Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) are heterogeneous; thus, their roles in tumor development could vary depending on the cancer type. Here, we showed that TANs affect metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis hepatocellular carcinoma (MASH-related HCC) more than viral-associated HCC. We attributed this difference to the predominance of SiglecFhi TANs in MASH-related HCC tumors. Linoleic acid and GM-CSF, which are commonly elevated in the MASH-related HCC microenvironment, fostered the development of this c-Myc–driven TAN subset. Through TGFβ secretion, SiglecFhi TANs promoted HCC stemness, proliferation, and migration. Importantly, SiglecFhi TANs supported immune evasion by directly suppressing the antigen presentation machinery of tumor cells. SiglecFhi TAN removal increased the immunogenicity of a MASH-related HCC model and sensitized it to immunotherapy. Likewise, a high SiglecFhi TAN signature was associated with poor prognosis and immunotherapy resistance in HCC patients. Overall, our study highlights the importance of understanding TAN heterogeneity in cancer to improve therapeutic development.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common and lethal malignancies in the world. It arises from various etiologies, with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections being primary risk factors for HCC development. However, due to the increasing prevalence of obesity globally, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is emerging as the fastest-growing cause of HCC (Huang et al., 2022; Llovet et al., 2021). As a prototypical inflammation-driven cancer, the immune contexture in the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a crucial role in HCC development (Llovet et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the influence of etiology on the immune TME remains poorly understood. Considering that the responses to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy in HCC patients are etiology-dependent, with non-viral-related patients exhibiting poorer outcomes than their viral-related counterparts (Haber et al., 2021; Pfister et al., 2021), it is vital to unravel the distinct immune dysfunctions associated with different HCC etiologies.

Neutrophils have been found to accumulate in a wide variety of solid tumors. While most studies link these tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) to protumorigenic effects, some research also highlights their antitumorigenic properties (Engblom et al., 2017; Gungabeesoon et al., 2023; Siwicki and Pittet, 2021). Recent advancements in high-dimensional single-cell analysis have finally reconciled these differences by revealing that TANs are not homogenous as previously thought but are a heterogeneous population. In fact, they have been reprogrammed within the TME to acquire diverse transcriptomic, phenotypic, and functional properties (Hedrick and Malanchi, 2022; Ng et al., 2019; 2024; Siwicki and Pittet, 2021). TAN diversity has recently been reported in patients with HCC (Xue et al., 2022). However, numerous questions remain unanswered regarding the factors driving TAN diversity, the specific functions of TAN subsets, their prevalence in different TMEs, and their impact on therapy response.

In this study, we showed that TANs had a more deleterious effect on MASH-related HCC than on viral-related HCC. Specifically, we found that the TME of MASH-related HCC fostered the emergence of a pro-tumor TAN subpopulation defined by high sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin F (SiglecF) expression and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) production. In addition to their promotion of tumor cell stemness, proliferation, and migration, these SiglecFhi TANs directly suppressed MHCI presentation on tumor cells, leading to reduced tumor immunogenicity and ICB therapy resistance. This unprecedented function of SiglecFhi TANs in promoting an aggressive tumor phenotype with high proliferative capacity and enhanced immune evasion ability positions them as a crucial target for immunotherapy.

Results

Neutrophils are pathogenic in MASH-related HCC

Emerging evidence suggests that TANs play a pathogenic role in HCC (Geh et al., 2022; He et al., 2015; Leslie et al., 2022; Li et al., 2015; van der Windt et al., 2018; Xue et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2019). Interestingly, although high expression of a TAN signature derived from a pan-cancer analysis (Zaitsev et al., 2022) significantly predicted poor prognosis in HCC patients from the Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) database, it was unable to do so in other HCC datasets, including the International Cancer Genome Consortium’s (ICGC) “Liver Cancer-RIKEN, Japan Project” (LIRI-JP), the Liver Cancer Institute (LCI) (GSE14520), and GSE76427 (Fig. 1 A). A thorough examination of their clinical details revealed an etiological bias among the HCC patients in these datasets. Of note, whilst the LIRI-JP, LCI, and GSE76427 datasets predominantly contain patients with pre-existing HBV or HCV infections, more than half of those from the TCGA cohort have a non-viral background (Fig. 1 B). These findings suggest that the effects of TANs on HCC development vary depending on the etiology. In particular, TANs may play a more pathogenic role in non-viral related HCC, of which MASH-related HCC is a major contributor (Huang et al., 2022; Llovet et al., 2021). However, one limitation of the TCGA-LIHC dataset is that the etiology of non-viral patients is insufficiently detailed. To better classify these patients, we generated a MASH score based on patients with defined etiologies in the TCGA-LIHC and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) datasets (Govaere et al., 2020). We found that the TAN signature showed significant prognostic potential only for patients with high MASH score but not for those with a low MASH score (Fig. 1 C). We further demonstrated this etiology-dependent phenotype by using two autochthonous HCC models, which were induced by hydrodynamic tail vein injections (HTVIs) of plasmid DNA in C57BL/6J mice. To mimic MASH-related HCC, we delivered transposon vectors expressing oncogenic NRAS and AKT into the liver. Consistent with our recent reports (Chen et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022), these NRAS/AKT tumors expressed high levels of the HCC marker α-fetoprotein (AFP) and exhibited typical MASH features such as steatosis, ballooning hepatocytes, and increased levels of liver triglycerides and diglycerides (Fig. 1 D; and Fig. S1, A and D). Given that the most common genetic alteration in viral-related HCC is the simultaneous deregulation of MYC (overexpression) and TP53 (inactivation or mutation) (Llovet et al., 2021; Péneau et al., 2022; Tornesello et al., 2016), we mimicked this etiology by delivering a MYC-expressing transposon vector, along with a CRISPR plasmid specifically targeting p53. As expected, the resulting MYC/sgp53 tumors were positive for AFP without any MASH features (Fig. 1 D; and Fig. S1, B and D). We observed that both HCC models were highly infiltrated by TANs, which accounted for around 30% of the tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs) (Fig. 1 E). However, when TANs were depleted by anti-Ly6G mAb injections, following a protocol optimized for their controlled and durable elimination (Boivin et al., 2020), a significant reduction in tumor burden was only observed for NRAS/AKT tumors, but not MYC/sgp53 tumors (Fig. 1 F and Fig. S1 E), suggesting that TANs promoted tumor development in MASH-related HCCs. We further validated these findings using a dietary model of MASH-related HCC, in which C57BL/6J mice were maintained on a methionine- and choline-deficient (MCD) diet for 2 wk before being intrahepatically injected with the RIL175 HCC cell line (Brown et al., 2018) (Fig. S1, C and D). As expected, anti-Ly6G mAb injections only impaired the growth of RIL175 tumors in mice kept on an MCD diet and not in those with a chow diet (CD) (Fig. 1 G). Together, these findings from both HCC patients and murine models suggest that the pathogenic influence of TANs on HCC development is etiology-dependent and that TANs have a more deleterious effect on MASH-related HCC.

Neutrophils are pathogenic in MASH-related HCC. (A) Kaplan–Meier plots comparing HCC patients from various datasets with high (top 25%) and low (top 25%) TAN signature scores. (B) The etiologies of HCC patients in A. (C) Kaplan–Meier plots comparing different groups of TCGA-LIHC patients with high and low TAN signature scores. (D and E) Mice bearing NRAS/AKT or cMYC/sgp53 HCC tumors were sacrificed at 4 or 7 wk after tumor induction, respectively. Representative images of AFP staining (left) and neutral lipid staining (right) on liver sections. The scale bar represents 100 µm (D). Representative FACs plots and percentages of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils among CD45+TILs (n = 4–5/group) (E). (F) NRAS/AKT HCC mice (top panel) and cMYC/sgp53 HCC mice (bottom panel) were treated with αLy6G or isotype control mAbs for 2 wk. Representative images of HCC livers (left); liver-to-body weight ratio (middle) and tumor nodule counts (right). Scale bar represents 1 cm. (G) Tumor volume of RIL175 orthotopic HCC mice fed with MCD diet (MCD + RIL175; top) or Chow diet (CD + RIL175; bottom), following αLy6G or isotype control mAb treatments. Each symbol represents one mouse. Data are mean ± SEM (E–G) and represent two to three independent experiments (D–G). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 by Kaplan–Meier analysis (A and C) and unpaired Student’s t test (F and G). NA, not available; T, tumor; NT, non-tumor.

Neutrophils are pathogenic in MASH-related HCC. (A) Kaplan–Meier plots comparing HCC patients from various datasets with high (top 25%) and low (top 25%) TAN signature scores. (B) The etiologies of HCC patients in A. (C) Kaplan–Meier plots comparing different groups of TCGA-LIHC patients with high and low TAN signature scores. (D and E) Mice bearing NRAS/AKT or cMYC/sgp53 HCC tumors were sacrificed at 4 or 7 wk after tumor induction, respectively. Representative images of AFP staining (left) and neutral lipid staining (right) on liver sections. The scale bar represents 100 µm (D). Representative FACs plots and percentages of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils among CD45+TILs (n = 4–5/group) (E). (F) NRAS/AKT HCC mice (top panel) and cMYC/sgp53 HCC mice (bottom panel) were treated with αLy6G or isotype control mAbs for 2 wk. Representative images of HCC livers (left); liver-to-body weight ratio (middle) and tumor nodule counts (right). Scale bar represents 1 cm. (G) Tumor volume of RIL175 orthotopic HCC mice fed with MCD diet (MCD + RIL175; top) or Chow diet (CD + RIL175; bottom), following αLy6G or isotype control mAb treatments. Each symbol represents one mouse. Data are mean ± SEM (E–G) and represent two to three independent experiments (D–G). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 by Kaplan–Meier analysis (A and C) and unpaired Student’s t test (F and G). NA, not available; T, tumor; NT, non-tumor.

Characterization of murine models reveals MASH-HCC features in NRAS/AKT HCC and MCD + RIL175 models. (A–C) Representative H&E liver sections. The HCC tumor region is bounded by the dotted line. Scale bar represents 100 µm. (D) Untargeted lipidomic LC-MS analysis of the various types of HCC tumors and naïve liver. (E) Representative FACs plots and percentages of Ly6G+CD11b+ neutrophils (TANs) among CD45+TILs from cMYC/sgp53 tumors after 2 wk of αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatment (top). Quantity of TANs per gram of tissue (bottom). (F and G) Gating strategies for tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (F): TANs (i), DCs (ii), CD8+T cells (iii) and their cytokines (iv), and tumor cells (G) from all the HCC models used. Each symbol represents one mouse. Data are mean ± SEM and represent two independent experiments (E). ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (E). T, tumor; NT, non-tumor; TG, triglyceride; DG, diglyceride; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; SM, sphingomyelins.

Characterization of murine models reveals MASH-HCC features in NRAS/AKT HCC and MCD + RIL175 models. (A–C) Representative H&E liver sections. The HCC tumor region is bounded by the dotted line. Scale bar represents 100 µm. (D) Untargeted lipidomic LC-MS analysis of the various types of HCC tumors and naïve liver. (E) Representative FACs plots and percentages of Ly6G+CD11b+ neutrophils (TANs) among CD45+TILs from cMYC/sgp53 tumors after 2 wk of αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatment (top). Quantity of TANs per gram of tissue (bottom). (F and G) Gating strategies for tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (F): TANs (i), DCs (ii), CD8+T cells (iii) and their cytokines (iv), and tumor cells (G) from all the HCC models used. Each symbol represents one mouse. Data are mean ± SEM and represent two independent experiments (E). ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (E). T, tumor; NT, non-tumor; TG, triglyceride; DG, diglyceride; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; SM, sphingomyelins.

TANs are heterogenous with a notable enrichment of the SiglecFhi subset in MASH-related HCC

TANs are known to be heterogeneous, consisting of functionally distinct subsets that can either support or suppress tumor growth (Hedrick and Malanchi, 2022; Siwicki and Pittet, 2021). We asked if the varying effects of TANs on different types of HCC could be attributed to differences in the TAN subset composition. To address this, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on TILs, splenocytes, and bone marrow (BM) cells isolated from NRAS/AKT-injected mice. A total of 14,105 neutrophils, with an average of 1,136 genes per cell, were identified using SingleR and their expression of lineage markers (Fig. S2 A). We identified six transcriptomically distinct TAN subsets and five splenic and BM neutrophil subsets (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S2 B) through unsupervised clustering. These 11 neutrophil subsets encompassed the spectrum of neutrophils observed in HCC patients (Xue et al., 2022), with the Siglecf-Hi and Siglecf-Lo subsets bearing the closest resemblance to human pro-tumor TANs (Xue et al., 2022) (Fig. 2 B). Furthermore, the gene expression profiles of these Siglecf-expressing subsets from HCC tumors were similar to those of tumor-promoting SiglecFhi TANs previously identified in lung cancers (Engblom et al., 2017; Pfirschke et al., 2020) (Fig. 2 C), suggesting the potential tumorigenic properties of these TANs. This diversity of TAN subsets in HCC was partially captured by flow cytometric analysis based on their surface expression levels of SiglecF. In particular, a group of SiglecFhi neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+SiglecFhi cells), corresponding to the Siglecf-Hi TAN cluster in our scRNA-seq analysis (Fig. S2 C), were highly enriched in tumors compared with blood, spleen, or BM of NRAS/AKT-injected mice (Fig. 2, D and E; and Fig. S2 D). Further morphological, phenotypical, and functional analysis revealed that SiglecFhi TANs were mature and aged neutrophils. These cells exhibited segmented nuclei and were characterized by high expression of CXCR2, CXCR4, and dcTRAIL-R1, as well as low expression of CD62L. Additionally, they displayed proficiency in phagocytosis, degranulation, and the ability to undergo NETosis (Fig. 2 F; and Fig. S2, E and F). Crucially, SiglecFhi TANs were exclusively present in MASH-related HCC tumors (NRAS/AKT; MCD + RIL175 diet) and not in their non-MASH-related counterparts (cMYC/sgp53; chow + RIL175 diet), highlighting the relevance of this population in MASH-related HCC (Fig. 2 D and Fig. S2 G). Of note, depletion of TANs through anti-Ly6G mAb injections eliminated SiglecFhi TANs while retaining some SiglecF– TANs (Fig. 2 G and Fig. S2 H), suggesting that this method could serve as a potential approach to analyze the in vivo effects of SiglecFhi TANs in subsequent investigations. Thus far, our results indicated that SiglecFhi TANs represent a TAN population that was highly enriched in murine MASH-related HCC models. To establish human relevance of these findings, we defined a gene signature representing Siglecf-Hi–like TANs (Fig. S2 I). We then applied it to the microarray data of HCC cohorts with clinically confirmed MASH and non-MASH cases (Pinyol et al., 2021; Villanueva et al., 2015). We observed that while a conventional neutrophil signature (Abbas et al., 2005) was not biased to etiology, the Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature was significantly enriched in MASH-HCC patients (Fig. 2 H). To further investigate the impact of Siglecf-Hi–like TANs on HCC development, we assessed their prognostic potential through the TCGA-LIHC dataset, which contains patient survival information. As expected, the Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature predicted poor prognosis in non-viral HCC patients with high MASH scores, but not in those with low MASH scores or those who were virally infected (Fig. 2 I). Together, these findings suggest that TANs are highly diverse and a pro-tumor SiglecFhi subset is predominately enriched in MASH-related HCC.

Neutrophil identification and characteristics. (A) Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projections (UMAPs) (left) and expression of neutrophil lineage markers (right) by the major immune populations identified from the scRNA-seq of the BM and spleen (top), and HCC tumors (bottom) of NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (B) Dot plot of the differently expressed genes by each neutrophil cluster in the BM and spleen (top), and HCC tumor (bottom). (C) RNA-seq analyses were performed on SiglecFhi and SiglecF– TANs purified from NRAS/AKT-HCC tumors. A gene set defining SiglecFhi TANs was generated from their top 100 differentially expressed genes. The distribution of this gene set among TAN subsets. (D) Representative FACs plots and percentage of SiglecFhi neutrophils detected in the BM, spleen, blood, and tumor of NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (E) CXCR2, CXCR4, CD62L, and dcTRAIL-R1 expression within SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs of NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (F) Functional characterization of BM neutrophils, SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs from NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (G) Representative FACs plots and percentages of SiglecFhi TANs of RIL175 orthotopic HCC mice fed with MCD diet (MCD + RIL175; left) or Chow diet (CD + RIL175; right) (n = 3/group). (H) Representative immunofluorescence images and proportion of SiglecFhi TANs (myeloperoxidase [MPO]: red; SiglecF: green; nucleus: blue) in NRAS/AKT HCC tumors after 2 wk of treatment with αLy6G or isotype control mAbs. Scale bar represents 100 µm. (I) Expression levels of genes in the Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature across various cell types in the tumor of HCC patients (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA007744). Each symbol represents one mouse. Data are mean ± SEM and represent two independent experiments (D–H). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA (F) and unpaired Student’s t test (H).

Neutrophil identification and characteristics. (A) Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projections (UMAPs) (left) and expression of neutrophil lineage markers (right) by the major immune populations identified from the scRNA-seq of the BM and spleen (top), and HCC tumors (bottom) of NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (B) Dot plot of the differently expressed genes by each neutrophil cluster in the BM and spleen (top), and HCC tumor (bottom). (C) RNA-seq analyses were performed on SiglecFhi and SiglecF– TANs purified from NRAS/AKT-HCC tumors. A gene set defining SiglecFhi TANs was generated from their top 100 differentially expressed genes. The distribution of this gene set among TAN subsets. (D) Representative FACs plots and percentage of SiglecFhi neutrophils detected in the BM, spleen, blood, and tumor of NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (E) CXCR2, CXCR4, CD62L, and dcTRAIL-R1 expression within SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs of NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (F) Functional characterization of BM neutrophils, SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs from NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (G) Representative FACs plots and percentages of SiglecFhi TANs of RIL175 orthotopic HCC mice fed with MCD diet (MCD + RIL175; left) or Chow diet (CD + RIL175; right) (n = 3/group). (H) Representative immunofluorescence images and proportion of SiglecFhi TANs (myeloperoxidase [MPO]: red; SiglecF: green; nucleus: blue) in NRAS/AKT HCC tumors after 2 wk of treatment with αLy6G or isotype control mAbs. Scale bar represents 100 µm. (I) Expression levels of genes in the Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature across various cell types in the tumor of HCC patients (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA007744). Each symbol represents one mouse. Data are mean ± SEM and represent two independent experiments (D–H). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA (F) and unpaired Student’s t test (H).

Protumorigenic SiglecF hi TANs are enriched in MASH-related HCC tumors and can be removed through αLy6G mAb injections. (A–C) scRNA-seq analysis of neutrophils from NRAS/AKT HCC mice. UMAP visualization of neutrophil subsets (A). Pearson’s correlations across neutrophil clusters in NRAS/AKT HCC mice and HCC patients (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA007744) (B). Distributions of SiglecFhigh neutrophil signature score derived from Engblom et al. (2017) in TAN subsets (C). (D) Representative FACs plots of SiglecFhi TANs detected in NRAS/AKT HCC (left) and cMYC/sgp53 HCC (right) tumors. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of SiglecFhi TANs (MPO: red; SiglecF: green; nucleus: blue) in NRAS/AKT HCC tumors. Dotted oval shows the tumor region. Scale bars represent 200 and 5 μm. (F) Representative cytospin images of SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (G) Representative FACs plots and quantities of TANs (CD11b+ Ly6Gintracellular+ (top) and TAN subsets (bottom) in NRAS/AKT HCC tumors after 2 wk of αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments. (H) Distributions of conventional neutrophil signature and Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature scores in HCC patients with non-MASH (GSE63898) and MASH (GSE164760) etiologies. (I) Kaplan–Meier plots comparing different groups of TCGA-LIHC patients with high and low Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature score. Each symbol represents one mouse. Data are mean ± SEM (D and G) and represent three independent experiments (D–G). ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (D and G-upper panel) and one sample t test (G-lower panel). Data are analyzed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (H) and Kaplan–Meier analysis (I). hPB, human peripheral blood; hAL, human adjacent liver.

Protumorigenic SiglecF hi TANs are enriched in MASH-related HCC tumors and can be removed through αLy6G mAb injections. (A–C) scRNA-seq analysis of neutrophils from NRAS/AKT HCC mice. UMAP visualization of neutrophil subsets (A). Pearson’s correlations across neutrophil clusters in NRAS/AKT HCC mice and HCC patients (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA007744) (B). Distributions of SiglecFhigh neutrophil signature score derived from Engblom et al. (2017) in TAN subsets (C). (D) Representative FACs plots of SiglecFhi TANs detected in NRAS/AKT HCC (left) and cMYC/sgp53 HCC (right) tumors. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of SiglecFhi TANs (MPO: red; SiglecF: green; nucleus: blue) in NRAS/AKT HCC tumors. Dotted oval shows the tumor region. Scale bars represent 200 and 5 μm. (F) Representative cytospin images of SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (G) Representative FACs plots and quantities of TANs (CD11b+ Ly6Gintracellular+ (top) and TAN subsets (bottom) in NRAS/AKT HCC tumors after 2 wk of αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments. (H) Distributions of conventional neutrophil signature and Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature scores in HCC patients with non-MASH (GSE63898) and MASH (GSE164760) etiologies. (I) Kaplan–Meier plots comparing different groups of TCGA-LIHC patients with high and low Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature score. Each symbol represents one mouse. Data are mean ± SEM (D and G) and represent three independent experiments (D–G). ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (D and G-upper panel) and one sample t test (G-lower panel). Data are analyzed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (H) and Kaplan–Meier analysis (I). hPB, human peripheral blood; hAL, human adjacent liver.

SiglecFhi TANs directly act on tumor cells and promote tumorigenesis

To gain insight into the contributions of SiglecFhi TANs in tumor development, we investigated the tumorigenic pathways that were positively correlated with the abundance of these cells in HCC patients. We observed a high correlation between angiogenesis and Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signatures, supporting prior findings that protumor TANs are one of the sources of VEGFΑ within the TME (Engblom et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2024; Ozel et al., 2022) (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S3 A). Of note, we found that pathways related to cancer stemness, cancer proliferation, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) were also significantly correlated (Fig. 3 A). Consistently, tumor cells isolated from anti-Ly6G mAb-treated NRAS/AKT-injected mice, which lacked SiglecFhi TANs, exhibited a reduced cancer stemness signature (Fig. S3 B), a lower proportion of cancer stem cells (CSCs) (Fig. S3, C and D), and a decreased ex vivo repopulation capacity (Fig. S3 E). Together, these findings suggest that SiglecFhi TANs could promote tumorigenesis by directly affecting tumor cell behavior. To test this, we sort-purified SiglecFhi and SiglecF− TANs from NRAS/AKT tumors and co-cultured them with the HCC cell line RIL175 (Fig. 3 B). Through the limiting dilution assay (Zhou et al., 2022), we observed that SiglecFhi TANs, and not SiglecF− TANs, increased tumor-initiating cell frequency (Fig. 3 C), suggesting that SiglecFhi TANs enhanced the self-renewal potential of tumor cells. Similarly, a clonogenic assay and scratch wound assay also revealed that SiglecFhi TANs could directly promote HCC cell proliferation and migration, respectively (Fig. 3, D and E). To validate the tumor-promoting role of SiglecFhi TANs in vivo, we employed an adoptive transfer model, wherein RIL175 cells were co-injected with either SiglecFhi TANs or SiglecF− TANs into contralateral flanks of C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 3 F). In line with the ex vivo findings, co-transferring SiglecFhi TANs with RIL715 cells resulted in a significant increase in tumor proliferation and an enhanced tumor growth rate (Fig. 3, G and H). Together, these findings suggest that SiglecFhi TANs contribute to HCC development by directly enhancing tumor cell proliferation, stemness, and migration.

SiglecF hi TANs directly promote tumorigenesis. (A) Pearson’s correlation of tumorigenesis-related gene signatures with Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature in the TCGA-LIHC dataset. (B–E) Sort-purified SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs were co-cultured with RIL175 cells. Schematic diagram of the sorting and co-culture strategy (B). Limiting dilution assay: representative images of spheroids formed and stem cell frequency. Scale bar represents 50 μm (C). Clonogenic assay: representative images of colonies formed and colony counts. Scale bar represents 3.5 mm (D). Scratch wound assay: representative images of the wound at indicated time points and percentage of the wound area. Scale bar represents 200 μm (E). (F–H) RIL175 cells alongside SiglecF− or SiglecFhi TANs were subcutaneously injected into C57BL/6J mice. Schematic diagram of the adoptive transfer strategy (F). Representative images and volumes of tumors at the endpoint. Scale bar represents 1 cm (G). Representative FACs plots and percentage of Ki-67+ tumor cells (H). Each symbol represents TANs isolated from two to three mice (D, E, G, and H). Data are mean ± SEM (D, E, G, and H) and represent two to three independent experiments (C, E, G, and H) or are pooled from two independent experiments (D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by Pearson’s correlation test (A), Pearson’s chi-square test with a 95% confidence interval (C), one-way ANOVA (D and E), and unpaired Student’s t test (G and H).

SiglecF hi TANs directly promote tumorigenesis. (A) Pearson’s correlation of tumorigenesis-related gene signatures with Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature in the TCGA-LIHC dataset. (B–E) Sort-purified SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs were co-cultured with RIL175 cells. Schematic diagram of the sorting and co-culture strategy (B). Limiting dilution assay: representative images of spheroids formed and stem cell frequency. Scale bar represents 50 μm (C). Clonogenic assay: representative images of colonies formed and colony counts. Scale bar represents 3.5 mm (D). Scratch wound assay: representative images of the wound at indicated time points and percentage of the wound area. Scale bar represents 200 μm (E). (F–H) RIL175 cells alongside SiglecF− or SiglecFhi TANs were subcutaneously injected into C57BL/6J mice. Schematic diagram of the adoptive transfer strategy (F). Representative images and volumes of tumors at the endpoint. Scale bar represents 1 cm (G). Representative FACs plots and percentage of Ki-67+ tumor cells (H). Each symbol represents TANs isolated from two to three mice (D, E, G, and H). Data are mean ± SEM (D, E, G, and H) and represent two to three independent experiments (C, E, G, and H) or are pooled from two independent experiments (D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by Pearson’s correlation test (A), Pearson’s chi-square test with a 95% confidence interval (C), one-way ANOVA (D and E), and unpaired Student’s t test (G and H).

Siglecf hi TAN removal impairs tumorigenesis. (A) Visualization of Vegfa expression among TILs. (B–E) Profiling of tumor cells from NRAS/AKT HCC mice after 2 wk of αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments. scRNA-seq expression of mature hepatocyte and hepatic progenitor markers (B). Representative FACs plots and percentage of Hoechst-effluxing cells (polygon gate) (C). Representative FACs plots and percentage of CD13+CD133+ CSCs (polygon gate) (D). Stem cell frequency in tumor cells isolated from NRAS/AKT HCC mice 1 wk following αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments (E). Each symbol represents one mouse (C and D). Data are mean ± SEM and represent two independent experiments (C–E). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by unpaired Student’s t test (C and D) and Pearson’s chi-square test with a 95% confidence interval (E). MQs, macrophages; DCs, dendritic cells.

Siglecf hi TAN removal impairs tumorigenesis. (A) Visualization of Vegfa expression among TILs. (B–E) Profiling of tumor cells from NRAS/AKT HCC mice after 2 wk of αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments. scRNA-seq expression of mature hepatocyte and hepatic progenitor markers (B). Representative FACs plots and percentage of Hoechst-effluxing cells (polygon gate) (C). Representative FACs plots and percentage of CD13+CD133+ CSCs (polygon gate) (D). Stem cell frequency in tumor cells isolated from NRAS/AKT HCC mice 1 wk following αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments (E). Each symbol represents one mouse (C and D). Data are mean ± SEM and represent two independent experiments (C–E). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by unpaired Student’s t test (C and D) and Pearson’s chi-square test with a 95% confidence interval (E). MQs, macrophages; DCs, dendritic cells.

SiglecFhi TANs exert protumor functions via TGFβ

We next investigated the mechanism underlying the pro-tumor effects of SiglecFhi TANs. To this end, bulk RNA-seq analysis was performed on RIL175 cells cultured with and without SiglecFhi or SiglecF− TANs. We then examined the differentially expressed genes between different groups using Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. As expected, SiglecFhi TAN-treatment upregulated pathways related to cell migration, proliferation, and Wnt signaling (Fig. 4 A). Of note, genes involved in TGFβ stimulation were also significantly enriched in RIL175 cells upon SiglecFhi TANs addition (Fig. 4 A). TGFβ is a potent tumorigenic cytokine that is essential for HCC development (Chen et al., 2019). Thus, we postulated that SiglecFhi TANs promoted HCC growth through TGFβ production, which was supported by cell–cell interaction analysis of NRAS/AKT tumors. Tgfb1 was inferred as one of the top ligands affecting the tumor cell transcriptome (Fig. 4 B). Importantly, the tumor-acting TGFβ was mainly produced by TANs as its effects were significantly diminished following anti-Ly6G mAb depletion (Fig. 4 C). Upon investigating the source of TGFβ among TAN subsets, we observed a significant upregulation of genes associated with TGFβ1 production (Tgfb1, Srebf1, Plg, and Atp6ap2) among Siglecf-Hi TANs (Fig. 4 D). This finding was further supported at the protein level. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that SiglecFhi TANs significantly increased the expression of latency-associated peptides associated with TGFβ1 (LAP [TGFβ1]) compared with SiglecF− TANs (Fig. 4 E). Furthermore, freshly isolated SiglecFhi TANs, but not their SiglecF− counterparts, produced high levels of TGFβ1 even in the absence of further stimulation (Fig. 4 F).

SiglecF hi TANs secrete TGFβ. (A) GO analysis of differentially expressed genes between RIL175 cells and those co-cultured with SiglecFhi TANs. BP, biological process. (B and C) NicheNet analysis of scRNA-seq data from NRAS/AKT HCC mice treated with αLy6G or isotype control mAbs. Prioritized ligands and their target genes driving transcriptomic changes in tumor cells after αLy6G treatment (B). Log fold-change (LFC) in senders of ligands to tumor cells after αLy6G treatment (C). (D) Relative expression of indicated genes among neutrophil subsets from NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (E) Representative FACs plots (left) and percentage of LAP (TGFβ1)+ cells among TAN subsets. (F) Spontaneous TGFβ production by SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs. Each symbol represents one mouse (E) or TANs isolated from two to three mice (F). Data are mean ± SEM and represent two independent experiments (E and F). *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (E and F).

SiglecF hi TANs secrete TGFβ. (A) GO analysis of differentially expressed genes between RIL175 cells and those co-cultured with SiglecFhi TANs. BP, biological process. (B and C) NicheNet analysis of scRNA-seq data from NRAS/AKT HCC mice treated with αLy6G or isotype control mAbs. Prioritized ligands and their target genes driving transcriptomic changes in tumor cells after αLy6G treatment (B). Log fold-change (LFC) in senders of ligands to tumor cells after αLy6G treatment (C). (D) Relative expression of indicated genes among neutrophil subsets from NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (E) Representative FACs plots (left) and percentage of LAP (TGFβ1)+ cells among TAN subsets. (F) Spontaneous TGFβ production by SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs. Each symbol represents one mouse (E) or TANs isolated from two to three mice (F). Data are mean ± SEM and represent two independent experiments (E and F). *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (E and F).

Crucially, the protumor effects of SiglecFhi TANs on HCC cells were effectively ameliorated by blocking TGFβ signaling with Vactosertib, a TGFβ receptor I inhibitor. While Vactosertib did not influence RIL175 cells in the in vitro limiting dilution, clonogenic, and scratch wound assays, it significantly reduced the stemness properties, proliferation, and migration of RIL175 cells potentiated by the addition of SiglecFhi TANs (Fig. 5, A–C). We then extended our analysis to in vivo settings. First, to demonstrate that TGFβ is the key effector molecule of TANs, we induced NRAS/AKT tumors in Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl mice, which selectively ablates TGFβ secretion in neutrophils. As expected, tumor cells from Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl mice were less proliferative and contained a lower proportion of CSCs (Fig. 5, D and E). Consequently, tumor burden in Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl mice was noticeably decreased compared with littermate controls (Fig. 5, F and G). Second, we confirmed that SiglecFhi TANs exerted their protumor function via TGFβ. For this, we employed the adoptive transfer model as in Fig. 3 F, but using TGFβ receptor 1 knockdown RIL175 cells (Fig. 5 H). In contrast to the tumor-promoting effects observed with WT RIL175 cells (Fig. 3, G and H), the presence of SiglecFhi TANs showed no measurable impact on the growth of RIL175_shTgfbr1 cells relative to SiglecF– TANs (Fig. 5, I and J). Collectively, these data indicate that SiglecFhi TANs exerted their protumor functions via the release of TGFβ.

SiglecF hi TANs mediate their protumorigenic functions via TGFβ secretion. (A–C) SiglecFhi TANs were co-cultured with RIL175 cells, with or without the addition of Vactosertib (10 nM). In vitro limiting dilution (A), clonogenic (B), and scratch wound (C) assays were performed. (D–G) NRAS/AKT HCC tumors were induced in Mrp8Cre+ve.TGFβfl/fl mice (Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl) and Mrp8Cre−ve.TGFβfl/fl littermates (W/T). Representative FACs plots and percentage of Ki-67+ tumor cells (D). Representative FACs plots and percentage of CD13+CD133+ CSCs (E). Representative images of HCC livers and liver-to-body weight ratio. Scale bar represents 1 cm (F). Representative images of AFP+ tumors and tumor nodule counts. Scale bar represents 100 μm (G). (H–J) SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs were sort-purified from NRAS/AKT HCC tumors and subcutaneously injected alongside RIL175_shTgfbr1 cells into C57BL/6J mice. Schematic diagram of adoptive transfer strategy (H). Representative images and volumes of tumors at the endpoint. Scale bar represents 1 cm (I). Representative FACs plots and percentage of Ki-67+ tumor cells (J). Each symbol represents TANs isolated from two to three mice (B and C), or one mouse (D–G, I, and J). Data are mean ± SEM and represent two to three independent experiments (A, C–G, I, and J) or are pooled from two independent experiments (B). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by Pearson’s chi-square test with a 95% confidence interval (A), one-way ANOVA (B and C), or unpaired Student’s t test (D–G).

SiglecF hi TANs mediate their protumorigenic functions via TGFβ secretion. (A–C) SiglecFhi TANs were co-cultured with RIL175 cells, with or without the addition of Vactosertib (10 nM). In vitro limiting dilution (A), clonogenic (B), and scratch wound (C) assays were performed. (D–G) NRAS/AKT HCC tumors were induced in Mrp8Cre+ve.TGFβfl/fl mice (Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl) and Mrp8Cre−ve.TGFβfl/fl littermates (W/T). Representative FACs plots and percentage of Ki-67+ tumor cells (D). Representative FACs plots and percentage of CD13+CD133+ CSCs (E). Representative images of HCC livers and liver-to-body weight ratio. Scale bar represents 1 cm (F). Representative images of AFP+ tumors and tumor nodule counts. Scale bar represents 100 μm (G). (H–J) SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs were sort-purified from NRAS/AKT HCC tumors and subcutaneously injected alongside RIL175_shTgfbr1 cells into C57BL/6J mice. Schematic diagram of adoptive transfer strategy (H). Representative images and volumes of tumors at the endpoint. Scale bar represents 1 cm (I). Representative FACs plots and percentage of Ki-67+ tumor cells (J). Each symbol represents TANs isolated from two to three mice (B and C), or one mouse (D–G, I, and J). Data are mean ± SEM and represent two to three independent experiments (A, C–G, I, and J) or are pooled from two independent experiments (B). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by Pearson’s chi-square test with a 95% confidence interval (A), one-way ANOVA (B and C), or unpaired Student’s t test (D–G).

We then leveraged TGFβ, the key effector molecule of SiglecFhi TANs, to further validate the clinical relevance of this TAN subset. Once again, in HCC patient datasets, TGFβ secreted by TANs was found to strongly influence gene expression in tumor cells, including those related to proliferation (e.g., CDKN1A), stemness (e.g., CD44), and metastasis (e.g., SGK1) (Fig. 6 A). We also observed a marked upregulation of TAN-derived TGFβ expression in MASH-related HCC patients compared with their non-MASH counterparts (Fig. 6 B). Importantly, we conducted co-immunofluorescence staining on tumors surgically resected from treatment-naïve HCC patients and confirmed a significantly higher percentage of TGFβ-producing TANs in MASH-related HCC tumors compared with HBV-infected HCC tumors (Fig. 6 C). Together, these data underscored the importance of SiglecFhi TANs in the tumorigenesis of MASH-related HCC patients.

TGFβ-producing TANs are enriched in MASH-related HCC patients. (A) NicheNet analysis of HCC patient dataset (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA007744). Prioritized ligands from neutrophils, and their target genes, driving transcriptomic differences in tumor cells between patients with high or low neutrophil infiltration. (B) Distributions of TAN-derived TGFβ production signature in HCC patients with non-MASH (GSE63898) and MASH (GSE164760) etiologies. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of TGFβ-producing CD66b+neutrophils (CD66b: red; TGFβ: green; nucleus: blue) among all neutrophils in tumors resected from patients with HBV-related HCC or MASH-related HCC. Scale bars represent 50 and 20 μm. Each symbol represents one patient (C). Data is mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (B) and unpaired Student’s t test (C).

TGFβ-producing TANs are enriched in MASH-related HCC patients. (A) NicheNet analysis of HCC patient dataset (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA007744). Prioritized ligands from neutrophils, and their target genes, driving transcriptomic differences in tumor cells between patients with high or low neutrophil infiltration. (B) Distributions of TAN-derived TGFβ production signature in HCC patients with non-MASH (GSE63898) and MASH (GSE164760) etiologies. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of TGFβ-producing CD66b+neutrophils (CD66b: red; TGFβ: green; nucleus: blue) among all neutrophils in tumors resected from patients with HBV-related HCC or MASH-related HCC. Scale bars represent 50 and 20 μm. Each symbol represents one patient (C). Data is mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (B) and unpaired Student’s t test (C).

GM-CSF and linoleic-acid-induced c-Myc transcriptional activity drives SiglecFhi TAN differentiation

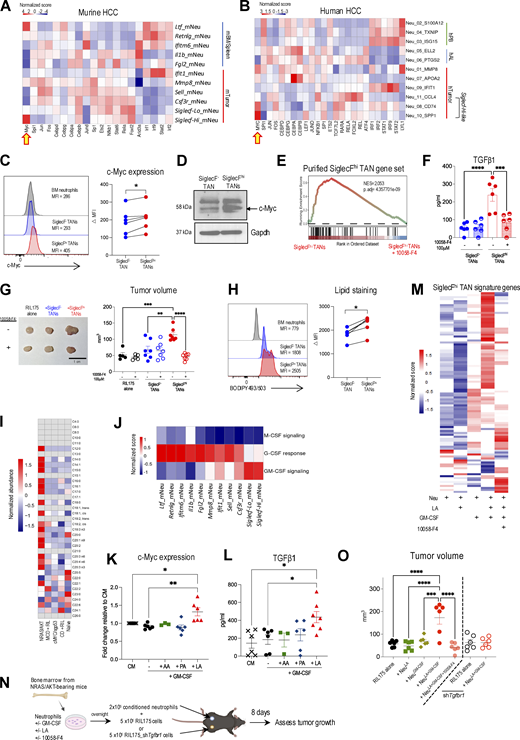

Next, we sought to identify the factors determining the emergence of SiglecFhi TANs. Tumor reprogramming is a key process enabling neutrophils to adapt to the environmental cues within the TME and consolidate their protumoral functions (Ng et al., 2024). To pinpoint the transcriptional program underscoring this dynamic in HCC tumors, we performed decoupleR analysis using the DoRothEA database (Badia-I-Mompel et al., 2022; Garcia-Alonso et al., 2019). We observed that Siglecf-Hi TANs exhibited a unique enrichment of the Myc regulon while downregulating the regulons that are associated with neutrophil commitment (Cebpa), maturation (Fos, Spi1), and activity (Jund) (Grieshaber-Bouyer et al., 2021; Gullotta et al., 2023) (Fig. 7 A). This finding was unexpected, as although c-Myc is essential for generating granulocyte/monocyte progenitors (GMPs), its repression is necessary for terminal neutrophil differentiation (Ai and Udalova, 2020), resulting in almost undetectable c-Myc levels in mature neutrophils (Poortinga et al., 2004). Similarly, the Myc regulon was also upregulated in Siglecf-Hi–like TANs present in HCC patients (Fig. 7 B), suggesting that c-Myc reactivation is a conserved phenomenon in both murine and human pro-tumor TANs. In line with the regulon analysis, we detected a significant increase in c-Myc protein levels in SiglecFhi TANs compared with SiglecF− TANs (Fig. 7, C and D). Crucially, c-Myc activation conferred the protumorigenic activity of SiglecFhi TANs as the c-Myc inhibitor 10058-F4 downregulated the expression of their signature genes (Fig. 7 E), reduced their TGFβ1 production (Fig. 7 F and Fig. S4 A), and dampened their ability to enhance tumor growth in vivo (Fig. 7 G).

GM-CSF and linoleic acid activate c-Myc regulon and drive SiglecFhiTAN development. (A and B) Relative differential transcription factor activity within each neutrophil subset in NRAS/AKT HCC mice (A) and HCC patients (B). (C) Representative histograms and c-Myc levels within SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs. (D) c-Myc expression assessed by western blot. Proteins were extracted from TANs subsets isolated from five mice. (E–G) SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs were treated with or without 10058-F4 (100 μM). GSEA analysis of genes defining SiglecFhi TANs (E). Spontaneous TGFβ production (F). RIL175 cells were s.c. injected with different TAN subsets. Tumor volume at day 8. Scale bar represents 1 cm (G). (H) Representative histograms and neutral lipid levels within SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs. (I) GC-MS analysis of HCC tumors and naïve liver. (J) Relative scores of M-CSF, G-CSF, and GM-CSF signaling within neutrophil subsets from NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (K and L) BM neutrophils from NRAS/AKT HCC mice were cultured overnight with or without the addition of GM-CSF (20 ng/ml) and the indicated fatty acids (50 μM). c-Myc expression (K) and TGFβ1 production (L). (M–O) BM neutrophils from NRAS/AKT HCC mice were cultured overnight with or without the addition of GM-CSF, linoleic acid, or 10058-F4. Heatmap of genes defining SiglecFhi TANs (M). Schematic diagram of adoptive transfer strategy (N). Tumor volume (O). Each symbol represents one mouse (C, H, K, L, and O) or TANs isolated from two to three mice (F and G). Data are mean ± SEM (F, G, K, L, and O) and are pooled from two (C, F–H, K, and L) or four (O) independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (C and H) and one-way ANOVA (F, G, K, L, and O). MFI, median fluorescence intensity; CM, complete media. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

GM-CSF and linoleic acid activate c-Myc regulon and drive SiglecFhiTAN development. (A and B) Relative differential transcription factor activity within each neutrophil subset in NRAS/AKT HCC mice (A) and HCC patients (B). (C) Representative histograms and c-Myc levels within SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs. (D) c-Myc expression assessed by western blot. Proteins were extracted from TANs subsets isolated from five mice. (E–G) SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs were treated with or without 10058-F4 (100 μM). GSEA analysis of genes defining SiglecFhi TANs (E). Spontaneous TGFβ production (F). RIL175 cells were s.c. injected with different TAN subsets. Tumor volume at day 8. Scale bar represents 1 cm (G). (H) Representative histograms and neutral lipid levels within SiglecF– and SiglecFhi TANs. (I) GC-MS analysis of HCC tumors and naïve liver. (J) Relative scores of M-CSF, G-CSF, and GM-CSF signaling within neutrophil subsets from NRAS/AKT HCC mice. (K and L) BM neutrophils from NRAS/AKT HCC mice were cultured overnight with or without the addition of GM-CSF (20 ng/ml) and the indicated fatty acids (50 μM). c-Myc expression (K) and TGFβ1 production (L). (M–O) BM neutrophils from NRAS/AKT HCC mice were cultured overnight with or without the addition of GM-CSF, linoleic acid, or 10058-F4. Heatmap of genes defining SiglecFhi TANs (M). Schematic diagram of adoptive transfer strategy (N). Tumor volume (O). Each symbol represents one mouse (C, H, K, L, and O) or TANs isolated from two to three mice (F and G). Data are mean ± SEM (F, G, K, L, and O) and are pooled from two (C, F–H, K, and L) or four (O) independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (C and H) and one-way ANOVA (F, G, K, L, and O). MFI, median fluorescence intensity; CM, complete media. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Identification of factors contributing to the development of SiglecF hi TANs. (A) Quantities of SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs after overnight culture with or without 100 μM 10058-F4. (B) Representative immunofluorescence image and proximity of TAN subsets to lipid droplets (MPO: red; SiglecF: green; BODIPY 493/503: pink; nucleus: blue) in NRAS/AKT HCC tumors. Scale bar represents 10 µm. (C–E) BM neutrophils were isolated from NRAS/AKT HCC-bearing mice and cultured overnight with or without the addition of the indicated fatty acids (50 μM). Representative FACs plots of SiglecF+ neutrophils (C). Representative histograms of c-Myc expression (D). TGFβ1 production measured by ELISA following 4 h of LPS (100 ng/ml) stimulation (E). (F) Expression of Csf2 by cellular populations within NRAS/AKT HCC tumors. (G) NRAS/AKT HCC was induced in C57BL/6J or GM-CSF reporter Csf2-iCre-EGFP+/wt mice. Representative FACs plots of GM-CSF producing cells. (H) Representative FACs plots of SiglecF+ neutrophils after 20 ng/ml GM-CSF was included in C. (I and J) Neutrophils from spleen and tumor of NRAS/AKT mice were cultured overnight with or without the addition of GM-CSF (20 ng/ml) or/and linoleic acid (50 μM). c-Myc expression within splenic neutrophils (I) or SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs (J). (K) Pseudotime of TAN development in NRAS/AKT HCC mice, calculated with Monocle 3. (L) SiglecF− or SiglecFhi TANs isolated from CD45.1+ mice were adoptively transferred into NRAS/AKT HCC-bearing CD45.2+ recipients. After 2 days, TILs were harvested, donor TANs (CD45.1+, polygon gate) and endogenous TANs were assessed for their SiglecF expression (rectangle gate indicates SiglecFhi cells). (M and N) BM neutrophils were isolated from naïve mice and cultured with and without GM-CSF (20 ng/ml) and linoleic acid (50 μM) overnight. Representative histograms of c-Myc expression (M). TGFβ1 production measured by ELISA following 4 h of LPS (100 ng/ml) stimulation (N). Each symbol represents TANs isolated from two to three mice (A and J), or one mouse (E, I, and N), or one neutrophil from screening liver sections of eight mice (B). Data are mean ± SEM and are representative of two independent experiments (C–E, G, H, and L–N) or are pooled from two independent experiments (A, B, I, and J). *P < 0.05 by unpaired Student’s t test (B). CM, complete media.

Identification of factors contributing to the development of SiglecF hi TANs. (A) Quantities of SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs after overnight culture with or without 100 μM 10058-F4. (B) Representative immunofluorescence image and proximity of TAN subsets to lipid droplets (MPO: red; SiglecF: green; BODIPY 493/503: pink; nucleus: blue) in NRAS/AKT HCC tumors. Scale bar represents 10 µm. (C–E) BM neutrophils were isolated from NRAS/AKT HCC-bearing mice and cultured overnight with or without the addition of the indicated fatty acids (50 μM). Representative FACs plots of SiglecF+ neutrophils (C). Representative histograms of c-Myc expression (D). TGFβ1 production measured by ELISA following 4 h of LPS (100 ng/ml) stimulation (E). (F) Expression of Csf2 by cellular populations within NRAS/AKT HCC tumors. (G) NRAS/AKT HCC was induced in C57BL/6J or GM-CSF reporter Csf2-iCre-EGFP+/wt mice. Representative FACs plots of GM-CSF producing cells. (H) Representative FACs plots of SiglecF+ neutrophils after 20 ng/ml GM-CSF was included in C. (I and J) Neutrophils from spleen and tumor of NRAS/AKT mice were cultured overnight with or without the addition of GM-CSF (20 ng/ml) or/and linoleic acid (50 μM). c-Myc expression within splenic neutrophils (I) or SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs (J). (K) Pseudotime of TAN development in NRAS/AKT HCC mice, calculated with Monocle 3. (L) SiglecF− or SiglecFhi TANs isolated from CD45.1+ mice were adoptively transferred into NRAS/AKT HCC-bearing CD45.2+ recipients. After 2 days, TILs were harvested, donor TANs (CD45.1+, polygon gate) and endogenous TANs were assessed for their SiglecF expression (rectangle gate indicates SiglecFhi cells). (M and N) BM neutrophils were isolated from naïve mice and cultured with and without GM-CSF (20 ng/ml) and linoleic acid (50 μM) overnight. Representative histograms of c-Myc expression (M). TGFβ1 production measured by ELISA following 4 h of LPS (100 ng/ml) stimulation (N). Each symbol represents TANs isolated from two to three mice (A and J), or one mouse (E, I, and N), or one neutrophil from screening liver sections of eight mice (B). Data are mean ± SEM and are representative of two independent experiments (C–E, G, H, and L–N) or are pooled from two independent experiments (A, B, I, and J). *P < 0.05 by unpaired Student’s t test (B). CM, complete media.

Next, we sought to determine the tumor factors responsible for c-Myc activation in SiglecFhi TANs. Given that this TAN population only arose from MASH-related HCC models (Fig. 2), was closely positioned to lipid droplets (Fig. S4 B), and displayed a lipid-laden phenotype (Fig. 7 H), we speculated that c-Myc activation might be driven by lipids specifically accumulated within these tumors. To this end, we performed lipidomic profiling of tumors from the four HCC models used in this study (Fig. 1). As expected, several classes of fatty acids (FAs) were overexpressed in NRAS/AKT tumors (Fig. 7 I). Among these 19 FAs, we focused our analysis on: (1) palmitic acid (PA, C16:0) due to its abundant presence in MASH patients; (2) linolenic acid (LA, C18:2), which is elevated both in MASH patients and MCD+RIL175 tumors; and (3) arachidonic acid (AA, C20:4), owing to its similar enrichment in MCD+RIL175 tumors (Fig. 7 I) (Chiappini et al., 2017). BM neutrophils isolated from NRAS/AKT-injected mice were cultured with these FAs. However, no changes in neutrophil phenotype, c-Myc expression, and cytokine production were observed (Fig. S4, C–E), highlighting a requirement for additional tumor factors. For this, we delved deeper into the transcriptome of all TAN subsets and found that Siglecf-Hi TANs displayed high GM-CSF signaling signature (Fig. 7 J). GM-CSF is a neutrophil-activating cytokine that is abundant in the TME and was mainly produced by NK/NKT cells within NRAS/AKT tumors (Fig. S4, F and G). Our flow cytometry analysis revealed that GM-CSF induced SiglecF expression on BM neutrophils (Fig. S4 H). More importantly, in the presence of GM-CSF, BM neutrophils that were exposed to LA, but not PA or AA, upregulated c-Myc expression (Fig. 7 K) and increased the ability to produce TGFβ upon LPS stimulation (Fig. 7 L). RNA-seq analysis confirmed that GM-CSF and LA synergistically induced SiglecFhi TANs-associated gene signature in neutrophils through a c-Myc–mediated manner (Fig. 7 M). To further assess their functionality, we co-injected these in vitro–conditioned neutrophils with RIL175 cells into C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 7 N). As expected, GM-CSF and LA-conditioned neutrophils expedited tumor growth; however, this effect was abrogated when the Myc inhibitor 10058-F4 was added during in vitro conditioning, or when the TGFβ receptor was knocked-down in RIL175 cells (Fig. 7 O). Together, these data identified GM-CSF and LA as the key factors initiating the c-Myc–TGFβ axis in pro-tumorigenic TANs. It is noteworthy that while GM-CSF and LA induced c-Myc activation in neutrophils prior to their infiltration into tumors, they failed to do so in SiglecF− TANs (Fig. 7 K; and Fig. S4, I and J). Investigating this phenomenon, the pseudotime analysis predicted a branching in TAN development after entry into the tumor (Fig. S4 K). Furthermore, a phenotype switch between SiglecF− TANs and SiglecFhi TANs was not observed in an adoptive transfer assay (Fig. S4 L), suggesting that these two TAN subsets might originate from distinct differentiation pathways. Of note, GM-CSF and LA were unable to induce c-Myc expression and TGFβ production in BM neutrophils isolated from naïve mice (Fig. S4, M and N). Thus, a combination of GM-CSF, lipids, and additional tumor factors activates a c-Myc–dependent transcriptional program and facilitates neutrophil differentiation into protumor SiglecFhi TANs with TGFβ producing ability.

SiglecFhi TANs directly suppress HCC antigenicity via TGFβ

Surgical resection is the only curative treatment for HCC; however, it is often an unviable option as most HCC patients are diagnosed at later stages of the disease. In such cases of advanced HCC, primary treatment options typically include sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that suppresses tumor proliferation and angiogenesis, or anti-PD-1/PD-L1–based combination immunotherapy, which reinvigorates the body’s antitumor immune response (Gallage et al., 2021). Given the protumorigenic effects of SiglecFhi TANs, we asked whether their presence could impede the effectiveness of these therapeutic strategies. To investigate this, we reanalyzed the RNA-seq data from pretreatment tumors collected in the IMbrave150 and GO30140 clinical trials, which involved HCC patients treated with either sorafenib or combination immunotherapy with atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) and bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) (Zhu et al., 2022). A total of 295 patients were included, with 247 receiving atezolizumab/bevacizumab and 48 treated with sorafenib, representing one of the most comprehensive transcriptional collections for prognostic analysis of HCC treatment. Interestingly, Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature was associated with treatment failure among the immunotherapy-treated patients, but not the sorafenib-treated patients (Fig. 8 A). This led us to hypothesize that SiglecFhi TANs may foster a more aggressive HCC phenotype with heightened proliferative activity (Fig. 3), as well as an enhanced ability to evade immune detection. Indeed, SiglecFhi TANs directly suppressed MHCI expression and antigen presentation by RIL175 cells in both in vitro (Fig. 8 B) and in vivo (Fig. S5 A) settings. In line with this, MHCI expression on tumor cells was significantly upregulated following SiglecFhi TAN removal with anti-Ly6G treatment in the NRAS/AKT model (Fig. S5 B). Correspondingly, CD8+TIL effectors in these mice exhibited higher levels of genes related to TCR activation (e.g., Elf1, Zap70, and Ptpn6) compared with those in the control group (Fig. S5, C–E). In HCC patients, we also observed that the antigen processing and presentation signature in tumor cells was inversely correlated with the abundance of Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature (Fig. 8 C) and was decreased in immunotherapy non-responders (Fig. 8 D). Thus, these results suggest that SiglecFhi TANs reduce the antigenicity of tumor cells, rendering them invisible and impervious to attack by cytotoxic T cells. To demonstrate this, we introduced ovalbumin (OVA) as a surrogate tumor antigen in the NRAS/AKT HCC model. We then evaluated tumor antigenicity by examining their surface expression of OVA/MHCI complexes and the antigen recognition by OT-1 cells (Fig. S5 F). SiglecFhi TAN removal significantly enhanced the direct presentation of OVA by tumor cells (Fig. S5 G), without affecting the cross-presentation of OVA by intratumoral dendritic cells (DCs) (Fig. S5 H). Furthermore, adoptively transferred OT-1 cells were more proliferative in mice without SiglecFhi TANs (Fig. S5 I), suggesting improved T cell recognition of tumor cells in these animals compared with their isotype-treated counterparts. To further verify that this increase in OT-1 proliferation was solely due to the difference in antigen load on tumor cells, rather than a distinct TME following SiglecFhi TAN removal, we cultured tumor cells isolated from OVA-NRAS/AKT injected animals with OT-1 cells. Once again, we found that tumor cells from mice without SiglecFhi TANs induced greater OT-1 proliferation in vitro (Fig. S5 J). Next, we set out to demonstrate that SiglecFhi TANs utilized TGFβ to modulate tumor antigenicity. We observed that blocking TGFβ signaling negated the inhibitory effects of SiglecFhi TANs on tumor MHCI expression and antigen presentation (Fig. 8 B and Fig. S5 A). Importantly, tumor cells isolated from Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl mice displayed increased surface expression of OVA/MHCI complexes and were more effective in inducing OT-1 proliferation (Fig. 8, E and F). Collectively, these findings support the notion that SiglecFhi TANs are crucial in driving immunotherapy resistance as they enable immune evasion by limiting the antigenicity of tumor cells via TGFβ.

SiglecF hi TANs downregulate the antigenicity of tumor cells via TGFβ, and their removal sensitizes HCC mice to anti-PD-1 mAb treatment. (A) Distributions of Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature score in HCC patients from the IMbrave150 and GO30140 clinical trials. (B) MHCI expression by IFNγ-treated RIL175 cells co-cultured with SiglecF− or SiglecFhi TANs, with or without Vactosertib (Vac.). (C and D) Antigen processing and presentation signature score was calculated from an imputed tumor-specific gene expression profile (tumor antigen presentation signature) in patients treated with Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab from the IMbrave150 and GO30140 clinical trials. Correlation between tumor antigen presentation signature and Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature scores (C). Distributions of tumor antigen presentation signature score in responder (R) and non-responders (NR) (D). (E and F) OVA-expressing NRAS/AKT HCC was induced in Mrp8Cre+ve.TGFβfl/fl mice (Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl) and Mrp8Cre−ve.TGFβfl/fl littermates (W/T). Representative histograms and OVA/MHCI presentation by tumor cells (E). Tumor cells were co-cultured with OT-1 cells. Representative histograms and proliferation index of OT-1 cells (F). (G and H) NRAS/AKT HCC Mrp8Cre+ve.TGFβfl/fl mice (Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl) and Mrp8Cre−ve.TGFβfl/fl littermates (W/T) were treated with αPD-1 or isotype control mAbs for 2 wk. Representative images of HCC livers and liver-to-body weight ratio. The scale bar represents 1 cm (G). Representative images of AFP+ tumors (brown) and tumor nodule counts. Scale bar represents 100 μm (H). (I) NRAS/AKT HCC mice were treated with isotype control mAbs or αLy6G mAbs or αPD-1 mAbs or both at the indicated time. Survival curve (n = 10/group). (J–Q) Mice were sacrificed 2 wk following treatment. Representative images of HCC livers and liver-to-body weight ratio. Scale bar represents 1 cm (J). Representative images of AFP+ tumors (brown) and tumor nodule counts. Scale bar represents 100 μm (K). MHCI expression on tumor cells (L). Number of CD8+TILs (M). Proportion of PD-1+cells among CD8+TILs (N). Proportion of terminally exhausted cells (PD-1hiCTLA4+Tox+Tcf1−) in CD8+TILs (O). Frequency of Ki-67+ CD8+PD-1+TILs (P). Percentage of CD8+PD-1+TILs co-producing IFNγ and TNFα after in vitro anti-CD3/CD28 restimulation (Q). (R–T) CD8+T cell depletion abrogated the beneficial effects of αLy6G mAb treatment in anti-PD-1 mAb administrated mice. Survival curve (n = 7–10/group) (R). Mice were sacrificed 2 wk following treatments. Liver-to-body weight ratio (S). Tumor nodule counts (T). Each symbol represents TANs isolated from two to three mice (B), one mouse (E, G, H, J–Q, S, and T), or the mean of tumor cells isolated from three mice (F). Data are mean ± SEM and are pooled from three independent experiments (B), or represent two to three independent experiments (E–T). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (A and D), one-way ANOVA (B, G, H, J–Q, S, and T), unpaired Student’s t test (E), two-way ANOVA (F), and Kaplan–Meier analysis (I and R).

SiglecF hi TANs downregulate the antigenicity of tumor cells via TGFβ, and their removal sensitizes HCC mice to anti-PD-1 mAb treatment. (A) Distributions of Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature score in HCC patients from the IMbrave150 and GO30140 clinical trials. (B) MHCI expression by IFNγ-treated RIL175 cells co-cultured with SiglecF− or SiglecFhi TANs, with or without Vactosertib (Vac.). (C and D) Antigen processing and presentation signature score was calculated from an imputed tumor-specific gene expression profile (tumor antigen presentation signature) in patients treated with Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab from the IMbrave150 and GO30140 clinical trials. Correlation between tumor antigen presentation signature and Siglecf-Hi–like TAN signature scores (C). Distributions of tumor antigen presentation signature score in responder (R) and non-responders (NR) (D). (E and F) OVA-expressing NRAS/AKT HCC was induced in Mrp8Cre+ve.TGFβfl/fl mice (Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl) and Mrp8Cre−ve.TGFβfl/fl littermates (W/T). Representative histograms and OVA/MHCI presentation by tumor cells (E). Tumor cells were co-cultured with OT-1 cells. Representative histograms and proliferation index of OT-1 cells (F). (G and H) NRAS/AKT HCC Mrp8Cre+ve.TGFβfl/fl mice (Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl) and Mrp8Cre−ve.TGFβfl/fl littermates (W/T) were treated with αPD-1 or isotype control mAbs for 2 wk. Representative images of HCC livers and liver-to-body weight ratio. The scale bar represents 1 cm (G). Representative images of AFP+ tumors (brown) and tumor nodule counts. Scale bar represents 100 μm (H). (I) NRAS/AKT HCC mice were treated with isotype control mAbs or αLy6G mAbs or αPD-1 mAbs or both at the indicated time. Survival curve (n = 10/group). (J–Q) Mice were sacrificed 2 wk following treatment. Representative images of HCC livers and liver-to-body weight ratio. Scale bar represents 1 cm (J). Representative images of AFP+ tumors (brown) and tumor nodule counts. Scale bar represents 100 μm (K). MHCI expression on tumor cells (L). Number of CD8+TILs (M). Proportion of PD-1+cells among CD8+TILs (N). Proportion of terminally exhausted cells (PD-1hiCTLA4+Tox+Tcf1−) in CD8+TILs (O). Frequency of Ki-67+ CD8+PD-1+TILs (P). Percentage of CD8+PD-1+TILs co-producing IFNγ and TNFα after in vitro anti-CD3/CD28 restimulation (Q). (R–T) CD8+T cell depletion abrogated the beneficial effects of αLy6G mAb treatment in anti-PD-1 mAb administrated mice. Survival curve (n = 7–10/group) (R). Mice were sacrificed 2 wk following treatments. Liver-to-body weight ratio (S). Tumor nodule counts (T). Each symbol represents TANs isolated from two to three mice (B), one mouse (E, G, H, J–Q, S, and T), or the mean of tumor cells isolated from three mice (F). Data are mean ± SEM and are pooled from three independent experiments (B), or represent two to three independent experiments (E–T). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (A and D), one-way ANOVA (B, G, H, J–Q, S, and T), unpaired Student’s t test (E), two-way ANOVA (F), and Kaplan–Meier analysis (I and R).

αLy6G mAb treatments downregulate the antigenicity of tumor cells and activates CD8 + TILs in HCC-bearing C57BL/6J mice, while HCC-bearing Mrp8 Cre .TGFβ fl/fl mice respond to αPD-1 mAb treatment. (A) SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs were adoptively transferred alongside OVA-expressing RIL175 (left) or RIL175_shTgfbr1 cells (right). OVA/MHCI presentation by tumor cells. (B) Representative histograms and MHCI expression on NRAS/AKT tumor cells following αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments. (C) UMAP of tumor infiltrating CD8+T cells (CD8+TILs) in NRAS/AKT-injected C57BL/6J mice treated with αLy6G or Isotype mAbs. (D) Distribution of marker genes in different CD8+TIL subsets. (E) Expression of T cell receptor signaling related genes within the Teff_CD8 subset. (F–J) OVA-expressing NRAS/AKT HCC tumors were used to assess tumor antigen presentation and T cell recognition following αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments. Schematic outline of the experiment (F). Representative histograms and OVA/MHCI presentation by tumor cells (G). OVA/MHCI presentation by tumor-infiltrating CD11c+MHCII+ DCs (H). Proliferation of OT-1 cells 3 days after adoptive transfer into OVA-NRAS/AKT HCC mice (I). Tumor cells from OVA-NRAS/AKT HCC mice were co-cultured with OT-1 cells at the indicated ratios for 3 days. Representative histograms and proliferation index of OT-1 cells (J). (K–P) NRAS/AKT HCC was induced in Mrp8Cre+ve.TGFβfl/fl mice (Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl) and Mrp8Cre−ve.TGFβfl/fl littermates (W/T), followed by treatment with αPD-1 or isotype control mAbs. MHCI expression on tumor cells (K). Number of TCRβ+CD8+TILs per gram of HCC tissue (L). Proportion of PD-1+ cells among TCRβ+CD8+TILs (M). Frequency of proliferating TCRβ+CD8+PD-1+TILs determined by Ki-67 staining (N). Proportion of terminally exhausted cells (PD-1hiCTLA4+Tox+Tcf1−) among TCRβ+CD8+TILs (O). Percentage of TCRβ+CD8+PD-1+TILs co-producing IFNγ and TNFα after in vitro anti-CD3/CD28 restimulation (P). Each symbol represents one mouse (A, B, G–I, and K–P), or the mean of tumor cells isolated from three mice (J). Data are mean ± SEM and represent two to three independent experiments (A, B, and G–P). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (A, B, and G–I), two-way ANOVA (J), and one-way ANOVA (K–P).

αLy6G mAb treatments downregulate the antigenicity of tumor cells and activates CD8 + TILs in HCC-bearing C57BL/6J mice, while HCC-bearing Mrp8 Cre .TGFβ fl/fl mice respond to αPD-1 mAb treatment. (A) SiglecF− and SiglecFhi TANs were adoptively transferred alongside OVA-expressing RIL175 (left) or RIL175_shTgfbr1 cells (right). OVA/MHCI presentation by tumor cells. (B) Representative histograms and MHCI expression on NRAS/AKT tumor cells following αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments. (C) UMAP of tumor infiltrating CD8+T cells (CD8+TILs) in NRAS/AKT-injected C57BL/6J mice treated with αLy6G or Isotype mAbs. (D) Distribution of marker genes in different CD8+TIL subsets. (E) Expression of T cell receptor signaling related genes within the Teff_CD8 subset. (F–J) OVA-expressing NRAS/AKT HCC tumors were used to assess tumor antigen presentation and T cell recognition following αLy6G or isotype control mAbs treatments. Schematic outline of the experiment (F). Representative histograms and OVA/MHCI presentation by tumor cells (G). OVA/MHCI presentation by tumor-infiltrating CD11c+MHCII+ DCs (H). Proliferation of OT-1 cells 3 days after adoptive transfer into OVA-NRAS/AKT HCC mice (I). Tumor cells from OVA-NRAS/AKT HCC mice were co-cultured with OT-1 cells at the indicated ratios for 3 days. Representative histograms and proliferation index of OT-1 cells (J). (K–P) NRAS/AKT HCC was induced in Mrp8Cre+ve.TGFβfl/fl mice (Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl) and Mrp8Cre−ve.TGFβfl/fl littermates (W/T), followed by treatment with αPD-1 or isotype control mAbs. MHCI expression on tumor cells (K). Number of TCRβ+CD8+TILs per gram of HCC tissue (L). Proportion of PD-1+ cells among TCRβ+CD8+TILs (M). Frequency of proliferating TCRβ+CD8+PD-1+TILs determined by Ki-67 staining (N). Proportion of terminally exhausted cells (PD-1hiCTLA4+Tox+Tcf1−) among TCRβ+CD8+TILs (O). Percentage of TCRβ+CD8+PD-1+TILs co-producing IFNγ and TNFα after in vitro anti-CD3/CD28 restimulation (P). Each symbol represents one mouse (A, B, G–I, and K–P), or the mean of tumor cells isolated from three mice (J). Data are mean ± SEM and represent two to three independent experiments (A, B, and G–P). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (A, B, and G–I), two-way ANOVA (J), and one-way ANOVA (K–P).

SiglecFhi TAN removal sensitizes immunotherapy-resistant HCC to anti-PD-1 mAb treatment

Finally, we asked whether the absence of SiglecFhi TANs could restore the efficacy of anti-PD-1 mAb treatment. In line with clinical observations that MASH-related HCC patients are notoriously resistant to immunotherapy (Haber et al., 2021; Pfister et al., 2021), NRAS/AKT-injected WT mice were unresponsive to anti-PD-1 mAb treatment. However, this treatment deficit was reversed in Mrp8Cre.TGFβfl/fl mice (Fig. 8, G and H; and Fig. S5, K–P), highlighting the key role of functional TANs in driving anti-PD-1 mAb therapy resistance. Similarly, SiglecFhi TAN removal with anti-Ly6G mAb also sensitized NRAS/AKT-injected WT mice to anti-PD-1 mAb therapy, resulting in enhanced tumor control and a more significant survival benefit compared with using anti-Ly6G mAb alone (Fig. 8, I–K). This enhanced anti-tumor effect was driven by the increased immune sensitivity of tumor cells, which expressed higher levels of MHCI upon receiving the anti-Ly6G/anti-PD-1 mAb combination therapy (Fig. 8 L). Correspondingly, the number of CD8+TILs increased in mice treated under this condition (Fig. 8 M). Interestingly, these CD8+TILs contained a high percentage of PD-1+ cells (Fig. 8 N); however, the proportion of exhausted cells remained the same (Fig. 8 O). This suggests that the increased presence of PD-1+cells signified elevated TCR stimulation rather than exhaustion. In support of this, CD8+PD-1+cells in mice treated with the anti-Ly6G/anti-PD-1 mAb combination therapy were more proliferative (Fig. 8 P) and secreted higher levels of effector cytokines (Fig. 8 Q). Hence, the synergy between anti-Ly6G mAb and anti-PD-1 mAb injections was predictably dependent on CD8+T cells, as their depletion with anti-CD8 mAb eliminated the treatment benefits (Fig. 8, R–T). Altogether, these results indicate that SiglecFhi TAN removal improves tumor cell recognition by rejuvenating CD8+TILs after anti-PD-1 treatment, thus enhancing the effectiveness of tumor immunotherapy.

Discussion

Several studies have explored the pathogenic role of TANs in HCC (Geh et al., 2022; He et al., 2015; Leslie et al., 2022; Li et al., 2015; van der Windt et al., 2018; Xue et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2019), but few have examined the influence of etiology in this context, despite each HCC subtype having its own distinct pathogenesis. Our comprehensive analysis of 924 HCC patients from four public datasets revealed that the impact of TANs on disease progression is not uniform across different HCC subtypes. Notably, TANs had a more detrimental effect on MASH-related HCC than on viral-related HCC. This variation was attributed to differences in the TAN subsets emerging from these distinct TMEs. Specifically, we identified a unique subset of pro-tumor TANs that was preferentially enriched in MASH-related HCC tumors. These TANs were characterized by an elevated SiglecF expression, a c-Myc–driven transcriptional signature, and a remarkable capacity to produce TGFβ. A lipid-rich TME was crucial for the development of SiglecFhi TANs, endowing them with multiple tumor-promoting functions, such as stimulating tumor cell proliferation and promoting EMT. Beyond these well-known TAN functions, we uncovered that SiglecFhi TANs could further promote HCC aggressiveness by suppressing tumor antigen presentation via the release of TGFβ. This new insight expands our knowledge of the multifaceted roles that TANs play in tumorigenesis and holds significant implications for the advancement of cancer immunotherapy.

ICB therapy serves as the first-line treatment for advanced HCC patients; however, its efficacy is considerably limited in MASH-related HCC patients compared to those with other etiologies (Haber et al., 2021; Pfister et al., 2021). Our findings suggest that the preferential enrichment of SiglecFhi TANs in MASH-related HCC and their impact on tumor immunogenicity may account for these clinical observations. Successful ICB responses require rejuvenated CD8+T cells to recognize their targets through the presentation of tumor antigens via MHCI on tumor cells. In our study of ICB-treated HCC patients, we observed that tumor cells from non-responders displayed a lower antigen presentation signature than those from responders. Likewise, the inactivation of antigen presentation by tumor cells has been identified as a cause of ICB therapy failure in many other tumors (Jhunjhunwala et al., 2021; Montesion et al., 2021; Sade-Feldman et al., 2017). In these cases, point mutations, deletions, or loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) and HLA-I are the primary contributors to antigen presentation defects. However, the prevalence of genetic alterations in B2M and HLA-I is relatively low in HCC patients (e.g., the proportion of patients with at least one incidence of HLA LOH in HCC, melanoma, and cervical cancer is 4%, 14%, and 38% respectively) (Montesion et al., 2021; Pyke et al., 2022), indicating that HCC may employ non-genetic strategies to modulate its immunogenicity. In support of this notion, we demonstrated that a high abundance of SiglecFhi TANs reduced antigen presentation by downregulating MHCI in tumor cells, thereby helping them to evade T cell recognition. Notably, SiglecFhi TANs did not completely abolish MHCI expression on tumor cells, which could otherwise result in natural killer cell-mediated tumor killing. More importantly, TAN depletion sensitized an otherwise ICB-resistant MASH-related murine HCC model to the therapy. Collectively, these findings establish SiglecFhi TAN–mediated MHCI downregulation as a key immune evasion event that confers ICB therapy resistance in MASH-related HCC and highlights the need to target this subset of TANs for immunotherapy efficacy improvements.