Exchange between the nucleus and the cytoplasm is controlled by nuclear pore complexes (NPCs). In animals, NPCs are anchored by the nuclear lamina, which ensures their even distribution and proper organization of chromosomes. Fungi do not possess a lamina and how they arrange their chromosomes and NPCs is unknown. Here, we show that motor-driven motility of NPCs organizes the fungal nucleus. In Ustilago maydis, Aspergillus nidulans, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae fluorescently labeled NPCs showed ATP-dependent movements at ∼1.0 µm/s. In S. cerevisiae and U. maydis, NPC motility prevented NPCs from clustering. In budding yeast, NPC motility required F-actin, whereas in U. maydis, microtubules, kinesin-1, and dynein drove pore movements. In the latter, pore clustering resulted in chromatin organization defects and led to a significant reduction in both import and export of GFP reporter proteins. This suggests that fungi constantly rearrange their NPCs and corresponding chromosomes to ensure efficient nuclear transport and thereby overcome the need for a structural lamina.

Introduction

Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) consist of ∼30 nucleoproteins that mediate bidirectional trafficking across the nuclear envelope (Blobel, 2010; Wälde and Kehlenbach, 2010; Grünwald et al., 2011). In animal cells, the NPCs are nonmotile and evenly distributed (Daigle et al., 2001; Rabut et al., 2004; Dultz and Ellenberg, 2010). This is achieved by the interaction of nucleoporins with lamins (Smythe et al., 2000; Walther et al., 2001; Lussi et al., 2011), which form an elastic meshwork of filaments, known as the nuclear lamina (Dechat et al., 2010). Studies in flies, worms, and mice have demonstrated that the nuclear lamina is required to prevent NPC clustering (Lenz-Böhme et al., 1997; Sullivan et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2000), and fosters nuclear protein import (Busch et al., 2009). Lamin mutants also show aberrant nuclear shaping, altered chromosome organization, and changed gene expression (Andrés and González, 2009). Thus, the animal nuclear lamina is essential in nuclear architecture, chromosome organization, and transcriptional control (Dechat et al., 2010; Parnaik, 2008).

Lamin-encoding genes are absent from the genomes of all fungi and no biochemical evidence for a nuclear lamina exists (Strambio-de-Castillia et al., 1995, 1999; Melcer et al., 2007). Indeed, fungal nuclei are very small and extremely deformable (Straube et al., 2005), suggesting that they might not contain any supportive nuclear skeleton. NPCs are irregularly distributed within the fungal nuclear envelope (Winey et al., 1997; De Souza et al., 2004; Theisen et al., 2008) and they bind to interphase chromosomes via pore-associated adapter proteins (Galy et al., 2000; Liang and Hetzer, 2011). However, in contrast to animals the NPCs in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae show lateral movement within the nuclear envelope (Belgareh and Doye, 1997; Bucci and Wente, 1997). The mechanism underpinning this motility is not known, but it is tempting to speculate that it might be required for spatial organization of the NPCs across the nucleus.

In this article we address the mechanism and importance of motility of fungal NPCs. We demonstrate the occurrence of ATP-dependent NPC motility in the three model fungi Aspergillus nidulans, S. cerevisiae, and Ustilago maydis. Focusing on U. maydis we show that NPC motility is ATP dependent and requires microtubules (MTs) and the associated motors kinesin-1 and dynein. NPC motility moves chromosomes and prevents NPC clustering, thereby fostering protein import and export. These results suggest that active motor-driven transport spatially organizes NPCs and chromosomes in fungi.

Results

Fungal nuclear pores move directed and in an ATP-dependent fashion

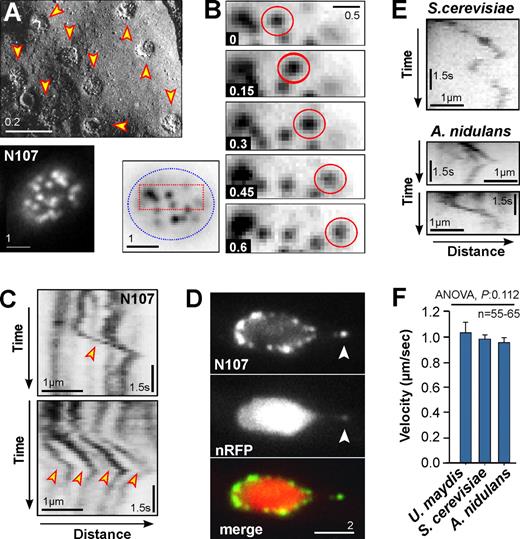

In U. maydis interphase cells NPCs were evenly distributed within the nuclear envelope (Fig. 1 A, top) at an average density of 12.8 ± 4.2 NPCs per 1 µm2 nuclear surface area (n = 13). To estimate the total number of pores per nucleus, we measured the dimensions of nuclei in cells expressing nlsRFP, a reporter protein consisting of a nuclear localization sequence and a triple tandem repeat of the monomeric RFP (Straube et al., 2005). We found that nuclei were 2.8 ± 0.5 µm long and 1.9 ± 0.2 µm wide (n = 50), which led to ∼200 NPCs per nucleus. To investigate the dynamic behavior of NPCs, we made use of fusion proteins of the nucleoporins Nup107, Nup133, and Nup214, and the integral pore membrane protein Pom152 that were fused to the green or red fluorescent proteins (Theisen et al., 2008; strain genotypes are listed in Table 1; for experimental usage of strains see Table S1). Nup107-GFP–labeled pores appeared to be evenly scattered within the nuclear envelope (Fig. 1 A, bottom) and usually repositioned in a random fashion (Video 1). Occasionally, NPCs showed rapid and directed motility (Fig. 1 B; Video 1, Video 2, red circles), which occurred at a velocity of ∼1 µm/s (1.07 ± 0.37, n = 65). This motility dissolved small NPC clusters that were infrequently formed (Video 2, right panels, arrowhead). In most cases single pores were transported (Fig. 1 C, top; Video 2, red circles), but occasionally coordinated motility of several NPCs was seen (Fig. 1 C, bottom; Video 2, red boxes), suggesting that NPCs might be connected by a scaffolding structure. The run length of NPC movements was normally restricted by the size of the nucleus and on average reached 1.18 ± 0.28 µm (n = 16). Occasionally, single NPCs seemed to be pulled away from the nucleus into the cytoplasm (Video 3), suggesting that their motility forms long nuclear extensions. To test this, we coexpressed Nup107-GFP with a triple mRFP tag that was targeted into the nucleus by an N-terminal nuclear localization and can only leave if the envelope becomes ruptured (nlsRFP; Straube et al., 2005). In these cells, NPC motility formed extended nlsRFP-containing extensions (Fig. 1 D; Video 4), demonstrating that the envelope was indeed intact despite its extreme deformation.

Motility of nuclear pores in U. maydis.U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of the GFP to the C terminus of the endogenous nucleoporin Nup107. NPCs move randomly within the nuclear envelope. Occasionally, rapid and directed motility is visible (red circle). The image sequence was taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.15 s for 11.87 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Motility of nuclear pores in U. maydis.U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of the GFP to the C terminus of the endogenous nucleoporin Nup107. NPCs move randomly within the nuclear envelope. Occasionally, rapid and directed motility is visible (red circle). The image sequence was taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.15 s for 11.87 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Directed motility of nuclear pores in U. maydis. U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of the GFP to the C terminus of the endogenous nucleoporin Nup107. Rapid and persistent motility of single NPCs (red circles) or of groups of NPCs (red boxes) is shown. Note that in one nucleus a cluster of NPCs moves (arrowhead). The motility sometimes dissolved these clusters (bottom right example, arrowheads). Image sequences were taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were every 0.15 s for 3.0 and 6.16 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Directed motility of nuclear pores in U. maydis. U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of the GFP to the C terminus of the endogenous nucleoporin Nup107. Rapid and persistent motility of single NPCs (red circles) or of groups of NPCs (red boxes) is shown. Note that in one nucleus a cluster of NPCs moves (arrowhead). The motility sometimes dissolved these clusters (bottom right example, arrowheads). Image sequences were taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were every 0.15 s for 3.0 and 6.16 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Directed motility of nuclear pores into the cytoplasm in U. maydis. U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of the GFP to the C terminus of the endogenous nucleoporin Nup107. Nuclear pores were often pulled away from the nucleus. Note that they return to the nucleus after short phases of motility. Image sequences were taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.15 s for 11.86 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Directed motility of nuclear pores into the cytoplasm in U. maydis. U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of the GFP to the C terminus of the endogenous nucleoporin Nup107. Nuclear pores were often pulled away from the nucleus. Note that they return to the nucleus after short phases of motility. Image sequences were taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.15 s for 11.86 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Formation of nuclear extensions by directed motility of nuclear pores in U. maydis. U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of the GFP fused to the C terminus of the endogenous nucleoporin Nup107 (green, N107) and a red fluorescent nuclear reporter protein (red, nlsRFP). Nuclear pore motility extends a nuclear tubule that contains a red fluorescent nuclear reporter. Note that the reporter protein does not leak out of the nucleus, indicating that the envelope remains intact during deformation. Image sequence was taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.3 s for 17.7 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Formation of nuclear extensions by directed motility of nuclear pores in U. maydis. U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of the GFP fused to the C terminus of the endogenous nucleoporin Nup107 (green, N107) and a red fluorescent nuclear reporter protein (red, nlsRFP). Nuclear pore motility extends a nuclear tubule that contains a red fluorescent nuclear reporter. Note that the reporter protein does not leak out of the nucleus, indicating that the envelope remains intact during deformation. Image sequence was taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.3 s for 17.7 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Motility of nuclear pores in fungi. (A) Freeze-fracture electron micrograph (top) and Nup107-GFP (N107; bottom) showing even distribution of NPCs in the nuclear envelope. Bars indicate micrometers. See also Video 1. (B) Image series showing directed motility of a NPC within the nuclear envelope. Bottom left image shows the nucleus from where the image series was taken (red box); the edge of the nucleus is indicated by a blue dotted line. Contrast was inverted. Time is given in seconds; bar indicates micrometers. See also Video 2. (C) Kymographs showing motility behavior of Nup107-GFP–labeled NPCs (N107). Rapid motility is indicated by arrowheads. Occasionally, several pores show coordinated motility (bottom). Contrast was inverted. Bars represent micrometers and seconds. See also Video 2. (D) Colocalization of Nup107-GFP (N107) and a nuclear reporter protein (nRFP). A NPC is pulled away from the nucleus, which extends the nucleus (arrowhead). See also Videos 3 and 4. (E) Kymographs showing motility behavior of NPCs in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae (labeled with Nup82-GFP) and the filamentous fungus A. nidulans (labeled with Nup133-GFP). Contrast was inverted. Bars represent micrometers and seconds. See also Videos 5 and 6. (F) Bar chart showing velocity of NPC motility in U. maydis, S. cerevisiae, and A. nidulans. One-way ANOVA testing showed no significant difference (P = 0.112). Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 55–65 measurements per bar).

Motility of nuclear pores in fungi. (A) Freeze-fracture electron micrograph (top) and Nup107-GFP (N107; bottom) showing even distribution of NPCs in the nuclear envelope. Bars indicate micrometers. See also Video 1. (B) Image series showing directed motility of a NPC within the nuclear envelope. Bottom left image shows the nucleus from where the image series was taken (red box); the edge of the nucleus is indicated by a blue dotted line. Contrast was inverted. Time is given in seconds; bar indicates micrometers. See also Video 2. (C) Kymographs showing motility behavior of Nup107-GFP–labeled NPCs (N107). Rapid motility is indicated by arrowheads. Occasionally, several pores show coordinated motility (bottom). Contrast was inverted. Bars represent micrometers and seconds. See also Video 2. (D) Colocalization of Nup107-GFP (N107) and a nuclear reporter protein (nRFP). A NPC is pulled away from the nucleus, which extends the nucleus (arrowhead). See also Videos 3 and 4. (E) Kymographs showing motility behavior of NPCs in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae (labeled with Nup82-GFP) and the filamentous fungus A. nidulans (labeled with Nup133-GFP). Contrast was inverted. Bars represent micrometers and seconds. See also Videos 5 and 6. (F) Bar chart showing velocity of NPC motility in U. maydis, S. cerevisiae, and A. nidulans. One-way ANOVA testing showed no significant difference (P = 0.112). Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 55–65 measurements per bar).

Strains and plasmids used in this paper

| Strain name | Genotype | Reference |

| FB2 | a2b2 | (Banuett and Herskowitz, 1989) |

| FB2N107G | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-egfp, bleR | This paper |

| FB2N107G_nR | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-gfp, bleR/pH_NLS3xRFP | (Theisen et al., 2008) |

| Nup82-GFP | MATa his3 ura3Δ0 leuΔ0 met15Δ0 NUP82-GFP::kanR | Invitrogen |

| CDS234 | Nup133-GFP::pyrGAf; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | (De Souza et al., 2004) |

| FB2nRFP_GT | a2b2 / pH_NLS3xRFP/pGFPTub1 | (Straube et al., 2005) |

| FB2N107G_RT | a2b2 Pnup107- nup107-gfp, bleR/pN_RFPTub1 | (Theisen et al., 2008) |

| FB2N133G | a2b2 Pnup133-nup133-gfp, natR | This paper |

| FB2N133G_nR | a2b2 Pnup133-nup133-GFP, natR/pC_NLS3xRFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_N133G_nR | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pnup133-nup133-GFP, natR/pC_NLS3xRFP | This paper |

| FB2Dyn2ts_N107G_nR | a2b2 dyn2ts natR, Pnup107-nup107-gfp, bleR/pC_NLS3xRFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_rDyn2_N133G | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pcrg-dyn2, bleR Pnup133-nup133-GFP, natR | This paper |

| FB2G3Dyn2_N107R | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-rfp, bleR Pdyn2-3xgfp-dyn2, hygR | This paper |

| FB2nR_H4G | a2b2 / pC_NLS3xRFP / pH4GFP | This paper |

| FB2N107G_rH4mCh | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-egfp, bleR/PrH4-cH | This paper |

| FB2N107R_nlsGFP | a2b2 Pnup107nup107-rfp, bleR/pnGFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_N107R_nG | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pnup107-nup107rfp, bleR/pnGFP | This paper |

| FB1rDyn2_N214R_nG | a1b1 Pcrg-dyn2, bleR Pnup214-nup214-rfp, hygR/pnGFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_rDyn2_N107R_nG | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pnup107nup-nup107rfp, bleR Pcrg-dyn2, natR/pnGFP | This paper |

| FB2N107R_NLS-NES-paG | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-rfp, bleR/pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_N107R_NLS-NES-paG | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pnup107-nup107rfp, bleR/pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | This paper |

| FB1rDyn2_P152R_NLS-NES-paG | a1b1 Pcrg-dyn2, bleR Ppom152-pom152-rfp, hygR/pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | This paper |

| FB1ΔKin1_rDyn2_P152R_NLS-NES-pG | a1b1 Δkin1::natR Pcrg-dyn2, bleR Ppom152-pom152-rfp, hygR/pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | This paper |

| FB2rN107_N214G | a2b2 Pnup214-nup214-gfp, hygR Pcrg-nup107, ble R | This paper |

| AB31nNudE_N133G | a2 PcrgbW2 PcrgbE1, Pnar-nde1, hygR, Pnup133-nup133-gfp, natR | This paper |

| pH_NLS3xRFP | Potef-gal4s-mrfp-mrfp-mrfp, hygR | (Straube et al., 2005) |

| PrH4-cH | Pcrg-his4-mcherry, cbxR | This paper |

| pGFPTub1 | Potef-gfp-tub1, cbxR | (Steinberg et al., 2001) |

| pN_RFPTub1 | Potef-2xmrfp-tub1, natR | (Theisen et al., 2008) |

| pERRFP | Potef-cals-mrfp-HDEL, cbxR | (Theisen et al., 2008) |

| pC_NLS3xRFP | Potef-gal4s-mrfp-mrfp-mrfp, cbxR | (Straube et al., 2005) |

| pnGFP | gal4(s)::egfp, cbx | (Straube et al., 2001) |

| pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | Potef-MARVS-NES-pagfp, cbxR | This paper |

| pH4GFP | Potef-his4-gfp, hygR | (Straube et al., 2001) |

| Strain name | Genotype | Reference |

| FB2 | a2b2 | (Banuett and Herskowitz, 1989) |

| FB2N107G | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-egfp, bleR | This paper |

| FB2N107G_nR | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-gfp, bleR/pH_NLS3xRFP | (Theisen et al., 2008) |

| Nup82-GFP | MATa his3 ura3Δ0 leuΔ0 met15Δ0 NUP82-GFP::kanR | Invitrogen |

| CDS234 | Nup133-GFP::pyrGAf; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | (De Souza et al., 2004) |

| FB2nRFP_GT | a2b2 / pH_NLS3xRFP/pGFPTub1 | (Straube et al., 2005) |

| FB2N107G_RT | a2b2 Pnup107- nup107-gfp, bleR/pN_RFPTub1 | (Theisen et al., 2008) |

| FB2N133G | a2b2 Pnup133-nup133-gfp, natR | This paper |

| FB2N133G_nR | a2b2 Pnup133-nup133-GFP, natR/pC_NLS3xRFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_N133G_nR | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pnup133-nup133-GFP, natR/pC_NLS3xRFP | This paper |

| FB2Dyn2ts_N107G_nR | a2b2 dyn2ts natR, Pnup107-nup107-gfp, bleR/pC_NLS3xRFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_rDyn2_N133G | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pcrg-dyn2, bleR Pnup133-nup133-GFP, natR | This paper |

| FB2G3Dyn2_N107R | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-rfp, bleR Pdyn2-3xgfp-dyn2, hygR | This paper |

| FB2nR_H4G | a2b2 / pC_NLS3xRFP / pH4GFP | This paper |

| FB2N107G_rH4mCh | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-egfp, bleR/PrH4-cH | This paper |

| FB2N107R_nlsGFP | a2b2 Pnup107nup107-rfp, bleR/pnGFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_N107R_nG | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pnup107-nup107rfp, bleR/pnGFP | This paper |

| FB1rDyn2_N214R_nG | a1b1 Pcrg-dyn2, bleR Pnup214-nup214-rfp, hygR/pnGFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_rDyn2_N107R_nG | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pnup107nup-nup107rfp, bleR Pcrg-dyn2, natR/pnGFP | This paper |

| FB2N107R_NLS-NES-paG | a2b2 Pnup107-nup107-rfp, bleR/pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | This paper |

| FB2ΔKin1_N107R_NLS-NES-paG | a2b2 Δkin1::hygR Pnup107-nup107rfp, bleR/pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | This paper |

| FB1rDyn2_P152R_NLS-NES-paG | a1b1 Pcrg-dyn2, bleR Ppom152-pom152-rfp, hygR/pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | This paper |

| FB1ΔKin1_rDyn2_P152R_NLS-NES-pG | a1b1 Δkin1::natR Pcrg-dyn2, bleR Ppom152-pom152-rfp, hygR/pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | This paper |

| FB2rN107_N214G | a2b2 Pnup214-nup214-gfp, hygR Pcrg-nup107, ble R | This paper |

| AB31nNudE_N133G | a2 PcrgbW2 PcrgbE1, Pnar-nde1, hygR, Pnup133-nup133-gfp, natR | This paper |

| pH_NLS3xRFP | Potef-gal4s-mrfp-mrfp-mrfp, hygR | (Straube et al., 2005) |

| PrH4-cH | Pcrg-his4-mcherry, cbxR | This paper |

| pGFPTub1 | Potef-gfp-tub1, cbxR | (Steinberg et al., 2001) |

| pN_RFPTub1 | Potef-2xmrfp-tub1, natR | (Theisen et al., 2008) |

| pERRFP | Potef-cals-mrfp-HDEL, cbxR | (Theisen et al., 2008) |

| pC_NLS3xRFP | Potef-gal4s-mrfp-mrfp-mrfp, cbxR | (Straube et al., 2005) |

| pnGFP | gal4(s)::egfp, cbx | (Straube et al., 2001) |

| pC_NLS-NES-paGFP | Potef-MARVS-NES-pagfp, cbxR | This paper |

| pH4GFP | Potef-his4-gfp, hygR | (Straube et al., 2001) |

a, b: mating type loci; P: promoter; -: fusion; hygR: hygromycin resistance; bleR: phleomycin resistance; natR: nourseothricin resistance; cbxR: carboxin resistance; ts: temperature-sensitive allele; /: ectopically integrated; crg: conditional arabinose-induced promoter; otef: constitutive promoter; nup107, nup133, nup214, nup84, NUP82: nucleoporins; pom152: integral pore membrane protein; HDEL: ER retention signal; egfp: enhanced GFP; rfp: monomeric RFP; mcherry: monomeric cherry, paGFP: photoactivatable GFP; dyn2: C-terminal half of the dynein heavy chain; dyn1: N-terminal half of the dynein heavy chain; tub1: α-tubulin; kin1: kinesin1; gal4s: nuclear localization signal; MARVS: nuclear localization signal; NES, nuclear export sequence of protein kinase Fuz7 (um01514); pyrGAf: pyrG gene of Aspergillus fumigatus; pyrG89: A. nidulans uridine/uracil auxotrophic marker; pyroA4: A. nidulans pyridoxine auxotrophic marker; wA3: A. nidulans mutant allele causing white conidia; argB2: A. nidulans arginine auxotrophic marker; nirA14: A. nidulans mutant allele preventing nitrate utilization; sE15: A. nidulans thiosulfate auxotrophic marker; MATa: S. cerevisiae mating locus; his3, ura3Δ0, leuΔ0, met15Δ: S. cerevisiae auxotrophic markers; kanR: kanmycin resistance.

We next set out to test whether directed NPC motility is found in other fungal species. To do this we investigated NPC behavior in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae (labeled with Nup82-GFP) and A. nidulans (labeled with Nup133-GFP; De Souza et al., 2004; strain provided by Dr. S. Osmani, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH). We observed directed motility of NPCs in both fungi (Fig. 1 E; Videos 5 and 6) at rates similar to U. maydis, indicating that the movements are motor driven (Fig. 1 F). Indeed, in all three fungi, NPC motility was abolished when ATP levels were depleted with cyanide m-chlorophenyl-hydrazone (Fig. S1, CCCP), an inhibitor that reversibly blocks cell respiration (Hirose et al., 1974; in Fig. S1 the kymographs show stationary signals as vertical lines). This effect was reversible and motility started again after washing with fresh medium (Fig. S1, Wash). Taken, together these results suggest that ATP-dependent directed NPC motility is a characteristic feature of the fungal nucleus.

Directed motility of nuclear pores requires MTs

In U. maydis, motility of NPCs often occurred along the same invisible track (Fig. 2 A; individual NPCs indicated by colored trajectories; total observation time 17.6 s), suggesting that NPC transport takes place along the cytoskeleton. Indeed, MTs are in close contact with the nucleus (Fig. 2 B), suggesting that they could potentially mediate bi-directional NPC motility. To test this hypothesis, we coexpressed Nup107-GFP and a fusion of α-tubulin and mRFP (mRFP-Tub1) and investigated NPC motility in these cells. We observed that NPCs moved along MTs, which was most clearly seen when NPCs were pulled away from the nucleus (Fig. 2 C, Video 7). To gain further support for a role of MTs in NPC motility, we treated Nup107-GFP–expressing cells with the benzimidazole drug benomyl at conditions that efficiently destroy MTs in U. maydis (Fuchs et al., 2005). In control cells incubated with the solvent DMSO, ∼40% of the nuclei showed directed motility of NPCs within a 20-s observation time (Fig. 2 D, DMSO). In the presence of 30 µM benomyl, motility was almost abolished (Fig. 2 D, Ben), whereas treatment with 10 µM of the actin inhibitor latrunculin A slightly enhanced NPC motility (Fig. 2 D, LatA). Taken together, these data provide strong evidence for a role of MTs in NPC motility. We next tested the importance of MT-dependent NPC motility on the overall arrangement and distribution of NPCs within the nuclear envelope. We photobleached Nup107-GFP in selected regions of the nucleus and observed the recovery of the fluorescence due to NPC migration in the presence of either benomyl or the solvent DMSO. After photobleaching, fluorescent NPCs migrated into the bleached area (Fig. 2 E, contrast was inverted) and there fluorescence within the bleached area was measured (Fig. 2 F, DMSO). In contrast, in the presence of the MT inhibitor benomyl, the NPCs did not move into the photobleached region (Fig. 2 E), and almost no fluorescent recovery was seen (Fig. 2 F, Ben). These data demonstrate that MT-dependent motility constantly rearranges NPCs within the nuclear envelope.

Motility of nuclear pores along microtubules.U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of GFP fused to the C terminus of the nucleoporin Nup107 (green, N107) and a fusion of RFP to α-tubulin (red, Tub1). NPCs move along MTs, which is best visible when pores are pulled into the cytoplasm. The image sequence was taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.25 s for 12.26 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Motility of nuclear pores along microtubules.U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of GFP fused to the C terminus of the nucleoporin Nup107 (green, N107) and a fusion of RFP to α-tubulin (red, Tub1). NPCs move along MTs, which is best visible when pores are pulled into the cytoplasm. The image sequence was taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.25 s for 12.26 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Nuclear pore motility is dependent on microtubules. (A) Graph showing trajectories of nuclear pore motility within a nucleus, observed over 17.2 s. Note that all NPCs within the field of observation were included. NPCs move along a single track, suggesting that one or few cytoskeletal fibers underlie this motility. (B) Colocalization of microtubules (labeled with GFP-α-tubulin, Tub1) and a nuclear reporter (nlsRFP). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Note that microtubules are in proximity with the nucleus. Bar represents micrometers. (C) Image series showing motility of a NPC (green, N107) along a mRFP-α-tubulin (red, Tub1) labeled microtubule (arrowhead). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. See also Video 7. (D) Bar chart showing the effect of cytoskeleton disrupting drugs on NPC motility. DMSO: the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide; Ben: the microtubule inhibitor benomyl; LatA: the F-actin inhibitor latrunculin A. **, P < 0.01. Bars represent mean ± SEM of three experiments and >130 analyzed nuclei. (E) Image series showing NPC motility into a photobleached area of the nucleus. In control cells (DMSO) NPCs rapidly migrate into the bleached zone (indicated by circle). This motility was not seen after 30 min incubation with the microtubule inhibitor (Benomyl). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. Contrast was inverted. (F) Graph showing recovery of average fluorescence intensity after photobleaching with a 405-nm laser pulse. DMSO: the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide; Ben: the microtubule inhibitor benomyl. Each data point represents mean ± SEM (n = 10). Note that transient pairing and clustering of NPCs made the measurement of pore numbers inaccurate; therefore, the recovery of the average intensity of Nup107-GFP fluorescence is given.

Nuclear pore motility is dependent on microtubules. (A) Graph showing trajectories of nuclear pore motility within a nucleus, observed over 17.2 s. Note that all NPCs within the field of observation were included. NPCs move along a single track, suggesting that one or few cytoskeletal fibers underlie this motility. (B) Colocalization of microtubules (labeled with GFP-α-tubulin, Tub1) and a nuclear reporter (nlsRFP). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Note that microtubules are in proximity with the nucleus. Bar represents micrometers. (C) Image series showing motility of a NPC (green, N107) along a mRFP-α-tubulin (red, Tub1) labeled microtubule (arrowhead). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. See also Video 7. (D) Bar chart showing the effect of cytoskeleton disrupting drugs on NPC motility. DMSO: the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide; Ben: the microtubule inhibitor benomyl; LatA: the F-actin inhibitor latrunculin A. **, P < 0.01. Bars represent mean ± SEM of three experiments and >130 analyzed nuclei. (E) Image series showing NPC motility into a photobleached area of the nucleus. In control cells (DMSO) NPCs rapidly migrate into the bleached zone (indicated by circle). This motility was not seen after 30 min incubation with the microtubule inhibitor (Benomyl). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. Contrast was inverted. (F) Graph showing recovery of average fluorescence intensity after photobleaching with a 405-nm laser pulse. DMSO: the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide; Ben: the microtubule inhibitor benomyl. Each data point represents mean ± SEM (n = 10). Note that transient pairing and clustering of NPCs made the measurement of pore numbers inaccurate; therefore, the recovery of the average intensity of Nup107-GFP fluorescence is given.

Nuclear pore motility is mediated by kinesin-1 and dynein

MTs are polar structures that elongate at their plus ends, whereas their minus ends are usually embedded at sites of nucleation. Molecular motors use this polarity, with kinesins moving toward plus ends and dynein transporting cargo to minus ends of MTs (Vale, 2003). Yeast-like cells of U. maydis contain long MTs that emanate from several cytoplasmic MT-organizing centers, located in the neck region between the mother and the daughter cell (Straube et al., 2003; Fink and Steinberg, 2006). Consequently, MT minus-ends are concentrated at the neck, whereas plus ends extend to the cell poles (Fig. 3 A; orientation of the MT is indicated by “+” and “−”). We found that NPCs moved either toward plus or minus ends, respectively (Fig. 3 B; Control), suggesting that NPC motility is a balanced process that is driven by opposing MT motors. To test this notion, we analyzed NPC motility in a temperature-sensitive dynein mutant (Dyn2ts; Wedlich-Söldner et al., 2002) and in a kin1-null mutant, in which the gene encoding kinesin-1 was deleted (ΔKin1; Lehmler et al., 1997). In both mutant strains, the overall motility of NPCs was significantly reduced (Fig. 3 C). In the absence of kinesin1, the remaining NPC movements were directed to the minus ends (Fig. 3 B; ΔKin1, to MINUS), and as a consequence pores clustered near the neck region (Fig. 3, D and E, ΔKin1; neck in Fig. 3 D indicated by asterisk). The opposite was found in the temperature-sensitive dynein mutant, where NPC motility to MT plus-ends dominated (Fig. 3 B, Dyn2ts) and pores clustered at the distal pole of the nuclei (Fig. 3, D and E, Dyn2ts; MT orientation indicated by “PLUS” and “MINUS”). To further investigate the role of motors in NPC motility, we set out to colocalize kinesin-1 and dynein with NPCs. Unfortunately, fluorescent GFP-kinesin-1 shows a strong cytoplasmic background (Straube et al., 2006), which made localization studies unreliable. However, we previously visualized individual dynein motors (Schuster et al., 2011) and therefore coexpressed a GFP3-labeled dynein heavy chain with red fluorescent Nup107. We found that dynein constantly traveled along MTs. Occasionally, it transiently bound to nuclear pores that subsequently moved toward MT minus-ends (Fig. 3 F; Video 8), but returned to the nucleus after dynein detached (Video 8, bottom). This behavior is reminiscent of the previously described transient interaction of dynein with early endosomes (Schuster et al., 2011). Finally, we investigated NPC motility in a conditional kinesin1/dynein double mutant in which dynein was depleted by growing cells in glucose-containing medium (see Materials and methods). These conditions resulted in multinucleated cells (Straube et al., 2001) that, compared with control cells, showed almost no directed NPC motility (Fig. 3 G). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that kinesin-1 and dynein mediate bi-directional NPC motility.

Colocalization of dynein (green, Dyn2) and NPCs (red, Nup107).U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of a triple GFP fused to the N terminus of the dynein heavy chain (green, GFP3-Dyn2) and a fusion of RFP to the C terminus of the nucleoprotein Nup107 (red, N107). Top movie panel: a dynein signal co-migrates with a moving NPC. Bottom movie panel: after detachment of dynein from a NPC, the pore returns to the nucleus, while the motor continues traveling. Image sequences were taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.3 s for 2.4 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Colocalization of dynein (green, Dyn2) and NPCs (red, Nup107).U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of a triple GFP fused to the N terminus of the dynein heavy chain (green, GFP3-Dyn2) and a fusion of RFP to the C terminus of the nucleoprotein Nup107 (red, N107). Top movie panel: a dynein signal co-migrates with a moving NPC. Bottom movie panel: after detachment of dynein from a NPC, the pore returns to the nucleus, while the motor continues traveling. Image sequences were taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.3 s for 2.4 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Molecular motors are necessary for the motility of nuclear pores. (A) Nuclear pores and microtubule orientation in a growing yeast-like cell of U. maydis. NPCs are labeled by Nup133-GFP (N133), the cell edge is shown in blue, and the orientation of the microtubules is indicated by “+” and “−”. Note that the microtubule-organizing centers are located in the neck region between the growing bud and the mother cell (Fink and Steinberg, 2006). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bar is given in micrometers. (B) Bar chart showing NPC motility toward the bud (to MINUS) or toward the distal cell pole (to PLUS) in control cells (Control), null mutants of kinesin-1 (ΔKin1), and temperature-sensitive dynein mutants at restrictive temperature (Dyn2ts). In control cells, NPC motility is a balanced process. Deleting the plus-motor kinesin-1 favors minus end–directed motility, whereas inactivation of the minus-motor dynein supports plus end–directed motion. Bars represent mean ± SEM of 3–6 experiments, covering 63–146 motility events in more than 50 nuclei. *, significant difference to wild-type at P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001. (C) Bar chart showing the relative number of nuclei with motility within 22 s observation time in control cells, kinesin-1 null mutants (ΔKin1), and conditional dynein mutants at restrictive conditions (Dyn2ts). Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3 experiments; each bar corresponds to 103–169 nuclei in G2 phase and in S phase). *, significant difference to wild-type in G phase at P < 0.05; **, significant difference to wild-type in G phase at P < 0.001). (D) Localization of Nup133-labeled nuclear pores (yellow in overlay with the red nucleus, labeled with nuclear RFP, red) in control cells, kinesin-1 null mutants (ΔKin1), and temperature-sensitive dynein mutants (Dyn2ts). Note that deletion of kinesin-1 or inactivation of dynein results in clustering of NPCs at the poles of the nucleus, which is most likely due to imbalanced NPC motility (see Fig. 4 B). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Asterisks indicate the neck region where microtubules are nucleated. Bar represents micrometers. (E) Localization of Nup133-labeled nuclear pores (yellow in overlay with the red nucleus, labeled with nuclear RFP, red) in control cells, kinesin-1 null mutants (ΔKin1), and temperature-sensitive dynein mutants (Dyn2ts). Microtubule orientation is indicated by “MINUS” and “PLUS”. Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bar represents micrometers. (F) Colocalization of Nup107-mRFP (red, N107) and triple GFP-labeled dynein heavy chain (green, Dyn2). Dynein colocalizes with a NPC that moves toward the bud (see also Video 8). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. (G) Bar chart showing the relative number of nuclei with motility within 12 s observation time in control cells and kinesin-1/dynein double mutants at restrictive conditions (ΔKin1Dyn2↓). Bars are given as mean ± SEM of the mean of three experiments (>90 nuclei per bar) and an observation time of 22.5 s per nucleus. ***, significant difference to wild-type at P < 0.0001.

Molecular motors are necessary for the motility of nuclear pores. (A) Nuclear pores and microtubule orientation in a growing yeast-like cell of U. maydis. NPCs are labeled by Nup133-GFP (N133), the cell edge is shown in blue, and the orientation of the microtubules is indicated by “+” and “−”. Note that the microtubule-organizing centers are located in the neck region between the growing bud and the mother cell (Fink and Steinberg, 2006). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bar is given in micrometers. (B) Bar chart showing NPC motility toward the bud (to MINUS) or toward the distal cell pole (to PLUS) in control cells (Control), null mutants of kinesin-1 (ΔKin1), and temperature-sensitive dynein mutants at restrictive temperature (Dyn2ts). In control cells, NPC motility is a balanced process. Deleting the plus-motor kinesin-1 favors minus end–directed motility, whereas inactivation of the minus-motor dynein supports plus end–directed motion. Bars represent mean ± SEM of 3–6 experiments, covering 63–146 motility events in more than 50 nuclei. *, significant difference to wild-type at P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001. (C) Bar chart showing the relative number of nuclei with motility within 22 s observation time in control cells, kinesin-1 null mutants (ΔKin1), and conditional dynein mutants at restrictive conditions (Dyn2ts). Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3 experiments; each bar corresponds to 103–169 nuclei in G2 phase and in S phase). *, significant difference to wild-type in G phase at P < 0.05; **, significant difference to wild-type in G phase at P < 0.001). (D) Localization of Nup133-labeled nuclear pores (yellow in overlay with the red nucleus, labeled with nuclear RFP, red) in control cells, kinesin-1 null mutants (ΔKin1), and temperature-sensitive dynein mutants (Dyn2ts). Note that deletion of kinesin-1 or inactivation of dynein results in clustering of NPCs at the poles of the nucleus, which is most likely due to imbalanced NPC motility (see Fig. 4 B). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Asterisks indicate the neck region where microtubules are nucleated. Bar represents micrometers. (E) Localization of Nup133-labeled nuclear pores (yellow in overlay with the red nucleus, labeled with nuclear RFP, red) in control cells, kinesin-1 null mutants (ΔKin1), and temperature-sensitive dynein mutants (Dyn2ts). Microtubule orientation is indicated by “MINUS” and “PLUS”. Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bar represents micrometers. (F) Colocalization of Nup107-mRFP (red, N107) and triple GFP-labeled dynein heavy chain (green, Dyn2). Dynein colocalizes with a NPC that moves toward the bud (see also Video 8). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. (G) Bar chart showing the relative number of nuclei with motility within 12 s observation time in control cells and kinesin-1/dynein double mutants at restrictive conditions (ΔKin1Dyn2↓). Bars are given as mean ± SEM of the mean of three experiments (>90 nuclei per bar) and an observation time of 22.5 s per nucleus. ***, significant difference to wild-type at P < 0.0001.

We next set out to get first insight into the physical linkage between the motors and the NPCs. In human HeLa cells, dynein is connected to NPCs via NudE and the Nup133–Nup107 complex (Bolhy et al., 2011). We tested for a similar dynein anchorage mechanism by depleting the U. maydis NudE homologue nde1 (um12335; for all gene entries see http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/genre/proj/ustilago) and Nup107, followed by investigating the effect on NPC motility. Depleting Nup107 led to NPC clustering (Fig. S5 A) and reduced NPC motility, whereas depletion of Nde1 had no effect (Fig. S5 B), indicating that the NudE is not linking dynein to NPCs.

Nuclear pores cluster in the absence of directed motility

The results described above suggested that bi-directional MT-based transport mediates the constant rearrangement of NPCs, resulting in an even distribution of nuclear pores. Indeed, when cells were treated with benomyl, which destroyed the MTs within 6 min (Fink and Steinberg, 2006), NPCs began to cluster after 10–15 min (Fig. S2) and clustering was dominating after 30 min of drug treatment (Fig. 4 A, compare Control and Benomyl). This suggests that NPC motility along MTs supports the even distribution of NPCs. We tested this hypothesis by analyzing NPC clustering in control cells and in the kinesin1/dynein double mutants. Indeed, deletion/inactivation of both motors resulted in NPC clustering (Fig. 4 A, B). We measured the fluorescence intensity of Nup133-GFP spots in these mutants, and estimated the number of nuclear pores in each signal (see Materials and methods). We found that in control cells most fluorescent signals NPCs represented 1 or 2 NPCs, whereas numerous NPCs aggregated in kinesn1/dynein double mutants (Fig. 4 C). Taken together, these results suggest that NPC motility is required to avoid NPC aggregation.

Clustering of nuclear pores occurs in the absence of microtubules and in kinesin-1/dynein double mutants. (A) Nup133-GFP–labeled nuclear pores in DMSO-treated cells (Control), cells treated with the microtubule inhibitor benomyl (30–60 min), and kinesin/dynein double mutants (ΔKin1Dyn2↓). In control cells the pores are evenly distributed within the nuclear envelope, whereas they aggregate in the absence of microtubules or in motor mutants. Aggregation is best seen in false-colored images that show signal intensity in a color code (right panels). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bars represent micrometers. (B) Freeze-fracture electron micrograph showing clustering of nuclear pores in kinesin/dynein double mutants (ΔKin1Dyn2↓). Arrowheads mark a NPC cluster. Bars represent micrometers. (C) Bar chart showing the distribution Nup133-GFP fluorescent intensity in Nup133-GFP signals as an estimate of nuclear pore numbers. Total number of analyzed signals is 109 (Control) and 108 (ΔKin1Dyn2↓) from a single experiment. NPC clustering was confirmed in three independent experimental repeats. Note that all measurements were done in top-views of the upper focal plane of the nuclei. (D) Distribution of nuclear pores (labeled with GFP-Nup82) in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae after 30 min treatment with the solvent DMSO and 10 µM of the actin inhibitor latrunculin A (LatA). NPCs form clusters (arrowheads). Note that NPC motility is also impaired (see Fig. S3). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bar represents micrometers.

Clustering of nuclear pores occurs in the absence of microtubules and in kinesin-1/dynein double mutants. (A) Nup133-GFP–labeled nuclear pores in DMSO-treated cells (Control), cells treated with the microtubule inhibitor benomyl (30–60 min), and kinesin/dynein double mutants (ΔKin1Dyn2↓). In control cells the pores are evenly distributed within the nuclear envelope, whereas they aggregate in the absence of microtubules or in motor mutants. Aggregation is best seen in false-colored images that show signal intensity in a color code (right panels). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bars represent micrometers. (B) Freeze-fracture electron micrograph showing clustering of nuclear pores in kinesin/dynein double mutants (ΔKin1Dyn2↓). Arrowheads mark a NPC cluster. Bars represent micrometers. (C) Bar chart showing the distribution Nup133-GFP fluorescent intensity in Nup133-GFP signals as an estimate of nuclear pore numbers. Total number of analyzed signals is 109 (Control) and 108 (ΔKin1Dyn2↓) from a single experiment. NPC clustering was confirmed in three independent experimental repeats. Note that all measurements were done in top-views of the upper focal plane of the nuclei. (D) Distribution of nuclear pores (labeled with GFP-Nup82) in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae after 30 min treatment with the solvent DMSO and 10 µM of the actin inhibitor latrunculin A (LatA). NPCs form clusters (arrowheads). Note that NPC motility is also impaired (see Fig. S3). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bar represents micrometers.

As part of this study we found that NPCs also move in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae (see above). We therefore set out to test if NPC motility is required to avoid NPC clustering in this budding yeast. First, we tested which cytoskeletal element supports NPC motility. We found that motility of NPCs is impaired in the presence of latunculin A (Fig. S3 B), suggesting that F-actin supports NPC motility in budding yeast. Indeed, LatA-treated cells showed strong NPC clustering (Fig. 4 D), whereas benomyl treatment neither affected NPC distribution nor NPC motility (Fig. S3). Thus, the mechanism of transport differs between U. maydis and S. cerevisiae. However, in both fungi the cytoskeleton-mediated NPC motility distributes nuclear pores and avoids clustering within the nuclear envelope.

NPC motility moves chromosomes within the nucleus

To obtain first insight into the role of NPC motility we quantified NPC motility in various cell cycle stages in U. maydis, which were identified by the morphology of the budding cells and the position of the nuclei (Fig. 5 A; Steinberg et al., 2001). We found that NPC motility was most prominent at the onset of mitosis (Fig. 5 B; prophase). In prophase, chromosomes move within the nuclear envelope (Straube et al., 2005), suggesting that NPC motility and chromosome motility could be related. Indeed, in animals and yeast cells, NPCs are physically linked to chromosomal DNA (Liang and Hetzer, 2011). To test whether NPC motility affects chromosome organization, we labeled chromatin by expressing GFP-tagged histone4 in nuclei that contained the nuclear reporter nlsRFP. After photobleaching parts of the nuclei we observed chromosomes moving into the darkened areas (Fig. 5 C, circle indicates bleached region; Video 9). We next tested if the reorganization of histone4-labeled chromosomes is ATP dependent. We found that depleting ATP by CCCP treatment abolished rearrangement of histone4 and significantly reduced chromosome reorganization (Fig. 5, D and E). This suggests that directed chromosome motility within the nucleus is a motor-driven process. We next coexpressed histone4-mCherry and Nup107-GFP and co-observed the NPCs and chromatin (Fig. 5 F, Video 10). Consistently, we found that chromosomes and NPCs co-migrated, suggesting that NPC motility rearranges interphase chromosomes. We conclude that chromosome motility is an active process in fungi that most likely involves active NPC transport.

Motility of chromosomes in U. maydis.U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of a GFP fused to the C terminus of histione4 (green, H4) and a red fluorescent nuclear marker protein (red, nlsRFP). Chromosomes move into the photobleached region (circle). Image series to the right is processed using Imaris software. The image sequence was taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Photobleaching was done using a VisiFRAP 2D system (Visitron Systems). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.3 s for 5.40 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Motility of chromosomes in U. maydis.U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of a GFP fused to the C terminus of histione4 (green, H4) and a red fluorescent nuclear marker protein (red, nlsRFP). Chromosomes move into the photobleached region (circle). Image series to the right is processed using Imaris software. The image sequence was taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Photobleaching was done using a VisiFRAP 2D system (Visitron Systems). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.3 s for 5.40 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Motility of NPCs and chromosomes in U. maydis.U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of a GFP fused to the C terminus of Nup107 (for better visualization given in red, N107) and the red fluorescent monomeric cherry protein fused to the C terminus of histone4 (for better visualization given in green, H4). Directed motility of pores and H4-positive chromatin is indicated by arrowheads. Image sequences were taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.45 s for 4.05 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Motility of NPCs and chromosomes in U. maydis.U. maydis cells expressing a fusion of a GFP fused to the C terminus of Nup107 (for better visualization given in red, N107) and the red fluorescent monomeric cherry protein fused to the C terminus of histone4 (for better visualization given in green, H4). Directed motility of pores and H4-positive chromatin is indicated by arrowheads. Image sequences were taken using epifluorescence microscopy (inverted microscope [model IX81; Olympus] equipped with a VS-LMS4 Laser-Merge-System [Visitron Systems]). Cells were observed at room temperature and frames were taken every 0.45 s for 4.05 s. Time is given in seconds:milliseconds; the bar represents micrometers.

Chromosome and NPC movements. (A) Yeast-like cells of U. maydis at various cell cycle stages. The position of the nucleus is marked by a fluorescent nuclear reporter (nRFP, red). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. The bar represents 5 µm. (B) Bar chart showing NPC motility rates in U. maydis at various cell cycle stages. Bars are given as mean ± SEM (n = 70–169 cells). *, significant difference to S phase at P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001. (C) Image series showing motility of histone4-GFP (green, H4) labeled chromosomes. The nuclear interior was visualized by the reporter protein nlsRFP (nRFP, red). The first frame shows a partially photobleached nucleus (bleach area is indicated by yellow circle and “Bleach”). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Note that right image series is a more processed version of the right series which was modified using Imaris software. See also Video 9. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. (D) Rearrangement of chromosomes (labeled with histone4-GFP, green, H4) in the presence of the solvent DMSO and the ionophore CCCP that leads to depletion of cellular ATP. Immobile DNA appears yellow in the overlay (merge) of two images at t = 0 and t = 1 s. Deconvolved images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. (E) Bar chart showing the degree of colocalization of chromosomes after 1 s CCCP treatment. Rearrangement is significantly reduced when ATP is depleted. Bars are given as mean ± SEM (n = 50 from a single representative experiment out of two repeats). ***, significant difference at P < 0.0001. (F) Image series showing motility of histone4-mCherry–labeled chromosomes (green) and Nup107-GFP nuclear pores (red). A nuclear pore moves together with a chromosome (arrowheads). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. See also Video 10. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers.

Chromosome and NPC movements. (A) Yeast-like cells of U. maydis at various cell cycle stages. The position of the nucleus is marked by a fluorescent nuclear reporter (nRFP, red). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. The bar represents 5 µm. (B) Bar chart showing NPC motility rates in U. maydis at various cell cycle stages. Bars are given as mean ± SEM (n = 70–169 cells). *, significant difference to S phase at P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001. (C) Image series showing motility of histone4-GFP (green, H4) labeled chromosomes. The nuclear interior was visualized by the reporter protein nlsRFP (nRFP, red). The first frame shows a partially photobleached nucleus (bleach area is indicated by yellow circle and “Bleach”). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Note that right image series is a more processed version of the right series which was modified using Imaris software. See also Video 9. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. (D) Rearrangement of chromosomes (labeled with histone4-GFP, green, H4) in the presence of the solvent DMSO and the ionophore CCCP that leads to depletion of cellular ATP. Immobile DNA appears yellow in the overlay (merge) of two images at t = 0 and t = 1 s. Deconvolved images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers. (E) Bar chart showing the degree of colocalization of chromosomes after 1 s CCCP treatment. Rearrangement is significantly reduced when ATP is depleted. Bars are given as mean ± SEM (n = 50 from a single representative experiment out of two repeats). ***, significant difference at P < 0.0001. (F) Image series showing motility of histone4-mCherry–labeled chromosomes (green) and Nup107-GFP nuclear pores (red). A nuclear pore moves together with a chromosome (arrowheads). Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. See also Video 10. Time is given in seconds; bar represents micrometers.

Nuclear pore clustering affects chromosome distribution

Our results indicated that NPC motility is linked to chromosome motions within the nucleus. This suggested a physical connection between the pores and chromatin and raised the possibility that NPC clustering affects chromosome arrangement. To test whether the absence of NPC motility affects chromosome organization, we coexpressed Nup107-GFP and histone4-mCherry and observed the organization of histone4-labeled chromosomes in DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 6 A, Control), and after 30 min exposure to benomyl (Fig. 6 A, Benomyl). We found that in the absence of MTs chromosomes concentrated at the periphery of the nucleus and often near the NPC clusters (Fig. 6, A and B). Impairment of NPC motility therefore results in NPC aggregation, which in turn leads to aberrant chromosome organization.

Reorganization of chromosomes in the absence of microtubules. (A) Colocalization of chromosomes, labeled with histone4-mCherry (for better visualization given in green) and Nup107-GFP nuclear pores (for better visualization given in red) in cells treated with the solvent DMSO (Control) and with 30 µM benomyl (Benomyl). Note that chromosomes concentrate at the cell periphery. Images were subject to deconvolution and adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bar represents micrometer. (B) 3D intensity maps showing the distribution of chromatin (labeled with histone4-GFP) within nuclei of cells treated with DMSO (Control) and benomyl (Benomyl). The intensity maps were generated from 26–30 randomly taken nuclei. In the absence of microtubules, the chromosomes tend to cluster at the periphery of the nucleus.

Reorganization of chromosomes in the absence of microtubules. (A) Colocalization of chromosomes, labeled with histone4-mCherry (for better visualization given in green) and Nup107-GFP nuclear pores (for better visualization given in red) in cells treated with the solvent DMSO (Control) and with 30 µM benomyl (Benomyl). Note that chromosomes concentrate at the cell periphery. Images were subject to deconvolution and adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Bar represents micrometer. (B) 3D intensity maps showing the distribution of chromatin (labeled with histone4-GFP) within nuclei of cells treated with DMSO (Control) and benomyl (Benomyl). The intensity maps were generated from 26–30 randomly taken nuclei. In the absence of microtubules, the chromosomes tend to cluster at the periphery of the nucleus.

Clustering of nuclear pores in motor mutants leads to defects in nuclear transport

NPCs mediate transport between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and we speculated that their clustering might impede this process. To test for defects in nucleocytoplasmic transport we made use of GFP, which has a diameter of ∼5 nm and diffuses only slowly through the 2.6-nm channels of the NPC (Ribbeck and Görlich, 2001; Mohr et al., 2009). To foster import of the reporter, we fused a nuclear localization signal to GFP, which turned the reporter protein into a cargo for transport receptors. Such an NLS-GFP reporter was previously used to quantify nuclear import in S. cerevisiae and HeLa cells (Timney et al., 2006; Busch et al., 2009). Before bleaching, the NLS-GFP import reporter accumulated in the nucleus of control cells (Fig. 7 A, indicated by “−1”). After photobleaching, however, the NLS-GFP fluorescence recovered rapidly (Fig. 7 B; time is given in minutes after photobleaching), reaching ∼45% of the initial nuclear fluorescence after 10 min. This recovery rate after 10 min was significantly reduced in kinesin-1, dynein, or in double mutants (P < 0.01–0.0001; Fig. 7 C), indicating a defect in nuclear import, which we reasoned might be due to clustering of the NPCs. However, it was recently reported that MTs also fulfill a role in delivering proteins to the nuclear pore (Roth et al., 2011), raising the possibility that the observed import defect is due to reduced MT-dependent trafficking of import cargo to the NPC. We tested this possibility by placing Nup107-RFP and NLS-GFP–expressing cells onto benomyl-containing agar. This treatment depolymerized MTs within 6–10 min (Fink and Steinberg, 2006; our control experiments), whereas clustering of NPCs occurred after ∼10–15 min (Fig. S2). We measured fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of NLS-GFP in the 5-min time window when MTs were disrupted but NPC clustering was not yet visible. In control experiments the solvent DMSO was used, which did not affect import of our marker proteins (Fig. 7 B). We found that nuclear import was not impaired, despite the fact that MTs were absent (Fig. 7 C; DMSO, 10 min, vs. Ben, 10 min; P value after t test indicated above bars). This suggests that the import defect in the motor mutants is not simply due to impaired MT-based delivery of NLS-GFP to the nuclear pores, but instead arises due to NPC clustering.

NPC clustering impairs nuclear import and export of GFP-reporter proteins. (A) Image series showing import of NLS-GFP after photobleaching. Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in minutes, the bar represents micrometers. (B) Graph showing fluorescent recovery of NLS-GFP in the nucleus after photobleaching in untreated cells and in the presence of the solvent DMSO. Data points represent mean ± SEM (n = 10). (C) Bar chart showing fluorescent recovery of NLS-GFP in control cells at 10 min after photobleaching in motor mutants and after 10 min of benomyl treatment, but before NPC clustering is visible. Clustering of nuclear pores due to deleting or inactivation of motors significantly affects import, whereas disruption of microtubules before clustering of NPCs has no significant effect on NLS-GFP import. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 31–58 per bar). **, significant difference to control at P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001. (D) Image series showing export of NLS-NES-paGFP after photoactivation. Decay of the export reporter is shown in false-colored images, where signal intensity is given in colors. Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in minutes, the bar represents micrometers. (E) Graph showing decay of fluorescent NLS-NES-paGFP after photoactivation in the nucleus in untreated cells and in the presence of the solvent DMSO. Data points represent mean ± SEM (n = 10). (F) Bar chart showing decrease of NLS-NES-paGFP in control cells, motor mutants, and after 10 min of benomyl treatment in cells that do not show clustering of the NPCs. Clustering of nuclear pores due to deleting or inactivation of motors slows down export of the reporter, whereas disruption of microtubules before clustering of NPCs has no significant effect on NLS-NES-paGFP export. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 31–40 per bar). ***, significant difference to control at P < 0.0001.

NPC clustering impairs nuclear import and export of GFP-reporter proteins. (A) Image series showing import of NLS-GFP after photobleaching. Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in minutes, the bar represents micrometers. (B) Graph showing fluorescent recovery of NLS-GFP in the nucleus after photobleaching in untreated cells and in the presence of the solvent DMSO. Data points represent mean ± SEM (n = 10). (C) Bar chart showing fluorescent recovery of NLS-GFP in control cells at 10 min after photobleaching in motor mutants and after 10 min of benomyl treatment, but before NPC clustering is visible. Clustering of nuclear pores due to deleting or inactivation of motors significantly affects import, whereas disruption of microtubules before clustering of NPCs has no significant effect on NLS-GFP import. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 31–58 per bar). **, significant difference to control at P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001. (D) Image series showing export of NLS-NES-paGFP after photoactivation. Decay of the export reporter is shown in false-colored images, where signal intensity is given in colors. Images were subject to adjustment in brightness, contrast, and gamma settings. Time is given in minutes, the bar represents micrometers. (E) Graph showing decay of fluorescent NLS-NES-paGFP after photoactivation in the nucleus in untreated cells and in the presence of the solvent DMSO. Data points represent mean ± SEM (n = 10). (F) Bar chart showing decrease of NLS-NES-paGFP in control cells, motor mutants, and after 10 min of benomyl treatment in cells that do not show clustering of the NPCs. Clustering of nuclear pores due to deleting or inactivation of motors slows down export of the reporter, whereas disruption of microtubules before clustering of NPCs has no significant effect on NLS-NES-paGFP export. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 31–40 per bar). ***, significant difference to control at P < 0.0001.

If uneven NPC distribution underlies the reduced import of NLS-GFP reporter protein, we expected to find a similar reduction in protein export from the nucleus. To test this, we generated an export reporter construct. This consisted of a previously published nuclear localization signal (Straube et al., 2005) fused to a nuclear export sequence, which we identified by comparing a published MAP-kinase export signal (Henderson and Eleftheriou, 2000) with the homologous protein in U. maydis (um01514). This signal sequence was fused to photo-activatable GFP, resulting in the reporter protein NLS-NES-paGFP. The reporter protein concentrated in the nucleus and became visible after a laser pulse (Fig. 7 D, indicated by “−1”; images are false colored to better visualize differences in intensity). Shortly after photo-activation, the signal decreased due to export of the fluorescent reporter (Fig. 7, E and F). We subsequently expressed NLS-NES-paGFP in control cells and in each motor mutant and monitored the loss in fluorescence due to protein export at 10 min after photo-activation (see Materials and methods). We found a significantly reduced export of NLS-NES-paGFP in all motor mutants (Fig. 7 F). Nuclear export was normal in the presence of DMSO (Fig. 7 E) and was unaffected by disruption of MTs by benomyl at times when NPC clustering was not yet visible (Fig. 7 F; DMSO, 10 min, vs. Ben, 10 min; P value after t test indicated above bars). This indicates that the observed defect in nuclear export, similar to the reduced nuclear import rate (see above), was not due to impaired transport along MTs. Finally, we tested if the observed import/export defects are due to a general malfunction of the NPCs caused by the disruption of MTs (for example by plugging the pores due to an accumulation of cargo or by a structural change of the NPC). We treated cells with benomyl for up to 1 h and measured the nuclear import and export over a period of 10 min. We found no change in the rate of bi-directional transport across the NPC (Fig. S4). This argues that the nuclear pores do not change in their transport capacity with time in benomyl. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that MT-based NPC motility prevents pore and chromosome aggregation, thereby allowing efficient transport between the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

Discussion

Fungal NPCs undergo motor-dependent directed motility

In animal cells, NPCs are nonmotile (Daigle et al., 2001; Rabut et al., 2004; Dultz and Ellenberg, 2010) and are usually evenly distributed within the nuclear envelope, due to an interaction with the nuclear lamina (Walther et al., 2001). In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, the filamentous fungus A. nidulans, and the dimorphic fungus U. maydis, NPCs are also scattered over the surface of the entire nucleus (Doye et al., 1994; Winey et al., 1997; De Souza et al., 2004; Theisen et al., 2008), but in contrast to animals they show lateral ATP-dependent movements. A dynamic behavior of NPCs was first described in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae (Belgareh and Doye, 1997; Bucci and Wente, 1997). We show here that NPC motility in budding yeast requires the F-actin cytoskeleton, whereas the same process is MT based in U. maydis. However, in both fungi the absence of directed NPC motility causes the pores to aggregate. This indicates that the machinery for NPC transport could differ between fungal species, but that the process of NPC motility is conserved and ensures even distribution of NPCs in the fungal nuclear envelope.

NPC motility is mediated by molecular motors

One of the principal findings of this study is that NPC motility in U. maydis depends on kinesin-1 and dynein. These counteracting motors are known to be transporters of membrane-bound cargo (Vale, 2003), such as secretory vesicles in U. maydis (Schuster et al., 2012). Therefore, a role for these motors in motility of NPCs is unexpected. The question arises how the pores are connected to the motor proteins. In human cells, the protein BICD2 links NPCs to kinesin-1 and dynein (Splinter et al., 2010) and the nuclear nesprin Syne-1 interacts with kinesin motor proteins (Fan and Beck, 2004). However, the genome of U. maydis does not contain BICD2 or Syne-1 homologues, ruling out this mechanism of motor anchorage. In HeLa cells, NudE links dynein to the Nup133/Nup107 complex (Bolhy et al., 2011). Indeed, Nup107 is required for NPC motility in U. maydis, but NudE is not involved. Thus, the physical link to the motor proteins remains to be discovered.

It was shown in numerous cell systems that NPCs have a tendency to aggregate, which in animal cells is prevented by anchorage to the nuclear lamina (Lenz-Böhme et al., 1997; Sullivan et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2000). Our data demonstrate that in fungi MT-based motor-driven motility of NPCs ensures random distribution of pores, but how is this achieved? It was recently shown that molecular motors oppose each other in a stochastic “tug-of-war” (Müller et al., 2008), thereby ensuring bi-directional motility of their membranous cargo (Soppina et al., 2009; Hendricks et al., 2010). In U. maydis, dynein opposes kinesin-3 by transiently binding and unbinding to early endosomes, thereby causing stochastic reversal of transport direction (Schuster et al., 2011). A similar transient interaction of dynein with NPCs causes random movements of pores, which tears NPC clusters apart (see Video 2, bottom right, arrowheads). This transient interaction of motors with the NPCs also explains why directed NPC motility is rare (see Video 1).

NPC motility organizes the genomic DNA

We have shown here that histone4-GFP–labeled chromosomes move within the fungal nucleus, and this motility depends on ATP and MTs. In C. elegans, the KASH protein UNC-83 links the outer nuclear membrane to the motors kinesin-1 and dynein (Fridolfsson and Starr, 2010; Fridolfsson et al., 2010) and transmits force into the nucleus via a SUN protein in the inner nuclear membrane (Starr and Fridolfsson, 2010). The genome of U. maydis contains a hypothetical transmembrane containing SUN protein (um01479.1), which shares sequence similarity with UNC-84. However, we were not able to identify a putative KASH protein, though these are not strongly conserved and therefore difficult to recognize (Starr, 2009). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the observed chromosome motility is due to an interaction of motors with so-far unidentified SUN/KASH proteins in the nuclear envelope, the colocalization of moving NPCs and chromosomes strongly suggests that both motility events are linked. Indeed, SUN proteins can interact with the NPC (Liu et al., 2007), raising the possibility that such SUN/KASH proteins mediate the interaction of chromosomes, NPCs, and the cytoskeleton. Alternatively, the NPC might directly interact with promoter regions (Schmid et al., 2006). Taken together, it seems likely that constant motor-dependent, directed NPC motility rearranges the physical organization of chromosomes. This might enhance contact transcription or might facilitate diffusion within the nucleus.

Inhibition of NPC motility inhibits nucleoplasmic transport

Intranuclear transport of mRNA and proteins is most likely governed by diffusion (Politz et al., 1999; Politz and Pederson, 2000; Shav-Tal et al., 2004; Gorski et al., 2006). This passive process distributes imported proteins or delivers mRNA–protein complexes to the NPCs. At first glance it therefore does not seem surprising that NPC clustering is correlated with impaired import and export of GFP reporter proteins in U. maydis and in animal cells (this paper; Busch et al., 2009). However, diffusion within the nucleus is very rapid and export of mRNA is not restricted to neighboring NPCs, but instead occurs at all available pores (Shav-Tal et al., 2004; Gorski et al., 2006). Considering this and the fact that fungal nuclei are small, it is unlikely that the increased distance between genes and the NPCs accounts for the observed defects in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Thus, the question remains, why NPC clustering in motor mutants cause such a significant reduction in bi-directional nucleoplasmic transport? We have shown here that NPCs and chromosomes move together and that clustering of NPCs results in alteration of global chromatin organization. In animal cells, diffusion within the nucleus is restricted to chromatin-free channels that are thought to ensure continuous travel of nuclear export cargo toward the NPC (Lawrence et al., 1989; Mor et al., 2010). Indeed, when the organization of the chromatin is altered due to ATP depletion, intranuclear mRNA/protein mobility is reduced by half (Shav-Tal et al., 2004). This result raises the possibility that aberrant chromatin organization and rearrangement in the motor mutants disturbs efficient intranuclear diffusion and underlies the defects in nucleocytoplasmic protein exchange.

Conclusion

The nuclear lamina in animal cells provides mechanical stability and is involved in chromatin organization and transcriptional regulation (Parnaik, 2008; Andrés and González, 2009). It also interacts with nucleoporins and anchors NPCs to control their spatial organization (Fiserova and Goldberg, 2010). This is illustrated by the fact that NPCs cluster in lamin mutants in D. melanogaster, C. elegans, and mice (Lenz-Böhme et al., 1997; Sullivan et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2000), which results in defects in nucleoplasmic transport (Busch et al., 2009). Lamins appear to constitute a new innovation in metazoa that were most likely acquired by horizontal gene transfer from prokaryotic cells (Mans et al., 2004). Consequently, most lower eukaryotes do not possess a nuclear lamina (Melcer et al., 2007). An exception is the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, which contains the protein NE81, which participates in the formation of a nuclear lamina in this protist (Krüger et al., 2012). However, NE81 lacks conserved organizational features of lamins and is therefore considered a “lamin-like” protein, suggesting that amoeba independently invented a nuclear lamina. In contrast, fungi do not possess a nuclear lamina, and we have shown here that NPC motility participates in distributing their NPCs and in organizing their chromosomes. Defects in active NPC transport cause pore clustering, local aggregation of chromatin, and defects in nucleocytoplasmic transport. The latter is most likely a consequence of impaired diffusion through the unorganized chromatin (Fig. 8). It is also conceivable that the absence of force exerted on the nucleus impacts on gene organization and DNA transcription (Dahl et al., 2008). However, experimental evidence for a role of NPC motility in fungal transcription is missing. Taken together, we conclude that active motor-driven transport performs nuclear lamina functions in organizing the fungal nucleus.

Working model of the role of NPC motility in organizing chromosomes and mediating nucleoplasmic transport. (A) Nuclear organization in a wild-type cell. Chromosomes are constantly rearranged by NPC motility. This results in an even distribution of the NPCs. Import and export cargo diffuses through channels between the chromosomes. For sake of simplicity only export cargo is indicated. (B) Nuclear organization in a mutant defective in kinesin-1 and dynein. NPCs are no longer transported along microtubules. As a consequence they form clusters that concentrate the attached chromosomes at the cell periphery. This blocks diffusion channels between chromosomes, which in turn impairs nucleoplasmic transport. Note that the adapters between the motors and the NPC are not known (?).

Working model of the role of NPC motility in organizing chromosomes and mediating nucleoplasmic transport. (A) Nuclear organization in a wild-type cell. Chromosomes are constantly rearranged by NPC motility. This results in an even distribution of the NPCs. Import and export cargo diffuses through channels between the chromosomes. For sake of simplicity only export cargo is indicated. (B) Nuclear organization in a mutant defective in kinesin-1 and dynein. NPCs are no longer transported along microtubules. As a consequence they form clusters that concentrate the attached chromosomes at the cell periphery. This blocks diffusion channels between chromosomes, which in turn impairs nucleoplasmic transport. Note that the adapters between the motors and the NPC are not known (?).

Materials and methods

Strains

To observe nuclear pores, the plasmids pN107G and pN133G (Theisen et al., 2008) were transformed into U. maydis strain FB2, resulting in strains FB2N107G and FB2N133G. For colocalization of NPC and the nucleus in wild-type and motor mutant strains, first the plasmid pN133G (Theisen et al., 2008) was introduced into strain FB2ΔKin1 (Lehmler et al., 1997), resulting in strain FB2ΔKin1_N133G. To visualize nuclear pore distribution in dynein mutants, plasmid pDyn2ts (Wedlich-Söldner et al., 2002) was transformed into FB2 to generate a temperature-sensitive dynein mutant. This was followed by transformation of plasmid pN107G, which resulted in strain FB2_Dyn2ts_N107G. Next, the nuclear marker plasmid pC_NLS3xRFP (Straube et al., 2005) was introduced to create strains FB2N133G_nR, FB2ΔKin1_N133G_nR, and FB2_Dyn2ts_N107G_nR. To study the effect of the loss of kinesin-1 and dynein activity on NPC motility, the plasmid prDyn2 (Straube et al., 2001) was transformed into strain FB2ΔKin1_N133G, resulting in strain FB2Δkin1_rDyn2_N133G.

Motility of chromosomes was observed in strain FB2nR-H4G. For this, plasmid pH4GFP (Straube et al., 2005) was introduced into strain FB2nRFP3 (Straube et al., 2005). To investigate chromosome and NPC motility, plasmid prH4-cH was introduced into strain FB2N107G. For colocalization of dynein with the NPC, plasmid pN107R was transformed in strain FB2 followed by a second transformation of plasmid p3GDyn2 (Lenz et al., 2006), resulting in strain FB2G3Dyn2_N107R.

To generate strains for nuclear import measurements of NLS-GFP, plasmid pN107R was transformed into strains FB2 and FB2ΔKin1, resulting in strains FB2N107R and FB2Δkin1_N107R. Plasmid pN214R (Theisen et al., 2008) was transformed in strain FB1rDyn2 (Straube et al., 2001), resulting in strain FB1rDyn2_N214R. Subsequently, plasmid pnGFP (Straube et al., 2001) was introduced into the strains FB2N107R, FB2Δkin1_N107R, and FB1rDyn2_N214R, resulting in strains FB2N107R_nG, FB2ΔKin1_N107R_nG, and FB1rDyn2_N214R_nG, respectively. Finally, plasmid pNrDyn2 was transformed into strain FB2ΔKin1_N107R_nG, resulting in strain FB2Δkin1_rDyn2_N107R_nG.