ER-phagy is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis. However, significant gaps persist in our understanding of how ER-phagy and the ER network vary across cell subtypes, tissues, and organs. Furthermore, the pathophysiological relevance of ER-phagy remains poorly elucidated. Addressing these questions requires developing quantifiable methods to visualize ER-phagy and ER architecture in vivo. We generated two transgenic mouse lines expressing an ER lumen–targeting tandem RFP-GFP (ER-TRG) tag, either constitutively or conditionally. This approach enables precise spatiotemporal measurements of ER-phagy and ER structure at single-cell resolution in vivo. Systemic analysis across diverse organs, tissues, and primary cultures derived from these ER-phagy reporter mice unveiled significant variations in basal ER-phagy, both in vivo and ex vivo. Furthermore, our investigation uncovered substantial remodeling of ER-phagy and the ER network in different tissues under stressed conditions such as starvation, oncogenic transformation, and tissue injury. In summary, both reporter models represent valuable resources with broad applications in fundamental research and translational studies.

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the largest intracellular membrane system that is organized into tubular and sheet structures (Shibata et al., 2006; Zhang and Hu, 2016). Beyond its central role in protein and lipid synthesis, intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, and the biosynthesis of organelles either directly or indirectly (Joshi et al., 2017), the ER network also forms dynamic contact sites with different organelles and with the plasma membrane in orchestrating an intracellular organelle-interaction network, which is the foundation for a myriad of cellular processes (Lee et al., 2020a; Phillips and Voeltz, 2016; Wu et al., 2018).

The estimated half-lives of lipids and proteins within the ER membrane are ∼3–5 days (Omura et al., 1967). Furthermore, the ER has the remarkable ability to expand itself in response to various ER stresses, thereby mitigating the toxicity resulting from environmental insults (Walter and Ron, 2011). After stress, the elimination of excess ER membrane structures becomes imperative to prevent adverse side-effects. This turnover of the ER network is orchestrated through a selective autophagy pathway specifically targeting the ER, a process coined as ER-phagy (Bernales et al., 2006). Recent studies have provided crucial insights into how the autophagy machinery recognizes redundant or damaged ER structures for lysosomal degradation. Distinct ER-phagy receptors have been identified in different organisms, spanning yeasts, plants, and mammals (An et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2019; Chino et al., 2019; Fumagalli et al., 2016; Grumati et al., 2017; Honig et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2020; Khaminets et al., 2015; Michaeli et al., 2014; Mochida et al., 2015; Nthiga et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2017; Stefely et al., 2020; Stephani et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2018). Additionally, it has been reported that microautophagy, another lysosome-dependent pathway, may also play a role in removing redundant ER structures (Loi et al., 2019).

The malfunction of ER-phagy has direct implications for various human diseases (Ferro-Novick et al., 2021; Foronda et al., 2023; González et al., 2023; He et al., 2021; Hübner and Dikic, 2020; Reggiori and Molinari, 2022). Despite this critical link, the absence of convenient tools for assessing in vivo ER-phagy has hindered in-depth investigations into the role of ER-phagy in pathophysiological states.

Design

Current methods for measuring ER turnover in cultured mammalian cells include the following:

- (1)

Electron microscopy: Traditional electron microscopy allows for the visualization of the sequestration of ER fragments by autophagic vacuoles. However, the protocol is tedious, and quantification poses a challenge. Importantly, this method is not well-suited for the analysis of large-sized samples, such as tissues or organs from mammals.

- (2)

Biochemical quantification of ER-phagy: Relying extensively on immuno-blotting to assess the rate of ER protein turnover, this method is generally reliable and semi-quantitative. However, it lacks the spatial resolution required for evaluating ER degradation flux at the levels of cells, tissues, and organs.

- (3)

Measuring the size of the ER network: ER expansion and distribution can be monitored using fluorescent protein-illuminated ER structures or by immunostaining a ubiquitous ER protein. However, variations in quantification results may arise due to imaging parameters and the quality of antibodies employed.

- (4)

Colocalization analysis of the ER marker with autolysosomes, autophagosomes, or lysosomes: While this method is reliable for evaluating ER-phagy flux in cultured cells, it is often incompatible with samples from tissues or organs. Issues such as epitope accessibility and antibody quality pose challenges in extending its application beyond cultured cells.

- (5)

Ratiometric fluorescence probes: Previous ER-phagy studies have employed both tandem fluorescent protein (FP)- and Keima-based reporters, such as GFP-mCherry-RAMP4 (Liang et al., 2018), RAMP4-Keima (An et al., 2019), ssRFP-GFP-KDEL (Chino et al., 2019), and mCherry-GFP-REEP5 (Chen et al., 2019). These assays hinge on the expression of different reporters either in the ER lumen or in the ER membrane. When Keima serves as the reporter, the ER network exhibits an excitation wavelength centered at 440 nm under neutral pH; however, upon ER-phagy, ER membrane fragments are transported to the acidic lysosomal environment, leading to a shift in Keima’s excitation wavelength to 586 nm. In the case of GFP-RFP/mCherry, the ER is dual-labeled in green and red. During ER-phagy, the RFP or mCherry fluorescence of the ER fragment remains stable in the acidic autolysosomal lumen, while GFP fluorescence is quenched. In either scenario, the appearance of red-only foci provides an easily quantifiable index of ER-phagy.

In addition to measuring ER-phagy, Keima has been successfully employed to study mitophagy both in vitro (Bingol et al., 2014; Katayama et al., 2011) and in vivo (Sun et al., 2015). However, Keima is an FP that possesses reversible acid sensitivity and is therefore relatively incompatible with fixed and tissue samples (Sun et al., 2017). Given the anticipated extensive use of fixed samples in visualizing in vivo ER-phagy in this study, we sought a dual fluorescent protein-based reporter, known for its greater reliability in fixed samples. Such dual fluorescence-based probes have been widely utilized to measure both bulk and selective autophagy flux (Allen et al., 2013; Bhutia et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2019; Chino et al., 2019; Delorme-Axford et al., 2019; Kaizuka et al., 2016; Katayama et al., 2011, 2020; Kimura et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2019, 2022; Liang et al., 2018; Pankiv et al., 2007; Takayama et al., 2017; Yoshii and Mizushima, 2017).

It would be ideal to develop in vivo tools for assessing the architecture and autophagic flux of different ER subdomains. In theory, mCherry-GFP-RAMP4 and mCherry-GFP-REEP5 can gauge the autophagic flux of distinct ER subdomains, considering that endogenous RAMP4 and REEP5 localize to sheet and tubular ER, respectively (Chino and Mizushima, 2020). However, uncertainties persist regarding whether overexpressed RAMP4 or REEP5 can precisely target the reporters to the ER network and whether their overexpression may influence ER structure and functionality in vivo. Additionally, it is widely accepted that a reporter expressed in the ER lumen using the KDEL-tagging strategy can measure bulk ER-phagy due to its ubiquitous distribution in the ER network (Chino et al., 2019).

While overexpression of a tandem FP in the ER lumen as a reliable ER-phagy reporter seems safe in vitro (Chino et al., 2019), its efficacy for faithfully visualizing in vivo ER-phagy and ER architecture without adverse side-effects remains uncertain. Considering these concerns, we opted for a complementary strategy, creating a pair of knock-in transgenic mouse lines expressing an ER-targeting tandem RFP-GFP tag either constitutively or conditionally under the Cre recombinase control. We anticipate that constitutive reporter expression will facilitate convenient and systemic visualization of in vivo ER-phagy and ER architecture. Simultaneously, the Cre recombinase-activated expression of the reporter is expected to offer precise spatiotemporal measurement of in vivo ER-phagy without inducing deleterious side-effects.

Results

Generating ER-phagy reporter mice

Our primary objective was to establish three distinct animal models capable of measuring in vivo sheet, tubular, or bulk ER-phagy, respectively. Recognizing Keima’s limitations for assessing autophagic flux in animals (Mizushima and Murphy, 2020; Sun et al., 2017), we explored dual-fluorescence reporters compatible with fixed samples. However, when RFP-GFP-RAMP4 or RFP-GFP-REEP5 was overexpressed in cell cultures, we observed their ability to label both sheet and tubular ER, similar to ssRFP-GFP-KDEL (Fig. S1, A and B). This suggested that overexpression led to the diffusive distribution of RAMP4 and REEP5 throughout the entire ER membrane system, weakening their specific localization. To avoid labeling artifacts from overexpression, we chose to knock in the RFP-GFP tag into the mouse genome, fusing it with the endogenous ER sheet protein CKAP4/CLIMP63 or the endogenous ER tubular protein REEP5 (Fig. 1 A and Fig. 2 A), as tagging a fluorescent protein to endogenous ER membrane proteins is feasible (Zheng et al., 2021). We successfully generated the knock-in lines, which were verified by genomic DNA PCR and sequencing (Fig. 1 B and Fig. 2 B). However, in the RFP-GFP-Ckap4 reporter mice, we scarcely detected the expression of full-length RFP-GFP-CKAP4 in heterozygote mice, except in the testis for unknown reasons (Fig. 1 C). Additionally, we struggled to detect fluorescence in the tissues (Fig. 1 D). In the RFP-GFP-Reep5 knock-in mice, we detected full-length RFP-GFP-REEP5 and cleaved RFP signals in the heart, pancreas, and brown adipose tissue (BAT) in both heterozygotes and homozygotes (Fig. 2, C and D). Additionally, we observed RFP-positive, GFP-negative (RFP+GFP-) signals in these tissues (Fig. 2 E), indicating successful knock-in of RFP-GFP resulted in endogenous expression of RFP-GFP-REEP5, revealing tubular ER-phagy flux in several tissues. However, the fluorescence intensity of RFP-GFP and RFP-only puncta in RFP-GFP-REEP5 tissues appeared weak, making it challenging to visualize the architecture of tubular ER and the flux of tubular ER-phagy in other tissues or organs. In conclusion, our investigation of knock-in strategies informed us of the challenges associated with faithfully visualizing sheet and tubular ER and their autophagy flux in vivo.

Expression of different ER-phagy reporters in cell line (related to Figs. 1, 2, and 3 ). (A) Schematic depiction of several ER-phagy reporter candidates. Each reporter incorporates the tandem fluorescent protein RFP-GFP. P1 features the RFP-GFP tandem along with the ER-lumen targeting sequence SS-KDEL. P2 consists of RFP-GFP paired with the sheet ER-membrane protein RAMP4. P3 includes RFP-GFP combined with the tubular ER-membrane protein REEP5. (B) Confocal microscopy images of HeLa cells expressing various ER-phagy reporters. HeLa cells transiently expressing each of the three reporters (P1-P3) were examined to characterize ER morphology. Scale bar: 5 μm. (C) Representative confocal microscopy images of ER-phagy in HeLa cells expressing ssYPet-TOLLES-KDEL following ER-stress inducer treatment. Cells transiently expressing ssYPet-TOLLES-KDEL were treated with 100 nM Torin1 for 4 h to induce ER-phagy. For TOLLES imaging, excitation was at 445 nm with fluorescence detection at 460–500 nm. For YPet, excitation was at 514 nm and fluorescence was detected at 530–580 nm. The pink arrowheads indicate the ER-phagy sites. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Expression of different ER-phagy reporters in cell line (related to Figs. 1, 2, and 3 ). (A) Schematic depiction of several ER-phagy reporter candidates. Each reporter incorporates the tandem fluorescent protein RFP-GFP. P1 features the RFP-GFP tandem along with the ER-lumen targeting sequence SS-KDEL. P2 consists of RFP-GFP paired with the sheet ER-membrane protein RAMP4. P3 includes RFP-GFP combined with the tubular ER-membrane protein REEP5. (B) Confocal microscopy images of HeLa cells expressing various ER-phagy reporters. HeLa cells transiently expressing each of the three reporters (P1-P3) were examined to characterize ER morphology. Scale bar: 5 μm. (C) Representative confocal microscopy images of ER-phagy in HeLa cells expressing ssYPet-TOLLES-KDEL following ER-stress inducer treatment. Cells transiently expressing ssYPet-TOLLES-KDEL were treated with 100 nM Torin1 for 4 h to induce ER-phagy. For TOLLES imaging, excitation was at 445 nm with fluorescence detection at 460–500 nm. For YPet, excitation was at 514 nm and fluorescence was detected at 530–580 nm. The pink arrowheads indicate the ER-phagy sites. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Construction and identification of RFP-GFP-Ckap4 knock-in transgenic mice. (A) Schematic illustrating the construction of the ER-phagy reporter Ckap4-KI using a knock-in mouse model. The tandem fluorescent protein RFP-GFP was inserted at the 5′ end of the first exon of the Ckap4 gene on chromosome 10. (B) Genotyping of transgenic Ckap4-KI mice. Mouse genotypes were identified using PCR with three pairs of primers, as detailed in the materials section. “WT” denotes wild type, “Het” indicates heterozygote. (C) Western blot analysis demonstrating the expression of the Ckap4-KI reporter in knock-in mice. The expression of the Ckap4-KI reporter was assessed in various tissues of both wild-type and knock-in mice. Double red asterisks (**) indicate the fused RFP-GFP-CKAP4 protein, detected by anti-CKAP4 and anti-RFP antibodies. Single red asterisks (*) denote endogenous CKAP4 detected by anti-CKAP4 antibody. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Tissues were harvested from 8-wk-old mice. “−” denotes WT, “+” represents heterozygotes. (D) Representative microscopy images illustrating the localization and expression level of the Ckap4-KI reporter in mouse testis tissue. Scale bar: 20 μm. See also Fig. S1. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Construction and identification of RFP-GFP-Ckap4 knock-in transgenic mice. (A) Schematic illustrating the construction of the ER-phagy reporter Ckap4-KI using a knock-in mouse model. The tandem fluorescent protein RFP-GFP was inserted at the 5′ end of the first exon of the Ckap4 gene on chromosome 10. (B) Genotyping of transgenic Ckap4-KI mice. Mouse genotypes were identified using PCR with three pairs of primers, as detailed in the materials section. “WT” denotes wild type, “Het” indicates heterozygote. (C) Western blot analysis demonstrating the expression of the Ckap4-KI reporter in knock-in mice. The expression of the Ckap4-KI reporter was assessed in various tissues of both wild-type and knock-in mice. Double red asterisks (**) indicate the fused RFP-GFP-CKAP4 protein, detected by anti-CKAP4 and anti-RFP antibodies. Single red asterisks (*) denote endogenous CKAP4 detected by anti-CKAP4 antibody. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Tissues were harvested from 8-wk-old mice. “−” denotes WT, “+” represents heterozygotes. (D) Representative microscopy images illustrating the localization and expression level of the Ckap4-KI reporter in mouse testis tissue. Scale bar: 20 μm. See also Fig. S1. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Construction and identification of RFP-GFP-Reep5 knock-in transgenic mice. (A) Schematic for constructing the ER-phagy reporter Reep5-KI using a knock-in mouse model. Tandem fluorescent protein RFP-GFP was inserted at the 5′ end of the first exon of the Reep5 gene on chromosome 18. (B) Genotyping of transgenic Reep5-KI mice. Mouse genotypes were determined using PCR with three pairs of primers, as detailed in the materials section. (C and D) Western blot analysis demonstrating the expression of the Reep5-KI reporter in knock-in mice. The expression of the Reep5-KI reporter was assessed in various tissues of both wild-type and knock-in mice. Double red asterisks (**) indicate the fused RFP-GFP-REEP5 protein, single red asterisks (*) denote endogenous REEP5 identified by anti-REEP5 antibody, and single black asterisks (*) highlight the RFP fragments. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Tissues were obtained from 8-wk-old mice. “−” denotes WT, “+” represents heterozygotes, and “++” indicates homozygotes. (E) Representative microscopy images illustrating the localization and expression level of the Reep5-KI reporter in mouse pancreas tissue. Homozygotes are denoted as “Hom.” Scale bar: 20 μm. See also Fig. S1. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

Construction and identification of RFP-GFP-Reep5 knock-in transgenic mice. (A) Schematic for constructing the ER-phagy reporter Reep5-KI using a knock-in mouse model. Tandem fluorescent protein RFP-GFP was inserted at the 5′ end of the first exon of the Reep5 gene on chromosome 18. (B) Genotyping of transgenic Reep5-KI mice. Mouse genotypes were determined using PCR with three pairs of primers, as detailed in the materials section. (C and D) Western blot analysis demonstrating the expression of the Reep5-KI reporter in knock-in mice. The expression of the Reep5-KI reporter was assessed in various tissues of both wild-type and knock-in mice. Double red asterisks (**) indicate the fused RFP-GFP-REEP5 protein, single red asterisks (*) denote endogenous REEP5 identified by anti-REEP5 antibody, and single black asterisks (*) highlight the RFP fragments. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Tissues were obtained from 8-wk-old mice. “−” denotes WT, “+” represents heterozygotes, and “++” indicates homozygotes. (E) Representative microscopy images illustrating the localization and expression level of the Reep5-KI reporter in mouse pancreas tissue. Homozygotes are denoted as “Hom.” Scale bar: 20 μm. See also Fig. S1. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

Next, we endeavored to create reporter mice for bulk ER-phagy measurement by comparing two different tagging strategies: RFP-GFP (Chino et al., 2019) or TOLLES-YPet (Katayama et al., 2020) (Fig. 3 A). When the dual-FP tags were expressed in the ER lumen, they effectively labeled the ER network without inducing noticeable cytotoxicity (Fig. S1 C). Given the absence of reported TOLLES-YPet transgenic animals, we leaned toward selecting RFP-GFP for further studies. Upon ER-phagy induction using a starvation medium, EBSS, a glycosylation inhibitor, Tunicamycin (TCA), or an mTOR inhibitor, Torin1, ssRFP-GFP-KDEL demonstrated the ability to quantitatively reveal heightened ER-phagy flux in cultured cells (Fig. 3, B–E). Next, we asked whether this probe could detect the autophagic degradation of different ER subdomains. In mammals, sheet and tubular ER-phagy are mediated by distinct ER-phagy receptors (Chino and Mizushima, 2020; Ferro-Novick et al., 2021), all of which are expressed in different tissues at varying levels in mice (Fig. 3 F). Indeed, using this probe, we could readily measure ER-phagy–induced by the overexpression of these ER-phagy receptors in HeLa cells (Fig.3 G).

Comparison of two ER-phagy reporter strategies. (A) Schematic representation of two ER-phagy reporters. Left: the key elements of reporters include the tandem fluorescent proteins RFP-GFP, as well as YPet-TOLLES, paired with ER-lumen targeting sequence, KDEL. Both RFP and TOLLES demonstrate increased resistance to acidity. Right: ssRFP-GFP-KDEL is cleaved by lysosomal enzymes to yield the RFP fragment, while the GFP signal is quenched in lysosomes. (B–D) Confocal microscopy images of HeLa cells expressing the ER lumen-targeting, tandem RFP-GFP (ER-TRG, ssRFP-GFP-KDEL) tag under various conditions. HeLa cells expressing ER-TRG were subjected to treatments with EBSS (14 h), Tunicamycin (1 μg/ml, 16 h), or Torin1 (100 nM, 4 h) to induce ER stress. Scale bar: 5 μm. (E) Quantitative analysis of RFP+ puncta per cell following ER stress inducer treatment as depicted in Fig. 1, B–D. HeLa cells expressing ER-TRG were treated with EBSS (14 h), Tunicamycin (1 μg/ml, 16 h), or Torin1 (100 nM, 4 h) to induce ER stress. Data were collected from 50 to 80 cells for each condition. Values were stated as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using Mann–Whitney test. ***P < 0.001. (F) Gene expression levels of different ER-phagy receptors in various mouse tissues. Data were retrieved from the online GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov-/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE10246). Tissue labels include adipose brown (Adipose b), adipose white (Adipose w), cerebellum (Cereb), cerebral cortex (Cereb C), hippocampus (Hippoca), large intestine (Intest l), small intestine (Intest s), osteoclasts (Osteo), pancreas, placenta, and skeletal muscle (Skeletal m). (G) Representative confocal microscopy images showing ER-phagy induced by ER-phagy receptors. HeLa cells stably expressing ER-TRG were transfected with expression plasmids for ER-phagy receptors for 24 h, followed by fixation for confocal microscopy analysis. Scale bar: 5 μm. See also Fig. S1.

Comparison of two ER-phagy reporter strategies. (A) Schematic representation of two ER-phagy reporters. Left: the key elements of reporters include the tandem fluorescent proteins RFP-GFP, as well as YPet-TOLLES, paired with ER-lumen targeting sequence, KDEL. Both RFP and TOLLES demonstrate increased resistance to acidity. Right: ssRFP-GFP-KDEL is cleaved by lysosomal enzymes to yield the RFP fragment, while the GFP signal is quenched in lysosomes. (B–D) Confocal microscopy images of HeLa cells expressing the ER lumen-targeting, tandem RFP-GFP (ER-TRG, ssRFP-GFP-KDEL) tag under various conditions. HeLa cells expressing ER-TRG were subjected to treatments with EBSS (14 h), Tunicamycin (1 μg/ml, 16 h), or Torin1 (100 nM, 4 h) to induce ER stress. Scale bar: 5 μm. (E) Quantitative analysis of RFP+ puncta per cell following ER stress inducer treatment as depicted in Fig. 1, B–D. HeLa cells expressing ER-TRG were treated with EBSS (14 h), Tunicamycin (1 μg/ml, 16 h), or Torin1 (100 nM, 4 h) to induce ER stress. Data were collected from 50 to 80 cells for each condition. Values were stated as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using Mann–Whitney test. ***P < 0.001. (F) Gene expression levels of different ER-phagy receptors in various mouse tissues. Data were retrieved from the online GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov-/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE10246). Tissue labels include adipose brown (Adipose b), adipose white (Adipose w), cerebellum (Cereb), cerebral cortex (Cereb C), hippocampus (Hippoca), large intestine (Intest l), small intestine (Intest s), osteoclasts (Osteo), pancreas, placenta, and skeletal muscle (Skeletal m). (G) Representative confocal microscopy images showing ER-phagy induced by ER-phagy receptors. HeLa cells stably expressing ER-TRG were transfected with expression plasmids for ER-phagy receptors for 24 h, followed by fixation for confocal microscopy analysis. Scale bar: 5 μm. See also Fig. S1.

Evaluating ER-phagy in vitro using ER-TRG mice-derived cell lines

Subsequently, a knock-in (KI) transgenic mouse line was created by integrating a single copy of ssRFP-GFP-KDEL (Chino et al., 2019) into the Hipp11 (H11) locus on chromosome 11, with a C57BL/6 background (Fig. 4 A). For convenience, we named this mouse line ER-TRG mice, as they stably express the ER lumen-targeting, tandem RFP-GFP (ER-TRG) probe under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer fused to the chicken β-actin promoter (Hitoshi et al., 1991; Saito and Nakatsuji, 2001). Previous studies have shown that the KI of a transgene in the H11 locus can achieve ubiquitous expression of transgene without causing any detrimental side-effects (Sun et al., 2015; Tasic et al., 2011). The offspring’s ratios adhered to Mendel’s law for both homozygotes and heterozygotes of ER-TRG mice. While a slight weight reduction in the homozygotes suggested in vivo toxicity, heterozygous ER-TRG reporter mice appeared healthy (Fig. S2, A and B) and exhibited robust fluorescence intensity, enabling convenient detection of ER-phagy both in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 4 B). Consequently, we exclusively utilized heterozygous reporter mice for ER-phagy characterization in this study.

Generation of ER-TRG knock-in mice and assessment of ER-phagy in primary cells derived from the ER-phagy reporter mouse. (A) Schematic representation of the gene targeting strategy illustrating the insertion of ssRFP-GFP-KDEL into the H11 locus to create the ER-TRG mouse model via CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. The CAG promoter (CMV immediate enhancer/β-actin) and the Kozak sequence (a key eukaryotic mRNA translation initiation site) are highlighted. (B) Whole-mount pictures of E14.5 ER-TRG (+/−) embryos showing the transgenic RFP and GFP fluorescence. Scale bar: 1 mm. (C) Confocal microscopy images showing RFP-GFP fluorescence colocalization with lysosomes in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells under mTOR inhibition. MEF cells, isolated from E13.5 ER-TRG (+/−) embryos, were treated with 100 nM Torin1 for 4 h. LysoTracker, a cell-permeable lysosomal marker, was used to identify and trace acidic organelles in live cells. Lysosomes were also marked by LAMP1. Enhanced images demonstrate RFP-only signals colocalizing with lysosomes. The pink arrowheads indicate the ER-phagy sites. Scale bar: 5 μm. (D–F) Confocal microscopy images of RFP and GFP fluorescence in cultured primary cells. Sensory neurons, isolated from dorsal root ganglia (DRG) of E14.5 ER-TRG (+/−) embryos (D), were marked by Tuj1, a neuronal marker. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (E) and hepatocytes (F) were isolated from adult ER-TRG (+/−) mice. The cells were examined for expression and subcellular localization of the fluorescent proteins. Scale bar: 10 μm. (G–I) Immunoblot analysis showing the expression of ssRFP-GFP-KDEL in primary cells isolated from transgenic mice. Cell extracts from wild-type and ER-TRG transgenic mice were subjected to immunoblotting with specific antibodies. In MEF cells, BMDMs, and hepatocytes, the full-length RFP-GFP was detected in both heterozygotes and homozygotes. Full-length RFP-GFP and RFP fragments were identified using an anti-RFP antibody. The presence of RFP fragments indicates ER-phagy activity, representing the ER-phagy product. GAPDH and Tubulin were used as internal controls. “−” denotes WT, “+” represents heterozygotes, and “++” indicates homozygotes. See also Fig. S2. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Generation of ER-TRG knock-in mice and assessment of ER-phagy in primary cells derived from the ER-phagy reporter mouse. (A) Schematic representation of the gene targeting strategy illustrating the insertion of ssRFP-GFP-KDEL into the H11 locus to create the ER-TRG mouse model via CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. The CAG promoter (CMV immediate enhancer/β-actin) and the Kozak sequence (a key eukaryotic mRNA translation initiation site) are highlighted. (B) Whole-mount pictures of E14.5 ER-TRG (+/−) embryos showing the transgenic RFP and GFP fluorescence. Scale bar: 1 mm. (C) Confocal microscopy images showing RFP-GFP fluorescence colocalization with lysosomes in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells under mTOR inhibition. MEF cells, isolated from E13.5 ER-TRG (+/−) embryos, were treated with 100 nM Torin1 for 4 h. LysoTracker, a cell-permeable lysosomal marker, was used to identify and trace acidic organelles in live cells. Lysosomes were also marked by LAMP1. Enhanced images demonstrate RFP-only signals colocalizing with lysosomes. The pink arrowheads indicate the ER-phagy sites. Scale bar: 5 μm. (D–F) Confocal microscopy images of RFP and GFP fluorescence in cultured primary cells. Sensory neurons, isolated from dorsal root ganglia (DRG) of E14.5 ER-TRG (+/−) embryos (D), were marked by Tuj1, a neuronal marker. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (E) and hepatocytes (F) were isolated from adult ER-TRG (+/−) mice. The cells were examined for expression and subcellular localization of the fluorescent proteins. Scale bar: 10 μm. (G–I) Immunoblot analysis showing the expression of ssRFP-GFP-KDEL in primary cells isolated from transgenic mice. Cell extracts from wild-type and ER-TRG transgenic mice were subjected to immunoblotting with specific antibodies. In MEF cells, BMDMs, and hepatocytes, the full-length RFP-GFP was detected in both heterozygotes and homozygotes. Full-length RFP-GFP and RFP fragments were identified using an anti-RFP antibody. The presence of RFP fragments indicates ER-phagy activity, representing the ER-phagy product. GAPDH and Tubulin were used as internal controls. “−” denotes WT, “+” represents heterozygotes, and “++” indicates homozygotes. See also Fig. S2. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Identification of ER-phagy reporter mouse (related to Fig. 4 ). (A) Representative images of mouse morphology of wild-type and heterozygous ER-TRG adult mice. Scale bar: 2 cm. (B) Graphs illustrating the body weights of male and female wild-type and heterozygous ER-TRG mice. Statistical analyses of body weights were performed on 8-wk-old male and female mice. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 5–8 per group). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. *P <0.05. (C) Quantification of RFP+ puncta colocalization with lysosomes in primary MEF cells under mTOR inhibition. The number of RFP+ puncta that colocalized with LysoTracker or LAMP1 signals was calculated using ImageJ for each treatment. Data were collected from 20 to 30 cells for each condition. Values were stated as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001. (D) Confocal microscopy images showing the colocalization of RFP-GFP fluorescence with lysosomes in primary MEF cells under mTOR inhibition. MEF cells, derived from E13.5 ER-TRG (+/−) embryos, were treated with 100 nM Torin1 for 4 h. CTSD, a lysosomal enzyme, was employed as a lysosomal marker. Enlarged views reveal RFP-only signals colocalizing with lysosomes. The pink arrowheads indicate the ER-phagy sites. Scale bar: 5 μm. (E) Immunoblot analysis of PERK and p-PERK in primary MEF cell extracts. Cells were isolated from E13.5 embryos of ER-TRG (+/−) pregnant mice. Samples labeled #1, #2, and #3 represent cells from different mice. Cells #3 from the ER-TRG (+/−) group were used as a positive control, treated with Tg (1 μM) for 0, 1, 2, 3 h, respectively. “SE” denotes short exposure, while “LE” indicates long exposure. (F) Immunoblot analysis of PERK and phosphorylated PERK (p-PERK) in various tissues of wild-type and heterozygous ER-TRG mice. Tissue homogenates were probed using specific anti-PERK and p-PERK antibodies. Tubulin served as an internal control. (G) Quantitative analysis of ER-phagy levels in primary cells from ER-TRG (+/−) mice. The number of RFP+ puncta per cell in sensory neurons, BMDMs and hepatocytes was calculated using ImageJ and quantified for each treatment. Values were stated as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001. (H and I) Quantitative analysis of immunoblotting showing ER-phagy activities in BMDMs and hepatocytes isolated from ER-TRG (+/−) mice. The band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 3). (J) Fluorescence quantification methods. The level of ER-phagy was defined from two aspects: (a) ER-phagy is defined as the number of pixels of RFP-only puncta divided by the total pixels (RFP + GFP), which is used to delineate the total area of tissue or cells because some section images did not completely fill the field of view. (b) ER-phagy is also defined as the fluorescence intensity ratio of lysosomal signals (RFP-only puncta) to total RFP signals. The method is described in detail in Materials and methods. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

Identification of ER-phagy reporter mouse (related to Fig. 4 ). (A) Representative images of mouse morphology of wild-type and heterozygous ER-TRG adult mice. Scale bar: 2 cm. (B) Graphs illustrating the body weights of male and female wild-type and heterozygous ER-TRG mice. Statistical analyses of body weights were performed on 8-wk-old male and female mice. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 5–8 per group). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. *P <0.05. (C) Quantification of RFP+ puncta colocalization with lysosomes in primary MEF cells under mTOR inhibition. The number of RFP+ puncta that colocalized with LysoTracker or LAMP1 signals was calculated using ImageJ for each treatment. Data were collected from 20 to 30 cells for each condition. Values were stated as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001. (D) Confocal microscopy images showing the colocalization of RFP-GFP fluorescence with lysosomes in primary MEF cells under mTOR inhibition. MEF cells, derived from E13.5 ER-TRG (+/−) embryos, were treated with 100 nM Torin1 for 4 h. CTSD, a lysosomal enzyme, was employed as a lysosomal marker. Enlarged views reveal RFP-only signals colocalizing with lysosomes. The pink arrowheads indicate the ER-phagy sites. Scale bar: 5 μm. (E) Immunoblot analysis of PERK and p-PERK in primary MEF cell extracts. Cells were isolated from E13.5 embryos of ER-TRG (+/−) pregnant mice. Samples labeled #1, #2, and #3 represent cells from different mice. Cells #3 from the ER-TRG (+/−) group were used as a positive control, treated with Tg (1 μM) for 0, 1, 2, 3 h, respectively. “SE” denotes short exposure, while “LE” indicates long exposure. (F) Immunoblot analysis of PERK and phosphorylated PERK (p-PERK) in various tissues of wild-type and heterozygous ER-TRG mice. Tissue homogenates were probed using specific anti-PERK and p-PERK antibodies. Tubulin served as an internal control. (G) Quantitative analysis of ER-phagy levels in primary cells from ER-TRG (+/−) mice. The number of RFP+ puncta per cell in sensory neurons, BMDMs and hepatocytes was calculated using ImageJ and quantified for each treatment. Values were stated as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001. (H and I) Quantitative analysis of immunoblotting showing ER-phagy activities in BMDMs and hepatocytes isolated from ER-TRG (+/−) mice. The band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 3). (J) Fluorescence quantification methods. The level of ER-phagy was defined from two aspects: (a) ER-phagy is defined as the number of pixels of RFP-only puncta divided by the total pixels (RFP + GFP), which is used to delineate the total area of tissue or cells because some section images did not completely fill the field of view. (b) ER-phagy is also defined as the fluorescence intensity ratio of lysosomal signals (RFP-only puncta) to total RFP signals. The method is described in detail in Materials and methods. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

To validate the reliability of the probe, we assessed mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from the reporter mice. Confocal microscopy analysis demonstrated that the reporter faithfully labeled the ER network, and ER-phagy responded to Torin1 treatment (Fig. 4 C and Fig. S2 C). Importantly, the RFP+GFP- puncta colocalized with lysosomes labeled by LysoTracker, LAMP1, and cathepsin D (CSTD) (Fig. 4 C and Fig. S2 D), indicating the engulfment of RFP-GFP-labeled ER structures by lysosomes. Considering that constitutive expression of exogenous FPs in the ER lumen might induce ER stress or unfolded protein response (UPR), we compared the levels of PERK activation, an indicator of ER stress, in MEF cells derived from either heterozygous ER-TRG mice or their wild-type littermates. As shown in Fig. S2 E, PERK largely stayed unphosphorylated, implying that no significant ER stress was stimulated by the expression of the exogenous TRG in the MEF cells. Furthermore, we showed that PERK signaling was not altered by the expression of the probe in vivo, except for the pancreas (Fig. S2 F). Therefore, the expression of the probe was well-tolerated without causing obvious deleterious side-effects. To further demonstrate the value of the reporter mice for in vitro studies, we established primary cultures for sensory neurons from dorsal root ganglia (DRG), bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), and hepatocytes. Basal ER-phagy activity was relatively low in DRG sensory neurons compared with that in BMDMs and hepatocytes (Fig. 4, D–F and Fig. S2 G). ER-phagy occurred at the perinuclear regions in BMDMs, while showing robust activities at both the periphery and perinuclear areas in hepatocytes. Furthermore, we confirmed the expression of the probe and cleaved free RFP by performing anti-RFP western blot analysis for the isolated primary cell cultures (Fig. 4, G–I; and Fig. S2, H and I). The ER-phagy flux measured by cleaved RFP signals was consistent with the imaging data. Our results demonstrate that ER-TRG mice provide a rich source of diverse cell types for in vitro research.

ER-phagy varies between and within tissues (spatial)

In general, basal ER-phagy can be readily measured within the ER-TRG mouse tissues that have been analyzed in this study. For instance, GFP and RFP signals illuminated the hepatic sections (Fig. 5 A), and mild ER-phagy activity indicated by the RFP+GFP− puncta was detected within the hepatic tissue with a slight intensification in the areas surrounding the central vein (CV) (Fig. 5, A and B; and Fig. S3 A). Importantly, the RFP+GFP- puncta colocalized with lysosome markers LAMP1 and CTSD (Fig. 5, A and C; and Fig. S3, A and B), indicating that these structures represent ER-containing autolysosomes, which was consistent with in vitro data. Hepatic ER-phagy was dependent on the canonical autophagy process as the knockdown of the essential autophagy gene Atg7, achieved through AAV9-mediated shRNA delivery to hepatic tissues, significantly reduced the appearance of RFP+GFP− signal, which was further confirmed by anti-RFP western blot analysis (Fig. 5, D–F; and Fig. S3, C and D).

Spatial assessment of ER-phagy activity and ER architecture in different tissues. (A) Co-labeling with LAMP1 indicates that almost all red-positive (RFP+) compartments are also lysosomal marker positive and yield purple (red: RFP+, blue: LAMP1+) signals in the hepatocytes of 8-wk ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Lysosomes not engaged in autophagy (LAMP1 negative) remain blue. Inset: enlarged image of area indicated by dashed frame. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of different regions of liver from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice at adulthood. The calculations were performed for regions inside or outside the yellow dashed box in mouse liver (S3A), referred to as the inner and outer regions. The inner regions represent the vicinity of the CV zone, while the outer regions represent the areas away from the CV zone. The pixel number of RFP-only signals and total RFP signals were calculated by ImageJ and the ratio of RFP: total area (RFP+GFP) was quantified (left). The intensity of RFP-only signals and total RFP signals were calculated by ImageJ on a pixel-by-pixel basis and the fluorescence ratio of RFP: total RFP was quantified (right). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Statistical differences were evaluated using Student’s t test. ***P < 0.001. (C) Quantification of RFP-only ER-lysosomes (RFP+LAMP1+) in liver sections obtained from ER-TRG mice. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4). (D–F) Representative images and quantitative analysis of ER-TRG signals in the liver of control and Atg7-knockdown mice. 8-wk-old ER-TRG (+/−) mice were injected with AAV-shNC and AAV-shAtg7 and underwent a 4-wk infection period. Quantitative analysis of RFP+ signals and immunoblotting of RFP cleavage indicated reduced ER-phagy in hepatocytes after Atg7 knockdown (F). The band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. The efficiency of ATG7 knockdown is evidenced by the expression levels of ATG7, p62, and LC3 in liver samples. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (G–J) Representative confocal images depicting ER-phagy levels in the lung and adipose tissues of ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Quantitative analysis including alveoli and bronchioles (G), brown adipose tissue (BAT), and epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) (I) indicated different ER abundance and positioning of ER-phagy signals within tissues (n = 4–6). Magnified images highlight RFP-only signals in cells of various tissues. Adult male ER-TRG (+/−) mice were used in all experiments. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 6) (H). Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4–5) (J). Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (K) Representative confocal images depicting ER-phagy levels in the heart sections and quantitative analysis of ER-phagy level of heart in ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 5). Scale bar: 20 μm. (L) Immunoblot analysis of ssRFP-GFP-KDEL expression in various tissues of transgenic mice. Tissue homogenates from one wild-type and one ER-TRG (+/−) transgenic mouse were probed with specific antibodies. Both full-length RFP-GFP and RFP fragments were detected using an anti-RFP antibody. The band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. GAPDH and Tubulin were used as internal controls. See also Fig. S3. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Spatial assessment of ER-phagy activity and ER architecture in different tissues. (A) Co-labeling with LAMP1 indicates that almost all red-positive (RFP+) compartments are also lysosomal marker positive and yield purple (red: RFP+, blue: LAMP1+) signals in the hepatocytes of 8-wk ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Lysosomes not engaged in autophagy (LAMP1 negative) remain blue. Inset: enlarged image of area indicated by dashed frame. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of different regions of liver from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice at adulthood. The calculations were performed for regions inside or outside the yellow dashed box in mouse liver (S3A), referred to as the inner and outer regions. The inner regions represent the vicinity of the CV zone, while the outer regions represent the areas away from the CV zone. The pixel number of RFP-only signals and total RFP signals were calculated by ImageJ and the ratio of RFP: total area (RFP+GFP) was quantified (left). The intensity of RFP-only signals and total RFP signals were calculated by ImageJ on a pixel-by-pixel basis and the fluorescence ratio of RFP: total RFP was quantified (right). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Statistical differences were evaluated using Student’s t test. ***P < 0.001. (C) Quantification of RFP-only ER-lysosomes (RFP+LAMP1+) in liver sections obtained from ER-TRG mice. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4). (D–F) Representative images and quantitative analysis of ER-TRG signals in the liver of control and Atg7-knockdown mice. 8-wk-old ER-TRG (+/−) mice were injected with AAV-shNC and AAV-shAtg7 and underwent a 4-wk infection period. Quantitative analysis of RFP+ signals and immunoblotting of RFP cleavage indicated reduced ER-phagy in hepatocytes after Atg7 knockdown (F). The band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. The efficiency of ATG7 knockdown is evidenced by the expression levels of ATG7, p62, and LC3 in liver samples. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (G–J) Representative confocal images depicting ER-phagy levels in the lung and adipose tissues of ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Quantitative analysis including alveoli and bronchioles (G), brown adipose tissue (BAT), and epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) (I) indicated different ER abundance and positioning of ER-phagy signals within tissues (n = 4–6). Magnified images highlight RFP-only signals in cells of various tissues. Adult male ER-TRG (+/−) mice were used in all experiments. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 6) (H). Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4–5) (J). Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (K) Representative confocal images depicting ER-phagy levels in the heart sections and quantitative analysis of ER-phagy level of heart in ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 5). Scale bar: 20 μm. (L) Immunoblot analysis of ssRFP-GFP-KDEL expression in various tissues of transgenic mice. Tissue homogenates from one wild-type and one ER-TRG (+/−) transgenic mouse were probed with specific antibodies. Both full-length RFP-GFP and RFP fragments were detected using an anti-RFP antibody. The band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. GAPDH and Tubulin were used as internal controls. See also Fig. S3. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Spatial assessment of ER-phagy activity and ER architecture in different tissues (related to Fig. 5 ). (A) Colabeling with CTSD indicates that almost all red-positive compartments are also lysosomal marker positive and yield purple (red: RFP+, blue: CTSD+) signals in the hepatocytes of 8-wk-old ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Lysosomes not engaged in autophagy (CTSD negative) remain blue. An inset shows an enlarged view of the area indicated by the yellow dashed frame. The area inside the yellow dashed box represents the vicinity of the CV zone, while the area outside the yellow dashed box represents the areas away from the CV zone. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Quantification of RFP-only ERlysosomes (RFP+CTSD+) in liver sections obtained from ER-TRG mice. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4). (C and D) Immunoblotting analysis of ATG7, p62, and LC3 in primary hepatocytes indicates the efficiency of ATG7 knockdown by AAV infection. Cell extracts from AAV-shNC and AAV-shAtg7 transgenic mice were examined via immunoblotting with specific antibodies. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t test, with ***P < 0.001. (E–G) Confocal imaging and quantitative analysis of the intestines and colons from adult ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice reveal varied ER abundance and ER-phagy activity in the villi of the small intestine and crypt (left) (E and F), compared to the comparable ER-phagy activity in colon cells (right) (E and G). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4) (F). Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4) (G). Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Scale bar: 20 μm. (H and I) ER abundance and positioning of ER-phagy signals within the mouse brain. Magnified images highlight RFP-only signals in cells of various tissues, with specific focus on an astrocyte (#1), neurons around the hippocampus (#2), and neurons around the cortex (#3) in the brain. Quantitative analysis of ER-phagy puncta of cells in the brain of adult male ER-TRG (+/−) mice (I). n = 60–80 cells per group from three mice. Scale bars: 200 μm (thumbnail), 10 μm (inset). (J and K) Confocal imaging and quantitative analysis of ER-phagy level of the testis in adult male ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4). Scale bar: 20 μm. (L–O) Confocal imaging of the adrenal glands and epididymis from adult ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Magnified images depicting the smooth ER (SER) architecture and localization of ER-phagy signals within the adrenal glands (L and N). The zona grannulosa (ZG), zona fasciculata (ZF), and zona reticulosa (ZR) regions were examined. A magnified view highlights RFP-only signals in cells of adrenal glands (n = 4). Scale bar: 10 μm. Magnified images and quantitative analysis show RFP-only signals in cells of epididymis, with the initial segment (IS), caput, and cauda regions displaying varying levels of ER-phagy across different cell types (n = 4) (M and O). Values were stated as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

Spatial assessment of ER-phagy activity and ER architecture in different tissues (related to Fig. 5 ). (A) Colabeling with CTSD indicates that almost all red-positive compartments are also lysosomal marker positive and yield purple (red: RFP+, blue: CTSD+) signals in the hepatocytes of 8-wk-old ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Lysosomes not engaged in autophagy (CTSD negative) remain blue. An inset shows an enlarged view of the area indicated by the yellow dashed frame. The area inside the yellow dashed box represents the vicinity of the CV zone, while the area outside the yellow dashed box represents the areas away from the CV zone. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Quantification of RFP-only ERlysosomes (RFP+CTSD+) in liver sections obtained from ER-TRG mice. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4). (C and D) Immunoblotting analysis of ATG7, p62, and LC3 in primary hepatocytes indicates the efficiency of ATG7 knockdown by AAV infection. Cell extracts from AAV-shNC and AAV-shAtg7 transgenic mice were examined via immunoblotting with specific antibodies. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t test, with ***P < 0.001. (E–G) Confocal imaging and quantitative analysis of the intestines and colons from adult ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice reveal varied ER abundance and ER-phagy activity in the villi of the small intestine and crypt (left) (E and F), compared to the comparable ER-phagy activity in colon cells (right) (E and G). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4) (F). Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4) (G). Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Scale bar: 20 μm. (H and I) ER abundance and positioning of ER-phagy signals within the mouse brain. Magnified images highlight RFP-only signals in cells of various tissues, with specific focus on an astrocyte (#1), neurons around the hippocampus (#2), and neurons around the cortex (#3) in the brain. Quantitative analysis of ER-phagy puncta of cells in the brain of adult male ER-TRG (+/−) mice (I). n = 60–80 cells per group from three mice. Scale bars: 200 μm (thumbnail), 10 μm (inset). (J and K) Confocal imaging and quantitative analysis of ER-phagy level of the testis in adult male ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice. Values were stated as mean ± SD (n = 4). Scale bar: 20 μm. (L–O) Confocal imaging of the adrenal glands and epididymis from adult ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Magnified images depicting the smooth ER (SER) architecture and localization of ER-phagy signals within the adrenal glands (L and N). The zona grannulosa (ZG), zona fasciculata (ZF), and zona reticulosa (ZR) regions were examined. A magnified view highlights RFP-only signals in cells of adrenal glands (n = 4). Scale bar: 10 μm. Magnified images and quantitative analysis show RFP-only signals in cells of epididymis, with the initial segment (IS), caput, and cauda regions displaying varying levels of ER-phagy across different cell types (n = 4) (M and O). Values were stated as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

Within the alveoli of the lung, ER-phagy activity was heterogeneous, with vigorous RFP+GFP− signals observed in a small portion of the cells. In contrast, the bronchi of the lung, particularly the epithelial cells constituting the inner layer, displayed strong ER-phagy flux (Fig. 5, G and H). Adipose tissues showed robust ER-phagy flux in both interscapular BAT and epididymal white adipose tissues (eWAT), each possessing distinct physiological features and metabolic behavior (Fig. 5, I and J). The small intestine exhibited relatively low ER-phagy activity in the epithelium, while Paneth cells displayed high ER-phagy activity (Fig. S3, E and F). In the colon, rich in goblet cells with a large quantity of rough endoplasmic reticulum due to their role in mucus secretion, the RFP+GFP+ double-labeled ER structure was abundant, though goblet cell ER-phagy was relatively mild (Fig. S3, E and G). Varying ER-phagy activity was also observed in cells of the brain, including glia cells and neurons (Fig. S3, H and I). Leydig cells of mouse testis and adrenal glands, crucial for steroid hormone biosynthesis dependent on the smooth ER, displayed typical reticular ER structures, accompanied by abundant ER-phagy signals (Fig. S3, J–L and N). Varying ER-phagy activity was detected within and across different subregions of the adrenal gland and the epididymis (Fig. S3, L–O). Sperm maturation processes from the caput to cauda of the epididymis exhibited different ER-phagy signals in the tubular cells, with higher activity observed in the cauda (Fig. S3, M and O). In the heart, basal ER-phagy activity appeared mild in the ventricle (Fig. 5 K). To further support the conclusion that ER-phagy flux varies among different tissues and organs, RFP cleavage was measured through anti-RFP western blot analysis. Robust-free RFP signals were detected in the pancreas, heart, kidney, eWAT, liver, and soleus muscle (Fig. 5 L). These results align with the imaging data.

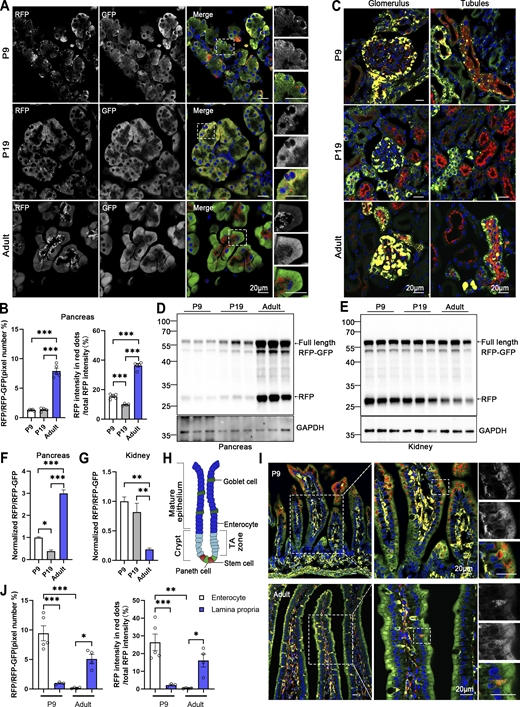

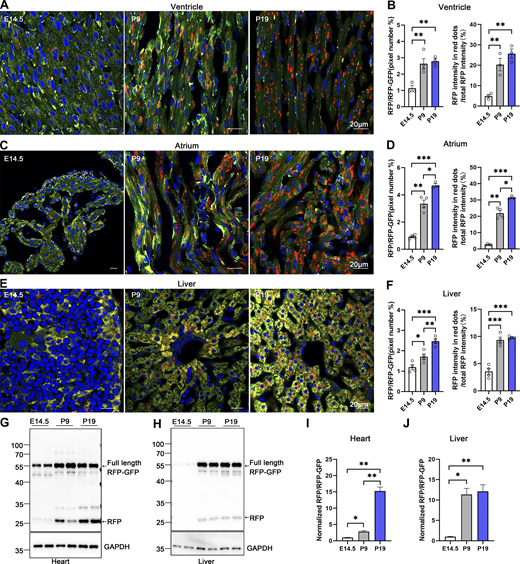

ER-phagy varies during development (temporal)

The turnover rate of the ER and its architectural changes during animal development remain unknown. To address this question, we investigated the developmental dynamics of ER-phagy in various organs. Analysis of pancreatic ER-phagy at postnatal day 9 (P9) and P19 revealed static ER-phagy flux in the islets at a comparable level to adults. In contrast, in acinar tissues, ER-phagy activity sharply decreased from P9 to P19 but rebounded to a high level in the adult stage (Fig. 6, A and B). Some adult ER-TRG mice exhibited a swelling phenotype in acinar cells, suggesting a potential side effect caused by probe expression in this subtissue. However, no other morphological abnormalities were observed in ER-TRG mice in this study. Next, we found that renal ER-phagy increased from a mild level at P9 to vigorous activity at P19 (Fig. 6 C). Immunoblotting data were comparable with the imaging data (Fig. 6, D–G). In small intestines at P9, the epithelial cell layer of villus tips exhibited high ER-phagy activity, which nearly disappeared in the adult stage (Fig. 6, H–J). In contrast, although capillaries and lymphatic vessels located in the middle of villi had a high content of the ER network, these tissues showed low ER-phagy activities at P9, which dramatically increased during the adult stage (Fig. 6, I and J). The embryonic heart showed mild and evenly distributed ER-phagy flux, incrementally elevating during development (Fig. 7, A–D). In contrast, overall ER-phagy activity in hepatocytes gradually increased and then became static from P19 to the adult stage (Fig. 7, E and F). RFP cleavage was measured through anti-RFP western blot analysis. Relative free RFP to total RFP-GFP levels were detected in the heart and liver, and the results were consistent with the imaging data (Fig. 7, G–J).

Comparative analysis of ER-phagy and ER network in developing and adult tissues. (A) Representative images of pancreas sections at postnatal day 9 (P9), P19, and in adulthood from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of ER-phagy in pancreas from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice at P9, P19, and Adult. Confocal images in 6A were quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001. (C) Representative images of kidney sections at P9, P19, and in adulthood from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice (n = 4 per group). Scale bar: 20 μm. (D–G) Immunoblot and quantitative analysis showing ER-phagy activities in pancreas and kidney isolated from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter at P9, P19, Adult. The band intensities of RFP and RFP-GFP were quantified and the ratio of RFP:RFP-GFP (normalized to WT) is shown (F and G). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (H) Schematic representation of the intestinal villus and crypt structure, including cell identities. The mature epithelium comprises goblet cells and enterocytes, while the crypt contains stem cells and Paneth cells in the transit amplifying (TA) zone. (I and J) Representative images of small intestine sections and quantitative analysis of ER-phagy activities in sub-regions at P9 and in adulthood from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice. A magnified view highlights RFP-only signals in the cells of the intestinal villus. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Comparative analysis of ER-phagy and ER network in developing and adult tissues. (A) Representative images of pancreas sections at postnatal day 9 (P9), P19, and in adulthood from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of ER-phagy in pancreas from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice at P9, P19, and Adult. Confocal images in 6A were quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001. (C) Representative images of kidney sections at P9, P19, and in adulthood from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice (n = 4 per group). Scale bar: 20 μm. (D–G) Immunoblot and quantitative analysis showing ER-phagy activities in pancreas and kidney isolated from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter at P9, P19, Adult. The band intensities of RFP and RFP-GFP were quantified and the ratio of RFP:RFP-GFP (normalized to WT) is shown (F and G). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (H) Schematic representation of the intestinal villus and crypt structure, including cell identities. The mature epithelium comprises goblet cells and enterocytes, while the crypt contains stem cells and Paneth cells in the transit amplifying (TA) zone. (I and J) Representative images of small intestine sections and quantitative analysis of ER-phagy activities in sub-regions at P9 and in adulthood from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice. A magnified view highlights RFP-only signals in the cells of the intestinal villus. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Comparative analysis of ER-phagy and ER network in developing heart and liver. (A–D) Representative images of heart sections and quantitative analysis from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice at E14.5, P9, P19. Panel A illustrates ER-phagy signals in the ventricle, while Panel C depicts these signals in the atrium, across the same developmental stages. The pixel number of RFP-only signals and total RFP signals were calculated by ImageJ and the ratio of RFP: total area (RFP+GFP) was quantified (left). The intensity of RFP-only signals and total RFP signals were calculated by ImageJ on a pixel-by-pixel basis and the fluorescence ratio of RFP: total RFP were quantified (right). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 3–4 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (E and F) Confocal imaging of ER-phagy activities and quantitative analysis in liver sections from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice at E14.5, P9, P19. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (G–J) Immunoblot and quantitative analysis showing ER-phagy activities in heart and liver isolated from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter at E14.5, P9, and P19. The band intensities of RFP and RFP-GFP were quantified and the ratio of RFP:RFP-GFP (normalized to WT) is shown (I and J). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Comparative analysis of ER-phagy and ER network in developing heart and liver. (A–D) Representative images of heart sections and quantitative analysis from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice at E14.5, P9, P19. Panel A illustrates ER-phagy signals in the ventricle, while Panel C depicts these signals in the atrium, across the same developmental stages. The pixel number of RFP-only signals and total RFP signals were calculated by ImageJ and the ratio of RFP: total area (RFP+GFP) was quantified (left). The intensity of RFP-only signals and total RFP signals were calculated by ImageJ on a pixel-by-pixel basis and the fluorescence ratio of RFP: total RFP were quantified (right). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 3–4 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (E and F) Confocal imaging of ER-phagy activities and quantitative analysis in liver sections from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter mice at E14.5, P9, P19. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (G–J) Immunoblot and quantitative analysis showing ER-phagy activities in heart and liver isolated from ER-TRG (+/−) reporter at E14.5, P9, and P19. The band intensities of RFP and RFP-GFP were quantified and the ratio of RFP:RFP-GFP (normalized to WT) is shown (I and J). Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5 per group). Statistical differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

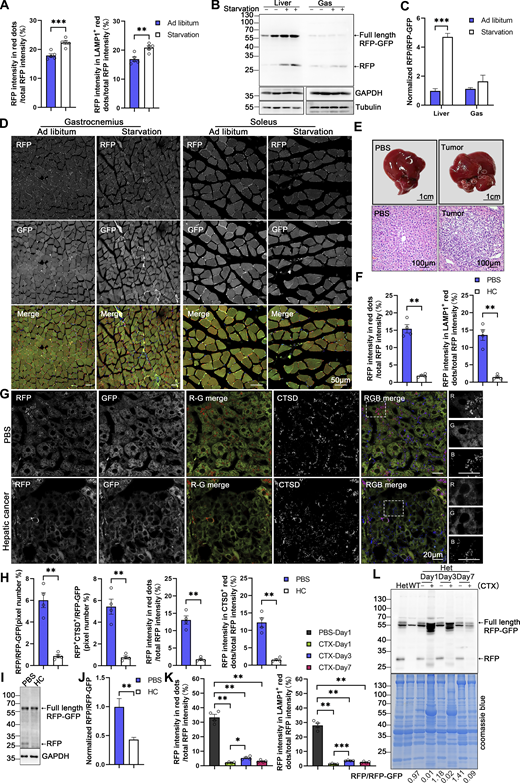

ER-phagy responses to physiopathological perturbations in vivo

Subsequently, we investigated whether ER-TRG mice can monitor the alteration of ER-phagy in vivo in response to different physiological and pathological stressors. ER-TRG mice were either fed ad libitum or subjected to 16 h of starvation. A significant increase in ER-phagy flux was detected in the liver, particularly around the CV area, in response to starvation (Fig. 8, A and B; and Fig. S4 A). However, starvation treatment failed to significantly boost ER-phagy activity in skeletal muscles (Fig. S4, B–D). These observations were further confirmed by the assessment of RFP cleavage within tissues by western blot analysis (Fig. S4, B and C). These results indicated that ER-phagy pathways in different tissues possess distinct sensitivity to environmental stressors. Next, we constructed a hepatic cancer mouse model using ER-TRG mice by tail-vein injection of a mixture of three recombinant plasmids expressing c-Myc and N-Ras, respectively (Chen and Calvisi, 2014). Hepatic tumors were observed in the fourth week after DNA administration (Fig. S4 E). Malignant features of the tumor tissues were confirmed by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. ER-phagy activity was largely abolished in the tumor tissues compared with the para-carcinoma tissues or the liver tissues in control mice (Fig. 8, C and D; and Fig. S4, F–H). The results were further validated by measuring RFP cleavage within tissues by western blot analysis (Fig. S4, I and J). Furthermore, we established a mouse muscle repair model by injecting 10 μM cardiotoxin (CTX). We observed that ER-phagy levels in the tibialis (TA) with skeletal muscle injury were largely diminished compared with the control tissues (another leg in the same mouse) at post-injury day 1 (P1) (Fig. 8, E and F; and Fig. S4 K). At P3, the abundance of the ER network in damaged skeletal muscle significantly increased with a mild rise in ER-phagy activities. At P7, new myofibrils regenerated in situ, and the surrounding sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) reformed; though ER-phagy flux partially recovered in these newborn myofibrils, it remained significantly lower than in mature myofibrils. Skeletal muscle samples were also analyzed by measuring RFP cleavage within tissues by western blot analysis (Fig. S4 L).

In vivo ER-phagy is sensitive to physio-pathological perturbations. (A and B) ER-phagy levels and quantitative analysis in the liver of ER-TRG (+/−) mice under ad libitum feeding and starvation conditions, respectively. Mice underwent a 16-h fast with free access to water, while control mice had ad libitum access to food and water. The pixel number of RFP-only, RFP+LAMP1+, and total area were calculated by ImageJ, and the ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+LAMP1+): the total area (RFP+GFP) was quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per condition). Statistical differences were evaluated using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C and D) Quantitative analysis of ER-phagy levels in the liver of ER-TRG (+/−) mice with hepatic cancer. Confocal imaging shows reduced ER-phagy level at tumor sites compared to control liver or adjacent tissue. HC refers to hepatic cancer. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were assessed using Student’s t test. ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (E and F) Representative confocal images and quantitative analysis of ER-phagy levels in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle following skeletal muscle injury induced by 10 μM cardiotoxin compared with control tissues (the other leg in the same mouse). TA samples were collected and analyzed via confocal imaging on post-injury days 1, 3, and 7. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. See also Fig. S4.

In vivo ER-phagy is sensitive to physio-pathological perturbations. (A and B) ER-phagy levels and quantitative analysis in the liver of ER-TRG (+/−) mice under ad libitum feeding and starvation conditions, respectively. Mice underwent a 16-h fast with free access to water, while control mice had ad libitum access to food and water. The pixel number of RFP-only, RFP+LAMP1+, and total area were calculated by ImageJ, and the ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+LAMP1+): the total area (RFP+GFP) was quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per condition). Statistical differences were evaluated using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C and D) Quantitative analysis of ER-phagy levels in the liver of ER-TRG (+/−) mice with hepatic cancer. Confocal imaging shows reduced ER-phagy level at tumor sites compared to control liver or adjacent tissue. HC refers to hepatic cancer. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were assessed using Student’s t test. ***P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. (E and F) Representative confocal images and quantitative analysis of ER-phagy levels in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle following skeletal muscle injury induced by 10 μM cardiotoxin compared with control tissues (the other leg in the same mouse). TA samples were collected and analyzed via confocal imaging on post-injury days 1, 3, and 7. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm. See also Fig. S4.

Assessment of ER-phagy in physio-pathological perturbations (related to Fig. 8 ). (A) Quantitative analysis indicated increased RFP+ and RFP+LAMP1+ signals at liver during starvation. The fluorescence intensity of RFP-only, RFP+LAMP1+ and total area were calculated respectively by ImageJ and the fluorescence ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+LAMP1+): the total RFP was quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (B and C) Analysis of ER-phagy levels in the liver and skeletal muscle of transgenic mice during starvation by immunoblotting. Tissue homogenates from both regularly fed and starved mice were examined through immunoblotting. Full-length RFP-GFP and RFP fragments were detected with an anti-RFP antibody and the band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Adult male wild-type and ER-TRG (+/−) mice were used in experiments. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001. (D) Confocal imaging of RFP and GFP signals in the skeletal muscles (gastrocnemius, soleus) of ER-TRG (+/−) mice under normal feeding and starvation. Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining of liver sections from PBS-treated and hepatic cancer model mice in ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Control mice received PBS injections, while model mice were injected with plasmids expressing C-Myc, N-Ras, and SB11 for 4 wk. Scale bars: 1 cm (top), 100 μm (bottom). (F) Quantitative analysis indicated reduced RFP+ and RFP+LAMP1+ signals at tumor sites compared with control liver or adjacent tissue. The fluorescence ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+LAMP1+): the total RFP was quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01. (G and H) ER-phagy levels and quantitative analysis in the liver of ER-TRG (+/−) mice with hepatic cancer. Confocal imaging reveals diminished ER-phagy at tumor sites relative to control liver or adjacent tissues, as indicated by CTSD co-staining. The pixel number, fluorescence intensity of RFP-only, RFP+CTSD+ and total area were calculated by ImageJ. The ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+CTSD+): the total area (RFP+GFP) and the fluorescence ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+CTSD+): the total RFP were quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were assessed using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01. Scale bar: 20 μm. (I and J) Analysis of ER-phagy levels in the liver of ER-TRG (+/−) mice with hepatic cancer by immunoblotting. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01. (K) Quantitative analysis indicated altered RFP+ and RFP+CTSD+ signals in muscle cells at injury area compared to PBS-treated tissue. The fluorescence ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+LAMP1+): the total RFP was quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (L) Analysis of ER-phagy levels in the skeletal muscle of ER-TRG (+/−) mice with CTX injury by immunoblotting. The band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. Coomassie blue staining confirmed protein loading. Adult male wild-type and ER-TRG (+/−) mice were used in experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Assessment of ER-phagy in physio-pathological perturbations (related to Fig. 8 ). (A) Quantitative analysis indicated increased RFP+ and RFP+LAMP1+ signals at liver during starvation. The fluorescence intensity of RFP-only, RFP+LAMP1+ and total area were calculated respectively by ImageJ and the fluorescence ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+LAMP1+): the total RFP was quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (B and C) Analysis of ER-phagy levels in the liver and skeletal muscle of transgenic mice during starvation by immunoblotting. Tissue homogenates from both regularly fed and starved mice were examined through immunoblotting. Full-length RFP-GFP and RFP fragments were detected with an anti-RFP antibody and the band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. GAPDH and Tubulin served as internal controls. Adult male wild-type and ER-TRG (+/−) mice were used in experiments. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001. (D) Confocal imaging of RFP and GFP signals in the skeletal muscles (gastrocnemius, soleus) of ER-TRG (+/−) mice under normal feeding and starvation. Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining of liver sections from PBS-treated and hepatic cancer model mice in ER-TRG (+/−) mice. Control mice received PBS injections, while model mice were injected with plasmids expressing C-Myc, N-Ras, and SB11 for 4 wk. Scale bars: 1 cm (top), 100 μm (bottom). (F) Quantitative analysis indicated reduced RFP+ and RFP+LAMP1+ signals at tumor sites compared with control liver or adjacent tissue. The fluorescence ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+LAMP1+): the total RFP was quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01. (G and H) ER-phagy levels and quantitative analysis in the liver of ER-TRG (+/−) mice with hepatic cancer. Confocal imaging reveals diminished ER-phagy at tumor sites relative to control liver or adjacent tissues, as indicated by CTSD co-staining. The pixel number, fluorescence intensity of RFP-only, RFP+CTSD+ and total area were calculated by ImageJ. The ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+CTSD+): the total area (RFP+GFP) and the fluorescence ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+CTSD+): the total RFP were quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were assessed using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01. Scale bar: 20 μm. (I and J) Analysis of ER-phagy levels in the liver of ER-TRG (+/−) mice with hepatic cancer by immunoblotting. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t test. **P < 0.01. (K) Quantitative analysis indicated altered RFP+ and RFP+CTSD+ signals in muscle cells at injury area compared to PBS-treated tissue. The fluorescence ratio of RFP-only (or RFP+LAMP1+): the total RFP was quantified. Values were stated as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per condition). Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (L) Analysis of ER-phagy levels in the skeletal muscle of ER-TRG (+/−) mice with CTX injury by immunoblotting. The band intensity of RFP fragments relative to full-length RFP-GFP indicates the presence of ER-phagy products, signifying ER-phagy activity. Coomassie blue staining confirmed protein loading. Adult male wild-type and ER-TRG (+/−) mice were used in experiments. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

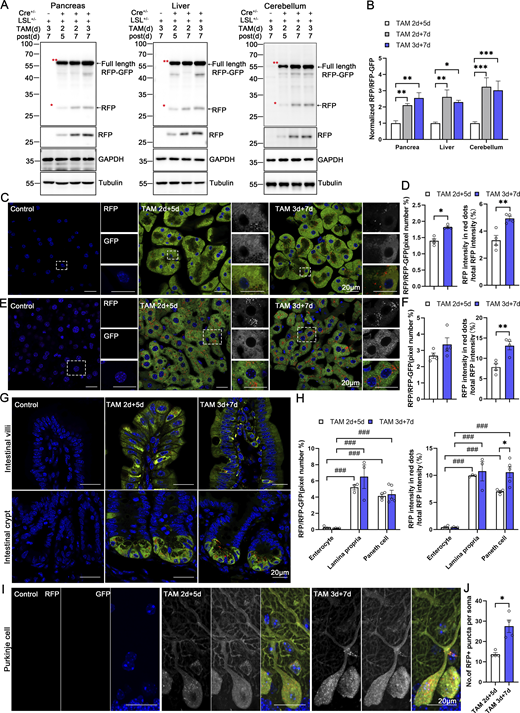

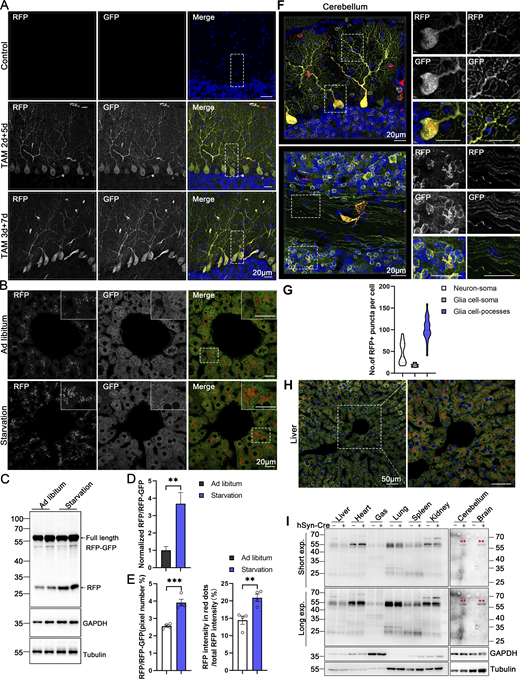

CA-ER-TRG mice enable the inducible assessment of ER-phagy in vivo

Our modern biomedical research has been significantly advanced by recombinase-based mouse genetic tools (Birling et al., 2009), allowing for the conditional activation or silencing of target gene expression in a spatially (using cell-type-specific promoters) and temporally (employing inducible promoters) controlled manner. To harness these advantages and study in vivo ER-phagy with improved spatiotemporal resolution, we generated Cre-recombinase-activated ER-TRG mice (CA-ER-TRG), expected to complement the application of ER-TRG mice. To address the potential issue of constitutive RFP accumulation in lysosomes, we explored the applicability of the inducible ER-TRG (Rosa CreERT2+/−; LSL-RFP-GFP-KDEL+/−) mice. To optimize induction conditions, the mice were treated with tamoxifen for 2 or 3 days and subsequently analyzed 5 or 7 days after induction with Rosa CreERT2−/−; LSL-RFP-GFP-KDEL+/− mice used as a control. We conducted a tissue-specific analysis of ER-phagy by immunoblotting, which detected the full-length RFP-GFP-KDEL and cleaved RFP in various tissues of tamoxifen-induced mice but not in the control (Fig. 9, A and B). Consistently, using confocal microscopy, we observed ER-phagy flux in the pancreas (Fig. 9, C and D), liver (Fig. 9, E and F), small intestine (Fig. 9, G and H), and Purkinje cells (Fig. 9, I and J; and Fig. S5 A). Additionally, we noted a robust response in ER-phagy flux alteration upon starvation treatment (Fig. S5, B–E). These results demonstrate that tamoxifen induction in ER-TRG mice enables effective measurement of ER-phagy flux across multiple tissues, as evidenced by the levels of cleaved RFP. These data further highlight tissue-specific variations in ER-phagy activity and confirm the utility of this inducible model for studying ER-phagy dynamics in vivo.