Adaptive immunity relies on dendritic cell (DC) migration to transport antigens from tissues to lymph nodes. Galectins, a family of β-galactoside–binding proteins, control cell membrane organization, exerting crucial roles in multiple physiological processes. Here, we report a novel mechanism underlying cell polarity and uropod retraction by demonstrating that galectin-9 regulates basal and chemokine-driven DC migration in humans and mice. Galectin-9 depletion caused a defect in RhoA signaling that resulted in impaired cell rear contractility. Mechanistically, galectin-9 interacts with and organizes CD44 at the cell surface, in turn modulating RhoA binding to GEF-H1 and the initiation of downstream signaling. Analysis of DC motility in the 3D tumor microenvironment revealed galectin-9 is also required for DC recruitment and infiltration. Exogenous galectin-9 rescued the motility of tumor-immunocompromised human blood DCs, validating the physiological relevance of galectin-9 in DC migration. Our results identify galectin-9 as a necessary mechanistic component for DC motility by regulating cell polarity and contractility, and underscore its implications for DC-based immunotherapies.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cell type, paramount for the induction of immune responses against pathogens and tumor cells. DCs are endowed with the capacity to patrol their environment by active migration and to circulate between peripheral tissue and lymphoid organs, thereby linking innate and adaptive responses (Banchereau and Steinman, 1998; Delgado and Lennon-Dumenil, 2022). DC antigen uptake and maturation trigger the upregulation of specific surface proteins such as the chemokine receptor CCR7 that enables CCL19/CCL21-directed chemotaxis to secondary lymphoid organs and costimulatory molecules required for proper T cell activation (Acton et al., 2012; Randolph et al., 2005; Wculek et al., 2020). Rapid DC motility is crucial for their functions, which occurs in a so-called amoeboid manner utilizing a contractile uropod at the cell rear to squeeze through the extracellular matrix without significantly remodeling it (Lämmermann et al., 2008). Amoeboid migration is mediated by the Rho family of small GTPases, key regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics that generate a polarized and dynamic activity balance at the front and rear of the cell (Hind et al., 2016; Sanchez-Madrid and Serrador, 2009). Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA located at the leading front of the cell drive filamentous actin polymerization (Benvenuti et al., 2004; Lammermann et al., 2009) and directionality, while RhoA is the principal coordinator of the uropod, which choreographs actomyosin contractility (Lammermann et al., 2009; Sanchez-Madrid and Serrador, 2009; Wong et al., 2006). In addition, migrating DCs show enrichment of transmembrane adhesion molecules such as CD44 at the uropod, which link the actin cytoskeleton to the cell membrane, promoting actin polymerization and contraction in a RhoA-dependent manner (Bourguignon et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2014). Although DC migration dynamics are well characterized, the specific crosstalk between cell membrane events and intracellular cytoskeletal rearrangements that enable front-rear polarization and underlie amoeboid migration remain unresolved.

Galectins are a group of lectins that display a conserved affinity for β-galactoside modifications on cell surface proteins and lipids (Johannes et al., 2018). All galectins contain one or two carbohydrate recognition domains that allow them to simultaneously interact with various glycosylated binding partners, thereby modulating the expression, clustering, and activity of a large range of cell surface proteins (proteoglycans) (Johannes et al., 2018; Liu and Stowell, 2023; Querol Cano et al., 2024). In addition to their extracellular functions, many galectins are also found in the cytosol (Hong et al., 2021; Johannes et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2002; Santalla Mendez et al., 2023) and in the nucleus, where they participate in mRNA splicing (Coppin et al., 2017).

Galectin-9, encoded by the Lgals9 gene, is a ubiquitously expressed tandem-repeat galectin, known to exert numerous roles in cancer, infection, and inflammation (John and Mishra, 2016; Leffler et al., 2002; Tureci et al., 1997). Galectin-9–mediated functions are cell type–dependent and are dictated by the spatiotemporal expression of its binding partners. Illustrating its versatility, galectin-9 was first characterized as an eosinophil chemoattractant (Matsumoto et al., 1998), induces cell death and immune tolerance by binding T cell immunoglobulin-3 in T helper 1 (TH1) cells (Zhu et al., 2005), promotes the expansion of immunosuppressive macrophages (Arikawa et al., 2010) and monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (Dardalhon et al., 2010), and negatively regulates B cell receptor signaling (Cao et al., 2018; Giovannone et al., 2018). Contrary to these reports implying an immunosuppressive role, we and others have previously identified galectin-9 as a positive regulator of DC immune function (Dai et al., 2005; Li et al., 2023; Querol Cano et al., 2019; Santalla Mendez et al., 2023; Suszczyk et al., 2023). Nonetheless, the involvement of galectin-9 in immune cell migration has been insufficiently studied. Dengue virus–infected DCs upregulate galectin-9 expression, which associates with an increased ability to migrate toward CCL19, but whether galectin-9 is relevant for migration in nonpathological naïve DCs has not been addressed (Hsu et al., 2015). Furthermore, very few publications have provided compelling evidence of how endogenous lectins modulate cytoskeleton rearrangements that underlie cell migration, and thus, the mechanism(s) by which galectin-9 shapes cell motility are not delineated.

CD44 is a highly glycosylated single-chain transmembrane receptor with crucial roles in cell adhesion and migration (Senbanjo and Chellaiah, 2017). Illustrating this, CD44-mediated adhesion to hyaluronic acid on the lymphatic endothelium is necessary for DC trafficking to lymph nodes (Johnson et al., 2021). Intracellularly, the cytoplasmic tail of CD44 interacts with ezrin/radixin/moesin or ankyrin to modulate cytoskeletal activation in response to extracellular cues (Bourguignon, 2008). Although the signaling events that control CD44-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangements are well defined (Skandalis, 2023), the molecular mechanisms that regulate CD44 membrane distribution and whether that influences cell migration remain elusive. Interestingly, galectins are required for CD44 nanoclustering and endocytosis at the plasma membrane of epithelial cells, suggesting galectin-mediated interactions are relevant for its spatiotemporal membrane organization (Lakshminarayan et al., 2014).

Here, we show galectin-9 is required for basal and chemokine-driven DC migration in vitro and in vivo, indicating an evolutionarily conserved function for this lectin. We identified a reduction in RhoA activity, leading to a defect in uropod retraction and actin contractility upon galectin-9 depletion as the underlying mechanism. Importantly, we identified and characterized a functional interaction between galectin-9, CD44, and RhoA at the plasma membrane as an essential driver of DC migration that integrates signals from external stimuli and dictates subsequent cytoskeletal rearrangements. Exogenous galectin-9 was able to rescue the impaired migration capacity of tumor-immunocompromised human blood DCs, confirming the relevance of galectin-9 in DC motility and highlighting the physiological and translational relevance of our findings.

Results

Galectin-9 is required for DC migration

Actin polymerization regulates three-dimensional (3D) migration speed in DCs (Renkawitz et al., 2009), and our discovery that galectin-9 mediates actin contractility (Querol Cano et al., 2019) prompted us to study its involvement in governing DC migration. We investigated the functional consequence of galectin-9 depletion in DC migration using nontargeting (NT) siRNA-transfected and LGALS9 siRNA-transfected monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs), herewith referred to as wild-type (WT) and galectin-9 knockdown (gal9 KD) DCs, respectively. Galectin-9 expression was almost completely inhibited (75–90% reduction; Fig. S1, A and B), while CCR7, HLA-DR, CD80, CD83, and CD86 surface expression showed a similar upregulation upon stimulation demonstrating no impairment in DC maturation upon galectin-9 depletion (Fig. S1, C–E). We first analyzed WT and gal9 KD DC chemokine-driven migration toward CCL21 using a transwell chamber. Galectin-9–depleted DCs displayed an impaired migratory capacity (Fig. S1, F and G). Importantly, this migration defect was not attributed to the aberrant expression of CCL21 receptor CCR7, as this was equal in WT and gal9 KD DCs (Fig. S1 C). We also determined DC chemotactic migration in response to galectin-9 expression in 3D settings by employing transwell assays containing a collagen gel (Fig. 1 A). CCL21 induced DC migration in both WT and gal9 KD DCs, but this was significantly decreased in the latter for all donors analyzed (Fig. 1, B and C). Concomitantly, DCs were trapped in the collagen gel upon galectin-9 depletion (Fig. 1, D and E), demonstrating an involvement of galectin-9 in chemokine-driven DC migration. To discriminate whether galectin-9 depletion altered the migratory capacity of DCs and/or their chemotactic capacity, we employed custom glass 3D migration chambers (Wolf et al., 2013), in which we examined directionality of WT and gal9 KD DCs toward CCL21 (Fig. 1 F). In the absence of chemotaxis (−CCL21), the overall direction of each cell track should be random with an average angle of 90°, whereas a bias to lower angles indicates directionality toward CCL21 (Fig. 1 G). We report the bootstrapped difference of the average angle of gal9 KD cells relative to that of WT DCs (KD-WT) (Ho et al., 2019; Wortel et al., 2022). Validating our model, WT DCs moved in all directions in the absence of any stimulation but exhibited a clear directionality toward CCL21 (Fig. 1, G and H; and Fig. S1 H). Galectin-9–depleted DCs also displayed a directional migration toward the chemokine (Fig. 1, G and H; and Fig. S1 H), indicating that their defective motility is not due to an impairment in their chemotaxis ability.

Galectin-9 depletion impairs chemokine-driven DC migration independently of cell maturation. (A and B) Galectin-9 expression was assessed by western blot (A) or flow cytometry (B) 48 h in WT or gal9 KD moDCs. Immunoblot is representative of four independent experiments. In B, numbers in the inset indicate gMFI. Cells were gated based on their forward-side scatter after which cell clusters were gated out and only single cells were analyzed. WT, light gray population; gal9 KD moDCs, orange population. A black dotted line represents isotype control values. (C) CCR7 surface expression in moDCs treated as per (B). Graph is a representative donor out of three analyzed, and numbers in the inset indicate gMFI. (D and E) WT or gal9 KD moDCs were matured and levels of HLA-DR, CD80, CD86, and CD83 analyzed by flow cytometry. The graph depicts the mean ± SEM surface expression (gMFI) of four independent donors. (F) WT or gal9 KD moDCs were placed in the upper chamber of a transwell system and subjected to a CCL21 chemokine gradient. Migrated cells were collected at the bottom chamber 1, 2, and 4 h after seeding and measured by flow cytometry. Graphs show a representative donor of four independent donors analyzed. (G) Quantification of data shown in F. Graph shows mean percentage ± SEM of migratory DCs relative to the total number of seeded cells for each time point and genotype. An unpaired t test between WT and gal9 KD DCs was performed. (H) Overall angle to y axis (degrees) was computed for the overall displacement vector of WT or gal9 KD DCs subjected to CCL21 or nothing as a negative control. Each graph corresponds to one independent donor (labeled donor 1–4; 50 cells analyzed per donor). Horizontal lines represent means for untreated negative control (gray), WT (black), or gal9 KD DCs (red). Plots show the bootstrapped distribution (red) and 95% confidence interval (line segments) of the difference in average angle (gal9 KD-WT). n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05. gMFI, geometrical mean fluorescence intensity. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Galectin-9 depletion impairs chemokine-driven DC migration independently of cell maturation. (A and B) Galectin-9 expression was assessed by western blot (A) or flow cytometry (B) 48 h in WT or gal9 KD moDCs. Immunoblot is representative of four independent experiments. In B, numbers in the inset indicate gMFI. Cells were gated based on their forward-side scatter after which cell clusters were gated out and only single cells were analyzed. WT, light gray population; gal9 KD moDCs, orange population. A black dotted line represents isotype control values. (C) CCR7 surface expression in moDCs treated as per (B). Graph is a representative donor out of three analyzed, and numbers in the inset indicate gMFI. (D and E) WT or gal9 KD moDCs were matured and levels of HLA-DR, CD80, CD86, and CD83 analyzed by flow cytometry. The graph depicts the mean ± SEM surface expression (gMFI) of four independent donors. (F) WT or gal9 KD moDCs were placed in the upper chamber of a transwell system and subjected to a CCL21 chemokine gradient. Migrated cells were collected at the bottom chamber 1, 2, and 4 h after seeding and measured by flow cytometry. Graphs show a representative donor of four independent donors analyzed. (G) Quantification of data shown in F. Graph shows mean percentage ± SEM of migratory DCs relative to the total number of seeded cells for each time point and genotype. An unpaired t test between WT and gal9 KD DCs was performed. (H) Overall angle to y axis (degrees) was computed for the overall displacement vector of WT or gal9 KD DCs subjected to CCL21 or nothing as a negative control. Each graph corresponds to one independent donor (labeled donor 1–4; 50 cells analyzed per donor). Horizontal lines represent means for untreated negative control (gray), WT (black), or gal9 KD DCs (red). Plots show the bootstrapped distribution (red) and 95% confidence interval (line segments) of the difference in average angle (gal9 KD-WT). n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05. gMFI, geometrical mean fluorescence intensity. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS1.

Galectin-9 depletion reduces DC chemotactic migration. (A) Schematic representation of the transwell migration assay used. WT or gal9 KD DCs were seeded on a collagen gel in the top chamber of a transwell (5-µm porous membrane) and subjected to a CCL21 chemokine gradient. Migratory cells were collected after 24 h and quantified. (B) Day 3 moDCs were transfected with either a LGALS9 siRNA or a NT siRNA as a negative control, matured at day 6 for 48 h, and subjected to a transwell migration assay as per (A). Representative flow graphs from the migratory moDC fraction are shown. (C) Quantification of donors (black symbols) shown in B. Data show the percentage of moDCs that migrated relative to input, and lines connect matched WT and gal9 KD DCs. (D) Mature WT or gal9 KD moDCs were stained with CellTrace Far Red, seeded on top of a collagen layer overlaying a transwell chamber, and subjected to a CCL21 chemokine gradient. Cells were left to migrate for 24 h after which collagen gels were fixed and imaged by confocal microscopy. (E) Quantification of area fraction signal in WT and gal9 KD DC containing collagens over 10 z-planes from images shown in D from three independent donors (black symbols). (F) Schematic representation of the glass migration chamber used to analyze chemotaxis. WT or galectin-9–depleted moDCs were embedded in a collagen gel at the top of a glass chamber, and medium containing CCL21 was placed below. (G) Schematic of the migratory angle distribution in WT and gal9 KD DCs in the absence of any chemoattractant (- CCL21) or when subjected to CCL21 (+CCL21). Only WT cells are shown in the −CCL21 condition. (H) Overall angle to y axis (degrees) was computed for the overall displacement vector of WT or gal9 KD DCs subjected to CCL21 or nothing as a negative control. Each data point represents 1 cell track pooled from four independent donors with 50 cells analyzed per donor. Horizontal lines represent means for untreated negative control (gray), WT (black), or gal9 KD DCs (red). Plots show the bootstrapped distribution (red) and 95% confidence interval (line segments) of the difference in average angle (gal9 KD-WT). Unpaired Student’s t test was conducted to compare WT and gal9 KD cells. *P < 0.05.

Galectin-9 depletion reduces DC chemotactic migration. (A) Schematic representation of the transwell migration assay used. WT or gal9 KD DCs were seeded on a collagen gel in the top chamber of a transwell (5-µm porous membrane) and subjected to a CCL21 chemokine gradient. Migratory cells were collected after 24 h and quantified. (B) Day 3 moDCs were transfected with either a LGALS9 siRNA or a NT siRNA as a negative control, matured at day 6 for 48 h, and subjected to a transwell migration assay as per (A). Representative flow graphs from the migratory moDC fraction are shown. (C) Quantification of donors (black symbols) shown in B. Data show the percentage of moDCs that migrated relative to input, and lines connect matched WT and gal9 KD DCs. (D) Mature WT or gal9 KD moDCs were stained with CellTrace Far Red, seeded on top of a collagen layer overlaying a transwell chamber, and subjected to a CCL21 chemokine gradient. Cells were left to migrate for 24 h after which collagen gels were fixed and imaged by confocal microscopy. (E) Quantification of area fraction signal in WT and gal9 KD DC containing collagens over 10 z-planes from images shown in D from three independent donors (black symbols). (F) Schematic representation of the glass migration chamber used to analyze chemotaxis. WT or galectin-9–depleted moDCs were embedded in a collagen gel at the top of a glass chamber, and medium containing CCL21 was placed below. (G) Schematic of the migratory angle distribution in WT and gal9 KD DCs in the absence of any chemoattractant (- CCL21) or when subjected to CCL21 (+CCL21). Only WT cells are shown in the −CCL21 condition. (H) Overall angle to y axis (degrees) was computed for the overall displacement vector of WT or gal9 KD DCs subjected to CCL21 or nothing as a negative control. Each data point represents 1 cell track pooled from four independent donors with 50 cells analyzed per donor. Horizontal lines represent means for untreated negative control (gray), WT (black), or gal9 KD DCs (red). Plots show the bootstrapped distribution (red) and 95% confidence interval (line segments) of the difference in average angle (gal9 KD-WT). Unpaired Student’s t test was conducted to compare WT and gal9 KD cells. *P < 0.05.

Next, we studied the effect of galectin-9 in basal 3D migration using time-lapse microscopy (Fig. 2 A). As shown, the average migratory velocity was significantly impaired upon loss of galectin-9 (Fig. 2, B and C). In addition, we determined the mean square displacement (MSD) as a measurement of particle (i.e., a moDC) confinement within the collagen matrix (Fig. 2 D) and the Euclidean distance as the straight-line distance between the cell starting and end coordinates (Fig. 2 E). Both metrics substantially decreased in gal9 KD DCs compared with WT DCs. Individual cell tracks demonstrate the diminished motility of gal9 KD DCs away from their initial location within the 3D collagen matrix (Fig. 2 F). DCs activate and enhance their motility in the presence of stimuli such as tumors, which in turn secrete specific cytokines that direct DCs toward them (Song et al., 2024). Additional 3D migration assays in the presence of melanoma tumor spheroids were performed to investigate how galectin-9 depletion alters DC function in a physiologically relevant setup (Fig. 2 G). Time-lapse video microscopy analysis demonstrated that also in this context, galectin-9 depletion significantly hampered DC velocity by ∼40% (average speed of 4.1 µm/min in WT versus 2.4 µm/min in galectin-9 KD DCs) (Fig. 2 H), as well as their MSD and Euclidean distance (Fig. 2, I and J). This effect was not tumor cell line–specific as 3D assays performed with another melanoma cell line (BLM) yielded similar results (Fig. S2, A and B). Concomitant with a diminished cell velocity, gal9 KD DCs were found in lower numbers in the collagen surrounding the tumor spheroid and displayed a decreased infiltration rate compared with their WT counterparts (Fig. 2 K). WT DCs enhanced their migratory capacity both upon maturation and when present in the vicinity of a tumor, whereas this increase was only marginal in gal9 KD DCs, suggesting that galectin-9 has a broad impact on the capacity of DCs to migrate (Fig. S2, C–E). Next, we sought to investigate whether galectin-9 function in DC migration was evolutionarily conserved using in situ migration assays on bone marrow–derived DCs (BMDCs) from WT and galectin-9−/− (KO) mice (Fig. 3 A). WT and galectin-9 KO DCs were labeled with far-red or violet carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dyes, mixed in equal numbers, and co-injected into the same footpad or tail vein in host mice (Fig. 3 B). Donor DCs arriving in the draining popliteal and inguinal lymph nodes, respectively, were enumerated 48 h later via flow cytometry. To rule out any involvement of galectin-9 present in the recipient animal, both WT and galectin KO were employed as host mice. The number of migratory galectin-9−/− BMDCs was significantly reduced compared to WT DCs irrespective of the host genotype (galectin-9 WT or KO) (Fig. 3, C and D). Similar results were obtained in experiments in which violet-labeled WT and far-red–labeled galectin-9 KO BMDCs were employed, ruling out any specific effect of the fluorescent dyes on migration (Fig. 3, C and D). In addition, calculated homing indexes to inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes showed that WT DC motility was around 1.5–2 times higher than that observed for gal9 KO DCs irrespective of the cell labeling or the genotype of the host mice (Fig. 3 E). CCL21 transwell chemotactic assays demonstrated an impairment in murine DC migration upon loss of galectin-9, confirming an evolutionary role of galectin-9 in driving DC motility (Fig. 3 F).

Galectin-9 depletion reduces DC 3D migration. (A) Left: schematic representation of the 3D collagen migration assay used. Right: representative single-cell tracking paths of WT or gal9 KD moDCs embedded in a 3D collagen matrix. Lines represent the tracking path covered by each cell from their initial position (time = 0 min). Scale bar = 150 µm. (B) Mature WT or gal9 KD moDCs were embedded within a 3D collagen matrix as per (A). The mean cell velocity of a representative donor is shown. (C–E) Mean ± SEM cell velocity (C), MSD (D), and Euclidean distance (E) of four independent donors. 20 cells were analyzed per donor and transfection. Lines in C connect matched WT and gal9 KD moDCs. Graph in E depicts relative Euclidean distance in gal9 KD moDCs after 60 min of tracking with respect to control cells. (F) Individual trajectory plots of WT and gal9 KD moDCs of one representative donor out of four analyzed. End points of tracks are indicated by red dots. The black line indicates the overall movement in x and y direction (µm). (G) Representative single-cell tracking paths of WT or gal9 KD moDCs embedded in a 3D collagen matrix together with a MEL624 malignant melanoma spheroid. Dots indicate cell position at the specified time point, whereas lines represent the tracking path covered by each cell from their initial position (time = 0 min). Scale bar = 150 µm. (H–J) Cell velocity (H), the MSD (I), and the Euclidean distance migrated after 1 h (J) are depicted. Data represent the mean value ± SEM of three independent donors. The Euclidean distance is depicted as the mean value for galectin-9–depleted moDCs relative to the control group after 60 min of tracking. A one-way t test was performed. In (H), lines connect matched WT and gal9 KD moDCs. (K) Collagen matrices from (G) were fixed and stained for actin, and the number of DCs surrounding (left graph) and infiltrated (right graph) in the spheroid was calculated. Measurements were taken at the same tumor spheroid z-plane across conditions. Images are representative of the tumor spheroid and surrounding DCs. Graphs show the mean ± SEM of four independent donors. Unpaired Student’s t test was conducted to compare WT and gal9 KD cells except for E and J, where a one-way t test was performed. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

Galectin-9 depletion reduces DC 3D migration. (A) Left: schematic representation of the 3D collagen migration assay used. Right: representative single-cell tracking paths of WT or gal9 KD moDCs embedded in a 3D collagen matrix. Lines represent the tracking path covered by each cell from their initial position (time = 0 min). Scale bar = 150 µm. (B) Mature WT or gal9 KD moDCs were embedded within a 3D collagen matrix as per (A). The mean cell velocity of a representative donor is shown. (C–E) Mean ± SEM cell velocity (C), MSD (D), and Euclidean distance (E) of four independent donors. 20 cells were analyzed per donor and transfection. Lines in C connect matched WT and gal9 KD moDCs. Graph in E depicts relative Euclidean distance in gal9 KD moDCs after 60 min of tracking with respect to control cells. (F) Individual trajectory plots of WT and gal9 KD moDCs of one representative donor out of four analyzed. End points of tracks are indicated by red dots. The black line indicates the overall movement in x and y direction (µm). (G) Representative single-cell tracking paths of WT or gal9 KD moDCs embedded in a 3D collagen matrix together with a MEL624 malignant melanoma spheroid. Dots indicate cell position at the specified time point, whereas lines represent the tracking path covered by each cell from their initial position (time = 0 min). Scale bar = 150 µm. (H–J) Cell velocity (H), the MSD (I), and the Euclidean distance migrated after 1 h (J) are depicted. Data represent the mean value ± SEM of three independent donors. The Euclidean distance is depicted as the mean value for galectin-9–depleted moDCs relative to the control group after 60 min of tracking. A one-way t test was performed. In (H), lines connect matched WT and gal9 KD moDCs. (K) Collagen matrices from (G) were fixed and stained for actin, and the number of DCs surrounding (left graph) and infiltrated (right graph) in the spheroid was calculated. Measurements were taken at the same tumor spheroid z-plane across conditions. Images are representative of the tumor spheroid and surrounding DCs. Graphs show the mean ± SEM of four independent donors. Unpaired Student’s t test was conducted to compare WT and gal9 KD cells except for E and J, where a one-way t test was performed. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

Galectin-9 depletion diminishes DC 3D migration. (A and B) WT or gal9 KD moDCs were matured and embedded within a 3D collagen matrix containing either a MEL624 or a BLM melanoma cell spheroid. The median cell velocity (A) and the MSD (B) were calculated. Data represent the mean value ± SEM of a representative donor. At least 20 cells were analyzed per condition. (C–E) Migration pattern of WT or gal9 KD moDCs either immature (at day 6 of DC differentiation), mature (at day 8), and mature in the presence of a tumor spheroid (at day 8) was analyzed for one representative donor. The median cell velocity (C), the MSD (D), and the Euclidean distance reached after 60 min of tracking (E) were assessed. In D, m = mature DCs; i = immature DCs. Graphs represent the mean value ± SEM of one representative donor. At least 25 cells were analyzed per condition. One-way ANOVA was performed to compare WT and gal9 KD moDCs. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Galectin-9 depletion diminishes DC 3D migration. (A and B) WT or gal9 KD moDCs were matured and embedded within a 3D collagen matrix containing either a MEL624 or a BLM melanoma cell spheroid. The median cell velocity (A) and the MSD (B) were calculated. Data represent the mean value ± SEM of a representative donor. At least 20 cells were analyzed per condition. (C–E) Migration pattern of WT or gal9 KD moDCs either immature (at day 6 of DC differentiation), mature (at day 8), and mature in the presence of a tumor spheroid (at day 8) was analyzed for one representative donor. The median cell velocity (C), the MSD (D), and the Euclidean distance reached after 60 min of tracking (E) were assessed. In D, m = mature DCs; i = immature DCs. Graphs represent the mean value ± SEM of one representative donor. At least 25 cells were analyzed per condition. One-way ANOVA was performed to compare WT and gal9 KD moDCs. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Galectin-9 function in DC migration is conserved in vivo. (A) Scheme depicting experimental setup. WT and galectin-9−/− BMDCs were stained with far-red or violet CFSE dyes, mixed in equal numbers, and injected into the footpad or tail vein of donor mice. 48 h later, draining lymph nodes were isolated and donor BMDCs enumerated by flow cytometry. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots depicting the cellular mixtures injected into recipient mice. In mixture A, WT BMDCs were stained with far-red CFSE and galectin-9−/− cells received violet CFSE. For mixture B, colors were interchanged to discard any effect of the dye in cell migration. (C and D) DC mixtures from (B) were injected into WT (C) and galectin-9 KO (D) host mice. Data depict the percentage of migratory donor BMDCs ± SEM. Each symbol represents values obtained for one draining lymph node. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by the Holm–Sidak multiple comparisons test. (E) Homing index of WT over galectin-9 KO DCs for each of the injected cell mixtures and host mouse genotype. The homing index was calculated using the following formula: (% far-red signal in tissue/% violet signal in tissue)/(% far-red signal in input/% violet signal in input). Each mixture was injected three times into either WT or gal9 KO host mice. The homing index is depicted. (F) BMDCs obtained in A were also subjected to a chemokine transwell assay in the presence or absence of chemokine CCL21. Data show the percentage of moDCs that migrated relative to input. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0001.

Galectin-9 function in DC migration is conserved in vivo. (A) Scheme depicting experimental setup. WT and galectin-9−/− BMDCs were stained with far-red or violet CFSE dyes, mixed in equal numbers, and injected into the footpad or tail vein of donor mice. 48 h later, draining lymph nodes were isolated and donor BMDCs enumerated by flow cytometry. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots depicting the cellular mixtures injected into recipient mice. In mixture A, WT BMDCs were stained with far-red CFSE and galectin-9−/− cells received violet CFSE. For mixture B, colors were interchanged to discard any effect of the dye in cell migration. (C and D) DC mixtures from (B) were injected into WT (C) and galectin-9 KO (D) host mice. Data depict the percentage of migratory donor BMDCs ± SEM. Each symbol represents values obtained for one draining lymph node. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by the Holm–Sidak multiple comparisons test. (E) Homing index of WT over galectin-9 KO DCs for each of the injected cell mixtures and host mouse genotype. The homing index was calculated using the following formula: (% far-red signal in tissue/% violet signal in tissue)/(% far-red signal in input/% violet signal in input). Each mixture was injected three times into either WT or gal9 KO host mice. The homing index is depicted. (F) BMDCs obtained in A were also subjected to a chemokine transwell assay in the presence or absence of chemokine CCL21. Data show the percentage of moDCs that migrated relative to input. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0001.

Galectin-9 is located both in the cytosol and extracellularly (membrane-bound) in DCs (Querol Cano et al., 2019). To gain further insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying galectin-9 regulation of DC migration, we cultured gal9 KD DCs with exogenous recombinant galectin-9 protein (gal9 KD + rGal9 DCs). Analysis of galectin-9 expression revealed that exogenous protein restored surface-bound levels of galectin-9, while the cytosolic pool remained mostly depleted (Fig. 4 A). We next embedded WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD +rGal9 DCs in 3D collagen matrices to characterize their migration capacities. Restoring surface galectin-9 levels rescued the migration deficiency observed in gal9 KD DCs, and no differences were observed in the velocity or the MSD between WT and gal9 KD + rGal9 DCs (Fig. 4, B and C, respectively). Moreover, individual cell tracks illustrate the ability of DCs to migrate upon restoring galectin-9 levels as gal9 KD + rGal9 DCs are indistinguishable from their WT counterparts (Fig. 4 D). Interestingly, the exogenous addition of galectin-9 rescued DC migration also after short incubations confirming the fundamental role of galectin-9 in driving DC migration (Fig. 4 E). Treatment with rGal9 did not enhance WT DC migration in 3D collagen matrices indicating saturating endogenous galectin-9 levels in WT cells and ruling out any contamination of the recombinant galectin-9 protein (Fig. 4 F).

DC migration relies on membrane-bound galectin-9 fraction. (A) moDCs were transfected with LGALS9 or a NT siRNA. 48 h after transfection, gal9 KD cells were treated with 1 µg/ml recombinant galectin-9 (rGal9) protein (gal9 KD + rGal9) or nothing as a negative control for 24–48 h. Surface only (left) and total (right) galectin-9 depletion and treatment with exogenous protein were confirmed by flow cytometry 48 h after treatment. Gray population = WT; orange population = gal9 KD; black population = gal9 KD + rGal9; dotted line = isotype control. Numbers in the inset indicate gMFI. (B and C) moDCs treated as per (A) were embedded in 3D collagen matrices followed by time-lapse microscopy imaging to individually track cell migration. At least 20 cells were analyzed for each donor and transfection or treatment. (B) Violin plot showing average cell velocity of six individual donors (black symbols). Lines connect paired donors. (C) Average MSD ± SEM of five individual donors. (D) Individual trajectories of WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs. End points of tracks are indicated by red dots. Data show a representative donor out of six analyzed. (E) WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD moDCs treated with rGal9 for either 3, 24, or 48 h were embedded in a 3D collagen matrix, and their velocity was calculated. The graph depicts average velocity ± SEM for one representative donor out of 4 analyzed. (F) WT and gal9 KD moDCs were treated with rGal9 for 3 h prior to being embedded into 3D collagen matrices, and cell velocity was determined. Data show mean cell velocity ± SEM of three independent experiments (gray symbols). One-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest correction (B, E, and F) or a two-way ANOVA (C) was conducted between WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDC conditions. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. gMFI, geometrical mean fluorescence intensity.

DC migration relies on membrane-bound galectin-9 fraction. (A) moDCs were transfected with LGALS9 or a NT siRNA. 48 h after transfection, gal9 KD cells were treated with 1 µg/ml recombinant galectin-9 (rGal9) protein (gal9 KD + rGal9) or nothing as a negative control for 24–48 h. Surface only (left) and total (right) galectin-9 depletion and treatment with exogenous protein were confirmed by flow cytometry 48 h after treatment. Gray population = WT; orange population = gal9 KD; black population = gal9 KD + rGal9; dotted line = isotype control. Numbers in the inset indicate gMFI. (B and C) moDCs treated as per (A) were embedded in 3D collagen matrices followed by time-lapse microscopy imaging to individually track cell migration. At least 20 cells were analyzed for each donor and transfection or treatment. (B) Violin plot showing average cell velocity of six individual donors (black symbols). Lines connect paired donors. (C) Average MSD ± SEM of five individual donors. (D) Individual trajectories of WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs. End points of tracks are indicated by red dots. Data show a representative donor out of six analyzed. (E) WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD moDCs treated with rGal9 for either 3, 24, or 48 h were embedded in a 3D collagen matrix, and their velocity was calculated. The graph depicts average velocity ± SEM for one representative donor out of 4 analyzed. (F) WT and gal9 KD moDCs were treated with rGal9 for 3 h prior to being embedded into 3D collagen matrices, and cell velocity was determined. Data show mean cell velocity ± SEM of three independent experiments (gray symbols). One-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest correction (B, E, and F) or a two-way ANOVA (C) was conducted between WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDC conditions. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. gMFI, geometrical mean fluorescence intensity.

Overall, our results demonstrate that galectin-9 is required for both basal and chemokine-directed migration in DCs. Furthermore, this function appears to be evolutionarily conserved and is likely mediated by the surface-bound fraction of the lectin.

Galectin-9 controls RhoA-mediated contractility in DCs

To mechanistically resolve how galectin-9 dictates DC migration, we morphologically characterized migratory WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD +rGal9 DCs in a 3D collagen matrix. WT cells contracted the uropod with concomitant forward movement (Fig. 5 A and Video 1), whereas gal9 KD DCs were defective in their ability to contract the cell rear (Fig. 5, A and B; and Video 2). Remarkably, the addition of exogenous galectin-9 protein (rGal9) rescued DC contractility and the uropod could not be detected for abnormal lengths of time in gal9 KD + rGal9 DCs (Fig. 5, A and B; and Video 3). Interestingly, DC elongation was not found to depend on galectin-9 expression (Fig. 5 C), also implying that galectin-9 does not dictate long-term cell length and may be implicated in driving short-lived, dynamic changes in cell shape. Anterograde protrusion at the cell front is functionally dissociated from the retrograde contractility forces that mediate uropod retraction (Lammermann et al., 2008). We did not observe qualitative differences in the leading-edge protrusion formation between WT and gal9 KD DCs, and quantification of the cell front velocity also highlighted no significant differences between both conditions. This is in contrast to the velocity at the cell rear, which was found to be significantly lower upon galectin-9 depletion, in agreement with a retraction defect in those cells (Fig. 5 D).

Galectin-9 regulates uropod contractility. (A) Time-lapse sequence of representative WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD+rGal9 moDCs migrating in a 3D collagen gel. Scale bar = 50 µm. Scale bar = 10 µm. (B and C) Mean ± SEM duration (min) of uropod presence (B) and cell elongation factor (C) in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs for four independent donors (black dots). At least 20 cells were analyzed for each donor and condition. (D) Velocity of the front or rear in WT and gal9 KD moDCs. Graphs depict the mean ± SEM for four independent donors (individual cells represented by black symbols). (E) Total lysates from WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD +rGal9 moDCs were subjected to western blot and galectin-9 and total RhoA expression analyzed. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Immunoblot is representative of four independent donors. (F) Levels of active (GTP-bound) RhoA in WT and gal9 KD moDCs detected by immunoblotting. Rhotekin beads alone were used as a negative control (lanes 2 and 3). (G) Quantification of data shown in F. The graph depicts relative active RhoA content in galectin-9–depleted DCs (gal9 KD) compared with relevant WT control for three independent experiments. (H) WT or gal9 KD moDCs were embedded in 3D collagen matrices prior to being treated with a RhoA activator or PBS as a negative control. The graph depicts mean cell velocity ± SEM for four independent donors (black symbols). At least 20 cells were analyzed for each donor and condition. (I) Individual trajectory plots of WT and gal9 KD DCs untreated or treated with the RhoA activator of one representative donor out of four analyzed. End track points are indicated by red dots. The black line indicates the overall movement in x and y direction (µm). One-way ANOVA test with a Bonferroni posttest correction was conducted to test significance. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Galectin-9 regulates uropod contractility. (A) Time-lapse sequence of representative WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD+rGal9 moDCs migrating in a 3D collagen gel. Scale bar = 50 µm. Scale bar = 10 µm. (B and C) Mean ± SEM duration (min) of uropod presence (B) and cell elongation factor (C) in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs for four independent donors (black dots). At least 20 cells were analyzed for each donor and condition. (D) Velocity of the front or rear in WT and gal9 KD moDCs. Graphs depict the mean ± SEM for four independent donors (individual cells represented by black symbols). (E) Total lysates from WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD +rGal9 moDCs were subjected to western blot and galectin-9 and total RhoA expression analyzed. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Immunoblot is representative of four independent donors. (F) Levels of active (GTP-bound) RhoA in WT and gal9 KD moDCs detected by immunoblotting. Rhotekin beads alone were used as a negative control (lanes 2 and 3). (G) Quantification of data shown in F. The graph depicts relative active RhoA content in galectin-9–depleted DCs (gal9 KD) compared with relevant WT control for three independent experiments. (H) WT or gal9 KD moDCs were embedded in 3D collagen matrices prior to being treated with a RhoA activator or PBS as a negative control. The graph depicts mean cell velocity ± SEM for four independent donors (black symbols). At least 20 cells were analyzed for each donor and condition. (I) Individual trajectory plots of WT and gal9 KD DCs untreated or treated with the RhoA activator of one representative donor out of four analyzed. End track points are indicated by red dots. The black line indicates the overall movement in x and y direction (µm). One-way ANOVA test with a Bonferroni posttest correction was conducted to test significance. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

Representative time-lapse confocal microscopy of a WT moDC randomly migrating on 3D collagen matrices. The movie was acquired in a BD Pathway 855 spinning disk confocal microscope (BD Bioscience) using a 10 × 0.3 NA air objective equipped with cameras and custom-built climate chambers (37°C, 5% CO2, humidified). Images were acquired with a time interval of 2 min.

Representative time-lapse confocal microscopy of a WT moDC randomly migrating on 3D collagen matrices. The movie was acquired in a BD Pathway 855 spinning disk confocal microscope (BD Bioscience) using a 10 × 0.3 NA air objective equipped with cameras and custom-built climate chambers (37°C, 5% CO2, humidified). Images were acquired with a time interval of 2 min.

Representative time-lapse confocal microscopy of a gal9 KD moDC randomly migrating on 3D collagen matrices. The movie was acquired in a BD Pathway 855 spinning disk confocal microscope (BD Bioscience) using a 10 × 0.3 NA air objective equipped with cameras and custom-built climate chambers (37°C, 5% CO2, humidified). Images were acquired with a time interval of 2 min.

Representative time-lapse confocal microscopy of a gal9 KD moDC randomly migrating on 3D collagen matrices. The movie was acquired in a BD Pathway 855 spinning disk confocal microscope (BD Bioscience) using a 10 × 0.3 NA air objective equipped with cameras and custom-built climate chambers (37°C, 5% CO2, humidified). Images were acquired with a time interval of 2 min.

Representative time-lapse confocal microscopy of a galectin-9 KD moDC pretreated with rGal9 protein for 48 h randomly migrating on 3D collagen matrices. The movie was acquired in a BD Pathway 855 spinning disk confocal microscope (BD Bioscience) using a 10 × 0.3 NA air objective equipped with cameras and custom-built climate chambers (37°C, 5% CO2, humidified). Images were acquired with a time interval of 2 min.

Representative time-lapse confocal microscopy of a galectin-9 KD moDC pretreated with rGal9 protein for 48 h randomly migrating on 3D collagen matrices. The movie was acquired in a BD Pathway 855 spinning disk confocal microscope (BD Bioscience) using a 10 × 0.3 NA air objective equipped with cameras and custom-built climate chambers (37°C, 5% CO2, humidified). Images were acquired with a time interval of 2 min.

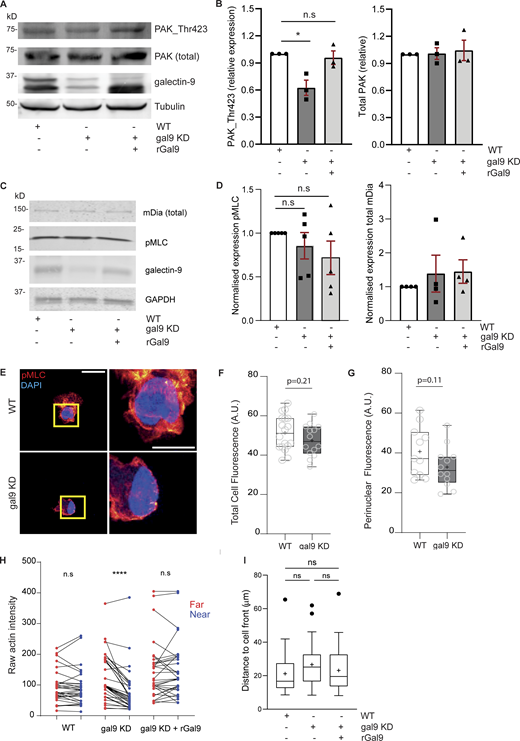

RhoA activity governs uropod contraction (Hind et al., 2016; Meili and Firtel, 2003), and thus, we next examined whether RhoA-mediated signaling was altered upon galectin-9 depletion. Although total RhoA levels did not differ across all conditions (Fig. 5 E), RhoA GTPase activity was markedly decreased in gal9 KD DCs (Fig. 5, F and G) in agreement with the aforementioned impairment in uropod retraction. Pretreatment of gal9 KD DCs with the RhoA activator II prior to being embedded into collagen gels restored their impairment in cell velocity (Fig. 5 H). Individual cell tracks demonstrate the rescue in DC migration upon restoration of RhoA activity, confirming 3D migration defect induced by galectin-9 depletion is due to defective RhoA activation (Fig. 5 I). To further confirm the link between galectin-9 and RhoA, we sought to investigate which genes positively correlate with lgals9 expression and the pathways they mediate. We obtained a list of the top 50 genes correlating with lgals9 using the ULI RNA-seq dataset (GSE109125) from the Immunological Genome Project (ImmGen) and performed a functional pathway enrichment analysis using the Reactome dataset (Griss et al., 2020) (Fig. S3 A). Data obtained showed a significant enrichment in both the Rho GTPase effectors and signaling by Rho GTPase pathways confirming a correlation between galectin-9 and RhoA activity (Fig. S3 B). Reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) (Siwak et al., 2019) performed against >450 key functional proteins on WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 DC whole-cell lysates revealed a striking decline in either the expression or activity of proteins involved in cytoskeleton rearrangements in gal9 KD cells compared with WT or gal9 KD + rGal9 DCs (Fig. 6 A). Remarkably, minimal differences were detected between WT and gal9 KD + rGal9 DCs, indicating that treatment with exogenous galectin-9 protein rescues the DC signaling signature (Fig. 6 A). Enrichment pathway analysis (Zhou et al., 2019) performed on the differentially expressed proteins confirmed galectin-9 is a positive regulator of cell motility (Fig. 6 B). Validating our analysis, cytokine signaling was also found to be positively regulated in WT compared with gal9 KD DCs, which we have previously reported (Santalla Mendez et al., 2023). RPPA analysis revealed that the active form of P21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) (PAK_Thr423), an activating Ser/Thr kinase downstream of RhoA, is downregulated in gal9 KD DCs, whereas treatment with exogenous galectin-9 protein (gal9 KD + rGal9 DCs) rescued its levels to those found in WT cells (Fig. 6 A). Total levels of PAK1 did not differ across conditions, suggesting galectin-9 is not involved in regulating its expression. Western blot analysis of phosphorylated and total PAK1 levels in multiple donors validated our RPPA data and RhoA-mediated signaling to be differentially activated in response to galectin-9 cellular levels (Fig. S4, A and B). Through immunoblotting of 2D-seeded moDCs, we were unable to observe differences in total phospho-myosin light chain (pMLC) or mDia expression upon galectin-9 depletion with or without rGal9 treatment (Fig. S4, C and D). Immunofluorescence against pMLC showed subtle (not significant) differences in pMLC localization or intensity between WT and gal9 KD moDCs seeded onto coverslips (Fig. S4, E–G), suggesting that changes in pMLC might be masked by stiffness of the 2D culture (Yang et al., 2017; Lee and Kumar., 2016; Caswell and Zech., 2018). Since western blot only provides the average total expression and to circumvent mechanoresponses induced by plastic or glass-adhered cells, we employed Airyscan microscopy of collagen-embedded moDCs to examine spatial differences in MLC phosphorylation with respect to galectin-9 expression in 3D. Myosin II activity prominently accumulated at the rear of migrating WT DCs, but this was largely abrogated upon galectin-9 depletion, indicative of impaired generation of contractile forces (Fig. 6 C). In agreement with the rescue previously observed in uropod retraction, treatment with rGal9 was sufficient to restore pMLC activity at the cell rear of galectin-9–depleted DCs (Fig. 6 C). We further characterized the architecture of the actomyosin cytoskeleton in collagen-embedded DCs by structured illumination microscopy (SIM) super-resolution and Airyscan microscopy and observed a decreased F-actin intensity at the cell rear in gal9 KD compared with WT DCs (Fig. 6 D, Fig. S4 H, and Video 4). Cell-wide line profile analysis of actin staining revealed that actin intensity was specifically reduced at the cell rear in gal9 KD cells compared with WT and gal9 KD treated with rGal9 counterparts, while the actin intensity at the leading edge was slightly higher in gal9 KD cells, further suggesting a specific rear retraction defect (Fig. 6 E). Interestingly, the cell rear in gal9 KD DCs was further away from the edge of the nucleus than in WT and rGal9-treated DCs further substantiating a rear retraction defect upon galectin-9 depletion (Fig. 6 F and Fig. S4 I). Overall, our data show that galectin-9 regulates uropod contractility by modulating RhoA retrograde activity, directly altering the architecture and dynamics of the actomyosin cytoskeleton at the cell rear.

RhoGTPase-mediated pathways positively correlate with lgals9 expression. (A) 50 genes that positively correlated to lgals9 gene across all immune cell types (GSE109125 dataset) grouped by secondary correlation. (B) Functional pathway enrichment analysis (Reactome dataset). Data are shown as −log10 of the adjusted P value.

RhoGTPase-mediated pathways positively correlate with lgals9 expression. (A) 50 genes that positively correlated to lgals9 gene across all immune cell types (GSE109125 dataset) grouped by secondary correlation. (B) Functional pathway enrichment analysis (Reactome dataset). Data are shown as −log10 of the adjusted P value.

RhoA downstream signaling is impaired in galectin-9–depleted DCs. (A) Heat map of proteins involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements analyzed by RPPA. Whole-cell lysates obtained from mature WT, gal9 KD, or gal-9 KD +rGal9 DCs were denatured, arrayed on nitrocellulose-coated slides, and probed with antibodies against the specified protein targets. Data shown represent mean protein expression normalized against the loading control. (B) Metascape pathway enrichment analysis from all proteins found to be differentially regulated by RPPA between WT and gal9 KD moDCs. (C and D) WT, gal9 KD, or gal9 KD + rGal9 mature DCs were embedded in 3D collagen gels and stained for pMLC, actin (phalloidin), and nucleus (Hoechst). Box-and-whisker plots show mean (as +) pMLC (C) or actin (D) intensity ratio at the rear over the front of the cell (based on the nucleus localization) for 4 independent donors (10–15 cells analyzed per donor). Whiskers are generated using the Tukey method. Representative high-resolution Airyscan images of WT, gal9 KD, or gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs are shown. Scale bar = 10 µm. Two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons was performed in all panels. (E) Average actin intensity for the entire width of WT (black), gal9 KD (red), and gal9 KD + rGal9 (blue) moDCs at each position forward from the rearmost point of the cell (left) and backward from the frontmost point of the cell (right) for the rear and front 25 μm. 15 cells were analyzed across three independent donors with bar representing SEM; all values were normalized to the maximum actin intensity of each cell. (F) Distance of the nucleus to the rear of the cell in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs. Box-and-whisker plot shows mean (as +) nuclear distance for four independent donors (10–15 cells analyzed per donor). Whiskers are generated using the Tukey method. Representative high-resolution Airyscan images of WT, gal9 KD, or gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs stained for actin (phalloidin) and nucleus (Hoechst) are shown. Scale bar = 10 µm. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s., P > 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01; ****P < 0.001.

RhoA downstream signaling is impaired in galectin-9–depleted DCs. (A) Heat map of proteins involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements analyzed by RPPA. Whole-cell lysates obtained from mature WT, gal9 KD, or gal-9 KD +rGal9 DCs were denatured, arrayed on nitrocellulose-coated slides, and probed with antibodies against the specified protein targets. Data shown represent mean protein expression normalized against the loading control. (B) Metascape pathway enrichment analysis from all proteins found to be differentially regulated by RPPA between WT and gal9 KD moDCs. (C and D) WT, gal9 KD, or gal9 KD + rGal9 mature DCs were embedded in 3D collagen gels and stained for pMLC, actin (phalloidin), and nucleus (Hoechst). Box-and-whisker plots show mean (as +) pMLC (C) or actin (D) intensity ratio at the rear over the front of the cell (based on the nucleus localization) for 4 independent donors (10–15 cells analyzed per donor). Whiskers are generated using the Tukey method. Representative high-resolution Airyscan images of WT, gal9 KD, or gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs are shown. Scale bar = 10 µm. Two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons was performed in all panels. (E) Average actin intensity for the entire width of WT (black), gal9 KD (red), and gal9 KD + rGal9 (blue) moDCs at each position forward from the rearmost point of the cell (left) and backward from the frontmost point of the cell (right) for the rear and front 25 μm. 15 cells were analyzed across three independent donors with bar representing SEM; all values were normalized to the maximum actin intensity of each cell. (F) Distance of the nucleus to the rear of the cell in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs. Box-and-whisker plot shows mean (as +) nuclear distance for four independent donors (10–15 cells analyzed per donor). Whiskers are generated using the Tukey method. Representative high-resolution Airyscan images of WT, gal9 KD, or gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs stained for actin (phalloidin) and nucleus (Hoechst) are shown. Scale bar = 10 µm. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s., P > 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01; ****P < 0.001.

Galectin-9 depletion alters actomyosin cytoskeleton. (A) Total lysates from WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs were subjected to western blot and total PAK1, PAK_Thr423, and galectin-9 protein expression analyzed. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments. (B) Quantification of mean ± SEM of PAK1_Thr423 and total PAK1 content normalized to corresponding tubulin for three independent donors. One-way ANOVA was performed. (C) Total lysates from WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD +rGal9 moDCs seeded onto 6-well plates were subjected to western blot and total mDia, pMLC (Ser19), and galectin-9 expression analyzed. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Immunoblot is representative of five independent experiments. (D) Quantification of normalized mDia and pMLC content shown in C. A one-sample t test was performed. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05. (E) WT or gal9 KD mature DCs were seeded onto coverslips and stained for pMLC and nucleus (DAPI). ROI in the left panel (yellow square) is depicted in the zoomed right panels. Scale bar = 10 µm; insets = 10 µm. (F and G) Quantification of data shown in (E). Box-and-whisker plots show mean (as +) pMLC intensity ratio in the whole cell (F) or at the perinuclear region (G) for two independent donors (10–15 cells analyzed per donor). Whiskers are generated using the Tukey method. Significance was determined by an unpaired t test. (H) Pairwise comparison of actin intensity at the cell front (red) and rear (blue) of 30 WT, gal9 KD, or gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs from three independent donors, corresponding to rear/front ratio analysis shown in Fig. 6 D. (I) Distance of the nucleus to the front of the cell in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs. The box-and-whisker plot shows mean (as +) nuclear distance for four independent donors (10–15 cells analyzed per donor). Whiskers are generated using the Tukey method. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s > 0.05. In H, two-tailed paired Student’s parametric t test was used. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Galectin-9 depletion alters actomyosin cytoskeleton. (A) Total lysates from WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs were subjected to western blot and total PAK1, PAK_Thr423, and galectin-9 protein expression analyzed. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments. (B) Quantification of mean ± SEM of PAK1_Thr423 and total PAK1 content normalized to corresponding tubulin for three independent donors. One-way ANOVA was performed. (C) Total lysates from WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD +rGal9 moDCs seeded onto 6-well plates were subjected to western blot and total mDia, pMLC (Ser19), and galectin-9 expression analyzed. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Immunoblot is representative of five independent experiments. (D) Quantification of normalized mDia and pMLC content shown in C. A one-sample t test was performed. n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05. (E) WT or gal9 KD mature DCs were seeded onto coverslips and stained for pMLC and nucleus (DAPI). ROI in the left panel (yellow square) is depicted in the zoomed right panels. Scale bar = 10 µm; insets = 10 µm. (F and G) Quantification of data shown in (E). Box-and-whisker plots show mean (as +) pMLC intensity ratio in the whole cell (F) or at the perinuclear region (G) for two independent donors (10–15 cells analyzed per donor). Whiskers are generated using the Tukey method. Significance was determined by an unpaired t test. (H) Pairwise comparison of actin intensity at the cell front (red) and rear (blue) of 30 WT, gal9 KD, or gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs from three independent donors, corresponding to rear/front ratio analysis shown in Fig. 6 D. (I) Distance of the nucleus to the front of the cell in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs. The box-and-whisker plot shows mean (as +) nuclear distance for four independent donors (10–15 cells analyzed per donor). Whiskers are generated using the Tukey method. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s > 0.05. In H, two-tailed paired Student’s parametric t test was used. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS4.

Representative actin staining (phalloidin) for WT (left cell) and galectin-9–depleted (right cell) DCs using a Nikon Ti2 spinning disk confocal microscope with Crest Optics SIM module for super-resolution imaging. Images were captured using a Teledyne Photometrics Kinetix camera through a 100×/1.45 DIC Plan Apo oil-immersion objective.

Representative actin staining (phalloidin) for WT (left cell) and galectin-9–depleted (right cell) DCs using a Nikon Ti2 spinning disk confocal microscope with Crest Optics SIM module for super-resolution imaging. Images were captured using a Teledyne Photometrics Kinetix camera through a 100×/1.45 DIC Plan Apo oil-immersion objective.

The transmembrane adhesion glycoprotein CD44 has been postulated to mediate RhoA activity via interactions with RhoGEF through its cytoplasmic tail. We performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments using a galectin-9–specific antibody and identified CD44 to interact with galectin-9 in moDCs (Fig. 7 A). As a positive control, Vamp-3 was also enriched in the galectin-9 IP compared with isotype control as previously reported (Santalla Mendez et al., 2023). Importantly, galectin-9 depletion or supplementation did not affect CD44 expression (Fig. 7 B). Next, we analyzed CD44 nanoscale organization at the surface of WT and gal9 KD DCs using super-resolution direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM) (Fig. 7 C). dSTORM images of CD44 clearly show CD44 exists in nanoclusters and in nonclustered form at the surface of DCs. The CD44 cluster size was found to be significantly higher in gal9 KD DCs compared with WT counterparts, and restoring surface galectin-9 levels reverted CD44 cluster size toward that of WT cells (Fig. 7 D). Overall, these data confirm CD44 and galectin-9 interact at the DC surface and suggest galectin-9 aids in modulating CD44 membrane clustering.

Galectin-9 interaction with CD44 regulates DC migration. (A) IP of galectin-9 or isotype negative control in whole-cell lysates obtained from day 7 matured moDCs. Co-IP complexes were resolved and probed against galectin-9, Vamp-3, and CD44. Graph shows quantification of the CD44 signal. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) CD44 expression in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDC lysates. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Graph shows mean CD44 expression of four independent donors (black symbols), and immunoblot is representative of four independent experiments. (C) Super-resolution dSTORM images of the basal membranes of day 7 matured WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs stained for CD44. ROI (red square) in the upper panel is depicted in the zoomed bottom panels (5,000 × 5,000 nm) to visualize CD44 nanoscale organization. (D) Mean ± SEM CD44 cluster diameter in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 was calculated per cell (gray dots) based on pair correlation analysis for 4 independent donors. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons was performed. (E) RhoA_GFP was incubated with either whole DC lysates from three independent donors pulled together (+) or nothing (−), and immunocomplexes were resolved by western blot and probed with specific antibodies against GEF-H1 and RhoA. Western blot is representative of two independent experiments. (F) Confocal microscopy of PLA assessing the proximity of CD44 to RhoA and GEF-H1 in mature moDCs. RhoA-GEF-H1 and isotypes were used as a positive and negative control, respectively. Scale bar: 5 µm. (G) Quantification of the number of PLA foci per cell area (black symbols) from images shown in F. Data represent the mean ± SEM from four independent donors (15–20 cells were analyzed/condition). One-way ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison correction was performed. (H) Quantification of the number of PLA foci (CD44-RhoA) per cell (black symbols) in WT or gal9 KD moDCs untreated or treated with 5 µg/ml of RhoA activator II. Data represent the mean ± SEM from two independent donors. 25–30 cells were analyzed per condition. One-way ANOVA was performed. (I) Quantification of the number of PLA foci (RhoA-GEF-H1) per cell (black symbols) in WT or gal9 KD moDCs. Data represent the mean ± SEM from three independent donors (20 cells were analyzed per condition). An unpaired t test was used to assess significance. n.s, P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001. IP, immunoprecipitation. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

Galectin-9 interaction with CD44 regulates DC migration. (A) IP of galectin-9 or isotype negative control in whole-cell lysates obtained from day 7 matured moDCs. Co-IP complexes were resolved and probed against galectin-9, Vamp-3, and CD44. Graph shows quantification of the CD44 signal. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) CD44 expression in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDC lysates. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Graph shows mean CD44 expression of four independent donors (black symbols), and immunoblot is representative of four independent experiments. (C) Super-resolution dSTORM images of the basal membranes of day 7 matured WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 moDCs stained for CD44. ROI (red square) in the upper panel is depicted in the zoomed bottom panels (5,000 × 5,000 nm) to visualize CD44 nanoscale organization. (D) Mean ± SEM CD44 cluster diameter in WT, gal9 KD, and gal9 KD + rGal9 was calculated per cell (gray dots) based on pair correlation analysis for 4 independent donors. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons was performed. (E) RhoA_GFP was incubated with either whole DC lysates from three independent donors pulled together (+) or nothing (−), and immunocomplexes were resolved by western blot and probed with specific antibodies against GEF-H1 and RhoA. Western blot is representative of two independent experiments. (F) Confocal microscopy of PLA assessing the proximity of CD44 to RhoA and GEF-H1 in mature moDCs. RhoA-GEF-H1 and isotypes were used as a positive and negative control, respectively. Scale bar: 5 µm. (G) Quantification of the number of PLA foci per cell area (black symbols) from images shown in F. Data represent the mean ± SEM from four independent donors (15–20 cells were analyzed/condition). One-way ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison correction was performed. (H) Quantification of the number of PLA foci (CD44-RhoA) per cell (black symbols) in WT or gal9 KD moDCs untreated or treated with 5 µg/ml of RhoA activator II. Data represent the mean ± SEM from two independent donors. 25–30 cells were analyzed per condition. One-way ANOVA was performed. (I) Quantification of the number of PLA foci (RhoA-GEF-H1) per cell (black symbols) in WT or gal9 KD moDCs. Data represent the mean ± SEM from three independent donors (20 cells were analyzed per condition). An unpaired t test was used to assess significance. n.s, P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001. IP, immunoprecipitation. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F7.

CD44 has been linked to RhoA activity before, but the guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) responsible for specifically activating RhoA in moDCs are not known. To uncover RhoA_GFP binding proteins, we employed GFP-trap pull-down experiments on DC whole-cell lysates followed by mass spectrometry and identified GEF-H1 (or ARHGEF2) to be the most abundant RhoGEF bound to RhoA in DCs. This interaction was confirmed by western blot (Fig. 7 E). GEF-H1 is strongly polarized to trailing-edge regions and is the main GEF driving uropod retraction (Kopf et al., 2020). Most Rho GTPases can be readily localized through staining, but membrane-bound RhoA cannot be distinguished from the cytosolic pool (Michaelson et al., 2001), and thus, to shed light on its interaction with CD44, we turned to proximity ligation assays (PLA) that allow for in situ detection of endogenous protein interactions within 40-nm distance. RhoA-GEF-H1 interaction and isotypes were used as positive and negative control, respectively (Fig. 7, F and G). A specific signal indicative of interaction was observed between CD44 and RhoA and between CD44 and GEF-H1 (Fig. 7, F and G), suggesting CD44 forms a complex with RhoA and GEF-H1 in DCs. Based on our time-lapse data, activation of RhoA via treatment with RhoA activator was sufficient to rescue the effects of galectin-9 depletion in moDC motility. Therefore, to delineate how the activation status of RhoA determines its interaction with CD44, we analyzed CD44-RhoA binding following gal9 KD in the absence or presence of the RhoA activator (Fig. 7 H). Binding of RhoA to CD44 was enhanced by galectin-9 depletion, which was reduced to WT levels upon treatment with the RhoA activator, indicating CD44 preferentially binds to GDP-bound RhoA. We also employed PLA to further explore RhoA functional interaction with GEF-H1 in response to galectin-9 depletion and demonstrate that RhoA association with GEF-H1 was significantly diminished in gal9 KD DCs, in line with a decreased RhoA activity upon loss of galectin-9 (Fig. 7 I). We conclude galectin-9–organized CD44 binds to and primes inactive RhoA to be activated by GEF-H1 to drive uropod retraction.

Galectin-9 is sufficient to rescue migration in tumor-immunosuppressed primary DCs

Having defined molecular basis of galectin-9–mediated uropod retraction, we validated the importance of galectin-9 on DC migration using human blood conventional DCs type 2 (cDC2s) as a model to better recapitulate a physiological setup (Fig. S5 A). Mature cDC2s were treated with melanoma-derived conditioned medium (CM) to impair their migratory capacity, after which rGal9 was provided to assess its ability to rescue cDC2 migration (Fig. 8 A). Migratory capacity of DCs was determined in a transwell migration assay toward the chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 for 3 h (Fig. 8.B). Exposure of mature cDC2s to melanoma-derived CM led to the downregulation of surface galectin-9 and CCR7 expression levels (Fig. 8, C and D). In line with the phenotype data, tumor-primed cDC2s exhibited a lower migratory capacity toward the chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 compared with untreated mature cDC2s (Fig. 8 E). Remarkably, the addition of exogenous galectin-9 rescued cDC2 migration toward the chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 (Fig. 8 E). CCR7 expression levels remained unchanged during galectin-9 addition (Fig. 8 D and Fig. S5 B), indicating this superior migratory capacity to be dependent on galectin-9 presence and not on an altered CCR7 expression. Taken together, these results validate the relevance of galectin-9 for the migration capacity of naturally occurring DC subsets in a tumor model and illustrate the therapeutic value of intervening galectin-9 signaling axis to restore the migration of tumor-immunocompromised DCs.

cDC2 cell purity and supplementary phenotype analysis. (A) Gating strategy to determine cDC2 purity after isolation from PBMCs. cDC2s were stained for CD1c, CD11c, CD14, and CD20. A first gate is set based on the physical FCS-A/SSC-A parameters followed by selecting on negative cells for CD14 and CD19. cDC2s are then identified as positive cells for CD11c and CD1c. (B) Surface galectin-9 and CCR7 expression in galectin-9 and CCR7-positive cDC2s. Graph shows average ± SEM gMFI of five individual donors. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons was performed. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. gMFI, geometric mean fluorescence intensity.

cDC2 cell purity and supplementary phenotype analysis. (A) Gating strategy to determine cDC2 purity after isolation from PBMCs. cDC2s were stained for CD1c, CD11c, CD14, and CD20. A first gate is set based on the physical FCS-A/SSC-A parameters followed by selecting on negative cells for CD14 and CD19. cDC2s are then identified as positive cells for CD11c and CD1c. (B) Surface galectin-9 and CCR7 expression in galectin-9 and CCR7-positive cDC2s. Graph shows average ± SEM gMFI of five individual donors. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons was performed. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. gMFI, geometric mean fluorescence intensity.

Galectin-9 restores chemokine-driven cDC2 migration. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental setup. Primary human cDC2s were matured overnight with a MC for 24 h prior to being harvested and replated in the presence of melanoma-derived CM for 24 h. Exogenous galectin-9 was supplemented for the last 2 h of cDC2 incubation with melanoma-derived CM. Tumor-primed cDC2s were collected and analyzed for the surface expression levels of galectin-9 and CCR7 or for their migratory capacity. (B) Schematic representation of the transwell migration assay. cDC2s were seeded in the top chamber of a transwell chamber containing a 5-µm porous membrane and subjected to a chemokine gradient of the CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21. Migratory cDC2s were collected after 3 h and quantified. (C) Histograms showing the surface expression of galectin-9 and CCR7 of a representative cDC2 donor analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Percentage of positive cDC2s for galectin-9 and CCR7 for each of the indicated treatments. (E) Relative cDC2 migration under each treatment was determined by normalizing each treatment to the migration given by mature cDC2s unexposed to the melanoma-derived CM for every donor. Violin plots in D and E show mean of five independent donors. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons was performed. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. MC, maturation cocktail.

Galectin-9 restores chemokine-driven cDC2 migration. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental setup. Primary human cDC2s were matured overnight with a MC for 24 h prior to being harvested and replated in the presence of melanoma-derived CM for 24 h. Exogenous galectin-9 was supplemented for the last 2 h of cDC2 incubation with melanoma-derived CM. Tumor-primed cDC2s were collected and analyzed for the surface expression levels of galectin-9 and CCR7 or for their migratory capacity. (B) Schematic representation of the transwell migration assay. cDC2s were seeded in the top chamber of a transwell chamber containing a 5-µm porous membrane and subjected to a chemokine gradient of the CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21. Migratory cDC2s were collected after 3 h and quantified. (C) Histograms showing the surface expression of galectin-9 and CCR7 of a representative cDC2 donor analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Percentage of positive cDC2s for galectin-9 and CCR7 for each of the indicated treatments. (E) Relative cDC2 migration under each treatment was determined by normalizing each treatment to the migration given by mature cDC2s unexposed to the melanoma-derived CM for every donor. Violin plots in D and E show mean of five independent donors. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons was performed. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. MC, maturation cocktail.

Discussion

Single-cell migration is a ubiquitous phenomenon in mammalian cell biology with cells mostly displaying either a mesenchymal or an amoeboid migration mode. The latter is employed by DCs, allowing for a fast and autonomous migration, driven by actin polymerization and actomyosin contractility forces. This is essential to rapidly shuttle antigens from peripheral tissues to lymphoid organs. However, how environmental cues and cell membrane organization integrate and modulate cytoskeleton remodeling and contractility remains poorly characterized.

In this study, we uncovered a role of galectin-9 in DC migration and report a novel function in controlling RhoA-mediated rear actomyosin contractility via modulating CD44 membrane organization and RhoA association. Through the use of 3D cultures and in vivo techniques, we have dissected the role of galectin-9 in actomyosin contractility in physiologically relevant settings (although we found galectin-9 function to be partially conserved in 2D migration). We demonstrate that galectin-9 regulates basal and chemokine-driven DC motility in humans and mice, suggesting a conserved function for this lectin. We propose that CD44 preferentially associates with inactive RhoA (GDP-bound) at the intracellular side of the plasma membrane. Upon activation, GEF-H1 dissociates from microtubules (Kopf et al., 2020; Renkawitz et al., 2019), thereby triggering RhoA disengagement from CD44 and the initiation of downstream signaling cascades that result in uropod contractility and cell movement (Fig. 9). We also reveal that immunosuppressed blood cDC2 cells express low levels of galectin-9 resulting in an impaired motility that can be rescued upon restoring galectin-9 levels. These data validate our results obtained using in vitro and in vivo models and highlight the importance of galectin-9 in cell migration in naturally occurring human blood DCs.

Graphical abstract. Galectin-9 controls cell rear contractility. Left: Galectin-9 binds to glycosylated residues on CD44 inducing CD44 clustering. This facilitates a functional interaction between CD44 and RhoA-GDP, priming RhoA for activation by GEF-H1. RhoA activation leads to actin contractility at the cell rear and migration. In the absence of galectin-9 (right panel), CD44 clustering is deficient, which results in defective RhoA activation and impaired uropod retraction and migration. Created in BioRender. Franken, G. (2025) https://BioRender.com/9zh1jyh.

Graphical abstract. Galectin-9 controls cell rear contractility. Left: Galectin-9 binds to glycosylated residues on CD44 inducing CD44 clustering. This facilitates a functional interaction between CD44 and RhoA-GDP, priming RhoA for activation by GEF-H1. RhoA activation leads to actin contractility at the cell rear and migration. In the absence of galectin-9 (right panel), CD44 clustering is deficient, which results in defective RhoA activation and impaired uropod retraction and migration. Created in BioRender. Franken, G. (2025) https://BioRender.com/9zh1jyh.