Autophagy plays a crucial role in cancer cell survival by facilitating the elimination of detrimental cellular components and the recycling of nutrients. Understanding the molecular regulation of autophagy is critical for developing interventional approaches for cancer therapy. In this study, we report that migfilin, a focal adhesion protein, plays a novel role in promoting autophagy by increasing autophagosome–lysosome fusion. We found that migfilin is associated with SNAP29 and Vamp8, thereby facilitating Stx17-SNAP29-Vamp8 SNARE complex assembly. Depletion of migfilin disrupted the formation of the SNAP29-mediated SNARE complex, which consequently blocked the autophagosome-lysosome fusion, ultimately suppressing cancer cell growth. Restoration of the SNARE complex formation rescued migfilin-deficiency–induced autophagic flux defects. Finally, we found depletion of migfilin inhibited cancer cell proliferation. SNARE complex reassembly successfully reversed migfilin-deficiency–induced inhibition of cancer cell growth. Taken together, our study uncovers a new function of migfilin as an autophagy-regulatory protein and suggests that targeting the migfilin–SNARE assembly could provide a promising therapeutic approach to alleviate cancer progression.

Introduction

Macroautophagy (henceforth referred to as autophagy) is an intracellular dynamic and evolutionary-conserved lysosome-mediated degradation process (Tian et al., 2021; Yun and Lee, 2018). An autophagic process involves autophagic initiation, crescent-shaped phagophore formation and maturation, autophagosome–lysosome fusion, and degradation (Li et al., 2020a; Wang et al., 2016). Autophagy initiation could be triggered by several intracellular or extracellular stimuli, such as oxidative stress, serum or amino acid starvation, and mTOR inhibition (He and Klionsky, 2009; Hosokawa et al., 2009; Mizushima, 2007; Ureshino et al., 2014). Multiple autophagy-related (Atg) proteins are hierarchically engaged into the ULK1 complex, followed by the recruitment of PI3K complex and ATG9A system to form phagophore (Li et al., 2020a). A crescent-shaped phagophore expands continuously, and elongation during expansion phase is facilitated by Atg12-Atg5 and Atg8/LC3 ubiquitin-like Atg conjugation system to form closed autophagosome (Hanada et al., 2007; Ichimura et al., 2000). Sequentially, autophagosome fuses with late endosome/lysosome to form amphisome/autolysosome, and delivered cargos are degraded to recycle cellular materials (Zhao and Zhang, 2019). In mammalian cells, fusion is mainly mediated by Syntaxin 17 (Stx17, Qa SNARE), Synaptosomal-associated protein 29 (SNAP29, Qbc SNARE), and endosomal/lysosomal Vamp8 (R-SNARE) (Behrendorff et al., 2011; Hegedűs et al., 2013; Morelli et al., 2014). Stx17 contains two transmembrane domains (TMs) and localizes into an autophagosome. SNAP29 localizes at cytosol; it lacks a transmembrane domain but transiently associates with the membrane through interaction with Stx17 and Vamp8. Vamp8 contains a transmembrane domain and localizes into endosome/lysosome (Tian et al., 2021). Autophagic fusion is regulated by several factors, including HOPS complex (which is recruited by autophagosome-localized Stx17 and interacts with endosomal/lysosomal Rab7 to promote fusion), PLEKHM1 (which interacts with LC3/GABARAP, HOPS, and Rab7 to facilitate autolysosome formation), TECPR1 (which binds to ATG12-ATG5 conjugate and PI3P), ATG14 (which directly binds to SNAP29-Stx17 binary complex), and EPG5 (which binds to LC3 and Rab7 and recruited by WDR45/WDR45B in neural cells) (Chen et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015a; McEwan et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Loss of these factors impairs autophagic fusion, which may result in serious diseases, such as Vici syndrome and intellectual disability (Ji et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021). In addition, the SNARE protein posttranslational modifications also regulate autophagosome–lysosome fusion. It’s reported that Stx17 acetylation, SNAP29 O-GlcNAcylation, and Vamp8 phosphorylation all reduce spontaneous autophagosome–lysosome fusion (Guo et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2021; Wang and Diao, 2022). Autophagy plays critical roles in numerous cellular functions, including cell survival, cell cycle, metabolic adaptation, molecular metastasis, and organelles renewal (Jung et al., 2020; Morishita and Mizushima, 2019; Zheng et al., 2019). In addition, autophagy dysfunction is a highlighted characteristic of various diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic syndromes, and cancers (Klionsky et al., 2021b).

Pancreatic cancer is a highly fatal malignancy with a 5-year survival rate <10% due to diagnosis deficiency and therapy limitation (Mizrahi et al., 2020; Siegel et al., 2020; Singhi et al., 2019). Therefore, it’s urgent to understand the molecular mechanism of cancer progression and identify putative diagnostic and therapeutic targets for pancreatic cancer. Pancreatic cancer is a highly dense solid tumor that is characterized by nutrient deprivation, diffusion-limited hypoxia, waste accumulation, and therapy resistance (Huang et al., 2019; Mizrahi et al., 2020). Autophagy is highly activated and required for cancer pathogenesis by regulating cancer cell survival and metabolism (Li et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2011). Therefore, the development of therapy targeting autophagy may be a reasonable and reliable clinical strategy to suppress cancer growth.

Migfilin (also named filamin-binding LIM protein 1, FBLP-1) was identified as a binding partner of Kindlin-2 at focal adhesions (Tu et al., 2003). It contains an intrinsic disordered N terminal, proline-rich domain (PRD), and three LIM domains-containing C terminal. Migfilin is recruited into focal adhesions by Kindlin-2 and mediates the linkage of focal adhesions and actin cytoskeletons (Tu et al., 2003). Cellular migfilin interacts with various intracellular proteins, including β-catenin, VASP, and Src to regulate various cellular functions such as cell morphogenesis, cell motility, and cell migration (Gkretsi et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2015b; Zhang et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2009). Apart from cytoplasmic location, migfilin could shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus in cardiac cells and regulate cardiac gene transcriptional activity (Akazawa et al., 2004). In this study, we find that migfilin localizes at autophagic vacuoles to regulate the autophagy process. Functionally, migfilin has been reported as a regulator in hemostasis, thrombosis, and bone remodeling (Xiao et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2019). Recent studies also illustrated that migfilin plays different but important roles in various cancers including leiomyosarcomas (LMS), breast cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, glioma, oral cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Gkretsi and Bogdanos, 2015; He et al., 2014; Ou et al., 2012; Papachristou et al., 2007; Toeda et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2006). However, the function of migfilin in pancreatic cancer is largely unknown.

In this study, we demonstrate a novel function of migfilin in regulating autophagosome accumulation by interacting with SNAP29 and Vamp8. Depletion of migfilin reduced Stx17-SNAP29-Vamp8 SNARE complex formation, which resulted in inhibiting the autophagosome–lysosome fusion, further suppressing cancer cell proliferation. Enhancement of SNARE complex assembly rescued migfilin-deficiency-induced autophagic flux defects and the inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell growth.

Results

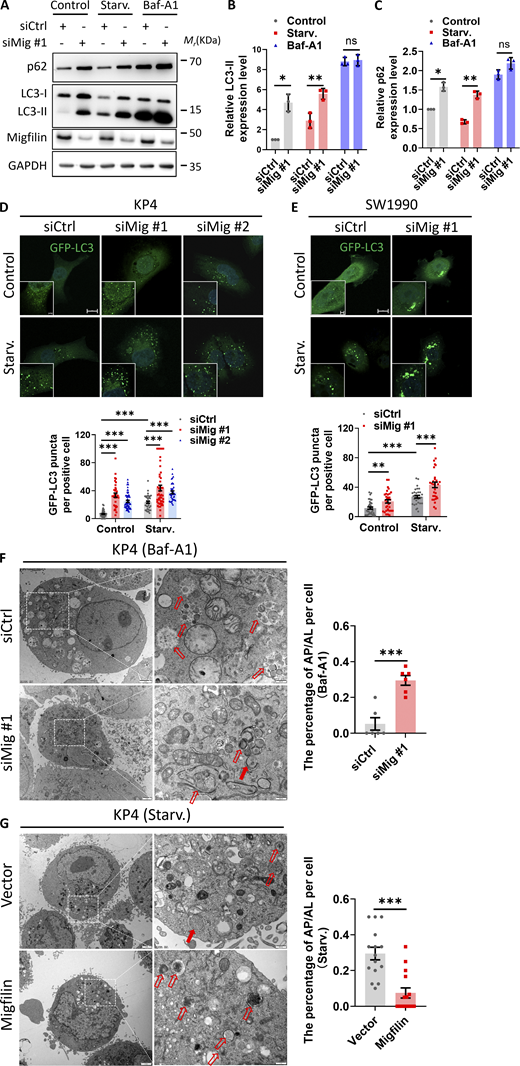

Migfilin depletion promotes autophagosome accumulation

We first investigated the potential effects of migfilin on autophagy in human pancreatic cancer cells by analyzing the expression levels of LC3 and p62 proteins, two well-known markers of autophagic activity (Klionsky et al., 2021a). The unlipidated LC3 (LC3-I) is converted into phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)-conjugated LC3 (LC3-II) during autophagy. To exclude the off-target effects, we knocked down migfilin in KP4 cell, a human pancreatic cancer cell line, using two siRNAs targeting different regions of migfilin mRNA (siMig #1 and siMig #2) (Fig. S1 A). Immunoblotting analysis indicated that depletion of migfilin increased the protein level of LC3-II and p62 under both basal and nutrient-starved conditions, indicating loss of migfilin blocked autophagic process (Fig. 1, A–C and Fig. S1, A–C). To determine which steps of autophagy that migfilin might affect, we treated the cells with a widely used inhibitor of late stages of autophagy, Bafilomycin A1 (Baf-A1). Interestingly, treatment of Baf-A1 did not further increase LC3-II and p62 protein expression in migfilin knockdown cells (Fig. 1, A–C), indicating migfilin probably affects the late step of autophagy. To further test the role of migfilin in autophagy, we stably expressed GFP-LC3 in two pancreatic cancer cells, KP4 and SW1990, to directly monitor autophagosome formation. Consistent with the immunoblotting analyses, the number of GFP-LC3 puncta was increased in the cells lacking migfilin under both basal and starvation conditions (Fig. 1, D and E). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis further verified these observations. More autophagosomes and fewer autolysosomes accumulated in migfilin-deficient cells with Baf-A1 treatment (Fig. 1 F). Likewise, more autolysosomes and fewer autophagosomes were obtained in migfilin-overexpressing cells upon starvation (Fig. 1 G), suggesting that loss of migfilin inhibits the autophagic process and promotes autophagosomes’ accumulation in pancreatic cancer cells. We repeated the effect of migfilin on autophagy by using human breast cancer cells BT549 and obtained similar results (Fig. S2, A–E). Depletion of migfilin in BT549 cells inhibited autophagy activity and promoted autophagosomes’ accumulation (Fig. S2, A–E), suggesting migfilin functions similarly in the regulation of autophagy in different types of cancers.

Migfilin is a focal adhesion protein (Tu et al., 2003), so it is necessary for us to elucidate whether migfilin-deficiency-induced autophagy defects resulted from focal adhesion abnormalities. To clarify this, we disrupted focal adhesion assembly by silencing paxillin, a well-known key regulator of focal adhesions (Laukaitis et al., 2001; López-Colomé et al., 2017), in KP4 cells (Fig. S1 D). Interestingly, aberrant focal adhesion induced by silencing paxillin did not lead to autophagy defects, including alteration of LC3-II, p62 protein levels, and LC3 puncta number (Fig. S1, E and G). These findings were further confirmed by the depletion of vinculin, another important regulator of focal adhesions (Humphries et al., 2007) (Fig. S1, F and G). Thus, these data indicated that migfilin-deficiency-induced autophagic defects are not because of focal adhesion abnormalities.

Migfilin promotes autophagic fusion

To investigate the mechanism through which migfilin regulates the autophagic process, we first obtained a series of z-stack confocal images to examine the cellular distribution of endogenous migfilin and overexpressed mCherry-migfilin (Fig. S3, A–D). Interestingly, we observed that only a small fraction of migfilin was clustered at focal adhesions and partially colocalized with paxillin (focal adhesion marker) as previously reported (Tu et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2006) (Fig. S3, A and C). However, another fraction of migfilin accumulated in punctate and mostly localized in the perinuclear regions under control conditions (Fig. S3, A–D). Interestingly, we found these two fractions of migfilin were disturbed at different layers of cells (Fig. S3, A–D). More importantly, the layer where migfilin localized in the perinuclear regions was hardly detected its focal adhesion distribution. Given the potential role of migfilin in autophagy as evidenced by our aforementioned data, we coexpressed migfilin with some autophagic vesicle markers into KP4 cells to clarify the location of these puncta in the perinuclear regions. As shown in Fig. 2, A–D, migfilin was primarily colocalized with Rab7-labeled late endosomes and lysotracker-stained lysosomes, and partially associated with LC3-labeled autophagosomes, but was distinct from DFCP1-labeled omegasomes under basal and starvation conditions. Moreover, nutrient deprivation led to an increase in the colocalization of migfilin with autophagosomes (Fig. 2 B), which is largely due to the increase in newly formed autophagosome number induced by starvation, but not with late endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 2, C and D). These data suggested that in addition to focal adhesions, migfilin is localized at autophagosome and late-endosome/lysosome regions in pancreatic cancer cells and might participate in the autophagic process, especially the late stages of autophagy.

To test at which step depletion of migfilin causes autophagosome accumulation by inhibiting autophagic flux, we first utilized mRFP–GFP–LC3 reporter system to monitor autophagosome maturation process (Guo et al., 2014). The results showed that depletion of migfilin in both pancreatic cancer cells and breast cancer cells displayed a higher percentage of unfused autophagic structures (white signals) to autolysosome (red signals) under both basal and starvation conditions, indicating an inhibition of autophagic flux (Fig. 3, A–D; and Fig. S2, F and G). To further confirm these observations, we overexpressed Flag-tagged migfilin into KP4 cells (Fig. 4 A) and found that overexpression of migfilin resulted in a lower percentage of autophagosome formation (Fig. 3, A and B), confirming the results that migfilin ablation inhibits autophagic flux.

Autophagic flux inhibition could be caused by the blockage of autophagosome–lysosome fusion or dysfunction of lysosome activity per se (Itakura et al., 2012; Xing et al., 2021). To examine the potential role of migfilin on autophagosome–lysosome fusion, we examine the colocalization of autophagosome and lysosome in wild-type and migfilin knockdown cells by costaining GFP-LC3/lysotracker red (lysosome indicator). As Fig. 4 A shows, the number of GFP-LC3 puncta colocalized with lysotracker red-positive vesicles (acidic lysosome) was significantly reduced in migfilin knockdown cells. Moreover, overexpression of migfilin promotes GFP-LC3 and lysotracker red colocalization (Fig. 4 A). Similar results were obtained by costaining with endogenous LC3 and lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (Lamp1) (Fig. 4 B). In addition, the colocalization of GFP-LC3 puncta and late-endosome labeled by mCherry-Rab7 was largely decreased in migfilin-depleted cells and increased in migfilin-overexpressed cells (Fig. 4 C). Taken together, these results suggest that depletion of migfilin blocks autophagic flux, at least partially, through inhibiting autophagosome–lysosome fusion.

Migfilin depletion is dispensable for lysosome function

In addition to autophagosome–lysosome fusion impairment, dysfunction of the lysosome could lead to autophagic flux inhibition. To further determine whether migfilin deficiency affects lysosome function per se, we compared lysosome number and lysosomal activity in the presence or absence of migfilin. As Fig. 5 A shows, the number of lysosomes indicated by mCherry-Lamp1 did not alter in migfilin knockdown KP4 cells under both basal and starvation conditions. Similarly, the number of lysosomes labeled by lysotracker red had no significant difference between wild-type and migfilin knockdown cells (Fig. 5, B and C). Lysosomal pH evaluated by lysoSensor green staining image analysis or flow cytometry analysis also didn’t exhibit notable changes with or without migfilin in KP4 cells (Fig. 5, D and E). Furthermore, we measured the effects of migfilin on the lysosomal activity by monitoring cathepsin L activity. Cathepsin L is a lysosomal protease whose activity is measured by Magic Red substrate (Zhou et al., 2013). The results revealed that loss of migfilin did not change cathepsin L degradative ability in lysosome (Fig. 5 F). Consistently, lysosomal digestive activity determined by DQ-BSA analysis has also no difference between wild-type and migfilin knockdown cells (Fig. 5, G and H), further strengthening our conclusion that the lysosome function per se is not impaired by depletion of migfilin. Collectively, these results suggest that the blockage of autophagic flux in migfilin knockdown cells is probably due to the impaired autophagosome–lysosome fusion, but not the dysfunction of lysosome.

Migfilin depletion does not affect autophagic initiation

Since aberrant induction of autophagy could also cause autophagosome accumulation, we sought to determine whether migfilin depletion could influence autophagic early stage, including autophagic initiation, nucleation, and bowl-shaped phagophore formation. We utilized Unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1)-GFP (an autophagy initiation marker), DFCP1-GFP (an pre-autophagosomal omegasome marker), ATG14-GFP (a phagophore marker), GFP-ATG16L (a bowl-shaped phagophore marker), and mCherry-Syntaxin 17 (Stx17, an autophagosome marker) to monitor autophagic early stages (Li et al., 2020a; Miao et al., 2021). The results showed that the formation of ULK1-GFP- and DFCP1-GFP-labeled puncta were not significantly altered by migfilin silencing under both basal and starvation conditions (Fig. 6, A and B). However, the number of phagophores indicated by ATG14-GFP and GFP-ATG16L and autophagosomes indicated by mCherry-Stx17 was increased when there was a loss of migfilin (Fig. 6, C–E), indicating that loss of migfilin did not directly affect autophagy initiation step, but instead it probably induced early phagophores accumulation through autophagic fusion blockage. To confirm this hypothesis, we measured the mTORC1 activity in migfilin-depleted cells, as mTORC1 is an upstream regulator of autophagy that interacts with ULK1 complex and phosphorylates ULK1 and ATG13 (Battaglioni et al., 2022). In line with the above data, the knockdown of migfilin did not alter mTORC1 activity as assessed by analysis of the well-described mTORC1 substrates, S6 Kinase (S6K), 4EBP1, and S6K substrate S6 phosphorylation levels (Fig. 6 F). These results indicate that the depletion of migfilin does not affect the initiation steps of autophagy.

Migfilin associates with SNAP29

To explore the molecular mechanism by which migfilin regulates autophagosome–lysosome fusion, we sought to identify migfilin-associated proteins that are involved in the autophagic process by Nanoscale liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (nano LC-MC/MS) approach (Qian et al., 2020). Synaptosomal-associated protein 29 (SNAP29), a component of SNARE complex to promote membrane fusion, was found to be associated with migfilin (Fig. 7 A and Table S1). We then verified SNAP29 and migfilin interaction by sequential immunoprecipitation (IP). As expected, SNAP29 was co-IPed with migfilin in KP4, SW1990, and BT549 cells (Fig. 7 B and Fig. S2 H). Reciprocally, migfilin was also co-IPed with SNAP29 in KP4 and SW1990 cells (Fig. 7 C). Moreover, immunofluorescent staining verified the colocalization of GFP-SNAP29 and mCherry-migfilin (Fig. 7 D). To strengthen these conclusions, we made a live-cell dual-color movie to dynamically monitor mCherry–migfilin and GFP–SNAP29 association. The results showed that mCherry-migfilin puncta were moving with GFP-SNAP29 (Video 1), suggesting migfilin is dynamically associated with SNAP29 in living cells. Additionally, proximity ligation assay (PLA) analysis indicated that the interaction between migfilin and SNAP29 increased upon starvation because high levels of the migfilin–SNAP29 complex (red dots) were detected in KP4 cells under starvation conditions (Fig. 7 E). To further investigate whether SNAP29 directly interacted with migfilin, we performed an in vitro pulldown assay. The results showed that purified MBP-migfilin, but not MBP alone, interacted with GST-tagged SNAP29, suggesting that migfilin directly interacted with SNAP29 (Fig. 7 F). Overall, these results indicate that migfilin associates with SNAP29.

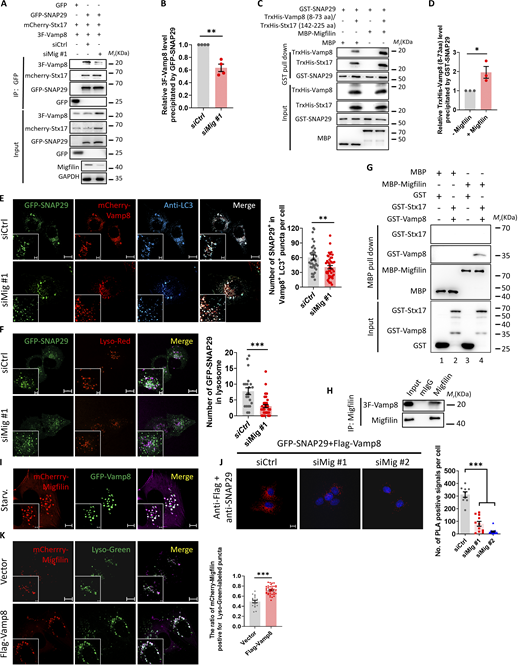

Migfilin facilitates SNAP29–Vamp8 complex formation

Given that migfilin interacts with SNAP29, we hypothesized that migfilin may affect SNAP29-mediated autophagosome-lysosome fusion because SNAP29 is a component of Stx17–SNAP29–Vamp8 SNARE complex, which is involved in autophagosome–lysosome fusion (Zhao et al., 2021). To test this hypothesis, we examined whether migfilin could influence Stx17–SNAP29–Vamp8 SNARE complex formation. KP4 cells were stably expressed 3×Flag-tagged Vamp8, GFP-tagged SNAP29, and mCherry-tagged Stx17. Very interestingly, the results showed that the level of Vamp8, but not Stx17, precipitated by GFP-SNAP29 was significantly reduced in migfilin-depleted cells, emphasizing the important role of migfilin in regulating SNAP29-Vamp8 complex formation (Fig. 8, A and B). To confirm this, we explored the role of migfilin on SNAP29-Vamp8 assembly in vitro by a pull-down assay. Biochemical and structural analysis reported that the Qa-SNARE motif of Stx17 (167–224) can associate with SNAP29 Qb-SNARE (54–117), Qc-SNARE motifs (191–258), and the R-SNARE motif of Vamp8 (8–66) to form the SNARE core complex (Itakura et al., 2012; Li et al., 2020b). Therefore, we utilized Stx17 (142–225) and Vamp8 (8–73) containing SNARE motifs of Stx17 and Vamp8, and full-length SNAP29 to examine the role of migfilin on Stx17–SNAP29–Vamp8 complex formation in vitro. Consistently, we found the formation of the SNAP29-Vamp8 complex was largely enhanced in the presence of migfilin, indicating that migfilin facilitates SNAP29–Vamp8 formation (Fig. 8, C and D). These observations were further verified by immunofluorescence costaining of SNAP29, Vamp8, and LC3 in KP4 cells. Depletion of migfilin decreased the localization of SNAP29 on autolysosomes identified as Vamp8-positive and LC3-postive structures (Fig. 8 E). Additionally, the distribution of SNAP29 on lysosome as indicated by lysotracker red was reduced in migfilin knockdown cells (Fig. 8 F). In addition to Stx17–SNAP29–Vamp8, another SNAP29–mediated SNARE complex Ykt6–SNAP29–Stx7 is also able to facilitate autophagosome–lysosome fusion (Matsui et al., 2018). To test whether migfilin promotes autophagosome–lysosome fusion through Ykt6–SNAP29–Stx7 assembly, we overexpressed 3 × Flag-tagged Ykt6, GFP-tagged SNAP29 and 3 × Flag-tagged Stx7 into KP4 cells. The results showed that the levels of Ykt6 and Stx7, precipitated by GFP-SNAP29 had no significant difference in migfilin-deficient cells compared with that in wild-type cells (Fig. 4, B–D), suggesting migfilin facilitated autophagosome–lysosome fusion only through Stx17–SNAP29–Vamp8 complex, but not through Ykt6–SNAP29–Stx7 complex. Taken together, these results suggest that migfilin enhances SNAP29–Vamp8 association to facilitate SNAP29-mediated SNARE complex assembly, thereby promoting autophagosome fusion with lysosome.

The next important question is how migfilin enhances SNAP29–Vamp8 association. Our speculation is that migfilin interacts with both SNAP29 and Vamp8 to promote their association. To test this, we generated MBP-migfilin and GST-tagged Vamp8 or Stx17 and examined their interactions. Interestingly, the result indicated that GST-Vamp8 (Fig. 8 G, lane 4), but not GST-Stx17 (Fig. 8 G, lane 4) or GST alone (Fig. 8 G, lane 3), directly interacted with MBP–migfilin. Coimmunoprecipitation and colocalization analyses further validated these results (Fig. 8, H and I). Collectively, these data implied that migfilin serves as a scaffold protein to bring SNAP29 and Vamp8 together, thereby driving SNARE complex assembly. To further verify this, we analyzed SNAP29–Vamp8 association in cells with or without migfilin using PLA analysis. Consistent with the coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down results (Fig. 8, A–D), high levels of the SNAP29–Vamp8 complex were detected in wild-type cells (Fig. 8 J). In contrast, a lower amount of PLA puncta was obtained in migfilin knockdown cells (Fig. 8 J). Together, these results support our speculation that migfilin bridges SNAP29 and Vamp8 and consequently promotes Stx17–SNAP29–Vamp8 complex assembly and enhances autophagosome–lysosome fusion.

Since migfilin interacts with Vamp8 (Fig. 8, G–I) and is primarily colocalized with late endosomes/lysosomes (Fig. 2, C and D), we sought to investigate whether migfilin is recruited to late endosomes/lysosomes by Vamp8 to promote autophagosome–lysosome fusion. To do this, we increased the expression of Vamp8 in KP4 cells and examined the co-localization of migfilin with late endosomes/lysosomes. The result showed that a larger number of mCherry-migfilin puncta colocalized with lysotracker-stained lysosomes in Vamp8 overexpressed cells compared with that in control cells (Fig. 8 K), suggesting localization of migfilin on late endosomes/lysosomes depends on Vamp8. Thus, our above findings strongly suggest that migfilin is recruited to late endosomes/lysosomes by Vamp8 and then promotes SNAP29–Vamp8–mediated SNARE complex assembly and autophagosome–lysosome fusion.

Upregulation of SNARE complex formation rescues migfilin-deficiency induced autophagic flux defects

To confirm that migfilin deficiency–induced autophagic flux defects are due to SNAP29-mediated SNARE complex disruption, we attempted to enhance SNARE complex in migfilin knockdown KP4 cells. As previously reported, SNAP29 could be posttranslationally modified by O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase (OGT) (Guo et al., 2014). Knockdown of OGT reduces the O-GlcNAcylation of SNAP29, which increases SNAP29-mediated SNARE complex formation (Guo et al., 2014) (Fig. S4 E). Consistent with these previous studies, migfilin deficiency disrupted SNAP29–Vamp8 assembly and OGT silencing successfully restored SNAP29–Vamp8 association in migfilin knockdown cells (Fig. 9, A and B). Subsequently, OGT silencing effectively reversed the inhibition of autophagy caused by loss of migfilin, including upregulation of LC3-II and p62 protein levels, and accumulation of GFP-LC3 puncta in migfilin knockdown cells (Fig. 9, C–F). In line with this, the blockage of autophagosome–lysosome fusion in migfilin knockdown cells was also relieved by OGT silencing (Fig. 9, G and H), implying that upregulation of SNARE complex formation could rescue autophagy inhibition. To confirm these conclusions, we utilized another way to enhance SNARE complex formation, which is overexpression of a O-GlcNAcylation-defective SNAP29 mutant (quadruple mutations at S2A, S61G, T130A, S153G, named SNAP29-QM hereafter) (Guo et al., 2014). Similar to what we observed by using OGT siRNA, overexpression of SNAP29-QM successfully enhanced SNARE complex formation (Fig. 9 I). Moreover, overexpression of SNAP29-QM, like that of full-length migfilin, reversed migfilin-deficiency-induced high LC3-II and p62 protein level and autophagosome accumulation, compared with overexpression of wild-type SNAP29 (Fig. 9, J–M). Given overexpression of SNAP29-QM bypassed migfilin deficiency–induced autophagic defects, we attempted to test whether depletion of migfilin could increase O-GlcNAcylation of SNAP29, thereby blocking SNARE complex formation. We performed SNAP29 immunoprecipitation assay to examine SNAP29 O-GlcNAcylation in wild-type and migfilin knockdown cells. The results indicated that loss of migfilin did not significantly increase SNAP29 O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. S4 F), suggesting migfilin deficiency–induced autophagic defects are not through regulating SNAP29 O-GlcNAc-modification. Taken together, our data indicated that migfilin deficiency–induced autophagic defects are mediated through, at least in part, control of SNAP29-mediated SNARE complex formation.

Migfilin depletion promotes focal adhesion accumulation through its function on autophagy

Our aforementioned data revealed that migfilin has two different cellular distributions, focal adhesions and autophagic organelles (Figs. 2 and S3). Therefore, we asked whether migfilin affects not only autophagy process but also focal adhesion assembly. Very interestingly, the results showed that depletion of migfilin, unlike that of paxillin or vinculin (key regulators of focal adhesions) (Humphries et al., 2007; Laukaitis et al., 2001), failed to disrupt focal adhesions (Fig. S5, A–C). Instead, the knockdown of migfilin increased the size and the number of paxillin-indicated focal adhesions (Fig. S5, A–C). Reinhard Fässler et al. previously reported that the knockdown of migfilin in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) did not change the size and the number of focal adhesions (Moik et al., 2011), indicating migfilin is not required for focal adhesion assembly. Then, why depletion of migfilin increase focal adhesion accumulation in this current study? Previous studies reported that autophagy serves as a major mechanism to degrade focal adhesions (Kenific et al., 2016; Sharifi et al., 2016). Because migfilin depletion strongly impaired autophagic process, we speculated that migfilin deficiency–induced focal adhesion accumulation results from its function on autophagy and depends on SNAP29-mediated autophagosome–lysosome fusion. To test this, we silenced OGT in Mifflin-deficient cells, which has been shown to increase SNARE complex formation and promote autophagy activity (Fig. 9, A–H). As expected, OGT silencing successfully reduced the number and the size of focal adhesions in migfilin knockdown cells (Fig. S5, A–C). Thus, these results indicate that depletion of migfilin inhibits autophagic activity, which results in the accumulation of focal adhesions.

Migfilin promotes pancreatic cancer cell survival

The last question we attempt to address in this study is the clinical relevance of migfilin and its mediated autophagy in pancreatic cancer. To test this, we first analyzed migfilin (also called FBLIM1) expression in human pancreatic cancer by using the GEPIA web server (Tang et al., 2017). The analysis showed that migfilin level was significantly upregulated in pancreatic cancer tissues (Tumor) compared with normal pancreatic tissues (Normal) (Fig. 10 A). In addition, PDAC patients with high expression levels of migfilin were associated with poor disease-free survival, indicating migfilin level is related to the pathology of pancreatic cancer (Fig. 10 B). To further confirm the role of migfilin in pancreatic cancer, we reduced migfilin levels in KP4 cells. As expected, migfilin depletion dramatically decreased the pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and colony formation activities (Fig. 10, C and D). We repeated this cell proliferation assay in breast cancer cell BT549 and obtained similar results (Fig. S2 I). More importantly, to determine whether migfilin promotes pancreatic cell proliferation through regulation of SNARE complex formation, we ectopically expressed SNAP29-QM in migfilin knockdown cells to enhance SNARE complex assembly (Fig. 9 I). Interestingly, overexpression of SNAP29-QM, like that of full-length migfilin, significantly reversed cell proliferation inhibition caused by loss of migfilin compared with overexpression of wild-type SNAP29 (Fig. 10, E and F). Taken together, these data demonstrate that migfilin plays crucial roles in pancreatic cancer progression, and it exerts this effect through, at least in part, regulating SNAP29-mediated SNARE complex formation.

Discussion

Migfilin is previously reported as an adaptor protein to regulate integrin-mediated cell-ECM signaling (Tu et al., 2003; Wu, 2005; Zhao et al., 2009). In this study, we have shown a novel function of migfilin in autophagy regulation. Our data indicate that in addition to focal adhesions, a fraction of migfilin localized at autophagosome and late endosomes/lysosomes, and interacted with SNAP29 and Vamp8. Migfilin promoted SNAP29–Vamp8 association and SNARE complex formation, which facilitated autophagosome–lysosome fusion and promoted autophagic clearance.

SNARE complex is identified as a core, together with other tether proteins, including HOPS, PLEKHM1, TECPR1, ATG14, EGP5, and WDR45/WDR45B to facilitate autophagosome–lysosome fusion (Chen et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015a; McEwan et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Two sets of SNARE complex have been identified, Stx17–SNAP29–Vamp8 and Ykt6–SNAP29–Stx7 (Ji et al., 2021; Matsui et al., 2018; Takáts et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2021). Among these complexes, SNAP29 functions as the core component to promote autophagosome–lysosome fusion. Yet, tether proteins were reported to bind with autophagosomal or lysosomal proteins, but how cytosol SNAP29 participates in autophagic fusion was largely unknown. In this study, we found that migfilin associates with SNAP29 and Vamp8, thereby facilitating SNAP29–Vamp8 assembly to promote autophagic fusion and flux. Although our studies have revealed a novel role of migfilin in the regulation of SNARE complex formation, how migfilin helps SNARE assembly needs to be further investigated in future studies. Potentially, migfilin speeds up SNAP29–Vamp8 association by facilitating SNARE complex to travel along the cytoskeleton because migfilin could bind to the actin cytoskeleton through filamin protein (Stossel and Hartwig, 2003; Tu et al., 2003). Alternatively, migfilin may recruit other tethering proteins to the SNARE complex to aid SNARE complex assembly and fusion.

Although our results indicate that migfilin promotes pancreatic cancer progression by regulating SNARE complex formation, our studies do not rule out the possibility that other migfilin-mediated signaling pathways also contribute to pancreatic cancer progression. For example, migfilin is known as an adaptor protein that participates in Src–Kindlin2–Migfilin–Src positive feedback loop to regulate Src activation, which also potentially participates in cancer cell growth (Liu et al., 2015b). Indeed, while SNAP29-QM overexpression enhanced SNARE complex formation and rescued the migfilin deficiency–induced inhibition of pancreatic cell proliferation, it still retained some inhibition on cell proliferating abilities compared with wild-type cells, suggesting migfilin promoted pancreatic cancer cell growth by regulating not only SNARE complex but also other factors.

Accumulating evidence indicate that autophagy provides nutrients and metabolic adaption to cancer cells, therefore facilitating cancer progression. In pancreatic cancer, the basal autophagic level was increased and inhibition of elevated autophagy in pancreatic cancer suppresses cell proliferation and cancer progression (Yang et al., 2011, 2014). In this study, we found that depletion of migfilin inhibits pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, and the reassembly of the SNARE complex could increase pancreatic cancer cell growth. These results indicate that migfilin may promote pancreatic cancer cell survival through, at least in part, the regulation of the SNARE complex. Given the important role of migfilin–SNARE axis in pancreatic cancer growth, targeting this signaling axis may provide a promising interventional approach to alleviate pancreatic cancer progression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human pancreatic cancer cell lines KP4 (JCRB0182), SW1990 (CRL-2172), and human breast cancer cell line BT549 (HTB-122) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) or Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (JCRB). KP4, SW1990, and BT549 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM)/Hams F-12 50/50 Mix (10-092-CV; Corning), DMEM (10099-141; Invitrogen), or RPMI 1640 medium (8121720; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco-Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin (15140-122; Gibco) at 37°C in 5% CO2, respectively. Cells were authenticated through the short tandem repeat analysis method and mycoplasma contamination was excluded.

Reagents

Lentivirus package plasmids psPAX2 (#12260) and pMD2.G (#12259) were obtained from Addgene. Full-length migfilin cDNA was cloned from HEK 239T cells. Full-length DFCP1, ATG14, ATG16L, Rab7, Stx17, Vamp8, Ykt6, Stx7, and LC3 cDNAs were kindly provided by Dr. Yan Zhao (Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China) (Ji et al., 2021). Full-length SNAP29, Stx17 (142–225 aa), and Vamp8 (8–73 aa) cDNAs were kindly provided by Dr. Zhiyi Wei (Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China). Full-length ULK1 and Lamp1 cDNAs were obtained from Youbio (G166434 and F114931). Autophagy inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (Baf-A1) was purchased from Selleck (S1413).

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in 1× SDS lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 100 mM dithiothreitol [D806827; DTT], 10% glycerol [A600232-0500; BBI], and 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [Bio Froxx, 3250GR500; SDS] containing protease inhibitor cocktail [20124ES03; Yeasen], phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride [PMSF, P7626; Sigma-Aldrich], and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail [GRF102; Epizyme]). Protein concentrations were measured using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (23227; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunoblotting analysis was performed as described previously (Sun et al., 2017). In brief, equal amount (10–40 μg per lane) of cell proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a 0.2-µm nitrocellulose membrane (66485; PALL) or a 0.2-µm polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (PVDF; Millipore). Membranes were blocked in 1 × TBST buffer containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0332; VWR) for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and subsequently incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-HRP-conjugated GAPDH (AC035, 1:10,000; ABclonal), rabbit anti-p62 (PM045, 1:1,000; MBL), rabbit anti-LC3 (ab192890, 1:2,000; Abcam), mouse anti-migfilin (clone 43.9, 1:1,000), rabbit anti-migfilin (1:1,000, HPA025287; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-Stx17 (1:1,000, PM076; MBL), rabbit anti-SNAP29 (1:1,000, 12704-1-AP; Proteintech), rabbit anti-Vamp8 (1:10,000, ab76021; Abcam, and 1:1,000, 15546-1-AP; Proteintech), rabbit anti-Paxillin (1:1,000, GTX125891; GeneTex), rabbit anti-vinculin (1:10,000, ab129002; abcam), mouse anti-Kindlin-2 (1:5,000, MAB2617; Millipore), rabbit anti-S6 kinase (1:1,000, #2708; CST), rabbit anti-phospho-S6 kinase (Thr389) (#9234, 1:1,000; CST), rabbit anti-S6 (1:1,000, #2217; CST), rabbit anti-phospho-S6 (Ser235/236) (1:1,000, #2211; CST), rabbit anti-4EBP1 (A19045; ABclonal), rabbit anti-phospho-4EBP1-T37/46 (AP0030; ABclonal), rabbit anti-OGT (1:1,000, #24083; CST), mouse anti-Flag (1:1,000, F1804; Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-GFP (1:50,000, 66002-1-Ig; Proteintech), mouse anti-mCherry (1:2,000, ABT2080; Abbkine), mouse anti-His (1:1,000, AB102-02; TIANGEN), mouse Anti-O-Linked N-Acetylglucosamine (RL2, 1:1,000, ab2739; Abcam), mouse anti-HRP-conjugated MBP (AE075; ABclonal), mouse anti-HRP-conjugated GST (AE027; ABclonal). The membrane was washed and incubated by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit or mouse IgG antibodies (1:10,000, #31460 or #31430; Invitrogen). Bolts were developed by using Omni-ECL Pico Light Chemiluminescence Kit (SQ202L; Epizyme), and images were captured by an imaging scanning system (5200; Tanon). Band intensity quantification was performed with Fiji.

RNAi

Cell transfection was delivered by Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (#13778-150; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Double siRNAs were purchased from Gene Pharma. The sequences were as follows:

Control siRNA: sense, 5′-ACGCAUGCAUGCUUGCUUUTT-3′; antisense, 5′-AAAGCAAGCAUGCAUGCGUTT-3′; Migfilin siRNA #1: sense, 5′-GGAAGUGAGGCAGGCAGUUTT-3′; antisense, 5′-AACUGCCUGCCUCACUUCCTT-3′; Migfilin siRNA #2: sense, 5′-CCACAGACAUCUGUGCCUUTT-3′; antisense, 5′-AAGGCACAGAUGUCUGUGGTT-3′; OGT siRNA: sense, 5′-GAUUAAGCCUGUUGAAGUCTT-3′; antisense, 5′-GACUUCAACAGGCUUAAUCTT-3′; PXN siRNA #1: sense, 5′-CCCUGACGAAAGAGAAGCCUA-3′; anti-sense, 5′-UAGGCUUCUCUUUCGUCAGGG-3′; PXN siRNA #2: sense, 5′-GUGUGGAGCCUUCUUUGGUTT-3′; anti-sense, 5′-ACCAAAGAAGGCUCCACACTT-3′; Vin siRNA #1: sense, 5′-GGAAGAAAUCACAGAAUCATT-3′; anti-sense, 5′-UGAUUCUGUGAUUUCUUCCTT-3′; Vin siRNA #2: sense, 5′-CCAGAUGAGUAAAGGAGUATT-3′; anti-sense, 5′-UACUCCUUUACUCAUCUGGTT-3′.

Lentivirus production, purification, and infection

cDNAs were cloned into pLVX-Flag-Hyg (modified from pLVX-IRES-Hyg, #632185; Clontech), pLVX-mCherryC1(#632561; Clontech), or pLVX-GFP-Hyg (modified from pLVX-IRES-Hyg, #632185; Clontech) lentivirus vector. 7.5 µg lentivirus constructs were cotransfected with viral packaging plasmids psPAX2 (5.2 µg) and pMD2.G (2.8 µg) into HEK 293T cells by lipofectamine 3000 reagents (L3000-015; Invitrogen). 48 h later, the medium containing the virus was harvested and filtered through a 0.45-µm filter, and then the supernatant was centrifuged by Ultracentrifuge (Optima-XPN-100; Beckman) with 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. Cells were seeded in a six-well plate and infected by purified lentivirus with 10 μg/ml polybrene. The viral infection efficiency was confirmed by immunoblotting.

Transmission electron microscopy

KP4 cells were treated as indicated. Cells were fixed with 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde with phosphate buffer (PB) (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and washed four times in PB at 4°C. Then cells were post-fixed with 1% (wt/vol) OsO4 and 1.5% (wt/vol) potassium ferricyanide aqueous solution at 4°C for 2 h and dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (30, 50, 70, 80, 90, 100% × 2, 6 min) into pure acetone (2 × 6 min). Samples were infiltrated in a graded mixture (3:1, 1:1, 1:3) of acetone and SPI-PON812 resin (21 ml SPI-PON812, 13 ml DDSA, and 11 ml NMA) and then changed to pure resin. Finally, cells were embedded in pure resin with 1.5% BDMA and polymerized for 12 h at 45°C, 48 h at 60°C. The ultrathin sections (70 nm thick) were sectioned with a microtome (Leica EM UC6), double-stained by uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined by a transmission electron microscope (FEI Tecnai Spirit120kV).

Immunoprecipitation

KP4, SW1990, and BT549 cells were harvested in 1× lysis buffer (P0013; Beyotime) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitors for 30 min at 4°C. After that, cell lysates were sonicated followed by centrifuging with 14,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C and then the supernatant was collected. An equal amount of cell lysates (3–5 mg) was incubated with mouse anti-migfilin (clone 3.10) or rabbit anti-SNAP29 antibody (12704-1-AP; Proteintech) overnight at 4°C, and an irrelevant mouse IgG (sc-2025; Santa Cruz) or rabbit IgG (#2729; CST) was incubated as a negative control. The lysate was incubated with Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose beads (sc-2003; Santa Cruz) or Anti-GFP Nanobody Agarose Beads (KTSM1301) for 2 h at 4°C. Antibodies and associated proteins were immunoprecipitated and washed with 1× lysis buffer for three times. The prepared samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE for western blotting.

Fusion protein expression, purification, and pull-down assay

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged, maltose binding protein (MBP)-tagged, or His-tagged fusion protein expression, purification, and pull-down assay were performed as described previously (Qian et al., 2020). In brief, cDNAs encoding full-length SNAP29, Stx17, Vamp8, or migfilin were cloned into pGEX-4T-1 or pET32-MBP-His-3C vector, respectively. Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) was transformed with various plasmids. GST and GST-fusion proteins were purified with Glutathione-Sepharose 4B matrix (Cat# 17-0756-01; GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Maltose binding protein (MBP)-fusion proteins were purified by an amylose resin kit (Cat# E8021S; New England Biolabs). In pull down assays, 20–40 μg MBP alone or MBP-fusion protein bound to amylose resin were incubated with recombinant GST alone or GST-fusion protein in 500 μl pull-down buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, and 0.1% Triton X-100) at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, protein-bound beads were washed five times with pull-down buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting.

In vitro binding assay

For in vitro binding assay, full-length cDNA of migfilin or SNAP29 was cloned into pET32-MBP-His-3C or pGEX-4T-1 vectors, respectively. cDNA encoding Stx17 (142–225 aa) or Vamp8 (8–73 aa) was cloned into pET32-TrxHis-3C vector. 20–40 μg MBP alone or MBP-tagged migfilin was incubated with GST-tagged SNAP29, His-tagged Stx17 (142–225 aa), and Vamp8 (8–73 aa) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, 20 μl Glutathione-Sepharose 4B matrix was incubated with assembled proteins for 2 h at 4°C. Finally, GST beads were washed and eluted for immunoblotting analysis.

Lysosomal activity measurement

Lysosome activity was analyzed by Magic Red Cathepsin L kit (#941; immunochemistry) and DQ-BSA green (D-12050; Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, indicated cells were seeded in a glass-bottom dish (801002; NEST) and incubated with 1:25 (vol/vol) diluted Magic Red at 37°C for 30 min to prevent from light or 10 μg/ml DQ-BSA green at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were washed with 1 × PBS twice and cultured with the indicated medium. Live-cell images of Magic Red staining and DQ-BSA green staining were visualized immediately at 37°C with confocal microscopy using a 63× oil immersion objective (Zeiss LSM 980). For flow cytometer analysis, indicated cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml DQ-BSA green at 37°C for 1 h. 10,000 cells were counted for analysis by FlowJo (Version 10).

Lysotracker/lysosensor probing

Cells were seeded on the glass-bottom dishes (801002; NEST) and incubated with 50 nM lysotracker red (C1046; Beyotime), 50 nM lysotracker green (C1047; Beyotime), or 1 μM lysosensor Green DND-189 (40767ES50; Yeasen) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed with 1× PBS twice and cultured with indicated media. Live-cell images were captured immediately at 37°C with confocal microscopy using a 63× oil immersion objective (Zeiss LSM 980). For flow cytometer analysis, indicated cells were incubated with 50 nM lysotracker red or 1 μM lysosensor Green DND-189 at 37°C for 30 min. 10,000 cells were counted for analysis by FlowJo (Version 10).

Nano LC-MS/MS analysis

KP4 cell lysates (∼3 mg/ml) were immunoprecipitated (IPed) with mouse anti-migfilin antibody (clone, 3.10) or control mouse IgG (sc-2025; Santa Cruz) by agarose beads (sc-2003; Santa Cruz). Each IP sample was then analyzed by nano LC-MS/MS as described previously (Guo et al., 2019). In brief, beads were washed with fresh 1 ml 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) three times and digested with 10 μl 0.25 mg/ml sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega) at 37°C overnight. The resulting peptides were resuspended and collected by 1% (vol/vol) formic acid (FA). Sequentially, the peptides were dried in a speed vacuum and re-dissolved in 200 μl 1% FA and desalted by homemade C18-StageTip (Chen et al., 2016), which was washed with 60 μl methanol, 60 μl solution A (80% [vol/vol] acetonitrile [ACN] plus 0.5% [vol/vol] acetic acid [AcOH]), and 60 μl 1% FA twice. Peptides were washed with 1% FA twice and eluted with solution A. Finally, eluted peptide mixtures were lyophilized to dryness and redissolved in 16 μl 0.1% (vol/vol) FA for nano LC-MS/MS analysis. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (Perez-Riverol et al., 2022) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD051656.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells (as specified in each experiment) were washed with 1× PBS and fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by permeability by 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were then blocked in 5% BSA for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-LC3 (ab192890, 1:962; Abcam), mouse anti-Lamp1 (555798, 1:500; BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-Rab7 (1:1,000, #9367; CST), mouse anti-migfilin (clone 43.9, 1:2,000), mouse anti-Kindlin-2 (1:5,000, MAB2617; Millipore), or rabbit anti-paxillin (1:500, GTX125891; GeneTex) at 4°C overnight. Cells were then washed with 5% BSA three times and incubated with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies: Goat-anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (A11008; Invitrogen), Goat-anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 594 (A11005; Invitrogen), or Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG DyLight 350 (A23020; Abbkine). Cells were costained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, P36941; Invitrogen). The images were scanned by Zeiss 980 using a 63× oil immersion objective. Data analysis was performed by ZEN 3.5 (blue edition) and Imaris (version 8.3). For puncta quantification, the captured images were processed using ZEN software, and the background intensity was determined and established as the threshold. Signals surpassing this threshold were manually counted as positive puncta. For colocalization analysis, raw images were imported into Imaris software followed by “spot” module operations. To further calculate the extent of colocalization, colocalization plugin was utilized to derive colocalization ratios.

Dual-color move imaging

KP4 cells were coinfected with lentivirus encoding mCherry-Migfilin and GFP-SNAP29. The cells were seeded on a glass-bottom dish (D35-20-1-N; Cellvis) and starved for 1 h at 37°C. Live-cell images were captured by Multi-SIM (Nanoinsights) and data were processed with Fiji.

In situ PLA

PLA assay was performed using Duolink PLA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Rabbit anti-SNAP29 (1:1,000, 12704-1-AP; Proteintech) and mouse anti-migfilin (clone 43.9, 1:2,000) or mouse anti-Flag (1:1,000, F1804; Sigma-Aldrich) primary antibodies were used to detect the interaction between endogenous SNAP29 and migfilin proteins or exogenous GFP-SNAP29 and 3 × Flag-Vamp8 proteins. PLA signals (red dots) were captured by Zeiss 980 and analyzed by ZEN 3.5 (blue edition).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Cells were seeded as 2 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates and cultured in growth media. After the indicated time points, the cells were stained with 10 µl 5 mg/ml sterile MTT reagent (M5655; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 4 h. After incubation, 100 µl DMSO (P6258; Macklin) was added to dissolve formazan crystals. The number of viable cells was measured by the microplate reader (Epoch2; BioTek) at 490 nm absorption. All experiments were performed at least in triplicate.

Colony-formation assay

1 × 103 cells were seeded into six-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 10–14 days. Then, cells were fixed by 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature and stained by 1× Giemsa staining reagent (C0131; Beyotime) for 30–45 min. The number of colonies containing >50 cells was counted. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Focal adhesion measurement

The quantification of focal adhesion (FA) number and size were measured as described (Horzum et al., 2014). In brief, raw images were sequentially processed with subtract background, contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE), and mathematical exponential (Exp). Images were further processed by Brightness & Contrast adjustment and threshold commands to outline positive signals.

Statistical analyses

All data represent as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare two groups of samples. One-way ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Prism 8 (GraphPad) was used for statistical analysis.

Online supplemental material

Fig.S1 shows that disruption of focal adhesions does not lead to autophagy defects. Fig. S2 demonstrates that migfilin depletion blocks autophagic flux and inhibits cell growth in human breast cancer cells. Fig. S3 shows that migfilin localizes at both focal adhesions and late endosomes/lysosomes. Fig. S4 shows that migfilin does not regulate Stx7–SNAP29–Ykt6 complex assembly and SNAP29 O-GlcNAcylation. Fig.S5 shows that the depletion of migfilin increases focal adhesion accumulation. Table S1 provides a list of migfilin-associated proteins identified in KP4 cells by mass spectrometry. Video 1 shows that migfilin dynamically associates with SNAP29 in living KP4 cells.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD051656. Apart from this, all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary files. Requests for materials should be addressed to Y. Sun.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Southern University of Science and Technology Core Facility for technical assistance for the use of the confocal microscopy and histology/pathology equipment. We also are grateful to Xueke Tan and Xixia Li for helping with electron microscopy sample preparation and taking TEM images at the Center for Biological Imaging (CBI), Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Science.

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (8237100185, 82070728); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2024A1515013048, 2023B0303040004, 2021B1515120063 and 2017B030301018); and the Shenzhen Innovation Committee of Science and Technology, China (JCYJ20200109141212325).

Author contributions: R. Cai: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, P. Bai: Formal analysis, Investigation, M. Quan: Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Y. Ding: Investigation, Resources, W. Wei: Investigation, C. Liu: Investigation, A. Yang: Investigation, Validation, Writing—review & editing, Z. Xiong: Investigation, G. Li: Formal analysis, Investigation, B. Li: Formal analysis, Investigation, Y. Deng: Funding acquisition, R. Tian: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Y.G. Zhao: Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, C. Wu: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Y. Sun: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

References

Author notes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests exist.