Neuronal mitochondrial function is critical for orchestrating inter-tissue communication essential for overall fitness. Despite its significance, the molecular mechanism underlying the impact of prolonged mitochondrial stresses on neuronal activity and how they orchestrate metabolism and aging remains elusive. Here, we identified the evolutionarily conserved transmembrane protein XBX-6/TMBIM-2 as a key mediator in the neuronal-to-intestinal mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt). Our investigations reveal that intrinsic neuronal mitochondrial stress triggers spatiotemporal Ca2+ oscillations in a TMBIM-2-dependent manner through the Ca2+ efflux pump MCA-3. Notably, persistent Ca2+ oscillations at synapses of ADF neurons are critical for facilitating serotonin release and the subsequent activation of the neuronal-to-intestinal UPRmt. TMBIM2 expression diminishes with age; however, its overexpression counteracts the age-related decline in aversive learning behavior and extends the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. These findings underscore the intricate integration of chronic neuronal mitochondrial stress into neurotransmission processes via TMBIM-2-dependent Ca2+ equilibrium, driving metabolic adaptation and behavioral changes for the regulation of aging.

Introduction

The nervous system plays a pivotal role in orchestrating organism-wide adaptations, enabling effective responses to local stress stimuli and ultimately enhancing overall fitness (Carter, 2019; Li and Sheng, 2022; Monzel et al., 2023; Südhof, 2018; van der Kolk, 2006). As non-mitotic and long-lived cells, neurons are exceptionally susceptible to proteotoxic challenges and metabolic stresses that become more pronounced with aging (Devine and Kittler, 2018; Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015). These age-related disturbances in neuronal mitochondrial function have far-reaching effects beyond the neurons themselves. Such disruptions can exert effects on the metabolic status of peripheral tissues and may lead to behavioral modifications (Bar-Ziv et al., 2020). Notably, the accumulation of toxic and aggregated proteins within neurons often coincides with metabolic abnormalities in peripheral tissues, a phenomenon frequently observed in the context of neurodegenerative diseases (Cai et al., 2012; Duarte et al., 2013).

Extensive studies in Caenorhabditis elegans have demonstrated that neuronal mitochondrial stress can trigger non-autonomous effects in peripheral tissues. This includes the activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) within the intestine, facilitated by secreted factors like the morphogen Wnt/EGL-20, TGF-β, a variety of neuropeptides, and neurotransmitters such as serotonin (Berendzen et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2021; Shao et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2018). The UPRmt is a transcriptional response that orchestrates the upregulation of genes involved in maintaining mitochondrial quality control and metabolic adaptations, ultimately restoring mitochondrial proteostasis (Anderson and Haynes, 2020; Shpilka and Haynes, 2018; Zhu et al., 2022). Various perturbations in neuronal mitochondria, such as diminished mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) activity, disruptions in mitochondrial dynamics, and disturbances in mitochondrial proteostasis, have all been linked to cell non-autonomous UPRmt activation (Berendzen et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2021; Durieux et al., 2011; Li et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2022; Shao et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021b; Zhang et al., 2018). These findings collectively emphasize the significant role played by neuronal mitochondrial stress in orchestrating systemic stress adaptation in the organism.

The indispensability of mitochondria in the homeostatic regulation of neurons is evident, with their multifaceted role encompassing the generation of ATP and calcium buffering capacity crucial for presynaptic release properties (Gherardi et al., 2020). Mitochondrial calcium, in particular, not only enhances mitochondrial activity but also promotes the functionality of mitochondrial enzymes (Gherardi et al., 2020). An excessive accumulation of Ca2+ within mitochondria can directly disrupt mitochondrial function and potentially trigger apoptosis (Berridge et al., 2003; Giorgi et al., 2018; Orrenius et al., 2003). Despite this understanding, the intricate molecular mechanism governing how enduring chronic mitochondrial stress modulates neurotransmission, effectively coordinating systemic stress communication, and influencing the aging process, remains largely unknown.

To investigate how organisms coordinate systemic stress responses in the face of persistent neuronal mitochondrial perturbations, we conducted a genetic screening in C. elegans to identify factors involved in the activation of neuronal-to-intestinal UPRmt. Our screening identified a mutant, xbx-6, which exhibited a strong suppression of UPRmt. The xbx-6 encodes a transmembrane protein belonging to the evolutionarily conserved transmembrane Bax-inhibiting domain (TMBIM) family, showing homology to TMBIM2. Intriguingly, we observed a striking phenomenon: perturbations in neuronal mitochondria led to the generation of Ca2+ oscillations that persisted for several days in vivo. This process is dependent on the presence of xbx-6/tmbim-2. Our findings uncovered that TMBIM-2 couples with a Ca2+ pump, MCA-3 (known as PMCA in mammals), to re-establish low Ca2+ levels after spikes induced by mitochondrial stress. The enduring Ca2+ fluctuations observed at synapses of ADF neurons play a pivotal role in facilitating serotonin release, which is crucial for activating the neuronal-to-intestinal UPRmt under conditions of persistent neuronal mitochondrial stress. Additionally, our analysis of existing datasets revealed a consistent trend: the expression of TMBIM2 in neurons decreases with age across diverse species, including C. elegans, mice, and humans. Notably, overexpression of TMBIM-2 in C. elegans neurons not only mitigates age-related cognitive decline but also extends lifespan. In summary, our study provides insights into the intricate network of interactions governing the response of neurotransmission to chronic neuronal mitochondrial stresses via Ca2+ signaling.

Results

XBX-6/TMBIM-2 functions in neurons to coordinate neuronal-to-intestinal UPRmt activation

To investigate the intricate mechanism governing the coordination of neuronal-to-intestinal mitochondrial stress communication and its consequential impact on systemic metabolic changes, we initiated a genetic suppressor screen. We aimed to identify mutants displaying impaired communication of the UPRmt signal from neurons to the intestine. We focused on the neuronal expression of a Wnt ligand, EGL-20, driven by the pan-neuron promoter rgef-1, as evidenced by its impact on the induction of the UPRmt reporter DVE-1::GFP in the intestine of C. elegans (Li et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2018).

We screened ∼3,400 mutagenized genomes, identifying 42 mutants that exhibited compromised activation of intestinal UPRmt upon neuronal expression of Wnt/EGL-20. Among these mutants, yth57 stood out due to its robust suppression of neuronal-to-intestinal UPRmt activation but did not exhibit a similar inhibitory effect on UPRmt activation driven by intestinal Wnt/EGL-20 overexpression under the control of intestinal (gly-19) promoters (Fig. 1, A and B). This unique phenotype directed us to further characterize the yth57 mutant. Whole-genome sequencing revealed that yth57 carries a G to A nucleotide mutation in the xbx-6 gene, leading to the amino acid substitution Val275Ile (Fig. 1 C). xbx-6 encodes a transmembrane protein that belongs to the evolutionarily conserved transmembrane BAX inhibitor motif-containing (TMBIM) proteins. Notably, the homology between XBX-6 and the human TMBIM2 prompted us to generate transgenic worms expressing hTMBIM2 (Fig. S1 A). The alpha fold result showed that the C segment of TMBIM-2 contained seven transmembrane regions (Fig. S1, B and C). Expression of hTMBIM2 partially restored intestinal UPRmt activation in tmbim-2(yth57) mutants with neuronal Wnt/EGL-20 expression, indicating a high degree of conservation in the function of TMBIM2 (Fig. S1, D and E). Thus, we designated xbx-6 as tmbim-2, facilitating a clearer connection between our findings and its human counterpart (Liu, 2017; Rojas-Rivera and Hetz, 2015; Zhang et al., 2018).

XBX-6/TMBIM-2 deficiency suppressed the neuronal-to-intestinal UPR mt activation. (A) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: bright-field images of aligned, wild-type (WT) animals. The area shown in white box is the region for imaging in Fig. 1(a); the expression pattern of the dve-1(zcIs39[dve-1p::dve-1::gfp]) reporter in WT day 2 adult animals (b); dve-1 reporter expression in neuronal EGL-20 (ythIs3[rgef-1p::egl-20 + myo-2p::tdtomato]) animals (c); neuronal EGL-20; tmbim-2(yth57) animals (d); intestinal EGL-20 (ythIs1[gly-19p::egl-20]) animals(e); intestinal EGL-20; tmbim-2(yth57) animals (f), respectively. The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (B) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in A. (C) A schematic diagram of three mutant alleles yth26, yth57, and yth130 of tmbim-2. (D) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: dve-1 reporter expression in neuronal cox-5B knockdown (uthIs375[unc-119p::cox-5B HP; pRF(rol-6)]); sid-1(qt9) animals (a); neuronal cox-5B knockdown; sid-1(qt9); tmbim-2(yth130) animals (b); WT animals (c); and tmbim-2 (yth57)(d) grown on cox-5B RNAi from hatching. The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (E) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in D. (F) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: the expression pattern of dve-1 reporter in WT animals expressing neuronal Q40 (rmIs110[rgef-1p::Q40::YFP](a); dve-1 reporter expression in tmbim-2 (yth57) animals expressing neuronal Q40 (b); intestinal rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx289[gly-19p::tmbim-2])(c); pan-neuronal rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx290[rgef-1p::tmbim-2])(d); ciliated-neuronal rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx476[xbx-1p::tmbim-2])(e). The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (G) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in F. (H) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: dve-1 reporter expression in tmbim-2 (yth57) animals expressing neuronal Q40::YFP (a); touch neurons rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx568[mec-7p::tmbim-2])(b); NSM neurons rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx772[tph-1(s)p::tmbim-2])(c); ADL neurons rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx569[srh-220p::tmbim-2])(d); ADF/NSM neurons rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx773[tph-1(l)p::tmbim-2])(e). The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (I) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in H. ***P < 0.001, ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. n ≥ 15 worms. Scale bar, 250 μm.

XBX-6/TMBIM-2 deficiency suppressed the neuronal-to-intestinal UPR mt activation. (A) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: bright-field images of aligned, wild-type (WT) animals. The area shown in white box is the region for imaging in Fig. 1(a); the expression pattern of the dve-1(zcIs39[dve-1p::dve-1::gfp]) reporter in WT day 2 adult animals (b); dve-1 reporter expression in neuronal EGL-20 (ythIs3[rgef-1p::egl-20 + myo-2p::tdtomato]) animals (c); neuronal EGL-20; tmbim-2(yth57) animals (d); intestinal EGL-20 (ythIs1[gly-19p::egl-20]) animals(e); intestinal EGL-20; tmbim-2(yth57) animals (f), respectively. The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (B) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in A. (C) A schematic diagram of three mutant alleles yth26, yth57, and yth130 of tmbim-2. (D) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: dve-1 reporter expression in neuronal cox-5B knockdown (uthIs375[unc-119p::cox-5B HP; pRF(rol-6)]); sid-1(qt9) animals (a); neuronal cox-5B knockdown; sid-1(qt9); tmbim-2(yth130) animals (b); WT animals (c); and tmbim-2 (yth57)(d) grown on cox-5B RNAi from hatching. The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (E) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in D. (F) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: the expression pattern of dve-1 reporter in WT animals expressing neuronal Q40 (rmIs110[rgef-1p::Q40::YFP](a); dve-1 reporter expression in tmbim-2 (yth57) animals expressing neuronal Q40 (b); intestinal rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx289[gly-19p::tmbim-2])(c); pan-neuronal rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx290[rgef-1p::tmbim-2])(d); ciliated-neuronal rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx476[xbx-1p::tmbim-2])(e). The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (G) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in F. (H) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: dve-1 reporter expression in tmbim-2 (yth57) animals expressing neuronal Q40::YFP (a); touch neurons rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx568[mec-7p::tmbim-2])(b); NSM neurons rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx772[tph-1(s)p::tmbim-2])(c); ADL neurons rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx569[srh-220p::tmbim-2])(d); ADF/NSM neurons rescue TMBIM-2 (ythEx773[tph-1(l)p::tmbim-2])(e). The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (I) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in H. ***P < 0.001, ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. n ≥ 15 worms. Scale bar, 250 μm.

XBX-6/TMBIM-2 functions in neurons to coordinate neuronal-to-intestinal UPR mt activation. (A) Sequence alignment of TMBIM2 proteins across species. (B) Alphafold predicted the protein structure of TMBIM-2. (C) A PAE (Predicted Aligned Error) plot, showing regions of high confidence (dark green) and low confidence (pale green) for the AlphaFold prediction of TMBIM-2 structure. (D) Representative photomicrograph of dve-1 reporter in neuronal EGL-20; tmbim-2 animals with or without human TMBIM2 overexpressing (tmbim-2p::hTmbim2) rescue. (E) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in D. n ≥ 9 biologically independent samples. (F) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter expression in neuronal EGL-20 overexpressing (ythIs3[rgef-1p::egl-20 + myo-2p::tdtomato]) and intestinal EGL-20 overexpressing (ythIs1[gly-19p::egl-20]) animals in WT or tmbim-2(yth26) background, respectively. The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (G) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in F. n ≥ 12 worms. (H) Quantification of tmbim-2 mRNA levels in WT (yellow), tmbim-2 (yth57) (blue), tmbim-2 (yth26) (purple), tmbim-2 (yth130) (grey), and tmbim-2 (yth92) (pink) animals. Error bars, SEM; n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (I) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter (zcIs3[hsp-6p::gfp]) expression in neuronal EGL-20 overexpressing (ythIs3[rgef-1p::egl-20 + myo-2p::tdtomato]) animals in WT or tmbim-2(yth92) background, respectively. (J) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in I. n ≥ 15 worms. (K) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter (zcIs3[hsp-6p::gfp]) expression in neuronal Q40::YFP overexpressing animals in WT or tmbim-2(yth92) background, respectively. (L) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression. The genotypes are as in K. n ≥ 15 worms. (M) qRT-PCR analysis of transcripts (n = 3 biologically independent samples) in neuronal cox-5B knockdown animals in WT or tmbim-2 background. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (**P < 0.01; *P < 0.05). (N) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: dve-1 reporter expression in tmbim-2 (yth57) animals expressing neuronal EGL-20 (a); TMBIM-2 rescue (ythIs62[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::GFP; unc-119(+)]) (b); TMBIM-2 pan-neuron rescue (ythEx226[rgef-1p::tmbim-2::mcherry::HA; pRF4(rol-6)]) (c); TMBIM-2 intestinal rescue (ythEx229[gly-19p::tmbim-2::mcherry::HA; pRF4(rol-6)]) (d). The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (O) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in N. (P) Quantification of tmbim-2 mRNA levels in WT, TMBIM-2 overexpression and intestinal TMBIM-2 overexpression animals. Error bars, SEM; n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (Q) Representative photomicrograph of dve-1 reporter in neuronal Q40::YFP overexpressing animals with or without ADF neuronal TMBIM-2 knockout (ythEx574[srh-142p::Cas9::u6p::tmbim-2 sgRNA]). (R) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in Q. n ≥ 15 worms. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Scale bar, 250 μm.

XBX-6/TMBIM-2 functions in neurons to coordinate neuronal-to-intestinal UPR mt activation. (A) Sequence alignment of TMBIM2 proteins across species. (B) Alphafold predicted the protein structure of TMBIM-2. (C) A PAE (Predicted Aligned Error) plot, showing regions of high confidence (dark green) and low confidence (pale green) for the AlphaFold prediction of TMBIM-2 structure. (D) Representative photomicrograph of dve-1 reporter in neuronal EGL-20; tmbim-2 animals with or without human TMBIM2 overexpressing (tmbim-2p::hTmbim2) rescue. (E) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in D. n ≥ 9 biologically independent samples. (F) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter expression in neuronal EGL-20 overexpressing (ythIs3[rgef-1p::egl-20 + myo-2p::tdtomato]) and intestinal EGL-20 overexpressing (ythIs1[gly-19p::egl-20]) animals in WT or tmbim-2(yth26) background, respectively. The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (G) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in F. n ≥ 12 worms. (H) Quantification of tmbim-2 mRNA levels in WT (yellow), tmbim-2 (yth57) (blue), tmbim-2 (yth26) (purple), tmbim-2 (yth130) (grey), and tmbim-2 (yth92) (pink) animals. Error bars, SEM; n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (I) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter (zcIs3[hsp-6p::gfp]) expression in neuronal EGL-20 overexpressing (ythIs3[rgef-1p::egl-20 + myo-2p::tdtomato]) animals in WT or tmbim-2(yth92) background, respectively. (J) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in I. n ≥ 15 worms. (K) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter (zcIs3[hsp-6p::gfp]) expression in neuronal Q40::YFP overexpressing animals in WT or tmbim-2(yth92) background, respectively. (L) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression. The genotypes are as in K. n ≥ 15 worms. (M) qRT-PCR analysis of transcripts (n = 3 biologically independent samples) in neuronal cox-5B knockdown animals in WT or tmbim-2 background. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (**P < 0.01; *P < 0.05). (N) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating: dve-1 reporter expression in tmbim-2 (yth57) animals expressing neuronal EGL-20 (a); TMBIM-2 rescue (ythIs62[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::GFP; unc-119(+)]) (b); TMBIM-2 pan-neuron rescue (ythEx226[rgef-1p::tmbim-2::mcherry::HA; pRF4(rol-6)]) (c); TMBIM-2 intestinal rescue (ythEx229[gly-19p::tmbim-2::mcherry::HA; pRF4(rol-6)]) (d). The posterior region of the intestine where DVE-1::GFP is induced or suppressed is highlighted. (O) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in N. (P) Quantification of tmbim-2 mRNA levels in WT, TMBIM-2 overexpression and intestinal TMBIM-2 overexpression animals. Error bars, SEM; n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (Q) Representative photomicrograph of dve-1 reporter in neuronal Q40::YFP overexpressing animals with or without ADF neuronal TMBIM-2 knockout (ythEx574[srh-142p::Cas9::u6p::tmbim-2 sgRNA]). (R) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in Q. n ≥ 15 worms. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Scale bar, 250 μm.

To determine the involvement of TMBIM-2 in cell non-autonomous activation of UPRmt triggered by various forms of neuronal mitochondrial perturbations, we employed CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to generate distinct alleles of tmbim-2 deletion mutants, namely yth26 and yth130, across different genetic backgrounds (Fig. 1 C). The absence of tmbim-2 strongly suppressed the intestinal UPRmt activation in response to either neuronal Q40::YFP expression or neuronal knockdown (KD) of cytochrome oxidase assembly protein (cox-5B/cco-1) by expressing cox-5B hairpin (HP) under unc-119 promoter (Fig. 1, D–G and Fig. S1, F–M). In contrast, tmbim-2 mutants did not impact cell-autonomous intestinal UPRmt activation caused by cox-5B RNAi (Fig. 1, D and E; and Fig. S1, F and G).

To determine whether TMBIM-2’s role in cell non-autonomous UPRmt activation is linked to its neuronal expression, we expressed tmbim-2 under tissue-specific promoters in a tmbim-2 mutant background. Expression of tmbim-2 driven by the pan-neuron promoter rgef-1p or the ciliated sensory neuron promoter xbx-1p effectively rescued the suppressed intestinal UPRmt activation in tmbim-2 mutants with either neuronal Wnt/EGL-20 expression or neuronal Q40::YFP expression (Fig. 1, F and G; and Fig. S1, N–P). Furthermore, restoring suppressed intestinal UPRmt activation in tmbim-2 mutants was also achieved by expressing tmbim-2 exclusively in two amphid sensory ADF neurons but not in NSM or other sensory neurons (Fig. 1, H and I). In contrast, the expression of tmbim-2 driven by gly-19 promoters failed to restore the intestinal UPRmt activation in tmbim-2(yth57) mutants with neuronal Wnt/EGL-20 or Q40::YFP expression (Fig. 1, F and G; and Fig. S1, N–P). Additionally, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of tmbim-2 in ADF neurons robustly suppressed the intestinal activation of UPRmt in response to neuronal Q40::YFP expression (Fig. S1, Q and R). These results indicate a critical function of tmbim-2 within ADF neurons in orchestrating intestinal activation of UPRmt in response to neuronal mitochondrial perturbations.

The expression and subcellular distribution of TMBIM-2 in response to neuronal mitochondrial stress

The TMBIM gene family, distinguished by seven transmembrane domains, exhibits diverse intracellular membrane localizations, including the plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria, revealing its versatile presence across cellular compartments (Rojas-Rivera and Hetz, 2015). To investigate the subcellular localization of TMBIM-2, we employed transgenic animals expressing tmbim-2 fused with GFP under its native promoter. The functionality of TMBIM-2::GFP was validated through its ability to restore intestinal UPRmt activation in tmbim-2(yth57) mutants (Fig. S2, A and B). Our analysis revealed predominant expression of TMBIM-2::GFP within the nervous system, as indicated by the pan-neuronal rgef-1p::mCherry reporter, consistent with recent single-cell RNAseq analysis in C. elegans (Roux et al., 2023) (Fig. S2, C and D). In addition to the nervous system, we also observed TMBIM-2 expression in spermatheca and hypodermis (Fig. S2 C).

The expression and subcellular distribution of TMBIM-2 in response to neuronal mitochondrial stress. (A) Representative photomicrograph of dve-1 reporter in tmbim-2(yth57); neuronal Q40 overexpressing animals with or without TMBIM-2::GFP rescue. Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in A. n ≥ 12 worms. (C) The Dot plot shows the average expression of TMBIM-2 in kinds of C. elegans tissues. Expression values are from Roux et al. (2023). (D) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ythIs62[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::gfp] in combination with a pan-neuron marker rgef-1p::mcherry. Scale bar, 20 μm. Panels below show high-magnification views of boxed regions Zoom 1 (Head region), Zoom 2 (Spermatheca), and Zoom 3 (Tail region). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ythIs62[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::gfp] in combination with a neuronal mitochondria marker (forSi44[rgef-1p::tomm-20::mKate2::HA]). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the ROI is −0.05. (F) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ythIs62[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::gfp] in combination with the synaptic active zone marker (ythEX774[xbx-1p::mcherry::syd-1]). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the ROI is 0.63. (G) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (ythIs102[srh-142p::tmbim-2]) in combination with the trans-Golgi marker (TGN-38::mCherry). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. (H) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (ythIs102[srh-142p::tmbim-2]) in combination with the medial/cis-Golgi marker (AMAN-2::mCherry). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. ***P < 0.001 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM.

The expression and subcellular distribution of TMBIM-2 in response to neuronal mitochondrial stress. (A) Representative photomicrograph of dve-1 reporter in tmbim-2(yth57); neuronal Q40 overexpressing animals with or without TMBIM-2::GFP rescue. Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in A. n ≥ 12 worms. (C) The Dot plot shows the average expression of TMBIM-2 in kinds of C. elegans tissues. Expression values are from Roux et al. (2023). (D) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ythIs62[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::gfp] in combination with a pan-neuron marker rgef-1p::mcherry. Scale bar, 20 μm. Panels below show high-magnification views of boxed regions Zoom 1 (Head region), Zoom 2 (Spermatheca), and Zoom 3 (Tail region). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ythIs62[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::gfp] in combination with a neuronal mitochondria marker (forSi44[rgef-1p::tomm-20::mKate2::HA]). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the ROI is −0.05. (F) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ythIs62[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::gfp] in combination with the synaptic active zone marker (ythEX774[xbx-1p::mcherry::syd-1]). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the ROI is 0.63. (G) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (ythIs102[srh-142p::tmbim-2]) in combination with the trans-Golgi marker (TGN-38::mCherry). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. (H) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (ythIs102[srh-142p::tmbim-2]) in combination with the medial/cis-Golgi marker (AMAN-2::mCherry). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. ***P < 0.001 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM.

Notably, we observed an induction of tmbim-2 expression in response to neuronal mitochondrial stress, highlighting its dynamic regulation (Fig. 2, A–C). Next, we focused on the subcellular distribution of TMBIM-2 and noted its presence in the plasma membrane of neurons (Fig. 2 D). This plasma membrane localization was further validated through co-localization studied with DiD, a lipophilic dye marking the plasma membrane of ciliated sensory neurons (Fig. 2 D). We also confirmed that the localization of TMBIM-2::GFP is excluded from mitochondria in neurons (Fig. S2 E). Furthermore, we detected the presence of TMBIM-2::GFP throughout axons, with a pronounced enrichment at synapses, as evidenced by utilizing presynaptic reporter strain Scarlet::RAB-3 and mCherry::SYD-1 (Fig. 2 E and Fig. S2 F). Notably, under conditions of neuronal mitochondrial stresses, the expression of TMBIM-2 becomes pronounced in the region proximal to the plasma membrane and synapses (Fig. 2 F). To investigate the subcellular localization of TMBIM-2, we performed colocalization experiments. The results revealed that TMBIM-2 partially localizes to the Golgi apparatus (Fig. S2, G and H). These observations collectively suggest that disruptions in neuronal mitochondrial function result in the accumulation of TMBIM-2 along both the plasma membrane and synaptic sites.

The expression and subcellular distribution of TMBIM-2 in response to neuronal mitochondrial stress. (A) Quantification of tmbim-2 mRNA levels in young adult WT (yellow) and neuronal cox-5B knockdown (uthIs375[unc-119p::cox-5B HP; pRF(rol-6)]) (blue) animals. n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (B) Immunoblot of young adult TMBIM-2::GFP expression in WT and neuronal cox-5B knockdown animals. (C) Quantification of TMBIM-2::GFP protein levels as shown in B: WT (yellow) and neuronal cox-5B knockdown (blue) animals; n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (D) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ythEx572[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::gfp] in combination with a lipophilic plasma membrane dye DiD at the cell body. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the ROI is 0.94. (E) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with TMBIM-2 in combination with an ADF synaptic vesicle marker ythEx536[srh-142p::tmbim-2::gfp+srh-142p::Scarlet::rab-3]. The imaging used Z-stacks. Scale bar, 5 μm. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the ROI is 0.90. (F) Representative Single Slice-SIM photomicrographs of ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (ythIs102[srh-142p::tmbim-2::gfp]) animals with the presence or absence of neuronal cox-5B knockdown. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 10 μm. *P < 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

The expression and subcellular distribution of TMBIM-2 in response to neuronal mitochondrial stress. (A) Quantification of tmbim-2 mRNA levels in young adult WT (yellow) and neuronal cox-5B knockdown (uthIs375[unc-119p::cox-5B HP; pRF(rol-6)]) (blue) animals. n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (B) Immunoblot of young adult TMBIM-2::GFP expression in WT and neuronal cox-5B knockdown animals. (C) Quantification of TMBIM-2::GFP protein levels as shown in B: WT (yellow) and neuronal cox-5B knockdown (blue) animals; n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (D) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with ythEx572[tmbim-2p::tmbim-2::gfp] in combination with a lipophilic plasma membrane dye DiD at the cell body. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the ROI is 0.94. (E) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals with TMBIM-2 in combination with an ADF synaptic vesicle marker ythEx536[srh-142p::tmbim-2::gfp+srh-142p::Scarlet::rab-3]. The imaging used Z-stacks. Scale bar, 5 μm. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the ROI is 0.90. (F) Representative Single Slice-SIM photomicrographs of ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (ythIs102[srh-142p::tmbim-2::gfp]) animals with the presence or absence of neuronal cox-5B knockdown. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 10 μm. *P < 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

Neuronal mitochondrial perturbation triggers spatiotemporal dynamics of Ca2+ oscillations in a TMBIM-2-dependent manner

Given the predicted role of TMBIM family proteins in maintaining Ca2+ equilibrium within various compartmentalized organelles (Liu, 2017), we hypothesized that TMBIM-2 might play a crucial role in orchestrating the delicate balance of Ca2+ within the synapse of ADF neurons, thereby contributing to intricate stress signaling coordination. To test this hypothesis, we generated transgenic C. elegans lines expressing the well-established genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f (Chen et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2021a). By utilizing the xbx-1 promoter, we controlled the expression of various forms of GCaMP6f: a plasma membrane–targeted variant (PM-GCaMP6f) (Zhou et al., 2017), a cytosolic-targeted version (cyto-GCaMP6f) (Zhang et al., 2021a), and a mitochondria-targeted form (Mito-GCaMP6f) (Shen et al., 2014). Simultaneously, we employed the ADF neuron-specific srh-142 promoter to drive Scarlet::RAB-3 expression for labeling the synapses of ADF neurons. This approach enabled visualization of Ca2+ flux within distinct subcellular compartments within the synapse of ADF neurons (Fig. 3 A; and Fig. S3, A and B) (Shen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021a).

Neuronal mitochondrial perturbation triggers spatiotemporal dynamics of Ca 2+ waves in ADF synapses in a TMBIM-2-dependent manner. (A) Schematic drawing of ADF neurons and GCaMP6f imaging regions in B–L, and representation illustrating the principle behind the GCaMP6f. (B) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of plasma membrane Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f in the region of interest (ROI) shown in C of day 1 adult animals expressed neuronal PM-GCaMP6f and ADF presynaptic vesicle marker (ythEX762[xbx-1p::PM-GCaMP6f; srh-142p::Scarlet::rab-3+unc-119(+)]) with WT; neuronal cox-5B knockdown; tmbim-2(yth130); neuronal cox-5B knockdown+tmbim-2(yth130) background, respectively. The GCaMP6f signal was imaged for 60 s. (C) Representative confocal photomicrographs of animals in B. Presynaptic region of ADF neuron was marked with rab-3 (magenta). A–C stand for different points in time shown in B. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. (D) Quantification of the maximal ΔF/F0 with GCaMP6f signal in ROI shown in B. n ≥ 15 worms. (E) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in ROI shown in B. n ≥ 20 worms. (F) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f in the region of interest (ROI) shown in G of day 1 adult animals expressed neuronal mito-GCaMP6f and ADF presynaptic marker (ythEX761[xbx-1p::mtLS-GCaMP6f; srh-142p::Scarlet::rab-3+unc-119(+)]) with WT; neuronal cox-5B knockdown; tmbim-2(yth130); neuronal cox-5B knockdown+tmbim-2(yth130) background, respectively. The GCaMP6f signal was imaged for 120 s. (G) Representative confocal photomicrographs of animals in F. Presynaptic region of ADF neuron was marked with rab-3 (magenta). A–C stand for different points in time shown in F. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. (H) Quantification of the maximal ΔF/F0 with GCaMP6f signal in ROI shown in F. n ≥ 15 worms. (I) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f signal in ROI shown in F. n ≥ 20 worms. (J) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of cytosolic Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and neuronal cox-5B knockdown animals in the 60 s. (K) Representative confocal photomicrographs of animals in J. Presynaptic region of ADF neuron was marked with rab-3 (magenta). A–C stand for different points in time shown in J. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. (L) Quantification of the maximal ΔF/F0 with GCaMP6f signal in ROI shown in J. n ≥ 15 worms. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM.

Neuronal mitochondrial perturbation triggers spatiotemporal dynamics of Ca 2+ waves in ADF synapses in a TMBIM-2-dependent manner. (A) Schematic drawing of ADF neurons and GCaMP6f imaging regions in B–L, and representation illustrating the principle behind the GCaMP6f. (B) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of plasma membrane Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f in the region of interest (ROI) shown in C of day 1 adult animals expressed neuronal PM-GCaMP6f and ADF presynaptic vesicle marker (ythEX762[xbx-1p::PM-GCaMP6f; srh-142p::Scarlet::rab-3+unc-119(+)]) with WT; neuronal cox-5B knockdown; tmbim-2(yth130); neuronal cox-5B knockdown+tmbim-2(yth130) background, respectively. The GCaMP6f signal was imaged for 60 s. (C) Representative confocal photomicrographs of animals in B. Presynaptic region of ADF neuron was marked with rab-3 (magenta). A–C stand for different points in time shown in B. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. (D) Quantification of the maximal ΔF/F0 with GCaMP6f signal in ROI shown in B. n ≥ 15 worms. (E) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in ROI shown in B. n ≥ 20 worms. (F) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f in the region of interest (ROI) shown in G of day 1 adult animals expressed neuronal mito-GCaMP6f and ADF presynaptic marker (ythEX761[xbx-1p::mtLS-GCaMP6f; srh-142p::Scarlet::rab-3+unc-119(+)]) with WT; neuronal cox-5B knockdown; tmbim-2(yth130); neuronal cox-5B knockdown+tmbim-2(yth130) background, respectively. The GCaMP6f signal was imaged for 120 s. (G) Representative confocal photomicrographs of animals in F. Presynaptic region of ADF neuron was marked with rab-3 (magenta). A–C stand for different points in time shown in F. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. (H) Quantification of the maximal ΔF/F0 with GCaMP6f signal in ROI shown in F. n ≥ 15 worms. (I) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f signal in ROI shown in F. n ≥ 20 worms. (J) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of cytosolic Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and neuronal cox-5B knockdown animals in the 60 s. (K) Representative confocal photomicrographs of animals in J. Presynaptic region of ADF neuron was marked with rab-3 (magenta). A–C stand for different points in time shown in J. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 2 μm. (L) Quantification of the maximal ΔF/F0 with GCaMP6f signal in ROI shown in J. n ≥ 15 worms. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM.

Mitochondrial perturbation does not affect the dynamics of cytosol Ca 2+ waves in ADF synapses. (A) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals expressing neuronal PM-GCaMP6f in combination with ADF presynaptic vesicle marker (ythEX762[xbx-1p::PM-GCaMP6f; srh-142p:: Scarlet::rab-3+unc-119(+)]). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals expressing neuronal mito-GCaMP6f in combination with ADF presynaptic vesicle marker (ythEX761[xbx-1p::mtLS-GCaMP6f; srh-142p:: Scarlet::rab-3+unc-119(+)]). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals expressing neuronal PM-GCaMP6f with plasma membrane dye DiD. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 1 μm. (D) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals expressing neuronal mito-GCaMP6f in combination with neuronal mitochondria marker (forSi44[rgef-1p::tomm-20::mKate2::HA]). Scale bar, 1 μm. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 1 μm. (E) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of plasma membrane Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and egl-19(ad695) gain of function mutant animals in the 60 s. (F) Quantification of the amplitude of PM-GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and egl-19(ad695) animals. n ≥ 10 worms. (G) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and mcu-1(ju1154) mutant animals in the 60 s. (H) Quantification of the amplitude of mito-GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 13 worms. (I) Quantitative analysis of Ca2+ Fmin level by the PM-GCaMP6.0/RFP ratio with the presence or absence of neuronal cox-5B KD in WT (yellow) and tmbim-2 (blue) animals. n ≥ 12 worms. (J) Quantitative analysis of Ca2+ Fmin level by the Mito-GCaMP6.0/RFP ratio with the presence or absence of neuronal cox-5B KD in WT (yellow) and tmbim-2 (blue) animals. n ≥ 12 worms. (K) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of plasma membrane Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (ythIs102[srh-142p::tmbim-2]) animals in 60 s. (L) Quantification of the amplitude of PM-GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 animals. n ≥ 14 worms. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test in F, H, and L. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test in I and J (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Error bars, SEM.

Mitochondrial perturbation does not affect the dynamics of cytosol Ca 2+ waves in ADF synapses. (A) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals expressing neuronal PM-GCaMP6f in combination with ADF presynaptic vesicle marker (ythEX762[xbx-1p::PM-GCaMP6f; srh-142p:: Scarlet::rab-3+unc-119(+)]). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals expressing neuronal mito-GCaMP6f in combination with ADF presynaptic vesicle marker (ythEX761[xbx-1p::mtLS-GCaMP6f; srh-142p:: Scarlet::rab-3+unc-119(+)]). The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals expressing neuronal PM-GCaMP6f with plasma membrane dye DiD. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 1 μm. (D) Representative confocal photomicrographs of day 1 adult animals expressing neuronal mito-GCaMP6f in combination with neuronal mitochondria marker (forSi44[rgef-1p::tomm-20::mKate2::HA]). Scale bar, 1 μm. The imaging used Z-planes. Scale bar, 1 μm. (E) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of plasma membrane Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and egl-19(ad695) gain of function mutant animals in the 60 s. (F) Quantification of the amplitude of PM-GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and egl-19(ad695) animals. n ≥ 10 worms. (G) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and mcu-1(ju1154) mutant animals in the 60 s. (H) Quantification of the amplitude of mito-GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 13 worms. (I) Quantitative analysis of Ca2+ Fmin level by the PM-GCaMP6.0/RFP ratio with the presence or absence of neuronal cox-5B KD in WT (yellow) and tmbim-2 (blue) animals. n ≥ 12 worms. (J) Quantitative analysis of Ca2+ Fmin level by the Mito-GCaMP6.0/RFP ratio with the presence or absence of neuronal cox-5B KD in WT (yellow) and tmbim-2 (blue) animals. n ≥ 12 worms. (K) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of plasma membrane Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (ythIs102[srh-142p::tmbim-2]) animals in 60 s. (L) Quantification of the amplitude of PM-GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 animals. n ≥ 14 worms. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test in F, H, and L. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test in I and J (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Error bars, SEM.

We initially assessed the localization accuracy of PM-GCaMP6f and Mito-GCaMP6f through colocalization studies with corresponding compartmentalized markers. Our findings revealed that PM-GCaMP6f colocalized with the plasma membrane marker DiD, confirming its plasma membrane localization (Fig. S3 C). Furthermore, Mito-GCaMP6f was found to be enclosed by validated mitochondrial outer membrane reporters, confirming its mitochondrial localization (Fig. S3 D). Subsequently, we investigated the response of these GCaMP6f variants to specific genetic perturbations. We observed an increase in PM-GCaMP6f expression in egl-19(ad695 gf) mutants, a voltage-gated calcium channel (Fig. S3, E and F), while Mito-GCaMP6f levels significantly decreased in mcu-1(ju1154) mutants, a mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU; Fig. S3, G and H). These results indicate that GCaMP6f accurately localizes to subcellular compartments and serves as a reliable indicator of Ca2+ dynamics.

When monitoring the plasma membrane-tethered PM-GCaMP6f, worms with neuronal cox-5B KD exhibited substantial increases in both the amplitude and frequency of Ca2+ waves at synapses of ADF neurons (Fig. 3, B–E and Video 1). Subsequently, we observed a significant decrease in mitochondrial Ca2+ waves at synapses of ADF neurons in neuronal cox-5B KD worms compared with control animals, as monitored by Mito-GCaMP6f, consistent with the notion that mitochondrial function is disrupted in these animals (Fig. 3, F–I). Surprisingly, in contrast to the distinct dynamics observed with PM-GCaMP6f and Mito-GCaMP6f, we did not observe discernible differences in cytosolic GCaMP6f dynamics between control and neuronal cox-5B KD worms (Fig. 3, J–L), suggesting that the mild disruption of neuronal mitochondrial function did not substantially impact the overall cytosolic Ca2+ balance. One plausible explanation for this phenomenon is that calcium pumps swiftly export locally increased Ca2+ levels during mitochondrial stresses, thereby not changing the overall cytosolic Ca2+ balance. Additionally, the amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations in response to chronic neuronal mitochondrial stresses exhibited a gradual increase as worms grew, reaching their peak during young adulthood and Day 1, followed by a gradual decline with aging (Fig. 7 F). This pattern suggests that the ability of neurons to maintain Ca2+ homeostasis in response to chronic mitochondrial stresses declines with age.

Neuronal mitochondrial perturbation triggers plasma-membrane Ca2+oscillations within synapse of ADF neurons in a TMBIM-2-dependent manner. Representative fluorescence intensity images of PM-GCaMP6f (yellow) expressed ADF presynaptic vesicle marker (magenta) with WT; neuronal cox-5B knockdown; tmbim-2(yth130); neuronal cox-5B knockdown+tmbim-2(yth130) background, respectively. The PM-GCaMP6f fluorescence signal detected by confocal LSM980 with Airyscan 2 @10 Hz Multiplex SR-4Y Modes, related to Fig. 3, B–E. The GCaMP6f signal was imaged for 60 s. Scale bar: 2 μm. The video was recorded at 10 frames per second (fps). The playback speed is set to real-time, meaning that the video reflects the actual temporal dynamics of the Ca2+ oscillations observed in the experiment.

Neuronal mitochondrial perturbation triggers plasma-membrane Ca2+oscillations within synapse of ADF neurons in a TMBIM-2-dependent manner. Representative fluorescence intensity images of PM-GCaMP6f (yellow) expressed ADF presynaptic vesicle marker (magenta) with WT; neuronal cox-5B knockdown; tmbim-2(yth130); neuronal cox-5B knockdown+tmbim-2(yth130) background, respectively. The PM-GCaMP6f fluorescence signal detected by confocal LSM980 with Airyscan 2 @10 Hz Multiplex SR-4Y Modes, related to Fig. 3, B–E. The GCaMP6f signal was imaged for 60 s. Scale bar: 2 μm. The video was recorded at 10 frames per second (fps). The playback speed is set to real-time, meaning that the video reflects the actual temporal dynamics of the Ca2+ oscillations observed in the experiment.

Remarkably, the absence of tmbim-2 resulted in a significant reduction in both the amplitude and frequency of Ca2+ waves near the plasma membrane within the synapse of ADF neurons triggered by neuronal cox-5B KD, as monitored by PM-GCaMP6f (Fig. 3, B–E). However, the absence of tmbim-2 did not impact mitochondrial Ca2+ waves within the synapse of ADF neurons in neuronal cox-5B KD worms (Fig. 3, F–I). To investigate the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis by TMBIM-2, we assessed fluorescence minimum (Fmin) levels in ADF neurons of tmbim-2 mutants. Our findings revealed that tmbim-2 mutant worms exhibited significantly higher Fmin Ca2+ levels in neuronal cox-5B KD animals compared with WT control worms (Fig. S3 I). Additionally, mitochondrial Ca2+ levels remained unchanged in tmbim-2 mutant worms (Fig. S3 J). Overexpression of TMBIM-2 within ADF neurons did not significantly change plasma membrane Ca2+ waves within the synapse of ADF neurons (Fig. S3, K and L). These collective findings suggest that chronic perturbations in neuronal mitochondria trigger dynamic Ca2+ waves in proximity to the plasma membrane in a manner dependent on tmbim-2.

Loss of mcu-1 triggers plasma-membrane Ca2+ oscillations within synapses of ADF neurons and activates intestinal UPRmt

Mitochondrial perturbations that decrease mitochondrial membrane potential can lead to decreased ATP production and reduced mitochondrial calcium buffering capacity, thereby altering calcium dynamics near the plasma membrane within neurons (Giacomello et al., 2020). Calcium uptake by mitochondria is facilitated by the MCU, a highly selective and conductive calcium channel encoded by mcu-1 gene in C. elegans (Cao et al., 2017; Doser et al., 2024; Phillips et al., 2019). MCU-1 plays a critical role in calcium homeostasis, enabling dendritic mitochondria to uptake calcium (Ca2+), which in turn promotes the upregulation of mitoROS production. Moreover, mitochondria are positioned in close proximity to synaptic clusters of GLR-1, facilitating neuronal excitation by supporting calcium signaling and synaptic activity (Doser et al., 2024).

To investigate this, we observed the Ca2+ dynamics near the plasma membrane at the synapse of ADF neurons in mcu-1 mutant worms with defects in mitochondrial Ca2+ import. Intriguingly, mcu-1 mutants exhibited pronounced increases in the amplitude and frequency of PM-GCaMP6f Ca2+ waves (Fig. 4, A–C). Moreover, the mcu-1 mutants led to the induction of TMBIM-2 expression (Fig. 4 D). To explore the role of mcu-1 in ADF neurons for neuronal-to-intestinal UPRmt activation, we generated transgenic worms with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of mcu-1 in ADF neurons. We found that the mcu-1 knockout within ADF neurons resulted in the activation of intestinal UPRmt (Fig. 4, E–G; and Fig. S4, C and D), suggesting a direct link between neuronal mitochondrial calcium balance and the activation of intestinal UPRmt. We also observed that mcu-1 knockdown-triggered Ca2+ oscillations are also dependent on TMBIM-2 (Fig. S4, E and F). Additionally, overexpressing MCU-1 within neurons, aimed at enhancing mitochondrial calcium buffering capacity, attenuated UPRmt activation in neuronal Q40::YFP worms (Fig. S4, A and B). These findings highlight the pivotal role of mitochondrial calcium buffering capacity in shaping intracellular calcium signaling dynamics and orchestrating intertissue stress communication.

Loss of mcu-1 triggers plasma-membrane Ca2+oscillations within synapses of ADF neurons and activates intestinal UPRmt. (A) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of plasma membrane Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and mcu-1(ju1154) mutant animals in the 60 s. (B) Quantification of PM-GCaMP6 maximal fluorescence intensity changes in WT and mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 8 worms. (C) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 20 worms. (D) Representative confocal photomicrographs of TMBIM-2::GFP animals with the presence or absence of mcu-1(ju1154). The imaging used z-planes. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter expression in WT and ADF neuron mcu-1 knockdown animals (srh-142p::Cas9+u6p::mcu-1 sgRNA). Scale bar, 250 μm. (F) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm in E. n ≥ 12 worms. (G) Deletions of mcu-1 by CRISPR/Cas9 are detected by T7E1 assay. Representative DNA gels of T7E1 assay show mcu-1 PCR products amplified from genomic DNA of WT or srh-142p::Cas9+u6p::mcu-1-sg worms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

Loss of mcu-1 triggers plasma-membrane Ca2+oscillations within synapses of ADF neurons and activates intestinal UPRmt. (A) Representative fluorescence traces of average background-subtracted fluorescence intensity ΔF/F0 of plasma membrane Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f of WT and mcu-1(ju1154) mutant animals in the 60 s. (B) Quantification of PM-GCaMP6 maximal fluorescence intensity changes in WT and mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 8 worms. (C) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 20 worms. (D) Representative confocal photomicrographs of TMBIM-2::GFP animals with the presence or absence of mcu-1(ju1154). The imaging used z-planes. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter expression in WT and ADF neuron mcu-1 knockdown animals (srh-142p::Cas9+u6p::mcu-1 sgRNA). Scale bar, 250 μm. (F) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm in E. n ≥ 12 worms. (G) Deletions of mcu-1 by CRISPR/Cas9 are detected by T7E1 assay. Representative DNA gels of T7E1 assay show mcu-1 PCR products amplified from genomic DNA of WT or srh-142p::Cas9+u6p::mcu-1-sg worms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F4.

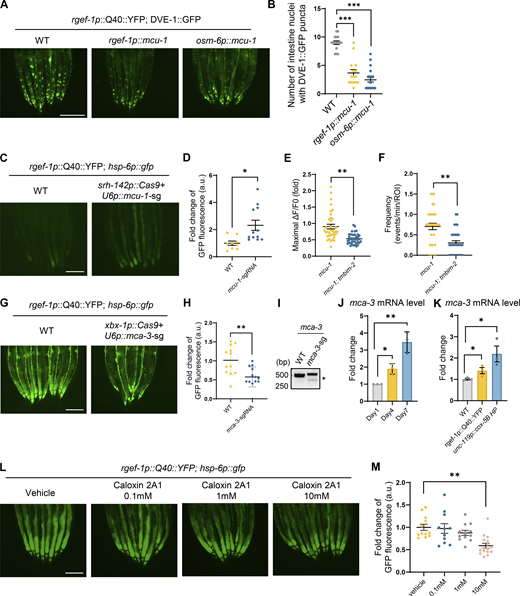

Overexpression of MCU-1 and loss of mca-3 in neurons partially suppresses neuronal-to-intestinal UPRmtactivation. (A) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter in WT; pan-neuron overexpressing MCU-1 (rgef-1p::mcu-1); ciliated-sensory neuron overexpressing MCU-1 (osm-6p::mcu-1) animals with neuronal Q40::YFP, respectively. Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of dve-1p::dve-1::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in A. n ≥ 15 worms. (C) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter in WT and ADF neuron mcu-1 knockdown animals (srh-142p::Cas9+u6p::mcu-1 sgRNA) with neuronal Q40::YFP, respectively. Scale bar, 250 μm. (D) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in C. n ≥ 15 worms. (E) Quantification of PM-GCaMP6 maximal fluorescence intensity changes in WT and tmbim-2; mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 20 worms. (F) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and tmbim-2; mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 20 worms. (G) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter in ciliated neuronal knockout of mca-3 with neuronal Q40::YFP worms. Scale bar, 250 μm. (H) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in G. n ≥ 15 worms. (I) Representative DNA gels of T7E1 assay identifying the PCR products amplified from genomic DNA of control worms or worms with mca-3 deletion in ciliated sensory neurons. (J) Quantification of mca-3 mRNA levels in day1 (grey), day4 (yellow) and day7 (blue) WT adult animals. n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (K) Quantification of mca-3 mRNA levels in WT (grey), neuronal overexpressing Q40 (yellow) and neuronal cox-5B knockdown (blue) animals. n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (L) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter in neuronal Q40::YFP animals with PMCA inhibitor Caloxin 2A1, respectively. Scale bar, 250 μm. (M) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in L. n ≥ 10 worms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Overexpression of MCU-1 and loss of mca-3 in neurons partially suppresses neuronal-to-intestinal UPRmtactivation. (A) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter in WT; pan-neuron overexpressing MCU-1 (rgef-1p::mcu-1); ciliated-sensory neuron overexpressing MCU-1 (osm-6p::mcu-1) animals with neuronal Q40::YFP, respectively. Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of dve-1p::dve-1::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in A. n ≥ 15 worms. (C) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter in WT and ADF neuron mcu-1 knockdown animals (srh-142p::Cas9+u6p::mcu-1 sgRNA) with neuronal Q40::YFP, respectively. Scale bar, 250 μm. (D) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in C. n ≥ 15 worms. (E) Quantification of PM-GCaMP6 maximal fluorescence intensity changes in WT and tmbim-2; mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 20 worms. (F) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in WT and tmbim-2; mcu-1(ju1154) animals. n ≥ 20 worms. (G) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter in ciliated neuronal knockout of mca-3 with neuronal Q40::YFP worms. Scale bar, 250 μm. (H) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in G. n ≥ 15 worms. (I) Representative DNA gels of T7E1 assay identifying the PCR products amplified from genomic DNA of control worms or worms with mca-3 deletion in ciliated sensory neurons. (J) Quantification of mca-3 mRNA levels in day1 (grey), day4 (yellow) and day7 (blue) WT adult animals. n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (K) Quantification of mca-3 mRNA levels in WT (grey), neuronal overexpressing Q40 (yellow) and neuronal cox-5B knockdown (blue) animals. n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. (L) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter in neuronal Q40::YFP animals with PMCA inhibitor Caloxin 2A1, respectively. Scale bar, 250 μm. (M) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression in the entire intestine of animals as depicted in L. n ≥ 10 worms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

TMBIM-2 acts with the calcium pump MCA-3 to mediate cell non-autonomous UPRmt activation

Despite the established role of TMBIM family proteins in maintaining Ca2+ equilibrium within cells (Liu, 2017), the molecular mechanism of TMBIM2 is unclear. To investigate the molecular function of TMBIM-2, we performed immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments on C. elegans expressing TMBIM-2::GFP, followed by mass spectrometry (MS) to identify TMBIM-2 interaction partners (Fig. 5 A and Table S4). These experiments yielded a variety of membrane-associated proteins. Gene Ontology (GO) analyses of these genes (score >10) highlighted pathways including intracellular protein transport, protein N-linked glycosylation, vesicle docking involved in exocytosis, and notably, calcium ion transport. Among these candidates, calcium ion transport emerged as significantly enriched, with MCA-3 topping the list (Fig. 5 B).

TMBIM-2 acts with the calcium pump MCA-3 in regulating cell non-autonomous UPRmtactivation. (A) Workflow of the IP-MS method in expression TMBIM-2::GFP C. elegans. (B) List of TMBIM-2–interacting proteins that top 10 candidates identified by IP-MS experiments. (C) Interactions of TMBIM-2 with MCA-3. HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated cDNAs and followed by the indicated immunoprecipitations. (D) Representative photomicrographs of ciliated neuronal knockout of mca-3 in neuronal Q40::YFP, dve-1p::dve-1::gfp worms. Scale bar, 250 μm. (E) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in D. n ≥ 15 worms. (F) Fluorescence images of neurons in strains expressing TMBIM-2::GFP with the presence or absence of ciliated neuronal knockout of mca-3. Scale bar = 2 μm. (G) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1p::dve-1::gfp reporter in neuronal Q40::YFP animals with PMCA inhibitor Caloxin 2A1, respectively. Scale bar, 250 μm. (H) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in G. n ≥ 10 worms. (I) Quantification of PM-GCaMP6 maximal fluorescence intensity changes in animals with a vehicle and 10 mM Caloxin 2A1. n ≥ 20 worms. (J) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in animals with a vehicle and 10 mM Caloxin 2A1. n ≥ 20 worms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

TMBIM-2 acts with the calcium pump MCA-3 in regulating cell non-autonomous UPRmtactivation. (A) Workflow of the IP-MS method in expression TMBIM-2::GFP C. elegans. (B) List of TMBIM-2–interacting proteins that top 10 candidates identified by IP-MS experiments. (C) Interactions of TMBIM-2 with MCA-3. HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated cDNAs and followed by the indicated immunoprecipitations. (D) Representative photomicrographs of ciliated neuronal knockout of mca-3 in neuronal Q40::YFP, dve-1p::dve-1::gfp worms. Scale bar, 250 μm. (E) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in D. n ≥ 15 worms. (F) Fluorescence images of neurons in strains expressing TMBIM-2::GFP with the presence or absence of ciliated neuronal knockout of mca-3. Scale bar = 2 μm. (G) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1p::dve-1::gfp reporter in neuronal Q40::YFP animals with PMCA inhibitor Caloxin 2A1, respectively. Scale bar, 250 μm. (H) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in G. n ≥ 10 worms. (I) Quantification of PM-GCaMP6 maximal fluorescence intensity changes in animals with a vehicle and 10 mM Caloxin 2A1. n ≥ 20 worms. (J) Quantification of the frequency with GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity changes in animals with a vehicle and 10 mM Caloxin 2A1. n ≥ 20 worms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

MCA-3 shares homology with a plasma-membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) that employs ATP hydrolysis to transport Ca2+ from the cytosol to extracellular spaces (Brini and Carafoli, 2011). Elevated Ca2+ levels within neurons give rise to a range of detrimental consequences, including compromised synaptic plasticity, excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis (Berliocchi et al., 2005). To counteract increased Ca2+ levels, neurons employ a multifaceted approach involving pumps, transporters, cytoplasmic calcium-binding proteins, and buffering by mitochondria (Berridge et al., 2003; Devine and Kittler, 2018; Nanou and Catterall, 2018). To explore the potential interactions between TMBIM-2 and MCA-3, we conducted co-immunoprecipitation experiments using HEK293T cells overexpressing C. elegans TMBIM-2::GFP and MCA-3::HA. Our results showed an interaction between TMBIM-2 and MCA-3 (Fig. 5 C).

We generated tissue-specific mca-3 knockdown mutants using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Remarkably, the knockdown of mca-3 specifically in ciliated sensory neurons, robustly suppressed intestinal UPRmt activation in animals expressing neuronal Q40::YFP (Fig. 5, D and E; and Fig. S4, G–I). It was noted that the loss of mca-3 also attenuated the enrichment of TMBIM-2::GFP on the plasma membrane (Fig. 5 F), suggesting a dependency of MCA-3 and calcium balance on the subcellular localization of TMBIM-2. We found that the expression of mca-3 significantly increased with aging and the expression of mca-3 also significantly increased under neuronal mitochondrial stress (Fig. S4, J and K).

Having established that genetic ablation of mca-3 suppressed intestinal UPRmt activation, we further investigated whether pharmacological inhibition of MCA-3 could result in a similar phenotype. We performed experiments using Caloxin 2A1, a specific inhibitor of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA). Caloxin 2A1 selectively inhibits the Ca2+-Mg2+–ATPase activity of PMCA without affecting other ATPase, such as Mg2+-ATPase or Na+-K+–ATPase and has been well-characterized in prior studies (Chaudhary et al., 2001; Holmes et al., 2003; Pande et al., 2005, 2008; Szewczyk et al., 2010). Treatment with 10 mM Caloxin 2A1 markedly suppressed intestinal UPRmt activation (Fig. 5, G and H; and Fig. S4, L and M). Additionally, we observed a significant reduction in both the amplitude and frequency of Ca2+ waves near the plasma membrane at ADF neuron synapses (Fig. 5, I and J). These results indicate that TMBIM-2 couples with MCA-3 to mediate Ca2+ homeostasis and cell non-autonomous UPRmt in response to mitochondrial perturbations within neurons.

Serotonin supplementation restored the systemic UPRmt activation in tmbim-2 mutants

Ca2+ emerges as a pivotal universal intracellular signaling messenger, intricately regulating vital cellular functions such as cell death, gene transcription, exocytosis, and neuronal transmission (Berridge et al., 2003; Berridge et al., 2000; Carafoli et al., 2001; Pang and Südhof, 2010). By introducing tetanus toxin (TeTx) into neurons—a neurotoxin that inhibits Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release (Hendricks et al., 2012), we found that the induction of TeTx in ADF serotoninergic neurons strongly attenuated the intestinal UPRmt activation in animals expressing neuronal cox-5B KD or neuronal Q40::YFP expression (Fig. 6, A, B, E, and F; and Fig. S5, A–C), suggesting Ca2+-dependent neurotransmission is required for orchestrating systemic mitochondrial stress communication.

Supplementation of serotonin restored the neuronal-to-intestinal UPR mt activation in tmbim-2 mutants. (A) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter in animals expressing neuronal Q40 and neurotoxin TeTx in ADF neuron (ythEx768[srh-142p::TeTx::sl2::mcherry]). Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in A. n ≥ 15 worms. (C) Representative photomicrographs of the ADF neurotransmitter exocytosis reporter (ythEX766[srh-142p-SYP-Phluorin+unc-119(+)]) in control or neuronal cox-5B knockdown animals in WT or tmbim-2(yth130) background. The imaging used Z-stacks. Scale bar, 2 μm. (D) Quantification of srh-142p::snb-1::pHluorin fluorescence in the neurons of animals as depicted in C: WT (orange); tmbim-2(yth130) (yellow); unc-119p::cox-5B HP (ultramarine); unc-119p::cox-5B; tmbim-2(yth130) (wathet). n ≥ 12 worms. (E) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter expression in WT (a); neuronal cox-5B knockdown (b); neuronal cox-5B knockdown; tmbim-2(c); neuronal cox-5B knockdown; or ADF neuron overexpressing TeTx(ythEX768[srh-142p::TeTx::sl2::mCherry+unc-119(+)];unc-119(ed-3)III) (d) animals treated with vehicle control or 50 mM serotonin (5-HT). (F) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in E, yellow for control and blue for feeding 5-HT. n ≥ 12 worms. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (G) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter in control or ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 animals in WT or tph-1(n4622) background. (H) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in G. n ≥ 15 worms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM; Scale bar, 250 μm.

Supplementation of serotonin restored the neuronal-to-intestinal UPR mt activation in tmbim-2 mutants. (A) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter in animals expressing neuronal Q40 and neurotoxin TeTx in ADF neuron (ythEx768[srh-142p::TeTx::sl2::mcherry]). Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in A. n ≥ 15 worms. (C) Representative photomicrographs of the ADF neurotransmitter exocytosis reporter (ythEX766[srh-142p-SYP-Phluorin+unc-119(+)]) in control or neuronal cox-5B knockdown animals in WT or tmbim-2(yth130) background. The imaging used Z-stacks. Scale bar, 2 μm. (D) Quantification of srh-142p::snb-1::pHluorin fluorescence in the neurons of animals as depicted in C: WT (orange); tmbim-2(yth130) (yellow); unc-119p::cox-5B HP (ultramarine); unc-119p::cox-5B; tmbim-2(yth130) (wathet). n ≥ 12 worms. (E) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter expression in WT (a); neuronal cox-5B knockdown (b); neuronal cox-5B knockdown; tmbim-2(c); neuronal cox-5B knockdown; or ADF neuron overexpressing TeTx(ythEX768[srh-142p::TeTx::sl2::mCherry+unc-119(+)];unc-119(ed-3)III) (d) animals treated with vehicle control or 50 mM serotonin (5-HT). (F) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in E, yellow for control and blue for feeding 5-HT. n ≥ 12 worms. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (G) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter in control or ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 animals in WT or tph-1(n4622) background. (H) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in G. n ≥ 15 worms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars, SEM; Scale bar, 250 μm.

Supplementation of serotonin restored the systemic UPR mt activation in tmbim-2 mutants. (A) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter in animals expressing neuronal Q40 and neurotoxin TeTx in ciliated sensory neurons (ythEx488[xbx-1p::TeTx::sl2::mcherry]). Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in A. n ≥ 15 worms. (C) Representative photomicrographs of the ADF neurotransmitter exocytosis reporter (ythEX766[srh-142p-SYP-Phluorin+unc-119(+)]) in control and srh-142p::TeTx::SL2::mCherry expressing animals. For the control group, mCherry channel image was not acquired (N/A) due to the absence of mCherry expression. The imaging used Z-stacks. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter (zcIs3[hsp-6p::gfp]) expression in animals treated with vehicle control or 50 mM serotonin (5-HT). (E) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression. The genotypes are as in D. n ≥ 15 worms. (F) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter expression in rgef-1p::Q40::yfp; tmbim-2(yth26) animals treated with vehicle control or 50 mM 5-HT. (G) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression. The genotypes are as in F. n ≥ 15 worms. (H) Representative TEM images of synaptic profiles, including WT, tmbim-2(yth57), and tmbim-2(yth26). Arrows indicate active zone; Scale bar, 200 nm. (I) Quantification of the number of synaptic vesicles at the active zone as shown in H. n ≥ 5 worms. (J) Quantification of the size of synaptic vesicles at the active zone as shown in H. n ≥ 5 worms. (K) Dot plot shows the average expression of Tmbim2 in 17 mouse organs or tissue at the age of 3 mo. WBC, white blood cells; BAT, brown adipose tissue; SCAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; GAT, gonadal adipose tissue; MAT, mesenteric adipose tissue. (L) Representative confocal photomicrograph of animals spermatheca expressing TMBIM-2 at different ages. The imaging used z-planes. Scale bar, 20 μm. (M) Quantitative analysis of TMBIM-2::GFP protein levels in ROI shown in L. n ≥ 8 worms. (N) Survival analysis of WT (blue) and tmbim-2 (yth26) (yellow); n ≥ 80 worms. (O) Survival analysis of control (blue) and ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (yellow); n ≥ 80 worms. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. In N and O, we used The Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test for statistical analysis. Error bars, SEM.

Supplementation of serotonin restored the systemic UPR mt activation in tmbim-2 mutants. (A) Representative photomicrographs of dve-1 reporter in animals expressing neuronal Q40 and neurotoxin TeTx in ciliated sensory neurons (ythEx488[xbx-1p::TeTx::sl2::mcherry]). Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of the number of intestinal nuclei puncta with GFP signal per worm as shown in A. n ≥ 15 worms. (C) Representative photomicrographs of the ADF neurotransmitter exocytosis reporter (ythEX766[srh-142p-SYP-Phluorin+unc-119(+)]) in control and srh-142p::TeTx::SL2::mCherry expressing animals. For the control group, mCherry channel image was not acquired (N/A) due to the absence of mCherry expression. The imaging used Z-stacks. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter (zcIs3[hsp-6p::gfp]) expression in animals treated with vehicle control or 50 mM serotonin (5-HT). (E) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression. The genotypes are as in D. n ≥ 15 worms. (F) Representative photomicrographs of hsp-6 reporter expression in rgef-1p::Q40::yfp; tmbim-2(yth26) animals treated with vehicle control or 50 mM 5-HT. (G) Quantification of hsp-6p::gfp expression. The genotypes are as in F. n ≥ 15 worms. (H) Representative TEM images of synaptic profiles, including WT, tmbim-2(yth57), and tmbim-2(yth26). Arrows indicate active zone; Scale bar, 200 nm. (I) Quantification of the number of synaptic vesicles at the active zone as shown in H. n ≥ 5 worms. (J) Quantification of the size of synaptic vesicles at the active zone as shown in H. n ≥ 5 worms. (K) Dot plot shows the average expression of Tmbim2 in 17 mouse organs or tissue at the age of 3 mo. WBC, white blood cells; BAT, brown adipose tissue; SCAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; GAT, gonadal adipose tissue; MAT, mesenteric adipose tissue. (L) Representative confocal photomicrograph of animals spermatheca expressing TMBIM-2 at different ages. The imaging used z-planes. Scale bar, 20 μm. (M) Quantitative analysis of TMBIM-2::GFP protein levels in ROI shown in L. n ≥ 8 worms. (N) Survival analysis of WT (blue) and tmbim-2 (yth26) (yellow); n ≥ 80 worms. (O) Survival analysis of control (blue) and ADF neuron overexpressing TMBIM-2 (yellow); n ≥ 80 worms. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, ns denotes P > 0.05 via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. In N and O, we used The Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test for statistical analysis. Error bars, SEM.

To further explore the neurotransmission under neuronal mitochondrial stress, we used an srh-142 promoter to drive SNB-1::pHluorin (SpH) expression in the ADF neuron for optical measurements of presynaptic activity, which has been previously validated in C. elegans (Han et al., 2017). SNB-1 is an ortholog of human vesicle–associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2). SNB-1 enables SNAP receptor activity and syntaxin binding activity to mediate chemical synaptic transmission located in the presynaptic active zone. This method involves the quenching of SpH fluorescence in synaptic vesicles (SVs) due to their low/acidic luminal pH. Upon stimulation, neurotransmitter vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane, exposing them to the neutral pH of the extracellular medium, leading to an increase in SpH fluorescence. Notably, under neuronal mitochondrial stress, the fluorescence intensity of SpH increased, indicating enhanced neurotransmitter release (Fig. 6, C and D). Loss of tmbim-2 significantly suppressed the increase in SpH fluorescence in neuronal cox-5B KD worms (Fig. 6, C and D).

Intriguingly, the addition of serotonin effectively restored systemic UPRmt activation in tmbim-2 mutants as well as in worms expressing TeTx in ADF neurons, in response to neuronal cox-5B KD or neuronal Q40::YFP expression (Fig. 6, E and F; and Fig. S5, D–G). Moreover, the expression of tmbim-2 solely within two ADF sensory neurons was sufficient to induce UPRmt in the intestine (Fig. 6, G and H). This process was dependent upon tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH-1), an enzyme responsible for serotonin synthesis (Sze et al., 2000) (Fig. 6, G and H). Furthermore, electron micrograph ultrastructural analyses revealed that tmbim-2 mutants exhibited a significant increase in the number of synaptic vesicles at active zones of neurons (Fig. S5, H and I), while the vesicle diameter remained comparable to that of WT worms (Fig. S5, H and J). These findings suggest that TMBIM-2 plays a crucial role in facilitating serotonin release from ADF neurons, thereby enhancing neuronal-to-intestinal mitochondrial stress communication.

Overexpression of TMBIM-2 preserves age-onset decline of aversive learning and extends the lifespan of C. elegans

As organisms age, their ability to respond to stress gradually declines. To investigate the role of TMBIM-2 in the aging process, we analyzed published gene expression datasets, revealing a decline in Tmbim2 expression in the brain with aging (Schaum et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2013). This pattern mirrored observations in the single-cell atlas study of aging C. elegans, where tmbim-2 mRNA levels decreased in ADF neurons (Fig. 7, A–C and Fig. S5 K). Additionally, the TMBIM-2::GFP protein level in the nervous system and spermatheca of Day 5 worms both exhibited a significant decrease compared with Day 1 worms (Fig. 7, D and E; and Fig. S5, L and M). This decline in TMBIM-2 protein levels during aging is consistent with the gradual decrease in Ca2+ oscillations in response to prolonged neuronal mitochondrial stresses (Fig. 7 F).