The secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins is vital to the maintenance of tissue health. One major control point of this process is the Golgi apparatus, whose dysfunction causes numerous connective tissue disorders. We therefore sought to investigate the role of two Golgi organizing proteins, GMAP210 and Golgin-160, in ECM secretion. CRISPR knockout of either protein had distinct impacts on Golgi organization, with Golgin-160 knockout causing Golgi fragmentation and vesicle accumulation, and GMAP210 loss leading to cisternal fragmentation, dilation, and the accumulation of tubulovesicular structures. Both golgins were required for fibrillar collagen organization and glycosaminoglycan synthesis suggesting nonredundant functions in these processes. Furthermore, proteomics analysis revealed both shared and golgin-specific changes in the secretion of ECM proteins. We therefore propose that golgins are collectively required to create the correct physical–chemical space to support efficient ECM protein secretion, modification, and assembly. This is the first time that Golgin-160 has been shown to be required for ECM secretion.

Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex network of proteins, carbohydrates, and minerals secreted by cells to build a scaffold that forms the structural basis of most tissues. To date, current resources describing the “matrisome” have identified >1,000 proteins associated with this compartment in humans (Shao et al., 2023), explaining the capacity for extensive diversification of biochemical and mechanical properties between tissue types. The most abundant family of ECM proteins are the collagens. These proteins assemble to form the main structural components of connective tissues alongside other fiber- and network-forming proteins such as fibronectin and elastin (Karamanos et al., 2021). This assembly is supported by accessory factors like the proteoglycans (Couchman and Pataki, 2012), a diverse set of proteins characterized by the presence of at least one glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chain that helps to promote tissue hydration and sequester signaling molecules (Gandhi and Mancera, 2008). Meanwhile, ECM turnover is regulated by secreted proteases (Arpino et al., 2015; Lee and Murphy, 2004).

All newly synthesized ECM proteins must transit the secretory pathway to reach the extracellular environment for assembly. As they do so, many are heavily modified, which alters their chemistry and consequently the way in which they interact and assemble (Adams, 2023). Regulation of ECM protein modification is therefore crucial to the assembly of a functional matrix. One of the main compartments responsible for facilitating this process is the Golgi apparatus, which contains enzymes catalyzing modifications such as O-glycosylation, N- and O-linked glycan maturation, proteolytic processing, phosphorylation, lipidation, and sulfation (Potelle et al., 2015). Given this central role in protein processing, it is unsurprising that a large number of genes affecting Golgi function have been linked to various connective tissue disorders (Hellicar et al., 2022).

Golgi structure is highly complex and tightly linked to its function. In mammalian systems, it is composed of a stack of flattened, fenestrated membranous compartments called cisternae, which are laterally connected to form an interconnected Golgi ribbon (Lowe, 2011). These stacks are polarized such that cargoes arriving from the ER enter the Golgi stack at the cis-face, transit through the medial- and trans-compartments, and then get sorted before exiting the Golgi at the trans-Golgi network (TGN). Golgi-resident enzymes are distributed across the cisternae with a cis-trans polarity to support the successive addition of post-translational modifications to cargoes as they transit the compartments (Rabouille et al., 1995; Tie et al., 2022). This distribution is maintained by intra-Golgi vesicular transport, which recycles enzymes between Golgi cisternae (Arab et al., 2024).

One of the major protein families responsible for maintaining Golgi organization is the golgin family (Barr and Short, 2003; Gillingham and Munro, 2016; Witkos and Lowe, 2015). These proteins project coiled-coil domains into the cytosol from the Golgi surface to tether other Golgi membranes and transport vesicles (Lowe, 2019; Wong and Munro, 2014). Specific golgins localize to distinct regions of the Golgi organelle, and this, combined with their affinity for different vesicles, confers directionality and specificity to intra-Golgi traffic (Wong et al., 2017). We and others have shown that one of these golgins, giantin, is required for the secretion of a healthy ECM. Loss of giantin prevents proper processing of the procollagen type I N-propeptide (Stevenson et al., 2021), impacts the abundance of ECM proteins (Katayama et al., 2018; Kikukawa and Suzuki, 1992), and impairs GAG metabolism (Kikukawa et al., 1991a; Kikukawa et al., 1991b; Kikukawa et al., 1990). These phenotypes are variable between animal models, but, interestingly, always impact skeletal development (Katayama et al., 2011; Lan et al., 2016; Stevenson et al., 2017; Suzuki et al., 1988).

Another golgin that has been linked to ECM deposition and skeletal development is GMAP210. Mutations in the TRIP11 gene encoding GMAP210 are causative of the human skeletal diseases achondrogenesis type 1A and odontochondrodysplasia (Costantini et al., 2021; Del Pino et al., 2021; Medina et al., 2020; Qian et al., 2021; Smits et al., 2010; Upadhyai et al., 2021; Wehrle et al., 2019; Yeter et al., 2022). Interestingly, Trip11 mutant mice have a similar phenotype to giantin mutant rats, with both models showing neonatal lethal chondrodysplasia characterized by craniofacial defects, shortened limbs and ribs, and delayed mineralization of bone (Bird et al., 2018; Follit et al., 2008; Smits et al., 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2021). Loss of GMAP210 also impacts the secretion of specific ECM proteins in a selective manner (Bird et al., 2018; Smits et al., 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2021).

Altogether, these studies suggest that ECM secretion is particularly susceptible to the loss of at least two golgins, which appear to act nonredundantly in this context. This led us to question the extent to which ECM deposition is sensitive to the loss of golgins more widely, and how this relates to changes in Golgi organization. To begin addressing this, we performed a comparative study between GMAP210 and a third golgin, Golgin-160. Golgin-160 was chosen because it resides on cis-Golgi membranes like GMAP210 (Hicks et al., 2006) but remains poorly characterized at a functional level. Here, we report that knockout (KO) of Golgin-160 has a similar impact on ECM organization as GMAP210 loss. Golgi morphology, on the other hand, is affected differently, consistent with the two golgins acting in different ways to maintain Golgi homeostasis. We therefore conclude that GMAP210 and Golgin-160 function non-redundantly to create the correct physical and biochemical space to support the modification and secretion of complex ECM molecules.

Results

Generation of golgin KO cell lines

To test the role of different golgins on matrix secretion, we generated two GMAP210 and Golgin-160 KO clones using CRISPR/Cas9 genome engineering in human retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE1). GMAP210 KO clone 1 was generated using a gRNA targeting exon 4 of the TRIP11 gene (Fig. S1 A). This exon is common to both predicted protein-coding transcripts TRIP11-201 (Ensembl transcript ID ENST00000267622.8, UniProt ID Q15643-1) and TRIP11-202 (ENST00000554357.5, H0YJ97), and so mutation should impact all protein expression. The generated mutation was a single base pair insertion of alanine resulting in a frameshift from position Glu114 and truncation at amino acid 155 (Fig. S1 A). GMAP210 KO clone 2 was generated using a gRNA targeting exon 1 of transcript TRIP11-202 and upstream of the predicted start site of the longer transcript TRIP11-201. This resulted in a 10-bp deletion in the promoter region (Fig. S1 A). Loss of protein expression was confirmed in both clones by immunofluorescence using three different antibodies targeting the N and C terminus of the GMAP210 protein (Fig. S1 B) and western blotting (Fig. S1 C). Note trace amounts of protein could be detected with the C-terminal antibody, suggesting a truncation product may persist. Nonetheless, we considered this sufficient depletion for further study.

Generation of CRISPR/Cas9 mutant lines. (A) CRISPR design and resulting mutations in chosen KO clones. Top lines show gene sequence in WT and mutant (KO) clones with encoded amino acid sequence underneath. Purple lines indicate gRNA target sequence, scissors point to predicted Cas9 cut site, red letters in KO sequences indicate mutagenic base pair insertions, and purple letters in WT sequence indicate base pairs deleted in the mutant lines. Green amino acids are mutagenic changes arising after frameshift in KO lines, and * denotes a premature stop codon. (B) Maximum projection widefield images of WT and GMAP210 KO lines immunolabeled as indicated. GMAP210 antibodies were raised against amino acids 14–148 (N-term GMAP210), 159–365 (GMAP210), and 1760–1855 (C-term GMAP210). (C) Western blots of WT and GMAP210 KO cells probed with an antibody targeting amino acids 14–148 or GMAP210 (central well is an unsuccessful clone—X). (D) Maximum projection widefield images of WT and Golgin-160 KO clones labeled with GM130 (green, cis-Golgi) and Golgin-160 (magenta). (D) Western blot analysis of WT and Golgin-160 KO cell lysates probed with Golgin-160 antibodies and tubulin and GAPDH as loading controls. (D and E) Golgin-160 N-terminal and C-terminal antibodies raised against amino acids 1–350 and 1436–1498, respectively. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Generation of CRISPR/Cas9 mutant lines. (A) CRISPR design and resulting mutations in chosen KO clones. Top lines show gene sequence in WT and mutant (KO) clones with encoded amino acid sequence underneath. Purple lines indicate gRNA target sequence, scissors point to predicted Cas9 cut site, red letters in KO sequences indicate mutagenic base pair insertions, and purple letters in WT sequence indicate base pairs deleted in the mutant lines. Green amino acids are mutagenic changes arising after frameshift in KO lines, and * denotes a premature stop codon. (B) Maximum projection widefield images of WT and GMAP210 KO lines immunolabeled as indicated. GMAP210 antibodies were raised against amino acids 14–148 (N-term GMAP210), 159–365 (GMAP210), and 1760–1855 (C-term GMAP210). (C) Western blots of WT and GMAP210 KO cells probed with an antibody targeting amino acids 14–148 or GMAP210 (central well is an unsuccessful clone—X). (D) Maximum projection widefield images of WT and Golgin-160 KO clones labeled with GM130 (green, cis-Golgi) and Golgin-160 (magenta). (D) Western blot analysis of WT and Golgin-160 KO cell lysates probed with Golgin-160 antibodies and tubulin and GAPDH as loading controls. (D and E) Golgin-160 N-terminal and C-terminal antibodies raised against amino acids 1–350 and 1436–1498, respectively. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Golgin-160 KO clones were generated using a gRNA targeting exon 20 of transcript GOLGA3-201 (ensemble ID ENST00000204726.9, UniProt ID: Q08378-1). This is expected to mutate all predicted transcripts encoding fragments larger than 44 amino acids. Mutation with this gRNA consistently produced a single alanine insertion, resulting in frameshift at amino acid Glu1312 and truncation at amino acid 1331 (Fig. S1 A). Consequently, two clones with the same mutation were carried forward for experiments to rule out clonal effects. Protein loss was confirmed by immunofluorescence and western blotting, again with antibodies targeting both the N and C terminus (Fig. S1, D and E).

Loss of either GMAP210 or Golgin-160 causes changes in ECM assembly and organization

To investigate the requirement for GMAP210 and Golgin-160 in ECM secretion and assembly, we grew our new KO lines for a week in the presence of ascorbic acid to promote collagen secretion and visualized the cell-derived ECM by immunofluorescence labeling. Co-labeling of two major fibrillar ECM components, collagen type 1 and fibronectin, revealed an extensive network of highly aligned and organized extracellular fibrils in wild-type (WT) cell cultures, with cell nuclei stretching along the fibril axis (Fig. 1, A–D). In GMAP210 (Fig. 1, A and B) and Golgin-160 KO (Fig. 1, C and D) cell cultures on the other hand, fibrils were identifiable, but they were less well ordered, showing poor alignment and an increase in branching. To examine the structure of these fibrils more closely, the cell layer was extracted, and the remaining cell-derived matrix was imaged by high-speed atomic force microscopy (HS-AFM). Again, fibrils were less well organized in all golgin KO cultures (Fig. 1, E and F). They were also thinner; however, the periodicity of the collagen fibrils was largely unchanged, suggesting assembly of collagen trimers into fibrils is normal, but lateral interconnections between fibrils may be reduced.

ECM organization is altered in golgin mutant cultures. (A and C) Confocal maximum projection images of non-permeabilized WT, GMAP210 KO (A), and Golgin-160 KO (C) RPE1 cell cultures immunolabeled for extracellular collagen type I (green), fibronectin-1 (magenta), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Scale bars, 10 µm. (B and D) Quantification of fibril characteristics measured from images represented in A and C using the TWOMBLI ImageJ plug-in (see Materials and methods). Individual dots represent the mean of each biological replicate (n = 4), and bars represent the median of all experiments. (E) Decellularized ECM from WT, GMAP210 KO, and Golgin-160 KO cell cultures imaged by HS-AFM. Images are representative of 10 × 10 raster scans from biological replicates (n = 3). Scale bars, 10 µm. (F) TWOMBLI quantification of fibril characteristics measured from images represented in E. Individual dots are measurements from each tile in the raster scan, with each biological replicate color-coded (n = 4). Bars represent the median of all experiments. (B, D, and F) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality and then a nested one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to generate P values. ANOVA, analysis of variance.

ECM organization is altered in golgin mutant cultures. (A and C) Confocal maximum projection images of non-permeabilized WT, GMAP210 KO (A), and Golgin-160 KO (C) RPE1 cell cultures immunolabeled for extracellular collagen type I (green), fibronectin-1 (magenta), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Scale bars, 10 µm. (B and D) Quantification of fibril characteristics measured from images represented in A and C using the TWOMBLI ImageJ plug-in (see Materials and methods). Individual dots represent the mean of each biological replicate (n = 4), and bars represent the median of all experiments. (E) Decellularized ECM from WT, GMAP210 KO, and Golgin-160 KO cell cultures imaged by HS-AFM. Images are representative of 10 × 10 raster scans from biological replicates (n = 3). Scale bars, 10 µm. (F) TWOMBLI quantification of fibril characteristics measured from images represented in E. Individual dots are measurements from each tile in the raster scan, with each biological replicate color-coded (n = 4). Bars represent the median of all experiments. (B, D, and F) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality and then a nested one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to generate P values. ANOVA, analysis of variance.

The overall fluorescence intensity of collagen staining in the matrix appeared reduced in the KO cultures. We therefore determined the abundance of collagen type I in lysate and matrix fractions of cell cultures by immunoblotting against the Col1a1 chain. Col1a1 abundance in the lysate fractions of mutant cultures was comparable to that of WT lysates when normalized to total protein, suggesting expression is normal and collagen is not retained inside the cell (Fig. 2, A and C i). Col1a1 abundance was, however, reduced in the ECM fraction of all mutant lines when normalized against total cellular protein (Fig. 2, B and C ii), suggesting it is not being efficiently incorporated into the insoluble matrix. Collagen in the media was below the level of detection by this method.

Collagen deposition in the matrix is impaired in golgin mutant cells. (A) Immunoblot for Col1a1 and total protein stain after SDS-PAGE of medium (M) and lysate (L) samples taken from WT and golgin KO cultures. (B) Immunoblot for Col1a1 and total protein stain after SDS-PAGE of the cell-derived matrix extracted from WT and golgin mutant cultures. (C i and ii) Quantification of Col1a1 intensity normalized against total cellular protein for i lysate samples as represented in A and ii matrix samples as represented in B. Dots show individual experiment result (n = 3), and bars show the mean and standard deviation. Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality and then a nested one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to generate P values. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

Collagen deposition in the matrix is impaired in golgin mutant cells. (A) Immunoblot for Col1a1 and total protein stain after SDS-PAGE of medium (M) and lysate (L) samples taken from WT and golgin KO cultures. (B) Immunoblot for Col1a1 and total protein stain after SDS-PAGE of the cell-derived matrix extracted from WT and golgin mutant cultures. (C i and ii) Quantification of Col1a1 intensity normalized against total cellular protein for i lysate samples as represented in A and ii matrix samples as represented in B. Dots show individual experiment result (n = 3), and bars show the mean and standard deviation. Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality and then a nested one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to generate P values. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

ECM composition is altered following loss of GMAP210 and Golgin-160

To determine whether the observed changes in ECM organization in the golgin KO cultures reflect changes in ECM composition, the cell-derived matrix from WT and KO cultures was collected and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Principal component analysis showed distinction between the WT and Golgin-160 KO and between the KO matrix samples, but variation between repeats was high (Fig. S2 A). Results were filtered against the matrisome database (Shao et al., 2023) to indicate proteins specifically related to ECM structure and function. Overall, fewer proteins were significantly impacted by loss of Golgin-160 than of GMAP210; however, there was a great deal of overlap between the KO lines (Fig. 3). For example, laminin subunit γ 1 (LAMC1), laminin subunit α 5 (LAMA5), hemicentin-1 (HMCN1), latent transforming growth factor β binding protein 1 (LTBP1), and transforming growth factor β 2 (TGFB2) were significantly reduced in abundance in at least one Golgin-160 KO line, as well as the GMAP210 KOs (Fig. 3, A–C). Conversely, the abundance of fibrillins was increased in all KO lines (Fig. 3, A–C). Interestingly, lysyl oxidase like 1 (LOXL1), which was upregulated in the GMAP210 KO ECM, was downregulated in Golgin-160 KOs, and vice versa for procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 1 (PLOD1, Fig. 3, A–C). This hints at golgin-specific changes in the post-translational modification of collagen. Altogether, these data show that both GMAP210 and Golgin-160 are required for the deposition of a well-organized ECM. The similarity seen between ECM phenotypes in GMAP210 and Golgin-160 KO cells also demonstrates the non-redundant nature of these golgins in this context and the broad susceptibility of ECM cargoes to golgin loss.

Matrisome analysis in mutant cells. (A) Principal component analysis of the mass spectrometry experiment shown in Fig. 3. (B and C) The Col4a2 sequence was split into its structural features, and abundance of relevant peptides was averaged within each feature and plotted for each mutant. Total Col4a2 abundance was normalized across conditions to investigate peptide-level variation. N = 3. (D) Western blots of medium (M) and lysate (L) fractions from WT and Golgin-160 KO cell cultures stably expressing pro-SBP-GFP-COL1A1. Blots probed with the LF39 antibody targeting the N-terminal propeptide domain of procollagen type I and GAPDH as a housekeeping protein. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

Matrisome analysis in mutant cells. (A) Principal component analysis of the mass spectrometry experiment shown in Fig. 3. (B and C) The Col4a2 sequence was split into its structural features, and abundance of relevant peptides was averaged within each feature and plotted for each mutant. Total Col4a2 abundance was normalized across conditions to investigate peptide-level variation. N = 3. (D) Western blots of medium (M) and lysate (L) fractions from WT and Golgin-160 KO cell cultures stably expressing pro-SBP-GFP-COL1A1. Blots probed with the LF39 antibody targeting the N-terminal propeptide domain of procollagen type I and GAPDH as a housekeeping protein. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

ECM composition is altered in golgin KO cells. (A and B) Volcano plots showing log-fold change in cell-derived matrix protein abundance from GMAP210 KO (A) or Golgin-160 KO (B) cells compared with WT. Red-labeled points represent proteins with significantly changing abundance, with the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR-corrected P values <0.05, n = 3. Only proteins categorized as matrisome are represented on these plots (Shao et al., 2023). (i and ii) Results for two different clones per gene are shown. (C) Heat map comparing protein abundance changes between the two different golgin KOs after pooling both clones. Red and blue indicate increased and decreased abundance respectively. Color intensity is determined by the average log-fold change across mutants compared with WT.

ECM composition is altered in golgin KO cells. (A and B) Volcano plots showing log-fold change in cell-derived matrix protein abundance from GMAP210 KO (A) or Golgin-160 KO (B) cells compared with WT. Red-labeled points represent proteins with significantly changing abundance, with the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR-corrected P values <0.05, n = 3. Only proteins categorized as matrisome are represented on these plots (Shao et al., 2023). (i and ii) Results for two different clones per gene are shown. (C) Heat map comparing protein abundance changes between the two different golgin KOs after pooling both clones. Red and blue indicate increased and decreased abundance respectively. Color intensity is determined by the average log-fold change across mutants compared with WT.

GMAP210 and Golgin-160 are not required for procollagen processing

We have shown previously that KO of giantin disrupts procollagen processing (Stevenson et al., 2021). To test whether impaired collagen processing is contributing to the ECM phenotypes reported here too, we interrogated our ECM proteomics data set for peptides relating to collagen prodomains. Collagen type IV had the highest peptide count and therefore provided the most robust analysis. Comparing the average peptide counts across the Col4a2 sequence, we found no significant increase in the number of peptides containing an intact N-propeptide cleavage site in the KO cultures (N-propeptide overlap sequence, Fig. S2, B and C), indicating that processing of collagen type IV proceeds effectively in the absence of Golgin-160 and GMAP210. The expression of a procollagen type 1 construct in which the N-propeptide is GFP-tagged (McCaughey et al., 2019) also revealed the presence of free collagen type I N-propeptide cleavage products in both WT and Golgin-160 KO cells indicating successful cleavage (Fig. S2 D). GMAP210 KO cells did not tolerate procollagen type I overexpression and could not be tested. Altogether, these data indicate that loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160 does not phenocopy loss of giantin with respect to collagen processing and that this is not a contributing factor to the observed ECM phenotypes here.

Loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160 leads to distinct changes in Golgi morphology

Having established that loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160 has a similar impact on ECM deposition, we next sought to determine the impact of golgin loss on Golgi organization. Cells were labeled with markers of the cis- and medial-Golgi and the TGN. Golgi area and extent of fragmentation were then measured (Fig. 4, A–D). Strikingly, each golgin KO had a different impact on Golgi morphology. As previously reported (Bird et al., 2018; Sato et al., 2015; Smits et al., 2010; Wehrle et al., 2019; Yamaguchi et al., 2022), loss of GMAP210 resulted in a clear compaction of Golgi structures compared with WT cells (Fig. 4, A and B). The Golgi also appeared fragmented, although this was difficult to quantify due to the compaction and poor definition of Golgi elements. In Golgin-160 KO cells on the other hand, no consistent change in Golgi size was observed, but there was a clear increase in Golgi fragment number (Fig. 4, C and D). In all KO lines, the cis-trans polarity of the Golgi appeared to be maintained, although again this was harder to ascertain in the GMAP210 KO cells (Fig. 4, A and C). These phenotypes were also confirmed in a second cell line, mouse MC3T3-E1, by CRISPR/Cas9 transfection and immunostaining of GM130 to label the Golgi, and Golgin-160 or GMAP210 to identify KO cells (Fig. S3 A).

Golgi organization is altered upon loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160. (A and C) Maximum projection confocal images of WT and GMAP210 KO (A) and Golgin-160 KO (C) RPE1 cells immunolabeled for cis-Golgi (GM130, magenta), cis/medial-Golgi (giantin, green), and TGN (TGN46, blue) markers. Nuclei labeled with DAPI (grayscale). Scale bar, 10 µm. Inset scale bar, 1 µm. (B and D) Quantification of total giantin and TGN46 area and fragment number per cell from images represented in A and C. Individual dots represent one cell and are colored by replicate (n = 3). Bars show the median from each replicate experiment. Statistical analysis was performed using a Shapiro–Wilk normality test and a Kruskal–Wallis significance test. (E–G) Tomographic reconstructions of Golgi structures in WT (E), GMAP210 KO (F), and Golgin-160 KO (G) cells. Segmented membranes are labeled as cisternae (blue/purple), dilated structures (red), tubulovesicular structures (yellow), and vesicles (green). (E ii, F ii, iii, and G ii iii) Single-slice images with segmentation. (F ii and iii) Open arrows point to invaginations within spherical regions of tubulovesicular structures. (G ii and iii) Double-headed arrows indicate top-to-bottom fenestrations in cisternae, closed-headed arrows indicate budding structures at the nuclear envelope, and pink arrow shows frustrated budding/fusion intermediate. (E i, iii, iv, F i, iv, v, and G i, iv, v) 3D rendering of segmentation. (E–G i) Scale bar, 1 µm.

Golgi organization is altered upon loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160. (A and C) Maximum projection confocal images of WT and GMAP210 KO (A) and Golgin-160 KO (C) RPE1 cells immunolabeled for cis-Golgi (GM130, magenta), cis/medial-Golgi (giantin, green), and TGN (TGN46, blue) markers. Nuclei labeled with DAPI (grayscale). Scale bar, 10 µm. Inset scale bar, 1 µm. (B and D) Quantification of total giantin and TGN46 area and fragment number per cell from images represented in A and C. Individual dots represent one cell and are colored by replicate (n = 3). Bars show the median from each replicate experiment. Statistical analysis was performed using a Shapiro–Wilk normality test and a Kruskal–Wallis significance test. (E–G) Tomographic reconstructions of Golgi structures in WT (E), GMAP210 KO (F), and Golgin-160 KO (G) cells. Segmented membranes are labeled as cisternae (blue/purple), dilated structures (red), tubulovesicular structures (yellow), and vesicles (green). (E ii, F ii, iii, and G ii iii) Single-slice images with segmentation. (F ii and iii) Open arrows point to invaginations within spherical regions of tubulovesicular structures. (G ii and iii) Double-headed arrows indicate top-to-bottom fenestrations in cisternae, closed-headed arrows indicate budding structures at the nuclear envelope, and pink arrow shows frustrated budding/fusion intermediate. (E i, iii, iv, F i, iv, v, and G i, iv, v) 3D rendering of segmentation. (E–G i) Scale bar, 1 µm.

Early secretory pathway organization in golgin mutants. (A) Widefield images of MC3T3 cells transfected with Cas9 and gRNA targeting either Trip11 or Golga3 genes and stained for GMAP210 (Trip11) or Golgin-160 (Golga3) to identify KO cells (as indicated by an asterisk) and GM130. Inserts show GM130 label in a WT and a KO cell from a mixed population. Scale bar, 10 µM. (B and C) Confocal maximum projection images of WT and golgin KO cell lines stained for cis/medial-Golgi membrane (giantin, magenta) markers and either ERGIC (ERGIC53, green) (A) or COP1 (βCOP, green) structures (B). Scale bars, 10 µM.

Early secretory pathway organization in golgin mutants. (A) Widefield images of MC3T3 cells transfected with Cas9 and gRNA targeting either Trip11 or Golga3 genes and stained for GMAP210 (Trip11) or Golgin-160 (Golga3) to identify KO cells (as indicated by an asterisk) and GM130. Inserts show GM130 label in a WT and a KO cell from a mixed population. Scale bar, 10 µM. (B and C) Confocal maximum projection images of WT and golgin KO cell lines stained for cis/medial-Golgi membrane (giantin, magenta) markers and either ERGIC (ERGIC53, green) (A) or COP1 (βCOP, green) structures (B). Scale bars, 10 µM.

To better define the impact of KO on Golgi membrane organization, higher resolution imaging was performed using single-tilt electron tomography. For each cell line, 3D tomographic reconstructions were generated (Videos 1, 2, and 3) and a section of the Golgi was segmented to build a 3D model of membrane organization (Videos 1, 2, and 3; and Fig. 4, E–G). In these models, membranes associated with the Golgi apparatus were grouped into four structural categories: cisternae (blue), defined as laterally flattened, stacked membranous compartments; dilated structures (red)—large volume structures lacking flattened regions; tubulovesicular structures (yellow)—convoluted structures with interconnected regions of spherical and tubular shape; and vesicles (green)—small, spherical structures.

Golgi reconstruction and segmentation in WT cell. Electron tomographic reconstruction of a 250-nm section through a WT cell showing an organized interconnected Golgi ribbon. Segmentation of a section of this ribbon shows cisternal membranes (labeled in blue/purple), dilated structures at the TGN (red), tubulovesicular structures (yellow), and vesicles (green). The movie shows slices running top–bottom–top through the section, then top to bottom adding the segmentation, followed by a zoom and rotational views of the 3D segmented structures. The movie runs at 40 frames per second and is also represented in Fig. 4. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Golgi reconstruction and segmentation in WT cell. Electron tomographic reconstruction of a 250-nm section through a WT cell showing an organized interconnected Golgi ribbon. Segmentation of a section of this ribbon shows cisternal membranes (labeled in blue/purple), dilated structures at the TGN (red), tubulovesicular structures (yellow), and vesicles (green). The movie shows slices running top–bottom–top through the section, then top to bottom adding the segmentation, followed by a zoom and rotational views of the 3D segmented structures. The movie runs at 40 frames per second and is also represented in Fig. 4. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Golgi reconstruction and segmentation in GMAP210 KO2 cell. Electron tomographic reconstruction of a 250-nm section through a GMAP210 KO2 cell showing scattered and dilated Golgi structures. Segmentation of two closely apposed Golgi stacks shows cisternal membranes (labeled in blue/purple), dilated structures (red), tubulovesicular structures (yellow), and vesicles (green). The movie shows slices running top–bottom–top through the section, then top to bottom adding the segmentation, followed by a zoom and rotational views of the 3D segmented structures. The movie runs at 40 frames per second and is also represented in Fig. 4 F. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Golgi reconstruction and segmentation in GMAP210 KO2 cell. Electron tomographic reconstruction of a 250-nm section through a GMAP210 KO2 cell showing scattered and dilated Golgi structures. Segmentation of two closely apposed Golgi stacks shows cisternal membranes (labeled in blue/purple), dilated structures (red), tubulovesicular structures (yellow), and vesicles (green). The movie shows slices running top–bottom–top through the section, then top to bottom adding the segmentation, followed by a zoom and rotational views of the 3D segmented structures. The movie runs at 40 frames per second and is also represented in Fig. 4 F. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Golgi reconstruction and segmentation in the Golgin-160 KO2 cell. Electron tomographic reconstruction of a 250-nm section through a Golgin-160 KO2 cell showing a fragmented Golgi, with stacks surrounded by vesicles. Segmentation of one stack shows cisternal membranes (labeled in blue/purple), dilated structures at the TGN (red), tubulovesicular structures (yellow), and vesicles (green). The movie shows slices running top–bottom–top through the section, then top to bottom adding the segmentation, then a zoom and rotational views of the 3D segmented structures. The movie runs at 40 frames per second and is also represented in Fig. 4 G. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Golgi reconstruction and segmentation in the Golgin-160 KO2 cell. Electron tomographic reconstruction of a 250-nm section through a Golgin-160 KO2 cell showing a fragmented Golgi, with stacks surrounded by vesicles. Segmentation of one stack shows cisternal membranes (labeled in blue/purple), dilated structures at the TGN (red), tubulovesicular structures (yellow), and vesicles (green). The movie shows slices running top–bottom–top through the section, then top to bottom adding the segmentation, then a zoom and rotational views of the 3D segmented structures. The movie runs at 40 frames per second and is also represented in Fig. 4 G. Scale bar, 500 nm.

In WT cells, as expected, we observed tightly stacked, evenly flattened, fenestrated cisternae that were laterally connected to span lengths of tens of microns (Fig. 4 E). Dilated and tubulovesicular structures were predominantly localized to the trans-side of the Golgi in these cells, with small numbers of vesicles concentrated at the cisternal rims and trans-Golgi face. In contrast, although the Golgi was identifiable in GMAP210 KO cells, membranes were highly disordered (Fig. 4 F). The cisternae were mostly stacked, but they were short with no lateral connections and few fenestrations, and many were dilated or had bulges along their length, particularly at the cis- and trans-end of the stack. Some membranous structures resembling these dilated cisternae were also observed near, but not part of, a stack, but their origin and identity are hard to assign. Finally, in many instances the cisternae were surrounded by extensive tubulovesicular structures interspersed with vesicles that wrapped around the mini-stacks (Fig. 4, F iii and iv). Some of these structures had tunnel-like indentations, which in cross section appeared as internalized vesicles but were continuous with the cytosol (Fig. 4, F ii and iii, open-headed arrows). Note that we did not see any obvious ER swelling as has been reported to occur in a cell type–specific manner in some in vivo studies (Bird et al., 2018; Smits et al., 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2021). Despite the similarity of the tubulovesicular membranes to ERGIC membranes (Appenzeller-Herzog and Hauri, 2006), we did not see any gross changes to ERGIC53 distribution in these cells at the light level (Fig. S3 B). To conclude, the geometry and organization of the Golgi membrane are severely perturbed in the absence of GMAP210 in a way that is suggestive of both structural and trafficking defects.

Examination of Golgin-160 KO cells showed well-stacked, tightly flattened cisternae that remained juxtanuclear as in WT cells (Fig. 4 G). However, consistent with the immunofluorescence data, there were very few lateral connections between cisternae meaning membranes were fragmented into closely apposed mini-stacks rather than forming a classical ribbon architecture (Fig. 4, G i, pink brackets). Cisternae also appeared to have internal vesicles or holes unlike control cells (Fig. 4, G ii, double-headed arrows). Strikingly, there was a clear accumulation of vesicular structures in the area surrounding the cisternal rims, as well as both the cis- and trans-Golgi face (Fig. 4, G v). This coincided with a high incidence of spherical structures attached to the membranes of cisternal rims that resembled frustrated vesicle budding or fusion profiles (Fig. 4, G ii, pink arrow). Intriguingly, budding vesicles were also frequently observed at the nuclear envelope (Fig. 4, G iii, closed-headed arrows). Although the accumulating vesicles were reminiscent of COPI vesicles with an electron-dense coat, we were unable to observe any gross changes in COPI localization at the light level by immunofluorescence as individual puncta could not be distinguished in the Golgi region (Fig. S3 C). In conclusion, loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160 has a different impact on Golgi structural organization.

Loss of either GMAP210 or Golgin-160 leads to reduced secretion of ECM components and regulators

Given the clear disruption to Golgi organization in our KO lines, we decided to look at secretion more generally. Cells were grown in serum-free medium overnight, before collecting the media to analyze the abundance of soluble secreted proteins by mass spectrometry. Three independent replicate samples were collected for all WT and KO lines and analyzed simultaneously by 15-plex tandem mass tagging mass spectrometry. The sum of raw abundance revealed replicate one to have contained more protein, and thus, pairwise comparisons within replicates were chosen over averages (Fig. S4 A). Principal component analysis reiterated the need for paired analysis with PC1 and PC2 separating the samples by replicate; however, good separation was observed at PC3 and PC4 between WT, Golgin-160 KO, and GMAP210 KO lines, with individual clones clustering together for each KO. This indicates genotype is a key contributor to variance and highlights variation between secretomes in each line (Fig. S4 B). The two individual KO clones for each golgin were pooled using a linear regression model to increase statistical power. Log fold change in protein abundance was plotted against P value to identify proteins whose secretion is significantly altered in KO cultures compared with WT (Fig. 5 A).

Secretome analysis in mutant cells. (A) Log2 sum of raw peptide abundance in each proteomics replicate from the secretome analysis shown in Fig. 5. (B) Principal component analysis of the secretome data sets represented in Fig. 5. (C) Heat map comparing protein abundance changes between the two different golgin KOs in the secretome experiment. Red and blue indicate increased and decreased abundance, respectively, and intensity of color is determined by the average log fold change across mutants compared with WT.

Secretome analysis in mutant cells. (A) Log2 sum of raw peptide abundance in each proteomics replicate from the secretome analysis shown in Fig. 5. (B) Principal component analysis of the secretome data sets represented in Fig. 5. (C) Heat map comparing protein abundance changes between the two different golgin KOs in the secretome experiment. Red and blue indicate increased and decreased abundance, respectively, and intensity of color is determined by the average log fold change across mutants compared with WT.

General secretion is differentially impacted by loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160. (A) Volcano plots showing log-fold change in protein abundance in the media from KO versus WT cultures plotted against significance across three independent replicate experiments. The results from the two golgin KO clonal cell lines were pooled to increase power. Lines and dot colors on the graph are for P < 0.05 and >1 or less than −1 LogFC. Triangular points show hits, which pass an FDR-corrected P < 0.05. (i–iii) Structural ECM proteins (i), ECM regulators (ii), and other proteins of interest (iii) have been highlighted. Proteins significantly changed in the same way in both KO cultures are labeled in dark blue, while proteins impacted in a golgin-specific way are labeled in purple. The proteoglycan family is indicated by green text. (B–H) RT-PCR analysis of the gene expression of (B) BGN, (C) SPARC, (D) DCN, (E) ARHGDIB, (F) FAM20C, (G) PLOD1, and (H) THBS1. Expression levels normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene YWHAZ. Individual data points represent biological replicate experiments (n = 3–4). Bars show the mean and standard deviation.

General secretion is differentially impacted by loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160. (A) Volcano plots showing log-fold change in protein abundance in the media from KO versus WT cultures plotted against significance across three independent replicate experiments. The results from the two golgin KO clonal cell lines were pooled to increase power. Lines and dot colors on the graph are for P < 0.05 and >1 or less than −1 LogFC. Triangular points show hits, which pass an FDR-corrected P < 0.05. (i–iii) Structural ECM proteins (i), ECM regulators (ii), and other proteins of interest (iii) have been highlighted. Proteins significantly changed in the same way in both KO cultures are labeled in dark blue, while proteins impacted in a golgin-specific way are labeled in purple. The proteoglycan family is indicated by green text. (B–H) RT-PCR analysis of the gene expression of (B) BGN, (C) SPARC, (D) DCN, (E) ARHGDIB, (F) FAM20C, (G) PLOD1, and (H) THBS1. Expression levels normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene YWHAZ. Individual data points represent biological replicate experiments (n = 3–4). Bars show the mean and standard deviation.

In total, 482 proteins and 427 proteins showed altered raw abundance (P < 0.05) in the secretome of GMAP210 KO and Golgin-160 KO cultures, respectively, compared with WT cells (Fig. 5 A and Fig. S4 C). GO-term analysis revealed that the top 15 biological pathways affected in both golgin KO samples included collagen fibril and ECM organization, consistent with the ECM defects described above, as well as cell adhesion and migration (Table 1). Proteins involved in osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation were also impacted by golgin loss. This was not surprising for the GMAP210 KOs given the skeletal phenotypes reported in animal models and human disease (Bird et al., 2018; Costantini et al., 2021; Del Pino et al., 2021; Follit et al., 2008; Medina et al., 2020; Qian et al., 2021; Smits et al., 2010; Upadhyai et al., 2021; Wehrle et al., 2019; Yamaguchi et al., 2021), but intriguingly, a similar effect was seen following the loss of Golgin-160, which has not been reported to cause a skeletal phenotype in mice (Banu et al., 2002; Bentson et al., 2013). Pathways associated with proteolysis and signaling appeared to be impacted by the loss of Golgin-160 specifically (Table 1).

GO-term analysis of golgin secretome data

| Term . | Count . | Percent . | P value . | List total . | Fold enrichment . | Bonferroni . | Benjamini . | FDR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golgin-160 KO cell secretome GO-term analysis | ||||||||

| GO:0007155∼cell adhesion | 41 | 16.4 | 3.80E-19 | 244 | 5.76764391245265 | 8.70E-16 | 8.70E-16 | 8.39E-16 |

| GO:0030199∼collagen fibril organization | 17 | 6.8 | 1.52E-15 | 244 | 17.6098573557589 | 3.56E-12 | 1.75E-12 | 1.68E-12 |

| GO:0030335∼positive regulation of cell migration | 20 | 8 | 1.16E-09 | 244 | 5.97470375145821 | 2.66E-06 | 8.88E-07 | 8.55E-07 |

| GO:0030198∼extracellular matrix organization | 17 | 6.8 | 2.24E-09 | 244 | 7.13662640207075 | 5.13E-06 | 1.05E-06 | 1.01E-06 |

| GO:0016477∼cell migration | 20 | 8 | 2.29E-09 | 244 | 5.73829461021346 | 5.25E-06 | 1.05E-06 | 1.01E-06 |

| GO:0071711∼basement membrane organization | 7 | 2.8 | 2.25E-07 | 244 | 25.378912071535 | 5.15E-04 | 8.59E-05 | 8.27E-05 |

| GO:0007275∼multicellular organism development | 13 | 5.2 | 2.65E-07 | 244 | 7.20076275045537 | 6.07E-04 | 8.67E-05 | 8.36E-05 |

| GO:0006508∼proteolysis | 22 | 8.79999999999999 | 3.31E-07 | 244 | 3.83137661965781 | 7.58E-04 | 9.48E-05 | 9.14E-05 |

| GO:0002062∼chondrocyte differentiation | 9 | 3.59999999999999 | 4.46E-07 | 244 | 12.8189402810304 | 0.00102162810602268 | 1.14E-04 | 1.09E-04 |

| GO:0007179∼transforming growth factor beta receptor signaling pathway | 11 | 4.39999999999999 | 6.53E-07 | 244 | 8.51830335826834 | 0.00149669542098818 | 1.50E-04 | 1.44E-04 |

| GO:0006024∼glycosaminoglycan biosynthetic process | 8 | 3.2 | 1.12E-06 | 244 | 14.5022354694485 | 0.00256771715921932 | 2.34E-04 | 2.25E-04 |

| GO:0035987∼endodermal cell differentiation | 7 | 2.8 | 2.02E-06 | 244 | 18.0108408249603 | 0.00461716250691446 | 3.86E-04 | 3.72E-04 |

| GO:0030509∼BMP signaling pathway | 10 | 4 | 2.94E-06 | 244 | 8.3960310612597 | 0.0067130316586329 | 5.18E-04 | 4.99E-04 |

| GO:0051897∼positive regulation of protein kinase B signaling | 13 | 5.2 | 3.80E-06 | 244 | 5.60491803278688 | 0.00866714018326186 | 6.22E-04 | 5.99E-04 |

| GO:0043406∼positive regulation of MAP kinase activity | 9 | 3.59999999999999 | 5.27E-06 | 244 | 9.32286565893123 | 0.0120127981719709 | 8.06E-04 | 7.76E-04 |

| GMAP210 KO cell secretome GO-term analysis | ||||||||

| GO:0061644∼protein localization to CENP-A containing chromatin | 15 | 8.06451612903225 | 6.42E-26 | 182 | 89.1117216117216 | 1.07E-22 | 1.07E-22 | 1.05E-22 |

| GO:0006336∼DNA replication-independent nucleosome assembly | 16 | 8.60215053763441 | 2.93E-24 | 182 | 63.3683353683353 | 4.88E-21 | 1.63E-21 | 1.60E-21 |

| GO:0032200∼telomere organization | 16 | 8.60215053763441 | 2.93E-24 | 182 | 63.3683353683353 | 4.88E-21 | 1.63E-21 | 1.60E-21 |

| GO:0045653∼negative regulation of megakaryocyte differentiation | 14 | 7.5268817204301 | 1.83E-22 | 182 | 74.8538461538461 | 3.06E-19 | 7.65E-20 | 7.51E-20 |

| GO:0006335∼DNA replication–dependent nucleosome assembly | 14 | 7.5268817204301 | 7.41E-19 | 182 | 46.7836538461538 | 1.23E-15 | 2.47E-16 | 2.43E-16 |

| GO:0006352∼DNA-templated transcription, initiation | 14 | 7.5268817204301 | 3.47E-17 | 182 | 36.5140712945591 | 5.79E-14 | 9.65E-15 | 9.49E-15 |

| GO:0006334∼nucleosome assembly | 21 | 11.2903225806451 | 1.33E-16 | 182 | 13.132253711201 | 1.85E-13 | 3.18E-14 | 3.12E-14 |

| GO:0006325∼chromatin organization | 21 | 11.2903225806451 | 2.46E-11 | 182 | 6.95236961181233 | 4.10E-08 | 5.13E-09 | 5.04E-09 |

| GO:0030199∼collagen fibril organization | 12 | 6.4516129032258 | 1.30E-10 | 182 | 16.6650492364778 | 2.17E-07 | 2.41E-08 | 2.37E-08 |

| GO:0007155∼cell adhesion | 25 | 13.4408602150537 | 6.06E-10 | 182 | 4.71490590538209 | 1.01E-06 | 1.01E-07 | 9.93E-08 |

| GO:0030198∼extracellular matrix organization | 12 | 6.4516129032258 | 1.71E-06 | 182 | 6.75373048004626 | 0.00284157753649927 | 2.59E-04 | 2.54E-04 |

| GO:0001649∼osteoblast differentiation | 10 | 5.3763440860215 | 3.15E-06 | 182 | 8.3542239010989 | 0.00522986536351555 | 4.37E-04 | 4.29E-04 |

| GO:0001666∼response to hypoxia | 11 | 5.91397849462365 | 6.35E-06 | 182 | 6.64561991680635 | 0.0105323325939843 | 8.14E-04 | 8.00E-04 |

| GO:0016477∼cell migration | 13 | 6.98924731182795 | 1.19E-05 | 182 | 5.00051387461459 | 0.0196624232674336 | 0.00141844159265057 | 0.00139376564412815 |

| GO:0002062∼chondrocyte differentiation | 7 | 3.76344086021505 | 1.31E-05 | 182 | 13.3667582417582 | 0.0216774495503507 | 0.00146104753825159 | 0.00143563039451476 |

| GO:0030335∼positive regulation of cell migration | 12 | 6.4516129032258 | 4.21E-05 | 182 | 4.80602543523891 | 0.067714253052996 | 0.00430049819830498 | 0.00422568449239565 |

| Term . | Count . | Percent . | P value . | List total . | Fold enrichment . | Bonferroni . | Benjamini . | FDR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golgin-160 KO cell secretome GO-term analysis | ||||||||

| GO:0007155∼cell adhesion | 41 | 16.4 | 3.80E-19 | 244 | 5.76764391245265 | 8.70E-16 | 8.70E-16 | 8.39E-16 |

| GO:0030199∼collagen fibril organization | 17 | 6.8 | 1.52E-15 | 244 | 17.6098573557589 | 3.56E-12 | 1.75E-12 | 1.68E-12 |

| GO:0030335∼positive regulation of cell migration | 20 | 8 | 1.16E-09 | 244 | 5.97470375145821 | 2.66E-06 | 8.88E-07 | 8.55E-07 |

| GO:0030198∼extracellular matrix organization | 17 | 6.8 | 2.24E-09 | 244 | 7.13662640207075 | 5.13E-06 | 1.05E-06 | 1.01E-06 |

| GO:0016477∼cell migration | 20 | 8 | 2.29E-09 | 244 | 5.73829461021346 | 5.25E-06 | 1.05E-06 | 1.01E-06 |

| GO:0071711∼basement membrane organization | 7 | 2.8 | 2.25E-07 | 244 | 25.378912071535 | 5.15E-04 | 8.59E-05 | 8.27E-05 |

| GO:0007275∼multicellular organism development | 13 | 5.2 | 2.65E-07 | 244 | 7.20076275045537 | 6.07E-04 | 8.67E-05 | 8.36E-05 |

| GO:0006508∼proteolysis | 22 | 8.79999999999999 | 3.31E-07 | 244 | 3.83137661965781 | 7.58E-04 | 9.48E-05 | 9.14E-05 |

| GO:0002062∼chondrocyte differentiation | 9 | 3.59999999999999 | 4.46E-07 | 244 | 12.8189402810304 | 0.00102162810602268 | 1.14E-04 | 1.09E-04 |

| GO:0007179∼transforming growth factor beta receptor signaling pathway | 11 | 4.39999999999999 | 6.53E-07 | 244 | 8.51830335826834 | 0.00149669542098818 | 1.50E-04 | 1.44E-04 |

| GO:0006024∼glycosaminoglycan biosynthetic process | 8 | 3.2 | 1.12E-06 | 244 | 14.5022354694485 | 0.00256771715921932 | 2.34E-04 | 2.25E-04 |

| GO:0035987∼endodermal cell differentiation | 7 | 2.8 | 2.02E-06 | 244 | 18.0108408249603 | 0.00461716250691446 | 3.86E-04 | 3.72E-04 |

| GO:0030509∼BMP signaling pathway | 10 | 4 | 2.94E-06 | 244 | 8.3960310612597 | 0.0067130316586329 | 5.18E-04 | 4.99E-04 |

| GO:0051897∼positive regulation of protein kinase B signaling | 13 | 5.2 | 3.80E-06 | 244 | 5.60491803278688 | 0.00866714018326186 | 6.22E-04 | 5.99E-04 |

| GO:0043406∼positive regulation of MAP kinase activity | 9 | 3.59999999999999 | 5.27E-06 | 244 | 9.32286565893123 | 0.0120127981719709 | 8.06E-04 | 7.76E-04 |

| GMAP210 KO cell secretome GO-term analysis | ||||||||

| GO:0061644∼protein localization to CENP-A containing chromatin | 15 | 8.06451612903225 | 6.42E-26 | 182 | 89.1117216117216 | 1.07E-22 | 1.07E-22 | 1.05E-22 |

| GO:0006336∼DNA replication-independent nucleosome assembly | 16 | 8.60215053763441 | 2.93E-24 | 182 | 63.3683353683353 | 4.88E-21 | 1.63E-21 | 1.60E-21 |

| GO:0032200∼telomere organization | 16 | 8.60215053763441 | 2.93E-24 | 182 | 63.3683353683353 | 4.88E-21 | 1.63E-21 | 1.60E-21 |

| GO:0045653∼negative regulation of megakaryocyte differentiation | 14 | 7.5268817204301 | 1.83E-22 | 182 | 74.8538461538461 | 3.06E-19 | 7.65E-20 | 7.51E-20 |

| GO:0006335∼DNA replication–dependent nucleosome assembly | 14 | 7.5268817204301 | 7.41E-19 | 182 | 46.7836538461538 | 1.23E-15 | 2.47E-16 | 2.43E-16 |

| GO:0006352∼DNA-templated transcription, initiation | 14 | 7.5268817204301 | 3.47E-17 | 182 | 36.5140712945591 | 5.79E-14 | 9.65E-15 | 9.49E-15 |

| GO:0006334∼nucleosome assembly | 21 | 11.2903225806451 | 1.33E-16 | 182 | 13.132253711201 | 1.85E-13 | 3.18E-14 | 3.12E-14 |

| GO:0006325∼chromatin organization | 21 | 11.2903225806451 | 2.46E-11 | 182 | 6.95236961181233 | 4.10E-08 | 5.13E-09 | 5.04E-09 |

| GO:0030199∼collagen fibril organization | 12 | 6.4516129032258 | 1.30E-10 | 182 | 16.6650492364778 | 2.17E-07 | 2.41E-08 | 2.37E-08 |

| GO:0007155∼cell adhesion | 25 | 13.4408602150537 | 6.06E-10 | 182 | 4.71490590538209 | 1.01E-06 | 1.01E-07 | 9.93E-08 |

| GO:0030198∼extracellular matrix organization | 12 | 6.4516129032258 | 1.71E-06 | 182 | 6.75373048004626 | 0.00284157753649927 | 2.59E-04 | 2.54E-04 |

| GO:0001649∼osteoblast differentiation | 10 | 5.3763440860215 | 3.15E-06 | 182 | 8.3542239010989 | 0.00522986536351555 | 4.37E-04 | 4.29E-04 |

| GO:0001666∼response to hypoxia | 11 | 5.91397849462365 | 6.35E-06 | 182 | 6.64561991680635 | 0.0105323325939843 | 8.14E-04 | 8.00E-04 |

| GO:0016477∼cell migration | 13 | 6.98924731182795 | 1.19E-05 | 182 | 5.00051387461459 | 0.0196624232674336 | 0.00141844159265057 | 0.00139376564412815 |

| GO:0002062∼chondrocyte differentiation | 7 | 3.76344086021505 | 1.31E-05 | 182 | 13.3667582417582 | 0.0216774495503507 | 0.00146104753825159 | 0.00143563039451476 |

| GO:0030335∼positive regulation of cell migration | 12 | 6.4516129032258 | 4.21E-05 | 182 | 4.80602543523891 | 0.067714253052996 | 0.00430049819830498 | 0.00422568449239565 |

Proteins showing significantly altered abundance in KO cell conditioned media compared with WT conditioned media (P <0.01) were entered into the DAVID knowledgebase (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/) and analyzed against the biological pathway GO-BP-DIRECT list for gene ontology-term enrichment. The 15 GO terms showing the most significant enrichment, as determined by the P value, are presented here.

Examination of the individual proteins most heavily affected by loss of each golgin shows a clear depletion of ECM components and regulators in the media of both KO cultures, with a high degree of overlap between GMAP210 and Golgin-160 KOs (Fig. 5 A—proteins impacted in the same way by each KO circled blue; Fig. S4 C). For example, the protein family showing the greatest depletion in both mutant medium fractions were the proteoglycans (Fig. 5 A, circled green). Biglycan (BGN), decorin, and versican all showed reduced abundance in both KO samples, with aggrecan also depleted in the Golgin-160 KO and testican (SPOCK1) impacted in the GMAP210 KOs. This suggests the proteoglycans are particularly susceptible to Golgi dysfunction. Collagen types IV, V, and VI, fibronectin, and nidogen-2 also showed reduced abundance in the media from both KO lines compared with WT (Fig. 4 A). Similarly, the secretion of matrix-regulating enzymes such as FAM20C and PLOD2, as well as signaling molecules like TGFb, growth differentiation factor 6, and LTBP2, was significantly downregulated in both KOs. Surprisingly, the protein showing the greatest increase in secretion in both KO lines was the intracellular protein Rho GDP Dissociation Inhibitor Beta (ARHGDIB), indicating aberrant translocation to the extracellular space.

In addition to these similarities, we also observed many golgin-specific changes in this data set (Fig. 5 A—differentially impacted proteins circled in purple; Fig. S4 C). For instance, thrombospondin secretion is more greatly affected in GMAP210 KO cultures, while Golgin-160 KO cells fail to efficiently secrete numerous additional ECM proteins and regulators like laminins and TIMP metalloproteases. Several components of the complement system also showed reduced secretion in the Golgin-160 KO cell lines, implying this pathway may be impaired following Golgin-160 loss (Fig. 5, A ii and Fig. S4 C). Overall, most proteins impacted by Golgin-160 loss showed reduced rather than increased abundance in culture media. In GMAP210 KO cells on the other hand, there were a significant number of proteins showing increased secretion, although these tended not to be ECM components. Of note, several lysosomal enzymes were released from GMAP210 KO cells suggesting either poor sorting at the Golgi or increased lysosome secretion (Fig. 5, A ii and Fig. S4 C). In conclusion, although the secretion of a large subset of ECM proteins is broadly susceptible to loss of golgin function, there are also cargoes that show specificity with respect to their reliance on particular golgins.

Golgin KOs induce changes in gene expression for some secreted proteins

Changes in secreted protein abundance in cell culture medium could arise due to the altered gene expression of the cargoes or altered trafficking to the cell surface. To test the former, we performed RT-PCR to measure the expression of cargo proteins identified in the secretome analysis. The proteins showing the greatest negative and positive fold change in abundance in the media of the KO cells were BGN and ARHGDIB, respectively (Fig. 5 A). Consistent with this, we found that the expression of mRNA encoding each protein mirrored these changes, with BGN expression reduced and ARHGDIB expression increased in KO clones (Fig. 5, B and E). The expression of decorin mRNA, a protein closely related to BGN, was also reduced alongside secretion (Fig. 5 D). To determine whether gene expression correlated with secretion more widely, four more targets were tested by RT-PCR: THBS1, which is only affected in GMAP210 KO cells; PLOD1, which is only impacted by Golgin-160 loss; and SPARC and FAM20C, which show reduced secretion in both KO lines. The expression of FAM20C was reduced in all KO clones, in line with secretion (Fig. 5 F). However, SPARC and PLOD1 expression were not significantly altered in any of the KO lines (Fig. 5, C and G) and THBS1 expression was not consistently impacted (Fig. 5 H). Gene expression levels therefore do not fully predict secretion patterns for all targets, suggesting golgin loss can lead to changes to ECM secretion in different ways.

BGN trafficking is unaffected by golgin loss

We next wanted to determine the direct impact of our golgin mutations on cargo transport and modification. For this, we focused on BGN as the protein showing the greatest fold change in secretion in all lines. Stable cell lines were generated expressing a construct encoding BGN tagged with both mScarlet-i and a streptavidin-binding protein (SBP) to allow live imaging of exogenous BGN transport under the control of the RUSH trafficking system (Boncompain et al., 2021). In this system, tagged BGN is expressed alongside a streptavidin-tagged ER hook, which binds the SBP tag on the BGN and holds it in the ER. The addition of biotin prior to imaging is then used to outcompete this interaction and release BGN for anterograde trafficking. In these experiments, the ER hook (not fluorescently labeled) is transiently expressed on a bicistronic vector that also encodes BFP-tagged mannosidase II (ManII-BFP) to provide a Golgi marker.

In the absence of ER hook, stably expressed BGN-SBP-mSc was localized to both the ER and Golgi in all cell lines (Fig. S5). After transient transfection with the ER hook, successful anchoring of the tagged BGN was confirmed by localization of fluorescence to the ER at the steady state (Fig. 6, A i, B i, and C i; T 00:00). Upon the addition of biotin, BGN began to accumulate in cytoplasmic punctae, presumed to be ER exit sites, before moving toward the Golgi region in punctate carriers (Videos 4, 5, and 6; and Fig. 6, A ii, B ii, and C ii). Arrival at the Golgi region occurred ∼14 min after biotin addition in all cases (Fig. 6 D). Here, the BGN signal initially accumulated adjacent to the ManII-BFP–labeled structures, but then showed increasing colocalization with ManII-BFP as it progressed through the stack (Videos 4, 5, and 6; Fig. 6, A i, B i, and C i; and Fig. S5 B). Finally, ∼20 min after arrival at the Golgi, the emergence of post-Golgi carriers carrying BGN to the cell periphery was readily observed (Fig. 6, A iii, B iii, C iii, and E). Overall, transport kinetics were similar in all lines tested (Fig. 6, D and E), suggesting BGN secretion is unimpeded by loss of GMAP210 or Golgin-160, at least in an overexpression bulk transport system.

BGN-SBP-mSc localization in mutant cells. (A) Widefield maximum projections of cells stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (blue) and immunolabeled for the ERGIC (ERGIC53, green), cis/medial-Golgi (giantin, magenta), and TGN (TGN46, grayscale). Scale bar in main image, 10 µm; and insert, 1 µm. (B and C) Line-scan fluorescence intensity readings across Golgi elements measured at key time points in the RUSH assays shown in Figs. 6 and 7; and Videos 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. The region measured is shown in inset. Line traces show (B) BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta trace) or (C) SPARC-SBP-mSc accumulates adjacent to ManII-positive Golgi elements (green trace, middle column) and then colocalizes with ManII-BFP (right column). Fluorescence measurements are normalized to the maximal point of each trace to account for differential expression and photobleaching rates of each fluorescent protein. Arrows highlight peak for each protein. ManII, mannosidase II.

BGN-SBP-mSc localization in mutant cells. (A) Widefield maximum projections of cells stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (blue) and immunolabeled for the ERGIC (ERGIC53, green), cis/medial-Golgi (giantin, magenta), and TGN (TGN46, grayscale). Scale bar in main image, 10 µm; and insert, 1 µm. (B and C) Line-scan fluorescence intensity readings across Golgi elements measured at key time points in the RUSH assays shown in Figs. 6 and 7; and Videos 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. The region measured is shown in inset. Line traces show (B) BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta trace) or (C) SPARC-SBP-mSc accumulates adjacent to ManII-positive Golgi elements (green trace, middle column) and then colocalizes with ManII-BFP (right column). Fluorescence measurements are normalized to the maximal point of each trace to account for differential expression and photobleaching rates of each fluorescent protein. Arrows highlight peak for each protein. ManII, mannosidase II.

BGN can traffic efficiently in golgin KO cells. (A–C) BGN RUSH assay in WT (A), GMAP210 KO (B), and Golgin-160 KO (C) cells stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently transfected with an ER hook (not visible) and mannosidase II-BFP (green) prior to the experiment. Images are single-plane confocal images taken from time-lapse movies of BGN transport after release from the ER by biotin addition at T 00:00. Time after biotin addition is indicated in top left corner as mm:ss. (A i, B i, and C i) White arrows highlight the emergence of post-Golgi carriers. Scale bar, 10 µm. (A ii, B ii, and C ii) Crop showing incidence of ER–Golgi transport of BGN as highlighted by the arrow. Scale bar, 1 µm. (A iii, B iii, and C iii) Crop showing incidence of post-Golgi transport of BGN with carrier highlighted by the arrow. Scale bar, 1 µm. (D) Quantification of ER–Golgi transport, measured as time between biotin addition and the appearance of the BGN signal adjacent to mannosidase II-BFP label. (E) Quantification of Golgi transit time, measured as the time between BGN enrichment adjacent to mannosidase II-BFP signal and the emergence of a visible post-Golgi carrier. (D–E) All quantification performed on live movies as represented in A–C. Individual data points represent individual cells imaged across six independent experiments, and bars show the mean and standard deviation. (D) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (failed) and then a nested one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal–Wallis test. (E) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (passed) and then a nested one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to generate P values.

BGN can traffic efficiently in golgin KO cells. (A–C) BGN RUSH assay in WT (A), GMAP210 KO (B), and Golgin-160 KO (C) cells stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently transfected with an ER hook (not visible) and mannosidase II-BFP (green) prior to the experiment. Images are single-plane confocal images taken from time-lapse movies of BGN transport after release from the ER by biotin addition at T 00:00. Time after biotin addition is indicated in top left corner as mm:ss. (A i, B i, and C i) White arrows highlight the emergence of post-Golgi carriers. Scale bar, 10 µm. (A ii, B ii, and C ii) Crop showing incidence of ER–Golgi transport of BGN as highlighted by the arrow. Scale bar, 1 µm. (A iii, B iii, and C iii) Crop showing incidence of post-Golgi transport of BGN with carrier highlighted by the arrow. Scale bar, 1 µm. (D) Quantification of ER–Golgi transport, measured as time between biotin addition and the appearance of the BGN signal adjacent to mannosidase II-BFP label. (E) Quantification of Golgi transit time, measured as the time between BGN enrichment adjacent to mannosidase II-BFP signal and the emergence of a visible post-Golgi carrier. (D–E) All quantification performed on live movies as represented in A–C. Individual data points represent individual cells imaged across six independent experiments, and bars show the mean and standard deviation. (D) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (failed) and then a nested one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal–Wallis test. (E) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (passed) and then a nested one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to generate P values.

BGNRUSH in a WT cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a BGN RUSH assay in a WT cell. Cells are stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 15 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 6 A.

BGNRUSH in a WT cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a BGN RUSH assay in a WT cell. Cells are stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 15 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 6 A.

BGNRUSH in a GMAP210 KO2 cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a BGN RUSH assay in a GMAP210 KO2 cell. Cells are stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 15 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 6 B.

BGNRUSH in a GMAP210 KO2 cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a BGN RUSH assay in a GMAP210 KO2 cell. Cells are stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 15 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 6 B.

BGNRUSH in a Golgin-160 KO2 cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a BGN RUSH assay in a Golgin-160 KO2 cell. Cells are stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 10 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 6 C.

BGNRUSH in a Golgin-160 KO2 cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a BGN RUSH assay in a Golgin-160 KO2 cell. Cells are stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 10 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 6 C.

SPARC trafficking is altered in the absence of GMAP210 and Golgin-160

As BGN expression levels were reduced in KO cells, we also tested a second cargo, SPARC, whose secretion was significantly reduced in KO cultures without any corresponding change in mRNA expression. Stable cell lines expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc were made, and live-imaging RUSH assays were performed as for BGN. Interestingly, this time we observed clear changes in SPARC transport dynamics upon golgin loss (Fig. 7; and Videos 7, 8, and 9).

SPARC traffics through alternative pathways in golgin KO cells. (A–D) SPARC RUSH assay in WT (A), GMAP210 KO (B), and Golgin-160 KO (C) cells stably expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently transfected with an ER hook (not visible) and mannosidase II-BFP (green, outlined by white dashed line) prior to the experiment. Images are single confocal planes taken from time-lapse movies of SPARC transport after release from the ER by biotin addition at T 00:00. Time after biotin addition is indicated in the top left corner as mm:ss. White arrows indicate SPARC accumulation adjacent to the mannosidase II–positive membranes. Blue arrows highlight peripheral puncta that initiate vesicular ER–Golgi transport. Scale bars, 10 µm. (D i–iii) Quantification of (i) time to arrival at Golgi after biotin addition, (ii) Golgi transit time, measured as the time between SPARC enrichment adjacent to mannosidase II-BFP signal and the emergence of a visible post-Golgi carrier, and (iii) the number of cells in which post-Golgi carriers were identified within 45 min of imaging time, from movies represented in A–C. Individual data points represent individual cells imaged across four independent experiments, and bars show the mean and standard deviation. (i) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (failed) and then a nested one-way ANOVA with a Kruskal–Wallis test. (ii) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (passed) and then a nested one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (E) Maximum projection confocal stacks of SPARC-SBP-mSc stable cell lines transfected with GM130-GFP to mark the Golgi. Scale bar, 10 µm.

SPARC traffics through alternative pathways in golgin KO cells. (A–D) SPARC RUSH assay in WT (A), GMAP210 KO (B), and Golgin-160 KO (C) cells stably expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently transfected with an ER hook (not visible) and mannosidase II-BFP (green, outlined by white dashed line) prior to the experiment. Images are single confocal planes taken from time-lapse movies of SPARC transport after release from the ER by biotin addition at T 00:00. Time after biotin addition is indicated in the top left corner as mm:ss. White arrows indicate SPARC accumulation adjacent to the mannosidase II–positive membranes. Blue arrows highlight peripheral puncta that initiate vesicular ER–Golgi transport. Scale bars, 10 µm. (D i–iii) Quantification of (i) time to arrival at Golgi after biotin addition, (ii) Golgi transit time, measured as the time between SPARC enrichment adjacent to mannosidase II-BFP signal and the emergence of a visible post-Golgi carrier, and (iii) the number of cells in which post-Golgi carriers were identified within 45 min of imaging time, from movies represented in A–C. Individual data points represent individual cells imaged across four independent experiments, and bars show the mean and standard deviation. (i) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (failed) and then a nested one-way ANOVA with a Kruskal–Wallis test. (ii) Data were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (passed) and then a nested one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (E) Maximum projection confocal stacks of SPARC-SBP-mSc stable cell lines transfected with GM130-GFP to mark the Golgi. Scale bar, 10 µm.

SPARC RUSH in a WT cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a SPARC RUSH assay in a WT cell. Cells are stably expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 5 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 7 A.

SPARC RUSH in a WT cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a SPARC RUSH assay in a WT cell. Cells are stably expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 5 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 7 A.

SPARC RUSH in a GMAP210 KO2 cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a SPARC RUSH assay in a GMAP210 KO2 cell. Cells are stably expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 5 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 7 B.

SPARC RUSH in a GMAP210 KO2 cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a SPARC RUSH assay in a GMAP210 KO2 cell. Cells are stably expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 5 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 7 B.

SPARC RUSH in a Golgin-160 KO1 cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a SPARC RUSH assay in a Golgin-160 KO1 cell. Cells are stably expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 5 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 7 C.

SPARC RUSH in a Golgin-160 KO1 cell. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse movie of a SPARC RUSH assay in a Golgin-160 KO1 cell. Cells are stably expressing SPARC-SBP-mSc (magenta) and transiently expressing KDEL-streptavidin (unlabeled) and mannosidase II-BFP (green). The movie begins 5 min after 400 µM biotin addition (time after biotin addition is indicated in top left as mm:ss). One frame is taken every 500 ms. Images are single plane. The movie frame rate is 120 frames/s. Scale bar, 10 µm. The movie is also represented in Fig. 7 C.

In WT cells, upon biotin addition, SPARC appeared to accumulate in the Golgi without the appearance of discernible ER–Golgi carriers (Video 7, Fig. 7 A, and Fig. S5 C). This is consistent with the “short-loop” pathway of ER–Golgi transport taken by collagen type I and described by McCaughey et al. (2019). In KO cells, however, SPARC accumulated in highly dynamic peripheral puncta just prior to, or concurrent with, its enrichment at the Golgi. Many of these puncta either moved toward and fused with the Golgi themselves or budded smaller ER–Golgi carriers. Other puncta persisted as stable structures throughout the movie and were ManII-BFP–negative, suggesting they were not Golgi elements. Despite transporting via an alternative route, the overall kinetics of ER–Golgi transport was the same between WT and KO cells (Fig. 7 D).

With respect to the Golgi exit, post-Golgi carriers could only be identified in 30–50% of KO cells during 45 min of imaging, in contrast to 80% of WT cells (Fig. 7, D iii). This implies Golgi transit is delayed or impaired in approximately half of cells, consistent with the proteomics results. Indeed, the study of the steady-state localization of SPARC-SBP-mSc in the absence of a RUSH hook showed that Golgi transit defects are so severe in Golgin-160 KO cells that it accumulates in the Golgi (Fig. 7 E). Altogether, our RUSH assays demonstrate that golgin loss impacts different cargoes in distinct ways.

Post-translational modification of BGN is impaired in golgin KO cell lines

The interconnectivity of Golgi cisternae and their spatial organization is important to support and optimize the function of Golgi-resident enzymes that post-translationally modify cargoes (Zhang and Wang, 2016). ECM proteins are often highly modified, and these modifications are important to their assembly (Adams, 2023). We therefore sought to determine whether the disruption to Golgi organization in our mutants impacts ECM protein modification, which may in turn contribute to assembly defects. Proteoglycans are heavily modified by the addition of large, sulfated GAG chains, making them highly susceptible to Golgi dysfunction. We therefore continued to focus on BGN as a model cargo.

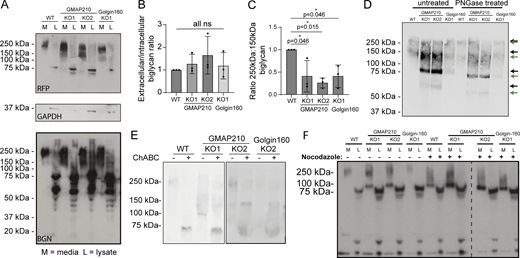

To look for changes in modification, cells stably expressing BGN-SBP-mSc were grown in serum-free medium overnight before collecting the media and lysate fractions of cultures for western blotting. Immunoblotting for both BGN and the mScarlet-i tag showed that exogenous BGN is secreted by all mutant lines (Fig. 8 A), consistent with the RUSH assays. Furthermore, the ratio of intracellular to extracellular protein was maintained, suggesting secretion rates are similar (Fig. 8 B). We did, however, notice a shift in the molecular weight distribution of secreted BGN in mutant cultures. In WT conditioned media, secreted BGN-SBP-mSc was identifiable as a broad band at around 250 kDa, with a small amount of protein running at 150 kDa. In all KO lines, however, a higher proportion of the protein ran at the lower molecular weight (Fig. 8 A). Calculation of the normalized ratio of 250- versus 150-kDa protein confirmed this observation (Fig. 8 C). Blotting with the higher affinity RFP antibody also showed the presence of fully unmodified BGN-SBP-mSc at 75 kDa in the medium fraction, which was again secreted to a greater extent by KO cells (Fig. 8 A). These data suggest BGN post-translational modification is perturbed in a similar way in the absence of either golgin.