Here, we report that the RTN3L–SEC24C endoplasmic reticulum autophagy (ER-phagy) receptor complex, the CUL3KLHL12 E3 ligase that ubiquitinates RTN3L, and the FIP200 autophagy initiating protein, target mutant proinsulin (Akita) condensates for lysosomal delivery at ER tubule junctions. When delivery was blocked, Akita condensates accumulated in the ER. In exploring the role of tubulation in these events, we unexpectedly found that loss of the Parkinson’s disease protein, PINK1, reduced peripheral tubule junctions and blocked ER-phagy. Overexpression of the PINK1 kinase substrate, DRP1, increased junctions, reduced Akita condensate accumulation, and restored lysosomal delivery in PINK1-depleted cells. DRP1 is a dual-functioning protein that promotes ER tubulation and severs mitochondria at ER–mitochondria contact sites. DRP1-dependent ER tubulating activity was sufficient for suppression. Supporting these findings, we observed PINK1 associating with ER tubules. Our findings show that PINK1 shapes the ER to target misfolded proinsulin for RTN3L–SEC24C–mediated macro-ER-phagy at defined ER sites called peripheral junctions. These observations may have important implications for understanding Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a continuous membrane structure consisting of two main domains: flat sheets that largely reside near the nucleus and a polygonal tubular network that extends to the cortex (Chen et al., 2013; Shibata et al., 2006). This unique morphology is maintained by the reticulons (RTN), atlastins (ATL), and Lunapark (LNPK), ER shaping proteins that regulate the formation of the tubular network (Chen et al., 2013; Shibata et al., 2006). The reticulons promote membrane curvature via a reticulon homology domain (RHD), while the atlastins mediate tubule fusion (Chen et al., 2013; Shibata et al., 2006). LNPK stabilizes newly formed tubule junctions that form at the site where two tubules fuse (Chen et al., 2015). In the absence of LNPK, junctions and tubules decrease, and consequently ER sheets proliferate (Chen et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). ER shape is important for maintaining cell health as mutations in ER shaping proteins have been linked to neurodegenerative disorders, including hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSP) (Chen et al., 2013).

The ER is the site of synthesis for secretory and membrane proteins that traffic within the cell (Chen et al., 2013). Newly synthesized proteins are packaged into COPII transport carriers at specialized ER subdomains called ER exit sites (ERES) and then transported to the Golgi (Gomez-Navarro and Miller, 2016). The formation of COPII transport carriers is initiated when the GTPase SAR1 recruits the SEC24–SEC23 complex to ER membranes to sort cargo into a prebudding complex (Gomez-Navarro and Miller, 2016). Four different SEC24 isoforms sort cargo into COPII transport carriers, SEC24A, SEC24B, SEC24C, and SEC24D (Tang et al., 1999). The SEC24–SEC23 complex also recruits a second coat complex to the prebudding complex, SEC13–SEC31, which then leads to GTP hydrolysis and the release of a COPII transport carrier (Gomez-Navarro and Miller, 2016). When defects in protein biogenesis occur, misfolded and unassembled proteins are retrotranslocated across the membrane via ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) machinery and destroyed in the cytosol by the proteasome (Sun and Brodsky, 2019; Wu and Rapoport, 2018). Many disease-causing, aggregation-prone proteins, however, are inefficiently degraded by ERAD and a resistant population remains in the ER. ER-autophagy (ER-phagy) is an alternate degradative system that removes this ERAD-resistant population (Chino and Mizushima, 2020; Ferro-Novick et al., 2021; Mochida and Nakatogawa, 2022; Wilkinson, 2020).

ER-phagy is mediated by receptors that link ER domains in tubules or sheets to the autophagy machinery (Ferro-Novick et al., 2021). Autophagy receptors bind to lipidated Atg8 family members (called LC3 or GABARAP in mammals) via an LC3-interacting region (LIR) (Johansen and Lamark, 2020). ER-phagy can be autophagosome-mediated (macro-ER-phagy) or non-autophagosome-mediated (micro-ER-phagy and vesicular delivery) (Chino and Mizushima, 2020; Ferro-Novick et al., 2021). During macro-ER-phagy, the receptor binds to lipidated Atg8 to sequester an ER fragment into a double membrane vesicle, called an autophagosome, that is delivered to the lysosome for degradation (Chino and Mizushima, 2020; Ferro-Novick et al., 2021). In micro-ER-phagy, tubule fragments are directly engulfed by the lysosome (Liao et al., 2024; Loi et al., 2019). Recently, a trafficking pathway that delivers single membrane vesicles to the lysosome has also been described (Fregno et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2023). The FIP200-containing autophagy initiation complex, which is required for autophagosome biogenesis, is needed for macroautophagy but not microautophagy or vesicular delivery to the lysosome (Fregno et al., 2018; Hara et al., 2008; Liao et al., 2024; Loi et al., 2019; Omari et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2023).

The reticulon ER-phagy receptor RTN3L and the sheets receptor FAM134B contain an RHD (Chen et al., 2013; Shibata et al., 2006). A RHD is a hairpin membrane insertion sequence that facilitates membrane bending (Chen et al., 2013; Shibata et al., 2006). Ubiquitination within the FAM134B RHD has recently been reported to enhance its oligomerization and membrane-bending activity (González et al., 2023). FAM134B and RTN3L are also related to the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) reticulon-like ER-phagy receptor Atg40 (Khaminets et al., 2015; Mochida et al., 2015; Parashar et al., 2021). Atg40 works with the COPII coat complex, Lst1-Sec23, to package ER into autophagosomes at ER-phagy sites (ERPHS). ERPHS are distinct from the ERES where COPII vesicles bud from the ER (Cui et al., 2019).

In mammalian cells, ERPHS can be visualized in the tubular network with Akita, an ERAD-resistant mutant form of proinsulin that causes early-onset diabetes (Cunningham et al., 2019; Parashar et al., 2021). Misfolded Akita condensates colocalize with RTN3L-containing puncta that also contain SEC24C–SEC23 (mammalian Lst1-Sec23) and LC3B (Parashar et al., 2021). ERAD-resistant misfolded pro-opiomelanocortin (C28F POMC) and pro-arginine-vasopressin (G57S Pro-AVP) behave similarly to Akita (Cunningham et al., 2019; Parashar et al., 2021). While much is known about COPII-mediated cargo sorting and vesicle formation, where and how ERPHS are formed and the machinery that regulates their formation is unknown. Here, we report that ERPHS are formed at a distinct subdomain of the tubular network, LNPK-marked three-way tubule junctions. We found that FIP200, RTN3L, its binding partner SEC24C, and the E3 ligase CUL3KLHL12 are needed to retain misfolded Akita condensates in ERPHS at tubule junctions prior to their delivery to lysosomes. RTN3L is ubiquitinated by CUL3KLHL12, which is recruited to LNPK-marked junctions where RTN3L accumulates. In exploring the role of peripheral tubules and junctions in ER-phagy, we unexpectedly found that the Parkinson’s disease kinase PINK1 regulates ER-phagy by shaping the peripheral ER. PINK1, which is known to regulate mitochondrial morphology and mitophagy, localizes to the mitochondria and ER–mitochondria contact sites (Gómez-Suaga et al., 2018). Corroborating the new role for the PINK1 kinase that we describe here, PINK1 was found to associate with ER tubules. In total, these studies explain how the RTN3L–SEC24C pathway targets ERAD-resistant proteins for macro-ER-phagy at spatially defined sites at the cell periphery whose formation is regulated by PINK1.

Results

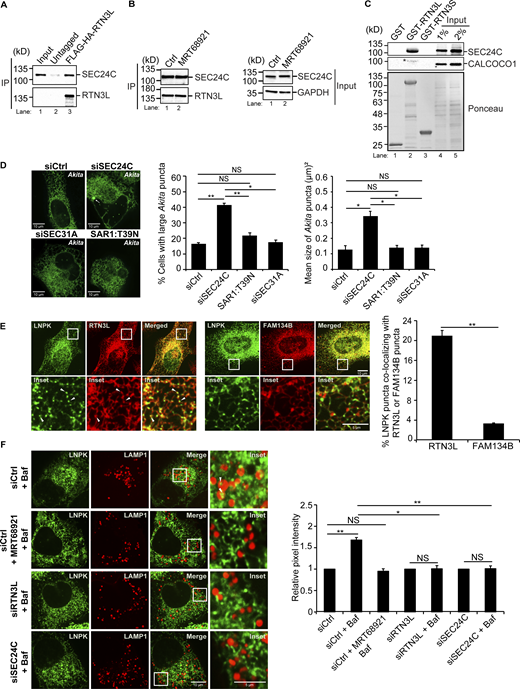

RTN3L binds to SEC24C in the absence of LC3 lipidation

To begin our analysis, we performed coprecipitation experiments to ask if the interaction of RTN3L with SEC24C requires lipidated LC3. For these studies, we used MRT68921, an autophagy inhibitor that efficiently impairs LC3 lipidation (see Fig. S10 A, right) and autophagosome maturation by disrupting ULK1 kinase activity (Petherick et al., 2015; Zachari et al., 2020). We found that the endogenous copy of SEC24C coprecipitated with RTN3L from cells stably expressing FLAG-HA-RTN3L, but not untagged cells (Fig. 1 A and Fig. S1 A, left). Furthermore, SEC24C coprecipitated equally as efficiently with RTN3L in untreated or MRT68921-treated cells (Fig. 1 B). The precipitate contained the SEC24C binding partner, SEC23A (Fig. S1 A, middle), but not SEC24A (Fig. S1 A, right), a SEC24 paralog that does not act in ER-phagy (Parashar et al., 2021). These results are consistent with previous studies showing that the induction of autophagy with the TORC1 inhibitor, Torin 2, leads to the colocalization of RTN3L puncta with SEC24C, but not other SEC24 paralogs (SEC24A) (Parashar et al., 2021). The delivery of RTN3L to lysosomes during basal cell growth was inhibited by MRT68921 and dependent on SEC24C, while SEC24C lysosomal delivery was RTN3L-dependent (Fig. S1, B–D and Fig. S2). The lysosomal delivery of the tubule marker, RTN4, was also significantly impaired in RTN3L-and SEC24C-depleted cells (Fig. S1 D and Fig. S3). As RTN3L coprecipitates with SEC24C and the lysosomal delivery of RTN3L and SEC24C are dependent on each other, these data imply that RTN3L and SEC24C are delivered together as a complex to lysosomes. Lysosomal delivery, but not RTN3L–SEC24C complex formation, appears to require LC3 lipidation.

The RTN3L–SEC24C receptor complex mediates traffic to lysosomes from ER junctions independent of COPII vesicle traffic. (A) Lysates were prepared from cells treated with Bafilomycin A1 (Baf) for 4 h and incubated with anti-HA-agarose beads. Input is 0.2% of the lysate. SEC24C inputs were equal (see Fig. S1 A). A 6.56 increase in SEC24C was present in the FLAG-HA-RTN3L precipitate compared with the untagged control. (B) Same as A only, control (Ctrl) cells were treated with Baf or Baf + MRT68921 for 4 h. There was 1.21 × more SEC24C in lane 2 when compared to lane 1 (set to 1.00). The data was normalized to RTN3L levels. (C) In vitro binding experiments performed with lysates prepared from rich or nutrient starved cells yielded the same results. Cells were grown in rich media for the data shown. Asterisk (*) marks a contaminating band. (D) siCtrl, SAR1:T39N transfected cells and siRNA-treated cells were transfected with Akita-sfGFP. The percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2), and the mean size of Akita puncta are reported. Arrow marks a puncta that was quantitated. (E) Cells were transfected with LNPK–GFP and mCherry–RTN3L or mCherry–FAM134B. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta. (F) Cells were untreated or treated with Baf or Baf + MRT68921 (6 h). The relative pixel intensity is reported for images on the left and Fig. S5 B. Arrowheads mark LNPK-GFP puncta colocalizing with LAMP1-mCherry structures. The Ctrl for each condition was without Baf (DMSO) and set to 1.0. Error bars (D–F) represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 62 to 101 cells in D, 58–61 cells in E, and 63–87 cells for F and Fig. S5 B. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

The RTN3L–SEC24C receptor complex mediates traffic to lysosomes from ER junctions independent of COPII vesicle traffic. (A) Lysates were prepared from cells treated with Bafilomycin A1 (Baf) for 4 h and incubated with anti-HA-agarose beads. Input is 0.2% of the lysate. SEC24C inputs were equal (see Fig. S1 A). A 6.56 increase in SEC24C was present in the FLAG-HA-RTN3L precipitate compared with the untagged control. (B) Same as A only, control (Ctrl) cells were treated with Baf or Baf + MRT68921 for 4 h. There was 1.21 × more SEC24C in lane 2 when compared to lane 1 (set to 1.00). The data was normalized to RTN3L levels. (C) In vitro binding experiments performed with lysates prepared from rich or nutrient starved cells yielded the same results. Cells were grown in rich media for the data shown. Asterisk (*) marks a contaminating band. (D) siCtrl, SAR1:T39N transfected cells and siRNA-treated cells were transfected with Akita-sfGFP. The percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2), and the mean size of Akita puncta are reported. Arrow marks a puncta that was quantitated. (E) Cells were transfected with LNPK–GFP and mCherry–RTN3L or mCherry–FAM134B. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta. (F) Cells were untreated or treated with Baf or Baf + MRT68921 (6 h). The relative pixel intensity is reported for images on the left and Fig. S5 B. Arrowheads mark LNPK-GFP puncta colocalizing with LAMP1-mCherry structures. The Ctrl for each condition was without Baf (DMSO) and set to 1.0. Error bars (D–F) represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 62 to 101 cells in D, 58–61 cells in E, and 63–87 cells for F and Fig. S5 B. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Related toFig. 1,. SAR1:T39N does not block the delivery of misfolded Akita to lysosomes. (A) SEC24C coprecipitates with RTN3L. Left, inputs showing that equal amounts of SEC24C were used for the IP in Fig. 1 A. Right, same as Fig. 1 A only the samples were blotted for SEC23A and SEC24A. (B) RTN3 depletion experiments performed in this study were done with two different siRNAs, siRTN3 (directed at a site in the reticulon domain, see details in the Materials and methods) and siRTN3L (directed at two sites in the long domain, see details in the Materials and methods). The same results were obtained with both siRNAs. Western blot analysis was performed using cell lysates treated with siRTN3 and siRTN3L. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) RNAi resistant mCherry-RTN3L suppresses the accumulation of large Akita-sfGFP puncta (≥0.5 µm2) in RTN3-depleted cells. Representative images (left) and quantitation of cells with large Akita puncta (right) are shown. Arrows mark large puncta. (D) Western blot analysis was performed using cells treated with siRTN3L, siSEC24C, siCALCOCO1 (left), and siSEC31A (right). GAPDH was used as a loading control. The depletion of RTN3L did not alter the expression of SEC24C or CALCOCO1. (E) Quantitation of Akita-sfGFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in DMSO treated or Baf treated (3.5 h) cells that were untransfected (Ctrl) or transfected with SAR1:T39N. Arrowheads mark Akita puncta delivered to lysosomes. The data was quantitated as described in the methods. (F) siCtrl, SAR1:T39N, and siRNA-treated cells were transfected with Proinsulin-sfGFP. The percent cells with Proinsulin-sfGFP puncta (≥0.35 µm2) are reported. Arrows mark puncta that were quantitated. Error bars in C, E, and F represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 29 to 53 cells in C, 65–76 cells in E, and 74–149 cells in F. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Related toFig. 1,. SAR1:T39N does not block the delivery of misfolded Akita to lysosomes. (A) SEC24C coprecipitates with RTN3L. Left, inputs showing that equal amounts of SEC24C were used for the IP in Fig. 1 A. Right, same as Fig. 1 A only the samples were blotted for SEC23A and SEC24A. (B) RTN3 depletion experiments performed in this study were done with two different siRNAs, siRTN3 (directed at a site in the reticulon domain, see details in the Materials and methods) and siRTN3L (directed at two sites in the long domain, see details in the Materials and methods). The same results were obtained with both siRNAs. Western blot analysis was performed using cell lysates treated with siRTN3 and siRTN3L. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) RNAi resistant mCherry-RTN3L suppresses the accumulation of large Akita-sfGFP puncta (≥0.5 µm2) in RTN3-depleted cells. Representative images (left) and quantitation of cells with large Akita puncta (right) are shown. Arrows mark large puncta. (D) Western blot analysis was performed using cells treated with siRTN3L, siSEC24C, siCALCOCO1 (left), and siSEC31A (right). GAPDH was used as a loading control. The depletion of RTN3L did not alter the expression of SEC24C or CALCOCO1. (E) Quantitation of Akita-sfGFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in DMSO treated or Baf treated (3.5 h) cells that were untransfected (Ctrl) or transfected with SAR1:T39N. Arrowheads mark Akita puncta delivered to lysosomes. The data was quantitated as described in the methods. (F) siCtrl, SAR1:T39N, and siRNA-treated cells were transfected with Proinsulin-sfGFP. The percent cells with Proinsulin-sfGFP puncta (≥0.35 µm2) are reported. Arrows mark puncta that were quantitated. Error bars in C, E, and F represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 29 to 53 cells in C, 65–76 cells in E, and 74–149 cells in F. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Related to Fig. 1 . RTN3L and SEC24C are delivered to lysosomes during basal autophagy. (A) Ctrl or SEC24C-depleted cells were treated for 4 h with Baf or Baf + MRT68921. Arrowheads mark RTN3L fragments delivered to lysosomes. The relative pixel intensity for each condition is the mean intensity of YFP-RTN3L in the pixels that overlap with LAMP1-mCherry for the images shown. The control for each condition was without Baf (DMSO only) and set to 1.0. MRT68921 was used to block autophagosome formation. (B) Same as A, only cells were depleted of RTN3L and the delivery of YFP-SEC24C to lysosomes was examined. Arrowheads mark SEC24C in lysosomes. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 84 to 112 cells in A, and 88–128 in B. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test.

Related to Fig. 1 . RTN3L and SEC24C are delivered to lysosomes during basal autophagy. (A) Ctrl or SEC24C-depleted cells were treated for 4 h with Baf or Baf + MRT68921. Arrowheads mark RTN3L fragments delivered to lysosomes. The relative pixel intensity for each condition is the mean intensity of YFP-RTN3L in the pixels that overlap with LAMP1-mCherry for the images shown. The control for each condition was without Baf (DMSO only) and set to 1.0. MRT68921 was used to block autophagosome formation. (B) Same as A, only cells were depleted of RTN3L and the delivery of YFP-SEC24C to lysosomes was examined. Arrowheads mark SEC24C in lysosomes. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 84 to 112 cells in A, and 88–128 in B. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test.

Related to Fig. 1 . RTN3L and SEC24C are needed for the delivery of RTN4 fragments to lysosomes during basal autophagy. siCtrl, siRTN3L, siSEC24C, and siCALCOCO1 cells were treated for 6 h with Baf or Baf + MRT68921. The ER-phagy receptor, CALCOCO1, was used as a control for basal autophagy in this experiment. Top, representative images for the data quantitated below. Arrowheads mark RTN4 fragments delivered to lysosomes. Bottom, the relative pixel intensity for each condition is the mean intensity of RTN4-GFP in the pixels that overlap with LAMP1-mCherry. The control for each condition was without Baf (DMSO only) and set to 1.0. MRT68921 was used to block autophagosome maturation. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 36 to 66 cells. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test.

Related to Fig. 1 . RTN3L and SEC24C are needed for the delivery of RTN4 fragments to lysosomes during basal autophagy. siCtrl, siRTN3L, siSEC24C, and siCALCOCO1 cells were treated for 6 h with Baf or Baf + MRT68921. The ER-phagy receptor, CALCOCO1, was used as a control for basal autophagy in this experiment. Top, representative images for the data quantitated below. Arrowheads mark RTN4 fragments delivered to lysosomes. Bottom, the relative pixel intensity for each condition is the mean intensity of RTN4-GFP in the pixels that overlap with LAMP1-mCherry. The control for each condition was without Baf (DMSO only) and set to 1.0. MRT68921 was used to block autophagosome maturation. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 36 to 66 cells. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test.

To characterize the RTN3L–SEC24C interaction in more detail, in vitro binding experiments were performed with purified GST proteins and lysates that contained endogenous levels of SEC24C. Although the entire RTN3L cytoplasmic domain fused to GST was unstable, two stable fusion proteins were expressed and purified from bacteria, GST–RTN3L (amino acid [aa] 48–648) and GST-RTN3S (aa 1–47). RTN3S is a short form of RTN3 that does not act in ER-phagy (Grumati et al., 2017). GST–RTN3L (aa 48–648) bound to SEC24C, but not CALCOCO1 (Nthiga et al., 2020), another tubular ER-phagy receptor that was used as a specificity control (Fig. 1 C). SEC24C also specifically bound to GST–RTN3L but not GST-RTN3S (Fig. 1 C).

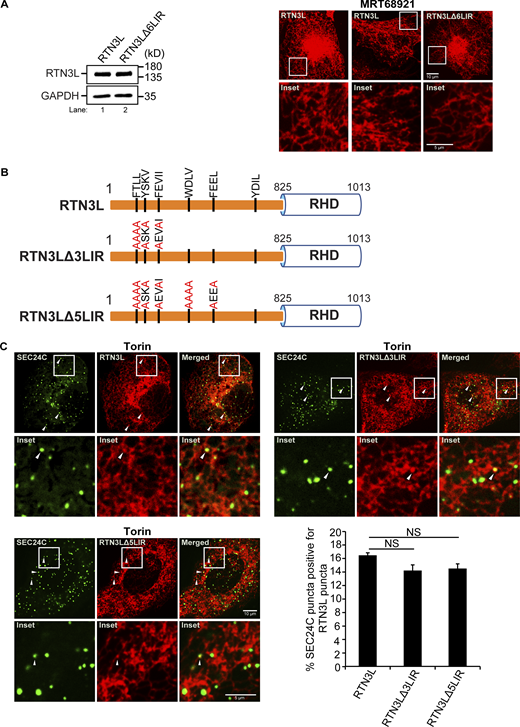

Next, we asked if the LIRs in RTN3L are needed for its interaction with SEC24C. The RTN3L cytoplasmic domain contains six binding sites for LC3 (LIRs) (Grumati et al., 2017). As GST–RTN3L (aa 48–648) lacks the sixth LIR and still binds to SEC24C, this data implies that the sixth LIR is not needed for the RTN3L–SEC24C interaction. Previous studies showed that LC3 binding to RTN3L is blocked when all six LIRs are mutated in the RTN3LΔ6LIR mutant (Grumati et al., 2017). When we treated mCherry–RTN3LΔ6LIR mutant cells with Torin, RTN3L puncta formation was dramatically impaired (Fig. S4 A). This decrease was unlikely to be the consequence of blocking the interaction of RTN3L with lipidated LC3 as no obvious decrease in RTN3L puncta formation was observed when lipidation was blocked in MRT68921-treated cells (Fig. S4 A). As RTN3L puncta formation is a key step in ER-phagy, these observations suggested that the 16-point mutations introduced into RTN3LΔ6LIR may abrogate RTN3L functions that are independent of LC3 binding. Therefore, to address if the remaining five LIRs are needed for the RTN3L–SEC24C interaction, colocalization studies were performed with two LIR mutants (RTN3LΔ3LIR and RTN3LΔ5LIR) that reduce LC3 binding (Grumati et al., 2017), but not RTN3L puncta formation (Fig. S4, B and C). We found that neither mCherry–RTN3LΔ3LIR nor mCherry–RTN3LΔ5LIR significantly affected the colocalization of YFP-SEC24C puncta with mCherry-RTN3L puncta (Fig. S4 C). In total, these studies suggest that the RTN3L LIRs are dispensable for their interaction with SEC24C. These observations are also consistent with the finding that RTN3L co-precipitates with SEC24C when LC3 lipidation is impaired.

Related toFig. 1 . LIRs 1–5 are not needed for the colocalization of SEC24C puncta with RTN3L puncta. (A) Left, a western blot showing that the expression of RTN3L is the same in cells stably expressing mCherry–RTN3L or mCherry–RTN3LΔ6LIR. Right, cells stably expressing mCherry–RTN3L or mCherry–RTN3LΔ6LIR were treated with Torin 2 or MRT68921 for 3.5 h and imaged. (B) Diagram showing the LIR mutations in mCherry-RTN3L. The 6LIRs are shown as black bars and the mutated amino acids are in red. (C) Representative images for the constructs shown in B. The percent SEC24C puncta colocalizing with RTN3L puncta were quantified for the constructs shown in B. Cells were treated for 3.5 h with Torin2. Error bars in C represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 60 to 66 cells. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Related toFig. 1 . LIRs 1–5 are not needed for the colocalization of SEC24C puncta with RTN3L puncta. (A) Left, a western blot showing that the expression of RTN3L is the same in cells stably expressing mCherry–RTN3L or mCherry–RTN3LΔ6LIR. Right, cells stably expressing mCherry–RTN3L or mCherry–RTN3LΔ6LIR were treated with Torin 2 or MRT68921 for 3.5 h and imaged. (B) Diagram showing the LIR mutations in mCherry-RTN3L. The 6LIRs are shown as black bars and the mutated amino acids are in red. (C) Representative images for the constructs shown in B. The percent SEC24C puncta colocalizing with RTN3L puncta were quantified for the constructs shown in B. Cells were treated for 3.5 h with Torin2. Error bars in C represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 60 to 66 cells. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

The RTN3L–SEC24C ER-phagy pathway acts independently of COPII vesicle traffic

As the lysosomal delivery of RTN3L is dependent on SEC24C, and the SEC24C–SEC23 complex also acts in COPII vesicle traffic, we asked if RTN3L–SEC24C-mediated ER-phagy is regulated by the secretory pathway. RTN3L targets a subpopulation of misfolded proinsulin Akita, which forms high molecular weight ERAD-resistant oligomers, for autophagy (Cunningham et al., 2019). Akita oligomers targeted for ER-phagy can be visualized in ER tubules with Akita-sfGFP as small (≤0.12 µm2) highly mobile puncta that behave like liquid condensates (Parashar et al., 2021). These condensates/puncta change size and shape as they move through the network (Parashar et al., 2021). Akita condensates colocalize with LC3, SEC24C, and RTN3L puncta that form on the ER when ER-phagy is induced (Parashar et al., 2021). Furthermore, the colocalization of LC3 with Akita puncta is dependent on RTN3L (Parashar et al., 2021). The RTN3L–SEC24C–LC3B-containing puncta, called ERPHS, appears to be similar in size to ERES (Parashar et al., 2021). However, RTN3L puncta do not colocalize with the COPII subunits SEC24A and SEC13 or SEC16, a marker for ERES (Parashar et al., 2021). When cells are depleted of RTN3L or the autophagy protein Beclin1, Akita forms a massive detergent insoluble complex in the ER, and large puncta (≥0.5 µm2) accumulate in a fraction (˜40%) of the cells (Chen et al., 2020; Cunningham et al., 2019; Parashar et al., 2021). These large puncta also form when cells are depleted of SEC24C (Parashar et al., 2021) but not the other SEC24 isoforms (Parashar et al., 2021). In addition to the formation of large puncta, the mean size of Akita puncta/condensates per cell also increases when ER-phagy is blocked (Fig. 1 D) (Parashar et al., 2021). Together these studies show that ERAD-resistant misfolded Akita condensates traffic from the ER to the lysosome from an ER subdomain that appears to be distinct from the site where COPII vesicles traffic to the Golgi (Cui et al., 2019; Parashar et al., 2021).

Although RTN3L–SEC24C acts at sites that are distinct from the ERES, the RTN3L-ER-phagy pathway could be regulated by COPII vesicle traffic. To directly address this possibility, we blocked secretion with the T39N SAR1 mutant and asked if large Akita puncta accumulates in the ER. SAR1-T39N is a dominant negative mutant that blocks the formation of ERES (Kuge et al., 1994). We found that the depletion of SEC24C, but not the expression of SAR-T39N, increased the percentage of cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2), as well as the mean size of Akita puncta per cell (Fig. 1 D). Consistent with this observation, the delivery of Akita to lysosomes was not disrupted in SAR1 mutant cells (Fig. S1 E). siSEC31A-treated cells also failed to accumulate large Akita puncta (Fig. 1 D and Fig. S1 D, right). In contrast, and consistent with a block in secretion, Proinsulin-sfGFP puncta (≥0.35 µm2) accumulated in the ER (see Materials and methods for quantitation details) of SAR1-T39N transfected cells and cells lacking SEC24C or SEC31A (Fig. S1 F), but not RTN3L (Fig. S1 F). Together, these findings indicate that RTN3L–SEC24C–mediated ER-phagy acts independently of the secretory pathway and COPII vesicle traffic.

FIP200 is needed for the accumulation of misfolded Akita condensates at three-way junctions

RTN3L puncta were frequently seen colocalizing with SEC24C puncta at three-way tubule junctions in Torin-treated cells (Fig. S4 C). This observation prompted us to ask if the RTN3L–SEC24C receptor complex targets misfolded Akita condensates for ER-phagy at junctions. To begin to address this question, we first asked if RTN3L puncta accumulate at junctions. FAM134B was used as a control for these studies as it mediates ER quality control at ERES and not ERPHS (Parashar et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2023). Junctions were marked by LNPK, which forms puncta at three-way tubule junctions (Chen et al., 2012, 2015). We found that LNPK puncta colocalized with RTN3L, but not FAM134B, puncta (Fig. 1 E). The colocalization of LNPK puncta with RTN3L puncta did not decrease in SEC24C-depleted cells (Fig. S5 A), indicating that RTN3L localization at junctions is not dependent on SEC24C. Consistent with these studies, RTN3L and SEC24C, but not FAM134B, were needed for the delivery of LNPK to lysosomes in a rich medium (Fig. 1 F and Fig. S5 B). LC3 lipidation also appeared to be needed for LNPK delivery as it was blocked by MRT68921 (Fig. 1 F). Interestingly, when we examined a second tubular ER-phagy receptor that acts in basal ER-phagy, CALCOCO1 (Nthiga et al., 2020), it was dispensable for the lysosomal delivery of LNPK-marked junctions (Fig. S5 B).

Related toFig. 1,. FAM134B and CALCOCO1 are not required for the delivery of LNPK puncta to lysosomes. (A) Left, control and siSEC24C-treated cells transfected with LNPK-GFP and mCherry-RTN3L. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta. Right, quantitation of percent LNPK puncta colocalizing with RTN3L puncta. (B) Bottom, same as Fig. 1 F, only siFAM134B and siCALCOCO1-treated cells were examined. The control is the same as in Fig. 1 F as the samples were all assayed at the same time. Bottom right, western blot analysis was performed with control and FAM134B-depleted lysates. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Error bars in A and B represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 40 to 50 cells in A, and 63–87 cells in B. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS5.

Related toFig. 1,. FAM134B and CALCOCO1 are not required for the delivery of LNPK puncta to lysosomes. (A) Left, control and siSEC24C-treated cells transfected with LNPK-GFP and mCherry-RTN3L. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta. Right, quantitation of percent LNPK puncta colocalizing with RTN3L puncta. (B) Bottom, same as Fig. 1 F, only siFAM134B and siCALCOCO1-treated cells were examined. The control is the same as in Fig. 1 F as the samples were all assayed at the same time. Bottom right, western blot analysis was performed with control and FAM134B-depleted lysates. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Error bars in A and B represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 40 to 50 cells in A, and 63–87 cells in B. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS5.

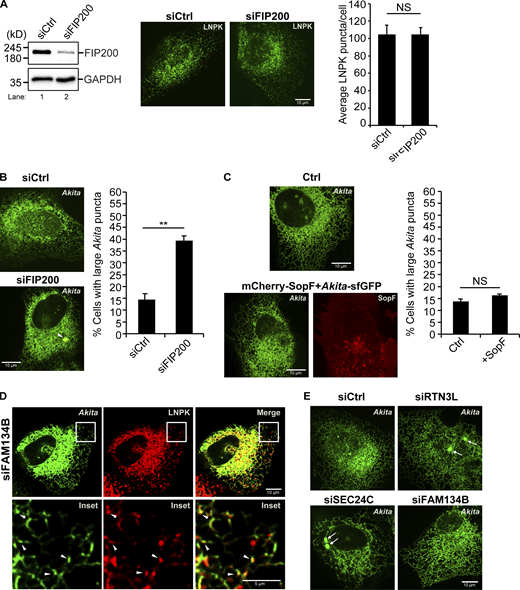

We found that small Akita-sfGFP, but not wild-type Proinsulin-sfGFP, puncta colocalized with LNPK-mCherry puncta at tubule junctions (Fig. 2 A). To ask if Akita condensates accumulate in autophagosomes or preautophagosomal structures at junctions, colocalization studies were performed in FIP200-depleted cells. FIP200 is a component of the autophagy machinery that lipidates LC3 during double-membrane autophagosome biogenesis (Hara et al., 2008). Interestingly, while knocking down FIP200 did not decrease LNPK-marked junctions (Fig. S6 A), the accumulation of Akita-sfGFP puncta at LNPK junctions significantly decreased in the depleted cells (Fig. 2 B). When Akita puncta failed to accumulate at junctions in siFIP200 knock down cells, the condensates enlarged (≥0.5 µm2) and accumulated in the ER (Fig. S6 B), indicating that ER-phagy was blocked. Consistent with the proposal that RTN3L–SEC24C–mediated ER-phagy is autophagosome-mediated, the overexpression of a mCherry-SopF construct that is known to block LC3 lipidation during noncanonical autophagy (Hooper et al., 2022; Lau et al., 2019), did not lead to the accumulation of large Akita puncta/condensates in the ER (Fig. S6 C). SopF is a Salmonella effector that blocks the V-ATPase–ATG16L1–mediated LC3 lipidation of single membrane vesicles (Hooper et al., 2022; Lau et al., 2019).

FIP200 and the RTN3L–SEC24C complex are required for the retention of Akita puncta at three-way junctions. (A) Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta in cells transfected with LNPK-mCherry and Akita-sfGFP or Proinsulin-sfGFP. (B) Same as A, only Akita puncta were examined in siCtrl and siFIP200-treated cells. (C) Cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP and LNPK-mCherry in siCtrl or siRNA-treated cells. Arrowheads mark Akita puncta that colocalize with LNPK puncta. (D) Top, percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2), and mean size of Akita puncta (bottom) for the data in C. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 44 to 59 cells in A, 37–40 cells in B, 38–42 cells in C, and 115–139 cells in D. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), *** (P < 0.001), Student’s unpaired t test.

FIP200 and the RTN3L–SEC24C complex are required for the retention of Akita puncta at three-way junctions. (A) Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta in cells transfected with LNPK-mCherry and Akita-sfGFP or Proinsulin-sfGFP. (B) Same as A, only Akita puncta were examined in siCtrl and siFIP200-treated cells. (C) Cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP and LNPK-mCherry in siCtrl or siRNA-treated cells. Arrowheads mark Akita puncta that colocalize with LNPK puncta. (D) Top, percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2), and mean size of Akita puncta (bottom) for the data in C. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 44 to 59 cells in A, 37–40 cells in B, 38–42 cells in C, and 115–139 cells in D. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), *** (P < 0.001), Student’s unpaired t test.

Related toFig. 2,. SopF does not inhibit RTN3L–SEC24C-mediated ER-phagy. (A) Left, a western blot showing the depletion of FIP200 in siFIP200-treated cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Right, quantitation of LNPK-GFP puncta in siCtrl and siFIP200-treated cells. Representative images are shown on the left. (B) Left, a representative image of a control cell and a siFIP200-treated cell showing the accumulation of a large Akita puncta (see arrowhead). Right, the percent cells with large Akita puncta in control and FIP200-depleted cells. (C) Cells were transfected with Akita-sfGFP or Akita-sfGFP and mCherry-SopF. Representative images are shown on the left and the percent cells with large Akita puncta is graphed on the right. (D) A representative image for the data quantitated in Fig. 2 C. Arrowheads mark Akita-sfGFP puncta that colocalize with LNPK-mCherry puncta. (E) Representative images for the data graphed in Fig. 2 D. Arrows mark large Akita puncta. Error bars in A–C represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 61 to 64 cells in A, 56–104 cells in B, and 92–95 cells in C. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS6.

Related toFig. 2,. SopF does not inhibit RTN3L–SEC24C-mediated ER-phagy. (A) Left, a western blot showing the depletion of FIP200 in siFIP200-treated cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Right, quantitation of LNPK-GFP puncta in siCtrl and siFIP200-treated cells. Representative images are shown on the left. (B) Left, a representative image of a control cell and a siFIP200-treated cell showing the accumulation of a large Akita puncta (see arrowhead). Right, the percent cells with large Akita puncta in control and FIP200-depleted cells. (C) Cells were transfected with Akita-sfGFP or Akita-sfGFP and mCherry-SopF. Representative images are shown on the left and the percent cells with large Akita puncta is graphed on the right. (D) A representative image for the data quantitated in Fig. 2 C. Arrowheads mark Akita-sfGFP puncta that colocalize with LNPK-mCherry puncta. (E) Representative images for the data graphed in Fig. 2 D. Arrows mark large Akita puncta. Error bars in A–C represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 61 to 64 cells in A, 56–104 cells in B, and 92–95 cells in C. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS6.

The retention of misfolded Akita condensates/puncta at three-way junctions also required RTN3L and SEC24C, but not FAM134B (Fig. 2 C and Fig. S6 D), while wild-type proinsulin localization remained unchanged in the absence of each of these three proteins (Fig. S7 A). When misfolded Akita failed to accumulate at junctions, large condensates accumulated in the ER (Fig. 2 D, top and bottom, Fig. S6 E). While SEC24C was not needed for the localization of RTN3L puncta at junctions, it was required for the association of RTN3L with Akita condensates (Fig. S7 B). This observation is consistent with the proposal that RTN3L cannot function in ER-phagy unless it is complexed to SEC24C. When RTN3L failed to associate with misfolded Akita, the condensates enlarged in the ER and accumulated (Fig. S7 C). As previous studies have shown that the association of misfolded Akita with LC3B requires RTN3L (Parashar et al., 2021), these observations imply that FIP200-dependent RTN3L–SEC24C–LC3B-containing ERPHS accumulate at ER junctions.

Related to Fig. 2 . SEC24C is needed for the association of RTN3L puncta with misfolded Akita. (A) Cells were transfected with LNPK-mCherry and Proinsulin-sfGFP and the percent proinsulin puncta that colocalize with LNPK was quantitated, bottom. Top, representative images are shown. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. (B) siCtrl and siSEC24C-treated cells were transfected with Akita-sfGFP and mCherry-RTN3L and imaged. Arrowheads point to the Akita puncta that colocalize with RTN3L puncta. Right, quantification of the % Akita puncta positive for RTN3L puncta. (C) Percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2) for the experiment shown in B. The large Akita puncta are marked with arrows in the images shown. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 48 to 53 cells in A, 49–56 cells in B, and 113–125 cells in C. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test.

Related to Fig. 2 . SEC24C is needed for the association of RTN3L puncta with misfolded Akita. (A) Cells were transfected with LNPK-mCherry and Proinsulin-sfGFP and the percent proinsulin puncta that colocalize with LNPK was quantitated, bottom. Top, representative images are shown. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. (B) siCtrl and siSEC24C-treated cells were transfected with Akita-sfGFP and mCherry-RTN3L and imaged. Arrowheads point to the Akita puncta that colocalize with RTN3L puncta. Right, quantification of the % Akita puncta positive for RTN3L puncta. (C) Percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2) for the experiment shown in B. The large Akita puncta are marked with arrows in the images shown. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 48 to 53 cells in A, 49–56 cells in B, and 113–125 cells in C. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test.

CUL3KLHL12 is needed for the autophagy of tubule components at junctions

We reasoned that the formation of RTN3L–SEC24C containing ERPHS may require other components that are enriched at junctions. The E3 ligase, CUL3KLHL12, is a candidate as it is recruited to membranes at ER junctions (Akopian et al., 2022; Yuniati et al., 2020). Consistent with the proposal that CUL3KLHL12 and its substrate adaptor, KLHL12, are needed for ER-phagy, we found that the lysosomal delivery of RTN3L was significantly impaired in KLHL12- or CUL3-depleted cells (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S8 A). In line with the studies described above, siFIP200-treatment also blocked the delivery of RTN3L to lysosomes (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S8 A).

CUL3KLHL12is needed for ER-phagy and the ubiquitination of RTN3L. (A) YFP-RTN3L in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siRNA-treated cells incubated with Baf (4 h). Representative images are shown on the left and in Fig. S8 A. The control for each condition was set to 1.0. (B) RTN3L coprecipitates with KLHL12, but not CALCOCO1. Immunoprecipitations were performed as in Fig. 1 A only the precipitates were eluted using HA peptide as described in the methods. Left, input is 2% of the lysate. Right, equal KLHL12 inputs were used for the immunoprecipitates. (C) Same as B, except the immunoprecipitates were eluted in sample buffer. 4.8 x more PEF1 was precipitated in the tagged sample compared to the untagged control. Input is 2% of the lysate. Equal amounts of PEF1 and SEC24C were used for the immunoprecipitates (see Fig. S8 B). (D) Left, high (asterisks) and low (brackets) molecular weight forms of ubiquitinated RTN3L were detected with ubiquitin antibody. Right, cells were untreated (DMSO) or treated with Baf or Torin 2 + Baf (4 h). (E) The ubiquitination of RTN3L is dependent on KLHL12 and CUL3. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3–6 independent experiments. The results in A were quantified from 59 to 154 cells. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), *** (P < 0.001), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

CUL3KLHL12is needed for ER-phagy and the ubiquitination of RTN3L. (A) YFP-RTN3L in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siRNA-treated cells incubated with Baf (4 h). Representative images are shown on the left and in Fig. S8 A. The control for each condition was set to 1.0. (B) RTN3L coprecipitates with KLHL12, but not CALCOCO1. Immunoprecipitations were performed as in Fig. 1 A only the precipitates were eluted using HA peptide as described in the methods. Left, input is 2% of the lysate. Right, equal KLHL12 inputs were used for the immunoprecipitates. (C) Same as B, except the immunoprecipitates were eluted in sample buffer. 4.8 x more PEF1 was precipitated in the tagged sample compared to the untagged control. Input is 2% of the lysate. Equal amounts of PEF1 and SEC24C were used for the immunoprecipitates (see Fig. S8 B). (D) Left, high (asterisks) and low (brackets) molecular weight forms of ubiquitinated RTN3L were detected with ubiquitin antibody. Right, cells were untreated (DMSO) or treated with Baf or Torin 2 + Baf (4 h). (E) The ubiquitination of RTN3L is dependent on KLHL12 and CUL3. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3–6 independent experiments. The results in A were quantified from 59 to 154 cells. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), *** (P < 0.001), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

Related toFig. 3,. KLHL12 colocalizes with LNPK at junctions. (A) Representative DMSO control images of YFP-RTN3L puncta with LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl, siFIP200, siCUL3, and siKLHL12-treated cells for the data shown in Fig. 3 A. (B) Inputs for PEF1 and SEC24C for the precipitates that are shown in Fig. 3 C. (C) The in vitro binding experiment was done as in Fig. 1 C only the samples were blotted for the presence of KLHL12. The asterisk marks a breakdown fragment of KLHL12. (D) An image of U2OS cells that were transfected with pHAGE2-LNPK-mCherry and GFP-KLHL12 is shown. Arrowheads mark KLHL12 puncta that colocalize with LNPK puncta. (E) Same as Fig. 3 B, only blotted for the presence of LNPK. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS8.

Related toFig. 3,. KLHL12 colocalizes with LNPK at junctions. (A) Representative DMSO control images of YFP-RTN3L puncta with LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl, siFIP200, siCUL3, and siKLHL12-treated cells for the data shown in Fig. 3 A. (B) Inputs for PEF1 and SEC24C for the precipitates that are shown in Fig. 3 C. (C) The in vitro binding experiment was done as in Fig. 1 C only the samples were blotted for the presence of KLHL12. The asterisk marks a breakdown fragment of KLHL12. (D) An image of U2OS cells that were transfected with pHAGE2-LNPK-mCherry and GFP-KLHL12 is shown. Arrowheads mark KLHL12 puncta that colocalize with LNPK puncta. (E) Same as Fig. 3 B, only blotted for the presence of LNPK. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS8.

Interestingly, mass spectrometry studies identified KLHL12 as an RTN3L interactor and nine ubiquitination sites were identified in RTN3L (Grumati et al., 2017; Pedersen et al., 2021; Sarraf et al., 2013; Stes et al., 2014; Stukalov et al., 2021). Corroborating these findings, the endogenous copy of KLHL12, but not CALCOCO1, was found to coprecipitate with FLAG-HA-RTN3L (Fig. 3 B). The CUL3KLHL12 co-adaptor, PEF1, was also present in the precipitate, as was SEC24C (Fig. 3 C and Fig. S8 B). Since SEC24C does not appear to be a KLHL12 binding partner (McGourty et al., 2016), the SEC24C present in the precipitate is likely bound to RTN3L. In addition, in vitro–binding studies confirmed that the endogenous copy of KLHL12 bound to GST–RTN3L (aa 48–648), but not RTN3S (Fig. S8 C). While we could confirm that KLHL12 puncta extensively colocalize with LNPK-marked junctions (Fig. S8 D), RTN3L did not coprecipitate with LNPK (Fig. S8 E), a known binding partner for KLHL12 at junctions (Akopian et al., 2022; Yuniati et al., 2020). These findings imply that RTN3L binds directly to CUL3KLHL12.

Consistent with mass spectrometry studies, ubiquitinated RTN3L was detected in FLAG-HA-RTN3L, but not untagged, precipitates (Fig. 3 D, left). Strikingly, RTN3L ubiquitination was only observed in the presence of Baf or Baf + Torin 2 (Fig. 3 D, right), implying that the ubiquitinated form of the receptor is preferentially degraded in lysosomes. RTN3L ubiquitination was dependent on CUL3KLHL12, as it decreased in KLHL12 and CUL3-depleted cells (Fig. 3 E). Two forms of ubiquitinated RTN3L were observed, one form that migrates between the 135 and 180 kD markers (Fig. 3, D and E), and a high molecular weight species that migrates near the 245 kD marker (Fig. 3, D and E). The ubiquitination of both forms partially decreased in CUL3 KLHL12-depleted cells (Fig. 3 E). The ubiquitinated RTN3L high molecular weight species is similar in size to an SDS-resistant oligomer described below (Fig. S9 D). MLN4924, which blocks CUL3 ligase activity and CUL3 neddylation (Fig. S9 A) (Soucy et al., 2009), also partially decreased the ubiquitination of RTN3L (Fig. S9 A), while the potent ubiquitination inhibitor, TAK243, completely blocked ubiquitination (Fig. S9 B). These observations suggest that RTN3L may be ubiquitinated by additional E3 ligases. RTN3L ubiquitination did not lead to proteasomal degradation, as no significant increase in RTN3L was seen in U2OS cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132 (Fig. S9 C).

Related to Fig. 3,. The ubiquitination of RTN3L increases in the presence of Baf. (A) Left, CUL3 blot showing that the neddylation of CUL3 is blocked 4 h after treatment with 1 µM MLN4924. Right, same as Fig. 3 E only the sample in lane 4 was treated for 4 h with Baf with 1 µM MLN4924. (B) Same as Fig. 3 D only the sample was treated with 10 µM TAK243 for 4 h. (C) U2OS cells were treated for 4 h with 10 μM MG132 before lysates were prepared for western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D) Membranes were prepared from control, siCUL3 and siSEC24C-treated cells and crosslinked with the indicated concentration of EGS as described in the methods. (E) Top, the position of the known RTN3L ubiquitination sites are shown. Five of the nine sites are in the C-terminus of the RHD. Bottom, the five sites shown are predicted to be at the end of the second hairpin in the RHD. Right, images of mCherry-RTN3L and mCherry-RTN3L-5KR. The mCherry-RTN3L-5KR mutant contains five mutations (K977R, K979R, K995R, K999R and K1003R) that were found to disrupt the tubular ER network. (F) Representative control images of LNPK-GFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCUL3 and siKLHL12-treated cells for the data shown in Fig. 4 A. (G) Representative control images of Akita-sfGFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siRNA-treated cells for the data shown in Fig. 4 B. The siCtrl was also treated with Baf + MRT68921 for 3.5 h to block autophagosome maturation.

Related to Fig. 3,. The ubiquitination of RTN3L increases in the presence of Baf. (A) Left, CUL3 blot showing that the neddylation of CUL3 is blocked 4 h after treatment with 1 µM MLN4924. Right, same as Fig. 3 E only the sample in lane 4 was treated for 4 h with Baf with 1 µM MLN4924. (B) Same as Fig. 3 D only the sample was treated with 10 µM TAK243 for 4 h. (C) U2OS cells were treated for 4 h with 10 μM MG132 before lysates were prepared for western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D) Membranes were prepared from control, siCUL3 and siSEC24C-treated cells and crosslinked with the indicated concentration of EGS as described in the methods. (E) Top, the position of the known RTN3L ubiquitination sites are shown. Five of the nine sites are in the C-terminus of the RHD. Bottom, the five sites shown are predicted to be at the end of the second hairpin in the RHD. Right, images of mCherry-RTN3L and mCherry-RTN3L-5KR. The mCherry-RTN3L-5KR mutant contains five mutations (K977R, K979R, K995R, K999R and K1003R) that were found to disrupt the tubular ER network. (F) Representative control images of LNPK-GFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCUL3 and siKLHL12-treated cells for the data shown in Fig. 4 A. (G) Representative control images of Akita-sfGFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siRNA-treated cells for the data shown in Fig. 4 B. The siCtrl was also treated with Baf + MRT68921 for 3.5 h to block autophagosome maturation.

As recent studies suggested that the ubiquitination of the RHD in FAM134B increases its oligomerization and enhances ER-phagy (González et al., 2023), we asked if CUL3 KLHL12 enhances the oligomerization of RTN3L. RTN3L oligomers can be visualized by irreversibly crosslinking intact membranes with the crosslinker EGS (Shibata et al., 2008). When control membranes were crosslinked, two high-molecular weight RTN3L species were observed (Fig. S9 D). Both species formed as efficiently in CUL3 or SEC24C-depleted cells as in control cells (Fig. S9 D), indicating that CUL3KLHL12 does not facilitate RTN3L oligomerization and may have other roles in ER-phagy (see Discussion). To ask if ubiquitination of the RHD plays a role in RTN3L function, we mutated the five known ubiquitin sites (amino acids K977, K979, K995, K999 and K1003, RTN3L-5KR) that are clustered in the second hairpin of the RHD (Fig. S9 E, top and bottom) (Jumper et al., 2021; Varadi et al., 2022) by substituting lysine for arginine. However, the combination of these five mutations severely disrupted the tubular ER network and decreased cell viability (Fig. S9 E, right). This observation suggested that the RTN3L-5 KR mutations may be impairing RHD functions that are independent of ubiquitination, and for this reason, we decided not to characterize these mutations any further.

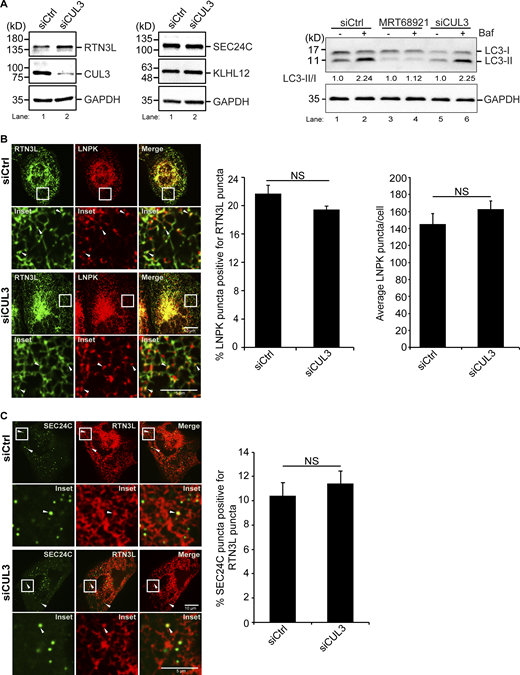

As the CUL3KLHL12 substrate, RTN3L, is needed for the FIP200-dependent accumulation of Akita at junctions, we asked if CUL3KLHL12 targets tubule components for ER-phagy at junctions. When we knocked down KLHL12 or CUL3, LNPK was no longer delivered to lysosomes (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S9 F), indicating that CUL3KLHL12 is needed for the delivery of junction components to lysosomes. Additionally, misfolded Akita failed to be delivered to lysosomes in CUL3KLHL12 -depleted cells (Fig. 4 B and Fig. S9 G) and as a consequence, large Akita puncta accumulated in the ER (Fig. 4 C). Interestingly, Akita-sfGFP also failed to colocalize with LNPK-mCherry in ligase-deficient cells (Fig. 4 D). Therefore, like RTN3L, CUL3KLHL12 is needed to retain Akita condensates/puncta at junctions. The failure of Akita to localize to junctions in the depleted cells was not the consequence of decreased levels of RTN3L, SEC24C (Fig. S10 A, left and middle) or impaired autophagosome formation, as lipidated LC3 levels were unaltered (Fig. S10 A, right). Instead, and consistent with a defect in lysosomal delivery, RTN3L levels were reproducibly higher in siCUL3 cells (Fig. S10 A, left). SEC24C levels did not increase, likely because only a small fraction of the total SEC24C is devoted to ER-phagy. While the loss of CUL3KLHL12 blocked the delivery of junction components to lysosomes, the colocalization of RTN3L puncta with LNPK puncta (Fig. S10 B, left) and SEC24C puncta (Fig. S10 C) were unaltered in the absence of ligase. LNPK still appeared to localize to junctions in CUL3-depleted cells, as the number of LNPK puncta was the same as the control (Fig. S10 B, right). This finding is consistent with the observation that ER structure is not disrupted in CUL3-depleted cells (Yuniati et al., 2020).

CUL3 KLHL12 is needed for the accumulation of Akita condensates at junctions. (A) Quantitation of LNPK-GFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siRNA-treated cells incubated with Baf (6 h). Representative images on the left and in Fig. S9 F. The control for each condition was set to 1.0. (B) Quantitation of Akita-sfGFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siRNA-treated cells with Baf (3.5 h). Representative images on the left and in Fig. S9 G(C) Images and the percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2) (left), and the mean size of Akita puncta (right) in Ctrl and siRNAi-treated cells. Arrows mark large Akita puncta. (D) Left, images of cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP and LNPK-mCherry in siCtrl or siCUL3-treated cells. Arrowheads mark Akita puncta that colocalize with LNPK puncta. Quantitation is on the right. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 62 to 78 cells in A, 59–77 cells in B, 112–154 cells in C, and 39–44 cells in D. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test.

CUL3 KLHL12 is needed for the accumulation of Akita condensates at junctions. (A) Quantitation of LNPK-GFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siRNA-treated cells incubated with Baf (6 h). Representative images on the left and in Fig. S9 F. The control for each condition was set to 1.0. (B) Quantitation of Akita-sfGFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siRNA-treated cells with Baf (3.5 h). Representative images on the left and in Fig. S9 G(C) Images and the percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2) (left), and the mean size of Akita puncta (right) in Ctrl and siRNAi-treated cells. Arrows mark large Akita puncta. (D) Left, images of cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP and LNPK-mCherry in siCtrl or siCUL3-treated cells. Arrowheads mark Akita puncta that colocalize with LNPK puncta. Quantitation is on the right. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 62 to 78 cells in A, 59–77 cells in B, 112–154 cells in C, and 39–44 cells in D. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test.

Related toFig. 4 . The localization of RTN3L puncta to three-way junctions is not dependent on CUL3KLHL12. (A) Left, the level of RTN3L, but not SEC24C or KLHL12, increases in CUL3-depleted U2OS cells. Western blot analysis was performed with lysates from Ctrl and CUL3-depleted cells. Quantitation of the blot revealed there was approximately a 1.5 times increase of RTN3L in siCUL3-treated cells compared with siCtrl cells, when the RTN3L levels were normalized to GAPDH. Right, western blot analysis was performed with lysates prepared from cells that were treated with DMSO or Baf for 3.5 h. The LC3-II/I ratio is reported in the figure. The data was normalized to GAPDH. (B) Left, cells were transfected with LNPK-GFP and mCherry-RTN3L. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta. Middle, quantification of percent LNPK puncta colocalizing with RTN3L puncta, and average LNPK puncta/cell (right) in siCtrl and siCUL3-treated cells. (C) Representative images of the colocalization of mCherry-RTN3L puncta with YFP-SEC24C puncta in Ctrl and CUL3-depleted cells that were treated with Torin 2 for 3.5 h. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta. Error bars in B and C represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 42 to 43 cells in B, and 38–41 cells in C. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS10.

Related toFig. 4 . The localization of RTN3L puncta to three-way junctions is not dependent on CUL3KLHL12. (A) Left, the level of RTN3L, but not SEC24C or KLHL12, increases in CUL3-depleted U2OS cells. Western blot analysis was performed with lysates from Ctrl and CUL3-depleted cells. Quantitation of the blot revealed there was approximately a 1.5 times increase of RTN3L in siCUL3-treated cells compared with siCtrl cells, when the RTN3L levels were normalized to GAPDH. Right, western blot analysis was performed with lysates prepared from cells that were treated with DMSO or Baf for 3.5 h. The LC3-II/I ratio is reported in the figure. The data was normalized to GAPDH. (B) Left, cells were transfected with LNPK-GFP and mCherry-RTN3L. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta. Middle, quantification of percent LNPK puncta colocalizing with RTN3L puncta, and average LNPK puncta/cell (right) in siCtrl and siCUL3-treated cells. (C) Representative images of the colocalization of mCherry-RTN3L puncta with YFP-SEC24C puncta in Ctrl and CUL3-depleted cells that were treated with Torin 2 for 3.5 h. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta. Error bars in B and C represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 42 to 43 cells in B, and 38–41 cells in C. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS10.

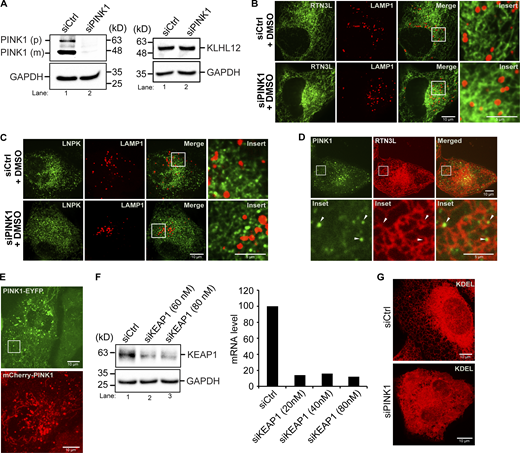

The loss of PINK1 decreases peripheral ER junctions and blocks ER-phagy

The PINK1 kinase was recently shown to be required for ER-phagy during drosophila intestinal development (Wang et al., 2023). PINK1 is a mitochondrial kinase that regulates mitochondrial morphology and stimulates mitophagy by phosphorylating Parkin and ubiquitin (Pickrell and Youle, 2015). It was proposed that PINK1 determines whether ER or mitochondria are degraded by balancing two E3 ligases that associate with mitochondria, KEAP1 and Parkin (Wang et al., 2023). KEAP1 promotes ER-phagy (Wang et al., 2023), while Parkin regulates mitophagy and directs PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of ubiquitin to influence which organelle is degraded (Wang et al., 2023). To begin to address if mammalian PINK1 is needed for RTN3L–SEC24C-mediated ER-phagy, we examined the delivery of ER to lysosomes during basal autophagy and found a block in the lysosomal delivery of RTN3L and LNPK in siPINK1-treated cells (Fig. 5, A and B; and Fig. S11, A–C). Supporting these experiments, we found that the constitutively expressed ER-phagy reporter, ssRFP-GFP-KDEL, accumulated fewer red dots in siPINK1-depleted cells (Fig. 5 C). GFP is quenched in the lysosome, and as a consequence, ssRFP-GFP-KDEL only forms red dots in this compartment (Chino et al., 2019). Consistent with these findings, we observed PINK1-containing puncta in close proximity to ER junctions (Fig. S11 D). Additionally, some PINK1 puncta were associated with ER tubules as they could be seen moving with the ER network (see Fig. 5 D; Fig. S11 E; and Video 1). We also found that PINK1 is needed for ER proteostasis as large Akita puncta/condensates accumulated in the ER of PINK1-depleted cells (Fig. 5 E). The accumulation of Akita condensates was rescued with RNAi-resistant mCherry-PINK1, but not RNAi-resistant kinase dead PINK1 (Fig. 5 F and Fig. S11 E), indicating that the kinase activity of PINK1 was needed for rescue. When large Akita puncta accumulated in PINK1-deficient cells, Akita failed to be delivered to lysosomes (see below, Fig. 7 B). The block in ER-phagy in PINK1-deficient cells was not mediated by Parkin or KEAP1, as Akita condensates did not accumulate in the ER when cells were depleted of either ligase (Fig. 5, E and G; and Fig. S11 F).

PINK1 is needed to target tubule components for ER-phagy at three-way junctions. (A and B) YFP-RTN3L (A) and LNPK-GFP (B) were quantitated in LAMP1-mCherry marked structures. YFP-RTN3L samples were treated with Baf for 4 h, while LNPK-GFP samples were treated for 6 h. (C) PINK1 and FIP200 are needed for the lysosomal delivery of the ER-phagy reporter ssRFP-GFP-KDEL. The number of red dots per cell are reported for the indicated samples. (D) Stills (3.6, 8.1 and 9.6 s) from Video 1 of cells transfected with mCherry-KDEL and YFP-PINK1. (E–G) Quantitation and representative images used to calculate the percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2) in Ctrl and siRNA-treated cells. In E, the siPINK1-treated cells were transfected with mCherry-RNAi-resistant PINK1 or mCherry-RNAi-resistant PINK1 kinase dead (KD). Arrows mark large Akita puncta. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 58 to 69 cells in A, 47–59 cells in B, 69–85 cells in C, 99–111 cells in E, 79–105 cells in F, and 79–101 cells in G. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), *** (P < 0.001), Student’s unpaired t test.

PINK1 is needed to target tubule components for ER-phagy at three-way junctions. (A and B) YFP-RTN3L (A) and LNPK-GFP (B) were quantitated in LAMP1-mCherry marked structures. YFP-RTN3L samples were treated with Baf for 4 h, while LNPK-GFP samples were treated for 6 h. (C) PINK1 and FIP200 are needed for the lysosomal delivery of the ER-phagy reporter ssRFP-GFP-KDEL. The number of red dots per cell are reported for the indicated samples. (D) Stills (3.6, 8.1 and 9.6 s) from Video 1 of cells transfected with mCherry-KDEL and YFP-PINK1. (E–G) Quantitation and representative images used to calculate the percent cells with large Akita puncta (≥0.5 µm2) in Ctrl and siRNA-treated cells. In E, the siPINK1-treated cells were transfected with mCherry-RNAi-resistant PINK1 or mCherry-RNAi-resistant PINK1 kinase dead (KD). Arrows mark large Akita puncta. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 58 to 69 cells in A, 47–59 cells in B, 69–85 cells in C, 99–111 cells in E, 79–105 cells in F, and 79–101 cells in G. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), *** (P < 0.001), Student’s unpaired t test.

Related toFigs. 5 and 6,. PINK1-containing puncta are in close proximity to ER junctions. (A) Left, western blot analysis was performed using lysates from control and PINK1-depleted cells. The precursor (p) and mature (m) forms of PINK1 are marked in siCtrl samples. Right, KLHL12 was blotted in Ctrl and siPINK1-treated cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Representative control images of YFP-RTN3L puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells for the graph shown in Fig. 5 A. (C) Representative control images of LNPK-GFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siPINK1-treated cells for the graph shown in Fig. 5 B. (D) A representative image of a cell transfected with PINK1-YFP and mCherry-RTN3L. Arrowheads mark PINK1-YFP puncta near junctions. (E) Representative PINK1-YFP (used in Fig. 5 D) and mCherry-PINK1 (used in Fig. 5 F) images. The inset in the PINK1-YFP image was used to make Video 1 and the stills in Fig. 5 D. This area was chosen as it is largely devoid of mitochondria. (F) Left, western blot showing KEAP1 levels in control and siRNA-treated cells. Right, qPCR was performed with cells treated with siKEAP1. (G) Compressed Z stacks of Ctrl and siPINK1-treated cells that were transfected with mCherry-KDEL. A total of 14 slices were compressed for Ctrl cells, and 22 slices for siPINK1-treated cells. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS11.

Related toFigs. 5 and 6,. PINK1-containing puncta are in close proximity to ER junctions. (A) Left, western blot analysis was performed using lysates from control and PINK1-depleted cells. The precursor (p) and mature (m) forms of PINK1 are marked in siCtrl samples. Right, KLHL12 was blotted in Ctrl and siPINK1-treated cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Representative control images of YFP-RTN3L puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells for the graph shown in Fig. 5 A. (C) Representative control images of LNPK-GFP puncta in LAMP1-mCherry structures in siPINK1-treated cells for the graph shown in Fig. 5 B. (D) A representative image of a cell transfected with PINK1-YFP and mCherry-RTN3L. Arrowheads mark PINK1-YFP puncta near junctions. (E) Representative PINK1-YFP (used in Fig. 5 D) and mCherry-PINK1 (used in Fig. 5 F) images. The inset in the PINK1-YFP image was used to make Video 1 and the stills in Fig. 5 D. This area was chosen as it is largely devoid of mitochondria. (F) Left, western blot showing KEAP1 levels in control and siRNA-treated cells. Right, qPCR was performed with cells treated with siKEAP1. (G) Compressed Z stacks of Ctrl and siPINK1-treated cells that were transfected with mCherry-KDEL. A total of 14 slices were compressed for Ctrl cells, and 22 slices for siPINK1-treated cells. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS11.

Related toFig. 5 . PINK1 associates with ER tubules. U2OS cells were transfected with PINK1-YFP and mCherry-KDEL. Puncta containing PINK1-YFP can be seen associating with ER tubules marked with mCherry-KDEL. The time period of recording was 31.5 s. Images were analyzed using Nikon Elements software. Playback speed is 30 frames per second.

Related toFig. 5 . PINK1 associates with ER tubules. U2OS cells were transfected with PINK1-YFP and mCherry-KDEL. Puncta containing PINK1-YFP can be seen associating with ER tubules marked with mCherry-KDEL. The time period of recording was 31.5 s. Images were analyzed using Nikon Elements software. Playback speed is 30 frames per second.

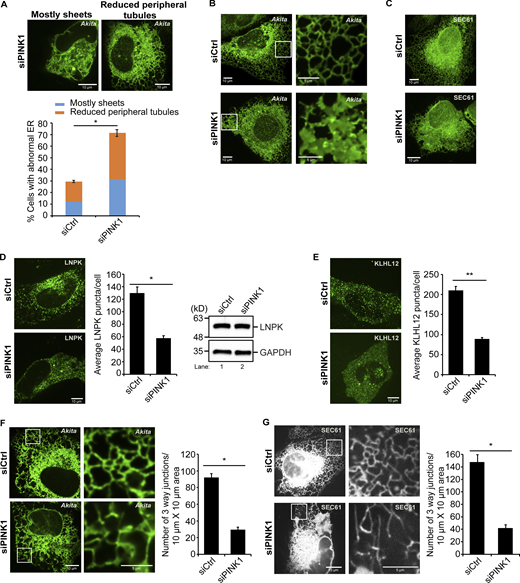

Unexpectedly, we found that the loss of PINK1 altered ER shape. Approximately, 72% of the PINK1-deficient cells had abnormal ER: ∼32% of the cells mostly contained expanded ER sheets, while 40% of the cells appeared to have fewer tubules and junctions at the cell periphery (Fig. 6 A). A 3D reconstruction of the ER network in siPINK1-treated cells illustrates this network defect (see Fig. 6 B; and Videos 2 and 3). The ER morphology defect in PINK1-depleted cells was also confirmed with two ER markers that were commonly used to analyze ER structure, GFP-SEC61 (Fig. 6 C) and mCherry-KDEL (Fig. S11 G). Although the morphology of mitochondria was impaired in siParkin-treated cells (Fig. S12 A), ER organization was similar to control cells (Fig. 5 E), indicating that PINK1 does not indirectly affect ER structure via Parkin. The observation that PINK1-containing puncta associate with the ER, in combination with the structural defects found in PINK1-deficient cells, suggests that mammalian PINK1 directly regulates ER-phagy from the ER and not the mitochondria via Parkin and KEAP1.

Fewer ER junctions are present at the cell periphery in PINK1-depleted cells. (A) siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP were quantitated as described in the methods. (B) Frames from representative 3D reconstructions of Z stacks of siCtrl (22 s in Video 2) and siPINK1-treated (23 s in Video 3) cells. (C) Compressed Z stacks of siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells transfected with GFP-SEC61. A total of 27 slices were compressed for the siCtrl, and 19 slices for siPINK1-treated cells. (D) Left, representative images of LNPK-GFP in siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells. Middle, the average number of LNPK puncta/cell. The data was normalized as described in the methods. Right, blots showing LNPK levels. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (E) Left, representative images used in the quantitation shown on the right. (F) Left, representative images of cells containing Akita-sfGFP with insets used in the quantitation (right) of junctions. (G) Same as E only, cells were transfected with mCherry-Sec61. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 93 to 116 cells in A, 78–82 cells in D, 84–85 cells in E, 27–32 cells in F, and 51–59 cells in G. * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Fewer ER junctions are present at the cell periphery in PINK1-depleted cells. (A) siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP were quantitated as described in the methods. (B) Frames from representative 3D reconstructions of Z stacks of siCtrl (22 s in Video 2) and siPINK1-treated (23 s in Video 3) cells. (C) Compressed Z stacks of siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells transfected with GFP-SEC61. A total of 27 slices were compressed for the siCtrl, and 19 slices for siPINK1-treated cells. (D) Left, representative images of LNPK-GFP in siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells. Middle, the average number of LNPK puncta/cell. The data was normalized as described in the methods. Right, blots showing LNPK levels. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (E) Left, representative images used in the quantitation shown on the right. (F) Left, representative images of cells containing Akita-sfGFP with insets used in the quantitation (right) of junctions. (G) Same as E only, cells were transfected with mCherry-Sec61. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 93 to 116 cells in A, 78–82 cells in D, 84–85 cells in E, 27–32 cells in F, and 51–59 cells in G. * (P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Related toFig. 6 . The tubular ER in control cells. A 3D reconstruction of the ER in control U2OS cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP. The reconstruction contains 28 slices taken with 0.20 µm steps. The image was prepared using Richardson-Lucy algorithm with automatic parameter setting in NIS Elements. Playback speed is 30 frames per second.

Related toFig. 6 . The tubular ER in control cells. A 3D reconstruction of the ER in control U2OS cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP. The reconstruction contains 28 slices taken with 0.20 µm steps. The image was prepared using Richardson-Lucy algorithm with automatic parameter setting in NIS Elements. Playback speed is 30 frames per second.

Related toFig. 6 . ER sheets proliferate at the cell periphery in siPINK1-treated cells. A 3D reconstruction of the ER in siPINK1-treated U2OS cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP. The reconstruction contains 32 slices taken with 0.20 µm steps. ER sheet expansion is visible at the cell periphery. The image was prepared using Richardson-Lucy algorithm with automatic parameter setting in NIS Elements. Playback speed is 30 frames per second.

Related toFig. 6 . ER sheets proliferate at the cell periphery in siPINK1-treated cells. A 3D reconstruction of the ER in siPINK1-treated U2OS cells transfected with Akita-sfGFP. The reconstruction contains 32 slices taken with 0.20 µm steps. ER sheet expansion is visible at the cell periphery. The image was prepared using Richardson-Lucy algorithm with automatic parameter setting in NIS Elements. Playback speed is 30 frames per second.

Related toFigs. 5, 6, and 7,. mCherry-DRP1 suppresses the ER morphology defect in siPINK1-treated cells. (A) Left, western blot analysis was performed using cell lysates depleted of Parkin. Samples were blotted for Parkin and GAPDH. Right, representative images of GFP-Mito7 in Ctrl and siParkin-treated cells. (B) Same as Fig. 6 D middle, only the data was not normalized. (C) siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells containing Akita-sfGFP were transfected with mCherry-Mff, or LNPK-mCherry. Left, representative images for the data graphed on the right. The remaining images are shown in Fig. 7 A. (D) Left, siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells were transfected with mCherry-DRP1 (lane 3) and mCherry-Mff (lane 4) and blotted for the expression of the mCherry fusion proteins. Lane 2 does not contain plasmid. Right, Cells were transfected with mTurquoise2-DRP1 and mCherry-Mff. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta on mitochondrial membranes. (E) The percentage of cells with abnormal ER was quantitated as described in the methods. Error bars in B, C, and E represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 78 to 82 cells in B, 100–195 cells in C, top, 33–38 cells in C, bottom, and 78–154 cells in E. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), *** (P < 0.001), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS12.

Related toFigs. 5, 6, and 7,. mCherry-DRP1 suppresses the ER morphology defect in siPINK1-treated cells. (A) Left, western blot analysis was performed using cell lysates depleted of Parkin. Samples were blotted for Parkin and GAPDH. Right, representative images of GFP-Mito7 in Ctrl and siParkin-treated cells. (B) Same as Fig. 6 D middle, only the data was not normalized. (C) siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells containing Akita-sfGFP were transfected with mCherry-Mff, or LNPK-mCherry. Left, representative images for the data graphed on the right. The remaining images are shown in Fig. 7 A. (D) Left, siCtrl and siPINK1-treated cells were transfected with mCherry-DRP1 (lane 3) and mCherry-Mff (lane 4) and blotted for the expression of the mCherry fusion proteins. Lane 2 does not contain plasmid. Right, Cells were transfected with mTurquoise2-DRP1 and mCherry-Mff. Arrowheads mark colocalizing puncta on mitochondrial membranes. (E) The percentage of cells with abnormal ER was quantitated as described in the methods. Error bars in B, C, and E represent SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. The results were quantified from 78 to 82 cells in B, 100–195 cells in C, top, 33–38 cells in C, bottom, and 78–154 cells in E. NS: not significant (P ≥ 0.05), * (P < 0.05), *** (P < 0.001), Student’s unpaired t test. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS12.

A role for PINK1 in regulating ER structure has not been previously reported. To begin to assess how PINK1 shapes the ER, we analyzed LNPK-marked ER junctions. LNPK marks most but not all ER junctions (Chen et al., 2015). When junctions are diminished, fewer LNPK puncta are present throughout the ER network. As junctions decrease, the tubular network is reduced and ER sheets are expanded (Chen et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). To ask if the loss of PINK1 leads to a decrease in LNPK-marked junctions, control and siPINK1-treated cells were transfected with LNPK-GFP and puncta numbers were quantified (Fig. 6 D). Interestingly, a significant decrease in LNPK puncta was observed in the absence of PINK1 (Fig. 6 D). Similar results were obtained whether or not the data was normalized to account for differences in transfection efficiency (see Materials and methods and compare Fig. 6 D, middle to Fig. S12 B), indicating that transfection was comparable in both samples. The decrease in puncta was not due to a reduction in the level of LNPK as the endogenous expression of LNPK was unchanged in the depleted cells (Fig. 6 D, right). As LNPK sequesters KLHL12 at junctions (Akopian et al., 2022; Yuniati et al., 2020), we also analyzed GFP-KLHL12 puncta in siPINK1-treated cells. GFP-KLHL12 puncta significantly decreased in PINK1-depleted cells, while the cytosolic pool appeared to increase, and the endogenous KLHL12 level remained unchanged (Fig. 6 E and Fig. S11 A). Together these findings imply that fewer LNPK-marked junctions are present in the ER network of PINK1-depleted cells.

As the reduction in ER tubules and junctions in siPINK1-treated cells was most obvious at the cell periphery, we quantitatively assessed ER junctions by scoring the number of three-way junctions in a 10 × 10 µm boxed area at the cell periphery (see Materials and methods for details). First, we measured the number of junctions in PINK1-depleted cells expressing Akita-sfGFP and compared the data with control cells. Consistent with the observed defect in peripheral ER tubules, we found a dramatic decrease in peripheral ER junctions in the absence of PINK1 (Fig. 6 F). Similar results were obtained when junctions were measured in control and depleted cells that were transfected with mCherry-SEC61 (Fig. 6 G). These findings suggest that the defect in RTN3L–SEC24C–mediated ER-phagy in PINK1-depleted cells is due to a dramatic loss of peripheral tubular ER junctions.

DRP1 induces ER tubulation in PINK1-deficient cells and suppresses the ER-phagy defect

If the defect in ER-phagy in PINK1-deficient cells is the consequence of disrupting peripheral ER junctions, ER-phagy should be restored as junctions are replenished. The PINK1 kinase substrate, DRP1, is a dynamin-related GTPase that is recruited from the cytosol to the ER where it promotes peripheral ER tubulation to facilitate ER–mitochondria interactions and mitochondrial fission (Adachi et al., 2020). Interestingly, the tubulating activity of DRP1 is independent of GTP hydrolysis and is contained within an 18-amino acid peptide (called D-octadecapeptide) (Adachi et al., 2020). As the overexpression of DRP1 has been shown to suppress the mitochondrial morphology defect in PINK1 mutant cells (Poole et al., 2008), we asked if DRP1 overexpression suppresses the ER structural defect in PINK1 knockdown cells. Membrane-bound DRP1 forms two distinct pools of puncta on the ER (Adachi et al., 2020). One pool associates with Mff to mediate DRP1-dependent mitochondrial fission, while the second pool acts independently of Mff to promote ER tubulation (Adachi et al., 2020; Ji et al., 2017). In addition, DRP1 associates with Mff on mitochondria (Ji et al., 2017). Previous studies have shown that the role of DRP1 in ER tubulation is independent of its role in mitochondrial fission (Adachi et al., 2020).