The molecular mechanism by which inborn errors of the human RNA lariat–debranching enzyme 1 (DBR1) underlie brainstem viral encephalitis is unknown. We show here that the accumulation of RNA lariats in human DBR1-deficient cells interferes with stress granule (SG) assembly, promoting the proteasome degradation of at least G3BP1 and G3BP2, two key components of SGs. In turn, impaired assembly of SGs, which normally recruit PKR, impairs PKR activation and activity against viruses, including HSV-1. Remarkably, the genetic ablation of PKR abolishes the corresponding antiviral effect of DBR1 in vitro. We also show that Dbr1Y17H/Y17H mice are susceptible to similar viral infections in vivo. Moreover, cells and brain samples from Dbr1Y17H/Y17H mice exhibit decreased G3BP1/2 expression and PKR phosphorylation. Thus, the debranching of RNA lariats by DBR1 permits G3BP1/2- and SG assembly-mediated PKR activation and cell-intrinsic antiviral immunity in mice and humans. DBR1-deficient patients are prone to viral disease because of intracellular lariat accumulation, which impairs G3BP1/2- and SG assembly-dependent PKR activation.

Introduction

Viral encephalitis is life-threatening and can strike previously healthy children. Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) is the most common viral etiology of sporadic cases (Tyler, 2018). Over the last ∼20 years, genetic etiologies of childhood HSV-1 encephalitis (HSE) have been deciphered. We and others have reported single-gene inborn errors of Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3)- and/or type I interferon (IFN)-dependent immunity, with causal genotypes for 12 genes, in children with forebrain HSE (Casrouge et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007, 2008; Bastard et al., 2021; Zhang and Casanova, 2024). Inborn errors of three other genes impairing either RIG-I-dependent type I IFN immunity (GTF3A), or type I IFN-independent antiviral immunity in cortical neurons (SNORA31, RIPK3, TMEFF1), have been found more recently in other patients with forebrain HSE (Lafaille et al., 2019; Naesens et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023; Chan et al., 2024b). Although HSE typically affects the forebrain, rare cases of hindbrain HSE have been reported. HSV-1 and other viruses, including influenza viruses and enteroviruses, can underlie brainstem encephalitis. We previously reported a severe but incomplete form of autosomal recessive (AR) DBR1 deficiency in children with brainstem encephalitis due to infection with HSV-1, influenza virus B, or norovirus (Zhang et al., 2018). More recently, we identified a patient with SARS-CoV-2 brainstem infection (Chan et al., 2024a). The patient within this group with the most severe DBR1 deficiency had several other clinical manifestations (Zhang et al., 2018): mild intrauterine growth retardation, mental retardation, and congenital neutropenia. Other recently reported patients had a lethal form of congenital ichthyosis, perhaps due to an even more severe DBR1 deficiency (Shamseldin et al., 2023). DBR1 is the only known RNA lariat-debranching enzyme and is structurally and functionally conserved from yeasts to humans (Kim et al., 2000; Chapman and Boeke, 1991; Findlay et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2015). Lariat RNAs are splicing intermediates produced by group II introns and the pre-mRNA spliceosome (Ruskin et al., 1984; Padgett et al., 1984; Peebles et al., 1986). The patients’ fibroblasts have low levels of DBR1 protein and enzymatic activity, resulting in high RNA lariat levels (Arenas and Hurwitz, 1987; Chapman and Boeke, 1991). Cell-intrinsic immunity to viruses is also impaired in both DBR1-mutated fibroblasts (Zhang et al., 2018) and human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC)-derived hindbrain neurons (Chan et al., 2024a).

Intriguingly, although patients with AR DBR1 deficiency probably accumulate RNA lariats in multiple cell types, their infectious phenotype is devastating but narrow, as it is restricted to viral brainstem encephalitis (Zhang et al., 2018). The topologically restricted nature of viral disease in these patients may reflect the pattern of DRB1 expression, which is strongest in the brainstem (Zhang et al., 2018). DBR1-deficient cells in the brainstem may accumulate more lariats than other cell types, the lariats may be more damaging in these cells, or both. Experimental studies of hPSC-derived cells normally resident in different regions both within and outside the brain should help clarify the cellular basis of disease. A first step in this direction was taken with our demonstration that DBR1-mutated hPSC-derived hindbrain neurons are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 (Chan et al., 2024a). However, the cellular basis of the other, rarer clinical manifestations of DBR1 deficiency also remains unexplained, as does the molecular basis of viral disease. The patients are susceptible to very different viruses, including HSV-1, influenza B, norovirus, and SARS-CoV-2, suggesting that DBR1 deficiency interferes with a broad mechanism of antiviral immunity. High viral loads in cultured fibroblasts and hPSC-derived neurons from the patients indicate that cell-intrinsic immunity is impaired when DBR1 is deficient. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how DBR1 deficiency favors viral infection in vitro and in vivo, and whether and how lariat accumulation impairs cell-intrinsic antiviral immunity. Given that DBR1 deficiency impairs RNA metabolism, resulting in an accumulation of RNA lariats, we hypothesized that DBR1 deficiency might disrupt cell-intrinsic RNA-sensing pathways.

Multiple cell-intrinsic antiviral strategies exist, based on the sensing of dsRNA viral intermediates or by-products (Chen and Hur, 2022). First, the endosomal TLR3-dependent induction of type I IFNs is crucial for defenses against certain viruses in the brain and lungs (Chen et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2013, 2020, 2022). However, DBR1-deficient cells respond normally via TLR3, whereas patients with mutations of the TLR3 pathway have forebrain infections, as opposed to the brainstem viral infections seen in patients with DBR1 mutations (Zhang et al., 2018). Second, activation of the IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) cytosolic OASs by dsRNA activates RNase L (Sadler and Williams, 2008). However, inherited deficiencies of the OAS-RNase L pathway lead to post-infectious, SARS-CoV-2-related hyperinflammation rather than uncontrolled viral infection in the lungs (Lee et al., 2023). Third, cytosolic RIG-I and MDA5 stimulate the downstream adaptor protein mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS), thereby inducing antiviral type I IFN production (Rehwinkel and Gack, 2020). RIG-I and MAVS deficiencies have not been reported but inherited MDA-5 deficiency underlies respiratory rhinoviral disease and enterovirus hindbrain encephalitis (Chen et al., 2021; Lamborn et al., 2017), raising the possibility that DBR1 deficiency may interfere with MDA-5. Fourth, protein kinase R (PKR) is a type I IFN-dependent ISG product that also binds to cytosolic dsRNA, inducing the integrated stress response (ISR) (Manche et al., 1992; Nanduri et al., 1998). Viral dsRNAs and IFN-I induce the phosphorylation of PKR, leading to phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), which drives a global stalling of translation and hinders viral protein synthesis (Dey et al., 2005; Su et al., 2007). We therefore decided to investigate the MAVS and PKR pathways in human DBR1-deficient cells.

Results

DBR1 deficiency impairs PKR activation by intracellular dsRNA stimulation

We explored antiviral immunity in DBR1-deficient cells by the knockdown (KD) of DBR1 (shDBR1) in BJ human fibroblasts, with the confirmation of DBR1 expression by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) (Fig. S1 A). Through the qPCR detection of intronic RNA lariats of the ID1 and DKK1 genes, two of the most prominently elevated lariats in DBR1-deficient patients’ fibroblasts (Zhang et al., 2018), we validated the decrease in RNA debranching activity in shDBR1 BJ cells (Fig. 1 A). To determine the antiviral pathway involved, shDBR1 BJ cells were stimulated with intracellularly transfected polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (polyI:C), a dsRNA mimic that stimulates both RIG-I/MDA5 and PKR, leading to MAVS-dependent type I IFN induction and PKR phosphorylation, respectively. Type I IFN and ISG expression levels were quantified by RT-qPCR. shDBR1 or overexpression barely affected the induction of type I IFN or ISGs (Fig. S1, B–D). By contrast, shDBR1 impaired the phosphorylation of PKR in BJ cells, while stable overexpression of exogenous DBR1 enhanced polyI:C-induced PKR phosphorylation (Fig. 1 B).

DBR1 regulates the activation of PKR and integrated stress response rather than IFN response. (A) RT-qPCR detection of DBR1 mRNA in BJ cells transduced with scrambled and shDBR1. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. ***, P < 0.001. (B) BJ cells with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were stimulated with polyI:C, followed by RT-qPCR analysis of the indicated IFN or ISGs. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict points that represent biological replicates. (C) RT-qPCR detection of DBR1 mRNA in BJ cells transduced with overexpressing DBR1 relative to control. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. ***, P < 0.001. (D) BJ cells with EV or DBR1 overexpression were stimulated with IFNβ, followed by RT-qPCR analysis of EV and DBR1 BJ cells for expression of the indicated ISGs. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict points that represent biological replicates. (E) RT-qPCR detection of DBR1 mRNA in HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled and shDBR1. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. ****, P < 0.0001. (F) RT-qPCR detection of DBR1 mRNA in HEK293T cells transduced with DBR1 relative to control. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. ****, P < 0.0001. (G) RT-qPCR determination of ID1, DKK1 RNA lariat levels in HEK293T scrambled control and shDBR1 cells. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (H and I) HEK293T scrambled control or shDBR1 cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 (H) or HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 (I) for 24 h, and viral replication was then detected by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (J) HEK293T cells transfected with the scramble shRNA or shDBR1 were stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml), followed by WB for indicated proteins. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (K and L) HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA, shDBR1, or shDBR1 with DBR1 for rescue were analyzed by WB with the indicated antibodies (K). GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. RT-qPCR for RNA lariat detection (L). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (M) HEK293T cells transduced with shDBR1 or shDBR1 cells transduced with DBR1 for rescue were infected with HSV-1 (left) or VSV (right), and viral mRNA was then quantified by RT-qPCR. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. **, P < 0.01. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. (N) RT-qPCR analysis of control, shDBR1-transduced and DBR1-overexpressing HEK293T cells for assessment of the expression of the indicated ISR genes. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (O) Stimulation with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) in THP-1 cells transduced with the scramble shRNA or shDBR1, followed by WB for indicated proteins. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (P) THP1 cells transduced with EV or DBR1 were stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (Q) HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were subjected to HSV-1 infection (MOI: 0.5) for various time points. WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (R and S) THP-1 cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were subjected to HSV-1 infection (MOI: 0.5) (R) or VSV infection (MOI: 0.1) (S) for various time points, followed by WB for the indicated proteins. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (T) RT-qPCR quantification of ID1 and DKK1 RNA lariat levels in fibroblasts from the control and patients. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (U–W) Cells from the control and the patient were infected with VSV at a MOI of 0.1, and RT-qPCR was then performed for detection of the expression of viral genes (U), IFN and ISG genes (V and W). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (X) Patient’s cells were rescued by transfection with DBR1, and RT-qPCR was then performed to assess ID1 and DKK1 lariat levels. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (Y) Control and patient’s cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI: 0.5), and viral mRNA was then quantified by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

DBR1 regulates the activation of PKR and integrated stress response rather than IFN response. (A) RT-qPCR detection of DBR1 mRNA in BJ cells transduced with scrambled and shDBR1. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. ***, P < 0.001. (B) BJ cells with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were stimulated with polyI:C, followed by RT-qPCR analysis of the indicated IFN or ISGs. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict points that represent biological replicates. (C) RT-qPCR detection of DBR1 mRNA in BJ cells transduced with overexpressing DBR1 relative to control. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. ***, P < 0.001. (D) BJ cells with EV or DBR1 overexpression were stimulated with IFNβ, followed by RT-qPCR analysis of EV and DBR1 BJ cells for expression of the indicated ISGs. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict points that represent biological replicates. (E) RT-qPCR detection of DBR1 mRNA in HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled and shDBR1. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. ****, P < 0.0001. (F) RT-qPCR detection of DBR1 mRNA in HEK293T cells transduced with DBR1 relative to control. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. ****, P < 0.0001. (G) RT-qPCR determination of ID1, DKK1 RNA lariat levels in HEK293T scrambled control and shDBR1 cells. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (H and I) HEK293T scrambled control or shDBR1 cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 (H) or HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 (I) for 24 h, and viral replication was then detected by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (J) HEK293T cells transfected with the scramble shRNA or shDBR1 were stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml), followed by WB for indicated proteins. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (K and L) HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA, shDBR1, or shDBR1 with DBR1 for rescue were analyzed by WB with the indicated antibodies (K). GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. RT-qPCR for RNA lariat detection (L). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (M) HEK293T cells transduced with shDBR1 or shDBR1 cells transduced with DBR1 for rescue were infected with HSV-1 (left) or VSV (right), and viral mRNA was then quantified by RT-qPCR. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. **, P < 0.01. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. (N) RT-qPCR analysis of control, shDBR1-transduced and DBR1-overexpressing HEK293T cells for assessment of the expression of the indicated ISR genes. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (O) Stimulation with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) in THP-1 cells transduced with the scramble shRNA or shDBR1, followed by WB for indicated proteins. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (P) THP1 cells transduced with EV or DBR1 were stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (Q) HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were subjected to HSV-1 infection (MOI: 0.5) for various time points. WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (R and S) THP-1 cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were subjected to HSV-1 infection (MOI: 0.5) (R) or VSV infection (MOI: 0.1) (S) for various time points, followed by WB for the indicated proteins. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (T) RT-qPCR quantification of ID1 and DKK1 RNA lariat levels in fibroblasts from the control and patients. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (U–W) Cells from the control and the patient were infected with VSV at a MOI of 0.1, and RT-qPCR was then performed for detection of the expression of viral genes (U), IFN and ISG genes (V and W). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (X) Patient’s cells were rescued by transfection with DBR1, and RT-qPCR was then performed to assess ID1 and DKK1 lariat levels. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (Y) Control and patient’s cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI: 0.5), and viral mRNA was then quantified by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

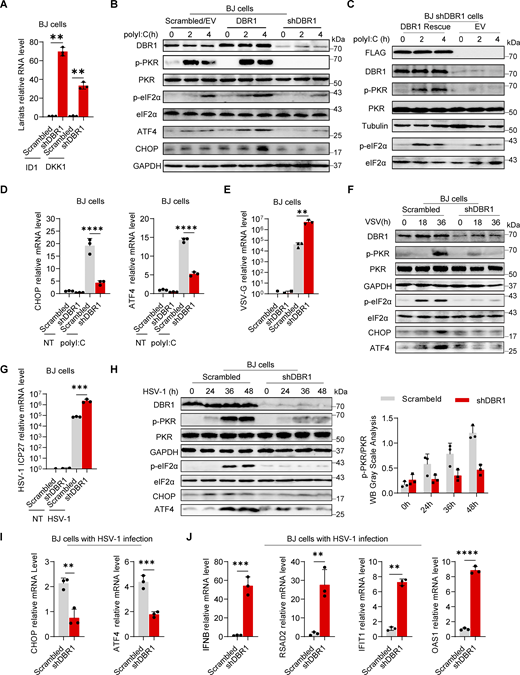

DBR1 regulates the PKR-mediated stress response during viral infection. (A) RT-qPCR determination of ID1, DKK1 RNA lariat levels in BJ scrambled control and shDBR1 cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with standard deviation (SD), and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (B) BJ cells stably expressing Flag-DBR1 and an shRNA against DBR1 together with a scrambled/EV control were transfected and stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml), and were then subjected to WB analysis with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (C) shDBR1 BJ cells transfected with EV or DBR1 were transfected with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) for 0, 2, or 4 h. Cell lysates were then prepared and subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Following stimulation with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) in scrambled control and shDBR1 BJ cells, RT-qPCR was performed to quantify CHOP and ATF4 mRNA levels. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (E) BJ scrambled control or shDBR1 cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 for 24 h, and viral replication was then detected by RT-qPCR. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (F) BJ cells transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 for various times. The cells were then lysed and subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (G) BJ cells transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 for 24 h and then quantified for viral mRNA by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001. (H) BJ cells transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 for various times. The cells were then lysed and subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies, followed by the p-PKR/PKR WB grayscale analysis of three independent experiments. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (I and J) BJ cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI: 0.5) for 24 h and then quantified for the expression of the indicated ISR genes (I), IFNB and the indicated ISGs (J) by RT-qPCR. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

DBR1 regulates the PKR-mediated stress response during viral infection. (A) RT-qPCR determination of ID1, DKK1 RNA lariat levels in BJ scrambled control and shDBR1 cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with standard deviation (SD), and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (B) BJ cells stably expressing Flag-DBR1 and an shRNA against DBR1 together with a scrambled/EV control were transfected and stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml), and were then subjected to WB analysis with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (C) shDBR1 BJ cells transfected with EV or DBR1 were transfected with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) for 0, 2, or 4 h. Cell lysates were then prepared and subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Following stimulation with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) in scrambled control and shDBR1 BJ cells, RT-qPCR was performed to quantify CHOP and ATF4 mRNA levels. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (E) BJ scrambled control or shDBR1 cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 for 24 h, and viral replication was then detected by RT-qPCR. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (F) BJ cells transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 for various times. The cells were then lysed and subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (G) BJ cells transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 for 24 h and then quantified for viral mRNA by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001. (H) BJ cells transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 for various times. The cells were then lysed and subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies, followed by the p-PKR/PKR WB grayscale analysis of three independent experiments. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (I and J) BJ cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI: 0.5) for 24 h and then quantified for the expression of the indicated ISR genes (I), IFNB and the indicated ISGs (J) by RT-qPCR. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

DBR1-deficient cells exhibit compromised stress response

PKR is one of the four known eIF2α kinases; it contributes to cellular stress responses in vitro (Taniuchi et al., 2016). Phosphorylated-eIF2α (p-eIF2α) favors the translation of ATF4, a master regulator controlling the transcription of DDIT3/CHOP, GADD45A, and other ISR genes (Ebert et al., 2010; Harding et al., 2000). We observed consistent p-eIF2α and ISR (CHOP, ATF4) expression correlating with phosphorylated-PKR (p-PKR) levels (Fig. 1 B). We excluded an off-target effect of shRNA by restoring DBR1 protein levels in shDBR1 cells, which led to increased PKR activation, eIF2α phosphorylation, and ISR expression in response to polyI:C stimulation (Fig. 1 C). We assessed ISR (e.g., CHOP, ATF4) gene expression levels by RT-qPCR after polyI:C stimulation in BJ cells with or without shDBR1 (Fig. 1 D). We observed a correlation between DBR1 levels and eIF2α-regulated ISR transcription. DBR1 was also found to be essential for optimal p-PKR and downstream ISR gene expression in HEK293T epithelial cells (Fig. S1, E–M). Furthermore, DBR1 overexpression amplified basal ISR gene expression (Fig. S1 N), and the correlation of expression of DBR1 and p-PKR was observed in THP-1 human monocyte cell line (Fig. S1, O and P). Overall, these findings suggest that low levels of DBR1 impair the activation of PKR but not the RIG-I/MDA5-dependent induction of type I IFN.

DBR1 deficiency impairs virus-induced antiviral PKR activation

We then infected BJ with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (Fig. 1, E and F) or HSV-1 (Fig. 1, G–I) and monitored the stress response. We observed an increase in viral VSV-G mRNA level in shDBR1 BJ cells, indicating that DBR1 restricts VSV infection in these cells in vitro (Fig. 1 E). Consistent with previous findings, shDBR1 resulted in a downregulation of the VSV-induced phosphorylation of PKR and eIF2α and subsequent ISR (CHOP, ATF4) expression (Fig. 1 F). Similarly, HSV-1 infection induced a weaker stress response with higher viral replication in shDBR1 BJ cells (Fig. 1. G–I). Conversely, HSV-1-infected BJ cells produced more type I IFN and ISG proteins in the absence of DBR1, possibly due to higher levels of viral replication (Fig. 1 J). Similar effects of PKR activation on DBR1-dependency during viral infection were found in HEK293T (Fig. S1 Q) and THP-1 cells (Fig. S1, R and S). These data suggest that DBR1 plays a crucial role in PKR activation by viruses or dsRNA and in subsequent ISR gene expression.

Patient-specific DBR1 mutants compromise PKR activation

To study the impact of the patients’ DBR1 genotypes on PKR-mediated stress response, we overexpressed the patient-specific, pathogenic, and severely hypomorphic DBR1 mutants (L13G, Y17H, I120T, and R197X) in HEK293T cells and stimulating them intracellularly with polyI:C. None of the variants induced a stress response like that triggered by WT DBR1 (Fig. 2 A). For the patient’s cells, we observed a simultaneous upregulation of RNA lariats, viral replication, and levels of IFNB and ISGs mRNAs after VSV infection in P1-DBR1I120T/I120T fibroblasts (Fig. S1, T–W). When stimulated intracellularly with polyI:C, cells from P1-DBR1I120T/I120T or P2-DBR1Y17H/Y17H displayed impaired PKR phosphorylation (Fig. 2, B and C). PKR phosphorylation and lariat degradation were restored by overexpressing WT DBR1 in P2-DBR1Y17H/Y17H SV40-fibroblasts (Fig. 2 C and Fig. S1 X). As in shDBR1 cells, ISR (CHOP, ATF4) expression following the VSV challenge was attenuated in the SV40-immortalized fibroblasts available from three patients with DBR1 mutations (Fig. 2 D). Phosphorylation of PKR, eIF2α, and ISR (CHOP, ATF4) expression was also restored by overexpressing WT DBR1 after VSV infection, suggesting that the DBR1 genotype is responsible for low levels of PKR activity (Fig. 2 E). Moreover, HSV-1-induced p-PKR levels were lower in the cells of P2-DBR1Y17H/Y17H than in healthy control cells despite higher viral replication (Fig. 2 F and Fig. S1 Y). Overall, these results show that the viral encephalitis-causing DBR1 genotypes resulted in an insufficient PKR activation-mediated stress response to viruses in the patients’ cells.

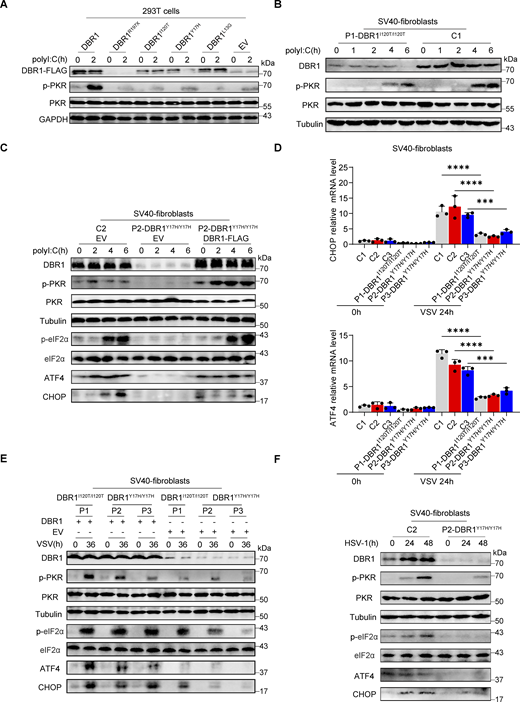

DBR1 mutants from the patients fail to potentiate the PKR-mediated stress response. (A) WT DBR1 or DBR1 variants from patients with brainstem encephalitis were overexpressed in HEK293T cells and then stimulated with polyI:C transfection (1 µg/ml). The cells were lysed and subjected to WB for detection of the indicated proteins. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B and C) SV40-transformed fibroblasts (SV40-fibroblasts) from control and two patients, P1-DBR1I120T/I120T (B) and P2-DBR1Y17H/Y17H without and with WT DBR1 rescue (C) were transfected with 1 µg/ml polyI:C and subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D) SV40-fibroblasts from control or DBR1-deficient patients were infected with VSV, and RT-qPCR was performed to assess the expression of the indicated ISR genes. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (E) SV40-fibroblasts from three patients, P1-DBR1I120T/I120T, P2-DBR1Y17H/Y17H, and P3-DBR1Y17H/Y17H without or with WT DBR1 rescue were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1, followed by WB for indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (F) SV40-fibroblasts from a healthy control and a DBR1-deficient patient were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5, followed by WB for indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

DBR1 mutants from the patients fail to potentiate the PKR-mediated stress response. (A) WT DBR1 or DBR1 variants from patients with brainstem encephalitis were overexpressed in HEK293T cells and then stimulated with polyI:C transfection (1 µg/ml). The cells were lysed and subjected to WB for detection of the indicated proteins. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B and C) SV40-transformed fibroblasts (SV40-fibroblasts) from control and two patients, P1-DBR1I120T/I120T (B) and P2-DBR1Y17H/Y17H without and with WT DBR1 rescue (C) were transfected with 1 µg/ml polyI:C and subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D) SV40-fibroblasts from control or DBR1-deficient patients were infected with VSV, and RT-qPCR was performed to assess the expression of the indicated ISR genes. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (E) SV40-fibroblasts from three patients, P1-DBR1I120T/I120T, P2-DBR1Y17H/Y17H, and P3-DBR1Y17H/Y17H without or with WT DBR1 rescue were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1, followed by WB for indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (F) SV40-fibroblasts from a healthy control and a DBR1-deficient patient were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5, followed by WB for indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

PKR is essential for DBR1-dependent antiviral immunity

Loss of the ISG protein PKR has been shown to increase susceptibility to multiple viral infections in human cells in vitro and in mice in vivo (Balachandran et al., 2000; García et al., 2007). We confirmed and extended these findings in vitro by infecting PKR-overexpressing HEK293T cells (Fig. S2, A and B) or PKR−/− BJ cells (Fig. S2 C) with VSV or HSV-1. PKR overexpression also enhanced virus-induced PKR phosphorylation, especially at earlier time points, as demonstrated by WB (Fig. S2, D and E). We investigated the role of PKR in DBR1-mediated antiviral activity by overexpressing DBR1 in PKR−/− and WT BJ cells. We then assessed protein levels by WB and infected these cells with viruses (Fig. 3 A). The protective effect of DBR1 was abolished by the genetic ablation of PKR after VSV infection, resulting in higher viral transcript quantification (Fig. 3 B), which was corroborated by fluorescence microscopy observation (Fig. S2 F) or viral titers (Fig. 3 C). Similar results were observed during HSV-1 infection (Fig. 3, D and E; and Fig. S2 F). These findings suggest that PKR is essential for DBR1 antiviral activity in these experimental conditions. Viral infection-induced p-PKR and ISR (CHOP, ATF4, GADD34) mRNA levels were enhanced by DBR1 overexpression in cells with a functional PKR but not in cells lacking PKR (Fig. 3, F and G). If DBR1 and PKR function in the same pathway, then their combined deficiency should result in a viral susceptibility profile similar to those for either of the single deficiencies. As expected, when DBR1 was silenced in PKR-deficient cells, as confirmed by WB, there was no increase in viral susceptibility, confirming their participation in the same pathway (Fig. 3, H–J). Moreover, the overexpression of PKR in DBR1-deficient cells restored not only PKR phosphorylation but also viral resistance (Fig. 3, K–M; and Fig. S2, G and H). These results suggest that PKR operates downstream from DBR1 and is required for its antiviral activity.

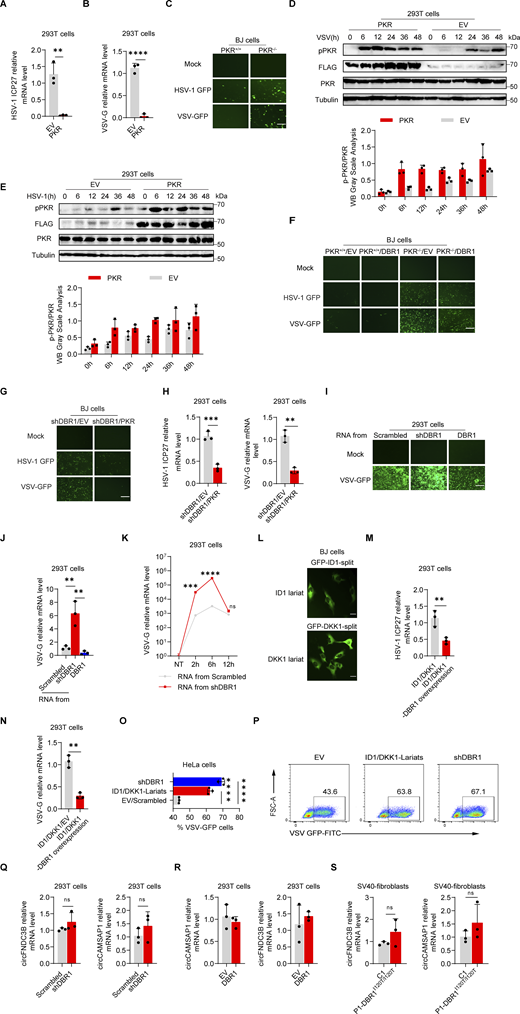

DBR1 influences PKR antiviral function by modulating the level of RNA lariats. (A and B) HEK293T cells with or without PKR overexpression were infected with HSV-1-GFP at an MOI of 0.5 (A), or VSV at an MOI of 0.1 (B) for 24 h. RT-qPCR was performed to confirm viral infection. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001. (C) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were infected with VSV-GFP at an MOI of 0.1, or HSV-1-GFP at an MOI of 0.5 for 24 h, and fluorescence imaging was then performed. Scale bars, 100 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D and E) HEK293T cells transduced with EV or PKR were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 (D), or HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 (E); WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies, followed by the p-PKR/PKR WB grayscale analysis of three independent experiments. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. (F) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with EV or DBR1 and infected with VSV-GFP (MOI: 0.1), or HSV-1-GFP (MOI: 0.5) for 24 h, and fluorescence imaging was then performed for viral GFP. Scale bars, 100 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (G) shDBR1 BJ cells transduced with EV or PKR were infected with HSV-1-GFP at an MOI of 0.5, or VSV at an MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. Scale bars, 100 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (H) shDBR1 HEK293T cells transduced with EV or PKR were infected with HSV-1-GFP at an MOI of 0.1 for 24 h or VSV at an MOI of 0.1, RT-qPCR was then performed to detect the expression of viral genes. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (I and J) RNA was extracted from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled shRNA, shDBR1, or DBR1. The purified RNA was then used to transfect HEK293T cells for 4 h. Cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.01 for 24 h. Viral titers were assessed by fluorescence imaging (I). Scale bars, 100 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Viral titers were assessed RT-qPCR (J). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (K) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled control shRNA, or shDBR1 for different time periods, and were then infected with VSV-GFP at a MOI of 0.01 for 24 h. And the viral gene expression was quantified by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (L) Diagram of RNA lariat-expressing plasmid design and fluorescence imaging. Scale bars, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (M and N) HEK293T cells expressing ID1/DKK1-Lariats or ID1/DKK1-Lariats/DBR1 were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.05 (M) or VSV at an MOI of 0.01 (N), and viral replication was then determined by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01. (O and P) HeLa cells transduced with the scrambled control, shDBR1, or ID1/DKK1-Lariats were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 for 24 h, and the viral GFP was then detected by FACS. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (Q and R) RT-qPCR assays for circRNA quantification in HEK293T cells transduced with shDBR1 (Q) or DBR1 (R) cells relative to control. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. NS, not significant. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. (S) RT-qPCR assays for circRNA in cells from patients relative to controls. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. NS, not significant. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

DBR1 influences PKR antiviral function by modulating the level of RNA lariats. (A and B) HEK293T cells with or without PKR overexpression were infected with HSV-1-GFP at an MOI of 0.5 (A), or VSV at an MOI of 0.1 (B) for 24 h. RT-qPCR was performed to confirm viral infection. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001. (C) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were infected with VSV-GFP at an MOI of 0.1, or HSV-1-GFP at an MOI of 0.5 for 24 h, and fluorescence imaging was then performed. Scale bars, 100 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D and E) HEK293T cells transduced with EV or PKR were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 (D), or HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 (E); WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies, followed by the p-PKR/PKR WB grayscale analysis of three independent experiments. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. (F) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with EV or DBR1 and infected with VSV-GFP (MOI: 0.1), or HSV-1-GFP (MOI: 0.5) for 24 h, and fluorescence imaging was then performed for viral GFP. Scale bars, 100 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (G) shDBR1 BJ cells transduced with EV or PKR were infected with HSV-1-GFP at an MOI of 0.5, or VSV at an MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. Scale bars, 100 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (H) shDBR1 HEK293T cells transduced with EV or PKR were infected with HSV-1-GFP at an MOI of 0.1 for 24 h or VSV at an MOI of 0.1, RT-qPCR was then performed to detect the expression of viral genes. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (I and J) RNA was extracted from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled shRNA, shDBR1, or DBR1. The purified RNA was then used to transfect HEK293T cells for 4 h. Cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.01 for 24 h. Viral titers were assessed by fluorescence imaging (I). Scale bars, 100 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Viral titers were assessed RT-qPCR (J). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (K) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled control shRNA, or shDBR1 for different time periods, and were then infected with VSV-GFP at a MOI of 0.01 for 24 h. And the viral gene expression was quantified by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (L) Diagram of RNA lariat-expressing plasmid design and fluorescence imaging. Scale bars, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (M and N) HEK293T cells expressing ID1/DKK1-Lariats or ID1/DKK1-Lariats/DBR1 were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.05 (M) or VSV at an MOI of 0.01 (N), and viral replication was then determined by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with t tests. **, P < 0.01. (O and P) HeLa cells transduced with the scrambled control, shDBR1, or ID1/DKK1-Lariats were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 for 24 h, and the viral GFP was then detected by FACS. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (Q and R) RT-qPCR assays for circRNA quantification in HEK293T cells transduced with shDBR1 (Q) or DBR1 (R) cells relative to control. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. NS, not significant. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. (S) RT-qPCR assays for circRNA in cells from patients relative to controls. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t tests. NS, not significant. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

PKR is required for the antiviral activity of DBR1. (A) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with EV or DBR1, followed by WB for indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with EV or DBR1 and infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ****, P < 0.0001. (C) Similar to B, except the supernatant was collected at different time points for viral titration. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ***, P < 0.001. (D) Similar to B, except the cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 (n = 3 for each group). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (E) Similar to C, except the cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ****, P < 0.0001. (F) Similar to B and D except that the cells were analyzed by WB for the indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (G) Similar to B except that expression of the indicated ISRs was detected by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (H and I) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 and infected with VSV MOI = 0.1 (H) or HSV-1-GFP MOI = 0.5 (I), followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (J) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1, and WB was then performed to detect the indicated proteins. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (K and L) BJ cells transduced with the scrambled control or shDBR1 cells together with EV or PKR overexpression were infected with VSV-GFP (MOI: 0.1) (K), or HSV-1-GFP (MOI: 0.5) (L) for 24 h, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR (n = 3 for each group). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (M) Similar to L, except that the cells overexpressing DBR1-copGFP and DBR1Y17H were also included, and the indicated proteins were detected by WB. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

PKR is required for the antiviral activity of DBR1. (A) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with EV or DBR1, followed by WB for indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with EV or DBR1 and infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ****, P < 0.0001. (C) Similar to B, except the supernatant was collected at different time points for viral titration. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ***, P < 0.001. (D) Similar to B, except the cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1 (n = 3 for each group). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (E) Similar to C, except the cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ****, P < 0.0001. (F) Similar to B and D except that the cells were analyzed by WB for the indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (G) Similar to B except that expression of the indicated ISRs was detected by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (H and I) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 and infected with VSV MOI = 0.1 (H) or HSV-1-GFP MOI = 0.5 (I), followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (J) PKR+/+ and PKR−/− BJ cells were transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1, and WB was then performed to detect the indicated proteins. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (K and L) BJ cells transduced with the scrambled control or shDBR1 cells together with EV or PKR overexpression were infected with VSV-GFP (MOI: 0.1) (K), or HSV-1-GFP (MOI: 0.5) (L) for 24 h, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR (n = 3 for each group). Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (M) Similar to L, except that the cells overexpressing DBR1-copGFP and DBR1Y17H were also included, and the indicated proteins were detected by WB. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

RNA lariat accumulation attenuates PKR activation and enhances viral susceptibility

The only known biological role of DBR1 is the debranching and degradation of RNA lariats (Mohanta and Chakrabarti, 2021). We therefore hypothesized that the lariats accumulating in shDBR1 cells would impair PKR activity. We tested this hypothesis by extracting total RNA from shDBR1 cells, which have high lariat levels, along with DBR1-overexpressing HEK293T cells and HEK293T cells with scrambled shRNA. Following the transfer of shDBR1 cell-derived RNA into HEK293T cells, there was a transient upsurge in lariat abundance, as shown by qPCR (Fig. 4 A). Interestingly, transfection of total RNA from shDBR1 cells for 2 h rendered the recipient cells more susceptible to VSV infection, as shown by diverse quantification methods, whereas RNA from control or DBR1-overexpressing cells did not (Fig. 4, B–D; and Fig. S2, I and J). Transfection with total RNA from shDBR1 cells at 12 h did not enhance viral infection, suggesting that the transfected RNA lacked stability over time (Fig. S2 K). Furthermore, transfection with RNA from shDBR1 cells for 2 h also increased the susceptibility of HEK293T cells to HSV-1 infection (Fig. 4 E). The increase in viral replication by RNA transfection remained after RNase R treatment, suggesting that lariat RNAs rather than linear RNAs were involved in this process (Fig. 4 F). Enhanced viral replication following RNA transfection was dependent on PKR, suggesting that the RNA primarily influenced PKR activity (Fig. 4 G). This is further supported by the observed decrease in PKR phosphorylation following the delivery of RNA from shDBR1 cells (Fig. 4 H). We further investigated the impact of RNA lariats on PKR activation by generating lariat-expressing plasmids carrying GFP as a reporter for successful splicing (Fig. 4 I and Fig. S2 L). Transfection with these plasmids led to lariat accumulation, as quantified by qPCR (Fig. 4 I). DBR1 overexpression in lariat-overexpressing HEK293T cells prevented viral amplification, indicating that this effect was attributable to lariats (Fig. S2, M and N). Moreover, high levels of viral replication were detected in lariat-overexpressing cells (Fig. 4, J–L; and Fig. S2, O and P), which was consistent with low levels of PKR phosphorylation after polyI:C stimulation (Fig. 4 M). Interestingly, lariat overexpression prevented PKR activation even in the presence of PKR overexpression. CircRNA, which has also been shown to inhibit PKR activation when present in abundance, resulted in enhanced viral replication (Li et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019). Even though similarities exist in structure between lariat RNAs and circRNAs, levels of circRNAs have not been reported to depend on DBR1 and were not affected here by shDBR1, DBR1 overexpression, or the DBR1 I120T genotype (Fig. S2, Q–S). Thus, the RNA lariats that accumulated in DBR1-deficient cells inhibited PKR, whereas circRNAs did not accumulate in DBR1-deficient cells and were not, therefore, involved in PKR inhibition.

RNA lariats inhibit PKR activation and weaken cellular antiviral activity. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from shDBR1 HEK293T cells, and ID1 and DKK1 lariat RNA levels were determined by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (B and C) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA, shDBR1, or DBR1 for 2 h and were then infected with VSV-GFP at a MOI of 0.01 for 24 h. Flow cytometry was then performed to analyze viral GFP levels. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D and E) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 for 2 h and infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.1 (D) or VSV at a MOI of 0.01 (E) for various time points, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with 0.8 µg/ml RnaseR-digested RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled control shRNA or shDBR1, and then infected with VSV at a MOI of 0.01 for 24 h, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. (G) HEK293T PKR+/+ and PKR−/− cells were transfected with 0.8 µg/ml RnaseR-digested RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled control shRNA or shDBR1, and infected with HSV-1 at a MOI of 0.1 for 24 h, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (H) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled control shRNA, shDBR1, or DBR1, and stimulated with polyI:C or infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 or VSV at a MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. Cell lysates were detected by WB with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (I) Diagram of RNA lariat-expressing plasmid design. This graph is created in BioRender. Ru, S. (2024) https://BioRender.com/u76g969. (J) HEK293T cells were transfected with the lariat-expressing plasmids for 24 h, and lariat RNA ID1 and DKK1 levels were measured by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (K and L) HEK293T cells were transfected with lariat-expressing plasmids for 24 h; they were then infected with HSV-GFP (MOI: 0.5) (K) or VSV-GFP (MOI: 0.1) (L) and viral gene expression was quantified by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001. (M) HEK293T cells were transfected with lariat ID1 or lariat DKK1 plasmids together with or without PKR overexpression. Cells were then stimulated with polyI:C and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

RNA lariats inhibit PKR activation and weaken cellular antiviral activity. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from shDBR1 HEK293T cells, and ID1 and DKK1 lariat RNA levels were determined by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (B and C) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA, shDBR1, or DBR1 for 2 h and were then infected with VSV-GFP at a MOI of 0.01 for 24 h. Flow cytometry was then performed to analyze viral GFP levels. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D and E) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled shRNA or shDBR1 for 2 h and infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.1 (D) or VSV at a MOI of 0.01 (E) for various time points, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with 0.8 µg/ml RnaseR-digested RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled control shRNA or shDBR1, and then infected with VSV at a MOI of 0.01 for 24 h, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. (G) HEK293T PKR+/+ and PKR−/− cells were transfected with 0.8 µg/ml RnaseR-digested RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled control shRNA or shDBR1, and infected with HSV-1 at a MOI of 0.1 for 24 h, followed by quantification of virus replication by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (H) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 µg/ml RNA purified from HEK293T cells transduced with scrambled control shRNA, shDBR1, or DBR1, and stimulated with polyI:C or infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 or VSV at a MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. Cell lysates were detected by WB with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (I) Diagram of RNA lariat-expressing plasmid design. This graph is created in BioRender. Ru, S. (2024) https://BioRender.com/u76g969. (J) HEK293T cells were transfected with the lariat-expressing plasmids for 24 h, and lariat RNA ID1 and DKK1 levels were measured by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (K and L) HEK293T cells were transfected with lariat-expressing plasmids for 24 h; they were then infected with HSV-GFP (MOI: 0.5) (K) or VSV-GFP (MOI: 0.1) (L) and viral gene expression was quantified by RT-qPCR. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001. (M) HEK293T cells were transfected with lariat ID1 or lariat DKK1 plasmids together with or without PKR overexpression. Cells were then stimulated with polyI:C and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Impaired PKR activation due to the abolition of virus-induced SG assembly in DBR1-deficient cells

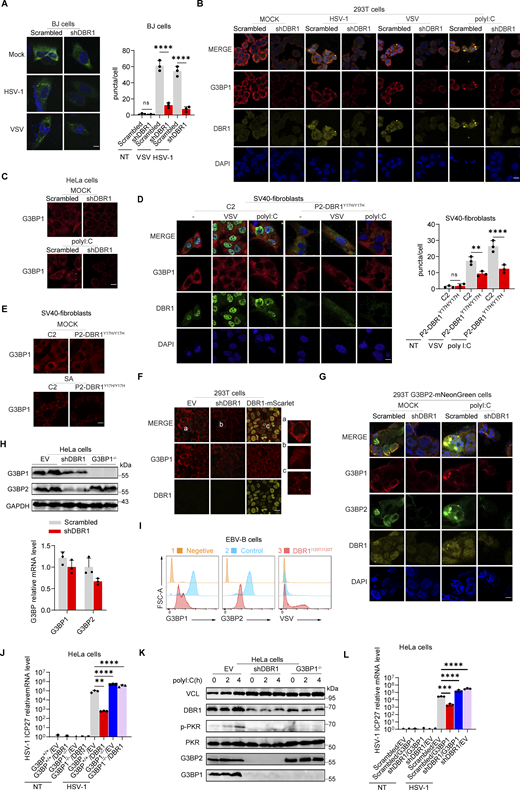

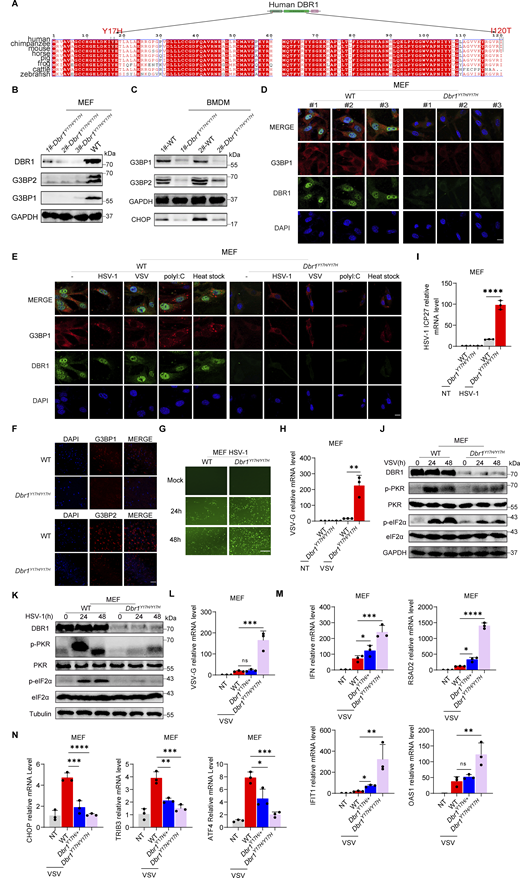

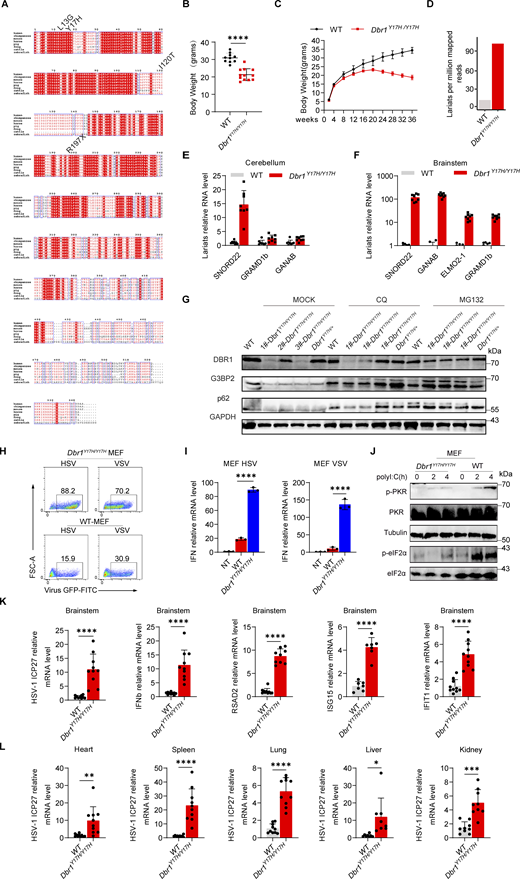

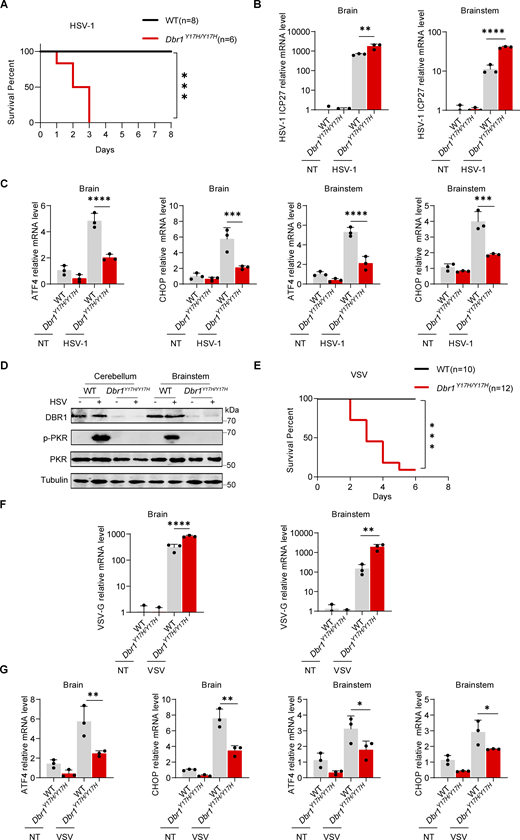

Stress granules (SGs) are subcellular structures that assemble in response to various stressors and contribute to cell-intrinsic antiviral immunity in vitro (Guan et al., 2023; Onomoto et al., 2014). Ras-GTPase-activating protein (GAP)-binding protein 1 (G3BP1) triggers RNA-dependent lipid–lipid phase transition (LLPS), which is central to SG formation (Yang et al., 2020; Guillén-Boixet et al., 2020). G3BP1 and G3BP2 are homologous proteins with a common domain structure and redundant functions for SG assembly despite having different patterns of tissue expression (Kennedy et al., 2001). PKR phosphorylates eIF2α, releasing untranslated RNA and the subsequent initiation of SG assembly. Simultaneously, PKR is recruited to SGs by G3BP1 to promote its activation (Reineke et al., 2012; Reineke and Lloyd, 2015). We confirmed the binding of G3BPs to PKR by immunoprecipitation (IP) (Fig. S3 A). HSV-1 or VSV induced G3BP-SG assembly, whereas G3BP and PKR colocalized within the SGs (Fig. S3 B). Given the role of SGs in antiviral responses, at least in vitro, we investigated SG assembly in DBR1-overexpressed or shDBR1 cells. DBR1 overexpression increased the number of G3BP foci detected (Fig. S3, C and D). shDBR1 in BJ cells reduced the number of SG puncta detected following viral treatment (Fig. 5 A). PolyI:C- or virus-triggered G3BP1 condensation was greatly impaired in shDBR1 HEK293T cells (Fig. 5 B). Moreover, shDBR1 also reduced SG formation in HeLa cells following polyI:C stimulation, confirming the dependency of DBR1 for SG assembly in multiple cell lines (Fig. 5 C). Sodium arsenite (SA) induces G3BP-SGs and activates PKR (Patel et al., 2000). Consistently, DBR1Y17H/Y17H cells from a patient with brainstem viral encephalitis displayed fewer G3BP1 aggregation speckles in response to VSV, polyI:C, or SA administration (Fig. 5, D and E). These results suggest that SGs are not correctly assembled in cells with insufficient DBR1 activity.

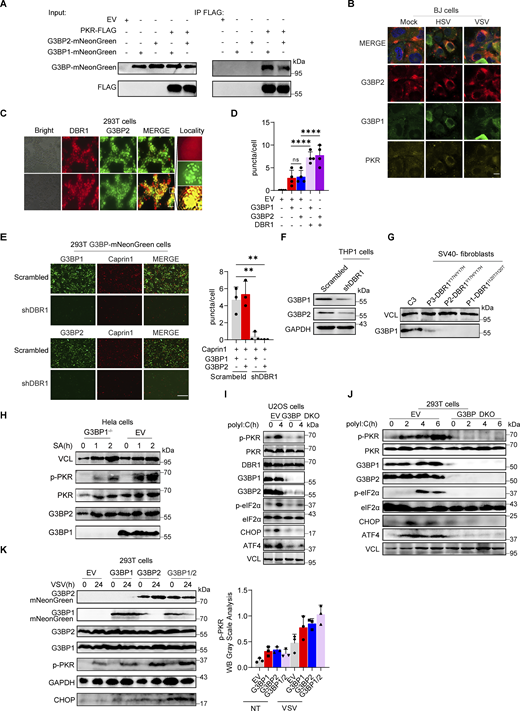

DBR1 licenses G3BP proteins to form SGs. (A) WB with indicated antibodies after immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody on lysates of HEK239T cells in an overexpression system. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) BJ cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1, or HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 for 12 h; immunofluorescence detection was then performed for PKR, G3BP2, and G3BP1-mNeonGreen. Scale bars, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (C and D) HEK293T G3BP2-mNeonGreen/DBR1-mScarlet cells were imaged (C) and the intracellular G3BP2- mNeonGreen puncta were quantified (D). Scale bars, 50 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ****, P < 0.0001. (E) Fluorescence images of HEK293T G3BP-mNeonGreen and HEK293T shDBR1/G3BP-mNeonGreen cells. Scale bars, 50 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (F and G) THP-1 cells (D) and cells from patients (E) and controls were analyzed by WB with the indicated antibodies. VCL was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (H) G3BP1−/− HeLa cells and control cells were treated with 500 µM SA, and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. VCL was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (I) G3BP DKO U2OS cells and control cells were stimulated with polyI:C (2 µg/ml) for 4 h, and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. VCL was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (J) G3BP DKO HEK293T cells and control cells were stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) for various time points, and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. VCL was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (K) HEK293T cells with overexpression of the indicated proteins were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1, and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies, followed by the p-PKR/PKR WB gray scale analysis of three independent experiments. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Graphs depict points represent biological replicates. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

DBR1 licenses G3BP proteins to form SGs. (A) WB with indicated antibodies after immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody on lysates of HEK239T cells in an overexpression system. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) BJ cells were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1, or HSV-1 at an MOI of 0.5 for 12 h; immunofluorescence detection was then performed for PKR, G3BP2, and G3BP1-mNeonGreen. Scale bars, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (C and D) HEK293T G3BP2-mNeonGreen/DBR1-mScarlet cells were imaged (C) and the intracellular G3BP2- mNeonGreen puncta were quantified (D). Scale bars, 50 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ****, P < 0.0001. (E) Fluorescence images of HEK293T G3BP-mNeonGreen and HEK293T shDBR1/G3BP-mNeonGreen cells. Scale bars, 50 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Data representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01. (F and G) THP-1 cells (D) and cells from patients (E) and controls were analyzed by WB with the indicated antibodies. VCL was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (H) G3BP1−/− HeLa cells and control cells were treated with 500 µM SA, and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. VCL was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (I) G3BP DKO U2OS cells and control cells were stimulated with polyI:C (2 µg/ml) for 4 h, and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. VCL was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (J) G3BP DKO HEK293T cells and control cells were stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) for various time points, and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies. VCL was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (K) HEK293T cells with overexpression of the indicated proteins were infected with VSV at an MOI of 0.1, and WB was then performed with the indicated antibodies, followed by the p-PKR/PKR WB gray scale analysis of three independent experiments. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Graphs depict points represent biological replicates. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

G3BP SG assembly and G3BP protein levels remain low in DBR1-deficient cells. (A) BJ cells transduced with the scrambled control shRNA or with shDBR1 were infected with the indicated viruses, and SG formation was then followed by G3BP1 staining, microscopy imaging, and the SG puncta quantification. Scale bar, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ****, P < 0.0001. (B) HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA or with shDBR1 were stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) or infected with VSV (MOI: 0.01) or HSV-1 (MOI: 0.05) and G3BP1 was then detected by fluorescence. Scale bar, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of six independent experiments. (C) HeLa cells transduced with the scrambled control shRNA or with shDBR1 were stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) and G3BP1 was then detected by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D and E) Control cells and cells from a DBR1-deficient patient were infected with VSV (MOI = 0.01) for 24 h, stimulated with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) for 4 h (D), or treated with 500 µM sodium arsenite (SA) for 1 h (E). Immunofluorescence staining was then performed for the indicated markers and SGs were quantified. Scale bar, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001. (F) HEK293T cells transduced with shDBR1 or DBR1-mscarlet were subjected to immunofluorescence staining for the indicated markers. Scale bar, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (G) HEK293T cells transduced with the scrambled control shRNA, and shDBR1 cells expressing G3BP2-mNeonGreen were transfected with polyI:C (1 µg/ml) for 4 h, and the markers indicated were then detected by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar, 20 µm. Data shown are representative of six independent experiments. (H) RT-qPCR and WB detection of G3BP expression in indicated HeLa cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Graph points represent biological replicates. (I) FACS analysis of the expression of G3BP (uninfected) and viral GFP after VSV-GFP (MOI: 0.01) infection for 24 h in EBV-B cells from a control or a DBR1-deficient patient. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (J and K) G3BP1+/+ and G3BP1−/− HeLa cells transduced with EV or DBR1 were infected with VSV-GFP (MOI: 0.01); viral gene expression was then quantified by RT-qPCR (J). Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict the mean with SD and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001. Proteins were detected by WB detection with indicated antibodies (K). Vinculin (VCL) was used as a loading control. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (L) Scrambled shRNA and shDBR1 HeLa cells transduced with EV or G3BP1 were infected with HSV-1. Viral gene expression was then quantified by RT-qPCR. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Graphs depict mean with SD, and points represent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NS, not significant, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.