The type I intermediate filament proteins keratin 14 (K14) and keratin 15 (K15) are common to all complex epithelia. K14 is highly expressed by progenitor keratinocytes, in which it provides essential mechanical integrity and gates keratinocyte entry into differentiation by sequestering YAP1, a transcriptional effector of Hippo signaling, to the cytoplasm. K15 has long been used as a marker of hair bulge stem cells, though its specific role in skin epithelia is unknown. Here, we show that the lack of two biochemical determinants, a cysteine residue within the stutter motif of the central rod domain and a 14-3-3 binding site in the N-terminal head domain, renders K15 unable to effectively sequester YAP1 in the cytoplasm like K14 does. We combine insight obtained from cell culture and transgenic mouse models with computational analyses of transcriptomics data and propose a model in which a higher K15:K14 ratio promotes a progenitor state and antagonizes differentiation in keratinocytes of the epidermis.

Introduction

Complex epithelia function as physical, chemical, and immunological barriers in many organs and tissues across the body, including the skin, eye, oral mucosa, and reproductive tract. The barrier function of these epithelia is maintained throughout life by carefully balancing the growth, via proliferation, and loss, via differentiation, of keratinocytes, the predominant cell type within complex epithelia, through the process of epithelial homeostasis (Blanpain and Fuchs, 2009; Wells and Watt, 2018).

Keratinocytes can be characterized by their denominal keratin intermediate filament (IF) proteins. Owing to their diversity (N = 54 in humans), differentiation-dependent regulation, unique mechanical properties, and posttranslational modifications, keratin IF proteins play important roles in specific aspects of keratinocyte biology in addition to maintenance of epithelial integrity (Cohen et al., 2022; Fuchs, 1995; Schweizer et al., 2006). The transcriptional and posttranslational regulation of keratin genes and proteins, and their impact on the complex process of epithelial homeostasis are under active investigation (Li et al., 2023). In order to sustain the long-term regeneration of complex epithelia, epithelial homeostasis requires stem-like progenitor keratinocytes that maintain mitotic competency over decades of life (Blanpain and Fuchs, 2009; Wells and Watt, 2018). Here, we provide evidence for a mechanism that prevents the differentiation-related premature loss of progenitor keratinocytes through the regulation of the mechanosensitive transcriptional co-activator YAP1 by keratin IF proteins.

Common to all complex, stratified (e.g., epidermis), and pseudostratified epithelia (e.g., trachea) is the expression of the type I keratins 14 and 15 (K14, K15) and their type II copolymerization partner K5 (Fuchs, 1995; Schweizer et al., 2006). K5 and K14 mRNA and proteins are prominently co-expressed in all keratinocytes residing in the basal layer of stratified epithelia (Cohen et al., 2022). K5/K14 IFs comprise the majority of the mechanical resilience of these cells, protecting them against shear- and trauma-induced lysis (Coulombe et al., 2009; Ramms et al., 2013). In support of the latter, small, dominantly acting missense variants affecting the polymerization and mechanical properties of either K5 or K14 are causative for epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS), a rare genetic skin disorder in which basal layer keratinocytes are fragile and shear or lyse in response to trauma (Bonifas et al., 1991; Coulombe et al., 1991; Coulombe et al., 2009). In striking contrast, very little is known about K15, other than the intriguing attribute that it is correlated, cell-autonomously, with stemness in the skin (Bose et al., 2013; Lyle et al., 1998) and other stratified epithelia (Giroux et al., 2017).

In addition to its well-defined structural function, a novel role of K14 recently came to the fore through the characterization of mice carrying a Krt14 C373A mutant allele (Guo et al., 2020). Krt14 C373A mutant mice were generated to study the physiological significance of a disulfide bond discovered in a crystal structure of the interacting 2B coiled-coil rod domains of human K5 and K14 (Lee et al., 2012). This homotypic transdimer disulfide linkage was shown to involve cysteine (C) 367, located in the 2B domain of human K14 (Lee et al., 2012) (note: C367 in human K14 corresponds to C373 in mouse K14). What distinguishes C367 in human and C373 in mouse K14 from other cysteines is its location in the second residue of the so-called stutter motif, a four-residue disruption of the long-range heptad repeats that are nearly perfectly conserved across the entire superfamily of IF proteins (Lee et al., 2012). Intriguingly, cysteine residues occur in the second position of the stutter in several type I keratins expressed in surface epithelia, including the differentiation-specific K9 and K10 (Lee et al., 2012) and the stress-induced K16 and K17 (Guo et al., 2020). A subsequent study reporting on the atomic structure of the interacting 2B domains of K10 and its partner K1 also uncovered a homotypic disulfide linkage mediated by the K10 stutter cysteine (Bunick and Milstone, 2017).

Live imaging studies of skin keratinocytes in primary culture revealed that the K14 stutter cysteine is required for the establishment of a stable perinuclear filament network (Feng and Coulombe, 2015b), a trademark feature in early-stage differentiating keratinocytes of surface epithelia (Coulombe et al., 1989; Lee et al., 2012). A Krt14 knock-in mutant C373A mouse was generated to test the physiological role of C373-dependent disulfide bonding. Loss of K14 C373 in these mutant mice caused a delay in the initiation of keratinocyte differentiation and aberrant terminal differentiation, ultimately resulting in a barrier defect (Guo et al., 2020). Assessment of K14 cysteine mutant properties in newborn skin keratinocytes in primary culture coupled with a proteomics screen for K14-interacting proteins revealed that unlike its wild-type counterpart, the K14 C373A protein is unable to promote the cytoplasmic retention of YAP1, a co-transcriptional effector of Hippo signaling (Totaro et al., 2018), as epidermal keratinocytes initiate differentiation, both in vivo and in culture (Guo et al., 2020). Alongside YAP1 dysregulation, the scaffolding protein stratifin/14-3-3σ, a known YAP1-interacting protein (Schlegelmilch et al., 2011), occurs in an aggregated rather than the normal diffuse pattern in suprabasal epidermal keratinocytes of Krt14 C373A mice (Guo et al., 2020). These findings guided the development of a model whereby the stutter cysteines in K14 and K10 are required for the cytoplasmic retention of YAP1, in a 14-3-3-dependent manner, thus mediating the initiation (via K14) and sustainment of differentiation (via K10) in epidermal keratinocytes.

Relative to K14, the K15 mRNA and protein are expressed in a subset of keratinocytes in the basal layer (Jonkman et al., 1996; Waseem et al., 1999). Studies that followed up on the discovery of K15’s enrichment in the hair bulge (Lyle et al., 1998) strengthened the correlation involving K15 and epithelial stem cells of the skin (Bose et al., 2013). K15 has since been described as a marker for progenitor cells in several epithelial-rich organs, and its expression has been correlated to the development and severity of cancers in these tissues (Bose et al., 2013). Despite the breadth of work relating K15 to stemness and cancer, a functional role has yet to be assigned to this type I keratin. In human and mice lacking K14 protein, K15 and K5 form fine (“wispy”) filaments in basal keratinocytes that fail to compensate for the essential structural function of K14/K5 filaments (Chan et al., 1994; Jonkman et al., 1996; Lloyd et al., 1995; Rugg et al., 1994). Intriguingly, unlike K14 or K10, K15 does not feature a cysteine at the second position of the stutter motif in its 2B domain.

Here, we combine biochemical, cell biological, histological, computational, and physiological evidence to present evidence that, through its spatially unique distribution and expression levels in epidermis, its lack of a stutter cysteine, and therefore a lesser ability to promote the cytoplasmic sequestration of YAP1, K15 functions as a negative regulator of keratinocyte differentiation and promotes the progenitor cellular state in skin epithelia.

Results

The location of two key biochemical determinants in K14 protein, the “SCRAPS” motif in the N-terminal head domain and a cysteine residue located in the stutter motif of coil 2 in the central α-helical rod domain, and the corresponding sequences in K15 are depicted in Fig. 1 A.

K14 and K15 display distinct staining patterns in vivo and ex vivo. (A) Diagram of K14 and K15 primary structures. Boxes represent coiled-coil regions. Schematic comparing the orthologous residues between K14 and K15 in the putative regulatory regions in the head and 2B rod domains. Mouse K14 contains four cysteines in the head domain and two in the 2B rod domain. Mouse K15 contains one cysteine residue in the head domain and two in the 2B rod domain. * K15 does not have a cysteine orthologous to mK14 C373 (mK15 C373 is downstream of the mK15 stutter region). (B) Individual immunostaining with magnified inset for K14 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human buttock skin. K14 individual immunostaining extends into the suprabasal compartment. A dashed line specifies the basal lamina; epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B′) Individual immunostaining with magnified inset for K15 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human buttock skin. K15 individual immunostaining is restricted to the basal layer. A dashed line specifies the basal lamina; epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) Individual immunostaining for K14 and K15 in skin keratinocytes harvested from neonatal Krt14C373A/WT pups and seeded in primary culture. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C′) Scatter plots representing the K14 and K15 MIVs of individually traced cells in Fig. 1 C (arbitrary units, mean ± SD). (D) Multiplexed immunostaining for K15 (red), K14 (green), and K10 (magenta). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). A dashed line specifies the basal lamina. epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm.

K14 and K15 display distinct staining patterns in vivo and ex vivo. (A) Diagram of K14 and K15 primary structures. Boxes represent coiled-coil regions. Schematic comparing the orthologous residues between K14 and K15 in the putative regulatory regions in the head and 2B rod domains. Mouse K14 contains four cysteines in the head domain and two in the 2B rod domain. Mouse K15 contains one cysteine residue in the head domain and two in the 2B rod domain. * K15 does not have a cysteine orthologous to mK14 C373 (mK15 C373 is downstream of the mK15 stutter region). (B) Individual immunostaining with magnified inset for K14 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human buttock skin. K14 individual immunostaining extends into the suprabasal compartment. A dashed line specifies the basal lamina; epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B′) Individual immunostaining with magnified inset for K15 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human buttock skin. K15 individual immunostaining is restricted to the basal layer. A dashed line specifies the basal lamina; epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) Individual immunostaining for K14 and K15 in skin keratinocytes harvested from neonatal Krt14C373A/WT pups and seeded in primary culture. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C′) Scatter plots representing the K14 and K15 MIVs of individually traced cells in Fig. 1 C (arbitrary units, mean ± SD). (D) Multiplexed immunostaining for K15 (red), K14 (green), and K10 (magenta). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). A dashed line specifies the basal lamina. epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm.

K15 occurs in a spatially defined pool of progenitor keratinocytes in human epidermis

K14 is widely considered, and used, as a marker for “mitotically competent progenitor keratinocytes” in the basal layer of stratified epithelia, including the epidermis. However, several studies have shown that the expression pattern of K14, at both the protein (Fuchs and Green, 1980) and mRNA levels (Stoler et al., 1988), is broader and includes early-stage differentiating keratinocytes in the lower suprabasal layers of epidermis (Cohen et al., 2022). Immunostaining for K14 in human thin (buttock) skin sections corroborates this (Fig. 1 B). K15 displays a distinct immunostaining pattern, in that it is largely excluded from the suprabasal compartment and shows markedly brighter signal in basal keratinocytes located in the bottom of rete ridges (Fig. 1 B′). Analyses of newborn mouse skin keratinocytes in primary culture under calcium-free, growth-promoting conditions show that bright K14 immunostaining occurs in all keratinocytes, whereas K15 is only present in a subset of the cells (Fig. 1 C; quantitation shown in Fig. 1 C′), consistent with observations made in human skin tissue sections. Co-staining for K15, K14, and K10 in thin epidermis shows a strict exclusion between the K15+ basal and K10+ suprabasal compartments and K14+ cells showing a gradation between the two (Fig. 1 D). These findings extend previous studies by several groups (Jonkman et al., 1996; Porter et al., 2000; Waseem et al., 1999; Webb et al., 2004; Whitbread and Powell, 1998; Zhan et al., 2007) and establish that the striking differences in K14 and K15 expression patterns are largely conserved in human and mouse.

Single-cell transcriptomics reveals attributes that uniquely define KRT15-expressing keratinocytes

The availability of single-cell (sc) RNAseq datasets affords an opportunity to gain insight into the significance of keratin gene expression in human skin (Cohen et al., 2022). In healthy abdominal (thin) skin (Fig. S1 A), the majority of keratinocytes can be partitioned into two subsets that exhibit either a KRT14-high or KRT10-high signature, representing progenitor or differentiating status, respectively (Fig. S1, B and C; see Cohen et al., 2022). A third, sizable group of keratinocytes exhibit a hybrid character with appreciable expression of both KRT14 and KRT10 (Fig. S1 D) (Cohen et al., 2022). By comparison, KRT15 expression (Fig. S1 E) occurs only in a subset of KRT14-expressing keratinocytes (Fig. 2 A). These KRT15-expressing cells show minimal overlap with KRT10-expressing cells (Fig. 2 A). Directly relating KRT15 to KRT14 reads across the population of individual keratinocytes in human trunk skin (N = 26,063 cells) (Cohen et al., 2022), in the form of a scatter plot, further highlights that KRT15-expressing keratinocytes are a subset of KRT14-expressing ones (Fig. 2 B). Additionally, we find that the number of KRT15 reads per cell is, overall, significantly lower than that of KRT14 in trunk skin keratinocytes (Fig. 2 C). These findings are consistent with the immunostaining data reported in Fig. 1.

Analysis of human trunk skin using scRNAseq (complement to Fig. 2,). (A) UMAP of scRNAseq data collected from human trunk skin. Clusters consist of 17 keratinocyte clusters and 3 clusters matching non-keratinocyte signature genes (melanocytes, cl. 7 and 18; immune cells, cl. 17). (B and C) Feature map plotting expression levels of (B) KRT14 or (C) KRT10 in the human trunk UMAP. (D) Expression of KRT14 (green) and KRT10 (red) in the human trunk dataset, as described in Fig. 2 C. (E) Feature map of KRT15 expression levels in human trunk dataset presented as UMAP form. (F and G) Expression of the S-phase composite score relative to (F) KRT15 and (G) KRT14 levels across keratinocytes in human trunk epidermis. (H) Expression of G2/M composite score relative to KRT10 levels across keratinocytes in human trunk epidermis.

Analysis of human trunk skin using scRNAseq (complement to Fig. 2,). (A) UMAP of scRNAseq data collected from human trunk skin. Clusters consist of 17 keratinocyte clusters and 3 clusters matching non-keratinocyte signature genes (melanocytes, cl. 7 and 18; immune cells, cl. 17). (B and C) Feature map plotting expression levels of (B) KRT14 or (C) KRT10 in the human trunk UMAP. (D) Expression of KRT14 (green) and KRT10 (red) in the human trunk dataset, as described in Fig. 2 C. (E) Feature map of KRT15 expression levels in human trunk dataset presented as UMAP form. (F and G) Expression of the S-phase composite score relative to (F) KRT15 and (G) KRT14 levels across keratinocytes in human trunk epidermis. (H) Expression of G2/M composite score relative to KRT10 levels across keratinocytes in human trunk epidermis.

Relationships between KRT14, KRT15, and KRT10 in human trunk skin. (A) UMAP of human trunk epidermis highlighting KRT15 levels (green) and KRT14 or KRT10 levels (red) across Seurat clusters. (B) sc expression of KRT15 mapped against KRT14 levels in 26,063 keratinocytes in the human trunk epidermis dataset. (C) Distribution of KRT14 and KRT15 expression across all keratinocytes in the dataset. (D) Distribution of KRT15, KRT14, and KRT10 expression in cells exhibiting increasing levels of basal score signature genes (see Materials and methods for definition of composite scores). (E) Expression of G2/M composite score relative to KRT14 and KRT15 levels across keratinocytes in human trunk epidermis. (F) Analysis of average keratin expression level across 17 Seurat clusters matching keratinocyte signatures in the human trunk epidermis dataset. KRT14 (red, circle), KRT15 (green, square), and KRT10 (blue, triangle) assessed per cluster. Clusters are sorted on the x-axis according to the highest basal score-to-differentiation score ratio. The Seurat cluster showing the highest G2/M composite score, on average, is highlighted. (G) Indirect immunofluorescence with magnified insets of Ki67 and K15 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human buttock skin. K15 channel has been false-colored with the “Fire” lookup table to show signal intensity. Strongly, Ki67-staining nuclei are frequently K15-low basal keratinocytes. Calibration bar displays the color coding for their corresponding K15 MGV intensities. Scale bar, 50 µm. (H) Comparison of linear pairwise expression of type I and type II keratins KRT15/KRT5 (green, R2 = 0.31), KRT14/KRT5 (red, R2 = 0.79), and KRT10/KRT1 (blue, R2 = 0.84) across all keratinocytes in the human trunk epidermis dataset. (H′) Heatmap summarizing Pearson’s (r) correlations between type I and type II keratins across the dataset.

Relationships between KRT14, KRT15, and KRT10 in human trunk skin. (A) UMAP of human trunk epidermis highlighting KRT15 levels (green) and KRT14 or KRT10 levels (red) across Seurat clusters. (B) sc expression of KRT15 mapped against KRT14 levels in 26,063 keratinocytes in the human trunk epidermis dataset. (C) Distribution of KRT14 and KRT15 expression across all keratinocytes in the dataset. (D) Distribution of KRT15, KRT14, and KRT10 expression in cells exhibiting increasing levels of basal score signature genes (see Materials and methods for definition of composite scores). (E) Expression of G2/M composite score relative to KRT14 and KRT15 levels across keratinocytes in human trunk epidermis. (F) Analysis of average keratin expression level across 17 Seurat clusters matching keratinocyte signatures in the human trunk epidermis dataset. KRT14 (red, circle), KRT15 (green, square), and KRT10 (blue, triangle) assessed per cluster. Clusters are sorted on the x-axis according to the highest basal score-to-differentiation score ratio. The Seurat cluster showing the highest G2/M composite score, on average, is highlighted. (G) Indirect immunofluorescence with magnified insets of Ki67 and K15 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human buttock skin. K15 channel has been false-colored with the “Fire” lookup table to show signal intensity. Strongly, Ki67-staining nuclei are frequently K15-low basal keratinocytes. Calibration bar displays the color coding for their corresponding K15 MGV intensities. Scale bar, 50 µm. (H) Comparison of linear pairwise expression of type I and type II keratins KRT15/KRT5 (green, R2 = 0.31), KRT14/KRT5 (red, R2 = 0.79), and KRT10/KRT1 (blue, R2 = 0.84) across all keratinocytes in the human trunk epidermis dataset. (H′) Heatmap summarizing Pearson’s (r) correlations between type I and type II keratins across the dataset.

To probe deeper into the transcriptional signature that reflects the progenitor cellular state, we next performed a supervised analysis of the entire keratinocyte population of thin epidermis according to composite scores (Cohen et al., 2022; Cohen et al., 2024): a “basal score” to identify cells with high transcriptional activity for genes relating to the extracellular matrix (ECM) (and thus likely to reside in the basal compartment), a “differentiation score” to identify cells engaged into differentiation (e.g., cell–cell adhesion components), and “G2/M” and “S” scores to identify cells undergoing mitosis. These scores are formulated independently of any keratin gene (see Materials and methods and Cohen et al., 2022).

First, we sorted individual keratinocytes according to their expression of a given keratin gene as a function of the basal score, with the latter binned into quartiles (percentiles 0–25, 26–50, 51–75, and 76–100). This analysis revealed that KRT15 expression shows a clear bias toward keratinocytes with a high basal score, KRT10 expression shows a clear bias toward keratinocytes with a low basal score, while KRT14 expression shows a mixed identity (Fig. 2 D).

Second, we related keratin expression to the G2/M composite score, which reflects engagement in mitosis, via a scatterplot. This analysis showed that even though they exhibit a high basal score, high KRT15-expressing keratinocytes show very low G2/M scores, unlike high KRT14-expressing cells (Fig. 2 E). The same conclusion is attained when relating KRT15 and KRT14 expression to a composite score for the S phase (Fig. S1, F and G). In contrast, the relationship between KRT10 expression levels and the G2/M score is clearly bimodal (Fig. S1 H), consistent with the recent demonstration of a transitional population of epidermal keratinocytes that have initiated differentiation and yet are mitotically active (Cockburn et al., 2022; Cohen et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2020).

Third, we rank-ordered the Seurat clusters (Fig. S1 A) according to the ratio of their basal and differentiation scores. This analysis revealed a clear sequence whereby KRT15 occurs in cells with a clear basal identity, KRT14 occurs across cells with either a basal or a differentiating identity, and KRT10 expression is clearly polarized to differentiating cells (Fig. 2 F). Interestingly, the Seurat cluster enriched for G2/M keratinocytes maps to cells that feature an intermediate basal-to-differentiation score in the distribution reported in Fig. 2 F.

To further substantiate the exclusion of KRT15-expressing cells from the subpopulation of actively mitotic G2/M cells, we next performed co-immunostaining of human thin (trunk) skin for Ki67, a common nuclear marker for cycling cells, and K15. Consistent with the data reported in Fig. 1, K15 staining intensity is strongest in the bottom of rete ridges. The strongest Ki67 staining nuclei occur in keratinocytes showing low K15 intensity, and, frequently, a delaminating “fan-shaped” morphology (Fig. 2 G) (see Miroshnikova et al., 2018).

Prior analyses of sc transcriptomics datasets established that KRT15 is distinct from KRT14 in the extent of coregulation with a specific type II keratin partner. As reported (Cohen et al., 2022), transcription of KRT14 and KRT5 (R2 = 0.79), and similarly of KRT10 and KRT1 (R2 = 0.84), is tightly correlated over a broad range of expression levels (Fig. 2 H). In contrast, KRT15 shows a markedly weaker correlation to KRT5 (R2 = 0.31; Fig. 2 H) or any other type II keratin gene (data not shown). How the apparent imbalance in type I (KRT14, KRT15) and type II (KRT5) keratin transcripts is resolved at the protein level in progenitor keratinocytes of thin epidermis is an issue of interest but was not addressed in the current study.

Overall, the computational analyses reported here demonstrate that KRT15 is highly expressed by cells with the strongest basal and weakest differentiated identity, while KRT10 is highly expressed by cells with the weakest basal and strongest differentiated identity. Further substantiating the distinct character of KRT15, the top 24 genes showing the highest correlation to KRT15 in human trunk skin (all cells) are highly enriched for components of hemidesmosomes and ECM (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, the top 24 genes most correlated to KRT10 in human trunk skin (all cells) are highly enriched for desmosome components and proteins involved in terminal differentiation (Fig. 3, A and C). These analyses confirm that KRT15 and KRT10, respectively, define the progenitor vs. differentiating status, while KRT14 exhibits a broader distribution that spans both cellular states in the epidermis.

KRT15 and KRT10 expression defines the extremities of the basal keratinocyte differentiation spectrum. (A) Top 24 correlated genes for KRT15 and KRT10 in cells isolated from human trunk skin. (B) Bar graph showing all GO categories enriched for KRT15-correlated genes with a cutoff of P < 0.05 from GProfiler. (C) Bar graph showing all GO categories enriched for KRT10-correlated genes with a cutoff of P < 0.05 from GProfiler.

KRT15 and KRT10 expression defines the extremities of the basal keratinocyte differentiation spectrum. (A) Top 24 correlated genes for KRT15 and KRT10 in cells isolated from human trunk skin. (B) Bar graph showing all GO categories enriched for KRT15-correlated genes with a cutoff of P < 0.05 from GProfiler. (C) Bar graph showing all GO categories enriched for KRT10-correlated genes with a cutoff of P < 0.05 from GProfiler.

Attributes of KRT15-expressing keratinocytes are also manifested in human foreskin and mouse back skin

Relative to trunk skin, KRT15 is more prominently expressed in human foreskin (Fig. S2, A−D). Still, the basic attributes defining KRT15 expression in human trunk (thin) skin (Fig. 2) apply to this tissue (Fig. S2). Partitioning keratinocytes into quartiles according to the composite basal score (see Materials and methods) highlights an enrichment for KRT15 in keratinocytes within the quartiles showing the highest basal score and an enrichment for KRT10 within the quartiles showing the lowest basal score (Fig. S2 E). KRT14, on the other hand, manifests a hybrid character in this analysis (Fig. S2 E). A similar outcome is seen when organizing clusters according to the ratio of basal-to-differentiating scores (compare Fig. S2 F with Fig. 2 F). Besides, an enrichment for G2/Mhigh keratinocytes in KRT14high keratinocytes is also maintained while a fraction of KRT15high keratinocytes show a high G2/M score in foreskin (Fig. S2 G). Further, relative to trunk skin, the correlation between KRT5 and KRT15 expression is stronger in foreskin (R2 = 0.43 vs. R2 = 0.31, respectively), while the KRT5–KRT14 and KRT1–KRT10 pairings still manifest a remarkably high correlation (R2 = 0.73 vs. R2 = 0.84, respectively; Fig. S2, H and H′). While showing more prominent expression in foreskin, KRT15 retains its character as a transcript that is enriched in a subpopulation of progenitor keratinocytes showing a strong basal character (Fig. S2).

Relationships between KRT14, KRT15, and KRT10 in human foreskin (complement to Fig. 2 ). (A and B) UMAP of human foreskin highlighting (A) KRT15 (green) vs. KRT14 levels (red) and (B) KRT15 (green) vs. KRT10 levels (red) across Seurat clusters. (C) sc expression of KRT15 mapped against KRT14 levels in 24,768 keratinocytes in the foreskin dataset. (D) Distribution of KRT14 and KRT15 expression across all keratinocytes in the dataset. (E) Distribution of KRT15, KRT14, and KRT10 expression in cells exhibiting increasing levels of basal score signature genes (composite scores defined in Materials and methods). (F) Analysis of average KRT14 (red, circle), KRT15 (green, square), and KRT10 (blue, triangle) expression level across nine Seurat clusters matching keratinocyte signatures in the foreskin dataset. Clusters are sorted on the x axis from those showing highest basal score to highest differentiation score. Seurat cluster matching the highest level of G2/M composite score is highlighted. (G) Expression of G2/M composite score relative to KRT14 and KRT15 levels across keratinocytes in the foreskin. (H) Comparison of linear pairwise expression between type I and type II keratins KRT14/KRT5 (red, R2 = 0.86), KRT10/KRT1 (blue, R2 = 0.92), and KRT15/KRT5 (green, R2 = 0.66) across all keratinocytes in the foreskin dataset. (H′) Heatmap summarizing Pearson’s (r) correlations between type I and type II keratins across the dataset.

Relationships between KRT14, KRT15, and KRT10 in human foreskin (complement to Fig. 2 ). (A and B) UMAP of human foreskin highlighting (A) KRT15 (green) vs. KRT14 levels (red) and (B) KRT15 (green) vs. KRT10 levels (red) across Seurat clusters. (C) sc expression of KRT15 mapped against KRT14 levels in 24,768 keratinocytes in the foreskin dataset. (D) Distribution of KRT14 and KRT15 expression across all keratinocytes in the dataset. (E) Distribution of KRT15, KRT14, and KRT10 expression in cells exhibiting increasing levels of basal score signature genes (composite scores defined in Materials and methods). (F) Analysis of average KRT14 (red, circle), KRT15 (green, square), and KRT10 (blue, triangle) expression level across nine Seurat clusters matching keratinocyte signatures in the foreskin dataset. Clusters are sorted on the x axis from those showing highest basal score to highest differentiation score. Seurat cluster matching the highest level of G2/M composite score is highlighted. (G) Expression of G2/M composite score relative to KRT14 and KRT15 levels across keratinocytes in the foreskin. (H) Comparison of linear pairwise expression between type I and type II keratins KRT14/KRT5 (red, R2 = 0.86), KRT10/KRT1 (blue, R2 = 0.92), and KRT15/KRT5 (green, R2 = 0.66) across all keratinocytes in the foreskin dataset. (H′) Heatmap summarizing Pearson’s (r) correlations between type I and type II keratins across the dataset.

Similar analyses performed in a sc transcriptomics dataset obtained from mouse back skin (see Materials and methods) show that the attributes that define KRT15 expression in human trunk skin and foreskin are largely maintained in mouse skin compartment (Fig. S3, A–H′).

Relationships between Krt14, Krt15, and Krt10 in mouse back skin (complement to Fig. 2 ). (A and B) UMAP of saline-treated, tape stripping sensitized mouse back skin highlighting Krt15 levels (green) and (A) Krt14 or (B) Krt10 levels (red) across Seurat clusters. (C) sc expression of Krt15 mapped against Krt14 levels in 4,806 keratinocytes in the mouse back skin dataset. (D) Distribution of Krt14 and Krt15 expression across all keratinocytes in the dataset. (E) Distribution of Krt15, Krt14, and Krt10 expression in cells exhibiting increasing levels of basal score signature genes (composite scores defined in Materials and methods). (F) Analysis of the average keratin expression level across 7 Seurat clusters matching keratinocyte signatures in the back skin dataset. Krt14 (red, circle), Krt15 (green, square), and Krt10 (blue, triangle) assessed per cluster. Clusters are sorted on the x axis from those showing highest basal score to highest differentiation score. Seurat cluster matching the highest level of G2/M composite score is highlighted. (G) Expression of G2/M composite score relative to Krt14 and Krt15 levels across keratinocytes in mouse sensitized back skin. (H) Comparison of linear pairwise expression between type I and type II keratins Krt14/Krt5 (red, R2 = 0.65), Krt10/Krt1 (blue, R2 = 0.19), and Krt15/Krt5 (green, R2 = 0.50) across all keratinocytes in the mouse back skin dataset. (H′) Heatmap summarizing Pearson’s (r) correlations between type I and type II keratins across the dataset.

Relationships between Krt14, Krt15, and Krt10 in mouse back skin (complement to Fig. 2 ). (A and B) UMAP of saline-treated, tape stripping sensitized mouse back skin highlighting Krt15 levels (green) and (A) Krt14 or (B) Krt10 levels (red) across Seurat clusters. (C) sc expression of Krt15 mapped against Krt14 levels in 4,806 keratinocytes in the mouse back skin dataset. (D) Distribution of Krt14 and Krt15 expression across all keratinocytes in the dataset. (E) Distribution of Krt15, Krt14, and Krt10 expression in cells exhibiting increasing levels of basal score signature genes (composite scores defined in Materials and methods). (F) Analysis of the average keratin expression level across 7 Seurat clusters matching keratinocyte signatures in the back skin dataset. Krt14 (red, circle), Krt15 (green, square), and Krt10 (blue, triangle) assessed per cluster. Clusters are sorted on the x axis from those showing highest basal score to highest differentiation score. Seurat cluster matching the highest level of G2/M composite score is highlighted. (G) Expression of G2/M composite score relative to Krt14 and Krt15 levels across keratinocytes in mouse sensitized back skin. (H) Comparison of linear pairwise expression between type I and type II keratins Krt14/Krt5 (red, R2 = 0.65), Krt10/Krt1 (blue, R2 = 0.19), and Krt15/Krt5 (green, R2 = 0.50) across all keratinocytes in the mouse back skin dataset. (H′) Heatmap summarizing Pearson’s (r) correlations between type I and type II keratins across the dataset.

A key role of the stutter cysteine in promoting the keratin-dependent sequestration of YAP1 to the cytoplasm

Previously, we utilized transfection-permissive HeLa cells to show that K14 mediates the cytoplasmic retention of YAP1 through its stutter cysteine (Guo et al., 2020). To further assess the sufficiency of the stutter cysteine in conferring this property, we generated two variants, K15 A351C and K15 CF A351C, in which a cysteine was introduced in the second position of K15’s stutter motif. In the K15 CF A351C variant, all the cysteines occurring naturally in WT K15 have been mutated to alanines (designated “CF” for cysteine-free).

Consistent with our previous findings (Guo et al., 2020), the co-expression of mCherry-K5 WT and EGFP-K14 WT (both human) in HeLa cells enabled filament polymerization and also resulted in localization of YAP1 to the cytoplasm and a decreased YAP1 nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio (Fig. 4 A; quantitation reported in Fig. 4 B). In contrast, the co-expression of mCherry-K5 (human), EGFP-K14 WT (human), and (untagged, mouse) K15 WT reduced the ability of K14 WT to redistribute YAP1 to the cytoplasm (Fig. 4, A and B). To test the hypothesis that K15’s ability to reduce the K14-dependent cytoplasmic sequestration of YAP1 is dependent on its lack of a stutter cysteine, we co-expressed mCherry-K5 and EGFP-K14 with either the K15 A351C or K15 CF A351C variant. Both K15 A351C and K15 CF A351C functioned, as well as K14 WT, in promoting YAP1 cytoplasmic sequestration (Fig. 4, A and B), establishing that the stutter cysteine indeed plays a key role in mediating the cytoplasmic sequestration of YAP1.

Stutter cysteine is sufficient to relocalize YAP1 in transfected HeLa cells. (A and B) Representative images and magnified insets of HeLa cells transfected with mCherry-K5, EGFP-K14, and untagged WT and mutant K15. The mCherry signal is autofluorescence, and YAP1 is visualized through indirect immunostaining. Yellow dashed lines outline nuclei, and green dashed line outline the cell peripheries. Scale bar, 10 µm. (C) Scatter plots representing three pooled independent replicates, displaying mean and standard deviation. Dots represent a sc. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ****P < 0.0001, ***P = 0.0002 and 0.0003, **P = 0.0083.

Stutter cysteine is sufficient to relocalize YAP1 in transfected HeLa cells. (A and B) Representative images and magnified insets of HeLa cells transfected with mCherry-K5, EGFP-K14, and untagged WT and mutant K15. The mCherry signal is autofluorescence, and YAP1 is visualized through indirect immunostaining. Yellow dashed lines outline nuclei, and green dashed line outline the cell peripheries. Scale bar, 10 µm. (C) Scatter plots representing three pooled independent replicates, displaying mean and standard deviation. Dots represent a sc. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ****P < 0.0001, ***P = 0.0002 and 0.0003, **P = 0.0083.

We next sought to test the impact of K15 expression on K14-dependent relocalization of YAP1 to the cytoplasm of mouse skin keratinocyte cultures. Skin keratinocytes obtained from newborn Krt14WT/null hemizygous mouse pups were seeded for primary culture and transfected with EGFP-tagged (human) K14, K15, or K15 A351C overexpression vectors. Transfected cells were expanded for 2 days in calcium-free basal growth media before being switched to growth media containing 1.2 mM CaCl2, a physiological trigger of differentiation. Cells were calcium-treated for 24 h, fixed, and stained for YAP1. Keratinocytes in primary culture display tight cell–cell adhesions and overlapping segments of cytoplasm. Resolving cytoplasmic YAP1 signal in individual cells is therefore unfeasible, and we instead opted to specifically quantitate nuclear YAP1 as the key metric of interest. As expected, nuclear YAP1 immunostaining decreased in mock (expressing endogenous K14 WT and K15 WT) and EGFP-K14 transfected keratinocytes following calcium-induced differentiation (Fig. 5 A, with magnified insets of nuclear YAP1 shown in Fig. 5 A′; quantitation shown in Fig. 5 B).

Stutter cysteine is sufficient to relocalize YAP1 in differentiating mouse skin keratinocytes. (A) Representative micrographs of Krt14WT/null keratinocytes in primary culture transfected with EGFP-K14, EGFP-K15, or EGFP-K15 A351C, with and without 1.2 mM CaCl2 to induce differentiation. YAP1 is visualized through immunofluorescence. “Merge” panels display autofluorescent EGFP (green) and YAP1 (magenta). Arrowheads indicate EGFP-positive keratinocytes. Scale bar, 10 µm. (A′) Magnified insets of nuclei with YAP1 indirect immunofluorescence from Fig. 5 A. Arrowheads indicate EGFP-positive keratinocytes. Scale bar, 10 µm. (B) Scatter plots representing three independent replicates, pooled, displaying mean ± SD. Dots represent a sc. Comparisons were made using unpaired t tests with Welch’s correction. ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0058 and 0.0014. (C) Multiplexed immunostaining for K15 (green) and YAP1 (red). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). A dashed line specifies the basal lamina. epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. Arrowheads depict region with strong K15 and nuclear YAP1 staining. (D) XY scatter plot is comparing nuclear YAP1 intensity (arbitrary units) vs. K15 intensity (arbitrary units). Each dot represents a single basal keratinocyte. Equation for the simple linear regression of the comparison is displayed, showing a positive correlation. Regression is significantly nonzero (P < 0.0001).

Stutter cysteine is sufficient to relocalize YAP1 in differentiating mouse skin keratinocytes. (A) Representative micrographs of Krt14WT/null keratinocytes in primary culture transfected with EGFP-K14, EGFP-K15, or EGFP-K15 A351C, with and without 1.2 mM CaCl2 to induce differentiation. YAP1 is visualized through immunofluorescence. “Merge” panels display autofluorescent EGFP (green) and YAP1 (magenta). Arrowheads indicate EGFP-positive keratinocytes. Scale bar, 10 µm. (A′) Magnified insets of nuclei with YAP1 indirect immunofluorescence from Fig. 5 A. Arrowheads indicate EGFP-positive keratinocytes. Scale bar, 10 µm. (B) Scatter plots representing three independent replicates, pooled, displaying mean ± SD. Dots represent a sc. Comparisons were made using unpaired t tests with Welch’s correction. ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0058 and 0.0014. (C) Multiplexed immunostaining for K15 (green) and YAP1 (red). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). A dashed line specifies the basal lamina. epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. Arrowheads depict region with strong K15 and nuclear YAP1 staining. (D) XY scatter plot is comparing nuclear YAP1 intensity (arbitrary units) vs. K15 intensity (arbitrary units). Each dot represents a single basal keratinocyte. Equation for the simple linear regression of the comparison is displayed, showing a positive correlation. Regression is significantly nonzero (P < 0.0001).

In contrast, transfection of EGFP-K15 antagonized the calcium-induced reduction of nuclear YAP1 signal (Fig. 5, A, A′, and B), in agreement with the HeLa, in vivo morphological, and computational data presented above. On the other hand, the overexpression of knock-in stutter cysteine EGFP-K15 A351C resulted in loss of nuclear YAP1 signal in response to calcium as it did in mock and EGFP-K14 WT-transfected cells (Fig. 5, A, A′, and B). The outcome of transfection assays involving human HeLa cells and mouse keratinocytes in primary culture prompted the prediction that basal layer keratinocytes expressing K15 at higher levels should also exhibit stronger partitioning of YAP1 to the nucleus in the human epidermis in situ. Dual staining for K15 and YAP1 in sections of thin human skin epidermis reveals a significant and positive correlation between K15 signal intensity and nuclear YAP1 signal intensity (R2 = 0.15, P < 0.0001; Fig. 5 C, quantitation in Fig. 5 D). Further, nuclear YAP1 signal intensity is, similar to K15, strongest at the bottom of rete ridges (Fig. 5 C). Together, these in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo data provide direct evidence that K15, through its lack of a stutter cysteine, is poised to maintain a progenitor cellular state by promoting nuclear YAP1 localization.

A candidate 14-3-3 binding site in the N-terminal head domain of K14 is missing in K15

We next sought to assess whether K15 and K14 differ in their ability to sequester YAP1 to the cytoplasm in relation to the property of 14-3-3 binding. Previous studies have shown that the 14-3-3σ isoform, in particular, promotes in the sequestration of YAP1 in the cytoplasm at an early stage of keratinocyte differentiation in interfollicular epidermis (Sambandam et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2015). Moreover, co-immunoprecipitation and proximity ligation assays (PLAs) have shown that K14 physically associates with, and is spatially proximal to, 14-3-3σ in newborn mouse skin keratinocytes (Guo et al., 2020), though the cis-acting determinant(s) involved remain unknown. On the other hand, using PLAs, Ievlev et al. (2023) reported that unlike K14, K15 lacks spatial proximity to 14-3-3σ in human surface airway epithelial cells in culture and concluded that K15 does not bind 14-3-3σ and thus cannot regulate YAP1 like K14 does.

14-3-3 adaptor proteins typically bind their client proteins, including YAP1 (Pocaterra et al., 2020), in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (Pennington et al., 2018). Many IF proteins, in addition to K14, can bind 14-3-3 adaptors. For human K17 (Kim et al., 2006), human K18 (Ku et al., 1998), Xenopus K19 (Mariani et al., 2020), and human vimentin (Tzivion et al., 2000), studies have shown that specific serine residues located in the N-terminal head domain mediate the interaction with 14-3-3 adaptors. 14-3-3-Pred software (Madeira et al., 2015) predicts two strong potential binding sites in human K14, S33, and S44, with S44 receiving the highest score (Fig. S4 A). S44 in human K14 is orthologous to S44 in K17, previously shown to mediate 14-3-3σ binding (Kim et al., 2006). Analyzing the mouse K14 sequence via 14-3-3-Pred identifies S40 (Fig. 1 A), which is orthologous to S44 in human K14, as the most probable 14-3-3 binding site (Fig. S4, A and A′). Finally, our mass spectrometry analyses show that K14’s S39 and S44 are phosphorylated in human N-TERT keratinocytes in culture (Fig. S4, D and D′). Given this evidence, we hypothesized that the S39CRAPS44 motif in human K14’s N-terminal head domain (see Fig. 1 A), which is perfectly conserved in mouse, mediates interaction with 14-3-3σ. The corresponding sequence in human and mouse K15, G29FGGGS34 (numbering for the human ortholog; see Fig. 1 A), is markedly different. Accordingly, we generated a human K14 variant in which the SCRAPS motif in the N-terminal head domain is mutated to GFGGGS, and a human K15 variant in which GFGGGS is replaced with K14’s SCRAPS motif. These two newly generated variants were tested for their ability to regulate the subcellular distribution of YAP1 and their spatial proximity and physical interaction with 14-3-3 in epithelial cells in culture.

Analyses of keratin and 14-3-3 protein interactions (complement to Fig. 6 ). (A–C′) Lollipop plots displaying the 14-3-3-Pred “consensus score” for all serines and threonines in (A) human KRT14; (A′) mouse Krt14; (B) human KRT5; (B′) mouse Krt5; (C) human KRT15; (C′) mouse Krt15. Lollipop height and color both scale to consensus score magnitude. The two residues with the largest positive consensus score are labeled. (D) Lollipop plot illustrates identified phosphorylation sites on K14 protein exhibiting a localization score >0.6 in human N-TERT keratinocytes in culture. The relative occupancy percentage for each phosphorylation site was calculated by dividing the phosphopeptide’s intensity by total intensity of unique K14 peptides. This calculation, shown here as relative phosphorylation site occupancy (%), was performed only for phosphopeptides that are unique to K14 without miscleavages (S44, S281, S435, S437). (D′) Spectra of the phosphopeptides corresponding to the S39 (left) and S44 (right) sites. “Phos” conveys phosphorylation, and “CAM” stands for carbamidomethyl. (E) Representative micrographs of YAP1-14-3-3σ PLA performed on transfected HeLa cells. Cells were transfected with untagged K5 and WT and mutant K14 or K15. Merge panels show PLA punctae (red), EGFP-tagged keratin autofluorescence (green), and DAPI counterstain (blue). Scale bar = 10 µm.

Analyses of keratin and 14-3-3 protein interactions (complement to Fig. 6 ). (A–C′) Lollipop plots displaying the 14-3-3-Pred “consensus score” for all serines and threonines in (A) human KRT14; (A′) mouse Krt14; (B) human KRT5; (B′) mouse Krt5; (C) human KRT15; (C′) mouse Krt15. Lollipop height and color both scale to consensus score magnitude. The two residues with the largest positive consensus score are labeled. (D) Lollipop plot illustrates identified phosphorylation sites on K14 protein exhibiting a localization score >0.6 in human N-TERT keratinocytes in culture. The relative occupancy percentage for each phosphorylation site was calculated by dividing the phosphopeptide’s intensity by total intensity of unique K14 peptides. This calculation, shown here as relative phosphorylation site occupancy (%), was performed only for phosphopeptides that are unique to K14 without miscleavages (S44, S281, S435, S437). (D′) Spectra of the phosphopeptides corresponding to the S39 (left) and S44 (right) sites. “Phos” conveys phosphorylation, and “CAM” stands for carbamidomethyl. (E) Representative micrographs of YAP1-14-3-3σ PLA performed on transfected HeLa cells. Cells were transfected with untagged K5 and WT and mutant K14 or K15. Merge panels show PLA punctae (red), EGFP-tagged keratin autofluorescence (green), and DAPI counterstain (blue). Scale bar = 10 µm.

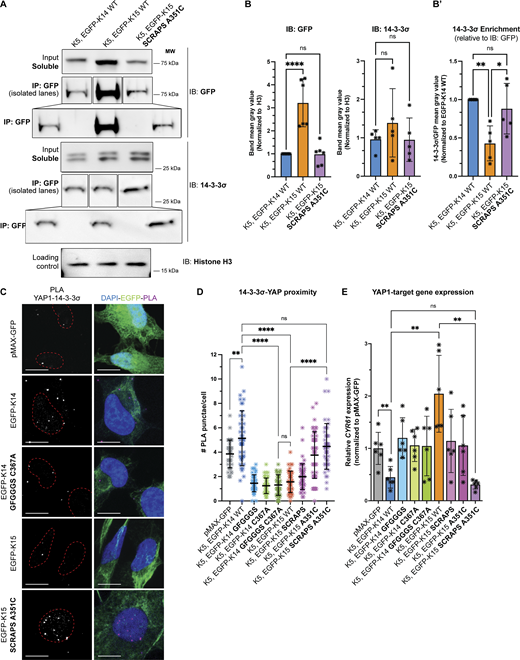

HeLa cells were cotransfected with K5 and either EGFP-K14 WT, EGFP-K15 WT, or EGFP-K15-SCRAPS-A351C and initially processed for immunoprecipitation of GFP, a shared determinant, from the detergent-soluble pool (see Materials and methods). 14-3-3σ was reproducibly detected in GFP immunoprecipitates from all three transfection combinations, indicating that it physically interacts with K14, K15, and K15 SCRAPS A351C (Fig. 6 A; quantitation shown in Fig. 6 B). However, the amount of EGFP-K15 WT protein detected in the soluble pool and in the GFP immunoprecipitate fractions was significantly larger than that detected in EGFP-K14 WT and EGFP-K15 SCRAPS A351C proteins (Fig. 6, A and B), suggesting that WT K15 protein is more readily detergent-soluble. To address this bias, we normalized the signal for 14-3-3σ against that of GFP and the resulting ratios suggest that there was more than twofold more 14-3-3σ in the EGFP-K14 WT and EGFP-K15 SCRAPS A351C immunoprecipitates than in the EGFP-K15 WT immunoprecipitate (see “14-3-3σ enrichment” chart in Fig. 6 B). Such findings show that consistent with the 14-3-3-Pred analysis reported in Fig. S4, A, A′, C, and C′, both K14 and K15 can physically associate with 14-3-3σ, directly or indirectly. When factoring in the differences observed in IP detergent solubility, they also suggest that K15 has a lower affinity for the relevant 14-3-3σ–containing complexes that are remediated by replacing “GFGGGS” with SCRAPS in its head domain. Finally, we cannot exclude that K5 plays a role in the interaction with 14-3-3σ in this setting—of note, two specific sites in each of human and mouse K5 are predicted to confer 14-3-3 binding (Fig. S4, B and B′).

SCRAPS motif and the stutter cysteine are required to interconvert YAP1 interaction between K14 and K15. (A) Representative co-immunoprecipitations of HeLa cells transfected with untagged K5 and EGFP-tagged WT K14, K15, and mutant K15. Pull-down of endogenous 14-3-3σ is depicted. (B) Differential levels of WT K15, relative to WT K14 or mutant K15, were observed in the soluble fraction. Transfection of keratin(s) did not affect endogenous 14-3-3σ levels. WB intensity was normalized to a loading control (histone H3). Dots represent three independent replicates, displaying mean and standard error. Comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA, ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant. (B′) Endogenous 14-3-3σ pulls down more efficiently with WT K14 and mutagenized K15, as compared to WT K15. Equation to calculate 14-3-3σ pull-down efficiency is described in Materials and methods. Dots represent three independent replicates. Comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA, **P = 0.0055, *P = 0.0237, ns = not significant. (C) Representative micrographs of YAP1-14-3-3σ PLA performed on transfected HeLa cells. Cells were transfected with untagged K5 and EGFP-tagged WT and mutant K14 or K15. Merge panels show PLA punctae (red), EGFP-tagged keratin autofluorescence (green), and DAPI counterstain (blue). Scale bar = 10 µm. (D) Scatter plots representing YAP1-14-3-3σ PLA punctae counted per cell in three pooled independent replicates, displaying mean and standard deviation. Dots represent a sc. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0033, ns = not significant. (E) Transcription of a YAP1 target gene, CYR61, as measured via RT-qPCR in HeLa cells transfected with untagged K5 and WT and mutant K14 or K15. Dots represent six independent replicates. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests, **P = 0.0033, ns = not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

SCRAPS motif and the stutter cysteine are required to interconvert YAP1 interaction between K14 and K15. (A) Representative co-immunoprecipitations of HeLa cells transfected with untagged K5 and EGFP-tagged WT K14, K15, and mutant K15. Pull-down of endogenous 14-3-3σ is depicted. (B) Differential levels of WT K15, relative to WT K14 or mutant K15, were observed in the soluble fraction. Transfection of keratin(s) did not affect endogenous 14-3-3σ levels. WB intensity was normalized to a loading control (histone H3). Dots represent three independent replicates, displaying mean and standard error. Comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA, ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant. (B′) Endogenous 14-3-3σ pulls down more efficiently with WT K14 and mutagenized K15, as compared to WT K15. Equation to calculate 14-3-3σ pull-down efficiency is described in Materials and methods. Dots represent three independent replicates. Comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA, **P = 0.0055, *P = 0.0237, ns = not significant. (C) Representative micrographs of YAP1-14-3-3σ PLA performed on transfected HeLa cells. Cells were transfected with untagged K5 and EGFP-tagged WT and mutant K14 or K15. Merge panels show PLA punctae (red), EGFP-tagged keratin autofluorescence (green), and DAPI counterstain (blue). Scale bar = 10 µm. (D) Scatter plots representing YAP1-14-3-3σ PLA punctae counted per cell in three pooled independent replicates, displaying mean and standard deviation. Dots represent a sc. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0033, ns = not significant. (E) Transcription of a YAP1 target gene, CYR61, as measured via RT-qPCR in HeLa cells transfected with untagged K5 and WT and mutant K14 or K15. Dots represent six independent replicates. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests, **P = 0.0033, ns = not significant. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

We next compared the ability of K14, K15, and their variants to promote spatial proximity between YAP1 and 14-3-3σ in transfected HeLa cells using PLAs. The co-expression of untagged K5 WT (human) and EGFP-K14 WT (human) in HeLa cells resulted in a robust PLA signal when probing for YAP1 and 14-3-3σ (Fig. 6 C; signal quantitation reported in Fig. 6 D). By comparison, the co-expression of mCherry-K5 and either EGFP-K14 C367A, EGFP-K14 GFGGGS, or EGFP-K14 GFGGGS C367A double mutant was ineffective at promoting YAP1/14-3-3σ physical proximity (Fig. 6, C and D). These findings confirm previous studies of the K14 C367A variant (Guo et al., 2020) and support the notion that the SCRAPS motif in K14’s N-terminal head plays a role in the subcellular partitioning of YAP1 via 14-3-3σ interaction. In contrast, relative to EGFP-K14 WT, the co-expression of K5 WT and EGFP-K15 WT is as ineffective as EGFP-K14 C367A, EGFP-K14 GFGGGS, and EGFP-K14 GFGGGS C367A at promoting YAP1/14-3-3σ physical proximity (Fig. 6, C and D). The addition of both the SCRAPS motif and the stutter cysteine to K15 (EGFP-K15 SCRAPS A351C double mutant) yielded a YAP1/14-3-3σ PLA signal that is statistically the same as EGFP-K14 WT (Fig. 6, C and D). While EGFP-K15 A351C was able to promote an intermediate level of YAP1/14-3-3σ proximity, the EGFP-K15 SCRAPS variant was equivalent to EGFP-K15 WT (Fig. 6, C and D). Such PLA findings suggest that the stutter cysteine and the SCRAPS motif each contribute significantly to promoting spatial proximity between K14 and YAP1, mediated via 14-3-3σ, in the cytoplasm, while the capacity of WT K15 to do so is markedly impaired because it lacks these two specific determinants.

Finally, to examine whether these cytoplasmic interaction(s) impair YAP1 transcriptional activity, we assessed the transcriptional output of YAP1 by measuring CYR61 mRNA levels using RT-qPCR in transfected HeLa cells. CYR61, also known as CCN1, is a bona fide and robust YAP1 target gene (see Ma et al., 2017). The reference in this assay is CYR61 measured in cells transfected with pMAX-GFP alone (set at a value of 1 across replicates; see Fig. 6 E). As previously shown (Guo et al., 2020), cells co-transfected with K5 and EGFP-K14 WT show a dramatic reduction in CYR61 transcripts, while cells co-transfected with K5 and EGFP-K14 C367A do not (Fig. 6 E), setting up the stage for assessing the properties of variants in K14 and K15 WT. We found that EGFP-K14 GFGGGS and EGFP-K14 GFGGGS C367A were equally ineffective at attenuating the transcription of CYR61 (Fig. 6 E and Fig. S4 E), showing that replacing SCRAPS with GFGGGS in the head domain of K14 abrogates the latter’s intrinsic ability to mitigate YAP1-dependent transcription. Remarkably, CYR61 transcripts were markedly higher in cells cotransfected with K5 and EGFP-K15 WT compared with the pMAX-GFP reference (Fig. 6 E), indicating that K15 is unable to negatively regulate YAP1 (a finding that is consistent with the PLA data reported in Fig. 6 D). While each of the EGFP-K15 SCRAPS and EGFP-K15 A351C variants performed better than EGFP-K15 WT in this assay (Fig. S4 E), only EGFP-K15 SCRAPS A351C was as effective as EGFP-K14 WT in attenuating the transcriptional activity of YAP1 when co-transfected with K5 in HeLa cells (Fig. 6 E). These findings confirm and extend the functional relevance of the PLA data (see Fig. 6 D) in clearly demonstrating that K14 and K15 markedly differ in their ability to control YAP1 activity, correlating tightly with regulation of its subcellular localization and spatial proximity to 14-3-3σ. Mechanistically, these findings confirm a key role of the stutter Cys in coil 2 of the rod domain and uncover a role of the SCRAPS motif in N-terminal head domain of K14 for the property of YAP1 regulation. This said, our findings also highlight the complexity of the interaction between keratins and 14-3-3σ with regard to this role (see Discussion). Finally, we cannot formally rule out that the manipulation of K14 and K15 sequences using mutagenesis, along with the addition of GFP tags, has had unintended consequences that contributed to the outcome of our studies.

K15 overrepresentation alters basal keratinocytes and the basement membrane zone in the epidermis

The experimental and computational data reported so far substantiate the notion that keratinocytes with higher levels of K15, relative to K14, possess a stronger progenitor identity. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we sought to manipulate the relative levels of K15 and K14 proteins in mouse skin. To do so, we generated a mouse strain harboring compound heterozygous alleles at the Krt14 locus—Krt14C373A/null. This strain possesses a single allele of Krt14 that is mutated at the stutter cysteine, while the Krt15 alleles are unperturbed.

Krt14C373A/null mice are viable and blister-free (see below), indicating they express sufficient K14 to maintain epithelial integrity. To assess relative levels of K14 to K15, we performed quantitative dot blotting on whole tail skin lysate harvested from 8-wk-old male Krt14C373A/null mice, with their Krt14C373A/WT littermates used as a control. Krt14C373A/null tail lysate displayed a significant 25.3% reduction in K14 mean steady state levels (Fig. S5 A). K15, in contrast, was not significantly different between Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null samples (Fig. S4 A′), confirming the alteration to the K14-to-K15 ratio in Krt14C373A/null skin.

Molecular analyses of Krt14 C373A/null transgenic mouse skin (complement to Fig. 7 ). (A and A′) K14 and (A′) K15 dot blots of whole tail skin lysate from 8-wk-old male Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermates. For K14 immunoblotting, 7.5, 5, 2.5, 1, and 0.5 µg of lysate were loaded onto a membrane. For K15 immunoblotting, 5, 2.5, 1, 0.75, and 0.5 µg of lysate were loaded onto a membrane. Histone H3 was utilized as a loading control. Mean of K14 and K15 dot-blot MGV was normalized to histone H3. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. **P = 0.0025. (B) Growth curve of mean weight of male and female Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermates. Error bars represent SD. (C) Transcription of a YAP1 target gene, Cyr61, as measured via RT-qPCR in whole tail skin lysate from 8-wk-old male and female Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermates. Dots represent three biological replicates. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. *P < 0.005.

Molecular analyses of Krt14 C373A/null transgenic mouse skin (complement to Fig. 7 ). (A and A′) K14 and (A′) K15 dot blots of whole tail skin lysate from 8-wk-old male Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermates. For K14 immunoblotting, 7.5, 5, 2.5, 1, and 0.5 µg of lysate were loaded onto a membrane. For K15 immunoblotting, 5, 2.5, 1, 0.75, and 0.5 µg of lysate were loaded onto a membrane. Histone H3 was utilized as a loading control. Mean of K14 and K15 dot-blot MGV was normalized to histone H3. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. **P = 0.0025. (B) Growth curve of mean weight of male and female Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermates. Error bars represent SD. (C) Transcription of a YAP1 target gene, Cyr61, as measured via RT-qPCR in whole tail skin lysate from 8-wk-old male and female Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermates. Dots represent three biological replicates. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. *P < 0.005.

In the progeny resulting from crosses between Krt14C373A/C373A and Krt14WT/null mice, we noticed that a subset of pups, by P4, had a plumper, darker, and slightly larger appearance as the first group of hair follicles completes differentiation and fur emerges at the skin surface (Fig. 7 A). Upon weighing, such pups were on average 10% heavier than their littermates (3.02 vs. 2.75 g; Fig.S5 B). Genotyping performed at weaning indicated that these features were completely specific to the Krt14C373A/null genotype, with no sex bias. The difference in body weight does not persist after pups were weaned such that Krt14C373A/null and Krt14C373A/WT mice were indistinguishable as young adult mice.

K15 overrepresentation alters defining attributes of basal layer keratinocytes in vivo. (A) Krt14 C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null (arrow) littermates at P5. (B) H&E staining performed on back skin harvested from P5 Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermate pups. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B′) Magnified insets of H&E-stained back skin in Fig. 5 A. Scale bar, 10 µm. (C) Epidermal thickness (µm) and hair follicle depth (µm) in back skin harvested from P5 Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermate pups. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ****P < 0.0001. (C′) Mean cytoplasmic area of basal keratinocytes with standard deviation; dots represent scs. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. *P = 0.0286. Basal cell density was calculated by mean cells/µm of basal lamina with standard deviation; dots represent individual micrographs from tail skin harvested from four littermate animals each. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. *P = 0.014. (D) H&E staining performed on tail tissue harvested from 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null tail tissue. Scale bar = 50 µm. (E) YAP1 and K15 immunofluorescence performed on 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermate tail skin. Merge panel displays DAPI counterstain (blue), YAP1 (green), and K15 (red). Arrows emphasize nuclei of suprabasal keratinocytes, showing YAP1-negative nuclei in Krt14C373A/WT tail skin and YAP1-positive nuclei in Krt14C373A/null tail skin. A dashed line specifies the basal lamina. epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. (F) Representative transmission electron microscopy micrographs of 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null basal keratinocytes in ear skin. Nu, nucleus; kf, keratin filaments; arrows, hemidesmosomes; *, areas devoid of keratin filaments. Scale bar, 800 nm. (F) Ki67 immunofluorescence performed on 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermate tail skin. Merge panel displays Ki67 (green) with DAPI counterstain (red). Arrows indicate Ki67-positive basal nuclei. A dashed line specifies the basal lamina. epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. (G) Mean of the basal lamina processed/distance covered to represent basal lamina convolution, displayed with standard deviation. Dots are individual micrograph images. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ***P = 0.0009. (G′–H′) Mean of the Ki67 MIV for individual basal keratinocyte nuclei, displayed with standard deviation. Percentages of cells above the visual threshold for Ki67 positivity (green dashed line). Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ****P < 0.0001.

K15 overrepresentation alters defining attributes of basal layer keratinocytes in vivo. (A) Krt14 C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null (arrow) littermates at P5. (B) H&E staining performed on back skin harvested from P5 Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermate pups. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B′) Magnified insets of H&E-stained back skin in Fig. 5 A. Scale bar, 10 µm. (C) Epidermal thickness (µm) and hair follicle depth (µm) in back skin harvested from P5 Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermate pups. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ****P < 0.0001. (C′) Mean cytoplasmic area of basal keratinocytes with standard deviation; dots represent scs. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. *P = 0.0286. Basal cell density was calculated by mean cells/µm of basal lamina with standard deviation; dots represent individual micrographs from tail skin harvested from four littermate animals each. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. *P = 0.014. (D) H&E staining performed on tail tissue harvested from 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null tail tissue. Scale bar = 50 µm. (E) YAP1 and K15 immunofluorescence performed on 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermate tail skin. Merge panel displays DAPI counterstain (blue), YAP1 (green), and K15 (red). Arrows emphasize nuclei of suprabasal keratinocytes, showing YAP1-negative nuclei in Krt14C373A/WT tail skin and YAP1-positive nuclei in Krt14C373A/null tail skin. A dashed line specifies the basal lamina. epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. (F) Representative transmission electron microscopy micrographs of 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null basal keratinocytes in ear skin. Nu, nucleus; kf, keratin filaments; arrows, hemidesmosomes; *, areas devoid of keratin filaments. Scale bar, 800 nm. (F) Ki67 immunofluorescence performed on 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null littermate tail skin. Merge panel displays Ki67 (green) with DAPI counterstain (red). Arrows indicate Ki67-positive basal nuclei. A dashed line specifies the basal lamina. epi, epidermis; derm, dermis. Scale bar, 50 µm. (G) Mean of the basal lamina processed/distance covered to represent basal lamina convolution, displayed with standard deviation. Dots are individual micrograph images. Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ***P = 0.0009. (G′–H′) Mean of the Ki67 MIV for individual basal keratinocyte nuclei, displayed with standard deviation. Percentages of cells above the visual threshold for Ki67 positivity (green dashed line). Comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney tests. ****P < 0.0001.

The plumper appearance of the Krt14C373A/null pups suggested that they may exhibit thicker skin, a suspicion that was confirmed through routine histology (Fig. 7 B, magnified inset in Fig. 7 B′). The increase in Krt14C373A/null skin thickness was most significant in the dermis and correlated with a general increase in hair follicle length (by 19%, on average; Fig. 7 C). The latter is consistent with the observation, reported above, that hair erupts a day earlier in Krt14C373A/null relative to Krt14C373A/WT littermates. Quantitation showed that the interfollicular epidermis was also thickened, by 35%, in the Krt14C373A/null pups (Fig. 7 C).

Upon closer examination, additional alterations were observed in the epidermis of hematoxylin/eosin (H&E)-stained sections of Krt14C373A/null skin at 8 wk. In the upper epidermis of the tail, the granular layer was reduced in both density and contrast, while the cornified layers were expanded, respectively, suggesting altered terminal differentiation and hyperkeratosis. In the lower epidermis, basal keratinocytes were crowded and showed clustering in Krt14C373A/null mice, whereas they were evenly distributed along the basal lamina in Krt14C373A/WT controls. Areas with nuclear clustering displayed muddled H&E staining (Fig. 7 D). To quantitate these features, we measured the mean surface area of basal keratinocytes and their density per unit length of dermoepidermal interface. The mean area of Krt14C373A/null basal keratinocytes was significantly smaller than Krt14C373A/WT basal keratinocytes in tail epidermis (Krt14C373A/WT: 71.50 µm2 vs. Krt14C373A/null: 66.70 µm2; Fig. 7 C′). In concurrence, the density of basal keratinocytes per µm of dermoepidermal interface was significantly increased in Krt14C373A/null keratinocytes (Krt14C373A/WT: 0.1324 cells/µm vs. Krt14C373A/null: 0.1616 cells/µm, Fig. 7 C′).

Consistent with previous reports on homozygous Krt14C373A/C373A mouse tail skin (Guo et al., 2020), the tail skin epidermis of young adult Krt14C373A/null mouse displays aberrant suprabasal nuclear YAP1 staining, in contrast to Krt14C373A/WT epidermis in which nuclear YAP1 staining is restricted to the basal layer (Fig. 7 E). Moreover, K15 staining atypically extended into the suprabasal layers of Krt14C373A/null tail skin (Fig. 7 E). As expected and in concurrence with previous reports (Guo et al., 2020), transcription of the YAP1 target gene CYR61 is also significantly increased in the tail skin epidermis of young adult Krt14C373A/null compared with Krt14C373A/WT littermates (Fig. S5 C).

We next used transmission electron microscopy to identify any ultrastructural alterations in Krt14C373A/null epidermis. We imaged skin dissected from the back, ear, and tails of 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/null and Krt14C373A/WT littermates, male and female (Fig. 7 F). Recurring observations from Krt14C373A/null skin include alterations to nuclear morphology and an increased incidence of cytoplasmic regions devoid of keratin filaments. The basal lamina in Krt14C373A/null basal keratinocytes also displays an increase in its spatial convolution and its thickness (Fig. 7 G). Additional recurrent features specific to Krt14C373A/null basal keratinocytes include more prominent hemidesmosomes, typically associated with distortions in the basal lamina, along with cytoplasmic regions devoid of keratin filaments (Fig. 7 F; see “kf”). These analyses show that K15 overrepresentation is associated with alterations to the morphological attributes of basal keratinocytes, hemidesmosomes, and the basal lamina, potentially influencing cell cycling and development, and providing in vivo evidence for a pro-progenitor role of K15 in epidermis. Whether the striking alterations observed in the skin of Krt14C373A/null mice involve the misregulation of other effectors, in addition to YAP1, is likely but unclear at this time.

Finally, to complement the data related in Fig. 2 G and test whether basal cell crowding in adult Krt14C373A/null epidermis is associated with increased cell divisions, we performed Ki67 immunofluorescence staining, a highly specific marker for cycling cells, on tail skin harvested from 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null male and female littermates. As expected, Ki67 staining is exclusively localized to the basal keratinocytes in both Krt14C373A/WT and Krt14C373A/null tissue. Krt14C373A/null tissue, however, showed a significant increase in Ki67 mean intensity value (MIV) in basal nuclei (Fig. 7 H). We next set a threshold for Ki67 positivity by determining the median Ki67 intensity for nuclei that were visually negative for Ki67 and calculated the percentage of basal cells above this threshold. In Krt14C373A/WT basal keratinocytes, 6.8% of nuclei were Ki67-positive, while 16.8% of Krt14C373A/null basal keratinocyte nuclei were Ki67-positive (Fig. 7 H′). Both parameters confirm an increase in Ki67-positive nuclei in 8-wk-old Krt14C373A/null tail tissue compared with Krt14C373A/WT littermates.

Discussion

A link between K15 expression and an epithelial stem cell character was first uncovered in the human hair bulge by Lyle et al. >25 years ago (Lyle et al., 1998). This association has since been confirmed and expanded to mouse skin (Liu et al., 2003) and to internal stratified epithelia, e.g., the esophagus (Giroux et al., 2017) (reviewed in Bose et al., 2013). Follow-up studies, in human and in mouse, have shown that Krt15high-expressing keratinocytes residing in the basal layer (and purified based on high surface levels of integrins) express markers associated with stemness (e.g., CD34, CD200, integrin B1bright, Lgr5) (Inoue et al., 2009; Jaks et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2004; Trempus et al., 2003; Tumbar et al., 2004) and are capable of reconstituting all epithelial lineages in mature hair follicles (Morris et al., 2004) and esophagus (Giroux et al., 2017). In striking contrast, Krt15low-expressing, basally located keratinocytes (which are otherwise Krt14high in character) do not exhibit this lineage potential (Morris et al., 2004). In human epidermis, K14 and K15 are co-expressed in keratinocytes at the transcript and protein levels, but the distribution of K15 is unique in many respects; unlike K14, K15 occurs in a subset of basal keratinocytes that are preferentially located in the deeper area of epidermal rete ridges, and does not persist in suprabasal keratinocytes (see Jonkman et al., 1996; Porter et al., 2000; Waseem et al., 1999; Webb et al., 2004; Whitbread and Powell, 1998; Zhan et al., 2007). We confirmed and significantly extended these observations via analyses of recent sc transcriptomics data and targeted immunostainings. As intriguing as these attributes are, however, there is, as of yet, no biochemical or mechanistic insight that accounts for the intriguing connection between K15 expression and an epithelial stem cell character in skin.

Here, we report on findings showing that owing to the lack of two key cis-acting determinants—a cysteine within the stutter of the α-helical central rod domain and the SCRAPS motif within the N-terminal head domain—K15 is unable to effectively mediate the cytoplasmic sequestration of YAP1. Accordingly, and unlike K14 (Guo et al., 2020), K15 may be unable to enact a switch in Hippo signaling, from “off” to “on,” which prompts progenitor basal keratinocytes to initiate differentiation in the epidermis (Yuan et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2011). Fig. 8 illustrates a model that integrates these new findings with our previous work focused on the K14/14-3-3σ/YAP1 interaction (Guo et al., 2020). The model proposes that a higher K15:K14 protein ratio in basal keratinocytes of the epidermis promotes the progenitor state and antagonizes their differentiation. Once KRT15 expression subsides and the K15:14 protein ratio falls below a postulated threshold (a reality favored by K15’s apparent shorter half-life [Cui et al., 2022], its higher solubility [this study], along with persistence of KRT14 expression at significant levels), K14 is able to effectively sequester YAP1 to the cytoplasm (after its specification through posttranslational modifications) and help promote the initiation of keratinocyte differentiation.

Model. Interplay between K15 and K14 in regulating YAP1’s access to the nucleus in progenitor keratinocytes of the epidermis. The model proposes that a higher K15:K14 protein ratio in basal keratinocytes of epidermis promotes the progenitor state and antagonizes differentiation. See text for details.

Model. Interplay between K15 and K14 in regulating YAP1’s access to the nucleus in progenitor keratinocytes of the epidermis. The model proposes that a higher K15:K14 protein ratio in basal keratinocytes of epidermis promotes the progenitor state and antagonizes differentiation. See text for details.

The success of our efforts to interconvert, through mutagenesis, the ability of K14 and K15 to regulate the subcellular partitioning and transcriptional role of YAP1 in keratinocytes highlights a dominant role of the stutter cysteine located in coil 2 of the central α-helical rod domain. We note that in addition to K15, two additional type I keratins associated with a stemlike epithelial character in skin, namely, K19 (Michel et al., 1996) and K24 (Wang et al., 2025), also lack the stutter cysteine, while the differentiation-specific K10 and K9 (glabrous skin) feature it (Guo et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2012). A recent effort in our laboratory focused on glabrous skin showed that as we predicted in Guo et al. (2020), K9 and its stutter cysteine are required for the cytoplasmic sequestration of YAP1 in differentiating keratinocytes of glabrous skin in vivo and epithelial cell culture ex vivo (Steiner et al., 2025, Preprint). The identity of the K14 stutter cysteine-dependent disulfides, and the mechanism(s) of their formation have emerged as open issues of significant interest (see Guo et al., 2020, for Discussion).

Besides extending the crucial role of the stutter cysteine in coil 2 of the rod domain, the findings we report here also point to a novel role of the SCRAPS motif in the N-terminal head domain of K14 toward regulating the subcellular partitioning and role of YAP1. We also show that the SCRAPS motif undergoes phosphorylation in keratinocytes and is very likely to mediate binding to 14-3-3σ, which, as mentioned above, is known to play a role in YAP1 regulation and keratinocyte differentiation (Sambandam et al., 2015; Schlegelmilch et al., 2011). Even though K15 does not feature a SCRAPS motif in its N-terminal head domain, co-IP assays showed that, nevertheless, 14-3-3σ occurs in immunoprecipitates targeted at K15. Unlike 14-3-3σ and K14, however, 14-3-3σ and K15 lack spatial proximity in keratinocytes. From this, we infer that K14 and K15 relate differently to 14-3-3σ, certainly at a spatial level, though key details are lacking. Several elements stand out as candidate contributors to the keratin/14-3-3/YAP1 interplay in keratinocytes being programmed to undergo differentiation. First, as we report here, 14-3-3-Pred predicts that K5, K14’s preferred co-polymerization partner, is itself a potential 14-3-3 binding protein. One of the high scoring potential sites for 14-3-3 binding on K5, serine 18 (see Fig. S4 B), is conserved and undergoes phosphorylation in both human and mouse keratinocytes. Accordingly, K5 could be a participant or modulator of the K14/14-3-3σ/YAP1 complex. Second, it is also possible that at its core, the K14-dependent regulation of YAP1 is not significantly dependent on 14-3-3σ, such that the significance of the SCRAPS motif lies elsewhere. Third, the presence of 14-3-3σ in GFP-K15 immunoprecipitates may reflect interactions with a non-keratin protein present in the complex. Fourth, we previously showed that the cysteine residue located within the SCRAPS motif (C40) partakes in K14-dependent disulfide bonding in keratinocytes (Feng and Coulombe, 2015a)—but whether it plays a role in YAP1 regulation has yet to be addressed. Fifth and finally, mechanical cues play a significant role as progenitor keratinocytes commit to differentiation (see Biggs et al., 2020; Miroshnikova et al., 2018; Nekrasova et al., 2018; Ning et al., 2021), and may influence biochemical interactions between keratin, 14-3-3σ, YAP1, and other relevant proteins. Future efforts are needed to define when and how, precisely, K14 and other keratins engage 14-3-3 adaptors, the specific role of phosphorylation (and the kinases involved) in these interactions, and how these events relate in space and time to the binding and regulation of YAP1.