Two major protein recycling pathways have emerged as key regulators of enduring forms of synaptic plasticity, such as long-term potentiation (LTP), yet how these pathways are recruited during plasticity is unknown. Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI(3)P) is a key regulator of endosomal trafficking and alterations in this lipid have been linked to neurodegeneration. Here, using primary hippocampal neurons, we demonstrate dynamic PI(3)P synthesis during chemical induction of LTP (cLTP), which drives coordinate recruitment of the SNX17–Retriever and SNX27–Retromer pathways to endosomes and synaptic sites. Both pathways are necessary for the cLTP-dependent structural enlargement of dendritic spines and act in parallel by recycling distinct sets of cell surface proteins at synapses. Importantly, preventing PI(3)P synthesis blocks synaptic recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27, decreases cargo recycling, and blocks LTP in cultured neurons and hippocampal slices. These findings provide mechanistic insights into the regulation of endocytic recycling at synapses and define a role for dynamic PI(3)P synthesis in synaptic plasticity.

Introduction

Neuronal synapses have a rich complement of cell surface proteins that are dynamically regulated both by posttranslational modification (PTM) and by membrane trafficking. Protein endocytosis, endosomal sorting, and recycling back to the plasma membrane are critical for synaptic functions (Diering and Huganir, 2018; van Oostrum et al., 2020). As such, defects in these sorting mechanisms are associated with deficits in synaptic plasticity, synapse loss, and neurodegeneration (Saitoh, 2022; McDonald, 2020). Much of what we know about endocytic recycling in neurons has come from studies focused on the SNX27–Retromer pathway (Wang et al., 2013; Hussain et al., 2014; Loo et al., 2014; McMillan et al., 2021). A distinct, parallel SNX17–Retriever recycling pathway was recently discovered in non-neuronal cells (McNally et al., 2017), and in neurons, this pathway also plays a key role in regulating synapse function and plasticity (Rivero-Ríos et al., 2023). However, it is not yet known how specific patterns of neuronal activity engage these recycling pathways and to what extent upstream signals drive a coordinated or independent activation of each.

In non-neuronal cells, SNX17 defines a major endomembrane recycling pathway responsible for the recycling of over 120 cell surface proteins from endosomes to the plasma membrane. SNX17 cargoes include numerous cell adhesion proteins, signaling receptors, and solute transporters (McNally et al., 2017). SNX17-dependent recycling requires the Retriever complex (VPS35L, VPS26C, and VPS29), the CCC complex (COMMD/CCDC22/CCDC93), and the actin-regulatory WASH complex (Chen et al., 2019; McNally and Cullen, 2018; Simonetti and Cullen, 2019; Wang et al., 2018). While most neuronal SNX17 cargoes remain unidentified, our findings show that the role of SNX17 in long-term potentiation (LTP) is mediated, at least in part, by promoting the recycling of the adhesion protein β1-integrin (Rivero-Ríos et al., 2023). β1-integrin is a key regulator of synaptic function and plasticity. It localizes to postsynaptic sites in hippocampal neurons and influences cytoskeletal organization, dendritic spine maturation, and synaptic transmission (Babayan et al., 2012; Bourgin et al., 2007; Chan et al., 2006; Chun et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2006; Kramár et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016; Mortillo et al., 2012; Ning et al., 2013; Orr et al., 2022; Warren et al., 2012; Webb et al., 2007).

Similarly, SNX27 recycles more than 200 cell surface proteins in neurons (McMillan et al., 2021). SNX27 displays high sequence homology with SNX17 but also harbors a PDZ domain for cargo binding. This unique PDZ domain directly interacts with C-terminal PDZ-binding motifs present in many neuronal surface proteins and is critical for the selective retrieval and recycling of SNX27-specific cargoes (Steinberg et al., 2013). Neuronal SNX27 cargoes include key receptors, such as α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic (AMPA)-type glutamate receptors (Loo et al., 2014; McMillan et al., 2021), β-adrenergic receptors (Lauffer et al., 2010; Temkin et al., 2011), Kir3 potassium channels (Lunn et al., 2007), the 5-hydroxytryptamine 4a receptor (Joubert et al., 2004), and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor 2C (Cai et al., 2011). SNX27 regulates cargo recycling by engaging with the Retromer complex (VPS35, VPS26A/B, and VPS29), a SNX–Bin/amphiphysin/Rvs dimer (SNX1/2 in complex with SNX5/6), and the WASH complex (Steinberg et al., 2013; Gallon et al., 2014; Harbour et al., 2012; Simonetti and Cullen, 2019; Mao et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2012; Yong et al., 2020; Kovtun et al., 2018; Yong et al., 2021). Similar to SNX17, SNX27 is also required for LTP. Alterations in this pathway prevent chemical induction of LTP (cLTP) by impairing the activity-dependent recruitment of surface AMPA receptors (Hussain et al., 2014; Loo et al., 2014; Temkin et al., 2017). AMPA receptors are rapidly inserted into the postsynaptic membrane in response to synaptic activity, a process critical for LTP (Buonarati et al., 2019). The requirement of SNX17- and SNX27-dependent recycling for LTP supports recent findings that show extensive changes in the neuronal surface proteome upon cLTP, which are mediated by the delivery of membrane proteins from intracellular compartments (van Oostrum et al., 2020). Whether these pathways coordinate to promote cargo recycling during LTP has not been directly tested.

The signaling lipid phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI(3)P) is a key regulator of endosomal sorting and trafficking (Di Paolo and De Camilli, 2006; Raiborg et al., 2013) that can potentially interact with both SNX17 and SNX27 (Chandra et al., 2019). PI(3)P is predominantly localized on early endosomes and functions by recruiting a variety of effectors that contain PI(3)P-binding domains, such as phox homology (PX) and FYVE (Fab1, YOTB, Vac1, and EEA1) domains (Marat and Haucke, 2016); both SNX17 and SNX27 can interact with PI(3)P through their PX domains. PI(3)P is synthesized from phosphatidylinositol by phosphorylation at the third position of the inositol ring. Approximately 60–70% of the PI(3)P pool is produced by the lipid kinase VPS34 (Devereaux et al., 2013; Ikonomov et al., 2015). In addition, class II phosphatidylinositol 3 kinases and INPP4 phosphatases also contribute to PI(3)P levels (Heng and Maffucci, 2022; Gozzelino et al., 2020; Burke et al., 2022).

In neurons, PI(3)P is widely distributed in both dendrites and axons, with an enrichment at synapses, where it colocalizes with the postsynaptic scaffold PSD95 (Wang et al., 2011). PI(3)P plays key roles in neurotransmission by regulating synaptic vesicle cycling (Liu et al., 2022) and GABA receptor clustering at inhibitory synapses (Papadopoulos et al., 2017). Chronic defects in PI(3)P synthesis are linked to reductions in dendritic spine density, reactive gliosis, and progressive neurodegeneration (Wang et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2010). However, whether dynamic changes in PI(3)P synthesis impact synaptic function and plasticity remains unclear.

Here, we demonstrate a key role for PI(3)P in coordinately driving the recycling of cell surface proteins during LTP. We show that PI(3)P levels increase upon cLTP and are necessary for the structural changes in dendritic spines. We find that the role of PI(3)P in synaptic plasticity is mediated, at least in part, by regulation of the SNX17 and SNX27 pathways. Specifically, cLTP-dependent PI(3)P synthesis promotes the recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27 to endosomes and to dendritic spines. Moreover, we show that SNX17 and SNX27 define two distinct pathways that act in parallel to recycle different sets of cell surface receptors necessary for LTP. Preventing dynamic PI(3)P synthesis blocks the activity-dependent recycling of SNX17 and SNX27 cargoes and prevents LTP in hippocampal slices as well as in cultured hippocampal neurons. Together, these findings provide mechanistic insights into the regulation of endocytic recycling at synapses and define a key role for dynamic PI(3)P synthesis in enduring forms of synaptic plasticity.

Results

cLTP results in an increase in PI(3)P-containing puncta in dendrites

LTP is characterized by extensive synapse remodeling and changes in cell surface proteins, which occur through the controlled delivery of membrane proteins from intracellular compartments (van Oostrum et al., 2020). Previous studies have identified an important role for the SNX27–Retromer pathway in recycling AMPARs during LTP (Loo et al., 2014; Hussain et al., 2014), and we recently identified the SNX17–Retriever endomembrane recycling pathway as a critical regulator of LTP (Rivero-Ríos et al., 2023). The mechanism by which these parallel recycling pathways are coordinated during plasticity, however, is unknown.

One possibility is that a common upstream effector recruits both pathways. Notably, SNX17 and SNX27 both interact with the signaling lipid PI(3)P via their PX domains (Knauth et al., 2005; Lunn et al., 2007; Gillooly et al., 2000). To explore this idea, we examined dynamic changes in PI(3)P with a specific PI(3)P reporter, dsRed-EEA1-FYVE (Singla et al., 2019), which consists of the fusion between dsRed and the FYVE domain from EEA1. Using this probe in primary cultured DIV17 hippocampal neurons, we found that PI(3)P exhibited a punctate distribution pattern, with puncta distributed throughout dendrites (Fig. 1 A). A similar PI(3)P distribution in neurons was observed using the recombinant 2xFYVE domain of Hrs (Liu et al., 2022). In addition, we found that PI(3)P formation in dendrites is dependent on the lipid kinase VPS34. A 30-min treatment with either VPS34-IN1 or SAR405, chemically distinct VPS34 inhibitors, resulted in ∼72% and 85% decreases, respectively, in the numbers of dendritic PI(3)P-positive puncta (Fig. 1, A and B). To avoid a potential competition with endogenous PI(3)P, we also used a recently developed recombinant biosensor for PI(3)P, SNAP-FYVE-Hrs x 2 on fixed cells (Maib et al., 2024), which confirmed the punctate distribution of PI(3)P along dendrites and its disappearance upon VPS34-IN1 treatment (Fig. S1, A and B).

PI(3)P is present at dendrites and its synthesis increases upon cLTP. (A) Rat hippocampal neurons were transfected at DIV16 with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and eGFP as a filler. 24 h later, neurons were treated with either DMSO, 1 μM VPS34-IN1, or 1 μM SAR405 for 30 min before fixation. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified. DMSO: 0.247 ± 0.016, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1: 0.070 ± 0.011, N = 30 neurons; SAR405: 0.037 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) Example confocal images taken from DIV17 neurons expressing dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and eGFP (filler) under conditions of cLTP or HBS control (mock). Images of live neurons in an environmental chamber were captured before cLTP (baseline); during cLTP; and at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. Representative images of baseline, t = 10, and t = 30 are shown. Intensity presented in the “fire” LUT color scheme. Scale bar, 5 µm. (D) The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in 30 µm of dendritic spines at the different time points following cLTP (or mock) was quantified and normalized to the baseline for each dendrite. Mock: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 1.00 ± 0.071, cLTP: 1.04 ± 0.077, 0: 1.06 ± 0.076, 5: 1.05 ± 0.072, 10: 1.10 ± 0.069, 15: 1.08 ± 0.080, 20: 1.09 ± 0.083, 25: 1.14 ± 0.079, 30: 1.15 ± 0.079); cLTP: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 1.00 ± 0.051, cLTP: 1.20 ± 0.070, 0: 1.38 ± 0.072, 5: 1.46 ± 0.076, 10: 1.51 ± 0.075, 15: 1.63 ± 0.089, 20: 1.69 ± 0.082, 25: 1.72 ± 0.072, 30: 1.75 ± 0.076). Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, and ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (E) The size of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in 30 µm of dendritic spines at the indicated time points following cLTP (or mock) was quantified. Mock: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 0.184 ± 0.013, 10: 0.187 ± 0.011, 30: 0.186 ± 0.014); cLTP: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 0.184 ± 0.023, 10: 0.188 ± 0.023, 30: 0.181 ± 0.021). Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. (F) Hippocampal neurons were co-transfected at DIV16 with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and either an empty pRK5 vector or pRK5-HA-CaMKII-T286D. 24 h later, neurons were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with an anti-HA antibody. The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified. Ctrl: 0.201 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; CaMKII-T286D: 0.311 ± 0.017, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

PI(3)P is present at dendrites and its synthesis increases upon cLTP. (A) Rat hippocampal neurons were transfected at DIV16 with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and eGFP as a filler. 24 h later, neurons were treated with either DMSO, 1 μM VPS34-IN1, or 1 μM SAR405 for 30 min before fixation. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified. DMSO: 0.247 ± 0.016, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1: 0.070 ± 0.011, N = 30 neurons; SAR405: 0.037 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) Example confocal images taken from DIV17 neurons expressing dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and eGFP (filler) under conditions of cLTP or HBS control (mock). Images of live neurons in an environmental chamber were captured before cLTP (baseline); during cLTP; and at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. Representative images of baseline, t = 10, and t = 30 are shown. Intensity presented in the “fire” LUT color scheme. Scale bar, 5 µm. (D) The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in 30 µm of dendritic spines at the different time points following cLTP (or mock) was quantified and normalized to the baseline for each dendrite. Mock: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 1.00 ± 0.071, cLTP: 1.04 ± 0.077, 0: 1.06 ± 0.076, 5: 1.05 ± 0.072, 10: 1.10 ± 0.069, 15: 1.08 ± 0.080, 20: 1.09 ± 0.083, 25: 1.14 ± 0.079, 30: 1.15 ± 0.079); cLTP: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 1.00 ± 0.051, cLTP: 1.20 ± 0.070, 0: 1.38 ± 0.072, 5: 1.46 ± 0.076, 10: 1.51 ± 0.075, 15: 1.63 ± 0.089, 20: 1.69 ± 0.082, 25: 1.72 ± 0.072, 30: 1.75 ± 0.076). Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, and ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (E) The size of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in 30 µm of dendritic spines at the indicated time points following cLTP (or mock) was quantified. Mock: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 0.184 ± 0.013, 10: 0.187 ± 0.011, 30: 0.186 ± 0.014); cLTP: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 0.184 ± 0.023, 10: 0.188 ± 0.023, 30: 0.181 ± 0.021). Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. (F) Hippocampal neurons were co-transfected at DIV16 with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and either an empty pRK5 vector or pRK5-HA-CaMKII-T286D. 24 h later, neurons were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with an anti-HA antibody. The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified. Ctrl: 0.201 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; CaMKII-T286D: 0.311 ± 0.017, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

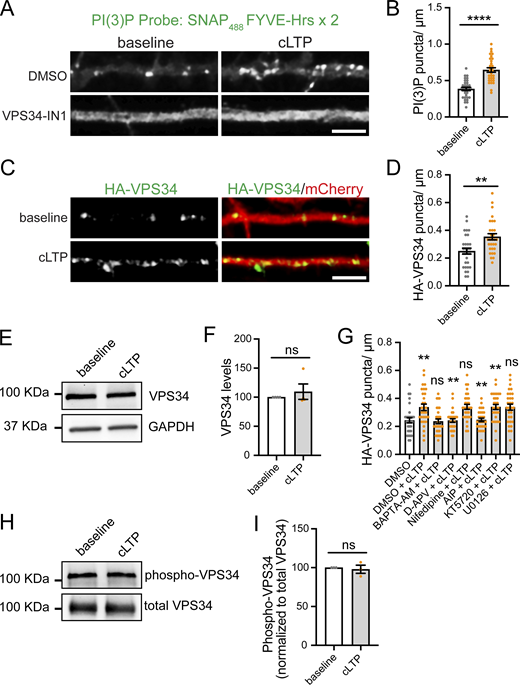

cLTP promotes the formation of PI(3)P- and VPS34-positive puncta, which is dependent on the NMDAR–calcium–CaMKII pathway. (A) Rat hippocampal neurons were transfected at DIV16 with mCherry as a filler. 24 h later, neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min. Neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 min after the cLTP stimulus. DMSO or VPS34-INH were maintained during the course of the experiment. After fixation, cells were immunostained with the PI(3)P recombinant biosensor conjugated to Alexa488 (SNAP488). Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) The number of PI(3)P-positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified for DMSO-treated cells. Baseline: 0.385 ± 0.023, N = 31 neurons; cLTP: 0.645 ± 0.031, N = 31 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were co-transfected at DIV16 with HA-VPS34 and mCherry as a filler. 24 h later, neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 min after the cLTP stimulus, followed by immunostaining with an anti-HA antibody. Scale bar, 5 µm. (D) The number of HA-VPS34–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified. Baseline: 0.250 ± 0.021, N = 30 neurons; cLTP: 0.353 ± 0.022, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t test, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. (E) DIV17 rat cortical neurons were either left untreated (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min. Extracts were collected 10 min after cLTP and analyzed by western blot for the levels of VPS34, and GAPDH was used as a loading control. (F) VPS34 levels were quantified and normalized to the baseline protein levels. Baseline: 100; cLTP: 109.50 ± 13.24. Four independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t test. Error bars are SEM. (G) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were co-transfected at DIV16 with HA-VPS34 and mCherry as a filler. 24 h later, neuron cultures were treated with DMSO, 10 μM BAPTA-AM, 100 μM D-APV, 10 μM nifedipine, 10 uM AIP, 2 μM KT5720, or 10 μM U0126 for 30 min, followed by a 5-min cLTP stimulus in the presence of compounds where indicated. Neurons were further incubated in the presence of the indicated compounds for 10 min before fixation, followed by permeabilization and incubation with an anti-HA antibody. The number of HA-VPS34–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified. DMSO: 0.243 ± 0.019, N = 30 neurons; DMSO + cLTP: 0.337 ± 0.023, N = 30 neurons; BAPTA-AM + cLTP: 0.237 ± 0.017, N = 30 neurons; D-APV + cLTP: 0.242 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; nifedipine + cLTP: 0.340 ± 0.018, N = 30 neurons; AIP + cLTP: 0.247 ± 0.012, N = 30 neurons; KT5720 + cLTP: 0.339 ± 0.018, N = 30 neurons; U0126 + cLTP: 0.338 ± 0.021, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. (H) DIV16 rat hippocampal neurons were either left untreated (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min. Extracts were collected 10 min after cLTP and used for immunoprecipitation with an anti-VPS34 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with an antibody against pan-phospho-Ser/Thr. (I) The ratios of pan-phospho-Ser/Thr to VPS34 were quantified and normalized to the baseline group. Baseline: 100; cLTP: 97.95 ± 5.22. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t test. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

cLTP promotes the formation of PI(3)P- and VPS34-positive puncta, which is dependent on the NMDAR–calcium–CaMKII pathway. (A) Rat hippocampal neurons were transfected at DIV16 with mCherry as a filler. 24 h later, neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min. Neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 min after the cLTP stimulus. DMSO or VPS34-INH were maintained during the course of the experiment. After fixation, cells were immunostained with the PI(3)P recombinant biosensor conjugated to Alexa488 (SNAP488). Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) The number of PI(3)P-positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified for DMSO-treated cells. Baseline: 0.385 ± 0.023, N = 31 neurons; cLTP: 0.645 ± 0.031, N = 31 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were co-transfected at DIV16 with HA-VPS34 and mCherry as a filler. 24 h later, neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 min after the cLTP stimulus, followed by immunostaining with an anti-HA antibody. Scale bar, 5 µm. (D) The number of HA-VPS34–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified. Baseline: 0.250 ± 0.021, N = 30 neurons; cLTP: 0.353 ± 0.022, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t test, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. (E) DIV17 rat cortical neurons were either left untreated (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min. Extracts were collected 10 min after cLTP and analyzed by western blot for the levels of VPS34, and GAPDH was used as a loading control. (F) VPS34 levels were quantified and normalized to the baseline protein levels. Baseline: 100; cLTP: 109.50 ± 13.24. Four independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t test. Error bars are SEM. (G) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were co-transfected at DIV16 with HA-VPS34 and mCherry as a filler. 24 h later, neuron cultures were treated with DMSO, 10 μM BAPTA-AM, 100 μM D-APV, 10 μM nifedipine, 10 uM AIP, 2 μM KT5720, or 10 μM U0126 for 30 min, followed by a 5-min cLTP stimulus in the presence of compounds where indicated. Neurons were further incubated in the presence of the indicated compounds for 10 min before fixation, followed by permeabilization and incubation with an anti-HA antibody. The number of HA-VPS34–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified. DMSO: 0.243 ± 0.019, N = 30 neurons; DMSO + cLTP: 0.337 ± 0.023, N = 30 neurons; BAPTA-AM + cLTP: 0.237 ± 0.017, N = 30 neurons; D-APV + cLTP: 0.242 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; nifedipine + cLTP: 0.340 ± 0.018, N = 30 neurons; AIP + cLTP: 0.247 ± 0.012, N = 30 neurons; KT5720 + cLTP: 0.339 ± 0.018, N = 30 neurons; U0126 + cLTP: 0.338 ± 0.021, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. (H) DIV16 rat hippocampal neurons were either left untreated (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min. Extracts were collected 10 min after cLTP and used for immunoprecipitation with an anti-VPS34 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with an antibody against pan-phospho-Ser/Thr. (I) The ratios of pan-phospho-Ser/Thr to VPS34 were quantified and normalized to the baseline group. Baseline: 100; cLTP: 97.95 ± 5.22. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s unpaired t test. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

To determine whether synaptic activity regulates PI(3)P synthesis, we performed live-cell imaging with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and monitored PI(3)P dynamics over time in the same dendrite. We used a well-established cLTP protocol (400 µM glycine and 0 Mg2+; 5 min), which promotes synaptic NMDAR activation to induce a long-lasting increase in postsynaptic strength (Lu et al., 2001; Park et al., 2004; Rivero-Ríos et al., 2023) and an enduring enlargement of dendritic spines (Henry et al., 2017). In mock-treated cells, which did not receive the cLTP stimulus, PI(3)P puncta size and number were stable over the course of the experiment. By contrast, the numbers of dsRed-FYVE-–positive puncta began increasing immediately after the cLTP stimulus and remained significantly elevated throughout the remaining time points analyzed, up to 30 min after cLTP. (Fig. 1, C and D). The size of the PI(3)P-positive compartments remained constant across all time points analyzed (Fig. 1, C and E). Note that we did not detect trafficking of the PI(3)P-positive compartments to dendritic spines, which suggests that PI(3)P-enriched endosomes may primarily localize to the dendritic shaft. Alternatively, the levels of PI(3)P moving into spines may be substantially lower than in the shaft, limiting detection by the probe. Using the recombinant PI(3)P bioprobe, we observed a similar increase in endogenous PI(3)P-positive puncta upon cLTP (Fig. S1, A and B).

Since PI(3)P formation in dendrites depends on VPS34, we hypothesized that the cLTP-induced increase in PI(3)P-positive endosomes may result from enhanced VPS34 activity. Because no suitable antibody is available for immunolocalizing endogenous rat VPS34, we transfected neurons with HA-tagged VPS34 (Park et al., 2016). We found that the increase in PI(3)P-positive puncta correlates with an increase in the number of VPS34-positive endosomes 10 min after cLTP treatment (Fig. S1, C and D). Notably, this increase in VPS34-positive endosomes was not due to elevated VPS34 expression levels (Fig. S1, E and F), suggesting that it reflects changes in VPS34 localization. The protein is likely being recruited from the cytosol to endosomal membranes.

cLTP depends on NMDA receptor activation, which increases postsynaptic calcium levels and triggers downstream signaling cascades, including calcium/CaM-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), protein kinase A, and Ras extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Musleh et al., 1997; Lisman et al., 2012). To determine whether cLTP-induced VPS34 recruitment to endosomes is mediated by NMDA receptor activation and calcium-dependent signaling, we pharmacologically disrupted key LTP pathways. These manipulations included intracellular calcium chelation with membrane-permeable BAPTA-AM, NMDA receptor blockade with D-APV, inhibition of L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels with nifedipine, inhibition of CaMKII with autocamtide-2–related inhibitory peptide (AIP), inhibition of protein kinase A with KT5720, and blockade of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling with U0126. Among these treatments, BAPTA-AM, D-APV, and AIP fully blocked the cLTP-dependent increase in VPS34 endosomes, while the other inhibitors had no effect (Fig. S1 G). These findings suggest that activity-dependent NMDAR activation, intracellular calcium elevation, and CaMKII signaling are required for recruiting VPS34 to endosomes to generate PI(3)P upon cLTP.

To test whether CaMKII activation is sufficient to increase PI(3)P-positive puncta, we utilized a hyperactive CaMKII mutant, T286D, which has been shown to induce LTP when introduced with a viral expression system (Pettit et al., 1994; Hayashi et al., 2000) or by direct injection into postsynaptic cells (Lledo et al., 1995). We co-transfected rat hippocampal neurons with CaMKII-T286D (or an empty vector) together with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE. Expression of CaMKII-T286D for 24 h led to an increase in PI(3)P-positive endosomes in the absence of an external cLTP stimulus (Fig. 1 F). Taken together, these observations suggest that increased dendritic PI(3)P synthesis accompanies strong synaptic NMDAR activity and CaMKII activation.

CaMKII activation promotes the phosphorylation of a wide array of synaptic proteins, which modulates their activity and/or trafficking to drive synaptic plasticity (Coultrap and Bayer, 2012; Lisman et al., 2012). Therefore, we hypothesized that the cLTP-induced recruitment of VPS34 to endosomes might result from direct CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation. To test this, we performed immunoprecipitation of endogenous VPS34 followed by immunoblotting with a pan phospho-serine/threonine antibody. We observed no significant change in VPS34 phosphorylation levels 10 min after cLTP (Fig. S1, H and I). These results suggest that VPS34 endosomal recruitment is not regulated by direct CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation. Instead, CaMKII may act indirectly, potentially by phosphorylating VPS34-interacting partners or by modulating upstream regulators of endosomal trafficking.

Increased PI(3)P levels upon cLTP regulate functional and structural plasticity

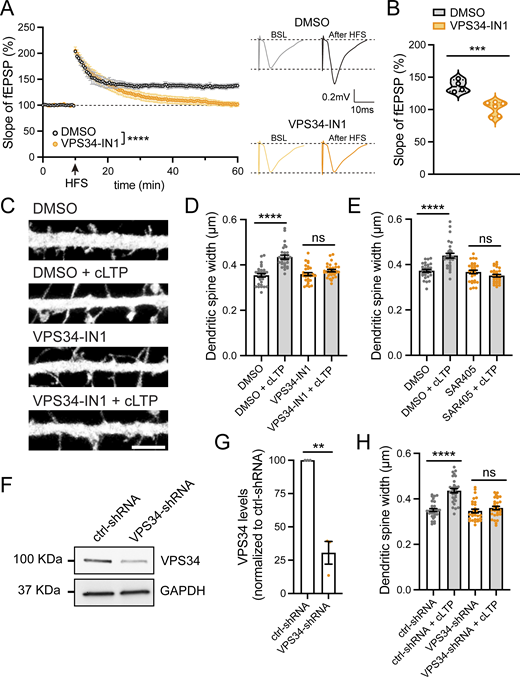

To analyze the functional consequences of reduced PI(3)P synthesis at synapses, we tested the effect of pharmacological inhibition of VPS34 on LTP induction using electrophysiological recordings in acute hippocampal slices from wild-type mice. Slices were incubated with either DMSO or 5 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min prior to recording. Following a stable 10-min baseline, LTP was induced by two high-frequency stimulations (100 Hz, 1 s) separated by 30 s (Temkin et al., 2017). VPS34-IN1 treatment impaired LTP induction compared with DMSO-treated controls (Fig. 2, A and B), indicating that PI(3)P synthesis is essential for LTP.

A decrease in PI(3)P levels blocks functional and structural plasticity during LTP. (A) Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded in the CA1 stratum radiatum using ACSF-filled glass pipettes (3–5 MΩ). Schaffer collateral fibers were stimulated every 30 s with 0.1-ms pulses (50–250 μA), and slices were pretreated with DMSO (n = 4 slices, 4 mice) or 5 μM VPS34-IN1 (n = 6 slices, 4 mice) for 30 min. After a 10-min stable baseline, LTP was induced with two high-frequency stimulations (HFS; 100 Hz, 1 s) separated by 30 s. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.0001. Error bars are SEM. (B) Summary data (55–60 min after HFS) corresponding to (A). DMSO: 136.441 ± 4.657; VPS34-IN1: 102.142 ± 4.388. Data were analyzed by Student’s unpaired t test, ***P < 0.001. (C) Representative confocal images of dendritic spines in DIV16 hippocampal neurons transfected with eGFP (filler) at DIV12. Neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min, followed by a 5-min cLTP stimulus in the presence of the compounds where indicated. Neurons were further incubated in the presence of DMSO or VPS34-IN1 for 50 min before fixation. Scale bar, 5 µm. (D) The maximum width for each spine was quantified, and the average size of the dendritic spines in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was calculated. DMSO: 0.354 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; DMSO with cLTP: 0.435 ± 0.009, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1: 0.359 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 with cLTP: 0.375 ± 0.006, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (E) Neurons were transfected at DIV12 with eGFP (filler). At DIV16, neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM SAR405 for 30 min, followed by a 5-min cLTP stimulus in the presence of compounds where indicated. Neurons were further incubated in the presence of DMSO or SAR405 for 50 min before fixation. The maximum width for each spine was quantified, and the average size of the dendritic spines in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was calculated. DMSO: 0.373 ± 0.006, N = 30 neurons; DMSO with cLTP: 0.439 ± 0.011, N = 30 neurons; SAR405: 0.367 ± 0.008, N = 30 neurons; SAR405 with cLTP: 0.351 ± 0.006, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (F) Validation of an shRNA clone to knockdown rat VPS34. Rat cortical neurons were infected with lentiviruses carrying either VPS34-shRNA (TRCN0000025373; Millipore Sigma) or control-shRNA (pLKO.1 scrambled nontarget shRNA SHC002, Millipore Sigma) at an MOI of 2. At 6 days after infection, cell extracts were collected and analyzed by western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (G) The levels of VPS34 protein were quantified in neurons infected with VPS34-shRNA and normalized to VPS34 levels in control-shRNA–infected neurons. ctrl-shRNA: 100%; VPS34-shRNA: 30.5 ± 8.50%. N = 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. (H) DIV12 neurons were co-transfected with eGFP (filler) and either ctrl-shRNA or VPS34-shRNA. At DIV16, neurons were either treated with cLTP or left untreated and fixed 50 min after cLTP. The maximum width for each spine was quantified and the average size of the dendritic spines in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was calculated. ctrl-shRNA: 0.351 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; ctrl-shRNA with cLTP: 0.436 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-shRNA: 0.347 ± 0.008, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-shRNA with cLTP: 0.360 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

A decrease in PI(3)P levels blocks functional and structural plasticity during LTP. (A) Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded in the CA1 stratum radiatum using ACSF-filled glass pipettes (3–5 MΩ). Schaffer collateral fibers were stimulated every 30 s with 0.1-ms pulses (50–250 μA), and slices were pretreated with DMSO (n = 4 slices, 4 mice) or 5 μM VPS34-IN1 (n = 6 slices, 4 mice) for 30 min. After a 10-min stable baseline, LTP was induced with two high-frequency stimulations (HFS; 100 Hz, 1 s) separated by 30 s. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.0001. Error bars are SEM. (B) Summary data (55–60 min after HFS) corresponding to (A). DMSO: 136.441 ± 4.657; VPS34-IN1: 102.142 ± 4.388. Data were analyzed by Student’s unpaired t test, ***P < 0.001. (C) Representative confocal images of dendritic spines in DIV16 hippocampal neurons transfected with eGFP (filler) at DIV12. Neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min, followed by a 5-min cLTP stimulus in the presence of the compounds where indicated. Neurons were further incubated in the presence of DMSO or VPS34-IN1 for 50 min before fixation. Scale bar, 5 µm. (D) The maximum width for each spine was quantified, and the average size of the dendritic spines in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was calculated. DMSO: 0.354 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; DMSO with cLTP: 0.435 ± 0.009, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1: 0.359 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 with cLTP: 0.375 ± 0.006, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (E) Neurons were transfected at DIV12 with eGFP (filler). At DIV16, neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM SAR405 for 30 min, followed by a 5-min cLTP stimulus in the presence of compounds where indicated. Neurons were further incubated in the presence of DMSO or SAR405 for 50 min before fixation. The maximum width for each spine was quantified, and the average size of the dendritic spines in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was calculated. DMSO: 0.373 ± 0.006, N = 30 neurons; DMSO with cLTP: 0.439 ± 0.011, N = 30 neurons; SAR405: 0.367 ± 0.008, N = 30 neurons; SAR405 with cLTP: 0.351 ± 0.006, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (F) Validation of an shRNA clone to knockdown rat VPS34. Rat cortical neurons were infected with lentiviruses carrying either VPS34-shRNA (TRCN0000025373; Millipore Sigma) or control-shRNA (pLKO.1 scrambled nontarget shRNA SHC002, Millipore Sigma) at an MOI of 2. At 6 days after infection, cell extracts were collected and analyzed by western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (G) The levels of VPS34 protein were quantified in neurons infected with VPS34-shRNA and normalized to VPS34 levels in control-shRNA–infected neurons. ctrl-shRNA: 100%; VPS34-shRNA: 30.5 ± 8.50%. N = 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. (H) DIV12 neurons were co-transfected with eGFP (filler) and either ctrl-shRNA or VPS34-shRNA. At DIV16, neurons were either treated with cLTP or left untreated and fixed 50 min after cLTP. The maximum width for each spine was quantified and the average size of the dendritic spines in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was calculated. ctrl-shRNA: 0.351 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; ctrl-shRNA with cLTP: 0.436 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-shRNA: 0.347 ± 0.008, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-shRNA with cLTP: 0.360 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

During LTP, dendritic spines undergo activity-dependent structural changes, which involve actin cytoskeleton reorganization, membrane trafficking, and membrane remodeling. LTP is associated with a structural increase in the dendritic spine head area (Nakahata and Yasuda, 2018; Bosch et al., 2014; Meyer et al., 2014). Thus, we tested whether dynamic PI(3)P synthesis is necessary for changes in dendritic spine width that accompany LTP. We employed three different approaches to decrease PI(3)P levels. Cultured hippocampal neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 µM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min, followed by cLTP/mock stimulation, and then the width of dendritic spines within the first 30 µm of secondary dendrites were quantified. In DMSO-treated cells, cLTP resulted in a significant increase in dendritic spine width, whereas treatment with the VPS34 inhibitor completely blocked these structural changes in spines (Fig. 2, C and D). Similarly, treatment with 1 µM SAR405 also prevented the cLTP-dependent increase in dendritic spine width (Fig. 2 E).

As an alternative means to block PI(3)P synthesis, we employed shRNA to knockdown VPS34 in rat neurons (Fig. 2, F and G). As expected, cells expressing a scrambled (control) shRNA exhibited a significant increase in spine head area 50 min after cLTP induction. However, this structural plasticity was lost in VPS34 knockdown neurons (Fig. 2 H). Together, these data indicate that PI(3)P synthesis by VPS34 is critical for the structural changes that underlie the enduring enhancement of synaptic function following cLTP.

We next sought to determine the temporal window during which PI(3)P synthesis is required for cLTP-induced structural plasticity. We tested 2 conditions: pretreatment with VPS34-IN1 for 30 min prior to cLTP induction and initiation of VPS34-IN1 treatment 5 min after removal of the cLTP stimulus. Inhibition of VPS34 prior to cLTP induction effectively blocked the cLTP-dependent structural changes in dendritic spines. In contrast, when VPS34-IN1 was applied after cLTP induction, structural plasticity of spines was preserved (Fig. S2, A and B). These results suggest that early PI(3)P synthesis is critical for the cLTP-dependent structural remodeling of spines.

Sustained inhibition of PI(3)P synthesis is necessary to block the cLTP-dependent structural plasticity of spines. (A) Diagram of experiment. DIV16 hippocampal neurons were transfected with eGFP as a filler to visualize dendritic morphology. In the long treatment condition, 24 h after transfection, cells were either treated with DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min, followed by a 5-min cLTP stimulus in the presence of the compounds where indicated. Neurons were then further incubated in the presence of DMSO or VPS34-IN1 for an additional 50 min before fixation. In the short treatment condition, treatment with DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 was initiated 5 min after the cLTP stimulus. (B) The maximum width for each spine was quantified, and the average size of the dendritic spines in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was calculated. DMSO (short): 0.360 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; DMSO (short) with cLTP: 0.417 ± 0.012, N = 30 neurons; DMSO (long): 0.353 ± 0.006, N = 30 neurons; DMSO (long) with cLTP: 0.453 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 (short): 0.345 ± 0.008, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 (short) with cLTP: 0.425 ± 0.011, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 (long): 0.355 ± 0.009, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 (long) with cLTP: 0.351 ± 0.008, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Sustained inhibition of PI(3)P synthesis is necessary to block the cLTP-dependent structural plasticity of spines. (A) Diagram of experiment. DIV16 hippocampal neurons were transfected with eGFP as a filler to visualize dendritic morphology. In the long treatment condition, 24 h after transfection, cells were either treated with DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min, followed by a 5-min cLTP stimulus in the presence of the compounds where indicated. Neurons were then further incubated in the presence of DMSO or VPS34-IN1 for an additional 50 min before fixation. In the short treatment condition, treatment with DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 was initiated 5 min after the cLTP stimulus. (B) The maximum width for each spine was quantified, and the average size of the dendritic spines in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was calculated. DMSO (short): 0.360 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; DMSO (short) with cLTP: 0.417 ± 0.012, N = 30 neurons; DMSO (long): 0.353 ± 0.006, N = 30 neurons; DMSO (long) with cLTP: 0.453 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 (short): 0.345 ± 0.008, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 (short) with cLTP: 0.425 ± 0.011, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 (long): 0.355 ± 0.009, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 (long) with cLTP: 0.351 ± 0.008, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Increased PI(3)P synthesis drives the recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27 to endosomal compartments upon cLTP

SNX17 and SNX27 define two major endomembrane recycling pathways in non-neuronal cells (Steinberg et al., 2013; McNally et al., 2017). Both SNX17 and SNX27 belong to the PX-FERM subfamily of sorting nexins and are recruited to early endosomal membranes through their PX domains, which bind PI(3)P (Fig. S3 A) (Lunn et al., 2007; Gillooly et al., 2000; Ponting, 1996; Knauth et al., 2005). In addition to their PX domains, both proteins contain FERM domains. While the SNX17 FERM domain binds to cargoes containing NPxY/NxxY motifs (Ghai et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2018), the SNX27 FERM domain interacts with SNX1/2 on endosomal membranes (Yong et al., 2021). Unique to the PX-FERM subfamily, SNX27 also contains a PDZ domain, which is involved in cargo recognition (Fig. S3 A) (Steinberg et al., 2013). Notably, both SNX27 and SNX17 have been implicated in LTP. SNX27 is critical for LTP via its role in recycling AMPA receptors (Wang et al., 2013; Hussain et al., 2014; McMillan et al., 2021; Huo et al., 2020), while SNX17 is critical for LTP via its role in the recycling of β1-integrin (Rivero-Ríos et al., 2023).

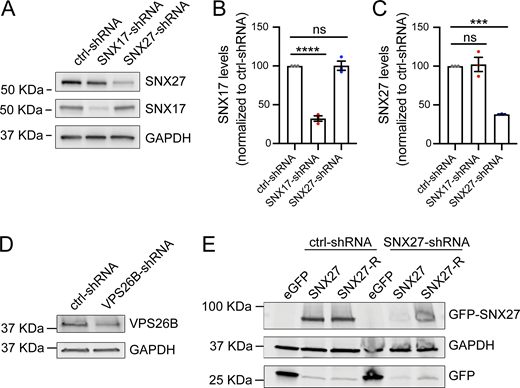

PI(3)P and its lipid kinase VPS34 colocalize with SNX17 and SNX27 in dendrites. (A) Domain architecture of the SNX-FERM proteins used in this study. (B) Rat hippocampal neurons were transfected at DIV16 with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and either GFP-SNX17 or GFP-SNX27 and fixed 24 h later. Scale bar, 5 µm. (C) The colocalization between dsRed-EEA1-FYVE– and either GFP-SNX17– or GFP-SNX27–positive puncta was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). GFP-SNX17: 79.55 ± 1.617%, N = 30 neurons; GFP-SNX27: 83.00 ± 1.573%, N = 30 neurons. (D) Rat hippocampal neurons were co-transfected at DIV16 with mScarlet-SNX27, mNeonGreen-SNX17, and HA-VPS34. 24 h later, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained with an anti-HA antibody. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (E) The percentage of mNeonGreen-SNX17 overlapping with mScarlet-SNX27 was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). 81.22 ± 3.386%, N = 15 neurons. Three independent experiments. Error bar is SEM. (F) The percentage of mScarlet-SNX27 overlapping with mNeonGreen-SNX17 was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). 82.49 ± 2.480%, N = 15 neurons. Three independent experiments. Error bar is SEM. (G) The percentage of endosomes containing both mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mScarlet-SNX27 that colocalize with HA-VPS34 was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). 72.83 ± 3.323%, N = 15 neurons. Three independent experiments. Error bar is SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

PI(3)P and its lipid kinase VPS34 colocalize with SNX17 and SNX27 in dendrites. (A) Domain architecture of the SNX-FERM proteins used in this study. (B) Rat hippocampal neurons were transfected at DIV16 with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and either GFP-SNX17 or GFP-SNX27 and fixed 24 h later. Scale bar, 5 µm. (C) The colocalization between dsRed-EEA1-FYVE– and either GFP-SNX17– or GFP-SNX27–positive puncta was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). GFP-SNX17: 79.55 ± 1.617%, N = 30 neurons; GFP-SNX27: 83.00 ± 1.573%, N = 30 neurons. (D) Rat hippocampal neurons were co-transfected at DIV16 with mScarlet-SNX27, mNeonGreen-SNX17, and HA-VPS34. 24 h later, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained with an anti-HA antibody. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (E) The percentage of mNeonGreen-SNX17 overlapping with mScarlet-SNX27 was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). 81.22 ± 3.386%, N = 15 neurons. Three independent experiments. Error bar is SEM. (F) The percentage of mScarlet-SNX27 overlapping with mNeonGreen-SNX17 was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). 82.49 ± 2.480%, N = 15 neurons. Three independent experiments. Error bar is SEM. (G) The percentage of endosomes containing both mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mScarlet-SNX27 that colocalize with HA-VPS34 was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). 72.83 ± 3.323%, N = 15 neurons. Three independent experiments. Error bar is SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Given that PI(3)P is a shared binding partner of both pathways, we hypothesized that PI(3)P may regulate both SNX17- and SNX27-dependent recycling during cLTP.

As a first approach, we investigated whether SNX17 and SNX27 localize to PI(3)P-positive endosomes in dendrites. As there is no suitable antibody available for immunolocalization of endogenous rat SNX27, we generated GFP-tagged constructs for SNX17 and SNX27. Note that the addition of an N-terminal tag to these proteins does not interfere with their ability to bind cargo or endosomal membranes (McNally et al., 2017; McMillan et al., 2021). Co-transfection of neurons with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and either GFP-SNX17 or GFP-SNX27 for 24 h revealed that ∼80% of the SNX17- or SNX27-positive puncta overlap with PI(3)P (Fig. S3, B and C).

As an additional means to test the link between PI(3)P synthesis and the recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27 to endosomes, we analyzed the colocalization of these sorting nexins with VPS34. Neurons were co-transfected with HA-VPS34, mNeonGreen-SNX17, and mScarlet-SNX27 and imaged to assess triple colocalization. Given that SNX17 and SNX27 exhibit a high degree of overlap, with ∼80% colocalization (Fig. S3, D–F), we generated a binary mask of compartments that are positive for both SNX17 and SNX27 to define endosomes actively engaged in recycling and quantified their colocalization with HA-VPS34. Approximately 70% of these SNX17/SNX27-positive endosomes also contained VPS34 (Fig. S3, D and G), supporting a strong spatial association between PI(3)P synthesis and the recruitment of endocytic recycling machinery.

To investigate whether the increase in PI(3)P-positive compartments following cLTP results in enhanced endosomal recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27, we transiently transfected neurons with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and GFP-SNX17 and treated them with or without cLTP. We then analyzed the numbers of PI(3)P and GFP-SNX17 puncta at 10 and 30 min after cLTP. We observed a significant increase in PI(3)P puncta over time (Fig. 3, A and B), which corresponded with a similar increase in GFP-SNX17 puncta (Fig. 3, A and C). Notably, SNX17 showed strong colocalization with PI(3)P under basal conditions and at 10 and 30 min after cLTP (Fig. 3, A and D). In parallel, we co-transfected neurons with dsRed-EEA1-FYVE and GFP-SNX27 and quantified puncta numbers 10 and 30 min after cLTP stimulation. The numbers of GFP-SNX27–positive puncta also increased upon cLTP and showed strong overlap with PI(3)P at each time point tested (Fig. 3, E–H).

Increased PI(3)P synthesis upon cLTP regulates the formation of SNX17- and SNX27-positive puncta. (A) Representative confocal images of DIV17 hippocampal neurons that were transfected at DIV16 with GFP-SNX17 and dsRed-EEA1-FYVE. 24 h later, neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 or 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. Baseline: 0.241 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 0.327 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 0.361 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) The number of GFP-SNX17 puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. Baseline: 0.227 ± 0.009, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 0.317 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 0.349 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (D) The colocalization between dsRed-EEA1-FYVE– and GFP-SNX17–positive puncta was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). Baseline: 84.25 ± 2.019%, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 84.94 ± 2.041%, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 82.87 ± 1.751%, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. (E) Representative confocal images of DIV17 hippocampal neurons that were transfected at DIV16 with GFP-SNX27 and dsRed-EEA1-FYVE. 24 h later, neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 or 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. Scale bar, 5 µm. (F) The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. Baseline: 0.268 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 0.353 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 0.389 ± 0.015, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (G) The number of GFP-SNX27 puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. Baseline: 0.258 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 0.340 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 0.378 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (H) The colocalization between dsRed-EEA1-FYVE– and GFP-SNX27–positive puncta was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). Baseline: 84.60 ± 1.668%, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 86.17 ± 1.483%, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 85.68 ± 2.027%, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Increased PI(3)P synthesis upon cLTP regulates the formation of SNX17- and SNX27-positive puncta. (A) Representative confocal images of DIV17 hippocampal neurons that were transfected at DIV16 with GFP-SNX17 and dsRed-EEA1-FYVE. 24 h later, neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 or 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. Baseline: 0.241 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 0.327 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 0.361 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) The number of GFP-SNX17 puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. Baseline: 0.227 ± 0.009, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 0.317 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 0.349 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (D) The colocalization between dsRed-EEA1-FYVE– and GFP-SNX17–positive puncta was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). Baseline: 84.25 ± 2.019%, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 84.94 ± 2.041%, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 82.87 ± 1.751%, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. (E) Representative confocal images of DIV17 hippocampal neurons that were transfected at DIV16 with GFP-SNX27 and dsRed-EEA1-FYVE. 24 h later, neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 or 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. Scale bar, 5 µm. (F) The number of dsRed-EEA1-FYVE–positive puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. Baseline: 0.268 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 0.353 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 0.389 ± 0.015, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (G) The number of GFP-SNX27 puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. Baseline: 0.258 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 0.340 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 0.378 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (H) The colocalization between dsRed-EEA1-FYVE– and GFP-SNX27–positive puncta was analyzed using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). Baseline: 84.60 ± 1.668%, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 10 min: 86.17 ± 1.483%, N = 30 neurons; cLTP 30 min: 85.68 ± 2.027%, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Since VPS34 inhibition leads to a loss of PI(3)P puncta in dendrites (Fig. 1, A and B), we tested whether PI(3)P produced by VPS34 is required for the cLTP-dependent recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27. We transiently transfected neurons with mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mScarlet-SNX27 and analyzed puncta numbers at 10 and 30 min following cLTP in the presence or absence of VPS34-IN1. VPS34-IN1 treatment significantly reduced the numbers of SNX17- and SNX27-positive puncta and also blocked the cLTP-dependent increase in puncta numbers (Fig. S4, A–C). mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mScarlet-SNX27 showed ∼80% colocalization under baseline conditions and at each time point tested (Fig. S4, D and E), which suggests that they are coordinately recruited to PI(3)P-positive endosomes. Together, these results suggest that PI(3)P generation by VPS34 is necessary for the increase in SNX17- and SNX27-positive puncta following cLTP.

Decreased PI(3)P levels block the cLTP-dependent increase in SNX17- and SNX27-positive puncta. (A) Representative confocal images of DIV17 hippocampal neurons that were transfected at DIV16 with mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mScarlet-SNX27. 24 h later, neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min. Neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 or 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. DMSO or VPS34-IN1 were maintained during the course of the experiment. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) The number of mNeonGreen-SNX17 puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. DMSO baseline: 0.238 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; DMSO cLTP 10 min: 0.362 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; DMSO cLTP 30 min: 0.379 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 baseline: 0.090 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 cLTP 10 min: 0.114 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 cLTP 30 min: 0.119 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) The number of mScarlet-SNX27 puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. DMSO baseline: 0.243 ± 0.012, N = 30 neurons; DMSO cLTP 10 min: 0.367 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; DMSO cLTP 30 min: 0.389 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 baseline: 0.101 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 cLTP 10 min: 0.124 ± 0.011, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 cLTP 30 min: 0.124 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (D) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were transfected with mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mScarlet-SNX27. 24 h later, neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 0, 10, 30 or 60 min after the cLTP stimulus. The percentage of SNX17 that overlaps with SNX27 at the different time points was determined using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). Baseline: 80.94 ± 2.058%, N = 26 neurons; 0 min after cLTP: 80.42 ± 1.678%, N = 28 neurons; 10 min after cLTP: 83.64 ± 1.582%, N = 30 neurons; 30 min after cLTP: 85.79 ± 1.474%, N = 30 neurons; 60 min after cLTP: 79.57 ± 1.512%, N = 24 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. (E) Same as D, but the percentage of SNX27 that overlaps with SNX17 at the different time points was determined using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). Baseline: 90.52 ± 2.066%, N = 26 neurons; 0 min after cLTP: 89.63 ± 1.605%, N = 28 neurons; 10 min after cLTP: 91.05 ± 1.689%, N = 30 neurons; 30 min after cLTP: 90.43 ± 1.525%, N = 30 neurons; 60 min after cLTP: 88.47 ± 2.162%, N = 24 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Decreased PI(3)P levels block the cLTP-dependent increase in SNX17- and SNX27-positive puncta. (A) Representative confocal images of DIV17 hippocampal neurons that were transfected at DIV16 with mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mScarlet-SNX27. 24 h later, neurons were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 30 min. Neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 10 or 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. DMSO or VPS34-IN1 were maintained during the course of the experiment. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) The number of mNeonGreen-SNX17 puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. DMSO baseline: 0.238 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; DMSO cLTP 10 min: 0.362 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; DMSO cLTP 30 min: 0.379 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 baseline: 0.090 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 cLTP 10 min: 0.114 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 cLTP 30 min: 0.119 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) The number of mScarlet-SNX27 puncta in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites was quantified at the indicated time points. DMSO baseline: 0.243 ± 0.012, N = 30 neurons; DMSO cLTP 10 min: 0.367 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; DMSO cLTP 30 min: 0.389 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 baseline: 0.101 ± 0.007, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 cLTP 10 min: 0.124 ± 0.011, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1 cLTP 30 min: 0.124 ± 0.010, N = 30 neurons. Three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (D) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were transfected with mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mScarlet-SNX27. 24 h later, neurons were either fixed in the absence of cLTP (baseline) or treated with cLTP for 5 min and fixed 0, 10, 30 or 60 min after the cLTP stimulus. The percentage of SNX17 that overlaps with SNX27 at the different time points was determined using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). Baseline: 80.94 ± 2.058%, N = 26 neurons; 0 min after cLTP: 80.42 ± 1.678%, N = 28 neurons; 10 min after cLTP: 83.64 ± 1.582%, N = 30 neurons; 30 min after cLTP: 85.79 ± 1.474%, N = 30 neurons; 60 min after cLTP: 79.57 ± 1.512%, N = 24 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. (E) Same as D, but the percentage of SNX27 that overlaps with SNX17 at the different time points was determined using Mander’s colocalization coefficient (×100). Baseline: 90.52 ± 2.066%, N = 26 neurons; 0 min after cLTP: 89.63 ± 1.605%, N = 28 neurons; 10 min after cLTP: 91.05 ± 1.689%, N = 30 neurons; 30 min after cLTP: 90.43 ± 1.525%, N = 30 neurons; 60 min after cLTP: 88.47 ± 2.162%, N = 24 neurons. Three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Increased PI(3)P synthesis drives the recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27 to dendritic spines upon cLTP

We previously discovered that SNX17 is recruited to dendritic spines upon cLTP and correlates with dendritic spine enlargement (Rivero-Ríos et al., 2023). The strong colocalization between SNX17 and SNX27 after cLTP (Fig. S4, D and E) suggests that SNX27 may also be recruited to dendritic spines upon cLTP. To test this possibility, we performed live-cell imaging of mScarlet-SNX27 in neurons co-expressing soluble eGFP (Fig. S5 A). In the cLTP-treated cells, there was a marked increase in dendritic spine width 30 min after the stimulus (Fig. S5 B). Consistent with our findings for SNX17 (Rivero-Ríos et al., 2023), we observed increased recruitment of SNX27 to synapses following cLTP. The intensity of mScarlet-SNX27 at dendritic spines significantly increased 5 min after the stimulus, continued to rise at 10 min, and remained significantly elevated at all subsequent time points up to 30 min after cLTP (Fig. S5 C). This increased recruitment of SNX27 to spines was also accompanied by an increase in the number of mScarlet-SNX27–positive puncta following cLTP (Fig. S5 D). Similar to SNX17 (Rivero-Ríos et al., 2023), the expression of CaMKII-T286D was sufficient to promote the formation of mScarlet-SNX27–positive puncta and their subsequent recruitment to dendritic spines (Fig. S5, E and F).

SNX27 is recruited to dendritic spines upon cLTP, which is dependent on the CaMKII pathway. (A) Representative confocal images from DIV17 hippocampal neurons expressing mScarlet-SNX27 and eGFP (filler) under conditions of cLTP or HBS control (mock). Images of live neurons were captured before cLTP (baseline); during cLTP; and at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. Representative images of baseline, t = 10, and t = 30 are shown. Intensity presented in the fire LUT color scheme. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (B) The endpoint of the experiment (30 min) was used to measure the cLTP-dependent increase in dendritic spine width. To calculate the increase in spine size, the final spine width was normalized to the baseline width for each spine. Mock: 1.024 ± 0.025, N = 98 spines across 15 cells; cLTP: 1.498 ± 0.056, N = 108 spines across 15 cells. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) The mean intensity of mScarlet-SNX27 was measured in the spines that remained in the same plane at each time point following cLTP (or mock) and normalized to the baseline for each individual spine. Mock: N = 98 spines across 15 cells (baseline: 1,000, cLTP: 0.989 ± 0.023, 0: 1.037 ± 0.023, 5: 1.037 ± 0.025, 10: 0.991 ± 0.028, 15: 1.032 ± 0.027, 20: 1.022 ± 0.031, 25: 1.015 ± 0.029, 30: 1.017 ± 0.028); cLTP: N = 108 spines across 15 cells (baseline: 1,000, cLTP: 1.117 ± 0.034, 0: 1.252 ± 0.057, 5: 1.347 ± 0.070, 10: 1.506 ± 0.073, 15: 1.523 ± 0.065, 20: 1.566 ± 0.066, 25: 1.651 ± 0.073, 30: 1.673 ± 0.064). Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (D) The number of puncta containing mScarlet-SNX27 in 30 µm of dendritic spines at the indicated time points was quantified for the cLTP and mock conditions and normalized to the baseline for each dendrite. Mock: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 1,000, 10: 1.020 ± 0.025, 30: 1.079 ± 0.028); cLTP: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 1,000, 10: 1.312 ± 0.049, 30: 1.544 ± 0.074). Three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance, ****P <0.001. Error bars are SEM. (E) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were co-transfected with mScarlet-SNX27 and either an empty pRK5 vector or pRK5-HA-CaMKII-T286D. 24 h later, neurons were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with an anti-HA antibody. The mean intensity of mScarlet-SNX27 was measured in the dendritic spines present in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites and normalized to mScarlet-SNX27 mean intensity in the dendritic shaft. Ctrl: 0.775 ± 0.035, N = 30 neurons; CaMKII-T286D: 0.909 ± 0.041, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, *P < 0.05. Error bars are SEM. (F) Same as E, but the number of puncta containing mScarlet-SNX27 in 30 µm of dendritic spines was quantified. Ctrl: 0.257 ± 0.016, N = 30 neurons; CaMKII-T286D: 0.365 ± 0.018, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

SNX27 is recruited to dendritic spines upon cLTP, which is dependent on the CaMKII pathway. (A) Representative confocal images from DIV17 hippocampal neurons expressing mScarlet-SNX27 and eGFP (filler) under conditions of cLTP or HBS control (mock). Images of live neurons were captured before cLTP (baseline); during cLTP; and at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min after the cLTP stimulus. Representative images of baseline, t = 10, and t = 30 are shown. Intensity presented in the fire LUT color scheme. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (B) The endpoint of the experiment (30 min) was used to measure the cLTP-dependent increase in dendritic spine width. To calculate the increase in spine size, the final spine width was normalized to the baseline width for each spine. Mock: 1.024 ± 0.025, N = 98 spines across 15 cells; cLTP: 1.498 ± 0.056, N = 108 spines across 15 cells. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (C) The mean intensity of mScarlet-SNX27 was measured in the spines that remained in the same plane at each time point following cLTP (or mock) and normalized to the baseline for each individual spine. Mock: N = 98 spines across 15 cells (baseline: 1,000, cLTP: 0.989 ± 0.023, 0: 1.037 ± 0.023, 5: 1.037 ± 0.025, 10: 0.991 ± 0.028, 15: 1.032 ± 0.027, 20: 1.022 ± 0.031, 25: 1.015 ± 0.029, 30: 1.017 ± 0.028); cLTP: N = 108 spines across 15 cells (baseline: 1,000, cLTP: 1.117 ± 0.034, 0: 1.252 ± 0.057, 5: 1.347 ± 0.070, 10: 1.506 ± 0.073, 15: 1.523 ± 0.065, 20: 1.566 ± 0.066, 25: 1.651 ± 0.073, 30: 1.673 ± 0.064). Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. (D) The number of puncta containing mScarlet-SNX27 in 30 µm of dendritic spines at the indicated time points was quantified for the cLTP and mock conditions and normalized to the baseline for each dendrite. Mock: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 1,000, 10: 1.020 ± 0.025, 30: 1.079 ± 0.028); cLTP: N = 15 dendrites (baseline: 1,000, 10: 1.312 ± 0.049, 30: 1.544 ± 0.074). Three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance, ****P <0.001. Error bars are SEM. (E) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were co-transfected with mScarlet-SNX27 and either an empty pRK5 vector or pRK5-HA-CaMKII-T286D. 24 h later, neurons were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with an anti-HA antibody. The mean intensity of mScarlet-SNX27 was measured in the dendritic spines present in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites and normalized to mScarlet-SNX27 mean intensity in the dendritic shaft. Ctrl: 0.775 ± 0.035, N = 30 neurons; CaMKII-T286D: 0.909 ± 0.041, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, *P < 0.05. Error bars are SEM. (F) Same as E, but the number of puncta containing mScarlet-SNX27 in 30 µm of dendritic spines was quantified. Ctrl: 0.257 ± 0.016, N = 30 neurons; CaMKII-T286D: 0.365 ± 0.018, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Given that PI(3)P is required for the endosomal localization of both SNX17 and SNX27, we tested whether PI(3)P also drives their recruitment to dendritic spines. Since 30-min VPS34 inhibition led to a near-complete loss of mNeonGreen-SNX17– and mScarlet-SNX27–positive puncta (Fig. S4, A–C), we applied a shorter, 10-min VPS34-IN1 treatment immediately following cLTP induction (Fig. 4 A). Unlike the prolonged inhibition, this brief treatment did not significantly affect the number of SNX17- or SNX27-positive puncta or their fluorescence intensity within dendritic spines compared with DMSO-treated cells (Fig. S6, A–D). Furthermore, this short treatment did not block the cLTP-dependent increase in SNX17 or SNX27 puncta (Fig. S6, E and F). However, in the cells that were treated with VPS34-IN1 for 10 min, the intensities of SNX17 and SNX27 in dendritic spines remained at baseline levels (Fig. 4, B–E), suggesting that although existing PI(3)P is sufficient to maintain endosomal pools of SNX17 and SNX27, de novo PI(3)P synthesis following cLTP is required to drive their accumulation in spines. Note that initiating VPS34 inhibition 5 min after cLTP does not block structural plasticity (Fig. S2, A and B), and we detect an increase in PI(3)P-positive puncta immediately after the cLTP stimulus (Fig. 1 D). Together, these findings suggest that early PI(3)P production (during or shortly after cLTP) is sufficient to support spine remodeling. It is possible that initial recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27 occurs within this early window, allowing spine plasticity to proceed despite subsequent VPS34 inhibition. Alternatively, the brief post-cLTP inhibition may limit or delay further accumulation of SNX17 and SNX27 at spines without disrupting the threshold needed for structural changes.

Brief inhibition of PI(3)P synthesis upon cLTP blocks the recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27 to dendritic spines. (A) Diagram of experiment. DIV16 hippocampal neurons were transfected with mNeonGreen-SNX17 or mScarlet-SNX27 along with a filler to visualize dendritic morphology. 24 h later, cells were treated with or without cLTP stimulation. cLTP-treated cells were washed and incubated in HBS containing either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 10 min. Cells were fixed, and the intensity of SNX17 or SNX27 at dendritic spines and in the dendritic shaft was quantified. (B) Example confocal images of DIV17 neurons expressing mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mCherry (filler) under the indicated conditions. mNeonGreen-SNX17 intensity is presented in the fire LUT color scheme to facilitate the visualization of dendritic spines. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (C) Example confocal images of DIV17 neurons expressing mScarlet-SNX27 and eGFP (filler) under the indicated conditions. mScarlet-SNX27 intensity is presented in the fire LUT color scheme to facilitate the visualization of dendritic spines. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (D) The mean intensity of mNeonGreen-SNX17 was measured in the dendritic spines present in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites and normalized to mNeonGreen-SNX17 mean intensity in the dendritic shaft. Baseline: 0.657 ± 0.026, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+DMSO: 0.823 ± 0.036, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+VPS34-IN1: 0.673 ± 0.026, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ***P < 0.005. Error bars are SEM. (E) The mean intensity of mScarlet-SNX27 was measured in the dendritic spines present in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites and normalized to mScarlet-SNX27 mean intensity in the dendritic shaft. Baseline: 0.759 ± 0.035, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+DMSO: 0.976 ± 0.060, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+VPS34-IN1: 0.729 ± 0.049, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

Brief inhibition of PI(3)P synthesis upon cLTP blocks the recruitment of SNX17 and SNX27 to dendritic spines. (A) Diagram of experiment. DIV16 hippocampal neurons were transfected with mNeonGreen-SNX17 or mScarlet-SNX27 along with a filler to visualize dendritic morphology. 24 h later, cells were treated with or without cLTP stimulation. cLTP-treated cells were washed and incubated in HBS containing either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 10 min. Cells were fixed, and the intensity of SNX17 or SNX27 at dendritic spines and in the dendritic shaft was quantified. (B) Example confocal images of DIV17 neurons expressing mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mCherry (filler) under the indicated conditions. mNeonGreen-SNX17 intensity is presented in the fire LUT color scheme to facilitate the visualization of dendritic spines. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (C) Example confocal images of DIV17 neurons expressing mScarlet-SNX27 and eGFP (filler) under the indicated conditions. mScarlet-SNX27 intensity is presented in the fire LUT color scheme to facilitate the visualization of dendritic spines. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (D) The mean intensity of mNeonGreen-SNX17 was measured in the dendritic spines present in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites and normalized to mNeonGreen-SNX17 mean intensity in the dendritic shaft. Baseline: 0.657 ± 0.026, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+DMSO: 0.823 ± 0.036, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+VPS34-IN1: 0.673 ± 0.026, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ***P < 0.005. Error bars are SEM. (E) The mean intensity of mScarlet-SNX27 was measured in the dendritic spines present in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites and normalized to mScarlet-SNX27 mean intensity in the dendritic shaft. Baseline: 0.759 ± 0.035, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+DMSO: 0.976 ± 0.060, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+VPS34-IN1: 0.729 ± 0.049, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.

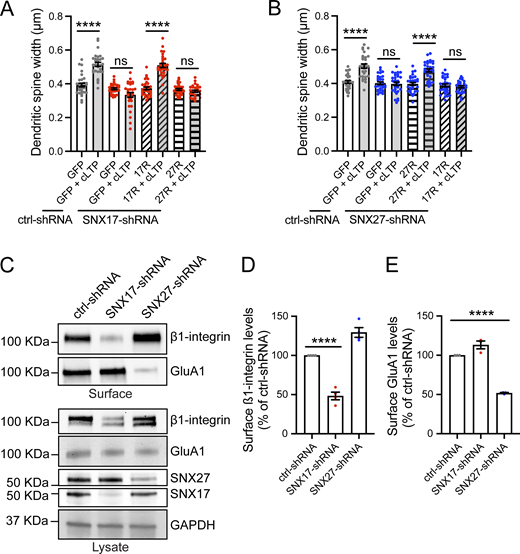

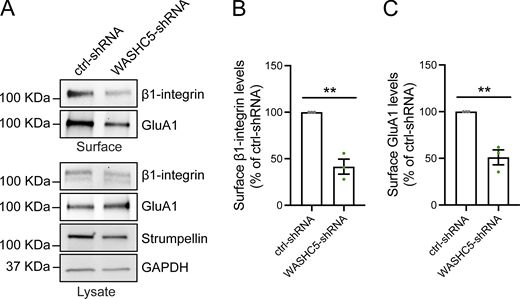

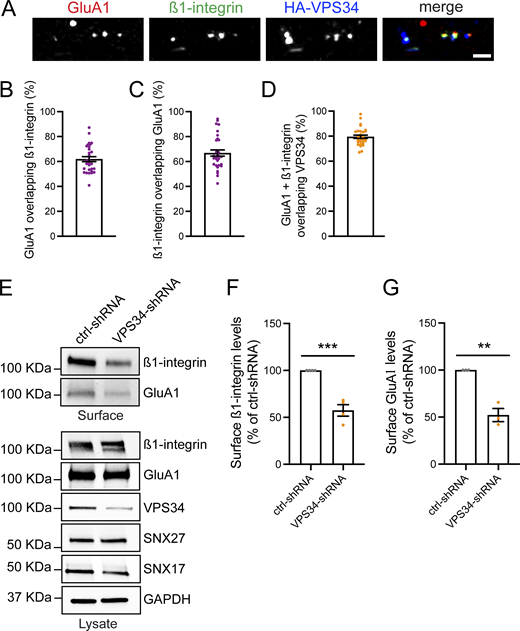

Brief 10-min inhibition of VPS34 does not affect the formation of SNX17- and SNX27-positive puncta or their recruitment to dendritic spines. (A) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were co-transfected with mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mCherry (filler). 24 h later, cells were incubated in HBS containing either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 10 min. Cells were fixed, and the number of mNeonGreen-SNX17–positive puncta in 30 µm of dendritic spines was quantified. DMSO: 0.291 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1: 0.281 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test determined that there are no significant differences between the DMSO and VPS34-IN1 conditions. Error bars are SEM. (B) Same as B, but the mean intensity of mNeonGreen-SNX17 was measured in the dendritic spines present in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites and normalized to mNeonGreen-SNX17 mean intensity in the dendritic shaft. DMSO: 0.691 ± 0.035, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1: 0.683 ± 0.037, N = 30 neurons. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test determined that there are no significant differences between the DMSO and VPS34-IN1 conditions. Error bars are SEM. (C) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were co-transfected with mScarlet-SNX27 and eGFP (filler). 24 h later, cells were incubated in HBS containing either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 10 min. Cells were fixed, and the number of mScarlet-SNX27-positive puncta in 30 µm of dendritic spines was quantified. DMSO: 0.291 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1: 0.279 ± 0.014, N = 30 neurons. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test determined that there are no significant differences between the DMSO and VPS34-IN1 conditions. Error bars are SEM. (D) Same as C, but the mean intensity of mScarlet-SNX27 was measured in the dendritic spines present in the first 30 μm of secondary dendrites and normalized to mScarlet-SNX27 mean intensity in the dendritic shaft. DMSO: 0.750 ± 0.036, N = 30 neurons; VPS34-IN1: 0.781 ± 0.038, N = 30 neurons. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test determined that there are no significant differences between the DMSO and VPS34-IN1 conditions. Error bars are SEM. (E) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were transfected with mNeonGreen-SNX17 and mCherry (filler). 24 h later, cells were treated with or without cLTP stimulation. cLTP-treated cells were washed, and incubated in HBS containing either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 10 min. Cells were fixed, and the number of mNeonGreen-SNX17–positive puncta in 30 µm of dendritic spines was quantified. Baseline: 0.253 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+DMSO: 0.343 ± 0.020, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+VPS34-IN1: 0.319 ± 0.024, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Error bars are SEM. (F) DIV16 hippocampal neurons were transfected with mScarlet-SNX27 and eGFP (filler). 24 h later, cells were treated with or without cLTP stimulation. cLTP-treated cells were washed and incubated in HBS containing either DMSO or 1 μM VPS34-IN1 for 10 min. Cells were fixed, and the number of mScarlet-SNX27–positive puncta in 30 µm of dendritic spines was quantified. Baseline: 0.246 ± 0.013, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+DMSO: 0.373 ± 0.020, N = 30 neurons; cLTP+VPS34-IN1: 0.361 ± 0.021, N = 30 neurons. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, ****P < 0.001. Error bars are SEM. DIV, days in vitro.