Autoimmune vasculitis is a group of life-threatening diseases, whose underlying pathogenic mechanisms are incompletely understood, hampering development of targeted therapies. Here, we demonstrate that patients suffering from anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)–associated vasculitis (AAV) showed increased levels of cGAMP and enhanced IFN-I signature. To identify disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets, we developed a mouse model for pulmonary AAV that mimics severe disease in patients. Immunogenic DNA accumulated during disease onset, triggering cGAS/STING/IRF3-dependent IFN-I release that promoted endothelial damage, pulmonary hemorrhages, and lung dysfunction. Macrophage subsets played dichotomic roles in disease. While recruited monocyte-derived macrophages were major disease drivers by producing most IFN-β, resident alveolar macrophages contributed to tissue homeostasis by clearing red blood cells and limiting infiltration of IFN-β–producing macrophages. Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of STING, IFNAR-I, or its downstream JAK/STAT signaling reduced disease severity and accelerated recovery. Our study unveils the importance of STING/IFN-I axis in promoting pulmonary AAV progression and identifies cellular and molecular targets to ameliorate disease outcomes.

Introduction

Recognition of cytosolic DNA by the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)/stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway is a key process in anti-viral immunity resulting in the release of type I IFN (IFN-I), TNF-α, and IL-6 (Barrat et al. 2016; Motwani et al. 2019; Gao et al., 2013; Ishikawa and Barber, 2008; Wu et al., 2013). Since these cytokines have an important pro-inflammatory role in different autoimmune diseases, it is conceivable that DNA released from stressed cells may activate nucleic acid sensing pathways and worsen disease progression. Aberrant DNA release is indeed characteristic of several autoimmune diseases including anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)–associated vasculitis (AAV; Kessenbrock et al., 2009; Sangaletti et al., 2012; Surmiak et al., 2015), thus posing the question whether the cGAS/STING pathway is promoting AAV progression.

AAV encompasses various diseases characterized by high levels of pathogenic ANCAs, mostly directed against myeloperoxidase (MPO) or proteinase 3, accumulation of extracellular DNA at the sites of injury, and necrotizing inflammation of small and intermediate vessels (Jennette and Falk. 1997; Kessenbrock et al., 2009; O’Sullivan et al., 2015; Kitching et al., 2020). AAV is a systemic disease that often manifests in the aftermath of bacterial infections (Timmeren et al. 2014). Due to the scarce knowledge on underlying pathological mechanisms, current therapies are based on broad immunosuppression, which has significantly lowered mortality in AAV patients (Rich and Brown, 2012) at the expense of considerable side effects of long-term corticosteroid administration. For example, infections have become the main primary cause of death within the first year of diagnosis (47%), whereas active vasculitis itself accounts for a lower fraction of mortality (19%). The high rate of infection-related mortality together with other severe side effects (Flossmann et al., 2011; Little et al., 2010) warrant for the identification of disease pathways that can be the basis for development of novel, selective therapies.

Central to this question is the availability of robust pre-clinical models to identify key molecular and cellular mechanisms driving AAV progression (Jennette et al., 2013). Existing mouse models based on active or passive immunization against MPO have been instrumental in uncovering the pathogenic role of anti-MPO Ig (Xiao et al., 2002; Schreiber et al., 2006; Little et al., 2009) and the C5a–C5aR axis (Jayne et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2014), as well as defining the contribution of neutrophils (Xiao et al., 2005), monocytes (Rousselle et al. 2017; Rousselle et al., 2022), and T cells (Gan et al., 2010). However, the high variability in disease incidence and severity inherent to those animal models considerably limits their impact on identifying novel therapeutic targets (Gan et al., 2015; Shochet et al. 2020). In addition, although hemorrhages in the lung are amongst the most life-threatening features of small- and medium-vessel AAV (Jennette and Falk, 1997), none of the available mouse models are associated with significant pulmonary involvement. The establishment of a reproducible and clinically relevant mouse model for severe autoimmune vasculitis is thus necessary for the identification of disease mechanisms that can be therapeutically targeted.

Here, we report in two independent patient cohorts that active AAV is associated with increased 2′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) levels and an IFN-I signature in blood peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), suggesting an active pathway of DNA sensing mediated by cGAS/STING/IFN-I. To investigate this, we established an ANCA-dependent mouse model of severe pulmonary hemorrhages resembling clinical features of life-threatening AAV. Using this AAV animal model, we demonstrate a role of cGAS/STING/IRF3 pathway in disease pathogenesis by promoting IFN-I release and endothelial cell damage. In addition, we identify a functional dichotomy between lung macrophages whereby recruited monocyte-derived macrophages promoted disease progression by producing most IFN-I, while resident alveolar macrophages (AMs) had homeostatic function by clearing hemorrhages. Therapeutic intervention to inhibit STING activation, IFN-I recognition, or JAK1/2 signaling improved disease outcome. Thus, our results identify the STING/IFN-I axis of nucleic acid recognition as a potential therapeutic target to ameliorate AAV.

Results

Increased cGAMP levels and IFN-I signature in patients with ANCA vasculitis

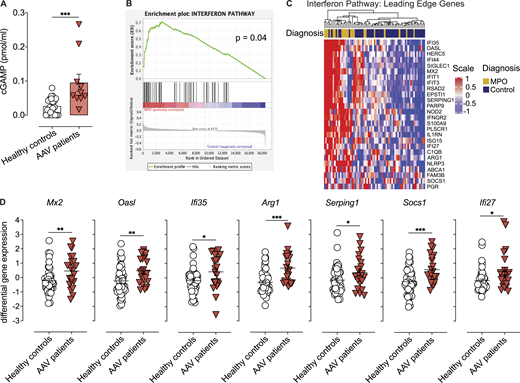

Patients with anti-MPO-associated vasculitis have increased numbers of netting neutrophils at the sites of injury that release MPO-decorated DNA (Kessenbrock et al., 2009). However, the contribution of DNA sensing in disease pathogenesis is unknown. Here, we found increased cGAMP concentration in the PBMCs of patients undergoing active ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1 A and Table S1), suggesting ongoing DNA recognition by the cGAS/STING pathway, although a contribution of bacterial-derived cGAMP (Kranzusch 2019) cannot be formally ruled out. Further supporting STING activation, we demonstrate an increased IFN-I signature during active disease in an independent cohort of patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis with similar clinical characteristics (Fig. 1, B and C; and Table S2). Hallmark IFN-I– induced genes including Mx2, Oasl, Ifi27/35, and Arg1 amongst others were upregulated in patients undergoing active vasculitis (Fig. 1, C and D). These results suggest a potential role of STING activation in disease progression of patients with active MPO-associated small-vessel vasculitis.

Patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis show increased cGAS activation and IFN-I signature. (A) cGAMP concentration in PBMCs isolated from healthy donors or patients with active anti-MPO-associated vasculitis (patient cohort I; Table S1). Each dot is an individual donor (n = 22 for healthy, n = 10 for MPO-vasculitis donors). Columns represent mean ± SEM. (B) GSEA in patients undergoing active anti-MPO-associated vasculitis (n = 21, patient cohort II; Table S2). (C) Heatmap of IFN-I pathway leading-edge gene expression levels in patients with active anti-MPO-associated vasculitis (MPO, n = 21) or in remission (Control, n = 47; patient cohort II). (D) Expression levels for selected ISGs from analysis in C. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (A and D) and familywise-error rate (B) *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis show increased cGAS activation and IFN-I signature. (A) cGAMP concentration in PBMCs isolated from healthy donors or patients with active anti-MPO-associated vasculitis (patient cohort I; Table S1). Each dot is an individual donor (n = 22 for healthy, n = 10 for MPO-vasculitis donors). Columns represent mean ± SEM. (B) GSEA in patients undergoing active anti-MPO-associated vasculitis (n = 21, patient cohort II; Table S2). (C) Heatmap of IFN-I pathway leading-edge gene expression levels in patients with active anti-MPO-associated vasculitis (MPO, n = 21) or in remission (Control, n = 47; patient cohort II). (D) Expression levels for selected ISGs from analysis in C. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (A and D) and familywise-error rate (B) *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Combination of bacterial ligands and anti-MPO antibodies provokes severe lung hemorrhages and dysfunction in a novel mouse model

To investigate pathophysiological mechanisms driving small vessel autoimmune vasculitis, we aimed at establishing a novel mouse model of severe ANCA-induced vasculitis in the lung, which is the most critical disease manifestation in patients (Jennette and Falk, 1997; Fig. 2 A).

Anti-MPO antibodies and low-dose bacterial ligands induce severe pulmonary vasculitis in a novel mouse model of pulmonary vasculitis. (A) Schematic of AAPV induction. Anti-MPO, monoclonal antibodies 6D1 and 6G4. (B) H&E staining of lung cryosections 3d after disease induction from the indicated mouse groups. Scale bar = 500 µm. (C and D) Lung injury score (0–4) quantified from H&E lung cryosections. (E–H) Representative photographs (E) and quantification (F–H) of pulmonary hemorrhages in BALF. Treatments and time points as indicated. (I) Light-sheet fluorescence microscope images from clarified left lungs isolated from mice treated as indicated and injected with Texas red–labeled albumin. Shown is a representative of two mice. Scale bar = 1 mm. (J–L) Kinetics of weight change (J), SpO2 (%) in peripheral blood (K), and survival (L) of mice as indicated in A. (M–O) Flow cytometric quantification (M and N) and UMAP dimensionality reduction plots (O) of immune cells in BALF. Cell identity gates are shown in Fig. S2. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Shown is mean ± SEM. Unless otherwise stated, shown are pooled data from three experiments (C, D, F, G, H, J, M and N, n = 11–17 mice/group) or two experiments (K, n = 10 mice/group); α-MPO group shows a total of five (C, G, H, J, L, and M) mice. Asterisks indicate the significance level of one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (C, D, F–H, M, and N) or two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s’ multiple comparisons test (J and K) and curve comparison with log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test (L). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. OD, OD400–OD600.

Anti-MPO antibodies and low-dose bacterial ligands induce severe pulmonary vasculitis in a novel mouse model of pulmonary vasculitis. (A) Schematic of AAPV induction. Anti-MPO, monoclonal antibodies 6D1 and 6G4. (B) H&E staining of lung cryosections 3d after disease induction from the indicated mouse groups. Scale bar = 500 µm. (C and D) Lung injury score (0–4) quantified from H&E lung cryosections. (E–H) Representative photographs (E) and quantification (F–H) of pulmonary hemorrhages in BALF. Treatments and time points as indicated. (I) Light-sheet fluorescence microscope images from clarified left lungs isolated from mice treated as indicated and injected with Texas red–labeled albumin. Shown is a representative of two mice. Scale bar = 1 mm. (J–L) Kinetics of weight change (J), SpO2 (%) in peripheral blood (K), and survival (L) of mice as indicated in A. (M–O) Flow cytometric quantification (M and N) and UMAP dimensionality reduction plots (O) of immune cells in BALF. Cell identity gates are shown in Fig. S2. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Shown is mean ± SEM. Unless otherwise stated, shown are pooled data from three experiments (C, D, F, G, H, J, M and N, n = 11–17 mice/group) or two experiments (K, n = 10 mice/group); α-MPO group shows a total of five (C, G, H, J, L, and M) mice. Asterisks indicate the significance level of one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (C, D, F–H, M, and N) or two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s’ multiple comparisons test (J and K) and curve comparison with log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test (L). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. OD, OD400–OD600.

Systemic application of two murine anti-MPO monoclonal antibodies (Fayçal et al., 2022; Fig. S1 A) into C57BL6/J mice failed to induce lung pathology (Fig. 2 B), consistent with two previously described publications with other polyclonal anti-MPO Ig (Shochet et al. 2020) as well as in kidney, liver, or skin (data not shown). Given that preceding bacterial infections often trigger ANCA vasculitis episodes in patients (Timmeren et al. 2014) by mobilizing and activating neutrophils (Huugen et al., 2005), we applied a combination of anti-MPO IgG together with low doses of bacterial ligands fMLP and LPS. Indeed, this caused marked pulmonary pathology characterized by large inflammatory cellular infiltrates and hemorrhages (Fig. 2 B; and Fig. S1, B and C). Severe and long-lasting lung damage was specific to the combined application, whereas single components did not suffice (Fig. 2, C and D; and Fig. S1 D). fMLP and LPS locally applied into the lung synergistically enhanced neutrophil mobilization (Fig. S1 E) and activation (Fig. S1 F), providing a mechanistic basis for the synergy with anti-MPO IgG for ANCA-associated pulmonary vasculitis (AAPV) induction.

Anti-MPO antibodies and low dose bacterial ligands synergize to induce severe pulmonary vasculitis in a novel mouse model of pulmonary vasculitis. (A) ELISA for recombinant MPO with the mAb clones 6D1 and 6G4 indicating specificity for mouse MPO. (B and C) H&E stainings of lung cryosections of mice treated as in Fig. 2 A. Yellow arrowheads indicate areas with hemorrhages. Scale bar = 500 µm (B), 100 µm (C). (D) Lung injury score 7 d after treatment of mice as in Fig. 2 A. (E) Quantitative flow cytometry analysis of circulating neutrophils in blood of wild-type mice 6 h after indicated treatments. (F) Representative flow cytometric histograms (left) and quantification of ROS production (DHR123 mean flourescence intensity [MFI]) by blood neutrophils from mice treated as in E. pos, positive control (PMA); neg, fluorescence minus one for DHR123 in untreated neutrophils. (G–J) RBC (G–I) and leukocyte (J) counts in BALF of the indicated mice. (K) UMAP dimensionality reduction of immune cells in BALF of mice treated only with anti-MPO antibodies using identity gates in Fig. S2. Results for individual mice are shown as dots. Data is representative of at least two independent experiments (mean ± SEM). Asterisks indicate the significance level of one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (D–G, I, and J). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Anti-MPO antibodies and low dose bacterial ligands synergize to induce severe pulmonary vasculitis in a novel mouse model of pulmonary vasculitis. (A) ELISA for recombinant MPO with the mAb clones 6D1 and 6G4 indicating specificity for mouse MPO. (B and C) H&E stainings of lung cryosections of mice treated as in Fig. 2 A. Yellow arrowheads indicate areas with hemorrhages. Scale bar = 500 µm (B), 100 µm (C). (D) Lung injury score 7 d after treatment of mice as in Fig. 2 A. (E) Quantitative flow cytometry analysis of circulating neutrophils in blood of wild-type mice 6 h after indicated treatments. (F) Representative flow cytometric histograms (left) and quantification of ROS production (DHR123 mean flourescence intensity [MFI]) by blood neutrophils from mice treated as in E. pos, positive control (PMA); neg, fluorescence minus one for DHR123 in untreated neutrophils. (G–J) RBC (G–I) and leukocyte (J) counts in BALF of the indicated mice. (K) UMAP dimensionality reduction of immune cells in BALF of mice treated only with anti-MPO antibodies using identity gates in Fig. S2. Results for individual mice are shown as dots. Data is representative of at least two independent experiments (mean ± SEM). Asterisks indicate the significance level of one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (D–G, I, and J). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Concomitant with lung pathology, combination of bacterial ligands plus the monoclonal anti-MPO IgG antibodies resulted in hemorrhages in the lung (Fig. 2 E), mimicking the clinical hallmark of severe pulmonary vasculitis in patients (Jennette and Falk, 1997). Blood accumulation in the bronchoalveolar space started as soon as 6 h after disease induction, peaked by day 3, and was partially resolved by day 7 (Fig. 2, E and F; and Fig. S1 G). Anti-MPO antibodies or bacterial ligands alone did not result in pulmonary hemorrhages (Fig. 2, G and H; and Fig. S1, H and I). Consistent with this, light-sheet microscopy of whole lungs showed widespread vessel leakage in the lungs of mice with active AAPV (Fig. 2 I). These findings were reflected by decreased mouse well-being (Fig. 2 J) and impaired lung function (Fig. 2 K), resulting in mortality of up to 20% of the mice (Fig. 2 L).

Combination of microbial ligands and anti-MPO monoclonal antibodies induced also a much stronger infiltration of immune cells into the bronchoalveolar space than the individual components on their own (Fig. 2 M; and Fig. S1, J and K). Immune cell infiltration peaked on day 3 after vasculitis induction, with neutrophils comprising most of the cellular infiltrate, and was strongly decreased by day 7 (Fig. 2, N and O, and Fig. S2) when pulmonary hemorrhages were resolving (Fig. 2 F).

Cell identity gates used in this study. Hierarchy of flow cytometry dot plots and gates of lung singe-cell suspensions from wild-type mice 3 d after AAPV induction used to identify different cell populations. Leukocytes: single Hoechst33258− CD45+ events. Red blood cells: single Hoechst33258− CD45− Ter119+ events. Eosinophils: CD11b+ CD11c− Siglec-F+ Ly-6G− leukocytes. Neutrophils: CD11b+ CD11c− Siglec-F−/+ Ly-6G+ leukocytes. Monocytes: CD11b+ CD11c− Siglec-F− Ly-6G− NK1.1− Ly-6B+ leukocytes. Alveolar macrophages (Alv. Møs): CD11c+ Siglec-Fhi CD11b−/int leukocytes. Inflammatory (Infl.) Møs: CD11c+ Siglec-Fint CD11bint/hi leukocytes. cDC1: Siglec-F− CD11c+ MHC-II+ CD103+ CD11b− leukocytes. cDC2/mo-DCs: Siglec-F− CD11c+ MHC-II+ CD103− CD11b+ leukocytes. B cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε− CD19+ leukocytes. CD4 α/β T cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1− CD8− CD4+ leukocytes. CD8 α/β T cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1− CD8+ CD4− leukocytes. DN α/β T cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1− CD8− CD4− leukocytes. ɣδ T cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε + CD19− TCRβ− ɣδ TCR+. Natural killer (NK) cells: CD11c− CD11b−/+ CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1+ leukocytes. NKT cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1+ leukocytes.

Cell identity gates used in this study. Hierarchy of flow cytometry dot plots and gates of lung singe-cell suspensions from wild-type mice 3 d after AAPV induction used to identify different cell populations. Leukocytes: single Hoechst33258− CD45+ events. Red blood cells: single Hoechst33258− CD45− Ter119+ events. Eosinophils: CD11b+ CD11c− Siglec-F+ Ly-6G− leukocytes. Neutrophils: CD11b+ CD11c− Siglec-F−/+ Ly-6G+ leukocytes. Monocytes: CD11b+ CD11c− Siglec-F− Ly-6G− NK1.1− Ly-6B+ leukocytes. Alveolar macrophages (Alv. Møs): CD11c+ Siglec-Fhi CD11b−/int leukocytes. Inflammatory (Infl.) Møs: CD11c+ Siglec-Fint CD11bint/hi leukocytes. cDC1: Siglec-F− CD11c+ MHC-II+ CD103+ CD11b− leukocytes. cDC2/mo-DCs: Siglec-F− CD11c+ MHC-II+ CD103− CD11b+ leukocytes. B cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε− CD19+ leukocytes. CD4 α/β T cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1− CD8− CD4+ leukocytes. CD8 α/β T cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1− CD8+ CD4− leukocytes. DN α/β T cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1− CD8− CD4− leukocytes. ɣδ T cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε + CD19− TCRβ− ɣδ TCR+. Natural killer (NK) cells: CD11c− CD11b−/+ CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1+ leukocytes. NKT cells: CD11c− CD11b− CD3ε+ CD19− TCRβ+ NK1.1+ leukocytes.

In conclusion, we present here a novel and reproducible model of AAPV that mimics clinical hallmarks of severe lung manifestations in patients.

STING activation promotes autoimmune pulmonary vasculitis

Having identified increased cGAMP concentration in patients undergoing active vasculitis, we next investigated whether DNA sensing by the cGAS/STING pathway was important for pathogenesis in our mouse AAPV model. We observed extracellular DNA accumulation in the bronchoalveolar space of mice undergoing AAPV (Fig. 3 A) in kinetics that closely correlated with the amount of blood in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL; Fig. 2 F). This DNA had mostly a genomic rather than mitochondrial origin during the early phases of disease induction (Fig. 3 B). While fMLP/LPS treatment alone caused a similar increase in extracellular DNA concentration compared to mice undergoing AAPV (Fig. 3 A), it was clearly not sufficient to induce lung pathology (Fig. 2, B and G), highlighting the necessity of anti-MPO IgG for severe disease progression. Indeed, the anti-MPO antibodies used in this study were able to bind to the extracellular DNA released from in vitro activated neutrophils (Fig. 3 C), suggesting that DNA/MPO/IgG immune complexes played a pathogenic role.

STING promotes progression of AAPV. (A) Cell-free DNA in the BALF of mice treated as indicated. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Data is representative of two experiments and 3–4 mice/group. (B) Cell-free mtDNA (16S or Nd1) to nuclear (n) DNA (HK29) ratio obtained by qRT-PCR in BALF of AAPV mice at the indicated time points after disease induction. Data is representative of two independent experiments (n = 3–5 mice/group). (C) Confocal microscopy images of neutrophils treated as indicated and stained with anti-MPO mAbs. Scale bar, 50 µm. Arrowheads indicate extracellular MPO-decorated DNA. (D) Gel electrophoresis of gDNA, DNA isolated from BALF of mice 3 d after treatment as indicated, or 60mer TREX1-protected phosphorylated DNA treated or not with DNases ex vivo as indicated. Data is representative of two experiments with pooled DNA isolated from three mice per group. (E) cGAS activation assay using recombinant cGAS, ATP, and either dsDNA (lane 2), gDNA (lane 13), or DNA isolated from the BALF of mice treated 3 d earlier with LPS (lanes 3–5), fMLP/LPS (lanes 6–8) or fMLP/LPS + anti-MPO (lanes 9–12). Each lane represents an independent DNA sample. (F) cGAMP quantification in the BALF of mice treated as indicated 3 d earlier. Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 5-14 mice/group), each dot representing a single mouse. LOD, limit of detection. (G) Schematic of experimental design in wild-type or Stinggt/gt mice. (H and I) Kinetics of weight change (H) and SpO2 (%) in peripheral blood (I) of mice treated as in G. Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 10 [H] or 5 [I] mice/group). (J) Confocal microscopy images of unfixed vibratome lung slices showing alveoli (a) and a medium-sized pulmonary blood vessel (v) stained in vivo with anti-CD31 and ex vivo with propidium iodide. Scale bar = 100 µm. (K) Representative photographs and quantification of pulmonary hemorrhages in BALF. Treatments and time points as in G. Shown are pooled data from three independent experiments (n = 11–13 mice/group). (L) H&E staining of lung sections and lung injury score (0–4) for mice treated as indicated. Each dot is an individual mouse from two pooled independent experiments (n = 5–9 mice/group). Scale bar, 500 µm. Bars and line graphs represent mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (F and K), one-way ANOVA with Kurskal–Wallis multiple comparisons test (B) or Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (L) and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (A, H, and I). *P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.***, P < 0.001.

STING promotes progression of AAPV. (A) Cell-free DNA in the BALF of mice treated as indicated. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Data is representative of two experiments and 3–4 mice/group. (B) Cell-free mtDNA (16S or Nd1) to nuclear (n) DNA (HK29) ratio obtained by qRT-PCR in BALF of AAPV mice at the indicated time points after disease induction. Data is representative of two independent experiments (n = 3–5 mice/group). (C) Confocal microscopy images of neutrophils treated as indicated and stained with anti-MPO mAbs. Scale bar, 50 µm. Arrowheads indicate extracellular MPO-decorated DNA. (D) Gel electrophoresis of gDNA, DNA isolated from BALF of mice 3 d after treatment as indicated, or 60mer TREX1-protected phosphorylated DNA treated or not with DNases ex vivo as indicated. Data is representative of two experiments with pooled DNA isolated from three mice per group. (E) cGAS activation assay using recombinant cGAS, ATP, and either dsDNA (lane 2), gDNA (lane 13), or DNA isolated from the BALF of mice treated 3 d earlier with LPS (lanes 3–5), fMLP/LPS (lanes 6–8) or fMLP/LPS + anti-MPO (lanes 9–12). Each lane represents an independent DNA sample. (F) cGAMP quantification in the BALF of mice treated as indicated 3 d earlier. Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 5-14 mice/group), each dot representing a single mouse. LOD, limit of detection. (G) Schematic of experimental design in wild-type or Stinggt/gt mice. (H and I) Kinetics of weight change (H) and SpO2 (%) in peripheral blood (I) of mice treated as in G. Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 10 [H] or 5 [I] mice/group). (J) Confocal microscopy images of unfixed vibratome lung slices showing alveoli (a) and a medium-sized pulmonary blood vessel (v) stained in vivo with anti-CD31 and ex vivo with propidium iodide. Scale bar = 100 µm. (K) Representative photographs and quantification of pulmonary hemorrhages in BALF. Treatments and time points as in G. Shown are pooled data from three independent experiments (n = 11–13 mice/group). (L) H&E staining of lung sections and lung injury score (0–4) for mice treated as indicated. Each dot is an individual mouse from two pooled independent experiments (n = 5–9 mice/group). Scale bar, 500 µm. Bars and line graphs represent mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (F and K), one-way ANOVA with Kurskal–Wallis multiple comparisons test (B) or Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (L) and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (A, H, and I). *P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.***, P < 0.001.

Extracellular DNA fragments displaying characteristics of apoptotic DNA laddering were detected in the bronchoalveolar space of fMLP/LPS-treated or AAPV mice (Fig. 3 D), indicating release and partial degradation of DNA during inflammation. Despite its susceptibility to TREX1- and DNase1-mediated degradation (Fig. 3 D), the released DNA had the capacity to activate the DNA sensor, cGAS, as demonstrated by cGAMP generation using a sensitive cell-free assay with recombinant cGAS and 32P-labeled ATP (Civril et al., 2013), independent of anti-MPO administration (Fig. 3 E). These data indicate that extracellular immunogenic DNA accumulated in the lung of mice treated with bacterial ligands and that anti-MPO antibodies were required for disease progression, suggesting that DNA/MPO/IgG complexes were required to deliver extracellular immunogenic DNA to the cytosol for cGAS activation, although a role for cytosolic DNA cannot be ruled out.

Consistent with our findings in patients (Fig. 1 A), we observed that 50% of mice in the AAPV group had cGAMP levels above detection level, whereas none of the mice treated only with bacterial ligands did (Fig. 3 F), supporting in vivo cGAS activation during AAPV. To validate the contribution of cGAS/STING pathway, we compared vasculitis induction in wild-type (C57BL/6J) and Stinggt/gt mice expressing non-functional STING (Fig. 3 G). Deficiency in functional STING prevented the AAPV-induced weight loss observed in WT mice (Fig. 3 H) and restored lung function 6 d after disease induction compared to WT mice, which still showed decreased blood oxygenation at that time point (Fig. 3 I). Consistent with these findings, functional STING promoted endothelial cell death during AAPV induction (Fig. 3 J), leading to more severe pulmonary hemorrhages (Fig. 3 K) and lung histopathology (Fig. 3 L). We thus conclude that DNA recognition via the cGAS/STING pathway promoted lung injury and hemorrhages resulting in decreased pulmonary function.

IFN-I is required for ANCA pulmonary vasculitis

STING activation following cGAS-mediated DNA recognition generally results in signaling via TBK1/IRF3 and IFN-β expression (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008; Motwani et al. 2019). Consistent with our findings of increased IFN-I signature in patients (Fig. 1, B–D), we hypothesized that IFN-I plays a pathological role in ANCA vasculitis. Indeed, we observed increased Ifnβ expression (Fig. 4 A) and IFN-I signature at the peak of vasculitis, as demonstrated by the upregulation of different IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) in the lungs of mice with AAPV (Fig. 4 B and Fig. S3 A). Stinggt/gt mice expressed lower pulmonary Ifnβ levels after vasculitis induction than their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 4 C), indicating that STING promoted Ifnβ production. Consequently, Stinggt/gt mice showed reduced ISGs expression after induction of pulmonary vasculitis (Fig. 4 D). Within the analyzed ISGs, we found also Oasl1, Cxcl10, and Mx-1 to be increased during disease progression (Fig. S3 A), albeit in a STING-independent manner (Fig. S3 B), likely due to IFN-I–unrelated inflammatory cues (Schneider et al. 2014).

IFNAR-1 and IRF3 promote severe anti-MPO-associated pulmonary vasculitis. (A–D) Relative expression of Ifnβ gene (A and C) and indicated ISGs (B and D) at different time points after AAPV induction in wild-type mice (A and B) or on day 3 in the indicated mice (C and D). Each dot is an individual mouse. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 4–9 mice/group). (E) Schematic representation of experiment with IFNAR-1 blocking antibodies. (F–I) Weight change (F), hemorrhages in BALF (G), leukocyte counts (H), and lung injury score (I) in wild-type mice treated as indicated. Each dot is an individual mouse. Shown are pooled results from two independent experiments (n = 5–12 mice/group). (J) Schematic representation of experiments with Irf3−/− mice. (K–M) Weight change (K), hemorrhages in BALF (L), and leukocyte counts (M) in wild-type and Irf3−/− mice treated as indicated. Each dot is an individual mouse. Shown are pooled results from two independent experiments (n = 3–7 mice/group) or a representative of two independent experiments (M, n = 3–5 mice/group). Bars and line graphs represent mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (H, I, and M), one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (A and B) or Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (G and L) and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (C, D, F, and K). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

IFNAR-1 and IRF3 promote severe anti-MPO-associated pulmonary vasculitis. (A–D) Relative expression of Ifnβ gene (A and C) and indicated ISGs (B and D) at different time points after AAPV induction in wild-type mice (A and B) or on day 3 in the indicated mice (C and D). Each dot is an individual mouse. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 4–9 mice/group). (E) Schematic representation of experiment with IFNAR-1 blocking antibodies. (F–I) Weight change (F), hemorrhages in BALF (G), leukocyte counts (H), and lung injury score (I) in wild-type mice treated as indicated. Each dot is an individual mouse. Shown are pooled results from two independent experiments (n = 5–12 mice/group). (J) Schematic representation of experiments with Irf3−/− mice. (K–M) Weight change (K), hemorrhages in BALF (L), and leukocyte counts (M) in wild-type and Irf3−/− mice treated as indicated. Each dot is an individual mouse. Shown are pooled results from two independent experiments (n = 3–7 mice/group) or a representative of two independent experiments (M, n = 3–5 mice/group). Bars and line graphs represent mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (H, I, and M), one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (A and B) or Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (G and L) and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (C, D, F, and K). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

IFN-I signature in the lung of mice with autoimmune AAPV. (A) Relative gene expression in the lungs of C57BL/6J at the indicated time points after AAPV induction. (B) Relative gene expression in the lungs of the indicated mice 3 d after treatment as indicated. Each dot is a single mouse (n = 5–8 mice/group). Bars represent mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (A) or two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (B) *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

IFN-I signature in the lung of mice with autoimmune AAPV. (A) Relative gene expression in the lungs of C57BL/6J at the indicated time points after AAPV induction. (B) Relative gene expression in the lungs of the indicated mice 3 d after treatment as indicated. Each dot is a single mouse (n = 5–8 mice/group). Bars represent mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (A) or two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (B) *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Antibody-mediated blockage of IFN receptor 1 (IFNAR-1; Fig. 4 E) diminished AAPV progression as demonstrated by reduced weight loss (Fig. 4 F), lower blood content in the BAL (Fig. 4 G), and leukocyte infiltration (Fig. 4 H), as well as decreased lung pathology (Fig. 4 I) compared to isotype-treated mice at the peak of disease progression (day 3), indicating a crucial role for the STING/IFN-I axis on progression toward severe AAPV. To obtain further independent evidence for the role of STING/IFN-I axis, we employed mice lacking the transcription factor IRF3 (Fig. 4 J), which is required to transduce STING signaling into IFN-I production (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008). As in wild-type mice treated with blocking α-IFNAR-1 antibodies, Irf3−/− mice showed less weight loss (Fig. 4 K), pulmonary hemorrhages (Fig. 4 L), and leukocyte infiltration (Fig. 4 M) upon challenge with bacterial ligands and anti-MPO IgG.

Thus, we conclude that STING activation promotes an IRF3-dependent IFN-I signature that is required for the development of severe AAPV.

Functional dichotomy between resident and inflammatory macrophages in ANCA vasculitis progression

Having identified STING/IFN-I as a major driver for severe AAPV, we next investigated the cellular source of IFN-β by using reporter mice in which transcriptional activation of Ifnβ results in luciferase production (Fig. 5 A). Consistent with our findings identifying an IFN-I signature in patients and mice (Fig. 1, B and C; and Fig. 4, A and B), administration of bacterial ligands and anti-MPO IgG induced luciferase expression in the lung, further demonstrating Ifnβ transcription during AAPV (Fig. 5 B). Bioluminescent ex vivo analysis of sorted cells indicated that most IFN-β was derived from inflammatory macrophages, whereas lung-resident AMs, lymphoid cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells produced little or no detectable IFN-β (Fig. 5 C).

Infiltrating macrophages produce IFN-I and enhance severity of AAPV. (A) Schematic representation to measure Ifnβ promoter activity in reporter mice by in vivo and ex vivo bioluminescence imaging. (B) Representative photographs of Ifnβ-Luc reporter mice treated as indicated, and bioluminescence quantification of the region of interest (ROI, red gate). Quantification is pooled of two independent experiments (n = 2–3 mice/group). (C) Ex vivo bioluminescence quantification of FACS-sorted cell populations (gates in Fig. S2 and Fig. S4 A). Each dot represents cells from an individual mouse. Shown are data pooled from three independent experiments for alv. Møs, infl. Møs, EnC, neutrophils, and one experiment for the rest. Alv, alveolar; infl, infiltrating; Møs, macrophages; EpCs, epithelial cells; EnCs, endothelial cells. (D) Schematic representation of AAPV induction in mice. (E) Flow cytometric plot showing percentages of alv. and infl. Møs gated as in Fig. S2, and respective quantification. Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 15–22 mice/group). (F and G) Weight change (F) and hemorrhages in BALF (G) in indicated mice undergoing AAPV. Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 15–22 mice/group). (H) Schematics of treatment with liposomes before onset of AAPV. Lipo, liposomes. (I) Quantification of alv. Møs on the day of AAPV induction. Each dot represents an individual mouse from a representative of two independent experiments with n = 3 mice/group. (J) Quantification of hemorrhages in BALF at the peak of AAPV severity (day 3). Each dot represents an individual mouse from two pooled independent experiments with n = 14 mice/group. Bar and line graphs show mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (E, G, and I), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (J) and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (C and F) *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Infiltrating macrophages produce IFN-I and enhance severity of AAPV. (A) Schematic representation to measure Ifnβ promoter activity in reporter mice by in vivo and ex vivo bioluminescence imaging. (B) Representative photographs of Ifnβ-Luc reporter mice treated as indicated, and bioluminescence quantification of the region of interest (ROI, red gate). Quantification is pooled of two independent experiments (n = 2–3 mice/group). (C) Ex vivo bioluminescence quantification of FACS-sorted cell populations (gates in Fig. S2 and Fig. S4 A). Each dot represents cells from an individual mouse. Shown are data pooled from three independent experiments for alv. Møs, infl. Møs, EnC, neutrophils, and one experiment for the rest. Alv, alveolar; infl, infiltrating; Møs, macrophages; EpCs, epithelial cells; EnCs, endothelial cells. (D) Schematic representation of AAPV induction in mice. (E) Flow cytometric plot showing percentages of alv. and infl. Møs gated as in Fig. S2, and respective quantification. Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 15–22 mice/group). (F and G) Weight change (F) and hemorrhages in BALF (G) in indicated mice undergoing AAPV. Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 15–22 mice/group). (H) Schematics of treatment with liposomes before onset of AAPV. Lipo, liposomes. (I) Quantification of alv. Møs on the day of AAPV induction. Each dot represents an individual mouse from a representative of two independent experiments with n = 3 mice/group. (J) Quantification of hemorrhages in BALF at the peak of AAPV severity (day 3). Each dot represents an individual mouse from two pooled independent experiments with n = 14 mice/group. Bar and line graphs show mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (E, G, and I), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (J) and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (C and F) *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To elucidate the role of Ifnβ-producing inflammatory macrophages on AAPV progression, we administered bacterial ligands as well as anti-MPO IgG to mice lacking Ccr2 or not (Fig. 5 D). Inflammatory infiltrating macrophages were of monocytic origin as indicated by Ly-6C and F4/80 expression (Fig. S4 B) as well as dependency on Ccr2 expression (Fig. 5 E). Ccr2-dependent inflammatory macrophages promoted disease severity as indicated by less pronounced weight loss (Fig. 5 F) and pulmonary hemorrhages (Fig. 5 G) in Ccr2−/− mice compared to their Ccr2-competent counterparts.

Characteristics of tissue-resident alveolar macrophages and infiltrating inflammatory macrophages in the lung of mice with autoimmune vasculitis. (A and B) Flow cytometric gating strategy, F4/80 and Ly-6C expression of the indicated macrophage and myeloid cell populations. (C) Iron staining or FACS-sorted alveolar macrophages (alv. Møs), infiltrating macrophages (infl. Møs), and neutrophils as in A. Arrowheads mark examples of alv. Møs with iron staining. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Characteristics of tissue-resident alveolar macrophages and infiltrating inflammatory macrophages in the lung of mice with autoimmune vasculitis. (A and B) Flow cytometric gating strategy, F4/80 and Ly-6C expression of the indicated macrophage and myeloid cell populations. (C) Iron staining or FACS-sorted alveolar macrophages (alv. Møs), infiltrating macrophages (infl. Møs), and neutrophils as in A. Arrowheads mark examples of alv. Møs with iron staining. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Lung-resident AMs also produced IFN-β, albeit to a much lower level than infiltrating macrophages (Fig. 5 C). To investigate the contribution of AMs, we used clodronate liposomes to deplete them 2 d before disease induction (Fig. 5 H). Clodronate liposomes significantly reduced AM numbers at the time of disease induction (Fig. 5 I) without affecting the extent of pulmonary hemorrhages (Fig. 5 J) at the peak of disease (day 3), suggesting they did not play a pathogenic role in the initial phase of disease progression.

However, when we analyzed BAL fluid (BALF) infiltrates by cytology, we found large mononuclear cells having internalized RBCs (Fig. 6 A). Interestingly, these hemophagocytes were absent in the BALF of AM-depleted mice (Fig. 6 A). Iron staining revealed that indeed AMs, but not inflammatory macrophages or neutrophils, took up extravascular RBCs (Fig. S4 C).

Alveolar macrophages promote homeostasis by clearing extravascular RBC. (A) Giemsa staining of BALF cytospins from mice treated with PBS or clodronate liposomes. White arrowheads indicate engulfed RBCs. (B–G) Quantification of alveolar macrophages (alv. Møs; B), hemorrhages in BALF (C and D), leukocytes (E), infiltrating Møs (F), and weight change (G) in BL6 mice during the recovery phase (5 d after AAPV induction) and treated with liposomes before disease induction as in Fig. 5 H. (H and I) Hemorrhages in BALF (H) and weight change (I) in Stinggt/gt mice undergoing AAPV and treated with liposomes as in B–G. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Shown are pooled data from three (B–G with n = 18–19 mice/group) and two (H and I with n = 7 mice/group) independent experiments. Bar and line graphs show mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (B–F and H), and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (G and I). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Alveolar macrophages promote homeostasis by clearing extravascular RBC. (A) Giemsa staining of BALF cytospins from mice treated with PBS or clodronate liposomes. White arrowheads indicate engulfed RBCs. (B–G) Quantification of alveolar macrophages (alv. Møs; B), hemorrhages in BALF (C and D), leukocytes (E), infiltrating Møs (F), and weight change (G) in BL6 mice during the recovery phase (5 d after AAPV induction) and treated with liposomes before disease induction as in Fig. 5 H. (H and I) Hemorrhages in BALF (H) and weight change (I) in Stinggt/gt mice undergoing AAPV and treated with liposomes as in B–G. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Shown are pooled data from three (B–G with n = 18–19 mice/group) and two (H and I with n = 7 mice/group) independent experiments. Bar and line graphs show mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (B–F and H), and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (G and I). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

We, therefore, hypothesized that AMs promoted lung homeostasis rather than disease progression by clearing extravascular RBCs arising from pulmonary hemorrhages and, thereby, reducing extracellular heme, a well-known proinflammatory mediator (Consonni et al., 2021; Weis et al., 2017). To investigate this, we analyzed disease recovery in AM-depleted mice (as in Fig. 5 H) 5 d after disease onset, when hemorrhages were being cleared (Fig. 2, E and F). AMs were still strongly depleted in clodronate-liposome–treated mice at that time point (Fig. 6 B). While control mice had cleared most of the pulmonary hemorrhages by day 5, AM-deficient mice showed significantly higher hemorrhages in BALF (Fig. 6, C and D). Consistent with extravascular heme being a proinflammatory stimulus, AM-depleted mice that were compromised in RBC clearance showed significantly higher leukocyte infiltration into the lung (Fig. 6 E), including inflammatory macrophages (Fig. 6 F) and increased weight loss (Fig. 6 G) during the recovery phase.

To further confirm that clearance of RBCs is necessary for reverting to homeostasis following AAPV induction, we depleted AMs in STING-deficient mice, which showed a faster recovery than wild-type counterparts (Fig. 3, H, I, K, and L). In line with our previous findings, AM depletion in Stinggt/gt mice also resulted in increased hemoglobin (Hb) levels and RBCs in BALF (Fig. 6 H). Interestingly, the protective effect of STING deficiency was abrogated by AM depletion (Fig. 6 I), indicating that extravascular RBC accumulation prevented recovery from disease even in the absence of functional STING.

Altogether, these data indicate a functional dichotomy of lung macrophage subpopulations in AAPV. While inflammatory macrophages infiltrate the lung in a Ccr2-dependent fashion and produce pathogenic IFN-β, lung-resident AMs counteracted disease progression by clearing extravascular RBCs and reducing the number of inflammatory macrophages.

Pharmacological inhibition of the STING/IFNAR pathway ameliorates autoimmune pulmonary vasculitis

Based on our results, we next explored the therapeutic efficacy of pharmacologically targeting STING or IFNAR-1 signal transduction with established small-molecule inhibitors. STING inactivation by the covalent small-molecule inhibitor H151 (Fig. 7 A) prevented vasculitis-associated weight loss (Fig. 7 B) and reduced the incidence of mice with pulmonary hemorrhages (Fig. 7 C). Furthermore, H151-treated mice showed lower hemorrhages (Fig. 7 D) and leukocyte infiltration (Fig. 7 E) in the BAL, although the lung injury score, which accounts for non-hemorrhagic lung alterations, was not significantly ameliorated (Fig. 7 F).

Pharmacological inhibition of STING or JAK/STAT pathways ameliorates AAPV in mice. (A) Schematic representation of experiment with H151 STING inhibitor. (B–F) Weight change kinetics (B), hemorrhages in BALF (C and D), leukocyte infiltration (E), and lung injury score (F) in mice treated as in A. (G) Schematic representation of experiment with JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. (H–J) Weight change (H), lung injury score (I), and hemorrhages in the BALF (J) of wild-type mice treated as in A. Each dot represents an individual mouse (D–F, I, and J). Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments with 5–12 mice/group (B–F), or 10–12 mice/group (H–J). Bar and line graphs show mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (E, I, and J), one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (D and F), and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (B and H). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.***, P < 0.001.

Pharmacological inhibition of STING or JAK/STAT pathways ameliorates AAPV in mice. (A) Schematic representation of experiment with H151 STING inhibitor. (B–F) Weight change kinetics (B), hemorrhages in BALF (C and D), leukocyte infiltration (E), and lung injury score (F) in mice treated as in A. (G) Schematic representation of experiment with JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. (H–J) Weight change (H), lung injury score (I), and hemorrhages in the BALF (J) of wild-type mice treated as in A. Each dot represents an individual mouse (D–F, I, and J). Shown are pooled data from two independent experiments with 5–12 mice/group (B–F), or 10–12 mice/group (H–J). Bar and line graphs show mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the significance level of unpaired t test (E, I, and J), one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (D and F), and two-way ANOVA with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (B and H). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.***, P < 0.001.

Since IFNAR-1 was required for the induction of severe pulmonary vasculitis, we hypothesized that the small-molecule inhibitor baricitinib, which targets JAK1 downstream of IFNAR-I and is used to treat interferonopathies in patients (Sanchez et al., 2018), may ameliorate AAPV (Fig. 7 G). Baricitinib treatment reduced weight loss (Fig. 7 H) and lung histopathology (Fig. 7 I) compared to vehicle treatment. Importantly, 10 of 11 (90.9%) vehicle-treated mice developed blood in the BAL, whereas baricitinib treatment resulted in 8 of 12 (66.6%) mice developing hemorrhages at day 3 after disease induction and to a lower degree (Fig. 7 J).

In conclusion, pharmacological inhibition of the STING and JAK1/2 pathways with well-characterized small-molecule inhibitors improved general well-being and lung hemorrhages in our mouse model for AAPV.

Discussion

AAV is a group of autoimmune diseases affecting small- and medium-sized blood vessels with a mortality rate of up to 80% within the first year of diagnosis if left untreated (Córdova-Sánchez et al., 2016). Current therapies rely on systemic steroid administration with severe side effects, accounting for about half of the mortality observed during the first year of treatment, mostly due to infections (Little et al., 2010). Thus, there is an urgent need to identify specific effector mechanisms that can be therapeutically targeted. Here, we report that patients with active autoimmune AAV showed increased cGAMP levels and IFN-I signature, suggesting pathogenic DNA recognition by the cGAS/STING axis, although a role for bacterial-derived cGAMP (Kranzusch 2019) cannot be ruled out. Using a novel mouse model for ANCA pulmonary autoimmune vasculitis, we demonstrate that the STING/IRF3/IFN-I axis is required for severe pulmonary bleeding, immune cell infiltration, and lung dysfunction, which are all hallmarks of the most life-threatening form of AAV in patients (Jennette and Falk, 1997). Pharmacological inhibition of STING, IFNAR-1, or JAK1/2 decreased disease severity and accelerated recovery. Thus, our results identify STING and IFN-I as important mediators of disease progression and open potential therapeutic venues by targeting those pathways.

The mouse model here presented offers several distinct advantages over currently available models. It is easily induced and based on defined mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against murine MPO rather than ill-defined polyclonal antibodies or protein-based immunization, which may cause highly variable antibody titers within the experiment groups (Shochet et al. 2020). In addition, this experimental model is unique in inducing pulmonary disease, often occurring in life-threatening AAV. Progression of pulmonary vasculitis depends on the combined application of anti-MPO monoclonal antibodies together with low doses of the bacterial ligands fMLP and LPS to model bacterial infections often observed preceding AAV flares (Timmeren et al. 2014). Low doses of fMLP and LPS synergized to enhance neutrophil recruitment and activation resulting in severe AAPV upon anti-MPO administration, consistent with the role of these cells during disease progression (Xiao et al., 2005).

STING activation results in pathogenic IFN-I levels in a TREX-1 deficiency heart injury model (Haag et al., 2018) and a murine model for COVID-19 (Domizio et al., 2022). We demonstrate that a covalent small-molecule inhibitor of human and mouse STING can reduce disease severity and pulmonary hemorrhages in the ANCA vasculitis mouse model. STING is activated following cGAS-mediated DNA recognition in the cytosol (Ablasser et al., 2013a; Diner et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2013). We provide evidence in mice and humans that DNA recognition by cGAS/STING/IFN-I axis promotes AAV progression. Albeit detected at low levels, cGAMP concentration was increased in the BAL of diseased mice and PBMCs of patients with active AAV. Low cGAMP concentrations may be the consequence of its ability to spread intercellularly, thereby amplifying the reach of the inflammatory response (Ablasser et al., 2013b; Zhou et al., 2020). Nevertheless, these low levels were sufficient to promote STING activation and disease progression.

The mechanisms driving cGAS/STING activation in our AAPV model may be multiple and remain to be further investigated. “Misplaced” cytosolic self-DNA in stressed cells is known to efficiently activate cGAS resulting in IFN-I release (West et al., 2015; Giordano et al., 2022), which may contribute to cGAS activation during AAPV progression. On the other hand, extracellular DNA is known to reach the cytosol and activate cGAS/STING in vivo under some conditions (Gehrke et al., 2013). During AAV in patients, neutrophils release DNA at sites of inflammation (Kessenbrock et al., 2009), and it has recently been shown that macrophages are able to internalize neutrophil-derived extracellular DNA to activate cGAS/STING and release IFN-I (Apel et al., 2021). These reports open the possibility for a role of extracellular DNA in our model because we detected cell-free DNA in the lungs with the capacity to activate cGAS in vitro, and macrophages were the primary source for IFN-I during AAPV progression in mice. Delivery of extracellular DNA into the cytosol has also been recently proposed in a non-autoimmune model of STING-induced aortic aneurism and dissection (Luo et al., 2020). However, whether extracellular DNA is required to activate STING in AAPV, as well as the mechanisms driving its translocation into the cytosol remain to be elucidated.

High-dose LPS alone has recently been shown to induce rapid mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) release resulting in cGAS/STING-mediated endothelial cell damage in mouse lungs (Huang et al., 2020). However, these findings cannot explain the vasculitis progression reported in our study using low-dose LPS because disease depend on anti-MPO administration. fMLP/LPS was sufficient to mediate the release of cGAS-stimulating DNA. However, pulmonary hemorrhages depended on anti-MPO administration, which is consistent with increased circulating levels of DNA/MPO complexes in patients with active AAV (Söderberg et al., 2015). Therefore, we hypothesize that immune complexes formed between MPO-decorated DNA released by activated neutrophils and anti-MPO IgG promote the internalization of immunogenic DNA. In support of this, Fc receptors contribute to the cytosolic translocation of DNA/α-double stranded DNA (dsDNA) immune complexes (Shin et al., 2013).

It has recently been shown that cGAS/STING activation may propagate to bystander cells (Decout et al., 2021). Following cGAS activation, cGAMP is released and can be taken up by bystander cells via gap junctions to activate STING beyond the actual site of cGAS activation (Ablasser et al., 2013b; Wang et al., 2020). Interestingly, we could quantify increased cGAMP levels in PBMCs of patients and mice undergoing vasculitis, suggesting that it may act in cis and in trans by inducing STING-dependent IFN-I production in the cell where cGAMP was initially activated as well as in bystander cells.

STING signals via the TBK1/IRF3 or the canonical NF-κB pathways to induce expression of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IFN-I and TNF-α, respectively (Motwani et al. 2019). IFN-I is at the center stage of congenic (Kretschmer and Lee-Kirsch, 2017), but also spontaneous autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (Banchereau and Pascual, 2006). We have shown in two independent approaches that the TBK1/IRF3/IFN-I pathway promotes AAPV development. In Irf3−/− mice and in wild-type mice treated with blocking antibodies directed against IFNAR-1, the development of vasculitis in the lung was significantly attenuated. This was in clear contrast with a mouse model for STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy caused by a self-activating mutation in STING, where IRF3- or IFNAR1-deficiency did not protect from disease development (Luksch et al., 2019; Warner et al., 2017), suggesting that different pathophysiological mechanisms drive acquired AAPV and congenic STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy in the lung.

Our results show that both in patients and mice, ANCA vasculitis is associated with an IFN-I signature. The role of IFN-I in the pathogenesis of ANCA vasculitis has been, however, controversial. ISG or IFN-I have been shown to be increased in patients with active vasculitis (Kessenbrock et al., 2009). However, a recent study did not find increased IFN-I or ISG expression in ANCA vasculitis patients (Batten et al., 2021). The reasons for this apparent disagreement are unresolved, although differences in disease severity across the different patient cohorts cannot be excluded. Our results not only show an IFN-I signature in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis but demonstrate that the STING/IRF3/IFN-I is pathogenic and blocking it at different levels ameliorates disease.

Inflammation is characterized by dynamic changes in the composition of organ-resident macrophages and infiltrating macrophages (Hou et al., 2021; Bain and MacDonald, 2022). Although the ontogeny of such populations is well-characterized (Geissmann et al., 2010; Guilliams et al., 2014; Hume et al. 2019; Bain et al., 2012), whether they differentially contribute to inflammation remains unresolved. In the lung, it has been postulated that resident AMs are anti-inflammatory mostly due to production of immunosuppressive mediators such as TGFβ (Garbi and Lambrecht, 2017), whereas infiltrating macrophages promote inflammation by release of cytokines such as TNF-α (Lin et al., 2008, 2) or TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (Herold et al., 2008). Here, we demonstrate a clear functional dichotomy in lung macrophage subsets. Most IFN-β was produced by infiltrating macrophages and these cells promoted pulmonary hemorrhages during ANCA-mediated vasculitis, consistent with a pro-inflammatory function. On the other hand, tissue-resident alveolar macrophages did not modify AAPV progression in the early phases of disease induction, but accelerated recovery by clearing extracellular RBCs and dampened inflammation, likely by reducing extracellular heme accumulation (Consonni et al., 2021). Of note, although extravascular RBC accumulated in large numbers in the lung of mice undergoing AAPV, we did not detect RBC intake by other phagocytes such as neutrophils, monocytes, and monocyte-derived infiltrating macrophages.

We are aware of some limitations in our study. We have focused on the clinically relevant effector phase of vasculitis and did not address the mechanisms leading to the formation of MPO-specific autoantibodies. Unveiling whether this depends also on STING activation was not within the scope of the present study. Future studies using other vasculitis models may clarify whether STING signaling also feeds back on the generation of pathogenic anti-MPO antibodies.

In summary, we established and used a novel mouse model for anti-MPO-associated vasculitis to show that genetic or pharmacological interference with the cGAS/STING/IFN-I axis significantly reduced disease severity. The elevated cGAMP and IFN-I signature observed in patients with active vasculitis suggest that targeting those pathways may be of therapeutic value.

Materials and methods

Clinical study design

Cohort I: AAV patients were recruited from a single rheumatology tertiary center. Clinical details are described in Table S1. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Bonn (210/19).

Cohort II: Patients were recruited from a specialist tertiary center during active disease with ANCA vasculitis. Enrolled patients were required to be on <10 mg prednisolone and on no other concurrent immunosuppression for a minimum of 3 mo before enrollment. Active disease was assessed in patients with ANCA vasculitis using the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score. Before treatment escalation, 100 ml blood samples were collected. Healthy controls were age- and sex-matched where possible. Ethical approval was obtained from the Cambridgeshire Regional Ethics Committee (REC08/H0306/21). All patients provided written informed consent. Patient details are described in Table S2.

Mice

C57BL/6J (#000664; The Jackson Laboratory strain), C57BL/6J-Sting1gt/J (#017537; The Jackson Laboratory strain, referred here as STING goldenticket or Stinggt/gt; Sauer et al., 2011), B6(C)-Cgastm1d(EUCOMM)Hmgu/J (#026554; The Jackson laboratory strain, referred here as cGAS−/−; Schoggins et al., 2014), Irf3−/− (Satoh et al., 2017), B6.129S4-Ccr2tm1/fc/J (#004999; The Jackson Laboratory strain, referred here as Ccr2−/−) and IFN-β-Luc reporter mice (Lienenklaus et al., 2009) were backcrossed to C57BL/6J background for at least 10 generations and maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions at the animal facilities of the University Hospital Bonn. Female mice were used at 8–12 wk of age. Mice were not randomized in cages, but each cage was randomly assigned to a treatment group. C57BL/6J were bred in the same facility and used as control mice. Stinggt/gt mice and C57BL/6J mice were co-housed at weaning for at least 6 wk before vasculitis induction. All animal experiments were approved by the corresponding government authority (Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz).

Generation of anti-MPO monoclonal antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibodies 6D1 (IgG2b) and 6G4 (IgG2c) directed against murine MPO were generated in exactly the same way as described for anti-MPO antibody clone 8F4 (van Leeuwen et al., 2008). Bulk production of 6D1 and 6G4 was performed by BioXcell.

Pulmonary vasculitis model

Pulmonary vasculitis was induced by intratracheal (i.t.) application of 50 μl PBS containing 10 µg LPS (Serotype 026:B6; Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 µg fMLP (Sigma-Aldrich) with the help of a small-animal laryngoscope and mechanical ventilation (Harvard Apparatus) for 1 min at 250 μl air/stroke and 250 strokes/min as previously described (Holland et al., 2018), followed by i.p. injection of 1 mg anti-MPO (clones 6D1 and 6G4, 0.5 mg of each clone) in 200 μl PBS. Control groups were either left untreated (naive) or received either anti-MPO (i.p.) alone or fMLP + LPS + isotype control (clones MPOC-137, MPC-11) in PBS (i.t.). Unless stated otherwise, analysis was performed on day 3 or 7 after induction. Weight loss was monitored daily.

Pharmacological inhibition of IFNAR-1, STING, and JAK/STAT signaling

IFNAR-1 was blocked as previously described by injecting mice with 250 µg α-IFNAR-1 (clone MAR1-5A3) antibody i.p. one day before vasculitis induction and then every second day. Control mice were treated equally but with irrelevant isotype control (clone MOPC-21).

STING activation was inhibited as previously described (Haag et al., 2018) by injecting mice i.p. daily with 750 nM H151 (inh-h151; InvivoGen) starting on the day of AAPV induction. Control mice received the vehicle only.

JAK/STAT pathway was inhibited as previously described (Carfagna et al., 2018) by oral gavage of 10 mg/kg body weight Baricitnib (Olumiant, Lilly). Control mice received an equal amount of only vehicles by oral gavage.

Depletion of alveolar macrophages in vivo

To deplete alveolar macrophages, 50 μl of Clodronate- or PBS-loaded liposomes (Control) were applied intratracheally 2 d before vasculitis induction under 2% isoflurane anesthesia.

Pulse oximetry

Blood SpO2 (%) was measured with the MouseOx Pulse-oximeter (Starr Life Science). Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in air, and the oximeter sensor was placed on the upper part of the shaved hind leg. Once stabilized over a maximum of 3 min, SpO2 (%) was measured each second over 3–5 min and values were averaged. Data shown are the mean of three individual averaged measurements per animal.

In vivo bioluminescence quantification

To quantify luminescence of IFN-β-Luc reporter mice, we injected 4.5 mg of Luciferin per mouse i.p. Mice were then anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in the IVIS (Lumina LT Series III) machine 5 min later at 37°C. Luminescence was sequentially acquired ranging from 5 min to 1 s of exposure time and a time point equal to all mice on the linear dynamic range was selected for quantification.

Blood cell collection, BALF collection, and lung fixation

Mice were killed by an overdose of Rompun/Ketamine. Mouse blood was collected from the lower aorta into heparinized capillaries. RBCs were lysed by incubating for 7 min at room temperature in PBS containing 10 mM NH4Cl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.01 M NaHCO3 (pH 7.3). Cells were centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the cell pellet was resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS with 3% heat-inactivated FCS).

BALF was obtained by intubating mouse tracheas through a small incision using a 20-gauge catheter. The bronchoalveolar space was washed by three sequential washes with 1 ml PBS containing 2 mM EDTA each. Cell-free BALF was obtained by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C.

Mouse lungs were inflated by slowly instilling 1 ml 4% methanol-free PFA (Thermo Fischer Scientific) in PBS through the trachea. Whole lungs were dissected out in the inspiration phase and stored in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C in PBS before paraffin-embedding.

To isolate human PMBCs from Cohort I (healthy volunteers and AAV patients, used for cGAMP quantification), peripheral blood was collected into EDTA tubes (Sarstedt). PBMCs were isolated by Biocoll Separating Solution (Merck Millipore). Cells were washed twice in saline and counted. Cell pellets were immediately frozen at −80°C.

To isolate human PBMCs from Cohort II (healthy volunteers and AAV patients, used for gene set enrichment analysis [GSEA]), peripheral blood was collected into 4% sodium citrate. Within 15 min of collection, blood was diluted 1:2 with magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) rinsing buffer (2 mM EDTA; PBS) and centrifuged on Histopaque 1077 at 900 g for 20 min at room temperature. Following centrifugation, PBMCs at the interface were removed, washed twice with MACS rinsing buffer, and then resuspended in 50 ml MACS running buffer (2 mM EDTA, 0.5% BSA; PBS).

Quantification of pulmonary hemorrhages

Hb in the BALF was quantified by spectrophotometry. 75 μl BALF was serially diluted in a 96-well plate, and its OD was measured at 400 nm (Robles et al., 2010) in a microplate reader with background subtraction at 670 nm. Values in the linear range below saturation (OD400-670 = 1.5) were selected and corrected for the dilution factor. Values were expressed as “corrected OD (Hb)”. Hb OD directly correlated to Hb concentration quantified by a colorimetric assay (Hemoglobin Assay Kit; Sigma-Aldrich; r2 = 0.9659, P = <0.0001).

Neutrophil stimulation in vitro

Neutrophils were isolated from C57BL/6J bone marrow (femur and tibia) by Histopaque-based density gradient centrifugation as previously described (Swamydas et al., 2015). 2 × 105 neutrophils in RPMI were seeded on poly-L-lysine-coated 12-mm glass coverslips. Neutrophils were incubated with 1 μM fMLP in RPMI or RPMI alone for 3 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. For the last 30 min, anti-MPO antibody (clones 6D1 and 6G4) was added at a final concentration of 5 µg/ml each. Cells were then carefully washed twice with warm RPMI and fixed in PBS containing 4% PFA for 30 min. Neutrophils were washed twice with PBS and stained with AlexaFluor 647–labeled goat anti-mouse IgG and DAPI in a blocking solution (0.1 M Tris solution, pH 7.4, with 1% BSA, 1% gelatin from cold water fish skin, and 0.3% Triton-X100). Coverslips were mounted on glass slides and images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope and analyzed using FIJI-ImageJ software v. 2.0.0.

Flow cytometry

1–2 × 106 cells were centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Cells were then resuspended in 100 μl PBS containing 3% FCS, 0.1% NaN3, 5% Octagam (human poly Ig), and fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies directed against different cell surface antigens for 20 min on ice in the dark. Antibodies are listed in Table S4. Cells were washed and acquired in a LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Sample acquisition was stopped in all different samples when an equal number of CaliBRITE beads (BD Biosciences) had been acquired. Dead cells and doublets were excluded with Hoechst33258 and standard procedures, respectively. Viable cells were then analyzed with FlowJo software v. 10.6.1.

Dimensionality reduction of flow cytometric data was performed using the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP) plug-in in FlowJo v. 10.6.1 and standard settings. Before UMAP, technical outliers were excluded using the FlowAI plug-in in FlowJo. Doublets and dead cells were excluded before UMAP. Specific cell populations were identified by standard gating as described in Fig. S2.

ROS were quantified by flow cytometry. After staining for surface markers, cells were resuspended in 50 μl 0.5 mM dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123) in PBS for 30 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells incubated with 1 μg/ml of PMA for 30 min at 37°C were used as positive controls. Samples not treated with DHR123 were used as negative controls.

Giemsa and iron staining

Standard cytospins of BALF or FACS-sorted cells were stained with Giemsa to visualize cell morphology and RBC uptake. Slides were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min at room temperature. Methanol was removed by washing slides in double distilled water (ddH2O). Afterward, slides were stained with 20% Giemsa in ddH2O for 20 min at room temperature. Slides were washed in ddH2O and mounted with ROTI Histokitt (ROTH). Images were taken using a standard light microscope.

Prussian blue stain (Iron Stain Kit; Abcam) was used to visualize iron in BALF cytospins according to manufacturer’s description. Slides were counterstained in nuclear fast red for 5 min, washed in distilled water, and mounted. Images were taken using a standard light microscope.

cGAMP measurement in human PBMCs

cGAMP in human PBMCs was quantified with the 2′,3′-Cyclic GAMP ELISA Kit (Arbor assays) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 5 × 106 thawed PBMCs were centrifuged and lysed in 50 μl sample diluent provided with the kit and assayed on a 96-well plate. For quantification of cGAMP in mouse samples, cell-free BALF supernatant from the first wash was centrifuged again at 6,797 g for 15 min at 8°C. cGAMP was measured in undiluted BALF using the 2′,3′-Cyclic GAMP ELISA Kit (Cayman Chemical) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sample concentrations were calculated with GraphPad Prism 8 using 4PL regression to interpolate the standard curve.

Histopathological analysis and lung injury score

Histopathological quantification was performed by a qualified pathologist (P. Boor) in a blinded manner on 1-µm thick microtome sections of paraffin-embedded whole-lungs stained with H&E and scanned at a 40× magnification using a bright-field scanner (Aperio AT2; Leica). Morphological changes and immune cell infiltration in the lungs were graded as previously described (Li et al., 2014). In brief, the lung injury score was composed of three parameters: immune cell infiltration, tissue destruction, and the number of lobes affected. Scores were: 0 (no inflammation), normal lung structure; 1 (slight), very few and only focal inflammatory cells, no or minimal tissue destruction; 2 (medium), larger areas also with tissue destruction; 3 (strong), large areas with inflammatory infiltrates and tissue destruction, up to one lobe involved; 4 (extensive), as 3 but involving more than one whole lobe.

Confocal microscopy of the lung

To investigate endothelial cell death, we injected 5 μg AF647-conjugated anti-CD31 antibody i.v. 5 min before humane killing of mice. Lungs were inflated with 2% low-melting agarose solution at 37°C. Lungs were dissected out, cooled for 10 min at 4°C, and finally embedded in 4% agarose. Lung sections of 150 µm thickness were cut using a vibrating-blade microtome. Sections were mounted in PBS containing 1 µg/ml propidium iodide at 4°C and immediately analyzed on a LSM 710 Zeiss confocal microscope using a 20× Pan-APOCHROMAT objective with numerical aperture of 0.8. Five z-stacks covering 15 µm were taken per image. The first photograph was taken at 25 µm from the surface to avoid analyzing cells damaged during the cutting process. Data were analyzed using FIJI-ImageJ software v. 2.0.0.

Optical clearing of the lung and light-sheet microscopy

3 h after AAPV induction, mice were injected i.v. with 50 µg Texas red–labeled albumin in 100 μl PBS. 1 h later, animals were killed in CO2/air (50/50 [vol/vol]) and exsanguinated by an incision in the right femoral artery. Mice were perfused in PBS through the left ventricle at a flow speed of 10 ml/min for 90 s. Lungs were subsequently explanted and fixed in 4% methanol-free PFA overnight at 4°C.

Optical clearing was achieved as previously described (Klingberg et al., 2017) by transfer of the samples into 99% ethanol for 3 h at room temperature. Samples were then transferred into ethyl cinnamate and incubated for a further 5 h. Image stacks of the cleared lungs were acquired with a step size of 20 µm using a custom build light-sheet-fluorescence-microscope (LaVision Biotec). Samples were excited with two light sheets at 561 nm and recorded using an emission filter at 620/60 nm to detect albumin depositions. Texas red–labeled albumin deposition was quantified in FIJI-Image J by physician-aided thresholding, resulting in the scale bar within the picture. Thresholds were set to equal values for all samples. Files were exported in nrrd format and imported into ParaView v5.7.0 for 3D reconstruction.

Extracellular DNA quantification in BALF

DNA in 100 μl of undiluted cell-free BALF (first wash) was quantified in DNase-free 96-well plates (TPP) using Quant-iT Pico Green dsDNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following manufacturers’ instructions.

Extracellular DNA purification and analysis

DNA in cell-free BALF was purified using standard phenol-chloroform-isoamyl procedures, precipitated in 3 M sodium acetate and isopropanol at −80°C for at least 1 h, and finally resuspended in DNase-free water. DNA concentration was measured using a spectrophotometer.

Recombinant 6xHis-tagged murine Trex1 was expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta DE3 and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography as previously described (Gehrke et al., 2013). For digestion experiments, 1 µg of purified DNA was incubated with 40 ng recombinant murine Trex1, 1 U DNase I, or without enzyme in 25 μl of digestion buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 60 mM KCl). Digestion was performed at 37°C for 30 min followed by enzyme inactivation at 75°C for 10 min. Half of the digested samples were run on a 1.5% agarose gel at 110 V for 1 h 30 min. The gel was stained with SYBR Gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged on a ChemiDoc XRS+ (Bio-Rad). Trex1-resistant (but DNase I sensitive) modified 60bp DNA was used as controls as previously described (Gehrke et al., 2013).

The ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear extracellular DNA purified from cell-free BALF was determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) as previously described (Quiros et al., 2017). qRT-PCR was performed on the purified DNA with the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a QuantStudio 6 Flex System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primer sequences for the mitochondrial genes Nd1 and 16s and the nuclear gene Hk2 are listed in Table S3. Relative gene abundance was calculated by the ΔΔCt method.

Analysis of IFN-I signature in mice

Analysis of ISGs was performed as previously described (Luksch et al., 2019). Total RNA from mouse lungs was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were determined spectrophotometrically. 2 µg RNA was reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, Rnasin, and dNTPs (all Promega) in 35 μl reaction according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed using Quantstudio 5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and GoTagqPCR Master Mix with SYBR green fluorescence (Promega). PCR primer sequences were retrieved from online Primer Bank database (Spandidos et al., 2010). Expression of genes was normalized with respect to each housekeeping gene using the ΔΔCt method for comparing relative expression (upregulation > 2.0 and downregulation < 0.5).

GSEA

GSEA was performed as previously described (Lyons et al., 2010). Briefly, RNA was extracted from 5 × 106 human PBMCs from Cohort II using AllPrep RNEasy kits (Qiagen) and the small RNA-containing column flow-through was collected. For microarray analyses, 200 ng aliquots of total RNA were labeled and hybridized to Affymetrix Gene ST 1.1 expression arrays according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Microarray data was stored as CEL files and read into R. Raw data was pre-processed using the BioConductor suite of packages. The oligo package was used to normalize the data and create an expression set. Raw values were log-transformed and normalized using robust multiarray averaging. The arrayQualityMetrics package was used to assess outliers. Probes with no annotation (Entrez gene ID) were removed. Where multiple probes mapped to a common gene, the probe with the largest variance was analyzed. ComBat (SVA package) was used to correct for batch effects. GSEA was performed to assess for enrichment in the interferon pathway. The package ComplexHeatmap was used to generate the heatmap of leading-edge genes using Z normalized data. Data has been deposited at ArrayExpress under E-MTAB-12008.

cGAS activation assay

Radiolabeled cGAS activity assays were performed as previously described (Civril et al., 2013). Briefly, 80 ng of DNA was mixed with 25 µM ATP, 25 µM GTP, and trace amounts of [⍺32P] ATP (Hartman Analytic) in reaction buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol). Reactions were started by addition of 1 µM mouse cGAS and incubated for 45 min at 37°C. Reaction products were spotted on thin layer chromatography (PEI-Cellulose F plates; Merck) and 1 M (NH4)2SO4/1.5 M KH2PO4 pH 3.8 was used as running buffer. Thin layer chromatography plates were analyzed by phosphor imaging (Typhoon FLA 9000; GE Healthcare). Genomic DNA (gDNA) and 60bp synthetic DNA (dsDNS) were used as controls.

Ex vivo bioluminescence imaging and quantification