Two protocadherins, Dachsous and Fat, regulate organ growth in Drosophila via the Hippo pathway. Dachsous and Fat bind heterotypically to regulate the abundance and subcellular localization of a “core complex” consisting of Dachs, Dlish, and Approximated. This complex localizes to the junctional cortex where it represses Warts. Dachsous is believed to promote growth by recruiting and stabilizing this complex, while Fat represses growth by promoting its degradation. Here, we examine the functional relationships between the intracellular domains of Dachsous and Fat and the core complex. While Dachsous promotes the accumulation of core complex proteins in puncta, it is not required for their assembly. Indeed, the core complex accumulates maximally in the absence of both Dachsous and Fat. Furthermore, Dachsous represses growth in the absence of Fat by removing the core complex from the junctional cortex. Fat similarly recruits core complex components but promotes their degradation. Our findings reveal that Dachsous and Fat coordinately constrain tissue growth by repressing the core complex.

Introduction

The ability to precisely control the subcellular localization of proteins, particularly at the cell cortex, is critical to the function of diverse intra- and intercellular signaling pathways. This property is well demonstrated by the Hippo pathway, which controls organ growth during development (Zheng and Pan, 2019; Karaman and Halder, 2018; Boggiano and Fehon, 2012). Hippo pathway kinases, including Tao, Hippo, and Warts (Wts), function in a cascade to promote phosphorylation of the transcriptional cofactor Yorkie (Yki), resulting in Yki repression and decreased transcription of its pathway targets. While the kinases are normally diffusely cytoplasmic, previous studies have revealed that their assembly and activity are controlled by cortically localized protein complexes (Boggiano and Fehon, 2012; Karaman and Halder, 2018). Expanded, a FERM-domain protein, associates with the transmembrane protein Crumbs at the junctional cortex to assemble and activate the core kinases (Ling et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2010). In parallel, Merlin (another FERM domain protein) and Kibra together assemble the same kinases at the apical medial cortex (Su et al., 2017).

Perhaps the most enigmatic cortically localized protein complex controlling Hippo pathway output is the Dachsous (Ds)–Fat (Ft) system (Cho et al., 2006; Willecke et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2006; Bennett and Harvey, 2006). Ds and Ft are giant protocadherins that regulate planar cell polarity, proximo-distal patterning, and organ growth (Bryant et al., 1988; Mahoney et al., 1991; Clark et al., 1995; Adler et al., 1998; Lawrence et al., 2008; Blair and McNeill, 2018; Strutt and Strutt, 2021). Ft and Ds bind extracellularly via heterotypic interaction (Matakatsu and Blair, 2004; Ma et al., 2003; Strutt and Strutt, 2002). Opposing proximal–distal expression gradients of Ds and four-jointed (Fj), a Golgi resident kinase that modulates Ds–Ft binding (Ma et al., 2003; Zeidler et al., 2000; Brittle et al., 2010; Simon et al., 2010), result in a planar polarized subcellular distribution of Ds on distal junctions and Ft on proximal junctions in wing discs (Brittle et al., 2012; Bosveld et al., 2012; Ambegaonkar et al., 2012).

Ft and Ds are thought to control tissue growth primarily via an atypical myosin, Dachs, at the junctional cortex (Mao et al., 2006; Rogulja et al., 2008). Dachs promotes growth by inhibiting Wts function by degrading Wts and/or regulating Wts conformational state (Cho et al., 2006; Vrabioiu and Struhl, 2015). Two additional proteins, Dachs ligand with SH3 domains (Dlish, a.k.a. Vamana) and a DHHC palmitoyltransferase Approximated (App), are required for Dachs function and localization to the junctional cortex (Matakatsu and Blair, 2008; Matakatsu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). Dlish forms a complex with Dachs, Ft, and Ds when expressed in S2 cells, and Dlish and Dachs are interdependent for cortical localization in vivo (Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). App palmitoylates both Dlish and Ft (Matakatsu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). Palmitoylation often increases the affinity of a protein for the plasma membrane (Linder and Deschenes, 2007), leading to the suggestion that App promotes Dlish-dependent Dachs localization to the junctional cortex (Zhang et al., 2016). Since the accumulation of Dachs at the cortex is influenced by Ds–Ft planar polarity, it has been proposed that Ds recruits Dachs to the distal edge to promote growth while Ft promotes Dachs degradation at the proximal edge to suppress growth (Rogulja et al., 2008; Bosveld et al., 2012; Brittle et al., 2012). However, this model seems inconsistent with the observation that ds ft double mutants have a much stronger overgrowth phenotype than either single mutant alone, which instead suggests that Ft and Ds work synergistically to repress growth (Matakatsu and Blair, 2006).

To understand how Ds–Ft signaling regulates the abundance, localization, and function of Dachs, Dlish, and App (hereafter called the core complex) at the junctional cortex, we explored the functions of the intracellular domains (ICDs) of Ds and Ft. We found that members of the core complex, in particular App, depend on the Ds ICD to accumulate in cortical puncta and promote tissue growth. In contrast, in the absence of its ligand Ft, Ds (via its ICD) promotes mislocalization and inactivation of the core complex. Strikingly, the loss of both Ds and Ft allows the core complex to accumulate to very high levels at the junctional cortex, indicating that neither Ds nor Ft is required for its cortical localization. Instead, our results suggest that Ds and Ft organize core complex proteins within the junctional cortex into discrete puncta with opposing consequences: Ft promotes degradation of the core complex whereas Ds protects it from degradation. Together, these findings reveal previously unrecognized mechanisms by which Ds and Ft control the subcellular localization and abundance of Dachs, Dlish, and App at the junctional cortex and thereby constrain tissue growth.

Results

Ft and Ds act synergistically to repress Yki activity

Current models propose that Ds and Ft function antagonistically. However, mutation of either gene causes overgrowth of wing discs (Fig. 1, A, B, and F), and combining mutations in both genes produces much greater overgrowth (Fig. 1 G, Bryant et al., 1988; Matakatsu and Blair, 2006). Together, these results suggest that rather than functioning antagonistically Ds and Ft function synergistically to repress tissue growth.

Both Ft and Ds suppress tissue growth by regulating localization and abundance of Dachs at the junctional cortex. (A–G) Representative wing discs stained with phalloidin showing the growth defects of the following genotypes: wild-type (A), dsUAO71 (B), dachsGC13 (C), dsUAO71ftG-rvdachsGC13/dsUAO71ftfddachsGC13 (D), dsUAO71ftG-rvdachsGC13/dsUAO71ftfd (E), ftG-rv/ftfd (F), and dsUAO71ftG-rv/dsUAO71ftfd (G). Panels F and G were stitched together because of their large size (see Materials and methods). (H) Expression of ban3-GFP, a Hippo pathway reporter, compared between ftG-rv/ftfd (or dsUAO71ftG-rv/ftfd) cells and dsUAO71ftGr-v cells in the wing disc. ban3-GFP is more highly expressed in dsUAO71ftG-rv cells than in ft mutant cells. ds ft clones are marked by the absence of Ds staining. (I) XZ section indicated by the blue dashed line in H. Red asterisks indicate ban3-GFP expression in peripodial cells. (J) Comparison of Dachs:GFP levels and subcellular localization in wild-type, dsUAO71, and ftfd mutant cells. (J′) In ds mutant cells, Dachs:GFP levels were slightly increased and primarily localized to the junctional cortex (J and J′). (J″) In ft mutant cells, Dachs:GFP levels increased more than in ds cells and localized both at the junctional cortex and to non-junctional puncta (J and J″). Clone boundaries and genotypes were determined by anti-Ft staining (Fig. S1 A). (K and K′) In comparison to ft cells, ds ft mutant cells displayed even more Dachs:GFP at the junctional cortex but lacked the non-junctional puncta. (L and M) IB analysis showing Dachs levels in imaginal tissue from wild-type (number matches the n for each of the following genotypes), dsUAO71(n = 5), ftG-rv/ftfd (n = 16), and dsUAO71ftG-rv/dsUAO71ftfd (n = 9). Dachs abundance increases slightly in ds but is much greater in ft and ds ft imaginal tissue. (M) Relative Dachs levels normalized to α-Tubulin. ****P < 0.0001, *** 0.0001 < P < 0.001, ns not significant (two-tailed unpaired t test between each genotype). (N) Localization of Ds and Dachs:GFP in the absence of Ft. Dachs:GFP was highly localized to the junctional cortex and colocalized with Ds in non-junctional puncta (yellow arrows). Scale bars: (A–G) 100 µm, (H–K and N) 5 µm. In this and all subsequent figures, fluorescently tagged proteins were viewed by native fluorescence. Antibody staining is indicated by an “α” symbol before the protein name. Yellow dashed lines indicate clone boundaries in this and subsequent figures (except where noted otherwise). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Both Ft and Ds suppress tissue growth by regulating localization and abundance of Dachs at the junctional cortex. (A–G) Representative wing discs stained with phalloidin showing the growth defects of the following genotypes: wild-type (A), dsUAO71 (B), dachsGC13 (C), dsUAO71ftG-rvdachsGC13/dsUAO71ftfddachsGC13 (D), dsUAO71ftG-rvdachsGC13/dsUAO71ftfd (E), ftG-rv/ftfd (F), and dsUAO71ftG-rv/dsUAO71ftfd (G). Panels F and G were stitched together because of their large size (see Materials and methods). (H) Expression of ban3-GFP, a Hippo pathway reporter, compared between ftG-rv/ftfd (or dsUAO71ftG-rv/ftfd) cells and dsUAO71ftGr-v cells in the wing disc. ban3-GFP is more highly expressed in dsUAO71ftG-rv cells than in ft mutant cells. ds ft clones are marked by the absence of Ds staining. (I) XZ section indicated by the blue dashed line in H. Red asterisks indicate ban3-GFP expression in peripodial cells. (J) Comparison of Dachs:GFP levels and subcellular localization in wild-type, dsUAO71, and ftfd mutant cells. (J′) In ds mutant cells, Dachs:GFP levels were slightly increased and primarily localized to the junctional cortex (J and J′). (J″) In ft mutant cells, Dachs:GFP levels increased more than in ds cells and localized both at the junctional cortex and to non-junctional puncta (J and J″). Clone boundaries and genotypes were determined by anti-Ft staining (Fig. S1 A). (K and K′) In comparison to ft cells, ds ft mutant cells displayed even more Dachs:GFP at the junctional cortex but lacked the non-junctional puncta. (L and M) IB analysis showing Dachs levels in imaginal tissue from wild-type (number matches the n for each of the following genotypes), dsUAO71(n = 5), ftG-rv/ftfd (n = 16), and dsUAO71ftG-rv/dsUAO71ftfd (n = 9). Dachs abundance increases slightly in ds but is much greater in ft and ds ft imaginal tissue. (M) Relative Dachs levels normalized to α-Tubulin. ****P < 0.0001, *** 0.0001 < P < 0.001, ns not significant (two-tailed unpaired t test between each genotype). (N) Localization of Ds and Dachs:GFP in the absence of Ft. Dachs:GFP was highly localized to the junctional cortex and colocalized with Ds in non-junctional puncta (yellow arrows). Scale bars: (A–G) 100 µm, (H–K and N) 5 µm. In this and all subsequent figures, fluorescently tagged proteins were viewed by native fluorescence. Antibody staining is indicated by an “α” symbol before the protein name. Yellow dashed lines indicate clone boundaries in this and subsequent figures (except where noted otherwise). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

To determine if Ds and Ft synergistically repress growth via the Hippo pathway, we compared the effect of ds ft double mutants to ft single mutant cells on the ban3-GFP, a reporter of Yki activity (Matakatsu and Blair, 2012). We observed that the expression of ban3-GFP is upregulated to a greater extent in ds ft than in ft cells (Fig. 1, H and I). Thus, Ds and Ft synergistically repress growth by repressing Yki activity.

Ft and Ds restrict tissue growth by regulating the abundance of Dachs at the junctional cortex

The finding that Ft and Ds function synergistically to restrict growth seems at odds with the model that Ds promotes Dachs accumulation at the junctional cortex while Ft promotes its degradation. To explore this paradox, we examined Dachs localization and abundance in ds ft double mutants relative to ds or ft single mutants. Compared with wild-type, we found that Dachs:GFP accumulated at slightly greater levels in ds mutant tissue (Fig. 1, J and J′) and was even more abundant in ft mutant tissue (Fig. 1 J). Additionally, we noticed that in ft mutant cells, Dachs was distributed in puncta across the apical cortex except in mutant cells at the clone borders with wild-type cells (Fig. 1, J and J″). We infer this effect might occur because Ds protein in ft mutant cells at the edge of clones interacts with Ft and is tightly localized at the boundary with adjacent wild-type cells, while in the middle of ft clones Ds is mislocalized across the apical cortex (Strutt and Strutt, 2002; Ma et al., 2003; see below).

If Ds is necessary to recruit Dachs to the junctional cortex, then the loss of both Ds and Ft should result in decreased Dachs cortical accumulation in comparison to the loss of just Ft alone. Remarkably, we instead found that ds ft cells accumulated Dachs at the junctional cortex to even higher levels than those lacking Ft alone (Fig. 1, K and K'; and Fig. S1, B and C). Furthermore, the non-junctional Dachs puncta we observed in ft mutant cells were absent in ds ft double mutant cells (Fig. 1, K and K'). These results clearly indicate that neither Ds nor Ft is required for the cortical localization of Dachs. Additionally, the increased level of cortical Dachs and absence of non-junctional Dachs puncta in ds ft double mutant cells suggests that Ds can promote the removal of Dachs from the junctional cortex. Given that ds ft double mutant discs are significantly more overgrown than ft mutants alone (Fig. 1, F and G, Matakatsu and Blair, 2006), the non-junctional Dachs we observed in ft mutant cells likely do not promote growth.

Localizations of Ft, Ds, App, Dlish and Dachs under different conditions and Crispr tagging of App. (A) Anti-Ft staining for the wing disc displayed in Fig. 1 J. ft clones are indicated by the lack of staining. The ds clone displays stronger Ft staining than wild-type (ds +/+ ft trans-heterozygous) cells. (B) Comparison of Dachs subcellular localization between ft cells and ds ft cells (see also Fig. 1, K and K′. The wing disc was stained with anti-Dachs staining. (C) Ratio of Dachs:GFP in ds ft compared with ft at junctions or the medial cortex. (D) Anti-Ds staining for the wing disc displayed in Fig. 4 E. Ds is mislocalized at the apical surface and junction. (E and F) Expression and localization of Ds:GFP in ds:GFP homozygous (E) and DsΔICD:GFP in dsΔICD:GFP homozygous (F) wing discs. Adherens junctions are marked by anti-DECad staining. Wing discs in dsΔICD:GFP homozygotes are smaller than ds:GFP homozygotes. (G) App tagging by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. YFP was tagged at C-terminus. 3×V5 was inserted at the extracellular domain between transmembrane domains 3 (TM 3) and 4 (TM 4). (H) C-terminus tagging with YFP for app using CRISPR-Cas9. Target sequence (red line) and donor DNA are shown. HAL (blue line), left homology arm; HAR (light green line), right homology arm. (I) Internal V5 tagging for app using CRISPR-Cas9. 3×V5 (green triangle), target sequence (red underline), and protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site (red letters) are shown. 3×V5 epitope tag was inserted after Histidine at 221. (J) Colocalization of App, Dlish, and Dachs at junctions. App, Dlish, and Dachs are colocalized at junctional puncta (yellow arrows). Scale bars, 5 µm (A, B, and D), 10 µm (E and F), 1 µm (J).

Localizations of Ft, Ds, App, Dlish and Dachs under different conditions and Crispr tagging of App. (A) Anti-Ft staining for the wing disc displayed in Fig. 1 J. ft clones are indicated by the lack of staining. The ds clone displays stronger Ft staining than wild-type (ds +/+ ft trans-heterozygous) cells. (B) Comparison of Dachs subcellular localization between ft cells and ds ft cells (see also Fig. 1, K and K′. The wing disc was stained with anti-Dachs staining. (C) Ratio of Dachs:GFP in ds ft compared with ft at junctions or the medial cortex. (D) Anti-Ds staining for the wing disc displayed in Fig. 4 E. Ds is mislocalized at the apical surface and junction. (E and F) Expression and localization of Ds:GFP in ds:GFP homozygous (E) and DsΔICD:GFP in dsΔICD:GFP homozygous (F) wing discs. Adherens junctions are marked by anti-DECad staining. Wing discs in dsΔICD:GFP homozygotes are smaller than ds:GFP homozygotes. (G) App tagging by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. YFP was tagged at C-terminus. 3×V5 was inserted at the extracellular domain between transmembrane domains 3 (TM 3) and 4 (TM 4). (H) C-terminus tagging with YFP for app using CRISPR-Cas9. Target sequence (red line) and donor DNA are shown. HAL (blue line), left homology arm; HAR (light green line), right homology arm. (I) Internal V5 tagging for app using CRISPR-Cas9. 3×V5 (green triangle), target sequence (red underline), and protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site (red letters) are shown. 3×V5 epitope tag was inserted after Histidine at 221. (J) Colocalization of App, Dlish, and Dachs at junctions. App, Dlish, and Dachs are colocalized at junctional puncta (yellow arrows). Scale bars, 5 µm (A, B, and D), 10 µm (E and F), 1 µm (J).

To determine how the loss of Ft and/or Ds affects Dachs abundance, we compared Dachs protein levels in ds null, ft null, and ds ft null double mutant imaginal tissue using immunoblots (IBs) (Fig. 1, L and M). While ds mutant tissues displayed slightly higher levels of Dachs, presumably because the loss of Ds causes decreased Ft activity (Sopko et al., 2009; Feng and Irvine, 2009), Dachs abundance was significantly greater in ft mutant tissue than either ds or wild-type tissues. However, in ds ft double mutant tissues, Dachs levels were similar to ft mutants (Fig. 1, L and M), suggesting that increased cortical Dachs in ds ft double mutants relative to ft mutants (Fig. 1 K) reflects changes in localization rather than abundance. These results also indicate that increased junctional accumulation of Dachs is critical to growth. Consistent with this idea, loss of one copy of dachs strongly suppressed ds ft overgrowth (Fig. 1, E and G) and homozygous loss of dachs was epistatic to it (Fig. 1, C, D, and G).

The Ds ICD regulates growth in a context-dependent manner

Previous studies have shown that in the absence of Ft, Ds becomes mislocalized from the junctions and is much more diffusely distributed across the apical membrane (Strutt and Strutt, 2002; Ma et al., 2003; Fig. 1 K and Fig. S1 D). Because Ds and Dachs are known to physically interact (Bosveld et al., 2012), mislocalized Ds might recruit Dachs away from the junctional cortex, thereby reducing growth. Careful examination of Ds and Dachs in ft mutant cells revealed that both displayed non-junctional puncta that often colocalized (Fig. 1 N), consistent with the possibility that Ds can remove Dachs from the junctional cortex.

To better understand how Ds affects Dachs subcellular localization, we next focused on the ICD of Ds, which has been proposed to form a complex with Dachs and Dlish (Bosveld et al., 2012, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). To dissect the function of Ds, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to replace the Ds ICD with GFP (DsΔICD:GFP; Fig. 2 A). DsΔICD:GFP expression levels and localization were indistinguishable from wild-type Ds (Fig. 2, B and C; and Fig. S1, E and F). Ft also was normally localized in dsΔICD:GFP cells, suggesting that DsΔICD:GFP binds Ft, thereby promoting its ability to reduce growth (Fig. 2 D). In marked contrast to ds null wings and wing discs, which are slightly overgrown, dsΔICD:GFP wings and wing discs were smaller than normal (Fig. 2, E–K). This result is surprising given our evidence that Ds can repress growth by removing Dachs from the junctional cortex, but likely reflects the complex nature of Ds function in growth control: in the presence of Ft, Ds functions both to promote growth by binding and protecting Dachs from Ft-mediated degradation and to bind Ft, thereby promoting its ability to reduce growth. If so, then loss of ft should be epistatic to dsΔICD:GFP. Indeed, the dsΔICDft double mutant combination produced severe overgrowth similar to that of ds ft double mutant combination (Fig. 2 M, compare with ds ft double mutant in Fig. 1 G). Taken together, our results indicate that the function of the Ds ICD in growth control is context-dependent: in the presence of Ft the Ds ICD promotes Dachs activity while in the absence of Ft the Ds ICD represses Dachs activity.

The Ds ICD has context-dependent effects on tissue growth. (A) Structure of DsΔICD:GFP. The ICD was replaced with GFP (green) using CRISPR-Cas9. ICD (red line) and TM, transmembrane domain (sky blue). (B and C) Localization of Ds:GFP in a dsGFP homozygote (B) and DsΔICD:GFP in a dsΔICD:GFP homozygote (C). Ds:GFP and DsΔICD:GFP localize at the junctional cortex. Adherens junctions are marked by DE-Cad staining. (D) Ft localization is normal in dsΔICD:GFP mutant cells. Mutant clones are marked with the absence of nuclear GFP. (E–G) Representative adult wings in indicated genotypes. The dsΔICD:GFP wing displays undergrowth (F). (H) Quantification of wing size in wild-type, dsΔICD:GFP, and dsΔICD (GFP-) mutants. ****P < 0.0001, ns, not significant (two-tailed unpaired t test between each genotype). Wild-type (n = 21), dsΔICD:GFP (n = 21), dsΔICD (n = 22). (I–M) Growth of wing discs with the indicated ds and ft alleles. Genotypes: wild-type (I), dsΔICD:GFP (J), dsUAO71 (K), ftG-rv/ftfd (L), and dsΔICD:GFPftG-rv/dsΔICD:GFPftfd (M). Although loss of the Ds ICD leads to undergrowth (J), in combination with loss of ft mutant it causes severe overgrowth (M). Panels L and M were stitched together because of their large size. Scale bars, (B and C) 1 µm, (D) 5 µm, and (E–G and I–M) 100 µm.

The Ds ICD has context-dependent effects on tissue growth. (A) Structure of DsΔICD:GFP. The ICD was replaced with GFP (green) using CRISPR-Cas9. ICD (red line) and TM, transmembrane domain (sky blue). (B and C) Localization of Ds:GFP in a dsGFP homozygote (B) and DsΔICD:GFP in a dsΔICD:GFP homozygote (C). Ds:GFP and DsΔICD:GFP localize at the junctional cortex. Adherens junctions are marked by DE-Cad staining. (D) Ft localization is normal in dsΔICD:GFP mutant cells. Mutant clones are marked with the absence of nuclear GFP. (E–G) Representative adult wings in indicated genotypes. The dsΔICD:GFP wing displays undergrowth (F). (H) Quantification of wing size in wild-type, dsΔICD:GFP, and dsΔICD (GFP-) mutants. ****P < 0.0001, ns, not significant (two-tailed unpaired t test between each genotype). Wild-type (n = 21), dsΔICD:GFP (n = 21), dsΔICD (n = 22). (I–M) Growth of wing discs with the indicated ds and ft alleles. Genotypes: wild-type (I), dsΔICD:GFP (J), dsUAO71 (K), ftG-rv/ftfd (L), and dsΔICD:GFPftG-rv/dsΔICD:GFPftfd (M). Although loss of the Ds ICD leads to undergrowth (J), in combination with loss of ft mutant it causes severe overgrowth (M). Panels L and M were stitched together because of their large size. Scale bars, (B and C) 1 µm, (D) 5 µm, and (E–G and I–M) 100 µm.

The ICD of Ds organizes Dachs into cortical puncta

How does the Ds ICD regulate growth? Dachs and Dlish are known to colocalize with Ds in puncta at the junctional cortex in wing discs and to associate with the Ds ICD in vitro (Bosveld et al., 2012, 2016; Brittle et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). Consistent with these studies, we found a strong correlation between wild-type Ds and Dachs in puncta at the junctional cortex (Fig. 3, A and B). However, in dsΔICD mutant clones, Dachs appeared less punctate and was irregularly localized at the junctional cortex (Fig. 3 C). Moreover, unlike wild-type Ds, DsΔICD:GFP did not strongly colocalize with Dachs (Fig. 3, D and E).

The Ds ICD influences Dachs localization. (A) Ds:GFP and Dachs colocalize at junctional puncta (green arrows) in wing discs. (B) Fluorescence intensity of Dachs and Ds:GFP along the yellow line in A showing strong colocalization. (C) In dsΔICD clones, Dachs:GFP loses its punctate appearance and becomes more uniformly distributed along the junctional cortex (the absence of nuclear RFP serves as clonal marker). (D) Localization of Dachs and DsΔICD:GFP in a dsΔICD:GFP homozygote. Dachs fails to colocalize with DsΔICD:GFP (green arrows indicate DsΔICD:GFP puncta, red arrows indicate Dachs puncta). (E) Fluorescence intensity of Dachs and DsΔICD:GFP along the yellow line in D showing weak colocalization in comparison to B (Pearson’s correlation coefficient r = 0.135 versus r = 0.795). (F–F″) Dachs:GFP accumulates strongly and almost exclusively at the junctional cortex in dsΔICDft mutant clones. Note the absence of non-junctional puncta of Dachs:GFP here in comparison to ft mutant cells in Fig. 1, J″. Scale bars, (A, C″, C‴, D, and F″) 1 µm, (C and F) 5 µm.

The Ds ICD influences Dachs localization. (A) Ds:GFP and Dachs colocalize at junctional puncta (green arrows) in wing discs. (B) Fluorescence intensity of Dachs and Ds:GFP along the yellow line in A showing strong colocalization. (C) In dsΔICD clones, Dachs:GFP loses its punctate appearance and becomes more uniformly distributed along the junctional cortex (the absence of nuclear RFP serves as clonal marker). (D) Localization of Dachs and DsΔICD:GFP in a dsΔICD:GFP homozygote. Dachs fails to colocalize with DsΔICD:GFP (green arrows indicate DsΔICD:GFP puncta, red arrows indicate Dachs puncta). (E) Fluorescence intensity of Dachs and DsΔICD:GFP along the yellow line in D showing weak colocalization in comparison to B (Pearson’s correlation coefficient r = 0.135 versus r = 0.795). (F–F″) Dachs:GFP accumulates strongly and almost exclusively at the junctional cortex in dsΔICDft mutant clones. Note the absence of non-junctional puncta of Dachs:GFP here in comparison to ft mutant cells in Fig. 1, J″. Scale bars, (A, C″, C‴, D, and F″) 1 µm, (C and F) 5 µm.

In the absence of ft, Dachs colocalizes with Ds in non-junctional puncta (Fig. 1, J″ and N). To ask if the Ds ICD is necessary for this effect, we examined Dachs in dsΔICDft double mutant tissue. We found that non-junctional Dachs puncta were dramatically reduced and instead, Dachs accumulated strongly at the junctional cortex, similar to ds ft double mutants (Fig. 3 F). Given that dsΔICDft and ds ft double mutants display similar overgrowth phenotypes (Fig. 1 G and Fig. 2 M), these results suggest that the Ds ICD associates with Dachs, thereby influencing Dachs’ localization and growth-promoting function at the junctional cortex.

Ds regulates App localization at the junctional cortex

App encodes a multipass transmembrane palmitoyltransferase that is thought to regulate both Ft and Dlish through posttranslational palmitoylation (Matakatsu and Blair, 2008; Matakatsu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). App is also localized to the junctions (Matakatsu and Blair, 2008), but what determines its localization is unclear. To visualize App, we tagged it at the C-terminus with YFP (App:YFP) or in the extracellular domain with V5 (App:V5) using CRISPR-Cas9 (Fig. S1, G–I). Both tagged alleles display normal wing and leg size and shape, indicating the tags do not interfere with App function. App:YFP localized to junctional puncta in a similar pattern to Dachs and Ds and was predominantly localized at proximodistal junctions in wing discs (Fig. 4, A–D), reminiscent of Dachs, Dlish, and Ds planar polarized distribution (Brittle et al., 2012; Ambegaonkar et al., 2012; Misra and Irvine, 2016). In fact, App colocalized with Dachs, Ds, and Dlish (Fig. 4, A–D and Fig. S1 J, see below).

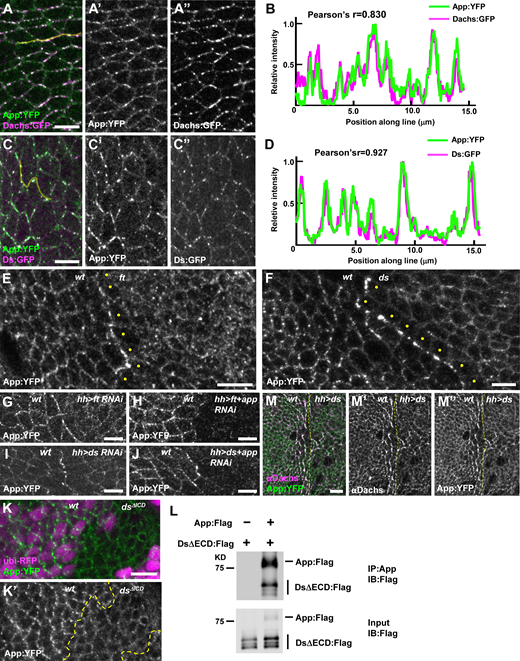

Ds and Ft regulate App at cell junctions.(A–D) Ds, Dachs, and App colocalize at junctional puncta. Representative image (A) and line scan (yellow line) quantification of fluorescence intensity (B) showing colocalization of App:YFP and Dachs:GFP. Representative image (C) and line scan (yellow line) quantification of fluorescence intensity (D) showing colocalization of Ds:GFP and App:YFP. (E) Loss of ft causes mislocalization of App:YFP from junctional puncta to a more uniform distribution across the apical surface (clonal marker not shown). Note that App:YFP accumulates at the boundary between wild-type and ft mutant cells and appears reduced in the cytoplasm of ft cells at the edge of the clone (yellow dots). (F) The localization of App:YFP is altered in ds mutant cells. App:YFP is more diffuse in the absence of Ds and accumulates at the clone boundary (clonal marker not shown). Note that cytoplasmic App:YFP is reduced in ds cells adjacent to the boundary (yellow dots). (G and H) App:YFP accumulates at the boundary between wild-type and ft RNAi cells (G) but fails to accumulate at the boundary in ft, app double RNAi cells (H), indicating that App in ft depleted cells is recruited to contacts with wild-type cells. (I and J) App:YFP accumulates at the boundary between wild-type and ds RNAi cells (I) and at the boundary between wild-type and ds, app double RNAi cells (J), indicating that App in ds depleted cells is not recruited to contacts with wild-type cells. (K) Junctional puncta of App:YFP are much less apparent in dsΔICD clones. (L) The Ds ICD co-immunoprecipitates App in S2 cells. (M) Ectopic expression of Ds in the posterior compartment causes Dachs and App:YFP to colocalize in a planar polarized fashion for two to three cell diameters outside the Ds overexpression domain. Yellow dashed lines indicate the anterior/posterior boundary. Scale bars, 5 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Ds and Ft regulate App at cell junctions.(A–D) Ds, Dachs, and App colocalize at junctional puncta. Representative image (A) and line scan (yellow line) quantification of fluorescence intensity (B) showing colocalization of App:YFP and Dachs:GFP. Representative image (C) and line scan (yellow line) quantification of fluorescence intensity (D) showing colocalization of Ds:GFP and App:YFP. (E) Loss of ft causes mislocalization of App:YFP from junctional puncta to a more uniform distribution across the apical surface (clonal marker not shown). Note that App:YFP accumulates at the boundary between wild-type and ft mutant cells and appears reduced in the cytoplasm of ft cells at the edge of the clone (yellow dots). (F) The localization of App:YFP is altered in ds mutant cells. App:YFP is more diffuse in the absence of Ds and accumulates at the clone boundary (clonal marker not shown). Note that cytoplasmic App:YFP is reduced in ds cells adjacent to the boundary (yellow dots). (G and H) App:YFP accumulates at the boundary between wild-type and ft RNAi cells (G) but fails to accumulate at the boundary in ft, app double RNAi cells (H), indicating that App in ft depleted cells is recruited to contacts with wild-type cells. (I and J) App:YFP accumulates at the boundary between wild-type and ds RNAi cells (I) and at the boundary between wild-type and ds, app double RNAi cells (J), indicating that App in ds depleted cells is not recruited to contacts with wild-type cells. (K) Junctional puncta of App:YFP are much less apparent in dsΔICD clones. (L) The Ds ICD co-immunoprecipitates App in S2 cells. (M) Ectopic expression of Ds in the posterior compartment causes Dachs and App:YFP to colocalize in a planar polarized fashion for two to three cell diameters outside the Ds overexpression domain. Yellow dashed lines indicate the anterior/posterior boundary. Scale bars, 5 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

We next explored App’s relationship with Ft and Ds. In ft mutant cells, App displayed decreased junctional accumulation but retained its punctate appearance, similar to Ds (Fig. 4 E and Fig. S1 D). In ds mutant cells, App displayed junctional localization and lacked distinct puncta (Fig. 4 F). Notably, App distribution differed significantly from both Dachs and Dlish, which displayed increased accumulation at the junctional cortex in either ft or ds mutant cells (Fig. 1 J, Bosveld et al., 2012; Brittle et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). These observations suggest that Dachs and Dlish are regulated differently from App and that App is more directly dependent upon Ds for junctional localization.

Previous studies have shown that due to their heterophilic interactions, Ft and Ds accumulate at the boundary of either ds or ft mutant clones (Strutt and Strutt, 2002; Ma et al., 2003). We found that App also accumulated at these boundaries (Fig. 4, E and F), raising the possibility that Ft or Ds recruits App. To determine this, we used ft RNAi in the posterior compartment of the wing (driven by hh-Gal4) to create a polarized accumulation of Ds on the posterior side of the boundary and Ft on the anterior (wild-type) side. Conversely, ds RNAi in the posterior caused Ft to accumulate on the posterior side of the boundary and Ds to accumulate on the anterior (wild-type) side. As we observed in somatic mosaic clones (Fig. 4, E and F), App accumulated at the boundary between wild-type cells and either ft (Fig. 4 G) or ds knockdown tissue (Fig. 4 I). To determine on which side of the boundary App accumulated, we used double RNAi to deplete both App and either Ft or Ds. Co-depletion of Ft and App in the posterior strongly reduced accumulation of App at the boundary (Fig. 4 H), indicating that App accumulates with Ds in the posterior (Ft-depleted) cells at the boundary. Conversely, co-depletion of Ds and App did not affect App accumulation at the boundary (Fig. 4 J), indicating that when Ds is depleted, App accumulates in adjacent wild-type cells at the boundary. In short, these results show that Ds recruits App to these boundaries while Ft does not.

Three further observations suggest that the Ds ICD interacts with App. First, App puncta was less apparent at the junctional cortex in dsΔICD mutant clones (Fig. 4 K). Second, App co-immunoprecipitated with the Ds ICD in S2 cells (Fig. 4 L). Third, when we ectopically expressed Ds in the posterior compartment, we found that as with Dachs, this resulted in repolarization and stabilization of App in cells just anterior to the compartment boundary (Fig. 4 M, Bosveld et al., 2012; Brittle et al., 2012; Ambegaonkar et al., 2012). Taken together, our results are consistent with the idea that the Ds ICD coordinately recruits and stabilizes Dachs and App (and possibly Dlish) in puncta at the junctional cortex.

Mapping functional domains in the Ds ICD

We next mapped functional domains in the Ds ICD using a combination of cell culture and in vivo experiments. To identify binding domains in the Ds ICD, we used a previously described approach to polarize protein domains at the cortex of cultured S2 cells (Johnston et al., 2009; Bosveld et al., 2016; Tokamov et al., 2023). Specifically, we fused the full-length or truncated Ds ICD to the extracellular domain (ECD) of the homophilic adhesion protein Echinoid (Ed), which causes cells to aggregate and accumulate the fusion protein at points of contact. Using this approach, we asked which domains in the Ds ICD are necessary to recruit core complex proteins (Fig. 5 A). In control cells, the Ed ECD fused to Flag (Ed:Flag) accumulated at cell–cell contacts, but cotransfected core complex proteins instead localized to the cytoplasm or to cytoplasmic foci (Fig. S2 A). In contrast, Ed fused to Ds ICD (Ed:Ds:Flag) recruited core complex proteins to cell contacts (Fig. 5, B and C).

Mapping Ds functional domains. (A) Structure of the Ds ICD and the deletions generated for the S2 cell recruitment assay and CRISPR mutations in vivo. Full-length Ds ICD or Ds ICD deletions (ΔA, ΔB, ΔC, and ΔD) were fused to the Ed ECD for S2 cell experiments. The same domains are deleted with CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo. Abbreviations: Conserved motif 1–3 (CM1–3, red boxes): transmembrane domain (TM, sky blue box). (B) Ed:Ds:Flag recruits Dachs:GFP, App, and Dlish:HA to cell contacts (yellow arrows). Ed homophilic interactions promote the accumulation of the Ed fusion proteins at cell–cell contacts. (C–F) Recruitment of Dachs:GFP by Ds ICD and its deletions. Ed:Ds:Flag and Ed:DsΔA:Flag recruit Dachs:GFP to cell contacts (yellow arrows), but Ed:DsΔB:Flag and Ed:DsΔD:Flag fail to recruit Dachs:GFP. (G–L) Adult wings of the indicated genotypes. (M) Quantification of wing size in wild-type and ds ICD deletion mutants. ****P < 0.0001 (two-tailed unpaired t test between each genotype). Wild-type (n = 55), ds:Flag (n = 62), dsΔICD:GFP (n = 31), dsΔA:Flag (n = 28), dsΔB:Flag (n = 23), dsΔC:Flag (n = 94), dsΔD:Flag (n = 22). (N–S) Tarsal segments in legs from flies of the indicated genotypes. Numbers in the top right corner indicate the percentage of animals with normal tarsal segments. Fused tarsal segments are marked with yellow arrow heads. (T–W) Dachs localization in wing discs of the indicated genotypes. Dachs colocalizes with Ds in ds:Flag (T) and dsΔA:Flag (U), but they colocalize less in dsΔB:Flag (V) and dsΔD:Flag (W). Yellow circles indicate Ds puncta. (X) App puncta, stained extracellularly with a pulse-chase protocol (see Materials and methods) are lost in dsΔD:Flag clones. Scale bars (B, C–F, and X) 5 µm, (G–L and N–S) 100 µm, (T–W) 1 µm. In this and subsequent figures where epitope tags (Flag, HA, V5) are indicated, antibodies were used that recognize those tags.

Mapping Ds functional domains. (A) Structure of the Ds ICD and the deletions generated for the S2 cell recruitment assay and CRISPR mutations in vivo. Full-length Ds ICD or Ds ICD deletions (ΔA, ΔB, ΔC, and ΔD) were fused to the Ed ECD for S2 cell experiments. The same domains are deleted with CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo. Abbreviations: Conserved motif 1–3 (CM1–3, red boxes): transmembrane domain (TM, sky blue box). (B) Ed:Ds:Flag recruits Dachs:GFP, App, and Dlish:HA to cell contacts (yellow arrows). Ed homophilic interactions promote the accumulation of the Ed fusion proteins at cell–cell contacts. (C–F) Recruitment of Dachs:GFP by Ds ICD and its deletions. Ed:Ds:Flag and Ed:DsΔA:Flag recruit Dachs:GFP to cell contacts (yellow arrows), but Ed:DsΔB:Flag and Ed:DsΔD:Flag fail to recruit Dachs:GFP. (G–L) Adult wings of the indicated genotypes. (M) Quantification of wing size in wild-type and ds ICD deletion mutants. ****P < 0.0001 (two-tailed unpaired t test between each genotype). Wild-type (n = 55), ds:Flag (n = 62), dsΔICD:GFP (n = 31), dsΔA:Flag (n = 28), dsΔB:Flag (n = 23), dsΔC:Flag (n = 94), dsΔD:Flag (n = 22). (N–S) Tarsal segments in legs from flies of the indicated genotypes. Numbers in the top right corner indicate the percentage of animals with normal tarsal segments. Fused tarsal segments are marked with yellow arrow heads. (T–W) Dachs localization in wing discs of the indicated genotypes. Dachs colocalizes with Ds in ds:Flag (T) and dsΔA:Flag (U), but they colocalize less in dsΔB:Flag (V) and dsΔD:Flag (W). Yellow circles indicate Ds puncta. (X) App puncta, stained extracellularly with a pulse-chase protocol (see Materials and methods) are lost in dsΔD:Flag clones. Scale bars (B, C–F, and X) 5 µm, (G–L and N–S) 100 µm, (T–W) 1 µm. In this and subsequent figures where epitope tags (Flag, HA, V5) are indicated, antibodies were used that recognize those tags.

Ds Domain D is required for recruitment of Dachs in S2 cells. (A) Ed:Flag does not recruit Dachs:GFP and App to cell–cell contacts in S2 cells. Ed:Flag is localized at cell–cell contacts (yellow arrow in A–A'''). Dachs:GFP and App are distributed to the cytoplasm and cytoplasmic foci (A″ and A‴). (B) High homology between Ds and Dchs1 (H. sapiens) in domain D. Identical (black) and similar (gray) amino acids are shaded. (C) Constructs for Ed ECD fused to Ds ICD or its deletions for the S2 cell recruitment assay. (D) Ed:DsΔE:Flag recruits Dachs:GFP to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). (E) Ed:Ds D:Flag recruits Dachs:GFP to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). Scale bars, 1 µm (A, D, and E).

Ds Domain D is required for recruitment of Dachs in S2 cells. (A) Ed:Flag does not recruit Dachs:GFP and App to cell–cell contacts in S2 cells. Ed:Flag is localized at cell–cell contacts (yellow arrow in A–A'''). Dachs:GFP and App are distributed to the cytoplasm and cytoplasmic foci (A″ and A‴). (B) High homology between Ds and Dchs1 (H. sapiens) in domain D. Identical (black) and similar (gray) amino acids are shaded. (C) Constructs for Ed ECD fused to Ds ICD or its deletions for the S2 cell recruitment assay. (D) Ed:DsΔE:Flag recruits Dachs:GFP to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). (E) Ed:Ds D:Flag recruits Dachs:GFP to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). Scale bars, 1 µm (A, D, and E).

To determine the essential domains for core complex recruitment by Ds ICD, we first focused on two non-overlapping domains we denote A and B (Fig. 5 A) because each contains conserved motifs (CM1–3) found in mammalian Ds (Hulpiau and van Roy, 2009). Core complex proteins were recruited to cell contacts by domain B (Ed:Ds ΔΑ:Flag; Fig. 5 D) but not by domain A (Ed:Ds ΔB:Flag; Fig. 5 E). We then defined a smaller region within B (domain D) that includes CM2 and is necessary for recruitment (Fig. 5, A and F; and Fig. S2, B–E).

To examine the functional significance of these domains in vivo, we generated fly lines lacking these portions using CRISPR-Cas9 (Fig. 5, G–S). Interestingly, dsΔA:Flag, dsΔB:Flag, dsΔC:Flag, and dsΔD:Flag all led to undergrowth in the wing that was milder than that of dsΔICD:GFP (Fig. 5, G–M). Additionally, we noted that dsΔB:Flag, dsΔC:Flag, and dsΔD:Flag displayed defects in leg tarsal segmentation commonly observed in Ft signaling mutants while dsΔA:Flag did not (Fig. 5, N–S). Thus, while both domain A and B are involved in growth control, domain B alone is sufficient for the Ds–Ft signaling functions that pattern the leg.

To determine if results from our S2 cell experiments reflect in vivo functions, we asked if Ds deletions recruit the core complex to junctional puncta (Fig. 5, T–X). The expression pattern, protein level, and subcellular distribution of all Ds mutant proteins were indistinguishable from endogenous Ds or Ds:Flag (Fig. S3, A–D). While Dachs colocalized with Ds:Flag and DsΔA:Flag at junctional puncta (Fig. 5, T and U; and Fig. S3, E and F), it did not colocalize as well with DsΔB:Flag and DsΔD:Flag (Fig. 5, V and W; and Fig. S3, G and H). Moreover, App was dramatically reduced in dsΔB:Flag and dsΔD:Flag (Fig. 5 X and data not shown). Taken together, our results suggest that domain D is responsible for core complex recruitment to the junctional cortex while domain A might control growth in parallel through other effectors (see Discussion). Consistent with this idea, animals carrying the heteroallelic combinations dsΔA:Flag/dsΔB:Flag or dsΔA:Flag/dsΔD:Flag showed normal tissue growth in the wing and leg patterning (Fig. S3, I–N).

Mapping functional domains in the Ds ICD. (A–D) Anti-Ds staining in dsΔA:Flag, dsΔB:Flag, dsΔC:Flag, and dsΔD:Flag clones. Mutant clones are labeled by the absence of GFP. The level and distribution of Ds did not change in ds deletion mutants. (E–H) Quantification of fluorescence intensity along cell junctions showing colocalization of Dachs with Ds:Flag and its deletions. Dachs:Flag (E) and DsΔA:Flag (F) show stronger colocalization with Dachs. DsΔB:Flag (G) and DsΔD:Flag (H) show weaker colocalization with Dachs. (I–K) Wings of the indicated genotypes showing transheterozygous complementation. dsΔA:Flag/dsΔB:Flag and dsΔA:Flag/dsΔD:Flag wings are almost normal size (I and J). dsΔB:Flag/dsΔD:Flag wings display slight undergrowth (K). (L–N) Leg phenotype in transheterozygous combinations. Boundaries of tarsal segments are marked with black lines. dsΔA:Flag/dsΔB:Flag (L) and dsΔA:Flag/dsΔD:Flag (M) legs display normal segmentation. dsΔB:Flag/dsΔD:Flag legs (N) are fused at T2 and T3 (yellow arrow). Scale bars, 5 µm (A–D), 1 µm (E–H), 100 µm (I–K and L–N).

Mapping functional domains in the Ds ICD. (A–D) Anti-Ds staining in dsΔA:Flag, dsΔB:Flag, dsΔC:Flag, and dsΔD:Flag clones. Mutant clones are labeled by the absence of GFP. The level and distribution of Ds did not change in ds deletion mutants. (E–H) Quantification of fluorescence intensity along cell junctions showing colocalization of Dachs with Ds:Flag and its deletions. Dachs:Flag (E) and DsΔA:Flag (F) show stronger colocalization with Dachs. DsΔB:Flag (G) and DsΔD:Flag (H) show weaker colocalization with Dachs. (I–K) Wings of the indicated genotypes showing transheterozygous complementation. dsΔA:Flag/dsΔB:Flag and dsΔA:Flag/dsΔD:Flag wings are almost normal size (I and J). dsΔB:Flag/dsΔD:Flag wings display slight undergrowth (K). (L–N) Leg phenotype in transheterozygous combinations. Boundaries of tarsal segments are marked with black lines. dsΔA:Flag/dsΔB:Flag (L) and dsΔA:Flag/dsΔD:Flag (M) legs display normal segmentation. dsΔB:Flag/dsΔD:Flag legs (N) are fused at T2 and T3 (yellow arrow). Scale bars, 5 µm (A–D), 1 µm (E–H), 100 µm (I–K and L–N).

The Ft intra- and extracellular domains have opposing functions

In the absence of Ft, we propose that Ds, which is no longer anchored junctionally, represses growth by removing Dachs from the junctional cortex. If so, then restoring Ds junctional localization, without restoring Ft’s ability to degrade Dachs, should strongly enhance tissue growth. To do this, we deleted the Ft ICD using CRISPR-Cas9 (ftΔICD; Fig. S4 A). Interestingly, we observed much greater overgrowth in ftΔICD wing discs compared with ft null mutant tissues (Fig. 6, A–C). Consistent with the idea that FtΔICD promotes growth by holding Ds (and Dachs) at the junctional cortex, we found that in ftΔICD mutant cells Ds was localized in an almost normal pattern (Fig. 6 D), in striking contrast to Ds in ft null mutant tissue (Fig. 1 K and Fig. S1 D). Additionally, although Dachs was mislocalized in non-junctional puncta in ft null mutant cells (Fig. 1, J and K), Dachs was predominantly localized to the junctional cortex in ftΔICD mutant cells (Fig. 6 D). App appeared normally localized at the junctional cortex in ftΔICD mutant cells (Fig. 6 E), in striking contrast to ds or dsΔICD mutant cells (Fig. 4, F and K).

Ft ICD recruits Dachs and influences its abundance.(A) CRISPR-Cas9 induced ftΔICD mutant. The target sequence (green line), PAM site (green box), and transmembrane domain (TM; blue letters) are shown. The resulting 4-bp deletion led to a premature stop codon after the transmembrane domain. The altered amino acids are shown in red letters. (B) App:YFP is increased in junctional puncta in ft61 mutant cells. (C) Dachs:GFP is increased at the junctional puncta in ft61 mutant clones. Mutant clones are marked by the absence of ubi-RFP. (D) Phosphorylation of wild-type Ft and Ftsum by Dco in S2 cells. Dco WT promotes phosphorylation of Ft. The Ftsum is less phosphorylated by Dco. (E) Efficacy of app and dlish dsRNAs in S2 cells. Both proteins are strongly reduced by cotransfection of dsRNA. (F) Ed:Ft:Flag recruits Dachs:GFP to cell–cell contacts in app and dlish depleted cells. (G) Ed:FtΔ6-C:Flag fails to recruit Dachs:GFP in app and dlish depleted cells. (H) Ed: FtΔN-6:Flag fails to recruit Dachs:GFP in app and dlish depleted cells. Scale bar, 5 µm (B and C) 1 µm (F–H). Yellow arrows in F–H indicate cell contacts. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Ft ICD recruits Dachs and influences its abundance.(A) CRISPR-Cas9 induced ftΔICD mutant. The target sequence (green line), PAM site (green box), and transmembrane domain (TM; blue letters) are shown. The resulting 4-bp deletion led to a premature stop codon after the transmembrane domain. The altered amino acids are shown in red letters. (B) App:YFP is increased in junctional puncta in ft61 mutant cells. (C) Dachs:GFP is increased at the junctional puncta in ft61 mutant clones. Mutant clones are marked by the absence of ubi-RFP. (D) Phosphorylation of wild-type Ft and Ftsum by Dco in S2 cells. Dco WT promotes phosphorylation of Ft. The Ftsum is less phosphorylated by Dco. (E) Efficacy of app and dlish dsRNAs in S2 cells. Both proteins are strongly reduced by cotransfection of dsRNA. (F) Ed:Ft:Flag recruits Dachs:GFP to cell–cell contacts in app and dlish depleted cells. (G) Ed:FtΔ6-C:Flag fails to recruit Dachs:GFP in app and dlish depleted cells. (H) Ed: FtΔN-6:Flag fails to recruit Dachs:GFP in app and dlish depleted cells. Scale bar, 5 µm (B and C) 1 µm (F–H). Yellow arrows in F–H indicate cell contacts. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Effects of the Ft ICD on Dachs and App. (A–C) Representative wing discs of the following genotypes stained with phalloidin: wild-type (A), ftG-rv/ftfd (B), and ftΔICD (C). Note that ftΔICD has a more severe overgrowth phenotype than ft null mutants. Panels B and C were stitched together because of their large size. (D) Localization of Dachs and Ds in ftΔICD mutant cells. Dachs:GFP expression is elevated and uniformly distributed around the junctional cortex, while Ds is only slightly elevated and localizes more normally at the junctions. Note that Dachs does not display the non-junctional puncta that are seen in ft null mutant cells (Fig. 1 J″). (E) Localization and abundance of App:YFP is not altered in ftΔICD mutant cells. (F) Dachs and App:YFP levels are elevated but localization to junctional puncta does not change in ftsum mutant cells. (G) App:YFP abundance also is elevated at junctional puncta in dco3 mutant cells. (H–M) Surface labeling of cell clones expressing HA:Ds (H and I), App:V5 (I, K, and M), or V5:Ft (J and L) together with the indicated tagged proteins. All clones show border non-expressing sister clones. (H) Dachs:GFP puncta colocalize with HA:Ds at clone boundaries. (I) Similarly, HA:Ds in puncta colocalizes with App:V5. (J) In contrast, V5:Ft puncta do not colocalize with Dachs:GFP at clone boundaries (yellow ellipses). (K) Similarly, Ft:GFP puncta do not co-stain for App:V5 at clone boundaries (yellow ellipses). Additionally, Ft:GFP fails to colocalize with App:V5 puncta at clone boundaries on the opposite side of cells (red ellipses). (L) In contrast to wild-type, in a dco3 mutant background, V5:Ft and Dachs:GFP colocalize in puncta at clone boundaries (yellow circles). (M) Similarly, in a dco3 mutant background, App:V5 and Ft:GFP extensively colocalize in puncta at clone boundaries (yellow ellipses). Scale bars, (A–C) 100 µm, (D–M) 5 µm.

Effects of the Ft ICD on Dachs and App. (A–C) Representative wing discs of the following genotypes stained with phalloidin: wild-type (A), ftG-rv/ftfd (B), and ftΔICD (C). Note that ftΔICD has a more severe overgrowth phenotype than ft null mutants. Panels B and C were stitched together because of their large size. (D) Localization of Dachs and Ds in ftΔICD mutant cells. Dachs:GFP expression is elevated and uniformly distributed around the junctional cortex, while Ds is only slightly elevated and localizes more normally at the junctions. Note that Dachs does not display the non-junctional puncta that are seen in ft null mutant cells (Fig. 1 J″). (E) Localization and abundance of App:YFP is not altered in ftΔICD mutant cells. (F) Dachs and App:YFP levels are elevated but localization to junctional puncta does not change in ftsum mutant cells. (G) App:YFP abundance also is elevated at junctional puncta in dco3 mutant cells. (H–M) Surface labeling of cell clones expressing HA:Ds (H and I), App:V5 (I, K, and M), or V5:Ft (J and L) together with the indicated tagged proteins. All clones show border non-expressing sister clones. (H) Dachs:GFP puncta colocalize with HA:Ds at clone boundaries. (I) Similarly, HA:Ds in puncta colocalizes with App:V5. (J) In contrast, V5:Ft puncta do not colocalize with Dachs:GFP at clone boundaries (yellow ellipses). (K) Similarly, Ft:GFP puncta do not co-stain for App:V5 at clone boundaries (yellow ellipses). Additionally, Ft:GFP fails to colocalize with App:V5 puncta at clone boundaries on the opposite side of cells (red ellipses). (L) In contrast to wild-type, in a dco3 mutant background, V5:Ft and Dachs:GFP colocalize in puncta at clone boundaries (yellow circles). (M) Similarly, in a dco3 mutant background, App:V5 and Ft:GFP extensively colocalize in puncta at clone boundaries (yellow ellipses). Scale bars, (A–C) 100 µm, (D–M) 5 µm.

To further identify the functions of the Ft ICD, we examined the effects of mutations that severely diminish the activity of the Ft ICD without affecting its extracellular interactions with Ds. ftsum and ft61 previously were identified as point mutations in the Ft ICD that cause overgrowth (Bossuyt et al., 2014; Bosch et al., 2014). Examining ftsum and ft61mutant clones, we found increased junctional accumulation of both Dachs and App in a punctate pattern (Fig. 6 F; and Fig. S4, B and C). These observations are in contrast to ftΔICD mutant clones where App levels were unaffected (Fig. 6 E) and Dachs was evenly distributed along the junctional cortex (compare Fig. 6, D–F). Clones of dco3 (discs-overgrown) cells, which also decrease the activity of the Ft ICD by blocking its phosphorylation (Sopko et al., 2009; Feng and Irvine, 2009), had a similar effect on App (Fig. 6 G). Interestingly, Dco fails to promote phosphorylation of Ftsum in S2 cells (Fig. S4 D), suggesting that phosphorylation of Ft decreases core complex accumulation at junctional puncta.

While the Ft ICD clearly has a role in reducing core protein levels, there is evidence that it recruits core proteins to the junction before degrading them. In fact, the Ft ICD forms a complex with core complex proteins including Dlish and App in S2 cells (Matakatsu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). To further examine this possibility, we made use of the planar polarized distribution of Ft and Ds in the imaginal epithelium, where Ft accumulates primarily at the proximal junctions of cells and Ds accumulates primarily at the distal edge. By examining mosaic clones of cells expressing tagged forms of Ds, Ft, Dachs, or App, we could discern at which junction, distal or proximal, these proteins accumulate in either wild-type or dco3 backgrounds. As previously suggested, we found that Ds and Dachs accumulated at the distal junctions of wild-type imaginal epithelial cells (Fig. 6 H), while Ft accumulated on the proximal side (Fig. 6, J and K; Mao et al., 2006; Rogulja et al., 2008; Brittle et al., 2012; Bosveld et al., 2012). Additionally, although App colocalized with Ds at distal junctions (Fig. 6 I), Ft did not colocalize with App on proximal junctions suggesting that App localized distally with the rest of the core complex (Fig. 6 K). In contrast, when similar clones were generated in the dco3 mutant background, Dachs and App colocalized with Ft at the proximal junctions (Fig. 6, L and M). Taken together, these observations suggest that like Ds, Ft recruits App and Dachs to the junctional cortex but prevents their retention by promoting their degradation.

Mapping functional domains in the Ft ICD

To further examine the functions of the Ft ICD, we employed the Echinoid S2 cell assay to examine the ability of Ed:Ft ICD fusions to recruit core complex components to the cell cortex (Fig. 7 A). Just as we observed with Ds ICD fusions, Ed:Ft:Flag strongly recruited Dachs, App, and Dlish (Fig. 7 A). Recruitment of Dachs did not appear to depend on other core complex proteins, as RNAi-mediated depletion of Dlish and App did not affect Dachs recruitment (Fig. 7 B). Similarly, we found that Dachs co-immunoprecipitated with the Ft ICD and that depletion of App and Dlish did not affect their co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) (Fig. 7 C). These results suggest that while the Ft ICD can recruit Dachs, Dlish, and App to the cortex of S2 cells, it likely cannot promote their degradation, presumably because other proteins essential for this process are not expressed or active in S2 cells.

Interactions between the Ft ICD and core complex proteins in S2 cells.(A) Recruitment of Dachs:V5, App:GFP, and Dlish:HA by Ed:Ft:Flag in S2 cells. All three proteins accumulate with the Ft ICD at cell contacts (yellow arrows). (B) Depletion of app and dlish by RNAi does not affect the ability of the Ft ICD to recruit Dachs:GFP (yellow arrows). (C) Co-IP experiments similarly show that the Ft ICD forms a complex with Dachs in S2 cells even when App and Dlish are depleted. (D) Structure cartoons of Ft ICD deletions designed to identify regions responsible for core complex recruitment in S2 cells. Functional domains and App and Dlish association sites from previous studies (Matakatsu and Blair, 2012; Misra and Irvine, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016) are also shown. TM, transmembrane domain; PH, planar cell polarity (PCP)-Hippo; ND, not determined. (E–G) S2 cell assays for recruitment of core complex proteins by different Ft ICD deletions. (E) Ed:FtΔPH-C:Flag fails to recruit core complex proteins to cell contacts. Ed:FtΔ6-C:Flag (F) as well as Ed:FtΔΝ-6:Flag (G) recruit Dachs:GFP and Dlish:HA (yellow arrows). (H) Co-IP experiments confirm the results in E–G. Scale bars, (A, B, and E–G) 5 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Interactions between the Ft ICD and core complex proteins in S2 cells.(A) Recruitment of Dachs:V5, App:GFP, and Dlish:HA by Ed:Ft:Flag in S2 cells. All three proteins accumulate with the Ft ICD at cell contacts (yellow arrows). (B) Depletion of app and dlish by RNAi does not affect the ability of the Ft ICD to recruit Dachs:GFP (yellow arrows). (C) Co-IP experiments similarly show that the Ft ICD forms a complex with Dachs in S2 cells even when App and Dlish are depleted. (D) Structure cartoons of Ft ICD deletions designed to identify regions responsible for core complex recruitment in S2 cells. Functional domains and App and Dlish association sites from previous studies (Matakatsu and Blair, 2012; Misra and Irvine, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016) are also shown. TM, transmembrane domain; PH, planar cell polarity (PCP)-Hippo; ND, not determined. (E–G) S2 cell assays for recruitment of core complex proteins by different Ft ICD deletions. (E) Ed:FtΔPH-C:Flag fails to recruit core complex proteins to cell contacts. Ed:FtΔ6-C:Flag (F) as well as Ed:FtΔΝ-6:Flag (G) recruit Dachs:GFP and Dlish:HA (yellow arrows). (H) Co-IP experiments confirm the results in E–G. Scale bars, (A, B, and E–G) 5 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Previous studies have revealed the domains in the Ft ICD responsible for PCP and growth control in vivo (Fig. 7 D, Matakatsu and Blair, 2012). To better understand how different Ft ICD domains function, we next examined their role in core complex recruitment (Fig. 7, D–H). Ed:FtΔPH-C:Flag, which lacks most of the ICD but retains a domain known to function in planar cell polarity (Matakatsu and Blair, 2012), failed to recruit any of the core complex proteins (Fig. 7 E). To narrow down regions necessary for recruitment, we generated two smaller deletions, one containing the Hippo N and C domains previously shown to be sufficient for growth control (Ed:FtΔ6-C:Flag) and one that deletes those domains but retains regions that modulate Hippo pathway function (Ed:FtΔN-6:Flag; Matakatsu and Blair, 2012; see Fig. 7 D). Interestingly, we found that either construct could recruit core complex proteins, consistent with previous work showing that both the M and C domains co-IP with App and Dlish in S2 cells (Fig. 7, F–H, Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016).

The relationship between Dachs, Dlish, and App

The different effects of loss of Ft and Ds on Dachs, Dlish, and App led us to further explore the relationship between these proteins. In the simplest case, these three proteins act together in a complex to promote growth. Consistent with this idea, Dachs interacts with Dlish in vitro, ectopic Dachs expression strongly stabilizes Dlish at the junctional cortex, and vice versa (Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). Additionally, the loss of App disrupts the cortical localization of Dachs and Dlish (Matakatsu and Blair, 2008; Matakatsu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). However, the relationship between Dachs or Dlish and App at the junctional cortex is less well studied. To address this, we expressed Dachs or Dlish and found that either promotes the accumulation of App at the junctional cortex (Fig. 8, A and C; and Fig. S5 A). In contrast, Dachs and Dlish levels changed only slightly in response to ectopic App expression, though they did have a more punctate appearance (Fig. 8, B and C; and Fig. S5 B). Thus, while ectopic Dachs or Dlish can promote App accumulation, ectopic App has little effect on Dachs or Dlish.

Dachs, App, and Dlish form a core complex to promote growth. (A) Ectopic Dachs expression causes increased App abundance. (B) Conversely, ectopic App expression does not increase Dachs abundance but does result in a more punctate appearance at the junctional cortex. (C) Comparison of apical protein levels of Dachs, Dlish, and App in response to ectopic expression of other core complex components. Y axis shows the mean intensity ratio of the posterior compartment (ectopic expression) to the anterior compartment (normal cells). ****P < 0.0001, ** 0.001 < P < 0.01, * 0.01 < P < 0.05 (two-tailed unpaired t test between each genotype). App:YFP in wild-type (n = 28), hh>dachs (n = 20), and hh>dlish (n = 16); Dachs:GFP in wild-type (n = 11), hh>dlish (n = 19), hh>app (n = 26); and anti-Dlish staining in wild-type (n = 12), hh>dachs (n = 15), and hh>app(n = 12). (D–K) Analysis of core complex components at the cell cortex in the absence of Ds and Ft. (D) Dachs and Dlish levels are highly elevated at the junctional cortex in ds ft mutant cells. (E) App:YFP abundance also is increased at junctions together with Dachs in ds ft clones. (F) In marked contrast to ds ft mutant cells (D″), Dlish is strongly reduced in ds ft dachs mutant cells. (G) App:YFP is less punctate but is junctionally localized in ds ft dachs mutant cells. (H) In the absence of dlish, Dachs abundance and localization are unaffected by loss of ds and ft. (I and J) In contrast, loss of ds and ft still causes increased Dachs and Dlish abundance at the junctional cortex in the absence of app (I), although the effect is smaller than when App is present (J). (K) Mutation in App catalytic domain has a similar effect on Dachs and Dlish accumulation as app null alleles (compare J and K). (L) Dachs:GFP localized to cell contacts also recruits App and Dlish in S2 cells (yellow arrows). Scale bars, 5 µm.

Dachs, App, and Dlish form a core complex to promote growth. (A) Ectopic Dachs expression causes increased App abundance. (B) Conversely, ectopic App expression does not increase Dachs abundance but does result in a more punctate appearance at the junctional cortex. (C) Comparison of apical protein levels of Dachs, Dlish, and App in response to ectopic expression of other core complex components. Y axis shows the mean intensity ratio of the posterior compartment (ectopic expression) to the anterior compartment (normal cells). ****P < 0.0001, ** 0.001 < P < 0.01, * 0.01 < P < 0.05 (two-tailed unpaired t test between each genotype). App:YFP in wild-type (n = 28), hh>dachs (n = 20), and hh>dlish (n = 16); Dachs:GFP in wild-type (n = 11), hh>dlish (n = 19), hh>app (n = 26); and anti-Dlish staining in wild-type (n = 12), hh>dachs (n = 15), and hh>app(n = 12). (D–K) Analysis of core complex components at the cell cortex in the absence of Ds and Ft. (D) Dachs and Dlish levels are highly elevated at the junctional cortex in ds ft mutant cells. (E) App:YFP abundance also is increased at junctions together with Dachs in ds ft clones. (F) In marked contrast to ds ft mutant cells (D″), Dlish is strongly reduced in ds ft dachs mutant cells. (G) App:YFP is less punctate but is junctionally localized in ds ft dachs mutant cells. (H) In the absence of dlish, Dachs abundance and localization are unaffected by loss of ds and ft. (I and J) In contrast, loss of ds and ft still causes increased Dachs and Dlish abundance at the junctional cortex in the absence of app (I), although the effect is smaller than when App is present (J). (K) Mutation in App catalytic domain has a similar effect on Dachs and Dlish accumulation as app null alleles (compare J and K). (L) Dachs:GFP localized to cell contacts also recruits App and Dlish in S2 cells (yellow arrows). Scale bars, 5 µm.

Dachs, App, and Dlish form a core complex. (A) App:YFP levels in hh>dlish:Flag at the junctional cortex. Dlish:Flag was expressed in the posterior compartment. App:YFP is increased with Dlish overexpression. (B) Dlish and Dachs:GFP in hh>app. Dlish and Dachs:GFP are enriched at junctional puncta with App overexpression. (C–I) Representative wing discs stained with phalloidin showing growth defects of the following genotypes: wild-type (C), app12-3 (D), dsUAO71ftfd; app12-3/dsUAO71ftG-rv; app12-3 (E), dlishY003 (F), dsUAO71ftfddlishY003/dsUAO71ftG-rvdlishY003 (G), dsUAO71ftfddlishY003; app12-3/dsUAO71ftG-rvdlishY003; app12-3 (H), and dsUAO71ftfd/dsUAO71ftG-rv (I). Overgrowth in ds ft is partly suppressed with app or dlish mutant. (J) Recruitment of cytoplasmic GFP by Ed:Flag:vhh4. GFP is recruited to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). (K) Membrane tethering GFP nanobody recruits Dachs:GFP, App, and Dlish to cell cortex. (L) Ed:Flag:vhh4 recruits App:GFP, Dachs, and Dlish to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). (M) Ed:Flag:vhh4 recruits Dlish:GFP, App and Dachs to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). (N) Membrane tethering GFP nanobody recruits App:GFP, Dachs:V5 as well as Dlish:HA to the cell cortex. (O) myr:Flag:vhh4 recruits Dlish:GFP, App, and Dachs:V5 to the cell cortex. Scale bars, 5 µm (A–B, L, and M), 100 µm (C–I), 1 µm (J, K, N, and O).

Dachs, App, and Dlish form a core complex. (A) App:YFP levels in hh>dlish:Flag at the junctional cortex. Dlish:Flag was expressed in the posterior compartment. App:YFP is increased with Dlish overexpression. (B) Dlish and Dachs:GFP in hh>app. Dlish and Dachs:GFP are enriched at junctional puncta with App overexpression. (C–I) Representative wing discs stained with phalloidin showing growth defects of the following genotypes: wild-type (C), app12-3 (D), dsUAO71ftfd; app12-3/dsUAO71ftG-rv; app12-3 (E), dlishY003 (F), dsUAO71ftfddlishY003/dsUAO71ftG-rvdlishY003 (G), dsUAO71ftfddlishY003; app12-3/dsUAO71ftG-rvdlishY003; app12-3 (H), and dsUAO71ftfd/dsUAO71ftG-rv (I). Overgrowth in ds ft is partly suppressed with app or dlish mutant. (J) Recruitment of cytoplasmic GFP by Ed:Flag:vhh4. GFP is recruited to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). (K) Membrane tethering GFP nanobody recruits Dachs:GFP, App, and Dlish to cell cortex. (L) Ed:Flag:vhh4 recruits App:GFP, Dachs, and Dlish to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). (M) Ed:Flag:vhh4 recruits Dlish:GFP, App and Dachs to cell–cell contacts (yellow arrows). (N) Membrane tethering GFP nanobody recruits App:GFP, Dachs:V5 as well as Dlish:HA to the cell cortex. (O) myr:Flag:vhh4 recruits Dlish:GFP, App, and Dachs:V5 to the cell cortex. Scale bars, 5 µm (A–B, L, and M), 100 µm (C–I), 1 µm (J, K, N, and O).

Although Ft and Ds affect the accumulation of Dachs, App, and Dlish at the junctional cortex, all three proteins accumulate at very high levels in the complete absence of ds and ft (Fig. 8, D and E). Moreover, loss of dachs is epistatic to the ds ft overgrowth phenotype (Fig. 1 D) and loss of either dlish or app partly suppresses this phenotype (Fig. S5, C–I), indicating that these proteins can function together, independent of Ds and Ft, to promote growth. Therefore, we reasoned that it should be easier to understand how these proteins regulate their cortical accumulation and promote growth in ds ft mutants.

We started by examining Dlish and App in ds ft dachs triple mutant cells. In this background, Dlish was severely reduced from apical cortex (Fig. 8 F), while App appeared more diffuse but still largely junctional (Fig. 8 G). Loss of Dlish blocked the strong accumulation of Dachs normally seen in ds ft mutant cells (Fig. 8 H). Taken together, these data suggest that Dachs and Dlish are strongly interdependent for their localization to the junctional cortex, while App can localize junctionally independent of Dachs and Dlish. However, we note that in ds ft dachs triple mutant cells App abundance is reduced relative to ds ft cells (compare Fig. 8, E and G), suggesting that levels of Dachs and Dlish can affect App.

To explore the role of App in junctional recruitment of Dachs and Dlish, we next examined these proteins in ds ft app triple mutant cells, either by removing ds and ft in an app mutant background (Fig. 8 I) or by removing app in ds ft mutant background (Fig. 8 J). Loss of app in ds ft background showed that App promotes accumulation of Dachs and Dlish at the junctional cortex in the absence of Ft and Ds (Fig. 8 J), while loss of ds and ft in an app mutant background clearly showed that App is not absolutely required for Dachs and Dlish accumulation (Fig. 8 I). These observations are consistent with previous evidence that App palmitoylates Dlish in vitro and promotes junctional localization of Dlish as well as Dachs in vivo since palmitoylation can promote the association of cytoplasmic proteins with the plasma membrane (Zhang et al., 2016). To test this more directly, we examined the effect of appDHHS, a CRISPR-engineered allele that blocks the palmitoyltransferase activity of App (Matakatsu et al., 2017) on Dachs and Dlish accumulation and found it to be indistinguishable from an app null allele (Fig. 8 K). These results suggest that App’s primary role is to promote the accumulation of Dachs and Dlish at the junctional cortex through its enzymatic function rather than a structural one.

To examine interactions between core complex components, we modified the Echinoid S2 cell assay to work with any GFP-tagged protein by fusing an anti-GFP nanobody (Caussinus et al., 2011) to the cytoplasmic domain of Echinoid (pMT-Ed:Flag:vhh4) or to a myristoylation sequence (UAS-myr:Flag:vhh4). Ed:Flag:vhh4 expressed in S2 cells promoted cell aggregation and strongly accumulated at cell contacts, as shown previously for other Ed protein fusions (Johnston et al., 2009), and recruited cotransfected GFP (Fig. S5 J). Ed:Flag:vhh4 strongly recruited Dachs:GFP to sites of cell contact, which in turn recruited cotransfected App and Dlish (Fig. 8 L). This result was confirmed using myr:Flag:vhh4 (Fig. S5 K). Additionally, Dlish and App could recruit other core complex components when they were tagged with GFP (Fig. S5, L–O) in S2 cells. Thus, interactions among Dachs, Dlish, and App help core complex formation in S2 cells.

Discussion

In this study, we have examined functional interactions between the ICDs of Ds and Ft and their effectors in growth control, a core complex consisting of Dachs, Dlish, and App. Previous work has suggested that while Ds functions to recruit core complex components to the cell cortex, thereby promoting growth, Ft promotes the degradation of Dachs, thereby repressing growth (Mao et al., 2006; Bosveld et al., 2012; Brittle et al., 2012). The results presented here revise this model in several important ways. First, we show that the core complex requires neither Ft nor Ds to associate with the junctional cortex and drive growth. Rather, Ft and Ds function coordinately to precisely restrict the amount and distribution of core complex components at the junctional cortex. Second, we show that in the absence of Ft, Ds functions to repress growth, apparently by removing core complex components from the junctional cortex. This finding is surprising and suggests that in some tissue context, Ds could play a significant role in restricting tissue growth. Third, we demonstrate that Ft also can recruit core complex components to the junctional cortex and that the stability and/or duration of these interactions is controlled by phosphorylation of the Ft ICD. Our structure/function analysis of Ft and Ds shows that they interact with core complex components via specific regions of their ICDs and that different regions of the Ds ICD function in parallel to promote growth. Taken together, our work reveals the underlying mechanisms by which Ds–Ft signaling represses a default “on” state that is driven by the inherent ability of core complex components to localize to the junctional cortex and promote growth.

The Dachs–Dlish–App core complex localizes at the junctional cortex to promote growth independent of Ft and Ds

Previous studies have found a strong correlation between the ability of Dachs to localize to the junctional cortex and its ability to promote tissue growth (Mao et al., 2006; Matakatsu and Blair, 2008; Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). The results presented here strongly support this model. In particular, we find that although overall Dachs abundance is indistinguishable between ft mutant tissues and ds ft mutant tissues, Dachs abundance at the junctional cortex and overall tissue growth are much greater in the latter than in the former. Additionally, the finding that Dachs, Dlish, and App all strongly accumulate at the junctional cortex in ds ft double mutant tissues demonstrates that core complex proteins accumulate at the junctional cortex independently of Ft and Ds.

To better understand how the core complex associates with the cell cortex, we examined interdependencies between these proteins in the absence of either Ft or Ds. Dachs and Dlish are highly interdependent—removing one results in almost complete loss of the other from the cell cortex—consistent with previous studies showing that Dachs and Dlish form a complex (Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). App has also been shown to form a complex with Dachs and Dlish and we showed here that Dachs and Dlish can recruit App in S2 cells, but its relationship with these proteins at the cortex appears less direct. For example, while ectopic expression of Dachs or Dlish causes increased accumulation of App, ectopic expression of App has little effect on either Dach or Dlish. Additionally, loss of App reduces but does not prevent increased accumulation of Dachs and Dlish caused by the absence of Ft and Ds. These observations are consistent with a model where App promotes the interaction of Dachs and Dlish with the cell cortex but does not contribute structural support for this interaction. Consistent with this idea, App can palmitoylate Dlish (Zhang et al., 2016) and we found that a mutation that specifically affects App enzymatic activity (appDHHS) affects Dachs and Dlish recruitment similar to an app null allele. Nonetheless, we consider App to be a member of the core complex because (1) co-IP and the Ed recruitment assays in S2 cells demonstrate that all three proteins can form a complex and (2) loss of Dachs severely diminishes App accumulation at the cell cortex (Matakatsu et al., 2017).

Ds effects on growth are context-dependent

Previous studies have highlighted the importance of Ds in stabilizing Dachs accumulation at the junctional cortex to promote growth (Bosveld et al., 2012; Brittle et al., 2012). While our findings are consistent with this model, they also show that in some contexts Ds can function to remove Dachs from the junctional cortex and as a result inhibit growth. This aspect of Ds function is clearly observed in the absence of Ft. As previously described (Hale et al., 2015), we observed that loss of Ft results in dramatic mislocalization of Ds, suggesting that Ds–Ft heterophilic interactions stabilize both proteins at the junctional cortex. We observed Ds and Dachs in non-junctional puncta in the absence of ft. These puncta were the consequence of Ds being unable to bind Ft on adjacent cells rather than a cell-autonomous effect of loss of Ft because ft mutant cells at the borders of clones, where Ds could interact with Ft expressed on adjacent wild-type cells, did not display non-junctional Ds or Dachs. Additionally, these puncta were absent in dsΔICDft cells, indicating that interaction with the Ds ICD is necessary to remove Dachs from the junctional cortex. Given that Ds is a transmembrane protein, it is possible that the non-junctional puncta are endocytic, but further studies will be required to address this.

What is most intriguing about these observations is that they provide a cell biological basis for the observation that while Ds promotes growth in the presence of Ft, it represses growth in the absence of Ft. While Ft is believed to play the major role in repressing Dachs activity and ft mutants display significant overgrowth, ds ft double mutants display much greater overgrowth. These observations raise the still unanswered question of whether, in some contexts, Ds might function to repress growth, independent of its role in activating Ft, during normal development. In relation to this, it is interesting that the opposing gradients of Ds and Fj expression in the wing result in less stable Ds-Ft binding in the proximal wing (Hale et al., 2015). Further studies will be required to elucidate to what extent Ds represses growth independent of Ft in development.

The Ft ICD can recruit the core complex to the cell cortex

Although Ft is well recognized to promote Dachs degradation, the underlying mechanistic basis of this function is poorly understood. Using the Echinoid S2 cell assay, we found that the Ft ICD functions similarly to the Ds ICD in having the ability to recruit core complex components to the cell cortex, consistent with previous co-IP experiments (Matakatsu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2016). We further found that while the Ft ICD can recruit Dachs in the absence of App and Dlish, deletion of either the M or C domain prevents recruitment of Dachs unless App and Dlish are present (Fig. 7, F and G; and Fig. S4, F–H). This result suggests that multiple Ft ICD domains could be involved in forming a complex between Ft and the core complex. Using endogenously tagged alleles and surface labeling protocols we found that in wing discs under normal conditions core complex components accumulate with Ds, as has been suggested previously, but do not accumulate with Ft. However, in the absence of Dco, which phosphorylates the Ft ICD and promotes its ability to degrade Dachs, core complex components accumulate with Ft at cell contacts. Thus, our results suggest that Ft degrades Dachs by first recruiting the core complex in a similar manner to Ds.

Functions of the Ds ICD