC42BPG KO cells with clofibrate led to a greater reduction in p62 compared with control cells, and this effect was blocked by Baf, indicating that CDC42BPG inhibits peroxisomal stress–induced autophagy (Fig. 6 B). CDC42BPG KO cells also showed a more substantial increase in LC3B-II levels upon clofibrate (Fig. 6 B). Additionally, p62 levels under basal conditions were unchanged in both control and KO cells, suggesting that CDC42BPG is dispensable for basal autophagy (Fig. 6 B). IF revealed a more robust increase in LC3B-positive p62 puncta in clofibrate-treated CDC42BPG KO cells than in controls (Fig. 6 C). We next found that clofibrate-treated CDC42BPG KO and KD cells showed a more pronounced reduction in PMP70 levels, which was blocked by Baf, confirming autophagy-dependent regulation (Fig. 6 D; and Fig. S8, A and B). Furthermore, IF showed more robust peroxisome clearance in KO cells (Fig. 6 E). In pexophagy reporter lines, CDC42BPG KD showed a more pronounced increase in pexophagy reporter probe processing, blocked by Baf (Fig. 6 F), and in RFP-positive p62 puncta upon clofibrate (Fig. 6 G). CDC42BPG KD efficiency was confirmed (Fig. S8 A). In addition to clofibrate, CDC42BPG KD cells also showed increased pexophagy with Torin1, indicating that CDC42BPG is a negative regulator of pexophagy triggered by diverse stressors (Fig. S8, C and D). Finally, CDC42BPG KO cells displayed greater p62 degradation under both clofibrate and acute starvation (Fig. 6 H). This was expected as CDC42BPG also appeared as a negative regulator in the starvation condition. In summary, our findings suggest that CDC42BPG is capable of inhibiting autophagy, with its most robust inhibition impacting pexophagy.

CDC42BPG inhibits pexophagy. (A) CDC42BPG is represented as a prominent teal dot on the volcano plot. Red dots on the graph denote common regulators across all four conditions. (B) Control and CDC42BPG KO HEK293A cells were treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Changes in p62 and LC3B levels were analyzed using WB. (C) Control and KO cells were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. p62 and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (D) Control and KO cells were treated with clofibrate in the presence or absence of Baf. WB was then used to examine the pexophagy receptor, PMP70. (E) Indicated cells were incubated with clofibrate. PMP70 signal was visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (F) Control and CDC42BPG KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the RFP-GFP-SKL reporter were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Pexophagy was assessed through the processing of RFP-GFP-SKL. (G) Control and CDC42BPG KD cells expressing pexophagy reporter SKL were treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. GFP, RFP, and p62 signals were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 5 µM. (H) Control and KO HEK293A cells were incubated with either acute amino acid starvation (1.5 h, -AAa) or clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h). Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using the antibodies indicated. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

CDC42BPG inhibits pexophagy. (A) CDC42BPG is represented as a prominent teal dot on the volcano plot. Red dots on the graph denote common regulators across all four conditions. (B) Control and CDC42BPG KO HEK293A cells were treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Changes in p62 and LC3B levels were analyzed using WB. (C) Control and KO cells were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. p62 and LC3B puncta were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (D) Control and KO cells were treated with clofibrate in the presence or absence of Baf. WB was then used to examine the pexophagy receptor, PMP70. (E) Indicated cells were incubated with clofibrate. PMP70 signal was visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 10 µM. (F) Control and CDC42BPG KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the RFP-GFP-SKL reporter were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. Pexophagy was assessed through the processing of RFP-GFP-SKL. (G) Control and CDC42BPG KD cells expressing pexophagy reporter SKL were treated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h. GFP, RFP, and p62 signals were visualized and quantified by IF. Scale bars, 5 µM. (H) Control and KO HEK293A cells were incubated with either acute amino acid starvation (1.5 h, -AAa) or clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h). Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using the antibodies indicated. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Validation of CDC42BPG role in pexophagy regulation using the RFP-GFP-SKL approach. (A) CDC42BPG KD efficiency was examined by WB. (B) Control and CDC42BPG KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the RFP-GFP-SKL reporter were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. PMP70 levels were then examined using WB. (C and D) Control and KD pexophagy reporter cells were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h) or Torin1 (Tor, 200 nM, 24 h). The processing of RFP-GFP-SKL was analyzed by WB (C) or visualized by IF (D). Scale bars, 5 µM. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS8.

Validation of CDC42BPG role in pexophagy regulation using the RFP-GFP-SKL approach. (A) CDC42BPG KD efficiency was examined by WB. (B) Control and CDC42BPG KD HCT116 cells stably expressing the RFP-GFP-SKL reporter were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of Baf. PMP70 levels were then examined using WB. (C and D) Control and KD pexophagy reporter cells were incubated with clofibrate (1 mM, 6 h) or Torin1 (Tor, 200 nM, 24 h). The processing of RFP-GFP-SKL was analyzed by WB (C) or visualized by IF (D). Scale bars, 5 µM. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as means ± SDs, and P values were determined by two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.1; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS8.

Discussion

In this study, we used pooled CRISPR screens to systematically identify activators and inhibitors of autophagy under basal, starvation, ER stress, and peroxisomal stress conditions. Some of these regulators were common to selective and bulk autophagy and have been previously linked to autophagy. These include PIK3C3 (VPS34), PIKFYVE, PIK3R4 (VPS15), and ULK1. In addition, we identified shared autophagy inhibitors that are not currently described to suppress autophagy including MAP4K2 and TKFC. TKFC is a member of the dihydroxyacetone kinase family, which is best described to phosphorylate glyceraldehyde to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (Rodrigues et al., 2014). It will be interesting to determine whether the metabolic impacts of TKFC KO are responsible for autophagy activation, or whether the autophagy regulation is through an alternate function of TKFC. Notably, TKFC phosphorylation of glyceraldehyde is utilized in the metabolism of fructose, which is not present in our culture media, highlighting the possibility of an alternate mechanism of regulation (Rodrigues et al., 2014). Interestingly, MAP4K2 came up as an inhibitor in our screen, but has been described in one study as an autophagy activator (Seo et al., 2023). However, there were notable differences in the studies, which might explain the differences between our observations. For example, MAP4K2 activated autophagy under 20-h glucose starvation, while we identified MAP4K2 as an autophagy inhibitor under 3-h amino acid starvation. Chronological dissection of nutrient deprivation will help tease out its potential dual role in autophagy regulation. It will also be interesting to test whether MAPK4K2-linked inhibition is mediated by its kinase activity toward LC3, which may be functionally impacted by competing or proximal phosphorylation by PKA or PKCλ (Cherra et al., 2010). These open questions raised from the hits described above indicate that further characterization of our hits for regulators of bulk autophagy may also provide insight into basal and starvation-induced autophagy. While not the focus of our screens, we identified 25 potential novel regulators of starvation-induced autophagy, and 29 potential novel regulators of basal autophagy.

In response to ER stress, our screen identified an enrichment of 25 kinases linked to autophagy activation and 17 with inhibition. To validate the specificity of these regulators we characterized CDK11A and NME3 as selective regulators of ER-phagy. Specifically, we found CDK11A was a selective activator of ER-phagy and not required for starvation-induced autophagy. CDK11 has established role in control of RNA splicing, transcription, and the cell cycle control. In humans, CDK11 is encoded by two highly identical genes, CDC2L1 (also referred to as CDK11B) and CDC2L2 (also known as CDK11A) (Zhou et al., 2016). Interestingly, dual siRNA-mediated KD of CDK11A and CDK11B has previously been linked to an acute activation of basal autophagy, followed by an inhibition of autophagy at a later time point (Wilkinson et al., 2011). However, the mechanism of regulation remains unknown. In our study, disruption of CDK11A was sufficient to significantly impair ER-phagy induction, without any detectible enrichment in basal or starvation conditions. However, it remains to be seen whether a dual KO of CDK11A and CDK11B would impact basal autophagy, or whether the basal autophagy phenotype previously observed may involve a defect in ER homeostasis. CDK11A and CDK11B are activated in multiple cancer types and have been linked to acquisition of oncogenic properties, including proliferation. This newly described function of CDK11A in ER-phagy begs the question of whether ER stress dysregulation may be integral to these oncogenic properties.

We found that NME3 is a selective repressor of ER-phagy. NME3 belongs to a more conserved group of nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) family, which regulates cellular nucleotide homeostasis and is associated with GTP-dependent cellular processes (Schlattner, 2021). However, independent of its NDPK activity, NME3 has been described to regulate mitochondrial dynamics (Chen et al., 2019a). Both NDPK and mitochondrial functions are important for cellular survival under glucose starvation (Chen et al., 2019a). Moreover, it has been recently reported that NME3 is important for mitophagy induction (Chen et al., 2024). It will be interesting in future studies to determine whether NME3-mediated repression of ER-phagy is linked to its involvement in mitophagy and to elucidate the mechanisms by which NME3 performs conflicting roles in selective autophagy. An inactivating autosomal recessive mutation NME3 was found in a case study of a rare consanguineous fatal neurodegenerative disorder (Chen et al., 2019a). While homozygous inactivating mutations are lethal early in life, the impact of heterozygous inactivation of NME3 on ER-phagy and any potential physiological consequences is an interesting area for investigation.

In response to peroxisomal stress, we identified an enrichment of 14 autophagy activators and 17 inhibitors. To validate the specificity of these regulators, we chose to characterize the activator PAN3 and inhibitor CDC42BPG. PAN3 is a component of the PAN2-PAN3 complex, which modulates mRNA stability or translational efficiency and has not been implicated in autophagy (Wolf et al., 2014). Additional work is required to determine whether PAN3 regulates the gene expression of pexophagy promoters, or whether its promotion of peroxisomal autophagy is mediated by an alternate mechanism. CDC42BPG is a less well-characterized member of the myotonic dystrophy–related Cdc42-binding kinases, which play an important role in actin–myosin regulation and other functions such as cell invasion, motility, and adhesion (Unbekandt and Olson, 2014). While neither of these genes linked to disease, the mechanisms of peroxisomal disorders such as Zellweger’s disease have not been fully elucidated and exhibit dysregulation of pexophagy. Therefore, it would be interesting to test the involvement of hits from our pexophagy screen, including these proteins in cases which do not have reported Zellweger-associated PEX mutations.

Beyond detailed analysis of these top hits, our gene ontology analysis revealed candidates unique to ER stress that were significantly enriched in RhoJ and RhoG GTPase cycle pathways (Table S2). While Rho GTPases have been implicated in mitophagy regulation, their potential role in ER-phagy remains an open avenue for future research (Safiulina et al., 2019). In addition, analysis of candidates’ unique peroxisomal stress was enriched in TP53 expression and degradation pathways. The transcription factor TP53 has been shown to promote the expression of genes involved in peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation (Zhao et al., 2023). It will be interesting to determine whether this is an underlying mechanism through which the TP53 pathway could regulate pexophagy.

Together, these screens have identified a heretofore underappreciated role of signal transduction pathways in the regulation of the selective autophagic pathway. This resource thus provides a host of putative regulators, paving the way for tighter, selective control of different forms of autophagy and potential therapeutic inroads to target these pathways in clinically relevant scenarios.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents