Ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs) are regularly oligomers containing between two and five binding sites for ligands. Neither in homomeric nor heteromeric LGICs the activation process evoked by the ligand binding is fully understood. Here, we show on theoretical grounds that for LGICs with two to five binding sites, the cooperativity upon channel activation can be determined in considerable detail. The main requirements for our strategy are a defined number of binding sites in a channel, which can be achieved by concatenation, a systematic mutation of all binding sites and a global fit of all concentration–activation relationships (CARs) with corresponding intimately coupled Markovian state models. We take advantage of translating these state models to cubes with dimensions 2, 3, 4, and 5. We show that the maximum possible number of CARs for these LGICs specify all 7, 13, 23, and 41 independent model parameters, respectively, which directly provide all equilibrium constants within the respective schemes. Moreover, a fit that uses stochastically varied scaled unitary start vectors enables the determination of all parameters, without any bias imposed by specific start vectors. A comparison of the outcome of the analyses for the models with 2 to 5 binding sites showed that the identifiability of the parameters is best for a case with 5 binding sites and 41 parameters. Our strategy can be used to analyze experimental data of other LGICs and may be applicable to voltage-gated ion channels and metabotropic receptors.

Introduction

The function of receptor proteins embedded in cell membranes is controlled by the binding of ligands to highly specific binding sites. Following ligand binding, the receptors exert conformational changes, highly specific as well, that evoke secondary responses in either the membrane or the cell interior. The most simple-structured ligands are ions, e.g., Ca2+ ions, but most ligands are organic molecules, including highly diverse neurotransmitters, or peptide- and proteohormones.

In ionotropic receptors, the binding of ligands controls the open probability of a pore for ions. To realize a pore structure, many of these receptors are oligomers composed of between two and five subunits. These subunits can be either identical or different, resulting in homomeric or heteromeric receptors, respectively. The oligomeric nature of the receptors is what causes the number of binding sites to be predominantly larger than one. The consequence is that the activation of the receptors is controlled by the binding of several ligands and the resulting conformational changes by each binding step influence each other, resulting in the phenomenon of cooperative receptor activation. Moreover, the cooperative conformational changes of the subunits feed back to the binding steps themselves in a reciprocal fashion (Colquhoun, 1998; Kusch et al., 2010). This complexity of processes severely limits quantitative studies on receptor activation.

For >50 yr, the allosteric Monod–Wyman–Changeux (MWC) model (Monod et al., 1965) has been used to interpret the activation of symmetric proteins composed of identical subunits. The applicability of this model is based on the simple elegance of the assumption that the subunits perform a joint “allosteric” conformational change of all subunits and that the equilibrium of this allosteric step is shifted in proportion to the number of ligands bound. To keep the models manageable, often-defined stoichiometric factors have been used. This leads to an extremely low number of required parameters for describing the activation process, one equilibrium association constant, one equilibrium constant for the allosteric conformational change, and one allosteric factor. The MWC model has been widely applied, including various ionotropic membrane receptors (e.g., GABAA receptors [Steinbach and Akk, 2019], nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [nAchRs; Lee and Sine, 2005], and also cyclic nucleotide-gated [CNG] channels [Goulding et al., 1994]) that are gated from the intracellular side. Moreover, the MWC model was extensively used for quantifying the oxygen binding in the tetrameric hemoglobin molecule (Eaton et al., 1999), though it is composed of different types of subunits, two α-chains and two β-chains in the case of adult hemoglobin (Fermi et al., 1984). However, the simplifying assumptions of using only a few parameters and fixed stoichiometries often severely limited detailed conclusions on the interaction of the binding sites and subunits in the framework of the MWC model, either for current measurements (Colquhoun, 1998) or binding measurements (Middendorf and Aldrich, 2017a, 2017b), even when applying state-of-the-art Bayesian strategies (Hines et al., 2014). For heteromeric receptors, the identifiability becomes even worse because any analysis would require more than one equilibrium association constant. Some remedy to overcome these problems in ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs) was to study subunit cooperativity by sophisticated single-channel analyses of burst activity, e.g., in homopentameric (Beato et al., 2007) or heteropentameric glycine receptors (GlyRs; Burzomato et al., 2004). An elegant alternative single-channel approach was to coexpress subunits with impeded binding sites and a second mutation in the pore to identify the subunit composition. This approach has been applied to homotetrameric CNG (Liu et al., 1998) and BK channels (Niu and Magleby, 2002), activated by intracellular cGMP and Ca2+, respectively.

Recently, we quantified activation gating in heterotetrameric CNG channels composed of two CNGA2 subunits, one CNGA4 and one CNGB1b subunit, by systematically impeding the four binding sites and subjecting the resulting 16 concentration–activation relationships (CARs) to a global fit analysis of 16 complex respective kinetic schemes (Schirmeyer et al., 2021). This approach allowed us to describe receptor activation by 32 equilibrium association constants for the 4 binding sites and 4 closed–open isomerization constants. Consistency of the subunit composition was reached by concatenating the subunits. The high degree of complexity could be managed by transposing the models to 4-D hypercubes. Due to multiple microscopic reversibilities and by equating the constants of the two A2 subunits, this fit required only 17 free parameters, which is, however, still a formidable number. Nevertheless, the precision of our fit was surprisingly high.

We therefore studied on theoretical grounds how this unexpectedly good identifiability of parameters could be reached (Benndorf et al., 2022). We showed that with this strategy indeed multiple functional parameters of the individual subunits can be determined because the constraints in this approach are sufficiently high. Furthermore, we employed a stochastic fit approach using scaled unitary (SU) start vectors to avoid any bias arising from a specific start vector. We showed that 23 parameters could be determined reliably, including 15 virtual equilibrium-association constants, 4 equilibrium constants for the closed–open isomerizations, and 4 disabling factors for the mutations. The 15 virtual equilibrium-association constants allowed us to determine the 32 equilibrium-association constants specific to the subunits of a tetrameric channel at each degree of ligand binding.

It was therefore intriguing to generalize our strategy to receptors with lower and higher numbers of binding sites. Biologically, the incidence of receptors with four subunits and four binding sites seems to dominate over the other constellations. For ionotropic receptors, typical tetrameric examples with four binding sites are AMPA receptors (Sobolevsky et al., 2009) or CNG channels (Li et al., 2017). Representative trimeric receptors with three binding sites are purinergic P2X receptors (Kawate et al., 2009) or acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs; Jasti et al., 2007). Pentameric ionotropic receptors belong mainly to the class of cys-loop receptors, including the families of nAchRs, GlyRs, and serotonin receptors (5HTRs). Many of these receptors are formed by two α-subunits and three other homolog subunits. For example, the classical nAChR of both the electric eel and the electric fish (Changeux et al., 1970; Miledi and Potter, 1971) is composed of two α-subunits, one β-subunit, one γ-subunit, and one δ-subunit (Weill et al., 1974; daCosta and Baenziger, 2013), forming only two binding sites between the adjacent subunits α and γ as well as α and δ. On the other hand, there are also homopentameric relatives with five binding sites, e.g., the α7 nAchR (McKay et al., 2007) or the α1 GlyR (Zhu and Gouaux, 2021). The key determinant for our analysis is not the number of subunits but the number of functional binding sites.

Herein, we elaborate for channels of known composition with two to five binding sites how promising it is to quantify receptor activation in great detail by our strategy, to impede the affinity of defined binding sites, and to globally fit all possible CAR combinations with either wild type or impeded binding sites by complex systems of coupled kinetic schemes. In other words, we empirically study the identifiability of multiple equilibrium constants for synthetic parameter sets by globally refitting multiple simulated CARs. We demonstrate that complex models with more binding sites and possible CARs can provide more accurate and precise results than simple models with less binding sites and possible CARs.

Materials and methods

Terminology and specification of models

To introduce the terminology used herein, we first consider the heteromeric allosteric (HA) model for the tetrameric channel as described previously (Schirmeyer et al., 2021) and which is also shown in its “systematic representation” in Fig. S1 A with respect to the number of binding sites. The model contains 32 different equilibrium association constants for the closed states, Kx, describing the binding of the ligand to the four binding sites for each occupation pattern of the other binding sites, and the 4 closed–open isomerization constants, Ex, for the transitions of the single to the quadruple liganded channel, thereby assuming that Ex is equal at an equal degree of liganding. Notably, due to microscopic reversibility, all equilibrium association constants for the open channel are implicitly given by the respective Kx of the closed channel and the two related Ex. At zero ligand, Po was set to the negligible value 10−5. A tetrameric HA model is termed in the following as the “HA4” model.

HA 4 model. (A) HA4 model in systematic representation. Equilibrium association constants for ligand binding, Kx (x = 1…32). For globally fitting, 16 such intimately coupled HA4 models with multiple combinations of mutated binding sites were combined with the comprehensive CHA4 model (Schirmeyer et al., 2021). Blue circles, ligand; white circles, empty binding site. The set of closed–open isomerizations on the bottom is valid for all HA4 models. For the single-, double-, and triple-liganded open channel the ligands are drawn below the channel cartoon to illustrate that there are 4, 6, and 4 options of occupancy (brackets). (B) HA4 model of A in cube representation. The closed–open isomerizations (Ex) were omitted for clarity. (C) 4-D model of A in cube representation with virtual equilibrium association constants, Zx, specifying the virtual transitions from state 0.

HA 4 model. (A) HA4 model in systematic representation. Equilibrium association constants for ligand binding, Kx (x = 1…32). For globally fitting, 16 such intimately coupled HA4 models with multiple combinations of mutated binding sites were combined with the comprehensive CHA4 model (Schirmeyer et al., 2021). Blue circles, ligand; white circles, empty binding site. The set of closed–open isomerizations on the bottom is valid for all HA4 models. For the single-, double-, and triple-liganded open channel the ligands are drawn below the channel cartoon to illustrate that there are 4, 6, and 4 options of occupancy (brackets). (B) HA4 model of A in cube representation. The closed–open isomerizations (Ex) were omitted for clarity. (C) 4-D model of A in cube representation with virtual equilibrium association constants, Zx, specifying the virtual transitions from state 0.

For the previous global fit analysis, mutational factors, fdx, were introduced for each mutated binding site, describing the reduction of the affinity. With all combinations of wild type and mutated binding sites, this led to maximally 16 CARs and corresponding 16 specific HA4 models. These 16 HA4 models build together the complex heterotetrameric allosteric CHA4 model which was finally subjected to a global fit. This terminology is used here throughout. The superscript indicates the number of binding sites.

Notably, the multifaceted network of binding steps in Fig. S1 A could be elegantly analyzed by transforming it into a 4-D hypercube (Fig. S1 B) and introducing 15 independent virtual equilibrium association constants, Zx (Fig. S1 C), determining the 32 Kx by simple ratios (Schirmeyer et al., 2021). This representation of a model will be termed herein as “cube representation” and will also be used for channels with two to five dimensions.

Because the number of binding sites can deviate from the number of subunits and to generalize our approach, we categorize the LGICs herein by the actual number of binding sites and not by the number of actual subunits. Hence, the superscript at the end indicates the number of actual binding sites. For example, a tetrameric CNG channel with four binding sites would be described by a CHA4 model and a pentameric nAchR with two binding sites by a CHA2 model.

Computation of the models

For the LGICs with two to five binding sites, four types of respective HA models are considered herein. To keep track, we use the nomenclature “HAx” model, where x denotes the number of ligands. To include the effects of the mutations, each mutation generates its own HAx model for each CAR. The number of HAx models included in a complex CHAx model is given by nCAR,max (Eq. 21) and is found to be 4, 8, 16, and 32 for x = 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

For all computations, we assumed that microscopic reversibility (Colquhoun and Hawkes, 1995) is obeyed, resulting in the ligand binding to a defined number of independent equilibrium constants on which the others depend (Colquhoun et al., 2004).

In our previous analysis on heteroterameric channels, we eased the considerations by interpreting the 16 closed states of our HA4 models as corners of a 4-D hypercube in which the transitions, specified by the 32 Kx, form the 32 edges (Fig. S1 B; Benndorf et al., 2022).

Herein, we essentially follow this logic: given state 0, the 4-D hypercube defines 15 virtual equilibrium association constants (violet lines Z1–Z15 in Fig. S1 C), which allow the computation of the 32 Kx by respective ratios of two Zx (see below). Microscopic reversibility is directly obeyed. For disabling the binding sites, we assume that the affinity of a binding site is reduced by a factor fdx < 1 (x = 1…4). As in our previous approach, the fdx factors were considered to affect solely the affinity at a binding site for the ligand. For the equilibrium constants of the closed–open isomerizations, Ex (x = 1…4; Fig. S1 A, bottom), it is assumed that they are equal at an equal degree of liganding and independent of where the binding site is occupied. E0 is set to the negligible value of 10−5. The total number of free parameters for the global fit of the 16 concatamers is then 15 + 4 + 4 = 23.

To explain the rationale of the analysis, it is useful to skip to our earlier nomenclature. The closed state 0 is then termed C0000, where the four zeros tell that no binding site is occupied. The other 15 closed states in the 4-D hypercube are then given by Cijkl, where i, j, k, and l can be either 0 (empty) or 1 (occupied).

The ligand concentration L has the power of the sum of the indices α = i + j + k + l, corresponding to the number of bound ligands. The factors of disabling by the mutational factor fdu (u = 1…4) of the four binding sites have the exponents γ1 to γ4, which are also either 0 or 1. An exponent is 1 if the binding site u is mutated and has bound a ligand. Otherwise, the exponent is 0.

This equation was used for both simulating the data points and computation of the CARs by the respective model in the fits.

Since the formula requires a value for E0 though no detectable Po was assumed with no ligand bound, we set E0 generally to the negligible value of 10−5.

Simulation of data points

Global fit

The nlinfit routine of the Matlab software was used to globally fit the CHA models, operating with an iterative least square estimation. The maximum iteration number was set to 100. The routine provides the fit parameters, xi (Ex, Zx, fdx), the covariance matrix, CovEZfd, with the elements σij of which the main diagonal gives, with i = j, the values of the variances and standard deviations and σi of the fit parameters, respectively. The Zx allow to compute all respective equilibrium association constants, Kx, by simple ratios (Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4).

These relative standard deviations are useful for comparing the uncertainty of different parameters. Here, two different measures are used to quantify the uncertainties of the parameters in the fit, imprecision and inaccuracy (Benndorf et al., 2022).

Imprecision

The term precision of a parameter xi specifies its quality, without knowing that the parameter has been determined correctly. Consequently, the term imprecision, ipri, denotes a statistical variability of a parameter with respect to its determined mean. Hence, ipri is given by σi,rel.

Inaccuracy

Correlation matrices

Stochastic procedure to identify best fits for a given set of data points

Computation times

Computing 1,000 of the most challenging fits with stochastically varied scaled unitary start vectors lasted about 10 min for the least complex CHA2 model and about 300 min for the most complex CHA5 model (Fujitsu Lifebook U series; vPRO i7).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the structure of the HA4 model in systematic representation and as 4-D hypercube as published earlier. Fig. S2 illustrates by bar graphs how the fit parameters were set for the HA2 to HA5 model. Fig. S3 shows the inaccuracy and imprecision of the parameters for 1,000 global fits of the CHA2 to CHA5 model using a start vector with the true values. Fig. S4 provides color-coded correlation matrices for the CHAx models. Fig. S5 illustrates the effects of mutational factors on the identifiability of Ex for the CHAx models. Fig. S6 shows the effects of weakening the mutational factors on the identifiability of the Zx for the CHAx models. Fig. S7 shows plots of the inaccuracy and imprecision of the parameters for equal SU start vectors with stochastically varied elements. Fig. S8 illustrates successfulpΔMSE fits with different stochastically varied SU start vectors and stochastically varied elements. Fig. S9 provides histograms of successfulpΔMSE fits with different SU vectors and stochastically varied elements. Fig. S10 shows the fit parameters determined with different SU vectors and stochastically varied elements and compares them with the true parameters. Fig. S11 illustrates the inaccuracy and imprecision of the parameters for successfulpΔMSE fits with different SU vectors and stochastically varied elements. Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4 provide the generation of Kx from Zx in the HA2 to HA5 model, respectively. In the supplemental text, the algorithms for specifying the parameters for the CHAx models are described.

Results

Channels to be analyzed

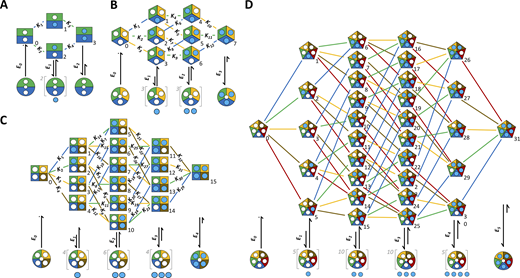

HAxmodels in systematic representation. Blue circles, ligand; white circles, empty binding site. The set of closed–open isomerizations on the bottom is valid for all HAx models at an equal degree of liganding. For open channels with incomplete occupation of the binding sites, the ligands are drawn below the channel cartoon to illustrate that there is more than one option for occupancy. The Kx indicate the equilibrium association constants corresponding to Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4. (A) HA2 model. (B) HA3 model. (C) HA4 model. (D) HA5 model. In the HA5 model, the Kx were omitted for clarity but are provided by Table S4.

HAxmodels in systematic representation. Blue circles, ligand; white circles, empty binding site. The set of closed–open isomerizations on the bottom is valid for all HAx models at an equal degree of liganding. For open channels with incomplete occupation of the binding sites, the ligands are drawn below the channel cartoon to illustrate that there is more than one option for occupancy. The Kx indicate the equilibrium association constants corresponding to Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4. (A) HA2 model. (B) HA3 model. (C) HA4 model. (D) HA5 model. In the HA5 model, the Kx were omitted for clarity but are provided by Table S4.

Closed states of HA x models in cube representation. The symbols correspond to those in Fig. 1. Each model in systematic representation in Fig. 1 was translated into the cube representation. The model structure follows a respective change of the dimension nD. (A) HA2 model containing four states arranged in a 2-D square. (B) HA3 model containing eight states arranged in a 3-D cube. (C) HA4 model containing 16 states arranged in a 4-D hypercube. (D) HA5 model containing 32 states arranged in a 5-D hypercube. The Kx are indicated apart from the HA5 model where they were omitted for clarity.

Closed states of HA x models in cube representation. The symbols correspond to those in Fig. 1. Each model in systematic representation in Fig. 1 was translated into the cube representation. The model structure follows a respective change of the dimension nD. (A) HA2 model containing four states arranged in a 2-D square. (B) HA3 model containing eight states arranged in a 3-D cube. (C) HA4 model containing 16 states arranged in a 4-D hypercube. (D) HA5 model containing 32 states arranged in a 5-D hypercube. The Kx are indicated apart from the HA5 model where they were omitted for clarity.

The respective values are 3, 7, 15, and 31 (Fig. 3). The nZx values also tell directly the number of independent parameters in a fit for ligand binding. The Zx define all respective Kx (Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4).

Virtual equilibrium association constants for HA x models in cube representation. The virtual equilibrium association constants, Zx, are indicated by the violet lines running from state 0 to the other states. The number of Zx in a model defines directly the number of independent parameters for ligand binding. (A) HA2 model. (B) HA3 model. (C) HA4 model. (D) HA5 model. The Zx are indicated apart from the HA5 model where they were omitted for clarity. The dimensions of the Zx are M−1, M−2, M−3, M−4, or M−5 for the occupation of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 binding sites, respectively.

Virtual equilibrium association constants for HA x models in cube representation. The virtual equilibrium association constants, Zx, are indicated by the violet lines running from state 0 to the other states. The number of Zx in a model defines directly the number of independent parameters for ligand binding. (A) HA2 model. (B) HA3 model. (C) HA4 model. (D) HA5 model. The Zx are indicated apart from the HA5 model where they were omitted for clarity. The dimensions of the Zx are M−1, M−2, M−3, M−4, or M−5 for the occupation of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 binding sites, respectively.

A plot of the ratio np/nCARmax as a function of the dimension nD shows a decrease in the higher dimensions (Fig. 4). Hence, if all possible CARs are included, this suggests that the chances for a reasonable fit are poorest in the 2-D case and largest in the 5-D case, i.e., a fit with seven parameters would be less promising than that with as much as 41 parameters, respectively, although it is a priori not trivial to conclude this because of the different structures of the models. We therefore investigated the outcome of global fits with the CHA2 through CHA5 model systematically using the maximum numbers of CARs given by Eq. 21.

Relation between number of parameters and available CARs in CHA x models. The ratio of the number of parameters, np, to the maximum number of available CARs, nCARmax, is plotted versus the number of dimensions, nD, i.e., the number of binding sites.

Relation between number of parameters and available CARs in CHA x models. The ratio of the number of parameters, np, to the maximum number of available CARs, nCARmax, is plotted versus the number of dimensions, nD, i.e., the number of binding sites.

Specification of theoretical fit parameters for CHAx models

Comparison of CHA models with different structures and number of ligands requires the use of related theoretical parameters. These theoretical parameters were generated in some relation to the previous parameters for the heterotetrameric CNG channels (Schirmeyer et al., 2021; Benndorf et al., 2022). Their exact derivation is described in the supplemental text at the end of the PDF, and their values are illustrated in Fig. S2.

Setting the theoretical fit parameters. Theoretical parameters were created on the basis of related real data on heterotetrameric CNG channels (Schirmeyer et al., 2021; Benndorf et al., 2022; for details see Eqs. 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, and 32 in the supplemental text at the end of the PDF). The set parameters are termed throughout as true parameters, xi,tr. The saturated colors indicate parameters at respective upper and lower borders and the shaded colors parameters with interpolated values.

Setting the theoretical fit parameters. Theoretical parameters were created on the basis of related real data on heterotetrameric CNG channels (Schirmeyer et al., 2021; Benndorf et al., 2022; for details see Eqs. 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, and 32 in the supplemental text at the end of the PDF). The set parameters are termed throughout as true parameters, xi,tr. The saturated colors indicate parameters at respective upper and lower borders and the shaded colors parameters with interpolated values.

For Ex, we set the value of the single-liganded channel to 10−1 and that of the fully liganded channel to 102, i.e., we assumed that maximal liganding causes a 1,000-fold increase of Ex with respect to E1. The intermediate Ex values were set equidistantly on a logarithmic scale between E1 and the maximum Ex according to Eq. 23.

For fdx, the situation is grossly analogous. fd1 was set to 10−4 and that of the maximally impeded binding site was set to 10−2, resulting in a maximum difference between the binding sites of 100. Again, we set the intermediate fdx values equidistantly on a logarithmic scale between fd1 and the maximum fdx according to Eq. 24.

For Zx, the situation is more complex because the number of Zx, nZx, rises exponentially according to Eq. 19 and the options at an equal degree of liganding follow binomial statistics. The generation of the parameters are described by Eqs. 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, and 34.

While the values for the Ex and fdx differ substantially for different x, quite similar to values found for heteromeric CNG channels (Schirmeyer et al., 2021; Benndorf et al., 2022), we chose a more challenging condition for the Zx values to differ at an equal degree of liganding by only one order of magnitude. Moreover, they also superimpose significantly for different degrees of liganding.

Simulating the CARs

With these equilibrium constants, we computed families of data points with the CHA2, CHA3, CHA4, and CHA5 model by including the respective maximum numbers of CARs and using Eq. 8 (Fig. 5). The noise was set to 0.25 (see Materials and methods), a value resembling the scatter in reasonable experimental measurements.

Simulation of CARs with CHA x models. Using the equilibrium constants illustrated in Fig. S2, we computed the full set of CARs (Eq. 21) with the CHA2 to the CHA5 model. Noise 0.25 (see Materials and methods). For the specified parameters, the wild type and maximally mutated channels span a similar concentration range. The CARs with intermediate degrees of mutations fill the range between the two extreme CARs and develop characteristic shapes and, thus, constraints for the fit.

Simulation of CARs with CHA x models. Using the equilibrium constants illustrated in Fig. S2, we computed the full set of CARs (Eq. 21) with the CHA2 to the CHA5 model. Noise 0.25 (see Materials and methods). For the specified parameters, the wild type and maximally mutated channels span a similar concentration range. The CARs with intermediate degrees of mutations fill the range between the two extreme CARs and develop characteristic shapes and, thus, constraints for the fit.

According to the set parameters for respective wild type and maximally mutated channels, these “extreme” CARs cover a similar concentration range and the CARs with intermediate degrees of mutations fill the range between the two extreme CARs, thereby developing characteristic shapes.

We first compared the fitted parameters, xi, with the true parameters, xi,tr. To increase the robustness of the result, we repeated the global fit 1,000 times, thereby generating the data points for each fit de novo according to Eq. 9. Despite taking the true values as the start vector, a portion of the fits failed, as identified by at least one negative parameter, a physically senseless result. In the following, all remaining non-failing fits with only positive parameters are termed successfulp fits (Fig. 6 A), of which it is a priori not clear if they have run to the correct minimum or to another minimum. The diagram in Fig. 6 A suggests that models with higher numbers of binding sites have more constraints than fits with lower number of binding sites.

Success rate and goodness of fits with the CHA x models. 1,000 fits with de novo generated data points each were performed with each model. The start vector consisted of the true values. The value n indicates the number of successfulp fits out of 1,000 fits. (A)n of successfulp fits out of 1,000 fits. (B) Mean inaccuracy, miacnp,n, computed over all np parameters according to Eq. 15. (C) Mean imprecision, miprnp,n, computed over all np parameters according to Eq. 12. (D) Mean absolute correlation coefficients (see Materials and methods). The influence of the different signs was abolished by taking their absolute values. Also, the “1” of the main diagonal was taken out. n specifies the number of included successful fits.

Success rate and goodness of fits with the CHA x models. 1,000 fits with de novo generated data points each were performed with each model. The start vector consisted of the true values. The value n indicates the number of successfulp fits out of 1,000 fits. (A)n of successfulp fits out of 1,000 fits. (B) Mean inaccuracy, miacnp,n, computed over all np parameters according to Eq. 15. (C) Mean imprecision, miprnp,n, computed over all np parameters according to Eq. 12. (D) Mean absolute correlation coefficients (see Materials and methods). The influence of the different signs was abolished by taking their absolute values. Also, the “1” of the main diagonal was taken out. n specifies the number of included successful fits.

From these successfulp fits, the means for each parameter and their standard deviation were computed and plotted together with the respective true parameter in bar graphs (Fig. 7). The mean relative standard deviations σi,rel for each parameter of 1,000 fits (ipri,1000; Eq. 11) are plotted below each bar graph as a fraction of 1 to illustrate the relative errors. The following conclusions can be drawn: (1) the global fits found with all models for each mean parameter is a minimum near xi,tr; (2) the errors obtained from these fits were generally fairly small, but those of the last Ex as well as Z1 and the last Zx exceeded the others; (3) particularly well determined are the mutational factors of the binding sites, fdx; and (4) the xi are apparently best determined with the CHA5 model and worst with CHA2 model.

Comparison of fit parameters with true parameters as a start vector. In the bar graphs, the fitted parameters, xi, are compared with the true parameters, xi,tr. For each model, 1,000 fits were performed. As a starting vector, the true parameters were used (gray bars). The data points were de novo generated for each fit. Despite taking the true values as the start vector, part of the fits failed. The number of successful fits is given by n. Means and standard deviations of these fits are shown. The mean relative standard deviations σi,rel of 1,000 fits, ipri,1000 (Eq. 11), below the bar graphs indicate the relative errors of each parameter. The ochre lines and numbers right specify the overall ipri,1000 value for each model and the dashed red line the level of 0.1, i.e., the 10% error.

Comparison of fit parameters with true parameters as a start vector. In the bar graphs, the fitted parameters, xi, are compared with the true parameters, xi,tr. For each model, 1,000 fits were performed. As a starting vector, the true parameters were used (gray bars). The data points were de novo generated for each fit. Despite taking the true values as the start vector, part of the fits failed. The number of successful fits is given by n. Means and standard deviations of these fits are shown. The mean relative standard deviations σi,rel of 1,000 fits, ipri,1000 (Eq. 11), below the bar graphs indicate the relative errors of each parameter. The ochre lines and numbers right specify the overall ipri,1000 value for each model and the dashed red line the level of 0.1, i.e., the 10% error.

To further characterize the global fits, we determined for the successfulp fits the uncertainties of the parameters by two measures, the inaccuracy, the deviation of the fitted parameters from the respective true values, and the imprecision, the deviation of the fitted parameter from the determined mean (see Materials and methods). We first consider the inaccuracy that is only accessible in simulated data as used herein. The inaccuracy for the CHA5 model with np = 41 parameters is approximately similarly good as that for the CHA4 model and CHA3 model with np = 23 and np = 13 parameters, respectively, and all of these fits seem to be superior compared with the fit with the CHA2 model with np = 7 parameters (Fig. S3 A). We also compared the imprecision (Fig. S3 B), a measure that would be accessible also for real experimental data. We considered if the somewhat surprising higher goodness of the fits for the channels with the higher parameter numbers can also be obtained from this measure of uncertainty. The diagrams for the four channels confirm the above result, i.e., the channels with more binding sites provide an apparently lower imprecision than the channels with less binding sites.

Inaccuracy and imprecision of the parameters in global fits of CHA x models. (A) Inaccuracy. The mean inaccuracy for each parameter xi, iaci,n, was computed by Eq. 14. The number of included successfulp fits, n, is indicated in brackets. (B) Imprecision. The mean imprecision for each parameter xi, ipri,n, was computed by Eq. 11. The diagrams confirm that the channels with more binding sites provide a lower imprecision than the channels with less binding sites.

Inaccuracy and imprecision of the parameters in global fits of CHA x models. (A) Inaccuracy. The mean inaccuracy for each parameter xi, iaci,n, was computed by Eq. 14. The number of included successfulp fits, n, is indicated in brackets. (B) Imprecision. The mean imprecision for each parameter xi, ipri,n, was computed by Eq. 11. The diagrams confirm that the channels with more binding sites provide a lower imprecision than the channels with less binding sites.

We next addressed the question of whether the fact that some of the few parameters are apparently less well-determined than the majority of the others can be attributed to special correlations among the parameters. To this end, we computed the matrix of the correlation coefficients from the covariance matrix provided by the fits of all CHA models (see Materials and methods) and plotted them in false colors (Benndorf et al., 2022) to identify conspicuous specific correlations among parameters (Fig. S4). The result was that the parameters with the highest imprecision, the last Ex and Zx, show a pronounced negative correlation. But there are also a few other relevant negative correlations between the second to last Ex and Zx as well as some positive correlations for both the CHA4 and the CHA5 model between high Zx. Nevertheless, the most relevant result is that non-correlated parameters (colored yellow) dominate for both the CHA4 and the CHA5 model.

Color-coded correlation matrices for CHA x models. The correlation coefficients were calculated from the covariance matrices (see Materials and methods) and plotted by false colors (see legend at the bottom; Benndorf et al., 2022). Few parameters are strongly correlated, either positive or negative. Notably, non-correlated parameters (colored yellow) dominate most for the CNA5 and least for the CNA2 model. For further explanation, see Simulating the CARs in the Results.

Color-coded correlation matrices for CHA x models. The correlation coefficients were calculated from the covariance matrices (see Materials and methods) and plotted by false colors (see legend at the bottom; Benndorf et al., 2022). Few parameters are strongly correlated, either positive or negative. Notably, non-correlated parameters (colored yellow) dominate most for the CNA5 and least for the CNA2 model. For further explanation, see Simulating the CARs in the Results.

Finally, we computed for the successfulp fits respective overall-measures for all parameters of a fit, of which each is already the mean of n fits as specified above. For the inaccuracy and the imprecision, we calculated the overall means, miacnp,n and miprnp,n (Eqs. 15 and 12, respectively; Fig. 6, B and C). In the case of the correlation coefficients, we abolished the influence of different signs by taking the absolute values and taking out the ones of the main diagonal, yielding the mean absolute correlation coefficientsn (Fig. 6 D).

These diagrams demonstrate that the chances to determine the parameters in the respective models are best in the models with the higher number of binding sites. To come back to our initial question, the increasing number of constraints by the increased number of CARs in channels with more binding sites overbalances the effect introduced by the increased number of parameters. The most important result, however, is that it seems to be indeed realistic to analyze a complex system with 41 parameters, as given by the CHA5 model, if only all CAR combinations with systematically impeded binding sites are available and if selecting the successfulp fits for the analysis.

Relation between mutational effects and parameter identifiability

Effects of mutational factors on parameter identifiability. (A) Scheme illustrating the weakening steps for all fdy where y runs from 1 to nD. Using Ex and Zx illustrated in Fig. S2, the mutational factors fdy were systematically reduced in 10 steps (weakening factor w = 10…0), providing weakening mutational factors wfdy according to Eq. 21. w = 10 specifies 10fdy the maximum mutational effect, as shown in Fig. S2, whereas 0fdy specifies wild type channels with no weakening effect. (B) Plot of the number of successfulp fits as function of w. After performing 250 fits each, the number of successfulp fits was counted by eliminating all fits with physically senseless negative parameters. A weaker mutational effect decreases the number of successfulp fits. At sufficiently strong mutational effects, the CHA4 and CHA5 model are superior over the CHA2 model. (C) Plot of the mean imprecision miprnp,n as function of w. The mean imprecision (Eq. 12) over all parameters is lower for the CHA4 and CHA5 model than for the CHA3 model and, particularly, for the CHA2 model.

Effects of mutational factors on parameter identifiability. (A) Scheme illustrating the weakening steps for all fdy where y runs from 1 to nD. Using Ex and Zx illustrated in Fig. S2, the mutational factors fdy were systematically reduced in 10 steps (weakening factor w = 10…0), providing weakening mutational factors wfdy according to Eq. 21. w = 10 specifies 10fdy the maximum mutational effect, as shown in Fig. S2, whereas 0fdy specifies wild type channels with no weakening effect. (B) Plot of the number of successfulp fits as function of w. After performing 250 fits each, the number of successfulp fits was counted by eliminating all fits with physically senseless negative parameters. A weaker mutational effect decreases the number of successfulp fits. At sufficiently strong mutational effects, the CHA4 and CHA5 model are superior over the CHA2 model. (C) Plot of the mean imprecision miprnp,n as function of w. The mean imprecision (Eq. 12) over all parameters is lower for the CHA4 and CHA5 model than for the CHA3 model and, particularly, for the CHA2 model.

We first counted the number of successfulp fits (Fig. 8 B). As expected, for all CHAx models, a weaker mutational effect causes a lower number of successfulp fits. Moreover, at stronger mutational effects (w→10), the CHA4 and CHA5 models produce better success than the CHA2 model. The CHA3 model is intermediate.

When calculating the corresponding means of the imprecision (Eq. 12) over all parameters, it is also lower for the CHA4 and CHA5 model than the CHA3 model and even much lower than for the CHA2 model (Fig. 8 C). Moreover, the results show that with the selected set of parameters, for w a value of 7 or larger is a good idea, resulting for 7fd1 and 7fdmax to a 631- and 25-times reduced affinity, respectively.

We next considered how the different degrees of mutational effects affect the Ex and Zx individually. Regarding Ex, it is evident that there is a pronounced reduction of the imprecision from the CHA2 to the CHA4 or CHA5 model, telling that the lower imprecision (higher precision) of fits with the more complex models, and respectively more parameters, are indeed better determined (Fig. S5). It is also notable that E1 and Emax are some more uncertain than the respective intermediate Ex. For Zx, the results are basically similar. Again, there is a pronounced reduction of the imprecision from the CHA2 to the CHA4 or CHA5 model. Also, Z1 and Zmax are more uncertain than the respective intermediate Zx (Fig. S6). Together, these results show that the reduced overall imprecision (Fig. 6 C) of fits with the more complex models, and respectively more parameters, is caused by a lower imprecision of both Ex and Zx.

Effects of mutational factors on the identifiability of E x . Data are provided for the CHA2 to the CHA5 model. At the top, the schemes for the weakening steps of all fdx are indicated. The imprecision of Ex decreases from the CHA2 to the CHA4 or CHA5 model. Also, E1 and Emax (green) are more uncertain than the respective intermediate Ex (gray).

Effects of mutational factors on the identifiability of E x . Data are provided for the CHA2 to the CHA5 model. At the top, the schemes for the weakening steps of all fdx are indicated. The imprecision of Ex decreases from the CHA2 to the CHA4 or CHA5 model. Also, E1 and Emax (green) are more uncertain than the respective intermediate Ex (gray).

Effects of mutational factors on the identifiability of Z x . Data are provided for the CHA2 to the CHA5 model. At the top the schemes for the weakening steps of all fdx are indicated. The imprecision of Zx decreases from the CHA2 to the CHA4 or CHA5 model. As with Ex, Z1, and Zmax (green) are more uncertain than the respective intermediate Zx (gray). For clarity, the actually discrete points for the intermediate Zx were omitted.

Effects of mutational factors on the identifiability of Z x . Data are provided for the CHA2 to the CHA5 model. At the top the schemes for the weakening steps of all fdx are indicated. The imprecision of Zx decreases from the CHA2 to the CHA4 or CHA5 model. As with Ex, Z1, and Zmax (green) are more uncertain than the respective intermediate Zx (gray). For clarity, the actually discrete points for the intermediate Zx were omitted.

Searching the global minimum without the bias of a specific start vector

Our approach so far allowed us to substantiate that the parameter identifiability for the CHA5 model was better than that for the CHA2 model and at least as good as that for the CHA3 and CHA5 model. Besides the fact that this situation does not match the situation of an experimenter, who, of course, does not know any true values, our approach could have been strongly biased by using the true values as a start vector, certainly promoting convergence to the minimum with the true parameters.

To match the requirements of an experimenter, the logic of the approach is now turned around: a set of data points for the respective maximum number of CARs is viewed as given and an approach is developed to analyze the respective data of the CHA2 to CHA5 model.

To this end, we followed our previous strategy of using SU vectors, varying over a wide range, and vary each of its elements stochastically (Benndorf et al., 2022; Schirmeyer et al., 2022). If sufficiently many successful fits with parameters providing the same minimum can be obtained and the nonsuccessful fits can be reliably eliminated, any bias introduced by a specific start vector can be ruled out.

We varied the SU vector from 10−6 to 103, i.e., over nine orders of magnitude, resulting in 19 SU vectors (Fig. 9 A). As a stochastic factor, we used A = 100, i.e., each element of the SU vector was stochastically varied in the range of 10−2 to 102 of its value. In total, this covers the huge range of 13 orders of magnitude for the stochastically varied SU start vector. The noise factor was again 0.25 and 1,000 fits were performed for nCAR,max CARs.

Successful pΔMSE fits with equal SU start vector and stochastically varied elements. (A) Scheme of the stochastic variation of the start vector. SU start vectors extended over the range from 10−6 to 103 yielding 19 SU vectors. The SU vectors were stochastically varied by the factor A = 102. 1,000 fits were performed for each SU start vector. The noise factor was 0.25 and 1,000 fits were performed for each SU vector. (B) After selection of successfulp fits, a second selection algorithm for fits was applied. Using the MSEx values provided by the fit routine, the minimum MSEx value, Min(MSEx), was identified in the 1,000 fits and the difference of each MSEx to the Min(MSEx) was calculated, yielding ΔMSEx. ΔMSEx values were sorted, starting with the smallest, and plotted for x > 0 on a logarithmic scale. A threshold was set at 10−10 (red dashed lines) to identify all fits in close proximity of ΔMSE1 = 0. All values below 10−10 indicate successfulpΔMSE fits. For all four models, the sums of all obtained successfulpΔMSE fits out of 19,000 fits are indicated.

Successful pΔMSE fits with equal SU start vector and stochastically varied elements. (A) Scheme of the stochastic variation of the start vector. SU start vectors extended over the range from 10−6 to 103 yielding 19 SU vectors. The SU vectors were stochastically varied by the factor A = 102. 1,000 fits were performed for each SU start vector. The noise factor was 0.25 and 1,000 fits were performed for each SU vector. (B) After selection of successfulp fits, a second selection algorithm for fits was applied. Using the MSEx values provided by the fit routine, the minimum MSEx value, Min(MSEx), was identified in the 1,000 fits and the difference of each MSEx to the Min(MSEx) was calculated, yielding ΔMSEx. ΔMSEx values were sorted, starting with the smallest, and plotted for x > 0 on a logarithmic scale. A threshold was set at 10−10 (red dashed lines) to identify all fits in close proximity of ΔMSE1 = 0. All values below 10−10 indicate successfulpΔMSE fits. For all four models, the sums of all obtained successfulpΔMSE fits out of 19,000 fits are indicated.

We generated one set of stochastically varied data points, as described, and applied the fit routine for the 19 SU vectors à 1,000 fits. We then identified the successfulp fits. Compared with the above approach using the true parameters as start vector, their portion was expectedly very low because the values of the stochastically varied SU start vector must be extremely unfortunate.

Then a second selection algorithm for successful fits out of the successfulp fits was applied.

Using the MSEx values provided by the fit routine, we identified the minimum MSEx value, Min(MSEx) in the 1,000 fits, calculated the difference values ΔMSEx of each MSEx to Min(MSEx) (Eq. 17), and sorted these values starting with the smallest (see Materials and methods). These sorted ΔMSEx values were plotted for x > 0 on a logarithmic scale (Fig. 9 B). The number of ΔMSEx values was very low (<<10−10). At a certain x, ΔMSEx jumped to much higher values >>10−10, indicative of another but much worse fit minimum. These much larger ΔMSEx values were in no case similar to each other as were the ΔMSEx values near ΔMSE1 = 0, suggesting that no other reproducible minimum was present. We then set a threshold at ΔMSEx = 10−10 to identify all fits in close proximity of ΔMSE1 = 0. Furthermore, we specified that for a given SU vector at least five fits with ΔMSEx values below the threshold of 10−10 had to be present among 1,000 fits to accept a true minimum. With these assumptions, we could identify all fits close to the best fit at ΔMSE1 = 0. These fits are denoted successfulpΔMSE fits in the following. In the plots, the fits with ΔMSE1 = 0 were omitted. The diagrams show that out of the 1,000 fits, only a small portion but sufficiently many successfulpΔMSE fits were obtained for all four models. The number of successfulpΔMSE fits was either equal or some smaller than that of successfulp fits.

Plotting histograms for the number of successfulpΔMSE fits as a function of the SU vector shows that it was maximal near the SU vector of 10−1 and drops to both larger and smaller SU start vectors to zero (Fig. 10). As a matter of principle, this means that it is possible to identify a range for the SU vectors that yields the majority of successfulpΔMSE fits. Hence, our chosen SU start vectors cover a reasonable range in which a stochastic variation of the elements of the SU start vector by the factor A = 100 identifies a small but reasonable portion of successfulpΔMSE fits. Moreover, as already indicated in Fig. 9 B, the number of successfulpΔMSE fits for all SU vectors decreases for the more complex models.

Histograms of successful pΔMSE fits with equal SU start vector and stochastically varied elements. For each of the 19 SU vectors (abscissa), at least five successfulpΔMSE fits were required to include them in the histogram. The fits with ΔMSE1 = 0 were omitted. Reasonable numbers of successfulpΔMSE fits were obtained for all CHAx models. The number of successfulpΔMSE fits was maximal near the SU vector of 10−1 and drops to both larger and smaller SU vectors to zero. The number of successfulpΔMSE fits for all SU vectors decreases for the more complex models.

Histograms of successful pΔMSE fits with equal SU start vector and stochastically varied elements. For each of the 19 SU vectors (abscissa), at least five successfulpΔMSE fits were required to include them in the histogram. The fits with ΔMSE1 = 0 were omitted. Reasonable numbers of successfulpΔMSE fits were obtained for all CHAx models. The number of successfulpΔMSE fits was maximal near the SU vector of 10−1 and drops to both larger and smaller SU vectors to zero. The number of successfulpΔMSE fits for all SU vectors decreases for the more complex models.

We next calculated for each model the mean and the standard deviation for all parameters as obtained from the successfulpΔMSE fits with all SU start vectors. These means are again plotted in bar graphs for all parameters together with the true values (Fig. 11). Also the mean relative standard deviations σi,rel for each parameter of 1,000 fits (ipri,1000; Eq. 11) are plotted below each bar graph as in Fig. 7. All parameters could be determined similarly well as with the analysis above although now there was no bias introduced by any specific start vectors. This result is further confirmed by plotting the inaccuracy and the imprecision (Fig. S7), which both closely match the profiles obtained from the successfulp fits using the true parameters as the start vector.

Comparison of fit parameters with equal SU start vector and stochastically varied elements. The same formalism as in Fig. 7. In the bar graphs, the fitted parameters, xi, are compared with the true parameters, xi,tr (gray). For each SU vector, 1,000 fits were performed. The results for the successfulpΔMSE fits are shown. All parameters are determined reasonably though no bias was introduced by specific start vectors. The mean relative standard deviations σi,rel of 1,000 fits, ipri,1000 (Eq. 11), below the bar graph indicates the relative errors of each parameter. The ochre lines and numbers right specify the overall ipri,1000 value for each model and the dashed red line the level of 0.1, i.e., the 10% error.

Comparison of fit parameters with equal SU start vector and stochastically varied elements. The same formalism as in Fig. 7. In the bar graphs, the fitted parameters, xi, are compared with the true parameters, xi,tr (gray). For each SU vector, 1,000 fits were performed. The results for the successfulpΔMSE fits are shown. All parameters are determined reasonably though no bias was introduced by specific start vectors. The mean relative standard deviations σi,rel of 1,000 fits, ipri,1000 (Eq. 11), below the bar graph indicates the relative errors of each parameter. The ochre lines and numbers right specify the overall ipri,1000 value for each model and the dashed red line the level of 0.1, i.e., the 10% error.

Inaccuracy and imprecision with equal SU start vector and stochastically varied elements. The values were obtained from the fits in Fig. 11. (A) Inaccuracy. The mean inaccuracy for each parameter xi, iaci,n, was computed by Eq. 14. The number of included successfulpΔMSE fits, n, is indicated in brackets. (B) Imprecision. The mean imprecision for each parameter xi, ipri,n, was computed by Eq. 11. The gray points indicate the values of Fig. S3 for comparison.

Inaccuracy and imprecision with equal SU start vector and stochastically varied elements. The values were obtained from the fits in Fig. 11. (A) Inaccuracy. The mean inaccuracy for each parameter xi, iaci,n, was computed by Eq. 14. The number of included successfulpΔMSE fits, n, is indicated in brackets. (B) Imprecision. The mean imprecision for each parameter xi, ipri,n, was computed by Eq. 11. The gray points indicate the values of Fig. S3 for comparison.

In summary, our analysis with the stochastically varied SU start vectors used identical data points for the 19,000 fits with all 19 SU vectors, a strategy that could also be run with real experimental data.

As a control, we finally repeated our stochastic approach with different sets of data points for the different SU start vectors, while for the 1,000 fits at each SU start vector, again, identical stochastically varied data points were used. This approach has the advantage that 19 different data point sets were used. If the results are similar to those with identical data points for all SU start vectors, this would confirm that the successful result shown by Figs. 9, 10, and 11; Fig. S7 does not depend on a specific data set. The corresponding Figs. S8, S9, S10, and S11 show a closely similar result to that provided by Figs. 9, 10, 11, and S7, i.e., all parameters are determined, the maximum number of successfulpΔMSE fits was near the SU start vector of 10−1 (Figs. S8 and S9), the parameters match the true parameters (Fig. S10), and the inaccuracy as well as the imprecision (Fig. S11) match those of the corresponding successfulpΔMSE fits shown in Fig. S7 and also those obtained from the successfulp fits shown in Fig. S3. We conclude that our approach is not essentially influenced by a major bias of selecting a specific set of data points.

Successful pΔMSE fits with different stochastically varied SU start vectors. The variation of the scaled SU start vectors followed the algorithm described for Fig. 9 A with the difference that the data points were generated de novo for each SU vector. SuccessfulpΔMSE fits were selected as described in Fig. 9 B by using a threshold (red dashed lines) at 10−10 for the corresponding ΔMSEx values. Again, for all four models, the sums of all obtained successfulpΔMSE fits out of 19,000 fits are indicated.

Successful pΔMSE fits with different stochastically varied SU start vectors. The variation of the scaled SU start vectors followed the algorithm described for Fig. 9 A with the difference that the data points were generated de novo for each SU vector. SuccessfulpΔMSE fits were selected as described in Fig. 9 B by using a threshold (red dashed lines) at 10−10 for the corresponding ΔMSEx values. Again, for all four models, the sums of all obtained successfulpΔMSE fits out of 19,000 fits are indicated.

Histograms of successful pΔMSE fits with different SU vectors and stochastically varied elements. The data correspond to those in Fig. S8. Analogous to Fig. 10, for each of the 19 SU vectors (abscissa), at least five successfulpΔMSE fits were required to include them in the histogram. Reasonable numbers of successfulpΔMSE fits were obtained for all CHAx models. The number of successfulpΔMSE fits was maximal near the SU vector of 10−1.

Histograms of successful pΔMSE fits with different SU vectors and stochastically varied elements. The data correspond to those in Fig. S8. Analogous to Fig. 10, for each of the 19 SU vectors (abscissa), at least five successfulpΔMSE fits were required to include them in the histogram. Reasonable numbers of successfulpΔMSE fits were obtained for all CHAx models. The number of successfulpΔMSE fits was maximal near the SU vector of 10−1.

Comparison of fit parameters with different SU vectors and stochastically varied elements. Same formalism as in Figs. 7 and 11. In the bar graphs, the fitted parameters, xi, are compared with the true parameters, xi,tr (gray). Means and standard deviations of these fits are shown. The mean relative standard deviations σi,rel of 1,000 fits, ipri,1000 (Eq. 11), below the bar graphs indicate the relative errors of each parameter. The ochre lines and numbers right specify the overall ipri,1000 value for each model and the dashed red line the level of 0.1, i.e., the 10% error.

Comparison of fit parameters with different SU vectors and stochastically varied elements. Same formalism as in Figs. 7 and 11. In the bar graphs, the fitted parameters, xi, are compared with the true parameters, xi,tr (gray). Means and standard deviations of these fits are shown. The mean relative standard deviations σi,rel of 1,000 fits, ipri,1000 (Eq. 11), below the bar graphs indicate the relative errors of each parameter. The ochre lines and numbers right specify the overall ipri,1000 value for each model and the dashed red line the level of 0.1, i.e., the 10% error.

Inaccuracy and imprecision of the parameters for successful pΔMSE fits with different SU vectors and stochastically varied elements. Same formalism as in Figs. S3 and S7. (A) Inaccuracy. (B) Imprecision. The gray points indicate the values of Fig. S3 for comparison.

Discussion

Summary

In this study, we investigated the identifiability of 7–41 free parameters determining the CHA2 to CHA5 schemes for LGICs containing two to five binding sites, respectively. These parameters define respective larger numbers of equilibrium association constants as specified in Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4. For our comparison of the performance of the CHA2 to CHA5 models, we included the respective full sets of all possible CARs whose number is given by Eq. 21. The computations showed that the parameters of the most complex CHA5 model with 41 parameters are markedly better determined than those of the much simpler CHA2 model with only 7 parameters. The CHA3 and CHA4 models were in-between. The likely explanation for this apparently counterintuitive result is that the fit constraints rise steeper with the higher complexity than the degrees of freedom introduced by the growing number of parameters.

We like to emphasize again that all computations performed herein were based on the synthetic parameter sets generated by Eq. 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, and 32 in the supplemental text at the end of the PDF. Though the parameter set for LGIC4s was related to some extent to the experimental data in heterotetrameric CNG channels (Schirmeyer et al., 2021), it is synthetic, as are the parameter sets for LGIC2s, LGIC4s, and LGIC5s.

Assumptions for the strategy

Our strategy is based on three assumptions: (1) a known subunit composition of the channel, (2) a marked reduction of the binding affinity at the binding sites by appropriate mutations, and (3) a global fit of CARs obtained from recording macroscopic currents with coupled models.

To apply our strategy to experimental data of concatameric channels, three assumptions have to be fulfilled: (1) the architecture and function of the concatameric channels must be similar to channels built by non-concatenated subunits; (2) the mutations at the binding sites must markedly reduce but not entirely abolish the binding affinity; and (3) the CARs used for the global fits with coupled models must be of high quality.

Assumption 1 requires that the expected architecture and an approximately unchanged function of the concatenated channels can be demonstrated. Possible side effects of linking the subunits can be easily identified by comparing the CAR of the wt concatamer with the CAR of channels built by individual wt subunits. Regarding the architecture, an incorrect assembly of the mutated subunits in the concatamers has to be excluded which might appear if the subunits of two concatamers build only one functional channel while part of the subunits are “looped out” (Steinbach and Akk, 2011). This phenomenon has been originally reported for voltage-gated K+ channels (McCormack et al., 1992) and later also for pentameric ligand-gated nicotinic receptors (Zhou et al., 2003; Groot-Kormelink et al., 2004). A relatively simple functional test would be to take a concatamer containing only wild type subunits and a concatamer containing only mutated subunits, shifting the CAR to much higher concentrations while the slope is unaffected. If coexpressing these concatamers in a 1:1 ratio, channels formed by the two concatamers only would lead to two clearly separated CAR components with unchanged steepness whereas a significant combination of the subunits of the two concatamers within a channel, while looping out others, should lead to a smeared CAR over the whole concentration range. We demonstrated the preservation of the two components for wt and mutated concatamers of homotetrameric CNGA2 channels (Wongsamitkul et al., 2016). Moreover, the consistency of our previous results on concatenated heterotetrameric CNGA4:A2:B1b:A2 channels (Schirmeyer et al., 2021) and homotetrameric HCN2 channels (Sunkara et al., 2018) suggested both a correct architecture and only minor side effects by concatenation. We therefore assume that is generally possible to follow such a strategy. It should also be noted that enforcement of subunits into a desired stoichiometry and position is only one way to define the composition of channels. In case that all subunits differ in their structure and are consistently incorporated in a channel, concatenation is not even required.

Assumption 2 of our strategy includes that the mutations strongly impede the binding sites but preserve functionality, i.e., all mutated binding sites keep their ability to bind a ligand and contribute to activation. We realized this in our simulations by following the previous strategy for tetrameric channels using impeding parameters fdx for each of the subunits, i.e., the fdx values were assumed to be unique for each binding site, independent of the activation of the other subunits. Hence, the fdx factors are helper parameters that are not relevant for interpreting the constants of the wild type channel.

For assumption 3, the global fit with coupled models, we assumed for each binding step individual equilibrium association constants, Kx, but lumped the equilibrium closed–open isomerization constants, Ex, at an equal degree or liganding (Schirmeyer et al., 2021; Benndorf et al., 2022). This significantly reduced the number of parameters. Future simulation studies will show to what extent it is possible to differentiate between the Ex. One possible analysis strategy we already tested is by including data at a second voltage and assuming that each subunit exerts an invariant subunit promotion energy on channel opening (Schirmeyer et al., 2022). Simple additivity of the subunit promotion energies led to individual Ex values for each constellation of liganding. In all fits, we obeyed the principle of microscopic reversibility, which is widely accepted to be physically meaningful though for some ion channels a violation of this principle has been suggested (Schneggenburger and Ascher, 1997; Xu and Meissner, 1998). It should also be noted that we only simulated and analyzed equilibrium constants here which do not tell anything about the dynamic response of the receptors.

Applicability of the approach to LGICs

We demonstrated that our fit approach can be used for LGICs with two to five binding sites (LGIC2 to LGIC5) and that an accurate read-out of channel activation is possible.

Among LGIC3s, possible candidate channels for our approach are trimeric purinergic P2X receptors (Kawate et al., 2009; Hattori and Gouaux, 2012) and related ASICs (Jasti et al., 2007) that form between two adjacent subunits three binding sites. For P2X receptors, there are several reports that concatamers are functional (Nicke et al., 2003; Nagaya et al., 2005; Stelmashenko et al., 2012; Gusic et al., 2021) which would allow us to define the position of the mutated binding sites. For ASICs, we are not aware of respective concatamers.

Typical LGIC4s with four binding sites are AMPA receptors (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). So far there are no reports about functional concatamers in these receptors, possibly because of the problem that the N-terminus is outside. However, for related NMDA receptors, it has been demonstrated that functional concatamers can be constructed (Schorge and Colquhoun, 2003), which might open the door to applying our strategy. In contrast, tetrameric CNG channels (Li et al., 2017) and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (Lee and MacKinnon, 2017) form willingly functional concatamers that can be systematically analyzed (Ulens and Siegelbaum, 2003; Wongsamitkul et al., 2016; Sunkara et al., 2018; Schirmeyer et al., 2021).

Pentameric ionotropic receptors belong mainly to the class of cys-loop receptors. They include the families of nAchRs, GlyRs, and 5HTRs. Many of these receptors are formed by two α-subunits and three other homolog subunits. For example, the classical nAChR of both the electric eel and the electric fish (Changeux et al., 1970; Miledi and Potter, 1971) is composed of two α-subunits, one β-subunit, one γ-subunit, and one δ-subunit (Weill et al., 1974; daCosta and Baenziger, 2013), forming only two bindings sites between the adjacent subunits α and γ as well as α and δ. Therefore, they would be classified herein as LGIC2s. In these channels, the specification of the binding sites need not necessarily be forced by concatenating any subunits because the subunits form on their own channels with defined composition with defined binding sites. Pentameric receptors with five binding sites also exist, e.g., the α7 nAchR (McKay et al., 2007) or the α1 GlyR (Zhu and Gouaux, 2021). In our classification, they would be LGIC5s to be described by the CHA5 model. It seems to be promising to investigate these or other pentameric receptors with the strategy described herein because the subunits can be linked to form functional concatameric channels (Mazzaferro et al., 2017; Prevost et al., 2021). In summary, there are many relevant candidate channels for our strategy to be applied.

Applicability of the approach to other receptors

Our approach should also be applicable to other membrane receptors. This includes voltage-gated ion channels (VGICs), for which functional concatamers have been reported e.g., from Shaker subunits (Tytgat and Hess, 1992; Al-Sabi et al., 2010) and Kv2.1 and Kv6.4 subunits (Möller et al., 2020; Pisupati et al., 2020). Here, a promising idea is to affect the voltage-sensor domain of the subunits by appropriate mutations evoking shifts of steady-state activation to more positive voltages. Though measurement of currents in VGICs is easier than that in LGICs, quantitative analysis as described herein would be more complex because each voltage-dependent equilibrium constant requires two parameters, an equilibrium constant at zero voltage and an apparent gating charge. Moreover, our strategy should be easily usable to analyze natural heterotetramers, such as Nav channels (Jiang et al., 2020) and Cav channels (Wu et al., 2015). Furthermore, our analysis could be applied to oligomeric metabotropic receptors as well if a sufficiently valid read-out of receptor activation is available. Advancements in FRET techniques with dimeric glutamate receptors seem to be a promising strategy (Hlavackova et al., 2005; Grushevskyi et al., 2019; Kukaj et al., 2023).

Another intriguing idea is to analyze double mutations at two relevant positions in a channel or receptor, e.g., one mutation at the ligand binding site and a second in the pore gate. If both mutations exert different single effects, a systematic combination of these mutations should allow us to identify the interaction of the subunit with very high precision. However, the number of required combinations might become immediately very high. For example, introducing in a heteroterameric channel a mutation in the binding site and another mutation in the pore gate would result in maximally 162 = 256 combinations. Nevertheless, it is very likely that such a strategy would allow us to specify very subtle interactions of subunits or binding sites in these oligomeric proteins. Notably, this idea is basically an extension of the idea of the double-mutant cycle analysis (Horovitz, 1996).

The stochastic approach using SU start vectors

A further relevant result is that we successfully used a stochastic approach to identify sufficiently many successfulpΔMSE fits out of a vast number of fits by using SU vectors, scanning a range of nine orders of magnitude, and stochastically varying its elements over additional four orders of magnitude. Though the portion of successfulpΔMSE fits was only small compared with the total number of fits, its results regarding accuracy and precision, quantified by inaccuracy and imprecision, respectively, were entirely reliable. Moreover, the scanning of the SU vector over the useful range of nine orders of magnitude allows an investigator to reliably identify the true parameters without prior knowledge of the parameters. For other applications, the range for the SU vectors could be easily extended. Apparently, there is a maximum incidence of the successfulpΔMSE fits in the range of the true parameters, which was in our case ∼10−1 (c.f., Fig. S2). Our stochastic fit approach seems to be useful for any simple or complex fit problem because the investigator does not have to generate specific starting parameters, in particular if there are no reasonable guesses and the number of parameters is large.

Conclusions

We conclude that for LGICs of known composition with two to five binding sites, our strategy to impede, but not abolish, the affinity of defined binding sites by mutations and to globally fit all respective CAR combinations of wild type and impeded binding sites by systems of respective kinetic schemes is a powerful approach to analyze subunit cooperativity of LGICs in great detail. To exclude any bias in the fit arising from specific start vectors, we show that scaled unitary start vectors stochastically varied over an extremely wide range provide reliable fit results. Remarkably, and to some extent counterintuitively, our results show that the identifiability of the parameters in complex models with more binding sites is superior to that in simple models with less binding sites.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Joseph A. Mindell served as editor.

This work was supported by the Research Unit 2518 DynIon (project P2 to K. Benndorf) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Author contributions: K. Benndorf designed the project, created the simulation and fit software, did the computations, designed the figures, and wrote the manuscript. E. Schulz developed the strategy for using hypercubes in the analysis.

References

Author notes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests exist.