Dantrolene is a neutral hydantoin that is clinically used as a skeletal muscle relaxant to prevent overactivation of the skeletal muscle calcium release channel (RyR1) in response to volatile anesthetics. Dantrolene has aroused considerable recent interest as a lead compound for stabilizing calcium release due to overactive cardiac calcium release channels (RyR2) in heart failure. Previously, we found that dantrolene produces up to a 45% inhibition RyR2 with an IC50 of 160 nM, and that this inhibition requires the physiological association between RyR2 and CaM. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that dantrolene inhibition of RyR2 in the presence of CaM is modulated by RyR2 phosphorylation at S2808 and S2814. Phosphorylation was altered by incubations with either exogenous phosphatase (PP1) or kinases; PKA to phosphorylate S2808 or endogenous CaMKII to phosphorylate S2814. We found that PKA caused selective dissociation of FKBP12.6 from the RyR2 complex and a loss of dantrolene inhibition. Rapamycin-induced FKBP12.6 dissociation from RyR2 also resulted in the loss of dantrolene inhibition. Subsequent incubations of RyR2 with exogenous FKBP12.6 reinstated dantrolene inhibition. These findings indicate that the inhibitory action of dantrolene on RyR2 depends on RyR2 association with FKBP12.6 in addition to CaM as previously found.

Introduction

Cardiac contraction, relaxation, and rhythm depend on Ca2+ fluxes between intracellular and extracellular compartments of myocytes. (Bers, 2006; Eisner et al, 2017). Myocyte contraction (systole) is initiated by depolarization of the sarcolemma during the action potential that triggers L-type Ca2+ channels. The resulting Ca2+ influx activates Ca2+-sensitive RyR2, which release Ca2+ from the internal Ca2+ store (sarcoplasmic reticulum; SR) by a process dubbed Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR; Fabiato 1983). The combination of Ca2+ influx and SR release increases the bulk cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) from 0.1 to 1 μM (Shannon et al., 2003), which initiates crossbridge cycling and muscle contraction. Upon membrane repolarization, CICR ceases, RyR2 close, and SR Ca2+ release terminates. Excess cytoplasmic Ca2+ is removed via the Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) in the sarcolemma and myocytes relax (diastole).

RyR2 channels are homotetramers (∼5,035 amino acids per subunit) which together with other regulatory proteins including FK506 binding proteins (FKBP12 and 12.6), calmodulin (CaM), as well as kinases (PKA and CaMKII) and phosphatases (PP1, PP2A) comprise a macromolecular complex (Marks, 2001). CaM (Balshaw et al., 2001) and possibly FKBP12.6 partially inhibit RyR2 activity, although the literature is divided on the latter (see review by Gonano and Jones, 2017). RyR2 phosphorylation by PKA and CaMKII modulates intermolecular interactions within the macromolecular complex. Serine residues at positions 2030, 2808, and 2814 (numbering for human RyR2) have been identified as regulatory sites where phosphorylation increases RyR2 activity during adrenergic stimulation. RyR2 serine 2808 can be phosphorylated by PKA (Marx et al., 2000) and 2814 by CaMKII (Wehrens et al., 2004). Though RyR2 serine 2030 is reported to be phosphorylated by PKA (Potenza et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2005), this is contested by Wehrens et al. (2006), who found that preventing S2808 phosphorylation in the S2808A RyR2 mutant completely prevented the incorporation of 32P into RyR2 by PKA phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation of S2808 results in a 50% reduction in CaM binding to RyR2 (Fukuda et al., 2014), and phosphorylation of either S2808 or S2814 is required for CaM to partially inhibit RyR2 activity (Walweel et al., 2019). Pathological overactivation of RyR2 is associated with the life-threatening arrhythmias associated with heart failure and inherited disorders such as catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT; Hwang et al., 2014; Nyegaard et al., 2012). Excess SR Ca2+ release through “leaky” RyR2 during diastole can lead to both an increased diastolic [Ca2+]c and reduced SR Ca2+ load. Increased diastolic [Ca2+]c causes excessive sarcoplasmic depolarization via NCX activity, increased excitability, and cardiac arrhythmias (George et al., 2007; George et al., 2006), whereas reduced SR Ca2+ load leads to a reduced systolic Ca2+ release and muscle contraction as seen in heart failure (Yano et al., 2005). Hence, stabilization of the RyR2 closed state during diastole, resulting in suppression of abnormal SR Ca2+ leak, is a promising therapeutic strategy against heart failure and lethal arrhythmias (Lehnart et al., 2006).

Dantrolene is a skeletal muscle relaxant that is prescribed for the acute treatment of malignant hyperthermia (MH; Muehlschlegel and Sims, 2009). In a failing heart, dantrolene selectively reduces diastolic Ca2+ leak, without inhibiting Ca2+ release during systole and without otherwise affecting the function of normal healthy hearts (Chou et al., 2014; Maxwell et al., 2012). Dantrolene is believed to inhibit pathological overactivation of RyR2 by stabilizing interdomain interactions between its N-terminal and central regions (Chi et al., 2019; Kobayashi et al., 2005; Kobayashi et al., 2010). We recently showed that dantrolene is a direct inhibitor of sheep RyR2 and requires the presence of CaM for its inhibitory action (Oo et al., 2015). Here, we investigate how RyR2 phosphorylation affects dantrolene inhibition (in the presence of CaM) and found that PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 caused partial dissociation of FKBP12.6 from the RyR2 complex, which led to a loss of dantrolene inhibition.

Materials and methods

Heart tissue and preparation of SR vesicles

Sheep tissues were obtained with approval from the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of the University of Newcastle (approval number #A-2009-153). Sheep hearts were obtained from ewes anesthetized with 5% pentobarbitone followed by oxygen/halothane. SR vesicles containing RyR2 were isolated from sheep hearts (Laver et al., 1995). Heart muscle was minced and homogenized in a buffer containing 0.3 M sucrose, 10 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 1 µg/ml leupeptin, 1 µg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mM benzamidine, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 3 mM NaN3, and 20 mM NaF, pH 6.9, and stored in the homogenizing buffer supplemented with 0.65 M KCl. SR vesicles were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

In vitro phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of RyR2 channels

In vitro dephosphorylation was achieved by incubation of SR vesicles (15 min at 30°C), prior to single channel recordings, in a PP1 reaction kit containing MnCl2, NEBuffer, and 2.5 unit/μl PP1 (New England BioLabs). Rephosphorylation of RyR2 at S2808 by PKA enzyme was performed by incubating SR vesicles (5 min at 30°C) with exogenous PKA in a buffer containing (in mM) 50 Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 MgCl2, 2 ATP, 1 cAMP, 10 NaF, 0.25 g/ml PKA (Sigma-Aldrich), and the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 (10 μM) to prevent rephosphorylation at S2814. Rephosphorylation of RyR2 at S2814 by CaMKII enzyme was achieved by incubation of SR vesicles (5 min at 30°C) in a CaMKII activating buffer containing (in mM) 50 Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 MgCl2, 2 ATP, 25 NaF, 2.5 CaCl2, 62.5 μM CaM, and the PKA inhibitor H89 (2 μM) to prevent rephosphorylation at S2808. The CaMKII activation buffer contained no exogenous CaMKII because endogenous CaMKII is known to be associated with and phosphorylate the RyR2 in vitro. (Bers, 2004; Currie et al., 2004; Witcher et al., 1991) In vitro dephosphorylated and rephosphorylated RyR2 were used in single-channel recording, SDS PAGE, and Western blot experiments.

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Interactions between RyR2 and FKBPs were detected via co-IP. After in vitro phosphorylation, dephosphorylation treatment (above) or incubation with 20 μM rapamycin for 1 h at room temperature, co-IP of the RyR2 complex (or the FKBP–protein complexes) was achieved using a Pierce co-IP kit and anti-RyR2 PAB17291 or anti-FKBP H5 antibodies, following the manufacturer’s instructions (the anti-FKBP H5 antibody recognizes both FKBP isoforms). Prior to commencing each co-IP assay, the SR vesicles were solubilized in a solution containing 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid, pH 7.4 (MOPS buffer); and 1 mM Ca2+, 5% glycerol, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in MOPS buffer (MOPS/Ca2+ buffer).

SDS PAGE and Western blot

Proteins were separated using SDS PAGE (Laemmli, 1970; Towbin et al., 1992) using BOLT 4–12% Bis-Tris Plus precast polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using Western blot. Membranes were immunoprobed with primary antibodies to measure RyR2 phosphorylation at S2808 and S2814 (using antibodies specific for the RyR2 S2808 residue only when it is phosphorylated) and then secondary HRP-conjugated antibody, prior to chemiluminescence detection. Images were obtained using the Odyssey FC imaging system and quantified using the associated image studio software. Membranes were then incubated at 50°C for 30 min in PBS with 2% SDS and 0.7% β-mercaptoethanol (v/v) to “strip” the primary and secondary antibodies, followed by washing at least 10 times for 5 min each in PBS to completely remove the incubation solution. The membranes were then immunoprobed with an anti-RyR PAB17291 (to detect total RyR2), followed by incubation with a secondary HRP-conjugated antibody and chemiluminescence detection. RyR2 phosphorylation levels (pS2808 or pS2814) were normalized against the total protein (measured by anti-RyR2 antibodies). Antibodies: anti-RyR2 phospho-Ser2808 (anti pS2808) and anti-RyR2 phospho-Ser2814 (anti pS2814) were sourced from Badrilla, anti-RyR2 PAB17291 was purchased from Sapphire Bioscience, and anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG were supplied from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Single-channel measurements

SR vesicles suspended in 1 μl of incubation media were added to 1 ml bath solutions and stirred until SR vesicles containing RyR2 were incorporated into artificial lipid bilayers. Bilayers were formed from phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine (8:2 wt/wt) in n-decane (50 mg/ml). For single-channel recording, the cis (cytoplasmic) and trans (luminal) solutions contained 250 mM Cs+ (230 mM cesium methane sulfonate and 20 mM cesium chloride). Channel gating was measured in the presence of cytoplasmic ATP (2 mM), Ca2+ (100 nM), CaM (100 nM), and luminal 0.1 mM Ca2+. All solutions were pH buffered using 10 mM TES (N-tris [hydroxymethyl] methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid; ICN Biomedicals) and titrated to pH 7.4 using CsOH (ICN Biomedicals). A Ca2+ electrode (Radiometer) was used in our experiments to determine the purity of Ca2+ buffers and Ca2+ stock solutions. Free Ca2+ was adjusted with CaCl2 and buffered using 4.5 mM BAPTA (1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, obtained from Invitrogen). Cytoplasmic recording solutions were buffered to a redox potential of −232 mV with glutathione disulfide (GSSG; 0.2 mM) and glutathione (GSH; 4 mM), and luminal solutions were buffered to a redox potential of −180 mV with GSSG (3 mM) and GSH (2 mM), both of which were obtained from MP Biomedicals. The cesium salts were obtained from Aldrich Chemical Company; CaCl2 and MgCl2 were from BDH Chemicals. FKBP12.6 was obtained from Abnova. Solution changes were achieved using continuous local perfusion via a tube placed near the bilayer, which could produce solution change within 1 s. Local perfusion also had the advantage of washing away any remaining phosphorylation reagents from the bilayer that had been introduced with the SR vesicles.

Acquisition and analysis of ion channel recordings

An Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments Pty, Ltd) was used to control the bilayer potential and record unitary currents. Electrical potential differences are expressed as a cytoplasmic potential relative to the luminal potential (at virtual ground). The channel currents were recorded during the experiments using a 50-kHz sampling rate and 5-kHz low pass filtering. Before analysis, the current signal was resampled at 5 kHz and low pass-filtered at 1 kHz with a Gaussian digital filter. Single-channel open probability (Po) and mean open and closed durations (To and Tc) were measured using a threshold discriminator at 50% of channel amplitude. These parameters were measured from single-channel records using Channel3 software (N.W. Laver, [email protected]). Unless otherwise stated, measurements were carried out with the cis solution voltage clamped at −40 mV. Channel substate analysis was carried out using the hidden Markov model (HMM; Chung et al., 1990). The algorithm calculates from the most likely amplitude histogram with background noise subtracted using maximum likelihood criteria.

Dantrolene inhibition was quantified as the ratio of Po in the presence of a cis solution containing 10 μM dantrolene and 100 nM CaM to the mean Po of the bracketing intervals of cis solution with 100 nM CaM but without dantrolene. To investigate the effects of FKBP12.6 on dantrolene inhibition, RyR2 were partially depleted of FKBP12.6 by incubating SR vesicles with either PKA buffers (see above) or buffers containing 20 μM rapamycin for 1 h at room temperature. Reassociation of FKBP12.6 to RyR2, which were previously depleted of FKBP12.6, was achieved by incubating RyR2 in bilayers with dantrolene-free cis solutions containing 2 μM FKBP12.6 for 2 min. Non-physiologically high FKBP12.6 concentrations were utilized to ensure sufficiently high binding rates and to ensure that RyR2 channels had incorporated FKBP12.6.

Statistics

Unless otherwise stated, all data are presented as means ± SEM. Significance was calculated by Student’s t test on normal distributions (single-channel data) and by ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (Western blot data).

Online supplemental material

Results

In vitro PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 modulates dantrolene inhibition of RyR2

We initially set out to test the hypothesis that dantrolene inhibition, in the presence of 100 nM CaM, is only apparent when RyR2 are hyperphosphorylated. We incubated SR vesicles with various phosphatases and kinases and CaM to manipulate RyR2 phosphorylation at both S2808 and S2814 (see Materials and methods) prior to single-channel recording of dantrolene inhibition. Incubation reagents transferred with SR vesicles into the bilayer bath were washed out by local perfusion used during single-channel recording.

Phosphorylation status was confirmed by Western blots shown in Fig. 1, A and B. Initially, sheep RyR2 showed substantial phosphorylation at S2808 (71%) and S2814 (50%; Fig. 1, A and B, minus PP1, CaM, and PKA). Incubation of SR vesicles with PP1 alone dephosphorylated RyR2 at both S2808 and S2814 as previously shown by Huke and Bers (2007). Subsequent incubations with CaMKII or PKA buffers rephosphorylated RyR2 at S2814 or S2808, respectively. Fig. 1 C shows representative single-channel recordings of sheep RyR2 in bilayers and the effects of dantrolene when RyR2 had been subjected to these incubation protocols in SR vesicles. RyR2 channels in their initial phosphorylation state were inhibited by dantrolene (Fig. 1 C, untreated), as were RyR2, which had been dephosphorylated (Fig. 1 C, PP1) and those that were rephosphorylated at S2814 (Fig. 1 C, PP1-CaM). The average data in Fig. 1 D shows that dantrolene caused similar levels of inhibition in all treatment groups except for those exposed to PKA. Treating SR vesicles with control buffers lacking phosphorylating potency (lacking either PKA or CaM) did not alter dantrolene inhibition (Fig. 1 D). The results show that dantrolene inhibition was not affected by phosphorylation at S2814 (compare PP1 versus PP1-CaM). However, rephosphorylation of RyR2 at S2808 was associated with loss of the inhibitory action of dantrolene (Fig. 1 C, compare PP1 and PP1-PKA). See Data S1 for underlying data for Figs. 1 and 3.

In vitro PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 modulates dantrolene inhibition of RyR2. (A) Representative Western blots of RyR2s isolated from sheep heart that were subjected to various incubations to manipulate RyR2 phosphorylation prior to SDS PAGE and Western blot. RyR2 were first maximally dephosphorylated by PP1 and then subjected to CaMKII phosphorylation (in the presence of PKA inhibitor H89) or PKA phosphorylation (in the presence of CaMKII inhibitor KN93). An untreated sample (neither dephosphorylated or subsequently phosphorylated, untreated) is included for comparison. Blots were probed with either antibodies for pS2808 or pS2814 and then stripped and reprobed with antibodies for RyR2. (B) Corresponding average data for RyR2 phosphorylation at S2808 and S2814. Data are normalized to the maximum phosphorylation of S2808 by PKA (left) and to S2814 by CaM (right). Bars denote mean ± SEM of seven independent experiments. Labels indicate P values for comparisons. (C) Representative single-channel recordings of RyR2 that were subjected to various incubations mentioned above. Channel recordings were taken in the presence of 100 nM cytoplasmic Ca2+ and 2 mM ATP and 100 nM CaM. Luminal [Ca2+] = 0.1 mM and membrane potential = −40 mV. Channel openings are downward current jumps from the baseline (dashed line), and arrows indicate the addition of 10 μM dantrolene. (D) RyR2 Po in the presence of 10 μM dantrolene relative to the mean of the bracketing intervals of dantrolene washout. In control experiments, RyR2 were incubated with dephosphorylation buffers lacking PP1 (PP1-ctrl) or with PP1 followed by phosphorylation buffers lacking PKA (PKA-ctrl) or lacking CaM (CaM-ctrl) but including the PKA inhibitor H89 and CaMKII inhibitor KN93. Data in bar graphs are shown as mean ± SEM. Number of samples (n) and number of experiments (N) are shown in each bar. P values denote a significant difference in relative values to 1, which are (left to right) 9 × 10−5, 2 × 10−3, 3 × 10−3, 8 × 10−9, 5 × 10−5, 0.11, and 0.03. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

In vitro PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 modulates dantrolene inhibition of RyR2. (A) Representative Western blots of RyR2s isolated from sheep heart that were subjected to various incubations to manipulate RyR2 phosphorylation prior to SDS PAGE and Western blot. RyR2 were first maximally dephosphorylated by PP1 and then subjected to CaMKII phosphorylation (in the presence of PKA inhibitor H89) or PKA phosphorylation (in the presence of CaMKII inhibitor KN93). An untreated sample (neither dephosphorylated or subsequently phosphorylated, untreated) is included for comparison. Blots were probed with either antibodies for pS2808 or pS2814 and then stripped and reprobed with antibodies for RyR2. (B) Corresponding average data for RyR2 phosphorylation at S2808 and S2814. Data are normalized to the maximum phosphorylation of S2808 by PKA (left) and to S2814 by CaM (right). Bars denote mean ± SEM of seven independent experiments. Labels indicate P values for comparisons. (C) Representative single-channel recordings of RyR2 that were subjected to various incubations mentioned above. Channel recordings were taken in the presence of 100 nM cytoplasmic Ca2+ and 2 mM ATP and 100 nM CaM. Luminal [Ca2+] = 0.1 mM and membrane potential = −40 mV. Channel openings are downward current jumps from the baseline (dashed line), and arrows indicate the addition of 10 μM dantrolene. (D) RyR2 Po in the presence of 10 μM dantrolene relative to the mean of the bracketing intervals of dantrolene washout. In control experiments, RyR2 were incubated with dephosphorylation buffers lacking PP1 (PP1-ctrl) or with PP1 followed by phosphorylation buffers lacking PKA (PKA-ctrl) or lacking CaM (CaM-ctrl) but including the PKA inhibitor H89 and CaMKII inhibitor KN93. Data in bar graphs are shown as mean ± SEM. Number of samples (n) and number of experiments (N) are shown in each bar. P values denote a significant difference in relative values to 1, which are (left to right) 9 × 10−5, 2 × 10−3, 3 × 10−3, 8 × 10−9, 5 × 10−5, 0.11, and 0.03. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

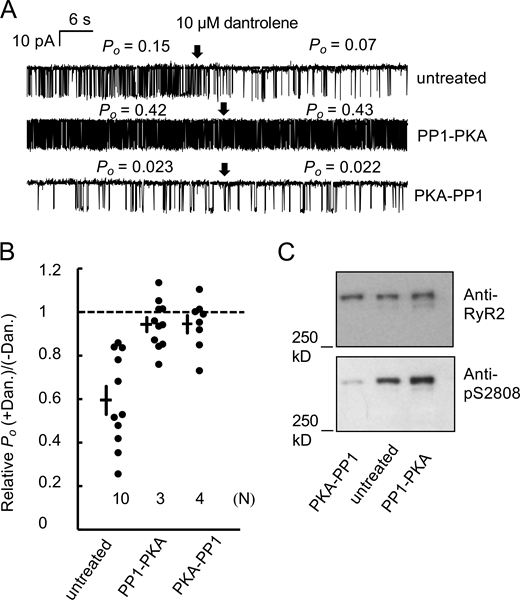

Elimination of dantrolene inhibition by PKA is not reversed by PP1

To further explore the mechanism for the loss of dantrolene inhibition upon in vitro PKA phosphorylation, we tested whether inhibition could be subsequently reinstated by PP1 dephosphorylation. We subjected SR vesicles to two treatments, either PKA phosphorylation followed by PP1 dephosphorylation (PKA-PP1) or vice versa (PP1-PKA, Fig. 2). Both treatments expose RyR2 to PKA but, as Western blots show (Fig. 2 C), the first treatment leaves S2808 unphosphorylated while the second leaves it highly phosphorylated. Single-channel recordings (Fig. 2 A) and averaged data (Fig. 2 B) show that both treatments eliminated dantrolene inhibition of RyR2 in bilayers. Dantrolene inhibition of an untreated sample is included for comparison. Taken together, these results indicate that PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 causes a loss of dantrolene inhibition that can’t be restored by further manipulating its phosphorylation at S2808.

Elimination of dantrolene inhibition by PKA is not reversed by PP1. (A) Representative single-channel recordings of RyR2 that were subjected to in vitro PKA phosphorylation (PP1-PKA, described in Fig. 1) and in vitro dephosphorylation where RyR2s were first subjected to PKA phosphorylation (in the presence of CaMKII inhibitor KN93) and then maximally dephosphorylated by PP1 (PKA-PP1). An untreated sample (neither dephosphorylated nor subsequently phosphorylated, untreated) is included for comparison. Single-channel recording conditions are the same as in Fig. 1, and arrows indicate the addition of 10 μM dantrolene. Channel openings are downward current jumps from the baseline (dashed line). (B) RyR2 Po in the presence of 10 μM dantrolene relative to mean of the bracketing intervals of dantrolene washout are shown for the three incubation conditions above. The dots signify each sample (N represents the number of independent experiments). Data include mean ± SEM for each group. P values denote a significant difference in relative value to 1, which are (left to right) 9 × 10−5, 0.11, and 0.24. (C) Western blot of RyR2s subjected to incubations described in A. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

Elimination of dantrolene inhibition by PKA is not reversed by PP1. (A) Representative single-channel recordings of RyR2 that were subjected to in vitro PKA phosphorylation (PP1-PKA, described in Fig. 1) and in vitro dephosphorylation where RyR2s were first subjected to PKA phosphorylation (in the presence of CaMKII inhibitor KN93) and then maximally dephosphorylated by PP1 (PKA-PP1). An untreated sample (neither dephosphorylated nor subsequently phosphorylated, untreated) is included for comparison. Single-channel recording conditions are the same as in Fig. 1, and arrows indicate the addition of 10 μM dantrolene. Channel openings are downward current jumps from the baseline (dashed line). (B) RyR2 Po in the presence of 10 μM dantrolene relative to mean of the bracketing intervals of dantrolene washout are shown for the three incubation conditions above. The dots signify each sample (N represents the number of independent experiments). Data include mean ± SEM for each group. P values denote a significant difference in relative value to 1, which are (left to right) 9 × 10−5, 0.11, and 0.24. (C) Western blot of RyR2s subjected to incubations described in A. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

In vitro PKA phosphorylation and rapamycin cause dissociation between FKBP12.6 and RyR2

We explored how exposure of RyR2 to PKA may irreversibly alter the RyR2 macromolecular complex. Our experiments were guided by reports that PKA hyperphosphorylation of RyR2 causes dissociation of the regulatory protein FKBP12.6 from the RyR2 complex (Marx et al., 2000). We used co-IP and Western blots to measure relative amounts of FKBP12.0 and FKBP12.6 associated with RyR2s after in vitro PKA phosphorylation (Fig. 3 A). The anti-FKBP H5 antibody recognizes both FKBP isoforms as shown in our co-IP blots, which give a good measure of the relative dissociation of each isoform from RyR2. However, the ratio of FKBP12 to FKBP12.6 is difficult to reliably determine from the band intensities as the relative affinity of this antibody has not been determined. Although this finding has been contradicted in many laboratories, we confirmed that exposure of RyR2 in SR vesicles to PP1 and PKA in either order reduced the amount of FKBP12.6 associated with RyR2 by 41–47% compared with untreated samples but had no significant effect on FKBP12.0 (Fig. 3, PP1-PKA and PKA-PP1). Incubations with PP1-PKA and PKA-PP1 control buffers, lacking either PKA or CaM, did not cause FKBP dissociation.

The association of FKBP12.6 is reduced upon in vitro PKA phosphorylation and incubation with rapamycin. (A) Representative co-IP blots of RyR2s isolated from sheep heart that were subjected to in vitro PKA phosphorylation either before (PKA-PP1) or after (PP1-PKA) dephosphorylation by PP1 or RyR2 subjected to rapamycin (Rap; see Materials and methods). As controls we show an untreated sample (neither dephosphorylated nor subsequently phosphorylated, untreated) and buffer incubation controls (PP1-PKA ctrl and PKA-PP1 ctrl). Blots were probed with antibodies to RyR2 and to an antibody that detects FKBP12.6 and 12.0. (B) Corresponding average data for FKBP12.0 and FKBP12.6 dissociation from RyR2. Band densities were normalized to RyR2 in each lane and expressed relative to normalized band densities of untreated RyR2. Data in bar graphs are shown as mean ± SEM from five independent experiments. P values denote a significant difference in FKBP association with RyR2 compared with untreated RyR2, which are, for FKBP12 (left to right), 0.75, 0.70, 0.57, 0.54, and 0.40, and for FKBP12.6, 0.39, 0.61, 005, 0.14, and 0.00008. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

The association of FKBP12.6 is reduced upon in vitro PKA phosphorylation and incubation with rapamycin. (A) Representative co-IP blots of RyR2s isolated from sheep heart that were subjected to in vitro PKA phosphorylation either before (PKA-PP1) or after (PP1-PKA) dephosphorylation by PP1 or RyR2 subjected to rapamycin (Rap; see Materials and methods). As controls we show an untreated sample (neither dephosphorylated nor subsequently phosphorylated, untreated) and buffer incubation controls (PP1-PKA ctrl and PKA-PP1 ctrl). Blots were probed with antibodies to RyR2 and to an antibody that detects FKBP12.6 and 12.0. (B) Corresponding average data for FKBP12.0 and FKBP12.6 dissociation from RyR2. Band densities were normalized to RyR2 in each lane and expressed relative to normalized band densities of untreated RyR2. Data in bar graphs are shown as mean ± SEM from five independent experiments. P values denote a significant difference in FKBP association with RyR2 compared with untreated RyR2, which are, for FKBP12 (left to right), 0.75, 0.70, 0.57, 0.54, and 0.40, and for FKBP12.6, 0.39, 0.61, 005, 0.14, and 0.00008. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

To test if the dissociation of FKBP12.6 was the primary reason for the loss of dantrolene inhibition after in vitro PKA phosphorylation, we exposed RyR2 to rapamycin, which is also known to dissociate FKBP12.6 from RyR2 (George et al., 2003; Kaftan et al., 1996; Richardson et al., 2017). We incubated RyR2 with 20 μM rapamycin for 1 h at room temperature. Western blots confirmed that rapamycin reduced the amount of FKBP12.6 associated with RyR2 by 60% compared with untreated samples but had no significant effect on FKBP12.0 (Fig. 3, Rap).

Elimination of dantrolene inhibition by in vitro PKA phosphorylation and rapamycin is reversed by exogenous FKBP12.6

Examples of where SR vesicle incubations with either PKA or rapamycin prior to single channel recordings eliminated dantrolene inhibition of RyR2 are shown in Fig. 4 A (first dantrolene exposure). Grouped Po data of RyR2 demonstrate that treatments such as exposure to PKA (Fig. 5 A) or rapamycin (Fig. 5 B) that cause partial dissociation of FKBP12.6 abolish dantrolene inhibition, suggesting that the presence of FKBP12.6 in the RyR2 macromolecular complex is necessary for dantrolene inhibition. To determine if the addition of exogenous FKBP12.6 could restore dantrolene inhibition in these channels, we then added FKBP12.6 (2 μM) to the bath via the perfusion system for a period of 2 min and repeated the dantrolene inhibition measurement (Fig. 4 A, second dantrolene exposure). The grouped Po data show that the addition of FKBP12.6 restored dantrolene inhibition, confirming that FKBP12.6 within the macromolecular complex is necessary for dantrolene to be an inhibitor of RyR2. We also examined RyR2 mean open and closed times in response to dantrolene, where we found that in one case we could resolve that dantrolene inhibited by both increasing closed time and decreasing open times (Fig. 5 B, red symbols). The addition of FKBP12.6 had no significant effect on RyR2 open probability (Po = 0.18 before vs. 0.28 after FKBP12.6; n = 3, P = 0.55). However, we did see a consistent 6% increase in channel conductance (P = 0.02) with FKBP12.6 but with no indication of altered substate activity in the amplitude histograms (Fig. 4 B).

Effect of FKBP12.6 addition to channels previously incubated by PKA and rapamycin. (A) Single-channel recording of RyR2s that were subjected to in vitro dephosphorylation upon PKA phosphorylation (PKA-PP1, described in Fig. 2) and rapamycin (RyR2s were subjected to 20 μM rapamycin for 1 h at room temperature prior to channel recordings) and then exposed to 10 μM dantrolene after addition of 2 μM FKBP12.6 to the cytoplasmic bath for 2 min. The traces are presentative of three experiments where dantrolene inhibition was measured both before and after incubation with FKBP12.6 in the same channel. Single-channel recording conditions are the same as in Fig. 1, and channel openings are downward current jumps from the baseline. (B) Maximum likelihood amplitude distributions generated by the HMM (see Materials and methods) of channel activity from the bottom trace in A from regions marked by the dashed and solid lines beneath. The peaks indicate the open and closed current levels on the recordings.

Effect of FKBP12.6 addition to channels previously incubated by PKA and rapamycin. (A) Single-channel recording of RyR2s that were subjected to in vitro dephosphorylation upon PKA phosphorylation (PKA-PP1, described in Fig. 2) and rapamycin (RyR2s were subjected to 20 μM rapamycin for 1 h at room temperature prior to channel recordings) and then exposed to 10 μM dantrolene after addition of 2 μM FKBP12.6 to the cytoplasmic bath for 2 min. The traces are presentative of three experiments where dantrolene inhibition was measured both before and after incubation with FKBP12.6 in the same channel. Single-channel recording conditions are the same as in Fig. 1, and channel openings are downward current jumps from the baseline. (B) Maximum likelihood amplitude distributions generated by the HMM (see Materials and methods) of channel activity from the bottom trace in A from regions marked by the dashed and solid lines beneath. The peaks indicate the open and closed current levels on the recordings.

Elimination of dantrolene inhibition by in vitro PKA phosphorylation and rapamycin is reversed by FKBP12.6. (A) RyR2 Po and mean open and closed dwell times (To and Tc) in the presence of 10 μM dantrolene relative to the mean of the bracketing intervals of dantrolene washout. RyR2s were subjected to in vitro dephosphorylation upon PKA phosphorylation prior to single channel recordings (PKA-PP1) or subsequently incubated with FKBP12.6 (FKBP12.6). An untreated sample is included for comparison. (B) As in A, except that RyR2 were subjected to rapamycin incubation instead of PKA and PP1. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. P values denote a significant difference in relative value to 1, which in A are (left to right) 9 × 10−5, 0.2, 0.007, 0.72, 0.77, 0.48, 0.08, 0.92, and 0.074. In B these are 9 × 10−5, 0.08, 0.003, 0.72, 0.94. 0.021, 0.08, 0.05, and 0.043.

Elimination of dantrolene inhibition by in vitro PKA phosphorylation and rapamycin is reversed by FKBP12.6. (A) RyR2 Po and mean open and closed dwell times (To and Tc) in the presence of 10 μM dantrolene relative to the mean of the bracketing intervals of dantrolene washout. RyR2s were subjected to in vitro dephosphorylation upon PKA phosphorylation prior to single channel recordings (PKA-PP1) or subsequently incubated with FKBP12.6 (FKBP12.6). An untreated sample is included for comparison. (B) As in A, except that RyR2 were subjected to rapamycin incubation instead of PKA and PP1. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. P values denote a significant difference in relative value to 1, which in A are (left to right) 9 × 10−5, 0.2, 0.007, 0.72, 0.77, 0.48, 0.08, 0.92, and 0.074. In B these are 9 × 10−5, 0.08, 0.003, 0.72, 0.94. 0.021, 0.08, 0.05, and 0.043.

Discussion

In sheep RyR2, we found no evidence that dantrolene inhibition (with the prerequisite CaM in solution and the RyR2 complex) directly depended on the RyR2 phosphorylation state at either S2808 or S2814. Dantrolene inhibition was unaffected by the dephosphorylation of RyR2 at both S2808 and S2814 (Fig. 1) nor was it affected by increasing phosphorylation at S2814. Even in the case where PKA incubation of SR vesicles resulted in the abolition of dantrolene inhibition, we found no evidence that this was a direct consequence of hyperphosphorylation of S2808 because subsequent dephosphorylation of the channel by PP1 didn’t restore dantrolene inhibition (Fig. 2). However, the co-IP experiments showed that incubating SR vesicles in PKA caused partial dissociation of FKBP12.6 from the solubilized RyR2 complex (Fig. 3) that would reflect either a loss of FKBP12.6 from RyR2 in bilayer experiments or at least a weakening of the FKBP12.6/RyR2 interaction (FKBP association with RyR2 determined from co-IP is only indicative of what may be happening in the bilayer). This led us to test the hypothesis that the presence of FKBP12.6 in the macromolecular complex, as well as CaM, is required for dantrolene inhibition. Rapamycin, which is shown here (Fig. 3) and elsewhere (George et al., 2003; Kaftan et al., 1996; Richardson et al., 2017) to dissociate FKBP12.6 from RyR2, also eliminates dantrolene inhibition (Figs. 4 and 5). Moreover, the elimination of dantrolene inhibition by rapamycin and PKA is reversed by subsequent incubations in FKBP12.6 (Figs. 4 and 5). Taken together, these findings indicate that the inhibitory action of dantrolene depends not only on CaM but also on the presence of FKBP12.6. The fact that CaM binding to RyR2 is reduced by FKBP12.6 dissociation from the RyR2 complex or RyR2 phosphorylation by PKA and/or CaMKII (Ono et al., 2010; Uchinoumi et al., 2016) raises the possibility that loss of dantrolene inhibition seen here is due to the loss of CaM that is a prerequisite for dantrolene inhibition (Oo et al., 2015). However, we consider this unlikely because these same studies demonstrating loss of CaM binding to RyR2 also show that CaM binding is restored again by dantrolene, so CaM present in our bathing solutions would quickly reattach to RyR2 during our measurements of dantrolene inhibition.

The lack of effect of exogenous FKBP12.6 on RyR2 gating and substate activity (absence of dantrolene) was also reported by Galfre et al. (2012), who did a similar experiment by adding FKBP12.6 to RyR2 that had been depleted of endogenous FKBP12.6. However, others have reported that loss of FKBP12.6 from RyR2 is associated with increased substate activity in RyR2 (Marx et al., 2000; Wehrens et al., 2003).

Dantrolene binds to a peptide corresponding to residues 601–620 of RyR2 (Paul-Pletzer et al., 2005). Combined FRET and cryoEM techniques have mapped this dantrolene-binding sequence to domain 9 (SPRY1) adjacent to the FKBP12.6 binding site (Wang et al., 2011). Early cryo-EM maps located the FKBP12.6 binding site at the interface between the SPRY1, SPRY3, and handle domains (i.e., domain 9, 5, and 3, respectively; Samso et al., 2006). More recent higher-resolution structures of both RyR1 and RyR2 reveal that FKBP12 and 12.6 bind to the same site in the cleft formed by the SPRY1, SPRY3, NTD, and handle domains (Chi et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2015). Although involvement of FKBP12.6 in dantrolene inhibition is consistent with this structural data, it is not clear whether FKBP12.6 is necessary for dantrolene binding or if FKBP12.6 forms a part of the transduction mechanism connecting dantrolene binding with RyR2 inhibition. In the case of the RyR1–FKBP12 complex, the architecture and flexibility of helical domain 2 (HD2, which forms the clamp domain along with SPRY1) plays a central role in coordinating the allosteric activity among RyR1 subunits (Samsó, 2017). In the case of RyR2, FKBP12.6 enhances the rigidity of the HD2 domain (Yuan et al., 2014) and induces inward and counterclockwise rotation of channel and central domains and outward and counterclockwise rotation of the HD1, handle, and N-terminal domains (Chi et al., 2019).

Our co-IP blots in Fig. 3 A show two clear bands corresponding to each FKBP isoform with the 12 kD isoform band being the most prominent, consistent with our previous results in sheep (Richardson et al., 2017) as well as mouse and pig but different to that in rabbit and rat where only one isoform was detected (Guo et al., 2010; Zissimopoulos et al., 2012). Intuitively, one would not expect that dantrolene inhibition of RyR2 would correlate so strongly with the presence of FKBP12.6 given the strong presence of FKBP12. However, both FKBP isoforms are known to individually modulate RyR2 activity in vivo. Ca sparks in cardiomyocytes from FKBP knockout mice lacking either isoform showed increased amplitude and frequency compared with wild type (Guo et al., 2010; Shou et al., 1998; Xin et al., 2002) while FKBP overexpressing mouse models showed the converse (Prestle et al., 2001), indicating that FKBP12.6, even with substochiometric binding to RyR2 can have an impact on RyR2 function.

We used incubations with either rapamycin or PKA to selectively dissociate FKBP12.6 from RyR2. Rapamycin has long been used to dissociate FKBP from RyR2 (e.g., Brilliantes et al., 1994; Guo et al., 2010; Kaftan et al., 1996; Timerman et al., 1996). Several studies have shown that rapamycin has direct effects on RyRs, independent of FKBP dissociation (Ahern et al., 1997a; Ahern et al., 1997b; Xiao et al., 2007). However, these actions are readily reversible, so they should be absent after rapamycin removal in our experiments. We found that incubation of RyR2 with exogenous PKA selectively dissociated FKBP12.6 from RyR2 (Fig. 3), which agrees with similar experiments reported in the seminal work by Marx et al. (2000). However, other laboratories have not established a direct link between PKA treatment and FKBP dissociation (Guo et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2002; Stange et al., 2003; Xiao et al., 2006). The controversy is not yet resolved and the experiments here are not designed to resolve it.

While our Western blot experiments demonstrated that we could manipulate RyR2 phosphorylation at S2808 and S2814, we were unable to monitor the phosphorylation status of S2030. Moreover, there is no consensus that S2030 is PKA phosphorylated nor is it generally known whether PP1 can dephosphorylate S2030. Hence, we cannot draw conclusions about the relative roles of S2808 and S2030 in FKBP dissociation. Marx’s group has attributed PKA-induced dissociation of FKBP to hyperphosphorylation of S2808 (Marx et al., 2000). Although the literature is divided on this point, there is consensus that hyperphosphorylation at S2030 (Xiao et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2006) or S2814 do not contribute to FKBP dissociation (Wehrens et al., 2004). However, FKBP dissociation by a PKA site other than S2808 would explain why dantrolene had different actions on untreated RyR2 and PKA-treated RyRs even though they had similar levels of S2808 phosphorylation (Fig. 1 B and Fig. 2 B; the reason for the high levels of S2808 phosphorylation in untreated sheep RyR2s is not clear but they might be due to catecholaminergic stress in sheep prior to harvest). Alternatively, in vivo and in vitro PKA phosphorylation have distinct effects on FKBP12.6 binding and dantrolene inhibition.

In summary, (1) exposure of RyR2 to PKA or rapamycin dissociates FKBP from RyR2; (2) the PKA and rapamycin experiments demonstrate a correlation between FKBP12.6 dissociation and dantrolene inhibition; and (3) dantrolene inhibition does not directly depend on the RyR2 phosphorylation at either S2808 or S2814. Overall, we show that dantrolene inhibition is very sensitive to the molecular organization of the RyR2 complex and that its inhibition of RyR2 depends on, at least, the presence of both FKBP12.6 and CaM.

Data availability

The data underlying Fig. 1, B and D; and Fig. 3 B are available in Data S1.

Acknowledgments

David A. Eisner served as editor.

We wish to thank Paul Johnson for assisting with the experiments.

This work was funded by NSW Health infrastructure grant through the Hunter Medical Research Institute to D.R. Laver and the National Health and Medical Research Council Project grant (APP1005974) to D.R. Laver.

Author contributions: Participated in research design: K. Walweel, D.R. Laver, N. Beard. Conducted experiments K. Walweel, N. Beard. Contributed to new reagents or analytic tools: D.R. Laver, D.F. Van Helden. Performed data analysis: K. Walweel, D.R. Laver, and N. Beard. Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: D.R. Laver, D.F. Van Helden, K. Walweel, and N. Beard.

References

Author notes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests exist.

![In vitro PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 modulates dantrolene inhibition of RyR2. (A) Representative Western blots of RyR2s isolated from sheep heart that were subjected to various incubations to manipulate RyR2 phosphorylation prior to SDS PAGE and Western blot. RyR2 were first maximally dephosphorylated by PP1 and then subjected to CaMKII phosphorylation (in the presence of PKA inhibitor H89) or PKA phosphorylation (in the presence of CaMKII inhibitor KN93). An untreated sample (neither dephosphorylated or subsequently phosphorylated, untreated) is included for comparison. Blots were probed with either antibodies for pS2808 or pS2814 and then stripped and reprobed with antibodies for RyR2. (B) Corresponding average data for RyR2 phosphorylation at S2808 and S2814. Data are normalized to the maximum phosphorylation of S2808 by PKA (left) and to S2814 by CaM (right). Bars denote mean ± SEM of seven independent experiments. Labels indicate P values for comparisons. (C) Representative single-channel recordings of RyR2 that were subjected to various incubations mentioned above. Channel recordings were taken in the presence of 100 nM cytoplasmic Ca2+ and 2 mM ATP and 100 nM CaM. Luminal [Ca2+] = 0.1 mM and membrane potential = −40 mV. Channel openings are downward current jumps from the baseline (dashed line), and arrows indicate the addition of 10 μM dantrolene. (D) RyR2 Po in the presence of 10 μM dantrolene relative to the mean of the bracketing intervals of dantrolene washout. In control experiments, RyR2 were incubated with dephosphorylation buffers lacking PP1 (PP1-ctrl) or with PP1 followed by phosphorylation buffers lacking PKA (PKA-ctrl) or lacking CaM (CaM-ctrl) but including the PKA inhibitor H89 and CaMKII inhibitor KN93. Data in bar graphs are shown as mean ± SEM. Number of samples (n) and number of experiments (N) are shown in each bar. P values denote a significant difference in relative values to 1, which are (left to right) 9 × 10−5, 2 × 10−3, 3 × 10−3, 8 × 10−9, 5 × 10−5, 0.11, and 0.03. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.](https://cdn.rupress.org/rup/content_public/journal/jgp/155/8/10.1085_jgp.202213277/1/m_jgp_202213277_fig1.png?Expires=1773909769&Signature=iswci3C-U8dH~muX-O2YLnrKDcp7vPkK697fD2mxue-o-me~LVxcJ7LI8l4K4JFG6oWUrOvWTQnRVOnjnZHZ0NpVD0uZIvcrn6jfMRbSyZaLi3Q98fAOABWHfhnpvvp~TW1KZTs2CDwnF~ismz7Q2Box7U2gsFy9c2hFqQzh74SfADJ80FztmyUYnLFn9UzvNmr36k96eHmFFDOvEPKMcLCWpZV7sUfWgg2kc~KRohk5Qd8fWBZmf6o5KQGihWhUMI4KJuu-8XIZo-5ncr0RFZYUHo~zQOxQotgFxFavoF3FWMBQyJaqyI4LzJwwu6MkuprMluEojSXQdoo~dlT6zQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)