Using optical and electrical methods, we document that diffusion in the cytoplasm of BL6 murine cardiomyocytes becomes restricted >20-fold as molecular weight increases from 30 to 2,000, roughly as expected for pores with porin channel dimensions. Bodipy-FL ATP diffuses >40-fold slower than in free water at 25°C. From several fluorophores analyzed, bound fluorophore fractions range from 0.1 for a 2 kD FITC-labeled polyethylene glycol to 0.93 for sulforhodamine. Unbound fluorophores diffuse at 0.5–8 × 10−7 cm2/s (5–80 μm2/s). Analysis of Na/K pump and veratridine-modified Na channel currents suggests that Na diffusion is nearly unrestricted at 35°C (time constant for equilibration with the pipette tip, ∼20 s). Using multiple strategies, we estimate that at 35°C, ATP diffuses four to eight times slower than in free water. To address whether restrictions are caused more by protein or membrane networks, we verified first that a protein gel, 10 g% gelatin, restricts diffusion with strong dependence on molecular weight. Solute diffusion in membrane-extracted cardiac myofilaments, confined laterally by suction into large-diameter pipette tips, is less restricted than in intact myocytes. Notably, myofilaments extracted similarly from skeletal (diaphragm) myocytes are less restrictive. Solute diffusion in myocytes with sarcolemma permeabilized by β-escin (80 µM) is similar to diffusion in intact myocytes. Restrictions are strain-dependent, being twofold greater in BL6 myocytes than in CD1/J6/129svJ myocytes. Furthermore, longitudinal diffusion is 2.5-fold more restricted in CD1/J6/129svJ myocytes lacking the mitochondrial porin, VDAC1, than in WT CD1/J6/129svJ myocytes. Thus, mitochondria networks restrict long-range diffusion while presumably optimizing nucleotide transfer between myofilaments and mitochondria. We project that diffusion restrictions imposed by both myofilaments and the outer mitochondrial membrane are important determinants of total free cytoplasmic AMP and ADP (∼10 μM). However, the capacity of diffusion to deliver ATP to myofilaments remains ∼100-fold greater than ATP consumption.

Introduction

The evolution of cellular life was shaped profoundly by the physical properties of diffusion in aqueous solutions (Gallet et al., 2017). Diffusion limits the dimensions of cells and determines how cells can be organized into viable three-dimensional tissues. How in detail diffusion becomes modified by protein and membrane networks within cells has been a subject of much research, which extends to the analysis of both natural and unnatural polymer gels (Masaro and Zhu, 1999; Wheatley, 2003; Sanabria et al., 2007; Majer and Southan, 2017; Majer, 2017). Already, in 1930, it was described that organic solutes encounter diffusion barriers in fine-grained gelatin with size exclusion behavior expected for 1–2 nm pores (Friedman and Kraemer, 1930). Only recently it was discovered that the extracellular matrix of cardiac T-tubules entirely excludes molecules with molecular weights (MWs) of 5 kD or greater (Barthé et al., 2022,Preprint). One of the more influential studies of cytoplasmic diffusion appeared in 1969 (Kushmerick and Podolsky, 1969). Analyzing diffusion in intact skeletal muscle, this study laid to rest many speculative hypotheses about diffusion in cells. As expected from the fact that Ca is heavily buffered by Ca-binding proteins, Ca diffusivity is reduced 50-fold in muscle versus free water. In contrast, monovalent ions and ATP diffuse only about twofold less well than in free water. As outlined subsequently, these simple conclusions have been supported for skeletal muscle by experiments employing very different methods. Nevertheless, other studies highlighted subsequently suggest that solute diffusion is more restricted in cardiac myocytes and requires further attention.

Diffusion of sodium ions in cardiac myocytes has generated controversy for decades. Specifically, it was proposed that cytoplasmic Na diffusion is restricted in subsarcolemmal spaces to the extent that large changes in the subsarcolemmal Na concentration occur during Na transport (Carmeliet, 1992; Verdonck et al., 2004). Although this hypothesis is now questioned (Swietach et al., 2015; Garcia et al., 2016; Lu and Hilgemann, 2017), cardiac Na channels (NaVs) and Na/K pumps are still proposed to generate local Na gradients that require many seconds, even minutes, to dissipate (Skogestad et al., 2019). Therefore, we re-examined this issue and again failed to verify that subsarcolemmal Na diffusion is restricted.

The diffusion of ATP has naturally received much attention, given its central roles in energy metabolism (Saks et al., 1994; Jepihhina et al., 2011) and cell signaling (Jones, 1986; Weiss and Lamp, 1987, 1989). Von Wilhelm Hasselbach reported in 1952 that the diffusion coefficient of ATP in skeletal muscle was ∼3 × 10−8 cm2/s (i.e., 3 μm2/s; Hasselbach, 1952), 100 times smaller than when measured later in free water (∼5 × 10−6 cm2/s; Bowen and Martin, 1964). The coefficient given by Hasselbach was later questioned and corrected for glycerol-treated muscle to 2 × 10−6 cm2/s, or about one-half of the free diffusion of ATP in water (Bowen and Martin, 1963). This value was essentially the same as found later for intact skeletal muscle (Kushmerick and Podolsky, 1969). Baylor and Hollingworth used a coefficient of 1.4 × 10−6 cm2/s in their 1998 model describing how Ca buffering by ATP facilitates cytoplasmic Ca diffusion in skeletal muscle (Baylor and Hollingworth, 1998). The diffusion coefficient of a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog in a muscle extract was found to be somewhat smaller, namely 10−6 cm2/s (Sidell and Hazel, 1987). Importantly, 31P NMR studies support a rather free diffusion of ATP in skeletal muscle (Hubley et al., 1995; de Graaf et al., 2000). The latter study (de Graaf et al., 2000) employed fibers with low mitochondrial content and showed that “instantaneous” ATP diffusion occurs with no restriction at all, while diffusion over long distances becomes restricted by ∼60%, with apparent boundaries occurring with 15–22 µm separations. For human calf muscle, a coefficient of 1.5 × 10−6 cm2/s was recently reported using 31P metabolites (Huang et al., 2023). Relevant to these results, a molecular model of diffusion within myofilaments with lattice spacings of 16.5 or 18.3 nm predicted that ATP diffusibility would be decreased by 40% with respect to diffusion in free water (Kekenes-Huskey et al., 2013).

While this consistent body of work supports a nearly free diffusion of ATP in skeletal muscle, the existence of cytoplasmic free ATP gradients is supported by multiple experimental approaches using diverse cell types. Functionally, important cytoplasmic ATP gradients were defined in hepatocytes by analyzing ATP-hydrolyzing enzymes with different cellular locations (Aw and Jones, 1985). ATP gradients were defined in frog oocytes by “cryomicrodissection” studies (Miller and Horowitz, 1986). Relevant to membrane transport, both biochemical and optical studies supported the idea that membrane cytoskeleton can harbor “pools” of ATP that are used preferentially by ion pumps while being “functionally distinct” from bulk cytoplasmic ATP (Chu et al., 2012). In short, protein networks, as well as membrane networks, are proposed to restrict diffusion of nucleotides and other solutes to a physiologically important extent.

Diverse studies suggest that organic solutes may be more restricted in cardiac myocytes than in other cells, including skeletal muscle. Within skeletal muscle fibers, free (unbound) Fura-2 has a diffusion coefficient of 5.2 × 10−7 cm2/s (Pape et al., 1993), 8.6 times smaller than its diffusion in free water (Timmerman and Ashley, 1986). The absorbance dye arsenazo III has a free diffusion coefficient of 8 × 10−7 cm2/s in skeletal muscle with about 90% of the dye being bound (Maylie et al., 1987c). This is only about five times smaller than expected for free arsenazo diffusion in water, and parvalbumin (∼10 kD) is reported to diffuse only about threefold slower in frog skeletal muscle than in free water (Maughan and Godt, 1999).

Turning to cardiac myocytes, the diffusion coefficient of a fluorescent ATP analog in rat cardiac myocytes is approximately eight times less than in free solution (Illaste et al., 2012). This result was interpreted in terms of lattice-like diffusion obstructions with barriers occurring at ∼1 μm distances and barrier pores making up only 0.3% of barrier surfaces. Barriers were suggested to be mostly membranous in nature, with mitochondria, T-tubules, and sarcoplasmic reticulum potentially all taking part. Using sarcolemma-permeabilized cardiac myocytes, this group also showed that cytoplasmic ADP diffusion is restricted 6–10-fold (Simson et al., 2016). To better understand fluorescent Ca dyes in cardiac myocytes, a photobleach method was used to determine the diffusion coefficients for Fura-2 and Indo-1. The coefficients were 1.6 and 3.2 × 10−7 cm2/s, respectively, in guinea pig cardiac myocytes (Blatter and Wier, 1990). The authors concluded that fluorophores diffuse three- to sixfold slower than expected for “free diffusion in myoplasm” (i.e., as described above for skeletal muscle). Impressively, but not stated explicitly, diffusion coefficients of these dyes in cardiac myoplasm are in fact 15–30 times smaller than for their diffusion in water (4.7 × 10−6 cm2/s; Timmerman and Ashley, 1986).

Diffusion of all solutes larger than ions has been suggested to be about 10-fold restricted in cardiac myocytes as a result of “cytoplasmic tortuosity” (Richards et al., 2016). Specifically, diffusion coefficients of multiple fluorophores were found to be about 4 × 10−7 cm2/s, and it was proposed that intracellular membranes, in particular mitochondrial membranes, would account for diffusion restrictions. Notably, this same group found with similar optical methods that Na diffusion was nearly unrestricted (Swietach et al., 2015). Why monovalent ions would experience much less tortuosity than small organic solutes was not explained. Similar to fluorescent ATP analogs, fluorescent cAMP analogs are described to diffuse 50 times more slowly in the cytoplasm of cardiac myocytes than in free water (Sidell and Hazel, 1987). By contrast, cAMP itself has been shown to diffuse in an unrestricted manner in olfactory cilia (Chen et al., 1999), possibly indicting that cAMP diffusion is different in different cell types. Together, these results suggest, as verified by our experimental results, that diffusibility likely falls off steeply with increasing MW in the cardiac cytoplasm.

Regarding cAMP, it has been known for decades that cyclic nucleotide gradients exist in the cytoplasm of many cells (Hayes and Brunton, 1982; Jurevicius and Fischmeister, 1996; Xin et al., 2015; Agarwal et al., 2016; Bock et al., 2020) and their physical basis has been the subject of much debate (Xin et al., 2015; Agarwal et al., 2016). Attention recently has focused on the hydrolysis of cyclic nucleotides by phosphodiesterases (PDEs; Bender and Beavo, 2006). Using a cell-permeable, fluorogenic cAMP analog with a FRET biosensor (Bock et al., 2020), it was recently shown that single PDEs can generate nanoscale cAMP depletion zones, thereby preventing cAMP binding by neighboring cAMP receptors. With progressive activation of adenylate cyclases, PDEs evidently become overwhelmed, resulting in global rises of cAMP. Of course, the ability of PDEs to deplete cAMP would be supported by any cytoplasmic factors that may limit cAMP diffusion in the vicinity of PDEs (Xin et al., 2015).

With this background, we carried out new experiments to characterize diffusion of commonly employed fluorophores in murine cardiac myocytes, we devised protocols to indirectly characterize diffusion of native solutes in myocytes, and we devised experiments to compare diffusion of anions of different MWs in membrane-extracted and sarcolemma-permeabilized cardiac myocytes. We provide evidence that myofilaments themselves can restrict diffusion, but we also show that the outer mitochondrial membrane importantly restricts diffusion in cardiac myocytes. We show that diffusion restrictions depend on the strain of mice from which myocytes are isolated and that knockout of the mitochondrial porin channel, VDAC1, decreases apparent diffusion coefficients of ATP and fluorophores by more than twofold. We suggest that diffusion restrictions imposed by both myofilaments and mitochondria promote long-range solute diffusion to occur through intermembrane mitochondrial spaces. While not limiting ATP supply to myofilaments of cardiac myocytes, both diffusion restrictions and the permeability of porins are likely to be important determinants of cytoplasmic AMP and ADP concentrations, and thereby cardiac nucleotide signaling.

Materials and methods

Murine cardiac myocytes and patch clamp

The UT Southwestern Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal studies.

Cardiac myocytes were isolated from adult (2.5–4 mo old) mice of either sex and patch clamped as described previously (Lu et al., 2016). Diaphragm myocytes were isolated by gently agitating excised pieces of murine diaphragm muscle for 30 min in the same solutions employed for cardiac myocyte isolation. Axopatch 1C patch clamp amplifiers were employed using our own software for capacitance and conductance recording by either sinusoidal or square-wave voltage perturbation (Wang and Hilgemann, 2008). Unless stated otherwise, solutions had the same compositions as employed previously (Lu et al., 2016; Lu and Hilgemann, 2017). As indicated, N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMG) was used as the substitute for extracellular Na. All patch clamp experiments were performed at 0 mV. Experiments related to Na and ATP diffusion (Figs. 8, 9, and 10) were performed at 34°C. Pump currents are activated by exchanging 7 mM extracellular Na for 7 mM extracellular K. The presence of 7 mM Na in the K-free solution is required to suppress pump activation by contaminating K in routinely available chemicals (Lu et al., 2016).

Extracellular solution changes were performed by abruptly moving the microscope stage so as to place the myocyte directly in front of one of four square pipettes (1 mm) with solution steams maintained by gravity-driven flow at velocities of 2–5 cm/s. The rapidity of solution changes was quantified from the deactivation of Na/K pump currents upon removing extracellular K. The moment when myocytes crossed the interface between two solutions was detectable as a small current instability, and the subsequent time required for pump current to decay by >50% amounted to 201 ± 8 ms. Since the half-maximal K concentration is <0.3 mM, this corresponds to approximately four half-times of solution exchange. For optical experiments, we patch-clamped myocytes close to one myocyte end so that the diffusion path constituted most of the length of the myocytes.

In all experiments in which two or more protocols were compared, performing multiple experiments with a single batch of myocytes, the protocols were performed in a randomized fashion. Experiments in which myocytes were compared between two strains were performed, when possible, in a blinded fashion with unblinding only after completion of data analysis.

Materials

Unless stated otherwise, chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich and were the highest grade available. Unbranched FITC-labeled polyethylene glycols (PEGs) were purchased from Creative PEGWorks (27516). Carboxyfluorescein and sulforhodamine were from Sigma-Aldrich. Other fluorophores were from Invitrogen. Luciferase was from Creative Biomart. Purified GFP was a generous gift from Michael Rosen (UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX, USA).

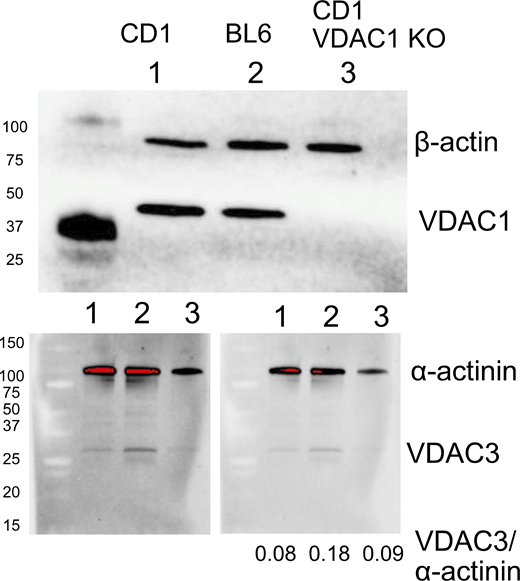

Transgenic mice

Knockout of VDAC1 has partial embryonic lethality in the BL6 mouse strain (Weeber et al., 2002). Therefore, VDAC1 knockout (KO) mice were bred in a CD1/J6/129svJ strain (Anflous et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2019). The wild-type (WT) and KO mice were generated via heterozygote breeding. The resulting WT and KO littermate mice were bred for two generations (WT × WT and KO × KO) to obtain the mice used in the present experiments. All mice were 2.5–3.5 mo old. Equal numbers of male and female mice were employed in experiments with no significant differences in results.

Fluorescence imaging

Imaging at near confocal resolution was carried out with an Aurox Clarity laser-free microscopy system (Fafchamps, 2013), employing a Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-S inverted microscope with an APO LWD 40 × 1.15 NA water immersion lens. The 50% point spread was 0.7 and 1.6 μm in the lateral and vertical directions, respectively, as determined with a TetraSpeck Fluorescent Microspheres Size Kit (Invitrogen). This compares to 0.6 and 2.9 μm for a 40 × 0.95 NA air lens employed on a standard spinning disc microscope (Nikon CSU-W1 spinning disc with Hamamatsu Orca Fusion camera, Nikon CSU-W1 SoRa: Quantitative Light Microscopy Core Facility, UT Southwestern). Equivalent images obtained from the same slide (FluoCells prepared slide #3; Invitrogen) with these two imaging systems are provided in Fig. S1. All solutions were filtered with 0.22 μm syringe filters to remove aggregates. Nevertheless, small condensates sometimes formed in the tip of patch pipettes during long-term (30–60 min) recordings. Their formation had no discernable effects on the experimental results, except to generate an artifactual fluorescence peak in the tip, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The times given in the figures are times after myocyte opening by suction. Most optical experiments were performed at 25°C. To minimize photobleaching, Z-stacks of images were taken at 30–60-s intervals with exposure times as short as possible for accurate analysis, usually 0.2 s.

Two i mages of a membrane-stained nephron (Invitrogen, FluoCells prepared slide #3). (A) Image taken on the microscope employed in all diffusion experiments described in this article: Nikon Eclipse TE2000 microscope equipped with Aurox Clarity and a LWD 40× 1.15 NA water immersion lens. (B) Image taken of the same slide with a Nikon CSU-W1 spinning disc confocal microscope equiped with a 40× 1.3 NA air lens and employing a Hamamatsu Orca Fusion camera. Confocality achieved with the Aurox Clarity system is at minimum comparable to the Nikon spinning disc system.

Two i mages of a membrane-stained nephron (Invitrogen, FluoCells prepared slide #3). (A) Image taken on the microscope employed in all diffusion experiments described in this article: Nikon Eclipse TE2000 microscope equipped with Aurox Clarity and a LWD 40× 1.15 NA water immersion lens. (B) Image taken of the same slide with a Nikon CSU-W1 spinning disc confocal microscope equiped with a 40× 1.3 NA air lens and employing a Hamamatsu Orca Fusion camera. Confocality achieved with the Aurox Clarity system is at minimum comparable to the Nikon spinning disc system.

Experimental models employed

Fig. 1 illustrates the different models employed to characterize diffusion. Standard myocyte patch clamp was employed as shown in Fig. 1 A. Murine cardiac myocytes were patch-clamped close to one end so as to force diffusion to occur through the entire length of the myocyte (∼120 µm). Diffusion in sarcolemma-permeabilized myocytes was evaluated by aspirating myocytes into highly polished, large-diameter patch pipette tips, as shown in Fig. 1 B. To do so, pipette tips were cut and melted to generate bullet-shaped tips with thick (>5 μm) terminal walls and openings of 6–12 μm (Hilgemann and Lu, 1998). Myocytes with a receding appendage were selected so that upon rapid aspiration myocytes briskly entered the tip with formation of a mechanically stable whole-cell seal of minimally 20 MΩ. Thereafter, the sarcolemma was permeabilized with the saponin, β-escin (80 μM; Konishi and Watanabe, 1995). As illustrated Fig. 1 B, we estimate that the restricted diffusion path amounts to about 20 μm. Further details are provided in Results. Diffusion restrictions conferred by myofilaments themselves were evaluated in similar experiments using myocytes that were extracted for 2–10 d in solutions consisting of 50% glycerol with 1 mM Triton X-100, 1 mM EGTA, and 2 mM MgATP at 4°C. Diffusion through gels and viscous solutions of macromolecules (Figs. S6 and S10) was monitored electrophysiologically as illustrated in Fig. 1, C and D. Gelatins or polymer mixtures were aspirated into the tips of pipettes, and gelatins were allowed to set until firm without changing solutions. Fig. 1 D illustrates the large pipette tips usually employed with gelatins. Briefly, 1 mm diameter borosilicate pipettes were melted on a glass flame to generate nearly linear vestibules over lengths of 0.25–0.5 mm with diameters of 30–60 μm (see Fig. S6). Diffusion of fluorophores over multiple hours and days was monitored in borosilicate glass capillaries with inner diameters of 1 mm and lengths of 8 cm, as illustrated in Fig. 1 E. To do so, the pipettes were filled by negative pressure to a height of 4 cm with one solution of interest. Next, that end was dipped into molten dental wax and the wax was allowed to harden. The remaining half of the pipette was then filled via a fine polyethylene tube (0.1 mm diameter), taking care to avoid any mixing. Finally, the second end of the tube was sealed with wax and the pipette was stored in the dark at 25°C unless indicated otherwise. After selected periods of time, from 1 h to 1 wk, fluorescence of the pipettes was imaged at the most appropriate wavelengths available for each fluorophore with a Biorad Chemi Doc MP Imaging System. To determine specific conductances of electrolyte solutions (not illustrated), we employed 15-cm-long lengths of Tygon tubing with an inner diameter of 0.5 mm. Solutions were aspirated into the tubes by negative pressure. Taking care to avoid formation of bubbles, the ends of the tubes were placed into physically separated chambers containing 30 mM KCl. Silver/silver chloride electrodes were then connected to each chamber, and conductance was monitored via sinusoidal voltage perturbation at 0.2 kHz using our own software. Results were then quantified as mS/cm. To determine osmolarities of electrolyte solutions (not illustrated), we employed a Precision Systems Micro-Osmette micro-osmometer.

Experimental diffusion models employed in this study. (A) Myocytes were patch-clamped close to one end, selecting myocytes 110–130 µm in length. In simulations, the concentrations of solutes within the pipette tip were constant. (B) Permeabilized or detergent/glycerol-extracted myocytes were aspirated rapidly into highly polished pipette tips with inner diameters of ∼12 µm. The restricted region, limiting conductance of the patch pipette, was estimated to be 10–25 µm long. (C and D) Gelatins and/or viscous polymer solutions were aspirated into pipette tips, and the limiting conductance was monitored during and after rapidly switching the pipette tip between solution streams of different compositions. Pipettes were employed with restrictions occurring over 20 μm (C) up to 300 μm (D). (E) 8-cm-long glass pipettes with a 1-mm inner diameter were carefully filled over 4 cm with one chosen solution, and the corresponding end was sealed with dental wax. Then, the second half of the pipette was filled with a second chosen solution, the corresponding end was also sealed with wax, and fluorescence profiles were acquired at chosen times as described in Materials and methods.

Experimental diffusion models employed in this study. (A) Myocytes were patch-clamped close to one end, selecting myocytes 110–130 µm in length. In simulations, the concentrations of solutes within the pipette tip were constant. (B) Permeabilized or detergent/glycerol-extracted myocytes were aspirated rapidly into highly polished pipette tips with inner diameters of ∼12 µm. The restricted region, limiting conductance of the patch pipette, was estimated to be 10–25 µm long. (C and D) Gelatins and/or viscous polymer solutions were aspirated into pipette tips, and the limiting conductance was monitored during and after rapidly switching the pipette tip between solution streams of different compositions. Pipettes were employed with restrictions occurring over 20 μm (C) up to 300 μm (D). (E) 8-cm-long glass pipettes with a 1-mm inner diameter were carefully filled over 4 cm with one chosen solution, and the corresponding end was sealed with dental wax. Then, the second half of the pipette was filled with a second chosen solution, the corresponding end was also sealed with wax, and fluorescence profiles were acquired at chosen times as described in Materials and methods.

Preparation of gelatins

Gelatins employed in diffusion experiments were prepared as an equal mix of Type A and Type B gelatins (Sigma-Aldrich). The gelatins were cleaned by allowing them to set first in a 10-cm-diameter beaker at a thickness of ∼0.5 cm. After setting, gelatins were soaked with a chosen solution and tilt-rocked for 2–3 d with multiple solution changes. The gelatins were then re-liquified by warming and allowed to set for 10–30 min in pipettes before completing subsequent preparations for experiments.

Western blotting

Western blots presented in Fig. S5 were performed by SDS-PAGE using extracts of isolated murine myocytes prepared with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, as described previously (Deisl et al., 2019). Complete details are provided in the legend of Fig. S5.

Statistics

Statistical significance was assessed via Student’s T test after determining that results were distributed normally. Error bars in figures represent standard errors. Significant differences are indicated with one, two, or three asterisks in figures, corresponding to P < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively.

Simulations and theoretical principles

All simulations were carried out with Matlab software, employing error checking and step-size adjustment to ensure accuracy within the line-width of plotted results.

To simulate diffusion of monovalent ions and MgATP in Fig. 10 G, the exchange of ATP across the pipette tip was simulated to occur, similar to fluorophores, fourfold faster than its subsequent diffusion through the entire cytoplasm. The diffusion of solutes through the first compartment (i.e., the narrowest zone of the tip) was constructed to duplicate results just outlined. MgATP exchanged four times slower across the tip than Na, Cl, and K, as expected for free water. Within the cytoplasm, this relationship was reversed such that MgATP diffused 20 times slower than K and Cl (0.06 versus 1 × 10−5 cm2/s).

For simulation of open pipette tips employed in other types of experiments (Figs. 10, 11, S6, and S10), the nth compartment was fixed at the initial solute concentration employed in the pipette. For simulations of diffusion in long (8 cm) pipettes (Figs. S7, S8, S9, and S11), the pipette contents were assumed to be divided into two phases with a sharp interface, and simulation was initiated with two different homogenous solute concentrations in the two halves.

Simulated average ion concentrations and conductance generated in a restricted column, 12 µm long. The column is open at both ends. Diffusion occurs similarly within the column and within 5-µm extensions of the column that extend from the column end, but do not contribute to the monitored conductance. (A) Left: Results for an ion pair with equal anion and cation diffusion coefficients. Initially, the concentration is 2 mM everywhere. As indicated, the concentration was increased to 40 mM at the front of the column for 3 s and then decreased again to 2 mM. Right: Equivalent results for the case that the anion diffusion coefficient was 10-fold less than the cation diffusion coefficient. Results in red are a model in which diffusion of the anion and cation were simulated separately, and results in blue are for a model assuming a diffusion coefficient for the ion pair as given in B. (B) Plot of the rate constants (x axis), determined from single exponential fits of the decaying conductance, against the relative anion diffusion coefficient (y axis), which was varied over 1,000-fold. The predicted coupled diffusion coefficient accurately describes the relationship over the entire three-log unit range.

Simulated average ion concentrations and conductance generated in a restricted column, 12 µm long. The column is open at both ends. Diffusion occurs similarly within the column and within 5-µm extensions of the column that extend from the column end, but do not contribute to the monitored conductance. (A) Left: Results for an ion pair with equal anion and cation diffusion coefficients. Initially, the concentration is 2 mM everywhere. As indicated, the concentration was increased to 40 mM at the front of the column for 3 s and then decreased again to 2 mM. Right: Equivalent results for the case that the anion diffusion coefficient was 10-fold less than the cation diffusion coefficient. Results in red are a model in which diffusion of the anion and cation were simulated separately, and results in blue are for a model assuming a diffusion coefficient for the ion pair as given in B. (B) Plot of the rate constants (x axis), determined from single exponential fits of the decaying conductance, against the relative anion diffusion coefficient (y axis), which was varied over 1,000-fold. The predicted coupled diffusion coefficient accurately describes the relationship over the entire three-log unit range.

As the anion diffusion coefficient is decreased, the decay rate decreases as indicated in Fig. 2 B. The coupled coefficient decreases with the square root of the diffusion coefficient, at first. Then, as the anion diffusion coefficient decreases by more than a factor of 10, the decay constant decreases linearly with the diffusion coefficient. Importantly, the solution conductance can decrease by only a factor of two as the anion diffusion coefficient decreases from that of the cation employed to negligible values.

Since free ATP carries about four negative charges at neutral pH, MgATP complexes are often assumed to carry about two negative charges at pH 7 (Stockbridge and Wolfenden, 2009). We observe, however, that titration of high-grade MgATP (Sigma-Aldrich) yields pH values higher than 7.0 with the addition of 1.2 mol of alkali per mole of MgATP, suggesting that one of the two remaining negative charges remains largely proton-bound at pH 7. This impression is supported by 31P NMR analysis of MgATP solutions with pH titration, also indicating that the valence of MgATP at pH 7.0 is about −1.2 (Song et al., 2008). 31P NMR studies indicate that ATP dimers and complexes of ATP with monovalent cations occur physiologically in cells (Glonek, 1992). All results presented in this article simulate MgATP as a monovalent anion, but results were not significantly different when routines were developed to simulate ATP valences over the range of −1.2 to −2.0.

For simulation of pipette tips with long diffusion paths, tip dimensions were reconstructed digitally as described in Fig. S6 and used to simulate diffusion through the tip in compartments constructed perpendicular to the tip axis. As already sketched, for simulations of diffusion through aspirated myocytes, we assumed that the limiting pipette tip conductance arose from a restriction 10–20 μm long. Diffusion was simulated to continue similarly through 5–10 μm myofilament zones that were not restricted and therefore did not contribute to the measured conductance.

Fig. 3 documents the feasibility of resolving multiple kinetic components when three ions are present in experiments. In this example, a 20-µm diffusion path is assumed to be open at both ends (approximating Fig. 1 D) with 100 mM KCl being present initially on both sides of the confined path. In the hypothetical experiment, 50 mM K(Mg)ATP is applied to one side in addition to 100 mM KCl for 3 s. The diffusion coefficient of the “monovalent” (Mg)ATP anion is varied by 16-fold. For results in Fig. 3 A, the diffusion coefficient of ATP is 0.8 × 10−5 cm2/s while that of both K and Cl is 2 × 10−5 cm2/s. The rising and falling conductance curves have fast and slow components, the fast component corresponding to the coupled diffusion constant of KCl and the slow component corresponding to the coupled diffusion coefficient of K(Mg)ATP. In brief, the fast component corresponds to an initial diffusion of KCl into the confined space, as K diffuses ahead of K(Mg)ATP into and out of the confined space. The slow component corresponds to exchange of excess Cl in the confined space for (Mg)ATP, followed by coupled diffusion of K(Mg)ATP. The red curves in Fig. 3 A are the best fits of double exponential functions to the simulated conductance curve. The recovered time constants are in good agreement for the rising and falling phases. Fig. 3 B plots results of simulations in which the anion (MgATP) diffusion coefficient was decreased by 12-fold from that of Cl. The slow exponential time constant, relative to the time constant with all diffusion coefficients being equal, is plotted on the y axis against the assumed diffusion coefficient of MgATP on the x axis, relative to that of Cl. The slow exponential phase of both the rising and falling conductance curves represent accurately the ratio of the diffusion coefficient of the second anion (i.e., MgATP) to that of KCl (i.e., the time constant of the fast exponential in the two-exponential fit). In Fig. 10, these same principles are exploited to analyze coupled diffusion of Na with Cl, aspartate, MgATP, and an anionic polyethylene glycol. In Fig. S4, implications are outlined for current transients induced by voltage perturbation.

Determination of relative diffusion coefficients when three ions are present in simulations, equivalent to those of Fig. 2 . (A) Initially, 100 mM KCl is assumed to be present everywhere with K and Cl having identical diffusion coefficients. As indicated, 50 mM K(Mg)ATP is assumed to be added to the solution in front of the column, whereby the diffusion coefficient of (Mg)ATP is 2.5-fold less than that of K and Cl. The results give rise to double exponential rising and falling conductances, whereby the fitted time constants occur in ratios of 2.47 and 2.32, respectively. (B) The ratios of time constants fitted to simulations in which the diffusion coefficient of ATP was varied over a 10-fold range with respect to those of K and Cl. The fitted exponentials accurately recover the relative diffusion constants of (Mg)ATP and KCl over the entire concentration range.

Determination of relative diffusion coefficients when three ions are present in simulations, equivalent to those of Fig. 2 . (A) Initially, 100 mM KCl is assumed to be present everywhere with K and Cl having identical diffusion coefficients. As indicated, 50 mM K(Mg)ATP is assumed to be added to the solution in front of the column, whereby the diffusion coefficient of (Mg)ATP is 2.5-fold less than that of K and Cl. The results give rise to double exponential rising and falling conductances, whereby the fitted time constants occur in ratios of 2.47 and 2.32, respectively. (B) The ratios of time constants fitted to simulations in which the diffusion coefficient of ATP was varied over a 10-fold range with respect to those of K and Cl. The fitted exponentials accurately recover the relative diffusion constants of (Mg)ATP and KCl over the entire concentration range.

Online supplemental material

We provide the following materials as supplementary data: (1) images of the same slide taken with the Aurox Clarity-equipped Nikon Eclipse microscope used in this study and with a conventional spinning disc confocal microscope (Fig. S1). (2) Supplementary data concerning cardiac myocytes employed in this study. This includes additional examples of fluorophore diffusion in myocytes, a description of experiments with Na dyes to attempt to monitor Na concentration changes and gradients in myocytes, and Western blots to document VDAC1 knockout and lack of compensation of VDAC1 by other VDAC isoforms (Figs. S2, S3, S4, and S5). (3) An analysis of diffusion in gelatins. Specifically, we demonstrate with both optical and electrical methods that diffusion in gelatins is restricted with strong dependence on MW, that ATP diffusion is restricted by nearly 10-fold in 10 g% gelatin, and that restrictions are effectively lost when the gel state is disrupted by warming to 36°C (Figs. S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, and S12). Table S1 tabulates the ratios of solute concentration gradients in water (140 mM KCl) versus 10 g% gelatin on opposing sides of the interface between phases. Additional text can be found at the end of the PDF.

Results

Concentration–conductance relations relevant to this study

Concentration–conductance relations of ionic solutes employed in this study. Conductivity of solutions aspirated into 15-cm-long Tygon tubes with an inner diameter of 0.5 mm. (A) Linear plot of the KCl concentration–conductance relation over three log units. The relation is fit to a modified Kohlrausch equation that includes a constant giving the concentration at which the molar conductivity is reduced by one-half (K50). The measurements give a K50 of 760 mM for KCl. (B) NaCl concentration–conductance relation determined using a patch pipette as in supplemental data. The K50 is 312 mM. (C) Concentration–conductance relation and concentration–osmolarity relation for Na(Mg)ATP solutions, prepared by dilution of a 120 mM MgATP solution, titrated to pH 7.0 with NaOH. While osmolarity is directly proportional to concentration, the concentration–conductance relation is distinctly non-linear and has a K50 of 129 mM. Presumably, therefore, this non-linearity reflects electrostatic interactions that reduce conductivity with increasing concentration, as described by Kohlrausch (Walter and DeWane, 1970). (D) Concentration-conductance relation of K(Mg)ATP solutions, prepared similarly to Na(Mg)ATP solutions. The K50 is 135 mM.

Concentration–conductance relations of ionic solutes employed in this study. Conductivity of solutions aspirated into 15-cm-long Tygon tubes with an inner diameter of 0.5 mm. (A) Linear plot of the KCl concentration–conductance relation over three log units. The relation is fit to a modified Kohlrausch equation that includes a constant giving the concentration at which the molar conductivity is reduced by one-half (K50). The measurements give a K50 of 760 mM for KCl. (B) NaCl concentration–conductance relation determined using a patch pipette as in supplemental data. The K50 is 312 mM. (C) Concentration–conductance relation and concentration–osmolarity relation for Na(Mg)ATP solutions, prepared by dilution of a 120 mM MgATP solution, titrated to pH 7.0 with NaOH. While osmolarity is directly proportional to concentration, the concentration–conductance relation is distinctly non-linear and has a K50 of 129 mM. Presumably, therefore, this non-linearity reflects electrostatic interactions that reduce conductivity with increasing concentration, as described by Kohlrausch (Walter and DeWane, 1970). (D) Concentration-conductance relation of K(Mg)ATP solutions, prepared similarly to Na(Mg)ATP solutions. The K50 is 135 mM.

As indicated in Fig. 4 A, the K50 determined for KCl solutions was 760 mM, indicating that the concentration–conductance relation deviates about 10% from linearity at 100 mM. Conductance results for NaCl solutions, shown in Fig. 4 B, were obtained using a borosilicate patch pipette as employed in Figs. 11 and 12. While the K50 for NaCl, 312 mM, is lower than for KCl, the deviation from linearity up to 50 mM is insignificant for the purposes of the present study. These results are closely consistent with historical data, as well as recent studies (Artemov et al., 2015; Kamceva, 2018; Widodo, 2018; Lee, 2020). As needed to characterize coupled Na and MgATP diffusion, described subsequently, Fig. 4 C shows the concentration–conductance relationship of Na(Mg)ATP together with the corresponding concentration–osmolarity relationship. Samples employed were prepared by serial dilution of a 120 mM MgATP solution titrated to pH 7.0 with NaOH. The concentration–conductance relation clearly tends to saturate, possibly indicative of Na(Mg)ATP complexes at higher concentrations. This is likely not the case, however, since the corresponding concentration–osmolarity relation is accurately described by a straight line. Rather, Na and MgATP must interact electrostatically more than Na and Cl without forming complexes. The K50 of the Kolhrausch equation is 129 mM, less than half the value for NaCl, and Fig. 4 D presents a very similar concentration–conductance relation obtained for K(Mg)ATP (K50, 135 mM).

Diffusion of fluorescent dyes in free water revisited

For the purposes of this study, we determined the diffusion coefficients of several fluorophores in water using 8-cm-long, 1-mm-diameter pipettes. The solution contained 140 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 5 mM HEPES, set to pH 7.4 with KOH. As described in Materials and methods, pipettes were filled to 4 cm via negative pressure with either dye-containing solution or dye-free solution. To avoid any smearing of dye along the inner pipette wall, the exact position of the interface could not be controlled with precision. The remaining 4 cm of the pipette was filled with the complementary dye-free or dye-containing solution, pipettes were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1–72 h and were imaged as described in Materials and methods. Fig. 5 A shows the 1- and 48-h profiles for Bodipy-ATP in gray and black, respectively. The fluorescence image of the pipette at 48 h is shown above the fluorescence profiles. Figs. 5, B–D, show the 48 h profiles in black for Fluo3, Mg-Green, and Fluo-5N, employed at concentrations of 1–10 μM. The position of the solution interface in the pipettes is denoted by a gray vertical line. In addition, each panel shows the relevant simulations for diffusion coefficients of 10−6 cm2/s and 4.5 × 10−6 cm2/s. In all four cases, including 20 similar experiments, the 48-h diffusion profile is described well by a diffusion coefficient of ∼4.5 × 10−6 cm2/s, and the profile for 10−6 cm2/s is approximately fourfold too steep, indicating that it underestimates diffusion of fluorophores in water by about fourfold.

Fluorescence profiles of four fluorophores after initiating diffusion from one-half of 8-cm-long glass pipettes ( inner diameter, 1 mm, 24°C). (A–D) The solution contained 140 mM KCl, 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM EGTA, and 0.5 mM Mg. For Bodipy-FL-ATP (A), the Biorad Chemi Doc fluorescence image for the 48 h tube is given above the profiles, and the fluorescence profile is given at 1 h (gray) and 48 h (black). To avoid bubbles and smearing of solutions along the pipette wall, the solution was loaded without attempting to force an exact interface position at 4 cm. The interface positions for each result are indicated by a gray vertical line, and each result was simulated separately using the appropriate interface position. For Fluo3 (B), Mg-green (C), and Fluo-5N (D), the profiles are given only for 48 h (black). Simulated diffusion profiles for 48 h are given in each panel for a 10−6 cm2/s diffusion coefficient and for a 4.5 × 10−5 cm2/s diffusion coefficient. In all cases, the larger diffusion coefficient accurately describes the profiles, while the smaller coefficient does not.

Fluorescence profiles of four fluorophores after initiating diffusion from one-half of 8-cm-long glass pipettes ( inner diameter, 1 mm, 24°C). (A–D) The solution contained 140 mM KCl, 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM EGTA, and 0.5 mM Mg. For Bodipy-FL-ATP (A), the Biorad Chemi Doc fluorescence image for the 48 h tube is given above the profiles, and the fluorescence profile is given at 1 h (gray) and 48 h (black). To avoid bubbles and smearing of solutions along the pipette wall, the solution was loaded without attempting to force an exact interface position at 4 cm. The interface positions for each result are indicated by a gray vertical line, and each result was simulated separately using the appropriate interface position. For Fluo3 (B), Mg-green (C), and Fluo-5N (D), the profiles are given only for 48 h (black). Simulated diffusion profiles for 48 h are given in each panel for a 10−6 cm2/s diffusion coefficient and for a 4.5 × 10−5 cm2/s diffusion coefficient. In all cases, the larger diffusion coefficient accurately describes the profiles, while the smaller coefficient does not.

Diffusion of Bodipy-FL-ATP in myocytes

Fig. 6 describes the time course with which the fluorescent ATP analog, Bodipy-FL-ATP, enters a mouse myocyte from a patch pipette and diffuses to equilibrium within the myocyte. Micrographs of the patch pipette tip with attached myocyte are shown just after opening the myocyte, as well as at 3- and 40-min time points (Fig. 6, A–C). Total fluorescence of the myocyte increases to a plateau with a time constant of 17 min (Fig. 6 D), while fluorescence just next to the pipette tip increases to a plateau with a time constant of 7.4 min (F0 in panel D). Even after 40 min, line scans reveal longitudinal Bodipy-FL-ATP gradients in the cytoplasm, decreasing from the pipette tip to the opposite myocyte end (Fig. 6 E). We note that the fluorescence of the myocyte cytoplasm protrudes clearly into the pipette tip (see micrograph B). Thus, the time course of fluorophore exchange through the pipette tip might be influenced by cytoplasmic constituents. Line scans across the pipette and the width of the myocyte (Fig. 6 F) reveal the development of a condensate in the tip, in spite of the pipette solution being carefully filtered. Importantly, our experience with many fluorophores was that formation of small condensates in the tip did not affect time courses of fluorophore exchange. Fluorophore accumulation in cytoplasm next to the tip (F0) remained slightly less than one-half of the bulk pipette fluorescence, even after 1 h. Accordingly, dye binding to cytoplasmic constituents cannot explain the slow time course with which dye equilibrates with the cytoplasm. To simulate qualitatively the time course of total fluorophore accumulation (Fig. 6 G) and the longitudinal gradients of fluorophore after 3, 15, and 40 min (Fig. 6 H), we found a diffusion coefficient of 6 × 10−8 cm2/s to be optimal. To simulate the time course of dye accumulation next to the pipette tip (F0), dye exchange across the pipette tip must take place 2.8-fold faster than mean dye accumulation within the myocyte. In other words, resistivity of cytoplasm drawn into the tip is approximately threefold less than the resistivity of the entire myocyte for the diffusion of this fluorophore. This contrasts with equivalent experiments for Na, Cl, and K diffusion in patch-clamped myocytes in which pipette resistance must be assumed to be threefold greater than longitudinal myocyte resistance (Lu and Hilgemann, 2017).

Bodipy-FL-ATP (10 μM) diffusion into a cardiac myocyte from a patch pipette (on-cell pipette resistance, 3 MΩ 24°C). (A–C) Fluorescence micrographs of the myocyte and patch pipette tip just before opening the myocyte (A), after 3 min (B), and after 40 min (C). Dashed lines indicate the positions of the fluorescence intensity profiles displayed in E and F. Intensities were normalized to a maximal cytoplasmic value in each experiment as arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU). (D) The time course of total cytoplasmic fluorescence (red), fitted to an exponential function (gray; time constant, 17 min), and the time course of cytoplasmic fluorescence immediately in front of the pipette tip (blue, F0). The average time constant for four experiments was 42 min. (E) Longitudinal fluorescence line scans along the myocyte at 0, 3, 15, and 40 min. Note that a longitudinal gradient is still evident after 40 min. F0 indicates the position of data points in D. (F) Line scan through the pipette tip and across the width of the myocyte, as indicated in A and C, at 0 and 40 min. As described in Materials and methods, a fluorescence peak (gray) often formed in the pipette tip over 40 min. This corresponds to a fluorophore condensate, which had in our experience no evident effect on experimental results. Fluorescence of the myocyte cytoplasm remained <50% of the pipette tip fluorescence, similar to three equivalent experiments. (G and H) Simulation of Bodipy-FL-ATP diffusion into a myocyte assumed to be 120 μm long. From the four myocytes studied, equilibration was the fastest in this myocyte. Therefore, the simulated diffusion coefficient obtained, 6 × 10−8 cm2/s, is the maximal coefficient justified by experimental results. (G) Simulated mean cytoplasmic fluorophore concentration (red) and fluorophore concentration in the first compartment at the pipette tip ([X]0). Accurate simulation was obtained with the time constant of dye diffusion through the entire cytoplasm, approximated as , being approximately threefold greater than the time constant of dye exchange between the pipette tip and the cytoplasm, 1/Kpip (Eq. 3). This reflects reasonably the ratio of time constants for F0 and the mean myocyte fluorescence in D. (H) Simulated cytoplasmic concentration profiles at the given time points after initiating diffusion from the pipette tip.

Bodipy-FL-ATP (10 μM) diffusion into a cardiac myocyte from a patch pipette (on-cell pipette resistance, 3 MΩ 24°C). (A–C) Fluorescence micrographs of the myocyte and patch pipette tip just before opening the myocyte (A), after 3 min (B), and after 40 min (C). Dashed lines indicate the positions of the fluorescence intensity profiles displayed in E and F. Intensities were normalized to a maximal cytoplasmic value in each experiment as arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU). (D) The time course of total cytoplasmic fluorescence (red), fitted to an exponential function (gray; time constant, 17 min), and the time course of cytoplasmic fluorescence immediately in front of the pipette tip (blue, F0). The average time constant for four experiments was 42 min. (E) Longitudinal fluorescence line scans along the myocyte at 0, 3, 15, and 40 min. Note that a longitudinal gradient is still evident after 40 min. F0 indicates the position of data points in D. (F) Line scan through the pipette tip and across the width of the myocyte, as indicated in A and C, at 0 and 40 min. As described in Materials and methods, a fluorescence peak (gray) often formed in the pipette tip over 40 min. This corresponds to a fluorophore condensate, which had in our experience no evident effect on experimental results. Fluorescence of the myocyte cytoplasm remained <50% of the pipette tip fluorescence, similar to three equivalent experiments. (G and H) Simulation of Bodipy-FL-ATP diffusion into a myocyte assumed to be 120 μm long. From the four myocytes studied, equilibration was the fastest in this myocyte. Therefore, the simulated diffusion coefficient obtained, 6 × 10−8 cm2/s, is the maximal coefficient justified by experimental results. (G) Simulated mean cytoplasmic fluorophore concentration (red) and fluorophore concentration in the first compartment at the pipette tip ([X]0). Accurate simulation was obtained with the time constant of dye diffusion through the entire cytoplasm, approximated as , being approximately threefold greater than the time constant of dye exchange between the pipette tip and the cytoplasm, 1/Kpip (Eq. 3). This reflects reasonably the ratio of time constants for F0 and the mean myocyte fluorescence in D. (H) Simulated cytoplasmic concentration profiles at the given time points after initiating diffusion from the pipette tip.

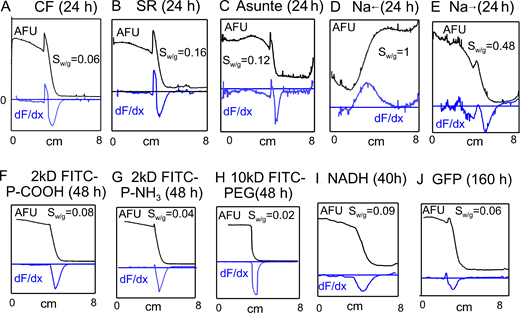

Diffusion of all fluorophores is restricted in myocytes

Fig. 7 presents equivalent diffusion experiments for seven fluorophores at 24°C. Panels A and B present results for sulforhodamine (MW, 559) and carboxyfluorescein (MW, 376). From all fluorophores examined in myocytes, sulforhodomine showed the highest degree of accumulation in cytoplasm with respect to the pipette. This is apparent in the micrograph from the fact that the pipette tip (marked with a diamond) is hardly visible, whereas cytoplasm that is drawn into the pipette tip in line scan #2 is bright. Sulforhodamine equilibrated with the cytoplasm with a very long time constant, on average 28 min (n = 5). As evident in line scan #1 in the right panel, the longitudinal gradient was very strong even after 50 min. As apparent in line scan #2, the dye accumulated in the cytoplasm by at least eightfold with respect to the pipette tip. Thus, dye binding to cytoplasmic constituents is clearly a strong determinant of sulforhodamine diffusion.

Diffusion of fluorophores into cardiac myocytes during patch clamp with ∼3 MΩ access resistance (24°C). Each panel shows the micrograph of a myocyte after ∼1 h of diffusion (left), the time course of total fluorescence changes during the experiment (middle), and line scans as indicated in the micrograph, using yellow dots to indicate the starting position of the line scan (right). (A) Sulforhodamine (100 μM) equilibrates with an average time constant of 29 min (middle panel, n = 5). It accumulates eightfold in the cytoplasm (see line scan 2 across the myocyte and into the pipette tip), and it shows a strong longitudinal gradient even after 1 h. Diamonds indicate the starting position of the line scan 2. (B) Carboxyfluorescein (100 μM) equilibrates with an average time constant of 10 min (middle panel, n = 6) and shows longitudinal gradients even after 1 h. Dye accumulation in cytoplasm versus pipette tip remains very small. (C) Asante Na-green (ASG2, 10 μM) also equilibrates with a very long time constant (40 min, middle panel) and shows a longitudinal gradient even after 1 h. Strong fluorescence occurs in myocytes in the absence of Na. (D–F) A 0.5-kD, a 2-kD, and a 10-kD FITC-PEG (100 μM) equilibrate over 1 h with average time constants of 11, 23, and 15 min (n = 6, 5, and 6, respectively), show no evidence of significant binding, and show clear longitudinal gradients even after 1 h. (G) Purified GFP (12 μM) accumulates weakly in the cytoplasm with respect to the pipette tip with an average time constant of 14 min (n = 6). Fluorescence does not show clear longitudinal gradients. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

Diffusion of fluorophores into cardiac myocytes during patch clamp with ∼3 MΩ access resistance (24°C). Each panel shows the micrograph of a myocyte after ∼1 h of diffusion (left), the time course of total fluorescence changes during the experiment (middle), and line scans as indicated in the micrograph, using yellow dots to indicate the starting position of the line scan (right). (A) Sulforhodamine (100 μM) equilibrates with an average time constant of 29 min (middle panel, n = 5). It accumulates eightfold in the cytoplasm (see line scan 2 across the myocyte and into the pipette tip), and it shows a strong longitudinal gradient even after 1 h. Diamonds indicate the starting position of the line scan 2. (B) Carboxyfluorescein (100 μM) equilibrates with an average time constant of 10 min (middle panel, n = 6) and shows longitudinal gradients even after 1 h. Dye accumulation in cytoplasm versus pipette tip remains very small. (C) Asante Na-green (ASG2, 10 μM) also equilibrates with a very long time constant (40 min, middle panel) and shows a longitudinal gradient even after 1 h. Strong fluorescence occurs in myocytes in the absence of Na. (D–F) A 0.5-kD, a 2-kD, and a 10-kD FITC-PEG (100 μM) equilibrate over 1 h with average time constants of 11, 23, and 15 min (n = 6, 5, and 6, respectively), show no evidence of significant binding, and show clear longitudinal gradients even after 1 h. (G) Purified GFP (12 μM) accumulates weakly in the cytoplasm with respect to the pipette tip with an average time constant of 14 min (n = 6). Fluorescence does not show clear longitudinal gradients. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

As shown in Fig. 7 B, carboxyfluorescein behaves very differently. Fluorescence of the cytoplasm remains substantially less than that of the pipette tip, indicating that binding to cytoplasmic constituents is weak, possibly negligible. The average time constant for equilibration of dye with the cytoplasm is 10 min (n = 6), almost three times less than for sulforhodamine. Notably, the gradient of the dye remains significant after 1 h (see right panel of Fig. 7 B). From the rough estimate that , the diffusion coefficient is about 10−7 cm2/s. Since carboxyfluorescein binds to cytoplasmic constituents less than other small fluorophores, we also analyzed its equilibration in myocytes at 34°C. At the higher temperature, the average time constant was reduced from 10 ± 3 min to 7.4 ± 1 min (n = 4), and the estimated fraction of dye bound in the cytoplasm increased from 0.31 to 0.36.

Fig. 7 C shows results for the Na-selective dye, Asante Sodium Green-2 (ASG2, MW 1100), equilibrated with a myocyte in the absence of extracellular and intracellular Na. While the dye exhibits very little fluorescence without Na in water, it fluoresces strongly as it diffuses into myocytes in the absence of Na. Clearly, it binds constituents of the cytoplasm and fluoresces as a result. The time constant of equilibration is still longer (38 min) than that of sulforhodamine and the longitudinal gradient remains strong after 1 h. The results demonstrate that ASG2 is not a Na-selective dye in the myocyte environment. Since it has negligible fluorescence in the pipette, we cannot estimate the extent to which it binds. However, even if 90% is bound in myocytes, the diffusion constant must be <10−7 cm2/s to account for the time course.

Fig. 7, D–F, presents the diffusion into myocytes of three FITC-labeled PEGs of increasing MW. As shown in Fig. 7 D, a 0.5 kD FITC-PEG equilibrates with the cytoplasm with a time constant of 11 min (n = 6), more slowly than carboxyfluorescein but more rapidly than sulforhodamine. There was no accumulation in the cytoplasm versus the pipette tip, and the longitudinal gradient remained strong after 1 h. Diffusion of a 2-kD PEG (Fig. 7 E) was slower by a factor of 2 (23-min time constant), and a 10-kD PEG (Fig. 7 F) diffused similarly to the 2-kD PEG (time constant, 15 min; n = 6).

Surprisingly, an isolated GFP protein (Fig. 7 G) diffused into myocytes with roughly the same time course as the 2-kD PEG (see panel F), and the GFP fluorescence did not show pronounced gradients during the 1 h time course examined. However, the magnitude of the cytoplasmic fluorescence remained more than sevenfold less than the GFP fluorescence in the pipette tip. We note that discrepancies in the diffusion of fluorescent molecules with respect to MW have been reported previously for cardiac myocytes (Illaste et al., 2012). We speculate in the Discussion that this might reflect at least in part facilitated transport involving protein–protein interactions. We document in Fig. S2 that 2-kD PEGs with an added positive amino group or an added negative COOH group did not diffuse differently from the neutral PEG. We also document that an AlexaFluor488-labeled albumin (66 kD) diffused similarly to GFP and that a 4,400 MW TRITC-labeled dextran equilibrated similarly to 10K PEG.

Diffusion of four additional fluorescent molecules into the cytoplasm of patch-clamped murine myocytes. Same experimental conditions as Figs. 6 and 7. Dashed lines indicate the positions of the line scans shown at right. Yellow dots indicate the end of the myocyte in proximity to the pipette tip. (A) 2 kD FITC-labeled PEG with one amino group (100 μM). (B) 2 kD FITC-labelled PEG with one carboxyl group (100 μM). (C) 4.4 kD TRITC-labeled dextran (10 μM). (D) AlexaFluor488-labeled albumin (100 μM). Time constants determined for the positively and negatively charged PEGs were not significantly different. The 4-kD dextran equilibrates significantly slower, but fluorescent albumin diffuses quite rapidly. Similar to results for GFP (Fig. 7), however, the fluorescent albumin fluorescence remains substantially lower than pipette fluorescence. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

Diffusion of four additional fluorescent molecules into the cytoplasm of patch-clamped murine myocytes. Same experimental conditions as Figs. 6 and 7. Dashed lines indicate the positions of the line scans shown at right. Yellow dots indicate the end of the myocyte in proximity to the pipette tip. (A) 2 kD FITC-labeled PEG with one amino group (100 μM). (B) 2 kD FITC-labelled PEG with one carboxyl group (100 μM). (C) 4.4 kD TRITC-labeled dextran (10 μM). (D) AlexaFluor488-labeled albumin (100 μM). Time constants determined for the positively and negatively charged PEGs were not significantly different. The 4-kD dextran equilibrates significantly slower, but fluorescent albumin diffuses quite rapidly. Similar to results for GFP (Fig. 7), however, the fluorescent albumin fluorescence remains substantially lower than pipette fluorescence. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

Fluorophore diffusion in BL6 murine myocytes

| Fluorophore (MW, kD) . | T (°C) . | HR (nm) . | Fmyo/pip . | Fbound . | DX (cm2/s) . | DX-free (cm2/s) . | DX-H2O (cm2/s) . | Fold reduction . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodipy-FL-ATP (0.88) | 24 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.4 × 10−7 | 0.57 × 10−7 | 4.5 × 10−6a | >70 |

| Carboxyfluorescein (0.38) | 24 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 1.7 × 10−7 | 4.8 × 10−6b | 28 |

| Carboxyfluorescein (0.38) | 34 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 3.2 × 10−7 | 5.0 × 10−7 | 4.8 × 10−6b | 10 |

| Sulforhodamine (0.56) | 24 | 0.74 | 5.0 | 0.93 | 0.3 × 10−7 | 4.3 × 10−7 | 4.0–4.4 × 10−6c | 10 |

| TRITC-dextran (4.4) | 24 | 1.44 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.4 × 10−7 | 0.78 × 10−7 | 1.5 × 10−6d | 19 |

| 0.5 kD PEG (0.83) | 24 | 0.84 | 0.38 | 0.12 | 1.1 × 10−7 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 3 × 10−6e | 25 |

| 2 kD PEG (2.3) | 24 | 1.16 | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.5 × 10−7 | 1.3 × 10−7 | 6 × 10−7e | 46 |

| 2 kD PEG-NH3 (2.3) | 24 | 1.16 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.33 × 10−7 | 0.48 × 10−7 | --- | ---- |

| 10 kD PEG (10.3) | 24 | 1.90 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.9 × 10−7 | 3.1 × 10−7 | 2.5 × 10−7e | 8 |

| Fluorophore (MW, kD) . | T (°C) . | HR (nm) . | Fmyo/pip . | Fbound . | DX (cm2/s) . | DX-free (cm2/s) . | DX-H2O (cm2/s) . | Fold reduction . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodipy-FL-ATP (0.88) | 24 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.4 × 10−7 | 0.57 × 10−7 | 4.5 × 10−6a | >70 |

| Carboxyfluorescein (0.38) | 24 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 1.7 × 10−7 | 4.8 × 10−6b | 28 |

| Carboxyfluorescein (0.38) | 34 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 3.2 × 10−7 | 5.0 × 10−7 | 4.8 × 10−6b | 10 |

| Sulforhodamine (0.56) | 24 | 0.74 | 5.0 | 0.93 | 0.3 × 10−7 | 4.3 × 10−7 | 4.0–4.4 × 10−6c | 10 |

| TRITC-dextran (4.4) | 24 | 1.44 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.4 × 10−7 | 0.78 × 10−7 | 1.5 × 10−6d | 19 |

| 0.5 kD PEG (0.83) | 24 | 0.84 | 0.38 | 0.12 | 1.1 × 10−7 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 3 × 10−6e | 25 |

| 2 kD PEG (2.3) | 24 | 1.16 | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.5 × 10−7 | 1.3 × 10−7 | 6 × 10−7e | 46 |

| 2 kD PEG-NH3 (2.3) | 24 | 1.16 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.33 × 10−7 | 0.48 × 10−7 | --- | ---- |

| 10 kD PEG (10.3) | 24 | 1.90 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.9 × 10−7 | 3.1 × 10−7 | 2.5 × 10−7e | 8 |

All values are a mean of four or more measurements. From left to right: Column 1: Fluorophore analyzed. Column 2: Temperature of observations. Column 3: Hydrodynamic radius. Column 4: Ratio of fluorescence of pipette solution to myoplasm in close proximity after >20 min (Fmyo/pip). Values for BSA and GFP were 0.07 and 0.15, respectively, indicating exclusion from myoplasm. Column 5: Estimated fractions of fluorophores bound by cytoplasm, assuming the free cytoplasmic space to be one-third of total myocyte volume (Lu et al., 2016). . Column 6: Estimated diffusion coefficients for total fluorophores. with λmyo = 0.012 cm. Column 7: Diffusion coefficients for unbound fluorophore, estimated as . Column 8: Estimated diffusion coefficients for given compounds in free water. Column 9: Estimated fold reduction of diffusion coefficients of unbound compounds in murine myocyte cytoplasm versus water (Dx-H2O/Dx-free).

Gendron et al., 2008 describes diffusion coefficients for multiple rhodamine derivatives.

Our estimate for Bodipy-FL-ATP, 0.45 × 10−7 cm2/s (Table 1) is smaller still than the values for other fluorescent ATP analogues determined in rat myocytes (Illaste et al., 2012). Possibly, this difference reflects species differences (e.g., a greater mitochondrial volume in murine myocytes), and our finding of differences in diffusion between mouse strains (Fig. 14) appears consistent with this possibility. Our coefficients for carboxyfluorescein are 1.2 and 3.2 × 10−7 cm2/s at 24 and 34°C, respectively. Column 8 gives the diffusion coefficients for each dye in free water, and Column 9 gives our best estimates of diffusion restriction of free fluorophores in the cardiac myocyte cytoplasm versus free water. Diffusion coefficients were reduced from 8-fold to >70-fold in myoplasm. We note that the degree of restriction did not correlate significantly with hydrodynamic radius for the fluorophores examined. From the data for carboxyfluorescein, it would appear that diffusion restrictions are about threefold greater at 24°C than at 34°C.

Unrestricted Na diffusion in murine myocytes

Fig. 8 examines Na diffusion in murine cardiac myocytes using a protocol that is closely related to protocols recently described to support the existence of local Na gradients (Skogestad et al., 2019). In brief, Na channels are used to load myocytes with known amounts of Na, and the dissipation of Na is monitored either via Na/K pump current (Fig. 8 A) or via Na channels themselves (Fig. 8 B). In panel A, the myocyte was initially patch-clamped with NMG as the sole monovalent cation in the patch pipette. The extracellular solution contained 130 mM NMG with 7 mM Na to suppress pump current generated by contaminating K in standard solutions (Lu et al., 2016). To activate Na/K pump current, 7 mM Na is substituted for 7 mM K. Initially, this protocol generates no detectable pump current, indicating that cytoplasmic Na was effectively depleted from the myocytes. Subsequently, the NaV channel opener, veratridine (3 μM; Zong et al., 1992), was applied together with 120 mM extracellular Na. An inward Na current of about 1 nA developed routinely within 10 s and decayed by about 15% over 80 s. When Na and veratridine were subsequently removed, an outward current of ∼90 pA developed and decayed with a time constant of about 5 s. This current likely represents reverse Na current through NaV channels, and the time course of decay likely reflects a rather rapid veratridine dissociation from cardiac myocyte NaV channels.

Na exchange in patch-clamped murine myocytes using veratridine to induce a large Na influx (35°C). (A) Na exchange estimated from Na/K pump currents. 120 mM NMG-Aspartate on both sides. The extracellular solution contains additionally 7 mM Na or 7 mM K. NMG-Aspartate is exchanged for Na-Aspartate with 3 μM veratridine on the outside. The ∼1 nA inward Na current decays partially, followed by generation of transient outward current upon removal of Na and veratridine. Thereafter, large Na/K pump currents are activated by exchanging 7 mM Na for 7 mM K, and peak currents decay with a time constant of 22 s. Red curves show simulations of Na exchange to a 12 pl cytoplasmic volume. Veratridine dissociates at 0.2 s−1 and pump current is proportional to a Hill equation with a slope of 1.6 (Zong et al., 1992). Peak Na pump current magnitudes determined experimentally are plotted with the simulated pump availability. (B) Na exchange estimated from veratridine-activated Na current. In the presence of veratridine (3 μM), inward Na currents decay partially and outward (reverse) Na currents decay completely with a time constant of 22 s after Na removal. The right panel plots the outward Na current magnitude (y axis) that occurred just after removing extracellular Na in dependence on the time that extracellular Na had been applied (x axis). This time constant, also 22 s, with strong probability reflects the time course over which cytoplasmic Na exchanges with the pipette tip. Simulations assume that Na turnover is determined solely by the pipette access resistance.

Na exchange in patch-clamped murine myocytes using veratridine to induce a large Na influx (35°C). (A) Na exchange estimated from Na/K pump currents. 120 mM NMG-Aspartate on both sides. The extracellular solution contains additionally 7 mM Na or 7 mM K. NMG-Aspartate is exchanged for Na-Aspartate with 3 μM veratridine on the outside. The ∼1 nA inward Na current decays partially, followed by generation of transient outward current upon removal of Na and veratridine. Thereafter, large Na/K pump currents are activated by exchanging 7 mM Na for 7 mM K, and peak currents decay with a time constant of 22 s. Red curves show simulations of Na exchange to a 12 pl cytoplasmic volume. Veratridine dissociates at 0.2 s−1 and pump current is proportional to a Hill equation with a slope of 1.6 (Zong et al., 1992). Peak Na pump current magnitudes determined experimentally are plotted with the simulated pump availability. (B) Na exchange estimated from veratridine-activated Na current. In the presence of veratridine (3 μM), inward Na currents decay partially and outward (reverse) Na currents decay completely with a time constant of 22 s after Na removal. The right panel plots the outward Na current magnitude (y axis) that occurred just after removing extracellular Na in dependence on the time that extracellular Na had been applied (x axis). This time constant, also 22 s, with strong probability reflects the time course over which cytoplasmic Na exchanges with the pipette tip. Simulations assume that Na turnover is determined solely by the pipette access resistance.

Immediately, after removal of Na and veratridine, a large 1 nA Na/K pump current can be activated by applying extracellular K in the same manner as before Na loading. K was applied and removed four additional times to determine the time course with which Na is lost from the myocyte via the patch pipette. From these records, we determined the magnitudes of peak pump currents at the nine points, as indicated, and the corresponding times after removal of Na and veratridine. The peak currents were fit to a single decaying exponential, and the time constant of current decay was determined by least-squares fitting to be 22 s. This value is very similar to results for other protocols used to estimate the time course of Na equilibration with patch pipettes (Lu and Hilgemann, 2017). We note that the more rapid decay of Na/K pump current that occurs during application of extracellular K probably reflects an autoinhibition mechanism of murine cardiac Na/K pumps (Lu and Hilgemann, 2017).

The red curves below the current trace in Fig. 8 A are a simple reconstruction of Na homeostasis in these experiments. It is assumed that Na equilibrates instantly within the entire cytoplasm and that Na exchange with the pipette tip occurs with a time constant of 22 s. This time course is accurately predicted when a pipette access resistance of 4.2 MΩ is simulated as a nonselective conductance and the myocyte mixing volume is assumed to be 12 pl (Lu and Hilgemann, 2017). Na escapes from the cell exclusively via the patch pipette tip. Although no Na pumping is included, Na/K pump availability is simulated by a Hill equation with a half-maximal Na concentration of 6 mM and a Hill coefficient of 1.6, as defined experimentally for this condition without cytoplasmic K (Lu et al., 2016). Finally, we simulated veratridine binding and dissociation from the myocyte to occur with a time constant of 5 s. With these simple assumptions, the simulation reproduces the experimental results with good accuracy.

Fig. 8 B illustrates a second protocol that should reveal subsarcolemmal Na accumulation, if it occurs. In this protocol, veratridine was applied continuously in the presence of NMG as the sole monovalent cation inside and outside the myocyte. Then, Na (120 mM) was applied instead of NMG on the outside, and inward Na currents of about 1.5 nA were generated. The inward current decays by 15%. The average time constant, determined by fitting the individual current records to single exponential functions, was 22 s. The outward current, which develops upon removal of extracellular Na, also decays with a time constant of 22 s. As shown in the right panel of Fig. 8 B for repeated Na applications, removal of Na at different times verifies that the outward Na current develops with the same time course as the inward current decays. The red curves in panel B of Fig. 8 show a simple reconstruction of Na homeostasis in this experiment, assuming that Na equilibrates instantly within the myocyte and exchanges to the patch pipette with a time constant of 22 s from a mixing volume of 12 pl. The results give no evidence for complexities beyond those represented.

In Fig. S3, we describe equivalent experiments using myocytes loaded with CoronaGreen AM Na-selective dye (5 μM for 30 min at 25°C; Iamshanova et al., 2016). CoronaGreen fluorescence changes in similar experiments (n > 20) were in general of small magnitude in relation to signal drift and bleaching. We provide an example in which fluorescence changes seemed reliable. They occurred with a time constant of ∼30 s. We mention in connection with these experiments that the average equilibration time constant, determined as in Fig. 8 B, increased by a factor of 3.0 at 24°C versus 35°C (P < 0.05; n = 5), whereas the access resistance increased by only a factor of 1.5 (n = 5). Possibly, therefore, the cardiac myoplasm becomes relatively more restrictive to Na diffusion at lower temperatures.

Optical measurement of Na concentration changes during and after Na influx activated by veratridine (3 μM). Myocytes were loaded with CoronaGreen AM Na-selective dye (5 μM AM) for 30 min at 25°C (Iamshanova et al., 2016). Myocytes were patch-clamped using Na-free NMG solutions as in Fig. 8. Na was applied and removed multiple times without veratridine and subsequently with veratridine. In the presence of extracellular Na (120 mM), cytoplasmic CoronaGreen fluorescence increases by ∼5% and decreases again upon removal of extracellular Na. Fluorescence changes increase by about a factor of two in the presence of veratridine. Each fluorescence response was fit to falling or rising exponential functions (red curves), and the average time constant amounted to 28 s. The magnitudes of fluorescence changes (5–10%) are consistent with Na changes of 2–4 mM, assuming that CoronaGreen has a dissociation constant (Kd) of 10 mM for Na.

Optical measurement of Na concentration changes during and after Na influx activated by veratridine (3 μM). Myocytes were loaded with CoronaGreen AM Na-selective dye (5 μM AM) for 30 min at 25°C (Iamshanova et al., 2016). Myocytes were patch-clamped using Na-free NMG solutions as in Fig. 8. Na was applied and removed multiple times without veratridine and subsequently with veratridine. In the presence of extracellular Na (120 mM), cytoplasmic CoronaGreen fluorescence increases by ∼5% and decreases again upon removal of extracellular Na. Fluorescence changes increase by about a factor of two in the presence of veratridine. Each fluorescence response was fit to falling or rising exponential functions (red curves), and the average time constant amounted to 28 s. The magnitudes of fluorescence changes (5–10%) are consistent with Na changes of 2–4 mM, assuming that CoronaGreen has a dissociation constant (Kd) of 10 mM for Na.

Restricted ATP diffusion in murine myocytes

We next address the diffusion of ATP in functional experiments with murine myocytes. Fig. 9 presents two initial observations consistent with ATP diffusing in a more restricted manner than Na, although less restricted than fluorophores. Given that these protocols perturb ATP metabolism, we subsequently describe two additional protocols that allow us to track ATP diffusion functionally.

Functional analysis of nucleotide turnover between murine myocyte cytoplasm and patch clamp pipette tip (35°C). (A) Pipette perfusion of AMPPNP. A rapid pipette perfusion technique (Hilgemann and Lu, 1998) was used to apply and remove nonhydrolyzable ATP, AMPPNP, from the cytoplasmic side. The pipette contained 4 mM ATP and 80 mM Na throughout. During continuous pump activation with 7 mM K, AMPPNP (2 mM) perfusion inhibits the pump current with a time constant of 25 s. Pumps reactivate with a time constant of 160 s (gray curves) during AMPPNP removal, and the protocol repeats accurately. Gray curves are single exponential functions, fit to results. The red curve in A simulates results with a diffusion coefficient of 3 × 10−7 cm2/s into and out of a 120 μM long cylinder, open at one end. The dissociation constant of AMPPNP was 5 μM and that of ATP was 50 μM. (B) Pump current changes after myocyte opening in the presence and absence of ATP in the patch pipette. Pump currents were activated repeatedly for just 2 s to ensure that pump activity did not deplete cytoplasmic Na. Pump currents with ATP decreased by 10% over 10 min, while pump currents without ATP decreased by 65%. Without ATP, currents decayed to negligible values in all experiments within 15 min. The final phase of current decay had a time constant of 177 s on average (n = 6; red curve). The time course of decay is simulated (gray curve) with the following assumptions: (1) The initial myocyte ATP concentration is 8 mm, (2) ATP activates Na/K pumps with a K50 of 50 μM, (3) the cytoplasm contains 120 μM of ATP binding sites with a Kd of 50 μM, (4) the diffusion coefficient of free ATP is 8 × 10−7 cm2/s, (5) the myocyte is 120 μm long, and (6) the pipette access resistance does not limit ATP diffusion out of the myocyte. ***P < 0.001.