Endocytosis, required for the uptake of receptors and their ligands, can also introduce pathological aggregates such as α-synuclein (α-syn) in Parkinson’s Disease. We show here the unexpected presence of intrinsically perforated endolysosomes in neurons, suggesting involvement in the genesis of toxic α-syn aggregates induced by internalized preformed fibrils (PFFs). Aggregation of endogenous α-syn in late endosomes and lysosomes of human iPSC-derived neurons (iNs), seeded by internalized α-syn PFFs, caused the death of the iNs but not of the parental iPSCs and non-neuronal cells. Live-cell imaging of iNs showed constitutive perforations in ∼5% of their endolysosomes. These perforations, identified by 3D electron microscopy in iNs and CA1 pyramidal neurons and absent in non-neuronal cells, may facilitate cytosolic access of endogenous α-syn to PFFs in the lumen of endolysosomes, triggering aggregation. Inhibiting the PIKfyve phosphoinositol kinase reduced α-syn aggregation and associated iN death, even with ongoing PFF endolysosomal entry, suggesting that maintaining endolysosomal integrity might afford a therapeutic strategy to counteract synucleinopathies.

Introduction

The endocytic pathway is a vital route for molecular uptake into cells. It is also a potential entryway for pathology-inducing cargo, as illustrated by the cell-to-cell transmission of cytotoxic aggregates such as α-synuclein (α-syn) in Parkinson’s Disease (PD). Hallmarks of PD, which affects ∼10 million individuals worldwide (Lashuel et al., 2013), are Lewy bodies, intracellular inclusions composed largely of α-syn aggregates, and fragmented membranes; α-syn also has an important role in normal synaptic function, probably by influencing synaptic vesicle trafficking (Iwai et al., 1995; Jakes et al., 1994; Courte et al., 2020).

α-syn, a 14-kDa neuronal protein, constitutes ∼1% of cytosolic proteins in neurons (Stefanis, 2012). In its native state, α-syn is an unstructured monomer that can adopt an α-helical conformation upon interacting with phospholipids (Bartels et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Burré et al., 2013; Breydo et al., 2012; Theillet et al., 2016; Rovere et al., 2018; Galvagnion et al., 2015; Weinreb et al., 1996; Eliezer et al., 2001; Kramer and Schulz-Schaeffer, 2007). Under pathological conditions, however, α-syn forms cross β-sheet-rich amyloid fibrils that contribute to neurotoxicity (Conway et al., 2001). The transition of α-syn from a soluble, unfolded polypeptide to insoluble fibrillar aggregates is a critical aspect of PD pathogenesis. This process follows a nucleation-polymerization mechanism, in which preformed oligomers seed assembly of fibrillar structures, resulting in the formation of Lewy bodies (Weinreb et al., 1996; Fauvet et al., 2012; Suzuki et al., 2018; Kramer and Schulz-Schaeffer, 2007; Desplats et al., 2009; Baba et al., 1998; Danzer et al., 2007).

In vitro studies using various central nervous system–derived models and in vivo experiments using brain tissues have contributed substantially to our understanding of α-syn pathology in PD (Luk et al., 2009, 2012; Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2011; Luna et al., 2018; Dryanovski et al., 2013; Masuda-Suzukake et al., 2013; Paumier et al., 2015; Desplats et al., 2009; Recasens et al., 2018; Nonaka et al., 2010; Redmann et al., 2017). These investigations have shown that α-syn aggregates disseminate in a “prion-like” fashion, propagating from one cell to another. Thus, when neurons expressing wild-type α-syn are exposed to pre-formed fibrils (PFFs) of α-syn, these fibrils seed intracellular formation of α-syn aggregates, which damage the affected neurons.

α-syn aggregates that form in cells upon incubation with PFFs localize predominantly within lysosomes (Bayati et al., 2022; Domert et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2022; Karpowicz et al., 2017; Konno et al., 2012). Freeman and colleagues (Freeman et al., 2013) proposed that this mechanism requires disruption of the lysosomal membrane, which they suggested would be caused by the internalized PFFs themselves. Others have proposed that in neuronal tissues, cell-to-cell propagation of α-syn aggregates might occur by transfer within lysosomes from donor cells to recipient cells through tunneling nanotubes (Dilsizoglu Senol et al., 2021; Abounit et al., 2016).

While PFF-mediated aggregation of α-syn is typically observed in neuronal cells, it can also occur in non-neuronal cells. For instance, human HEK293T cells ectopically expressing wild-type α-syn can form aggregates when PFFs are introduced by protein transfection, e.g., by Lipofectamine (Woerman et al., 2015). A genome-wide CRISPR interference screen in HEK293T cells showed that depletion of 1-phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase containing an FYVE-type zinc finger (PIKfyve) reduces this α-syn aggregation (See et al., 2021, Preprint). PIKfyve, a 240-kDa class III lipid kinase located on endosomal membranes, has a critical function in endolysosomal trafficking and autophagy (Bissig et al., 2017; Rutherford et al., 2006; de Lartigue et al., 2009; Sharma et al., 2019; Karabiyik et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2014). Inhibition of PIKfyve, either genetically or pharmacologically, depletes endolysosomal PI(5)P and PI(3,5)P2 phosphoinositides and leads to enlarged endolysosomes, disrupted fission, and impaired formation of autophagolysosomes (Karabiyik et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2019; Choy et al., 2018; McCartney et al., 2014; Krishna et al., 2016; De Leo et al., 2021). See and colleagues (See et al., 2021, Preprint) suggested that inhibiting the transport of PFFs from endosomes to lysosomes by lowering PIKfyve activity would reduce lysosomal damage and that the reduced release of PFFs into the cytosol would prevent seeding of cytosolic α-syn aggregates. Others have proposed that pharmacological inhibition of PIKfyve might instead reduce lysosomal PFF content by increased endolysosomal fusion with the plasma membrane and consequent exocytic release of PFFs into the medium (Hung et al., 2023).

In the work reported here, we re-examined these questions with an experimental approach that avoided non-physiological protein transfection. We used human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived neurons (iNs), in which α-syn aggregates accumulated in late endosomes and lysosomes, seeded by wild-type α-syn PFFs internalized from the medium. In the absence of exposure to PFFs, we found that a small but significant proportion of late endosomes and lysosomes were inherently perforated (“leaky”) within the soma but not in the neurites of iNs; incubation with PFFs did not exacerbate this damage. We detected these perforated late endosomes and lysosomes by live-cell fluorescence microscopy, using biosensors designed to detect continuity with the cytosol. Volumetric high-resolution images acquired using focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) corroborated these observations, both in iNs and in CA1 pyramidal neurons from mouse brain. In contrast, endolysosomes in parental iPSCs and other non-neuronal cells, whether in tissue culture or in the liver, appeared structurally intact, in agreement with current understanding.

Acute pharmacological inhibition of PIKfyve activity in iNs with Apilimod or Vacuolin-1 reduced the damage detected in late endosomes and lysosomes, prevented the PFF-mediated aggregation of cytosolic α-syn induced by PFF exposure, and substantially lowered neurotoxicity and associated neuronal cell death. These findings suggest that targeting PIKfyve activity might represent a viable therapeutic strategy for preventing and treating synucleinopathies. This approach would offer a way to mitigate the progression of these neurodegenerative disorders by addressing a fundamental aspect of their cellular pathology.

Results

Incubation of iNs with PFFs causes the formation of α-syn-YFP aggregates

As a tissue-culture model resembling the early stages in the synucleinopathy of Parkinson’s disease, we used human iNs. We could induce formation of α-syn aggregates in these cells from ectopically, transiently expressed, cytosolic α-syn fused to YFP (α-syn-YFP) by incubating them for 3 days with 4 µg/ml (∼ 0.3 µM) PFFs produced from recombinant wild-type α-syn expressed in Escherichia coli (Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2014; Gribaudo et al., 2019). The iNs were generated by differentiation from iPSCs in response to the expression of the neuronal transcription factor NGN2 (Zhang et al., 2013; Lagomarsino et al., 2021). Inspection of the iNs 14–21 days after onset of differentiation showed the appearance of neurites emanating from the soma and expression of the neuronal marker MAP2 (detected by immunofluorescence; Fig. 1 A); neurites and MAP2 were absent in the parental iPSCs (Fig. 1 B).

α-syn-YFP aggregation in iNs exposed to PFFs . (A and B) Immunofluorescence images obtained using spinning disc confocal microscopy depict maximum z-projections made from consecutive optical planes spaced 270 nm apart of chemically fixed parental iPSCs (A) and iNs (B) treated with MAP2-specific antibody for neuronal identification. Cell perimeters in B are outlined with white dotted lines. Images are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 40 µm. (C–E) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP display a diffuse cytoplasmic distribution of α-syn-YFP without PFF treatment (C), compared to distinct α-syn-YFP aggregates mostly in soma and fewer in neurites after 3 days of incubation with 4 µg/ml (∼0.3 µM) PFFs (D). Live-cell spinning-disc confocal microscopy images depict maximum z-projections and are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 2× magnification. Bar graph in E quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates for the specified number of cells; each dot represents data from each replicate. (F–H) iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP, when incubated without (F) and with (G) 4 µg/ml PFFs for 3 days, show puncta consistent with α-syn-YFP aggregates. Live-cell spinning-disc confocal microscopy images depict maximum z-projections and are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets offer 2× magnification. Bar graph in H quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates; each dot represents data from a biological replicate. (I–K) iPSCs stably expressing α-syn-YFP exhibit a diffuse cytosolic α-syn-YFP signal in the absence (I) or after a 3-day incubation with 4 µg/ml PFFs (J). Live-cell spinning-disc confocal microscopy images depict maximum z-projections and are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 2× magnification. Bar graph in K quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates for the specified number of cells; each dot represents data from each replicate. (L–N) SVG-A cells stably expressing α-syn-YFP show diffuse cytoplasmic α-syn-YFP signal in (L) the absence of or (M) after a 3-day incubation with 4 µg/ml PFFs. Live-cell spinning-disc confocal microscopy images depict maximum z-projections and are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 2× magnification. Bar graph in N quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates for the specified number of cells; each dot represents data from each replicate. Statistical significance (P < 0.005) is indicated by a star; “ns” denotes no statistical difference.

α-syn-YFP aggregation in iNs exposed to PFFs . (A and B) Immunofluorescence images obtained using spinning disc confocal microscopy depict maximum z-projections made from consecutive optical planes spaced 270 nm apart of chemically fixed parental iPSCs (A) and iNs (B) treated with MAP2-specific antibody for neuronal identification. Cell perimeters in B are outlined with white dotted lines. Images are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 40 µm. (C–E) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP display a diffuse cytoplasmic distribution of α-syn-YFP without PFF treatment (C), compared to distinct α-syn-YFP aggregates mostly in soma and fewer in neurites after 3 days of incubation with 4 µg/ml (∼0.3 µM) PFFs (D). Live-cell spinning-disc confocal microscopy images depict maximum z-projections and are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 2× magnification. Bar graph in E quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates for the specified number of cells; each dot represents data from each replicate. (F–H) iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP, when incubated without (F) and with (G) 4 µg/ml PFFs for 3 days, show puncta consistent with α-syn-YFP aggregates. Live-cell spinning-disc confocal microscopy images depict maximum z-projections and are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets offer 2× magnification. Bar graph in H quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates; each dot represents data from a biological replicate. (I–K) iPSCs stably expressing α-syn-YFP exhibit a diffuse cytosolic α-syn-YFP signal in the absence (I) or after a 3-day incubation with 4 µg/ml PFFs (J). Live-cell spinning-disc confocal microscopy images depict maximum z-projections and are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 2× magnification. Bar graph in K quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates for the specified number of cells; each dot represents data from each replicate. (L–N) SVG-A cells stably expressing α-syn-YFP show diffuse cytoplasmic α-syn-YFP signal in (L) the absence of or (M) after a 3-day incubation with 4 µg/ml PFFs. Live-cell spinning-disc confocal microscopy images depict maximum z-projections and are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 2× magnification. Bar graph in N quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates for the specified number of cells; each dot represents data from each replicate. Statistical significance (P < 0.005) is indicated by a star; “ns” denotes no statistical difference.

Ectopic expression of α-syn-YFP in iNs yielded a diffuse, cytosolic fluorescent signal (Fig. 1, C and E), a distribution expected for soluble cytosolic α-syn-YFP, also observed when stably expressed in immortalized astroglia-derived simian virus 40 transformed glial (SVG-A) cells (Fig. 1 L). This diffuse distribution has also been observed in other non-neuronal cell types (Vasili et al., 2022; Furlong et al., 2000; Fortin et al., 2005; Imberdis et al., 2019). Continuous 3-day incubation of iNs with PFFs resulted in the appearance of α-syn-YFP fluorescent spots, indicating the formation of α-syn-YFP aggregates, primarily in somas and less frequently in neurites (Fig. 1, D and E). In contrast, similarly treated SVG-A cells showed only a cytosolic α-syn-YFP signal (Fig. 1, M and N), despite expressing higher levels of α-syn-YFP (Fig. S1), ruling out the possibility that aggregation was directly related to expression levels.

Expression levels of α-syn-YFP do not correlate with PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP aggregate formation (associated with Figs. 1,and2 ). α-syn-YFP expression levels do not predict PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP aggregation. F.I., fluorescence intensity. Bar graphs show relative α-syn-YFP expression per cell, calculated by summing total fluorescence across sequential z-planes (spaced 270 nm apart) after background subtraction, acquired under identical live-cell fluorescence spinning disc confocal microscopy conditions. Analysis includes iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP as well as iPSCs and SVG-A cells with stable α-syn-YFP expression; each dot represents a single cell. Horizontal bar denotes median value. Cells were preincubated with 4 µg/ml PFFs for 3 days before imaging. Aggregation was quantified as the percentage of cells containing PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP spots. The number of cells analyzed is indicated.

Expression levels of α-syn-YFP do not correlate with PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP aggregate formation (associated with Figs. 1,and2 ). α-syn-YFP expression levels do not predict PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP aggregation. F.I., fluorescence intensity. Bar graphs show relative α-syn-YFP expression per cell, calculated by summing total fluorescence across sequential z-planes (spaced 270 nm apart) after background subtraction, acquired under identical live-cell fluorescence spinning disc confocal microscopy conditions. Analysis includes iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP as well as iPSCs and SVG-A cells with stable α-syn-YFP expression; each dot represents a single cell. Horizontal bar denotes median value. Cells were preincubated with 4 µg/ml PFFs for 3 days before imaging. Aggregation was quantified as the percentage of cells containing PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP spots. The number of cells analyzed is indicated.

Equivalent experiments with undifferentiated parental iPSCs were not feasible because iPSCs were not amenable to transient α-syn-YFP expression with our transfection protocol. Instead, using iPSCs harboring wild-type α-syn-YFP stably expressed by lentiviral transduction, we detected only diffuse cytosolic α-syn-YFP, regardless of whether they had been incubated for 3 days with PFFs (Fig. 1, I–K). In contrast, iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP imaged 5–14 days after the onset of differentiation had both abundant intracellular α-syn-YFP spots and diffuse cytosolic α-syn-YFP, regardless of whether the iNs had been exposed to PFF for 3 days or not (Fig. 1, F–H). We concluded that the formation of α-syn-YFP aggregates induced by incubation with PFF is restricted to iNs and is not detected in cell types of non-neuronal origin. We note that transient or stable expression of ectopic α-syn-YFP in iNs was not toxic and did not induce cell death (see Fig. 9, I–K)—an observation relevant for many of the following experiments.

Incubation of iNs with PFFs mediates endolysosomal aggregation of cytosolic α-syn-YFP

Published observations show that α-syn aggregates induced by internalized α-syn PFFs localize to LAMP1-containing lysosomes in human H4-neuroglioma derived cells (Jiang et al., 2017), mouse Cath.a-differentiated (CAD) cells (Dilsizoglu Senol et al., 2021), and mouse-derived primary neurons (Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2011).

Using three different fluorescence microscopy-based approaches, we extended these observations to show that 3-day incubation of iNs with PFFs also induced the formation of α-syn-YFP aggregates in late endosomes and lysosomes. In the first approach (Fig. 2, A–F and Fig. S2), we used live-cell, spinning-disc confocal fluorescence microscopy to visualize iNs transiently or stably expressing α-syn-YFP that had been continuously incubated for 2 h before imaging with fluorescent Alexa Fluor 647 labeled dextran (Dextran-AF647), an endocytic fluid phase marker known to appear as intracellular fluorescent spots when accumulated in late endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 2, A–F and Fig. S2, A–D) (Ellinger et al., 1998). In the presence of PFF, these dextran spots colocalized with most PFF-induced α-syn-YFP aggregates that formed in iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP (Fig. 2, B and C; and Fig. S2 B). α-syn-YFP aggregates that were spontaneously formed in iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP and not exposed to PFFs failed to colocalize with internalized Dextran-AF647, suggesting in that case a non-endolysosomal location of the α-syn-YFP aggregates (Fig. 2 D and Fig. S2 C). 3-day incubation of α-syn-YFP expressing cells with PFFs led to partial colocalization (Fig. 2, E and F; and Fig. S2 D). These observations are therefore consistent with endolysosomal localization of PFF-induced α-syn aggregates.

Localization of PFF-induced α-Syn-YFP aggregates in endosomal and lysosomal compartments. (A, B, D, E, G, H, J, K, M, N, P, and Q) 3D visualization of live (A, B, D, and E) and chemically fixed (G, H, J, K, M, N, P, and Q) cells using spinning-disc confocal microscopy. Representative images show maximum z-projections of four consecutive optical planes, spaced 270 nm apart. (A–C) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP, incubated for 3 days without (A) or with (B) 4 µg/ml PFF, followed by a 2-h incubation with 20 µg/ml fluorescent Dextran Alexa Fluor 647. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. Bar graph (C) quantifies the fraction of dextran spots colocalized with α-syn-YFP aggregates in the absence or presence of PFF, highlighting the predominant localization of α-syn-YFP in late endosomes and lysosomes in the PFF condition. Each dot represents data from an individual cell. (D–F) iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP, incubated for 3 days without (D) or with (E) 4 µg/ml PFF, followed by 20 µg/ml Dextran Alexa Fluor 647. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. Bar graph (F) shows minimal colocalization between spontaneously formed α-syn-YFP aggregates (without PFF) and Dextran, indicating reduced endolysosomal localization. Each dot represents data from all spots in each field (five to nine cells per field). (G–L) iNs transiently (G and H) or stably (J and K) expressing α-syn-YFP, incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF for 3 days, stained for EEA1 (early endosome marker, G and J) or LAMP1 (late endosome/lysosome marker, H and K). Images represent three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. Bar graphs (I and L) quantify colocalization between α-syn-YFP aggregates and EEA1 or LAMP1 markers. In I, each dot represents data from all spots in a cell; in L, each dot represents data from all spots in a field (five to nine cells per field). (M–O) iNs incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days, immunostained for EEA1 (M) or LAMP1 (N). Images represent three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. Bar graph (O) quantifies colocalization between internalized PFF-AF647 and EEA1 or LAMP1. Each dot represents data from all spots in a field (five to nine cells per field). (P–R) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP, incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days, stained for EEA1 (P) or LAMP1 (Q). Images represent two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (R) Bar graph quantifies colocalization between α-syn-YFP aggregates and EEA1 or LAMP1 markers. Each dot represents an individual cell. Total cell counts are provided. Statistical significance (P < 0.005) is indicated by a star; “ns” denotes no statistical difference.

Localization of PFF-induced α-Syn-YFP aggregates in endosomal and lysosomal compartments. (A, B, D, E, G, H, J, K, M, N, P, and Q) 3D visualization of live (A, B, D, and E) and chemically fixed (G, H, J, K, M, N, P, and Q) cells using spinning-disc confocal microscopy. Representative images show maximum z-projections of four consecutive optical planes, spaced 270 nm apart. (A–C) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP, incubated for 3 days without (A) or with (B) 4 µg/ml PFF, followed by a 2-h incubation with 20 µg/ml fluorescent Dextran Alexa Fluor 647. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. Bar graph (C) quantifies the fraction of dextran spots colocalized with α-syn-YFP aggregates in the absence or presence of PFF, highlighting the predominant localization of α-syn-YFP in late endosomes and lysosomes in the PFF condition. Each dot represents data from an individual cell. (D–F) iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP, incubated for 3 days without (D) or with (E) 4 µg/ml PFF, followed by 20 µg/ml Dextran Alexa Fluor 647. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. Bar graph (F) shows minimal colocalization between spontaneously formed α-syn-YFP aggregates (without PFF) and Dextran, indicating reduced endolysosomal localization. Each dot represents data from all spots in each field (five to nine cells per field). (G–L) iNs transiently (G and H) or stably (J and K) expressing α-syn-YFP, incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF for 3 days, stained for EEA1 (early endosome marker, G and J) or LAMP1 (late endosome/lysosome marker, H and K). Images represent three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. Bar graphs (I and L) quantify colocalization between α-syn-YFP aggregates and EEA1 or LAMP1 markers. In I, each dot represents data from all spots in a cell; in L, each dot represents data from all spots in a field (five to nine cells per field). (M–O) iNs incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days, immunostained for EEA1 (M) or LAMP1 (N). Images represent three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. Bar graph (O) quantifies colocalization between internalized PFF-AF647 and EEA1 or LAMP1. Each dot represents data from all spots in a field (five to nine cells per field). (P–R) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP, incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days, stained for EEA1 (P) or LAMP1 (Q). Images represent two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (R) Bar graph quantifies colocalization between α-syn-YFP aggregates and EEA1 or LAMP1 markers. Each dot represents an individual cell. Total cell counts are provided. Statistical significance (P < 0.005) is indicated by a star; “ns” denotes no statistical difference.

Localization of PFF-induced α-Syn-YFP aggregates in endosomal and lysosomal compartments (associated with Fig. 2 ). (A–L) 3D visualization of (A–D) live and (E–L) chemically fixed cells imaged using spinning-disc confocal microscopy. Representative images depict maximum z-projections of the whole cell volume made from consecutive optical planes spaced 270 nm apart. (A and B) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP incubated for 3 days without (A) or with (B) 4 µg/ml PFF, followed by a 2-h incubation with 20 µg/ml fluorescent Dextran Alexa Fluor 647. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets with 3× magnification, Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (C and D) iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP incubated for 3 days without (C) or with (D) 4 µg/ml PFF, followed by 20 µg/ml Dextran Alexa Fluor 647 incubation. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets with 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (E–H) iNs expressing α-syn-YFP transiently (E and F) or stably (G and H), incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF for 3 days, were stained for EEA1 (early endosome marker, E and G) or LAMP1 (late endosome/lysosome marker, F and H). Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Enlargements with 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (I and J) iNs incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days and immune-stained for EEA1 (I) or LAMP1 (J). Images are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Enlargements with 3× magnification, Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (K and L) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days, stained for EEA1 (K) or LAMP1 (L). Images are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets with 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm.

Localization of PFF-induced α-Syn-YFP aggregates in endosomal and lysosomal compartments (associated with Fig. 2 ). (A–L) 3D visualization of (A–D) live and (E–L) chemically fixed cells imaged using spinning-disc confocal microscopy. Representative images depict maximum z-projections of the whole cell volume made from consecutive optical planes spaced 270 nm apart. (A and B) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP incubated for 3 days without (A) or with (B) 4 µg/ml PFF, followed by a 2-h incubation with 20 µg/ml fluorescent Dextran Alexa Fluor 647. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets with 3× magnification, Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (C and D) iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP incubated for 3 days without (C) or with (D) 4 µg/ml PFF, followed by 20 µg/ml Dextran Alexa Fluor 647 incubation. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets with 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (E–H) iNs expressing α-syn-YFP transiently (E and F) or stably (G and H), incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF for 3 days, were stained for EEA1 (early endosome marker, E and G) or LAMP1 (late endosome/lysosome marker, F and H). Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Enlargements with 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (I and J) iNs incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days and immune-stained for EEA1 (I) or LAMP1 (J). Images are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Enlargements with 3× magnification, Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (K and L) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP incubated with 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days, stained for EEA1 (K) or LAMP1 (L). Images are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets with 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm.

In the second approach (Fig. 2, G–L and Fig. S2, E–H), we chemically fixed iNs after the 3-day PFF incubation before imaging by spinning disc confocal fluorescence microscopy to determine the extent of colocalization of PFF-induced α-syn-YFP aggregates with antibody markers specific for early endosomes (EEA1) and lysosomes (LAMP1) (Humphries et al., 2011). In agreement with recent observations (Dilsizoglu Senol et al., 2021; Bayati et al., 2022) and the results obtained with the first approach, we found minimal colocalization of PFF-induced α-syn-YFP aggregates with EEA1 (Fig. 2, G and I; and Fig. S2 E) and extensive colocalization with LAMP1 (Fig. 2, H and I; and Fig. S2 F) in iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP. Also, in agreement with results obtained with the first approach, iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP and incubated for 3 days with PFF failed to show colocalization of the induced α-syn-YFP aggregates with EEA1 (Fig. 2, J and L; and Fig. S2 G) and showed only a small fraction of α-syn-YFP aggregates colocalized with LAMP1 (Fig. 2, K and L; and Fig. S2 H).

In the third approach (Fig. 2, M–R and Fig. S2, I–L), we incubated iNs expressing endogenous α-syn alone (Fig. 2, M–O; and Fig. S2, I and J) or transiently expressing α-syn-YFP (Fig. 2, P–R; and Fig. S2, K and L) with PFF tagged with Alexa Fluor 647 (PFF-AF647) for 3 days, followed by chemical fixation. We then used spinning disc confocal microscopy to determine the extent of colocalization of the internalized PFFs with early or late endosomes and lysosomes, identified by antibodies specific for EEA1 or LAMP1, respectively. We again found minimal colocalization of internalized PFFs with EEA1 (Fig. 2, M, O, P, and R; and Fig. S2, I and K) and extensive colocalization with LAMP1 (Fig. 2, N, O, Q, and R; and Fig. S2, J and L), indicating that transient expression of α-syn-YFP had no detectable effect on the endolysosomal traffic of internalized PFFs.

Taken together, these colocalization observations, which were consistent with published results obtained with neuronal cells (Jiang et al., 2017; Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2011; Dilsizoglu Senol et al., 2021; Karpowicz et al., 2017; Konno et al., 2012), validated our use of iNs as a convenient model system to study the early formation in endolysosomes of α-syn aggregates mediated by internalized PFFs.

Constitutive perforation of limiting membranes in late endosomes and lysosomes of iNs

The limiting membrane surrounding endolysosomes acts as a natural barrier, preventing macromolecular exchange between the lumen and the cytosol. Aggregation of α-syn within endolysosomes suggests a breach in the integrity of the limiting membrane (Dilsizoglu Senol et al., 2021), which could allow cytosolic α-syn to reach internalized PFFs retained in the lumen of perforated endolysosomes could be reached by cytosolic α-syn and then lead to PFF-seeded formation of α-syn endolysosomal aggregates. We described below two strategies we used to investigate this hypothesis.

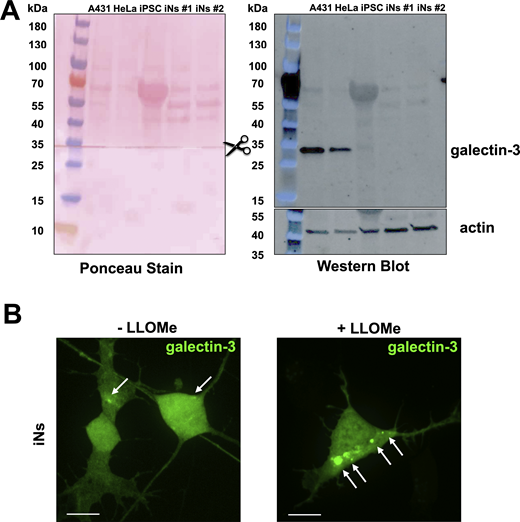

First, we implemented galectin-3 biosensors in both fixed and live cells to detect endolysosomal perforation. The recruitment of galectin-3 to damaged membranes provided a quantifiable readout for membrane integrity. It is known that damage to the endolysosomal membrane exposes luminal oligosaccharides that recruit galectins, such as galectin-3 and galectin-8, triggering repair mechanisms (Radulovic et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2018, 2020). Hence, the presence of galectin-3 puncta is commonly used as a reporter for endolysosomal damage. Using a galectin-3 antibody, we observed that ∼40% of iNs contain 1–3 endogenous galectin-3 puncta (Fig. 3, B and C), while non-neuronal SVG-A cells had only a diffuse cytosolic distribution of galectin-3 (Fig. 3 A). The immunofluorescent signal for galectin-3 in iNs was lower and closer to background levels than in SVG-A cells, consistent with differences in their relative expression levels of galectin-3 as confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. S3 A).

PFF-induced α-Syn-YFP aggregates in perforated endolysosomes. (A and B) Immunofluorescence images of SVG-A and iNs, obtained in the absence of PFFs, labeled with antibody specific for galectin-3. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 2× magnification. (C) Bar graph quantifies the fraction of cells containing galectin-3 puncta; each dot represents a biological replicate. (D–F) Live imaging of SVG-A and iNs, stably or transiently expressing eGFP-galectin-3, respectively. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 2× magnification. The bar graph in F quantifies the fraction of cells containing eGFP-galectin-3 spots; each dot represents a biological replicate. (G–L) Live imaging of iNs transiently expressing eGFP-galectin-3 incubated without (G) or with 4 µg/ml PFFs for 3 days (H), in the absence (J) or presence of 1 µM Apilimod for 3 days (K). Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 2× magnification. Images are representative of two biological replicates. Bar graphs in I and L quantify the fraction of cells containing galectin-3 puncta; each dot represents a biological replicate. Statistical significance (P < 0.005) is indicated by a star; “ns” denotes no statistical difference.

PFF-induced α-Syn-YFP aggregates in perforated endolysosomes. (A and B) Immunofluorescence images of SVG-A and iNs, obtained in the absence of PFFs, labeled with antibody specific for galectin-3. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 2× magnification. (C) Bar graph quantifies the fraction of cells containing galectin-3 puncta; each dot represents a biological replicate. (D–F) Live imaging of SVG-A and iNs, stably or transiently expressing eGFP-galectin-3, respectively. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 2× magnification. The bar graph in F quantifies the fraction of cells containing eGFP-galectin-3 spots; each dot represents a biological replicate. (G–L) Live imaging of iNs transiently expressing eGFP-galectin-3 incubated without (G) or with 4 µg/ml PFFs for 3 days (H), in the absence (J) or presence of 1 µM Apilimod for 3 days (K). Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 2× magnification. Images are representative of two biological replicates. Bar graphs in I and L quantify the fraction of cells containing galectin-3 puncta; each dot represents a biological replicate. Statistical significance (P < 0.005) is indicated by a star; “ns” denotes no statistical difference.

Endogenous expression level of galectin-3 is relatively low in iNs and validation of eGFP-galectin-3 as a sensor of endolysosome damage (associated withFig. 3 ). (A) Galectin-3 expression levels compared via SDS-PAGE and western blot of lysates from human A431, HeLa, parental iPSCs, and two independently differentiated iNs. The membrane was first probed for endogenous galectin-3, then cut at the indicated region and the lower portion was probed for actin, and finally, both portions stained with Ponceau. Western blot shows significantly lower galectin-3 expression in iPSCs and iNs when compared with A431 and HeLa cells. (B) iNs ectopically expressing eGFP-galectin-3 were treated with or without 0.5 mM LLOMe for 1 h to induce endolysosomal damage. Cells were imaged using spinning disc confocal microscopy. Representative maximum z-projection images from consecutive optical planes spaced 270 nm apart. Arrows highlight eGFP-galectin-3 spots. This experiment demonstrates the utility of eGFP-galectin-3 as a probe for extensive endolysosomal damage in iNs. Images are representative of 48 and 49 cells expressing eGFP-galectin-3 without or with LLOMe treatment from one biological replicate. Scale bar: 10 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

Endogenous expression level of galectin-3 is relatively low in iNs and validation of eGFP-galectin-3 as a sensor of endolysosome damage (associated withFig. 3 ). (A) Galectin-3 expression levels compared via SDS-PAGE and western blot of lysates from human A431, HeLa, parental iPSCs, and two independently differentiated iNs. The membrane was first probed for endogenous galectin-3, then cut at the indicated region and the lower portion was probed for actin, and finally, both portions stained with Ponceau. Western blot shows significantly lower galectin-3 expression in iPSCs and iNs when compared with A431 and HeLa cells. (B) iNs ectopically expressing eGFP-galectin-3 were treated with or without 0.5 mM LLOMe for 1 h to induce endolysosomal damage. Cells were imaged using spinning disc confocal microscopy. Representative maximum z-projection images from consecutive optical planes spaced 270 nm apart. Arrows highlight eGFP-galectin-3 spots. This experiment demonstrates the utility of eGFP-galectin-3 as a probe for extensive endolysosomal damage in iNs. Images are representative of 48 and 49 cells expressing eGFP-galectin-3 without or with LLOMe treatment from one biological replicate. Scale bar: 10 µm. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS3.

We used chimeric fluorescent galectin-3 as a live-cell biosensor to detect endolysosomal membrane damage. Upon membrane damage, the fluorescent signal redistributes from the cytosol into distinct puncta marking damaged organelles (Jia et al., 2020; Thurston et al., 2012). In iNs transiently expressing eGFP-galectin-3, this redistribution was observed as punctate spots following treatment with 0.5 mM L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester (LLOMe) for 1 h, inducing endolysosomal damage (Fig. S3 B). In untreated iNs expressing eGFP-galectin-3, ∼30% of cells exhibited one to three fluorescent spots (Fig. 3, E and F), comparable with the number of endogenous galectin-3 puncta detected by immunofluorescence in cells lacking eGFP-galectin-3 expression. These results confirm that ectopically expressed eGFP-galectin-3 reliably serves as a biosensor for endolysosomal damage in iNs. A 3-day incubation with PFFs did not change the fraction of iNs containing eGFP-galectin spots (Fig. 3, G–I). These puncta were absent in adjacent, non-expressing cells, ruling out extracellular uptake of eGFP-galectin-3. In contrast, SVG-A cells showed only a diffuse cytosolic distribution of eGFP-galectin-3 (Fig. 3 D), as seen in other non-neuronal cells (Freeman et al., 2013; Paz et al., 2010; Aits et al., 2015). Thus, galectin-3 recruitment in both fixed and live cells detected the presence of perforated endolysosomes in iNs that had not been exposed to PFFs. Consistent with a recent report on tau-PFF-mediated aggregation (Rose et al., 2024), we similarly observed that galectin-3 puncta did not colocalize with PFF-seeded α-syn-YFP endolysosomal aggregates.

Our second strategy used live-cell imaging combined with ratiometric fluorescence microscopy to monitor pH changes in endolysosomes upon membrane damage. By tracking pHrodo Green-tagged Dextran, we could directly assess the luminal pH. Membrane rupture is expected to neutralize the endolysosomal lumen by allowing equilibration with the cytosol (Maxson and Grinstein, 2014). We measured luminal pH using a spinning disc and ratiometric fluorescence microscopy with Dextran conjugated to pH-sensitive pHrodo Green and pH-insensitive Alexa Fluor 560. The fluorescence from internalized Dextran spots was monitored at early and late time points (1 and 6 h, respectively). At the early time point, only ∼0.8% of labeled compartments in iNs were neutral (Fig. 4, B and C), increasing to 3–6% at the later time point (Fig. 4, E, G, H, and J), like findings in primary rat hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4, F and G). In contrast, endosomes and lysosomes in parental iPSCs remained acidic (Fig. 4, A, C, D, and G). Late endosomes and lysosomes in iNs were generally slightly less acidic than those in iPSCs (Fig. 4, C and G).

pH of endolysosomes. (A–G) Live imaging of iPSCs and iNs incubated with 20 µg/ml of pH-sensitive pHrodo Dextran 488 and pH-insensitive Dextran Alexa Fluor 560 for 1 h (A–C) or 2 h followed by a 4-h chase (D–G), labeling early/late endosomes and late endosomes/lysosomes, respectively. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Heat map bars show pH values derived from fluorescence ratios in permeabilized samples incubated with solutions of different pH. Histogram in C presents average pH values ± standard deviation from Dextran-containing spots, based on data from 14,586 spots across 60 fields from 3 independently differentiated iN samples and from the 5,366 spots across 20 fields from iPSCs, respectively. Histogram in G presents average pH values ± standard deviation from Dextran-containing spots, based on data from 20,293 spots across 60 fields from one dissection of primary rat hippocampal neurons, from 10,922 spots across 20 fields from three independently differentiated iN samples and from the 5,366 spots across 20 fields from iPSCs, respectively. The error at 95% confidence of the calculated pH values is ∼0.4 pH units. (H–J) iNs incubated with or without 4 µg/ml PFF for 3 days, then treated with the dextran pH sensor mixture for 2 h and a 4-h chase. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Heat map and histogram (J) as in C and G, with data from 3,497 to 2,239 spots across 10 fields from three independently differentiated iN samples. (K) Z-maximum projection from a z-stack of a 10-min time series, acquired by live-cell lattice light sheet microscopy 4 h after iNs were incubated for 2 h with a mixture of pH-sensitive pHrodo Green dextran and pH-insensitive Alexa Fluor 560 Dextran. For clarity, the red and green channels were shifted horizontally by 10 pixels. Scale bar: 5 µm. Snapshots represent images from time series acquired in seven different fields from one differentiated iN biological sample. The image highlights the presence of endolysosomes with neutral pH. Representative of two biological replicates. (L) Ratiometric fluorescence intensity plots of the endolysosomes highlighted in A, based on a 10-min 3D time series acquired using the ZEISS Lattice Light Sheet 7 microscope with a 2.6-s interval and 0.25-µm spacing between optical planes along the z-axis. Partial traces 1 and 3 illustrate examples of endolysosomes maintaining neutral pH, while trace 2 shows an endolysosome that remains acidic. Arrows indicate the acquisition times corresponding to the snapshots in J. (M) Representative image from a 3D 5-min time series of an SVG-A cell, captured by ratiometric fluorescence imaging using MOSAIC at 2-s intervals with 0.3 µm spacing between optical planes along the z-axis. The image demonstrates the absence of endolysosomes with neutral pH. Representative of three biological replicates. (N) Ratiometric fluorescence intensity plots of the endolysosomes highlighted in C, showing examples of endolysosomes maintaining constant acidic pH. Arrows indicate the acquisition times corresponding to the snapshots in L.

pH of endolysosomes. (A–G) Live imaging of iPSCs and iNs incubated with 20 µg/ml of pH-sensitive pHrodo Dextran 488 and pH-insensitive Dextran Alexa Fluor 560 for 1 h (A–C) or 2 h followed by a 4-h chase (D–G), labeling early/late endosomes and late endosomes/lysosomes, respectively. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Heat map bars show pH values derived from fluorescence ratios in permeabilized samples incubated with solutions of different pH. Histogram in C presents average pH values ± standard deviation from Dextran-containing spots, based on data from 14,586 spots across 60 fields from 3 independently differentiated iN samples and from the 5,366 spots across 20 fields from iPSCs, respectively. Histogram in G presents average pH values ± standard deviation from Dextran-containing spots, based on data from 20,293 spots across 60 fields from one dissection of primary rat hippocampal neurons, from 10,922 spots across 20 fields from three independently differentiated iN samples and from the 5,366 spots across 20 fields from iPSCs, respectively. The error at 95% confidence of the calculated pH values is ∼0.4 pH units. (H–J) iNs incubated with or without 4 µg/ml PFF for 3 days, then treated with the dextran pH sensor mixture for 2 h and a 4-h chase. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Heat map and histogram (J) as in C and G, with data from 3,497 to 2,239 spots across 10 fields from three independently differentiated iN samples. (K) Z-maximum projection from a z-stack of a 10-min time series, acquired by live-cell lattice light sheet microscopy 4 h after iNs were incubated for 2 h with a mixture of pH-sensitive pHrodo Green dextran and pH-insensitive Alexa Fluor 560 Dextran. For clarity, the red and green channels were shifted horizontally by 10 pixels. Scale bar: 5 µm. Snapshots represent images from time series acquired in seven different fields from one differentiated iN biological sample. The image highlights the presence of endolysosomes with neutral pH. Representative of two biological replicates. (L) Ratiometric fluorescence intensity plots of the endolysosomes highlighted in A, based on a 10-min 3D time series acquired using the ZEISS Lattice Light Sheet 7 microscope with a 2.6-s interval and 0.25-µm spacing between optical planes along the z-axis. Partial traces 1 and 3 illustrate examples of endolysosomes maintaining neutral pH, while trace 2 shows an endolysosome that remains acidic. Arrows indicate the acquisition times corresponding to the snapshots in J. (M) Representative image from a 3D 5-min time series of an SVG-A cell, captured by ratiometric fluorescence imaging using MOSAIC at 2-s intervals with 0.3 µm spacing between optical planes along the z-axis. The image demonstrates the absence of endolysosomes with neutral pH. Representative of three biological replicates. (N) Ratiometric fluorescence intensity plots of the endolysosomes highlighted in C, showing examples of endolysosomes maintaining constant acidic pH. Arrows indicate the acquisition times corresponding to the snapshots in L.

Live-cell imaging of iNs using lattice light sheet microscopy showed that the neutral endolysosomes maintained a neutral pH for 5–10 min. We monitored pH dynamics by measuring the ratio of fluorescence pHrodo Green and Alexa Fluor 560 Dextrans by allowing them to accumulate in endolysosomes for 6 h and then capturing whole-cell volume images at 2–2.6-s intervals. While most endolysosomes in iNs were acidic (Fig. S4 C), a subset maintained a neutral pH throughout the 5–10 min time series (examples in Fig. 4, K and L; and Fig. S4B). In control SVG-A cells, all endolysosomes remained acidic (examples in Fig. 4, M and N; and Fig. S4 D). These findings support our inference that a subset of endolysosomes in iNs is constitutively compromised.

Representative fluorescence traces of the internalized pH sensor in endolysosomes within iNs and SVG-A cells (associated with Fig. 4 ). (A) Sequential Z-maximum projections from a 3D time series of an iN cell, captured with 0.25 µm z-spacing and 2.6-s intervals using a ZEISS Lattice Lightsheet 7. The images are from a 10-min time series that began 4 h after a 2-h incubation with a Dextran mixture tagged with pHrodo Green (pH-sensitive) and Alexa Fluor 560 (pH-insensitive). For visualization, red and green channels were shifted horizontally by 10 pixels. Regions showing a red signal without green indicate neutral endolysosomes; the white arrow highlights a neutral endolysosome. The image represents two biological replicates. Scale bar: 5 µm. Data include 10-min time series from seven fields in a single differentiated iN sample. (B–D) Ratiometric fluorescence intensity plots of neutral (B) and acidic (C) endolysosomes in the somas of seven iNs, and acidic endolysosomes (D) from four SVG-A cells. iN data were acquired from 3D, 10-min time series captured every 2.6 s with 0.25 µm z-spacing, using a ZEISS Lattice Lightsheet 7. SVG-A data were acquired from 3D, 7-min time series captured every 2 s, with 0.25 µm z-spacing, using a lattice light sheet microscope modified with adaptive optics (MOSAIC). Vertical scale is logarithmic, and traces are arbitrarily aligned at t = 0 s. Shorter traces reflect incomplete tracking by the CME program.

Representative fluorescence traces of the internalized pH sensor in endolysosomes within iNs and SVG-A cells (associated with Fig. 4 ). (A) Sequential Z-maximum projections from a 3D time series of an iN cell, captured with 0.25 µm z-spacing and 2.6-s intervals using a ZEISS Lattice Lightsheet 7. The images are from a 10-min time series that began 4 h after a 2-h incubation with a Dextran mixture tagged with pHrodo Green (pH-sensitive) and Alexa Fluor 560 (pH-insensitive). For visualization, red and green channels were shifted horizontally by 10 pixels. Regions showing a red signal without green indicate neutral endolysosomes; the white arrow highlights a neutral endolysosome. The image represents two biological replicates. Scale bar: 5 µm. Data include 10-min time series from seven fields in a single differentiated iN sample. (B–D) Ratiometric fluorescence intensity plots of neutral (B) and acidic (C) endolysosomes in the somas of seven iNs, and acidic endolysosomes (D) from four SVG-A cells. iN data were acquired from 3D, 10-min time series captured every 2.6 s with 0.25 µm z-spacing, using a ZEISS Lattice Lightsheet 7. SVG-A data were acquired from 3D, 7-min time series captured every 2 s, with 0.25 µm z-spacing, using a lattice light sheet microscope modified with adaptive optics (MOSAIC). Vertical scale is logarithmic, and traces are arbitrarily aligned at t = 0 s. Shorter traces reflect incomplete tracking by the CME program.

Electron microscopic visualization of perforated limiting membranes in endosomes and lysosomes of iNs and primary neurons

To understand what type of endosomal or lysosomal opening accounts for the loss of the usual pH gradient and for the local clustering of galectin-3, we used FIB-SEM (Fig. 5; and Videos 1, 2, and 3) to volumetrically examine at ∼5 nm isotropic resolution iNs prepared by high-pressure freezing and freeze substitution, an approach that minimizes membrane perturbations (Studer et al., 2008). We could identify endosomes and lysosomes by their distinctive shape, size, and appearance. Unlike traditional single-plane imaging, our volumetric data enabled the detection of small orifices in nearly any orientation relative to the beam direction. We identified 3 early endosomes with nanoscale ruptures in the limiting membrane out of 147 early endosomes (organelles with none or few intraluminal vesicles) and 5 ruptures in 91 endolysosomes (organelles containing intraluminal vesicles alone or a mix of intraluminal membranes and membrane fragments). The ruptures varied in shape and size, measuring between 25 and 185 nm along their shortest and longest orthogonal axes, respectively (Fig. 5, A, B, and E; Fig. S5; and Videos 1 and 2). Given the 5-nm per voxel resolution of our FIB-SEM analysis, we estimate that potential perforations <20 nm (4 voxels) likely went undetected. The staining pattern at the damage sites suggested minor leakage of luminal contents into the cytosol.

Visualization by FIB-SEM of perforated endolysosomes in iNs and primary mouse neurons. (A–C) Orthogonal views, each averaged from three consecutive planes, and surface renderings of iNs visualized by FIB-SEM, acquired at 5 × 5 × 5 nm resolution. Samples were prepared by high-pressure freezing and freeze substitution. Scale bars: 200, 500, 1,000 nm. A and B show representative examples from two different iNs with perforated endolysosomes, each exhibiting a small nanopore in the limiting membrane, highlighted by the arrowheads. Data from 10 somas revealed 5 compromised endolysosomes and 3 early endosomes out of a total of 91 endolysosomes and 147 early endosomes examined. Inspection of limiting membranes in 13 endosomes from 37 volumetric cross-sections of different neurites did not reveal nanopores. C shows a representative endolysosome from parental iPSCs, intact and lacking nanopores. (D) The top three panels show single-plane views of three perforated endolysosomes, highlighted by the arrowheads, from three different mouse CA1 pyramidal neurons, prepared by chemical fixation and imaged by volumetric FIB-SEM at 5.4 × 5.4 × 16 nm resolution (Sheu et al., 2022). The bottom panel shows a zoomed-out view of the region containing the upper-left panel. Scale bars: 400, 4,000 nm. (E) Representative examples of nanopores in the limiting membranes of two endolysosomes (left and center panels) and one early endosome (right panel) from somas of three different iNs. Perforation outlines were manually traced with single pixels using LabKit, with voxel resolution of 5 nm. The longest and shortest inner dimensions of the perforations were measured in orthogonal views using FIJI. For visualization, voxels were enlarged during 3D rendering in Imaris to clearly depict the perforations.

Visualization by FIB-SEM of perforated endolysosomes in iNs and primary mouse neurons. (A–C) Orthogonal views, each averaged from three consecutive planes, and surface renderings of iNs visualized by FIB-SEM, acquired at 5 × 5 × 5 nm resolution. Samples were prepared by high-pressure freezing and freeze substitution. Scale bars: 200, 500, 1,000 nm. A and B show representative examples from two different iNs with perforated endolysosomes, each exhibiting a small nanopore in the limiting membrane, highlighted by the arrowheads. Data from 10 somas revealed 5 compromised endolysosomes and 3 early endosomes out of a total of 91 endolysosomes and 147 early endosomes examined. Inspection of limiting membranes in 13 endosomes from 37 volumetric cross-sections of different neurites did not reveal nanopores. C shows a representative endolysosome from parental iPSCs, intact and lacking nanopores. (D) The top three panels show single-plane views of three perforated endolysosomes, highlighted by the arrowheads, from three different mouse CA1 pyramidal neurons, prepared by chemical fixation and imaged by volumetric FIB-SEM at 5.4 × 5.4 × 16 nm resolution (Sheu et al., 2022). The bottom panel shows a zoomed-out view of the region containing the upper-left panel. Scale bars: 400, 4,000 nm. (E) Representative examples of nanopores in the limiting membranes of two endolysosomes (left and center panels) and one early endosome (right panel) from somas of three different iNs. Perforation outlines were manually traced with single pixels using LabKit, with voxel resolution of 5 nm. The longest and shortest inner dimensions of the perforations were measured in orthogonal views using FIJI. For visualization, voxels were enlarged during 3D rendering in Imaris to clearly depict the perforations.

Perforated endolysosome from an iN. The video starts with a series of consecutive single-plane images traversing the endolysosome depicted in Fig. 5 A, visualized using FIB-SEM, concluding with a three-dimensional surface depiction of the limiting membrane. This rendering accentuates a single perforation corresponding to a nanopore situated within the limiting membrane. Playback speed, 30 frames/second.

Perforated endolysosome from an iN. The video starts with a series of consecutive single-plane images traversing the endolysosome depicted in Fig. 5 A, visualized using FIB-SEM, concluding with a three-dimensional surface depiction of the limiting membrane. This rendering accentuates a single perforation corresponding to a nanopore situated within the limiting membrane. Playback speed, 30 frames/second.

Perforated endolysosome from an iN. The video starts with a series of consecutive single-plane images traversing the endolysosome depicted in Fig. 5 B, visualized using FIB-SEM, concluding with a three-dimensional surface depiction of the limiting membrane. This rendering accentuates a single perforation corresponding to a nanopore situated within the limiting membrane. Playback speed, 30 frames/second.

Perforated endolysosome from an iN. The video starts with a series of consecutive single-plane images traversing the endolysosome depicted in Fig. 5 B, visualized using FIB-SEM, concluding with a three-dimensional surface depiction of the limiting membrane. This rendering accentuates a single perforation corresponding to a nanopore situated within the limiting membrane. Playback speed, 30 frames/second.

Intact endolysosome from an iPSC. The video starts with a series of consecutive single-plane images traversing the endolysosome depicted in Fig. 5 C, visualized using FIB-SEM, concluding with a three-dimensional surface depiction of the limiting membrane. This rendering accentuates the absence of perforations in the limiting membrane. Playback speed, 30 frames/second.

Intact endolysosome from an iPSC. The video starts with a series of consecutive single-plane images traversing the endolysosome depicted in Fig. 5 C, visualized using FIB-SEM, concluding with a three-dimensional surface depiction of the limiting membrane. This rendering accentuates the absence of perforations in the limiting membrane. Playback speed, 30 frames/second.

Visualization of perforated endolysosomes in iNs and primary mouse neurons using FIB-SEM (associated with Fig. 5 ). (A–E) Representative examples of nanopores in the limiting membranes of (A–C) three endolysosomes (top panels) and (D and E) two early endosomes (bottom panels) within the somas of distinct iNs. Perforation boundaries were manually traced at single-pixel thickness using LabKit, with a voxel resolution of 5 nm. The longest and shortest inner dimensions of each perforation were quantified in orthogonal views using FIJI. For clarity in 3D rendering, voxel sizes were increased in Imaris to enhance the visibility of the perforations. (F) Each point in the plot represents the longest and shortest inner dimensions of individual nanopores observed in endolysosomes or early endosomes within the somas of various iNs.

Visualization of perforated endolysosomes in iNs and primary mouse neurons using FIB-SEM (associated with Fig. 5 ). (A–E) Representative examples of nanopores in the limiting membranes of (A–C) three endolysosomes (top panels) and (D and E) two early endosomes (bottom panels) within the somas of distinct iNs. Perforation boundaries were manually traced at single-pixel thickness using LabKit, with a voxel resolution of 5 nm. The longest and shortest inner dimensions of each perforation were quantified in orthogonal views using FIJI. For clarity in 3D rendering, voxel sizes were increased in Imaris to enhance the visibility of the perforations. (F) Each point in the plot represents the longest and shortest inner dimensions of individual nanopores observed in endolysosomes or early endosomes within the somas of various iNs.

In contrast, endosomes and lysosomes in parental iPSCs, as shown in Fig. 5 C and Video 3, and in non-neuronal cell lines such as SVG-A human fetal glial–derived cells, HEK293A human epithelial–derived cells, SUM159 human breast carcinoma–derived cells, BSC-1 African green monkey kidney epithelial–derived cells, U2OS human sarcoma–derived cells (Gallusser et al., 2023), and HeLa human cells (Heinrich et al., 2021) showed no such openings. Consequently, we proposed that the membrane breaches in iNs directly observed by FIB-SEM represent the endolysosomal damage and the inferred interaction between luminal contents and adjacent cytosol we postulated from optical microscopy.

We also visualized neurons in their natural environment within an adult mouse brain, focusing on the endolysosomal integrity. Specifically, hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in mouse brains were chemically fixed and visualized in our laboratory with FIB-SEM imaging at a resolution of 8 × 8 × 20 nm (Fig. 5 D) (Sheu et al., 2022); we also analyzed similar images collected with 5.5 × 5.5 × 15 nm resolution at Janelia Research Campus (Sheu et al., 2022). The resulting data showed that the mouse brain neurons also contained a subset of endosomes and lysosomes with compromised limiting membranes, just as in our iN culture model. By contrast, inspection of FIB-SEM images acquired at 8 × 8 × 8 nm resolution of chemically fixed mouse liver (Parlakgül et al., 2022) and P7 mouse skin cells (OpenOrganelle, HMMI) failed to show damaged endosomes, endolysosomes, or lysosomes. Thus, there appears to be a neuron-specific propensity for perforation to develop in the endolysosomal compartment.

Pharmacological inhibition of endosomal PIKfyve kinase activity in iNs prevents PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP aggregation

The phosphoinositides PI(5)P and PI(3,5)P2, generated by the endolysosomal PIKfyve kinase, are required for efficient vesicular cargo traffic from late endosomes to lysosomes and for autophagosome maturation (Kim et al., 2014; Bissig et al., 2017; Rutherford et al., 2006; Choy et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2019). Without these lipids, endosomes enlarge into distended, vacuole-like structures (Krishna et al., 2016; Bissig et al., 2017; Choy et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2020).

PIKfyve kinase inhibition with its inhibitors Apilimod (Cai et al., 2013) or Vacuolin-1 (Cerny et al., 2004) led to the expected enlarged endosomes in iNs (Figs. 6, 7, and 8) just as seen in non-neuronal cells (Kang et al., 2020; Cerny et al., 2004). This treatment did not hinder receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin-AF647 (Fig. 6, A–C; 5′ Tf pulse), fluid-phase uptake of Dextran-AF647 (Fig. 6, D–F; 3 h uptake), or PFF-AF647 internalization (Fig. 6, G–I; 3-day uptake). While iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP incubated for 3 days with PFFs generated PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP aggregates in endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 7 A), the aggregates failed to form if Vacuolin-1 (Fig. 7, B and C) or Apilimod (Fig. 7, C–G) were present during PFF incubation. In contrast to iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP, iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP and treated with Apilimod exhibited α-syn-YFP aggregates that did not colocalize with internalized Dextran (Fig. 7 J). Thus, while PIKfyve inhibition interfered with PFF-mediated α-syn aggregation in endolysosomes, it did not appear to affect PFF-independent α-syn aggregate formation in the cytosol (Fig. 7, H–K).

PIKfyve inhibition doesn’t affect the endocytosis of PFFs. (A–I) iNs were incubated with (A and B) 20 µg/ml Transferrin AF647 for 5 min, (C and D) 20 µg/ml Dextran-AF647 for 2 h, or (E and F) 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days, in the absence (A, D, and G) or presence (B, E, and H) of 100 nM Apilimod. Cells were imaged using live-cell 3D spinning-disc confocal microscopy. Maximum z-projection images are representative of three biological replicates for A and B and four biological replicates for D–H. Cells are outlined with dotted lines. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show a 3× magnification with a scale bar of 3.3 µm. (C, F, and I) Quantitative analysis shows that 100 nM Apilimod did not affect the uptake of Transferrin, Dextran-AF647, or PFF-AF647. Each dot represents the total relative fluorescence intensity per cell for each internalized cargo. The number of cells analyzed is indicated.

PIKfyve inhibition doesn’t affect the endocytosis of PFFs. (A–I) iNs were incubated with (A and B) 20 µg/ml Transferrin AF647 for 5 min, (C and D) 20 µg/ml Dextran-AF647 for 2 h, or (E and F) 4 µg/ml PFF-AF647 for 3 days, in the absence (A, D, and G) or presence (B, E, and H) of 100 nM Apilimod. Cells were imaged using live-cell 3D spinning-disc confocal microscopy. Maximum z-projection images are representative of three biological replicates for A and B and four biological replicates for D–H. Cells are outlined with dotted lines. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show a 3× magnification with a scale bar of 3.3 µm. (C, F, and I) Quantitative analysis shows that 100 nM Apilimod did not affect the uptake of Transferrin, Dextran-AF647, or PFF-AF647. Each dot represents the total relative fluorescence intensity per cell for each internalized cargo. The number of cells analyzed is indicated.

PIKfyve inhibition prevents PFF-induced α-syn aggregation. (A, B, and D–G) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP were incubated for 3 days without, with 4 µg/ml PFF, and combinations of 4 µg/ml PFF with Apilimod or Vacuolin-1 at specified concentrations. The remaining images are maximum z-projections of the whole cell volume. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification, Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (C) Bar graph quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates; each dot represents data from a biological replicate. (H–J) iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP were subjected to similar 3-day incubation protocols, including no treatment, exposure to 4 µg/ml PFF, and PFF combined with 100 nM Apilimod and including a 2-h pre-imaging uptake of Dextran-AF647. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (K) Bar graph quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates; each dot represents data from a biological replicate.

PIKfyve inhibition prevents PFF-induced α-syn aggregation. (A, B, and D–G) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP were incubated for 3 days without, with 4 µg/ml PFF, and combinations of 4 µg/ml PFF with Apilimod or Vacuolin-1 at specified concentrations. The remaining images are maximum z-projections of the whole cell volume. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets show 3× magnification, Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (C) Bar graph quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates; each dot represents data from a biological replicate. (H–J) iNs stably expressing α-syn-YFP were subjected to similar 3-day incubation protocols, including no treatment, exposure to 4 µg/ml PFF, and PFF combined with 100 nM Apilimod and including a 2-h pre-imaging uptake of Dextran-AF647. Scale bar: 10 µm. Insets provide 3× magnification. Scale bar: 3.3 µm. (K) Bar graph quantifies the fraction of cells containing α-syn-YFP aggregates; each dot represents data from a biological replicate.

PIKfyve inhibition prevents the formation of neutral endolysosomes. (A–D) iNs without ectopic α-syn-YFP expression were incubated for 8 h with or without 4 µg/ml PFF, in the presence or absence of 100 nM Apilimod. Before in vivo pH imaging, cells were incubated with 20 µg/ml each of pH-sensitive pHrodo Dextran 488 and pH-insensitive Dextran Alexa Fluor 560 for 2 h, followed by a 4-h chase to label late endosomes, endolysosomes, and lysosomes. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Heat maps show pH values derived from fluorescence ratios in permeabilized iNs incubated with pH-adjusted solutions. (E) Histogram shows average pH values ± standard deviation from 8,036, 5,135, 2,382, and 2,575 Dextran-containing spots across six fields from three independent iN differentiations treated with the indicated combinations of PFF and Apilimod. (F–I) Experimental design as in A–D, except iNs were incubated with or without 4 µg/ml PFF for 3 days and 8 h, with 100 nM Apilimod added during the last 8 h. Samples were subjected to in vivo pH imaging as in A–D. Images are representative of six biological replicates for F–H and three replicates for I. Scale bar: 10 µm. Heat maps show pH values from fluorescence ratios in permeabilized iNs in pH-calibrated solutions. (J) The histogram shows average pH values ± standard deviation from 8,896, 3,838, and 271 Dextran-containing spots across six fields from three independent iN differentiations treated with the indicated combinations of PFF and Apilimod.

PIKfyve inhibition prevents the formation of neutral endolysosomes. (A–D) iNs without ectopic α-syn-YFP expression were incubated for 8 h with or without 4 µg/ml PFF, in the presence or absence of 100 nM Apilimod. Before in vivo pH imaging, cells were incubated with 20 µg/ml each of pH-sensitive pHrodo Dextran 488 and pH-insensitive Dextran Alexa Fluor 560 for 2 h, followed by a 4-h chase to label late endosomes, endolysosomes, and lysosomes. Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. Heat maps show pH values derived from fluorescence ratios in permeabilized iNs incubated with pH-adjusted solutions. (E) Histogram shows average pH values ± standard deviation from 8,036, 5,135, 2,382, and 2,575 Dextran-containing spots across six fields from three independent iN differentiations treated with the indicated combinations of PFF and Apilimod. (F–I) Experimental design as in A–D, except iNs were incubated with or without 4 µg/ml PFF for 3 days and 8 h, with 100 nM Apilimod added during the last 8 h. Samples were subjected to in vivo pH imaging as in A–D. Images are representative of six biological replicates for F–H and three replicates for I. Scale bar: 10 µm. Heat maps show pH values from fluorescence ratios in permeabilized iNs in pH-calibrated solutions. (J) The histogram shows average pH values ± standard deviation from 8,896, 3,838, and 271 Dextran-containing spots across six fields from three independent iN differentiations treated with the indicated combinations of PFF and Apilimod.

Aggregation of cytosolic α-syn in iNs mediated by internalized PFFs occurs in constitutively perforated endolysosomes

Since PIKfyve inhibition by Apilimod blocked PFF-mediated α-syn-YFP aggregation, we investigated whether the same treatment would decrease the proportion of perforated endolysosomes, as indicated by eGFP-galectin-3 puncta. After 3 days of Apilimod treatment, the number of eGFP-galectin-3 puncta and the number of spots per iN remained unchanged (Fig. 3, J–L). These galectin-3 puncta did not associate with the characteristic vacuolated endolysosomes typically seen upon PIKfyve inhibition, suggesting that the eGFP-galectin-3 spots labeled non-enlarged endolysosomes, potentially due to limiting membrane perforations. Another explanation is that damaged endolysosomes underwent endophagy, which does not lead to vacuolation in response to Apilimod (Sharma et al., 2019).

The lack of Apilimod’s effect on galectin-3 recruitment suggests that this form of membrane damage may not correspond to the perforations reported by pH neutralization (Rose et al., 2024). To investigate further, we used our in vivo pH imaging assay with dextran to assess the effect of PIKfyve inhibition on endolysosomes with constitutive perforations. Neutral endolysosomes were absent in iNs treated with Apilimod, regardless of PFF exposure, at a time point at which α-syn aggregates had not yet formed (Fig. 8, A–E). Apilimod treatment reduced but did not eliminate the proportion of neutral endolysosomes in iNs exposed to PFFs for 3 days, followed by an additional 8-h incubation, at a time at which α-syn aggregates formed (Fig. 8, F–J). As expected, in iNs not exposed to PFFs, 8-h Apilimod treatment eliminated neutral endolysosomes without altering the distribution of acidic pH values (Fig. 8, E and J). These findings suggest that internalized PFFs do not induce endolysosomal damage detected by galectin-3 recruitment (Fig. 3, G–I) or perforations detected as neutral endolysosomes (Fig. 4, H–J; and Fig. 8, C, E, H, and J). Instead, PIKfyve inhibition reduces the proportion of neutral endolysosomes without α-syn aggregates seeded by internalized PFFs (Fig. 8 E). This implies that α-syn aggregation, which requires exposure of internalized PFFs to cytosolic α-syn, occurs in pre-existing, constitutively perforated endolysosomes, rather than in PFF-induced damaged endolysosomes as previously described (See et al., 2021, Preprint; Dilsizoglu Senol et al., 2021; Freeman et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2017). Our observations do not rule out the possibility that the aggregates seeded by PFFs may eventually cause further disruption of the endolysosomal limiting membrane.

Pharmacological inhibition of PIKfyve activity protects neurons from death caused by PFF-induced α-syn endolysosomal aggregation

Prolonged exposure of primary neurons (Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2011; Redmann et al., 2017) or rodent brains (Desplats et al., 2009) to PFFs is toxic and leads to neuronal cell death. Using our iN-model system, we recapitulated similar toxicity in response to prolonged incubation with PFFs. Representative images of iNs incubated with cell impermeant BOBO-3 (to detect nucleic acids in dead cells) and cell-permeant calcein AM (to detect viable cells) and the corresponding quantitative analysis (Fig. 9) showed that 10-day exposure to PFFs led to the accumulation of α-syn-YFP aggregates (Fig. 9 B) and to the progressive death of up to ∼50% of the iNs compared with only 10% of iNs not exposed to PFFs during the same period (Fig. 9, K and M). The extent of cell death was similar regardless of the absence (Fig. 9 I) or presence of stably (Fig. 9 J) or transiently (Fig. 9, K and M) expressed α-syn-YFP. We used parental iPSCs as a non-neuronal negative control, as they do not form PFF-mediated aggregates (Fig. 1, I and J); as expected, these cells also did not undergo PFF-induced cell death (Fig. 9 H).

Effect of PIKfyve inhibition on PFF-induced α-syn aggregation and neuronal death in iNs. (A–C) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP were cultured for 10 days with or without 4 µg/ml PFFs, in the presence or absence of 100 nM Apilimod. PIKfyve inhibition reduced the accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates. Images are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. (D–G) iNs were grown for 10 days with or without 4 µg/ml PFFs, in the presence or absence of 100 nM Apilimod or 1 µM Vacuolin. Cells were stained with calcein AM to identify live cells and BOBO-3-iodide to label dead cells prior to imaging. Representative images from three biological replicates are shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. (H–M) Quantitative analysis of PIKfyve inhibition on PFF-induced neuronal death. Data represent imaging fields with values averaged and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data are based on at least two biological replicates, with each data point representing observations from 20 to 40 imaging fields, containing 10–25 iPSCs or iNs per field. Statistical significance (P < 0.0001) is indicated by a star; “ns” denotes no statistical difference. (H) Bar graph showing the fraction of live and dead iPSCs over a 10-day period with or without 4 µg/ml PFFs. Apilimod (100 nM) was administered either throughout the entire 10 days or during the last 6 days. Cells were passaged every 3 days at a 3× dilution. Aliquots were plated in 8-well glass-bottom chambers and imaged on days 6 and 10, following incubation with calcein AM and BOBO-3-iodide. (I–K) Bar graphs summarizing the fraction of live and dead iNs not expressing α-syn-YFP or those stably or transiently expressing α-syn-YFP, subjected to the same PFF and Apilimod or 1 µM Vacuolin-1 treatment as described in H. (L) Schematic representation of the experimental design and summary of results for the setup depicted in M. (M) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP were treated with 100 nM Apilimod throughout the entire 10-day period or restricted to the last 2, 4, 6, or 8 days. An intermittent schedule involved alternating 2-day incubation periods with Apilimod, beginning on day 1 of the 10-day period.

Effect of PIKfyve inhibition on PFF-induced α-syn aggregation and neuronal death in iNs. (A–C) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP were cultured for 10 days with or without 4 µg/ml PFFs, in the presence or absence of 100 nM Apilimod. PIKfyve inhibition reduced the accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates. Images are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bar: 10 µm. (D–G) iNs were grown for 10 days with or without 4 µg/ml PFFs, in the presence or absence of 100 nM Apilimod or 1 µM Vacuolin. Cells were stained with calcein AM to identify live cells and BOBO-3-iodide to label dead cells prior to imaging. Representative images from three biological replicates are shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. (H–M) Quantitative analysis of PIKfyve inhibition on PFF-induced neuronal death. Data represent imaging fields with values averaged and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data are based on at least two biological replicates, with each data point representing observations from 20 to 40 imaging fields, containing 10–25 iPSCs or iNs per field. Statistical significance (P < 0.0001) is indicated by a star; “ns” denotes no statistical difference. (H) Bar graph showing the fraction of live and dead iPSCs over a 10-day period with or without 4 µg/ml PFFs. Apilimod (100 nM) was administered either throughout the entire 10 days or during the last 6 days. Cells were passaged every 3 days at a 3× dilution. Aliquots were plated in 8-well glass-bottom chambers and imaged on days 6 and 10, following incubation with calcein AM and BOBO-3-iodide. (I–K) Bar graphs summarizing the fraction of live and dead iNs not expressing α-syn-YFP or those stably or transiently expressing α-syn-YFP, subjected to the same PFF and Apilimod or 1 µM Vacuolin-1 treatment as described in H. (L) Schematic representation of the experimental design and summary of results for the setup depicted in M. (M) iNs transiently expressing α-syn-YFP were treated with 100 nM Apilimod throughout the entire 10-day period or restricted to the last 2, 4, 6, or 8 days. An intermittent schedule involved alternating 2-day incubation periods with Apilimod, beginning on day 1 of the 10-day period.

Inhibition of PIKfyve in iNs prevented PFF-mediated cell death. Representative images show the absence of α-syn-YFP aggregates (Fig. 9 C) and significantly reduced incidence of cell death when iNs were co-incubated for 10 days with PFF and Apilimod (Fig. 9, F, I, J, and M) or PFF and Vacuolin-1 (Fig. 9, G and K). Comparable Apilimod or Vacuolin treatment of iNs during the last 6 days of PFF incubation afforded partial protection (Fig. 9, J, K, and M), but shorter Apilimod treatments in the last 2 or 4 days, or sequentially alternating 2-day treatments on days 0, 4, and 8 did not (Fig. 9, L and M). Off-target effects of Apilimod or Vacuolin-1 were unlikely as Apilimod inhibited more strongly than Vacuolin-1, consistent with their relative inhibitory potencies for PIKfyve enzymatic activity in vitro (Sano et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2014) and for the infectivity of PIKfyve-kinase dependent Zaire Ebola virus or SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in vivo (Kant et al., 2023, Preprint; Kang et al., 2020). We conclude that pharmacological inhibition of PIKfyve by Apilimod or Vacuolin-1 protects iNs from cell death by preventing endolysosomal damage rather than by directly reversing α-syn toxicity.

Discussion