Clonal hematopoiesis driven by Tet2 deficiency in myeloid cells (TetΔMye) is prevalent in elderly individuals; however, the role of Tet2ΔMye in liver fibrosis pathogenesis remains elusive. In this study, we demonstrated that Tet2-deficient monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) promoted cellular expansion and elevated C–C motif chemokine ligand 2/8 (Ccl2/8) secretion by stabilizing their mRNAs through 5hmC-mediated alterations in RNA–protein interactions. These chemokines engaged with the upregulated C–C motif chemokine receptor (Ccr2/3) on Tet2−/− monocytes, forming a positive feedback loop that amplified pro-inflammatory MDMs (pMDMs) accumulation in liver. Tet2−/− pMDMs activated hepatic stellate cells through IL-6, driving extracellular matrix deposition and fibrotic progression. Pharmacological inhibition of Ccl2/Ccl8 with Bindarit attenuated MDMs accumulation and liver fibrosis, whereas combined therapy with Bindarit and IL-6 neutralization synergistically suppressed liver fibrosis in Tet2ΔMye mice and aged chimeric models recapitulating Tet2ΔMye-related myeloid hematopoiesis. These findings present the mechanism that Tet2ΔMye aggravates liver fibrosis and highlight MDMs depletion plus IL-6 neutralization as a promising therapy for liver fibrosis in patients with Tet2ΔMye-related myeloid hematopoiesis.

Introduction

Liver fibrosis is a pathological response to chronic liver injury, characterized by excessive deposition of extracellular matrix components, which disrupts liver architecture and function (Altamirano-Barrera et al., 2017). Globally, over half a million individuals progress from liver fibrosis to cirrhosis and ultimately to hepatocellular carcinoma annually (Doycheva et al., 2017; Friedman and Pinzani, 2022). Liver fibrosis develops as an immunogenic response to chronic injury, where monocyte and macrophage-driven inflammation activate collagen-producing cells—particularly hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), portal fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts—leading to pathological extracellular matrix accumulation (Asano et al., 2015; Heymann et al., 2009). During chronic liver injury, Ly6chigh monocytes infiltrate the liver and differentiate into pro-inflammatory monocyte-derived macrophages (pMDMs), whereas Ly6clow monocytes contribute to fibrotic “repair” macrophages (Baeck et al., 2014). Although targeting monocytes and MDMs could attenuate methionine-choline–deficient diet-induced liver fibrosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis progression in mouse models (Baeck et al., 2014; Ratziu et al., 2020; Sano et al., 2000; Chalasani et al., 2020), effective clinical therapies remain limited (Anstee et al., 2020; Ratziu et al., 2020; Sano et al., 2000).

Emerging evidence highlights the anti-inflammatory role of 10–11 translocation 2 (Tet2) in monocytes and macrophages (Fuster et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2015; Cull et al., 2017; Lv et al., 2018). However, TET2 mutations can lead to clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), a condition characterized by the skewed expansion of TET2-mutated hematopoietic stem cells and their progeny (Asada and Kitamura, 2021). Tet2-deficient hematopoietic stem cells preferentially differentiate into pro-inflammatory myeloid cells, which exhibit enhanced migration to injured liver and tissues (Marchetti et al., 2024; Wong et al., 2023). Notably, TET2 mutations in myeloid cells are detected in ∼10% of individuals over 65 years old, making CHIP significantly more prevalent in the elderly (Ferrone et al., 2020; Jaiswal and Ebert, 2019; Genovese et al., 2014).

The prevalence of liver fibrosis also increases dramatically with age, affecting over 25% of individuals aged 65 and older, even in the absence of overt liver disease (Udomsinprasert et al., 2021). This age-related susceptibility is closely associated with chronic low-grade inflammation and immune dysregulation (Franceschi et al., 2018). Previous studies have demonstrated that TET2 mutation–induced CHIP is positively correlated with both aging and the progression of advanced liver fibrosis (Marchetti et al., 2024). Recent research has further shown that age-dependent TET2 mutations promote CHIP and enhance susceptibility to chronic liver diseases by upregulating IL-6 and activating the NLRP3 inflammasome (Wong et al., 2023), indicating a potential mechanistic link between TET2 dysfunction and age-associated liver fibrosis progression.

Although previous studies have focused on Tet2 mutations in hematopoietic stem cells, this study emphasizes the role of Tet2 mutations specifically in myeloid cells (Tet2ΔMye). Because of the pivotal role of myeloid cells during liver fibrosis and the age-associated accumulation of Tet2 mutations in myeloid cells, a critical question arises: Does Tet2ΔMye-driven myeloid cell skewing exacerbate fibrosis progression during chronic liver injury? This question gains heightened significance in the context of aging, where the concurrent rise in Tet2 mutation prevalence and liver fibrosis incidence underscores the urgent need to elucidate these mechanisms for potential therapeutic interventions.

In this study, we addressed this critical question by investigating the novel mechanism of Tet2ΔMye in liver fibrosis progression. We demonstrated that Tet2ΔMye promotes fibrosis through two interconnected pathways: a C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (Ccl2)- and C–C motif chemokine ligand 8 (Ccl8)-mediated positive feedback loop, facilitated by their enhanced binding to upregulated C–C motif chemokine receptor 2/3 (Ccr2/3) on Tet2−/− monocytes, which drives the expansion of pMDMs in liver; and (2) the activation of HSCs mediated by IL-6 secreted from pMDMs. Importantly, these findings were validated in both aging and young liver fibrosis models, highlighting the universal role of Tet2ΔMye in fibrosis progression, while highlighting its heightened impact in the context of aging. These findings provide novel insights into the pathogenesis of Tet2ΔMye-associated liver fibrosis and establish a strong rationale for developing therapies targeting MDM populations and Il-6 signaling. The demonstrated efficacy of this approach in preclinical models supports its potential as a therapeutic strategy for age-related liver fibrosis in patients with Tet2ΔMye-related CHIP.

Results

Loss of Tet2 in myeloid cells exacerbates liver fibrosis

To investigate the impact of Tet2 deficiency on liver fibrosis progression under chronic injury, we established a carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis model in systemic Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔSys) mice, hepatocyte-specific Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔAlb) mice, and myeloid cell–specific Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔMye) mice (Fig. S1 A). Gross morphological analysis revealed that Tet2ΔSys-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice exhibited rounder and blunter hepatic edges with more uneven and granular liver surfaces compared with Tet2ΔAlb-CCl4 and WT littermate controls, indicating that Tet2ΔSys-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice developed more severe fibrosis (Fig. 1 A). Quantitative assessments revealed that Tet2ΔSys-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice exhibited significantly increased liver/body weight ratios (Fig. 1 B) and elevated mRNA levels of fibrosis markers, including Acta2, collagen type I alpha 1 chain (Col1a1), Pdgfr, and Timp1 (Fig. 1, C–F). Compared with Tet2WT littermates, Tet2ΔSys-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice showed upregulated protein expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen I in liver tissues (Fig. 1 G), along with increased collagens and α-SMA in situ deposition (Fig. 1, H–L). Serum analysis revealed higher levels of collagen type IV (Col IV) (Fig. 1 M) and hyaluronic acid (HA) (Fig. 1 N), as well as elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities (Fig. S1, B and C), in Tet2ΔSys-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice compared with littermate controls. Histological examination demonstrated substantial F4/80+ macrophage infiltration around intrahepatic vessels in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (Fig. S1, D–G). In contrast, Tet2ΔAlb mice showed no significant differences in collagen I and α-SMA deposition, HA and Col IV levels, AST and ALT activities, and F4/80+ macrophage infiltration compared with littermate controls (Fig. 1, A–N; and Fig. S1, B–G), indicating that Tet2ΔAlb does not markedly influence liver fibrosis progression. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that myeloid-specific, but not hepatocyte-specific, Tet2 deletion exacerbates CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice, highlighting the cell type–specific role of Tet2 in liver fibrogenesis.

Effect of Tet2ΔMyeon hepatic fibrosis progression. (A) Treatment schedule for the construction of a CCl4-induced mouse model in systemic Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔSys) mice, hepatocyte-specific Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔAlb) mice, and myeloid cell–specific Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔMye) mice. 7-wk-old male littermates (Tet2 WT or KO) were used to construct a liver fibrosis model. (B and C) Serum levels of AST (B) and ALT (C) in different types of Tet2-deficient mice with liver fibrosis (n = 5 for each group). (D) H&E staining of livers in different types of Tet2-deficient liver fibrosis mouse models. Green arrows indicate infiltrated immune cells in liver tissues. (E) IHC staining of F4/80 in liver tissues of Tet2ΔMye mice treated with oil or CCl4 (n = 4 for each group). Scale bar, 100 μm. (F and G) IF staining (F) and statistical analysis (G) of F4/80 in liver tissues of Tet2ΔMye mice treated with oil or CCl4 (n = 4 for each group). Blue: DAPI; red: anti-F4/80. (H and I) Serum levels of AST and ALT measured by serum analyzer in CD45.1 mice before (H) and after (I) transplantation of CD11b+Tet2+/+ or CD11b+Tet2−/− myeloid cells (n = 4 for each group). (J and K) mRNA levels of Acta2 (J) and Col1a1 (K) in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (L) Expression levels of α-SMA and collagen I measured by western blot. (M and N) Statistical analysis of α-SMA (M) and collagen I (N)-positive area ratio for IHC staining in liver of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (O) Serum levels of AST and ALT measured by serum analyzer in scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (P) Serum levels of HA and Col IV measured by ELISA in scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (B–O). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B, C, and G) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (H–K and M–P). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Effect of Tet2ΔMyeon hepatic fibrosis progression. (A) Treatment schedule for the construction of a CCl4-induced mouse model in systemic Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔSys) mice, hepatocyte-specific Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔAlb) mice, and myeloid cell–specific Tet2 KO (Tet2ΔMye) mice. 7-wk-old male littermates (Tet2 WT or KO) were used to construct a liver fibrosis model. (B and C) Serum levels of AST (B) and ALT (C) in different types of Tet2-deficient mice with liver fibrosis (n = 5 for each group). (D) H&E staining of livers in different types of Tet2-deficient liver fibrosis mouse models. Green arrows indicate infiltrated immune cells in liver tissues. (E) IHC staining of F4/80 in liver tissues of Tet2ΔMye mice treated with oil or CCl4 (n = 4 for each group). Scale bar, 100 μm. (F and G) IF staining (F) and statistical analysis (G) of F4/80 in liver tissues of Tet2ΔMye mice treated with oil or CCl4 (n = 4 for each group). Blue: DAPI; red: anti-F4/80. (H and I) Serum levels of AST and ALT measured by serum analyzer in CD45.1 mice before (H) and after (I) transplantation of CD11b+Tet2+/+ or CD11b+Tet2−/− myeloid cells (n = 4 for each group). (J and K) mRNA levels of Acta2 (J) and Col1a1 (K) in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (L) Expression levels of α-SMA and collagen I measured by western blot. (M and N) Statistical analysis of α-SMA (M) and collagen I (N)-positive area ratio for IHC staining in liver of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (O) Serum levels of AST and ALT measured by serum analyzer in scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (P) Serum levels of HA and Col IV measured by ELISA in scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (B–O). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B, C, and G) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (H–K and M–P). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Loss of Tet2 in myeloid cells exacerbates liver fibrosis. (A) Representative pictures of fibrotic liver from three types of Tet2-deficient mice treated with olive oil or CCl4. Sys, systemic Tet2 KO; Mye: myeloid cell–specific Tet2 KO; Alb: hepatocyte-specific Tet2 KO. 7-wk-old Tet2-deficient and Tet2-WT littermates were used to establish liver fibrosis model (n = 5 for each group). Pathological liver fibrosis lesions are indicated by green arrows in the Tet2ΔSys and Tet2ΔMye groups. Scale bar, 5 mm. (B) Statistical analysis of liver/body weight ratios of each group as shown in Fig. 1 A (n = 5 for each group). (C–F) mRNA levels of Acta2 (C), Col1a1 (D), Pdgfr (E), and Timp1 (F) in liver tissues of mice depicted in Fig. 1 A (n = 5 for each group). Gene expression levels were normalized to Gapdh. (G) Protein levels of collagen I and α-SMA in the liver tissues of different groups of mice were quantified by western blotting assay. Protein expression levels were normalized to Lamin B. (H and I) The Picrosirius red staining (scale bar, 125 μm) (H) and statistical analysis (I) of ratio of positive staining area (n = 4 for each group). Statistical analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0. (J–L) IHC staining (scale bar, 100 μm) (J) and statistical analysis of α-SMA (K) and collagen I (L) of ratio of positive staining area of liver tissues to analyze collagen deposition and expression in different groups of mice. Statistical analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (n = 4 for each group). (M and N) Serum levels of Col IV (M) and HA (N) in different types of Tet2-deficient mice with liver fibrosis (n = 5 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–N). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B–F, I, and K–N). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Timp1, TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1; Pdgfr, platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Loss of Tet2 in myeloid cells exacerbates liver fibrosis. (A) Representative pictures of fibrotic liver from three types of Tet2-deficient mice treated with olive oil or CCl4. Sys, systemic Tet2 KO; Mye: myeloid cell–specific Tet2 KO; Alb: hepatocyte-specific Tet2 KO. 7-wk-old Tet2-deficient and Tet2-WT littermates were used to establish liver fibrosis model (n = 5 for each group). Pathological liver fibrosis lesions are indicated by green arrows in the Tet2ΔSys and Tet2ΔMye groups. Scale bar, 5 mm. (B) Statistical analysis of liver/body weight ratios of each group as shown in Fig. 1 A (n = 5 for each group). (C–F) mRNA levels of Acta2 (C), Col1a1 (D), Pdgfr (E), and Timp1 (F) in liver tissues of mice depicted in Fig. 1 A (n = 5 for each group). Gene expression levels were normalized to Gapdh. (G) Protein levels of collagen I and α-SMA in the liver tissues of different groups of mice were quantified by western blotting assay. Protein expression levels were normalized to Lamin B. (H and I) The Picrosirius red staining (scale bar, 125 μm) (H) and statistical analysis (I) of ratio of positive staining area (n = 4 for each group). Statistical analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0. (J–L) IHC staining (scale bar, 100 μm) (J) and statistical analysis of α-SMA (K) and collagen I (L) of ratio of positive staining area of liver tissues to analyze collagen deposition and expression in different groups of mice. Statistical analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (n = 4 for each group). (M and N) Serum levels of Col IV (M) and HA (N) in different types of Tet2-deficient mice with liver fibrosis (n = 5 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–N). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B–F, I, and K–N). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Timp1, TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1; Pdgfr, platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Tet2ΔMye promotes intrahepatic expansion of pMDMs in liver

To elucidate the mechanism through which Tet2-deficient myeloid cells exacerbate liver fibrosis, we established a competitive myeloid chimeric mouse model through transplantation (Fig. 2 A). Lethally irradiated CD45.1 WT recipient mice were intravenously transplanted with a mixture of 20% CD45.2+Tet2−/− CD11b+ cells and 80% CD45.2+Tet2+/+CD11b+ cells (designated “KO-MT”). Control recipient mice received 20% CD45.2+Tet2+/+CD11b+ cells mixed with 80% CD45.2+Tet2+/+CD11b+ cells (designated “WT-MT”). Following transplantation, mice were administrated with CCl4 to induce liver fibrosis model. Prior to engraftment, serum levels of AST, ALT, HA, and Col IV were comparable across groups (Fig. S1, H and I). After another 3 wk of CCl4 treatment, KO-MT mice exhibited significantly elevated collagen deposition (Fig. 2 B) and higher Ishak fibrosis scores (Fig. 2 C) compared with WT-MT and scramble controls. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis revealed increased intrahepatic expression of α-SMA and collagen I in KO-MT mice (Fig. 2 D and Fig. S1, J–N), alongside elevated serum levels of AST, ALT (Fig. S1 O), HA, and Col IV (Fig. S1 P). These findings demonstrate that Tet2−/− myeloid cell engraftment is sufficient to exacerbate CCl4-induced liver fibrosis.

Tet2 ΔMye promoted intrahepatic expansion of pMDMs in liver fibrosis model. (A) Chimeric mice with liver fibrosis were constructed by transplantation of PBS (scramble), CD45.2+Tet2+/+CD11b+ myeloid cells (WT-MT), or CD45.2+Tet2−/−CD11b+ myeloid cells (KO-MT) into CD45.1 recipient mice, followed by repeated CCl4 treatment (n = 4 for each group). CD45.2+Tet2+/+ CD11b+ and CD45.2+Tet2−/− CD11b+ cells were isolated from CD45.2 Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− littermates. (B) Picrosirius red staining (scale bar, 125 μm) and statistical analysis of liver fibrosis in scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (C) Ishak score evaluation based on Sirius red staining and H&E staining in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (D) Expression levels of collagen I and α-SMA were measured by IHC (scale bar, 100 μm). (E and F) Frequency of CD45.2+ cell populations in peripheral blood (E) and liver (F) of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (G and H) IF (G) (scale bar, 50 μm) and statistical analysis (H) of CD45.2+ MDMs in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). Yellow: anti-CD45.2, blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, and green: anti-Ly6c (n = 4). (I) Statistical analysis of the frequency of CD45.2+ MDMs in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice evaluated by flow cytometry (n = 4 for each group). (J) Expansion of Tet2−/− pMDMs and Tet2−/− pMDMs was quantified by CFSE staining in vitro. Representative histograms show differences in CFSE signals between the two groups (n = 3 for each group). (K) Frequency of CD86+ MDMs (M1) and CD206+ MDMs (M2) evaluated by flow cytometry in the liver of WT-MT and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (B–K). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B, C, E, F, H, and I) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (K). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Tet2 ΔMye promoted intrahepatic expansion of pMDMs in liver fibrosis model. (A) Chimeric mice with liver fibrosis were constructed by transplantation of PBS (scramble), CD45.2+Tet2+/+CD11b+ myeloid cells (WT-MT), or CD45.2+Tet2−/−CD11b+ myeloid cells (KO-MT) into CD45.1 recipient mice, followed by repeated CCl4 treatment (n = 4 for each group). CD45.2+Tet2+/+ CD11b+ and CD45.2+Tet2−/− CD11b+ cells were isolated from CD45.2 Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− littermates. (B) Picrosirius red staining (scale bar, 125 μm) and statistical analysis of liver fibrosis in scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (C) Ishak score evaluation based on Sirius red staining and H&E staining in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (D) Expression levels of collagen I and α-SMA were measured by IHC (scale bar, 100 μm). (E and F) Frequency of CD45.2+ cell populations in peripheral blood (E) and liver (F) of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (G and H) IF (G) (scale bar, 50 μm) and statistical analysis (H) of CD45.2+ MDMs in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). Yellow: anti-CD45.2, blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, and green: anti-Ly6c (n = 4). (I) Statistical analysis of the frequency of CD45.2+ MDMs in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice evaluated by flow cytometry (n = 4 for each group). (J) Expansion of Tet2−/− pMDMs and Tet2−/− pMDMs was quantified by CFSE staining in vitro. Representative histograms show differences in CFSE signals between the two groups (n = 3 for each group). (K) Frequency of CD86+ MDMs (M1) and CD206+ MDMs (M2) evaluated by flow cytometry in the liver of WT-MT and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (B–K). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B, C, E, F, H, and I) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (K). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

To assess the distribution and lineage transformation of engrafted CD45.2+ myeloid cells, flow cytometry was performed. KO-MT mice exhibited a higher frequency of CD45.2+ cells in both peripheral blood and liver in comparison with controls (Fig. 2, E and F; and Fig. S2, A and B), indicating enhanced expansion capacity of Tet2−/− myeloid cells. Notably, KO-MT mice showed increased infiltration of CD45.2+F4/80+ macrophages, identified as Ly6chigh MDMs (Fig. 2, G–I; and Fig. S2, C–E). In vitro assays confirmed that Tet2−/− MDMs exhibited greater proliferative capacity than Tet2−/− MDMs (Fig. 2 J). Furthermore, KO-MT mice displayed a higher proportion of CD86+ pMDMs as opposed to WT-MT mice (Fig. 2 K). In summary, Tet2-deficient myeloid cells may accelerate liver fibrosis by promoting the intrahepatic expansion and pro-inflammatory polarization of Tet2−/− MDMs.

Expansion advantage of transplanted Tet2 −/− CD45.2 + CD11b + cells and change of immune cells after Clod-Lip treatment in Tet2 WT -CCl 4 and Tet2 ΔMye -CCl 4 mice. (A) Strategy for flow cytometric analysis of the proportion of CD45.2+ cells in the blood and liver of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice. (B) Representative graphs of CD45.2+ cells in peripheral blood and liver of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice. (C) Flow cytometry strategy and statistical analysis of CD45.2+ F4/80+ cell frequency in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4). (D) Flow cytometry strategy for MDMs frequency in liver tissue of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice. (E and F) Strategy for flow cytometry analysis of MDMs (F), (CD86+) M1, and (CD206+) M2 macrophages (G) in livers of PBS-Lip– or Clod-Lip–treated Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. M1 macrophages were defined as Gr1+CD11b+F4/80+CD86+; M2 macrophages were defined as Gr1+CD11b+ F4/80+CD206+ populations. (G and H) IF (scale bar, 400 μm) of M1 MDMs (CD86) (G) and M2 MDMs (CD206) (H) in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. Blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, green: anti-CD86/CD163, and yellow: anti-Ly6c. (I) Treatment schedule of PBS-Lip or Clod-Lip in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. (J) H&E staining of liver tissues treated with PBS-Lip or Clod-Lip in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. (K) Statistical analysis of DEGs in the comparison of Tet2WT versus Tet2ΔMye mice and Tet2WT-CCl4 versus Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. A twofold decrease or increase in gene expression was considered statistically significant between different groups (Tet2WT, n = 4; Tet2ΔMye, n = 4; Tet2WT-CCl4, n = 5; Tet2ΔMye-CCl4, n = 5). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (B, D, G, and F). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (D). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Expansion advantage of transplanted Tet2 −/− CD45.2 + CD11b + cells and change of immune cells after Clod-Lip treatment in Tet2 WT -CCl 4 and Tet2 ΔMye -CCl 4 mice. (A) Strategy for flow cytometric analysis of the proportion of CD45.2+ cells in the blood and liver of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice. (B) Representative graphs of CD45.2+ cells in peripheral blood and liver of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice. (C) Flow cytometry strategy and statistical analysis of CD45.2+ F4/80+ cell frequency in livers of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4). (D) Flow cytometry strategy for MDMs frequency in liver tissue of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice. (E and F) Strategy for flow cytometry analysis of MDMs (F), (CD86+) M1, and (CD206+) M2 macrophages (G) in livers of PBS-Lip– or Clod-Lip–treated Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. M1 macrophages were defined as Gr1+CD11b+F4/80+CD86+; M2 macrophages were defined as Gr1+CD11b+ F4/80+CD206+ populations. (G and H) IF (scale bar, 400 μm) of M1 MDMs (CD86) (G) and M2 MDMs (CD206) (H) in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. Blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, green: anti-CD86/CD163, and yellow: anti-Ly6c. (I) Treatment schedule of PBS-Lip or Clod-Lip in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. (J) H&E staining of liver tissues treated with PBS-Lip or Clod-Lip in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. (K) Statistical analysis of DEGs in the comparison of Tet2WT versus Tet2ΔMye mice and Tet2WT-CCl4 versus Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. A twofold decrease or increase in gene expression was considered statistically significant between different groups (Tet2WT, n = 4; Tet2ΔMye, n = 4; Tet2WT-CCl4, n = 5; Tet2ΔMye-CCl4, n = 5). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (B, D, G, and F). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (D). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

MDMs depletion attenuates liver fibrosis in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice

In line with the expansion of Tet2−/−pMDMs in chimeric mice, immunofluorescence (IF) analysis revealed significantly greater intrahepatic MDMs accumulation in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice compared with Tet2WT-CCl4 littermates (Fig. 3, A and B). Flow cytometry and IF analysis further demonstrated an elevated frequency of M1-like pMDMs and a reduced proportion of M2-like MDMs in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (Fig. 3, C and D; and Fig. S2, F–H).

MDMs depletion effectively inhibits liver fibrosis progression in Tet2 ΔMye mice. (A and B) IF assay (A) (scale bar, 400 μm) and statistical analysis (B) of MDMs infiltration in livers of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice. Blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, and green: anti-Ly6c (n = 4 for each group). (C and D) Frequency of CD86+ MDMs (M1) (C) and CD206+ MDMs (M2) (D) evaluated by flow cytometry in livers of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for each group). (E and F) Representative flow cytometry graphs (E) and statistical analysis (F) the of MDMs frequency in Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after treatment with PBS-Lip or Clod-Lip (n = 3 for each group). (G–I) Picrosirius red staining (G and H) (scale bar, 125 μm) and Ishak score (I) in livers of PBS-Lip– and Clod-Lip–treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice with liver fibrosis. (J–L) IHC staining (J) and statistical analysis of α-SMA (K) and collagen I (L) expression in livers (scale bar, 100 μm) of PBS-Lip– and Clod-Lip–treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 3 for each group). (M and N) Changes in serum Col IV (M) and HA (N) in CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after PBS-Lip or Clod-Lip treatment (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–N). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (B–D, F, H, I, and K–N). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

MDMs depletion effectively inhibits liver fibrosis progression in Tet2 ΔMye mice. (A and B) IF assay (A) (scale bar, 400 μm) and statistical analysis (B) of MDMs infiltration in livers of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice. Blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, and green: anti-Ly6c (n = 4 for each group). (C and D) Frequency of CD86+ MDMs (M1) (C) and CD206+ MDMs (M2) (D) evaluated by flow cytometry in livers of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for each group). (E and F) Representative flow cytometry graphs (E) and statistical analysis (F) the of MDMs frequency in Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after treatment with PBS-Lip or Clod-Lip (n = 3 for each group). (G–I) Picrosirius red staining (G and H) (scale bar, 125 μm) and Ishak score (I) in livers of PBS-Lip– and Clod-Lip–treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice with liver fibrosis. (J–L) IHC staining (J) and statistical analysis of α-SMA (K) and collagen I (L) expression in livers (scale bar, 100 μm) of PBS-Lip– and Clod-Lip–treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 3 for each group). (M and N) Changes in serum Col IV (M) and HA (N) in CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after PBS-Lip or Clod-Lip treatment (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–N). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (B–D, F, H, I, and K–N). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

To explore whether intrahepatic pMDMs expansion was the trigger of liver fibrosis progression in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice, we administered clodronate liposomes (Clod-Lip) to deplete MDMs in vivo, with PBS liposomes (PBS-Lip) serving as a control (Fig. S2 I). Clod-Lip treatment effectively reduced the MDMs population (Fig. 3, E and F) and significantly attenuated collagen deposition, as evidenced by Picrosirius red staining and Ishak scoring (Fig. 3, G–I). Immune cell infiltration was markedly reduced in Clod-Lip–treated Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice, reaching levels comparable with those in Tet2WT-CCl4 controls (Fig. S2 J). Furthermore, Clod-Lip treatment normalized the expression of fibrotic markers, including α-SMA and collagen I (Fig. 3, J–L), and reduced serum levels of Col IV (Fig. 3 M) and HA (Fig. 3 N) in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. In conclusion, depletion of MDMs effectively ameliorates liver fibrosis in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice, underscoring the critical role of intrahepatic pMDMs in driving liver fibrosis progression.

Tet2ΔMye may drive MDMs infiltration via autonomous Ccl2 and Ccl8 production

To identify factors regulating MDMs intrahepatic infiltration in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice, we performed RNA sequencing of liver tissues. Gene expression analysis revealed 130 and 134 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Tet2WT vs. Tet2ΔMye and Tet2WT-CCl4 vs. Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 comparisons, respectively (Fig. S2 K). Because of the significant difference of liver fibrosis severity between Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice, we next focused on DEGs between the two groups. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) highlighted significant enrichment of pathways related to “cytokine production involved in immune response” and “cytokine production involved in inflammatory response” in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (Fig. 4 A). KEGG analysis further confirmed the enrichment of “cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction” and “chemokine signaling pathway” (Fig. 4 B). Among chemokine (C–C motif) ligands, Ccl2 and Ccl8 were the most upregulated in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (Fig. 4 C), a finding validated using RT-PCR (Fig. S3, A and B). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) showed elevated levels of Ccl2 and Ccl8 in both serum and liver tissues of Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice in comparison with Tet2WT-CCl4 and control groups (Fig. 4, D–G). Similarly, we detected increased Ccl2 and Ccl8 in the serum of the KO-MT chimeric mice compared with WT-MT mice (Fig. 4, H and I).

The upregulated Ccl2 and Ccl8 secreted by Tet2 −/− MDMs promote MDMs intrahepatic accumulation in a positive feedback manner. (A) GSEA for cytokine production involved in immune response and cytokine production involved in inflammatory response signaling pathways in Tet2WT-CCl4 versus Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4–5 for each group). (B) KEGG analysis of DEGs in Tet2WT-CCl4 versus Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates. (C) Expression profiles of C–C motif ligands detected by RNA sequence in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 5 for each group). (D and E) The effect of Tet2ΔMye on Ccl2 levels in serum (D) and livers (E) of mice with or without liver fibrosis. pg/mg: Ccl2 levels per milligram of liver tissue (n = 4 for each group). (F and G) The Ccl8 levels in serum (F) and livers (G) of four groups of mice. pg/mg: Ccl8 levels per milligram of liver tissue (n = 4 for each group). (H and I) Changes in Ccl2 (H) and Ccl8 (I) levels in serum of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (K) Detection of Ccl2 and Ccl8 expression in Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− MDMs by flow cytometry (n = 5 for each group) and RT-PCR (n = 8 for each group). Data are the accumulative results from at least two independent experiments (K) or are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (D–J). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (B–G, J, and K) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (H and I). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

The upregulated Ccl2 and Ccl8 secreted by Tet2 −/− MDMs promote MDMs intrahepatic accumulation in a positive feedback manner. (A) GSEA for cytokine production involved in immune response and cytokine production involved in inflammatory response signaling pathways in Tet2WT-CCl4 versus Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4–5 for each group). (B) KEGG analysis of DEGs in Tet2WT-CCl4 versus Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates. (C) Expression profiles of C–C motif ligands detected by RNA sequence in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 5 for each group). (D and E) The effect of Tet2ΔMye on Ccl2 levels in serum (D) and livers (E) of mice with or without liver fibrosis. pg/mg: Ccl2 levels per milligram of liver tissue (n = 4 for each group). (F and G) The Ccl8 levels in serum (F) and livers (G) of four groups of mice. pg/mg: Ccl8 levels per milligram of liver tissue (n = 4 for each group). (H and I) Changes in Ccl2 (H) and Ccl8 (I) levels in serum of scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (K) Detection of Ccl2 and Ccl8 expression in Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− MDMs by flow cytometry (n = 5 for each group) and RT-PCR (n = 8 for each group). Data are the accumulative results from at least two independent experiments (K) or are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (D–J). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (B–G, J, and K) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (H and I). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Expression of Ccl2 and Ccl8 in Tet2 WT -CCl 4 and Tet2 ΔMye -CCl 4 mice and the effect of CCL2 and CCL8 inhibition on liver fibrosis progression. (A and B) Changes in (A) Ccl2 and (B) Ccl8 mRNA levels detected by RT-PCR in liver tissues of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (Tet2WT, n = 4; Tet2ΔMye, n = 4; Tet2WT-CCl4, n = 5; Tet2ΔMye-CCl4, n = 5). (C–F) Detection of CCL2 and CCL8 level in Tet2+/+and Tet2−/− monocytes (C and D), granulocytes (E), and DCs (F) (n = 5 for each group). (G) Treatment schedule of Bindarit or PBS for Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. (H) Immune cell infiltration and the pathological structure of livers were evaluated by H&E staining for PBS and Bindarit in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 3). Green arrows indicate infiltrated immune cells in liver tissues. Scale bar, 100 μm. (I and J) mRNA levels of Col1a1 (I) and Acta2 (J) in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice treated with PBS or Bindarit (n = 3 for each group). (K and L) Changes in serum ALT (K) and AST (L) after Bindarit treatment in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). (M) Representative flow cytometry graphs of MDMs in liver tissues of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice treated with PBS or Bindarit. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–F and I–L). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, paired Student’s t test (C–F) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (A, B, and I–L). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Expression of Ccl2 and Ccl8 in Tet2 WT -CCl 4 and Tet2 ΔMye -CCl 4 mice and the effect of CCL2 and CCL8 inhibition on liver fibrosis progression. (A and B) Changes in (A) Ccl2 and (B) Ccl8 mRNA levels detected by RT-PCR in liver tissues of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (Tet2WT, n = 4; Tet2ΔMye, n = 4; Tet2WT-CCl4, n = 5; Tet2ΔMye-CCl4, n = 5). (C–F) Detection of CCL2 and CCL8 level in Tet2+/+and Tet2−/− monocytes (C and D), granulocytes (E), and DCs (F) (n = 5 for each group). (G) Treatment schedule of Bindarit or PBS for Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. (H) Immune cell infiltration and the pathological structure of livers were evaluated by H&E staining for PBS and Bindarit in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 3). Green arrows indicate infiltrated immune cells in liver tissues. Scale bar, 100 μm. (I and J) mRNA levels of Col1a1 (I) and Acta2 (J) in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice treated with PBS or Bindarit (n = 3 for each group). (K and L) Changes in serum ALT (K) and AST (L) after Bindarit treatment in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). (M) Representative flow cytometry graphs of MDMs in liver tissues of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice treated with PBS or Bindarit. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–F and I–L). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, paired Student’s t test (C–F) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (A, B, and I–L). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Given the pivotal role of Ccl2 and Ccl8 in monocyte recruitment and MDMs accumulation, we sought to identify their cellular origins. ELISA and flow cytometry analysis revealed that CD45.2+Tet2−/− monocytes, granulocytes, and dendritic cells exhibited similar Ccl2 and Ccl8 levels to Tet2+/+ counterparts (Fig. S3, C–F). In contrast, intrahepatic CD45.2+Tet2−/− MDMs showed significantly higher Ccl2 and Ccl8 expression than that of Tet2+/+ MDMs (Fig. 4 J), indicating that Tet2−/− MDMs are the primary source of these chemokines. Consistent with this, RT–quantitative PCR (qPCR) confirmed elevated Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA levels in Tet2−/− MDMs isolated from Tet2ΔMye mice compared with littermate controls (Fig. 4 K).

Inhibition of Ccl2 and Ccl8 depletes MDMs and improves liver fibrosis in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice

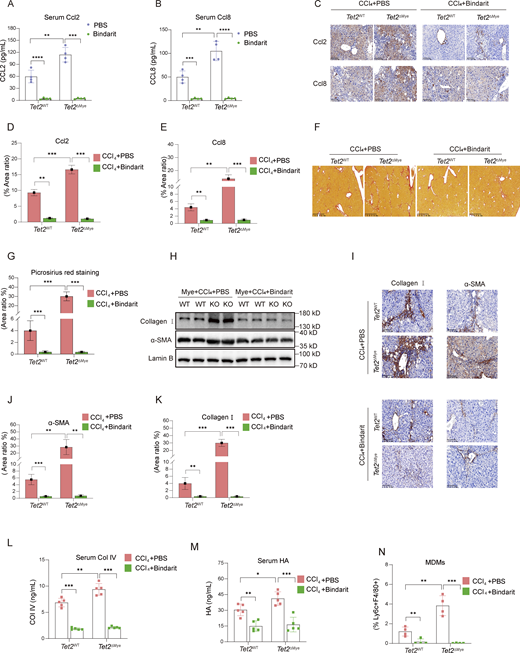

To investigate the role of Ccl2 and Ccl8 in pMDMs intrahepatic infiltration and liver fibrosis progression, we treated mice with Bindarit, a dual inhibitor of Ccl2 and Ccl8, during the construction of liver fibrosis model in Tet2ΔMye mice (Fig. S3 G). Bindarit treatment significantly reduced Ccl2 and Ccl8 levels in both serum and liver tissues of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (Fig. 5, A–E). Picrosirius red staining revealed that Bindarit treatment markedly decreased collagen deposition, Ishak scores, and immune cell infiltration in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice to levels comparable with those in Tet2WT-CCl4 mice (Fig. 5, F–H; and Fig. S3 H). Furthermore, Bindarit suppressed the expression of α-SMA and collagen I at both protein and mRNA levels in the liver (Fig. 5, I–K; and Fig. S3, I and J) and normalized serum levels of Col IV (Fig. 5 L), HA (Fig. 5 M), ALT (Fig. S3 K), and AST (Fig. S3 L) in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. Notably, Bindarit treatment also significantly reduced intrahepatic MDMs accumulation (Fig. 5 N and Fig. S3 M). Inhibition of Ccl2 and Ccl8 by Bindarit effectively suppresses MDMs intrahepatic infiltration and ameliorates liver fibrosis in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice, highlighting the critical role of these chemokines in fibrotic progression.

Inhibition of Ccl2 and Ccl8 depletes MDMs and alleviates liver fibrosis in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4mice. (A and B) Effect of Bindarit inhibition on serum Ccl2 (A) and Ccl8 (B) levels in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4 for each group). (C–E) IHC staining (C) and statistical analysis of Ccl2 (D) and Ccl8 (E) expression after Bindarit treatment in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4 for each group). Scale bar, 100 μm. (F and G) Picrosirius red staining (F) and statistical analysis (G) of collagen deposition in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4 for each group). Scale bar, 100 μm. (H–K) Effect of Bindarit on α-SMA and collagen I expression evaluated by western blot (H) and IHC staining (I, J, and K) (scale bar, 100 μm) in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4 for each group). (L and M) Changes in serum Col IV (M) and HA (N) in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates after PBS or Bindarit treatment (n = 5 for each group). (N) Changes in intrahepatic MDMs frequency after Bindarit treatment in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–L). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (A, B, D, E, G, and J–N). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Inhibition of Ccl2 and Ccl8 depletes MDMs and alleviates liver fibrosis in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4mice. (A and B) Effect of Bindarit inhibition on serum Ccl2 (A) and Ccl8 (B) levels in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4 for each group). (C–E) IHC staining (C) and statistical analysis of Ccl2 (D) and Ccl8 (E) expression after Bindarit treatment in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4 for each group). Scale bar, 100 μm. (F and G) Picrosirius red staining (F) and statistical analysis (G) of collagen deposition in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4 for each group). Scale bar, 100 μm. (H–K) Effect of Bindarit on α-SMA and collagen I expression evaluated by western blot (H) and IHC staining (I, J, and K) (scale bar, 100 μm) in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates (n = 4 for each group). (L and M) Changes in serum Col IV (M) and HA (N) in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates after PBS or Bindarit treatment (n = 5 for each group). (N) Changes in intrahepatic MDMs frequency after Bindarit treatment in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 littermates. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–L). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (A, B, D, E, G, and J–N). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Ccl2/Ccl8-dependent Ccr2/Ccr3 activation promotes Tet2−/− monocyte recruitment and pMDMs hepatic accumulation

Since MDMs were often originated from peripheral monocytes via chemokines signaling, we, therefore, hypothesized that Tet2−/−monocytes might exhibit superior capability to infiltrate into liver. Given the upregulation of Ccl2 and Ccl8, we firstly detected the expression of Ccr2 and Ccr3, the receptors of Ccl2 and Ccl8, on Tet2−/− monocytes. Flow cytometric analysis revealed cell-autonomous upregulation of Ccr2 and Ccr3 in Tet2−/− monocytes, with significant increases in both surface density and population frequency compared with Tet2+/+ counterparts (Fig. 6, A and B). Notably, we identified a pre-fibrotic phenotype in Tet2−/− monocytes, characterized by baseline elevation of Ccr2+/Ccr3+ subpopulations, a phenotype that was substantially amplified following CCl4 challenge (Fig. 6 B). Notably, Ccr2 and Ccr3 expression was nearly undetectable in pMDMs compared with that in monocytes (Fig. S4, A and B). Therapeutic co-blockade of Ccr2/Ccr3 decreased the frequency of pMDMs in the liver of Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (Fig. 6, C–E). IF staining identified the decreased Inos+ activated MDMs in liver (Fig. 6, F and G). Anti-Ccr2/Ccr3 effectively inhibited collagen deposition (Fig. 6 H), concomitant with suppressed Acta2 and Col1a1 expression (Fig. 6, I and J). To determine the cellular specificity of Ccl2- and Ccl8-dependent recruitment, we performed comprehensive flow cytometric profiling of Ccr2/Ccr3-expressing immune populations in fibrotic livers. Tet2-deficient livers showed no significant differences in hepatic infiltration frequencies of CD3+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, NK cells, or neutrophils compared with WT controls (Fig. S4 C). These data reveal a remarkable cellular selectivity, where Tet2 deletion specifically enhances pMDMs recruitment without broadly affecting other Ccr2+ and Ccr3+ immune subsets. Collectively, Tet2 deficiency primes monocytes for hyperresponsiveness to chemokine signaling through Ccr2/Ccr3 upregulation, which critically mediates the progression of fibrosis.

Ccl2/Ccl8-dependent Ccr2/Ccr3 activation drives Tet2 −/− monocyte recruitment and pMDMs accumulation in liver. (A) Expression of Ccr2 and Ccr3 on Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− monocytes isolated from Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for each group). (B) Frequency of Ccr2+ and Ccr3+ monocytes in oil- and CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for each group). (C) Effect of anti-Ccr2/3 treatment on the frequency of pMDMs in CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye (n = 4 for each group). (D and E) CD86+ MDMs distribution (D) and statistical analysis (E) evaluated by IF staining after anti-Ccr2/3 Ab treatment (n = 4 for each group). Blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, green: anti-Ly6c, and yellow: anti-CD206. Scale bar: 400 μm. (F and G) The distribution of Inos+ MDMs (activated MDMs) (F) and statistical analysis (G) after anti-Ccr2/3 Ab treatment (n = 4 for each group). Blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, green: anti-Ly6c, and yellow: anti-Inos. Scale bar: 400 μm. (H) Change of collagen deposition evaluated by Picrosirius red staining in livers of IgG and anti-Ccr2/3–treated Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). (I and J) mRNA levels of Acta2 (I) and Col1a1 (J) in liver tissues of IgG and anti-Ccr2/3–treated Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–J). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (B, C, E, G, I, and J). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Ccl2/Ccl8-dependent Ccr2/Ccr3 activation drives Tet2 −/− monocyte recruitment and pMDMs accumulation in liver. (A) Expression of Ccr2 and Ccr3 on Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− monocytes isolated from Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for each group). (B) Frequency of Ccr2+ and Ccr3+ monocytes in oil- and CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for each group). (C) Effect of anti-Ccr2/3 treatment on the frequency of pMDMs in CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye (n = 4 for each group). (D and E) CD86+ MDMs distribution (D) and statistical analysis (E) evaluated by IF staining after anti-Ccr2/3 Ab treatment (n = 4 for each group). Blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, green: anti-Ly6c, and yellow: anti-CD206. Scale bar: 400 μm. (F and G) The distribution of Inos+ MDMs (activated MDMs) (F) and statistical analysis (G) after anti-Ccr2/3 Ab treatment (n = 4 for each group). Blue: DAPI, red: anti-F4/80, green: anti-Ly6c, and yellow: anti-Inos. Scale bar: 400 μm. (H) Change of collagen deposition evaluated by Picrosirius red staining in livers of IgG and anti-Ccr2/3–treated Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). (I and J) mRNA levels of Acta2 (I) and Col1a1 (J) in liver tissues of IgG and anti-Ccr2/3–treated Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–J). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (B, C, E, G, I, and J). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Effect of Tet2 deficiency on Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA stability and IL-6 neutralization on liver fibrosis progression. (A) The frequency of Ccr2+ and Ccr3+ pMDMs in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). (B) Expression of Ccr2 and Ccr3 on monocytes, Tet2+/+ pMDMs, and Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 4 for each group). (C) The infiltration difference of other Ccr2 or Ccr3 expressing cell types in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). (D) GAPDH mRNA decay curve in Tet2+/+ pMDMs and Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 6 for each group). (E) Transcriptional level of Elavl1, Znf36, and Ybx1 in Tet2+/+ pMDMs and Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 4 for each group). (F–I) Serum levels of (F) IL-1α, (G) IL-2, (H) TNFα, and (I) IL-1β in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 5 for each group). (J) Serum IL-6 levels in scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (K) Il-6 levels in CD45.2+ pMDMs isolated from livers of WT-MT and KO-MT mice (n = 4). (L) mRNA levels of Acta2 and Col1a1 in Tet2+/+and Tet2−/− HSCs (n = 4 for each group). (M and N) Effect of anti–IL-6 Abs treatment on mRNA levels of Col1a1 (M) and Acta2 (N) in Tet2+/+and Tet2−/− HSCs co-cultured with Tet2+/+or Tet2−/− MDMs detected by RT-PCR in vitro (n = 3 for each group). (O) Effect on recombinant Ccl2 and Ccl8 on Il-6 expression in Tet2+/+ pMDMs and Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 3 for each group). (P) Detection of MDMs in livers by flow cytometry after Bindarit or IL-6 Abs treatment for 2 wk (n = 5 for each group). (Q) H&E staining of liver tissues treated with PBS, Bindarit, IL-6 Abs, or Bindarit plus IL-6 Abs in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–P). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (A, C, D, E, K, L, and O) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B and J) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (F–I, M, and N). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Effect of Tet2 deficiency on Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA stability and IL-6 neutralization on liver fibrosis progression. (A) The frequency of Ccr2+ and Ccr3+ pMDMs in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). (B) Expression of Ccr2 and Ccr3 on monocytes, Tet2+/+ pMDMs, and Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 4 for each group). (C) The infiltration difference of other Ccr2 or Ccr3 expressing cell types in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). (D) GAPDH mRNA decay curve in Tet2+/+ pMDMs and Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 6 for each group). (E) Transcriptional level of Elavl1, Znf36, and Ybx1 in Tet2+/+ pMDMs and Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 4 for each group). (F–I) Serum levels of (F) IL-1α, (G) IL-2, (H) TNFα, and (I) IL-1β in livers of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 5 for each group). (J) Serum IL-6 levels in scramble, WT-MT, and KO-MT mice (n = 4 for each group). (K) Il-6 levels in CD45.2+ pMDMs isolated from livers of WT-MT and KO-MT mice (n = 4). (L) mRNA levels of Acta2 and Col1a1 in Tet2+/+and Tet2−/− HSCs (n = 4 for each group). (M and N) Effect of anti–IL-6 Abs treatment on mRNA levels of Col1a1 (M) and Acta2 (N) in Tet2+/+and Tet2−/− HSCs co-cultured with Tet2+/+or Tet2−/− MDMs detected by RT-PCR in vitro (n = 3 for each group). (O) Effect on recombinant Ccl2 and Ccl8 on Il-6 expression in Tet2+/+ pMDMs and Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 3 for each group). (P) Detection of MDMs in livers by flow cytometry after Bindarit or IL-6 Abs treatment for 2 wk (n = 5 for each group). (Q) H&E staining of liver tissues treated with PBS, Bindarit, IL-6 Abs, or Bindarit plus IL-6 Abs in Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–P). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (A, C, D, E, K, L, and O) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (B and J) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (F–I, M, and N). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Tet2 deficiency enhances Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA stability by modifying 5-hydroxymethylcytosine–dependent RNA–protein interactions

As a 5-methylcytosine (5mC) “eraser,” Tet2 regulates mRNA stability by modulating AU-rich element (ARE)-mediated protein binding, while zinc finger protein 36 (Zfp36) promotes ARE-containing mRNA decay. Bioinformatics analysis of 3′ UTR sequences revealed that both Ccl2 and Ccl8 harbor ARE motifs (Table S6). We determined that Tet2 deficiency significantly enhances the stability of Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA (Fig. 7, A and B), but not Gapdh mRNA (Fig. S4 D), which may represent the molecular mechanism underlying the upregulation of Ccl2 and Ccl8 in pMDMs as well as the elevated levels of Ccl2 and Ccl8 observed in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. We therefore hypothesized that Tet2 deficiency modulates the binding affinity of Y-box–binding protein 1 (Ybx1), Elavl1, and Zfp36 to Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNAs by altering the methylation status of ARE regions in their 3′ UTRs, consequently influencing mRNA stability. We found that Tet2 depletion did not alter the transcriptional levels of Ybx1, Elavl1, or Zfp36 in THP1-derived pMDMs (Fig. S4 E). However, the oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) in Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNAs exerts bidirectional regulation on RNA–protein interactions: 5hmC modification significantly enhanced binding affinity of the stabilizing factors Ybx1 and Elavl1, while potently inhibiting recruitment of the decay-promoting factor Zfp36 (Fig. 7 C). To further assess the functional consequences of Tet2 deficiency on these regulatory interactions, we performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)-qPCR in bone marrow cell (BMC)-derived pMDMs. Compared with WT controls, Tet2−/− pMDMs exhibited substantially increased association of Ybx1 and Elavl1 with Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNAs, while showing markedly reduced Zfp36 binding (Fig. 7 D). Consistent with those RNA-binding proteins binding shift, enzymatic inactivation of Tet2 via catalytic domain mutation led to pronounced stabilization of Ccl2 and Ccl8 transcripts (Fig. 7, E and F). Our findings demonstrate that Tet2 regulates the stability of Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNAs in an enzyme activity-dependent manner by modulating the methylation landscape of ARE motifs in their 3′ UTRs.

Tet2 deficiency enhances Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA stability by modifying 5hmC-dependent RNA–protein interactions. (A and B)Ccl2 (A) and Ccl8 (B) mRNA decay in Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− MDMs (n = 6 for each group). (C)Tet2-mediated oxidation of Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA 5mC disrupts its binding with Ybx1, Elavl1, and Zfp36. Pull-down assay was performed by incubating C, 5mC, and 5hmC oligos of Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA with cell lysate from THP1-derived pMDMs (n = 3 for each group). (D) Effect of Tet2 deficiency on the binding enrichment of Ybx1, Elavl1, and Zfp36 at 3′UTR of Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA. Tet2-binding sites were mapped in the mRNA of Ccl2 and Ccl8 by qPCR of Ybx1, Elavl1, and Zfp36 RIP product in THP1-derived pMDMs (n = 3 for each group). (E and F) Effect of enzymatic inactivation of Tet2 via catalytic domain mutation on stabilization of Ccl2 (F) and Ccl8 (G) transcripts (n = 4 for each group). Data are the accumulative results from at least two independent experiments (A, B, D, E, and F) or are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (C and D). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (A, B, and D–F). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Tet2 deficiency enhances Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA stability by modifying 5hmC-dependent RNA–protein interactions. (A and B)Ccl2 (A) and Ccl8 (B) mRNA decay in Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− MDMs (n = 6 for each group). (C)Tet2-mediated oxidation of Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA 5mC disrupts its binding with Ybx1, Elavl1, and Zfp36. Pull-down assay was performed by incubating C, 5mC, and 5hmC oligos of Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA with cell lysate from THP1-derived pMDMs (n = 3 for each group). (D) Effect of Tet2 deficiency on the binding enrichment of Ybx1, Elavl1, and Zfp36 at 3′UTR of Ccl2 and Ccl8 mRNA. Tet2-binding sites were mapped in the mRNA of Ccl2 and Ccl8 by qPCR of Ybx1, Elavl1, and Zfp36 RIP product in THP1-derived pMDMs (n = 3 for each group). (E and F) Effect of enzymatic inactivation of Tet2 via catalytic domain mutation on stabilization of Ccl2 (F) and Ccl8 (G) transcripts (n = 4 for each group). Data are the accumulative results from at least two independent experiments (A, B, D, E, and F) or are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (C and D). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (A, B, and D–F). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Upregulated IL-6 secreted by Tet2−/− pMDMs activates HSCs in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 Mice

Because of the significant intrahepatic expansion of pMDMs in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice, we assessed the levels of key inflammatory cytokines secreted by pMDMs to promote liver fibrosis progression. ELISA analysis revealed that IL-6 was the most markedly elevated cytokine in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice compared with IL-1α, IL-2, and TNFα, whereas IL-1β levels remained unchanged (Fig. 8, A and B; and Fig. S4, F–I). Consistent with this, WT-MT chimeric mice also exhibited higher serum IL-6 levels than those KO-MT mice (Fig. S4 J), indicating that Tet2−/− myeloid cells may be the primary source of elevated IL-6. Furthermore, we showed that Tet2−/− pMDMs produced higher levels of IL-6 than Tet2−/− pMDMs (Fig. S4 K).

The upregulating IL-6 secreted by Tet2−/−pMDMs activated HSCs in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4mice. (A) Effect of Tet2ΔMye on serum IL-6 levels evaluated by ELISA in oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for each group). (B) Effect of Tet2ΔMye on Il-6 mRNA levels in livers of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for oil-treated groups, n = 5 for CCl4-treated groups). (C) Experimental design of co-culture between Tet2+/+ or Tet2−/− HSCs and Tet2+/+ or Tet2−/− pMDMs. Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− pMDMs were isolated from livers of CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice. Naïve Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− HSCs were isolated from oil-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice. (D) Detection of IL-6 in the supernatant after co-culture by ELISA (n = 3 for each group). (E–G) mRNA and protein levels of Acta2 (E and G) and Col1a1 (F and G) detected by RT-PCR in Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− HSCs co-cultured with Tet2+/+ or Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 3 for each group). (H and I) Picrosirius red staining (H) (scale bar, 125 μm) and statistical analysis (I) of livers of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after Bindarit plus anti-IL-6 Abs treatment (n = 4 for each group). (J and K) Changes in serum ALT (J) and AST (K) levels in CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after treatment with Bindarit, anti–IL-6 Abs, or Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–K). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (A, B, D–F, and I–K). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F8.

The upregulating IL-6 secreted by Tet2−/−pMDMs activated HSCs in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4mice. (A) Effect of Tet2ΔMye on serum IL-6 levels evaluated by ELISA in oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for each group). (B) Effect of Tet2ΔMye on Il-6 mRNA levels in livers of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 4 for oil-treated groups, n = 5 for CCl4-treated groups). (C) Experimental design of co-culture between Tet2+/+ or Tet2−/− HSCs and Tet2+/+ or Tet2−/− pMDMs. Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− pMDMs were isolated from livers of CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice. Naïve Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− HSCs were isolated from oil-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice. (D) Detection of IL-6 in the supernatant after co-culture by ELISA (n = 3 for each group). (E–G) mRNA and protein levels of Acta2 (E and G) and Col1a1 (F and G) detected by RT-PCR in Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− HSCs co-cultured with Tet2+/+ or Tet2−/− pMDMs (n = 3 for each group). (H and I) Picrosirius red staining (H) (scale bar, 125 μm) and statistical analysis (I) of livers of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after Bindarit plus anti-IL-6 Abs treatment (n = 4 for each group). (J and K) Changes in serum ALT (J) and AST (K) levels in CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after treatment with Bindarit, anti–IL-6 Abs, or Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs (n = 4 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–K). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (A, B, D–F, and I–K). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F8.

To determine whether Tet2−/− pMDMs activate HSCs through IL-6, we established an in vitro co-culture system of intrahepatic MDMs and HSCs (Fig. 8 C). Tet2+/+ and Tet2−/− MDMs were isolated from CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice, whereas HSCs were isolated from oil-treated WT mice to exclude confounding effects of Tet2 deficiency or CCl4 treatment on HSCs properties. Notably, Tet2 deficiency did not significantly affect HSCs activation (Fig. S4 L). In co-culture, Tet2−/− MDMs secreted higher levels of IL-6 than Tet2−/− MDMs (Fig. 8 D), and only HSCs co-cultured with Tet2−/− pMDMs exhibited increased expression of α-SMA and Col1a1, indicating HSCs activation (Fig. 8, E–G). Furthermore, IL-6 neutralization using anti–IL-6 antibodies (Abs) significantly reduced α-SMA and Col1a1 expression in HSCs co-cultured with Tet2−/− pMDMs (Fig. S4, M and N), confirming the role of Il-6 in HSCs activation. To investigate whether elevated intrahepatic Ccl2 and Ccl8 regulates IL-6 expression in pMDMs, we treated pMDMs isolated from Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice with recombinant Ccl2 and Ccl8. The results showed that neither chemokine significantly altered IL-6 expression in pMDMs (Fig. S4 O).

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of IL-6 blockade, we administered anti-mouse IL-6 Abs to Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice. Although IL-6 neutralization alone modestly reduced collagen deposition (Fig. 8, H and I) and serum AST (Fig. 8 J) and ALT (Fig. 8 K) levels, it was less effective than Bindarit treatment. Notably, IL-6 Abs did not significantly reduce pMDMs frequency in the liver compared with Bindarit treatment (Fig. S4 P). However, combining Bindarit with IL-6 Abs more effectively attenuated collagen deposition, serum AST and ALT levels, and immune cell infiltration compared with either treatment alone (Fig. 8, H–K; and Fig. S4 Q). Therefore, Tet2−/− pMDMs secrete elevated IL-6, which promotes HSCs activation and contributes to liver fibrosis. Combining MDMs depletion with IL-6 blockade represents a more effective therapeutic strategy for mitigating fibrosis in Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice.

Tet2ΔMye-induced myeloid hematopoiesis in aging host accelerates liver fibrosis

TET2 mutations, frequently observed in myeloid cells of the elderly, drive myeloid expansion. To investigate whether Tet2ΔMye in aging hosts exacerbates liver fibrosis through the Ccl2/Ccl8–pMDMs–HSCs axis, we established a competitive bone marrow transplantation (BMT) model using Tet2-deficient BMCs (Fig. 9 A). CD45.1+Tet2−/− BMCs (80%) and CD45.2+Tet2ΔMye BMCs (20%) were transplanted into lethally irradiated young (young-BMT) and old (old-BMT) CD45.1 mice. By 6 wk after transplantation, CD45.2+ cells constituted ∼50% of peripheral blood leukocytes in both groups (Fig. 9 B). CD45.2+Tet2−/− leukocytes, Ly6chigh monocytes, and neutrophils exhibited significant expansion, with greater expansion in old-BMT mice than in young-BMT mice (Fig. 9 C), recapitulating myeloid hematopoiesis observed in elderly individuals with TET2 mutations.

Tet2 ΔMye -induced myeloid hematopoiesis in aging mice accelerate liver fibrosis. (A) A chimeric mouse model of Tet2ΔMye-induced myeloid hematopoiesis was constructed in young and aged mice. CCl4 was administered to induce liver fibrosis in young-BMT and old-BMT mice. (B) The profiles the reconstruction of CD45.2+Tet2−/− BMCs in the peripheral blood of young-BMT and old-BMT mice (n = 4 for each group). (C and D) Blood cell composition of CD45.2+ cells in young-BMT and old-BMT mice with (C) or without (D) CCl4-induced liver fibrosis (n = 4 for each group). (E) Frequency of pMDMs in livers of young-BMT and old-BMT mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis (n = 4 for each group). (F) The serum levels of Ccl2, Ccl8, and IL-6 in young-BMT and old-BMT mice with liver fibrosis (n = 4 for each group). (G and H) Picrosirius red staining (G) (scale bar, 125 μm) and statistical analysis (H) of collagen deposition in livers of CCl4-treated young-BMT and old-BMT mice after Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs treatment (n = 4 for each group). (I and J) Changes in serum Col IV (I) and HA (J) levels in young-BMT and old-BMT mice treated with Bindarit, anti–IL-6 Abs, or Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–J). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (C–F), or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (H–J). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Tet2 ΔMye -induced myeloid hematopoiesis in aging mice accelerate liver fibrosis. (A) A chimeric mouse model of Tet2ΔMye-induced myeloid hematopoiesis was constructed in young and aged mice. CCl4 was administered to induce liver fibrosis in young-BMT and old-BMT mice. (B) The profiles the reconstruction of CD45.2+Tet2−/− BMCs in the peripheral blood of young-BMT and old-BMT mice (n = 4 for each group). (C and D) Blood cell composition of CD45.2+ cells in young-BMT and old-BMT mice with (C) or without (D) CCl4-induced liver fibrosis (n = 4 for each group). (E) Frequency of pMDMs in livers of young-BMT and old-BMT mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis (n = 4 for each group). (F) The serum levels of Ccl2, Ccl8, and IL-6 in young-BMT and old-BMT mice with liver fibrosis (n = 4 for each group). (G and H) Picrosirius red staining (G) (scale bar, 125 μm) and statistical analysis (H) of collagen deposition in livers of CCl4-treated young-BMT and old-BMT mice after Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs treatment (n = 4 for each group). (I and J) Changes in serum Col IV (I) and HA (J) levels in young-BMT and old-BMT mice treated with Bindarit, anti–IL-6 Abs, or Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (A–J). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (C–F), or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (H–J). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

To evaluate whether Tet2ΔMye-induced myeloid hematopoiesis increased the risk of liver fibrosis in old-BMT mice, young-BMT and old-BMT mice were subjected to CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Old-BMT mice displayed higher levels of Tet2−/− Ly6chigh monocytes (Fig. 9 D); intrahepatic pMDMs (Fig. 9 E); and serum Ccl2, Ccl8, and IL-6 (Fig. 9 F) compared with young-BMT mice. Combined treatment with Bindarit and IL-6 Abs effectively attenuated fibrosis, reducing collagen deposition (Fig. 9, G and H), serum Col IV (Fig. 9 I), and HA levels (Fig. 9 J) in old-BMT mice.

These findings were validated in a bile duct ligation (BDL)-induced fibrosis model (Fig. S5 A). Old-BMT mice exhibited increased intrahepatic MDMs infiltration (Fig. S5 B); elevated serum Ccl2, Ccl8, and IL-6 levels (Fig. S5 C); collagen deposition (Fig. S5, D and E); Col IV (Fig. S5 F); and HA levels (Fig. S5 G) in comparison with young-BMT mice. Bindarit plus IL-6 Abs treatment significantly mitigated fibrosis-related indexes in both young-BMT and old-BMT mice (Fig. S5, D–G). In conclusion, Tet2ΔMye-induced myeloid hematopoiesis exacerbates liver fibrosis in both young and aging mice through a consistent Ccl2/Ccl8–pMDMs–IL-6–HSCs pathway highlighting a unified therapeutic target for age-associated fibrosis.

Aging-related Tet2 ΔMye -driven clonal hematopoiesis exacerbates liver fibrosis, and IL-1β–NLRP3 pathway is not involved in the liver fibrosis in Mye-KO-CCl 4 mice. (A) Chart for the construction of an aging-related Tet2ΔMye-induced clonal hematopoiesis mouse model with liver fibrosis. BDL was performed to construct a liver fibrosis model in young-BMT and old-BMT mice 6 wk after BMT. (B) Frequency of MDMs in livers of young-BMT and old-BMT mice after BDL for 4 wk (n = 4 for each group). (C) The serum levels of CCL2, CCL8, and IL-6 in young-BMT and old-BMT mice after BDL for 4 wk (n = 4 for each group). (D and E) Picrosirius red staining (D) (scale bar, 125 μm) and quantitative analysis of collagen deposition (E) in livers from young-BMT and old-BMT mice following BDL, treated with Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs (n = 4 for each group). (F and G) Changes of serum Col IV (F) and HA (G) levels in young-BMT and old-BMT mice treated with Bindarit, anti–IL-6 Abs, or Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs (n = 4 for each group). (H) IF (scale bar, 50 μm) and statistical analysis of NLRP3 in the liver of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 5 for each group). Red: anti-NLRP3; blue: DAPI. (I) IHC staining (scale bar, 50 μm) and statistical analysis of NLRP3 in the liver of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 5 for each group). (J) Inhibition of IL-1β in the serum of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 5 for each group). (K and L) Change of Ccl2 (K) and Ccl8 (L) in the serum of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after anti–IL-1β Ab treatment (n = 4–5 for each group). (M and N) Effect of anti–IL-1β Ab treatment on the mRNA levels of Acta2 and Col1a1 (n = 5 for each group). (O) Picrosirius red staining of collagen deposition in the liver tissue of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice after treatment of anti–IL-1β Ab (n = 5 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (B, C, and E–O). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, paired Student’s t test (B, C, and H, and I) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (E–G and J–N). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Aging-related Tet2 ΔMye -driven clonal hematopoiesis exacerbates liver fibrosis, and IL-1β–NLRP3 pathway is not involved in the liver fibrosis in Mye-KO-CCl 4 mice. (A) Chart for the construction of an aging-related Tet2ΔMye-induced clonal hematopoiesis mouse model with liver fibrosis. BDL was performed to construct a liver fibrosis model in young-BMT and old-BMT mice 6 wk after BMT. (B) Frequency of MDMs in livers of young-BMT and old-BMT mice after BDL for 4 wk (n = 4 for each group). (C) The serum levels of CCL2, CCL8, and IL-6 in young-BMT and old-BMT mice after BDL for 4 wk (n = 4 for each group). (D and E) Picrosirius red staining (D) (scale bar, 125 μm) and quantitative analysis of collagen deposition (E) in livers from young-BMT and old-BMT mice following BDL, treated with Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs (n = 4 for each group). (F and G) Changes of serum Col IV (F) and HA (G) levels in young-BMT and old-BMT mice treated with Bindarit, anti–IL-6 Abs, or Bindarit plus anti–IL-6 Abs (n = 4 for each group). (H) IF (scale bar, 50 μm) and statistical analysis of NLRP3 in the liver of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 5 for each group). Red: anti-NLRP3; blue: DAPI. (I) IHC staining (scale bar, 50 μm) and statistical analysis of NLRP3 in the liver of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice (n = 5 for each group). (J) Inhibition of IL-1β in the serum of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice (n = 5 for each group). (K and L) Change of Ccl2 (K) and Ccl8 (L) in the serum of oil- or CCl4-treated Tet2WT and Tet2ΔMye mice after anti–IL-1β Ab treatment (n = 4–5 for each group). (M and N) Effect of anti–IL-1β Ab treatment on the mRNA levels of Acta2 and Col1a1 (n = 5 for each group). (O) Picrosirius red staining of collagen deposition in the liver tissue of Tet2WT-CCl4 and Tet2ΔMye-CCl4 mice after treatment of anti–IL-1β Ab (n = 5 for each group). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results (B, C, and E–O). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, paired Student’s t test (B, C, and H, and I) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (E–G and J–N). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

Tet2-mutant clonal hematopoiesis (CHIP) in aged individuals is associated with severe liver fibrosis and elevated Ccl2/Ccl8 levels

To investigate whether Tet2-mutant CHIP in leukocytes contributes to accelerated liver fibrosis and altered chemokine signaling, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) on peripheral blood samples from 14 patients with liver fibrosis quantitatively assessed by ultrasound elastography to identify CHIP-associated mutations. Consistent with prior reports, we detected recurrent somatic mutations in DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha (DNMT3A), TET2, tumor protein p53 (TP53), and ASXL transcriptional regulator 1 (ASXL1). Notably, TET2 mutations were present in 3 of 14 (21.4%) patients with liver fibrosis (Fig. 10 A).

TET2 Mut -related CHIP in aged individuals is associated with severe liver fibrosis and elevated Ccl2/Ccl8 levels. (A) The mutation frequency of genes known to be drivers of clonal hematopoiesis in aged individuals. The top four most frequently mutated genes in CHIP for the current study population were as follows: DNMT3A, TET2, TP53, and ASXL1. (B) The severity of liver fibrosis in TET2WT and TET2Mut population with liver fibrosis. TET2WT, n = 11; TET2Mut, n = 3. (C and D) The different levels of Ccl2 (C) and Ccl8 (D) in peripheral blood of patients with DNMT3A, TET2, TP53, and ASXL1 mutations. TP53Mut, n = 3; ASLX1Mut, n = 1; DNMT3AMut, n = 2; TET2Mut, n = 3. (E and F) The levels of Ccl2 (E) and Ccl8 (F) in peripheral blood of TET2WT and TET2Mut population with liver fibrosis. TET2WT, n = 11; TET2Mut, n = 3. Data are the accumulative results from at least two independent experiments (A–F). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (B, E, and F) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (C and D). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

TET2 Mut -related CHIP in aged individuals is associated with severe liver fibrosis and elevated Ccl2/Ccl8 levels. (A) The mutation frequency of genes known to be drivers of clonal hematopoiesis in aged individuals. The top four most frequently mutated genes in CHIP for the current study population were as follows: DNMT3A, TET2, TP53, and ASXL1. (B) The severity of liver fibrosis in TET2WT and TET2Mut population with liver fibrosis. TET2WT, n = 11; TET2Mut, n = 3. (C and D) The different levels of Ccl2 (C) and Ccl8 (D) in peripheral blood of patients with DNMT3A, TET2, TP53, and ASXL1 mutations. TP53Mut, n = 3; ASLX1Mut, n = 1; DNMT3AMut, n = 2; TET2Mut, n = 3. (E and F) The levels of Ccl2 (E) and Ccl8 (F) in peripheral blood of TET2WT and TET2Mut population with liver fibrosis. TET2WT, n = 11; TET2Mut, n = 3. Data are the accumulative results from at least two independent experiments (A–F). All data are shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (B, E, and F) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (C and D). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; P > 0.05 not significant (ns).

In our cohort of 14 patients with confirmed liver fibrosis, targeted analysis of CHIP-associated driver mutations in peripheral blood leukocytes revealed the following distribution of canonical age-related variants: TRP53 mutations were detected in three cases (21.4%), ASXL1 in one case (7.1%), DNMT3A in two cases (14.3%), and TET2 in three cases (21.4%). Notably, one patient demonstrated concurrent TP53 and ASXL1 mutations. Furthermore, individuals with TET2Mut CHIP exhibited significantly more advanced liver fibrosis and relatively higher levels of Ccl2 and Ccl8 in serum compared with TET2 WT (TET2WT) counterparts, even after adjusting for co-occurring mutations (Fig. 10, B–D). Plasma analysis revealed markedly elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory chemokines Ccl2 and Ccl8 in TET2Mut carriers (Fig. 10, E and F).These findings mirror our experimental findings in murine models and demonstrate that TET2Mut-related CHIP in aging individual promotes liver fibrogenesis and is linked to a distinct inflammatory signature characterized by Ccl2/Ccl8 upregulation.

Discussion