Mitophagy transports mitochondria to lysosomes for degradation to maintain energy homeostasis, inflammation, and immunity. Here, we identify CipB, a type III secretion system (T3SS) effector from Chromobacterium violaceum, as a novel exogenous mitophagy receptor. CipB targets mitochondria by the mitochondrial protein TUFM and recruits autophagosomes via its LC3-interacting region (LIR) motifs. This process initiates the mitophagy-TFEB axis, triggering TFEB nuclear translocation and suppression of proinflammatory cytokines, thereby promoting bacterial survival and pathogenesis. CipB represents a conserved family of T3SS effectors employed by diverse pathogens to manipulate host mitophagy. Using a mouse model, CipB’s mitophagy receptor function is critical for C. violaceum colonization in the liver and spleen, underscoring its role in bacterial virulence. This study reveals a novel mechanism by which bacterial pathogens exploit host mitophagy to suppress immune responses, defining CipB as a paradigm for exogenous mitophagy receptors. These findings advance our understanding of pathogen–host interactions and highlight the mitophagy-TFEB axis as a potential signaling pathway against bacterial infection.

Introduction

Mitophagy is a catabolic pathway that selectively delivers mitochondria to lysosome for degradation (Galluzzi and Green 2019; Wang et al., 2023a). Receptor-mediated mitophagy appears to play a pivotal role in cellular development and specialization (Palikaras et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2023b). In the PINK1–Parkin pathway, mitochondrial depolarization activates PINK1, which recruits both ubiquitin and the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin to the mitochondria, resulting in the tagging of mitochondria with ubiquitin (Lin et al., 2020; Vargas et al., 2023). Ubiquitin-tagged mitochondria are then recognized by general autophagy receptors, linking the ubiquitinated mitochondria to the autophagy machinery (Mizushima 2024; Wang et al., 2023b). In receptor-mediated mitophagy, at least eight mitochondria-resident proteins have been identified to function as endogenous mitophagy receptors, including FUNDC1, BNIP3, NIX, PHB2, ATAD3B, FKBP8, NLRX1, and BCL2L13 (Bhujabal et al., 2017; Hanna et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012; Murakawa et al., 2015; Novak et al., 2010; Shu et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). Mitophagy receptors lack an ubiquitin-binding domain but contain LC3-interacting region (LIR), which facilitates binding to autophagy-related protein 8 (ATG8s) on the autophagic membrane (Onishi et al., 2021; Palikaras et al., 2018). The mature mitophagosome then fuses with lysosomes for degradation. Under stress conditions, such as CCCP treatment, oxidative stress, and bacterial infection, mitophagy plays a critical role in energy homeostasis, inflammation, and innate immunity (Ma et al., 2024; Marchi et al., 2023).

Emerging evidence suggests an intricate cross talk between autophagy and the transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy. TFEB orchestrates cellular clearance processes by transcriptionally activating genes involved in autophagosome formation (e.g., LC3 and p62) and lysosomal function (Zhang et al., 2020). Under basal conditions, TFEB is phosphorylated by mTORC1 and retained in the cytoplasm (Goul et al., 2023). Notably, several studies have revealed that PINK1–Parkin-mediated mitophagy activation can modulate TFEB (Nezich et al., 2015).

In the coevolutionary history between hosts and pathogens, bacterial pathogens have evolved specialized protein secretion systems, such as type III secretion systems (T3SSs), to deliver virulent effector proteins into host cells. T3SS effectors target host signaling pathways to benefit bacterial infection. For instance, T3SS effector YopH from Yersinia pestis and toxin listeriolysin O from Listeria monocytogenes have been reported to indirectly activate mitophagy by disrupting mitochondrial membrane potential (Jiao et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019). Additionally, the T3SS translocase/translocon protein SipB from Salmonella has been observed on mitochondria during infection (Hernandez et al., 2003). General autophagy or pathogen-specific xenophagy are considered as a part of innate immunity to protect host (Ge et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2019), whereas some studies indicate that activation of mitophagy is beneficial for pathogens to promote infection (Nan et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2019). However, its function and mechanism remain largely unknown.

In this study, we reveal that the bacterial T3SS effector CipB family functions as a novel exogenous mitophagy receptor, orchestrating the activation of the mitophagy-TFEB axis to suppress host immune responses and promote bacterial infection. Specifically, CipB targets mitochondria through direct interaction with the mitochondrial protein TUFM, utilizes its intrinsic LIR motifs to selectively engage LC3 family members, and recruits ubiquitin to mitochondria, thereby initiating mitophagy. This process triggers the nuclear translocation of TFEB. Our findings not only elucidate a unique mechanism by which bacterial pathogens exploit host mitophagy to evade immunity but also identify CipB as the first known bacterial effector capable of functioning as a mitophagy receptor. This study provides a paradigm for understanding how bacterial pathogens counteract host defenses and highlights the potential of targeting the mitophagy-TFEB axis as a therapeutic strategy against bacterial infections.

Results

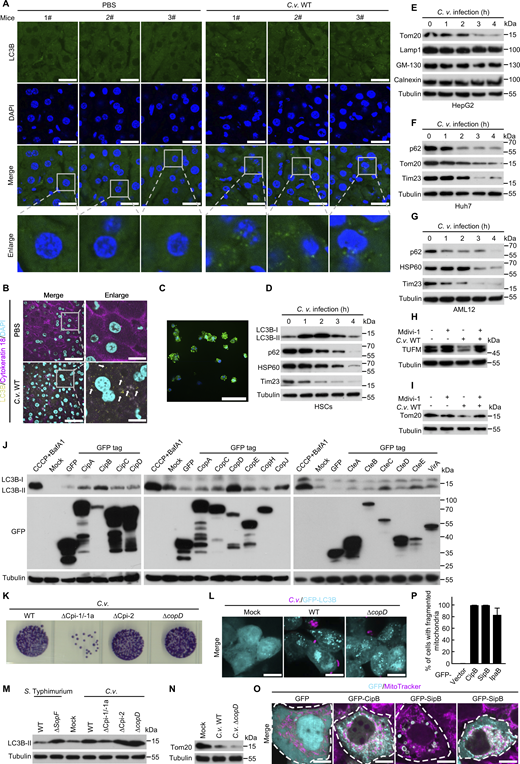

Chromobacterium violaceum infection induces mitophagy in vivo and in vitro

C. violaceum is a highly virulent, intracellular Gram-negative bacterium with a mortality rate exceeding 50% in humans (Batista and da Silva Neto 2017; Maltez et al., 2015). Its pathogenicity is largely mediated by two T3SSs, namely Chromobacterium pathogenicity island-1/-1a (Cpi-1/-1a) and Chromobacterium pathogenicity island-2 (Cpi-2) (Betts et al., 2004). To investigate the impact of C. violaceum infection on autophagy, we analyzed LC3B lipidation, p62 degradation, and mitochondrial protein turnover. Intraperitoneal infection of C57BL/6N mice led to hepatic LC3B lipidation (Fig. 1 A), accumulation of LC3B puncta in hepatocytes (Fig. 1, B and C; and Fig. S1, A and B), and a significant reduction in the mitochondrial protein Tom20 (Fig. 1 D), collectively indicating robust induction of mitophagy in vivo.

In vitro infection of epithelial cells recapitulated these findings: C. violaceum triggered LC3B activation (Fig. 1, E–I) and promoted p62 degradation (Fig. 1, J and K), confirming autophagic flux.

Further evidence of mitophagy was provided by the mitochondrial localization of lipidated LC3B upon infection (Fig. 1 L) and the use of a pH-sensitive tandem reporter construct, pmRFP-GFP-Mito (Wang et al., 2021). Infection resulted in the loss of acid-labile GFP fluorescence while retaining RFP signal, confirming lysosome fusion of mitophagosome (Fig. 1, M and N). Notably, C. violaceum infection triggered extensive mitochondrial protein degradation in diverse hepatic cell types, including primary liver cells (Kupffer cells [KCs] and hepatic stellate cells [HSCs]), hepatocarcinoma cell lines (HepG2 and Huh7), mouse AML12 hepatocytes, and epithelial cells (293T) (Fig. S1, C–G and Fig. 1, O–R). The observed reduction in mitochondrial markers (e.g., Tom20, Tim23, and HSP60), coupled with enhanced LC3B lipidation, indicates that C. violaceum–induced mitophagy is evolutionarily conserved across hepatic cell lineages.

The requirement for autophagy machinery was demonstrated in ATG5+/+ and ATG5−/− MEFs. Mitochondrial protein degradation occurred exclusively in ATG5+/+ cells (Fig. 1, S and T). Furthermore, treatment with the mitophagy inhibitor Mdivi-1 prevented mitochondrial protein loss (Fig. S1, H and I), confirming the induction of mitophagy. Together, these findings establish that C. violaceum infection induces ATG5-dependent mitophagy both in vivo and in vitro.

Bacterial T3SS effector CipB family triggers mitophagy

To identify the bacterial factor driving mitophagy, we analyzed C. violaceum mutants lacking the T3SS machinery. Deletion of Cpi-1/-1a, but not Cpi-2, abolished LC3B puncta formation and lipidation, as well as Tom20 degradation (Fig. 2, A–D), implicating Cpi-1/-1a effectors involving in mitophagy induction. Among 16 predicted effectors, ectopic expression of CipB, a translocon component (Fig. 2 E) and secreted effector of the T3SS injectisome (Kubori et al., 1998; Marlovits et al., 2004; Miki et al., 2011), recapitulated mitophagy phenotypes (Figs. 2 and S1): LC3B lipidation (Fig. 2 F), LC3B puncta formation (Fig. 2, G and H), and p62 degradation (Fig. 2, I and J). Ectopic expression of CopD was also found to cause LC3B lipidation (Fig. S1 J). However, deletion of copD remained to induce LC3B activation and Tom20 degradation during infection (Fig. S1, K–N).

CipB shares 62% and 36% sequence identity with its homologs SipB (from Salmonella typhimurium) and IpaB (from Shigella flexneri), respectively, both of which are Gram-negative pathogens and leading causes of bacterial diarrhea worldwide. Consistent with its role in mitophagy, ectopic expression of CipB family proteins, including SipB and IpaB, induced the accumulation of LC3B puncta (Fig. 2, K and L) and triggered mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig. 2, M and N; and Fig. S1, O and P). Immunofluorescence analysis further confirmed that GFP-LC3B colocalized with mitochondria in cells expressing RFP-CipB (Fig. 2, O and P). Mechanistically, CipB expression induced the reduction of mitochondrial proteins (Fig. 2, Q and R), while ATG5 knockout completely abrogated this effect (Fig. 2 S), establishing the ATG5-dependence of the process. Notably, this mitophagy-inducing capacity was conserved across the CipB family, as evidenced by Tom20 degradation upon expression of other family members (Fig. 2, T and U). These collective findings position the CipB effector family as evolutionarily conserved trigger of host mitophagy.

CipB localizes to mitochondria through TUFM

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying CipB-induced mitophagy, we first examined whether CipB operates through the canonical PINK1–Parkin pathway. Parkin is selectively recruited to depolarized mitochondria during PINK1–Parkin-mediated mitophagy (Narendra and Youle 2024; Xiao et al., 2022). However, CipB did not induce mitochondrial depolarization or Parkin recruitment (Fig. S2, A–D), indicating that CipB-triggered mitophagy is independent of the PINK1–Parkin pathway.

We next investigated whether CipB interacts with mitochondria-related proteins, including known mitophagy receptors (PHB2, BCL2-L13, NIX, BNIP3, and FUNDC1) and other mitochondrial-localized proteins (TUFM, HSP60, ATP5A, Tim23, and Smac). While CipB did not associate with any reported mitophagy receptors, it specifically bound to TUFM (Fig. 3, A and B). This interaction was conserved across the CipB family, as endogenous TUFM also bound to homologs SipB and IpaB (Fig. 3 C). Furthermore, GST pull-down assays confirmed a direct interaction between purified CipB and TUFM (Fig. 3 D), establishing TUFM as a key mitochondrial partner for CipB. TUFM is reported to localize to both the cytosol and mitochondria (Tian et al., 2022). To determine whether CipB and TUFM interact within the mitochondria or the cytosol, we overexpressed CipB in 293T cells and performed subcellular fractionation followed by immunoprecipitation. The results revealed that the majority of both TUFM and CipB localize to mitochondria, where they physically interact (Fig. 3, E and F).

To further define CipB’s submitochondrial localization, we overexpressed Flag-CipB or Flag-CipB-HA and treated purified mitochondria with proteinase K, which cleaves proteins exposed on the outer mitochondrial membrane. Both Flag-CipB and Flag-CipB-HA retained their ability to induce mitophagy, confirming that neither the N-terminal Flag tag nor the C-terminal HA tag interfered with CipB function (Fig. 3 G). Proteinase K treatment revealed that mitochondrial intermembrane space (Tim23) and matrix (HSP60) proteins were protected, confirming mitochondrial membrane integrity during CipB expression (Fig. 3 H). In contrast, the N-terminal Flag and C-terminal HA tags of CipB were susceptible to proteinase K digestion, similar to the outer membrane protein Tom20, indicating that both termini of CipB are exposed on the mitochondrial outer membrane (Fig. 3, H and I). Combined with the observation that both CipB (1–414) and CipB (317–424) interact with TUFM (Fig. S2, E–H), we propose a model in which CipB inserts into the mitochondrial through its two transmembrane domains, leaving its N- and C-terminal regions exposed to the cytosol (Fig. 3 J).

Given that TUFM localizes to mitochondria (Fig. 3, F and K), we investigated whether TUFM mediates the mitochondrial recruitment of CipB. To test this, we knocked down Tufm using siRNA, with knockdown efficiency confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (Fig. 3 L). TUFM depletion significantly reduced CipB levels in the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 3 M), demonstrating that TUFM is required for CipB’s mitochondrial localization. To determine whether TUFM is essential for CipB-induced mitophagy, we examined Tom20 degradation in 293T cells expressing RFP-CipB. Tufm knockdown inhibited the reduction of Tom20 (Fig. 3, N and O), suggesting that TUFM is critical for mitophagy induction. To further validate these findings, we generated a heterozygous Tufm knockout (TUFM+/−) cell line (Fig. 3 P). Consistent with the knockdown results, mitophagy was impaired in TUFM+/− cells upon CipB expression (Fig. 3 Q). Together, these results demonstrate that TUFM is essential for recruiting CipB to mitochondria and facilitating CipB-induced mitophagy.

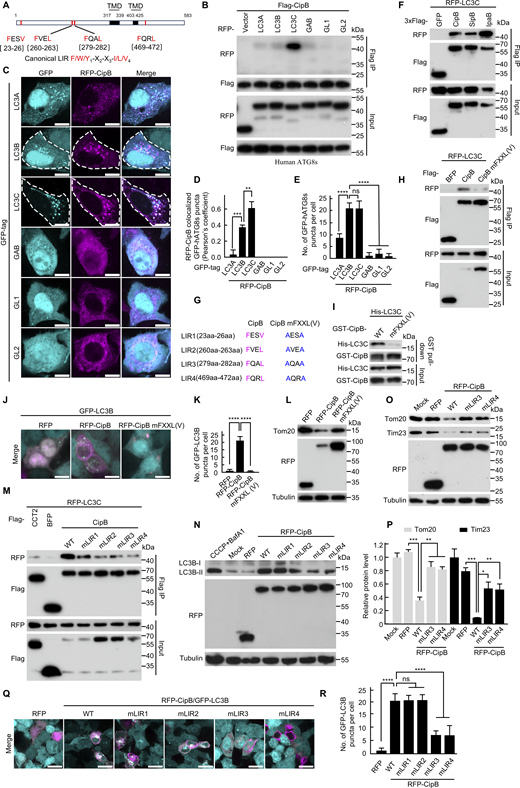

CipB binds to LC3 via classical LIR motif to promote mitophagy

To investigate how CipB engages the autophagic machinery, we analyzed its protein sequence using the iLIR web server (Kalvari et al., 2014), which predicted the presence of four LIR motifs (Fig. 4 A). We then examined CipB’s interaction with human ATG8 family members, including LC3A, LC3B, LC3C, GABARAP, GABARAP-L1, and GABARAP-L2 (Ma et al., 2022; Martens and Fracchiolla 2020). Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays revealed that CipB exhibiting the strongest interaction with LC3C among the six ATG8 paralogues (Fig. 4 B). Confocal microscopy confirmed the colocalization of RFP-CipB with GFP-LC3C and GFP-LC3B, but not with other ATG8 family members (Fig. 4, C and D). Furthermore, ectopic expression of CipB increased the puncta formation of GFP-LC3C and GFP-LC3B (Fig. 4, C and E), indicating enhanced autophagic flow. As homologs SipB and IpaB also bound LC3C, this interaction was conserved across the CipB family (Fig. 4 F).

To validate the functional importance of the LIR motifs, we generated a CipB mutant with all four LIR motifs mutated, CipB mFXXL(V). This mutant exhibited significantly reduced binding affinity to LC3C in both Co-IP and GST pull-down assays (Fig. 4, G–I), confirming that CipB interacts directly with LC3C through its LIR motifs. Notably, the CipB mFXXL(V) mutant failed to induce GFP-LC3B puncta formation (Fig. 4, J and K) and Tom20 degradation (Fig. 4 L), underscoring the critical role of LIR motifs in CipB-induced mitophagy. By individually mutating each LIR motif, we identified LIR3&4 as the key functional motifs. Mutations in LIR3&4 significantly reduced CipB’s interaction with LC3C (Fig. 4 M) and abolished mitophagy induction (Fig. 4, N–R). Collectively, these results reveal that CipB binds LC3 through its LIR motifs to initiate mitophagy, highlighting a novel mechanism by which a bacterial effector activates the host autophagic machinery.

The CipB family functions as an exogenous mitophagy receptor recruiting LC3 and ubiquitin to mitochondria

To further investigate how mitochondria are specifically recognized during C. violaceum–induced mitophagy, we observed that endogenous ubiquitin accumulated around mitochondria (Fig. 5, A and B). In ubiquitin-mediated mitophagy, ubiquitin serves as a degradation signal, marking mitochondria for encapsulation by autophagosomes and subsequent lysosomal degradation (Mizushima 2024). Ectopically expressed CipB family proteins were also found to be ubiquitylated (Fig. 5 C). To determine the specific types of poly-ubiquitin chains formed on CipB, we co-transfected CipB with WT ubiquitin, ubiquitin lacking all lysines (KO), or ubiquitin mutants retaining a single lysine residue (K6O, K11O, K27O, K29O, K33O, K48O, and K63O) or retaining all but one lysine residue (KR), followed by denature-IP. This analysis revealed that K27-linked ubiquitin chains were the predominant form on CipB (Fig. S3, A and B). Consistent with this finding, WT and K27O ubiquitin, but not KO ubiquitin, colocalized with CipB (Fig. S3, C and D), further supporting the specificity of K27-linked ubiquitination.

To identify further potential ubiquitination sites, we performed immunofluorescence analysis and found that the CipB (1–424) truncation colocalized with ubiquitin (Fig. 5 D), suggesting ubiquitination sites reside within the N-terminal 1–424 aa region. Since ubiquitination typically occurs through covalent attachment to specific lysine residues (Damgaard 2021; Liu et al., 2021), we performed sequence alignment of CipB with homologous proteins (SipB and IpaB), revealing conserved lysine residues within the CipB family proteins in the 1–424 aa region. Systematic mutagenesis identified Lys218 as the key lysine residue for CipB ubiquitination (Fig. 5 E and Fig. S3 E). Functional analysis showed that the K218R mutation significantly inhibited mitophagy activity compared with WT CipB (Fig. 5, F and G), establishing ubiquitination at Lys218 as essential for CipB-mediated mitophagy.

We further discovered that CipB promotes ubiquitin-mitochondria colocalization (Fig. 5 H), indicating its role in recruiting ubiquitin to mitochondria. To determine whether this process depends on CipB ubiquitination, we performed subcellular fractionation analysis in 293T cells expressing either RFP, RFP-CipB, or ubiquitination-deficient mutant RFP-CipB (K218R). Immunoblot analysis revealed that WT CipB significantly enhanced ubiquitin levels in the mitochondrial fraction, whereas the K218R mutant completely inhibited this effect (Fig. 5 I). These data suggest that ubiquitination of CipB facilitate ubiquitin accumulation on mitochondria. Consistent with CCCP-induced mitophagy mechanisms, where ubiquitinated mitochondrial proteins recruit p62 to initiate autophagy, we observed significant mitochondria-p62 colocalization in CipB-expressing cells (Fig. S3 F). These findings suggest that ubiquitination of CipB may facilitate the recruitment of autophagy adaptor proteins, including p62, to promote mitophagic flux.

Similarly, CipB family proteins were observed to recruit LC3 and ubiquitin to mitochondria (Fig. 5 J). These findings demonstrate that CipB functions as an exogenous mitophagy receptor, bridging ubiquitin-CipB-mitochondria to LC3-labeled autophagosomes to facilitate mitophagy.

CipB activates the mitophagy-TFEB axis to suppress immune responses

Some studies have reported that mitophagy inhibits immune responses by reducing the production of inflammatory factors (Luo et al., 2023; Oh et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024). To investigate whether CipB-induced mitophagy modulates immune signaling, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on 293T cells transfected with either CipB or a CipB LIR mutant. The RNA-seq results revealed that CipB-induced mitophagy upregulated immunosuppressive genes, including FOS, FOSB, FOS-like 1, and ETV1. Furthermore, CipB expression downregulated several immune-related genes, such as cytokines (IL17F, IL5, IL16, and IL31RA), the inflammasome component NLRC4, and the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 (Fig. 6, A and B). These findings suggest that CipB-induced mitophagy suppresses the host immune response, potentially facilitating bacterial immune evasion.

Transcription factors are known to regulate the production of inflammatory factors (Guo et al., 2024; Visvikis et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2024). We hypothesized that CipB-induced mitophagy might activate a transcription factor to mediate immune suppression. We observed that C. violaceum infection induces a downward shift of TFEB on SDS-PAGE, accompanied by the nuclear translocation of cytosolic TFEB protein (Fig. 6, C and D), indicating TFEB activation. Moreover, TFEB activation phenomenon was conserved across multiple hepatic cell models, including: KCs (Fig. S4 A), HSCs (Fig. S4 B), HepG2 (Fig. S4 C), Huh7 (Fig. S4 D), and AML12 mouse hepatocytes (Fig. S4 E). Expression of CipB alone also resulted in TFEB dephosphorylation (Fig. 6 E) and nuclear translocation (Fig. 6, F and G), demonstrating that CipB activates TFEB.

Given that PINK1–Parkin-mediated mitophagy has been reported to regulate TFEB translocation (Nezich et al., 2015), we investigated whether CipB-induced mitophagy similarly contributes to TFEB activation. Using RavZ, an LC3 lipidation inhibitor derived from Legionella pneumophila (Choy et al., 2012; Horenkamp et al., 2015; Kubori et al., 2017), we found that co-expression of RavZ inhibited CipB-triggered TFEB nuclear translocation (Fig. 6, H–J). Furthermore, the mitophagy-deficient CipB mFXXL(V) mutant failed to induce TFEB nuclear translocation (Fig. 6, K and L). These results indicate that CipB-induced mitophagy is upstream of TFEB activation, establishing a mitophagy-TFEB axis.

To determine whether TFEB mediates the immune-suppressive effects of CipB-induced mitophagy, we compared the transcriptional levels of immune-related genes in WT and TFEB-knockout (TFEB−/−) cells upon CipB expression. The downregulation of immune-related genes, including IL17F, IL5, IL16, IL31RA, NLRC4, and CX3CR1, was abolished in TFEB−/− cells (Fig. 6, M and N). Similarly, the mitophagy induction–deficient mutant, CipB mFXXL(V), failed to downregulate these immune genes (Fig. 6, B and O), and its effect was comparable with that of TFEB knockout (Fig. 6 O). These data show that TFEB activation is the primary mechanism by which CipB-induced mitophagy regulates immune responses. Collectively, these results reveal that CipB functions as an exogenous mitophagy receptor, activating the mitophagy-TFEB axis to suppress host immune responses.

The mitophagy receptor function of CipB is essential for C. violaceum–induced mitophagy and pathogenesis during animal infection

To elucidate the role of CipB in C. violaceum–induced mitophagy, we generated a C. violaceum mutant strain lacking the cipB gene. Since CipB is a component of the translocon in the T3SS injectisome machinery, the ΔcipB strain exhibited a loss of invasion ability (Fig. S5, A and B). Additionally, the ΔcipB strain failed to induce LC3B activation, p62 degradation, or Tom20 degradation (Fig. S5, C–E). These defects were fully restored by complementation with WT CipB (Fig. S5, C–E), confirming that CipB is essential for C. violaceum–induced mitophagy.

To investigate the necessity of the interaction between CipB and LC3C in C. violaceum–induced mitophagy in vivo, we complemented C. violaceum ΔcipB strain with various CipB mutants. Complementation with pCipB mLIR1&3&4 or pCipB mLIR3&4 restored invasion ability, whereas pCipB mFXXL(V) or pCipB mLIR2&3&4 did not (Fig. 7, A and B; Fig. S5 F). Unlike WT CipB, the CipB mLIR3&4 mutant cannot support LC3C lipidation (Fig. 7 C), indicating that the LIR motifs are critical for mitophagy induction during infection.

To assess the role of CipB in C. violaceum pathogenesis, we employed a mouse model of intraperitoneal infection. Although mice lack the LC3C gene (Tamargo-Gómez et al., 2021), we found that CipB interacts with five members of the mouse ATG8 family in Co-IP assays (Fig. 7 D), supporting the feasibility of using this model to study CipB-mediated mitophagy.

In vivo, the ΔcipB strain, which lacks invasion ability in vitro, displayed reduced mitophagy levels in the liver compared with the WT strain (Fig. S5, G–I). Consistent with this, the ΔcipB strain exhibited lower virulence, as evidenced by decreased bacterial burden in the liver and spleen and a lower mortality rate (Fig. S5, J–L). Importantly, complementation with WT CipB rescued all these phenotypes, confirming the critical role of CipB in pathogenesis.

CipB has dual roles during infection: (1) as a translocon component of the T3SS injectisome and (2) as a secreted effector functioning of mitophagy receptor. To dissect these roles, we used LIR mutants to specifically disrupt the mitophagy receptor function while preserving T3SS activity. Complementation of the ΔcipB strain with WT CipB or LIR mutants (CipB mLIR1&3&4 and CipB mLIR3&4) restored invasion ability and caused similar weight loss during acute infection (Fig. 7, A and B; and Fig. S5 M), demonstrating that the LIR mutants retain T3SS function. However, only WT CipB, but not the LIR mutants, restored LC3B lipidation, puncta formation (Fig. 7, E–G and Fig. S5 N), and Tom20 degradation in the liver (Fig. 7, H and I). Similarly, the LIR mutants failed to restore bacterial liver burden and mortality rates to levels observed with the WT strain or the WT CipB-complemented strain (Fig. 7, J–L). These results indicate that the direct interaction between CipB and LC3 is essential for mitophagy during C. violaceum infection in vivo. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that CipB-triggered mitophagy, mediated through the mitophagy-TFEB axis, promotes bacterial pathogenesis in the mouse model (Fig. 8).

Discussion

CipB: A bacterial pathogen–encoded exogenous mitophagy receptor

Autophagy is a conserved cellular degradation system found in eukaryotes, wherein cytoplasmic constituents are transported to lysosomes for degradation (Zhang et al., 2021). Selective autophagy relies on autophagy receptors, which recognize ubiquitinated cargo and recruit ATG8 family proteins to facilitate autophagosome formation (Turco et al., 2021). Here, we identify CipB, a C. violaceum T3SS effector, as the first exogenous mitophagy receptor from bacterial pathogen. Similar with endogenous receptors, CipB acts as a one-in-pot mechanism, bridging ubiquitin and ATG8 on mitochondria (Fig. 5, H and J). This discovery reveals a novel mechanism by which pathogens activate mitophagy machinery, expanding our understanding of host–pathogen interactions.

CipB’s dual roles: From T3SS translocon to mitophagy receptor

CipB exhibits dual functions. One is the translocon component of T3SS injectisome, critical for bacterial invasion. On the other hand, CipB is T3SS-secreted effector protein that localizes to mitochondrial and functions as an exogenous mitophagy receptor. While the LIR motifs of CipB are dispensable for its translocon function, they are essential for its role in mitophagy induction. This functional dichotomy underscores the evolutionary sophistication of bacterial effectors, which can simultaneously mediate invasion and manipulate host cellular processes.

A conserved mechanism for manipulating mitophagy-TFEB axis

CipB family proteins are widely distributed in a variety of bacteria, including CipB (C. violaceum), SipB (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium), IpaB (S. flexneri), BipB (Burkholderia pseudomallei), YopB (Yersinia pseudotuberculosis), AopB (Aeromonas hydrophila), and PopB (Pseudomonas aeruginosa). These proteins share a conserved role as T3SS translocons but also exhibit effector functions that modulate host pathways. Our findings reveal that LIR motifs, while dispensable for translocon activity, are critical for activating the mitophagy-TFEB axis. This axis not only promotes mitophagy but also suppresses host immune responses by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines, facilitating bacterial survival and proliferation.

General autophagy and mitophagy play opposite roles in counteracting pathogens

In the evolutionary “'arms race” between host and pathogens, certain pathogenic bacteria inhibit host autophagy for their survival. S. typhimurium inhibits host cell xenophagy by secreting the effector protein SopF, which promotes its survival in the liver and spleen (Xu et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2019). Mycobacterium tuberculosis secretes the effector protein PknG to block autophagic flow for its survival in macrophages (Ge et al., 2022). L. pneumophila inhibits host autophagy through cysteine protease RavZ for its survival (Mei et al., 2021). In contrast, the role of mitophagy in bacterial survival is distinct from that of autophagy. L. monocytogenes targets the mitochondrial receptor NLRX1 to induce mitophagy, promoting their intracellular survival (Zhang et al., 2019). Neisseria gonorrhoeae induces mitophagy in epithelial cells, which reduces the production of reactive oxygen species and enhances its intracellular survival (Gao et al., 2024). Consistently, C. violaceum–induced mitophagy facilitates its colonization in the liver and spleen and promotes bacterial survival. Compared with previous studies, we have identified C. violaceum suppresses the host immune response by activating mitophagy-TFEB axis. TFEB activation not only enhances autophagic flux but also downregulates proinflammatory cytokines, creating an immunosuppressive environment that benefits the pathogen. These findings not only advance our understanding of pathogen–host interactions but also highlight the potential of targeting mitophagy and TFEB as therapeutic strategies against bacterial infections. Future studies should explore whether other pathogens employ similar mechanisms to manipulate host autophagy and immune responses, opening new avenues for combating infectious diseases.

Materials and methods

Mice

WT C57BL/6N mice were from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Mice were bred and maintained at the specific pathogen-free facility in the Experimental Animal Center of Huazhong Agricultural University. Five-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were used for bacterial infection. All experimental protocols were carried out in accordance with the national guidelines for the housing and care of laboratory animals (Ministry of Health, China) and were approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University (HZAUMO-2023-0307).

Plasmid, antibodies, and reagents

DNA sequences encoding T3SS effectors were amplified from the genomic DNA of C. violaceum. While cDNAs for ATG8 family members, mitochondrial protein, Parkin, and ubiquitin were amplified from a 293T cell cDNA library. RavZ was amplified from L. pneumophila strain Lp01. Truncation, deletion, and point-mutation mutants were generated using standard PCR cloning techniques. These sequences were then inserted into various vectors, such as pCS2-EGFP, pCS2-RFP, pCS2-BFP, pCS2-HA, and pCS2-Flag vectors, for transient expression in mammalian cells; N-terminal His-tagged constructs were created using the plasmid pET28a, while C-terminal His-tagged constructs were generated using pET21b. GST-tagged constructs were prepared using the plasmid pGEX-6p-1. The plasmid pDM4 was utilized to generate a deletion mutant in C. violaceum, and the plasmid pBBR1MCS2 was used for protein expression in C. violaceum.

For immunofluorescence staining or western analysis, the following antibodies were used: Rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3B (western 1:1,000, cat #ab48394; Abcam), Rabbit monoclonal anti-LC3B (immunofluorescence 1:1,000, cat #ab192890; Abcam), Mouse monoclonal anti–α-Tubulin (western 1:5,000, cat #T5168; Sigma-Aldrich), Rabbit polyclonal anti-SQSTM1/p62 (western 1:5,000, cat #PM045; MBL), Mouse monoclonal anti-GM130 (western 1:2,000, cat #610822; BD Biosciences), Mouse monoclonal anti- SQSTM1/p62 (immunofluorescence 1:200, cat #610832; BD Biosciences), Rabbit polyclonal anti–C. violaceum (homemade, immunofluorescence 1:1,000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-RFP (western 1:5,000, cat #PM005; MBL), Rabbit polyclonal anti-TUFM (western 1:5,000, immunofluorescence 1:1,000, cat #HPA024087; Sigma-Aldrich), Rabbit polyclonal anti-Lamp1 (western 1:2,000, cat #ab24170; Abcam), Rabbit polyclonal anti-Calnexin (western 1:2,000, cat #ab22595; Abcam), Rabbit polyclonal anti-Calreticulin (western 1:2,000, cat #06-661; Millipore), Rabbit polyclonal anti-Flag (western 1:5,000, cat #F7425; Sigma-Aldrich), Mouse monoclonal anti-GST (western 1:2,000, cat #2624; Cell Signaling Technology), Mouse monoclonal anti-His (western 1:2,000, cat #2366; Cell Signaling Technology), Mouse monoclonal anti-ubiquitin (western 1:1,000, cat #sc-8017; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Mouse monoclonal anti-HA (western 1:5,000, cat #901501; BioLegend), Rabbit monoclonal anti-LC3C (western 1:5,000, cat #150367; Abcam), Rabbit polyclonal anti-TFEB (western 1:1,000, immunofluorescence 1:200, cat #4240; Cell Signaling Technology), Rabbit monoclonal anti–phospho-TFEB (Ser211) (western 1:1,000, cat #37681; Cell Signaling Technology), Rabbit polyclonal anti-Lamin B1 (western 1:5,000, cat #A1910; ABclonal), Rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (western 1:5,000, cat #sc-8334; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Mouse monoclonal anti-Tom20 (western 1:1,000, immunofluorescence 1:200, cat #sc-17764; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Mouse monoclonal anti-HSP60 (western 1:5,000, cat #66041-1-Ig; Proteintech), and Mouse monoclonal anti-Cytokeratin 18 (immunofluorescence 1:400, cat #66187-1-Ig; Proteintech). Rabbit polyclonal anti-ATG5 (western 1:1,000, cat #10181-2-AP; Proteintech), Rabbit polyclonal anti-Tim23 (western 1:1,000, cat #11123-1-AP; Proteintech), and Rabbit polyclonal anti-TFEB (western 1:3,000, cat #13372-1-AP; Proteintech) were used to detect TFEB protein in mouse-derived cells. CoraLite Plus 488–conjugated F4/80 polyclonal antibody (immunofluorescence 1:200, cat #CL488-28463; Proteintech). 3-Methyladenine (cat #S2767), Mdivi (cat #S7162), Oligomycin (cat #E1251), and Torin1 (cat #S2827) were purchased from Selleck. Antimycin A (cat #1397-94-0) was from Maokang Biotechnology. MitoTracker (cat #M7512) was from Invitrogen. CCCP was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cells culture and treatment

HeLa (cat #CRM-CCL-2; ATCC, female), HEK293T (cat #CRL-3216; ATCC, female), MEF (cat #CRL-2991; ATCC), Huh7, and HepG2 (HB-8065; ATCC) cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. AML12 cells (CL-0602) and primary mouse HSCs (CP-M041) were purchased from Procell and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 using the matched complete AML12 cells medium (CM-0602) and complete HSC medium (CM-M041), respectively.

HeLa GSDMD−/− cells, provided by the laboratory of Feng Shao at the National Institute of Biological Sciences in Beijing, China, were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator and regularly tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. HEK293T cells underwent specific experimental treatments: CCCP (10 µM, 21 h) was used to induce mitophagy. Bafilomycin A1 (0.5 µM, 10 h) was used to inhibit autophagy. Mdivi-1 (20 µM, 5 h) was employed as a chemotherapy drug to block mitophagy. Additionally, Torin1 (330 nM, 4 h) was utilized to induce TFEB nuclear translocation in HeLa cells and 293T cells. HeLa cells were also exposed to CCCP (10 µM, 2 h) to induce mitochondrial fragmentation.

Bacterial strains and infections

C. violaceum strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with ampicillin (20 µg/ml) and then subcultured (1:100) in fresh LB medium for 2.5–3 h.

293T, KC, HSC, HepG2, Huh 7, AML12, MEF, or ATG5−/− MEF cells were seeded in 24-well plates and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. The next day, the culture media were replaced to DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, excluding antibiotics, prior to bacterial infection. C. violaceum strains (both WT and mutant strains) were added to the culture medium at a MOI of 5 to infect 293T, HSC, HepG2, Huh 7, AML12, MEF, or ATG5−/− MEF cells. The MOI of Kupffer is 2.

GSDMD−/− HeLa cells (2.5 × 105 cells/well) were employed in the C. violaceum infection experiment to prevent potential pyroptosis. Cells were pre-seeded in 24-well plates and then exposed to C. violaceum strains at a MOI of 10 for 2 h. Extracellular bacteria were then removed by washing four times with PBS, and the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 100 µg/ml gentamicin and supplemented with 10% FBS. Subsequently, the cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for an additional 2 h before harvesting.

Construction of C. violaceum mutant strains

The ΔcipB strain of C. violaceum (12472; ATCC) was created through double homologous recombination using the suicide vector pDM4-SacB. The fragment Ser2-Ala583 of CipB was deleted from C. violaceum. The 600-bp DNA fragments upstream and downstream of the deleted region were individually amplified and then combined using overlap PCR. The resulting plasmid was transferred into the Escherichia coli DH5αλpir strain. Following sequence verification, the pDM4 ΔcipB plasmid was electroporated into the E. coli SM10λpir strain and then transferred into C. violaceum through conjugational mating. Transconjugants were screened on a 2YT agar plate supplemented with 25 µg/ml chloramphenicol and 100 µg/ml ampicillin. Further selection of recombinants was carried out on 2YT agar plates (without NaCl) containing 10% sucrose. Verification of mutant strains was performed through PCR and DNA sequencing. The same methodology was applied to create the ΔCpi-1/-1a strain, ΔCpi-2 strain, and ΔcopD strain.

To complement CipB or mutants in C. violaceum ΔcipB strain, WT CipB or mutants were constructed in pBBR1MCS2 plasmid. Then plasmid was electroporated into C. violaceum ΔcipB strain.

Cell transfection and immunofluorescence

Coverslips were pre-coated with poly-D-Lysine (25 µg/ml) for 12 h at 37°C before seeding 293T cells. Cells were transfected with JetPRIME (Polyplus Transfection) or VigoFect (Vigorous Biotechnology) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with 50 µg/ml digitonin (for LC3 staining) for 20 min or 0.1% Triton X-100 (for other antibodies) for 30 min at room temperature. Following blocking with 2% BSA for 30 min at room temperature, cells were incubated with the specified primary antibody overnight at 4°C, then with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Roche). To detect mitochondrial membrane potential, cells were incubated with 100 nM MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Molecular Probes) for 45 min and subjected to immunofluorescence. Subsequently, fluorescence images were captured using a spinning disk confocal microscope (Andor Technology) with a 100× objective, and image analysis was performed using ImageJ software.

Subcellular fractionation

To isolate mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions, 2 × 106 293T cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 3 min in a 1.5-ml EP tube. The cells were lysed on rotation at 4°C for 30 min in 400 μl digitonin buffer (150 mM NaCI, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 25 µg/ml digitonin [TargetMol], and protease and phosphatase inhibitors). The resulting cell supernatant was then collected by centrifugation at 4°C, 2,000 g for 10 min, and transferred to a new tube. Cytosolic fractions were obtained through three centrifugations of the supernatant at 20,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet containing mitochondria was washed in 1 ml PBS to remove residual digitonin buffer, then centrifuged at 2,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The resulting precipitate was resuspended in 400 μl NP-40 buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and lysed on ice for 30 min. This lysate was then centrifuged at 7,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to obtain the crude mitochondrial fraction.

To isolate the nuclear fraction and cytosol fraction, 3 × 106 293T cells were rinsed once with ice-cold PBS and then centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 3 min. The cell pellet (from 1 well in a 6-well dish) were resuspended and lysed on a rotator at 4°C for 10 min in 300 μl PBS containing 0.1% NP-40, along with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Subsequently, the cell lysates underwent centrifugation at 9.1 × 103 g for 10 s, leading to the collection of the cytosolic fraction from the 200 μl supernatant. The pellet containing the nucleus was washed three times to remove residual cytosolic components. Subsequently, the pellet was lysed in SDS lysis buffer and sonicated to obtain the nuclear fraction.

Mitochondria isolation and proteinase K digestion assay

To examine the localization of CipB in mitochondria, 293T cells cultured in two 10-cm dishes were transfected with the indicated plasmid for 12 h 2.7 × 107 293T cells washed twice with PBS, followed by centrifugation at 500 g for 3 min. The cell pellets were then resuspended in 2 ml homogenate buffer (3.5 mM Tris-HCl, 2.5 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.8) supplemented with 20 μl PMSF (100 mM) and incubated at 4°C for 2 min. Cells were homogenized using Dounce tissue grinder. Following the addition of 200 μl equilibrium buffer (350 mM Tris-HCl, 250 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl2, pH 7.8), the cell homogenate was centrifuged at 1,200 g for 3 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to new 1.5-ml tube to remove intact cells, and the supernatant was subjected to further centrifugation until no sediment was observed. Mitochondria were collected from the supernatant by centrifugation at 1.5 × 104 g for 2 min at 4°C and were subsequently washed once with 1 ml buffer A (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 320 mM sucrose, pH 7.4).

For the proteinase K digestion assay, the isolated mitochondria were resuspended in 420 μl isotonic buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 274 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, and 14 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) and divided equally into four parts. Mitochondria were then digested with gradient concentrations of proteinase K (0, 3, 6, or 12 µg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C. Subsequently, 1 μl PMSF (100 mM) was added to terminate reaction.

Construction of stable cell line

To generate 293T cells expressing GFP-LC3B and Cas9, FUIPW-GFP-LC3B or pHKO14-Cas9 was transfected into 293T cells, along with the packing plasmid psPAX2 and envelope plasmid pMD2G at a ratio of 5:3:2. After 48 h, the supernatants containing the virus were collected and clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. The clarified supernatant was added to cell culture medium, and 293T cells (HeLa cells) were infected for 48 h. Cells stably expressing GFP-LC3B were sorted by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences FACSAria II). For 293T cells stably expressing Cas9, infected positive cells were selected using blasticidin (60 µg/ml) and diluted in 96-well plates. The cells were further verified by immunoblotting.

Co-IP

293T cells (2 × 106 cells/well) were transfected with the specified plasmids. Following a 24-h incubation period, the cells were washed once and then lysed on ice for 30 min in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, and 5% glycerol, along with protease and phosphatase inhibitors from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. The resulting lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (A2220; Sigma-Aldrich), with rotation at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were then washed four times with Co-IP buffer, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted either by 50 μl FLAG peptide (0.5 mg/ml) or SDS sample buffer. The eluted samples were subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from cultured cells using Trizol (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted total RNA was then reverse transcribed to generate complementary DNA with HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme). qRT-PCR was conducted in triplicate using Cham Q Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR system. The expression levels of the tested genes were normalized to that of tubulin.

siRNA knockdown of TUFM gene

For siRNA knockdown experiments, siRNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by Huayu Gene. 293T cells were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells per well in 6-well plates and transfected with 75 nM of siRNA using jetPRIME transfection reagent from Polyplus Transfection. After 30 h after siRNA transfection, cells were further transfected with the specified plasmids using VigoFect from Vigorous Biotechnology. The silencing efficiency was verified by qRT-PCR/western blotting. The following oligonucleotides were used:

Negative control: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′;

TUFM: 5′-GAGGACCUGAAGUUCAACCUATT-3′.

Denature-IP

293T cells (2 × 106 cells/well) were transfected with the specified plasmid. The cells were washed with PBS, collected in a new 1.5-ml EP tube, and lysed in 100 μl lysis buffer (2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. After vortexing and boiling for 10 min to denature, the lysates were diluted with 900 μl dilution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100). Following ultrasonic treatment and 30 min of rotation at 4°C, the samples were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. 40 μl of supernatant was used for immunoblotting to assess target protein expression. The remaining supernatant was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag M2 beads and rotated at 4°C overnight. The immunoprecipitate was washed twice with high salt buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40) and eluted with 0.5 mg/ml FLAG peptide/SDS loading buffer. The eluted samples were subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting.

Protein purification

The DNA sequences of LC3C and TUFM were amplified from a human cDNA library, while the gene sequences of CipB, truncations, and mutants were PCR-amplified from C. violaceum (12472; ATCC). CipB and GST-CipB mFXXL(V) were cloned into the pGEX-6P-1 vector to generate N-terminal GST-tag–fused recombinant proteins. TUFM was cloned into the pET-21b vector with a C-terminal 6×His tag, and LC3C was inserted into the pET-28a vector with an N-terminal 6×His tag. Protein expression was induced in E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain (Novagen) by adding 0.4 mM IPTG at 16°C for 20 h after the absorbance at 600 nm (A600 nm) reached 0.8–1.0. His- and GST-tagged proteins were purified using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) and glutathione sepharose (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer’s instructions, with further purification performed via size-exclusion chromatography (GE Healthcare). For the purification of GST-CipB and GST-CipB mFXXL(V), known as membrane proteins with cytotoxicity, expression was induced at 37°C for 2 h with 1 mM IPTG in 10 L 2 YT medium. The bacterial pellet was harvested and subjected to high-pressure homogenization in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 400 mM NaCl, 10 % glycerol, and 1% NP-40). All purified proteins underwent assessment by SDS-PAGE gel.

GST pull-down assay

10 µg of purified GST or GST-tagged proteins were incubated with 10 µg of His-tagged protein in PBS overnight on a rotor at 4°C. Subsequently, 10 μl of glutathione sepharose (GE Healthcare) was added to capture the immune complex for 2 h at 4°C. Following this, the beads underwent six washes, and the protein was eluted using 2×SDS loading buffer before being detected through immunoblotting.

Generation of knockout 293T cell line

The single gRNA (sgRNA) targeting TUFM (5′-TGTGTGGGCGTAGTGGCGGG-3′) was designed by the Zhang Feng Lab. Subsequently, the sgRNA was cloned into pHKO-GFP-sgRNA and transfected into 293T cells expressing Cas9. Following a 24-h incubation period, GFP-positive cells were sorted using FACS and seeded into 96-well plates. Monoclonal cells were then expanded and confirmed through sequencing and western blot analysis.

To generate HeLa TFEB−/− cells, a sgRNA targeting TFEB (5′-GGTTGCGCATGCAGCTCATG-3′) was designed. The sgRNA was subsequently cloned into the pLentiCRISPRv2 puro vector and transfected into HeLa cells. After 72 h, HeLa cells were serially diluted and seeded into 96-well plates. Monoclonal cells were then expanded and confirmed through sequencing and western blot analysis.

Purification of KCs

KCs were isolated from 8 to 12-wk-old C57BL/6 mice through enzymatic digestion and mechanical dissociation. Following euthanasia, livers were perfused with PBS via the portal vein until achieving pale brown discoloration, then immediately transferred to ice-cold RPMI 1640 medium. The tissue was minced into 1–2 mm3 fragments in a 60-mm culture dish using blunt-end scissors, followed by enzymatic digestion with 0.05% collagenase IV (cat #17104019; Gibco) at 37°C for 45 min with gentle agitation. The resulting homogenate was sequentially filtered through 100-µm cell strainers (cat #BS-100-CS; Biosharp) and 40-µm cell strainers (cat #BS-40-CS; Biosharp), with each filter washed with 10 ml unsupplemented RPMI 1640.

The filtered cell suspension was centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at 4°C. After discarding the supernatant, the cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml fresh RPMI 1640 and centrifuged at 50 g for 3 min at 4°C to remove hepatocytes. The supernatant containing non-parenchymal cells was collected and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at 4°C. The final pellet was resuspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium (supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin) and seeded in 6-well plates for 2-h adhesion at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cell debris and non-adherent cells were removed by three gentle PBS washes, yielding an enriched population of KCs. KCs were identified by immunofluorescence using CoraLite Plus 488–conjugated F4/80 polyclonal antibody.

Gentamicin protection assays

HeLa GSDMD−/− cells (2.5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in 24-well plates and cultured overnight in DMEM medium without antibiotics. Cells were then infected with the specified C. violaceum strains at a MOI of 10 for 2 h. After infection, cells were washed four times and incubated in DMEM supplemented with 100 µg/ml gentamicin for 1 h to eliminate extracellular bacteria. Subsequently, cells were treated with DMEM containing 10 µg/ml gentamicin for an additional hour. Following this, cells were washed once, lysed in a buffer of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. The cell lysates were then serially diluted and plated on selective medium to quantify intracellular bacteria using colony-forming unit (CFU) assays.

RNA-Seq

293T cells were transfected with RFP-CipB or RFP-CipB mFXXL(V) for 21 h. RNA was isolated by using Trizol as described above. After enriching mRNA in OligoT and synthesizing random hexamer cDNA primers, a second PCR was performed, followed by sequencing and analysis using HiSeq 2000 from Shanghai Bosun Technology (Shanghai, China).

Mice infection assay

Five-week-old female C57BL/6N mice were evenly distributed into experimental groups based on weight. Group allocation was not blinded to investigators. Mice were intraperitoneally infected with 12 × 106 CFU of C. violaceum (in 100 μl). Mice were infected with either the WT or the ΔcipB strain for 10 h. For complementation of the ΔcipB strain with plasmid, mice were infected for 24 h. Tissue samples from the spleen and liver were collected and homogenized in PBS at room temperature. Each homogenate was diluted by plating serial dilutions onto LB agar plates containing 20 µg/ml ampicillin or 50 µg/ml kanamycin for selection. The survival rate of mice infected with different C. violaceum strains was monitored daily, and the survival rate of each group was calculated. Data analysis was performed using the Student’s t test and log-rank test with the commercial software GraphPad Prism. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered.

Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence for tissue

For immunoblotting analysis in the spleen and liver, the bacterial infection procedure was carried out according to the aforementioned protocol. Following infection, mice were sacrificed, and tissue samples were harvested and washed with PBS. The tissue samples were then homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. In the case of liver tissue, suspended fat was removed, and the supernatant was retained for immunoblotting.

For immunofluorescence analysis in the spleen and liver, a similar bacterial infection procedure was followed. After infection, mice were euthanized, and tissue samples were collected, rinsed with PBS, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, followed by a PBS wash for 1–2 h. The fixed tissues were then dehydrated with 15%, 20%, and 30% sucrose (prepared in PBS), embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound (Tissue-Tek), and stored at −80°C before being sectioned (8 µm) on a Cryostat (Leica). Slides were blocked with 2% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (pH 7.4) for 30 min and subsequently incubated with anti-LC3B and anti–C. violaceum antibodies at 4°C overnight. Secondary antibodies were diluted and applied to the slides for 90 min, followed by a 3-min staining with DAPI at room temperature in the dark. Images were acquired using a spinning disk confocal microscope (Andor Technology, UK) equipped with a 100×/1.42 NA oil immersion objective and a scientific camera, all controlled by Andor iQ3 software. Samples were excited using lasers at wavelengths of 405 nm, 488 nm, 561 nm, and 647 nm. Cells with a clear nuclear transition of TFEB were quantified. The colocalization of GFP-LC3B or GFP-hATG8s with RFP-CipB, as well as the colocalization of MitoTracker or RFP-CipB with ubiquitin, was analyzed using Fiji. The number of puncta (LC3B, GFP-LC3B, and p62) was quantified using Fiji.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Image J or GraphPad Prism. The exact number of replicates, specific statistical tests, and P values for each experiment are indicated in the figures and figure legends. All data are shown as mean ± SEM, and individual data points are presented for all data, where applicable. ns: no significant difference; *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows mitophagy induction by C. violaceum infection, independent of CopD. Fig. S2 shows that CipB has no effect on mitochondrial depolarization and Parkin location. Fig. S3 shows primary ubiquitination of CipB at K218 via K27-linked polyubiquitin chains. Fig. S4 shows TFEB activation upon C. violaceum infection. Fig. S5 shows the essential role of CipB in C. violaceum infection.

Data availability

All data are included in the manuscript or supplements and are available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shan Li’s laboratory members at Huazhong Agricultural University and Southern University of Science and Technology for helpful discussions and technical assistance. We thank Prof. Bo Zhong at Wuhan University (Wuhan, China) for kindly providing ubiquitin variant plasmids. The WT MEF cells and ATG5 knockout (ATG5−/−) MEF cells were generously gifted by Prof. Yue Xu from Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Shanghai, China). The construct encoding pmRFP-GFP-Mito was generously shared by Professor Hongbo Zhou from Huazhong Agricultural University (Wuhan, China). We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Yijin Wang from the Southern University of Science and Technology (Shenzhen, China) for kindly providing the HepG2 and Huh7 cell lines. Isolation of primary Kupffer cells were advised by Linghe Yue and Prof. Yan Yan from Huazhong Agricultural University (Wuhan, China).

This study was sponsored by grants from National Key Research and Development Programs of China (2021YFD1800404, Shan Li), National Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars (32322005, Shan Li), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32270197, Shan Li), Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation and Shiyan Innovation and Development Joint Foundation of China (2025AFD194, Shan Li), and Medical Research Innovation Project in SUSTech (G030410001/2).

Author contributions: Shuai Liu: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft, review, and editing. Lina Ma: data curation, investigation, and validation. Ruiqi Lyu: investigation and validation. Liangting Guo: investigation and visualization. Xing Pan: investigation. Shufan Hu: resources. Shan Li: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft, review, and editing.

References

Shan Li is lead contact.

Author notes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests exist.