Neuropeptide-containing dense core vesicles (DCVs) generated in neuronal somata are circulated in axons to supply distal release sites, depending on kinesin-1, kinesin-3, and dynein, but how the motors are recruited remains unclear. Here we use proximity proteomics in the living Drosophila nervous system to identify the protein complex responsible for recruitment of kinesin-1 and dynein on DCVs. We find that the dynein and kinesin-1 adaptor Sunday driver (Syd/dJIP3/4) interact with the DCV-located GTPase Rab2 and also bind the Arl8 effector RUFY. Disrupting Rab2, Syd, RUFY, the Arl8 activator BORC, or dynein impedes retrograde DCV flux and induces axonal accumulation of immobile DCVs. Our data suggest that dynein is recruited and activated by a Syd/RUFY complex anchored to DCVs by Rab2 and Arl8. Rab2 loss but not disruption of Syd, RUFY, or dynein causes missorting of DCV membrane proteins into vesicle aggregates in motor neuron somata, suggesting that Rab2 employs separate effectors in DCV biogenesis and motility.

Introduction

In neurons, long-distance axonal transport along microtubules (MTs) mediated by molecular motors is critical for enabling axonal outgrowth, maintaining synaptic function, and ensuring structural and functional synaptic plasticity. Neuropeptide/neurohormone-containing dense core vesicles (DCVs) constitute a particular logistical challenge in this context since, unlike small synaptic vesicles (SVs) that are generated locally at the presynapse through endocytosis, DCVs are produced at the trans-Golgi network (TGN) in the soma and completely rely on axonal transport for delivery to distal synaptic release sites. Work in Drosophila (Wong et al., 2012) and hippocampal neurons (Bharat et al., 2017) indicates that DCVs circulate throughout the axonal arbor, only reversing direction at distal axonal termini and the proximal axon, and with only a relatively small probability of being deposited in any given synaptic bouton as they traverse it. This arrangement has been suggested to ensure an even distribution of DCVs between synaptic boutons within the arbor (Moughamian and Holzbaur, 2012; Wong et al., 2012). Moreover, the circulating DCVs represent a large reserve pool that can be quickly drawn upon by increasing synaptic capture when synaptic release sites are depleted (Cavolo et al., 2016; Shakiryanova et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2009). This means that anterograde transport (toward synaptic termini) and retrograde transport (toward the soma) are equally important for supplying synaptic boutons.

Axonal MTs are universally oriented with plus ends out toward distal axonal termini and minus ends toward the soma. Anterograde transport is mediated by plus end–directed kinesin family motors, while retrograde transport is mediated by the minus end–directed cytoplasmic dynein motor (Guedes-Dias and Holzbaur, 2019). These motors are usually autoinhibited in their native, non-cargo–coupled state, and motor activation and cargo attachment are regulated by a large set of cargo- and motor-specific accessory and adaptor proteins and often involve small GTPases of the Rab and Arf/Arl families (Cason and Holzbaur, 2022; Maday et al., 2014). Rab and Arf/Arl proteins behave like molecular switches, cycling between an inactive GDP-loaded soluble state and an active GTP-loaded state where they are inserted into specific organellar membranes and recruit specific effector proteins such as tethers, vesicle coats, and motor adaptors (Arrazola Sastre et al., 2021).

In both invertebrates and mammals, axonal DCV transport depends on the fast kinesin-3 and the slower kinesin-1 anterograde motors, as well as dynein (Barkus et al., 2008; Gavrilova et al., 2024; Gumy et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2017; Lo et al., 2011). Kinesin-3 is required to traverse a pre-axonal filtering region for cell body exit (Barkus et al., 2008; Bharat et al., 2017; Gumy et al., 2017) and is regulated by the DCV-resident (Lund et al., 2021) small GTPase Arl8, which binds and activates it directly (Niwa et al., 2016; Vukoja et al., 2018). However, it is less clear how kinesin-1 and dynein are recruited to DCVs to maintain DCV circulation (Cason and Holzbaur, 2022).

A potential clue to the mechanism governing retrograde DCV transport comes from our finding that the small GTPase Rab2 is required for axonal transport of DCVs and lysosomes in Drosophila (Lund et al., 2021). Notably, although we formerly speculated that Rab2 may control kinesin-3, the Rab2 loss-of-function phenotype was characterized by a strikingly selective reduction in retrograde DCV transport, implying that Rab2 may play a role in dynein regulation (Lund et al., 2021). Moreover, Rab2 overexpression caused the redistribution of DCVs from the axono-synaptic compartment to the soma in pupal neurons releasing the bursicon neuropeptide hormone (Lund et al., 2021). Rab2 is a highly conserved member of the Rab protein family, which, apart from its involvement in organelle motility, is indispensable for lysosomal function (Lorincz et al., 2017; Lund et al., 2018), autophagy (Ding et al., 2019; Fujita et al., 2017), synaptic protein sorting (Götz et al., 2021), and DCV biogenesis (Ailion et al., 2014; Buffa et al., 2008; Edwards et al., 2009; Sumakovic et al., 2009). Work mostly done in Caenorhabditis elegans indicates that Rab2 and certain Rab2 effectors prevent the loss of a subset of DCV cargos to late endosomes/lysosomes during DCV maturation (Ailion et al., 2014; Edwards et al., 2009; Sumakovic et al., 2009). Despite the identification of many molecular components, the details of the Rab2-dependent DCV cargo sorting pathway remain mysterious, although an endosomal recycling mechanism seems to be involved (Laurent et al., 2018; Topalidou et al., 2016).

Here we use proximity proteomics to reveal that active Rab2 associates with the dynein/kinesin-1 adaptor Sunday driver (Syd/dJIP3/4) and the dynein adaptor RUFY1 (RUFY) in living fly neurons. Biochemical experiments using Drosophila proteins expressed in HEK293 (HEK) cells indicate that Rab2 physically interacts with Syd via the Syd RH2 cargo-binding domain, while RUFY binds Syd through the Syd C-terminal WD40 domain. Furthermore, defects in Rab2, Syd, RUFY, dynein, and partially kinesin-1 produce qualitatively similar effects on axonal transport of DCVs in fly motor neurons, characterized by a selective loss of retrograde transport and an increase in the proportion of static DCVs in the axons. In contrast, mutation of kinesin-3 primarily results in a strong symmetric reduction of anterograde and retrograde DCV fluxes due to a block in cell body exit, coupled with severe slowing of anterograde transport. We also show that, like the mammalian RUFY1-4 proteins, fly RUFY also binds Arl8, suggesting that the dynein–dynactin activating retrograde transport complex composed of Syd and RUFY is stabilized on DCVs in a Rab2- and Arl8-dependent manner. Consistent with this, knockout of the Arl8-activating BORC complex produces a phenotype closely resembling dynein/kinesin-1 loss-of-function phenotypes. Lastly, we find that in Rab2 nulls, DCV membrane cargo is lost from DCVs and ectopically accumulates in phase-separated vesicle aggregates in neuronal somata. However, Syd, RUFY, and dynein are not responsible for the Rab2-dependent DCV membrane cargo sorting but may, together with Rab2, control DCV abundance.

Results

Proximity-dependent biotinylation identifies Syd/dJIP3/4 as a DCV-resident Rab2-interacting protein

Rab2 is present on neuronal DCVs, and retrograde axonal transport of DCVs is severely and selectively disrupted in motor neurons of Rab2 null third instar (L3) Drosophila larvae (Fig. 1 A) (Lund et al., 2021). We previously hypothesized that this reflects a function of Rab2 in the recruitment of molecular motors to the DCV surface through adaptor proteins. However, none of the known Rab2 effectors that could reasonably be expected to fill this role, such as the BicD dynein adaptor (Gillingham et al., 2014), were required for normal axonal DCV transport in flies (Lund et al., 2021). To identify potential novel effector proteins that could link activated Rab2 to motors responsible for DCV motility, we employed in vivo proximity-dependent biotinylation (PB) combined with quantitative mass spectrometry (MS), using a pan-neuronally expressed constitutively active GTP-locked TurboID-Rab2Q65L chimera as bait (Fig. 1 B). TurboID is a promiscuous biotin ligase derived from BirA* (Branon et al., 2018), which, when fused to a protein of interest and expressed in a desired tissue, biotinylates proteins in its immediate vicinity (within ∼10 nm [Kim et al., 2014]) that can then be isolated using streptavidin. To filter out proteins not specifically interacting with the active form of Rab2, the MS signal of purified biotinylated neuronal proteins from TurboID-Rab2Q65L–expressing adult flies was compared with that of control flies expressing the inactive GDP-locked TurboID-Rab2S20N variant. This approach identified ∼300 proteins significantly enriched more than twofold in the nano-environment of active neuronal Rab2 (Fig. 1 B, Data S1, and Data S2), including many known Rab2 effectors (Fig. S1 A). The remaining proteins in this group likely represent a mix of unknown effectors, constituents of effector complexes, and resident proteins of Rab2-associated vesicular compartments. The highest levels of enrichment were seen for proteins involved in lysosomal function and autophagy (with the most enriched protein being the transmembrane autophagy factor Atg9) (Fig. 1, B and C; and Data S2). This is in agreement with a critical role of Rab2 in lysosomal biogenesis and macroautophagy (Ding et al., 2019; Lorincz et al., 2017; Lund et al., 2018). Golgi apparatus–associated tethering proteins, many of them Rab2 effectors, were also well represented, consistent with the involvement of Rab2 in Golgi function (Götz et al., 2021; Short et al., 2001; Sinka et al., 2008). In addition, there was a strong representation of early and recycling endosomal proteins (Fig. 1 C and Data S2). Although this latter finding may in part reflect the difficulty of clearly differentiating between components belonging to the early and late stages of the endocytic pathway, it also fits with observations of Rab2 presence at a lower level throughout the endosomal system (Ding et al., 2019; Lund et al., 2018).

In vivo neuron-specific PB/MS in Drosophila for detection of proteins interacting with active Rab2 and the DCV membrane protein VMAT. (A) Schematic illustrating the effect of Rab2 loss on axonal transport of DCVs in flies (Lund et al., 2021). In WT motor axons, DCVs (blue spheres) are transported bidirectionally with similar anterograde and retrograde flux. In Rab2 null mutants, retrograde flux is strongly reduced, while anterograde flux is partially reduced. (B) Volcano plot showing the fold change and Student’s t test statistics of biotinylated protein label free quantification (LFQ) intensities from flies with pan-neuronal expression of TurboID-Rab2Q65L (elav > 2xHA-TurboID-Rab2Q65L) relative to TurboID-Rab2S20N (elav > 2xHA-TurboID-Rab2S20N). Proteins significantly upregulated in the active Rab2 condition (fold change > 2, FDR-adjusted P value < 0.05) are highlighted in red, and known Rab2 effectors in light blue (see also Fig. S1). (C) Distribution in subcellular neuronal compartments of proteins specifically enriched in flies expressing TurboID-Rab2Q65L compared with TurboID-Rab2S20N. EE, early endosomes; RE, recycling endosomes; LE, late endosomes; Lyso, lysosomes; Autoph, autophagosomes; Presyn, presynapse. (D) Representative STED image showing the distribution of ILP2-GFP and HA-tagged TurboID-VMAT fusion protein in motor axons in peripheral nerve A7 of third instar larva. Scale bars: left, 500 nm; right, 500 nm, 100 nm (inset). (E) Student’s t test of biotinylated protein LFQ intensities from flies with pan-neuronal expression of TurboID-VMAT (elav > ILP2-GFP, TurboID-HA-VMAT) relative to free cytosolic TurboID (elav > ILP2-GFP, TurboID). Proteins significantly enriched in the TurboID-HA-VMAT condition (fold change > 2, FDR-adjusted P value < 0.05) are highlighted in red. (F) Venn diagram of the overlap between proteins enriched both in flies expressing TurboID-Rab2Q65L and TurboID-VMAT. (G) Relationship between proteins significantly enriched in TurboID-Rab2Q65L and TurboID-VMAT flies, when ranked by enrichment level. Spearman’s rank correlation is 0.422, P < 10−6.

In vivo neuron-specific PB/MS in Drosophila for detection of proteins interacting with active Rab2 and the DCV membrane protein VMAT. (A) Schematic illustrating the effect of Rab2 loss on axonal transport of DCVs in flies (Lund et al., 2021). In WT motor axons, DCVs (blue spheres) are transported bidirectionally with similar anterograde and retrograde flux. In Rab2 null mutants, retrograde flux is strongly reduced, while anterograde flux is partially reduced. (B) Volcano plot showing the fold change and Student’s t test statistics of biotinylated protein label free quantification (LFQ) intensities from flies with pan-neuronal expression of TurboID-Rab2Q65L (elav > 2xHA-TurboID-Rab2Q65L) relative to TurboID-Rab2S20N (elav > 2xHA-TurboID-Rab2S20N). Proteins significantly upregulated in the active Rab2 condition (fold change > 2, FDR-adjusted P value < 0.05) are highlighted in red, and known Rab2 effectors in light blue (see also Fig. S1). (C) Distribution in subcellular neuronal compartments of proteins specifically enriched in flies expressing TurboID-Rab2Q65L compared with TurboID-Rab2S20N. EE, early endosomes; RE, recycling endosomes; LE, late endosomes; Lyso, lysosomes; Autoph, autophagosomes; Presyn, presynapse. (D) Representative STED image showing the distribution of ILP2-GFP and HA-tagged TurboID-VMAT fusion protein in motor axons in peripheral nerve A7 of third instar larva. Scale bars: left, 500 nm; right, 500 nm, 100 nm (inset). (E) Student’s t test of biotinylated protein LFQ intensities from flies with pan-neuronal expression of TurboID-VMAT (elav > ILP2-GFP, TurboID-HA-VMAT) relative to free cytosolic TurboID (elav > ILP2-GFP, TurboID). Proteins significantly enriched in the TurboID-HA-VMAT condition (fold change > 2, FDR-adjusted P value < 0.05) are highlighted in red. (F) Venn diagram of the overlap between proteins enriched both in flies expressing TurboID-Rab2Q65L and TurboID-VMAT. (G) Relationship between proteins significantly enriched in TurboID-Rab2Q65L and TurboID-VMAT flies, when ranked by enrichment level. Spearman’s rank correlation is 0.422, P < 10−6.

Rab2- and VMAT-specific PB-MS results, and colocalization of ILP2-GFP and TurboID-VMAT in motor neuron soma and synaptic bouton. (A) Previously identified Rab2 effectors (both Drosophila proteins and mammalian orthologs) found in our screen to be significantly enriched in TurboID-Rab2Q65L samples relative to TurboID-Rab2S20N. First 14 entries, confirmed effectors (also labelled in Fig. 1 B). All subunits of the HOPS complex were counted as effectors. Last 5 entries, potential effectors detected by affinity proteomics in Drosophila S2 cells (Gillingham et al., 2014) and MitoID relocalization proximity proteomics in HEK cells (Gillingham et al., 2019) but not confirmed using other methods. The list of unconfirmed effectors is not exhaustive. (B) Proteins known to reside on DCVs or to be involved in DCV biogenesis that were significantly enriched in TurboID-VMAT samples relative to free TurboID. (C) Representative STED images showing the distribution of ILP2-GFP and TurboID-HA-VMAT in motor neuron cell body located in the dorsomedial aspect of the VNC (left) and in peripheral synaptic bouton (right) in a third instar larva. White arrowheads, TurboID-VMAT associated with ILP-GFP–positive DCVs. Blue arrowheads, small TurboID-VMAT–positive vesicles not associated with ILP-GFP. The distribution of ILP2-GFP and TurboID-HA-VMAT in the mid-axon region in the same type of preparation is shown in Fig. 1 D. Scale bars (left to right): 1µm, 400 nm (inset 1), 200 nm (inset 2), 400 nm, 200 nm (inset).

Rab2- and VMAT-specific PB-MS results, and colocalization of ILP2-GFP and TurboID-VMAT in motor neuron soma and synaptic bouton. (A) Previously identified Rab2 effectors (both Drosophila proteins and mammalian orthologs) found in our screen to be significantly enriched in TurboID-Rab2Q65L samples relative to TurboID-Rab2S20N. First 14 entries, confirmed effectors (also labelled in Fig. 1 B). All subunits of the HOPS complex were counted as effectors. Last 5 entries, potential effectors detected by affinity proteomics in Drosophila S2 cells (Gillingham et al., 2014) and MitoID relocalization proximity proteomics in HEK cells (Gillingham et al., 2019) but not confirmed using other methods. The list of unconfirmed effectors is not exhaustive. (B) Proteins known to reside on DCVs or to be involved in DCV biogenesis that were significantly enriched in TurboID-VMAT samples relative to free TurboID. (C) Representative STED images showing the distribution of ILP2-GFP and TurboID-HA-VMAT in motor neuron cell body located in the dorsomedial aspect of the VNC (left) and in peripheral synaptic bouton (right) in a third instar larva. White arrowheads, TurboID-VMAT associated with ILP-GFP–positive DCVs. Blue arrowheads, small TurboID-VMAT–positive vesicles not associated with ILP-GFP. The distribution of ILP2-GFP and TurboID-HA-VMAT in the mid-axon region in the same type of preparation is shown in Fig. 1 D. Scale bars (left to right): 1µm, 400 nm (inset 1), 200 nm (inset 2), 400 nm, 200 nm (inset).

Strikingly, the second-most enriched protein for active Rab2 (∼200-fold enrichment over inactive Rab2, Fig. 1 B) was Syd, the fly ortholog of mammalian JIP3 and JIP4, which function as activating adaptors for dynein (Cason and Holzbaur, 2023; Singh et al., 2024) and also bind kinesin-1 (Bowman et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2011). Other notable highly enriched hits were RUFY1/CG31064 (∼50-fold enrichment; from hereon called RUFY), the fly ortholog of the mammalian RUFY1-4 family of coiled-coil proteins, recently shown to link Arl8 and Rab14 to dynein and possibly to function as dynein-activating adaptors (Keren-Kaplan et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2022; Rawat et al., 2023); and the ortholog of the mammalian Rab14 effector Nischarin (CG11807, ∼100-fold enrichment; from hereon called dNischarin) that shows distant homology to the SKIP motor adaptor (Rosa-Ferreira and Munro, 2011). Interestingly, RUFY1 and RUFY2 were previously detected as unconfirmed potential effectors of human Rab2A, using the MitoID PB protocol (Gillingham et al., 2019).

As a separate strategy to identify motor adaptors responsible for DCV motility, we also sought to determine the in vivo surface proteome of neuronal DCVs using the DCV-resident membrane protein vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) as PB bait. To this end, we generated a transgene encoding Drosophila VMAT fused through its cytosolic N-terminal tail to TurboID. Nanoscopic examination using stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy showed that when expressed in larval motor neurons together with the lumenal DCV cargo marker ILP2-GFP (Wong et al., 2012), most TurboID-VMAT decorates the limiting membrane of ILP2-positive DCVs, which were ∼130 nm in diameter (135 ± 2.0 nm, mean ± SEM, n = 1,026 vesicles). The association of VMAT with DCVs was most clearly seen in axons (Fig. 1 D), where the density of organelles is relatively low, but was also observed in somata and in synaptic boutons (Fig. S1 C). In boutons, TurboID-VMAT was also present in ∼50 nm wide (52 ± 1.1 nm, mean ± SEM, n = 25) punctate structures, possibly corresponding to small SVs (Fig. S1 C). Comparative quantitative MS of biotinylated proteins from flies pan-neuronally expressing either TurboID-VMAT or a free cytosolic TurboID control transgene yielded ∼450 proteins significantly enriched in the TurboID-VMAT line (Fig. 1 E and Data S3). Among the PB hits enriched for TurboID-VMAT were well-known DCV membrane and peripheral membrane proteins such as IA-2 (Solimena et al., 1996) and bitesize/granuphilin/SYTL4 (Li et al., 2018; Torii et al., 2002; Yi et al., 2002) (with the latter showing the highest enrichment of all proteins), as well as proteins involved in DCV biogenesis (Fig. 1 E and Fig. S1 B). We also observed a strong enrichment for SV and endocytic proteins, consistent with VMAT also being targeted to SVs (Grygoruk et al., 2014). Both Syd and Rab2 (though not RUFY or dNischarin) were also significantly enriched in the TurboID-VMAT dataset (Fig. 1 E and Data S3).

Overall, the Rab2Q65L- and VMAT-enriched protein sets overlapped quite substantially (Fig. 1 F), consistent with Rab2 and VMAT functioning within the same compartment(s). Moreover, we observed a significant correlation between enrichment levels across the two PB datasets (Fig. 1 G). Interestingly, among the highly enriched proteins in both the Rab2Q65L and VMAT screens were many components of the Snx3–retromer endosomal recycling complex (Harterink et al., 2011; McGough et al., 2018) and of a TGN vesicle tethering/fusion complex composed of TBC1D23, FAM91A1 (CG7600), and the Rab2-effector Golgin245 (Shin et al., 2017) (Fig. 1 G). This suggests that Rab2 may be involved in recycling of VMAT from endosomes to TGN. Other hits ranking high in both data sets included proteins related to DCV biogenesis and subunits of the BORC Arl8 activator complex (Fig. 1 G), consistent with the critical role of Arl8 in DCV motility (Lund et al., 2021).

Together, these data indicate that the dynein adaptors Syd and RUFY are spatially closely associated with active Rab2 in fly neurons in vivo and that Syd and Rab2 may be present together at the surface of DCVs.

Syd interacts with Rab2 via its RH2 domain and behaves as a Rab2 effector

To test if the high levels of PB enrichment reflected physical interactions between Rab2 and Syd, RUFY and dNischarin, we performed co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments using epitope-tagged versions of these proteins expressed in HEK cells. Only myc-tagged full-length Syd or truncated Syd1-529 (Syd-N2) coprecipitated Rab2Q65L in appreciable amounts, with RUFY and dNischarin producing yields barely above background (Fig. 2 A). The Rab2:Syd interaction was relatively fragile, requiring a saponin-based lysis/binding buffer to achieve noticeable Co-IP yields (Fig. S2 A). This is likely why this interaction was not found in earlier Rab:effector affinity-proteomic screening (Gillingham et al., 2014) and may indicate that it requires additional protein or lipid components. However, in Co-IP experiments, Syd bound much stronger to active compared with inactive forms of Rab2, thus behaving as a classical Rab GTPase effector (Fig. 2 B and Fig. S2 B). We therefore continued the investigation of the Rab2:Syd interaction.

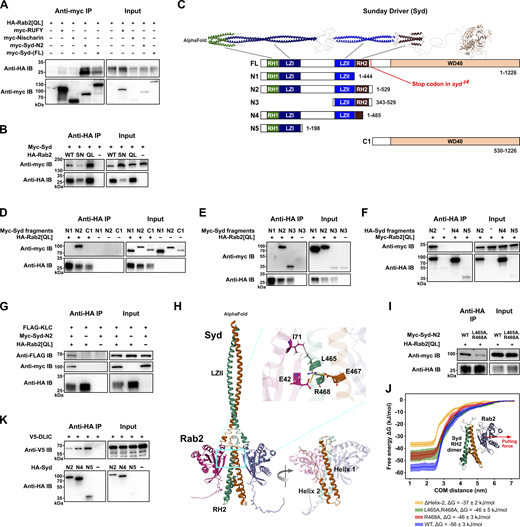

Syd binds active Rab2 via the RH2 domain and also binds kinesin-1 and dynein motors. Co-IP experiments performed on lysates from HEK cells transfected with constructs encoding epitope-tagged Drosophila proteins and MD simulation of the Syd:Rab2 interaction. (A) Myc-tagged full-length Syd and truncated Syd-N2 (Syd1-529) co-immunoprecipitate HA-tagged GTP-locked, constitutively active Rab2Q65L. In comparison, coprecipitation of HA-Rab2Q65L by myc-tagged dNischarin and RUFY is near background levels. (B) WT HA-Rab2 and HA-Rab2Q65L co-immunoprecipitate myc-Syd more efficiently than GDP-locked, inactive HA-Rab2S20N. (C) Structure of Syd. Top, expected structure of Syd homodimer assembled from three separate AlphaFold predictions. The WD40 domain of only one Syd monomer is shown. Bottom, schematic representation of the domain architecture of full-length Syd (isoform A, UniProt Q9GQF1) and of truncated Syd variants. (D and E) Co-IP of myc-tagged Syd fragments C1 and N1–N3 (shown in C) by HA-Rab2Q65L. Only myc-Syd-N2 and myc-Syd-N3, which contain the RH2 domain, coprecipitate with Rab2. (F) Co-IP of myc-Rab2Q65L by HA-tagged Syd fragments N2, N4, and N5. (G) FLAG-tagged Klc co-immunoprecipitates in complex with myc-Syd-N2 and HA-Rab2Q65L but not with HA-Rab2Q65L alone. (H) AlphaFold prediction of Syd LZII-RH2 (Syd359–526) dimer in complex with two copies of Rab2. Inset, R468 in Syd RH2 helix 1 is predicted to engage in ionic interactions with E42 in the Rab2 switch I region and E467 in the other RH2 monomer helix 1. L465 is predicted to engage in a hydrophobic interaction with Rab2 switch II I71. (I) Comparison of Co-IP of WT myc-Syd-N2 and mutant myc-Syd-N2L465A,R468A with HA-Rab2Q65L. (J) MD simulation. The Syd-RH2 dimer and one Rab2 moiety from the AlphaFold prediction in H were isolated in silico and pulled apart (the red arrow represents the pulling force direction) to estimate the free energy of the Rab2:Syd-RH2 binding. Free energy curves (mean and standard error, n = 10 for each curve) as a function of Rab2:RH2 center-of-mass distance were calculated for WT LZII-RH2 (blue), RH2L465A,R468A (green), RH2R468A (red), and RH2ΔHelix-2 (yellow), which was truncated after V504, removing the entire helix 2. (K) Co-IP of V5-tagged DLIC with HA-tagged Syd fragments N2, N4, and N5. Note the higher Co-IP efficiency for Syd-N4, where the C-terminal half of the RH2 domain (see Fig. S2 C) is absent, compared with Syd-N2, which has an intact RH2 domain. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

Syd binds active Rab2 via the RH2 domain and also binds kinesin-1 and dynein motors. Co-IP experiments performed on lysates from HEK cells transfected with constructs encoding epitope-tagged Drosophila proteins and MD simulation of the Syd:Rab2 interaction. (A) Myc-tagged full-length Syd and truncated Syd-N2 (Syd1-529) co-immunoprecipitate HA-tagged GTP-locked, constitutively active Rab2Q65L. In comparison, coprecipitation of HA-Rab2Q65L by myc-tagged dNischarin and RUFY is near background levels. (B) WT HA-Rab2 and HA-Rab2Q65L co-immunoprecipitate myc-Syd more efficiently than GDP-locked, inactive HA-Rab2S20N. (C) Structure of Syd. Top, expected structure of Syd homodimer assembled from three separate AlphaFold predictions. The WD40 domain of only one Syd monomer is shown. Bottom, schematic representation of the domain architecture of full-length Syd (isoform A, UniProt Q9GQF1) and of truncated Syd variants. (D and E) Co-IP of myc-tagged Syd fragments C1 and N1–N3 (shown in C) by HA-Rab2Q65L. Only myc-Syd-N2 and myc-Syd-N3, which contain the RH2 domain, coprecipitate with Rab2. (F) Co-IP of myc-Rab2Q65L by HA-tagged Syd fragments N2, N4, and N5. (G) FLAG-tagged Klc co-immunoprecipitates in complex with myc-Syd-N2 and HA-Rab2Q65L but not with HA-Rab2Q65L alone. (H) AlphaFold prediction of Syd LZII-RH2 (Syd359–526) dimer in complex with two copies of Rab2. Inset, R468 in Syd RH2 helix 1 is predicted to engage in ionic interactions with E42 in the Rab2 switch I region and E467 in the other RH2 monomer helix 1. L465 is predicted to engage in a hydrophobic interaction with Rab2 switch II I71. (I) Comparison of Co-IP of WT myc-Syd-N2 and mutant myc-Syd-N2L465A,R468A with HA-Rab2Q65L. (J) MD simulation. The Syd-RH2 dimer and one Rab2 moiety from the AlphaFold prediction in H were isolated in silico and pulled apart (the red arrow represents the pulling force direction) to estimate the free energy of the Rab2:Syd-RH2 binding. Free energy curves (mean and standard error, n = 10 for each curve) as a function of Rab2:RH2 center-of-mass distance were calculated for WT LZII-RH2 (blue), RH2L465A,R468A (green), RH2R468A (red), and RH2ΔHelix-2 (yellow), which was truncated after V504, removing the entire helix 2. (K) Co-IP of V5-tagged DLIC with HA-tagged Syd fragments N2, N4, and N5. Note the higher Co-IP efficiency for Syd-N4, where the C-terminal half of the RH2 domain (see Fig. S2 C) is absent, compared with Syd-N2, which has an intact RH2 domain. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F2.

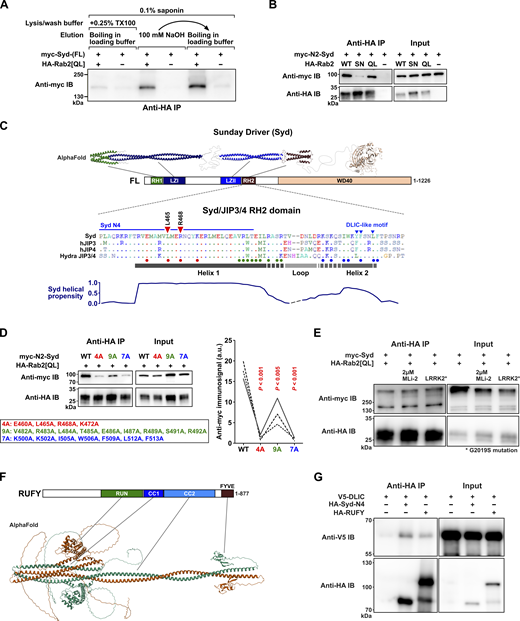

Additional details of the Rab2-Syd Co-IP interaction, the predicted structure of RUFY, and RUFY-DLIC Co-IP results. (A) Co-IP experiment performed on lysates from HEK cells transfected with constructs encoding epitope-tagged Drosophila proteins, illustrating the detergent sensitivity of the Rab2Q65L:Syd interaction. Western blot of eluates probed against myc showing coprecipitation of myc-Syd in the presence (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or absence (lanes 2, 4, and 6) of HA-Rab2Q65L when immunoprecipitating against HA. In lanes 1–2, the experiment was performed in the presence of 0.1% saponin and 0.25% Triton X-100, and proteins were eluted from the anti-HA beads by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. In lanes 3–4, the experiment was performed only in the presence of 0.1% saponin, and proteins were eluted with 100 mM NaOH. In lanes 5–6, the same anti-HA beads that were eluted with 100 mM NaOH were boiled in SDS-PAGE loading buffer to elute the remaining protein. (B) Co-IP of myc-Syd-N2 by HA-Rab2, HA-Rab2S20N, and HA-Rab2Q65L. Compared with the experiment using full-length myc-Syd shown in Fig. 2 B, the amount of transfecting DNA-encoding HA-Rab2S20N was increased to match the higher expression levels of HA-Rab2 and HA-Rab2Q65L. (C) Top, expected structure of Syd homodimer assembled from three separate AlphaFold predictions mapped onto the domain architecture of Syd. Middle, alignment of the RH2 domain from Drosophila Syd, human JIP3 and JIP4, and the cnidarian (Hydra vulgaris) JIP3/4 ortholog. Small dots in alignment indicate residue identity to Syd-RH2. The predicted locations of Helix 1, Helix 2, and the intervening loop from the AlphaFold model in Fig. 2 H are shown together with a helical propensity estimation (bottom). Also indicated are the location of the residues mutated to alanines in D (large colored dots below alignment) and Fig. 2 I (red triangles), the C-terminal extent of the Syd-N4 (Syd1-485) truncation, and the partially conserved DLIC-like motif involved in autoinhibition (Singh et al., 2024). (D) Left, Co-IP of WT myc-Syd-N2 and three different sets of myc-Syd-N2 alanine substitution mutants by HA-Rab2Q65L. The position of the mutations is indicated in C. Right, Quantification of the anti-myc immunosignal from eluted WT and mutated myc-Syd-N2 (n = three independent experiments). ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test. (E) The effect of different levels of LRRK2 activity on Co-IP of full-length myc-Syd by HA-Rab2Q65L. Endogenous HEK cell LRRK2 activity was inhibited by treatment of cells with 2µM MLi-2 for 2 h before lysis, or increased by co-transfection with a constitutively active LRRK2G2019S mutant. (F) Structure of an RUFY dimer predicted using AlphaFold 3, and the RUFY domain architecture. (G) Co-IP of V5-tagged DLIC with HA-tagged Syd-N4 (Syd1-485) and RUFY. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

Additional details of the Rab2-Syd Co-IP interaction, the predicted structure of RUFY, and RUFY-DLIC Co-IP results. (A) Co-IP experiment performed on lysates from HEK cells transfected with constructs encoding epitope-tagged Drosophila proteins, illustrating the detergent sensitivity of the Rab2Q65L:Syd interaction. Western blot of eluates probed against myc showing coprecipitation of myc-Syd in the presence (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or absence (lanes 2, 4, and 6) of HA-Rab2Q65L when immunoprecipitating against HA. In lanes 1–2, the experiment was performed in the presence of 0.1% saponin and 0.25% Triton X-100, and proteins were eluted from the anti-HA beads by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. In lanes 3–4, the experiment was performed only in the presence of 0.1% saponin, and proteins were eluted with 100 mM NaOH. In lanes 5–6, the same anti-HA beads that were eluted with 100 mM NaOH were boiled in SDS-PAGE loading buffer to elute the remaining protein. (B) Co-IP of myc-Syd-N2 by HA-Rab2, HA-Rab2S20N, and HA-Rab2Q65L. Compared with the experiment using full-length myc-Syd shown in Fig. 2 B, the amount of transfecting DNA-encoding HA-Rab2S20N was increased to match the higher expression levels of HA-Rab2 and HA-Rab2Q65L. (C) Top, expected structure of Syd homodimer assembled from three separate AlphaFold predictions mapped onto the domain architecture of Syd. Middle, alignment of the RH2 domain from Drosophila Syd, human JIP3 and JIP4, and the cnidarian (Hydra vulgaris) JIP3/4 ortholog. Small dots in alignment indicate residue identity to Syd-RH2. The predicted locations of Helix 1, Helix 2, and the intervening loop from the AlphaFold model in Fig. 2 H are shown together with a helical propensity estimation (bottom). Also indicated are the location of the residues mutated to alanines in D (large colored dots below alignment) and Fig. 2 I (red triangles), the C-terminal extent of the Syd-N4 (Syd1-485) truncation, and the partially conserved DLIC-like motif involved in autoinhibition (Singh et al., 2024). (D) Left, Co-IP of WT myc-Syd-N2 and three different sets of myc-Syd-N2 alanine substitution mutants by HA-Rab2Q65L. The position of the mutations is indicated in C. Right, Quantification of the anti-myc immunosignal from eluted WT and mutated myc-Syd-N2 (n = three independent experiments). ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test. (E) The effect of different levels of LRRK2 activity on Co-IP of full-length myc-Syd by HA-Rab2Q65L. Endogenous HEK cell LRRK2 activity was inhibited by treatment of cells with 2µM MLi-2 for 2 h before lysis, or increased by co-transfection with a constitutively active LRRK2G2019S mutant. (F) Structure of an RUFY dimer predicted using AlphaFold 3, and the RUFY domain architecture. (G) Co-IP of V5-tagged DLIC with HA-tagged Syd-N4 (Syd1-485) and RUFY. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

Structurally, Syd-family proteins (Syd/JIP3/JIP4) are large homodimers composed of an N-terminal region dominated by stretches of coiled-coil, followed by a C-terminal WD40 domain of unknown function (Fig. 2 C). The N-terminal half of Syd/JIP3/4 contains the RILP homology domains 1 and 2 (RH1 and RH2; also found in the distantly related RILP/RILPL family of adaptors), flanking two short leucine zipper domains (LZI and LZII) separated by a lengthy unstructured region (Fig. 2 C). The N-terminal RH1-LZI region of JIP3 binds in the cleft formed between dynein and dynactin and is sufficient to activate dynein motility (Singh et al., 2024). The more downstream LZII-RH2 region binds the kinesin-1 light chain (Klc) and Arf6 via the LZII domain (Bowman et al., 2000; Cockburn et al., 2018; Montagnac et al., 2009; Nguyen et al., 2005) and Rab8, 10, and 36 via the RH2 domain (Matsui et al., 2012; Waschbusch et al., 2020) and is thought to be responsible for cargo binding.

Consistent with this pattern, truncation mapping showed that an intact RH2 domain is required for Rab2 binding to Syd in Co-IP experiments (Fig. 2, C–F). Furthermore, while the isolated RH2 domain failed to express in HEK cells, a fragment consisting of only the LZII and RH2 domains (Syd-N3) was sufficient to be precipitated by active Rab2Q65L (Fig. 2 E). Also, while Rab2Q65L alone did not precipitate Drosophila Klc, it did so when co-overexpressed with Syd-N2 (Fig. 2 G), which contains all N-terminal coiled-coil regions but lacks the C-terminal region containing the WD40 domain (Fig. 2 C). This shows that Syd can bridge active Rab2 and molecular motors and that Rab2 binds Syd in a way that does not interfere with Klc binding at the LZII domain.

AlphaFold multimer modelling of the Syd LZII-RH2 dimer (Syd359-526) together with two Rab2 chains templated on the crystal structure of active GppNHp-bound Rab2 (PDB: 4rke) (Lardong et al., 2015) yielded a predicted structure or the Rab2:SydLZII-RH2 complex (Fig. 2 H). It broadly resembles the crystal structures of Rab7 bound to the RILP RH2-domain (PDB: 1yhn) (Wu et al., 2005) and phospho-Rab8a bound to the RILPL2 RH2-domain (PDB: 6rir) (Waschbusch et al., 2020). In the AlphaFold prediction, the two Syd-RH2 monomers, each composed of two roughly antiparallel alpha helixes (Helix 1 and Helix 2), together form a four-helix bundle, with the N-terminal part of each Helix 1 constituting the main interaction surface with Rab2 (Fig. 2 H). Alanine substitution of the highly conserved residues L465 and R468 (Fig. S2 C) in Helix α1 that were predicted to form contacts with the Rab2 switch regions (Fig. 2 H) substantially reduced Syd-N2 precipitation by Rab2Q65L (Fig. 2 I). These results were recapitulated by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the Rab2:SydLZII-RH2 AlphaFold structure, which predict that the R468 residue significantly contributes to Rab2:Syd-RH2–binding energy (Fig. 2 J). In addition, mutation of a cluster of nine conserved residues in Helix 2 (Syd7A-N2) (Fig. S2, C and D) or deletion of the entire Helix 2 together with the seven most C-terminal residues of Helix α1 (Syd1-485, Syd-N4) (Fig. 2 F) weakened and entirely abolished Syd-N2 precipitation by Rab2Q65L, respectively. Together with MD modelling predicting that removal of Helix 2 would result in a substantial decrease in binding energy (Fig. 2 J), these data indicate that Helix 2, like Helix 1, plays an important role in Rab2 binding, perhaps by stabilizing the Helix 1 dimer conformation.

A critical early step during the JIP3-assisted assembly and activation of the dynein–dynactin complex is binding of the dynein light intermediate chain (DLIC) to the JIP3 RH1 domain (Singh et al., 2024). We confirmed that the Syd–dynein interaction is conserved by showing that Syd-N2 can coprecipitate Drosophila DLIC (Fig. 2 K). Moreover, further truncated Syd variants lacking the RH2 Helix 2 (Syd-N4) or containing only the RH1-LZI region (Syd1-198, Syd-N5) precipitated DLIC noticeably better than Syd-N2 (Fig. 2 K). These data mirror recent findings showing that the JIP3 RH1 domain is autoinhibited by a conserved motif in the RH2 domain (Singh et al., 2024).

Collectively, these data suggest that active Rab2 interacts with Syd via the cargo-binding Syd RH2 domain and that this interaction is compatible with kinesin-1 and dynein recruitment by Syd.

Loss of Syd and Rab2 produce similar effects on axonal transport of DCVs and lysosomes

Loss of Syd causes a strong defect in the axonal transport of SV proteins in Drosophila larvae (Bowman et al., 2000). If Syd constitutes the Rab2-dependent link between DCVs and molecular motors, one would expect disruption of Syd and Rab2 to produce similar effects on DCV transport. Using confocal imaging, we therefore examined mid-axon transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in L3 larval motor neurons targeted by the OK6-Gal4 driver (Lund et al., 2021). Specifically, during time-lapse imaging of a 130 µm long stretch of the A7 peripheral nerve in fillet-dissected larvae, we photobleached two 60 μm long flanking segments around a 10 μm central region of the nerve and then recorded the movement of fluorescent DCVs initially located in the unbleached center as well as those entering laterally from outside the field of view (Fig. 3 A). This approach allows the examination of both the transport in the anterograde and retrograde directions (distinguishable because motor neuron axons are uniformly oriented toward the periphery) and the abundance of static vesicles. After converting the time-lapse movies of DCV transport to kymographs, we plotted the frequency distribution of the angle between vesicle trajectories and the vertical axis in the kymographs, using a fast Fourier transform (see Materials and methods). The resulting “directional distributions” (Fig. 3, B–D) are amenable to high-throughput analysis and provide a convenient overview of the relative amounts of anterograde and retrograde transport (left- and rightmost peaks, respectively) and the relative amount of static cargo (middle peak at 0°). The relative amplitudes of the anterograde/retrograde and static peaks in the directional distributions (Fig. 3, B–F) aligned well with absolute vesicle flux and static vesicle counts across the genotypes examined (Fig. 3, G and H).

Disruption of Rab2, Syd, and dynein result in similar DCV axonal transport phenotypes. (A) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons in the A7 nerve of third instar larvae with the indicated genotypes. KD, motor neuron-specific knockdown (driven by OK6-Gal4). Time-lapse confocal imaging was performed immediately after bleaching the areas indicated with red bars. Each kymograph depicts a single recording, except for Arl8/Df, where 20 superimposed recordings from nine larvae are shown (see Materials and methods). Scale bar: 10 µm. (B–D) Directional distributions showing the relative frequency of DCV transport velocities, expressed as the angle between the DCV trajectories and the vertical axis in the kymographs in A (see inset in B). Actual DCV velocities converted from angles have been added to the x axis in B. For each genotype except Arl8/Df, the directional distribution was averaged from n larvae, where n is equal to the number of data points in E–H (specified below). The directional distribution of Arl8/Df was produced from the superimposed Arl8/Df recordings in A. (E) Logarithmic ratio of the retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude in the directional distributions in B–D (the retrograde and anterograde peak amplitude are the maximal relative frequency of angles lower than −46° and higher than 46°, respectively). (F) The static peak amplitude relative to the sum of the static, retrograde, and anterograde peak amplitudes (the static peak amplitude is the maximal relative frequency of angles between −13° and 13°, located centrally on the x axis). (G) Counts of DCVs entering from the sides into the field of view in the anterograde or retrograde directions and of static vesicles in the central unbleached area. Counts were done over 30 s and multiplied by two, converting the dynamic vesicle counts to DCV flux in vesicles per minute. (H) Percentage of static vesicle counts relative to total vesicle counts for each genotype in G. Results involving Arl8/Df represent reanalysis of data published earlier (Lund et al., 2021). ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test (E, G, and H), Steel with control test (F). Number of larvae analyzed (n) in B–D and E–H: control 29, Rab2 10, sydz4/Df 12, Dhc-KD 12, Khc-KD 8, Arl8/Df 9, and unc-104P350/O3.1 12.

Disruption of Rab2, Syd, and dynein result in similar DCV axonal transport phenotypes. (A) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons in the A7 nerve of third instar larvae with the indicated genotypes. KD, motor neuron-specific knockdown (driven by OK6-Gal4). Time-lapse confocal imaging was performed immediately after bleaching the areas indicated with red bars. Each kymograph depicts a single recording, except for Arl8/Df, where 20 superimposed recordings from nine larvae are shown (see Materials and methods). Scale bar: 10 µm. (B–D) Directional distributions showing the relative frequency of DCV transport velocities, expressed as the angle between the DCV trajectories and the vertical axis in the kymographs in A (see inset in B). Actual DCV velocities converted from angles have been added to the x axis in B. For each genotype except Arl8/Df, the directional distribution was averaged from n larvae, where n is equal to the number of data points in E–H (specified below). The directional distribution of Arl8/Df was produced from the superimposed Arl8/Df recordings in A. (E) Logarithmic ratio of the retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude in the directional distributions in B–D (the retrograde and anterograde peak amplitude are the maximal relative frequency of angles lower than −46° and higher than 46°, respectively). (F) The static peak amplitude relative to the sum of the static, retrograde, and anterograde peak amplitudes (the static peak amplitude is the maximal relative frequency of angles between −13° and 13°, located centrally on the x axis). (G) Counts of DCVs entering from the sides into the field of view in the anterograde or retrograde directions and of static vesicles in the central unbleached area. Counts were done over 30 s and multiplied by two, converting the dynamic vesicle counts to DCV flux in vesicles per minute. (H) Percentage of static vesicle counts relative to total vesicle counts for each genotype in G. Results involving Arl8/Df represent reanalysis of data published earlier (Lund et al., 2021). ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test (E, G, and H), Steel with control test (F). Number of larvae analyzed (n) in B–D and E–H: control 29, Rab2 10, sydz4/Df 12, Dhc-KD 12, Khc-KD 8, Arl8/Df 9, and unc-104P350/O3.1 12.

In WT animals, apart from a smaller static component, we observed large anterograde and retrograde DCV fluxes with a moderate excess of anterograde transport (Fig. 3, A, B–E, and G), consistent with axonal DCV circulation. As reported previously (Lund et al., 2021), loss of Rab2 was associated with a pronounced DCV transport defect with a relative increase in the static vesicle signal, a moderate reduction in anterograde transport, and a disproportionately severe reduction in retrograde transport (Fig 3, A–C and E–H; and Video 1). The latter was evidenced by the almost complete disappearance of the sharp peak associated with retrograde transport in the directional distribution (Fig. 3, B and C). Importantly, a qualitatively similar but more severe phenotype was observed in larvae hemizygous for the sydz4 strong loss-of-function allele (Bowman et al., 2000) (sydz4/Df), or when dynein function was impaired in motor neurons by RNAi-mediated depletion of the dynein heavy chain (Dhc) (Fig 3, A–C and E–H; and Video 1). The speed of the remaining retrograde vesicles in Rab2 null and sydz4/Df animals was also considerably slower compared with WT, similar to Dhc-depleted animals (Fig. S3 B). Suppression of the kinesin-1 motor by kinesin-1 heavy chain (Khc) depletion also resulted in a transport defect characterized by a selective deficit in retrograde DCV traffic (Fig. 3, A–C and E–H; Fig. S3, A and B; and Video 1) and featuring the appearance of prominent axonal DCV-filled focal accumulations (Fig. 4 A). The selective effect of kinesin-1 dysfunction on the retrograde DCV flux in flies has been reported previously (Lim et al., 2017) and may be due to progressive stalling during anterograde transport, although there are also indications of direct and indirect codependence between kinesin-1 and dynein (Arimoto et al., 2011; Twelvetrees et al., 2016). These findings suggest that Rab2 and Syd are involved in the function of dynein and/or kinesin-1 during DCV transport.

Montage showing time-lapse imaging of DCV transport in axons in the A7 nerve of live fillet preparations of third instar OK6 > ILP2-GFP larvae with the indicated background genotypes. The first video frame is a pre-bleach image, while the subsequent frames shows DCV transport after photobleaching of the nerve, sparing the ∼10 µm wide central region. Ant, anterograde; Ret, retrograde. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Montage showing time-lapse imaging of DCV transport in axons in the A7 nerve of live fillet preparations of third instar OK6 > ILP2-GFP larvae with the indicated background genotypes. The first video frame is a pre-bleach image, while the subsequent frames shows DCV transport after photobleaching of the nerve, sparing the ∼10 µm wide central region. Ant, anterograde; Ret, retrograde. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Axonal transport speeds calculated from data in Fig. 3,, the defect in lysosomal transport of spin-GFP positive lysosomes in Rab2 null larvae, and apparently normal axonal DCV transport in prd1 null larvae.(A and B) Anterograde (A) and retrograde (B) DCV movement speeds from the experiments in Fig. 3 (OK6 > ILP2-GFP). Number of larvae analyzed: control 29, Rab2 10, sydz4/Df 12, Dhc-KD 12, Khc-KD 8, Arl8/Df 9, and unc-104P350/O3.1 12. (C) Representative kymographs showing transport of Spinster-positive organelles in motor axons (OK6 > Spinster-GFP) in control and Rab2 larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (D) Left, directional distributions derived from C, averaged from six control and six Rab2 larvae. Right, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude and the relative static peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. (E) Representative kymograph showing DCV transport in motor axons of prd1M56/Df larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (F) Directional distribution derived from E, averaged from four prd1M56/Df larvae (blue curve), shown together with a replica of the directional distribution of control larvae in Fig. 3, B–D (gray curve). Arl8/Df results in A and B, and the results in C and D represent reanalysis of data published earlier (Lund et al., 2021). Bar graphs in A, B, and D, right represent mean + SEM. ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test (A), Steel with control test (B), Student’s t test (D, right).

Axonal transport speeds calculated from data in Fig. 3,, the defect in lysosomal transport of spin-GFP positive lysosomes in Rab2 null larvae, and apparently normal axonal DCV transport in prd1 null larvae.(A and B) Anterograde (A) and retrograde (B) DCV movement speeds from the experiments in Fig. 3 (OK6 > ILP2-GFP). Number of larvae analyzed: control 29, Rab2 10, sydz4/Df 12, Dhc-KD 12, Khc-KD 8, Arl8/Df 9, and unc-104P350/O3.1 12. (C) Representative kymographs showing transport of Spinster-positive organelles in motor axons (OK6 > Spinster-GFP) in control and Rab2 larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (D) Left, directional distributions derived from C, averaged from six control and six Rab2 larvae. Right, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude and the relative static peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. (E) Representative kymograph showing DCV transport in motor axons of prd1M56/Df larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (F) Directional distribution derived from E, averaged from four prd1M56/Df larvae (blue curve), shown together with a replica of the directional distribution of control larvae in Fig. 3, B–D (gray curve). Arl8/Df results in A and B, and the results in C and D represent reanalysis of data published earlier (Lund et al., 2021). Bar graphs in A, B, and D, right represent mean + SEM. ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test (A), Steel with control test (B), Student’s t test (D, right).

Axonal levels and distribution of DCV cargo and disrupted transport of lysosomal organelles in syd mutants. (A) Left, representative pre-bleach confocal micrographs of the A7 nerve in third instar larvae expressing ILP2-GFP in motor neurons. Right, quantification of the axonal ILP2-GFP signal intensity. a.u., arbitrary units. Scale bar: 10 µm. Number of larvae analyzed: control 8, Rab2 10, sydz4/Df 12, Dhc-KD 12, Khc-KD 8, Arl8/Df 9, and unc-104P350/O3.1 12. (B) Neuromuscular junction of muscle fibers 6 and 7 in control, Rab2, and sydz4/Df larval fillets. Numbers in blue indicate the distal five boutons in a single branch of a motor neuron ending. Blue triangles indicate the most distal bouton in the same branch and other branches as well. Scale bar: 5 µm. (C and D) Left and middle, ILP2-GFP signal intensity in the distal five boutons of individual branches. Thick black lines represent the mean intensity for each bouton number. Dashed red lines were produced by linear regression. Right, regression line slopes. The mean ± SEM is indicated. Number of terminals (larvae) analyzed: control 13 (7), Rab2 6 (3) in C; control 16 (8), sydz4/Df 14 (8) in D. (E) Representative kymographs showing transport of Spinster-positive organelles in A7 motor axons of control and sydz4/Df third instar larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (F) Left, directional distributions of Spinster-positive organelle transport velocities, expressed as angles, cf. Fig. 3, B–D. Actual velocities converted from angles have been added to the x axis. For both control and sydz4/Df, the average directional distribution from 10 larvae is shown. Right, the relative static peak amplitude and the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. Bar graphs in F represent the mean + SEM. Steel with control test (A, right), Student’s t test (right of C, D, and F).

Axonal levels and distribution of DCV cargo and disrupted transport of lysosomal organelles in syd mutants. (A) Left, representative pre-bleach confocal micrographs of the A7 nerve in third instar larvae expressing ILP2-GFP in motor neurons. Right, quantification of the axonal ILP2-GFP signal intensity. a.u., arbitrary units. Scale bar: 10 µm. Number of larvae analyzed: control 8, Rab2 10, sydz4/Df 12, Dhc-KD 12, Khc-KD 8, Arl8/Df 9, and unc-104P350/O3.1 12. (B) Neuromuscular junction of muscle fibers 6 and 7 in control, Rab2, and sydz4/Df larval fillets. Numbers in blue indicate the distal five boutons in a single branch of a motor neuron ending. Blue triangles indicate the most distal bouton in the same branch and other branches as well. Scale bar: 5 µm. (C and D) Left and middle, ILP2-GFP signal intensity in the distal five boutons of individual branches. Thick black lines represent the mean intensity for each bouton number. Dashed red lines were produced by linear regression. Right, regression line slopes. The mean ± SEM is indicated. Number of terminals (larvae) analyzed: control 13 (7), Rab2 6 (3) in C; control 16 (8), sydz4/Df 14 (8) in D. (E) Representative kymographs showing transport of Spinster-positive organelles in A7 motor axons of control and sydz4/Df third instar larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (F) Left, directional distributions of Spinster-positive organelle transport velocities, expressed as angles, cf. Fig. 3, B–D. Actual velocities converted from angles have been added to the x axis. For both control and sydz4/Df, the average directional distribution from 10 larvae is shown. Right, the relative static peak amplitude and the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. Bar graphs in F represent the mean + SEM. Steel with control test (A, right), Student’s t test (right of C, D, and F).

In contrast, larvae carrying a heteroallelic combination of the unc-104P350 null and unc-104O3.1 hypomorphic mutations of the fast anterograde kinesin-3 family Unc-104 motor (ortholog of mammalian KIF1A/B/C) displayed a qualitatively different axonal transport phenotype characterized by a severe reduction in axonal DCV content (Fig. 4 A) due to a failure of cell body exit (Barkus et al., 2008), combined with more symmetrical bidirectional fluxes of remaining axonal DCVs (Fig. 3, A, B, and D–H; and Video 1). unc-104P350/unc-104O3.1 animals also displayed a strong reduction in the mean anterograde vesicle speed (Fig. S3 A), reflected in a pronounced leftward shift (toward lower velocities) of the anterograde peak in the directional distribution (Fig. 3, B and D). This is consistent with Unc-104 being responsible for fast anterograde DCV movement (Barkus et al., 2008; Lim et al., 2017). Applying the same analysis to previously published (Lund et al., 2021) DCV axonal transport recordings in animals lacking Arl8, thought to be responsible for Unc-104 activation (Guardia et al., 2016; Niwa et al., 2016; Vukoja et al., 2018), also showed a similar phenotype with very strong but symmetrical reductions in the bidirectional DCV flux, but without the characteristic reduction in anterograde speed (Fig. 3, A, B, and D–H; and Fig. S3 A). Interestingly, unlike unc-104 mutants, but resembling Rab2, Syd, Dhc, and kinesin-1–deficient animals, Arl8 nulls also displayed a large relative increase in the static DCV component, suggesting that it may also be involved in regulation of kinesin-1 and dynein motors (Fig. 3, A, B, and D–H).

Disruption of dynein function causes a pronounced accumulation of excess DCVs in the distal-most boutons of larval motor terminals (Wong et al., 2012). Consistent with this observation, in type Ib motor terminals on larval muscles 6 and 7, both syd and Rab2 mutants displayed a clear reversal of the usual trend of decreasing bouton content of ILP2-GFP in more distal boutons (Fig. 4, B–D), although the Syd phenotype was again more severe. This further indicates that Rab2 and Syd are required for retrograde dynein-dependent transport.

Besides DCV transport, Rab2 is required for axonal transport of lysosomes and early/late endosomes in flies (Lund et al., 2021). JIP3/4 are also well known to mediate lysosomal motility in mammals (Cason and Holzbaur, 2023; Drerup and Nechiporuk, 2013; Gowrishankar et al., 2021; Kluss et al., 2022). We found that transport of lysosomes labelled with Spinster-Venus was severely disrupted in motor axons of sydz4/Df mutant larvae, with less bidirectional transport and a relative increase in static organelles (Fig. 4, E and F). While direct comparisons with previously recorded data for Rab2 nulls (Fig. S3, C and D) (Lund et al., 2021) are difficult due to the use of different markers (Spinster-Venus vs. Spinster-GFP, necessitated by the different chromosomal locations of Rab2 and syd), the disruption of lysosomal transport appeared to be similar in Rab2 and syd mutants, albeit with a stronger defect in sydz4/Df.

In conclusion, loss of Rab2 and Syd produces qualitatively similar axonal transport defects for DCVs and lysosomes, although the Syd mutant phenotype is more severe. Moreover, the Rab2 and Syd-related DCV transport defect is consistent with a disruption of dynein-mediated retrograde motility.

The Arl8 effector RUFY cooperates with Syd to drive retrograde axonal transport of DCVs

The less severe Rab2 null DCV transport phenotype compared with the syd mutant phenotype strongly suggests the presence of additional vesicular Syd-recruitment factors. Syd/JIP3/4 proteins bind small GTPases Arf6 (Montagnac et al., 2009), Rab36, Rab8, and LRRK-phosphorylated Rab10 (Matsui et al., 2012; Waschbusch et al., 2020), of which Rab8 and Rab10 were enriched in our VMAT-specific PB dataset (Fig. S4 A and Data S3). Moreover, Arf6 and Rab10 control JIP3/4-mediated axonal transport of mammalian autolysosomes (Boecker et al., 2021; Cason and Holzbaur, 2023). We tested larvae with null mutations in Arf6, Rab8, and Rab10 or homozygous for a transposon insertion allele for the fly Rab36 ortholog, RabX5, but found no obvious disruption of axonal DCV transport (Fig. S4, B and C). Of multiple Rabs (besides Rab2) enriched in VMAT-proximity proteomics (Fig. S4 A), only Rab1 or Rab11 produced any effect on axonal DCV transport when disrupted by mutation or motor neuron-specific depletion (Fig. S4, B–G). However, since no physical interactions between Rab1 or Rab11 and Syd family proteins have been reported, and the Rab1- and Rab11-depleted animals did not develop beyond late first or early second instar, we did not pursue this line of inquiry further. We also tested the ortholog of the mammalian TMEM55A/B transmembrane proteins (CG6707), which ranked high in both Rab2- and VMAT-PB datasets (Fig. 1 G). TMEM55B mediates the recruitment of JIP4 for dynein-mediated lysosomal motility in mammals (Willett et al., 2017). However, depletion of CG6707 with two independent RNAi transgenes did not affect axonal transport of DCVs (Fig. S5, A and B).

Effect of disrupting different Rab and Arf GTPases on axonal DCV transport. (A) Small GTPases enriched in the VMAT-specific PB dataset or known to bind JIP3/4/Syd. (B) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in third instar larval motor axons in controls, the indicated Rab GTPase mutants, and Arf6/Df. Scale bar: 10 µm. (C) Left, directional distributions derived from B, averaged from the following number of larvae: control 10, Rab32AR 10, Rab26 8, Rab3/Df 6, Rab8/Df 6, Rab10 8, RabX5 6, and Arf6/Df 11. Right, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. N.s., not significant (ANOVA, P = 0.522). (D) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons in control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-specific knockdown of Rab11. DCV transport was recorded in second instar larvae for both genotypes. Scale bar: 10 µm. (E) Left, directional distributions derived from D, averaged from seven control and seven Rab11-KD larvae. Right, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. (F) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons in control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-specific knockdown of Rab1. DCV transport was recorded in first instar larvae for both genotypes. Scale bar: 10 µm. (G) Left, directional distributions derived from F, averaged from four control and three Rab1-KD larvae. Right, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. Bar graphs in C, E, and G represent mean + SEM. ANOVA (C, right), Student’s t test (E, right; G, right).

Effect of disrupting different Rab and Arf GTPases on axonal DCV transport. (A) Small GTPases enriched in the VMAT-specific PB dataset or known to bind JIP3/4/Syd. (B) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in third instar larval motor axons in controls, the indicated Rab GTPase mutants, and Arf6/Df. Scale bar: 10 µm. (C) Left, directional distributions derived from B, averaged from the following number of larvae: control 10, Rab32AR 10, Rab26 8, Rab3/Df 6, Rab8/Df 6, Rab10 8, RabX5 6, and Arf6/Df 11. Right, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. N.s., not significant (ANOVA, P = 0.522). (D) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons in control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-specific knockdown of Rab11. DCV transport was recorded in second instar larvae for both genotypes. Scale bar: 10 µm. (E) Left, directional distributions derived from D, averaged from seven control and seven Rab11-KD larvae. Right, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. (F) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons in control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-specific knockdown of Rab1. DCV transport was recorded in first instar larvae for both genotypes. Scale bar: 10 µm. (G) Left, directional distributions derived from F, averaged from four control and three Rab1-KD larvae. Right, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. Bar graphs in C, E, and G represent mean + SEM. ANOVA (C, right), Student’s t test (E, right; G, right).

Effect on axonal DCV transport of RNAi knockdown of different genes involved in trafficking of DCV membrane proteins or suspected to play a role in motor adaptor recruitment. (A) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-targeted knockdown of Rab14, dNischarin, or CG6707. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Top, directional distributions derived from A, averaged from the following number of larvae: control 13, Rab14-KD 7, dNischarin-KD 8, CG6707(KK)-KD 7, and CG6707(VAL10)-KD 6. Bottom, the retrograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.917), anterograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.150), logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.738), and relative static peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.089) for the directional distributions at the top. In A and B, KK and VAL20 refer to the use of UAS-RNAi lines from the KK collection and the VALIUM10 vector-based collection, respectively. For simplicity, only KK line data are illustrated in A. (C) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-targeted knockdown of Rab4, ruby, or Vps35. Scale bar: 10 µm. (D) Top, directional distributions derived from C, averaged from the following number of larvae: control 9, Rab4-KD 9, ruby-KD 8, and Vps35-KD 9. Bottom, the retrograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.431), anterograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.298), logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.415), and relative static peak amplitude (ANOVA, P <0.005, followed by Dunnett’s test obtaining the indicated P values). Data in all panels are from third instar larvae. Bar graphs in B and D represent mean + SEM. N.s., not significant.

Effect on axonal DCV transport of RNAi knockdown of different genes involved in trafficking of DCV membrane proteins or suspected to play a role in motor adaptor recruitment. (A) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-targeted knockdown of Rab14, dNischarin, or CG6707. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Top, directional distributions derived from A, averaged from the following number of larvae: control 13, Rab14-KD 7, dNischarin-KD 8, CG6707(KK)-KD 7, and CG6707(VAL10)-KD 6. Bottom, the retrograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.917), anterograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.150), logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.738), and relative static peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.089) for the directional distributions at the top. In A and B, KK and VAL20 refer to the use of UAS-RNAi lines from the KK collection and the VALIUM10 vector-based collection, respectively. For simplicity, only KK line data are illustrated in A. (C) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-targeted knockdown of Rab4, ruby, or Vps35. Scale bar: 10 µm. (D) Top, directional distributions derived from C, averaged from the following number of larvae: control 9, Rab4-KD 9, ruby-KD 8, and Vps35-KD 9. Bottom, the retrograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.431), anterograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.298), logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude (ANOVA, P = 0.415), and relative static peak amplitude (ANOVA, P <0.005, followed by Dunnett’s test obtaining the indicated P values). Data in all panels are from third instar larvae. Bar graphs in B and D represent mean + SEM. N.s., not significant.

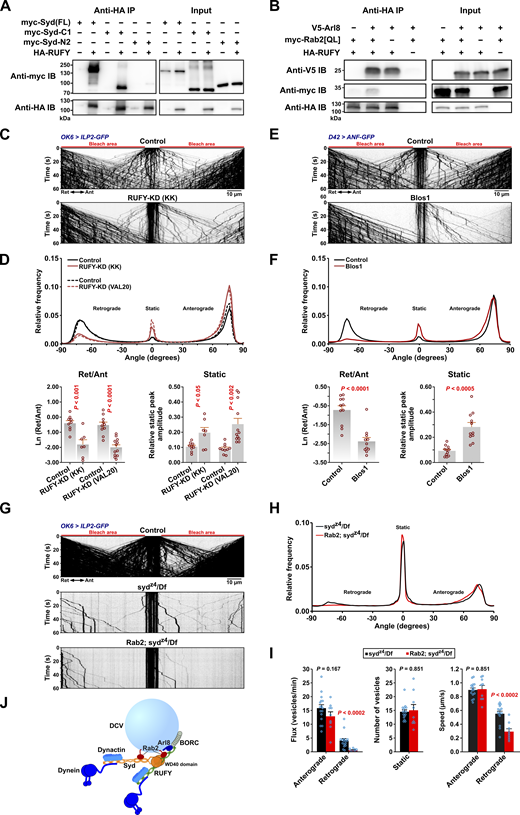

In our search for more components of the retrograde motor complex, we next focused our attention on dNischarin and RUFY, which also ranked high in the Rab2-PB dataset but did not interact strongly with Rab2 (Fig. 1 B and Fig. 2 A). Interestingly, while motor neuron-specific dNischarin depletion produced no effect (Fig. S5, A and B), depletion of RUFY with two independent RNAi transgenes caused a pronounced DCV transport defect characterized by a selective reduction in retrograde movement and a relative increase in static DCV cargo (Fig. 5, C and D). As almost all retrograde DCV transport is already lost in sydz4/Df animals (Fig. 3, A–C, and G), we reasoned that Syd and RUFY function as part of the same mechanism to recruit/activate dynein. Although mammalian RUFY proteins have been proposed to function as dynein-activating adaptors in their own right (Keren-Kaplan et al., 2022; Rawat et al., 2023), at least one, RUFY3, also binds JIP4 (Kumar et al., 2022). Consistent with this observation, we found that fly RUFY immunoprecipitates Syd when the two proteins are expressed together in HEK cells. This interaction appears to depend on the Syd C-terminal WD40 domain, as the Syd-C1 (Syd530-1226) region containing it is both required and sufficient for a strong binding to RUFY (Fig. 5 A). Similar to its mammalian orthologs, which are ARL8A/B effectors (Keren-Kaplan et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2022; Rawat et al., 2023), RUFY also bound fly Arl8 in Co-IP experiments (Fig. 5 B). The presence of Arl8 also increased the interaction between RUFY and Rab2Q65L, similar to the reported effect of Arl8b on the interaction between RUFY1 and the Rab2-related (Haga and Fukuda, 2025) Rab14 GTPase in mammals (Rawat et al., 2023) (Fig. 5 B). This suggests that Syd may be recruited to the DCV surface by a combination of interactions, including Rab2-binding via the RH2 domain and WD40 domain-dependent binding to RUFY, which itself is recruited to the vesicles via Arl8 and possibly Rab2 (Fig. 5 J).

RUFY interacts with Syd, Arl8, and Rab2 and is required for axonal DCV transport. (A and B) Western blots of the indicated Co-IP eluates (∼40% eluate volume) and HEK cell lysates (∼1% reaction volume). A, HA-tagged RUFY co-immunoprecipitates myc-tagged full-length Syd and truncated Syd-C1 (Syd530-1226) containing only the C-terminal WD40 domain but not truncated Syd-N2 (Syd1-529) that lacks the WD40 domain. B, HA-RUFY co-immunoprecipitates V5-tagged Arl8, and co-expression of V5-Arl8 enhances Co-IP of myc-Rab2Q65L with HA-RUFY. (C) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-specific knockdown of RUFY, driven by OK6-Gal4. Scale bar: 10 µm. (D) Top, directional distributions derived from C, averaged from the following number of larvae: control for RUFY-KD(KK) 9, RUFY-KD(KK) 7; control for RUFY-KD(VAL20) 10, RUFY-KD(VAL20) 12. Bottom, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude and the relative static peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the top. In C and D, “KK” and “VAL20” refer to UAS-RNAi lines from the KK collection and the VALIUM20 vector-based collection, respectively. For simplicity, only KK line data are illustrated in C. (E) Representative kymographs showing transport of ANF-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control and Blos1 larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (F) Top, directional distributions derived from E. Averages from 11 larvae are shown for both Control and Blos1. Bottom, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude and the relative static peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the top. (G) Kymographs of transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control, sydz4/Df single mutant, and Rab2; sydz4/Df double mutant larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (H) Directional distributions derived from G, averaged from 16 sydz4/Df and 9 Rab2; sydz4/Df larvae. (I) Flux of dynamic vesicles, counts of static vesicles in the central unbleached region, and speed of dynamic vesicles in the sydz4/Df and Rab2; sydz4/Df mutants also shown in H. (J) Hypothetical model of the DCV dynein–dynactin recruitment complex, consisting of Syd and RUFY anchored to the vesicle by Rab2 and Arl8. Kinesin-1 bound by Syd and kinesin-3 regulated by Arl8-BORC are omitted. It is uncertain if RUFY can recruit and activate dynein–dynactin. Bar graphs in D, F, and I represent the mean + SEM and were analyzed with Student’s t test. For conversion of angles in D, F, and H to DCV velocities, see Fig. 3 B. All data are from third instar larvae. Results in E and F represent reanalysis of data published earlier (Lund et al., 2021). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

RUFY interacts with Syd, Arl8, and Rab2 and is required for axonal DCV transport. (A and B) Western blots of the indicated Co-IP eluates (∼40% eluate volume) and HEK cell lysates (∼1% reaction volume). A, HA-tagged RUFY co-immunoprecipitates myc-tagged full-length Syd and truncated Syd-C1 (Syd530-1226) containing only the C-terminal WD40 domain but not truncated Syd-N2 (Syd1-529) that lacks the WD40 domain. B, HA-RUFY co-immunoprecipitates V5-tagged Arl8, and co-expression of V5-Arl8 enhances Co-IP of myc-Rab2Q65L with HA-RUFY. (C) Representative kymographs showing transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control larvae and larvae subjected to motor neuron-specific knockdown of RUFY, driven by OK6-Gal4. Scale bar: 10 µm. (D) Top, directional distributions derived from C, averaged from the following number of larvae: control for RUFY-KD(KK) 9, RUFY-KD(KK) 7; control for RUFY-KD(VAL20) 10, RUFY-KD(VAL20) 12. Bottom, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude and the relative static peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the top. In C and D, “KK” and “VAL20” refer to UAS-RNAi lines from the KK collection and the VALIUM20 vector-based collection, respectively. For simplicity, only KK line data are illustrated in C. (E) Representative kymographs showing transport of ANF-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control and Blos1 larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (F) Top, directional distributions derived from E. Averages from 11 larvae are shown for both Control and Blos1. Bottom, the logarithmic ratio of retrograde to anterograde peak amplitude and the relative static peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the top. (G) Kymographs of transport of ILP2-GFP–positive DCVs in motor axons of control, sydz4/Df single mutant, and Rab2; sydz4/Df double mutant larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (H) Directional distributions derived from G, averaged from 16 sydz4/Df and 9 Rab2; sydz4/Df larvae. (I) Flux of dynamic vesicles, counts of static vesicles in the central unbleached region, and speed of dynamic vesicles in the sydz4/Df and Rab2; sydz4/Df mutants also shown in H. (J) Hypothetical model of the DCV dynein–dynactin recruitment complex, consisting of Syd and RUFY anchored to the vesicle by Rab2 and Arl8. Kinesin-1 bound by Syd and kinesin-3 regulated by Arl8-BORC are omitted. It is uncertain if RUFY can recruit and activate dynein–dynactin. Bar graphs in D, F, and I represent the mean + SEM and were analyzed with Student’s t test. For conversion of angles in D, F, and H to DCV velocities, see Fig. 3 B. All data are from third instar larvae. Results in E and F represent reanalysis of data published earlier (Lund et al., 2021). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F5.

This model fits with our observations that Arl8 nulls, besides showing a relatively symmetrical reduction in the extent of anterograde and retrograde transport due to a failure of cell body exit (Lund et al., 2021), also display a strong increase in the proportion of static DCVs (Fig. 3, A, B, and D–H) similar to the syd/dynein/kinesin-1 phenotypic group. An involvement of Arl8 in dynein regulation via RUFY can also explain our previously published data (Lund et al., 2021) showing that knockout of the critical BORC subunit, Blos1 (Boda et al., 2019; Pu et al., 2015), produces a strikingly selective loss of retrograde axonal transport of ANF-positive DCVs (reanalyzed in Fig. 5, E and F).

In addition to binding Arl8, RUFY proteins are also known as Rab effectors; fly RUFY binds active Rab4 (Gillingham et al., 2014), and mammalian RUFY1 requires Rab14 for recruitment to endosomes (Rawat et al., 2023). We observed that whereas Rab14 depletion did not affect DCV axonal transport, a small but significant increase in the static component resulted upon Rab4 depletion, suggesting that Rab4 may have a minor role in RUFY recruitment to DCVs (Fig. S5, C and D).

A requirement for the Syd:RUFY interaction potentially explains the strong phenotype of the sydz4 allele, which introduces a premature stop codon (at amino acid position 514 in isoform A), leading to the truncation of the entire Syd WD40 domain but leaving a protein roughly corresponding to our Syd-N2 construct (Bowman et al., 2000; Schulman et al., 2014) (Fig. 2 C), containing both the Rab2-binding RH2 domain and the dynein–dynactin-activating region as defined by Singh et al. (2024) for JIP3 (Singh et al., 2024). Interestingly, although almost all retrograde (and most anterograde) transport is lost in sydz4/Df hemizygous larvae (Fig. 3, A–C, and G), a small retrograde DCV flux remained (Fig. 5, G–I). This residual retrograde flux was almost entirely eliminated in Rab2; sydz4/Df double mutants, with the few remaining retrograde vesicles moving significantly slower, as would be expected if it was driven by lower affinity recruitment of the remaining Syd fragment by Rab2 alone (Fig. 5, G–I). However, we cannot exclude an alternative model where RUFY functions directly as the activating adaptor for dynein and is recruited to DCVs by a combination of Syd (via the WD40 domain), Rab2, and Arl8 (Fig. 5 J).

In conclusion, Syd and the Arl8 effector RUFY interact via the Syd C-terminal WD40 domain and together are required for retrograde axonal transport of DCVs. This implies that Arl8 and its activator, BORC, are also involved in retrograde dynein-mediated DCV transport, in addition to axonal entry and anterograde transport mediated by kinesin-3.

JNK promotes axonal DCV motility

Besides the vesicular motor adaptor role, Syd/JIP3/4 proteins function as important scaffolds and transport adaptors for the JNK MAP kinase (Byrd et al., 2001; Ito et al., 1999; Kelkar et al., 2000). Active JNK is important for axonogenesis and is enriched in mature axons (Oliva et al., 2006). Moreover, there are strong indications that JNK regulates Syd-linked motor activity or Syd-cargo binding (Byrd et al., 2001; Schulman et al., 2014). We therefore tested if the activity level of the sole fly JNK ortholog, basket (bsk), affects axonal DCV transport. Overexpression of dominant-negative bsk (bsk-DN) in larval motor neurons increased the relative amount of static axonal DCV signal, accompanied by a doubling of total axonal DCV marker content (Fig. 6, A–C), implying an increase in the total mid-axonal DCV population due to DCV stalling. As motor neuron overexpression of the constitutively active form of the upstream bsk activator hemipterous/MKK7 (hep-Act) blocked development before the L3 stage, we also examined DCV transport in hep-Act– and bsk-DN–expressing L2 larvae. Though at this early developmental stage bsk-DN did not result in an appreciable relative increase in static vesicles, hep-Act expression both reduced the relative amount of static vesicles and the total axonal ILP2 content (Fig. 6, D–F). These results suggest that a baseline level of JNK activity is required to ensure normal axonal DCV circulation.

Effects of altered JNK activity on DCV transport. (A) Kymographs of DCV transport in motor axons of third instar control and bsk-DN larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Left, directional distributions derived from A. Right, the relative static peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. (C) Axonal pre-bleach intensity of control and bsk-DN third instar larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. Number of analyzed larvae in B and C: control 10, bsk-DN 12. (D) Kymographs of DCV transport in motor axons of second instar control, bsk-DN, and hep-Act larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. (E) Directional distributions derived from D. Right, the relative static peak amplitude for the directional distributions at the left. (F) Axonal pre-bleach intensity of control, bsk-DN, and hep-Act second instar larvae. Scale bar: 10 µm. Number of analyzed larvae in E and F: control 11, bsk-DN 9, and hep-Act 7. Student’s t test (right of B, C, and E), Steel with control test (F, right).