Lysosomes, essential for intracellular degradation and recycling, employ damage-control strategies such as lysophagy and membrane repair mechanisms to maintain functionality and cellular homeostasis. Our study unveils migratory autolysosome disposal (MAD), a response to lysosomal damage where cells expel LAMP1-LC3 positive structures via autolysosome exocytosis, requiring autophagy machinery, SNARE proteins, and cell migration. This mechanism, crucial for mitigating lysosomal damage, underscores the role of cell migration in lysosome damage control and facilitates the release of small extracellular vesicles, highlighting the intricate relationship between cell migration, organelle quality control, and extracellular vesicle release.

Introduction

Lysosomes, membrane-bound organelles in eukaryotic cells equipped with hydrolytic enzymes for biomolecule degradation, are central to intracellular degradation and recycling (Luzio et al., 2007). Lysosomes may suffer damage due to oxidative stress, undigested substrate accumulation, lysosomotropic agents, and lysosomal membrane permeability disruptions (Boya, 2012; Wang et al., 2018). To counteract such damage and preserve lysosome homeostasis, cells implement damage control strategies, including the selective autophagic degradation of compromised lysosomes (lysophagy) and membrane repair mechanisms for minor injuries, ensuring lysosomal functionality and preventing the adverse effects of lysosome accumulation or damage on cellular homeostasis (Hasegawa et al., 2015; Jia et al., 2020; Maejima et al., 2013; Radulovic et al., 2018, 2022).

Autophagy is a crucial lysosomal degradation process vital for recycling damaged organelles and proteins, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis, particularly in stress conditions. This pathway involves the formation of double-membraned autophagosomes by the autophagy machinery. These autophagosomes subsequently fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, where the autophagic cargo is broken down. In addition to indiscriminately degrading cellular contents, autophagy, under specific conditions such as organelle damage, selectively targets organelles like mitochondria, lysosomes, and the endoplasmic reticulum for degradation (Hasegawa et al., 2015; Mizushima, 2020; Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011). Beyond its primary role in degradation, autophagy also supports alternative removal mechanisms, notably secretory autophagy. During this process, instead of being degraded by lysosomal action, autophagic cargoes are expelled from the cell (Kimura et al., 2017; Lane et al., 2017; New and Thomas, 2019; Solvik et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). To date, a series of SNARE proteins have been identified as essential for the release of autophagic cargoes during secretory autophagy (Kimura et al., 2017).

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small, membrane-bound vesicles released into the extracellular space by cells, serving essential roles in intercellular communication, disease progression, and molecular cargo transport. EVs originate through various mechanisms: exosomes are formed via the inward budding of endosomal membranes creating multivesicular bodies (MVBs) that fuse with the plasma membrane to release exosomes, while ectosomes bud directly from the plasma membrane (Hessvik and Llorente, 2018; van Niel et al., 2018). Recent studies have revealed that autophagy can contribute to the release of EVs via secretory autophagy during lysosome inhibition (SALI). SALI enables the secretion of autophagic cargo receptors through extracellular vesicle-associated pathways when standard autophagy-mediated degradation is inhibited. Importantly, blocking autolysosome formation through genetic or chemical interventions significantly increases the SALI, underscoring an adaptive mechanism to maintain cellular functions when conventional autophagy is impaired (Debnath and Leidal, 2022; Solvik et al., 2022). In addition, components of the LC3 conjugation system directs the loading of RNA binding proteins (RBPs) and small non-coding RNAs into extracellular vesicles (EVs), facilitating their expulsion from cells through a process termed LC3-Dependent EV Loading and Secretion (LDELS). Unlike SALI, during LDELS, LC3 localizes to specific areas on the limiting membrane of multivesicular bodies (MVBs). This localization precedes the invagination of MVB membrane that transports LC3 into the cisternae of MVB as intralumenal vesicles (ILVs) (Delorme-Axford and Klionsky, 2020; Leidal et al., 2020).

Cell migration is a crucial process for development, immune responses, and wound healing, allowing cells to relocate within the body (Lauffenburger and Horwitz, 1996). Recent works show cell migration significantly influences EV release; studies reveal that during migration, retraction fibers can fragment into small EVs called retractosomes (Wang et al., 2022). Additionally, large vesicular structures known as migrasomes develop at branching points or termini of retraction fibers in migrating cells; upon fiber disintegration, detached migrasomes are released as a distinct type of migration-dependent large EV (Chen et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2015). The role of migration in the release of other EV types remains an open question. Futhermore, migration has recently been linked to mitochondrial quality control through a mechanism known as mitocytosis. Upon exposure to mild mitochondrial stresses, cells can remove damaged mitochondria by incorporating them into migrasomes. As cells move forward, these mitochondria-containing migrasomes, termed “mitosomes,” are left behind and thus expelled from the cell. Mitocytosis is vital for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and cell viability, especially in highly migratory cells like circulating neutrophils (Jiao et al., 2021). The association of other organelle homeostasis with cell migration remains to be explored.

In this study, we discovered that migrating cells exposed to lysosome-damaging agents form autolysosomes. A portion of these autolysosomes undergo fusion with the basal membrane of the cell, releasing their contents, including small luminal vesicles with markers of exosome. Inhibiting cell migration or the fusion of autolysosomes with the plasma membrane significantly decreases the release of autolysosome contents and leads to an accumulation of damaged lysosomal compartments within the cell. Our findings highlight the surprising roles of cell migration in maintaining lysosomal homeostasis and facilitating the release of small extracellular vesicles (sEVs), thereby establishing a connection between cell migration, EV release, and organelle homeostasis.

Results

Lysosome damage induces extracellular releasing of LAMP1-positive structures

Migrasomes have been shown to evict damaged mitochondria from cells (Jiao et al., 2021). To determine if cells can eject damaged lysosomes through migrasomes, we applied L-Leucyl-L-Leucine methyl ester hydrobromide (LLOMe), a lysosome-damaging agent, to cells. Extended LLOMe exposure led to the formation of LAMP1-positive structures along retraction fibers, which are typically aligned towards the cell’s rear (Hasegawa et al., 2015) (Fig. 1, A and B; and Fig. S1 A). Often, these LAMP1 signals are closely linked with both retraction fibers and migrasomes. After fixation, these extracellular structures can be strongly stained by FM 4-64, suggesting that there are membrane compartments within these structures (Fig. 1 C). Beyond LLOMe, exposure to other lysosomal damage agents, including SiO2 crystals, glycyl-L-phenylalanine 2-naphthylamide (GPN), and monosodium urate (MSU) crystals, also results in the extracellular shedding of LAMP1-positive structures, which indicates that the shedding of LAMP1-positive structures result from lysosome damage (Fig. 1 D).

For detailed observation of LAMP1-positive structure expulsion, we utilized live imaging on cells expressing LAMP1-GFP. Around 13 h post LLOMe treatment, expulsion of LAMP1-GFP positive structures from the cells was noted (Fig. 1 E and Video 1). A closer analysis showed these LAMP1-positive structures become relatively stationary within the cell before being expelled, suggesting that these structures may be tethered to the basal membrane of cells. As the cell moves, it leaves these structures behind, frequently in connection with retraction fibers. In contrast to the expulsion of damaged mitochondria through mitocytosis within migrasomes, these LAMP1-positive structures are not enclosed by TSPAN4-GFP positive migrasome membranes.

To further explore whether LAMP1 signals represent lysosomes within migrasomes, we employed correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM). CLEM revealed that the LAMP1 signals do not denote lysosomes inside migrasomes (Fig. 1 F) as they are not enclosed within the migrasome membrane. Instead, they are vesicles of various sizes and materials possessing the electron density characteristic of lysosome lumens, akin to lysosomes/MVB/autolysosome/amphisomes stripped of their membranes. The LAMP1 signal seems to come from these vesicles as they are the only membrane compartment in the LAMP1-positive extracellular structure, which may represent the intraluminal vesicles of endolysosome related structures, formed by the inward budding of the LAMP1-positive endosome membrane, and damaged lysosomes engulfed in autolysosomes during lysophagy.

Fusion between LAMP1-positive compartments and the basal membrane mediates the extracellular release of LAMP1-positive structures

By serendipity, we discovered that Cyanine5 (Cy5), a fluorophore commonly used for conjugating various biomolecules, can stain these extracellular structures. Cy5 has not been known to directly stain specific cellular components. To understand the nature of this staining pattern, we conducted CLEM. CLEM revealed that Cy5 labels structures resembling the lysosome lumen, given the fact that these extracellular structures are also positive with LAMP1, raises the intriguing possibility that Cy5 can stain the lumen of lysosomes (Fig. 2 A).

Upon analyzing the Cy5 staining pattern in cells, we noted that a subset of TSPAN4-positive intracellular compartments were marked by Cy5. In our previous study, we found that TSPAN4, which is shown to be beside the plasma membrane and in migrasomes, can colocalize with LAMP1. Therefore, this pool of TSPAN4 is likely localized to the late endosome/lysosome. However, untreated cells showed no Cy5 signal in TSPAN4-positive intracellular compartments (Fig. 2 B). Time-lapse imaging indicated the sudden appearance of Cy5 signals within LAMP1-positive compartments, suggesting that these compartments fuse with the basal membrane, leading to the exocytosis of the LAMP1 compartment lumens, which are then stained by Cy5 (Fig. 2 C and Video 2). Following release, the Cy5-positive lumens adhere to the culture dish surface, becoming immobilized “underneath” migrating cells. As cells migrated, Cy5-positive compartments are left behind. Crucially, during this expulsion process, the compartments lost most of the LAMP1 signal on their surface, suggesting that they were exocytosed from the cell via a fusion process. This involves the LAMP1-positive membrane fusing with the plasma membrane, resulting in the extracellular release of the Cy5-labeled lumen.

Z-stack imaging has revealed that most LAMP1, Cy5 positive compartments tend to localize at the bottom of the cell (Fig. S2 A). This observation raises the intriguing possibility that these compartments are exocytosed at the cell’s basal membrane. To investigate this hypothesis further, we conducted time-lapse imaging using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, which only observes a very narrow zone just above the basal membrane. Our observations revealed two distinct groups of Cy5 positive structures: one stationary and the other mobile. The stationary group, which was ultimately left behind, likely represents the lumens of LAMP1-positive compartments that were expelled from the cell at the basal membrane. In contrast, the mobile group seems to consist of LAMP1-positive compartments engaged in dynamic fusion events, where Cy5 presumably enters the compartment through the fusion pore, resulting in Cy5-positivity without expulsion (Fig. 2 D and Video 3).

To directly investigate the fusion of LAMP1-positive compartments with the basal membrane, we engineered a cell line to stably express pHluorin-LAMP1 TransMembrane domain (TM)-mCherry (Fig. 2 E). In these cells, pHluorin-LAMP1 TM-mCherry emits only the mCherry signal within acidic LAMP1-positive organelles such as lysosomes or autolysosomes due to the quenching of the pHluorin signal (Zhao et al., 2019). However, during kiss-and-run fusion events, the influx of culture medium through the fusion pore neutralizes the internal environment, thereby activating the pHluorin signal. Concurrently, Cy5 from the medium also enters, rendering LAMP1-positive structures positive for both pHluorin and Cy5 (Fig. 2 F and Videos 4 and 5). Our observations confirmed this phenomenon, indicating that kiss-and-run fusion indeed occurs. This evidence supports the conclusion that migrating cells expel the lumens of LAMP1-positive compartment through exocytosis, mediated by a fusion mechanism on the basal membrane (Fig. 2 G).

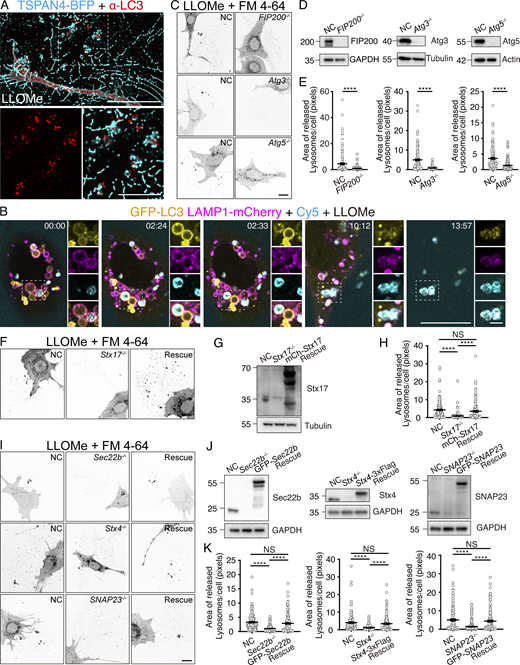

Lysosome damage triggers autophagy-dependent secretion of autolysosomes

Next, we proceeded to elucidate the nature of these extracellular Cy5/LAMP1-positive structures. Given that LLOMe treatment is known to induce lysophagy, we investigated whether these structures are related to autophagy. Staining for LC3 revealed that the extracellular structures were LC3-positive, suggesting that they likely originate from autophagy (Fig. 3 A). By employing cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 and LAMP1-mCherry, we confirmed that these structures indeed originated from autophagy (Fig. 3 B and Video 6). Time-lapse imaging demonstrated that a subset of LC3/LAMP1-positive compartments became Cy5-positive following LLOMe treatment and was subsequently expelled from the cells, indicating that these compartments are autolysosomes.

We further investigated the role of autophagy in the expulsion of damaged lysosomes/autolysosomes using FIP200−/−, Atg3−/−, and Atg5−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). In these autophagy-deficient cells, we noted a marked decrease in the expulsion of extracellular structures, highlighting that this process is dependent on autophagy (Fig. 3, C–E). Moreover, we knocked out Syntaxin17, a SNARE essential for the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes to form autolysosomes and for autophagosome initiation (Hamasaki et al., 2013; Itakura et al., 2012; Jian et al., 2024). The knockout of Syntaxin17 also significantly reduced the expulsion of extracellular structures, a phenomenon that was reversed by re-expressing Syntaxin17 in the knockout cells (Fig. 3, F–H). Collectively, these findings suggest that autolysosomes, dependent on both the autophagic machinery for formation, rather than lysosomes, play a pivotal role in the expulsion of damaged lysosomal compartments induced by LLOMe.

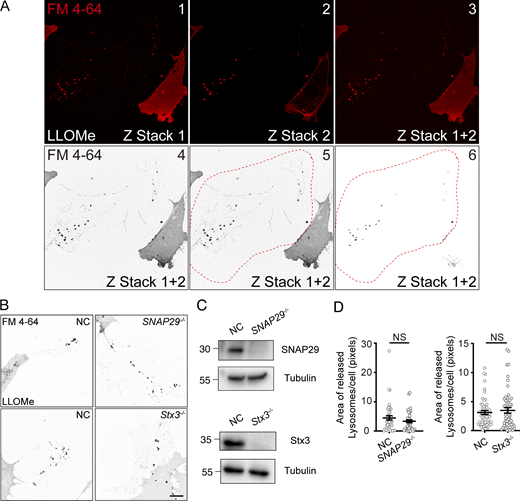

Secretory autophagy is known to be regulated by a specific set of SNARE proteins, including Syntaxin3, Syntaxin4, SNAP23, SNAP29, and Sec22b (Kimura et al., 2017). To identify which SNAREs are essential for the expulsion of damaged lysosomal compartments, we generated knockout cell lines for each of these SNARE proteins. Our findings indicate that Sec22b, Syntaxin4, and SNAP23 are crucial for the expulsion of autolysosomes, as their knockout resulted in a significant decrease in the extracellular lysosomal compartment (Fig. 3, I–K). Conversely, reintroducing these genes into the knockout cells restored the ability to expel the lysosomal compartment. On the other hand, Syntaxin3 and SNAP29 were found to be dispensable for this process (Fig. S3, B–D), which may imply that there are additional mechanisms that spatiotemporally regulate the recruitment of Sec22b, Syntaxin4 and SNAP23 proteins for the fusion of autolysosomes and the plasma membrane during MAD. Together, these results further support the mechanism where lysosomal compartments are expelled from the cell through a SNARE-mediated fusion between autolysosomes and the basal membrane.

Lysosome damage triggers the release of sEV

Autolysosomes result from the fusion of lysosomes and autophagosomes. Additionally, multivesicular bodies (MVBs), a subtype of late endosomes, can fuse with autophagosomes. The detection of small vesicles, ∼50 nm in size, suggests that the intraluminal vesicles of MVBs could also be expelled from cells as exosomes through this pathway. To investigate this possibility, we stained cells with proteins typically enriched in exosomes, such as ALIX and Syntenin-1 (Fig. 4, A and B). Our findings confirmed the presence of both proteins on the extracellular structures. Further detailed analysis using correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM) revealed that these extracellular structures positive for Syntenin-1 contain small vesicles that share the size and morphology characteristic of exosomes (Fig. 4 C). This evidence supports the notion that sEVs similar to exosomes can indeed be released from cells via this pathway.

Autophagy-dependent autolysosome exocytosis is required for the disposal of damaged lysosomal compartments

Up to this point, we have demonstrated that migrating cells are capable of releasing autolysosome contents, including lumen proteins and sEVs, following prolonged exposure to LLOMe. We then investigated whether this expulsion pathway plays a crucial role in maintaining lysosomal homeostasis after lysosomal damage. For this purpose, we employed GFP-Galectin3, a well-established marker for labeling damaged lysosomes (Aits et al., 2015; Paz et al., 2010; Radulovic et al., 2022). In Sec22b, Syntaxin4, and SNAP23 knockout cells, where the expulsion of autolysosomal contents was notably decreased, we observed significantly higher levels of GFP-Galectin3 compared with control cells (Fig. 4, D and E). This finding suggests that this expulsion pathway is essential for the removal of damaged lysosomes.

Migration facilitates the exocytosis of autolysosomes and maintains lysosomal homeostasis in response to lysosomal damage

Finally, we investigated whether cell migration is necessary for the efficient release of autolysosomal contents. Previous research has demonstrated that coating culture slides with fibronectin (FN) significantly enhances cell migration (Huang et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2015). Our findings revealed that fibronectin coating markedly increased the release of extracellular structures. We treated cells with GLPG0187, an integrin inhibitor known to effectively inhibit migration, and Latrunculin A, an inhibitor of G-actin polymerization, to assess the impact of migration on this process (Lu et al., 2020). Inhibition of migration with both reagents resulted in a decrease in the release of these structures (Fig. 4, F and G; and Fig. S4, A and B). Consistently, fibronectin coating led to a reduction in the accumulation of GFP-Galectin3 signal within cells, whereas treatment with GLPG0187 significantly increased the GFP-Galectin3 signal in cells cultured on fibronectin-coated slides (Fig. 4, H and I). These results suggest that migration plays a crucial role in the efficient release of autolysosomal contents, thereby maintaining lysosomal homeostasis.

Discussion

In this study, we found that lysosomal damage induces the formation of autolysosomes, which undergo a fusion with the basal membrane of migrating cells. This fusion leads to the exocytosis of autolysosomes and the disposal of damaged lysosomal compartments. The autophagy machinery, along with a specific set of SNARE proteins essential for secretory autophagy, is crucial for the exocytosis process. Triggered by lysosomal damage, this mechanism facilitates the release of sEVs derived from autolysosomes. Furthermore, it plays a significant role in regulating the level of damaged lysosomes within the cell. In summary, our study uncovers a previously undescribed response to lysosomal damage, wherein cells maintain lysosomal homeostasis through a release mechanism. This mechanism, alongside repair and recycling processes, constitutes a three-pronged response to lysosomal damage. Due to its close association with migration and autolysosome exocytosis, we name this process migratory autolysosome disposal (MAD, Fig. 4 J). Many unicellular organisms are migratory and rely on lysosomal degradation of their prey for survival. Given the diverse environments these organisms inhabit, where various lysosomal stressors are likely encountered, we speculate that this pathway may have arisen early in evolution as a mechanism in unicellular organisms. Future work is needed to test this interesting speculation.

At first glance, MAD shares similarities with SALI as both are initiated by compromised lysosomal function and can result in the release of EVs. However, upon closer examination, the critical distinction between the two pathways becomes apparent. MAD is mediated by autolysosomes, whereas SALI is activated by the inhibition of autophagosome-to-autolysosome maturation (Debnath and Leidal, 2022; Solvik et al., 2022). The reason why lysosomal damage and inhibition of lysosomal activity lead to divergent responses remains unclear. Nevertheless, in both scenarios, autophagic cargo is expelled from the cell, albeit via different routes. This suggests that both pathways might serve a similar physiological purpose despite their mechanistic differences.

A notable discovery from our research is that cell migration markedly enhances the MAD; conversely, when migration is halted, MAD is significantly impeded. Traditionally, cell migration has not been considered a direct contributor to organelle homeostasis. However, this perspective is challenged by recent discoveries related to mitocytosis, where migration plays a crucial role in maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis under mild mitochondrial stress. Although the mechanisms differ significantly, this research presents another instance of how migration is intricately linked to organelle quality control (Ma et al., 2015; Jiao et al., 2021). We speculate that migration could also contribute to the quality control of other organelles, a possibility that future research will need to elucidate.

Currently, the mechanism by which cell migration influences exocytosis is not well understood. However, given the strong link between actin dynamics, especially cortical actin at the plasma membrane, and vesicle fusion, it is reasonable to propose that changes in actin dynamics induced by cell migration could create favorable conditions for enhanced exocytosis. Additionally, the question of why autolysosomes, instead of damaged lysosomes, are preferentially exocytosed following prolonged lysosomal damage warrants consideration. This observation intuitively makes sense, as autophagosomes encasing damaged lysosomes with membrane holes are safer to exocytose. This approach prevents compromising cell membrane integrity, which could occur if damaged lysosomal membranes with holes directly fused with the plasma membrane. One theory is that the notably larger size of autolysosomes increases their likelihood of exocytosis. This increased susceptibility may be due to the physical and geometrical characteristics of larger vesicles, which could naturally promote their release in a manner potentially linked to actin dynamics. On another note, the specific membrane composition of autolysosomes may also make them more amenable to exocytosis. Addressing these questions is essential for advancing our understanding of these processes.

Materials and methods

Antibody

Primary antibodies: Anti-LAMP1 (Anti-Mouse, ab208943, RRID:AB_2923327; Abcam); Anti-LAMP1 (Anti-Human, 328602, RRID:AB_1134259; Biolegend); Anti-α-Tubulin (66031-1-Ig, RRID:AB_11042766; Proteintech); Anti-SNAP23 (10825-1-AP, RRID:AB_2192022; Proteintech); Anti-Syntaxin17 (17815-1-AP, RRID:AB_2255542; Proteintech); Anti-SNAP29 (12704-1-AP, RRID:AB_2192340; proteintech); Anti-Syntaxin4 (ab184545, RRID:AB_2891056; abcam); Anti-Syntaxin3 (ab133750; abcam); Anti-Sec22b (186003, RRID:AB_993020; Synaptic Systems); Anti-Atg3 (3415; CST); Anti-LC3 (PM036, RRID:AB_2274121; MBL); Anti-Syntenin1 (ab19903; Abcam); Anti-ALIX (92880, RRID:AB_2800192; CST); Anti-GAPDH (60004-1-Ig, RRID:AB_2107436; Proteintech); Anti-Atg5 (9980; CST); Anti-FIP200 (12436; CST); Anti-β-Actin (200068-8F10, RRID:AB_2722710; zen).

Secondary antibodies: Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Secondary Antibody Alexa Fluor 633 (A21071, RRID:AB_2535732; Thermo Fisher Scientific); Goat anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (A11001, RRID:AB_2534069; Thermo Fisher Scientific); Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Secondary Antibody (31460, RRID:AB_228341; Thermo Fisher Scientific); Goat anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody (31430, RRID:AB_228307; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Reagents

LLOMe was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, L7393. Cy5 was purchased from Solarbio, S1053. Fm 4-64 was purchased from T3166; Thermo Fisher Scientific. GLPG0187 was purchased from MCE, HY-100506. Fibronectin was purchased from PHE0023; Thermo Fisher Scientific. Silicon dioxide was purchased from S5631; Sigma-Aldrich. Glycyl-L-phenylalanine 2-naphthylamide (GPN) was purchased from 14634; Cayman. Monosodium urate (MSU) was purchased from U2875; Sigma-Aldrich. WGA was purchased from W849; Thermo Fisher Scientific. Vigofect (T001) was purchased from Vigorous.

Cell culture and drug treatment

Both MEF cell line (SCRC-1008; ATCC) and 293FT (RRID:CVCL_6911) cell line were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (C11995500BT; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (CR15140; Cienry), and 1% GlutaMAX (35050-061; Gibco) maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Preparation of LLOMe stock solution was adopted as described before. Silicon dioxide administration was also adopted as described in the reference (Hasegawa et al., 2015). LLOMe stock solution was diluted with cell culture medium and added to cells 2 h after cells were seeded and adhered. Other drugs were utilized to treat cells in almost the same way.

Overexpression plasmids

The overexpression MEF stable cell lines were constructed using PiggyBac Transposon Vector System or pLVX lentivirus overexpression system. Plasmids related with overexpression of TSPAN4, LC3, Galectin3, Syntaxin4, SNAP23, Sec22b, or Syntaxin17 were constructed on the PiggyBac Transposon Vector (RRID:Addgene_210329 & RRID:Addgene_210330). Plasmids related to overexpression of LAMP1 were constructed on pLVX Vector (RRID:Addgene_210337). All the genes mentioned above were cloned from complementary DNA extracted from WT MEF cell strains.

Generation of knockout strains

Knockout MEF cell lines were constructed using CRISPR-Cas9 system. The small guide RNA (sgRNA) was designed at the website of ZHANG Feng’s lab (https://www.zlab.bio/resources). Then sgRNA pairs were constructed onto a modified px458 plasmid vector (provided by Wei Guo, International Campus Zhejiang University, Haining, China) that contains two guide RNAs coupled with Cas9 nuclease. The targeted genome sequence pairs (two sites slicing) are listed below:

FIP200-Target1: 5′-GTACTCGCTGCTTAATCAAG-3′

FIP200-Target2: 5′-GATCACATGAAATCTCCCTC-3′;

Atg3-Target1: 5′-GGAATGCAAGGCTAAAGTAA-3′

Atg3-Target2: 5′-GTGAGGGAAGCATGACAACA-3′;

Sec22b-Target1: 5′-GGGGAAGTATTCTTTCCAAT-3′

Sec22b-Target2: 5′-GCAGTACCATGCCCTAGGTA-3′;

Syntaxin4-Target1: 5′-GTCCTCGCTAGAGGGAAAGG-3′

Syntaxin4-Target2: 5′-GAGGAGAGTAAGCGCT-3′;

SNAP23-Target1: 5′-GTTCTATTCCCAGAGGCAGA-3′

SNAP23-Target2: 5′-GGATCATATGTAGCTCAGGC-3′;

SNAP29-Target1: 5′-GGTATCAGTGGGGTAGAGAT-3′

SNAP29-Target2: 5′-GGTGTGAGCTGTGGCAAGCA-3′;

Syntaxin3-Target1: 5′-GCTAATGCATGTGAAGGCCT-3′

Syntaxin3-Target2: 5′-GGTGTCCACAATGGCACAAG-3′;

Syntaxin17−/− and its wild type MEF cell lines were gifted from RONG Yueguang lab at Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. Atg5−/− and its wild type MEF cell lines were gifted from GE Liang lab at Tsinghua University, Beijing, China.

The sgRNA primers were constructed onto CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid and the plasmids were transfected into wild type MEF cells by electroporation. Transfected cells were sorted with flow cytometry and the single clone cells were cultured. The grown cell colonies were harvested and verified with WB for knockout.

Cell transfection and virus infection

PiggyBac system plasmids and px458-sgRNA plasmids were transfected into MEF cells by electroporation. 3–5 × 105 MEF cells were harvested and transfected with about 6 μg plasmid via Amaxa nucleofector using MEF program A-023 and electroporation solution.

pLVX lentivirus system plasmids were transfected into MEF cells by lentivirus infection. 293FT cell line was utilized to produce virus particles.

Vigofect was used for 293FT cell transfection according to the manufacturer’s manual. 293FT Cells were seeded in a 6-well plate, grown to 80% confluency, and then transfected with 200 ml NaCl (150 mM) that contained 2 ml Vigofect and 5 mg plasmid mixture. Plasmid mixture was composed of pSPAX2, pMD2.5 (two envelope plasmids), and pLVX (target plasmid), and their proportion in mixture was about 3:2:3. The transfection mixture was replaced with fresh medium after 6–8 h.

After another 48 h, the culture medium containing virus particles was harvested and centrifuged (4°C, 500 × g, 5 min). The supernatant was directly used to infect MEF cells mixed with fresh cell culture medium (1:1, V:V) by adding polybrene (8 μg/ml). After about 24-h infection, the virus mixture was replaced with a fresh culture medium and prepared for resistance screening or other use.

Immunofluorescent assay

Cells were cultured and treated with drugs on confocal dishes. Then cells were fixed with 4% PFA (prewarmed to 37°C) at RT for 10 min. Then samples were blocked and permeabilized in PBS/0.02% saponin/10% bovine serum albumin (blocking buffer) at RT for 30 min. Following was incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed three times with PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at RT in the dark. Thee samples were washed three times again with PBS.

Imaging

Confocal dishes were coated with fibronectin for at least 1 h at 37°C. Then cells were seeded and treated. Confocal images were acquired with Nikon A1 HD25 and Nikon AX R with NSPARC microscope (Nikon) with 100× oil-immersion objective at RT (fixed samples) or 37°C (for live cell imaging) using NIS-Elements AR software followed by image deconvolution. Images were reconstructed and analyzed with NIS-Elements AR Analysis software and FIJI ImageJ 64 software (RRID:SCR_002285). TIRF images were acquired with a Nikon A1 HD25 microscope (Nikon) applied with Ti2-LAPP modules.

CLEM

Samples were prepared for confocal imaging first (live-cell imaging or immunofluorescence). After confocal images were captured with the Nikon A1 microscope, samples were then fixed for transmission electronic microscopy in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer and further postfixed in 1% OsO4 + 1.5% potassium ferricyanide in ddH2O followed by en bloc staining using 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate RT in the dark. Samples were dehydrated in ascending ethanol series (50/70/80/90/100/100/100) and embedded in Pon812 resin. Serial ultrathin sections (60–70 nm) were obtained via a Leica UC7 ultramicrotome, and the sections were collected on slot grids then imaged by a Hitachi HT-7800 120 kV transmission electron microscope.

Western blotting

Parasite pellets were resuspended in 2% SDS/TBS and then boiled at 95°C for 15 min. After Bicinchoninic acid protein assay (23227; Thermo Fisher Scientific), they were run on a precast 15% SDS-PAGE gradient gel (YEASEN) and transferred onto a PVDF (ISEQ00010; Millipore). The membrane was blocked in 5% milk, PBS/0.2% Tween-20 for 1 h at RT. Primary antibodies were added in Solution I (NKB-201; TOYOBO) with 1:1,000 dilution, and the samples were incubated overnight. The membrane was then washed three times with TBS/0.2% Tween. Secondary antibodies were added in antibody solution buffer (WB100D; New Cell & Molecular Biotech Co.). The incubation lasted for 1 h at RT followed by three washes with PBS/0.2% Tween. The signal was detected and quantified with ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (ChemiDoc MP, RRID:SCR_021693; BioRAD) using the SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (34076; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis based on imaging

Cell number was counted and seeded cell number was controlled at the same for samples for statistics. Samples were captured with confocal microscopy first, with or without FM 4-64 or Cy5 Staining. The amount of extracellular MAD cargoes was based on FM 4-64 or Cy5 staining, analyzed with FIJI. Z-stack images (interval in Z was 1 μm) were projected in max intensity and then converted to eight-bit format (gray-value mode). The threshold of the intensity was adjusted to reduce the basal intensity level of the culture medium stained with Cy5 or of the retraction fiber stained with FM 4-64 (Fig. S3 A). The intensity thresholds of different groups were set to the same level in every replicated experiment. The extracellular region was marked as the region of interest and the area in the region was measured as the amount of MAD cargoes.

The amount of intracellular galectin3 puncta was measured and analyzed by using NIS-Elements AR Analysis software. NIS.ai AI module for microscopes (Segment.ai) was utilized to recognize galectin3 puncta and then different parameters were analyzed by NIS-Elements AR Analysis software automatically. The AI module was pretrained by our own data before all the data was analyzed.

Unpaired Two-side T test was applied for most statistics, *P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 (related to Fig. 1) shows the representative images of the extracellular LAMP1 signal released by the MEF cell line when treated with gradient concentrations of LLOMe. Fig. S2 (related to Fig. 2) shows the representative 3D-constructed images of extracellular lysosome structures of MEF cell line treated with LLOMe, marked with Cy5, captured at different Z stacks, and reconstructed in 3D-mode. Fig. S3 (related to Fig. 3) shows the process of image analysis during statistics of extracellular lysosome structures marked with FM 4-64, and statistic results of the amount of released lysosomes of SNAP29−/− and Syntaxin3−/− MEF treated with LLOMe. Video 1 (related to Fig. 1) shows the process where TSPAN4-mCherry (red) LAMP1-GFP (cyan) MEF stable cell line treated with 2 mM LLOMe released LAMP1-postive structures. Video 2 (related to Fig. 2) shows the process where structures released from intracellular LAMP1 (red)-positive vesicles stained by extracellular Cy5 (cyan), during 2 mM-LLOMe treatment. Video 3 (related to Fig. 2) shows the process where MEF cell line treated with 2 mM LLOMe released structures stained by extracellular Cy5 (cyan), captured with TIRF. Video 4 (related to Fig. 2) shows the phenomenon when pHluorin (yellow)-LAMP1 TM-mCherry (magenta) MEF cell line treated with 0 mM LLOMe and Cy5 (cyan). Video 5 (related to Fig. 2) shows the fusion process where pHluorin (yellow)-LAMP1 TM-mCherry (magenta) MEF cell line treated with 2 mM LLOMe and Cy5 (cyan). Video 6 (related to Fig. 3) shows the fusion process between autolysosomes and basal plasma membranes when GFP-LC3 (yellow) LAMP1-mCherry (magenta) MEF cell line treated with 2 mM LLOMe and Cy5 (cyan).

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely show our gratefulness to the State Key Laboratory of Membrane Biology, and Jinyu Wang and Huizhen Cao (SLSTU-Nikon Biological Imaging Center) for confocal microscopy imaging and other facility support.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32330025, 92354306 and 32030023), Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission, Administrative Commission of Zhongguancun Science Park (grant no. Z221100003422012), Tsinghua University Dushi Program (grant no. 20241080003), and Tsinghua-Toyota Joint Research Fund (grant no. 20233930058).

Author contributions: T. Sho: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing, Y. Li: Methodology, Resources, H. Jiao: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing, L. Yu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

References

Author notes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests exist.