While membrane proteins such as ion channels continuously turn over and require replacement, the mechanisms of specificity of efficient channel delivery to appropriate membrane subdomains remain poorly understood. GJA1-20k is a truncated Connexin43 (Cx43) isoform arising from translation initiating at an internal start codon within the same parent GJA1 mRNA and is requisite for full-length Cx43 trafficking to cell borders. GJA1-20k does not have a full transmembrane domain, and it is not known how GJA1-20k enables forward delivery of Cx43 hemichannels. Here, we report that a RPEL-like domain at the C terminus of GJA1-20k binds directly to actin and induces an actin phenotype similar to that of an actin-capping protein. Furthermore, GJA1-20k organizes actin within the cytoplasm to physically outline a forward delivery pathway for microtubule-based trafficking of Cx43 channels to follow. In conclusion, we find that the postal address of membrane-bound Cx43 channel delivery is defined by a separate protein encoded by the same mRNA of the channel itself.

Introduction

Most eukaryotic cells have distinctive organization and polarity, which includes their membrane-bound ion channels that localize to a particular and usually characteristic regional subdomain of their surrounding lipid bilayer. However, a longstanding and still unanswered question in cell biology is the mechanism by which these proteins are delivered to their respective subdomains. It remains unknown how membrane proteins are vested with specificity of delivery. Since the concept of intracellular vesicle trafficking was established by Palade (1975), researchers have identified the cellular machinery that delivers newly synthesized proteins to the membrane. Blobel and colleagues identified protein recognition motifs, indicating that proteins could sense that they are at a correct location or organelle once arrived, but not how they get to a particular location (Blobel and Dobberstein, 1975; Gilmore et al., 1982). Schekman, Rothman, Sudhof, and colleagues identified the machinery for vesicle transport and delivery (Kaiser and Schekman, 1990; Perin et al., 1990; Hata et al., 1993; Söllner et al., 1993; Rothman, 1994). However, it remains an open question how membrane proteins are able to arrive at specific and predetermined subregions on their respective cell membrane.

In many cells, Connexin 43 (Cx43) gap junctions occur with high density at cell–cell borders (Beyer et al., 1987). Cx43 proteins have a short half-life on the order of hours (Beardslee et al., 2000; Jordan et al., 1999), and the gap junctions therefore need to be continuously replenished with newly synthesized proteins delivered in the form of hemichannels (Unwin and Zampighi, 1980). The same short half-life and density at cell–cell borders, as well as cytoskeleton delivery apparatus, occurs in vitro, and cell lines have been used as successful models for Cx43 function and regulation (Fishman et al., 1990; Shaw et al., 2007; Agullo-Pascual et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2020), indicating commonality of trafficking behavior. Cx43 gap junctions are critical in many organ systems such as the heart, where they maintain electrical coupling between adjacent cardiomyocytes for each and every successful heartbeat (Shaw and Rudy, 1997). The system of Cx43 hemichannel delivery must be robust and rapid to avoid diminished cell–cell coupling and, in the heart, the occurrence of fatal arrhythmias (Saffitz et al., 2007; Kléber and Rudy, 2004).

Microtubules serve as tracks to deliver Cx43 to the cell membrane via a highly regulated process, whereby the microtubule tip protein interacts with key membrane components to deliver cargo to specific subdomains (Shaw et al., 2007; Patel et al., 2014). Disruption of microtubule delivery mechanics causes a decrease in Cx43 gap junction formation and can result in the development of diseases such as arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (Patel et al., 2014). While microtubules are the trafficking highways for Cx43 (Shaw et al., 2007), actin has been identified as a necessary upstream mediator in this process due to its ability to shape and guide the microtubule routes (Smyth et al., 2012). The actin cytoskeleton is a dynamic structure that is subject to modification by actin-binding proteins that alter its morphology and affect function. Earlier studies have identified critical roles of actin in Cx43 trafficking, finding that stabilized actin filaments organize microtubules for the targeted delivery of Cx43 to the cell border (Basheer et al., 2017) and also that Cx43 vesicles colocalize with non-sarcomeric actin rest stops during transit (Smyth et al., 2012). Thus, actin is both an upstream organizer of microtubule-based delivery as well as a direct participant in the antegrade transport of vesicles carrying membrane proteins. However, it is unknown how actin specifically directs Cx43 hemichannels to the preferred gap junction subdomain of the cell membrane.

Cx43 is encoded by the single coding exon of the gene GJA1, and therefore it has only one variant of coding mRNA. There are no Cx43 splice variants. However, the single form of Cx43 mRNA is subject to internal translation, whereby internal AUG methionine sequences function as ribosomal start sites, generating N terminus–truncated isoforms (Smyth and Shaw, 2013; Salat-Canela et al., 2014). GJA1-20k, the most abundantly expressed isoform (Smyth and Shaw, 2013), is 20 kDa in size and contains the Cx43 C terminus tail but no full transmembrane domain (Joshi-Mukherjee et al., 2007) (Fig. 1 A). GJA1-20k is an auxiliary subunit of Cx43, which is necessary for full-length Cx43 to be trafficked to gap junction subdomains (Smyth and Shaw, 2013; Xiao et al., 2020). For example, exogenous GJA1-20k can rescue gap junction formation and prevent arrhythmias in a mouse model of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (Palatinus et al., 2023) in which there is a loss of endogenous GJA1-20k. Furthermore, GJA1-20k also has roles in mitochondrial fission and ischemic preconditioning (Fu et al., 2017; Basheer et al., 2018; Shimura et al., 2021). A common denominator of GJA1-20k’s multiple roles is its connection to the actin cytoskeleton. However, no direct interaction between GJA1-20k and actin has been identified. With regard to trafficking, it is not known how GJA1-20k may utilize actin to affect specificity of Cx43 delivery to gap junction membrane domains.

The presence of GJA1-20k results in the formation of actin puncta. (A) Schematic of GJA1 plasmid designs used in overexpression experiments. Internal translation of truncated isoforms does not occur in plasmids where methionines (green) are mutated to leucines (red). (B) Representative live-cell confocal images of the actin cytoskeleton, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in HeLa cells expressing either 0.5 µg of GJA1-20k-GFP or GST-GFP; scale bars = 5 µm. (C) Representative live-cell confocal images of the actin cytoskeleton, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in HeLa cells expressing either GJA1-WT (1 µg), GJA1-43k-GFP (1 µg) + GST-GFP (0.5 µg), or GJA1-43k-GFP (1 µg) + GJA1-20k-GFP (0.5 µg); scale bars = 5 µm. (D) Quantification of actin puncta density of all HeLa transfection conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 100–200 cells per group from four independent experiments). ****P < 0.0001 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test (GST-GFP and GJA1-20k) or by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons with Bonferroni’s post hoc test (GJA1-WT, GJA1-43k, and GJA1-43k + GJA1-20k).

The presence of GJA1-20k results in the formation of actin puncta. (A) Schematic of GJA1 plasmid designs used in overexpression experiments. Internal translation of truncated isoforms does not occur in plasmids where methionines (green) are mutated to leucines (red). (B) Representative live-cell confocal images of the actin cytoskeleton, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in HeLa cells expressing either 0.5 µg of GJA1-20k-GFP or GST-GFP; scale bars = 5 µm. (C) Representative live-cell confocal images of the actin cytoskeleton, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in HeLa cells expressing either GJA1-WT (1 µg), GJA1-43k-GFP (1 µg) + GST-GFP (0.5 µg), or GJA1-43k-GFP (1 µg) + GJA1-20k-GFP (0.5 µg); scale bars = 5 µm. (D) Quantification of actin puncta density of all HeLa transfection conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 100–200 cells per group from four independent experiments). ****P < 0.0001 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test (GST-GFP and GJA1-20k) or by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons with Bonferroni’s post hoc test (GJA1-WT, GJA1-43k, and GJA1-43k + GJA1-20k).

Results

The presence of GJA1-20k results in the formation of actin puncta

To explore whether GJA1-20k influences actin organization, we overexpressed GJA1-20k in HeLa cells (Fig. 1, A and B). HeLa cells contain low levels of endogenous Cx43 and GJA1-20k (Basheer et al., 2017) and are sufficiently flat to allow live cell imaging of spatial trafficking pathways. A LifeAct-mCherry peptide was used to visualize the dynamic actin cytoskeleton. GJA1-20k expression induces thickened actin filaments, as previously observed (Basheer et al., 2017). However, by using a focal plane at cytoplasmic subcortical regions immediately below the plasma membrane, we also identified that GJA1-20k expression induces a population of actin, which is arranged not in fibers but in rounded puncta. These puncta are not present in GST-transfected negative control cells (Fig. 1 B). The discoid and compact form of the actin puncta suggests that GJA1-20k does more than just stabilize actin fibers.

We tested whether the appearance of actin puncta is specific to the GJA1-20k isoform of Cx43. HeLa cells were transfected with a wild-type Cx43 (GJA1-WT) plasmid that encodes full-length Cx43 and all downstream internally translated isoforms, including GJA1-20k, and compared with cells transfected with a full-length plasmid that does not contain internal start sites (GJA1-43k) (schematic in Fig. 1 A), and therefore does not produce any of the smaller isoforms (Smyth and Shaw, 2013). Actin puncta were present in cells expressing GJA1-WT but not GJA1-43k. The puncta in GJA1-43k–treated cells were rescued with concurrent GJA1-20k expression (Fig. 1 C), identifying GJA1-20k as sufficient and, relative to GJA1-43k, necessary for puncta formation. Using an automated analysis algorithm that quantifies actin puncta in each cell, we found that GJA1-20k expression results in a 10-fold increase in the spatial density of actin puncta (Fig. 1 D).

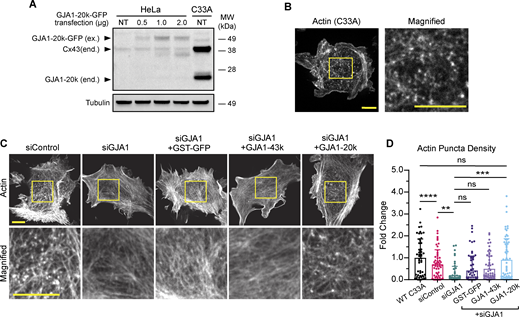

We also explored whether the actin puncta are generated by endogenous GJA1-20k. C33A cells, which have high baseline levels of endogenous GJA1-20k (Salat-Canela et al., 2014), were used. Immunoblotting confirmed that endogenous GJA1-20k is produced by C33A cells (Fig. 2 A). Imaging using LifeAct to visualize actin revealed similar actin puncta in C33A cells (Fig. 2 B), as seen with exogenous GJA1-20k (Fig. 1 B). We then used siRNA-targeting GJA1 to knock down the expression of all GJA1 origin proteins and observed a reduction in the number of actin puncta (Fig. 2, C and D). Addition of a GST negative control or full-length Cx43 did not rescue the actin puncta; however, exogenous GJA1-20k expression did result in the reappearance of puncta (Fig. 2, C and D).

Endogenous GJA1-20k expression results in the formation of actin puncta. (A) Western blot comparison of exogenous (ex.) GJA1-20k-GFP in HeLa cells and endogenous (end.) Cx43 and GJA1-20k in non-transfected (NT) C33A cells. HeLa cells were either NT or transfected with 0.5, 1, or 2 µg of GJA1-20k-GFP (predicted band size for GJA1-20k-GFP = 47 kDa). (B) Representative live-cell confocal imaging of actin, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in a wild-type C33A cell; scale bars = 10 µm. (C) Representative live-cell confocal imaging of actin, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in C33A cells after treatment with either control siRNA or siRNA-targeting GJA1 alone or with post siRNA knockdown expression of 0.5 µg of either GST-GFP, GJA1-43k-GFP, or GJA1-20k-GFP; scale bars = 10 µm. (D) Quantification of actin puncta density for all C33A transfection cell conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 50–65 cells per group from three independent experiments). ns = P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

Endogenous GJA1-20k expression results in the formation of actin puncta. (A) Western blot comparison of exogenous (ex.) GJA1-20k-GFP in HeLa cells and endogenous (end.) Cx43 and GJA1-20k in non-transfected (NT) C33A cells. HeLa cells were either NT or transfected with 0.5, 1, or 2 µg of GJA1-20k-GFP (predicted band size for GJA1-20k-GFP = 47 kDa). (B) Representative live-cell confocal imaging of actin, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in a wild-type C33A cell; scale bars = 10 µm. (C) Representative live-cell confocal imaging of actin, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in C33A cells after treatment with either control siRNA or siRNA-targeting GJA1 alone or with post siRNA knockdown expression of 0.5 µg of either GST-GFP, GJA1-43k-GFP, or GJA1-20k-GFP; scale bars = 10 µm. (D) Quantification of actin puncta density for all C33A transfection cell conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 50–65 cells per group from three independent experiments). ns = P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

GJA1-20k inhibits actin polymerization

The formation of actin puncta (Fig. 1, B–D and Fig. 2, B–D) suggests that polymerization is being inhibited in the presence of GJA1-20k. Our previous studies have found that GJA1-20k also stabilizes actin filaments (Basheer et al., 2017; Shimura et al., 2021), indicating that GJA1-20k could be an actin interacting protein that induces both stabilized actin filaments and isolated puncta. By way of precedent, actin-capping proteins are a class of actin-binding proteins, which induce similar dual phenotypes of strengthening fibers but also limiting polymerization (Caldwell et al., 1989; Wear et al., 2003). Barbed end–capping proteins block (cap) the fast growing end of actin (Wear et al., 2003), preventing filament elongation by blocking the addition of new actin subunits while also stabilizing already polymerized filaments by slowing barbed subunit dissociation (Kovar et al., 2003; Kueh et al., 2008; Tang and Brieher, 2013; Edwards et al., 2014). We used the eponymously named capping protein (CP) as a positive phenotypic control (Caldwell et al., 1989; Cooper and Sept, 2008). HeLa cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding the alpha and beta subunits of CP (Wear et al., 2003), which resulted in the appearance of the actin puncta similar to those induced by GJA1-20k (Fig. 3, A and B).

GJA1-20k inhibits actin polymerization. (A) Representative live-cell confocal imaging of actin, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in a HeLa cell expressing 0.5 µg of CP plasmid; scale bars = 10 µm. (B) Quantification of actin puncta density for HeLa cells transfected with GST-GFP, CP, or GJA1-20k-GFP. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 50–100 cells per group from three independent experiments). P > 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (C) Representative TIRFM images (t = 15 min after initiation of polymerization) of cell-free Alexa Fluor 488–labeled actin in the presence of increasing concentrations of purified CP (alpha and beta subunits); scale bar = 5 µm. Reduction in actin polymerization is quantified by total fluorescence (A.U.) (D) Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 experiments per concentration). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with comparison to the actin only group with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (E) Representative TIRFM images (t = 15 min after initiation of polymerization) of cell-free Alexa Fluor 488–labeled actin in the presence of increasing concentrations of GJA1-20k; scale bars = 5 µm. Reduction in actin polymerization is quantified by total fluorescence (A.U.) (F) Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 independent experiments per concentration) **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with comparison to the actin only group with Bonferroni’s post hoc test.

GJA1-20k inhibits actin polymerization. (A) Representative live-cell confocal imaging of actin, visualized by LifeAct-mCherry, in a HeLa cell expressing 0.5 µg of CP plasmid; scale bars = 10 µm. (B) Quantification of actin puncta density for HeLa cells transfected with GST-GFP, CP, or GJA1-20k-GFP. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 50–100 cells per group from three independent experiments). P > 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (C) Representative TIRFM images (t = 15 min after initiation of polymerization) of cell-free Alexa Fluor 488–labeled actin in the presence of increasing concentrations of purified CP (alpha and beta subunits); scale bar = 5 µm. Reduction in actin polymerization is quantified by total fluorescence (A.U.) (D) Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 experiments per concentration). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with comparison to the actin only group with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (E) Representative TIRFM images (t = 15 min after initiation of polymerization) of cell-free Alexa Fluor 488–labeled actin in the presence of increasing concentrations of GJA1-20k; scale bars = 5 µm. Reduction in actin polymerization is quantified by total fluorescence (A.U.) (F) Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 independent experiments per concentration) **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with comparison to the actin only group with Bonferroni’s post hoc test.

CP and other capping proteins directly bind to actin (Wear et al., 2003). To explore the effects of GJA1-20k on actin dynamics, we utilized time-lapse total internal reflection microscopy (TIRFM) imaging employing purified cell-free actin. This reductionist system allows us to visualize actin dynamics in the presence of other purified proteins, giving us the ability to assess for direct protein–protein interaction. The purified CP was used as a positive control, and we imaged actin after incubation with a range of CP concentrations. Consistent with previous studies of CP (Huang et al., 2003; Kovar et al., 2003; Dutta et al., 2017), increased CP concentration results in actin puncta with decreased linear actin filament formation (Fig. 3, C and D). Repeating the assay with the purified recombinant GJA1-20k, we found that GJA1-20k, like CP, results in a dose-dependent increase in actin puncta and a decrease in linear actin filaments formation (Fig. 3, E and F). In these cell-free experiments, we note that the puncta appear just as they did in the cytoplasm of our cell experiments. The cell-free polymerization phenotype of GJA1-20k is also remarkably similar to that of CP (Fig. 3). We confirmed, using a cell-free actin depolymerization assay, that GJA1-20k stabilizes preformed F-actin filament against latrunculin A–induced depolymerization (Fig. S1 A), also consistent with a capping protein phenotype (Wear et al., 2003). Co-sedimentation of GJA1-20k and F-actin confirmed that GJA1-20k does not bind to the side of the actin filaments (Fig. S1 B), providing further evidence that GJA1-20k is likely binding as a cap to the filament ends.

GJA1-20k does not decorate the sides of actin filaments and inhibits actin depolymerization. (A) F-actin (2 μM, 5% pyrene labeled) was depolymerized with the addition of 10 μM latrunculin A (LatA) in the presence (cross marks) or absence (circles) of 0.9 μM GJA1-20k. F-actin without LatA does not depolymerize (triangles). (B) In high-speed pelleting assays with F-actin (0–30 μM), the amount of GJA1-20k (0.7 μM) in supernatant fractions does not change as the concentration of F-actin is increased, which indicates the lack of side binding to actin filaments. Co-sedimentation results are shown as a gel (top) and densities which were quantified and plotted (bottom). The intensity of GJA1-20k band in the supernatant lacking actin was set as 1 (100%). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

GJA1-20k does not decorate the sides of actin filaments and inhibits actin depolymerization. (A) F-actin (2 μM, 5% pyrene labeled) was depolymerized with the addition of 10 μM latrunculin A (LatA) in the presence (cross marks) or absence (circles) of 0.9 μM GJA1-20k. F-actin without LatA does not depolymerize (triangles). (B) In high-speed pelleting assays with F-actin (0–30 μM), the amount of GJA1-20k (0.7 μM) in supernatant fractions does not change as the concentration of F-actin is increased, which indicates the lack of side binding to actin filaments. Co-sedimentation results are shown as a gel (top) and densities which were quantified and plotted (bottom). The intensity of GJA1-20k band in the supernatant lacking actin was set as 1 (100%). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Structural modeling of the interaction between GJA1-20k and actin

We sought to identify the actin-binding domain on GJA1-20k. While we could not identify homology between GJA1-20k and CP sequences, there is a well-defined actin-binding motif, the RPEL domain (Miralles et al., 2003), of which there is a similar sequence at the C terminus tail of GJA1-20k. RPEL binds to the same cleft in actin as does CP (Carlier et al., 2015). The RPEL domain is defined as containing a key RPxxxEL motif, which is conserved in known actin-binding proteins such as myocardin-related transcription factor (MAL/MRTF-A) and the Phactr family of PP1-binding proteins (Guettler et al., 2008; Mouilleron et al., 2008, 2012). The last nine amino acids of GJA1-20k (RPRPDDLEI) (Fig. 4 A) contain a RPEL-like motif. This motif has two RP sequences and an isoleucine substituted for the terminal leucine (compared with the canonical RPxxxEL sequence).

Structural modeling of the interaction between GJA1-20k and actin. (A) Illustration of Cx43 and GJA1-20k featuring the translation start sites for both the GJA1-20k and GJA1-11k isoforms and the sequence of the final nine amino acids (RPRPDDLEI). (B) Modeling of GJA1-20k (PDB ID: 1R5S) docked to actin. In tan: GJA1-20k ATTRACT models docked using F-actin (PDB ID: 2ZWH), in light blue: GJA1-20k models docked using G-actin (PDB ID: 1J6Z), highlighted in purple: RPRPDDLEI tail sequence of GJA1-20k, red and black text in zoomed in box: hotspot residues as defined by Robetta computational alanine scanning. Hotspots are identified by calculating the free energy change (ΔΔG > 1) after a residue is mutated to alanine. (C) Chart of hotspot residues on actin (red) and GJA1-20k (light blue) as defined by Robetta computational alanine scanning. (D) RPEL domain sequences of Cx43, MAL, MRTF-A, and Phactr1. (E) ATTRACT docking modeling of GJA1-20k (light blue and tan) compared with known RPEL domains of Phactr1 and MRTF-A. In orange: MAL-RPEL2 (PDB ID: 2V52), in pale blue: Phactr1-RPEL1 (PDB ID: 4B1W), in silver: Phactr1-RPEL2 (PDB ID: 4B1X), in yellow: Phactr1-RPEL3 (PDB 1D: 4B1Y); in light green: Phactr1-RPELN (PDB 1D: 4B1U), and in dark blue: full Phactr1 RPEL domain (PDB 1D: 4B1Z).

Structural modeling of the interaction between GJA1-20k and actin. (A) Illustration of Cx43 and GJA1-20k featuring the translation start sites for both the GJA1-20k and GJA1-11k isoforms and the sequence of the final nine amino acids (RPRPDDLEI). (B) Modeling of GJA1-20k (PDB ID: 1R5S) docked to actin. In tan: GJA1-20k ATTRACT models docked using F-actin (PDB ID: 2ZWH), in light blue: GJA1-20k models docked using G-actin (PDB ID: 1J6Z), highlighted in purple: RPRPDDLEI tail sequence of GJA1-20k, red and black text in zoomed in box: hotspot residues as defined by Robetta computational alanine scanning. Hotspots are identified by calculating the free energy change (ΔΔG > 1) after a residue is mutated to alanine. (C) Chart of hotspot residues on actin (red) and GJA1-20k (light blue) as defined by Robetta computational alanine scanning. (D) RPEL domain sequences of Cx43, MAL, MRTF-A, and Phactr1. (E) ATTRACT docking modeling of GJA1-20k (light blue and tan) compared with known RPEL domains of Phactr1 and MRTF-A. In orange: MAL-RPEL2 (PDB ID: 2V52), in pale blue: Phactr1-RPEL1 (PDB ID: 4B1W), in silver: Phactr1-RPEL2 (PDB ID: 4B1X), in yellow: Phactr1-RPEL3 (PDB 1D: 4B1Y); in light green: Phactr1-RPELN (PDB 1D: 4B1U), and in dark blue: full Phactr1 RPEL domain (PDB 1D: 4B1Z).

To determine whether the RPEL-like motif in GJA1-20k translates into predicted actin-binding behavior, we used ATTRACT (de Vries et al., 2015) to model in silico GJA1-20k docking on actin. Utilizing computational flexible protein–protein docking, we visualized the tail sequence of GJA1-20k docking into the actin RPEL-binding cleft utilizing an existing NMR structure of the Cx43 C terminus (Sorgen et al., 2004) as GJA1-20k (Fig. 4 B). Each model was then processed by Robetta alanine scanning, a computational alanine mutagenesis software package (Kortemme and Baker, 2002; Kortemme et al., 2004), in order to quantify the stability of the interaction with actin. Seven hotspot residues on actin and two hotspot residues on GJA1-20k were identified. A hotspot residue was defined by an ability to destabilize the complex when residues are mutated to alanine (Fig. 4, C and D), thereby identifying critical residues for binding. These results provide computational support that the particular RPEL-like sequence of GJA1-20k can create a stable complex with actin. We compared the GJA1-20k RPEL-like motif to the sequences (Fig. 4 D) and structures (Fig. 4 E) of known actin-binding proteins that contain the RPEL domain. Our modeling demonstrates that the tail of GJA1-20k can align into the RPEL-binding actin cleft in a configuration similar to that of other RPEL proteins (Fig. 4 E). Together, these in silico results illustrate a stable interaction between GJA1-20k and actin via its last nine amino acids of the GJA1-20k C terminus.

We sought biochemical confirmation of the modeling data. The full GJA1-20k sequence contains a downstream internal methionine which translates into an even smaller Cx43 isoform with a molecular weight of 11 kDa, GJA1-11k (Smyth and Shaw, 2013; Epifantseva et al., 2020). Like GJA1-20k, GJA1-11k retains the RPEL-like motif in the C-terminal tail (Fig. 4 A). GJA1-11k is a Cx43 isoform that localizes to the nucleus (Epifantseva et al., 2020), so we investigated whether GJA1-11k expression alone can bias actin localization to the nucleus due to their direct interaction. As predicted, with GJA1-11k overexpression in HeLa cells there is an increase in nuclear actin retention when assayed by both cytochemistry with fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5 A) and biochemical (Fig. 5, B and C) techniques.

The RPEL-like tail of GJA1-20k is sufficient to inhibit actin polymerization. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of actin (phalloidin) and nuclei (Hoechst) in HeLa cells transfected with 0.5 µg of GJA1-11k-V5; scale bar = 10 µm. (B) Representative western blotting of actin in nuclear and cytoplasmic subcellular fractions of HeLa cells transfected with 0.5 µg of either GJA1-11k-V5 or a GFP-V5–negative control. Lamin-B1 was used as a loading control for the nuclear fraction and tubulin was used as a loading control for the cytoplasmic fraction. (C) Quantification of western blots of actin density in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fraction of HeLa cells transfected with either GJA1-11k-V5 or GFP-V5, normalized to either Lamin-B1 (nucleus) or tubulin- (cytoplasm) loading controls. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 separate independent fractionation experiments) *P < 0.05 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (D) Representative TIRFM images of cell-free Alexa Fluor 488–labeled actin in the presence of increasing concentrations of the αCT11 peptide (RPRPDDLEI) or a reverse control (IELDDPRPR); scale bar = 5 µm. Reduction in actin polymerization is quantified by total fluorescence (A.U.) (E) Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5 independent experiments per concentration). ns = P > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by multiple t tests comparing the αCT11 peptide to the reverse control for each concentration with Holm–Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. No significant difference was found between the actin only group and the reverse control groups (all concentrations), ns = P > 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. (F) Representative TIRFM images of Alexa Fluor 488–labeled actin (green) in the presence of 250 nM of Alexa Fluor 555–labeled αCT11 (red) or reverse control (red) to show colocalization (merge); scale bar = 5 µm, images taken 2–3 min after the initiation of polymerization. Images were quantified by using Pearson’s correlation to measure colocalization. (G) Data are presented as box and whisker plots with boxes showing median, 25th, and 75th percentile, with whiskers spanning the 10th to 90th percentile (n = 35 frames from three independent experiments) *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

The RPEL-like tail of GJA1-20k is sufficient to inhibit actin polymerization. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of actin (phalloidin) and nuclei (Hoechst) in HeLa cells transfected with 0.5 µg of GJA1-11k-V5; scale bar = 10 µm. (B) Representative western blotting of actin in nuclear and cytoplasmic subcellular fractions of HeLa cells transfected with 0.5 µg of either GJA1-11k-V5 or a GFP-V5–negative control. Lamin-B1 was used as a loading control for the nuclear fraction and tubulin was used as a loading control for the cytoplasmic fraction. (C) Quantification of western blots of actin density in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fraction of HeLa cells transfected with either GJA1-11k-V5 or GFP-V5, normalized to either Lamin-B1 (nucleus) or tubulin- (cytoplasm) loading controls. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 separate independent fractionation experiments) *P < 0.05 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (D) Representative TIRFM images of cell-free Alexa Fluor 488–labeled actin in the presence of increasing concentrations of the αCT11 peptide (RPRPDDLEI) or a reverse control (IELDDPRPR); scale bar = 5 µm. Reduction in actin polymerization is quantified by total fluorescence (A.U.) (E) Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5 independent experiments per concentration). ns = P > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by multiple t tests comparing the αCT11 peptide to the reverse control for each concentration with Holm–Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. No significant difference was found between the actin only group and the reverse control groups (all concentrations), ns = P > 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. (F) Representative TIRFM images of Alexa Fluor 488–labeled actin (green) in the presence of 250 nM of Alexa Fluor 555–labeled αCT11 (red) or reverse control (red) to show colocalization (merge); scale bar = 5 µm, images taken 2–3 min after the initiation of polymerization. Images were quantified by using Pearson’s correlation to measure colocalization. (G) Data are presented as box and whisker plots with boxes showing median, 25th, and 75th percentile, with whiskers spanning the 10th to 90th percentile (n = 35 frames from three independent experiments) *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

To explore whether the RPEL-like sequence alone is sufficient to bind to actin, we utilized a peptide which contains the last nine amino acids of GJA1-20k (RPRPDDLEI: (Jiang et al., 2019). This peptide, called α-carboxyl terminus 11 (αCT11), has been identified to be therapeutic in the setting of ischemia-reperfusion (Jiang et al., 2019) and as a mediator of actin reorganization (Chen et al., 2015). We used the αCT11 peptide and a negative control containing the reverse sequence (IELDDPRPR) in the TIRFM cell-free actin assay and found that the αCT11 sequence alone was sufficient to induce actin puncta, which is consistent with its barbed end–capping activity (Fig. 5, D and E). Fluorescently conjugating each peptide for use in TIRFM, we found that αCT11 colocalized with actin significantly more than the reverse control colocalizes with actin (Fig. 5, F and G). The ability of αCT11 to bind actin and suppress actin filament length is also consistent with actin-capping behavior.

To confirm that αCT11 is required for actin-capping activity, we overexpressed HeLa cells with either GJA1-20k or GJA1-20kΔαCT11, which has the RPEL motif from GJA1-20k plasmid deleted, and quantified the density of actin puncta. There is a significant reduction in actin puncta density in the GJA1-20kΔαCT11 study compared with the GJA1-20k study (Fig. S2).

The RPEL-like motif in GJA1-20k patterns Cx43 trafficking to cell–cell borders

As GJA1-20k is a known mediator of Cx43 trafficking to the cell border (Smyth and Shaw, 2013; Basheer et al., 2017; Epifantseva et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020), we asked whether the function of GJA1-20k as an actin-capping protein is significant for Cx43 trafficking. Newly synthesized Cx43 is packaged into vesicles and trafficked directly to the cell border on microtubules (Shaw et al., 2007); however, actin has also been identified as necessary for forward Cx43 trafficking. F-actin filaments can function as pathway scaffolds that direct microtubules patterning toward the cell border (Basheer et al., 2017) as well as “rest-stop” structures at which Cx43 vesicles localize (Smyth et al., 2012). Both actin filament highways and rest stops are needed for delivery of Cx43 gap junctions to the cell–cell border (Smyth et al., 2012; Basheer et al., 2017).

The actin puncta generated by GJA1-20k (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) could correspond to the previously described (Smyth et al., 2012) actin rest stops to pattern microtubule trajectories in the cell. To investigate whether dynamic microtubule trafficking is directed by GJA1-20k–capped actin, microtubule paths were visualized by using a YFP-tagged isoform of the microtubule plus end–tracking protein EB1 (Shaw et al., 2007). Live-cell confocal imaging in HeLa cells was used to obtain videos of fluorescent EB1 comets, as they continually transit from the Golgi apparatus to the cell border at the growing positive termini of microtubules (Shaw et al., 2007). We traced (Tinevez et al., 2017) the trajectory of each EB1 comet to indicate microtubule pathways. The cells expressing tagged EB1 were also transfected with a LifeAct plasmid to visualize the actin cytoskeleton, as well as either GJA1-WT or GJA1-43k (GJA1-WT expresses GJA1-20k, whereas GJA1-43k does not, Fig. S3). As seen in Fig. 6 A, the actin puncta in cells expressing GJA1-20k (GJA1-WT) correspond to the occurrence of microtubule track branching (white arrows) and their presence corresponds to an increase in microtubule track overlay (thickness). Cells not expressing GJA1-20k (GJA1-43k) have less actin puncta (Fig. 6 C), less dense microtubule tracks (Fig. 6 and Fig. S4), and less overlap regions between actin puncta and microtubule branching. This indicates that GJA1-20k organizes actin puncta as sites of actin-microtubule interactions necessary for efficient microtubule-based trafficking of Cx43.

The RPEL-like motif of GJA1-20k facilitates Cx43 trafficking. (A) Representative frame of a live-cell video of a HeLa cell transfected with LifeAct (0.5 µg) to visualize the cytoskeleton and EB1-YFP (0.5 µg) tracks to visualize dynamic microtubule movement. These cells were also expressing GJA1-WT (1 µg) with no fluorescent tag in order to express full-length Cx43 and its downstream isoforms, or GJA1-43k to express full-length Cx43 in the absence of GJA1-20k; scale bars = 10 µm. White arrows indicate location of intracellular actin puncta. (B) Quantification of EB1 local track thickness (n = 13–15 videos, 1 cell per video). *P = 0.0222 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (C) Quantification of actin puncta density for cells in A (n = 15 and 13 cells for GJA1-WT and GJA1-43k). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (D–G) Representative images of Cx43-NT, N-cadherin, and DAPI in HeLa cells transfected with GJA1-WT or GJA1-ΔαCT11 with or without GJA1-20k (GST used as control). Cx43 is located on cell border–labeled N-cadherin (arrowheads) but αCT11 mutation resulted in less trafficking (asterisks). Scale bars, 10 and 5 µm (insets). Cx43 localization is quantified as Cx43 intensity at cell border (E), total Cx43 (F), and Cx43 ratio of border to total (G). n = 47 (GJA1-WT + GST), 45 (GJA1-WT + GJA1-20k), 49 (GJA1-ΔαCT11 + GST), and 47 (GJA1-αCT11 + GJA1-20k) cells from three independent experimental repeats. ns = P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

The RPEL-like motif of GJA1-20k facilitates Cx43 trafficking. (A) Representative frame of a live-cell video of a HeLa cell transfected with LifeAct (0.5 µg) to visualize the cytoskeleton and EB1-YFP (0.5 µg) tracks to visualize dynamic microtubule movement. These cells were also expressing GJA1-WT (1 µg) with no fluorescent tag in order to express full-length Cx43 and its downstream isoforms, or GJA1-43k to express full-length Cx43 in the absence of GJA1-20k; scale bars = 10 µm. White arrows indicate location of intracellular actin puncta. (B) Quantification of EB1 local track thickness (n = 13–15 videos, 1 cell per video). *P = 0.0222 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (C) Quantification of actin puncta density for cells in A (n = 15 and 13 cells for GJA1-WT and GJA1-43k). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (D–G) Representative images of Cx43-NT, N-cadherin, and DAPI in HeLa cells transfected with GJA1-WT or GJA1-ΔαCT11 with or without GJA1-20k (GST used as control). Cx43 is located on cell border–labeled N-cadherin (arrowheads) but αCT11 mutation resulted in less trafficking (asterisks). Scale bars, 10 and 5 µm (insets). Cx43 localization is quantified as Cx43 intensity at cell border (E), total Cx43 (F), and Cx43 ratio of border to total (G). n = 47 (GJA1-WT + GST), 45 (GJA1-WT + GJA1-20k), 49 (GJA1-ΔαCT11 + GST), and 47 (GJA1-αCT11 + GJA1-20k) cells from three independent experimental repeats. ns = P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

GJA1-20k without RPEL motif results in less actin puncta formation compared with GJA1-20k. (A) Representative images of actin puncta formation in HeLa cells transfected with either GJA1-20k or GJA1-20kΔαCT11. Scale bars = 20 and 5 µm (inset). (B) Quantification of actin puncta density in A (n = 113, 127 cells, GJA1-20k, and GJA1-20kΔαCT11, respectively, from three independent experimental repeats). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ****P < 0.0001 with two sample Mann–Whitney U test.

GJA1-20k without RPEL motif results in less actin puncta formation compared with GJA1-20k. (A) Representative images of actin puncta formation in HeLa cells transfected with either GJA1-20k or GJA1-20kΔαCT11. Scale bars = 20 and 5 µm (inset). (B) Quantification of actin puncta density in A (n = 113, 127 cells, GJA1-20k, and GJA1-20kΔαCT11, respectively, from three independent experimental repeats). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ****P < 0.0001 with two sample Mann–Whitney U test.

To confirm the role of endogenous GJA1-20k in regulating microtubule track density, we used siRNA to knock down GJA1 in C33A cells and overexpressed GJA1-20k to test if GJA1-20k can rescue EB1 tracks. Knocking down GJA1 significantly reduced microtubule track thickness, whereas introducing back GJA1-20k successfully rescued this phenotype (Fig. S5, A and B). Interestingly, we did not observe a change in overall tubulin density in any of the tested groups (Fig. S5, C and D), supporting that increased microtubule thickness is a result of increased polymerization rather than tubulin monomer production. Combined with the result of GJA1-WT overexpression in HeLa cells (Fig. 6, A and B), these data indicate that both endogenous and exogenous GJA1-20k regulate microtubule dynamics by enhancing microtubule track density.

GJA1-20k expression by GJA1-WT and GJA1-43k plasmids. Western blot comparison of ex. GJA1-20k-YFP in HeLa cells transfected with 1 μg of either GJA1-WT or GJA1-43k. The result shows that the GJA1-WT plasmid expresses the GJA1-20k isoform, whereas the GJA1-43k plasmid does not. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

GJA1-20k expression by GJA1-WT and GJA1-43k plasmids. Western blot comparison of ex. GJA1-20k-YFP in HeLa cells transfected with 1 μg of either GJA1-WT or GJA1-43k. The result shows that the GJA1-WT plasmid expresses the GJA1-20k isoform, whereas the GJA1-43k plasmid does not. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

We next investigated the role of the actin-organizing RPEL-like sequence in directed Cx43 targeting to cell–cell borders in HeLa cells. In this experiment, we deleted αCT11 from the plasmid encoding GJA1-WT (GJA1-ΔαCT11), which results in the deletion of the terminal αCT11 sequence from both Cx43 and GJA1-20k. The deletion of αCT11 resulted in reduced Cx43 trafficking to the cell–cell border, which is rescued by the introduction of exogenous GJA1-20k (Fig. 6, D–G). Importantly, total Cx43 intensity was not changed by either αCT11 mutation or GJA1-20k treatment, indicating that the overexpression of GJA1-20k contributes to Cx43 trafficking but not Cx43 expression. Collectively, the data in Fig. 6 indicate that the directional movement of EB1-tipped microtubules, which are used to deliver Cx43 (Shaw et al., 2007), is secondary to the actin structures within the cell which are regulated by the presence of GJA1-20k.

GJA1-20k rescues gap junction permeability

We asked if the microtubule-based delivery of Cx43, orchestrated by GJA1-20k, modulates Cx43 gap junction function. We used siRNA to knock down GJA1 in the C33A cells, and exogenously introduced back GJA1-20k and GJA1-43k to explore overall junction permeability. We employed a scrape-loading/dye transfer assay to assess gap junction permeability by recording the intercellular transfer of the fluorescent dye Lucifer yellow via functional gap junction channels. Consistent with increased Cx43 gap junction density, the introduction of GJA1-20k with GJA1-43k improved gap junction permeability as evidenced by increased spread of Lucifer yellow (Fig. 7, A–C), whereas GJA1-43k alone or GJA1-43k with GST did not improve gap junction permeability.

GJA1-20k rescues gap junction permeability in C33A cells with GJA1 knockdown. (A) Images of cells scraped loaded with Lucifer yellow dilithium salt and rhodamine dextran. Each image is the mean of 30–34 individual images from each corresponding group. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Lucifer yellow spreading from the scraping lines from images in A. (C) Normalized areas of dye-coupled cells. Data were calculated by subtracting dextran-positive area from Lucifer yellow–positive area, the result of which was then divided by cut length. n = 30–34 images per group from three independent experimental repeats. Data are presented as box and whisker plots, with boxes showing median, 25th, and 75th percentile, with whiskers spanning the 10th to 90th percentile. ns = P > 0.05, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test and multiple comparisons between each group with GJA1 siRNA. (D) Schematic flowchart summarizing the conclusion from Fig. 6 and Fig. 7. (E) Cx43 vesicles are trafficked on microtubules to the cell border to form Cx43 gap junctions. GJA1-20k expression directly reorganizes intracellular actin to produce an increased amount of actin puncta and stabilized F-actin fibers. Actin puncta, where Cx43 vesicles dock, serve as microtubule rest stops and F-actin fibers orient microtubules toward the cell border. Together, these populations of actin, directly produced by GJA1-20k’s functioning as an actin-capping protein, pattern microtubules to increase Cx43 trafficking, and the subsequent amount of Cx43 gap junctions at the cell border.

GJA1-20k rescues gap junction permeability in C33A cells with GJA1 knockdown. (A) Images of cells scraped loaded with Lucifer yellow dilithium salt and rhodamine dextran. Each image is the mean of 30–34 individual images from each corresponding group. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Lucifer yellow spreading from the scraping lines from images in A. (C) Normalized areas of dye-coupled cells. Data were calculated by subtracting dextran-positive area from Lucifer yellow–positive area, the result of which was then divided by cut length. n = 30–34 images per group from three independent experimental repeats. Data are presented as box and whisker plots, with boxes showing median, 25th, and 75th percentile, with whiskers spanning the 10th to 90th percentile. ns = P > 0.05, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test and multiple comparisons between each group with GJA1 siRNA. (D) Schematic flowchart summarizing the conclusion from Fig. 6 and Fig. 7. (E) Cx43 vesicles are trafficked on microtubules to the cell border to form Cx43 gap junctions. GJA1-20k expression directly reorganizes intracellular actin to produce an increased amount of actin puncta and stabilized F-actin fibers. Actin puncta, where Cx43 vesicles dock, serve as microtubule rest stops and F-actin fibers orient microtubules toward the cell border. Together, these populations of actin, directly produced by GJA1-20k’s functioning as an actin-capping protein, pattern microtubules to increase Cx43 trafficking, and the subsequent amount of Cx43 gap junctions at the cell border.

Discussion

Using both intact cells and cell-free systems, we identify GJA1-20k as a novel actin-capping protein. In addition to previously observed thickened actin filaments in cells expressing GJA1-20k (Basheer et al., 2017), here we report that GJA1-20k expression, whether endogenous or exogenous, results in actin reorganization (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Using TIRFM imaging of actin in a cell-free system, we find that the C terminus of GJA1-20k binds directly to actin and inhibits actin polymerization, resulting in the discoid collections of actin (Fig. 3, E and F). Furthermore, results from pyrene–actin assays indicated that GJA1-20k, while preventing actin polymerization (Fig. 3), is also able to stabilize preformed actin filaments against depolymerization in the presence of a sequestering reagent (Fig. S1 A). These results reconcile the dual actin phenotype of puncta and thickened filaments, suggesting that GJA1-20k can differentially reorganize intracellular actin networks based on the relative availability of actin in monomeric G-actin pools versus filamentous F-actin fibers. Such dual actin phenotypes are reported for established actin-capping proteins (Caldwell et al., 1989; Cooper and Sept, 2008; Edwards et al., 2014).

Previous studies have already identified two populations of actin that are crucial for Cx43 trafficking, finding that Cx43 vesicles in transit to the cell border pause at actin rest stops (Smyth et al., 2012) and that stabilized actin filaments are necessary to scaffold microtubule delivery pathways (Basheer et al., 2017). Our current finding that GJA1-20k caps actin filaments (Fig. 3), explains how GJA1-20k is able to chaperone Cx43 to the cell border by dynamically remodeling the actin cytoskeleton to produce both the actin puncta that serve as vesicle rest stops and the stabilized actin filaments required to pattern the microtubule pathway for Cx43 trafficking (Fig. 6 A). We were able to identify that the RPEL-like actin-binding domain on GJA1-20k is critical for both actin capping (Fig. 5), Cx43 trafficking (Fig. 6, D–G), and Cx43 gap junction functionality (Fig. 7, A–C).

Our results advance a targeted delivery paradigm (Shaw et al., 2007) by providing insight into how a smaller N-truncation isoform of a membrane-bound channel’s alpha protein, formed by translation initiation at an internal site from the same origin mRNA, works with the dynamic cytoskeleton to arrange delivery of the full-length membrane-bound channel. Unlike the full-length Cx43 proteins, which have four transmembrane domains and oligomerize into hexamers with other Cx43 to construct membrane-bound hemichannels, GJA1-20k is smaller and hydrophilic without a transmembrane domain. Thus, the GJA1-20k peptide can move freely and be localized throughout the cytosol. The results of this study indicate that GJA1-20k interacts directly with and organizes the actin cytoskeleton to establish a pathway for subsequent microtubule delivery of the full-length Cx43 channel. The smaller GJA1-20k isoform literally constructs the delivery actin and microtubule highways for full-length channel delivery (Fig. 7 E). With common C termini, the smaller isoforms can also dimerize with the larger parent channels to utilize the network, effectively loading channel-containing vesicles onto the patterned delivery cytoskeleton.

Following transcription and translation, Cx43 is inserted into the membrane of the ER where it undergoes folding and posttranslational modifications. It is then packaged and transported to the Golgi apparatus for further processing and oligomerization. According to canonical trafficking, newly formed hemichannels then exit the TGN through transport intermediates (vesicles and tubular extensions) and are transported to the plasma membrane along microtubule tracks. Once at the cell surface, hemichannels freely diffuse within the lipid bilayer to their final functional destination (Laird, 2006). Our proposed targeted delivery model advances classical trafficking by offering an efficient and direct mechanism for the transport of Cx43 hemichannels to their target locations, which is of utmost importance in polarized cells such as cardiomyocytes, especially considering that disruption of the intercalated disc and alterations in Cx43 localization are core pathological features of several cardiomyopathies (Epifantseva and Shaw, 2018). Targeted delivery relies on three main components: the cytoskeleton delivery apparatus, a membrane anchor, and the channel itself. Previous studies on Cx43 hemichannel trafficking have identified these components to be microtubules, the adherens junction complex, and Cx43, respectively (Shaw et al., 2007). Microtubule growth and orientation is determined by the actin cytoskeleton. GJA1-20k through its actin-binding site is able to stabilize and strengthen actin filaments, promoting actin node formation. Microtubule remodeling occurs secondary to actin remodeling, patterning along the established actin trajectories, and leading to the formation of Cx43-trafficking highways. Consequently, GJA1-20k, by remodeling the cytoskeleton, is able to facilitate Cx43 trafficking to the membrane in a more streamlined and efficient manner (Basheer et al., 2017).

The importance of GJA1-20k in Cx43 trafficking is not only limited to improved Cx43 trafficking efficiency and delivery, but rather it is a core component for successful delivery of Cx43 to its target subdomain in the plasma membrane. For instance, the GJA1M213L/M213L mouse line generated by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing contains a point mutation in the GJA1 gene leading to the substitution of methionine by leucine at codon 213 (M213L). This mutation does not affect transcription of the GJA1 mRNA; however, it results in absent translation of GJA1-20k without affecting full-length Cx43. Mice homozygous for the M213L mutation had significantly reduced gap junction formation at the intercalated discs compared with wild-type or heterozygous mice, indicating impaired forward trafficking. In the absence of GJA1-20k, Cx43 is unable to be transported to the plasma membrane and is instead sequestered in the cytosol leading to its rapid degradation (Xiao et al., 2020).

In myocytes, other capping proteins such as CP are found at the Z-disc where they cap the barbed end of thin filaments (Casella et al., 1987) and are also a key component of cardiac muscle structure (Hart and Cooper, 1999). Gelsolin, a capping protein that, unlike CP and GJA1-20k, also severs actin filaments, has roles in cardiac hypertrophy (Hu et al., 2014) and stress-induced actin remodeling in cardiomyocytes (Patel et al., 2014). While we have identified a role for GJA1-20k as an actin-capping protein in regulating intracellular protein trafficking, the diverse functions of capping proteins highlight more potential roles of GJA1-20k as an actin regulator in the heart.

It should be emphasized that GJA1-20k is a stress response protein that is upregulated after hypoxic stress (Ul-Hussain et al., 2014) and after ischemic injury in the heart (Basheer et al., 2018). Oxidative stress has been shown to disrupt microtubules (Smyth et al., 2010) and actin (Smyth et al., 2012) in the myocardium, directly perturbing the Cx43 delivery machinery, reducing Cx43 gap junctions at the cell border, and increasing adverse cardiac events (Dupont et al., 2001; Saffitz et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2020). Our current study identifies a mechanism for how GJA1-20k physically organizes the cytoskeletal machinery for Cx43 trafficking, both as a direct modulator of actin and as a secondary organizer of the microtubule routes guided by actin toward the cell border (Basheer et al., 2017). These findings regarding Cx43 and GJA1-20k could be a precedent for other membrane proteins using internal translation to generate peptides that form their own cytoskeletal-trafficking highways. These findings can also help explain how GJA1-20k recruits actin to induce protective mitochondrial fission during cellular stress (Shimura et al., 2021).

GJA1-20k upregulation during ischemia could be a cellular attempt to restore trafficking pathways disrupted by injury. Knowledge of how GJA1-20k directly stabilizes actin and the trafficking of Cx43 indicates that GJA1-20k may also be used as a potential therapy for maintaining or restoring Cx43 gap junction coupling in the heart. A recent study (Palatinus et al., 2023) indicates that, unlike ischemic injury, the condition of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy in humans and mice is notable for a decrease in GJA1-20k expression as well as decreased gap junction localization to cell–cell borders. In this instance, GJA1-20k gene therapy in mice rescues Cx43 trafficking and decreases ventricular arrhythmia (Palatinus et al., 2023). GJA1-20k, by rescuing Cx43 localization, may therefore rescue pathological electrical rhythms in genetic diseases that diminish Cx43 trafficking.

Connexin expression at the cell surface is regulated by a balance between biosynthesis, trafficking, and degradation. One critical aspect of connexin regulation is the internalization of gap junction plaques, which undergo a unique form of endocytosis leading to the internalization of the entire gap junction plaque, forming an annular structure (Norris and Terasaki, 2021). Prior studies indicate that Cx43 endocytosis is facilitated by the clathrin-mediated endocytic machinery (Falk et al., 2014; Gumpert et al., 2008). Of note, components of the clathrin-mediated endocytic machinery are able to reorganize the actin cytoskeleton and induce internalization of gap junctions (Piehl et al., 2007; Falk et al., 2016). It is possible that GJA1-20k interaction with actin affects not just forward trafficking but Cx43 internalization as well.

Our current study introduces a mechanism whereby GJA1-20k functions as an actin-capping protein, inducing actin cytoskeleton remodeling through direct binding and remodeling of the cytoskeleton, enhancing Cx43 forward trafficking to regions of microtubule membrane anchors such as cardiac intercalated discs. We look forward to future studies that further delineate the GJA1-20k and actin-mediated life cycle of Cx43-containing vesicles in their peripatetic commute between actin rest stops and along microtubule highways, from Golgi apparatus to cardiac intercalated disc. We also eagerly anticipate exploration of whether GJA1-20k affects actin-mediated Cx43 internalization and degradation as well.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

Low passage HeLa (Cat# CCL-2; ATCC) and C33A (Cat# HTB-31; ATCC) cell lines were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in DMEM (Cat# 21013024; Thermo Fisher Scientific), high glucose with 10% FBS, nonessential amino acids (Cat# 11140050; Thermo Fisher Scientific), sodium pyruvate (Cat# 11360070; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and Mycozap-CL (Cat# VZA-2012; Lonza). For transient transfection experiments, cells were plated 24 h prior to transfection, and the transfection was carried out using FuGENE HD (Cat# E2311; Promega) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Cat# 11668019; Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA interference

We utilized siRNA synthesized to knock down human GJA1 mRNA (sequence 5′ to 3′: 5′-GGGAGAUGAGCAGUCUGCCUUUCGU-3′; Cat# HSS178257; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Stealth RNAi (Cat# 12935112; Thermo Fisher scientific) as a negative control. C33A cells were transfected with 100 nM of either siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Cat# 13778150; Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Further transfections with siRNA-resistant plasmids were performed 24 h after siRNA treatment using FuGENE HD (Cat# E2311; Promega).

Live-cell imaging

Unless otherwise stated, live-cell imaging was performed using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with an ORCA-Flash 4.0 Hamamatsu camera, an okolab incubator set at 37°C, a 100×/1.49 Oil Apo TIRF objective, and a spinning disk confocal unit (Yokogawa) controlled by NIS Elements software (RRID:SCR_014329). In experiments involving actin puncta between GJA1-20k and GJA1-20kΔαCT11 and total tubulin/EB1 in GJA1 knockdown rescue, a CSU-W1 SoRa spinning disk confocal unit with Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope equipped with a Photometrics Prime BSI scientific CMOS camera was used. For excitation, 100 mW diode-pumped solid-state lasers with 405-, 488-, 561-, and 640-nm wavelengths were used.

Cells were plated in 35-mm glass bottom dishes (Cat# P35G-1.5-14-C; MatTek) and transfection and imaging occurred in the same dishes. For imaging, cell media was exchanged for pre-warmed HBSS with 10% FBS.

To visualize the cytoskeleton, cells were transfected with a LifeAct-mCherry plasmid, which was generated (Smyth et al., 2012) using Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen). The LifeAct Entry clone was inserted into the pDEST-mCherry-N1 destination vector (RRID:Addgene_31907) to generate the LifeAct peptide with a C terminus mCherry tag. The GJA1 plasmids used were also generated (Smyth and Shaw, 2013; Basheer et al., 2017) using Gateway cloning technology. Entry clones containing human GJA1 encoding full-length Cx43 and the GJA1-43k and GJA1-20k isoforms were inserted into C-terminal GFP and YFP destination vectors for all experiments, except for nuclear fractionation and Cx43-trafficking experiments, where GJA1-11k and GJA1-20k were inserted into a C-terminal V5 destination vector (Epifantseva et al., 2020). The CP (F-actin–capping protein subunit alpha-1 and F-actin–capping protein subunit beta) plasmid was a gift from Antoine Jégou & Guillaume Romet-Lemonne (#89950; Addgene plasmid).

Microtubule tracking

To visualize microtubules via EB1 tracks, cells were transfected with an EB1-YFP plasmid, which was generated by cloning a PCR fragment containing EB1 into YFP destination vectors (Smyth et al., 2010) using Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen) (plasmid #27382; Addgene). Images were taken every second for one min (60 frames generated per video) and captured as a video. Tracks outlining microtubule trajectories were generated using the ImageJ (RRID:SCR_003070) plugin TrackMate (Tinevez et al., 2017).

To calculate track thickness, the ImageJ plugin local thickness was used (Saito and Toriwaki, 1994; Hildebrand and Rüegsegger, 1997). An image with the Trackmate generated EB1 tracks was converted to grayscale, and the local thickness plugin generated a distance map as shown in Fig. S4. The function distance ridge to local thickness was performed using the local thickness plugin, which then generated a second distance map which removed individual and redundant lines from the image. Intensity was measured from this image using the ImageJ analysis tool.

Co-sedimentation assay

For the high-speed pelleting assay, G-actin was incubated for 3 min in ME buffer (0.05 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 mM EGTA). F-actin was produced by polymerizing G-actin overnight on ice, at 50 μM under KMEH (50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, pH7.0, 0.2 mM ATP, and 1 mM DTT) buffer conditions. GJA1-20k was exchanged into KMEH buffer. F-actin (10–30 μM) and GJA1-20k (0.7 μM) were combined and left to incubate at 25°C for 20 min. Samples were spun at 80,000 rpm at 4°C in a TLA100 rotor. Supernatant and pellet fractions were run on electrophoresis gels and stained with Coomassie dye. Band intensity analysis was done using ImageJ.

Pyrene–actin depolymerization assay

Actin filaments were prepared by polymerizing 10 μM G-actin (50% pyrene labeled) overnight on ice in KMEH buffer. Prior to polymerization, G-actin was incubated in ME buffer for 3 min. F-actin was diluted to 6.25 μM prior to reaction mixing. 10 μM of latrunculin A was added with or without 0.9 μM GJA1-20k (in KMEH buffer), bringing the final concentration of F-actin to 2 μM. Final reaction conditions included KMEH, 1.1% methanol, and 0.2% DMSO. Fluorescence was measured at 365-nm excitation and 407-nm emission with the Varioskan Flash plate reader.

Western blotting

On the day of experiments, cells were scraped and lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM NaF, and 200 μM Na3VO4) supplemented with cOmplete ULTRA Protease Inhibitor Tablets (Cat# 5892791001; Sigma-Aldrich) or Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor (Cat# 78440; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lysates were briefly sonicated with a Fisherbrand Model 120 Sonic Dismembrator and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4°C to eliminate any cell debris. Protein concentration was determined using the BioRad DC Protein Assay. NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Cat# NP0007; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 100 mM DTT was added before subjecting cell lysates to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis using NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels and MES running buffer (Cat# NP000202; Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Gels were then transferred to FluoroTrans PVDF Membranes (BSP0161; Pall). For antibody staining, membranes were blocked at RT in 5% nonfat dry milk (Carnation) in TNT buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20) and probed with primary antibodies in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. Membranes were then incubated with host-matched fluorophore-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1,000, Cat# A-11034, A-21428, A-21245; Invitrogen for Goat anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, 555, 647; Cat# A-11001, A-21422, A-32728 for Goat anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 488, 555, 647; Cat# A-21434, A-11006 for Goat anti-Rat Alexa Fluor 488, 555; and Cat# A-32933 for Goat anti-Chicken Alexa Fluor 647) at RT for 1 h. Western blots were visualized using a ChemiDoc MP (BioRad) and band densities were quantified using ImageJ (Analyze → Gels).

To detect endogenous and exogenous GJA1-20k (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S3), we used the following antibodies diluted in TNT buffer: anti-Cx43 (1:1,000, Cat# Mab3067; Millipore), anti-tubulin (1:5,000, Cat# ab6160; abcam), anti-GFP (1:5,000, Cat# ab13970), and anti-GAPDH (1:2,000, Cat# ab8245).

Generation of local thickness. Demonstration of how EB1 thickness is calculated from EB1 microtubule tracks (GJA1-WT and GJA1-43k images shown are from Fig. 6 A). Representative images from HeLa cells transfected with either GJA1-WT or GJA1-43k to demonstrate how thickness is calculated from EB1 microtubule tracks. The Trackmate plugin was used to track EB1 particle movements (gray). Next, the Local Thickness plugin generates a distance map (center panel) and then the distance ridge is calculated by removing redundant points from the thickness map. The function Distance Ridge to Local Thickness was then performed to create a distance map of the thickest sections of the image (right panel). Intensity was measured from the right panel images to quantify EB1 microtubule track thickness.

Generation of local thickness. Demonstration of how EB1 thickness is calculated from EB1 microtubule tracks (GJA1-WT and GJA1-43k images shown are from Fig. 6 A). Representative images from HeLa cells transfected with either GJA1-WT or GJA1-43k to demonstrate how thickness is calculated from EB1 microtubule tracks. The Trackmate plugin was used to track EB1 particle movements (gray). Next, the Local Thickness plugin generates a distance map (center panel) and then the distance ridge is calculated by removing redundant points from the thickness map. The function Distance Ridge to Local Thickness was then performed to create a distance map of the thickest sections of the image (right panel). Intensity was measured from the right panel images to quantify EB1 microtubule track thickness.

GJA1-20k rescued microtubule track density in C33A cells with GJA1 knockdown. (A) Representative images visualizing microtubule movement tracked by EB1 over one-minute time-lapse imaging, interval = 1s. Scale bar = 5 µm. (B) Quantifications of microtubule track local thickness (n = 35, 27, 24, and 23 cells from Ctrl siRNA, GJA1 siRNA, GJA1 siRNA + GST, and GJA1 siRNA + GJA1-20k, respectively, from three independent experimental repeats). (C) Representative images of C33A cells stained with tubulin Tracker Deep Red. Scale bar = 10 µm. (D) Quantifications of total tubulin density by measuring areas occupied with tubulin Tracker divided by cell areas (n = 92, 64, 83, and 84 cells from Ctrl siRNA, GJA1 siRNA, GJA1 siRNA + GST, and GJA1 siRNA + GJA1-20k, respectively, from three independent experimental repeats). Data are presented by mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 with the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test.

GJA1-20k rescued microtubule track density in C33A cells with GJA1 knockdown. (A) Representative images visualizing microtubule movement tracked by EB1 over one-minute time-lapse imaging, interval = 1s. Scale bar = 5 µm. (B) Quantifications of microtubule track local thickness (n = 35, 27, 24, and 23 cells from Ctrl siRNA, GJA1 siRNA, GJA1 siRNA + GST, and GJA1 siRNA + GJA1-20k, respectively, from three independent experimental repeats). (C) Representative images of C33A cells stained with tubulin Tracker Deep Red. Scale bar = 10 µm. (D) Quantifications of total tubulin density by measuring areas occupied with tubulin Tracker divided by cell areas (n = 92, 64, 83, and 84 cells from Ctrl siRNA, GJA1 siRNA, GJA1 siRNA + GST, and GJA1 siRNA + GJA1-20k, respectively, from three independent experimental repeats). Data are presented by mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 with the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test.

Cell fractionation

For the experiments that required nuclear fractionation, we used the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Cat# 78833; Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, HeLa cells were transfected with either GJA1-11k-V5 or a GFP-V5 control and 24 h after transfection they were harvested with Trypsin-EDTA and pelleted. The nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated by following the manufacturer’s protocol and using the proprietary extraction reagents. The subcellular fractionation lysates were analyzed via western blot. We used the following primary antibodies diluted in TNT buffer: anti-β actin (1:1,000, Cat# A00702; GenScript), anti-lamin B1 (1:1,000, Cat# ab133741; abcam), and anti-tubulin (1:5,000, Cat# ab6160; abcam).

TIRFM cell-free actin assays

TIRFM was conducted using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with a TIRF Oil Apo 100×/1.49 objective and recorded with an iXon Ultra 897 EMCCD Camera (Andor) controlled by NIS Elements Software. Purified His-tagged GJA1-20k protein, CP, αCT11 peptide (RPRPDDLEI), or reverse control (IELDDPRPR), at specified concentrations, were diluted in 1x TIRF buffer (2x TIRF: 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 0.4 mM ATP [Cat# BSA04-001; Cytoskeleton], 100 mM DTT, 30 mM glucose, 40 μg/ml catalase, 200 μg/ml glucose oxidase, and 1% methylcellulose). Alexa-488–conjugated rabbit skeletal muscle G-actin (Life Technologies) was added to start the assay at a final concentration of 1 μM, and the mixture was added to flow chambers that were preincubated with N-Ethylmaleimide–Heavy-Mero-Myosin II (Cytoskeleton, Inc.) and washed with 1% bovine serum albumin (Cat# A9647; Sigma-Aldrich) in high-salt TBS (2x HS-TBS: 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and 1.2 M NaCl) and low-salt TBS (2x LS-TBS: 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and 100 mM NaCL). Once added to the flow chambers, imaging was immediately started with images captured every 10 s for 15 min.

Total fluorescence was calculated using ImageJ. Thresholding was used to highlight actin and remove background fluorescence. Integrated density was then measured and recorded for each sample.

Protein purification

GJA1-20k, CP, and GJA1-20kΔαCT11 were purified for the TIRFM Microscopy Assays. His-tagged GJA1-20k plasmid without the putative transmembrane region (amino acids 236–382 of the full-length human Cx43, National Center for Biotechnology Information reference NP_000156.1) was generated and purified. To create the plasmid, a 6x His tag and linker was fused to the N terminus of the GJA1-20k sequence and cloned into the pET301/CT-DEST vector via Gateway cloning (Cat# K630001; Invitrogen). The primers used to amplify the sequence are (5′–3′) 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAA AAGCAGGCTTCAGGAGGTATACATATGCATCATCATCATCATCACGGTGGTGGCGGTTCAGGCGGAGGTGGCTCTGTTAAGGATCGGGTTAAGGGAAAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCTTACTAATCGTCATCATCGTCATCATCGTCATCATCACTTCCACCACTTCCACCGATCTCCAGGTCATCAGGCCG-3′ (antisense). The protein was expressed in LOBSTR (Kerafast) Escherichia coli competent cells transformed with pTf16 chaperone protein tag (TaKaRa Bio) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

A His-tagged mouse CP (F-actin–capping protein subunit alpha-1 and F-actin–capping protein subunit beta) plasmid was obtained from Addgene as described above (#89950; Plasmid). To generate GJA1-20kΔαCT11, the plasmid encoding His-tagged GJA1-20k, was mutated to delete the last nine amino acids (RPRPDDLEI), using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) as described in the mutagenesis section below. These proteins were expressed in One Shot BL21 (DE3) competent cells (Invitrogen).

All proteins were expressed in E. coli as specified above and protein expression was induced at 37°C with 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-galactopyranoside. The recominant proteins were isolated from bacterial pellets lysed in B-PER Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent (Cat# 89822; Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing cOmplete ULTRA Protease Inhibitor Tablets (Cat# 5892791001; Sigma-Aldrich) using the HisPur Cobalt Purification Kit (Cat# PI-90092; Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s protocol with buffer substitutions (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.0 for column equilibration and washing with the addition of 10 and 20 mM Imidazole for sequential washing steps and 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0, and 10% glycerol for elution). Purified proteins were concentrated and subjected to a buffer exchange into a final buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, and 10% glycerol.

Biotin-tagged peptides of the last nine amino acids of GJA1-20k (αCT11, RPRPDDLEI) and a reverse control (IELDDPRPR) that were also used in the TIRFM Microscopy Assay were synthesized by Anaspec.

Mutagenesis

Mutations to delete the αCT11 region (RPRPDDLEI) of GJA1-20k and GJA1-WT were performed using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Cat# 210513; Agilent) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To mutate GJA1-20k for GJA1-20kΔαCT11 protein production, a plasmid containing the sequence described above was mutated using the primers (5′–3′) 5′-GTCGTGCCAGCAGCGGTGGAAGTGGTGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCACCACTTCCACCGCTGCTGGCACGAC-3′ (antisense).

To mutate GJA1-WT to create GJA1-ΔαCT11 to study trafficking, the GJA1-WT-YFP plasmid was altered using the primers 5′-CAGTCGTGCCAGCAGCAAGCTTCGAATTCTGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCAGAATTCGAAGCTTGCTGCTGGCACGACTG-3′ (antisense).

TIRFM cell-free actin assay with fluorescently conjugated proteins

For TIRFM experiments that required fluorescent conjugation, the proteins or peptides (GJA1-20k, GJA1-20kΔαCT11, αCT11, and IELDDPRPR) were fluorescently conjugated using the Alexa Fluor 555 Microscale Protein Labeling Kit (Cat# A30007; Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

The fluorescently conjugated proteins were used in the TIRFM cell-free actin assay at a concentration of 250 nM. The TIRFM cell-free actin assay was performed as described above and 15 images on different areas of the slide were captured within 2–3 min after the start of polymerization.

Quantification of colocalization was performed with ImageJ, using the JACoP (Just Another Colocalization Plugin) plugin.

Quantification of actin puncta density

We generated a novel image analysis macro to quantify the number of actin puncta per cell area. Actin was imaged in HeLa or C33A cells, using a LifeAct plasmid, via live-cell confocal imaging and then each condition was blinded for analysis. Using ImageJ for the analysis, each cell was selected and individually outlined, within the cortical actin border and the outside was cleared. A macro was then run to subtract the background using a rolling ball radius of 50 pixels, the actin puncta were highlighted using an auto threshold to highlight the subcortical actin. The analyze particles function was then run with a size exclusion criterion of 0.03–0.58 μm and a circularity setting of 0.4–1.0 to exclude actin filaments and only detect circular actin puncta. The analyze particles count was then normalized to the area of each cell.

Immunofluorescence staining

To image actin in the nucleus, cells were transfected with either GJA1-11k-V5 or GFP-V5 and fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min at RT, 24 h after transfection. The fixed cells were then permeabilized in 0.1% Triton in PBS and blocked in 5% goat serum for 1 h at RT. The cells were then incubated in phalloidin (1:1,000, Cat# P3457; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The nuclei were then stained with Hoechst 33342 (1:2,000, Cat# 62249; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min at RT.

To image Cx43 vesicle association with actin in C33A cells, the cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked as described above. The cells were then incubated with anti-Cx43-NT (1:500, Cat# AP11568PU-N; Origene) and phalloidin (1:1,000, Cat# P3457; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 1% goat serum in PBS. The following day, the samples were washed with PBS and incubated with Goat anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1,000, Cat# A-11034; Invitrogen) for 1 h at RT.

Cx43 delivery to cell–cell border

HeLa cells were cultured and transfected as described above. 24 h after transfection, cells were washed with PBS formulated with magnesium and calcium (Cat# 14040117; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and fixed in 4% PFA in PBS formulated with magnesium and calcium for 20 min at RT. The cells were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton in PBS and blocked in 5% goat serum for 1 h at RT. The following primary antibodies were diluted in 1% goat serum in PBS: anti-Cx43-NT (1:500, Cat# AP11568PU-N; Origene), N-cadherin (1:500, Cat# 610921; BD Biosciences), and the fixed cells were incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The next day, the samples were washed with PBS and incubated with host-matched secondary fluorescently conjugated antibodies (1:1,000, Cat# A-11034; Invitrogen, for Goat anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 and Cat# A-32728 for Goat anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 647) for 1 h at RT. After washing the secondary antibodies off with PBS, the samples were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Cat# P36935; SouthernBiotech) for 20 min at RT.

For quantification of Cx43 at the cell border, N-cadherin at cell membrane was traced using ImageJ threshold and particle analysis to create cell border masks. Cx43 signal intensity was calculated in the masked region and compared between groups.

Protein modeling

Flexible protein–protein docking was performed using the ATTRACT docking program (de Vries et al., 2015). For actin, PDB ID: 2ZWH and PDB ID: 1J6Z were both used in two different runs. For GJA1-20k, PDB ID: 1R5S was used. This PDB file is an ensemble of 10 lowest energy structures of the C terminus of Cx43, all of which were used in each run. HADDOCK (Dominguez et al., 2003; van Zundert et al., 2016) was used to generate harmonic distance restraints in .tbl format to use as parameters for ATTRACT. Ambiguous restraints were generated with R124, P125, R126, P127, L130, E131, and I132 defined as active residues (directly involved in the interaction) and D128 and D129 defined as passive residues (surrounding surface residues). On actin, Y169, a known binding site for RPEL proteins (Mouilleron et al., 2012), was defined as an active residue. After this information was parsed through ATTRACT, the top 10 models of both actin PDB IDs used were parsed through and models found in most common orientation of GJA1-20k were selected as top models. UCSF Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004) was used for visualization of all structures (color, ribbons, and orientation).

Computational alanine scanning

For the selected models, Robetta alanine scanning (Kortemme and Baker, 2002; Kortemme et al., 2004) was used in order to identify hotspot residues on both actin and GJA1-20k in each predicted interaction. Chain 1 was identified as actin and chain 2 was identified as GJA1-20k. Any residue that was identified as having >1ΔΔG(complex) when mutated to alanine is defined as a hotspot residue.

Scrape-loading/dye transfer