While inputs regulating CD4+ T helper (Th) cell differentiation are well defined, the integration of downstream signaling with transcriptional and epigenetic programs that define Th lineage identity remains incompletely resolved. PI3K signaling is a critical regulator of T cell function; activating mutations affecting PI3Kδ result in an immunodeficiency with multiple T cell defects. Using mice expressing activated PI3Kδ, we found aberrant expression of proinflammatory Th1 signature genes under Th2-inducing conditions, both in vivo and in vitro. This dysregulation was driven by a PI3Kδ-IL-2-Foxo1 signaling amplification loop, fueling Foxo1 inactivation, loss of Th2 lineage restriction, and extensive epigenetic reprogramming. Surprisingly, ablation of Fasl, a Foxo1-repressed gene, normalized both Th2 differentiation and TCR signaling. BioID and imaging revealed Fas interactions with TCR signaling components, which were supported by Fas-mediated potentiation of TCR signaling that could occur in the absence of FADD. Our results highlight Fas-FasL signaling as a critical intermediate in phenotypes driven by activated PI3Kδ, thereby linking two key pathways of immune dysregulation.

Introduction

The differentiation of CD4+ T cells into distinct types of cytokine-producing T helper (Th) cell populations is critical for orchestrating immune responses to different types of infections and immune challenges (Zhu et al., 2010). Among these, Th1 cells express interferon-gamma (IFNγ), which drives activation of cellular immunity against intracellular pathogens, whereas Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which promote both hypersensitivity and tissue repair processes. Th cell differentiation requires the translation of extracellular signals from the T cell receptor (TCR) and cytokines into intracellular responses that dictate transcriptional and epigenetic signatures required to establish T cell identity. Nonetheless, how these pathways coalesce to regulate CD4+ Th cell fate remains incompletely understood.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) is a major cellular signaling hub that helps orchestrate T cell responses downstream of the TCR, cytokine receptors, and chemokine receptors (Okkenhaug, 2013). Coordination and amplification of T cell signaling, metabolism, and transcription are key features of PI3K. The importance of PI3K signaling in T cell differentiation is underscored by inborn errors of immunity (IEIs) in which altered PI3K signaling drives immune cell dysfunction (Lucas et al., 2016; Nunes-Santos et al., 2019; Tangye et al., 2019); activating mutations affecting the catalytic subunit of PI3Kδ cause activated PI3K delta syndrome type I (APDS1), an IEI characterized by recurrent respiratory infections, chronic EBV infection, lymphopenia, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy, including increased type I responses (Angulo et al., 2013; Lucas et al., 2014). Recently, it has emerged that APDS patients show a range of other clinical presentations, including Th2-driven pathologies, such as eosinophilic esophagitis, atopic dermatitis, and asthma (Bier et al., 2019; Oh et al., 2021; Tangye et al., 2019). However, both increased and reduced Th2 responses have been observed in APDS (Jia et al., 2021) and the molecular basis of T cell dysfunction, particularly in CD4+ Th cells, remains incompletely characterized.

Early activation of naïve CD4+ T cells results in the production of IL-2 and activation of STAT5, which are critical for Th1 and Th2 differentiation (Liao et al., 2011; Reem and Yeh, 1984; Yamane et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2003). In addition to STAT5, IL-2 signaling induces activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex (mTORC) 1 and mitogen-activated protein kinases (Brennan et al., 1997; Graves et al., 1992; Ray et al., 2015; Ross and Cantrell, 2018), which further promote T cell activation. Together, TCR and cytokine signals drive the induction of lineage-defining transcription factors (TFs) that specify Th cell fate, including Tbet in Th1 cells and GATA3 in Th2 cells, which in turn negatively cross-regulate one another (Zhu et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2010). In addition, numerous negative regulators must be suppressed to permit T cell activation and differentiation. One such TF that is instrumental in maintaining naïve T cell programs is Foxo1 (Hedrick et al., 2012; Kerdiles et al., 2009; Ouyang et al., 2009). Following T cell stimulation, Foxo1 is phosphorylated in a PI3K-dependent fashion, leading to its exclusion from the nucleus and targeting for degradation (Brunet et al., 1999; Kops et al., 1999). Foxo1 inhibition switches off the naïve T cell program, allowing activated cells to take on effector characteristics. In concert with these transcriptional changes, extensive epigenetic remodeling occurs during T cell activation, which reorganizes chromatin accessibility and topology to support and maintain T cell lineage adoption (Schmidl et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2022).

Although PI3K signaling has been extensively studied, the interplay between PI3K signaling and the transcriptional and epigenetic changes that occur during CD4 T cell differentiation remain unclear. Activation of PI3K drives the generation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate, leading to recruitment and activation of multiple effectors, including AKT. Activation of AKT has numerous consequences, including phosphorylation and inactivation of TFs such as Foxo1. In many cell types, PI3K and AKT are also intimately connected to the activation of mTORC1, which promotes both Th1 and Th17 differentiation, and mTORC2, which further activates AKT, and promotes both Th1 and Th2 cells (Chi, 2012; Delgoffe et al., 2009; Delgoffe et al., 2011). Accordingly, activated PI3Kδ enhances cytokine production in multiple CD4 T cell lineages (Bier et al., 2019; Preite et al., 2019). Conversely, in vitro polarization assays utilizing PI3K inhibitors or kinase-dead Pik3cdD910A/D910A CD4 T cells show impaired Th1, Th2, and Th17 differentiation (Han et al., 2012; Okkenhaug et al., 2006; Soond et al., 2010). Whether and how PI3K differentially regulates molecular signatures in distinct CD4+ Th lineages remains to be explored.

Examining the consequences of activating mutations affecting PIK3CD offers a unique opportunity to better understand the role of PI3Kδ in CD4+ T cell biology. Here, we utilized a mouse model expressing the most common variant found in APDS1 (Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice; Preite et al., 2018) to examine Th2 responses using house dust mite (HDM) sensitization, a model of allergic airway inflammation. Unexpectedly, we found that hyperactivated PI3Kδ rewires CD4 T cell differentiation with aberrant expression of IFNγ under Th2-inducing conditions both in vivo and in vitro. This dysregulation was driven by inappropriate IL-2– and PI3Kδ-induced Foxo1 inactivation, causing a loss of Th2 lineage restriction associated with altered chromatin accessibility. Surprisingly, we linked altered CD4+ T cell differentiation to elevated expression of the Foxo1-repressed gene Fasl in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells, and Fas-mediated potentiation of TCR signaling, which occurred in the absence of the adaptor molecule FADD, a component of Fas-induced apoptosis signaling. We further provide evidence of interactions between Fas and TCR signaling components, revealed by BioID-based proximity labeling and imaging. Collectively, these data uncover nonapoptotic Fas-FasL signaling as a critical amplifier of phenotypes driven by activated PI3Kδ, thereby linking two key pathways of immune dysregulation.

Results

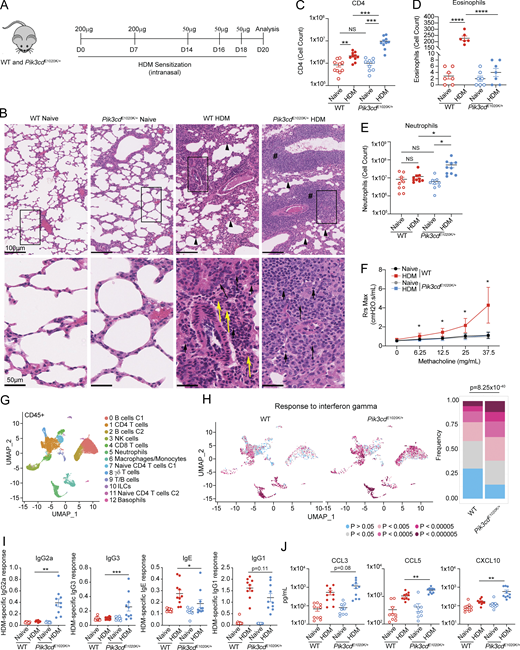

Activated PI3Kδ reshapes the HDM-induced immune response

To evaluate how activated PI3Kδ affects Th2 differentiation in vivo, we examined responses to sensitization with HDM, a model of allergic airway inflammation characterized by Th2 cell and eosinophilic infiltrates and airway hyperreactivity (Fig. 1 A). Histological staining of lung sections revealed increased immune cell infiltration in lungs of HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice relative to WT counterparts, with significantly elevated inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) (Fig. 1 B and Fig. S1 A) and increased CD4+ T cells, the primary mediators of HDM-induced responses (Fig. 1 C). However, while HDM-treated WT mice showed a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils, Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice had reduced numbers of eosinophils (Fig. 1 D) and elevated neutrophils compared with WT (Fig. 1 E). Lungs from HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice also exhibited a reduction of total mucosal area compared with both naïve Pik3cdE1020K/+ and WT HDM-treated animals, suggestive of an impaired tissue repair response (Fig. S1 B). HDM-treated WT animals showed robust airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), with elevated airway resistance in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine (Fig. 1 F). In contrast, HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ lungs completely lacked an AHR signature and instead exhibited a pattern of airway resistance similar to unsensitized naïve animals. Thus, HDM induced a robust but distinct response in mice expressing activated PI3Kδ.

Activated PI3Kδ reshapes the HDM-induced immune response. (A–J) WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals were sensitized intranasally with HDM extracts (200 μg on days 0 and 7; 50 μg on days 14, 16, and 18) and lungs examined on day 20. (A) Experimental outline. (B) H&E staining of paraffin-embedded lung sections. Top panel: Arrowheads indicate thickening of the alveolar septa; pound signs indicate iBALT. Bottom panel: Short arrows show lymphocytes, long arrows show macrophages, and yellow arrows show eosinophils. (C) CD4 T cell counts (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) measured by flow cytometry. (D) Eosinophil numbers quantified from H&E-stained lung sections. (E) Neutrophil counts (liveLineage−CD11b+Ly6G+) from lungs of the indicated animals. (F) Airway resistance (Rrs) was measured with a flexiVent instrument as cmH2O.s/ml using the indicated concentrations of methacholine. Data in E are representative of two independent experiments with n = 3–4 for each group per experiment. (G) UMAP showing clusters of lung CD45+ immune cells analyzed by scRNAseq from naïve WT, naïve Pik3cdE1020K/+, HDM-treated WT, and HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals. Each cluster was assigned a cell type using SingleR and supervised analysis of gene expression specific to each cluster (Table S1). Cells from three mice were analyzed per genotype and condition. (H) Individual lung CD45+ immune cells identified by scRNAseq analyzed for enrichment of response to IFNγ gene set. Left: UMAP visualization of enrichment P values in lung CD45+ immune cells from the indicated mice; P values described in color scale below. Right: Frequencies of cells with indicated magnitudes of enrichment P values. Statistical comparison of all CD45+ cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ HDM-treated groups was performed (chi-squared test), comparing frequencies of cells with P < 0.0005. (I) HDM-specific IgG2a, IgG3, IgE, and IgG1 from the indicated mice. (J) CCL3, CCL5, and CXCL10 (pg/ml) measured from lung homogenates from the indicated mice by Luminex. Data in C–E, I, and J are from n = 6–10 mice for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. Data in B are representative of two independent experiments. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical comparisons were made using unpaired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Activated PI3Kδ reshapes the HDM-induced immune response. (A–J) WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals were sensitized intranasally with HDM extracts (200 μg on days 0 and 7; 50 μg on days 14, 16, and 18) and lungs examined on day 20. (A) Experimental outline. (B) H&E staining of paraffin-embedded lung sections. Top panel: Arrowheads indicate thickening of the alveolar septa; pound signs indicate iBALT. Bottom panel: Short arrows show lymphocytes, long arrows show macrophages, and yellow arrows show eosinophils. (C) CD4 T cell counts (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) measured by flow cytometry. (D) Eosinophil numbers quantified from H&E-stained lung sections. (E) Neutrophil counts (liveLineage−CD11b+Ly6G+) from lungs of the indicated animals. (F) Airway resistance (Rrs) was measured with a flexiVent instrument as cmH2O.s/ml using the indicated concentrations of methacholine. Data in E are representative of two independent experiments with n = 3–4 for each group per experiment. (G) UMAP showing clusters of lung CD45+ immune cells analyzed by scRNAseq from naïve WT, naïve Pik3cdE1020K/+, HDM-treated WT, and HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals. Each cluster was assigned a cell type using SingleR and supervised analysis of gene expression specific to each cluster (Table S1). Cells from three mice were analyzed per genotype and condition. (H) Individual lung CD45+ immune cells identified by scRNAseq analyzed for enrichment of response to IFNγ gene set. Left: UMAP visualization of enrichment P values in lung CD45+ immune cells from the indicated mice; P values described in color scale below. Right: Frequencies of cells with indicated magnitudes of enrichment P values. Statistical comparison of all CD45+ cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ HDM-treated groups was performed (chi-squared test), comparing frequencies of cells with P < 0.0005. (I) HDM-specific IgG2a, IgG3, IgE, and IgG1 from the indicated mice. (J) CCL3, CCL5, and CXCL10 (pg/ml) measured from lung homogenates from the indicated mice by Luminex. Data in C–E, I, and J are from n = 6–10 mice for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. Data in B are representative of two independent experiments. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical comparisons were made using unpaired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Altered responses to HDM in Pik3cd E1020K/+ mice. Supporting data for Fig. 1. (A) iBALT area (μm2) measured in H&E-stained lung sections. (B) Mucosal area (μm2) measured in H&E-stained lung sections. (A and B)n = 5–7 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (C) Frequencies of the indicated lung CD45+ immune cell populations (clusters 0–12) identified by scRNAseq from naïve WT, naïve Pik3cdE1020K/+, HDM-treated WT, and HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals from Fig. 1 G. (D) Pathway enrichment analysis using genes upregulated in HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells relative to HDM-treated WT counterparts for indicated cell types using scRNAseq data of lung CD45+ immune cells. Pathway enrichment was performed using ShinyGo (Ge et al., 2020). (E) Cluster-specific analysis of frequencies of cells with the indicated enrichment P value for the response to IFNγ gene set. Statistical comparison of WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ HDM-treated groups for each cluster was performed (chi-squared test), comparing frequencies of cells with P < 0.0005. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical comparisons were made using unpaired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Altered responses to HDM in Pik3cd E1020K/+ mice. Supporting data for Fig. 1. (A) iBALT area (μm2) measured in H&E-stained lung sections. (B) Mucosal area (μm2) measured in H&E-stained lung sections. (A and B)n = 5–7 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (C) Frequencies of the indicated lung CD45+ immune cell populations (clusters 0–12) identified by scRNAseq from naïve WT, naïve Pik3cdE1020K/+, HDM-treated WT, and HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals from Fig. 1 G. (D) Pathway enrichment analysis using genes upregulated in HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells relative to HDM-treated WT counterparts for indicated cell types using scRNAseq data of lung CD45+ immune cells. Pathway enrichment was performed using ShinyGo (Ge et al., 2020). (E) Cluster-specific analysis of frequencies of cells with the indicated enrichment P value for the response to IFNγ gene set. Statistical comparison of WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ HDM-treated groups for each cluster was performed (chi-squared test), comparing frequencies of cells with P < 0.0005. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical comparisons were made using unpaired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) of total CD45+ cells from lungs of naïve and HDM-treated mice (Fig. 1 G and Fig. S1 C) identified 13 distinct populations of immune cells, defined by unique gene expression signatures (Table S1). For all populations, we compared differential gene expression between WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ HDM-treated mice using pathway enrichment analysis. Notably, we saw a prominent enrichment of the response to IFNγ gene set, as well as a neutrophil chemotaxis signature in multiple populations from Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice (Fig. 1 H and Fig. S1 D). Analysis of individual cells in each cluster revealed increased frequencies of cells with highly significant enrichments (P < 0.0005) of response to IFNγ signatures in Pik3cdE1020K/+ lungs, including CD4 T cells (cluster 1), CD8 T cells (cluster 4), neutrophils (cluster 5), macrophage/monocytes (cluster 6), γδ T cells (cluster 8), and B cells (clusters 0 and 2) (Fig. 1 H and Fig. S1 E). Accordingly, serum from Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice showed significantly elevated HDM-specific IgG2a and IgG3 (Fig. 1 I), which are induced through B cell class switch recombination driven by IFNγ (Snapper et al., 1988; Snapper et al., 1992), and are not observed in WT animals following HDM treatment. Conversely, Pik3cdE1020K/+ serum showed reduced HDM-specific IgE with a trend toward reduced IgG1 compared with WT (Fig. 1 I). Lung homogenates from HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals also exhibited elevated concentrations of the IFNγ-induced chemokines CCL3, CCL5, and CXCL10 (Fig. 1 J). Therefore, Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice showed a global change in polarized responses to HDM, reshaping immunity toward a type I inflammatory response.

Inappropriate Th1 responses in Pik3cdE1020K/+ lungs following HDM sensitization, at the expense of Th2 immunity

To further understand these phenotypes, we focused on CD4 T cells, which are the primary mediators of responses to HDM. Differential gene expression analysis comparing HDM-treated WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells in pseudobulk (cluster 1, Fig. 1 G) revealed reduced expression of genes characteristic of pathogenic Th2 cells in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 cells, including Gata3, Il1rl1, encoding the IL-33 receptor ST2, and Areg, encoding amphiregulin, a protein associated with tissue repair in asthma (Fig. 2 A); Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projections (UMAPs) of total CD45+ cells confirmed a severe reduction of expression of these and other key Th2 lineage–defining genes (Fig. S2 A), as well as diminished expression of IL-5 and IL-13 by ILCs. We also observed decreased IL-17A expression, despite increased neutrophil numbers (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, we observed increased expression of genes associated with a cytolytic Th1 signature in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 cells compared with WT, including Ifng, Gzmb, and Nkg7 (Fig. 2 A).

Aberrant Th1 responses at the expense of Th2 immunity in Pik3cd E1020K/+ lungs following HDM sensitization. (A) Scatter plot comparing gene expression in CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ HDM-treated mice (cluster 1 from Fig. 1 G). DEGs upregulated in WT CD4 T cells in red, and genes upregulated in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells in blue. (B) CD4+ T cells from scRNAseq of total CD45+ lung immune cells (cluster 1 from Fig. 1 G) were re-clustered to identify five unique clusters (0–4) of CD4+ T cells. Left: UMAP showing distribution of clusters 0–4; identities of each cluster were assigned based on cluster-specific gene expression. Right: Proportion of cells from each cluster in indicated mice. (C) Seurat heatmap showing expression of cluster-defining genes for indicated populations. (A–C) Cells from three mice were analyzed per genotype and condition. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of intracellular IFNγ and IL-5 expression in lung CD4+ T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) from indicated mice. (E–H) Frequencies of lung CD4+ T cells expressing (E) IL-5; (F) IL-4; (G) IFNγ; and (H) IL-2 from indicated groups. (D–H)n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (I–L) TCRα-deficient recipient mice were injected with 1 × 106 WT or Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve CD4 T cells 14 days prior to HDM sensitization. HDM was administered intranasally as indicated. n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (I) Experimental design. (J) Cell counts of lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) from the indicated groups. (K) Frequencies of IFNγ+ (left) and IL-4/5/13+ (right) lung CD4 T cells from the indicated groups. Frequencies of IL-4/5/13+ cells were calculated using Boolean (or) gating. (L) Cell counts of eosinophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G−SiglecF+) from lungs of the indicated mice. Statistical comparisons were made using unpaired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Aberrant Th1 responses at the expense of Th2 immunity in Pik3cd E1020K/+ lungs following HDM sensitization. (A) Scatter plot comparing gene expression in CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ HDM-treated mice (cluster 1 from Fig. 1 G). DEGs upregulated in WT CD4 T cells in red, and genes upregulated in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells in blue. (B) CD4+ T cells from scRNAseq of total CD45+ lung immune cells (cluster 1 from Fig. 1 G) were re-clustered to identify five unique clusters (0–4) of CD4+ T cells. Left: UMAP showing distribution of clusters 0–4; identities of each cluster were assigned based on cluster-specific gene expression. Right: Proportion of cells from each cluster in indicated mice. (C) Seurat heatmap showing expression of cluster-defining genes for indicated populations. (A–C) Cells from three mice were analyzed per genotype and condition. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of intracellular IFNγ and IL-5 expression in lung CD4+ T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) from indicated mice. (E–H) Frequencies of lung CD4+ T cells expressing (E) IL-5; (F) IL-4; (G) IFNγ; and (H) IL-2 from indicated groups. (D–H)n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (I–L) TCRα-deficient recipient mice were injected with 1 × 106 WT or Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve CD4 T cells 14 days prior to HDM sensitization. HDM was administered intranasally as indicated. n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (I) Experimental design. (J) Cell counts of lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) from the indicated groups. (K) Frequencies of IFNγ+ (left) and IL-4/5/13+ (right) lung CD4 T cells from the indicated groups. Frequencies of IL-4/5/13+ cells were calculated using Boolean (or) gating. (L) Cell counts of eosinophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G−SiglecF+) from lungs of the indicated mice. Statistical comparisons were made using unpaired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Altered CD4 + T cell differentiation in Pik3cd E1020K/+ mice in vivo. Supporting data for Fig. 2. (A) Feature plots showing expression of Th2-defining genes Il1rl1, Il4, IL5, and Il13 in scRNAseq analyses of lung CD45+ immune cells from the indicated mice. Cells from three mice were analyzed by scRNAseq per genotype and condition. (B) Flow cytometry of lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) measuring GATA3 expression in the indicated populations. n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. Left: Representative plots showing GATA3 and CD4 expression. Right: Frequencies (left) and cell counts (right) of GATA3+ CD4 T cells in the indicated groups. (C–E) Frequencies of (C) IL-13+ (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+); (D) IL-17A+ (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+), and (E) Foxp3+ (Treg) lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+) in the indicated groups, measured by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (F and G) Cytokine concentrations (pg/ml) measured from lung homogenates from the indicated mice by Luminex. Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 are shown in F, and Th1 cytokines GM-CSF and TNFα are shown in G. n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (H–L) WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals were infected intranasally with C. neoformans, and were sacrificed 10 days after infection, and lung tissue was harvested for analysis. n = 6 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (H) Experimental design. (I) Cell counts of CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+) from lungs of the indicated mice. (J) Flow cytometry of lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) measuring GATA3 and Tbet expression in the indicated populations. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots. Right: Frequencies of Tbet+ and GATA3+ CD4 T cells from the indicated groups. (K) Frequencies of IL-4/5/13+ (left), IFNγ+ (middle), and IL-2+ (right) lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+) in the indicated groups, measured by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Frequencies of IL-4/5/13+ cells were calculated using Boolean (or) gating. (L) Cell counts of eosinophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G−SiglecF+) and neutrophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G+) from lungs of the indicated mice. (M–O) Supplemental data for CD4+ T cell transfer experiments in Fig. 2, I–L. n = 9–10 mice for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (M) Cell counts (left) and frequencies (right) of GATA3+ CD4 T cells from the indicated groups. (N) Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 expression in lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) from the indicated mice. (O) Cell counts of neutrophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G+) from lungs of the indicated mice. Statistical comparisons were made using unpaired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Altered CD4 + T cell differentiation in Pik3cd E1020K/+ mice in vivo. Supporting data for Fig. 2. (A) Feature plots showing expression of Th2-defining genes Il1rl1, Il4, IL5, and Il13 in scRNAseq analyses of lung CD45+ immune cells from the indicated mice. Cells from three mice were analyzed by scRNAseq per genotype and condition. (B) Flow cytometry of lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) measuring GATA3 expression in the indicated populations. n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. Left: Representative plots showing GATA3 and CD4 expression. Right: Frequencies (left) and cell counts (right) of GATA3+ CD4 T cells in the indicated groups. (C–E) Frequencies of (C) IL-13+ (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+); (D) IL-17A+ (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+), and (E) Foxp3+ (Treg) lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+) in the indicated groups, measured by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (F and G) Cytokine concentrations (pg/ml) measured from lung homogenates from the indicated mice by Luminex. Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 are shown in F, and Th1 cytokines GM-CSF and TNFα are shown in G. n = 9–10 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (H–L) WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals were infected intranasally with C. neoformans, and were sacrificed 10 days after infection, and lung tissue was harvested for analysis. n = 6 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (H) Experimental design. (I) Cell counts of CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+) from lungs of the indicated mice. (J) Flow cytometry of lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) measuring GATA3 and Tbet expression in the indicated populations. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots. Right: Frequencies of Tbet+ and GATA3+ CD4 T cells from the indicated groups. (K) Frequencies of IL-4/5/13+ (left), IFNγ+ (middle), and IL-2+ (right) lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8− CD4+) in the indicated groups, measured by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Frequencies of IL-4/5/13+ cells were calculated using Boolean (or) gating. (L) Cell counts of eosinophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G−SiglecF+) and neutrophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G+) from lungs of the indicated mice. (M–O) Supplemental data for CD4+ T cell transfer experiments in Fig. 2, I–L. n = 9–10 mice for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (M) Cell counts (left) and frequencies (right) of GATA3+ CD4 T cells from the indicated groups. (N) Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 expression in lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) from the indicated mice. (O) Cell counts of neutrophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G+) from lungs of the indicated mice. Statistical comparisons were made using unpaired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Reclustering of CD4 T cells (cluster 1, Fig. 1 G) identified two distinct subpopulations, defined by unique gene expression patterns (Fig. 2, B and C). Cluster 1 expressed signature naïve CD4 T cell genes such as Ccr7, S1p1r, and Klf2, and was prominent in both naïve WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ animals but was reduced after HDM treatment (Fig. 2, B and C). Cluster 4, defined by expression of Gata3, Il1rl1, and Il13 as a Th2 population (Fig. 2 C), was increased in WT CD4 cells after HDM treatment. However, this cluster was virtually absent among Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells (Fig. 2 B). In contrast, cluster 0, which was defined by expression of Ifng and numerous Th1 signature genes, dominated among Pik3cdE1020K CD4 T cells after HDM treatment, despite making up only a minor fraction of WT CD4 cells.

Flow cytometry confirmed that HDM induced a population of CD4 cells expressing GATA3 in WT lungs; however, these were significantly reduced, both in number and in frequency, in lungs of Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice (Fig. S2 B), as was the frequency of CD4+ T cells producing Th2 cytokines, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (Fig. 2, D–F and Fig. S2 C). Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice also showed diminished IL-17A+ Th17 cells relative to WT counterparts (Fig. S2 D), but no differences in Foxp3+ Treg cells following HDM (Fig. 2 B and Fig. S2 E). In contrast, lungs from HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice showed elevated frequencies of IFNγ- and IL-2-expressing CD4+ T cells relative to WT (Fig. 2, G and H). Cytokine measurements from total lung homogenates confirmed significantly impaired induction of type 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 (Fig. S2 F) but elevated TNFα and GM-CSF (Fig. S2 G) in Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice. Similar results were seen in response to Cryptococcus neoformans (Fig. S2 H), a fungal pathogen that induces early Th2 responses (Dang et al., 2022), where we observed increased numbers of CD4+ T cells (Fig. S2 I), yet significantly diminished frequencies of GATA3+ CD4 T cells (Fig. S2 J), type 2 cytokine-producing cells (Fig. S2 K), and eosinophils (Fig. S2 L) in lungs of Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice relative to WT following infection. Again, significantly elevated frequencies of Tbet+ cells and IFNγ-producing CD4 T cells (Fig. S2, J and K), accompanied by increased numbers of neutrophils, were observed in lungs of Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice (Fig. S2 L). Thus, Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4+ T cells showed disproportionate Th1 differentiation at the expense of Th2 lineage adoption.

To evaluate whether these phenotypes were CD4 T cell intrinsic, naïve CD4 T cells from WT or Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice were adoptively transferred into TCRα-deficient recipients, which were then sensitized with HDM (Fig. 2 I). Like the intact animals, mice receiving Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells showed increased numbers of lung CD4 T cells (Fig. 2 J), yet impaired induction of GATA3 (Fig. S2 M), diminished frequencies of CD4 cells producing type 2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13), and elevated frequencies of IFNγ-producing CD4 cells following HDM treatment (Fig. 2 K and Fig. S2 N). Animals receiving Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells also showed reduced numbers of eosinophils (Fig. 2 L), with a trend toward increased numbers of neutrophils (Fig. S2 O), mirroring the phenotype of intact Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice. Defective type 2 responses in Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice were therefore CD4 T cell–intrinsic and not limited to HDM exposure.

Loss of Th2 lineage restriction in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells in vitro

To probe CD4+ T cell differentiation in a defined system, we examined cytokine production from isolated naïve CD4 cells that were differentiated in vitro in the presence of WT antigen-presenting cells (APCs). In contrast to in vivo responses to HDM, Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 cells differentiated in vitro under Th2 conditions in the presence of excess exogenous IL-4 gave rise to increased frequencies of Th2 cytokine–producing cells, including IL-4+ and IL-13+ cells (Fig. 3 A), yet with similar expression of GATA3 as WT Th2 cells (Fig. 3 B). However, Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells also exhibited significantly elevated frequencies of IFNγ-expressing cells relative to WT Th2 cells, which showed minimal IFNγ production (Fig. 3 C). Moreover, Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells expressed elevated Tbet, similar to that seen in WT Th1 cells (Fig. 3 D), despite the relatively normal expression of GATA3 (Fig. 3 B). Increased IFNγ expression could be detected as early as 24 h of differentiation (Fig. 3 E) and could be prevented by IFNγ blocking antibodies (Fig. S3 A). Thus, cells expressing activated PI3Kδ showed a loss of Th2 lineage restriction in vitro.

Hyperactivated PI3Kδ disrupts Th2 lineage restriction. (A–E) Naïve CD4 T cells were activated with αCD3 + αCD28 in the presence of WT T-depleted APCs under Th2-polarizing conditions (IL-4 + αIL-12) for 72 h. (A) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IL-4 and IL-13 staining in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells. Right: Percentages of IL-4+ and IL-13+ cells from the indicated mice. n = 15 for each group, from 15 independent experiments. (B) Left: Representative flow cytometry histograms showing GATA3 expression in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from the indicated mice. Right: Fold GATA3 expression (MFI normalized to WT) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from the indicated mice. n = 14 for each group, from 14 independent experiments. (C) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 staining in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells. Right: Percentages of IFNγ+ cells. (D) Left: Representative flow cytometry histograms showing Tbet expression in Th2 and WT control Th1-polarized live CD4+ cells. Right: Fold Tbet expression (MFI normalized to WT) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from the indicated mice. (C and D)n = 14 for each group, from 14 independent experiments. (E) Percentages of IFNγ+ (left) and IL-13+ (right) cells over a time course of Th2 differentiation (0, 24, 48, and 72 h). n = 10 for each group, from 10 independent experiments. (F) Bulk RNAseq of WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve CD4 T cells and in vitro polarized Th2 cells. n = 3 biological replicates for each group. Volcano plots showing DEGs in red (WT upregulated) and blue (Pik3cdE1020K/+ upregulated); DEGs defined using fold change >1.5, P < 0.05. (G) Enrichment of hallmark pathways among DEGs comparing WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells. (H) Time course of fold induction of pAKT(T308), pS6(S240/44), and pAKT(S473) in WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ live CD4+ cells during Th2 differentiation (0, 24, 48, and 72 h), measured by flow cytometry. Fold induction calculated using MFIs of the indicated readouts normalized to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. n = 5–9 for each group, from five to nine independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using ratio paired t tests. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Hyperactivated PI3Kδ disrupts Th2 lineage restriction. (A–E) Naïve CD4 T cells were activated with αCD3 + αCD28 in the presence of WT T-depleted APCs under Th2-polarizing conditions (IL-4 + αIL-12) for 72 h. (A) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IL-4 and IL-13 staining in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells. Right: Percentages of IL-4+ and IL-13+ cells from the indicated mice. n = 15 for each group, from 15 independent experiments. (B) Left: Representative flow cytometry histograms showing GATA3 expression in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from the indicated mice. Right: Fold GATA3 expression (MFI normalized to WT) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from the indicated mice. n = 14 for each group, from 14 independent experiments. (C) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 staining in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells. Right: Percentages of IFNγ+ cells. (D) Left: Representative flow cytometry histograms showing Tbet expression in Th2 and WT control Th1-polarized live CD4+ cells. Right: Fold Tbet expression (MFI normalized to WT) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from the indicated mice. (C and D)n = 14 for each group, from 14 independent experiments. (E) Percentages of IFNγ+ (left) and IL-13+ (right) cells over a time course of Th2 differentiation (0, 24, 48, and 72 h). n = 10 for each group, from 10 independent experiments. (F) Bulk RNAseq of WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve CD4 T cells and in vitro polarized Th2 cells. n = 3 biological replicates for each group. Volcano plots showing DEGs in red (WT upregulated) and blue (Pik3cdE1020K/+ upregulated); DEGs defined using fold change >1.5, P < 0.05. (G) Enrichment of hallmark pathways among DEGs comparing WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells. (H) Time course of fold induction of pAKT(T308), pS6(S240/44), and pAKT(S473) in WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ live CD4+ cells during Th2 differentiation (0, 24, 48, and 72 h), measured by flow cytometry. Fold induction calculated using MFIs of the indicated readouts normalized to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. n = 5–9 for each group, from five to nine independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using ratio paired t tests. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Analyses of in vitro polarized Th2 cells. Supporting data for Figs. 3, 4, and 5. (A) WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve CD4 T cells were Th2-polarized in the presence or absence of an αIFNγ blocking antibody. Left: Percentages of IFNγ+ cells from the indicated groups. Right: Fold Tbet expression (MFI normalized to control WT) in live CD4+ cells from the indicated groups. n = 6–8 for each group, from six to eight independent experiments. (B) Gene expression (RPKM) of Il4ra, Il12rb1, and Il12rb2 in WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells. n = 3, bulk RNAseq. (C) Naïve CD4 T cells from the indicated mice were Th2-polarized for 24 h in the absence of inhibitors. At 24 h of culture, PI3Kδ inhibitor Cal101 (10 nM) or mTOR inhibitor rapamycin (200 nM) was added to polarizing media and cells were cultured for an additional 48 h. Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 staining in live CD4+ cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments, n = 3. (D) GSEA comparing WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ transcriptomes for expression of TFT gene sets. (E) Fold induction of Foxo1 expression in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells, measured by flow cytometry and calculated by normalizing Foxo1 MFIs to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. n = 5 for each group, from five independent experiments. (F) Naïve CD4 T cells from the indicated mice were Th2-polarized in the presence or absence of αIFNγ blocking antibody, and pFoxo1(S256) was measured in live CD4+ cells from the indicated groups by flow cytometry. Fold induction was calculated by normalizing pFoxo1(S256) MFIs to WT control cells. n = 5 for each group, from five independent experiments. (G) Naïve CD4 T cells were nucleofected with Cas9-gRNA complexes containing NC or Foxo1-targeting gRNAs and underwent Th2 polarization. Representative flow cytometry histogram showing Foxo1 expression from the indicated cells, one example from nine independent experiments. (H) Naïve CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice were transduced with GFP only–, Foxo1-WT– or Foxo1-AAA–encoding retroviruses under Th2-polarizing conditions. Top: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 expression in live GFP+ CD4+ T cells cultured under Th2-polarizing conditions from the indicated groups. Bottom, percentages of IL-4+ (left), IL-13+ (middle), and IFNγ+ (right) Th2-polarized liveCD4 GFP+ T cells from the indicated groups. n = 6 for each group, from six independent experiments. (I) WT Naïve CD4 T cells were nucleofected with NC or Foxo1-targeting gRNA-Cas9 complexes and polarized under Th2 conditions in the presence or absence of an IL-2 blocking antibody. Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 expression in live CD4+ cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments, n = 5. (J) Comparison of transcriptomes from Foxo1 KO Treg cells and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells. Genes upregulated (FC >1.5, P < 0.05) in Foxo1 KO Treg36 (versus WT Treg) and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 (versus WT Th2) were compared (left), and pathway analysis (Enrichr; Xie et al., 2021) was performed on common DEGs (right). (K–M) Supplemental data related to Fig. 5, I and J, transfer of Foxo1 gRNA-treated cells. (K) Cell counts of lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) from the indicated groups. (L) Frequencies of IL-4+ lung CD4 T cells from the indicated groups. (M) Cell counts of lung eosinophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G−SiglecF+) from the indicated groups. n = 6–9 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using ratio paired t tests (A, B, E, F, and H) or unpaired t tests (K–M). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. NC, negative control.

Analyses of in vitro polarized Th2 cells. Supporting data for Figs. 3, 4, and 5. (A) WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve CD4 T cells were Th2-polarized in the presence or absence of an αIFNγ blocking antibody. Left: Percentages of IFNγ+ cells from the indicated groups. Right: Fold Tbet expression (MFI normalized to control WT) in live CD4+ cells from the indicated groups. n = 6–8 for each group, from six to eight independent experiments. (B) Gene expression (RPKM) of Il4ra, Il12rb1, and Il12rb2 in WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells. n = 3, bulk RNAseq. (C) Naïve CD4 T cells from the indicated mice were Th2-polarized for 24 h in the absence of inhibitors. At 24 h of culture, PI3Kδ inhibitor Cal101 (10 nM) or mTOR inhibitor rapamycin (200 nM) was added to polarizing media and cells were cultured for an additional 48 h. Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 staining in live CD4+ cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments, n = 3. (D) GSEA comparing WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ transcriptomes for expression of TFT gene sets. (E) Fold induction of Foxo1 expression in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells, measured by flow cytometry and calculated by normalizing Foxo1 MFIs to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. n = 5 for each group, from five independent experiments. (F) Naïve CD4 T cells from the indicated mice were Th2-polarized in the presence or absence of αIFNγ blocking antibody, and pFoxo1(S256) was measured in live CD4+ cells from the indicated groups by flow cytometry. Fold induction was calculated by normalizing pFoxo1(S256) MFIs to WT control cells. n = 5 for each group, from five independent experiments. (G) Naïve CD4 T cells were nucleofected with Cas9-gRNA complexes containing NC or Foxo1-targeting gRNAs and underwent Th2 polarization. Representative flow cytometry histogram showing Foxo1 expression from the indicated cells, one example from nine independent experiments. (H) Naïve CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice were transduced with GFP only–, Foxo1-WT– or Foxo1-AAA–encoding retroviruses under Th2-polarizing conditions. Top: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 expression in live GFP+ CD4+ T cells cultured under Th2-polarizing conditions from the indicated groups. Bottom, percentages of IL-4+ (left), IL-13+ (middle), and IFNγ+ (right) Th2-polarized liveCD4 GFP+ T cells from the indicated groups. n = 6 for each group, from six independent experiments. (I) WT Naïve CD4 T cells were nucleofected with NC or Foxo1-targeting gRNA-Cas9 complexes and polarized under Th2 conditions in the presence or absence of an IL-2 blocking antibody. Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 expression in live CD4+ cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments, n = 5. (J) Comparison of transcriptomes from Foxo1 KO Treg cells and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells. Genes upregulated (FC >1.5, P < 0.05) in Foxo1 KO Treg36 (versus WT Treg) and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 (versus WT Th2) were compared (left), and pathway analysis (Enrichr; Xie et al., 2021) was performed on common DEGs (right). (K–M) Supplemental data related to Fig. 5, I and J, transfer of Foxo1 gRNA-treated cells. (K) Cell counts of lung CD4 T cells (liveCD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8−) from the indicated groups. (L) Frequencies of IL-4+ lung CD4 T cells from the indicated groups. (M) Cell counts of lung eosinophils (liveCD45+CD3−NK1.1−CD19−CD11b+Ly6G−SiglecF+) from the indicated groups. n = 6–9 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using ratio paired t tests (A, B, E, F, and H) or unpaired t tests (K–M). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. NC, negative control.

Elevated IL-2 signaling in Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells helps drive aberrant Th2 differentiation and heightened PI3K signaling

Bulk RNAseq analysis of in vitro polarized Th2 cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice revealed remarkably few differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve CD4 T cells (Fig. 3 F). However, day 3 differentiated WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells showed several thousand DEGs (Fig. 3 F). Analysis of Il4ra, Il12rb1, and Il12rb2 indicated that Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells lacked elevated expression of Th1 and Th2 specifying cytokine receptors, suggesting that altered differentiation was not driven by abnormally high cytokine receptor expression (Fig. S3 B). However, pathway enrichment analysis of Th2-specific DEGs revealed an enrichment of the mTORC1 and MYC signaling pathways, as well as hypoxia, a pathway downstream of mTORC1 (Fig. 3 G). Time course analyses confirmed that Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells showed significantly elevated induction of pAKT(T308) following stimulation, as well as increased activation of both mTORC1, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (pS6(S240/44)), and mTORC2, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of AKT on Ser473, compared with WT (Fig. 3 H). Treatment of Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells with Cal101, a PI3Kδ-specific inhibitor, reduced cytokine production and eliminated aberrant production of IFNγ (Fig. S3 C). However, rapamycin, a mTORC1 inhibitor, only partially reduced cytokine production, with aberrant IFNγ production still present (Fig. S3 C).

We also found an enrichment of the IL-2-STAT5 signaling pathway among Th2 DEGs (Fig. 3 G); this corresponded to increased and sustained IL-2 production and pSTAT5(Y694) in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells compared with WT counterparts (Fig. 4, A–C). To determine whether Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells also respond more potently to IL-2 stimulation, cells were differentiated under Th2 conditions, rested in cytokine-free media, and then stimulated with IL-2 (Fig. 4 D). Over the course of Th2 differentiation, surface IL-2Ra (CD25) (Fig. 4 E) was similar between WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells. However, although both WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells showed similar IL-2–mediated induction of pSTAT5, Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells showed increased pS6(S240/44) in response to IL-2 (Fig. 4 G). Thus, Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells both produce more IL-2 and respond aberrantly to IL-2 stimulation.

Dysregulated IL-2 signaling rewires Th2 differentiation of Pik3cd E1020K/+ CD4 T cells. (A) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IL-2 and CD4 expression in Th2-polarized cells from the indicated mice. Right: Percentages of IL-2+ Th2 cells. n = 9 for each group, from nine independent experiments. (B, C, and E) Time course analysis (0, 24, 48, 72 h) of IL-2 production, and pSTAT5(Y694) and CD25 during Th2 polarization, measured by flow cytometry. n = 7–10 for each group, from 7–10 independent experiments. (B) Percentages of IL-2+ cells over time from the indicated mice. (C) Fold induction of pSTAT5(Y694) over time from the indicated mice. Fold induction was calculated using pSTAT5(Y694) MFIs normalized to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. (D) Schematic describing experiments shown in F and G. (E) Fold induction of CD25 expression from the indicated mice. Fold induction was calculated using CD25 MFIs normalized to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. (F and G) Th2-polarized CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ were rested in serum-free media for 4 h and subsequently stimulated with hIL-2 over the indicated time course (0, 15, 60, 120 min). n = 4–5 for each group, from four to five independent experiments. (F) Fold induction of pSTAT5(Y694) over time from the indicated mice, measured by flow cytometry. (G) Fold induction of pS6(S240/44) over time from the indicated mice, measured by flow cytometry. Fold induction was calculated using MFIs (pSTAT5(Y694) or pS6(S240/44)) normalized to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. (H–J) Naïve CD4 T cells were Th2-polarized in the presence or absence of αIL-2 blocking antibody (20 μg/ml). (H) Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 staining in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells. (I) Percentages of IL-4+ (left), IL-13+ (middle), and IFNγ+ (right) cells from the indicated mice, in the presence or absence of αIL-2. n = 11 for each group, from 11 independent experiments. (J) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing pAKT(T308) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells in the presence or absence of αIL-2. Right: Fold induction of pAKT(T308) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from the indicated groups. Fold induction was calculated by normalizing pAKT(T308) MFIs to WT control cells. n = 5 for each group, from five independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using ratio paired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Dysregulated IL-2 signaling rewires Th2 differentiation of Pik3cd E1020K/+ CD4 T cells. (A) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IL-2 and CD4 expression in Th2-polarized cells from the indicated mice. Right: Percentages of IL-2+ Th2 cells. n = 9 for each group, from nine independent experiments. (B, C, and E) Time course analysis (0, 24, 48, 72 h) of IL-2 production, and pSTAT5(Y694) and CD25 during Th2 polarization, measured by flow cytometry. n = 7–10 for each group, from 7–10 independent experiments. (B) Percentages of IL-2+ cells over time from the indicated mice. (C) Fold induction of pSTAT5(Y694) over time from the indicated mice. Fold induction was calculated using pSTAT5(Y694) MFIs normalized to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. (D) Schematic describing experiments shown in F and G. (E) Fold induction of CD25 expression from the indicated mice. Fold induction was calculated using CD25 MFIs normalized to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. (F and G) Th2-polarized CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ were rested in serum-free media for 4 h and subsequently stimulated with hIL-2 over the indicated time course (0, 15, 60, 120 min). n = 4–5 for each group, from four to five independent experiments. (F) Fold induction of pSTAT5(Y694) over time from the indicated mice, measured by flow cytometry. (G) Fold induction of pS6(S240/44) over time from the indicated mice, measured by flow cytometry. Fold induction was calculated using MFIs (pSTAT5(Y694) or pS6(S240/44)) normalized to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. (H–J) Naïve CD4 T cells were Th2-polarized in the presence or absence of αIL-2 blocking antibody (20 μg/ml). (H) Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 staining in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells. (I) Percentages of IL-4+ (left), IL-13+ (middle), and IFNγ+ (right) cells from the indicated mice, in the presence or absence of αIL-2. n = 11 for each group, from 11 independent experiments. (J) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing pAKT(T308) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells in the presence or absence of αIL-2. Right: Fold induction of pAKT(T308) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from the indicated groups. Fold induction was calculated by normalizing pAKT(T308) MFIs to WT control cells. n = 5 for each group, from five independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using ratio paired t tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To determine whether IL-2 contributes to altered phenotypes of Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells, we performed in vitro differentiation experiments in the presence or absence of an IL-2 blocking antibody (αIL-2) (Fig. 4, H–J). Both WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells showed significant reductions in frequencies of IL-4+ and IL-13+ cells in the presence of αIL-2, consistent with known roles of IL-2 in promoting Th2 differentiation (Ross and Cantrell, 2018) (Fig. 4, H and I). However, inappropriate IFNγ production by Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells was also markedly reduced by IL-2 blockade, with αIL-2–treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 showing significantly depressed frequencies of IFNγ+ cells compared with control (Fig. 4, H and I). IL-2 blockade also diminished the induction of pAKT(T308) in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells (Fig. 4 J), suggesting that IL-2 exacerbates PI3Kδ signaling in these cells.

IL-2 represses Foxo1 activity in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4+ T cells

To explore potential TFs regulated by activated PI3Kδ during Th2 differentiation, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) comparing WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells for TF target (TFT) gene expression (Fig. S3 D). We observed significant enrichment of many more TFT gene sets in WT cells compared with Pik3cdE1020K/+ including AP4, MYOD, MEIS1, and genes regulated by Foxo1 (Fig. S3 D). Notably, analysis of DEGs upregulated in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells following HDM treatment in vivo also showed significant enrichment of a Foxo1 knockout (KO) signature (Fig. 5 A). TCR-mediated activation of PI3Kδ leads to AKT-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of Foxo1; pFoxo1 was observed in response to TCR stimulation in both WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 cells (Fig. 5 B). However, while Foxo1 phosphorylation subsided in WT Th2 cells by 72 h of stimulation, pFoxo1(S256) remained high in Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells (Fig. 5 B), with decreased total Foxo1 protein in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells over the differentiation period (Fig. S3 E).

Inactivation of Foxo1 in Pik3cd E1020K/+ CD4 + T cells impairs Th2 lineage restriction. (A) Pathway enrichment of TF perturbations followed by expression gene sets performed using Enrichr (Xie et al., 2021): significantly enriched gene sets colored in blue. Genes upregulated in HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells relative to WT counterparts (Fig. 2 A) were used as input for pathway enrichment. (B) Time course (0, 24, 48, 72 h) of pFoxo1(S256) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from indicated mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots. Right: Fold induction of pFoxo1(S256) over time. Fold induction was calculated by normalizing pFoxo1(S256) MFIs to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. n = 8 for each group, from eight independent experiments. (C) GSEA comparing Th2-polarized WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ transcriptomes for the expression of Foxo1-activated (left) and Foxo1-repressed (right) gene sets. (D) Gene expression heatmap (row z-score) showing normalized RPKM values of leading edge genes from Foxo1-activated and Foxo1-repressed GSEA described in Fig. 4 C. (E) Naïve CD4+ T cells from the indicated mice were Th2-polarized in the presence or absence of αIL-2 blocking antibody. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing pFoxo1(S256). Right: Fold induction of pFoxo1(S256). Fold induction was calculated by normalizing pFoxo1(S256) MFIs to WT control cells. n = 10 for each group, from 10 independent experiments. (F) GSEA comparing control and αIL-2–treated Th2-polarized CD4 T cell transcriptomes for the expression of Foxo1-activated (top) and Foxo1-repressed (bottom) gene sets in the indicated groups. (G and H) Naïve CD4 T cells were nucleofected with gRNA-Cas9 complexes containing NC or Foxo1-targeting gRNAs and differentiated under Th2 conditions. n = 9 for each group, from nine independent experiments. (G) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 expression in live CD4+ T cells. Right: Percentages of IFNγ+ and IL-4+ cells in Th2-polarized cells. (H) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IL-2 and CD4 expression in live CD4+ T cells. Right: Percentages of IL-2+ cells in Th2-polarized cells from the indicated groups. (I and J) TCRα-deficient recipient mice were injected with 1 × 106 NC or Foxo1 gRNA-Cas9–nucleofected naïve CD4 T cells 14 days prior to HDM sensitization. n = 6–9 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (I) Experimental design. (J) Frequencies of IFNγ+ (left) and IL-2+ (right) lung CD4 T cells. Statistical comparisons used ratio paired t tests (B and E–G) or unpaired t tests (I). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. NC, negative control.

Inactivation of Foxo1 in Pik3cd E1020K/+ CD4 + T cells impairs Th2 lineage restriction. (A) Pathway enrichment of TF perturbations followed by expression gene sets performed using Enrichr (Xie et al., 2021): significantly enriched gene sets colored in blue. Genes upregulated in HDM-treated Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells relative to WT counterparts (Fig. 2 A) were used as input for pathway enrichment. (B) Time course (0, 24, 48, 72 h) of pFoxo1(S256) in Th2-polarized live CD4+ cells from indicated mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots. Right: Fold induction of pFoxo1(S256) over time. Fold induction was calculated by normalizing pFoxo1(S256) MFIs to the 0 time point of the corresponding genotype. n = 8 for each group, from eight independent experiments. (C) GSEA comparing Th2-polarized WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ transcriptomes for the expression of Foxo1-activated (left) and Foxo1-repressed (right) gene sets. (D) Gene expression heatmap (row z-score) showing normalized RPKM values of leading edge genes from Foxo1-activated and Foxo1-repressed GSEA described in Fig. 4 C. (E) Naïve CD4+ T cells from the indicated mice were Th2-polarized in the presence or absence of αIL-2 blocking antibody. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing pFoxo1(S256). Right: Fold induction of pFoxo1(S256). Fold induction was calculated by normalizing pFoxo1(S256) MFIs to WT control cells. n = 10 for each group, from 10 independent experiments. (F) GSEA comparing control and αIL-2–treated Th2-polarized CD4 T cell transcriptomes for the expression of Foxo1-activated (top) and Foxo1-repressed (bottom) gene sets in the indicated groups. (G and H) Naïve CD4 T cells were nucleofected with gRNA-Cas9 complexes containing NC or Foxo1-targeting gRNAs and differentiated under Th2 conditions. n = 9 for each group, from nine independent experiments. (G) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IFNγ and IL-4 expression in live CD4+ T cells. Right: Percentages of IFNγ+ and IL-4+ cells in Th2-polarized cells. (H) Left: Representative flow cytometry plots showing IL-2 and CD4 expression in live CD4+ T cells. Right: Percentages of IL-2+ cells in Th2-polarized cells from the indicated groups. (I and J) TCRα-deficient recipient mice were injected with 1 × 106 NC or Foxo1 gRNA-Cas9–nucleofected naïve CD4 T cells 14 days prior to HDM sensitization. n = 6–9 for each group, pooled from two independent experiments. (I) Experimental design. (J) Frequencies of IFNγ+ (left) and IL-2+ (right) lung CD4 T cells. Statistical comparisons used ratio paired t tests (B and E–G) or unpaired t tests (I). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. NC, negative control.

Using publicly available transcriptomic data, we generated lists of known Foxo1- activated and Foxo1-repressed genes (Ouyang et al., 2012) and compared transcriptomes of WT versus Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells by GSEA (Fig. 5 C and Table S2). While WT cells exhibited significantly enriched expression of Foxo1-activated genes, Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells showed significant enrichment of Foxo1-repressed gene signatures relative to WT (Fig. 5 C). Evaluation of leading-edge genes identified by GSEA (Fig. 5 D) revealed multiple relevant Foxo1-activated genes were enriched in WT cells including Sell, Ccr7, Il7r, and Bcl2. Conversely, Foxo1-repressed genes that were enriched in Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells had a notable type I immune response signature, including Ifng, Tbx21, Eomes, and Fasl.

To evaluate whether IL-2 signaling influenced Foxo1 activity, we measured pFoxo1(S256) following differentiation in the presence or absence of an IL-2 blocking antibody (Fig. 5 E). Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells showed reduced pFoxo1(S256) in αIL-2 conditions compared with control, although pFoxo1(S256) was still elevated compared with WT cells, consistent with broad effects of activated PI3Kδ. In contrast, blocking IFNγ did not significantly alter phosphorylation of Foxo1 (Fig. S3 F), although it decreased high expression of Tbet and IFNγ in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells (Fig. S3 A).

We next examined whether IL-2 signaling regulates Foxo1 transcriptional activity. GSEA comparison of transcriptomes of Th2 cells differentiated in the presence or absence of αIL-2 (Fig. 5 F) showed significant enrichment of Foxo1-activated gene signatures in both αIL-2–treated WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells, compared with controls. Conversely, both control WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells showed significant enrichment of Foxo1-repressed genes relative to αIL-2–treated cells under Th2 conditions, suggesting IL-2 contributes to the inhibition of Foxo1 transcriptional activity in CD4 T cells.

Foxo1 is critical for Th2 lineage restriction

To address whether altered Foxo1 regulation directly contributes to aberrant CD4 T cell differentiation, we targeted Foxo1 using Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes in naïve CD4 T cells prior to in vitro Th2 polarization (Fig. S3 G). Foxo1-targeted Th2-polarized cells showed elevated frequencies of IL-4+ cells, relative to negative controls (Fig. 5 G). Notably, Foxo1-deficient Th2 cells also showed aberrant production of IFNγ, recapitulating the phenotype of Pik3cdE1020K/+-polarized cells. Conversely, retroviral-mediated expression of Foxo1-WT or Foxo1-AAA, a Foxo1 mutant resistant to AKT-mediated phosphorylation, decreased Th2 cytokine production, especially in WT cells (Fig. S3 H), and markedly reduced the aberrant IFNγ production by Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells. Thus, Foxo1 activity appears to be critical to prevent inappropriate IFNγ expression in Th2 cells. Foxo1-deficient Th2 cells also showed increased frequencies of IL-2+ cells compared with controls (Fig. 5 H). However, αIL-2 treatment of Foxo1-targeted Th2-polarized cells did not dampen inappropriate IFNγ production (Fig. S3 I), suggesting that the major effects of Foxo1 inhibition functioned downstream of IL-2. Together, these results highlight a signaling amplification loop whereby increased IL-2 production in activated PI3Kδ cells further promotes Foxo1 phosphorylation and inactivation, leading to a loss of Th2 lineage restriction.

Given the nearly identical Th2 phenotypes of Foxo1-deficient and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells, we compared gene expression programs regulated by Foxo1 and PI3Kδ. Using publicly available transcriptomic data (Ouyang et al., 2012) from Foxo1-deficient Treg cells and our RNAseq analysis of Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells, we compared upregulated genes (relative to WT) from both genotypes (Fig. S3 J). From a total of 2,301 DEGs, we observed only 103 genes that were similarly upregulated in both Foxo1-deficient and Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells (Fig. S3 J), consistent with broader roles of PI3Kδ and Foxo1 that are independent of one another (Spinelli et al., 2021). However, of the common DEGs, we observed multiple genes central to the phenotypes observed in altered Th2 differentiation, including Ifng, Tbx21, Fasl, and IL4. Furthermore, pathway enrichment analysis of common DEGs showed significant enrichment of IL-2/STAT5 signaling and IFNγ response signatures (Fig. S3 J), consistent with dysregulation of these pathways in both Foxo1-deficient and activated PI3Kδ Th2 cells.

To assess the importance of Foxo1 in CD4 T cell differentiation in vivo, we adoptively transferred negative control and Foxo1-targeted naïve CD4 T cells into TCRα KO recipient mice and performed HDM sensitization (Fig. 5 I). In contrast to Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice, animals receiving Foxo1-deficient CD4 T cells showed similar numbers of CD4 T cells as negative control counterparts, suggesting that Foxo1 inactivation does not account for the PI3Kδ-mediated increase in CD4 T cell expansion (Fig. S3 K). However, Foxo1-guide RNA (gRNA)–treated CD4 T cells showed significantly elevated frequencies of IFNγ+ cells, as well as IL-2+ cells (Fig. 5 J), mirroring the phenotypes of altered cytokine production by Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells. We also observed reduced frequencies of IL-4+ CD4 T cells (Fig. S3 L), and decreased numbers of eosinophils (Fig. S3 M), in animals receiving Foxo1-gRNA–treated CD4 T cells compared with negative control counterparts. Thus, Foxo1 appears to be a major restriction factor for CD4 T cell cytokine production and Th2 lineage restriction both in vivo and in vitro.

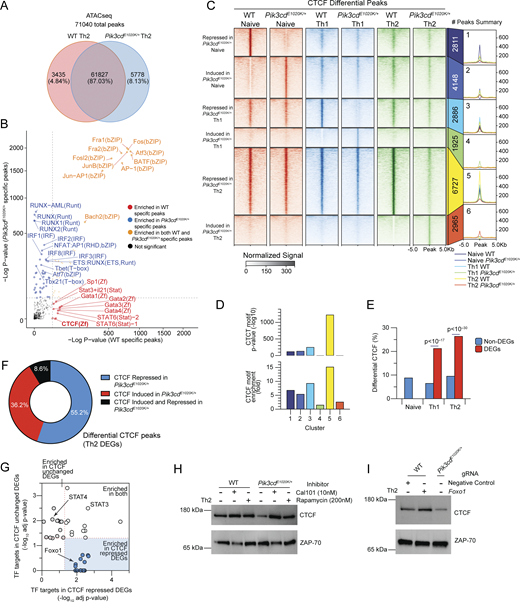

Pik3cdE1020K reshapes the epigenetic landscape of CD4+ T cells

To probe downstream consequences of activated PI3Kδ, we evaluated changes in chromatin by ATACseq analysis of in vitro differentiated WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells. Approximately 13% of their epigenomes were differentially accessible (Fig. 6 A and Fig. S4 A). Major TF motif families that were distinct among Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-specific peaks included those binding NFAT:AP1 complexes, IFN regulatory factors (IRFs), and runt-related TFs (Runx), which are all associated with T cell activation and type I responses, as well as motifs binding T-box family members, including Tbet, reflecting their altered Th1 cytokine expression (Fig. 6 B). In contrast, WT Th2-specific peaks showed enrichment of motifs associated with Th2-promoting factors, including STAT6 and GATA3 (Fig. 6 B). However, Foxo1 motifs were not enriched in either WT- or Pik3cdE1020K/+-specific peaks. Of note, in addition to these lineage- and activation-defining TFs, CTCF motifs were also differentially accessible, with a strong enrichment in WT Th2-specific peaks. CTCF functions as a global regulator of chromatin organization (Zhao et al., 2022), suggesting broad alterations associated with activated PI3Kδ.

Pik3cdE1020Kreshapes the epigenetic landscape of CD4+T cells. (A and B) Naïve CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice were polarized under Th2 conditions and evaluated by ATACseq (n = 3). A total of 71,040 peaks were detected. (A) Venn diagram of WT-specific, Pik3cdE1020K/+-specific, and common peaks. (B) WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+-specific peaks examined by motif enrichment analysis. Enrichment P values were plotted for both groups. Red: motifs specifically enriched in WT peaks; blue: motifs specifically enriched in Pik3cdE1020K/+ peaks; orange: motifs enriched in both groups. (C) Peak heatmap of CTCF CUT&Tag peaks from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve, Th1, and Th2 cells organized into six clusters (1–6) specific to each indicated population, as described. (D) CTCF motif enrichment P value (top) and fold enrichment (bottom) in clusters 1–6. (E) DEGs (WT vs Pik3cdE1020K/+) and non-DEGs from bulk RNAseq data (Fig. 3 C) were compared in the indicated populations for percentages of genes showing differential CTCF peaks (WT versus Pik3cdE1020K/+). (F) Frequencies of CTCF peaks repressed, induced, or both induced and repressed in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells (versus WT Th2) near DEGs (WT Th2 versus Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2). (G) Th2 DEGs (WT Th2 versus Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2) were organized into two categories: DEGs showing no change in CTCF (WT versus Pik3cdE1020K/+) and DEGs showing repressed CTCF peaks in Pik3cdE1020K/+ relative to WT. Pathway enrichment analysis (Enrichr; Xie et al., 2021) of TFTs (ChEA; Lachmann et al., 2010) was performed using these two categories of DEGs. Adjusted P values (−log10) of the top 25 enriched TF signatures in each category plotted against each other. (H) Western blot evaluating CTCF and Zap70 in lysates from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells, cultured in the presence or absence of Cal101 (10 nM) or rapamycin (200 nM). Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), quantified in Fig. S4 C. (I) Western blot evaluating CTCF and Zap70 in lysates from Th2-polarized NC and Foxo1 gRNA-Cas9–nucleofected WT CD4 T cells, compared with Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), Fig. S4 D. NC, negative control. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Pik3cdE1020Kreshapes the epigenetic landscape of CD4+T cells. (A and B) Naïve CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice were polarized under Th2 conditions and evaluated by ATACseq (n = 3). A total of 71,040 peaks were detected. (A) Venn diagram of WT-specific, Pik3cdE1020K/+-specific, and common peaks. (B) WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+-specific peaks examined by motif enrichment analysis. Enrichment P values were plotted for both groups. Red: motifs specifically enriched in WT peaks; blue: motifs specifically enriched in Pik3cdE1020K/+ peaks; orange: motifs enriched in both groups. (C) Peak heatmap of CTCF CUT&Tag peaks from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve, Th1, and Th2 cells organized into six clusters (1–6) specific to each indicated population, as described. (D) CTCF motif enrichment P value (top) and fold enrichment (bottom) in clusters 1–6. (E) DEGs (WT vs Pik3cdE1020K/+) and non-DEGs from bulk RNAseq data (Fig. 3 C) were compared in the indicated populations for percentages of genes showing differential CTCF peaks (WT versus Pik3cdE1020K/+). (F) Frequencies of CTCF peaks repressed, induced, or both induced and repressed in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells (versus WT Th2) near DEGs (WT Th2 versus Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2). (G) Th2 DEGs (WT Th2 versus Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2) were organized into two categories: DEGs showing no change in CTCF (WT versus Pik3cdE1020K/+) and DEGs showing repressed CTCF peaks in Pik3cdE1020K/+ relative to WT. Pathway enrichment analysis (Enrichr; Xie et al., 2021) of TFTs (ChEA; Lachmann et al., 2010) was performed using these two categories of DEGs. Adjusted P values (−log10) of the top 25 enriched TF signatures in each category plotted against each other. (H) Western blot evaluating CTCF and Zap70 in lysates from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells, cultured in the presence or absence of Cal101 (10 nM) or rapamycin (200 nM). Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), quantified in Fig. S4 C. (I) Western blot evaluating CTCF and Zap70 in lysates from Th2-polarized NC and Foxo1 gRNA-Cas9–nucleofected WT CD4 T cells, compared with Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), Fig. S4 D. NC, negative control. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Altered chromatin accessibility and CTCF activity in Pik3cd E1020K/+ Th2 cells. Supporting data for Fig. 6. (A and B) Naïve CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice underwent Th2 polarization and were examined by ATACseq. n = 3. Volcano plot showing WT-specific peaks in red and Pik3cdE1020K/+-specific peaks in blue (fold change >1.5, P < 0.05) (B) CTCF CUT&Tag tracks of Id3, Bcl2, Tbx21, and Eomes loci. (C) Quantification of CTCF protein expressed as a ratio of CTCF/Zap70. Supporting data for Fig. 5 H. n = 3 for each group, from three independent experiments. (D) Quantification of CTCF protein expressed as a ratio of CTCF/Zap70. Supporting data for Fig. 5 I. n = 3 for each group, from three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using ratio paired t tests. *P < 0.05.

Altered chromatin accessibility and CTCF activity in Pik3cd E1020K/+ Th2 cells. Supporting data for Fig. 6. (A and B) Naïve CD4 T cells from WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ mice underwent Th2 polarization and were examined by ATACseq. n = 3. Volcano plot showing WT-specific peaks in red and Pik3cdE1020K/+-specific peaks in blue (fold change >1.5, P < 0.05) (B) CTCF CUT&Tag tracks of Id3, Bcl2, Tbx21, and Eomes loci. (C) Quantification of CTCF protein expressed as a ratio of CTCF/Zap70. Supporting data for Fig. 5 H. n = 3 for each group, from three independent experiments. (D) Quantification of CTCF protein expressed as a ratio of CTCF/Zap70. Supporting data for Fig. 5 I. n = 3 for each group, from three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using ratio paired t tests. *P < 0.05.

Given these observations, we employed CUT&Tag to specifically examine genome-wide CTCF binding in WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ naïve CD4, Th2, and Th1 cells. Differential CTCF peaks, defined as at least fourfold difference in peak intensity, were grouped into six clusters, representing differential peaks between WT and Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 cells in naïve, and Th1- and Th2-polarized states (Fig. 6 C). We identified ∼7,000, 5,000, and 10,000 differential CTCF peaks in the naïve, Th1, and Th2 states, respectively, indicating significant genome-wide differences in CTCF binding in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 cells; Th2 cells showed the greatest number of peaks reduced in Pik3cdE1020K/+ cells (Fig. 6 C). We then quantified the enrichment of CTCF motifs within the peaks in each cluster. WT Th1 (cluster 3)- and Th2 (cluster 5)-specific peaks displayed strong CTCF motif enrichment (Fig. 6 D). In contrast, Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th1- and Th2-specific peaks (clusters 4 and 6, respectively) exhibited surprisingly low CTCF motif enrichment (Fig. 6 D).

We next annotated differential CTCF peaks (Fig. 6 C) to genes and compared those associated with DEGs to non-DEGs (WT versus Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells). DEGs showed significantly higher percentages of genes associated with differential CTCF peaks relative to non-DEGs, indicating changes in CTCF profiles were enriched at loci exhibiting differential gene expression (Fig. 6 E). We next considered CTCF peaks near DEGs and determined the pattern of CTCF binding in the vicinity of these genes (Fig. 6 F); the majority of DEGs with differential CTCF peaks demonstrated a loss of CTCF binding in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells (Fig. 6 F). To determine whether particular TF signatures were associated with repressed CTCF in Pik3cdE1020K/+cells, we compared TFTs enriched in DEGs associated with repressed CTCF peaks in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells with DEGs showing no change in CTCF (Fig. 5 G). Notably, DEGs associated with repressed CTCF in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells showed significant enrichment of targets for several TFs (Table S3), including Foxo1. Indeed, analysis of genomic regions surrounding both Foxo1-activated and Foxo1-repressed loci revealed altered patterns of CTCF binding in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells (Fig. S4 B), suggesting broad dysregulation of chromatin.

Given the strong loss of CTCF-DNA binding in Pik3cdE1020K/+ CD4 T cells, we examined CTCF protein expression (Fig. 6 H). Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2 cells demonstrated reduced CTCF protein compared with WT counterparts (Fig. 6 H and Fig. S4 C). Furthermore, treatment of Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells with Cal101, a PI3Kδ-specific inhibitor, restored CTCF protein to levels exceeding control WT cells, confirming a role of PI3Kδ in regulating CTCF expression (Fig. 6 H and Fig. S5 C). Inhibition of mTOR signaling via rapamycin also increased CTCF protein expression in Pik3cdE1020K/+ Th2-polarized cells compared with controls, but to a lesser extent (Fig. 6 H and Fig. S4 C). However, Foxo1-deficient Th2-polarized cells did not show reduced CTCF expression, having similar CTCF expression as WT cells (Fig. 6 I and Fig. S4 D). Thus, although activated PI3Kδ was associated with diminished CTCF protein and repressed CTCF profiles, reduced CTCF protein was not recapitulated by Foxo1 repression, suggesting that loss of CTCF was a Foxo1-independent effect of activated PI3Kδ and therefore likely not required for altered differentiation and cytokine patterns in activated PI3Kδ and Foxo1-deficient cells.