β-coronavirus rearranges the host cellular membranes to form double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) via NSP3/4, which anchor replication–transcription complexes (RTCs), thereby constituting the replication organelles (ROs). However, the impact of specific domains within NSP3/4 on DMV formation and RO assembly remains largely unknown. By using cryogenic-correlated light and electron microscopy (cryo-CLEM), we discovered that the N-terminal and C-terminal domains (NTD and CTD) of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 are essential for DMV formation. Nevertheless, the CTD of NSP4 is not essential for DMV formation but regulates the DMV numbers. Additionally, the NTD of NSP3 is required for recruiting the RTC component to the cytosolic face of DMVs through direct interaction with NSP12 to assemble ROs. Furthermore, we observed that the size of NSP3/4-induced DMVs is smaller than virus-induced DMVs and established that RTC-mediated synthesis of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) cargo plays a crucial role in determining DMV size. Collectively, our findings reveal that β-coronaviruses exploit the NSP3/4/12 axis to establish the viral ROs.

Introduction

Positive-strand RNA viruses exploit viral integral membrane proteins, hijacking host factors to remodel intracellular membranes to generate replicative structures for RNA replication (Miller and Krijnse-Locker, 2008). Two major classes of replicative structures have been identified thus far: spherular membrane invaginations called spherules, induced by alphaviruses, nodaviruses, flaviviruses, and many other positive-strand RNA viruses, and double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) formed by β-coronaviruses and the flavivirus-related hepatitis C virus (Miller and Krijnse-Locker, 2008). These replication vesicles are tightly packed with the dsRNA, presumably functioning as the genomic RNA replication intermediate during viral RNA synthesis (Klein et al., 2020; Knoops et al., 2008; Wolff et al., 2020).

SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is a positive-strand RNA virus belonging to the β-coronavirus family, which includes SARS-CoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus, and seasonal coronaviruses (V’Kovski et al., 2021). Upon entering host cells, the genomic RNA of β-coronavirus is translated into two large polyproteins ORF1a and ORF1b, which are processed by viral papain-like proteinase (PLpro) residing in NSP3 and the 3C-like main proteinase in NSP5, resulting in the production of 16 NSPs, NSP1–16 (V’Kovski et al., 2021). NSP1 functions to shut down host translation and promote host mRNA degradation (Schubert et al., 2020; Thoms et al., 2020), while NSP3–16 play a role in establishing the viral replication organelles (ROs) (V’Kovski et al., 2021). The exact function of NSP2 is not fully understood. Among these 16 NSPs, NSP3, NSP4, and NSP6 contain multiple hydrophobic and membrane-spanning domains (Angelini et al., 2013). Previous studies have demonstrated that ectopic expression of NSP3/4 alone is sufficient to induce DMVs and convoluted membranes that resemble to some extent the replicative structures as have been observed in infected cells (Angelini et al., 2013; Ji et al., 2022; Oudshoorn et al., 2017), whereas NSP6 acts as an organizer of DMV clusters and mediates contact with lipid droplets (Ricciardi et al., 2022). In addition, a molecular pore spanning the DMV has been identified through in situ cryogenic electron tomography (cryo-ET) and proposed as a viral RNA export channel in β-coronavirus–infected cells (Wolff et al., 2020). Further investigation disclosed that the NSP3/4 are the minimal components required for the formation of a DMV-spanning pore (Zimmermann et al., 2023). Recently, the cryo-ET and subtomogram averaging in isolated DMVs revealed the molecular architecture of DMV pore complex, which comprises 12 copies each of NSP3 and NSP4 and is organized in four concentric stacking hexamer rings (Huang et al., 2024). However, the impact of specific domains within NSP3/4 on DMV formation remains largely unknown.

The viral replication–transcription complexes (RTCs) are composed of multiple viral NSPs, including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp, NSP12), helicase (NSP13), dual exonuclease/N7-methyltransferase (NSP14), 2′-O-methyltransferase (NSP16), and several accessory/cofactor subunits (NSP7, NSP8, NSP9, and NSP10), which function in RNA synthesis, RNA modification, and RNA proofreading (Hillen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2021a, 2021b). NSP12, along with its two cofactors NSP7 and NSP8, mediates RNA synthesis (Hillen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020), while NSP13, NSP14, and NSP16 are involved in 5′ RNA capping formation and RNA modification (Yan et al., 2021b). Notably, NSP14 also provides a 3–5′ exonuclease activity that assists RNA synthesis with a unique RNA proofreading function (V’Kovski et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021b). Mounting evidence suggests that the RTCs localize to DMVs (Hagemeijer et al., 2010; Knoops et al., 2008; V’Kovski et al., 2019). However, the process by which RTCs assemble within DMVs remains largely unknown. Whether the RTCs localize in the interior or the exterior of DMVs needs to be clarified. Moreover, the size of NSP3/4-induced DMVs (∼100 nm) is smaller than virus-induced DMVs (∼300 nm) (Ji et al., 2022; Ricciardi et al., 2022). It is necessary to explore the involvement of other NSPs in DMV formation.

In this study, we systemically analyzed the effect of specific domains and mutations of NSP3 and NSP4 on the DMV formation by using cryo-CLEM. We discovered that the N-terminal and C-terminal domains (NTD and CTD) of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 are essential for DMV formation. Nevertheless, the CTD of NSP4 is not essential for DMV formation but regulates the number of DMVs. In addition, the NTD of NSP3 is required for the recruitment of RTC to the exterior of NSP3/4-induced DMVs through the NSP3/NSP12 axis, leading to the formation of the ROs. Finally, we find that the size of DMVs is determined by the presence dsRNA cargo rather than other viral NSPs.

Results and discussion

Co-expression of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3/4 in trans is sufficient for the formation of the pore complex on DMVs

To determine the ultrastructure of DMVs induced by SARS-CoV-2 NSP3/4, we performed cryo-ET on cryo-focused ion beam milled lamellae in transfected cells co-expressing SARS-CoV-2 GFP-NSP3 and NSP4-mCherry. To increase the targeting efficiency, the lamellae were prepared by a cryogenic correlated light, ion, and EM (cryo-CLIEM) technique under the guidance of 3D confocal imaging (Fig. S1, A–G), which was developed by our colleagues (Li et al., 2023). Confocal imaging revealed that GFP-NSP3 co-localized with NSP4-mCherry, forming punctate structures (Fig. S1 A). Subsequently, cryo-ET results showed that the NSP3/4+ puncta consisted of multiple DMVs with an average diameter of 100 nm (Fig. 1, A–C), consistent with previous findings (Ji et al., 2022). 3D segmentations revealed that DMVs were frequently connected to zippered ER membranes, with ribosome observed in the DMV lumen (Fig. 1 C and Video 1), indicating that DMVs originated from ER membranes. No filamentous material was identified in the lumen of the NSP3/4-induced DMVs (Fig. 1 C), compared with virus-induced DMVs. Strikingly, a clear crown-shaped pore complex spanning the double membranes was observed in the NSP3/4-induced DMVs (Fig. 1, D and E). Subtomogram averaging revealed a sixfold symmetry structure of the pore complex (Fig. 1, F and G), similar to the pore complex in virus-induced DMVs (Wolff et al., 2020). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the co-expression of NSP3/4 in trans is sufficient for the formation of the pore complex on DMVs.

Workflow of cryo-CLIEM of NSP3/NSP4-induced DMVs, confocal analysis of the co-localization of different truncations of NSP3/NSP4 in HeLa cells, and TEM images of DMV in HEK-293T cells, related to Fig. 1 . (A) Co-localization signals of fluorescent GFP-nsp3 and nsp4-mCherry were observed in the vitrified HeLa cells, serving as a marker for the identification of regions containing DMVs. Scale bar, 20 μm. (A1) FIB image of the corresponding area in panel A. The blue arrow indicates the target cell, corresponding to the white box in A. (B) Cryo-FM image of the pre-lamella (∼400 nm) via FIB milling direction. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Cryo-FM image of the final lamella (∼150 nm). Scale bars, 10 μm. (D) The final lamella viewed from FIB milling direction. (E) The SEM image of the final lamella. (F and G) The cryo-EM image of the lamella, containing the DMVs of interest (white-dotted frame). LD, lipid droplet; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; NPC, nuclear pore complex; Mito, mitochondrion. Scale bar, 2 μm (F), 1 μm (G). (H) Confocal microscopy analysis of the co-localization of different truncations of NSP3/NSP4 in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (I) Conventional TEM images of DMV in HEK-293T cells induced by GFP-NSP3-T2A-NSP4(WT)-mCherry and GFP-NSP3-T2A-NSP4(ΔCTD)-mCherry. Scale bar, 500 nm. (J) Statistical analysis of DMV numbers per cell. N = 3, n = 16, 17 (N indicate the number of independent experiments and n indicate the number of total measurements or observations). All data are shown as mean ± SEM, Student’s two-tailed t test, *: P < 0.05, significant.

Workflow of cryo-CLIEM of NSP3/NSP4-induced DMVs, confocal analysis of the co-localization of different truncations of NSP3/NSP4 in HeLa cells, and TEM images of DMV in HEK-293T cells, related to Fig. 1 . (A) Co-localization signals of fluorescent GFP-nsp3 and nsp4-mCherry were observed in the vitrified HeLa cells, serving as a marker for the identification of regions containing DMVs. Scale bar, 20 μm. (A1) FIB image of the corresponding area in panel A. The blue arrow indicates the target cell, corresponding to the white box in A. (B) Cryo-FM image of the pre-lamella (∼400 nm) via FIB milling direction. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Cryo-FM image of the final lamella (∼150 nm). Scale bars, 10 μm. (D) The final lamella viewed from FIB milling direction. (E) The SEM image of the final lamella. (F and G) The cryo-EM image of the lamella, containing the DMVs of interest (white-dotted frame). LD, lipid droplet; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; NPC, nuclear pore complex; Mito, mitochondrion. Scale bar, 2 μm (F), 1 μm (G). (H) Confocal microscopy analysis of the co-localization of different truncations of NSP3/NSP4 in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (I) Conventional TEM images of DMV in HEK-293T cells induced by GFP-NSP3-T2A-NSP4(WT)-mCherry and GFP-NSP3-T2A-NSP4(ΔCTD)-mCherry. Scale bar, 500 nm. (J) Statistical analysis of DMV numbers per cell. N = 3, n = 16, 17 (N indicate the number of independent experiments and n indicate the number of total measurements or observations). All data are shown as mean ± SEM, Student’s two-tailed t test, *: P < 0.05, significant.

The NTD and CTD of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3, yet not the CTD of NSP4 are essential for the formation of DMVs. (A) Tomographic slice of HeLa cells transfected with GFP-NSP3 and NSP4-mCherry, demonstrating the formation of DMVs induced by the overexpression of NSP3 and NSP4. The DMVs are connected with ribosome-decorated ER (blue arrowheads indicate the connections). Scale bar, 200 nm. (B) 3D rendering of the tomogram shown in A, illustrating the overall structure of the NSP3/4-induced DMVs. (C) Gallery of NSP3/4-induced DMVs, highlighting the connection of the outer membrane of DMVs with the ER (dark blue arrowheads). Neck-like connections (yellow arrowhead), the presence of ribosomes inside DMVs (purple arrowhead), and two fused DMVs (the last right panel) are also observed. Scale bar, 100 nm. (D) Enlarged view of the white-boxed area in A, revealing the presence of pore complexes in NSP3/4-induced DMVs (green arrowhead). Scale bar, 100 nm. (E) Averaged slices of a tomogram showing a zoom in area of one DMV pore as observed in D. Scale bar, 20 nm. (F and G) Different views of the sixfold-symmetrized subtomogram average of the pore complexes in NSP3/4-induced DMVs. (H and I) Tomographic slices of HeLa cells transfected with different truncations of NSP3/4, showing that the NTD or CTD truncations of NSP3, but not the CTD truncation of NSP4 impairs the DMV formation. Scale bar, 100 nm. (J) Zoom in area in I at higher magnification. Green arrowhead, DMV. Scale bar, 100 nm.

The NTD and CTD of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3, yet not the CTD of NSP4 are essential for the formation of DMVs. (A) Tomographic slice of HeLa cells transfected with GFP-NSP3 and NSP4-mCherry, demonstrating the formation of DMVs induced by the overexpression of NSP3 and NSP4. The DMVs are connected with ribosome-decorated ER (blue arrowheads indicate the connections). Scale bar, 200 nm. (B) 3D rendering of the tomogram shown in A, illustrating the overall structure of the NSP3/4-induced DMVs. (C) Gallery of NSP3/4-induced DMVs, highlighting the connection of the outer membrane of DMVs with the ER (dark blue arrowheads). Neck-like connections (yellow arrowhead), the presence of ribosomes inside DMVs (purple arrowhead), and two fused DMVs (the last right panel) are also observed. Scale bar, 100 nm. (D) Enlarged view of the white-boxed area in A, revealing the presence of pore complexes in NSP3/4-induced DMVs (green arrowhead). Scale bar, 100 nm. (E) Averaged slices of a tomogram showing a zoom in area of one DMV pore as observed in D. Scale bar, 20 nm. (F and G) Different views of the sixfold-symmetrized subtomogram average of the pore complexes in NSP3/4-induced DMVs. (H and I) Tomographic slices of HeLa cells transfected with different truncations of NSP3/4, showing that the NTD or CTD truncations of NSP3, but not the CTD truncation of NSP4 impairs the DMV formation. Scale bar, 100 nm. (J) Zoom in area in I at higher magnification. Green arrowhead, DMV. Scale bar, 100 nm.

Tomogram reconstruction and 3D rendering of DMV induced by NSP3/4 in HeLa cells. Color annotations are consistent with Fig. 1. Orange, DMVs; yellow, ER; purple, mitochondria; green, microtubules; pink, ribosomes; and blue, actin filaments. Related to Fig. 1.

The NTD and CTD of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3, yet not the CTD of NSP4 are essential for the formation of DMVs

To investigate the impact of the specific domains in the NSP3 or NSP4 on the DMV formation, we carried out cryo-CLEM in transfected cells co-expressing different truncations of NSP3/4, including NSP3 1–1546 (ΔCTD), NSP3 1–1496 (ΔTMD2-4 and CTD), NSP3 1392–1946 (ΔNTD), and NSP4 1–385 (ΔCTD). Confocal imaging revealed that all the truncations of GFP-NSP3 and NSP4-mCherry form punctate structures with WT NSP4 or NSP3, respectively (Fig. S1 H). Cryo-CLEM results showed that co-expression of all the NSP3 truncations with WT NSP4 could not form DMVs (Fig. 1 H). NSP3 1–1546 and NSP3 1–1496 with WT NSP4 form large double-membrane whorl-like structures (Fig. 1 H), similar to the uncleaved NSP3/4-induced structures (Zimmermann et al., 2023). NSP3 1391–1946 with WT NSP4-induced CM-like structures (Fig. 1 H), similar to the virus infection-induced CM structures (Ulasli et al., 2010). Previous research showed that removal of Ubl1-Mac1 domains does not abrogate DMV formation, yet removal of Ubl1–Ubl2 domains leads to membrane remodeling and impairs the formation of DMVs (Zimmermann et al., 2023). Our study showed that removal of NAB-β2M domains also hampers the DMV formation (Fig. 1 H), indicating that the specific domains from MAC2 to β2M in the NTD is required for DMV formation. Remarkably, co-expression of the NSP4 1–385 with WT NSP3 could form canonical DMVs (Fig. 1, I and J), indicating the CTD of NSP4 is not crucial for the DMV formation. However, the number of DMVs is significantly decreased in the cells co-expressing NSP4 1–385 (ΔCTD) with WT NSP3 compared with the WT NSP3/4 cells (Fig. S1, I and J), suggesting that CTD of NSP4 plays a role in the regulation of DMV numbers.

The RTC components are recruited to the DMVs through the NSP3–NSP12 axis

To elucidate the assembly of RTC components in DMVs, other SARS-CoV-2 NSPs fused with fluorescent proteins at either the N terminus or C terminus were examined for recruitment by NSP3/4-induced DMVs. Microscopy results showed that when expressed individually, all NSPs diffused in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. S2 A), except for the mCherry-NSP6, which showed a punctate structure (Fig. S2 A), consistent with the previous results of NSP6-induced zippered ER (Ricciardi et al., 2022). Co-expression of NSP3/4 with other NSPs revealed that only NSP12 co-localized with NSP3/4+ puncta (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S2 B), indicating that NSP12 could be recruited to NSP3/4-induced DMVs. To further investigate whether NSP12 is recruited by NSP3 or NSP4, we examined the co-localization of NSP12 with NSP3 or NSP4. Co-expression of NSP3 with NSP12 resulted in the recruitment of NSP12 to the ER, where it co-localized with NSP3 (Fig. 2 B). However, co-expression of NSP4 with NSP12 showed that NSP12 remained diffused in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 2 C), similar to its localization when expressed alone, and did not co-localize with NSP4, indicating that NSP12 interacts with NSP3, but not with NSP4. Moreover, Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) results showed that NSP12 was pulled down by NSP3 but not by NSP4 (Fig. 2 D). Reversely, NSP3, rather than NSP4, could be pulled down by NSP12 (Fig. 2 E), further indicating the interaction between NSP3 and NSP12. To rule out any potential artifacts caused by overexpression, the interaction between NSP3 and NSP12 was verified in SARS-CoV-2–infected cells (Fig. 2 F). Together, these results suggest that NSP12 could be recruited to NSP3/4-induced DMVs through its direct interaction with NSP3.

Other NSPs are not recruited to the NSP3/4-induced DMVs, related to Fig. 2 . (A) Confocal microscopy analysis of the localization of NSP1-mCherry, NSP2-mCherry, GFP-NSP3, NSP4-GFP, NSP5-mCherry, mCherry-NSP6, NSP7-mCherry, NSP8-mCherry, NSP9-mCherry, NSP10-mCherry, NSP11-mCherry, NSP12-mCherry, NSP13-mCherry, NSP14-mCherry, NSP15-mCherry, and NSP16-mCherry in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Confocal microscopy analysis of the co-localization of Flag-NSP3/NSP4-GFP puncta with NSP1-mCherry, NSP2-mCherry, NSP5-mCherry, NSP7-mCherry, NSP8-mCherry, NSP9-mCherry, NSP10-mCherry, NSP11-mCherry, NSP13-mCherry, NSP14-mCherry, NSP15-mCherry, or NSP16-mCherry in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Other NSPs are not recruited to the NSP3/4-induced DMVs, related to Fig. 2 . (A) Confocal microscopy analysis of the localization of NSP1-mCherry, NSP2-mCherry, GFP-NSP3, NSP4-GFP, NSP5-mCherry, mCherry-NSP6, NSP7-mCherry, NSP8-mCherry, NSP9-mCherry, NSP10-mCherry, NSP11-mCherry, NSP12-mCherry, NSP13-mCherry, NSP14-mCherry, NSP15-mCherry, and NSP16-mCherry in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Confocal microscopy analysis of the co-localization of Flag-NSP3/NSP4-GFP puncta with NSP1-mCherry, NSP2-mCherry, NSP5-mCherry, NSP7-mCherry, NSP8-mCherry, NSP9-mCherry, NSP10-mCherry, NSP11-mCherry, NSP13-mCherry, NSP14-mCherry, NSP15-mCherry, or NSP16-mCherry in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.

NSP12 is recruited to the NSP3/4-induced DMVs through NSP3–NSP12 interaction. (A) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of NSP12-mCherry with Flag-NSP3/NSP4-GFP–induced punctate structures in HeLa cells. Trace outline is used for line-scan analysis of the relative fluorescence intensity of NSP12-mCherry, Flag-NSP3, and NSP4-GFP. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B and C) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of NSP12-mCherry with GFP-NSP3 (B) or NSP4-GFP (C) in HeLa cells. Trace outline is used for line-scan analysis of the relative fluorescence intensity of NSP12-mCherry with GFP-NSP3 or NSP4-GFP. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Co-IP analysis of the interaction of Flag-NSP3 or NSP4-Flag with NSP12-mCherry. Proteins were transiently expressed in HEK-293T cells and immunoprecipitates pulled down by Flag antibody were analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. Flag-vector was used as a negative control. Input represents 5% of the total cell extract used for IP. Molecular weights are in kDa. n = 3 independent experiments. (E) Co-IP analysis of the interaction of NSP12-mCherry with Flag-NSP3 or NSP4-Flag. Proteins were transiently expressed in HEK-293T cells and immunoprecipitates pulled down by mCherry antibody were analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. Flag-vector was used as a negative control. Input represents 5% of the total cell extract used for IP. Molecular weights are in kDa. n = 3 independent experiments. (F) Co-IP analysis of the interaction of NSP12 with NSP3 in the SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero-E6 cells. IgG was used as a negative control. Molecular weights are in kDa. n = 3 independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

NSP12 is recruited to the NSP3/4-induced DMVs through NSP3–NSP12 interaction. (A) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of NSP12-mCherry with Flag-NSP3/NSP4-GFP–induced punctate structures in HeLa cells. Trace outline is used for line-scan analysis of the relative fluorescence intensity of NSP12-mCherry, Flag-NSP3, and NSP4-GFP. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B and C) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of NSP12-mCherry with GFP-NSP3 (B) or NSP4-GFP (C) in HeLa cells. Trace outline is used for line-scan analysis of the relative fluorescence intensity of NSP12-mCherry with GFP-NSP3 or NSP4-GFP. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Co-IP analysis of the interaction of Flag-NSP3 or NSP4-Flag with NSP12-mCherry. Proteins were transiently expressed in HEK-293T cells and immunoprecipitates pulled down by Flag antibody were analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. Flag-vector was used as a negative control. Input represents 5% of the total cell extract used for IP. Molecular weights are in kDa. n = 3 independent experiments. (E) Co-IP analysis of the interaction of NSP12-mCherry with Flag-NSP3 or NSP4-Flag. Proteins were transiently expressed in HEK-293T cells and immunoprecipitates pulled down by mCherry antibody were analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. Flag-vector was used as a negative control. Input represents 5% of the total cell extract used for IP. Molecular weights are in kDa. n = 3 independent experiments. (F) Co-IP analysis of the interaction of NSP12 with NSP3 in the SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero-E6 cells. IgG was used as a negative control. Molecular weights are in kDa. n = 3 independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

NSP12 is the core RTC subunit and interacts with other RTC components (Yan et al., 2021b), which prompted us to explore whether other RTC components could be recruited to DMVs through NSP3–NSP12 axis. We thus co-expressed nsp3/4/12 with other RTC components, including NSP7, NSP8, NSP9, NSP10, NSP13, NSP14, NSP15, and NSP16. Microscopy results showed that all the RTC components partially co-localized with nsp3/4/12+ puncta (Fig. S3), indicating that other RTC components could be recruited to the NSP3/4-induced DMVs through the NSP3/NSP12 axis.

Other NSPs are recruited by the NSP3/4-induced DMVs through NSP12, related to Fig. 2 . Confocal microscopy analysis of the co-localization of GFP-NSP3/NSP4-iRFP, NSP12-tagBFP puncta with NSP7-mCherry, NSP8-mCherry, NSP9-mCherry, NSP10-mCherry, NSP13-mCherry, NSP14-mCherry, NSP15-mCherry, or NSP16-mCherry in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Other NSPs are recruited by the NSP3/4-induced DMVs through NSP12, related to Fig. 2 . Confocal microscopy analysis of the co-localization of GFP-NSP3/NSP4-iRFP, NSP12-tagBFP puncta with NSP7-mCherry, NSP8-mCherry, NSP9-mCherry, NSP10-mCherry, NSP13-mCherry, NSP14-mCherry, NSP15-mCherry, or NSP16-mCherry in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.

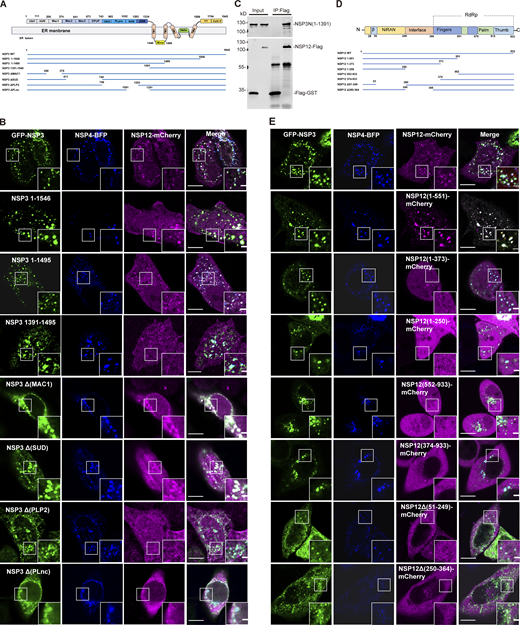

The NTD of NSP3 directly interacts with NSP12

To identify the specific domain within NSP3 required for the interaction with NSP12, various truncations of NSP3 were tested for their ability to recruit NSP12 (Fig. 3 A). Microscopy results showed that all NSP3 truncations formed punctate structures with NSP4, similar to WT NSP3 (Fig. 3 B). Strikingly, NSP12 was recruited to the NSP3/4+ puncta induced by CTD truncations, NSP3 1–1546 and NSP3 1–1495, but not by the NTD truncations, NSP3 1203–1945 and NSP3 1391–1945 (Fig. 3 B), indicating that NSP3 interacts with NSP12 through its cytosolic NTD. In addition, purified NTD of NSP3 protein and NSP12 protein were used in a pull-down assay. Immunoblotting (IB) results revealed a direct interaction between the NTD of NSP3 and NSP12, as NSP12 was pulled down by the NSP3 NTD but not by the control (Fig. 3 C). To further identify the specific domain responsible for this interaction within the NTD, truncations of NSP3 (ΔMAC1, ΔSUD, ΔPLP2, and ΔPLnc) were tested for their ability to recruit NSP12. The findings indicated that the ΔPLP2 and ΔPLnc NSP3 truncations lost the capability to recruit NSP12, while ΔMAC1 and ΔSUD NSP3 truncations retained the ability to recruit NSP12 (Fig. 3 B). These results suggest that the PLP2 and PLnc domains are crucial for the interaction with NSP12.

The NTD of NSP3 directly interacts with NSP12. (A) Schematic representation of the structures of the NSP3 truncations. (B) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of NSP12-mCherry with truncated Flag-NSP3/NSP4-tagBFP–induced punctate structures in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) In vitro pull-down analysis of the interaction between NTD of NSP3 and NSP12. Purified NTD of NSP3 and NSP12 proteins were subjected to pull-down assay and pull-down samples by Flag antibody were analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. Flag-GST protein was used as a negative control. Input represents 5% of the total proteins used for pull-down. Molecular weights are in kDa. n = 3 independent experiments. (D) Schematic representation of the structures of the NSP12 truncations. (E) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of truncated NSP12-mCherry with GFP-NSP3/NSP4-tagBFP–induced punctate structures in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

The NTD of NSP3 directly interacts with NSP12. (A) Schematic representation of the structures of the NSP3 truncations. (B) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of NSP12-mCherry with truncated Flag-NSP3/NSP4-tagBFP–induced punctate structures in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) In vitro pull-down analysis of the interaction between NTD of NSP3 and NSP12. Purified NTD of NSP3 and NSP12 proteins were subjected to pull-down assay and pull-down samples by Flag antibody were analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. Flag-GST protein was used as a negative control. Input represents 5% of the total proteins used for pull-down. Molecular weights are in kDa. n = 3 independent experiments. (D) Schematic representation of the structures of the NSP12 truncations. (E) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of truncated NSP12-mCherry with GFP-NSP3/NSP4-tagBFP–induced punctate structures in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

The structure of β-coronavirus NSP12 contains a nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase (NiRAN) domain, an interface domain and an RdRp domain consisting of fingers, palm, and thumb domains (Gao et al., 2020). To identify the specific domain within NSP12 required for the interaction with NSP3, different truncations of NSP12 were generated, including NSP12 1–551 (including NiRAN, interface and fingers domain), 1–373 (including NiRAN and interface domain), 552–932, and 374–932 (Fig. 3 D). These truncations were tested for their recruitment by NSP3/4-induced DMVs. Microscopy results showed that only the NSP12 1–551 truncation was recruited to the NSP3/4+ puncta (Fig. 3 E). Furthermore, deletion of either NiRAN or interface domain NSP12 could not be recruited to the NSP3/4+ puncta (Fig. 3 E). All these results indicate that the NTD of NSP12, including the NiRAN, interface, and fingers domains, is required for the interaction with NSP3.

The RTC localizes on the cytosolic face of the DMVs

To examine the topology of NSP12 with respect to the DMV membrane, we performed a fluorescence protease protection (FPP) assay. Cells expressing GFP-NSP3, NSP4-tagBFP, and NSP12-mCherry were incubated with digitonin to permeabilize the PM but leave the endo-membranes intact, and then treated with proteinase K (pK). Following digitonin treatment, the cytoplasmic fluorescence of NSP12-mCherry disappeared, while the punctate fluorescent signal of NSP12-mCherry, co-localized with NSP3/4+ puncta, remained stable (Fig. 4 A), further suggesting that NSP12 is associated with the membrane of NSP3/4-induced DMVs. Upon pK treatment, the GFP-NSP3 fluorescence signal was digested immediately, whereas the NSP4-tagBFP fluorescence signal slightly decreased and then remained stable throughout the observation period, suggesting that GFP-NSP3 localizes on the outer membrane of the DMVs and NSP4 localizes in the interior of the DMVs (Fig. 4, A and B), consistent with previous studies (Ji et al., 2022). Strikingly, the punctate fluorescence signal of NSP12-mCherry, similar with GFP-NSP3 fluorescence signal, was also digested immediately (Fig. 4, A and B), suggesting that NSP12 is localized to the cytosolic face of the DMVs.

RTCs localize on the cytosolic face of DMVs. (A and B) In FPP assays, time-lapse images showing the disappearance of GFP-NSP3 and NSP12-mCherry puncta, while most of the NSP4-tagBFP puncta persist upon pK addition in digitonin-permeabilized HeLa cells co-expressing NSP3, NSP4, and NSP12. Scale bar, 10 μm (A). Quantitative data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 4 independent experiments (B). (C) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of MHV-A59 NSP12 with dsRNA after MHV-A59 infection. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) APEX2-based TEM showing RdRp localized on the cytosolic face of DMVs. (1, 2) 17Cl-1 cells expressing APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12 were infected with MHV-A59, fixed, and stained with DAB/H2O2, the DAB polymer generated by APEX2 pinpointing the positions of APEX2-tagged RdRp. (1) Low-magnification transmission electron micrograph. (2) Boxed area in A at higher magnification. Asterisks: DMVs. Arrowheads: DAB polymer (positions of RdRp). mt: mitochondrion. (3 and 4) WT 17Cl-1 cells devoid of APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12 were treated in the same way as in A and B. (3) Low-magnification transmission electron micrograph. (4) Boxed area in C at higher magnification. No DAB polymer was visible. (5, 6) 17Cl-1 cells expressing APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12, mock-infected, fixed, and stained in the same way as in 1 and 2. (5) Low-magnification transmission electron micrograph. (6) Boxed area in 5 at higher magnification. Neither DMV nor APEX2-tagged RdRp recruited to the periphery of DMV was visible. (7–8) 17Cl-1 cells expressing APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12, infected and fixed in the same way as in A and B, but without DAB/H2O2 staining. (7) Low-magnification transmission electron micrograph. (8) Boxed area in G at higher magnification. No DAB polymer is visible. Scale bars: 2 μm for 1, 3, 5, and 7; 200 nm for 2, 4, 6, and 8. (E) Immuno-EM showing that NSP12 is predominantly localized on the cytosolic membranes of DMVs. Upper panel: Negative control for immunogold labeling, where the NSP12 primary antibody was not applied. Lower panel: In immunogold-labeled samples, gold particles (black dots) indicating the position of NSP12 molecules.

RTCs localize on the cytosolic face of DMVs. (A and B) In FPP assays, time-lapse images showing the disappearance of GFP-NSP3 and NSP12-mCherry puncta, while most of the NSP4-tagBFP puncta persist upon pK addition in digitonin-permeabilized HeLa cells co-expressing NSP3, NSP4, and NSP12. Scale bar, 10 μm (A). Quantitative data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 4 independent experiments (B). (C) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the colocalization of MHV-A59 NSP12 with dsRNA after MHV-A59 infection. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) APEX2-based TEM showing RdRp localized on the cytosolic face of DMVs. (1, 2) 17Cl-1 cells expressing APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12 were infected with MHV-A59, fixed, and stained with DAB/H2O2, the DAB polymer generated by APEX2 pinpointing the positions of APEX2-tagged RdRp. (1) Low-magnification transmission electron micrograph. (2) Boxed area in A at higher magnification. Asterisks: DMVs. Arrowheads: DAB polymer (positions of RdRp). mt: mitochondrion. (3 and 4) WT 17Cl-1 cells devoid of APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12 were treated in the same way as in A and B. (3) Low-magnification transmission electron micrograph. (4) Boxed area in C at higher magnification. No DAB polymer was visible. (5, 6) 17Cl-1 cells expressing APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12, mock-infected, fixed, and stained in the same way as in 1 and 2. (5) Low-magnification transmission electron micrograph. (6) Boxed area in 5 at higher magnification. Neither DMV nor APEX2-tagged RdRp recruited to the periphery of DMV was visible. (7–8) 17Cl-1 cells expressing APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12, infected and fixed in the same way as in A and B, but without DAB/H2O2 staining. (7) Low-magnification transmission electron micrograph. (8) Boxed area in G at higher magnification. No DAB polymer is visible. Scale bars: 2 μm for 1, 3, 5, and 7; 200 nm for 2, 4, 6, and 8. (E) Immuno-EM showing that NSP12 is predominantly localized on the cytosolic membranes of DMVs. Upper panel: Negative control for immunogold labeling, where the NSP12 primary antibody was not applied. Lower panel: In immunogold-labeled samples, gold particles (black dots) indicating the position of NSP12 molecules.

We went on to define the localization of RTC components on DMV using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The 17Cl-1 cells stably expressing APEX2-tagged MHV-A59 NSP12 were treated with MHV-A59, which serves as a useful and safe surrogate model for SARS-CoV-2 infections. APEX2 is an ascorbate peroxidase, which mediates the catalysis of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) into an insoluble polymer that can be readily observed by TEM (Martell et al., 2017). Microscopy results showed that exogenously expressed NSP12 co-localized with RTCs following MHV-A59 infection (Fig. 4 C), indicating that the trans-complementation of MHV-A59 replication complexes is possible, consistent with previous studies (Brockway et al., 2003). TEM results showed that APEX2-NSP12–catalized DAB polymer deposition was readily detectable at the cytosolic face of the DMVs (Fig. 4 D). Furthermore, we detected the NSP12 localization on DMV in the SARS-CoV-2–infected cells using immuno-EM. The result showed that the gold particles of labeling NSP12 localized in the exterior of DMVs (Fig. 4 E). Taken together, all these results indicate that RTCs localize on the cytosolic face of the DMVs.

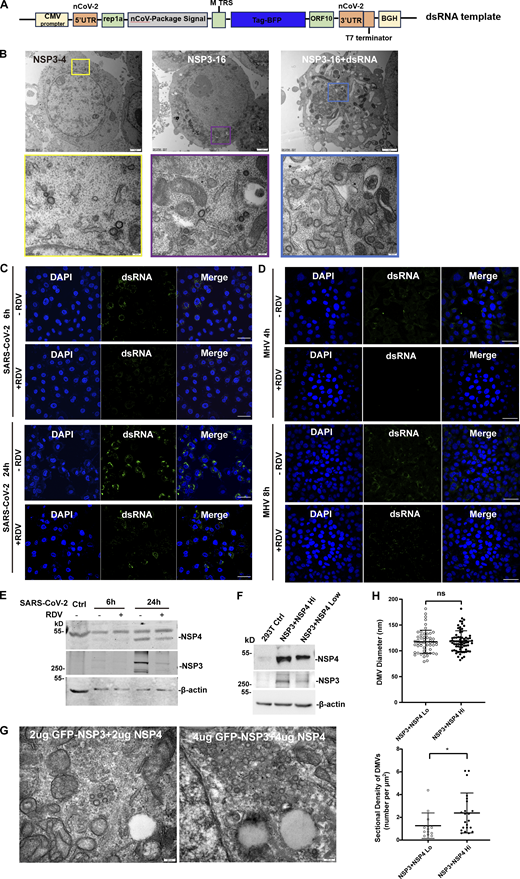

The size of DMVs is influenced by RTC-mediated dsRNA synthesis

Both our results and previous studies showed that the size of DMVs induced by NSP3/4 (∼100 nm) is smaller than those observed during virus infection (∼300 nm). To investigate whether other NSPs contribute to DMV formation, HEK-293T cells stably co-expressing NSP3/4 with other NSPs were constructed, which were confirmed by IB with specific antibodies (Fig. 5 A). NSP1 and NSP2 were excluded from further analysis as it has been established that they are not involved in DMV formation (Ricardo-Lax et al., 2021; Wolff et al., 2020). TEM analysis with quantitative measurements showed that no significant change was observed between the average diameters of DMVs induced by NSP3/4 and NSP3–16 (Fig. S4, A and B; and Fig. 5 B), indicating that other NSPs may not significantly impact DMV size. Previous research indicated that the volumes of spherules are closely correlated with RNA replication template length in Flock house nodavirus (Ertel et al., 2017), which promoted us to hypothesize that RTC-mediated synthesis of dsRNA cargo plays a crucial role in determining DMV size. To verify this hypothesis, a genome template containing SARS-CoV-2 5-UTR and 3-UTR region was transfected into the NSP3–16 expression cells (Fig. S4 A). The results showed that the DMV size in the expressing of NSP3–16 with genome template was slightly but significantly larger than without genome template (Fig. S4 B and Fig. 5 B), suggesting that RTC-mediated synthesis of dsRNA cargo may be involved in determining the size of DMVs. Next, we examined the size of DMVs in SARS-CoV-2–infected cells at 6 and 24 h postinfection (hpi), representing early and late replication stages, respectively. Microscope and TEM results showed a significant increase in dsRNA signal and DMV density at 24 hpi compared with 6 hpi (Fig. S4 C). Consistently, the DMV size at 24 hpi was also larger than at 6 hpi (Fig. 5, C and D), indicating a correlation between viral replication and DMV size. Subsequently, we investigated the effect of the RTC inhibitor remdesivir (RDV) on the DMV size. Treatment with RDV resulted in a significant decrease in dsRNA signal and DMV intensity at both 6 and 24 hpi (Fig. S4 C; and Fig. 5, C and D),indicating that RDV can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication. Furthermore, TEM analysis revealed a striking reduction in DMV size at both 6 and 24 hpi after RDV treatment (Fig. 5, C and D), indicating that inhibition of viral replication can reduce DMV size. Consistently, the similar results were obtained in MHV-A59–infected 17Cl-1 cells at 4 and 8 hpi treatment with or without RDV (Fig. S4 D; and Fig. 5, E and F). All these results indicate that RTC-mediated synthesis of dsRNA cargo plays a role in determining the size of DMVs. However, RDV treatment would reduce the expression level of NSP3/4 in the SARS-CoV-2–infected cells (Fig. S4 E). To rule out the possibility that the reduced expression level of NSP3/4 affects the DMV size, we compared the effect of different expression level of NSP3/4 on the DMV size and number. The results showed that the expression level of NSP3/4 only affects the DMV numbers but not the DMV size (Fig. S4, F–H). All these results indicate that the NSP3/4 expression level is critical for determining the density of DMVs, while dsRNA cargo is involved in the regulation of the size of DMVs.

DsRNA rather than other NSPs is critical for determining the DMV size. (A) IB analysis of the NSP12, NSP5, and NSP15 expression in HEK-293T cells stably expressing SARS-CoV-2 NSP3-16, where NSP5-11 and NSP13-16 were polyproteins. (B) Quantification of the size of DMVs is shown as mean ± SEM. n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 111, 339, and 401 for NSP3/4, NSP3-16, NSP3-16+dsRNA, respectively. Student’s two-tailed t test, ***: P < 0.001. ****: P < 0.0001. ns: not significant. (C) TEM analysis of the DMVs induced by SARS-CoV-2 at 6 or 24 hpi with or without RDV treatment. Each boxed area in a low-magnification TEM micrograph (left) is depicted in detail in a high-magnification one (right). Scale bars: 2 μm for low-magnification TEM micrographs, 200 nm for high-magnification TEM micrographs. (D) Quantification of the size of DMVs is shown as mean ± SEM (left). n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 129, 128, 255, and 47 for control 6 hpi, RDV 6 hpi, control 24 hpi, and RDV 24 hpi, respectively. Quantification of DMV density is shown as mean ± SEM (right). n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 10, 9, 10, and 10 for control 6 hpi, RDV 6 hpi, control 24 hpi, and RDV 24 hpi, respectively. Student’s two-tailed t test, **: P < 0.01. ****: P < 0.0001. ns: not significant. (E) TEM analysis of the DMVs induced by MHV-A59 at 4 or 8 hpi with or without RDV treatment. Each boxed area in a low-magnification TEM micrograph (left) is depicted in detail in a high-magnification one (right). Scale bars: 2 μm for low-magnification TEM micrographs, 200 nm for high-magnification TEM micrographs. (F) Quantification of the size of DMVs is shown as mean ± SEM (left). n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 84, 33, 88, and 56 for control 4 hpi, RDV 4 hpi, control 8 hpi, and RDV 8 hpi, respectively. Quantification of DMV density is shown as mean ± SEM (right). n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 22, 19, 43, and 27 for control 4 hpi, RDV 4 hpi, control 8 hpi, and RDV 8 hpi, respectively. Student’s two-tailed t test, **: P < 0.01. ***: P < 0.001. ****: P < 0.0001. ns: not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

DsRNA rather than other NSPs is critical for determining the DMV size. (A) IB analysis of the NSP12, NSP5, and NSP15 expression in HEK-293T cells stably expressing SARS-CoV-2 NSP3-16, where NSP5-11 and NSP13-16 were polyproteins. (B) Quantification of the size of DMVs is shown as mean ± SEM. n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 111, 339, and 401 for NSP3/4, NSP3-16, NSP3-16+dsRNA, respectively. Student’s two-tailed t test, ***: P < 0.001. ****: P < 0.0001. ns: not significant. (C) TEM analysis of the DMVs induced by SARS-CoV-2 at 6 or 24 hpi with or without RDV treatment. Each boxed area in a low-magnification TEM micrograph (left) is depicted in detail in a high-magnification one (right). Scale bars: 2 μm for low-magnification TEM micrographs, 200 nm for high-magnification TEM micrographs. (D) Quantification of the size of DMVs is shown as mean ± SEM (left). n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 129, 128, 255, and 47 for control 6 hpi, RDV 6 hpi, control 24 hpi, and RDV 24 hpi, respectively. Quantification of DMV density is shown as mean ± SEM (right). n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 10, 9, 10, and 10 for control 6 hpi, RDV 6 hpi, control 24 hpi, and RDV 24 hpi, respectively. Student’s two-tailed t test, **: P < 0.01. ****: P < 0.0001. ns: not significant. (E) TEM analysis of the DMVs induced by MHV-A59 at 4 or 8 hpi with or without RDV treatment. Each boxed area in a low-magnification TEM micrograph (left) is depicted in detail in a high-magnification one (right). Scale bars: 2 μm for low-magnification TEM micrographs, 200 nm for high-magnification TEM micrographs. (F) Quantification of the size of DMVs is shown as mean ± SEM (left). n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 84, 33, 88, and 56 for control 4 hpi, RDV 4 hpi, control 8 hpi, and RDV 8 hpi, respectively. Quantification of DMV density is shown as mean ± SEM (right). n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 22, 19, 43, and 27 for control 4 hpi, RDV 4 hpi, control 8 hpi, and RDV 8 hpi, respectively. Student’s two-tailed t test, **: P < 0.01. ***: P < 0.001. ****: P < 0.0001. ns: not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

TEM analysis of the DMVs in HEK-293T cells, confocal microscopy analysis of dsRNA signal in the SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero-E6 cells and MHV-A59–infected 17Cl-1 cells, and the expression level of NSP3/4 only affects the density but not the size of DMVs, related toFig. 5 . (A) The schematic structure of the SARS-CoV-2 genome template. (B) TEM analysis of the DMVs induced by SARS-CoV-2 NSP3/4 (left), NSP3-16 (middle), and NSP3-16+dsRNA (right) in HEK-293T cells. Each boxed area in a low-magnification TEM micrograph (upper) is depicted in detail in a high-magnification one (bottom). Scale bar, 2 μm for low-magnification TEM micrographs, 200 nm for high-magnification TEM micrographs. (C and D) Confocal microscopy analysis of dsRNA signal in the SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero-E6 cells at 6 or 24 hpi (C) and MHV-A59–infected 17Cl-1 cells at 4 or 8 hpi (D) with or without RDV treatment. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) IB analysis of the NSP3 and NSP4 expression in Vero-E6 cells in SARS-CoV-2 infected at 6 or 24 hpi with or without RDV treatment. n = 3 independent experiments. (F) IB analysis of the NSP3 and NSP4 expression in low-dose (2 μg) and high-dose (4 μg) NSP3/4 transfection. n = 3 independent experiments. (G) TEM analysis of the DMVs induced by low-dose (2 μg, left) and high-dose (4 μg, right) NSP3/4. Scale bar, 200 nm. (H) Quantification of the size of DMVs is shown as mean ± SEM. n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 52 and 72; quantification of DMV density is shown as mean ± SEM. Student’s two-tailed t test, *: P < 0.05. ns: not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

TEM analysis of the DMVs in HEK-293T cells, confocal microscopy analysis of dsRNA signal in the SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero-E6 cells and MHV-A59–infected 17Cl-1 cells, and the expression level of NSP3/4 only affects the density but not the size of DMVs, related toFig. 5 . (A) The schematic structure of the SARS-CoV-2 genome template. (B) TEM analysis of the DMVs induced by SARS-CoV-2 NSP3/4 (left), NSP3-16 (middle), and NSP3-16+dsRNA (right) in HEK-293T cells. Each boxed area in a low-magnification TEM micrograph (upper) is depicted in detail in a high-magnification one (bottom). Scale bar, 2 μm for low-magnification TEM micrographs, 200 nm for high-magnification TEM micrographs. (C and D) Confocal microscopy analysis of dsRNA signal in the SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero-E6 cells at 6 or 24 hpi (C) and MHV-A59–infected 17Cl-1 cells at 4 or 8 hpi (D) with or without RDV treatment. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) IB analysis of the NSP3 and NSP4 expression in Vero-E6 cells in SARS-CoV-2 infected at 6 or 24 hpi with or without RDV treatment. n = 3 independent experiments. (F) IB analysis of the NSP3 and NSP4 expression in low-dose (2 μg) and high-dose (4 μg) NSP3/4 transfection. n = 3 independent experiments. (G) TEM analysis of the DMVs induced by low-dose (2 μg, left) and high-dose (4 μg, right) NSP3/4. Scale bar, 200 nm. (H) Quantification of the size of DMVs is shown as mean ± SEM. n (number of analyzed DMVs) = 52 and 72; quantification of DMV density is shown as mean ± SEM. Student’s two-tailed t test, *: P < 0.05. ns: not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

It has been demonstrated that expression of NSP3/4 in cis could induce the formation of the DMVs (Zimmermann et al., 2023). However, this model is dependent on the cleavage of NSP3/4 by PLpro, which will hamper to investigate the effect of specific domain on the DMV formation, as the deletion of a specific domain will affect the cleavage efficiency. In this study, we found that the expression of NSP3 and NSP4 in trans also could induce the formation of the pore complex on DMVs. Using this model, we systemically analyzed the effect of specific domains in NSP3 and NSP4 on the DMV formation. Interestingly, we found that removal of the entire NTD of NSP3 induces the formation of CM-like structures, indicating that the CM might be the degradation production of NSP3 with NSP4-induced structures in virus-infected cells. Regarding the specific domains in the NTD of NSP3, previous research showed that removal of Ubl1-Mac1 domains does not affect the DMV formation, yet the removal of Ubl1–Ubl2 domains leads to membrane remodeling but impairs the formation of DMVs (Zimmermann et al., 2023). In this study, we found that the removal of NAB-β2M domains also hinders the DMV formation. Combining these results, the specific domains from Mac2 to β2M in the NTD of NSP3 are essential for DMV formation. Additionally, the removal of the CTD or TMD(2–4)-CTD of NSP3 induces the formation of double-membrane whorl-like structures, similar to the uncleaved NSP3/4-induced structures (Zimmermann et al., 2023). The cryo-ET and subtomogram averaging in isolated DMVs hypothesized that cleavage of NSP3/4 by PLpro releases the spatial restraint between the NSP3-CTD and NSP4-ecto, allowing the NSP3-CTD to oligomerize, meanwhile, the interaction of TMDs and cis interaction of NSP3/4 ectodomains on the same membrane lead to the formation of the highly locally curved membrane for the pore to assembly (Huang et al., 2024). In this study, we provide evidence to support that the NSP3-CTD oligomerization plays a critical role in the formation of highly locally curved membrane. Additionally, the cryo-ET and subtomogram averaging in isolated DMVs indicated that the NSP4-CTD forms trimer of dimer to generate the bottom pore of DMVs (Huang et al., 2024). This study suggested that the removal of NSP4-CTD will not affect the DMV formation; however, it will significantly decrease the DMV numbers, suggesting that this domain is merely a component of the DMV pore complex and is not involved in the regulation of the DMV formation.

In addition, it has been found that some host factors are involved in the formation of coronavirus DMVs. For instance, the ER scramblase TMEM41B and VMP1 (Ji et al., 2022), the ER morphogenic proteins reticulon-3 (RTN3) and RTN4 (Williams et al., 2023), as well as the ER acylglycerolphosphate acyltransferase 1 (AGPAT1) and AGPAT2 (Tabata et al., 2021) are recruited to and are crucial for the formation of DMV formation. Moreover, the autophagy machinery factors, including the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and the PI3P-binding protein DFCP1 but not the autophagy ATG5-12/16L1 complex, are found to be essential for DMV formation and SARS-CoV-2 replication (Twu et al., 2021). However, how these host factors interact with the specific domains within NSP3 and NSP4 to regulate the formation of DMVs needs to be further explored.

While NSP3/4-induced DMVs share a similar morphology to virus-induced DMVs, the size of the former is smaller. We investigated the potential involvement of other NSPs in DMV formation by sequentially adding them to the NSP3/4 system. However, the addition of other NSPs did not result in a change in DMV size, suggesting that they do not play a significant role in determining DMV size. Previous studies have shown that the spherular replication complex vesicle sizes are strongly correlated with RNA template length in Flock House nodavirus and Semliki Forest alphavirus (Ertel et al., 2017; Kallio et al., 2013), indicating that the dsRNA cargo length is correlated with vesicle size. In the case of NSP3/4-induced DMVs or NSP3–16–induced DMVs, no dsRNA cargoes were detected within the DMV interior. This led us to speculate that the presence of dsRNA cargo is critical for determining DMV size. Supporting this hypothesis, we observed a correlation between viral replication and DMV size, where inhibiting virus replication significantly reduced the size of DMVs. Therefore, we conclude that the RTC-mediated synthesis of dsRNA cargo is crucial for determining the size of DMVs, rather than other viral NSPs.

Numerous evidences show that RTCs localize to DMV (Brockway et al., 2003; Knoops et al., 2008; V’Kovski et al., 2019; van Hemert et al., 2008). However, the exact topology of the RTCs with respect to DMV membrane is controversial. One study reported that the RTCs were enclosed by membranes, as several RTC subunits NSP5 and NSP8 were protease resistant and became susceptible to degradation upon addition of a nonionic detergent (van Hemert et al., 2008). In addition, cryo-ET studies have also indicated a higher density region on the luminal side of DMVs, potentially representing the viral replication machinery (Wolff et al., 2020). However, the immuno-EM indicated that numbers of gold particles of labeling NSP3, NSP5, and NSP8 were found on DMV membranes, but the interior of DMVs was essentially devoid of label (Knoops et al., 2008). In addition, immuno-EM and APEX2-based EM studies indicated the RTC subunit NSP2 localizes on the cytosolic face of the DMVs in SARS and MHV-infected cells (Hagemeijer et al., 2010; Ulasli et al., 2010; V’Kovski et al., 2019). In this study, our FPP, APEX2-based EM and immuno-EM results support the finding that the RTC core subunit NSP12 also localizes on the cytosolic face of DMVs. Therefore, we conclude that RTCs are localized on the cytosolic face of DMVs. We speculate that RTCs are resistant to protease digestion may be due to ultracentrifugation causing it to be surrounded by membranes. Also, the higher density in the interior of DMVs may consist of the host factors. So how do the RTCs assemble in the outer membrane of DMVs? It has been reported that the enterovirus recruits RdRp from the cytosolic pool to the replicative structures via phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P) lipid catalyze by the phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase IIIb (PI4KIIIb) (Hsu et al., 2010). In the case of coronaviruses, NSP3, which contains a long cytosolic domain, is a central component of the DMV pore complex and may function as a scaffold protein (Hsu et al., 2010). Our study reveals that the RTC core component NSP12 directly interacts with NSP3 through its cytosolic N terminus. This interaction allows the recruitment of other RTC components to the exterior of DMVs induced by NSP3/4.

In summary, this study provides insights into the formation of coronavirus DMVs and ROs. The NTD and CTD of NSP3, but not the CTD of NSP4 are critical for the formation of DMVs. However, the homodimerization of NSP4 CTD is involved in the regulation of the DMV numbers. Additionally, the core RTC component NSP12, along with other RTC subunits, is recruited to the exterior of DMVs through the NSP3–NSP12 axis, forming the ROs. Additionally, we demonstrate that the RTC-mediated synthesis of dsRNA cargo is critical for determining DMV size. However, further research is needed to fully elucidate the molecular components and functions of the DMV pore complex and the exact mechanism of RTC assembly within DMVs.

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

HeLa, HEK-293T (from ATCC), and 17Cl-1 (provided by Professor Hongyu Deng, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China) cells were cultured in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% FBS (Biological Industries) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. 17Cl-1 cells were used to propagate MHV-A59 (provided by Professor Hongyu Deng, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China), at an MOI of 0.05. The 17Cl-1 cells were inoculated into a 3.5-cm dish and infected with MHV-A59 for 1 h. Then, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS. Plaque-forming units were measured after incubation with serially diluted supernatants of cell culture for 36 h. SARS-CoV-2 was propagated and prepared in African green monkey kidney Vero-E6 cells (provided by Professor Xiancai Ma, Guangzhou National Laboratory, Guangzhou, China). SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-BA.5 (provided by Professor Yongxia Shi, State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, Health Quarantine Institute of IQTC, Guangzhou Customs District, Guangzhou, China) infection was performed at an MOI of 0.5 in a biosafety level 3 facility. The infection was conducted in Guangzhou Customs District Technology Center BSL-3 Laboratory. The obtained virus was stored at −80°C until further use.

Plasmids

GFP-NSP3, Flag-NSP3, NSP4-GFP, and NSP4-mCherry were kindly provided by Prof. Hong Zhang (Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China) (Ji et al., 2022). tagBFP-NSP3 and NSP4-tagBFP were generated by replacing the GFP fragment of GFP-NSP3 and NSP4-GFP with tagBFP. The coding sequences of other SARS-CoV-2 NSPs were amplified using PCR from SARS-CoV-2 replicon (kindly provided by Prof. Hui Zhang, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University) and inserted into a pLVX-EF-1α-puro vector (purchased from MIAO LING BIOLOGY, DB00101). pEGX-6P-GST vector used in this study is preserved in our laboratory. NSP13–16 was constructed by inserting into pLVX-EF-1α-puro vector and P2A was added between the C terminus of NSP13 and NSP15 to promote the polyprotein to self-cleave. GFP-NSP3 (1–1495), GFP-NSP3 (1–1546), GFP-NSP3 (1391–1945), GFP-NSP3 (ΔPlnc), GFP-NSP3 (ΔMAC1), GFP-NSP3 (ΔSUD), GFP-NSP3 (ΔPLP2); NSP4 (ΔCTD); and NSP12-mCherry (1–551), NSP12-mCherry (1–373), NSP12-mCherry (1–250), NSP12-mCherry (551–932), NSP12-mCherry (374–932), NSP12-mCherry (Δ51–249), NSP12-mCherry (Δ250–364) were generated by PCR-based mutagenesis from GFP-NSP3, NSP4-mCherry, and NSP12-mCherry, respectively. NSP3-NTD (1–1391) was cloned into pEGX-6P-GST vector (purchased from MIAO LING BIOLOGY). The dsRNA template was constructed by replacing the GFP and luciferase fragment of ps2V from Hui Zhang (Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China) (Luo et al., 2021). The sequences of MHV-A59 NSP12 were amplified using PCR from MHV-A59 cDNA and inserted into pLVX-EF-1α-puro vector. The primers used for constructing the plasmids are provided in the Table S1.

Cell lines

Lentivirus was generated by transfecting HEK-293T cells with the lentiviral plasmid pLVX-EF-1α encoding the target protein together with the psPAX2 (#12260; Addgene) and VSVG (#8454; Addgene) plasmids in a ratio 4:3:1. The supernatant containing the lentivirus was collected in 48 and 72 h after transfection, filtered with a 0.45-μm filter, and used for transduction of HeLa cells, followed by selection with puromycin, blasticidin, and hygromycin or flow cytometry. The lentivirus was enriched by concentration tube (UFC910096; Millipore) and the infected HEK-293T cells with the proportion at a 1:1.

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies were used in this study as follows: mouse anti-Flag (66008-4-Ig; Proteintech group), mouse anti-HA (AB1105; Coolaber), rabbit-anti-mCherry (26765-1-AP; Proteintech group), mouse anti-dsRNA (J2, 10010200; Scicons), rabbit anti-NSP5 (29286-1-AP; Proteintech), rabbit-anti-NSP12 (29264-1-AP; Proteintech), rabbit-anti-NSP15 (GTX636917; GeneTex), and mouse-anti-β-actin (RM2001; Beijing Ray Antibody Biotech); HRP-conjugated Affinipure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (SA00001-1; Proteintech group) and Nanogold-Fab’ Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (#2004; Nanoprobes); Anti-Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (A-11029; Invitrogen) and Anti-Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 647 (A-32728; Invitrogen); Dylight 680(A23710), Goat Anti-Mouse IgG and Dylight 800(A23910), and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG were purchased from Abbkine. Digitonin (HY-N4000) and remdesivir (GS-5734) were purchased from MedChemExpress. Hochest (23491-45-4) and glutaraldehyde (111-30-8) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Tween-20 (ST825-100 ml), 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (P0099-100 ml), Triton X-100 (P0096-500 ml), and Protein A+G Sepharose Beads (P2012) were purchased from Beyotime. Polyethylenimine (764582; Sigma-Aldrich) and Lipofectamine 3000 (L3000001; Invitrogen) were used for transfection.

Co-IP and IB

HEK-293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids for 24–48 h were harvested with lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% NP-40, 40 mm β-glycerophosphate, 5 mm EDTA, and 1x protease inhibitor mixture) (Roche Applied Science) for 30 min on ice and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were incubated with protein A/G agarose beads coated with an anti-GFP or anti-mCherry antibody overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed four times with lysis buffer and then boiled with the 4× loading buffer for 10 min. The immunoprecipitants were applied to standard IB analyses with indicated specific antibodies.

For IB, samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBST (1× PBS with 0.05% Tween 20) buffer at room temperature for 1 h. Following this, they were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Afterward, the membranes were treated with secondary antibodies (IRDye 680/800; LI-COR Biosciences) at room temperature in the dark for 2 h. Images were visualized and captured using the Odyssey M system (LI-COR Biosciences). The images were analyzed with ImageJ.

Protein purification and in vitro pull-down assay

For recombinant NSP3-NTD (1–1391) protein, the cDNA of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3-NTD (1–1391) was cloned into pEGX-6P-GST vector with C-terminal GST and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) with 0.4 mM IPTG at 16°C for 16 h. Bacteria were collected and lysed by sonication in PBS buffer containing 400 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and protease inhibitors on ice. Supernatants were collected after centrifugation at 12,000 g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant was incubated with Ni-NTA agarose beads (SA004005; Smart-Lifesciences) for 2 h at 4°C. The GST-tagged NSP3-NTD (1–1391) was eluted by elution buffer (PBS containing 400 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole). The proteins GST-Flag (cat. no. Ag2329) and NSP12-FLAG (cat. no. 81354) were purchased from Proteintech Group, lnc. and Active Motif, respectively.

For in vitro pull-down assay, anti-FLAG agarose beads (SM009001; Smart-Lifesciences) were co-incubated with GST-Flag and NSP12-Flag protein; Glutathione Sepharose (cat. no. 17075605) was co-incubated with GST-Flag or NSP12-Flag protein. The beads were incubated overnight at 4°C and washed three times with lysis buffer (1 × PBS buffer, contain 400 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton) to remove nonspecifically binding protein. The samples were then subjected to IB analysis.

FPP

FPP was carried out as described previously (Ji et al., 2022). Briefly, HeLa cells cultured on glass-bottom dishes were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h. After washing three times with KHM buffer (100 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM Hepes, 2 mM MgCl2, and pH 7.4), the live cells were treated with 100 μM digitonin for 2 min at room temperature. Then 50 μg/ml pK was added to the cells and live-cell images were captured using NIS viewer in time phase by confocal microscope Nikon A1 with a 63×/1.40 oil-immersion objective lens (Plan-Apochromatlan, Nikon) and a camera (A1-DUG-2, Nikon) at room temperature.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells cultured on glass-bottom dishes were fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min. Then the cells were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, blocked with 5% BSA, and incubated with diluted primary antibody in PBS for overnight at 4°C temperature. After washing with PBS three times, cells were incubated with appropriate Alexa Fluor 488-, 568-, or 647-conjugated secondary antibodies in PBS for 60 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with Hochest at room temperature for 30 min and imaged using NIS Elements imaging software under confocal microscope Nikon A1 with a 63×/1.40 oil-immersion objective lens (Plan-Apochromatlan; Nikon) and a camera (A1-DUG-2; Nikon) at room temperature.

APEX2-based TEM

17Cl-1 cells stably expressing MHV-A59 NSP12-HA-APEX2 were grown on the surface of an ACLAR film. After infection with MHV-A59 at MOI >5 for 8 h, the cells were rinsed with PBS, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (cat. no. 16200; Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS for 1 h, and then rinsed with PBS for three times. The fixed cells were treated with 1.5 mg/ml glycine in PBS for 5 min to inactivate residual aldehyde and then rinsed with PBS for three times. The cells were submerged in 0.5 mg/ml DAB (cat. no. D12384; Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS and kept in the dark for 40 min and then the aqueous H2O2 was added at 10 μmol/ml for another 15 min. The cells were rinsed twice with PBS, twice with double-distilled water (ddH2O) and then stained with 1% osmium tetroxide and 0.8% potassium ferricyanide in ddH2O for 1.5 h. After being rinsed three times with ddH2O, the sample underwent a dehydration process in which the solution submerging the sample was sequentially replaced by 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% ethanol solutions, each solution submerging the sample for 6 min. The sample was then infiltrated sequentially with 100% acetone for 6 min, 100% acetone for 6 min again, 3:1 acetone/EMbed 812 resin (cat. no. 14120; Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 1 h, 1:1 acetone/EMbed 812 resin for 3 h, 1:3 acetone/EMbed 812 resin for 4 h, 100% EMbed 812 resin for 12 h, 100% EMbed 812 resin for 12 h again, and 100% EMbed 812 resin for 12 h the third time. The sample was embedded in EMbed 812 resin and underwent solidification at 60°C for 72 h. Sectioning was performed with a Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome. The sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 15 min and 1% lead citrate for 5 min. Electron micrographs were acquired with an FEI Tecnai Spirit 120 kV transmission electron microscope operating at 100 kV accelerating voltage, equipped with a CCD camera (MoradaG3; EMSIS) and RADIUS software. Three controls were set to monitor the authenticity of the positive APEX2-DAB staining: (1) WT 17Cl-1 cells instead of cells expressing MHV-A59 NSP12-HA-APEX2, (2) mock infection with cell culture medium instead of the virus, and (3) mock staining with PBS instead of DAB/H2O2 staining solution.

Conventional TEM

17Cl-1 cells incubated with MHV-A59 at MOI >5 for 4 or 8 h after 1 h of 10 μm RDV treatment or nontreatment and HEK-293T cells expressing SARS-CoV-2 NSPs were harvested with trypsin and centrifuged to form cell pellets. The cell pellets were rinsed with PBS and then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (cat. no. 16200; Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS at 4°C overnight. The fixed cell pellets were rinsed twice with PBS, twice with ddH2O, and underwent subsequent steps, including pre-staining, dehydration, resin infiltration, embedding, solidification, sectioning, and post-staining as described in section APEX2-based TEM above. Electron micrographs were acquired with an FEI Tecnai Spirit 120-kV transmission electron microscope operating at 100 kV accelerating voltage, equipped with a CCD camera (MoradaG3; EMSIS) and RADIUS software. Sectional diameters of DMVs were measured with ImageJ. Sectional densities of DMVs were calculated by the number of DMVs in a cell section over the area of the cytoplasm.

Immuno-EM

Vero-E6 cells were cultured on ACLAR films and infected with SARS-CoV-2. At 24 hpi, the cells were washed with PBS and chemically fixed using 4% PFA and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 1 h. The fixed cells were then washed three times with PBS for 5 min each. The samples were subsequently treated with a blocking/permeabilization buffer (10% goat serum and 0.1% saponin in PBS) for 1 h. After three washes with 5% goat serum in PBS for 3 min each, the samples were treated with either (1) a dilution buffer (5% goat serum in PBS) or (2) the primary antibody (NSP12 antibody, 1:100 dilution in the dilution buffer) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The samples were then washed three times with 1% goat serum in PBS for 5 min each, before being incubated with the Nanogold secondary antibody (#2004; Nanoprobes, 1:50 dilution in the dilution buffer) for 1 h. Following this, the samples were washed three times with PBS and further fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 1 h. Any residual aldehyde was removed by three washes with 50 mM glycine in PBS for 5 min each. The samples were then washed three times with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 5 min each and rinsed three times with ddH2O for 5 min each. Nanogold particles were enlarged using the Nanoprobes GoldEnhance EM Plus solutions according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were rinsed three times with ddH2O for 5 min each before undergoing the standard TEM sample preparation protocol as described in the preceding section.

Cell culture, transfection, and vitrification

Quantifoil R2/1 gold EM grids or finder grids (200 mesh with holey carbon film of 2-μm hole size and 1 μm spacing) were plasma cleaned with O2 and H2 for 30 s in a glow discharge device (Gatan, Plasma Cleaner) and sterilized with UV light for 20 min in a biosafety cabinet. HeLa cells were seeded on EM grids in a 35-mm dish at a density of 100 K cells per dish and incubated at 37°C overnight. Cells were transfected with plasmids (GFP-NSP3 and NSP4-mCherry) using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (L3000001; Thermo Fisher Scientific). 24 h after transfection, samples were plunge-frozen in liquid nitrogen by using an EM GP2 Automatic Plunge Freezer (Leica). Grids were blotted from a single side (opposite to cell side) with 6-s blotting, chamber conditions of 25°C and 85% humidity, and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Cryo-ET

Plunge-frozen samples were transferred to a cryo-CLIEM system that integrates a 3D multicolor confocal microscope into a dual-beam–focused ion beam scanning electron microscope (FIB-SEM) (Li et al., 2023). Before FIB milling, 3D LM imaging was performed using an integrated confocal microscope and custom-made software. The acquired image was titled to the same direction as the FIB milling, and milling size was determined according to the fluorescent signal (Fig. S1). A 500-pA current was used for rough milling and a lower current at 50 pA for the polishing step to produce the final lamella at 150-nm thickness. A total of six cryo-lamellas were prepared, 50% of which contained the DMVs, and the quality of lamellas was good enough to collect tilt-series. The lamellas were imaged on a 300-kV Titan Krios electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a field mission gun, a direct electron detector (Gatan, K2 camera) and an energy filter (Gatan). Tilt-series were collected from −42° to 60° at 3° increments using SerialEM (Mastronarde, 2005) software in counting mode, with total accumulated dose of 100 e−/Å2, defocus of −8 μm, the energy filter of 20 eV, and the final pixel size of 4.29 or 2.22 Å. Dose-fractioned images were aligned by MotionCor2 (Zheng et al., 2017). The corrected tilt-series were aligned with AreTomo (Zheng et al., 2022) and reconstructed by WBP implemented in the IMOD software package (Kremer et al., 1996). CTF estimation was performed with Warp (Tegunov and Cramer, 2019). Tomograms were 4× binned and used for visualization and segmentation. 3D rendering of cellular features were segmented by EMAN2.2 (Chen et al., 2017), including ER, mitochondria, microtubules, actin filaments, ribosomes, and DMVs. UCSF Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004) was used to filter, smooth, and display the segmentation map.

Subtomogram averaging

Tomograms were reconstructed using Warp software with a binning level of 8 followed by deconvolution to enhance visualization. The identification and selection of DMV membrane pore complex was done manually using Dynamo packages (Castaño-Díez et al., 2012). Initial Euler angles for two out of three directions were determined based on the vector between a manually selected point in the membrane pore complex transmembrane region and another at the center of the DMV. Next, we extracted 111 subvolumes using Warp with dimensions of 32 × 32 × 32 voxels at 24 Å per voxel. To avoid any model bias, an average reconstruction of all particles was generated as an initial alignment reference within RELION (Bharat and Scheres, 2016), where C6 symmetry was always enforced. The 3D classification was applied with restrictions on the search range for rotation and tilt angles, and then 50 particles with highest quality was chosen for auto-refinement.

Statistical analysis

Co-IP, IB, and immunofluorescence results were representatives of at least three independent experiments. The image processing and analysis was performed by ImageJ software. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software) and significance was analyzed using Student’s two-tailed t test.

Online supplemental material

This manuscript contains four supplemental figures, one supplemental video, and one supplemental table. Fig. S1 shows workflow of cryo-CLIEM of NSP3/NSP4-induced DMVs, confocal analysis of the co-localization of different truncations of NSP3/NSP4 in HeLa cells, and TEM images of DMV in HEK-293T cells, related to Fig. 1. Fig. S2 shows other NSPs are not recruited to the NSP3/4-induced DMVs, related to Fig. 2. Fig. S3 shows other NSPs are recruited by the NSP3/4-induced DMVs through NSP12, related to Fig. 2. Fig. S4 shows TEM analysis of the DMVs in HEK-293T cells, confocal microscopy analysis of dsRNA signal in the SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero-E6 cells and MHV-A59–infected 17Cl-1 cells, and the expression level of NSP3/4 only affects the density but not the size of DMVs, related to Fig. 5. Video 1 shows cryo-ET of EGFP-NSP3/NSP4-mcherry–induced DMVs in HeLa cells; scale bar, 200 nm, related to Fig. 1. Table S1 shows the primers used for constructing the plasmids.

Data availability

The data and materials used in this study are available from a corresponding author (Z. Li) upon request.

Acknowledgments

The cryo/conventional-EM studies were performed at the Center for Biological Imaging, Institute of Biophysics, and Chinese Academy of Sciences. We thank the staff of the Institute of Biophysics Core Facilities; Shuoguo Li and Xiaojun Huang for the support in cryo-ET data collection; Xixia Li, Xueke Tan, Zhongshuang Lv, and Can Peng for the conventional EM sample preparation; Li Wang for the assistance in immuno-EM; and Junying Jia for the support in the flow cytometry.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92469107 to Z. Li, 92354301 and 32222022 to Y. Jiu), R&D Program of Guangzhou Laboratory (ZL-SRPG22-002 to Z. Li), Guangdong Province High-level Talent Youth Project (2021QN02Y939 to Z. Li), National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFA1307400 to Y. Xue), and STI2030-Major Projects (2022ZD0211900 to Y. Xue).

Author contributions: J. Yang: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft, review, and editing. B. Tian: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, and writing—review and editing. P. Wang: investigation and visualization. R. Chen: formal analysis, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft. K. Xiao: data curation, investigation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. X. Long: formal analysis and methodology. X. Zheng: investigation. Y. Zhu: data curation, software, and visualization. F. Sun: supervision. Y. Shi: data curation, resources, and validation. Y. Jiu: visualization and writing—review and editing. W. Ji: supervision and writing—original draft, review, and editing. Y. Xue: conceptualization, project administration, and supervision. T. Xu: supervision and writing—review and editing. Z. Li: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, visualization, and writing—original draft, review and editing.

References

Author notes

J. Yang, B. Tian, P. Wang, and R. Chen contributed equally to this paper.

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests exist.