Paneth cells secrete antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) to modulate composition of gut microbiota and host defense. AMPs are typically packaged into dense core vesicles (DCVs) and secreted into the intestinal lumen. However, the mechanisms underlying DCV biogenesis and secretion are still elusive. Here we identified that ERAdP was highly expressed in Paneth cells that acted as a sensor for a bacterial second messenger c-di-AMP. ERAdP deficiency caused impaired DCV biogenesis and dysfunction of Paneth cells. Mechanistically, by sensing c-di-AMP, ERAdP interacted with NLRP6 and further recruited ANXA2 onto the DCV membrane in Paneth cells. The ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 complex facilitated DCV biogenesis, which enhanced antibacterial ability of intestines. Disruption of ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis led to loss of DCVs in Paneth cells and increased susceptibility to bacterial infection. Of note, ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 proteins were lowly expressed in IBD patients, and c-di-AMP treatment enhanced antibacterial capacity in antibiotic-treated mice. Our findings reveal that c-di-AMP stimulation might provide a potential therapeutic strategy for infectious disease and gut inflammation.

Introduction

Intestinal epithelium, as the first line of defense, separates host from external environment and regulates mucosal immunity by recognizing and responding to signals from the microbiota. Intestinal homeostasis maintenance requires coordinated interactions among mucosal epithelial cells, immune cells, and gut microbiota (Lockhart et al., 2024; Caballero-Flores et al., 2023). Disruption of this balance contributes to the onset and progression of various gastrointestinal disorders, including gastrointestinal infections and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Liu et al., 2025; Su et al., 2025; Kou et al., 2025; Best et al., 2025). Enteric pathogens frequently correlate with diarrheal symptoms, and acute diarrheal diseases represent a huge global health burden. Among the various cases, Salmonella infections emerge as the primary driver for hospital admissions and mortality (Cherrak et al., 2025; Yoo et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2024b; Santus et al., 2022). Intestinal epithelial cells include absorptive cells (e.g., enterocytes) and secretory cells (e.g., goblet, tuft, Paneth, and enteroendocrine cells), which are derived from intestinal stem cells (ISCs) (Beumer and Clevers, 2021). Goblet cells secrete mucus that forms a physical barrier to protect the intestinal epithelium from direct contact with microorganisms, thereby maintaining epithelial integrity (Lin et al., 2025). Tuft cells recognize succinate produced by parasitic worms to exert anti-parasitic effects (Schneider et al., 2018), while we defined that Tuft-2 cells detect bacterial metabolite N-undecanoylglycine to defend against bacterial infections (Xiong et al., 2022). Endocrine cells secrete a variety of gut hormones that regulate physiological processes, such as digestion, metabolism, and appetite, playing a critical role in maintaining metabolic balance and the stability of the body’s internal environment (Beumer et al., 2024). Paneth cells, located at the base of the crypts and interspersed with ISCs, are essential for maintaining stem cell function by providing Wnt signaling for ISC self-renewal (Sato et al., 2011). Paneth cells also secrete antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), such as lysozyme and defensins, which regulate the composition of the intestinal microbiota (Salzman et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2020) and protect against pathogens like Salmonella (Salzman et al., 2003; Vaishnava et al., 2008).

Paneth cells are distinguished by their well-developed ER and Golgi apparatus, which enable sustained high-level secretion of AMPs. Given their vital role in shaping the gut microbiota and preventing dysbiosis, precise regulation of AMP secretion is essential to the maintenance of both intestinal health and microbial balance (Pierre et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2019; Ehmann et al., 2019). Typically, AMPs are packaged within dense core vesicles (DCVs) and then released into the intestinal lumen. Understanding the regulatory mechanisms behind the biogenesis and secretion of DCVs in Paneth cells is critical for elucidating their roles in intestinal immunity. Dysfunction of AMP secretion in Paneth cells is closely associated with intestinal inflammation and diseases. For instance, Crohn’s disease (CD) risk allele, ATG16L1, has been shown to affect the granule exocytosis in Paneth cells (Matsuzawa-Ishimoto et al., 2022). Additionally, lack of vitamin D receptor in Paneth cells reduces lysozyme secretion and impairs the inhibition of pathogenic bacterial growth (Lu et al., 2021). The X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein also contributes to reduced AMP secretion and alters the gut microbiota composition (Strigli et al., 2021). NOD2 is essential for intestinal antibacterial defense by regulation of cryptdins through recognizing bacterial muramyl dipeptide in mice, whose deficiency increases susceptibility to oral infections (Kobayashi et al., 2005). In CD patients, NOD2 mutations impair Paneth cell production of α-defensins (HD-5/HD-6), weakening mucosal immunity and promoting bacterial-driven inflammation, particularly in the ileum (Wehkamp et al., 2004).

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as TLRs, nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), and retinoic acid–inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-like receptors, play an essential role in sensing microbial components and initiating a range of immune responses. In Paneth cells, enteric bacteria directly activate TLR-MyD88 signaling, thereby initiating a multifaceted antimicrobial response (Vaishnava et al., 2008). Additionally, a report showed that TLR5 is expressed specifically in Paneth cells and its activation induces expression of various host defense genes (Price et al., 2018). However, it is still elusive how Paneth cells recognize and respond to microbial stimuli in the intestinal lumen to facilitate the generation of DCVs for the sequestration of bacteria outside the epithelial layer. NLRP6 is a kind of NLRs, which is known for its role in inflammasome activation (Shen et al., 2019; Barnett et al., 2023). In intestines, NLRP6 inflammasome mediates goblet cell mucin release to combat Salmonella Typhimurium through IL-18/IL-22 signaling (Han et al., 2024) and protects against intestinal protists by sensing bacterial sphingolipids (Winsor et al., 2025). In our previous studies, we identified that the ER membrane adaptor protein (ERAdP) acts as a direct sensor for the bacterial second messenger c-di-AMP and then initiates innate immune response against bacterial infection (Xia et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2015). Here we showed that ERAdP was highly expressed in Paneth cells of small intestines (SIs). ERAdP deficiency decreased numbers of DCVs in Paneth cells. ERAdP recruited NLRP6 and ANXA2 onto the DCV membrane to participate in the package and biogenesis of DCVs in Paneth cells. Disruption of ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis in mice dramatically abolished antibacterial ability.

Results

c-di-AMP as an ERAdP ligand facilitates DCV generation in Paneth cells

Paneth cells secrete AMPs into the intestinal lumen through DCVs to protect against intestinal microbiota. To determine whether the microbiota regulated DCV biogenesis in host Paneth cells, we compared the DCVs in Paneth cells in specific pathogen–free (SPF) and germ-free (GF) mice. We found that the numbers of DCVs in Paneth cells in GF mice were dramatically decreased (Fig. 1, A and B; and Fig. S1 A). In addition, we established an antibiotic-treated (ABX) model and assessed its efficiency in clearing commensal bacteria from intestinal contents (Fig. S1 B). Similar to GF mice, the ABX model also showed significantly reduced DCV numbers in Paneth cells (Fig. 1, C and D; and Fig. S1 C). Transmission electron microscopy revealed ultrastructural changes in Paneth cells, including reduced DCVs in both ABX and GF mice (Fig. 1 E). This observation was confirmed by 3D staining, which demonstrated decreased total DCV volume in these models (Fig. 1 F).

ERAdP promotes DCV generation in Paneth cells via c-di-AMP stimulation. (A) HE staining of intestines from SPF and GF mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) AB-PAS staining of intestines from SPF and GF mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C) HE staining of intestines from control and ABX mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. ABX mice were treated with 2-wk antibiotic, and control mice were treated with water. (D) AB-PAS staining of intestines from control and ABX mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. ABX mice and control mice were treated as in C. (E) Left: Electron micrograph of SPF, ABX, and GF mice. Paneth cells were drawn with dashed white lines, normal DCVs were indicated by yellow asterisk, and abnormal DCVs were indicated by red asterisk. Scale bar: 5 μm. Right: Numbers of DCVs per Paneth cells in SPF, ABX, and GF mice were calculated (n = 10 mice for each group). (F) Left: 3D immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from littermate SPF, ABX, and GF mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and yellow: DCVs’ surface fitted by Imaris 9 software. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Volume of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (G) Left: Immunofluorescence staining of intestinal organoids treated with mock, or different stimulations of PRRs: 10 μΜ c-di-AMP disodium, 10 μΜ c-di-GMP disodium, 10 μΜ 3′3′-cGAMP disodium, 10 μΜ 2′3′-cGAMP disodium, 10 μg/ml LPS, 10 μg/ml poly (I:C) sodium, and 2 μg/ml MDP for 16 h. Green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Number of DCVs per Paneth cells was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (H) Left: Immunofluorescence staining of ileums from mice of control, ABX mock treated, or treated through intragastric gavage with c-di-AMP (25 mg/kg for mouse) twice, with treatments 12 h apart. Green: UEA-1; blue: DAPI, red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Number of DCVs per Paneth cells was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (I)Cnep1r1 FISH of 10 different tissues of WT mice. Red: Cnep1r1 probes; blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 35 μm. (J) ERAdP expression levels of indicated tissues from ERAdP-HA tag mice were detected by western blot using anti-HA antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (K)Cnep1r1 FISH of intestine of Lgr5-EGFP mice. Red: Cnep1r1 probes, green: Lgr5EGFP, blue: DAPI, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 35 μm. (L) Immunofluorescence staining showing ERAdP subcellular localization in intestines from ERAdP-HA or WT mice. Red: HA, green: WGA, blue: DAPI, and pink: lysozyme. Scale bar: 15 μm. Data in E–H are shown as means ± SEM, then significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

ERAdP promotes DCV generation in Paneth cells via c-di-AMP stimulation. (A) HE staining of intestines from SPF and GF mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) AB-PAS staining of intestines from SPF and GF mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C) HE staining of intestines from control and ABX mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. ABX mice were treated with 2-wk antibiotic, and control mice were treated with water. (D) AB-PAS staining of intestines from control and ABX mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. ABX mice and control mice were treated as in C. (E) Left: Electron micrograph of SPF, ABX, and GF mice. Paneth cells were drawn with dashed white lines, normal DCVs were indicated by yellow asterisk, and abnormal DCVs were indicated by red asterisk. Scale bar: 5 μm. Right: Numbers of DCVs per Paneth cells in SPF, ABX, and GF mice were calculated (n = 10 mice for each group). (F) Left: 3D immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from littermate SPF, ABX, and GF mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and yellow: DCVs’ surface fitted by Imaris 9 software. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Volume of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (G) Left: Immunofluorescence staining of intestinal organoids treated with mock, or different stimulations of PRRs: 10 μΜ c-di-AMP disodium, 10 μΜ c-di-GMP disodium, 10 μΜ 3′3′-cGAMP disodium, 10 μΜ 2′3′-cGAMP disodium, 10 μg/ml LPS, 10 μg/ml poly (I:C) sodium, and 2 μg/ml MDP for 16 h. Green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Number of DCVs per Paneth cells was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (H) Left: Immunofluorescence staining of ileums from mice of control, ABX mock treated, or treated through intragastric gavage with c-di-AMP (25 mg/kg for mouse) twice, with treatments 12 h apart. Green: UEA-1; blue: DAPI, red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Number of DCVs per Paneth cells was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (I)Cnep1r1 FISH of 10 different tissues of WT mice. Red: Cnep1r1 probes; blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 35 μm. (J) ERAdP expression levels of indicated tissues from ERAdP-HA tag mice were detected by western blot using anti-HA antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (K)Cnep1r1 FISH of intestine of Lgr5-EGFP mice. Red: Cnep1r1 probes, green: Lgr5EGFP, blue: DAPI, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 35 μm. (L) Immunofluorescence staining showing ERAdP subcellular localization in intestines from ERAdP-HA or WT mice. Red: HA, green: WGA, blue: DAPI, and pink: lysozyme. Scale bar: 15 μm. Data in E–H are shown as means ± SEM, then significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

c-di-AMP stimulation invivo and expression of Cnep1r1. (A) Quantification of DCV numbers per Paneth cell of SPF and GF mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (B) Intestinal lumen bacterial load analysis, quantified by qPCR of 16S rRNA gene copy number in distal ileums of control (Ctrl) and ABX mice for assessment of commensal bacteria clearance (n = 6 mice for each group). (C) Quantification of DCV numbers per Paneth cell of Ctrl and ABX mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (D) Small intestinal concentration of c-di-AMP, c-di-GMP, and cGAMP from Ctrl, ABX mock, and ABX with these ligands treatment mice was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (E) Immunofluorescence staining of ileums from ABX mice treated through intragastric gavage with c-di-AMP disodium, c-di-GMP disodium, 3′3′-cGAMP disodium, 2′3′-cGAMP disodium, LPS, poly (I:C) sodium, and MDP (25 mg/kg for mouse mouse) twice, with treatments 12 h apart. Green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. (F) Conservation analysis of ERAdP in indicated vertebrate animals. (G) Relative Cnep1r1 expression levels of indicated tissues were detected by qRT-PCR. Fold changes were normalized to endogenous 18S (n = 3 mice for each group). (H) Construction diagram of ERAdP-HA tag mouse. (I) DNA electrophoresis for ERAdP-HA tag knock-in validation. (J) DNA sequencing for ERAdP-HA tag knock-in validation. (K) Western blot for ERAdP-HA tag knock-in validation. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (L) Immunofluorescence staining of ileal crypts from mice of control, ABX mock treated, or treated through intragastric gavage with c-di-AMP (25 mg/kg for mouse mouse) twice, with treatments 12 h apart. Red: ERAdP-HA, green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 5 μm. (M) Immunofluorescence staining of ileal crypts from WT mice. Green: ERAdP-HA, blue: WGA, and red: PDI. Scale bar: 5 μm. Data in A–D are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in A–E, G, and I–M are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

c-di-AMP stimulation invivo and expression of Cnep1r1. (A) Quantification of DCV numbers per Paneth cell of SPF and GF mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (B) Intestinal lumen bacterial load analysis, quantified by qPCR of 16S rRNA gene copy number in distal ileums of control (Ctrl) and ABX mice for assessment of commensal bacteria clearance (n = 6 mice for each group). (C) Quantification of DCV numbers per Paneth cell of Ctrl and ABX mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (D) Small intestinal concentration of c-di-AMP, c-di-GMP, and cGAMP from Ctrl, ABX mock, and ABX with these ligands treatment mice was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (E) Immunofluorescence staining of ileums from ABX mice treated through intragastric gavage with c-di-AMP disodium, c-di-GMP disodium, 3′3′-cGAMP disodium, 2′3′-cGAMP disodium, LPS, poly (I:C) sodium, and MDP (25 mg/kg for mouse mouse) twice, with treatments 12 h apart. Green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. (F) Conservation analysis of ERAdP in indicated vertebrate animals. (G) Relative Cnep1r1 expression levels of indicated tissues were detected by qRT-PCR. Fold changes were normalized to endogenous 18S (n = 3 mice for each group). (H) Construction diagram of ERAdP-HA tag mouse. (I) DNA electrophoresis for ERAdP-HA tag knock-in validation. (J) DNA sequencing for ERAdP-HA tag knock-in validation. (K) Western blot for ERAdP-HA tag knock-in validation. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (L) Immunofluorescence staining of ileal crypts from mice of control, ABX mock treated, or treated through intragastric gavage with c-di-AMP (25 mg/kg for mouse mouse) twice, with treatments 12 h apart. Red: ERAdP-HA, green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 5 μm. (M) Immunofluorescence staining of ileal crypts from WT mice. Green: ERAdP-HA, blue: WGA, and red: PDI. Scale bar: 5 μm. Data in A–D are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in A–E, G, and I–M are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

To identify candidate substrates that regulated this process, we stimulated small intestinal organoids with the ligands of common PRRs. Of note, ERAdP ligand c-di-AMP dramatically increased the number of DCVs in Paneth cells of organoids. Other molecules, such as c-di-GMP, 3′3′-cGAMP and 2′3-cGAMP (ligands of STING), LPS (ligand of TLR4), poly (I:C) (ligand of TLR3 and RIG-I), and MDP (ligand of NOD2), failed to increase the DCVs (Fig. 1 G). ABX in vivo treatment caused over 50% reduction of ligands in small intestinal crypt cells. Oral c-di-AMP supplementation could restore its concentration (Fig. S1 D), leading to recovery of DCVs in Paneth cells (Fig. 1 H). However, other ligands had no such restorative effect (Fig. S1 E).

ERAdP was highly conserved across mouse, human, and other various species (Fig. S1 F). To further investigate the function of ERAdP in Paneth cells, we assessed the expression of Cnep1r1 (gene name of ERAdP) in various tissues of mice using RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays. We found that Cnep1r1 was highly expressed in SI, colon, and bone marrow (Fig. 1 I and Fig. S1 G). To test the subcellular localization of ERAdP, we generated ERAdP-HA tag mice (Fig. S1 H) and validated them (Fig. S1, I–K). In agreement with the RNA FISH results, we found ERAdP-HA was highly expressed in the SI (Fig. 1 J). We found that Cnep1r1 was highly expressed in Paneth cells, interspersed between Lgr5+ ISCs in small intestines (Fig. 1 K). Of note, ERAdP specifically localized on the DCVs of lysozyme+ Paneth cells, as evidenced by merging with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-positive vesicles (Fig. 1 L). Using ERAdP-HA mice, we found that ERAdP primarily localized to the DCVs rather than the ER in Paneth cells (Fig. S1, L and M). This DCV localization was reduced with ABX treatment but was restored upon oral c-di-AMP administration (Fig. S1 L). Collectively, these findings suggest that ERAdP localizes on the DCVs of Paneth cells and c-di-AMP facilitates the formation of Paneth DCVs.

ERAdP deficiency abrogates formation of DCVs in Paneth cells

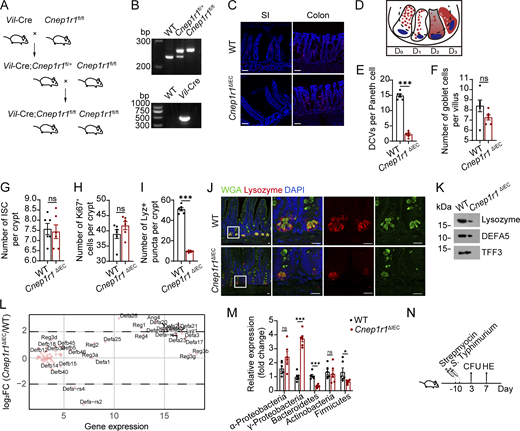

To investigate the function of ERAdP in intestine, we crossed Cnep1r1fl/fl mice with Vil-Cre mice to conditionally knock-out (KO) ERAdP in epithelial cells (Cnep1r1ΔIEC) (Fig. S2, A and B). Using this mouse model, Cnep1r1 in small intestinal Paneth cells was deleted, while the signal of Cnep1r1 remained unchanged in the lamina propria, probably in macrophages (Xia et al., 2018) (Fig. S2 C). We found that proportions of normal Paneth cells in duodenum, jejunum, and ileum were all decreased in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice compared with those of littermate WT mice, and abnormal Paneth cell ratios were increased (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S2 D). Moreover, DCVs became scarce in ERAdP-deficient Paneth cells (Fig. 2 A). However, Paneth cell numbers were not changed (Fig. 2 A). We further confirmed loss of DCVs in Paneth cells in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice through Alcian Blue-Periodic Acid Schiff (AB-PAS) staining (Fig. 2 B and Fig. S2 E). In addition, Paneth cells DCVs were assessed through 3D imaging for visualization and quantitative analysis. Our results revealed a significant reduction of DCV volume in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice compared with WT controls (Fig. 2 C). Furthermore, electron microscopy revealed that decreased numbers of DCVs, impaired apical polarization of DCVs, irregular DCV morphology, and weaker electron density in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (Fig. 2 D). In contrast, goblet cells, another secretory cell type, as well as ISCs were normal in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (Fig. 2, E and F; and Fig. S2, F and G). We also found that proliferation (Fig. 2 G and Fig. S2 H) and apoptosis (Fig. 2 H) of Paneth cells were not changed in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Then we employed differential interference contrast (DIC) imaging (Yokoi et al., 2019) to monitor DCV generation in organoids derived from Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice and their littermate controls. At the beginning, areas of DCVs in ERAdP-deficient Paneth cells were markedly less than those of WT controls. With the stimulation of cholinergic agonist carbamylcholine (CCh), DCVs were rapidly secreted into the lumen, resulting in a reduction of DCVs in Paneth cells (Fig. 2 I). At 6 h, WT Paneth cells restored DCV area to half of unstimulated level and mostly recovered at 10 h. In contrast, ERAdP-deficient Paneth cells showed less recovery during this period (Fig. 2 I). In addition, with gene ontology (GO) analysis of RNA sequencing (RNAseq), we found that membrane-associated pathways were remarkably downregulated in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (Fig. 2 J). Taken together, these results reveal that ERAdP deletion abrogates the formation of DCVs in Paneth cells.

ERAdP conditional KO mice exhibits loss of DCVs and impaired antibacterial ability. (A) Cross strategy of Vil-Cre and Cnep1r1fl/fl mice. (B) DNA electrophoresis for loxP and Vil-Cre knock-in validation. (C)Cnep1r1 FISH of SI and colon of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Red: Cnep1r1 probes; blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 70 μm. (D) Diagram of four patterns of Paneth cells normal (D0), disordered (D1), depleted (D2), and diffuse (D3). (E–I) Quantification of DCV numbers per Paneth cell (E), goblet cells per villus (F), ISC per crypt (G), Ki67+ cells per crypt (H), and Lyz+ puncta per crypt (I) of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (J) Immunofluorescence staining of ileums from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Red: lysozyme, green: WGA, and blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm. (K) Western blot for lysozyme and DEFA5 of ileal intestinal mucus layer. The intestinal contents from a 5-cm ileal segment were flushed with GuHCl and scraped using glass slides, followed by supernatant collection for western blot analysis. TFF3 secreted by goblet cells was used as a loading control. (L) AMP expression analysis with RNAseq of Cnep1r1ΔIEC versus WT mice. (M) qPCR detection of ileal luminal commensal bacteria classified by phylum (n = 6 mice for each group). (N) Schematic diagram of S. Typhimurium stimulation and detection. Data in E–I and M are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in B, C, and E–M are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

ERAdP conditional KO mice exhibits loss of DCVs and impaired antibacterial ability. (A) Cross strategy of Vil-Cre and Cnep1r1fl/fl mice. (B) DNA electrophoresis for loxP and Vil-Cre knock-in validation. (C)Cnep1r1 FISH of SI and colon of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Red: Cnep1r1 probes; blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 70 μm. (D) Diagram of four patterns of Paneth cells normal (D0), disordered (D1), depleted (D2), and diffuse (D3). (E–I) Quantification of DCV numbers per Paneth cell (E), goblet cells per villus (F), ISC per crypt (G), Ki67+ cells per crypt (H), and Lyz+ puncta per crypt (I) of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (J) Immunofluorescence staining of ileums from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Red: lysozyme, green: WGA, and blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm. (K) Western blot for lysozyme and DEFA5 of ileal intestinal mucus layer. The intestinal contents from a 5-cm ileal segment were flushed with GuHCl and scraped using glass slides, followed by supernatant collection for western blot analysis. TFF3 secreted by goblet cells was used as a loading control. (L) AMP expression analysis with RNAseq of Cnep1r1ΔIEC versus WT mice. (M) qPCR detection of ileal luminal commensal bacteria classified by phylum (n = 6 mice for each group). (N) Schematic diagram of S. Typhimurium stimulation and detection. Data in E–I and M are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in B, C, and E–M are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

ERAdP deficiency causes loss of DCVs in Paneth cells. (A) Upper: HE staining of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum from littermate Cnep1r1fl/fl (WT) and Vil-Cre;Cnep1r1fl/fl (Cnep1r1ΔIEC) mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. Lower: Proportion of normal and abnormal Paneth cells were quantified on the basis of whether Paneth cells displayed a typical staining pattern with distinguishable granules (normal) or disordered, depleted, and/or diffuse staining (abnormal), and numbers of Paneth cells were quantified. n = 6 mice for each group, with 20 selecting maximal crypt sections that displayed all Paneth cells within each crypt were analyzed per mouse. (B) AB-PAS staining of intestines from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Scale bar: 25 μm. (C) Left: 3D immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and yellow: DCVs’ surface fitted by Imaris 9 software. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Volume of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (D) Left: Electron micrograph of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Paneth cells were drawn with dashed white lines, normal DCVs were indicated by yellow asterisk, and abnormal DCVs were indicated by red asterisk. Scale bar: 5 μm. Right: Numbers of DCVs of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were calculated (n = 10 mice for each group). (E–G) Immunofluorescence staining of SIs from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Green: MUC2 (E), OLFM4 (F), and Ki67 (G); red: EpCAM; blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm. (H) Cleaved caspase-3 immunohistochemistry of intestines from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Apoptotic epithelial cells were indicated by black asterisk. Scale bar: 50 μm. (I) Upper left: Schematic diagram of stimulation of CCh to organoids and DIC images of organoids from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Upper right: Area of DCVs were quantified (n = 7 mice for each group). Organoids were stimulated by CCh for 10 min and then washed. Images were captured at 0, 2, 6, 10, and 24 h. Areas of DCVs were drawn with dashed red lines, and the corresponding Paneth cells were drawn with dashed black lines. Scale bar: 20 μm. (J) GO pathways enrichment analysis of downregulated genes in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice versus littermate WT mice. Gene ratio (%) indicates proportion of genes annotated to each GO term among the total set of significantly downregulated genes in Cnep1r1ΔIEC versus WT mouse intestinal crypts. Data in A, C, D, and I are shown as means ± SEM, and significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments.

ERAdP deficiency causes loss of DCVs in Paneth cells. (A) Upper: HE staining of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum from littermate Cnep1r1fl/fl (WT) and Vil-Cre;Cnep1r1fl/fl (Cnep1r1ΔIEC) mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. Lower: Proportion of normal and abnormal Paneth cells were quantified on the basis of whether Paneth cells displayed a typical staining pattern with distinguishable granules (normal) or disordered, depleted, and/or diffuse staining (abnormal), and numbers of Paneth cells were quantified. n = 6 mice for each group, with 20 selecting maximal crypt sections that displayed all Paneth cells within each crypt were analyzed per mouse. (B) AB-PAS staining of intestines from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Scale bar: 25 μm. (C) Left: 3D immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and yellow: DCVs’ surface fitted by Imaris 9 software. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Volume of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (D) Left: Electron micrograph of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Paneth cells were drawn with dashed white lines, normal DCVs were indicated by yellow asterisk, and abnormal DCVs were indicated by red asterisk. Scale bar: 5 μm. Right: Numbers of DCVs of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were calculated (n = 10 mice for each group). (E–G) Immunofluorescence staining of SIs from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Green: MUC2 (E), OLFM4 (F), and Ki67 (G); red: EpCAM; blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm. (H) Cleaved caspase-3 immunohistochemistry of intestines from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Apoptotic epithelial cells were indicated by black asterisk. Scale bar: 50 μm. (I) Upper left: Schematic diagram of stimulation of CCh to organoids and DIC images of organoids from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Upper right: Area of DCVs were quantified (n = 7 mice for each group). Organoids were stimulated by CCh for 10 min and then washed. Images were captured at 0, 2, 6, 10, and 24 h. Areas of DCVs were drawn with dashed red lines, and the corresponding Paneth cells were drawn with dashed black lines. Scale bar: 20 μm. (J) GO pathways enrichment analysis of downregulated genes in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice versus littermate WT mice. Gene ratio (%) indicates proportion of genes annotated to each GO term among the total set of significantly downregulated genes in Cnep1r1ΔIEC versus WT mouse intestinal crypts. Data in A, C, D, and I are shown as means ± SEM, and significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments.

ERAdP deficiency impairs the antibacterial ability of mice

Given that AMPs were packaged into DCVs and then secreted out from Paneth cells, we examined the package and secretion of AMPs under ERAdP deficiency. We found that lysozyme could not be packaged into DCVs in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S2, I and J). Consistently, the amount of lysozyme secreted into the intestinal lumen decreased significantly (Fig. 3 B and Fig. S2 K). We analyzed other AMPs, such as defensin DEFA5, and found that the amount of secreted DEFA5 into the intestinal lumen was also declined (Fig. 3 C and Fig. S2 K), suggesting dysfunction of Paneth cells in AMP secretion. In addition, to directly measure lysozyme secretion ability of Paneth cells, we isolated intestinal crypts and stimulated Paneth cells with CCh, followed by detection of lysozyme levels and bacteriostatic effect of the secreted supernatants (Fig. 3 D). We found that a large amount of lysozyme was secreted from WT crypts, and incubation of S. Typhimurium with their secreted supernatants showed better bacteriostatic effect (Fig. 3, E and F). On the contrary, secreted lysozyme from ERAdP deficient crypts was much lower and could not inhibit S. Typhimurium expansion (Fig. 3, E and F). mRNA expression of AMPs was not reduced but even compensatively upregulated (Fig. S2 L).

ERAdP deficiency leads to abnormal lysozyme secretion. (A) Lysozyme immunohistochemistry of intestines from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Scale bar: 70 μm. (B and C) Whole-mount images of tissues from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice taken from immediately above the ileal mucosal surface and stained. Red: lysozyme (B) and DEFA5 (C); green: WGA. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Schematic diagram of stimulation of small intestinal crypts by CCh and co-incubation of supernatant with S. Typhimurium. (E) Lysozyme in supernatant of stimulated crypts from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice after treatment of DMSO or CCh was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (F) Bacterial load analysis of S. Typhimurium in secreted supernatants. SI crypts of littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were isolated and stimulated by DMSO or CCh. The crypt-secreted supernatants were incubated with S. Typhimurium for 30 min, and CFUs were measured (n = 6 mice for each group). (G and H) Intestinal lumen (G) and tissue-associated (H) bacterial load analysis, quantified by qPCR of 16S rRNA gene copy numbers in distal ileums (n = 6 mice for each group). (I–L) Bacterial load analysis of livers (I), spleens (J), ileal contents (K) and PPs (L) of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. 3 days after S. Typhimurium infection, livers, spleens, ileal contents, and PPs were collected, and CFUs were calculated (n = 6 mice for each group). (M) Body weight changes of littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice after infection with S. Typhimurium (n = 6 mice for each group). (N) Survival rates of littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice after infection with S. Typhimurium (n = 12 mice for each group). (O) Representative pathological manifestation of intestines from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice after infected by S. Typhimurium for 7 days. Scale bar: 80 μm. Data are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (E–M) and Mantel–Cox test (N) (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in A–C and E–O are representative of at least three independent experiments.

ERAdP deficiency leads to abnormal lysozyme secretion. (A) Lysozyme immunohistochemistry of intestines from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Scale bar: 70 μm. (B and C) Whole-mount images of tissues from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice taken from immediately above the ileal mucosal surface and stained. Red: lysozyme (B) and DEFA5 (C); green: WGA. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Schematic diagram of stimulation of small intestinal crypts by CCh and co-incubation of supernatant with S. Typhimurium. (E) Lysozyme in supernatant of stimulated crypts from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice after treatment of DMSO or CCh was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (F) Bacterial load analysis of S. Typhimurium in secreted supernatants. SI crypts of littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were isolated and stimulated by DMSO or CCh. The crypt-secreted supernatants were incubated with S. Typhimurium for 30 min, and CFUs were measured (n = 6 mice for each group). (G and H) Intestinal lumen (G) and tissue-associated (H) bacterial load analysis, quantified by qPCR of 16S rRNA gene copy numbers in distal ileums (n = 6 mice for each group). (I–L) Bacterial load analysis of livers (I), spleens (J), ileal contents (K) and PPs (L) of WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. 3 days after S. Typhimurium infection, livers, spleens, ileal contents, and PPs were collected, and CFUs were calculated (n = 6 mice for each group). (M) Body weight changes of littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice after infection with S. Typhimurium (n = 6 mice for each group). (N) Survival rates of littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice after infection with S. Typhimurium (n = 12 mice for each group). (O) Representative pathological manifestation of intestines from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice after infected by S. Typhimurium for 7 days. Scale bar: 80 μm. Data are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (E–M) and Mantel–Cox test (N) (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in A–C and E–O are representative of at least three independent experiments.

In line with the reduced AMPs in the lumen, we found increased bacterial abundance in intestinal lumen and intestinal tissues in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice through analysis of 16S copies (Fig. 3, G and H). At the phylum level, we observed significant increase in Proteobacteria of Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice, which was increased in IBD patients, while Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were decreased in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice, which were more abundant in healthy people (Fig. S2 M). Apart from disturbed commensal microbiota, Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice exhibited damaged anti-pathogen infection ability. After S. Typhimurium infection, much more bacterial loads were detected in livers, spleens, ileal contents, and Peyer’s patches (PPs) in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (Fig. 3, I–L; and Fig. S2 N). Moreover, body weight of Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were dramatically declined, and more than half of Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice died within 10 days after infection (Fig. 3, M and N). Intestine tissues in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were severely damaged with S. Typhimurium infection (Fig. 3 O). These data indicate that deficiency of ERAdP impairs antibacterial ability.

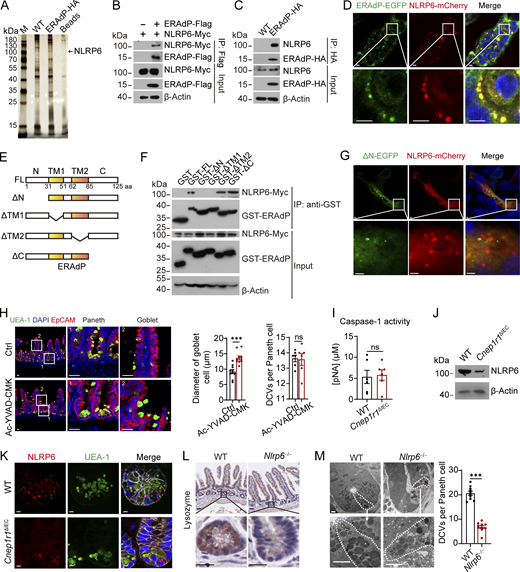

ERAdP interacts with NLRP6 in DCVs

To determine how ERAdP functions in the DCVs, we identified candidate proteins interacting with ERAdP. Intestinal crypts were isolated from ERAdP-HA tag mice and WT mice, followed with cell lysis and HA-pulldown assay. We identified NLRP6 as a candidate interacting protein of ERAdP by silver staining and mass spectrometry (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S3, A and B). We next verified the interaction between ERAdP and NLRP6 by overexpressing these two proteins in HEK293T cells followed by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) (Fig. 4 B) and also validated their interaction in ERAdP-HA mice (Fig. 4 C). Then we overexpressed ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry in Caco-2 cells and found the colocalization of these two proteins (Fig. 4 D). To further determine which region of ERAdP was required for the interaction with NLRP6, we performed domain mapping assay (Fig. 4 E). We observed that the truncation of N-terminal domain (N) and transmembrane domain 1 (TM1) in ERAdP abolished the interaction between ERAdP and NLRP6 (Fig. 4 F). In addition, N-terminal domain deficiency of ERAdP disrupted the colocalization with NLRP6 (Fig. 4 G).

ERAdP interacts with NLRP6. (A) Immunoprecipitation assay was performed using small intestinal crypts from WT and ERAdP-HA mice. Crypts were lysed and incubated with anti-HA antibody and protein A/G beads or only protein A/G beads as control. Proteins precipitated on the beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining, and differential bands were cut for mass spectrometry. The band of NLRP6 was shown. (B) co-IP analysis of NLRP6-Myc and ERAdP-Flag. NLRP6-Myc and ERAdP-Flag were cotransfected into HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-Flag antibody for immunoprecipitation; proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed by western blotting with anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (C) Endogenous co-IP of NLRP6 and ERAdP-HA. Small intestinal crypts from WT and ERAdP-HA mice were lysed and incubated with anti-HA antibody and protein A/G beads. Proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed with anti-NLRP6 and anti-HA antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (D) Colocalization analysis of ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry. ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry were cotransfected into Caco-2 cell line, and colocalization was analyzed with fluorescence imaging. Scale bar: 7.5 μm. (E and F) Domain mapping analysis of NLRP6-binding domains of ERAdP protein. Schematic diagram showing truncation mutants of ERAdP (E). FL, full-length; N: N-terminal; TM1, transmembrane 1, TM2, transmembrane 2; C, C-terminal. NLRP6-Myc were transfected into HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cell lysates were incubated with different truncation mutants of GST-ERAdP recombinant protein and GST beads. Proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed with anti-Myc and anti-GST antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control (F). (G) Colocalization analysis of ΔN-ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry. Truncation mutant forms of ΔN-ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry were cotransfected into Caco-2 cell line, and colocalization was analyzed with fluorescence imaging. Scale bar: 3.5 μm. (H) Left: Immunofluorescence staining of SIs from mice administered with DMSO or Ac-YVAD-CMK. Representative Paneth cells and goblet cells are shown. Green: UEA-1; blue: DAPI, red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Diameter of WGA+ cells (n = 10 mice and 20 villus-crypts were analyzed per mouse) and DCVs per Paneth cells were quantified (n = 6 mice and 20 villus-crypts were analyzed per mouse). (I) ELISA of caspase-1 activity examination of crypts from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (J) NLRP6 expression levels of SI crypts from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were detected by western blot with anti-NLRP6 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (K) Immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Red: NLRP6, green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 5 μm. (L) Immunohistochemistry staining of lysozyme in intestines from WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Scale bar: 35 μm. (M) Left: Electron micrograph of small intestinal crypts in littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Paneth cells were drawn with dashed white lines, normal DCVs were indicated by yellow asterisk, and abnormal DCVs were indicated by red asterisk. Scale bar: 5 μm. Right: Number of DCVs was calculated (n = 10 mice for each group). Data in H, I, and M are expressed as means ± SEM, then significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (***P < 0.00; ns, not significant). Data in A–D and F–M are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

ERAdP interacts with NLRP6. (A) Immunoprecipitation assay was performed using small intestinal crypts from WT and ERAdP-HA mice. Crypts were lysed and incubated with anti-HA antibody and protein A/G beads or only protein A/G beads as control. Proteins precipitated on the beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining, and differential bands were cut for mass spectrometry. The band of NLRP6 was shown. (B) co-IP analysis of NLRP6-Myc and ERAdP-Flag. NLRP6-Myc and ERAdP-Flag were cotransfected into HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-Flag antibody for immunoprecipitation; proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed by western blotting with anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (C) Endogenous co-IP of NLRP6 and ERAdP-HA. Small intestinal crypts from WT and ERAdP-HA mice were lysed and incubated with anti-HA antibody and protein A/G beads. Proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed with anti-NLRP6 and anti-HA antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (D) Colocalization analysis of ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry. ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry were cotransfected into Caco-2 cell line, and colocalization was analyzed with fluorescence imaging. Scale bar: 7.5 μm. (E and F) Domain mapping analysis of NLRP6-binding domains of ERAdP protein. Schematic diagram showing truncation mutants of ERAdP (E). FL, full-length; N: N-terminal; TM1, transmembrane 1, TM2, transmembrane 2; C, C-terminal. NLRP6-Myc were transfected into HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cell lysates were incubated with different truncation mutants of GST-ERAdP recombinant protein and GST beads. Proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed with anti-Myc and anti-GST antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control (F). (G) Colocalization analysis of ΔN-ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry. Truncation mutant forms of ΔN-ERAdP-EGFP and NLRP6-mCherry were cotransfected into Caco-2 cell line, and colocalization was analyzed with fluorescence imaging. Scale bar: 3.5 μm. (H) Left: Immunofluorescence staining of SIs from mice administered with DMSO or Ac-YVAD-CMK. Representative Paneth cells and goblet cells are shown. Green: UEA-1; blue: DAPI, red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Diameter of WGA+ cells (n = 10 mice and 20 villus-crypts were analyzed per mouse) and DCVs per Paneth cells were quantified (n = 6 mice and 20 villus-crypts were analyzed per mouse). (I) ELISA of caspase-1 activity examination of crypts from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (J) NLRP6 expression levels of SI crypts from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were detected by western blot with anti-NLRP6 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (K) Immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice. Red: NLRP6, green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 5 μm. (L) Immunohistochemistry staining of lysozyme in intestines from WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Scale bar: 35 μm. (M) Left: Electron micrograph of small intestinal crypts in littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Paneth cells were drawn with dashed white lines, normal DCVs were indicated by yellow asterisk, and abnormal DCVs were indicated by red asterisk. Scale bar: 5 μm. Right: Number of DCVs was calculated (n = 10 mice for each group). Data in H, I, and M are expressed as means ± SEM, then significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (***P < 0.00; ns, not significant). Data in A–D and F–M are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Identification of NLRP6 and generation of NLRP6-deficient mice. (A) Western blot of input samples used in pulldown of Fig. 4 A. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Peptides of NLRP6 were identified by mass spectrometry. (C) Western blot for ASC KO validation with anti-ASC antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (D) Left: Immunofluorescence staining of SIs from sgCtrl and sgAsc mice. Representative Paneth cells and goblet cells are shown. Green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Diameter of goblet cell numbers (n = 10 mice and 20 villus-crypts were analyzed per mouse) and DCVs per Paneth cells were quantified (n = 6 mice and 20 villus-crypts were analyzed per mouse). (E) NLRP6 expression levels of small intestinal villi from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were detected by western blot with anti-NLRP6 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (F) Relative Nlrp6 expression levels of intestinal crypts from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were detected by qRT-PCR. Fold changes were normalized to endogenous 18S (n = 6 mice for each group). (G) Construction diagram showing generation of Nlrp6−/− mice with CRISPR-Cas9. (H) DNA sequencing for Nlrp6 KO validation. (I) Western blot for NLRP6 KO validation with anti-NLRP6 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control for western blot. (J) Left: HE staining of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum from littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Scale bar: 30 μm. Middle: Proportion of normal and abnormal Paneth cells were quantified based on whether Paneth cells displayed a typical staining pattern with distinguishable granules (normal) or disordered, depleted, and/or diffuse staining (abnormal). Right: Numbers of Paneth cells were quantified. n = 6 mice, with 20 selecting maximal crypt sections that displayed all Paneth cells within each crypt were analyzed per mouse. (K) Quantification of Lyz+ puncta per crypt of WT and Nlrp6−/− mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (L) AB-PAS staining of intestines from WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Scale bar: 35 μm. (M) Left: 3D immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and yellow: DCVs’ surface fitted by Imaris software. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Volume of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group, and 20 crypts were analyzed per mouse). (N) Immunofluorescence staining of organoids from littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm. (O) Intestinal lumen (left) and tissue-associated (right) bacterial load analysis, quantified by qPCR of 16S rRNA gene copy number in distal ileums (n = 6 mice for each group). (P) qPCR detection of ileal luminal commensal bacteria classified by phylum (n = 6 mice for each group). (Q) Lysozyme in supernatant of stimulated crypts from littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice after treatment of DMSO or CCh was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (R) Bacterial load analysis of S. Typhimurium in secreted supernatants. SI crypts of littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice were isolated and stimulated by DMSO or CCh. The crypt secreted supernatants were incubated with S. Typhimurium for 30 min, and CFUs were measured (n = 6 mice for each group). Data in D–F, J, K, M, and O–R are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in A–F and H–R are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

Identification of NLRP6 and generation of NLRP6-deficient mice. (A) Western blot of input samples used in pulldown of Fig. 4 A. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Peptides of NLRP6 were identified by mass spectrometry. (C) Western blot for ASC KO validation with anti-ASC antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (D) Left: Immunofluorescence staining of SIs from sgCtrl and sgAsc mice. Representative Paneth cells and goblet cells are shown. Green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and red: EpCAM. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Diameter of goblet cell numbers (n = 10 mice and 20 villus-crypts were analyzed per mouse) and DCVs per Paneth cells were quantified (n = 6 mice and 20 villus-crypts were analyzed per mouse). (E) NLRP6 expression levels of small intestinal villi from littermate WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were detected by western blot with anti-NLRP6 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (F) Relative Nlrp6 expression levels of intestinal crypts from WT and Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice were detected by qRT-PCR. Fold changes were normalized to endogenous 18S (n = 6 mice for each group). (G) Construction diagram showing generation of Nlrp6−/− mice with CRISPR-Cas9. (H) DNA sequencing for Nlrp6 KO validation. (I) Western blot for NLRP6 KO validation with anti-NLRP6 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control for western blot. (J) Left: HE staining of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum from littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Scale bar: 30 μm. Middle: Proportion of normal and abnormal Paneth cells were quantified based on whether Paneth cells displayed a typical staining pattern with distinguishable granules (normal) or disordered, depleted, and/or diffuse staining (abnormal). Right: Numbers of Paneth cells were quantified. n = 6 mice, with 20 selecting maximal crypt sections that displayed all Paneth cells within each crypt were analyzed per mouse. (K) Quantification of Lyz+ puncta per crypt of WT and Nlrp6−/− mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (L) AB-PAS staining of intestines from WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Scale bar: 35 μm. (M) Left: 3D immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and yellow: DCVs’ surface fitted by Imaris software. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Volume of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group, and 20 crypts were analyzed per mouse). (N) Immunofluorescence staining of organoids from littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm. (O) Intestinal lumen (left) and tissue-associated (right) bacterial load analysis, quantified by qPCR of 16S rRNA gene copy number in distal ileums (n = 6 mice for each group). (P) qPCR detection of ileal luminal commensal bacteria classified by phylum (n = 6 mice for each group). (Q) Lysozyme in supernatant of stimulated crypts from littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice after treatment of DMSO or CCh was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (R) Bacterial load analysis of S. Typhimurium in secreted supernatants. SI crypts of littermate WT and Nlrp6−/− mice were isolated and stimulated by DMSO or CCh. The crypt secreted supernatants were incubated with S. Typhimurium for 30 min, and CFUs were measured (n = 6 mice for each group). Data in D–F, J, K, M, and O–R are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in A–F and H–R are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

NLRP6 is a NLR that forms an inflammasome (Li and Zhu, 2020), so we wanted to know whether NLRP6 regulated DCVs through inflammasome assembling. We administrated mice with Ac-YVAD-CMK, which is a potent and irreversible inhibitor of the inflammasome downstream enzyme caspase-1. In line with a previous report (Wlodarska et al., 2014), blocking NLRP6-mediated inflammasome pathway caused accumulation of mucus in goblet cells, while DCVs in Paneth cells were not changed (Fig. 4 H). Meanwhile, we depleted ASC, an essential component of inflammasome, through adeno-associated virus (AAV) delivering sgRNA (sgAsc) (Fig. S3 C), and found mucus accumulation within goblet cells, but no change of DCVs in Paneth cells (Fig. S3 D). We measured caspase-1 activity, which reflected the activation of inflammasome. We noticed that caspase-1 activity was not significantly changed in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (Fig. 4 I). These results suggest that NLRP6-mediated inflammasome pathway did not contribute to abnormal DCVs of Paneth cells in ERAdP-deficient mice.

We observed NLRP6 protein level was decreased in the intestinal crypts of Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (Fig. 4 J), while NLRP6 remained unchanged in the villi (Fig. S3 E). Notably, this reduction occurred without any relative changes in Nlrp6 mRNA levels in the crypt compartment (Fig. S3 F). In addition, NLRP6 was no longer positioned on the DCV membrane in Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice (Fig. 4 K). These data suggest that NLRP6 could regulate DCVs of Paneth cells by attachment on DCVs. Then we generated Nlrp6 KO mice (Nlrp6−/−) to investigate its function on DCV biogenesis (Fig. S3, G–I). Consistent with the phenotype of Cnep1r1ΔIEC mice, Nlrp6−/− mice displayed remarkably decreased numbers and volumes of DCVs in Paneth cells, and AMP lysozyme failed to be packaged into DCVs (Fig. 4 L and Fig. S3, J–M). Electron microscopy revealed the ultrastructure of DCVs was damaged in Nlrp6−/− mice (Fig. 4 M). In addition, organoids from Nlrp6−/− mice displayed less DCVs as well (Fig. S3 N). Nlrp6−/− mice also exhibited impaired antimicrobial capacity, characterized by increased bacterial colonization in the intestinal lumen and adhesion to the epithelium (Fig. S3 O), with a remarkable enrichment of Proteobacteria (Fig. S3 P). Lysozyme secretion was reduced in the isolated small intestinal crypts from Nlrp6−/− mice (Fig. S3 Q), and its bactericidal activity was impaired (Fig. S3 R). Taken together, these results indicate that ERAdP recruits NLRP6 to the DCV membrane to promote DCV biogenesis in Paneth cells.

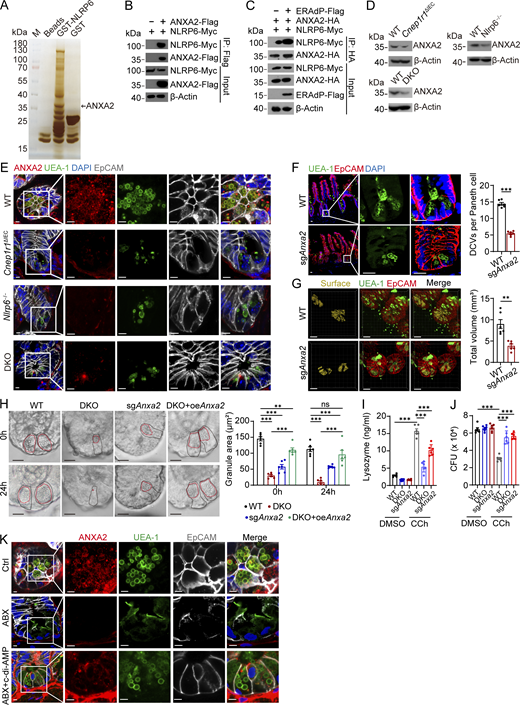

The ERAdP–NLRP6 association recruits ANXA2 onto the DCV membrane for package of DCVs

It has been reported that NLRP6 exerts antibacterial function through activation of inflammasome pathways (Wlodarska et al., 2014). However, we demonstrated that NLRP6 was located on the membrane of DCVs in Paneth cells, suggesting an alternative mechanism of antibacterial role of NLRP6. Annexin A2 (ANXA2) was identified as a candidate interacting protein of NLRP6 by GST-pulldown assay (Fig. 5 A and Fig. S4 A). ANXA2 is involved in exocytosis (Gabel et al., 2019). We further confirmed the interaction between NLRP6 and ANXA2 by cotransfection of these proteins in HEK293T cells (Fig. 5 B). To determine which region of NLRP6 was required for the interaction with ANXA2, we performed domain mapping assay (Fig. S4 B). We observed that the truncation of PYD in NLRP6 abolished the interaction between NLRP6 and ANXA2 (Fig. S4 C). Of note, ERAdP enhanced the interaction between NLRP6 and ANXA2 (Fig. 5 C). Then we tested ANXA2 protein levels and subcellular localization with ERAdP or NLRP6 deficiency. NLRP6 KO and ERAdP–NLRP6 double KO (DKO) mice showed decreased ANXA2 protein levels, and ANXA2 could not localize on the DCV membrane compared with WT mice (Fig. 5, D and E). However, absence of ERAdP and NLRP6 did not affect the mRNA level of Anxa2 (Fig. S4 D). To determine the role of ANXA2 in DCV formation, we deleted ANXA2 through AAV infection to express sgRNA-targeting ANXA2 in Cas9-expressing mice (Fig. S4, E–H). Consistent with earlier observations, ANXA2 deficiency caused decreased numbers and volumes of DCVs in Paneth cells (Fig. 5, F and G). This phenomenon was also observed in organoids, in which DCVs were scarce in ERAdP-, NLRP6-, or ANXA2-deficient Paneth cells (Fig. 5 H and Fig. S4 I). We stimulated organoids with CCh to induce DCV secretion and DCV regeneration and found that ERAdP, NLRP6, or ANXA2 deficiency disrupted replenishment of DCVs (Fig. 5 H). While ANXA2 overexpression in ERAdP- and NLRP6-deficient Paneth cells could partially restore DCV generation (Fig. 5 H). We found that bacterial burden in sgAnxa2 mice increased in the intestinal lumen and epithelium (Fig. S4 J), especially Proteobacteria (Fig. S4 K), suggesting Anxa2-deficient mice exhibited impaired antimicrobial capacity. Then we analyzed lysozyme secretion and bactericidal effect in isolated intestinal crypts. In line with ERAdP- and NLRP6-deficient mice, crypts from ANXA2-deleted mice also secreted less lysozyme with CCh stimulation, and secreted supernatants showed weaker bactericidal effect on S. Typhimurium (Fig. 5, I and J). Moreover, disruption of intestinal microbiota with ABX damaged membrane localization of ANXA2, while administration with c-di-AMP could rescue ANXA2 location on the DCV membrane (Fig. 5 K), suggesting that activation of ERAdP through c-di-AMP facilitates ANXA2 localization on the membrane of DCVs.

The ERAdP–NLRP6 association recruits ANXA2 onto the DCV membrane for generation of DCVs. (A) GST pull-down showing interaction of NLRP6 and ANXA2. Lysed small intestinal crypts from WT mice were incubated with GST-NLRP6 recombinant protein or GST recombinant protein as control. Proteins precipitated on the beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining, and differential bands were cut for mass spectrometry. Representative protein ANXA2 is shown. (B) co-IP analysis of NLRP6-Myc and ANXA2-Flag. NLRP6-Myc and ANXA2-Flag were cotransfected into HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-Flag antibody for immunoprecipitation; proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed by western blotting with anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (C) co-IP analysis of NLRP6-Myc and ANXA2-HA under the condition of absence or presence of ERAdP-Flag. β-Actin served as a loading control. (D) Western blot showing ANXA2 expression levels of SI crypts from littermate WT, Cnep1r1ΔIEC, Nlrp6−/−, and ERAdP–NLRP6 DKO mice with anti-ANXA2 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (E) Immunofluorescence staining showing ANXA2 localization in ileum crypts from littermate WT, Cnep1r1ΔIEC, Nlrp6−/−, and DKO mice. Red: ANXA2, green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 5 μm. (F) Left: Immunofluorescence staining showing DCVs in Paneth cells from littermate WT and sgAnxa2 mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Number of DCVs per Paneth cells was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (G) Left: 3D immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from WT and sgAnxa2 mice. Green: UEA-1; red: EpCAM; yellow: DCVs’ surface fitted by Imaris 9 software. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Volume of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (H) Left: DIC images of organoids from WT, Cnep1r1ΔIEC, DKO, sgAnxa2, and ANXA2-overexpressing DKO mice. Organoids were stimulated by CCh for 10 min and then washed out. Images were captured before (0 h) and after CCh stimulation (24 h). Areas of DCV were drawn with dashed red lines, and the corresponding Paneth cells were drawn with dashed black lines. Scale bar: 10 μm. Right: Area of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (I) Lysozyme in supernatant of stimulated crypts from WT, DKO, and sgAnxa2 mice after treatment of DMSO or CCh was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (J) Bacterial load analysis of S. Typhimurium in crypt supernatants. SI crypts of littermate WT, DKO and sgAnxa2 mice were isolated and stimulated by DMSO or CCh. The crypt supernatants were incubated with S. Typhimurium, and CFU was measured (n = 6 mice for each group). (K) Immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from mice of control, ABX mock treated, or treated through intragastric gavage with c-di-AMP. Green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, red: ANXA2, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 10 μm. Data in F–J are shown as means ± SEM, then significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

The ERAdP–NLRP6 association recruits ANXA2 onto the DCV membrane for generation of DCVs. (A) GST pull-down showing interaction of NLRP6 and ANXA2. Lysed small intestinal crypts from WT mice were incubated with GST-NLRP6 recombinant protein or GST recombinant protein as control. Proteins precipitated on the beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining, and differential bands were cut for mass spectrometry. Representative protein ANXA2 is shown. (B) co-IP analysis of NLRP6-Myc and ANXA2-Flag. NLRP6-Myc and ANXA2-Flag were cotransfected into HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-Flag antibody for immunoprecipitation; proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed by western blotting with anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (C) co-IP analysis of NLRP6-Myc and ANXA2-HA under the condition of absence or presence of ERAdP-Flag. β-Actin served as a loading control. (D) Western blot showing ANXA2 expression levels of SI crypts from littermate WT, Cnep1r1ΔIEC, Nlrp6−/−, and ERAdP–NLRP6 DKO mice with anti-ANXA2 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (E) Immunofluorescence staining showing ANXA2 localization in ileum crypts from littermate WT, Cnep1r1ΔIEC, Nlrp6−/−, and DKO mice. Red: ANXA2, green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 5 μm. (F) Left: Immunofluorescence staining showing DCVs in Paneth cells from littermate WT and sgAnxa2 mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Number of DCVs per Paneth cells was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (G) Left: 3D immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from WT and sgAnxa2 mice. Green: UEA-1; red: EpCAM; yellow: DCVs’ surface fitted by Imaris 9 software. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: Volume of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (H) Left: DIC images of organoids from WT, Cnep1r1ΔIEC, DKO, sgAnxa2, and ANXA2-overexpressing DKO mice. Organoids were stimulated by CCh for 10 min and then washed out. Images were captured before (0 h) and after CCh stimulation (24 h). Areas of DCV were drawn with dashed red lines, and the corresponding Paneth cells were drawn with dashed black lines. Scale bar: 10 μm. Right: Area of DCVs was quantified (n = 6 mice for each group). (I) Lysozyme in supernatant of stimulated crypts from WT, DKO, and sgAnxa2 mice after treatment of DMSO or CCh was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (J) Bacterial load analysis of S. Typhimurium in crypt supernatants. SI crypts of littermate WT, DKO and sgAnxa2 mice were isolated and stimulated by DMSO or CCh. The crypt supernatants were incubated with S. Typhimurium, and CFU was measured (n = 6 mice for each group). (K) Immunofluorescence staining of ileum crypts from mice of control, ABX mock treated, or treated through intragastric gavage with c-di-AMP. Green: UEA-1, blue: DAPI, red: ANXA2, and gray: EpCAM. Scale bar: 10 μm. Data in F–J are shown as means ± SEM, then significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

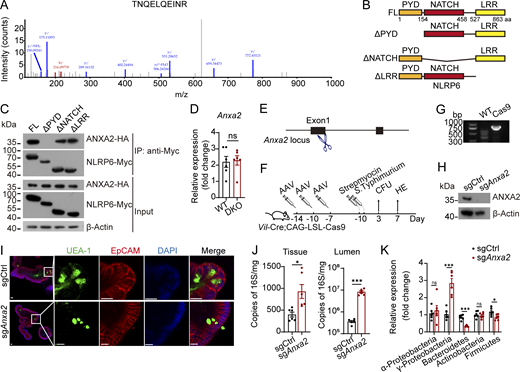

Identification of ANXA2 and generation of ANXA2-deficient mice. (A) Peptides of ANXA2 were identified by mass spectrometry. (B and C) Domain mapping analysis of ANXA2-binding domains of NLRP6 protein. Schematic diagram showing truncation mutants of NLRP6 (B). Different truncation mutants NLRP6-Myc and ANXA2-HA were transfected into HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cell lysates were incubated anti-Myc beads. Proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed with anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control (C). (D) Relative Anxa2 expression levels of intestinal crypts from WT and DKO mice were detected by qRT-PCR. Fold changes were normalized to endogenous 18S (n = 6 mice for each group). (E) Construction diagram of ANXA2 KO mouse with CRISPR-Cas9. (F) Diagram of mice injected with AAV to KO ANXA2 and then infected with S. Typhimurium. (G) DNA electrophoresis for Cas9 knock-in validation. (H) Western blot for ANXA2 KO validation with ANXA2 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (I) Immunofluorescence staining of intestinal organoids from littermate sgCtr and sgAnxa2 mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 10 μm. (J) Intestinal lumen (left) and tissue-associated (right) bacterial load analysis, quantified by qPCR of 16S rRNA gene copy number in distal ileums of WT and sgAnxa2 mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (K) qPCR detection of ileal luminal commensal bacteria classified by phylum (n = 6 mice for each group). Data in D, J, and K are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in A, C, D, and G–K are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Identification of ANXA2 and generation of ANXA2-deficient mice. (A) Peptides of ANXA2 were identified by mass spectrometry. (B and C) Domain mapping analysis of ANXA2-binding domains of NLRP6 protein. Schematic diagram showing truncation mutants of NLRP6 (B). Different truncation mutants NLRP6-Myc and ANXA2-HA were transfected into HEK293T cells for 48 h. Cell lysates were incubated anti-Myc beads. Proteins precipitated on the beads were analyzed with anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control (C). (D) Relative Anxa2 expression levels of intestinal crypts from WT and DKO mice were detected by qRT-PCR. Fold changes were normalized to endogenous 18S (n = 6 mice for each group). (E) Construction diagram of ANXA2 KO mouse with CRISPR-Cas9. (F) Diagram of mice injected with AAV to KO ANXA2 and then infected with S. Typhimurium. (G) DNA electrophoresis for Cas9 knock-in validation. (H) Western blot for ANXA2 KO validation with ANXA2 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (I) Immunofluorescence staining of intestinal organoids from littermate sgCtr and sgAnxa2 mice. Green: UEA-1, red: EpCAM, and blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 10 μm. (J) Intestinal lumen (left) and tissue-associated (right) bacterial load analysis, quantified by qPCR of 16S rRNA gene copy number in distal ileums of WT and sgAnxa2 mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (K) qPCR detection of ileal luminal commensal bacteria classified by phylum (n = 6 mice for each group). Data in D, J, and K are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data in A, C, D, and G–K are representative of at least three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

The ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis is required for antibacterial function

In Paneth cells, we co-stained these three proteins and found that they were colocalized on DCVs (Fig. S5 A). To investigate the function of ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis in Paneth cells, we generated ERAdP–NLRP6 DKO and ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 triple KO (TKO) mice. DKO and TKO exhibited greater numbers of abnormal Paneth cells and loss of DCVs compared with littermate control mice (Fig. 6 A and Fig. S5 B). Consistently, lysozyme could not be packaged into DCVs in DKO and TKO mice (Fig. 6 B and Fig. S5 C), leading to reduced lysozyme secretion and diminished bactericidal activity in TKO mice (Fig. S5, D and E). However, overexpression of Anxa2 in DKO mice rescued DCV biogenesis (Fig. 6 B). We infected these mice with S. Typhimurium and found that DKO and TKO mice showed much higher bacterial loads in livers, spleens, PPs, and ileal contents; larger weight loss and mortality; and severer intestinal destruction (Fig. 6, C–G; and Fig. S5, F and G). In contrast, overexpression of Anxa2 could ameliorate these symptoms (Fig. 6, C–G). These data suggest that the ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis plays a critical role in maintaining the normal function of DCVs and antibacterial function of Paneth cells.

DKO and TKO mice exhibit impaired antibacterial ability. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of ileal crypts from WT mice. Green: UEA-1, blue: ERAdP-HA, red: NLRP6, and pink: ANXA2. Scale bar: 5 μm. (B) Left: AB-PAS staining of intestines from ERAdP–NLRP6 DKO and ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 TKO mice. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Quantification of DCV numbers per Paneth cell of WT, DKO, and TKO mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (C) Left: Lysozyme immunohistochemistry of intestines from WT, DKO, and TKO mice. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Quantification of Lyz+ puncta per crypt of WT, DKO, and TKO mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (D) Lysozyme in supernatant of stimulated crypts from littermate WT and TKO mice after treatment of DMSO or CCh was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (E) Bacterial load analysis of S. Typhimurium in secreted supernatants. SI crypts of littermate WT and TKO mice were isolated and stimulated by DMSO or CCh (n = 6 mice for each group). (F and G) Bacterial load analysis of ileal contents (F) and PPs (G) from WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing mice. 3 days after S. Typhimurium infection, ileal contents and PPs were collected, and CFUs were calculated (n = 6 mice for each group). (H–K) Bacterial load analysis in livers (H), spleens (I), ileal contents (J), and PPs (K) of control, ABX, and ABX+c-di-AMP mice. At 3 days after S. Typhimurium infection, livers, spleens, ileal contents, and PPs were collected, and CFUs were calculated (n = 6 mice for each group). (L) Body weight change analysis of control, ABX, and ABX+c-di-AMP mice after infected by S. Typhimurium (n = 6 mice for each group). Data in B–L are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments.

DKO and TKO mice exhibit impaired antibacterial ability. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of ileal crypts from WT mice. Green: UEA-1, blue: ERAdP-HA, red: NLRP6, and pink: ANXA2. Scale bar: 5 μm. (B) Left: AB-PAS staining of intestines from ERAdP–NLRP6 DKO and ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 TKO mice. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Quantification of DCV numbers per Paneth cell of WT, DKO, and TKO mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (C) Left: Lysozyme immunohistochemistry of intestines from WT, DKO, and TKO mice. Scale bar: 35 μm. Right: Quantification of Lyz+ puncta per crypt of WT, DKO, and TKO mice (n = 6 mice for each group). (D) Lysozyme in supernatant of stimulated crypts from littermate WT and TKO mice after treatment of DMSO or CCh was measured by ELISA (n = 6 mice for each group). (E) Bacterial load analysis of S. Typhimurium in secreted supernatants. SI crypts of littermate WT and TKO mice were isolated and stimulated by DMSO or CCh (n = 6 mice for each group). (F and G) Bacterial load analysis of ileal contents (F) and PPs (G) from WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing mice. 3 days after S. Typhimurium infection, ileal contents and PPs were collected, and CFUs were calculated (n = 6 mice for each group). (H–K) Bacterial load analysis in livers (H), spleens (I), ileal contents (J), and PPs (K) of control, ABX, and ABX+c-di-AMP mice. At 3 days after S. Typhimurium infection, livers, spleens, ileal contents, and PPs were collected, and CFUs were calculated (n = 6 mice for each group). (L) Body weight change analysis of control, ABX, and ABX+c-di-AMP mice after infected by S. Typhimurium (n = 6 mice for each group). Data in B–L are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments.

The ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis is required for antibacterial function. (A) Upper: HE staining of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum from littermate WT, Cnep1r1ΔIEC, ERAdP–NLRP6 DKO, and ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 TKO mice. Scale bar: 30 μm. Lower: Proportion of normal and abnormal Paneth cells were quantified on the basis of whether Paneth cells displayed a typical staining pattern with distinguishable granules (normal) or disordered, depleted, and/or diffuse staining (abnormal). n = 6 mice, with 20 selecting maximal crypt sections that displayed all Paneth cells within each crypt were analyzed per mouse. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of ileums from WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing DKO mice. Red: lysozyme; green: WGA, blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 10 μm. (C and D) Bacterial load analysis of livers (C) and spleens (D) of WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing mice. 3 days after S. Typhimurium infection, livers and spleens were collected, and CFUs were calculated (n = 6 mice for each group). (E) Body weight change analysis of WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing DKO mice after infected by S. Typhimurium (n = 6 mice for each group). (F) Survival rates of WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing DKO mice after infected by S. Typhimurium (n = 12 for each group). (G) Representative pathological manifestation of intestines from WT, DKO, TKO, and DKO+oeAnxa2 mice at 7 days after S. Typhimurium infection. Scale bar: 40 μm. (H) Schematic diagram of mice treated by ABX and c-di-AMP. (I) Survival rates of control, ABX, and ABX+c-di-AMP mice after infected by S. Typhimurium (n = 12 mice for each group). (J) Representative pathological manifestation of intestines from control, ABX, and ABX+c-di-AMP mice after infected by S. Typhimurium for 7 days. Scale bar: 40 μm. (K) Relative expression of CNEP1R1, NLRP6, and ANXA2 of ileal CD samples detected by qRT-PCR (n = 20 clinical samples for each group). Fold changes were normalized to endogenous ACTB. Data are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (A and C–E), Mantel–Cox test (F and I), and Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test (K) (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments.

The ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis is required for antibacterial function. (A) Upper: HE staining of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum from littermate WT, Cnep1r1ΔIEC, ERAdP–NLRP6 DKO, and ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 TKO mice. Scale bar: 30 μm. Lower: Proportion of normal and abnormal Paneth cells were quantified on the basis of whether Paneth cells displayed a typical staining pattern with distinguishable granules (normal) or disordered, depleted, and/or diffuse staining (abnormal). n = 6 mice, with 20 selecting maximal crypt sections that displayed all Paneth cells within each crypt were analyzed per mouse. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of ileums from WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing DKO mice. Red: lysozyme; green: WGA, blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 10 μm. (C and D) Bacterial load analysis of livers (C) and spleens (D) of WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing mice. 3 days after S. Typhimurium infection, livers and spleens were collected, and CFUs were calculated (n = 6 mice for each group). (E) Body weight change analysis of WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing DKO mice after infected by S. Typhimurium (n = 6 mice for each group). (F) Survival rates of WT, DKO, TKO, and ANXA2-overexpressing DKO mice after infected by S. Typhimurium (n = 12 for each group). (G) Representative pathological manifestation of intestines from WT, DKO, TKO, and DKO+oeAnxa2 mice at 7 days after S. Typhimurium infection. Scale bar: 40 μm. (H) Schematic diagram of mice treated by ABX and c-di-AMP. (I) Survival rates of control, ABX, and ABX+c-di-AMP mice after infected by S. Typhimurium (n = 12 mice for each group). (J) Representative pathological manifestation of intestines from control, ABX, and ABX+c-di-AMP mice after infected by S. Typhimurium for 7 days. Scale bar: 40 μm. (K) Relative expression of CNEP1R1, NLRP6, and ANXA2 of ileal CD samples detected by qRT-PCR (n = 20 clinical samples for each group). Fold changes were normalized to endogenous ACTB. Data are shown as means ± SEM; significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (A and C–E), Mantel–Cox test (F and I), and Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test (K) (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). Data above are representative of at least three independent experiments.

We next tested antibacterial ability of ABX mice and ABX mice treated by c-di-AMP (Fig. 6 H). We found that disruption of microbiota with ABX destroyed antibacterial ability of mice, displaying worse survival rates and tissue destruction, more bacterial loads in organs, and larger weight loss (Fig. 6, I and J; and Fig. S5, H–L). Reactivation of the ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis with c-di-AMP partially restored antibacterial ability of mice (Fig. 6, I and J; and Fig. S5, H–L). Finally, we examined expression of these genes in IBD patients. We found that CNEP1R1, NLRP6, and ANXA2 exhibited reduced expression levels in ileal CD samples compared with normal tissues (Fig. 6 K). These data suggested that downregulation of CNEP1R1, NLRP6, and ANXA2 genes might be involved in the IBD pathogenesis. Taken together, the ERAdP–NLRP6–ANXA2 axis plays a key role in biogenesis of DCVs in Paneth cells, which participates in protection against bacterial infection.

Discussion