The transmembrane autophagy protein ATG9 has multiple functions essential for autophagosome formation. Here, we uncovered a novel function of ATG-9 in regulating lysosome biogenesis and integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Through a genetic screen, we identified that mutations attenuating the lipid scrambling activity of ATG-9 suppress the autophagy defect in epg-5 mutants, in which non-degradative autolysosomes accumulate. The scramblase-attenuated ATG-9 mutants promote lysosome biogenesis and delivery of lysosome-localized hydrolases and also facilitate the maintenance of lysosome integrity. Through manipulation of phospholipid levels, we found that a reduction in phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) also suppresses the autophagy defects and lysosome damage associated with impaired lysosomal degradation. Our results reveal that modulation of phospholipid composition and distribution, e.g., by attenuating the scramblase activity of ATG-9 or reducing the PE level, regulates lysosome function and integrity.

Introduction

Lysosomes play crucial functions in a multitude of cellular processes, including degradation of materials, nutrient sensing, signal transduction, plasma membrane (PM) repair, cell adhesion, and cell migration (Ballabio and Bonifacino, 2020; Lawrence and Zoncu, 2019). Lysosomal membrane permeabilization, triggered by various insults, may induce inflammation and cell death (Lawrence and Zoncu, 2019; Papadopoulos and Meyer, 2017). Lysosomal membranes can be repaired by multiple mechanisms, including targeting of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) or Annexins to the damaged site (Mercier et al., 2020; Radulovic et al., 2018; Skowyra et al., 2018; Shukla et al., 2022; Yim et al., 2022); physical sealing and stabilization of damaged sites by stress granules (Bussi et al., 2023); and alteration of lysosomal lipid composition (Niekamp et al., 2022; Radulovic et al., 2022; Tan and Finkel, 2022). Severely damaged lysosomes are removed by autophagy (Maejima et al., 2013). This process, called lysophagy, is triggered by the binding of cytosolic lectins, such as galectins, to lysosomal lumen-localized glycans and/or by ubiquitination of lysosomal proteins (Gahlot et al., 2024; Chauhan et al., 2016; Thurston et al., 2012; Jia et al., 2020; Teranishi et al., 2022).

One important route for cargo delivery to lysosomes is autophagy, in which double-membrane autophagosomes engulf cytosolic materials before fusing with lysosomes (Lamb et al., 2013; Nakatogawa, 2020). Autophagosomes are formed from precursors called isolation membranes (IMs), which expand and close around the cargo. Through fusion with endolysosomal vesicles, the maturing autophagosomes are gradually acidified, eventually becoming degradative autolysosomes (Zhao et al., 2021). Autophagy genes, including ATG (autophagy-related) genes and metazoan-specific EPG (ectopic PGL granules) genes, function at different steps of autophagosome formation and maturation (Mizushima, 2020; Ohsumi, 2014; Tian et al., 2010; Zhao and Zhang, 2018; Nakatogawa, 2020; Zhang, 2022). The late endosome/lysosome-localized autophagy protein EPG5 interacts with autophagosomal membrane-associated LC3 and promotes assembly of the SNARE complex to enhance fusion specificity and efficiency (Wang et al., 2016; Itakura et al., 2012). Loss of EPG5 function causes accumulation of autophagosomes and non-degradative autolysosomes resulting from non-specific fusion with intracellular vesicles (Zhao et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016). The autophagy defect in epg-5 mutants can be suppressed by elevating lysosome biogenesis/activity (Chen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). Impairment of lysosome function, for example, caused by a deficiency of digestive enzymes in the lysosomal lumen, also leads to the accumulation of non-degradative autolysosomes.

The transmembrane autophagy protein ATG9 possesses lipid scramblase activity that flips phospholipids between the two membrane leaflets (Matoba et al., 2020; Noda, 2021; Maeda et al., 2020; Orii et al., 2021). ATG9 is located on small (30–60 nm) vesicles (Guardia et al., 2020; Maeda et al., 2020; Mari et al., 2010; Matoba et al., 2020). ATG9 vesicles act at multiple steps of autophagosome formation. In yeast, they serve as seeds and recruit autophagic machinery for IM initiation (Sawa-Makarska et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2012). IM-localized ATG9 scrambles phospholipids delivered by the ATG2-ATG18 lipid transport complex for IM expansion (Gómez-Sánchez et al., 2018; Noda, 2021). In mammalian cells, in addition to scattered small vesicles, ATG9A is located in the trans-Golgi network (TGN), the PM, and endosomal compartments (Young et al., 2006). Upon autophagy induction, ATG9A vesicles derived from the TGN/endosomes shuttle to autophagosome formation sites (Webber and Tooze, 2010; Popovic and Dikic, 2014; Young et al., 2006; Orsi et al., 2012; Karanasios et al., 2013; De Tito et al., 2020). ATG9A is present on the seed vesicles and integrated into expanding IMs (Olivas et al., 2023; Broadbent et al., 2023). ATG9A-mediated lipid scrambling is essential for IM expansion (Maeda et al., 2020; Orii et al., 2021). ATG9A vesicles also deliver PI4KIIIβ to produce PI4P for autophagosome formation (Judith et al., 2019). ATG9A also functions in processes independent of autophagy. ATG9A is recruited to sites of PM damage to organize the ESCRT machinery for repair (Claude-Taupin et al., 2021). ATG9A enables lipid mobilization from lipid droplets (Mailler et al., 2021) and regulates Golgi dynamics and integrity (Luo et al., 2022). ATG9A also interacts with adaptor protein-1 (AP1) to regulate post-Golgi transport, such as the transport and maturation of lysosomal hydrolases (Jia et al., 2017).

Here, we show that mutations attenuating the lipid scramblase activity of C. elegans ATG-9 enhance lysosome biogenesis and maturation as well as suppress the autophagy defect and damaged lysosomes in epg-5 mutants and mutants depleted of lysosomal hydrolases. Our results reveal a novel function of ATG-9 in maintaining lysosome biogenesis and integrity.

Results and discussion

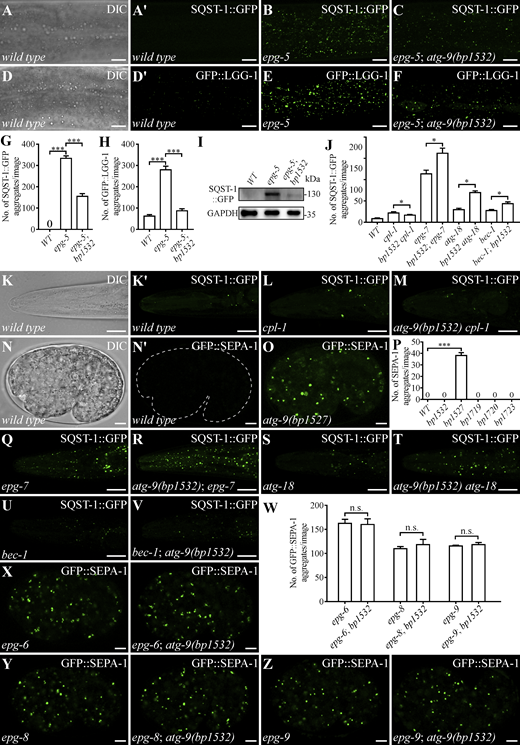

The ATG-9(C475F) mutation suppresses the autophagy defect in epg-5 mutants

We performed genetic screens in C. elegans to identify mutations that suppress the autophagy defect in epg-5(tm3425) null mutants (tm3425 mutants, hereafter referred to as epg-5 mutants, were used throughout this study). In wild-type embryos, SEPA-1 aggregates are detected at early embryonic stages and absent at the comma stage and onwards (Fig. 1, A, A′, and C). In epg-5 mutants, numerous SEPA-1 aggregates accumulate throughout embryonic stages (Fig. 1, B and C) (Zhang et al., 2009, 2018; Zheng et al., 2023). We identified bp1607, which suppressed the number of SEPA-1 granules in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 1, C and D). Accumulation of endogenous SQST-1 aggregates (the C. elegans homolog of p62) in epg-5 mutants was also reduced by bp1607 (Fig. 1, K–N). epg-5 mutants accumulate numerous LGG-1 puncta (the C. elegans Atg8 homolog), and this accumulation was also rescued by bp1607 (Fig. 1, O–R). Simultaneous depletion of lgg-1 in epg-5; bp1607 mutants restored the accumulation of SEPA-1 aggregates (Fig. 1, C and E), indicating that bp1607 facilitates autophagic degradation of protein aggregates in epg-5 mutants.

Using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)–based genetic mapping, bp1607 was mapped between 21.01 and 19.83 on linkage group V. Whole-genome sequencing identified a single mutation within this region, specifically a cysteine (Cys, C) to phenylalanine (Phe, F) mutation at residue 475 of ATG-9. Transgenes expressing wild-type atg-9 restored accumulation of SEPA-1 aggregates in epg-5; bp1607 animals (Fig. 1, C and F). Overexpression of a plasmid encoding ATG-9(C475F) in epg-5 mutants also promoted the degradation of SEPA-1 aggregates (Fig. 1, C and G). To eliminate the possibility that other ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS)–induced mutations contribute to the suppression effect, we introduced the C475F mutation into endogenous ATG-9 by CRISPR/Cas9. This mutation, bp1532, suppressed the autophagy defect in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 1, C and H; and Fig. S1, A–I). The mutant allele atg-9(bp1527), which carries a 32-bp deletion in the coding region and introduces a stop codon at residue 556 (hereafter referred to as atg-9(null)), failed to suppress the defect in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 1, C and I). CPL-1, the ortholog of cathepsin L, is essential for cargo degradation and maintaining lysosomal membrane stability (Zhang et al., 2023). The number of SQST-1::GFP aggregates was reduced in atg-9(bp1532) cpl-1 double mutants compared with cpl-1 single mutants (Fig. S1, J–M). Thus, atg-9(bp1532) mitigates the autophagy defect resulting from EPG-5 depletion and impaired lysosome function.

atg-9(bp1532) slightly enhances the autophagy defect caused by hypomorphic mutations in autophagy genes involved in autophagosome formation

atg-9(null) mutants, like other autophagy mutants, accumulated a large number of SEPA-1 aggregates (Fig. S1, N–P). However, atg-9(bp1532) mutants showed no evident autophagy defect in the degradation of SEPA-1 aggregates (Fig. 1 J and Fig. S1 P).

We next investigated the genetic interactions between atg-9(bp1532) and other autophagy mutants. EPG-7 acts as a scaffold protein facilitating SQST-1 degradation (Lin et al., 2013). epg-7 mutants show an accumulation of SQST-1 aggregates that is suppressed by enhanced autophagy activity (Fig. S1, J and Q) (Lin et al., 2013). The number of SQST-1 aggregates was slightly increased in atg-9(bp1532); epg-7 mutants compared with epg-7 single mutants (Fig. S1, J and R). atg-9(bp1532) also increased the number of SQST-1 aggregates in atg-18(bp594) and bec-1(bp613) mutants, both of which are hypomorphic alleles (Zhang et al., 2015) (Fig. S1, J and S–V). The number of SEPA-1 aggregates in null mutants of autophagy genes involved in autophagosome formation, including epg-6, epg-8, and epg-9 (homologs of WIPI4, ATG14, and ATG101, respectively) (Liang et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2011; Yang and Zhang, 2011), was not further enhanced by atg-9(bp1532) mutation (Fig. S1, W–Z). Therefore, atg-9(bp1532) slightly enhances the defect caused by hypomorphic mutations in genes involved in autophagosome formation.

Mutations attenuating the scramblase activity of ATG-9 suppress the defect in epg-5 mutants

Human ATG9A is a homotrimer. Each monomer contains six membrane-penetrating domains: four transmembrane α-helices (TM1-4) and two reentrant membrane α-helices (RM1-2) (Maeda et al., 2020; Guardia et al., 2020). Trimeric ATG9A possesses a central pore for lipid scrambling (Maeda et al., 2020; Guardia et al., 2020). Charged residues in RM1 (Lys321, Arg322, and Glu323) and small amino acids in TM4 (Thr412, Gly415, and Thr419) constitute the wide, hydrophilic middle region of the central pore (Maeda et al., 2020). Point mutations in TM4 (Tyr661, Thr663, Gly666, and Ser670) of budding yeast Atg9 and equivalent mutations in human ATG9A (Thr410, Thr412, Gly415, Thr419) severely impair the scramblase ability (Matoba et al., 2020). ATG-9 Cys475, corresponding to Leu414 in human ATG9A, locates in TM4 of ATG9 and within the “central pore” of the ATG-9 homotrimer (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S2 A). We generated CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations in TM4 of ATG-9, including bp1719 (Gly/G to Trp/W at residue 476, which corresponds to Gly415 of human ATG9A) and bp1720 (Arg/R to Trp/W at residue 483), to alter the width and hydrophilicity of the central pore (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S2 A). These mutations promoted the removal of SEPA-1 aggregates in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 2, C, D, and F; and Fig. S2, B and B′). However, the bp1721 mutation (Cys/C to Ser/S at residue 475) and the bp1722 mutation (Gly/G to Ser/S at residue 476), which are unlikely to alter the pore size, showed no rescuing activity (Fig. 2 F; and Fig. S2, C and D).

The triple mutation (K321L R322L E323L) in RM1 of ATG9A also impairs lipid scrambling (Maeda et al., 2020). Expression of human ATG9A(K321L R322L E323L) in epg-5 mutants rescued the autophagy defect (Fig. 2 F; and Fig. S2, A and E). We introduced the same mutations into the endogenous atg-9 locus to create bp1723 (K382L, R383L, R384L) (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S2 A). bp1723 also promoted the degradation of SEPA-1 aggregates in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 2, E and F). atg-9(bp1719), atg-9(bp1720), and atg-9(bp1723) mutants displayed no autophagy defect (Fig. S1 P and Fig. S2, F–L). Thus, attenuating the lipid-scramblase activity of ATG-9 causes no evident autophagy defect but rescues the defects in epg-5 mutants.

ATG-9(C475F) promotes lysosome biogenesis

ATG-9(C475F) specifically suppresses the autophagy defect resulting from lysosome dysfunction, prompting us to examine lysosomal activity. In the hypodermis of wild-type animals, NUC-1 (lysosomal DNase II) labeled spherical lysosomes (Fig. 3 A). In atg-9(bp1532) mutants, NUC-1–labeled lysosomes were more abundant (Fig. 3, B and C). epg-5 mutants contained enlarged lysosomes (Fig. 3, D and F), while more small lysosomes were detected in epg-5; atg-9(bp1532) mutants (Fig. 3, E, F, and G). atg-9(bp1532) also reduced the lysosomal volume in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 3 H). atg-9(null) mutants contained fewer lysosomes, which were enlarged and clustered (Fig. 3, C, F, and I). The lysosome phenotype in epg-5; atg-9(null) double mutants resembled atg-9(null) single mutants (Fig. 3, C, G, I, and J). mRNA levels of 24 genes involved in lysosome biogenesis and function were unchanged in atg-9(bp1532) mutants (Fig. S2 M and Table S1). Thus, ATG-9(C475F) does not promote the transcription of lysosomal genes.

We next used the Phsp-16::NUC-1::superfolder GFP (sfGFP)::mCherry reporter, in which NUC-1 expression is driven by the hsp-16 heat shock promoter, to follow the delivery of lysosome-localized NUC-1 (Miao et al., 2020). After synthesis in the ER, NUC-1 is secreted into the extracellular space and then delivered to lysosomes via endocytosis. Animals carrying this reporter are heat shocked at 33°C for 30 min and then grown at normal temperature (20°C). Delivery of NUC-1 to lysosomes is monitored at different times after heat shock. In wild-type animals, 3 h after heat shock, abundant green (due to faster folding of sfGFP than mCherry) and yellow lysosomes were detected (Fig. S3, A and G). The number of red-only puncta (due to quenching of the GFP signal in acidic organelles) gradually increased over time, but the yellow puncta still persisted 12 h after heat shock (Fig. S3, A and G). More red-only signals were observed in atg-9(bp1532) mutants from 6 h onward, and almost all were red by 12 h (Fig. S3, B and G). epg-5 mutants and atg-9(null) mutants contained more green/yellow puncta at late time points (Fig. S3, C, D, and G). In epg-5; atg-9(bp1532) mutants, more red-only signals were detected than in epg-5 single mutants (Fig. S3, E and G), while the green/yellow signals disappeared slowly in epg-5; atg-9(null) mutants (Fig. S3, F and G). Thus, ATG-9(C475F) accelerates the delivery of NUC-1::sfGFP::mCherry into lysosomes or promotes lysosomal acidification.

ATG-9(C475F) facilitates the maintenance of lysosome integrity

We used the Galectin-3 (sfGFP::Gal3) reporter to assess lysosome integrity in epg-5 mutants (Li et al., 2016; Paz et al., 2010). sfGFP::Gal3 signal was diffuse in the cytoplasm in wild-type animals, while it was concentrated in many irregular-shaped puncta in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 3, A, D, and K). The number of sfGFP::Gal3-labeled puncta gradually increased in aged epg-5 mutants (Fig. 3, L and M). epg-8 mutants and epg-9 mutants showed no accumulation of enlarged lysosomes and sfGFP::Gal3-labeled damaged lysosomes (Fig. S3, H and I). In epg-5; atg-9(bp1532) double mutants, sfGFP::Gal3 puncta were absent and the signal became diffuse in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3, E, K, and N). The sfGFP::Gal3-positive puncta in epg-5 mutants were labeled by the lysosomal membrane marker SCAV-3::tagRFP-T (Fig. 3, O and P). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that in the hypodermis of wild-type animals, lysosomes were predominantly spherical with electron-dense contents (type I lysosomes) (Fig. 3, Q and S). Lysosomes with peripheral whorl-like membrane structures (type II) or lucent contents (type III) were also detected but at a low frequency (Fig. 3, Q and S). However, epg-5 mutants accumulated enlarged type II lysosomes and type III lysosomes with a damaged membrane (Fig. 3, R and S). Accumulation of enlarged abnormal lysosomes was largely suppressed in epg-5; atg-9(bp1532) mutants, judged by TEM (Fig. 3 S; and Fig. S3, J and K). Thus, atg-9(bp1532) suppresses the accumulation of damaged lysosomes in epg-5 mutants. The accumulation of sfGFP::Gal3 puncta was more pronounced and the puncta were larger in epg-5; atg-9(null) double mutants (Fig. 3, J and K), indicating that depletion of ATG-9 exacerbates lysosome damage in epg-5 mutants.

We next investigated whether atg-9(bp1532) rescues damaged lysosomes in other mutants. ClC-7, a lysosomal Cl−/H+ exchanger, transports Cl− into the lysosomal lumen (Brandt and Jentsch, 1995). Loss of ClC-7 function impairs cargo degradation and perturbs lysosomal membrane integrity (Kasper et al., 2005; Pressey et al., 2010). Mutations in the C. elegans ClC-7 homolog CLH-6 also cause lysosome dysfunction (Zhang et al., 2023). The number of lysosomes was reduced and sfGFP::Gal3 formed distinct puncta in clh-6(RNAi) mutants (Fig. S3, L, N, and O). These defects were markedly rescued in atg-9(bp1532) clh-6(RNAi) mutants (Fig. S3, M–O). atg-9(bp1532) also increased the number of lysosomes and rescued the lysosome damage in cpl-1(RNAi) mutants (Fig. S3, N–Q). Thus, atg-9(bp1532) promotes lysosome biogenesis and facilitates the preservation of lysosome integrity.

ATG-9 colocalizes with lysosomes

ATG-9 is widely distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Stavoe et al., 2016). ATG-9 and ATG-9(C475F) displayed the same distribution pattern and colocalized with only a few NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes (Fig. 4, A, B, and E). In epg-5 mutants, small ATG-9 dots more frequently colocalized with or surrounded lysosomes (Fig. 4, C and E). The lysosomes decorated with ATG-9 dots were not labeled by Gal3::GFP but exhibited weak NUC-1::mCherry signals in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 4 C), consistent with mild lysosome damage (Zhang et al., 2023). We used NUC-1::pHTomato, which exhibits reduced fluorescence intensity in lower pH environments (Li and Tsien, 2012; Sun et al., 2020), to examine lysosomal acidification. Compared with wild-type animals, NUC-1::pHTomato-labeled puncta in epg-5 mutants were much more intense, indicating defective lysosomal acidification (Fig. 4, F and G). ATG-9 puncta were localized/associated with lysosomes with bright NUC-1::pHTomato signal in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 4, F and G). In epg-5; atg-9(bp1860) double mutants, only a few ATG-9(C475F) puncta colocalized with lysosomes, resembling the pattern in wild-type animals (Fig. 4, D and E). The NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes in epg-5 mutants and cpl-1(RNAi) mutants that were surrounded by ATG-9 dots showed no colocalization with LGG-1 puncta, indicating that lysosomal recruitment of ATG-9 occurs independently of LGG-1 (Fig. 4, H–J). These results suggest that ATG-9(C475F) may promote the repair of mildly damaged lysosomes.

Reducing the phosphatidylethanolamine level rescues the autophagy defect in epg-5 mutants

We next investigated whether alterations in phospholipids cause a similar effect to ATG-9(C475F). The most abundant phospholipids include phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), sphingomyelin (SM), and cardiolipin (CL). We knocked down genes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis in epg-5 mutants and then examined the autophagy phenotype (Fig. 5 A and Table S2). Knocking down pcyt-2.1 or ept-1 facilitated autophagic clearance of the accumulated SEPA-1 aggregates in epg-5 embryos (Fig. 5, B–E). pcyt-2.1 encodes a homolog of the mammalian ethanolamine phosphate cytidylyltransferase 2 (PCYT2). PCYT2 catalyzes the conversion of choline phosphotransferase and phosphoethanolamine to cytidine diphosphate (CDP)-ethanolamine, a precursor for PE synthesis. ept-1 encodes EPT-1, a homolog of the mammalian ethanolamine phosphotransferase 1, which mediates the transfer of phosphoethanolamine from CDP-ethanolamine to diacylglycerol to produce PE (Fig. 5 A). Thus, reducing the expression of pcyt-2.1 or ept-1 likely leads to a decrease in cellular PE levels. Knocking down genes involved in the biosynthesis of PC, PS, PI, and CL failed to rescue the epg-5-associated autophagy defect (Fig. 5, F–H).

Loss of ept-1 function increased the number of lysosomes and rescued the accumulation of sfGFP::Gal3-labeled damaged lysosomes in epg-5 mutants (Fig. 5, I–L). ATG-9 colocalized with only a few NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes in ept-1(RNAi) animals, suggesting that reduced PE levels do not affect the distribution of ATG-9 on lysosomes (Fig. 5 M). Thus, a reduced PE level, similar to scramblase-attenuated atg-9 mutants, promotes lysosome biogenesis and rescues the autophagy defect and damaged lysosomes caused by epg-5 depletion (Fig. 5 N).

Our study expands the repertoire of ATG9 functions in the autophagy-lysosomal pathway. atg-9 mutants with attenuated scramblase activity do not exhibit an evident defect in autophagy, indicating that partially retained scramblase activity is sufficient for the activity of ATG-9 at early steps of autophagosome formation. ATG-9 facilitates lysosome function and also maintains lysosome integrity. In atg-9(null) mutants, delivery and/or maturation of lysosome-localized enzymes is hindered, and damaged lysosomes accumulate. Consistent with a function of ATG-9 in lysosome repair, ATG-9 vesicles in epg-5 mutants colocalize with or surround mildly damaged lysosomes that show weak NUC-1 signals, are Gal3-negative, and are separate from LGG-1–labeled structures. Surprisingly, the scramblase-attenuated atg-9 mutations elevate lysosome function and repair in mutants with impaired lysosomal degradation. Thus, the scramblase activity of ATG-9 exacerbates lysosome dysfunction and damage and must be precisely controlled to coordinate autophagic flux at different steps.

Each lipid species has a characteristic shape (e.g., PE is conical), and therefore the local membrane landscape, including the degree of curvature, depends on the composition and spatial distribution of lipids (van Meer et al., 2008). Spontaneous membrane curvature is critical in membrane remodeling processes such as membrane fusion, fission, and repair (Ernst et al., 2016; Janmey and Kinnunen, 2006). Not surprisingly, alteration of lysosomal lipid composition drives lysosome repair. For example, lysosome repair is promoted by the transfer of cholesterol or PS from the ER to damaged lysosomes at the ER–lysosome contact sites (Tan and Finkel, 2022; Radulovic et al., 2022; Cross et al., 2023), or by an increase in the generation of ceramide on the cytosolic side of damaged lysosomes (Niekamp et al., 2022). We found that reduced PE synthesis also rescues the autophagy defect and facilitates lysosome repair in epg-5 mutants. ATG-9 may function in lysosomes, the ER, or other organelles that contact with lysosomes to modulate the lipid composition of lysosomes for lysosome repair. Attenuation of the scramblase activity of ATG-9 or a reduction in the PE level directly or indirectly alters the distribution of phospholipids between the inner and outer leaflets of lysosomal membranes, thus creating membrane curvature to facilitate lysosome biogenesis and repair.

Scramblase-attenuated ATG-9 or a reduced PE level may also enhance lysosome integrity by suppressing the generation of damaged lysosomes. ATG9A interacts with AP1 and facilitates the TGN-to-lysosome transport of lysosomal hydrolases (Jia et al., 2017). This process is hindered by the scramblase activity of ATG-9. Spontaneous membrane curvature regulates membrane fusion and fission involved in vesicle transport (Ernst et al., 2016; Janmey and Kinnunen, 2006). Facilitated delivery and/or maturation of lysosomal enzymes by scramblase-attenuated ATG-9 or reduced PE may promote the degradative capacity of lysosomes, thus preventing the build-up of undegraded autolysosomes and consequently of damaged lysosomes. Impaired lysosome function and integrity are associated with lysosome storage diseases and neurodegenerative diseases (Bajaj et al., 2019; Platt et al., 2012). The scramblase activity of ATG-9 provides a potential druggable target to ameliorate the pathogenesis of diseases associated with lysosome dysfunction.

Materials and methods

Worm strains

The following C. elegans strains were used in this study: N2 Bristol (wild-type), atg-9(bp1532), atg-9(bp1527). atg-9(bp1719), atg-9(bp1720), atg-9(bp1721), atg-9(bp1722), atg-9(bp1723), atg-9(ola274[atg-9::gfp]), atg-9(bp1860[atg-9(c475f)::gfp]), epg-5(tm3425), epg-7(tm2508), atg-18(bp594), bec-1(bp613), epg-6(bp242), epg-8(bp251), epg-9(bp320), cpl-1(qx304), bpIs151(Psqst-1::sqst-1::gfp+unc-76), bpIs443(sqst-1::gfp), qxIs257(Pced-1::nuc-1::mCherry+unc-76), qxIs612(Phsp::nuc-1::sfgfp::mCherry+unc-76), qxIs582(Phyp7::sfgfp::Gal3+unc-76), qxIs870(Phyp7::bfp::Gal3+unc-76), qxIs750(Phsp-16::NUC-1::pHTomato+Pord-1::GFP), qxIs779(Pscav-3::SCAV-3::tagRFP-T+unc-76), bpIs303(Plgg-1::bfp::lgg-1+rol-6), sepa-1(bp1365[gfp::sepa-1]), qxSi13(Plgg-1::gfp::lgg-1).

Mapping and cloning of atg-9(bp1607)

epg-5(tm3425) mutants (for simplicity, also written as epg-5(null)) carrying the GFP::SEPA-1 reporter were used for EMS-mediated chemical mutagenesis. Approximately 3,000 genomes were screened for suppression of the accumulation of GFP::SEPA-1 aggregates in epg-5 mutants, leading to the identification of the bp1607 mutation. bp1607 was mapped to linkage group V by SNP mapping. Transgenes carrying a PCR fragment covering atg-9 restored the accumulation of GFP::SEPA-1 aggregates in epg-5(null); bp1607 mutants. Sequencing revealed a mutation in the coding region of atg-9, resulting in the substitution of cysteine at position 475 with phenylalanine.

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in C. elegans

atg-9 mutations, including atg-9(bp1532), atg-9(bp1527), atg-9(bp1719), atg-9(bp1720), atg-9(bp1721), atg-9(bp1722), atg-9(bp1723), and atg-9(bp1860), were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 editing. The guide RNA (sgRNA) target sequences in atg-9 were cloned into the pDD162 vector, which expresses Cas9 protein and sgRNA in C. elegans. The repair templates (containing the edited sequence and homologous arms of the target region) and sgRNA plasmids (Table S3), together with a co-marker plasmid (e.g., pRF4(rol-6)), were injected into the gonad of young adult animals. The Roller F1 animals were selected to identify edited candidates. Positive candidates were verified by sequencing and then outcrossed.

RNAi in C. elegans

For RNAi feeding, embryos were placed on RNAi feeding plates in which the RNAi bacteria were induced to express the target double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (e.g., ds-ept-1) by 1 mM IPTG. For RNAi injection, dsRNA was synthesized using the RNA production system SP6 and T7 kits (P1300 and P1280; Promega) and injected into young adult animals.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay

Embryos were collected from 80 to 100 gravid hermaphrodites and placed on polylysine slides (1%), followed by freeze-cracking using liquid nitrogen, methanol (−20°C for 20 min), and acetone (−20°C for 15 min). The samples were blocked with PBS (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 2 mM KH2PO4) containing 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were then incubated with primary antibodies against SQST-1 (rat, 1:1,000; Tian et al., 2010) and LGG-1 (rat, 1:1,000; Tian et al., 2010) overnight at 4°C. The samples were then washed three times with PBST (PBS +0.2% Tween 20) and incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 AffiniPure goat anti-rat IgG secondary antibodies (1:200; Cat# 112-035-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch; RRID: AB_2338128) for 2 h at 20°C. Finally, the samples were washed three times with PBST, stained with DAPI, mounted on slides, and subjected to imaging analysis.

TEM analysis

Day 1 adult animals were rapidly frozen using a high-pressure freezer (EM HPM100; Leica Biosystems). Freeze substitution was conducted in anhydrous acetone containing 1% osmium tetroxide. The samples were maintained at −90°C for 72 h and then gradually warmed to −60°C for 12 h and −30°C for 10 h before reaching 0°C in a freeze-substitution unit (EM AFS2; Leica Biosystems). After substitution, the samples were washed three times (15 min per wash) in fresh anhydrous acetone and post-fixed overnight at 4°C in anhydrous acetone containing 0.5% uranyl acetate. Resin infiltration was carried out in a graded series of Embed-812 resin: 1:3 resin/acetone for 3 h, 1:1 for 5 h, 3:1 overnight, followed by 100% resin infiltration for 2, 12, and 12 h. Polymerization was completed at 60°C for 48 h. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were prepared using an ultramicrotome (EM UC7; Leica Biosystems) and examined under a transmission electron microscope (H-7800; Hitachi) at 100 kV. Digital images were acquired using an AMT CCD camera (MoradaG3; EMSIS). Lysosomes (n > 100) were manually counted. The proportion of damaged lysosomes was determined based on morphological criteria.

Quantification of lysosome volume

Day 1 adult animals expressing NUC-1::mCherry were immobilized on agar pads in a buffer containing 5 mM levamisole. Fluorescence images were acquired at room temperature using a spinning-disk confocal scanner unit (UltraView; PerkinElmer) equipped with a 60× oil immersion objective (CFI Plan Apochromat Lambda, NA 1.40; Nikon). Imaging was performed using a 561 nm laser in combination with a dual-band emission filter (445 nm, W60). A series of 15–20 z-stack images (0.5 μm per section) was collected. Serial optical sections were analyzed, and the volume of NUC-1::mCherry-positive lysosomes was quantified using Volocity software (PerkinElmer). A minimum of 10 animals per genotype were analyzed, and statistical analysis was conducted with GraphPad Prism 5 using Student’s t test (two-tailed).

Immunoblotting assay

L4 larvae were subjected to repeated high-temperature (100°C) and liquid nitrogen treatments. The extracts were then separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After incubation with the primary and secondary antibodies, the target protein was detected using a ChemiScope3300 Mini (Clinx Science) imaging system. The primary antibodies used included GFP (rat; 1:1,000; Cat# 11814460001; Sigma-Aldrich; RRID: AB_390913) and GAPDH (rat; 1:5,000; Cat# P01L081; Gene-protein Link). The secondary antibody used was Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-rat IgG (1:5,000; Cat# 112-035-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch; RRID: AB_2338128).

Imaging, quantification, and statistical analysis

To quantify the number of GFP::SEPA-1 aggregates, GFP::LGG-1 aggregates, SQST-1::GFP aggregates, NUC-1::mCherry puncta, and the area of sfGFP::Gal3 puncta, images were captured using Zeiss LSM880 microscopes with 405, 488, and 561 lasers, a 63×/1.40 oil-immersion objective lens (Plan-Apochromat; Zeiss) and a camera (Axiocam HRm; Zeiss) at room temperature (20–25°C). For the experimental and control groups, animals at the same developmental stage and of similar body size were used, and imaging conditions (laser intensity, exposure time, and magnification) were the same. Image quantification was performed using ZEN lite 2011, and statistical analysis was conducted with GraphPad Prism 5. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using Student’s t test (two-tailed), while multiple group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Results are presented as mean ± SEM; n.s. indicates no significant difference (P > 0.05), * denotes P < 0.05, ** denotes P < 0.01, and *** denotes P < 0.001.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the genetic interaction of atg-9(bp1532) with autophagy mutants. Fig. S2 shows that ATG-9 mutations with reduced scramblase activity suppress defects in epg-5 null mutants. Fig. S3 shows that ATG-9(C475F) accelerates the delivery of NUC-1::sfGFP::mCherry into lysosomes. Table S1 lists quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) primers used in this study. Table S2 shows a list of phospholipid synthesis genes screened by RNAi in epg-5 mutants. Table S3 lists sgRNAs and repair templates for generating atg-9 mutations.

Data availability

The reagents are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Isabel Hanson for editing work.

This work was supported by the following grants to H. Zhang: The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 82188101) and the New Cornerstone Science Foundation; and the following grant to N.N. Noda: CREST, Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJCR20E3).

Author contributions: K. Peng: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, G. Zhao: Investigation, H. Zhao: Investigation, N.N. Noda: Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing - review & editing, H. Zhang: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

References

H. Zhang is the lead contact.

Author notes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests exist.

![ATG-9 is recruited to damaged lysosomes. (A–D) ATG-9::GFP puncta (A) and ATG-9(C475F)::GFP puncta (B) are broadly distributed, and occasionally co-localize with or associate with NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes (indicated by white arrows). In epg-5 mutants, ATG-9::GFP puncta (C) surround NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes. The distribution pattern of ATG-9(C475F) is similar to the wild-type pattern in epg-5 mutants (D). The bp1860 allele, introducing the C475F mutation into endogenous ATG-9, was generated by CRISPR/Cas9 in the atg-9(ola274[atg-9::gfp]) background. The white arrows indicate the spatial relationship between NUC-1::mCherry and ATG-9::GFP/ATG-9(C475F)::GFP (enlarged in the inserts). (E) Quantification of the number of NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes surrounded with ATG-9/ATG-9(C475F) shown in A–D (n = 3 animals for each genotype). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; ***, P < 0.001. (F and G) Worms carrying Phsp-16::NUC-1::pHTomato (L4 stage) were heat-shocked at 33°C for 30 min, then returned to normal growth conditions (20°C) for a 24-h recovery period before observation. Compared with wild-type animals (F), the fluorescence intensity of NUC-1::pHTomato is markedly increased in epg-5 mutants (G). Notably, ATG-9::GFP is observed to localize adjacent to brightly labeled NUC-1–positive lysosomes, as indicated by cyan arrows. The white arrows indicate the spatial relationship between NUC-1::pHTomato and ATG-9::GFP (enlarged in the inserts). (H–J) The distribution of NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes, ATG-9::GFP structures, and LGG-1–labeled autophagic structures. In wild-type animals, ATG-9::GFP puncta occasionally co-localize with NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes (indicated by white arrows and also enlarged in the inserts) (H). In epg-5 null mutants (I) and cpl-1(RNAi) mutants (J), ATG-9::GFP puncta surround NUC-1::mCherry-labeled lysosomes, but they are separated from BFP::LGG-1–labeled structures (indicated by white arrows and also enlarged in the inserts). Scale bars: 10 µm for A–D and F–J; 1 µm for enlarged images in A–D and F–J.](https://cdn.rupress.org/rup/content_public/journal/jcb/224/6/10.1083_jcb.202411092/1/m_jcb_202411092_fig4.png?Expires=1773060177&Signature=Snudg2Bh1Kywd422g~CdbrGn~Ibqy9jK0r27CDs5ijxeJVw3t2LXYZ9f6CaMe~EFT9lEnwxSF7VO~xFyGpKegqAljtZey48KtZMwJvYYUSSw-I3WKJn5wExmwoD6Q02GK0RMGFlNGCrsHOzSd9Ikf4J~HnNPsNgGqXQMhkI75hwzOkowKX0cxbh-z2pIRVcjvgJyZGlxZiFEVcY81gZFrs7SLJsHtPIFsf-Yyg03Vfuht1Fau~8Ha06PL-ErR-~8SdkCVmEYcxqcTVaUdiCZe6Ll58j-WhZjwkVrfORqP5G97k~qqAtQloZddY-6hXvnjNPrT9JZ3rATRRGfM2DkKA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)