Constitutive integrin endocytosis and recycling control cell movement and morphology. In contrast, the role of newly synthesized integrins delivered via the biosynthetic pathway has been largely overlooked. We used the retention using selective hooks system to monitor the localization of new integrins exiting the endoplasmic reticulum in space and time. We discovered that new integrin delivery to the plasma membrane is polarized and enhances cell protrusion and focal adhesion growth in an extracellular matrix-ligand–dependent manner. Motor-clutch modeling explained the increased adhesion as higher integrin availability driving recruitment of additional receptors. Unexpectedly, live-cell imaging revealed a small subset of fast-emerging integrin vesicles rapidly transported to the cell surface to facilitate localized spreading. This unconventional secretion depended on cell adhesion and correlated with increased surface levels of immature, high-mannose glycosylated integrin, indicating bypass of the canonical Golgi-dependent secretory pathway. Thus, spatial plasma membrane-targeting of new integrins rapidly alters adhesion receptor availability, providing cells with added plasticity to respond to their environment.

Introduction

Cells sense and respond to the extracellular matrix (ECM) through integrins and integrin localization at the plasma membrane is essential for focal adhesion (FA) formation. Numerous studies have addressed the dynamics of FA assembly as a function of integrin diffusion along the plasma membrane, and integrin activation and tethering to the cytoskeleton through components of the integrin adhesion complexes, such as talin and vinculin (Paszek et al., 2014; Saltel et al., 2009; Humphries et al., 2007). On the other hand, FA disassembly has been investigated from the point of view of proteolytic cleavage of adhesion components, microtubule-dependent adhesion turnover and integrin endocytosis from the plasma membrane (Yue et al., 2014; Ezratty et al., 2009; Chan et al., 2010). In addition, the recycling of plasma membrane endocytosed integrin back to the cell surface has been extensively studied and implicated in the generation of local cell protrusions, co-trafficking with growth-factor receptors, cell invasion and system-level metastasis (Astro et al., 2016; Caswell et al., 2008; Alanko et al., 2015). These studies, however, have focused on endo/exocytic traffic of mature plasma membrane integrins. In contrast, very little is known about the targeting of newly synthesized integrins to the plasma membrane and their contribution to cell adhesion, spreading and FA dynamics. The relevance of integrin biosynthetic traffic is virtually unexplored and overlooked in the regulation of cell dynamics, predominantly owing to a lack of suitable methodology.

Integrins are a family of 24 heterodimeric cell-surface receptors composed of a larger α-subunit and a smaller β-subunit. The β1-subunit constitutes 12 integrin heterodimers, which mediate adhesion to a variety of ECM molecules (Chastney et al., 2020). Only relatively few studies have investigated integrin maturation and delivery to the plasma membrane. Early investigations exploring the regulation of integrin expression with pulse-chase metabolic labeling have shown that the rate of integrin heterodimer assembly and maturation is determined by the availability of integrin α-subunits (Heino et al., 1989). The β1-subunits are produced in an excess ratio and are retained in their immature form in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where they await to assemble with newly synthesized α-integrins (Heino et al., 1989; De Strooper et al., 1991; Lenter and Vestweber, 1994). In the ER, newly synthesized integrins bind to Ca2+, which maintains receptors in an inactive bent conformation until they reach the cell surface. Ca2+ depletion blocks the trafficking of α5β1-integrins from the ER to the Golgi (Tiwari et al., 2011). Talin plays an important role in trafficking of newly synthesized integrins, as talin depletion causes accumulation of α5β1-integrins in the early secretory pathway (Martel et al., 2000). How talin regulates exocytosis of newly synthesized integrins remains unknown, and other players in the regulation of integrin biosynthetic traffic are yet to be identified. To date, studies on newly synthesized integrins have been based on metabolic pulse-chase labeling and utilization of conformation-specific antibodies, which have limitations for real-time studies and visualization of integrin delivery. The development of the retention using selective hooks (RUSH) assay has permitted real-time tracking of newly synthesized proteins (Boncompain et al., 2012). A recent study employing this method concluded that post-Golgi carriers are not transported randomly to the cell surface. Instead exocytosis of versatile cargo is focused to areas close to FAs (Fourriere et al., 2019). However, whether this holds true for integrins and whether their delivery is influenced by specific ECM composition or ECM rigidity remains unknown.

Here, we have generated a fully functional, extracellularly tagged α5-integrin subunit and coupled it to the RUSH system to explore context-dependent traffic of newly synthesized fibronectin (FN)-binding α5β1-integrin to the plasma membrane. We demonstrate that (1) delivery of newly synthesized integrins to the plasma membrane is faster than previously thought; (2) their polarized delivery and ECM ligand–dependent recruitment to FAs facilitate dynamic cell responses to ECM cues providing an additional, thus far unrecognized level of integrin regulation; (3) a small subset of integrin α5 is delivered in a high-mannose glycosylation state to the plasma membrane via Golgi-bypass trafficking. These findings are the first demonstration of biosynthetic integrin traffic influencing FA maintenance and cell dynamics.

Results

Molecular simulation–guided generation of RUSH-α5

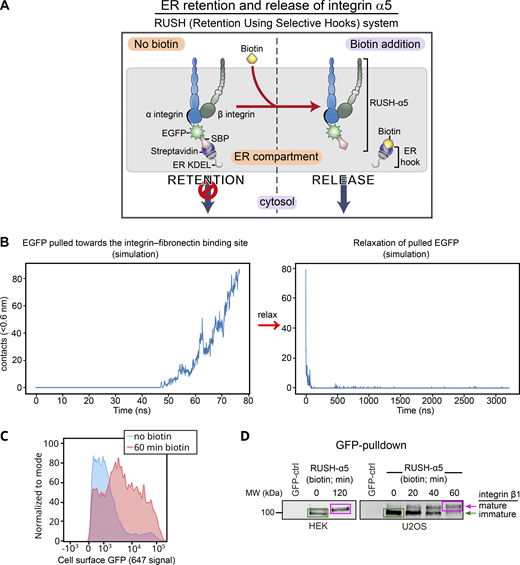

We employed the RUSH (retention using selective hooks) system (Boncompain et al., 2012), which has been previously used to synchronize and study post-Golgi anterograde trafficking of a variety of cargos (Boncompain et al., 2012; Fourriere et al., 2019; Weigel et al., 2021), to control integrin retention and release from the ER (Fig. S1 A). Using this method, we explored, for the first time, the context-dependent traffic of newly synthesized integrins and its implications in cell adhesion and dynamics in real time. Integrin α5β1 is the main FN receptor in many cell types and has been widely studied. Thus far, integrin α5β1 has been tagged on the C-terminal tail, potentially interfering with some established protein–protein interactions (Tuomi et al., 2009; Morse et al., 2014). To identify a suitable alternative tagging site on the receptor’s ectodomain, we examined the published crystal structure of the integrin α5β1 headpiece (Nagae et al., 2012). Given that the N-terminus of the α5 polypeptide is localized between the two integrin subunits, away from the FN ligand binding site, we inserted the IL-2 signal peptide, the streptavidin-binding peptide (SBP) and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in this region to generate an SBP-EGFP-integrin α5 construct (henceforth referred to as RUSH-α5) (Fig. 1 A, Fig. S1 A, and Video 1). Computational modeling suggested that while the flexible EGFP C-terminal region (plus linker) is just long enough to allow direct contact between EGFP and the FN ligand binding site (Fig. S1 B and Video 2), EGFP is stably positioned and cannot be displaced within the range of normal physical force. Atomistic simulations were consistent with these observations (Video 3; see Materials and methods for details). Thus, EGFP tagging of the integrin α5 ectodomain does not interfere with FN-binding or α5β1 subunit heterodimerization (Fig. S1 B; and Videos 1, 2, and 3). In cells, RUSH-α5 was retained in the ER when co-expressed with an ER-hook protein composed of the ER-retrieval motif KDEL fused to streptavidin (Fig. 1 B) and released upon biotin addition to be transported to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1 B; Fig. S1, A and C; and Video 4).

The RUSH system applied to integrin α5. (A) Principles of the RUSH-α5 integrin. In all experiments, SBP-EGFP-ITGA5 (RUSH-α5) is co-expressed with streptavidin-KDEL (ER-hook). In the absence of biotin, this combined complex is retained within the ER. Biotin addition displaces the ER-hook and releases RUSH-α5 into the cytoplasm. (B) The number of contacts between EGFP and FN during simulations of the coarse-grained model. Left: simulation of EGFP being pulled towards the FN-binding site, starting when the C-terminus of the EGFP and the N-terminus of the integrin α5 are <1 nm apart, the linker included, leading to the formation of contacts (Video 2 A). Right: simulation of a fully stretched EGFP, initially in close proximity to the FN-binding site, that is allowed to relax without a biasing force resulting in a spontaneous and rapid loss of contacts (<100 ns; Video 2 B). The pulling process spanned 8 nm and 80 ns. The relaxation spanned 3200 ns. Contacts were calculated between EGFP and FN with a cutoff of 0.6 nm. (C and D) RUSH-α5 is expressed on the cell surface and forms a functional heterodimer with integrin β1. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of cell surface RUSH-α5 levels (detected with the anti-GFP-AF647 antibody) in RUSH-α5–expressing U2OS cells ± biotin. (D) Representative immunoblots of GFP pulldowns performed in RUSH-α5 or control transfected cells ± biotin treatment for the indicated times and probed for endogenous integrin β1. The faster migrating band of immature integrin β1 is indicated by a green arrow and box and the slower migrating band of mature integrin β1 with a magenta arrow and box. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

The RUSH system applied to integrin α5. (A) Principles of the RUSH-α5 integrin. In all experiments, SBP-EGFP-ITGA5 (RUSH-α5) is co-expressed with streptavidin-KDEL (ER-hook). In the absence of biotin, this combined complex is retained within the ER. Biotin addition displaces the ER-hook and releases RUSH-α5 into the cytoplasm. (B) The number of contacts between EGFP and FN during simulations of the coarse-grained model. Left: simulation of EGFP being pulled towards the FN-binding site, starting when the C-terminus of the EGFP and the N-terminus of the integrin α5 are <1 nm apart, the linker included, leading to the formation of contacts (Video 2 A). Right: simulation of a fully stretched EGFP, initially in close proximity to the FN-binding site, that is allowed to relax without a biasing force resulting in a spontaneous and rapid loss of contacts (<100 ns; Video 2 B). The pulling process spanned 8 nm and 80 ns. The relaxation spanned 3200 ns. Contacts were calculated between EGFP and FN with a cutoff of 0.6 nm. (C and D) RUSH-α5 is expressed on the cell surface and forms a functional heterodimer with integrin β1. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of cell surface RUSH-α5 levels (detected with the anti-GFP-AF647 antibody) in RUSH-α5–expressing U2OS cells ± biotin. (D) Representative immunoblots of GFP pulldowns performed in RUSH-α5 or control transfected cells ± biotin treatment for the indicated times and probed for endogenous integrin β1. The faster migrating band of immature integrin β1 is indicated by a green arrow and box and the slower migrating band of mature integrin β1 with a magenta arrow and box. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

RUSH-α5 delivery to the plasma membrane is spatially regulated by the ECM. (A) Model of RUSH-α5 (EGFP-integrin α5)–integrin-β1 heterodimer based on the structure of human α5β1-integrin bound to FN (PDB: 7NWL) (see also Video 1). (B) Representative immunofluorescence timelapse images of a U2OS cell expressing RUSH-α5 (SBP-EGFP-integrin α5) and plated on FN ± biotin treatment (single grayscale images for the indicated time points are shown; see Video 4). (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of RUSH-α5 and active integrin α5β1 (SNAKA51 antibody) in RUSH-α5–expressing U2OS cells plated on FN or collagen + biotin (60 min). Grayscale single-channel images and merged images (white, colocalization; blue, nuclei [DAPI]) are shown. (D) Representative images of RUSH-α5 and RUSH-CD59 release in U2OS cells co-expressing both constructs and plated on dual-coated micropatterns (alternating FN coating (cyan) and collagen-peptide (GFOGER) (non-fluorescent) lines). Nuclei (blue) are co-labeled. Intensity line profiles generated across the yellow line are displayed relative to the position of the FN-coated micropattern lines. White insets represent regions of interest (ROIs) that are magnified for each channel. FN, fibronectin.

RUSH-α5 delivery to the plasma membrane is spatially regulated by the ECM. (A) Model of RUSH-α5 (EGFP-integrin α5)–integrin-β1 heterodimer based on the structure of human α5β1-integrin bound to FN (PDB: 7NWL) (see also Video 1). (B) Representative immunofluorescence timelapse images of a U2OS cell expressing RUSH-α5 (SBP-EGFP-integrin α5) and plated on FN ± biotin treatment (single grayscale images for the indicated time points are shown; see Video 4). (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of RUSH-α5 and active integrin α5β1 (SNAKA51 antibody) in RUSH-α5–expressing U2OS cells plated on FN or collagen + biotin (60 min). Grayscale single-channel images and merged images (white, colocalization; blue, nuclei [DAPI]) are shown. (D) Representative images of RUSH-α5 and RUSH-CD59 release in U2OS cells co-expressing both constructs and plated on dual-coated micropatterns (alternating FN coating (cyan) and collagen-peptide (GFOGER) (non-fluorescent) lines). Nuclei (blue) are co-labeled. Intensity line profiles generated across the yellow line are displayed relative to the position of the FN-coated micropattern lines. White insets represent regions of interest (ROIs) that are magnified for each channel. FN, fibronectin.

Rotating model of RUSH-α5 (EGFP-integrin α5)–integrin-β1 heterodimer bound to FN based on (PDB: 7NWL) structure of the heterodimer. Related to Fig. 1 A.

Rotating model of RUSH-α5 (EGFP-integrin α5)–integrin-β1 heterodimer bound to FN based on (PDB: 7NWL) structure of the heterodimer. Related to Fig. 1 A.

Coarse-grained model simulation depicting pulling of EGFP towards fibronectin binding site and spontaneous relaxation of the final pulled state. (A) Coarse-grained model, pulling of EGFP towards the FN-binding site. The pulling between the EGFP and the FN-binding site starts from the situation where the C-terminus of the EGFP and the N-terminus of the integrin alpha are <1 nm apart, including the linker. The movie is divided into three parts. It starts with a full rotation around the initial configuration. Then, the pulling is performed (at a constant rate with 1,000 kJ mol−1 nm−2 at 0.1 nm/ns). Finally, shown is a full rotation around the final state, later used as the first frame for relaxation in Video 2 B. The movie repeats itself in reverse. EGFP is blue, the linker is red, and integrin alpha is orange (one molecule). Integrin beta is yellow, and FN is green. The pulling process spans 8 nm and 80 ns. (B) Coarse-grained simulation model, spontaneous (non-biased) relaxation of the final pulled state of Video 2 A. Contacts (<0.6 nm distance) between the EGFP and FN are indicated with magenta (Fig. S1 B). EGFP is blue, the linker is red, and integrin alpha is orange (one molecule). Integrin beta is yellow, and FN is green. The relaxation spans 3,200 ns.

Coarse-grained model simulation depicting pulling of EGFP towards fibronectin binding site and spontaneous relaxation of the final pulled state. (A) Coarse-grained model, pulling of EGFP towards the FN-binding site. The pulling between the EGFP and the FN-binding site starts from the situation where the C-terminus of the EGFP and the N-terminus of the integrin alpha are <1 nm apart, including the linker. The movie is divided into three parts. It starts with a full rotation around the initial configuration. Then, the pulling is performed (at a constant rate with 1,000 kJ mol−1 nm−2 at 0.1 nm/ns). Finally, shown is a full rotation around the final state, later used as the first frame for relaxation in Video 2 B. The movie repeats itself in reverse. EGFP is blue, the linker is red, and integrin alpha is orange (one molecule). Integrin beta is yellow, and FN is green. The pulling process spans 8 nm and 80 ns. (B) Coarse-grained simulation model, spontaneous (non-biased) relaxation of the final pulled state of Video 2 A. Contacts (<0.6 nm distance) between the EGFP and FN are indicated with magenta (Fig. S1 B). EGFP is blue, the linker is red, and integrin alpha is orange (one molecule). Integrin beta is yellow, and FN is green. The relaxation spans 3,200 ns.

Atomistic simulations of EGFP tagged integrin α5β1 bound to fibronectin. (A) Fully atomistic molecular dynamics simulation of the EGFP attached to the α-subunit of the integrin molecule. The movie depicts a demonstrative simulation of the EGFP (in green) bound to the α-subunit (blue) of integrin. The β-subunit is shown in red color. The FN bound to integrin is shown in gray. No additional forces were applied in this simulation. The simulation is 100 ns long. (B) Fully atomistic steered molecular dynamics simulation of the EGFP attached to the α-subunit of the integrin molecule. The movie depicts a demonstrative simulation of the EGFP (in green) bound to the α-subunit (blue) of integrin. The EGFP is pulled towards the FN (gray) binding site with a force of 25 kJ/mol/nm2. The β-subunit on integrin is shown in red. The simulation is 100 ns long. (C) Fully atomistic steered molecular dynamics simulation of the EGFP attached to the α-subunit of the integrin molecule. The movie depicts a demonstrative simulation of the EGFP (in green) bound to the α-subunit (blue) of integrin. The EGFP is pulled towards the FN (gray) binding site with a force of 50 kJ/mol/nm2. The β-subunit on integrin is shown in red. The simulation is 100 ns long.

Atomistic simulations of EGFP tagged integrin α5β1 bound to fibronectin. (A) Fully atomistic molecular dynamics simulation of the EGFP attached to the α-subunit of the integrin molecule. The movie depicts a demonstrative simulation of the EGFP (in green) bound to the α-subunit (blue) of integrin. The β-subunit is shown in red color. The FN bound to integrin is shown in gray. No additional forces were applied in this simulation. The simulation is 100 ns long. (B) Fully atomistic steered molecular dynamics simulation of the EGFP attached to the α-subunit of the integrin molecule. The movie depicts a demonstrative simulation of the EGFP (in green) bound to the α-subunit (blue) of integrin. The EGFP is pulled towards the FN (gray) binding site with a force of 25 kJ/mol/nm2. The β-subunit on integrin is shown in red. The simulation is 100 ns long. (C) Fully atomistic steered molecular dynamics simulation of the EGFP attached to the α-subunit of the integrin molecule. The movie depicts a demonstrative simulation of the EGFP (in green) bound to the α-subunit (blue) of integrin. The EGFP is pulled towards the FN (gray) binding site with a force of 50 kJ/mol/nm2. The β-subunit on integrin is shown in red. The simulation is 100 ns long.

Time lapse spinning-disk confocal imaging of RUSH-α5–expressing U2OS cell plated on FN (10 µg/ml), biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per minute. Related to Fig. 1 B.

Time lapse spinning-disk confocal imaging of RUSH-α5–expressing U2OS cell plated on FN (10 µg/ml), biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per minute. Related to Fig. 1 B.

ECM control of integrin delivery to the plasma membrane

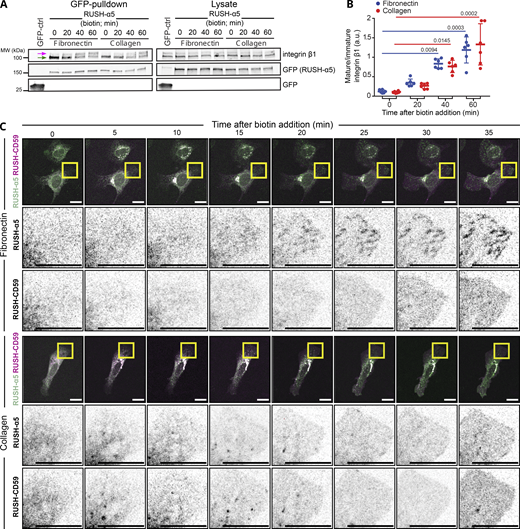

In cells, integrin β1 subunits are produced in excess and are transported to the plasma membrane only upon heterodimerization with newly synthesized α-integrins (Heino et al., 1989; De Strooper et al., 1991; Lenter and Vestweber, 1994). To investigate the ability of RUSH-α5 to form functional heterodimers with the β1 subunit, we performed GFP pulldown in cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 and the ER-hook (ER-hook always expressed with RUSH-α5 in all experiments) with and without biotin addition. The EGFP-tagged RUSH-α5 precipitated endogenous β1 integrin. RUSH-α5 interacted with the immature integrin β1 (faster migrating lower band; Fig. S1 D) before release from the ER (0 min biotin), and progressively with the mature integrin β1 after release from the ER following biotin addition (slower migrating upper band; Fig. S1 D). Importantly, RUSH-α5, when released from the ER (60 min biotin), localized to fibrillar and FA-like structures on FN that were positive for active integrin α5 (detected with active integrin α5 conformation-specific SNAKA51 antibody) (Fig. 1 C). In contrast, RUSH-α5 displayed a clearly reduced localization to adhesion structures along with a more diffuse localization pattern in cells plated on collagen and treated with biotin (Fig. 1 C). The ECM ligand did not dramatically influence integrin heterodimer maturation (increasing ratio of mature to immature integrin β1) as it was not significantly faster on FN than on collagen 20 and 40 min after biotin addition (Fig. S2, A and B).

RUSH-α5 recruitment to adhesions is ligand-dependent. (A) Representative immunoblot of GFP pulldowns performed in RUSH-α5 or control transfected cells plated on FN or collagen and probed for endogenous integrin β1 and for GFP. Mature (magenta arrow) and immature (green arrow) integrin β1 are indicated. (B) Quantification of the relative fraction of mature to immature integrin β1 interacting with RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. N = 6 independent experiments; data are mean ± SD, One-way ANOVA, Dunn’s multiple comparison test, no significant difference between FN and collagen at all time points. (C) Representative images (see Video 5) of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 and RUSH-CD59 and plated on FN (top) or collagen (bottom) ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Insets represent ROIs that are magnified. Scale bars: 20 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

RUSH-α5 recruitment to adhesions is ligand-dependent. (A) Representative immunoblot of GFP pulldowns performed in RUSH-α5 or control transfected cells plated on FN or collagen and probed for endogenous integrin β1 and for GFP. Mature (magenta arrow) and immature (green arrow) integrin β1 are indicated. (B) Quantification of the relative fraction of mature to immature integrin β1 interacting with RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. N = 6 independent experiments; data are mean ± SD, One-way ANOVA, Dunn’s multiple comparison test, no significant difference between FN and collagen at all time points. (C) Representative images (see Video 5) of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 and RUSH-CD59 and plated on FN (top) or collagen (bottom) ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Insets represent ROIs that are magnified. Scale bars: 20 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

Our real-time measurements revealed, however, an interesting and unexpected feature of integrin maturation and delivery. Metabolic labeling studies have indicated receptor maturation kinetics exceeding 1 h for the total integrin β1 cellular pool (Heino et al., 1989; Tiwari et al., 2011). These pulse-labeling methods analyze synthesis, folding and secretion of integrins, and cannot be directly compared with the RUSH-method. However, our data here reveals that α5β1-integrin secretion and maturation can be detected already 20 min after integrin release from the ER (Fig. S2, A and B). Taken together, these data indicate that RUSH-α5 forms a functional heterodimer with endogenous integrin β1, undergoes ligand-specific activation on FN, and the dynamics and kinetics of the newly synthesized integrin can be analyzed using this method.

To explore the kinetics of the biosynthetic delivery of integrins in more detail, we performed time-lapse imaging of RUSH-α5 release in cells plated on collagen and FN, comparing it with the dynamics of a co-expressed SBP- and mCherry-tagged control cargo protein CD59 (glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins cluster of differentiation 59) (Boncompain et al., 2012), henceforth called RUSH-CD59. On both ECMs, RUSH-α5 and RUSH-CD59 were localized to the ER in the absence of biotin, and following biotin addition were released and transported to the Golgi, residing there for ∼15 min (Fig. S2 C), in line with previous reports for CD59 (Boncompain et al., 2012; Fourriere et al., 2019). After 20 min, RUSH-α5 was predominantly localized on adhesion-like structures on FN whereas on collagen it was diffusely distributed on the plasma membrane (Fig. S2 C and Video 5). In contrast, the RUSH-CD59 construct behaved similarly on both FN and collagen (Fig. S2 C and Video 5), indicating that the observed differences in RUSH-α5 localization in cells on FN and collagen were ligand-receptor specific. This was further validated by plating RUSH-α5 and RUSH-CD59 co-transfected cells on dual-coated micropatterns (Isomursu et al., 2024) with alternating lines of FN and GFOGER (a synthetic collagen peptide with high affinity for collagen-binding integrins [Zhang et al., 2003]). Following release (20-min biotin), RUSH-α5 localized predominantly to the cell edges, showing enriched clustering on FN-coated lines, compared to GFOGER-coated lines (Fig. 1 D). In contrast, RUSH-CD59 localization was independent of ligand coating. This implies that the integrin is largely delivered directly to the FN areas. However, as we are focusing only on the ventral surface of cells, we cannot exclude the possibility that integrin α5 could be delivered first on the dorsal surface of the cells and then diffuse to the ventral surface into FAs. Next, we examined RUSH-α5 targeting to adhesions by co-expressing pmKate2-paxillin as a FA marker. RUSH-α5 was localized to pmKate2-paxillin-positive adhesions as early as 20 min following release with biotin, and this localization increased over time (Fig. 2, A and B). On collagen, RUSH-α5 localization to adhesions was significantly lower compared to FN (Fig. 2, A and B), with the increase in intensity at the later time point most likely reflecting the increased presence of the diffused receptor on the membrane. We then replaced the EGFP in RUSH-α5 with pHluorin, a pH sensitive GFP (Miesenböck et al., 1998), to image RUSH-α5 cell surface delivery. The pHluorin GFP is non-fluorescent in acidic secretory vesicles and becomes fluorescent upon cell surface exposure. To detect the localization of RUSH-α5 secretion, we prevented receptor diffusion after ventral plasma membrane delivery by employing the selective protein immobilization (SPI) method (Fourriere et al., 2019). The ECM proteins were coated alongside anti-GFP antibodies, which bind to the GFP moiety in RUSH-α5 and trap the receptor when it is delivered to the cell surface. In cells co-transfected with RUSH-α5-pHluorin and paxillin-mScarlet, we observed a specific increase in pHluorin signal in FAs over time (Fig. S3 A). Moreover, TIRF live imaging of the RUSH-α5-pHluorin showed fluorescent flashes corresponding to RUSH-α5 surface delivery. These exocytosis events were significantly closer to FAs compared to those of randomly generated points (Fig. 2 C and Video 6). These results indicate that RUSH-α5 is predominantly delivered to FA sites on FN. In addition, it is possible that some of the integrin is transported elsewhere on the plasma membrane and rapidly diffuses to the FN-specific adhesions further contributing to FA formation by the newly synthesized integrin.

Time lapse spinning-disk confocal imaging of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 (green) and RUSH-CD59 (magenta) and plated on FN (left, 10 µg/ml) or collagen (right, 10 µg/ml), biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per 30 s. Related to Fig. S2 C.

Time lapse spinning-disk confocal imaging of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 (green) and RUSH-CD59 (magenta) and plated on FN (left, 10 µg/ml) or collagen (right, 10 µg/ml), biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per 30 s. Related to Fig. S2 C.

RUSH-α5 delivery to FAs. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 and pmKate2-Paxillin plated on FN or collagen ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Insets represent ROIs that are magnified and show paxillin-segmented adhesions (red outlines). (B) Quantification of the relative mean intensity of RUSH-α5 in segmented adhesions/cell ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Data are mean ± SD; n = 64 cells on collagen, 50 cells on FN, pooled from three independent experiments; One-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparison test; data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (C) TIRF imaging of U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5-pHluorin on a FN-coated surface after biotin release at T = 0. The arrows indicate exocytosis events. Exocytosis events were detected by performing a ratiometric analysis, which consisted of dividing each frame by the previous. All detected events before 19 min of release are indicated in red. The graph indicates the distance between the exocytosis events and the nearest FA segmented on the last frame of Video 6 (37 min after release), compared to the distance of random dots to FAs, showing that the localization to FAs is not random. Individual measurements and the mean ± SD are represented. Unpaired T test. RUSH-α5-pHluorin spots n = 336 spots, random spots n = 116 spots from one experiment.

RUSH-α5 delivery to FAs. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 and pmKate2-Paxillin plated on FN or collagen ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Insets represent ROIs that are magnified and show paxillin-segmented adhesions (red outlines). (B) Quantification of the relative mean intensity of RUSH-α5 in segmented adhesions/cell ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Data are mean ± SD; n = 64 cells on collagen, 50 cells on FN, pooled from three independent experiments; One-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparison test; data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (C) TIRF imaging of U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5-pHluorin on a FN-coated surface after biotin release at T = 0. The arrows indicate exocytosis events. Exocytosis events were detected by performing a ratiometric analysis, which consisted of dividing each frame by the previous. All detected events before 19 min of release are indicated in red. The graph indicates the distance between the exocytosis events and the nearest FA segmented on the last frame of Video 6 (37 min after release), compared to the distance of random dots to FAs, showing that the localization to FAs is not random. Individual measurements and the mean ± SD are represented. Unpaired T test. RUSH-α5-pHluorin spots n = 336 spots, random spots n = 116 spots from one experiment.

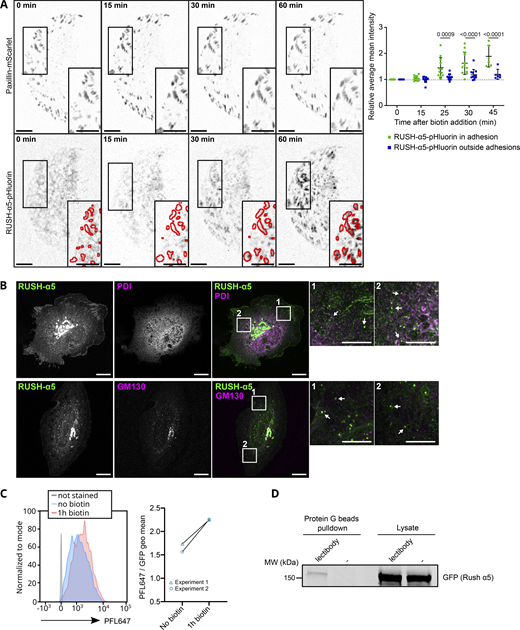

RUSH-α5 delivery and localization following release. (A) RUSH-α5-pHluorin released in U2OS co-expressing Paxillin-mScarlet on FN- and anti-GFP antibody-coated surfaces. The intensity of RUSH-α5-pHluorin signal was quantified in and outside adhesions (paxillin positive, represented in the insets). Data are mean ± SD, N = 12 cells (N = 6 cells from 1 experiment for T = 45 min), pooled from 2 independent experiments. Ordinary one-way Anova with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test; data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Scale bars: 10 µm (main and insets). (B) High resolution imaging of RUSH-α5 after 15 min of release in U2OS. PDI (ER marker) or GM130 (Golgi marker) are co-stained. Arrows in the insets indicate RUSH-α5 positive vesicles. Scale bar: 10 µm (main), 5 µm (insets). (C and D) High-mannose integrin-α5 is delivered to the cell surface. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of high-mannose proteins at the cell surface detected with the fluorescent lectin PFL647 in U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5, without release and 1 h after release. The left panel shows histograms of one experiment, the right panel shows the geometric fluorescence mean of the PFL647 signal for individual experiments (N = 2 independent experiments). (D) U2OS expressing RUSH-α5 were labeled at their surface after 1 h release with a lectibody specifically recognizing high-mannose proteins. The lectibody was then pulled down by protein G beads. This Western blot shows GFP detection in the pull-down, indicating the presence of high-mannose RUSH-α5 at the cell surface after release. Representative of N = 3 independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

RUSH-α5 delivery and localization following release. (A) RUSH-α5-pHluorin released in U2OS co-expressing Paxillin-mScarlet on FN- and anti-GFP antibody-coated surfaces. The intensity of RUSH-α5-pHluorin signal was quantified in and outside adhesions (paxillin positive, represented in the insets). Data are mean ± SD, N = 12 cells (N = 6 cells from 1 experiment for T = 45 min), pooled from 2 independent experiments. Ordinary one-way Anova with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test; data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Scale bars: 10 µm (main and insets). (B) High resolution imaging of RUSH-α5 after 15 min of release in U2OS. PDI (ER marker) or GM130 (Golgi marker) are co-stained. Arrows in the insets indicate RUSH-α5 positive vesicles. Scale bar: 10 µm (main), 5 µm (insets). (C and D) High-mannose integrin-α5 is delivered to the cell surface. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of high-mannose proteins at the cell surface detected with the fluorescent lectin PFL647 in U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5, without release and 1 h after release. The left panel shows histograms of one experiment, the right panel shows the geometric fluorescence mean of the PFL647 signal for individual experiments (N = 2 independent experiments). (D) U2OS expressing RUSH-α5 were labeled at their surface after 1 h release with a lectibody specifically recognizing high-mannose proteins. The lectibody was then pulled down by protein G beads. This Western blot shows GFP detection in the pull-down, indicating the presence of high-mannose RUSH-α5 at the cell surface after release. Representative of N = 3 independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

Time lapse TIRF imaging of U2OS expressing RUSH-α5-pHluorin plated on FN-coated surface. Left: RUSH-α5-pHluorin. Right: ratiometric analysis, the exocytosis spots appear in yellow. Scale bar: 20 µm. One frame per 10 s. Related to Fig. 2 C.

Time lapse TIRF imaging of U2OS expressing RUSH-α5-pHluorin plated on FN-coated surface. Left: RUSH-α5-pHluorin. Right: ratiometric analysis, the exocytosis spots appear in yellow. Scale bar: 20 µm. One frame per 10 s. Related to Fig. 2 C.

Polarized delivery of new integrin to the cell protruding edge

We then investigated if the localization of newly synthesized integrins is polarized. First, we plated RUSH-α5 transfected cells on 9 µm-wide collagen or FN micropatterned lines (in combination with the GFP-SPI method to prevent RUSH-α5 diffusion after delivery), shown previously to support front-rear cell polarity of integrins (Shafaq-Zadah et al., 2016). Time-lapse imaging revealed a significant increase in RUSH-α5 intensity on FN over time preferentially at the protruding edge of the cell (region of interest 1; ROI1) (Fig. 3, A and B; and Video 7) whereas, on collagen lines, the difference in RUSH-α5 localization between the 2 cell edges was modest and apparent only at later time points (Fig. 3, A and C; and Video 8). In line with these data, RUSH-α5 delivery was also polarized on FN in unconstrained cells, occurring significantly more in protruding regions, whereas on collagen RUSH-α5 intensity increased both in retracting and protruding regions (protruding or retracting areas of the cells defined based on spatiotemporal track maps (Baniukiewicz et al., 2018), generated from paxillin images) (Fig. 3, D and E). These data indicate that the plasma membrane delivery of newly synthesized integrins is sensitive to ECM ligand engagement and the cell front-rear polarity.

Polarized delivery of newly synthesized integrin to the cell protruding edge. (A–C) RUSH-α5 intensity in U2OS cells plated on 9 µm-wide micropatterns coated with FN and anti-GFP or collagen and anti-GFP ± biotin treatment for the indicated times was analyzed at both cell edges (the predominantly protruding edge was denoted ROI1 and the other edge ROI2; Videos 7 and 8). Representative intensity coded images (A) and quantification of RUSH-α5 release on FN (B; Video 7) and collagen (C; Video 8) (normalized first to the total intensity of the cell and then to 0 min biotin) are shown. Data are mean ± SEM. (D) Representative images and spatiotemporal track maps of cell edge contours over time in U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Red insets represent protruding ROIs that are magnified. Blue insets represent retracting ROIs that are magnified. Spatiotemporal track maps: blue colors represent early time points and magenta colors represent late time points in the time-lapse series. (E) Quantifications of RUSH-α5 intensity in ROIs (retracting or protruding areas determined from spatiotemporal track maps). Data are mean ± SD. (B and C)N = 33 cells on FN and 38 cells on collagen, pooled from three independent experiments, two-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparison test. (E)N = 53 cells on collagen, 49 cells on FN, pooled from three independent experiments; one-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test; data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested.

Polarized delivery of newly synthesized integrin to the cell protruding edge. (A–C) RUSH-α5 intensity in U2OS cells plated on 9 µm-wide micropatterns coated with FN and anti-GFP or collagen and anti-GFP ± biotin treatment for the indicated times was analyzed at both cell edges (the predominantly protruding edge was denoted ROI1 and the other edge ROI2; Videos 7 and 8). Representative intensity coded images (A) and quantification of RUSH-α5 release on FN (B; Video 7) and collagen (C; Video 8) (normalized first to the total intensity of the cell and then to 0 min biotin) are shown. Data are mean ± SEM. (D) Representative images and spatiotemporal track maps of cell edge contours over time in U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Red insets represent protruding ROIs that are magnified. Blue insets represent retracting ROIs that are magnified. Spatiotemporal track maps: blue colors represent early time points and magenta colors represent late time points in the time-lapse series. (E) Quantifications of RUSH-α5 intensity in ROIs (retracting or protruding areas determined from spatiotemporal track maps). Data are mean ± SD. (B and C)N = 33 cells on FN and 38 cells on collagen, pooled from three independent experiments, two-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparison test. (E)N = 53 cells on collagen, 49 cells on FN, pooled from three independent experiments; one-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test; data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested.

Time lapse spinning-disk confocal imaging of U2OS expressing RUSH-α5 plated on 9 µm-wide FN and anti-GFP-coated micropattern lines. Biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per minute. Related to Fig. 3, A and B.

Time lapse spinning-disk confocal imaging of U2OS expressing RUSH-α5 plated on 9 µm-wide FN and anti-GFP-coated micropattern lines. Biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per minute. Related to Fig. 3, A and B.

Time lapse imaging of spinning-disk confocal U2OS expressing RUSH-α5 plated on 9 µm-wide collagen and anti-GFP-coated micropattern lines. Biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per minute. Related to Fig. 3, A and C.

Time lapse imaging of spinning-disk confocal U2OS expressing RUSH-α5 plated on 9 µm-wide collagen and anti-GFP-coated micropattern lines. Biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per minute. Related to Fig. 3, A and C.

Rapid, adhesion-dependent delivery of RUSH-α5

While RUSH-α5 was predominantly trafficked to the plasma membrane via the Golgi complex conventional secretion pathway, a process that takes more than 20 min, surprisingly, some RUSH-α5–positive vesicles were evident earlier (around 10 min) within the vicinity of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4 A and Video 9). This was also apparent using TIRF live imaging where the RUSH-α5 signal was detected at the cell-ECM interface already at 13 min post release. After 15 min surface delivery was clearly polarized to the cell leading-edge protruding area (Fig. 4 B and Video 10). Moreover, using pHluorin-RUSH-α5, we were able to observe exocytosis events from 10 min after release (Fig. 2 C and Video 6). This unexpected early plasma membrane delivered integrin localized to FN-line micropatterns unlike the RUSH-CD59 construct (Fig. 4 C). Cell surface delivery of RUSH-α5 was also detected with flow cytometry 15 min after biotin addition with a steady increase up to 1 h (Fig. 4 D). Live imaging of RUSH-α5 together with an ER marker (ERoxBFP) revealed RUSH-α5 puncta outside of the ER and being trafficked in close proximity to FAs at very early time points (Video 9). High resolution confocal imaging of cells transfected with RUSH-α5 after 10 min of release showed no obvious overlap between RUSH-α5 vesicles and Golgi or ER makers (Fig. S3 B). These observations suggest that at least some of the RUSH-α5 is delivered to the plasma membrane without going through the Golgi apparatus.

Early delivery of RUSH-α5 to the cell surface. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 (green) and the ER marker ERoxBFP (magenta) plated on FN (10 µg/ml) ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Arrows indicate rapidly budding RUSH-α5–positive vesicles adjacent to cell protrusions (≤15 min after release) (see also Video 9). (B) TIRF imaging of RUSH-α5 after release (0 min). The polarized delivery to the cell surface at the protruding area can be observed from 15 min after release (see also Video 10). (C) Representative images of RUSH-α5 (green) and RUSH-CD59 (magenta) release in U2OS cells co-expressing both constructs and plated on dual-coated micropatterns (alternating FN coating (cyan) and collagen-peptide (GFOGER) (non-fluorescent) lines). Nuclei (blue) are co-labeled. White insets represent ROIs that are magnified for each channel. FN, fibronectin. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface RUSH-α5 levels (detected with the anti-GFP-AF647 antibody) in RUSH-α5–expressing U2OS cells ± biotin. Representative histograms and quantification from two independent experiments of cell surface GFP (ratio of the geometric means of the surface signal divided by the total GFP signal, normalized by subtracting the 0 min value) are shown.

Early delivery of RUSH-α5 to the cell surface. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 (green) and the ER marker ERoxBFP (magenta) plated on FN (10 µg/ml) ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Arrows indicate rapidly budding RUSH-α5–positive vesicles adjacent to cell protrusions (≤15 min after release) (see also Video 9). (B) TIRF imaging of RUSH-α5 after release (0 min). The polarized delivery to the cell surface at the protruding area can be observed from 15 min after release (see also Video 10). (C) Representative images of RUSH-α5 (green) and RUSH-CD59 (magenta) release in U2OS cells co-expressing both constructs and plated on dual-coated micropatterns (alternating FN coating (cyan) and collagen-peptide (GFOGER) (non-fluorescent) lines). Nuclei (blue) are co-labeled. White insets represent ROIs that are magnified for each channel. FN, fibronectin. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface RUSH-α5 levels (detected with the anti-GFP-AF647 antibody) in RUSH-α5–expressing U2OS cells ± biotin. Representative histograms and quantification from two independent experiments of cell surface GFP (ratio of the geometric means of the surface signal divided by the total GFP signal, normalized by subtracting the 0 min value) are shown.

Time lapse spinning-disk confocal imaging of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 (green) and the ER marker ERoxBFP (magenta) plated on FN (10 µg/ml), biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per 30 s. Related to Fig. 4 A.

Time lapse spinning-disk confocal imaging of U2OS cells co-expressing RUSH-α5 (green) and the ER marker ERoxBFP (magenta) plated on FN (10 µg/ml), biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min. One frame per 30 s. Related to Fig. 4 A.

Time lapse imaging of U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 plated on FN (10 µg/ml), biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min, imaged by TIRF microscopy. One frame per 30 s. Related to Fig. 4 B.

Time lapse imaging of U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 plated on FN (10 µg/ml), biotin added after acquisition of time point 0 min, imaged by TIRF microscopy. One frame per 30 s. Related to Fig. 4 B.

Integrin rapid delivery bypasses conventional Golgi secretion

These data prompted us to hypothesize that a small proportion of integrins could undergo unconventional protein secretion (UPS), a process where secretory proteins are transported from the ER to the plasma membrane without entering the Golgi complex (Rabouille, 2017). Conventional Golgi secretion is inhibited by Golgicide A (Sáenz et al., 2009). Therefore, we treated cells with Golgicide A to investigate the relative contribution of the Golgi complex to RUSH-α5 trafficking. As expected, the delivery of the majority of RUSH-α5, 25 min post-biotin addition, was significantly inhibited by Golgicide A (Fig. 5, A and B). However, both control and Golgicide A-treated cells showed a small initial increase in RUSH-α5 recruitment to protruding areas of the cell and to adhesions 15 min after release (Fig. 5, A and B), suggesting that a small fraction of newly synthesized integrins may be secreted to FAs via a mechanism that bypasses conventional Golgi secretion.

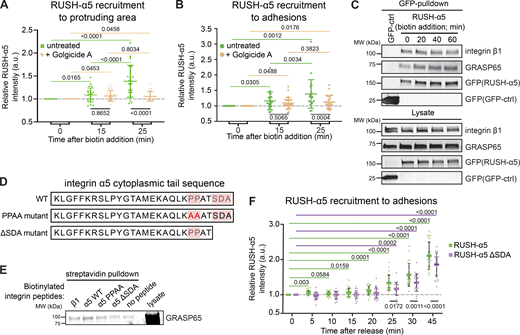

Golgi bypass early delivery of RUSH-α5 requires the integrin-α5 PDZ-binding motif. (A and B) Quantification of relative RUSH-α5 recruitment to protruding areas (A) or adhesions (B) in U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times with or without Golgicide A (10 µM). (C) Representative immunoblot of GFP pulldowns from RUSH-α5 or GFP control transfected cells plated on FN and probed for GFP and endogenous GRASP65. N = 3 independent experiments. (D) Amino acid sequence of the integrin α5 tail highlighting the canonical PDZ-binding motif (SDA) and the two proline residues critical for the formation of the non-canonical PDZ-binding motif. The mutations of these sites used in our experiments are indicated below. (E) Representative streptavidin pulldowns of the indicated biotinylated recombinant integrin peptides incubated with cell lysates collected from CHO cells overexpressing GFP-GRASP65. A representative immunoblot probed for GRASP65 (note, two bands are present in the lysate: upper, GFP-GRASP65; lower, endogenous GRASP65; GFP-GRASP65 is apparent in the pulldown). N = 3 independent experiments. (F) Quantification of RUSH-α5 or RUSH-α5 ΔSDA recruitment to adhesions in U2OS cells ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. All data are mean ± SD. (A and B) One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test for comparing time points, one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test for comparing untreated and Golgicide A, data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (A)N = 26 cells RUSH-α5, N = 22 cells RUSH-α5 Golgicide A, pooled from three independent experiments. (B)N = 24 cells RUSH-α5, N = 27 cells RUSH-α5 Golgicide A, pooled from three independent experiments. (F) One sample t test to compare time points with T = 0, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test to compare RUSH-α5 and RUSH-α5 ΔSDA, data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. N = 23 cells RUSH-α5, N = 23 cells RUSH-α5 ΔSDA, pooled from two independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Golgi bypass early delivery of RUSH-α5 requires the integrin-α5 PDZ-binding motif. (A and B) Quantification of relative RUSH-α5 recruitment to protruding areas (A) or adhesions (B) in U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times with or without Golgicide A (10 µM). (C) Representative immunoblot of GFP pulldowns from RUSH-α5 or GFP control transfected cells plated on FN and probed for GFP and endogenous GRASP65. N = 3 independent experiments. (D) Amino acid sequence of the integrin α5 tail highlighting the canonical PDZ-binding motif (SDA) and the two proline residues critical for the formation of the non-canonical PDZ-binding motif. The mutations of these sites used in our experiments are indicated below. (E) Representative streptavidin pulldowns of the indicated biotinylated recombinant integrin peptides incubated with cell lysates collected from CHO cells overexpressing GFP-GRASP65. A representative immunoblot probed for GRASP65 (note, two bands are present in the lysate: upper, GFP-GRASP65; lower, endogenous GRASP65; GFP-GRASP65 is apparent in the pulldown). N = 3 independent experiments. (F) Quantification of RUSH-α5 or RUSH-α5 ΔSDA recruitment to adhesions in U2OS cells ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. All data are mean ± SD. (A and B) One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test for comparing time points, one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test for comparing untreated and Golgicide A, data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (A)N = 26 cells RUSH-α5, N = 22 cells RUSH-α5 Golgicide A, pooled from three independent experiments. (B)N = 24 cells RUSH-α5, N = 27 cells RUSH-α5 Golgicide A, pooled from three independent experiments. (F) One sample t test to compare time points with T = 0, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparisons test to compare RUSH-α5 and RUSH-α5 ΔSDA, data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. N = 23 cells RUSH-α5, N = 23 cells RUSH-α5 ΔSDA, pooled from two independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

In normal cells, high-mannose-type glycans are predominantly localized to the ER, and undergo enzymatic processing and maturation into complex glycoforms in the Golgi during conventional secretion (Ungar, 2009). However, several cancer types and cancer patient samples show significantly increased proportions of high-mannose glycans on the cell surface (Liu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015) and unbiased probing with high-mannose binding lectins have shown that integrins are abundant in this receptor pool (Oh et al., 2022). This prompted us to investigate the presence of high-mannose glycans at the cell surface. We used the fluorescently labeled Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1lectin (PFL), which specifically binds to high-mannose glycans (Sato et al., 2012) to stain the surface of RUSH-α5 transfected cells before and after release (1 h). We observed increased PFL staining after release, indicating delivery of high-mannose proteins to the cell surface (Fig. S3 C). To explore this further, we took an orthogonal approach and labeled the surface of RUSH-α5 cells after biotin addition (1 h release) with a high-mannose specific antibody-like lectibody molecule (Oh et al., 2022; Hamorsky et al., 2019) and subsequently performed lectibody pulldowns. We detected RUSH-α5 in these pulldowns, indicative of high-mannose α5-integrin expression on the cell surface (Fig. S3 D).

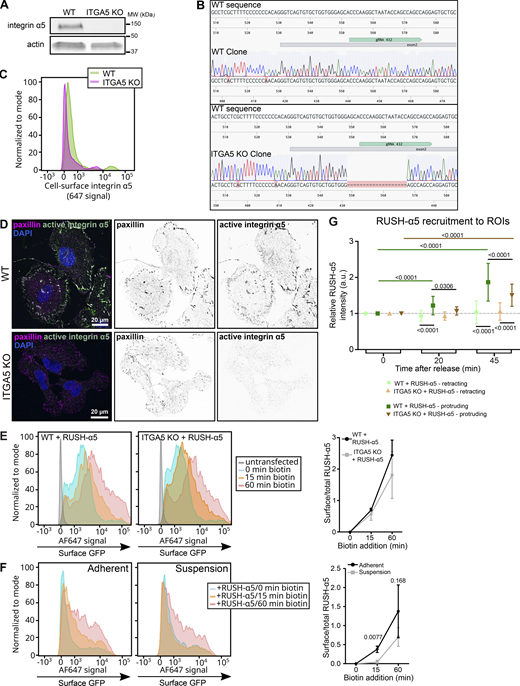

While cell surface high-mannose bearing integrins have been reported in cancer cells (Liu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015), insights into the relevance of Golgi bypass has been limited to the integrin αPS1 subunit during Drosophila follicle epithelium development, stimulated by mechanical stress (Schotman et al., 2009). This prompted us to investigate whether early secretion of newly synthetized integrins in mammalian cells is linked to cell adhesion and adhesion-induced mechanics. First, we explored whether preexisting endogenous integrin α5 adhesions are involved. We knocked-out endogenous integrin α5 (ITGA5) (Fig. S4, A–D) and compared RUSH-α5 release in wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) cells after 15 and 60 min biotin addition (note that U2OS cells have other FN-binding integrins in addition to integrin α5 and thus the KO cells adhere to FN similarly to control cells). RUSH-α5 delivery to the cell surface was comparable between WT and ITGA5 KO cells (Fig. S4 E). Thus, the early secretion of newly synthesized integrin α5 is not dependent on the localization of the endogenous protein already at the cell surface. However, the early delivery of RUSH-α5 to the plasma membrane was dependent on cell-ECM adhesion, as we did not detect RUSH-α5 at the cell surface after 15 min biotin addition in suspension cells (Fig. S4 F). Adhesion was not required for slower integrin secretion (60 min biotin) via the conventional pathway (Fig. S4 F). These data are consistent with cell adhesion and perhaps active spreading/protrusions acting as necessary triggers for early secretion of integrin α5 to the cell surface. Even though the early delivery of RUSH-α5 was not, as such, dependent on endogenous integrin α5, polarized RUSH-α5 localization to cell protruding areas was significantly higher in WT compared to ITGA5 KO cells (Fig. S4 G), suggesting that polarized localization of the newly synthesized integrin is orchestrated by existing adhesions and contributes to rapid alterations in cell shape.

Early release of RUSH-α5 is adhesion dependent and polarized recruitment to protrusions is supported by endogenous integrin α5. (A–D) Validation of ITGA5 CRISPR-Cas9 KO U2OS cells. (A) Western blot analysis of WT and ITGA5 KO single cell clones showing the efficiency of the CRISPR-Cas9 ITGA5 KO in U2OS cells. (B) Genome sequence alignment of U2OS WT and ITGA5 KO clones with the ITGA5 WT sequence. The targeted exon and the gRNA used for CRISPR KO positions are indicated. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of cell surface integrin α5 in U2OS WT and ITGA5 KO clones. (D) Images of WT and ITGA5 KO U2OS clones stained for active integrin α5 (SNAKA51) and paxillin. Scale bar: 20 µm. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface RUSH-α5 levels (detected with the anti-GFP-AF647 antibody) in WT and ITGA5 KO U2OS cells transfected with RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Representative histograms and quantification of cell surface GFP (ratio of the geometric means of the surface signal divided by the total GFP signal, normalized by subtracting the 0 min value) are shown. Data are mean ± SD; N = 3 independent experiments. The two-tailed paired t test showed no significant differences between WT and ITGA5 KO. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface RUSH-α5 levels in adherent versus suspension U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Representative histograms and quantification of cell surface GFP analyzed as in E are shown. Data are mean ± SD; N = 3 independent experiments. The two-tailed paired t test, data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (G) Quantifications of RUSH-α5 intensity in ROIs (retracting or protruding areas) in WT and ITGA5 KO U2OS cells ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. One-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparison test, data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Data are mean ± SD; N = 59 WT cells, 53 ITGA5 KO cells, pooled from three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Early release of RUSH-α5 is adhesion dependent and polarized recruitment to protrusions is supported by endogenous integrin α5. (A–D) Validation of ITGA5 CRISPR-Cas9 KO U2OS cells. (A) Western blot analysis of WT and ITGA5 KO single cell clones showing the efficiency of the CRISPR-Cas9 ITGA5 KO in U2OS cells. (B) Genome sequence alignment of U2OS WT and ITGA5 KO clones with the ITGA5 WT sequence. The targeted exon and the gRNA used for CRISPR KO positions are indicated. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of cell surface integrin α5 in U2OS WT and ITGA5 KO clones. (D) Images of WT and ITGA5 KO U2OS clones stained for active integrin α5 (SNAKA51) and paxillin. Scale bar: 20 µm. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface RUSH-α5 levels (detected with the anti-GFP-AF647 antibody) in WT and ITGA5 KO U2OS cells transfected with RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Representative histograms and quantification of cell surface GFP (ratio of the geometric means of the surface signal divided by the total GFP signal, normalized by subtracting the 0 min value) are shown. Data are mean ± SD; N = 3 independent experiments. The two-tailed paired t test showed no significant differences between WT and ITGA5 KO. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface RUSH-α5 levels in adherent versus suspension U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Representative histograms and quantification of cell surface GFP analyzed as in E are shown. Data are mean ± SD; N = 3 independent experiments. The two-tailed paired t test, data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. (G) Quantifications of RUSH-α5 intensity in ROIs (retracting or protruding areas) in WT and ITGA5 KO U2OS cells ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. One-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparison test, data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Data are mean ± SD; N = 59 WT cells, 53 ITGA5 KO cells, pooled from three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Unconventional RUSH-α5 secretion is dependent on the integrin-tail PDZ-binding motif

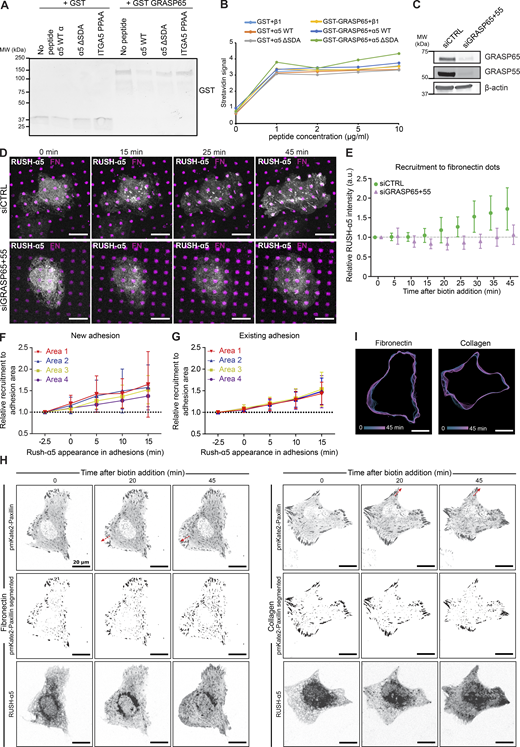

The two mammalian Golgi reassembly-stacking protein (GRASP) homologs, GRASP55 and GRASP65, mediate UPS of transmembrane proteins via PDZ domain-mediated interactions with cargo proteins (Gee et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2016). The integrin α5 cytoplasmic domain harbors two distinct PDZ-binding motifs: a classical C-terminal Ser-Asp-Ala (SDA) sequence (El Mourabit et al., 2002) and a non-canonical motif generated by two prolines (PP), which induce an internal β-hairpin that functions as a PDZ-recognition motif (Tuomi et al., 2009). To test whether integrin α5 associates with GRASPs, we performed GFP pulldowns in cells expressing RUSH-α5. In addition to integrin β1, we detected endogenous GRASP65 co-precipitating with RUSH-α5 (Fig. 5 C). Further pulldown experiments with biotinylated peptides corresponding to the C-terminal part of the integrin α5 WT tail or integrin α5 tails with mutations in the non-canonical PDZ-binding motif (PPAA peptide) or deletion of the canonical PDZ-binding motif (ΔSDA) (Fig. 5, D and E) indicated that GRASP65-integrin α5 association may require the SDA sequence (Fig. 5 E), in accordance with the ability of GRASP65 to facilitate UPS of ER-resident cargo containing PDZ-binding motifs and regulate N-linked glycosylation in the ER (Xiang et al., 2013). However, no direct interaction between recombinant GRASP65 and integrin α5 was observed by GST pulldown (Fig. S5 A) or ELISA (Fig. S5 B). This indicates that the association between integrin α5 and GRASP65 is indirect, requires additional co-factors or is sensitive to post-translational modifications.

Early release of RUSH-α5 is sensitive to GRASP silencing. (A) Immunoblot of GST pull-downs of recombinant integrin α5 WT or mutant (ΔSDA or PPAA) peptides incubated with GST alone or recombinant GST-GRASP65. No enrichment of GST-GRASP65 signal over background (no peptide beads) is detected with integrin α5 WT peptide, indicating that the integrin α5 peptides do not interact with recombinant purified GST-GRASP65. (B) ELISA assay detecting biotinylated recombinant integrin α5 WT or ΔSDA or PPAA mutant with HRP-streptavidin incubated on wells coated with GST alone or GST-GRASP65. No direct interaction between GRASP65 and integrin α5 WT peptide was detected. (C) Immunoblot of lysates collected from control-silenced or GRASP65 and GRASP55-silenced U2OS cells used in D, E, probed for GRASP65 and GRASP55. β-actin was probed as a loading control. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of control-silenced or GRASP65 and GRASP55-silenced U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 and plated on dual-coated micropatterns (magenta dots, FN; non-fluorescent regions, collagen peptide GFOGER). (E) Relative recruitment of RUSH-α5 in control- or GRASP65- and GRASP55-silenced U2OS cells to FN dots within the cell boundary. Data are mean ± SD; n = 9 siCTRL cells, 11 siGRASP cells (36 and 44 dots, respectively) from one experiment. (F and G) Quantification of RUSH-α5 intensity in the four areas relative to signal intensity in the respective area 2.5 min prior to RUSH-α5 appearance in (F) new adhesions or (G) already existing adhesions (determined from the time-lapse images) on FN- and anti-GFP antibody-coated surfaces. Adhesions close to the cell edge and with a minimum lifetime of 15 min were analyzed and changes of RUSH-α5 intensity were plotted over time in the indicated areas ranging from distal to proximal to the cell body. Data are mean ± SD; One independent experiment 9 adhesions from 6 cells on 2 coverslips (F) and one independent experiment 9 adhesions from 5 cells on 2 coverslips (G). (H and I) Representative images (H) and (I) track maps related to Fig. 6 I. Red arrows indicate direction of adhesion growth. Scale bars: 20 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS5.

Early release of RUSH-α5 is sensitive to GRASP silencing. (A) Immunoblot of GST pull-downs of recombinant integrin α5 WT or mutant (ΔSDA or PPAA) peptides incubated with GST alone or recombinant GST-GRASP65. No enrichment of GST-GRASP65 signal over background (no peptide beads) is detected with integrin α5 WT peptide, indicating that the integrin α5 peptides do not interact with recombinant purified GST-GRASP65. (B) ELISA assay detecting biotinylated recombinant integrin α5 WT or ΔSDA or PPAA mutant with HRP-streptavidin incubated on wells coated with GST alone or GST-GRASP65. No direct interaction between GRASP65 and integrin α5 WT peptide was detected. (C) Immunoblot of lysates collected from control-silenced or GRASP65 and GRASP55-silenced U2OS cells used in D, E, probed for GRASP65 and GRASP55. β-actin was probed as a loading control. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of control-silenced or GRASP65 and GRASP55-silenced U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 and plated on dual-coated micropatterns (magenta dots, FN; non-fluorescent regions, collagen peptide GFOGER). (E) Relative recruitment of RUSH-α5 in control- or GRASP65- and GRASP55-silenced U2OS cells to FN dots within the cell boundary. Data are mean ± SD; n = 9 siCTRL cells, 11 siGRASP cells (36 and 44 dots, respectively) from one experiment. (F and G) Quantification of RUSH-α5 intensity in the four areas relative to signal intensity in the respective area 2.5 min prior to RUSH-α5 appearance in (F) new adhesions or (G) already existing adhesions (determined from the time-lapse images) on FN- and anti-GFP antibody-coated surfaces. Adhesions close to the cell edge and with a minimum lifetime of 15 min were analyzed and changes of RUSH-α5 intensity were plotted over time in the indicated areas ranging from distal to proximal to the cell body. Data are mean ± SD; One independent experiment 9 adhesions from 6 cells on 2 coverslips (F) and one independent experiment 9 adhesions from 5 cells on 2 coverslips (G). (H and I) Representative images (H) and (I) track maps related to Fig. 6 I. Red arrows indicate direction of adhesion growth. Scale bars: 20 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS5.

We then explored the involvement of GRASP and the integrin tail in the early delivery of RUSH-α5. siRNA-mediated silencing of GRASP65 and GRASP55 (Fig. S5 C) inhibited RUSH-α5 delivery to FN spots on dual-coated (FN and GFOGER) micropatterns at 10–15 min post biotin addition (Fig. S5, D and E). However, the recruitment of RUSH-α5 to FN dots remained low 25 min after release, possibly due to GRASP silencing interfering with Golgi function (Xiang and Wang, 2010). Furthermore, GRASP depletion has been shown to downregulate integrin α5β1 protein levels and could also affect the lifetime of our exogenous construct (Ahat et al., 2019). To overcome these complications, we generated a RUSH-α5 construct lacking the potential integrin α5 GRASP65-binding SDA sequence (RUSH-α5-ΔSDA) and performed time-lapse imaging. RUSH-α5-ΔSDA recruitment to adhesions was delayed compared to cells expressing full-length RUSH-α5 (25 versus 5 min) (Fig. 5 F). Even after 45 min, RUSH-α5-ΔSDA accumulation in adhesions was diminished, consistent with unconventional secretion accounting for a small part of the overall integrin biosynthetic delivery in cells.

New integrins are delivered to FAs to drive adhesion growth

The endo/exocytic traffic of cell surface integrins controls FA dynamics, size, and distribution in cells (Ezratty et al., 2009; Moreno-Layseca et al., 2021; Sahgal et al., 2019; Nader et al., 2016); however, the role of integrin secretion remains to be explored. CD59, along with several other cargo proteins, undergo anterograde post-Golgi traffic to secretion hotspots adjacent to but discrete from FAs (Fourriere et al., 2019). We employed dual color TIRF imaging of RUSH-α5 and pmKate2-Paxillin in cells plated on FN to determine whether this is also the case for integrins. SPI revealed that RUSH-α5 is recruited to FAs and in their vicinity. When initiating a new adhesion, RUSH-α5 was initially localized to the most distal area (Area 1) of FAs (closest to the cell periphery), after which it gradually accumulated along the growing adhesion towards the cell center (Fig. 6, A and B; and Fig. S5 F). However, in an existing and elongated FA, RUSH-α5 was equally localized all along the FA (Fig. 6 C and Fig. S5 G).

RUSH-α5 is delivered to the tip of adhesions and mediates adhesion growth. (A and B) Representative immunofluorescence image of U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 and pmKate2-Paxillin (white, colocalization) plated on FN (10 µg/ml) and anti-GFP (2.5 µg/ml; to trap cell surface RUSH-α5 at the point of delivery). Insets represent ROIs that are magnified. ROI2 is a FA demarcated into four equal areas for analysis and is further magnified in B. Scale bars 20 µm (whole cell image), 5 µm (ROI1), and 0.5 µm (ROI2 and B). (C) Representative image of an already established FA where RUSH-α5 delivery was quantified. Scale bar 0.5 µm. (D) Cartoon showing clutch model elements. Myosin motors pull on actin filaments with a speed v. This applies force to a substrate via integrins and adapter proteins (talin). The effect of force regulates the unbinding rates from integrins to the substrate (koff) and the folding/unfolding rates of talin (kfold/kunfold). When talin unfolds, adhesion reinforcement is assumed to happen, which is modeled by an increase in integrin density with value dadd. Changes in integrin availability are modeled by changing the parameter dadd. (E) Model prediction of adhesion growth with time for conditions in which integrin availability is low (dadd = 0.005 integrins/μm2) or high (dadd = 0.01 integrins/μm2). Adhesion growth (y-axis) is modeled through integrin density, which is plotted normalized to the starting value. (F) Quantification of adhesion growth in U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 and plated on FN or collagen ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Shown are the relative sums of segmented adhesion area/cell. Data are mean ± SD. (G) Quantification of adhesion growth in WT and ITGA5 KO U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Shown are the relative sums of segmented adhesion area/cell. Data are mean ± SD. (H) Quantification of cell spreading in WT and ITGA5 KO cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Data are mean ± SEM. (I) Quantification of the length of the longest protrusion (extending furthest from the initial plasma membrane localization during imaging) formed per cell after 45 min of biotin. Data are mean ± SEM. (J) Schematic depiction of the regulation of cell dynamics by transport of integrins through the biosynthetic pathway. Adhesion and cell spreading-dependent delivery of integrin from the ER is detected rapidly after release in cell protrusions. Canonical Golgi-dependent delivery is also polarized to cell protruding areas in an ECM-specific manner and contributes to FA growth and cell protrusion. (F–H) One-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparison test, data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. (F)N = 64 cells on collagen, 50 cells on FN, pooled from three independent experiments. (G) 57 WT cells and 52 ITGA5 KO cells, (H) 59 WT cells and 55 ITGA5 KO cells, pooled from three independent experiments. (I) Mann–Whitney test, N = 55 cells on FN, 66 cells on collagen, pooled from three independent experiments.

RUSH-α5 is delivered to the tip of adhesions and mediates adhesion growth. (A and B) Representative immunofluorescence image of U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 and pmKate2-Paxillin (white, colocalization) plated on FN (10 µg/ml) and anti-GFP (2.5 µg/ml; to trap cell surface RUSH-α5 at the point of delivery). Insets represent ROIs that are magnified. ROI2 is a FA demarcated into four equal areas for analysis and is further magnified in B. Scale bars 20 µm (whole cell image), 5 µm (ROI1), and 0.5 µm (ROI2 and B). (C) Representative image of an already established FA where RUSH-α5 delivery was quantified. Scale bar 0.5 µm. (D) Cartoon showing clutch model elements. Myosin motors pull on actin filaments with a speed v. This applies force to a substrate via integrins and adapter proteins (talin). The effect of force regulates the unbinding rates from integrins to the substrate (koff) and the folding/unfolding rates of talin (kfold/kunfold). When talin unfolds, adhesion reinforcement is assumed to happen, which is modeled by an increase in integrin density with value dadd. Changes in integrin availability are modeled by changing the parameter dadd. (E) Model prediction of adhesion growth with time for conditions in which integrin availability is low (dadd = 0.005 integrins/μm2) or high (dadd = 0.01 integrins/μm2). Adhesion growth (y-axis) is modeled through integrin density, which is plotted normalized to the starting value. (F) Quantification of adhesion growth in U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 and plated on FN or collagen ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Shown are the relative sums of segmented adhesion area/cell. Data are mean ± SD. (G) Quantification of adhesion growth in WT and ITGA5 KO U2OS cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Shown are the relative sums of segmented adhesion area/cell. Data are mean ± SD. (H) Quantification of cell spreading in WT and ITGA5 KO cells expressing RUSH-α5 ± biotin treatment for the indicated times. Data are mean ± SEM. (I) Quantification of the length of the longest protrusion (extending furthest from the initial plasma membrane localization during imaging) formed per cell after 45 min of biotin. Data are mean ± SEM. (J) Schematic depiction of the regulation of cell dynamics by transport of integrins through the biosynthetic pathway. Adhesion and cell spreading-dependent delivery of integrin from the ER is detected rapidly after release in cell protrusions. Canonical Golgi-dependent delivery is also polarized to cell protruding areas in an ECM-specific manner and contributes to FA growth and cell protrusion. (F–H) One-way ANOVA, Holm-Šídák’s multiple comparison test, data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. (F)N = 64 cells on collagen, 50 cells on FN, pooled from three independent experiments. (G) 57 WT cells and 52 ITGA5 KO cells, (H) 59 WT cells and 55 ITGA5 KO cells, pooled from three independent experiments. (I) Mann–Whitney test, N = 55 cells on FN, 66 cells on collagen, pooled from three independent experiments.

To consider the effects of increased integrin delivery on adhesions, we employed a molecular clutch model previously developed to simulate mechanosensitive growth of adhesions (Elosegui-Artola et al., 2016). In this model, talin-mediated mechanosensing (through force-induced unfolding) leads to adhesion growth, modeled as an increase in integrin density (Fig. 6 D). To understand the effect of integrin delivery, we reasoned that an increased delivery would result in a higher availability of integrins to be incorporated into adhesions. Thus, we modeled integrin delivery by tuning the parameter that sets the increase in integrin density that occurs upon talin unfolding (dadd). Running the model with a base set of parameters taken from previous work (Table S1), modifying only the dadd parameter, and running the simulation as a function of time, indicated that delivery of new receptors is predicted to increase adhesion growth (Fig. 6 E). In concordance with the model, release of RUSH-α5 significantly increased adhesion area on FN, with no significant effect on collagen (Fig. 6 F). Adhesion growth supported by RUSH-α5 release was also apparent in the ITGA5 KO cells (Fig. 6 G), indicating that an increased number of clutches translates to larger adhesions also when a new type of integrin heterodimer is introduced to the cell surface. The increase in adhesion size correlated with enhanced cell spreading in WT and ITGA5 KO cells transfected with RUSH-α5 (Fig. 6 H) and to increased cell dynamics with longer cell protrusions extended in cells plated on FN compared to collagen following biotin addition (Fig. 6 I; and Fig. S5, H and I). Taken together, these data indicate that newly synthesized integrin α5 is rapidly localized to FAs, contributing to adhesion growth towards the proximal end and facilitating cell protrusion in a spatially defined and ligand-dependent manner.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that cell adhesion and polarized cell dynamics can be steered by targeted delivery of newly synthesized integrins to the plasma membrane, and that this can occur rapidly, in a localized manner, bypassing the Golgi complex (Fig. 6 J). The biosynthetic trafficking route of integrins has not been previously investigated spatiotemporally in cells or associated with dynamic regulation of cell morphology and integrin adhesions. Earlier biochemical labeling studies analyzed synthesis, folding and secretion of integrins but were not amendable for imaging of their delivery to the plasma membrane. Therefore, the contribution of newly synthesized integrin to cell dynamics has remained uninvestigated. Our findings place integrin delivery via the biosynthetic pathway on par with well-established pathways that control integrin dynamics on the plasma membrane, namely endocytosis and recycling.

Motor-clutch-based modeling has been employed to understand many fundamental aspects of cell dynamics in response to ECM ligands and matrix rigidity (Elosegui-Artola et al., 2016; Isomursu et al., 2022; Kechagia et al., 2019). Here, the model predicted time-dependent growth of adhesions in response to delivery of an increased number of integrins. These matched with our experimental data revealing increased adhesion growth and generation of cell protrusions in response to RUSH-α5 release from the ER. These data further underline that biosynthetic delivery of integrins is an important and thus far underestimated contributor to cell responses to ECM mechanics and composition.

Many open questions remain regarding the biological significance of integrin delivery via the biosynthetic route and the mechanisms governing this process. We find that GRASP65 is required for the rapid unconventional secretion of RUSH-α5. However, its full contribution to the spatial and temporal regulation of integrin unconventional secretion requires further investigation. The GRASP proteins are localized to the Golgi and are classically associated with Golgi stacking. However, they are also involved in stress-induced UPS (Giuliani et al., 2011). Our data imply that integrin UPS is adhesion-dependent and seems to be always linked with cell spreading. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that local mechanical stress could be a signal for one pool of integrins to rapidly exit the ER and be delivered to the proximal plasma membrane. However, this remains to be investigated. While proteins can undergo N-glycosylation in the ER (Xiang et al., 2013), it is plausible that the glycans of the early secreted pool of integrins are not fully processed but rather remain in an immature, high-mannose state. N-glycan chains support integrin headpiece opening (activation) and increase integrin-ligand binding affinity (Li et al., 2017). However, high-mannose integrins are also functional in ECM engagement (Li et al., 2017), consistent with the early delivery of RUSH-α5 supporting cell protrusions and adhesion growth. The presence of high-mannose glycosylated integrins at the cell surface has been so far only demonstrated in cancer cells (Oh et al., 2022; Park et al., 2020). Moreover, we showed integrin delivery via unconventional secretion only in a cancer cell line model. Whether this is also relevant to normal cells or is specific to cancer cells remains to be determined.

Our data indicate that cells sense their underlying ECM and have the ability to deliver new integrins in a polarized manner in response to receptor-specific ECM ligands. This is an exciting observation that might be particularly relevant in the context of development, tissue patterning and in wound healing where directed cell migration is paramount (Kanchanawong and Calderwood, 2022). Thus far, we have explored this process and its regulation in the context of the FN-binding integrin α5β1. Existing data suggest that for all β1-integrins the β1-subunit is produced in excess and localizes to the ER where it homodimerizes with an α-subunit to become transported to the plasma membrane (Heino et al., 1989). Integrin α-subunits harbor distinct cytoplasmic domains, and only a subset have a putative GRASP PDZ-binding motif (De Franceschi et al., 2016). In the future it will be interesting to explore whether integrin UPS is applicable only to a subset of integrins and whether these are perhaps biologically differentially employed in processes requiring a rapid and dynamic cell response.