Toll-like receptors (TLRs) engage networks of transcriptional regulators to induce genes essential for antimicrobial immunity. We report that NFAT5, previously characterized as an osmostress responsive factor, regulates the expression of multiple TLR-induced genes in macrophages independently of osmotic stress. NFAT5 was essential for the induction of the key antimicrobial gene Nos2 (inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS]) in response to low and high doses of TLR agonists but is required for Tnf and Il6 mainly under mild stimulatory conditions, indicating that NFAT5 could regulate specific gene patterns depending on pathogen burden intensity. NFAT5 exhibited two modes of association with target genes, as it was constitutively bound to Tnf and other genes regardless of TLR stimulation, whereas its recruitment to Nos2 or Il6 required TLR activation. Further analysis revealed that TLR-induced recruitment of NFAT5 to Nos2 was dependent on inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK) β activity and de novo protein synthesis, and was sensitive to histone deacetylases. In vivo, NFAT5 was necessary for effective immunity against Leishmania major, a parasite whose clearance requires TLRs and iNOS expression in macrophages. These findings identify NFAT5 as a novel regulator of mammalian anti-pathogen responses.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) belong to a large group of sensors specialized in recognizing specific molecular patterns of pathogens and are expressed by sentinel cells of the immune system such as dendritic cells and macrophages (West et al., 2006; Kawai and Akira, 2010). Upon recognition of specific ligands, TLRs initiate intracellular signaling cascades that induce a broad gene expression program that regulates the defense against pathogens and stimulates adaptive immune responses (Jenner and Young, 2005; West et al., 2006; O’Neill and Bowie, 2007). The different TLRs ensure an effective response against a wide variety of microbial pathogens by inducing a common set of gene products with general antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties (Jenner and Young, 2005). This is accomplished through the shared use of core signaling pathways in which mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (p38, JNK, and ERK1/2), the inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK) β–NF-κB axis, and IFN regulatory factor (IRF) transcription factors are prominent players (Dong et al., 2002; Honda and Taniguchi, 2006; West et al., 2006). In addition, TLRs need precise regulatory mechanisms to adjust the patterns of genes expressed and their magnitude of induction to variables such as the type of ligand, the transient or persistent nature of the stimulation, the dose of that stimulus, or the effect of tolerization (Foster et al., 2007; Litvak et al., 2009).

Specificity and fine tuning of gene expression downstream TLRs are achieved through various strategies. A central component in control of specificity is the mobilization of combinations of transcriptional regulators that are either constitutively functional or become expressed and/or activated upon TLR stimulation (Medzhitov and Horng, 2009). For instance, NF-κB factors respond to all TLRs, but they participate in different aspects of these responses by cooperating with other transcriptional regulators, such as IRF3 (Wietek et al., 2003) and E2F1 (Lim et al., 2007), or by controlling their expression, as described for C/EBPδ (Litvak et al., 2009) and JMJD3 (De Santa et al., 2007). Another component accounting for TLR-induced specific gene expression in response to pathogens is the dynamic remodeling of chromatin architecture, and the recruitment of diverse co-activator and co-repressor complexes with histone-modifying activity that occurs at the regulatory regions of certain genes (Weinmann et al., 1999; Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2006; Hargreaves et al., 2009; Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2009; Glass and Saijo, 2010). According to their transcriptional requirements, TLR-induced genes were recently classified in three main categories (Saccani et al., 2001; Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2006; Hargreaves et al., 2009; Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2009). Early primary response genes, such as Tnf, Ptgs2, and Nfkbia, usually contain CpG island promoters, are expressed rapidly and independently of SWI/SNF-induced nucleosome remodeling or de novo protein synthesis, and are constitutively assembled into a chromatin structure similar to that found in active genes. Late primary response genes, such as Ccl5 and Ccl2, are also induced independently of de novo protein expression but require chromatin remodeling. Finally, induction of secondary response genes, such as Nos2, Il12b, and Il6, depends on de novo protein synthesis and often requires SWI/SNF-dependent nucleosome remodeling.

Although these studies have revealed general mechanistic principles underlying gene expression downstream of TLRs, and substantial knowledge on the transcriptional network acting in TLR responses has been gathered in recent years, our current map of the identity and specific functions of the transcriptional regulators involved is still incomplete. Increased knowledge on immune defense mechanisms that control gene expression during the activation of TLRs is necessary to understand how host and parasite factors might predispose individuals to develop the disease or control the infection, and may also provide new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

The transcription factor NFAT5 belongs to the family of Rel-like domain-containing factors, which comprises the NF-κBs and the calcineurin-dependent NFATc proteins (López-Rodríguez et al., 1999b, 2001; Miyakawa et al., 1999; Aramburu et al., 2006). NFAT5 uses a dimerization mechanism conserved in NF-κB proteins (López-Rodríguez et al., 1999a, 2001; Stroud et al., 2002) and, although its function is not dependent on the calcium-activated phosphatase calcineurin, NFAT5 recognizes DNA elements whose sequence coincides with that of sites bound by NFATc proteins (Rao et al., 1997; López-Rodríguez et al., 1999b; Stroud et al., 2002). NF-κB and NFATc proteins are involved in innate immune responses activated upon recognition of specific pathogen-associated molecular patterns by different types of receptors. NF-κB proteins have a broad impact in the induction of gene expression in the response to pathogens because they are positioned downstream of TLRs, RIG-I–like receptors, and certain members of the NOD-like receptors and C-type lectin receptors families (Meylan et al., 2006; Kawai and Akira, 2007; Geijtenbeek and Gringhuis, 2009). In contrast, and also in the context of innate responses, NFATc proteins are not activated by TLRs but respond to the calcium mobilization-coupled receptors Dectin 1 and CD14 (Goodridge et al., 2007; Zanoni et al., 2009; Greenblatt et al., 2010). NFAT5 is a central regulator of gene expression in the adaptation to extracellular hypertonicity (Aramburu et al., 2006; Jeon et al., 2006), a function which is controlled by the p38 MAP kinase (Ko et al., 2002; Morancho et al., 2008). In contrast to NF-κB and NFATc proteins, an immunological role for NFAT5 has remained elusive beyond its osmoregulatory function in leukocytes (Go et al., 2004; Morancho et al., 2008; Drews-Elger et al., 2009; Kino et al., 2009; Machnik et al., 2009; Berga-Bolaños et al., 2010). However, NFAT5 can induce the expression of several proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and surface receptors in lymphocytes and macrophages exposed to hyperosmotic stress (López-Rodríguez et al., 2001; Kino et al., 2009; Machnik et al., 2009; Berga-Bolaños et al., 2010; Roth et al., 2010). The ability of NFAT5 to induce genes with immunomodulatory activity and not restricted to osmoadaptation led us to consider that, similarly to other Rel-like transcription factors, it might play a role in specific immune receptor-mediated responses.

We report that NFAT5 regulates TLR-induced gene expression in primary macrophages, and that this capacity is independent of its osmoregulatory function. NFAT5-regulated genes encode, among others, for cytokines and chemokines, extracellular matrix or protease-related proteins, regulators of nitric oxide production, proteins that control cell cycle progression and proliferation, and certain repressors of inflammation. NFAT5 was particularly required for the induction of genes, such as Tnf and Il6, by low doses of TLR ligands, but essential for the expression of Nos2 (inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS]) under both low and high doses of stimulus, suggesting that NFAT5 enables macrophages to modulate specific gene expression profiles in response to different stimulation thresholds. Whereas NFAT5 was expressed in unstimulated macrophages, it was further induced in an NF-κB–dependent manner upon TLR stimulation, indicating that although basal levels of NFAT5 could suffice to induce certain target genes, its long-term accumulation might contribute to sustain the prolonged expression of others. We found that NFAT5 exhibited two modes of association with target genes, as it was constitutively bound to Tnf and other genes regardless of TLR stimulation, whereas its recruitment to Nos2 or Il6 required TLR activation. Further analysis revealed that the recruitment of NFAT5 to Nos2 was dependent on IKKβ activity and de novo protein synthesis, and was sensitive to histone deacetylases (HDACs). These results indicated that NFAT5 is poised to react as a primary response factor for a subset of genes, but subordinated to secondary response mechanisms, possibly dependent on changes in chromatin accessibility, for the induction of others. The relevance of NFAT5 in the response to pathogens in vivo was revealed by the remarkable susceptibility of NFAT5-deficient mice to Leishmania major infection, a parasite whose clearance by the host requires different TLRs and iNOS expression in macrophages.

RESULTS

NFAT5 regulates gene expression in macrophages in response to TLRs

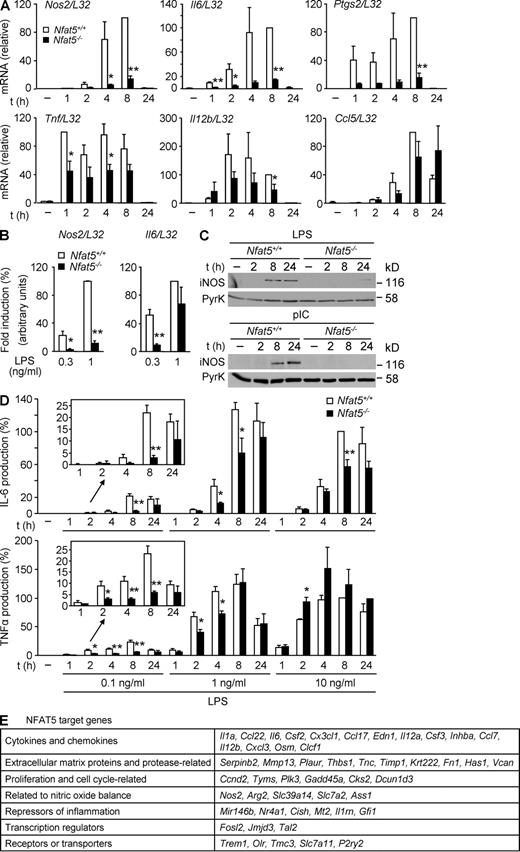

Rel-like transcription factors play essential roles in the innate defense against pathogens. Because NFAT5 is expressed in leukocytes and regulates the expression of diverse immunomodulatory proteins in response to osmotic stress, we asked whether it could participate in the transcriptional response induced by specific pathogen receptors. We began by analyzing whether lack of NFAT5 in macrophages affected the TLR-mediated induction of diverse primary and secondary response proinflammatory and antimicrobial genes: Nos2, Il6, Ptgs2, Tnf, Il12b, and Ccl5, which encode for iNOS, IL-6, COX2, TNF, IL-12β, and RANTES, respectively. Our results showed that mouse BM-derived macrophages (BMDMs) lacking NFAT5 (Fig. S1 A) were severely impaired in their expression of Nos2, Il6, and Ptgs2 mRNAs in response to LPS (Fig. 1 A). Induction of Tnf and Il12b was less affected, and the induction of Ccl5 mRNA was delayed (Fig. 1 A). Similarly, the expression of Nos2 and Il6 in response to polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly I:C) was substantially reduced in NFAT5-deficient macrophages (Fig. S1 B). Therefore, NFAT5 regulated the expression of genes with fast induction kinetics, such as Tnf, as well as genes with a slower and more gradual induction (Nos2 and Il6). In these experiments, we used low concentrations of TLR agonists to avoid the activation of TLR-independent pathways (Liu et al., 2001; Gitlin et al., 2006). In this regard, defects in Il6 expression observed in Nfat5−/− BMDMs were more evident at 0.3 ng/ml LPS than at 1 ng/ml of LPS, whereas Nos2 induction was substantially impaired in response to either dose (Fig. 1 B). Consistent with the mRNA data, TLR-activated production of iNOS, IL-6, and TNF proteins was decreased in Nfat5−/− macrophages, and defects in IL-6 and TNF induction were more pronounced at low doses of LPS (Fig. 1, C and D). Impaired iNOS expression was also observed when NFAT5-deficient BMDMs were stimulated with LPS plus IFN-γ (Fig. S1 C), which synergize to induce iNOS transcription (Xie et al., 1993).

Induction of TLR-responsive genes in NFAT5-deficient macrophages. (A) mRNA expression for the indicated genes was measured by RT-qPCR in samples from Nfat5+/+ and Nfat5−/− BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 0.1 ng/ml LPS for 1–24 h. Graphs show the relative induction after normalization to L32 mRNA and represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, with statistical significance (Student’s t test) indicated as *, P < 0.06; **, P < 0.01. (B) Induction of Nos2 and Il6 mRNA was analyzed as in A, in cells stimulated with 0.3 or 1 ng/ml LPS for 6 h. mRNA levels after normalization to L32 mRNA are shown relative to 1 ng/ml LPS–stimulated cells, which was given an arbitrary value of 100. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) Western blot for iNOS in Nfat5+/+ and Nfat5−/− BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 10 µg/ml poly I:C (pIC) or 10 ng/ml LPS for 2–24 h. Pyruvate kinase (PyrK) is shown as loading control. One representative experiment is shown out of three independently performed. (D) IL-6 (top) and TNF (bottom) were measured by ELISA in cell-free supernatants from Nfat5+/+ and Nfat5−/− BMDM cultures stimulated as indicated. Values are shown relative to the cytokine production in Nfat5+/+ BMDMs after 8 h of stimulation with 10 ng/ml LPS, represented as 100%. The mean ± SEM of three independent experiments is shown (*, P < 0.06; **, P < 0.01). (E) Seven groups of selected NFAT5 target genes identified by microarray analysis of WT and NFAT5-deficient macrophages treated with 0.3 ng/ml LPS for 6 h are shown (Table S1 contains a detailed list of genes). Selected genes were induced twofold or higher by LPS in WT cells, and their induction was reduced by 50% or more in NFAT5-deficient cells. Microarray data correspond to separately hybridized samples obtained from four independent cultures of untreated or LPS-stimulated Nfat5+/+ or Nfat5−/− BMDMs.

Induction of TLR-responsive genes in NFAT5-deficient macrophages. (A) mRNA expression for the indicated genes was measured by RT-qPCR in samples from Nfat5+/+ and Nfat5−/− BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 0.1 ng/ml LPS for 1–24 h. Graphs show the relative induction after normalization to L32 mRNA and represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, with statistical significance (Student’s t test) indicated as *, P < 0.06; **, P < 0.01. (B) Induction of Nos2 and Il6 mRNA was analyzed as in A, in cells stimulated with 0.3 or 1 ng/ml LPS for 6 h. mRNA levels after normalization to L32 mRNA are shown relative to 1 ng/ml LPS–stimulated cells, which was given an arbitrary value of 100. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) Western blot for iNOS in Nfat5+/+ and Nfat5−/− BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 10 µg/ml poly I:C (pIC) or 10 ng/ml LPS for 2–24 h. Pyruvate kinase (PyrK) is shown as loading control. One representative experiment is shown out of three independently performed. (D) IL-6 (top) and TNF (bottom) were measured by ELISA in cell-free supernatants from Nfat5+/+ and Nfat5−/− BMDM cultures stimulated as indicated. Values are shown relative to the cytokine production in Nfat5+/+ BMDMs after 8 h of stimulation with 10 ng/ml LPS, represented as 100%. The mean ± SEM of three independent experiments is shown (*, P < 0.06; **, P < 0.01). (E) Seven groups of selected NFAT5 target genes identified by microarray analysis of WT and NFAT5-deficient macrophages treated with 0.3 ng/ml LPS for 6 h are shown (Table S1 contains a detailed list of genes). Selected genes were induced twofold or higher by LPS in WT cells, and their induction was reduced by 50% or more in NFAT5-deficient cells. Microarray data correspond to separately hybridized samples obtained from four independent cultures of untreated or LPS-stimulated Nfat5+/+ or Nfat5−/− BMDMs.

The experiments mentioned in the previous paragraph indicated that NFAT5 was required for the expression of a group of TLR-induced genes. To get a broader view of NFAT5-regulated genes, we performed RNA microarray analysis of BMDMs stimulated with LPS during 6 h, which showed that from a total of 755 genes induced more than twofold by LPS, at least 83 were regulated by NFAT5 (Fig. 1 E; and Table S1). Of these, 24 were induced between 4-fold and >100-fold in WT macrophages, and their expression was reduced by >65% in NFAT5-deficient cells (Table S1). These genes encoded, among others, for diverse proteins such as cytokines and chemokines, extracellular matrix or protease-related proteins, regulators of nitric oxide production, regulators of cell cycle progression and proliferation, and certain repressors of inflammation (Fig. 1 E), which indicates that NFAT5 might be relevant in various aspects of the response to pathogens.

Analysis of Nfat5−/− BMDMs did not reveal defects in their maturation and capacity to activate main signaling pathways downstream of TLRs, including IRF3 dimerization, IκBα degradation, and phosphorylation of JNK, ERK, or p38 MAP kinases (Fig. S2, A–C), indicating that the specific gene expression defects observed in NFAT5-deficient BMDMs were not the result of a general impairment of TLR signaling. As NFAT5 can be activated by hypertonic stress in macrophages (Morancho et al., 2008; Machnik et al., 2009), we confirmed that culture media remained isotonic during their maturation from BM cells and after LPS stimulation, and that BMDMs expressed osmoresponsive genes only when exposed to hypertonicity and not in response to TLRs (Fig. S3, A–C and Table S1). Therefore, NFAT5 was required for the expression of multiple TLR-responsive genes in macrophages in a hypertonicity-independent manner.

Constitutive and TLR-induced association of NFAT5 with target genes

Several NFAT5-regulated genes, which included primary and secondary TLR-response genes (Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2009), contained clear consensus NFAT5 binding sites in their regulatory regions (5′-(T/C/A)GGAAA-3′; López-Rodríguez et al., 1999b; Fig. S4 A). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments showed that NFAT5 was recruited to the Nos2 promoter after stimulation of BMDMs with LPS or poly I:C (Fig. 2 A; and Fig. S4 B). Similarly, NFAT5 was recruited to the regulatory regions of other secondary response genes such as Il6 or Il12b in a TLR-dependent manner (Fig. 2 A; and Fig. S4 B). Binding of NFAT5 to Ptgs2, a gene with a biphasic primary and secondary response behavior (Caivano et al., 2001), also required TLR stimulation (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, NFAT5 was constitutively bound to the Tnf gene promoter regardless of TLR stimulation (Fig. 2 B and Fig. S4 B), possibly reflecting that Tnf is an early primary response gene that in resting conditions is already associated with certain transcription factors and chromatin remodeling complexes (Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2006; Hargreaves et al., 2009). This pattern of constitutive NFAT5 binding was also observed in other primary response target genes (Il1a, Traf1, and Ccl2; Fig. 2 B), but not in the primary response gene Ccl5, to which NFAT5 was recruited in a TLR-dependent manner (Fig. 2 B). Binding of NFAT5 to the proximal promoter of target genes such as Csf2, Mmp13, or Lcn2 was not detected, indicating that it might regulate other regions or contribute indirectly to their expression. As specificity controls for the ChIP assay, preimmune rabbit serum did not immunoprecipitate any of those regulatory regions in WT BMDMs, and neither did the NFAT5-specific antibodies in Nfat5−/− macrophages (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S4 B). In addition, NFAT5 did not associate with a control genomic region within exon 14 of the Nfat5 gene, devoid of NFAT5 binding sites (López-Rodríguez et al., 2001; Fig. 2 A; and Fig. S4 B). Altogether, our data indicated that NFAT5 exhibited two general patterns of association with its direct target genes in macrophages: it was constitutively bound to most primary response target genes in unstimulated macrophages, but its recruitment to secondary response genes required TLR activation.

Association of NFAT5 with regulatory regions of TLR-responsive genes. (A) Association of NFAT5 with the promoters of Nos2, Il6, and Ptgs2, and the enhancer region of Il12b. Formaldehyde–cross-linked chromatin from Nfat5+/+ or Nfat5−/− BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 2 h (or 1 h for Ptgs2) was immunoprecipitated with preimmune rabbit serum (pi) or a mixture of two rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for NFAT5 (N5). Immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to its respective total chromatin (input). Graphics represent the relative enrichment in chromatin immunoprecipitated by the NFAT5-specific antibodies compared with the input signal. A negative control showing the lack of binding of NFAT5 to exon 14 of the Nfat5 gene, which contains no NFAT5 binding sites, is shown. Values shown are the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (B) Binding of NFAT5 to the promoters of Tnf, Il1a, Traf1, Ccl2, and Ccl5 was analyzed as described in A.

Association of NFAT5 with regulatory regions of TLR-responsive genes. (A) Association of NFAT5 with the promoters of Nos2, Il6, and Ptgs2, and the enhancer region of Il12b. Formaldehyde–cross-linked chromatin from Nfat5+/+ or Nfat5−/− BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 2 h (or 1 h for Ptgs2) was immunoprecipitated with preimmune rabbit serum (pi) or a mixture of two rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for NFAT5 (N5). Immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to its respective total chromatin (input). Graphics represent the relative enrichment in chromatin immunoprecipitated by the NFAT5-specific antibodies compared with the input signal. A negative control showing the lack of binding of NFAT5 to exon 14 of the Nfat5 gene, which contains no NFAT5 binding sites, is shown. Values shown are the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (B) Binding of NFAT5 to the promoters of Tnf, Il1a, Traf1, Ccl2, and Ccl5 was analyzed as described in A.

NFAT5 regulates the TLR-induced activation of the Nos2 promoter

Given that iNOS induction by TLRs was severely impaired in NFAT5-deficient BMDMs, we analyzed the direct regulation of the Nos2 gene promoter by NFAT5 in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Two independent NFAT5-specific shRNAs (shN5-1 and shN5-2), whose effectiveness we had previously validated with an osmostress-responsive, NFAT5-dependent reporter (Fig. 3 A), inhibited the activation of the iNOS-Luc reporter by LPS (Fig. 3 B). Likewise, mutation of the NFAT5 binding site in iNOS-Luc abrogated its responsiveness to LPS (Fig. 3 C). Suppression of NFAT5 also impaired the activation of the iNOS reporter by agonists of different TLRs (Fig. 3 D) and prevented iNOS expression as well as nitric oxide production (Fig. 3, E and F). These findings, together with our previous ChIP results, showed that NFAT5 is a direct regulator of iNOS transcription, and further supported the interpretation that defective gene expression in NFAT5-deficient macrophages activated by TLRs was specifically a result of the lack of this factor.

NFAT5-dependent activation of the Nos2 promoter and iNOS induction. Activity of the hypertonicity-responsive ORE-Luc reporter (A) and the LPS-responsive mouse Nos2 promoter (iNOS-Luc; B) in RAW 264.7 cells cotransfected with a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vector specific for GFP or two independent NFAT5-specific shRNA vectors (N5-1 and N5-2), together with the control reporter plasmid TK-Renilla. Luciferase was measured 20 h after hypertonicity treatment (500 mOsm/kg) or LPS stimulation (25 µg/ml), normalized to TK-Renilla, and represented as percentage of reporter activity with respect to cells transfected with shGFP and stimulated (100%). Graphs show the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. Bottom panels show the Western blot for NFAT5 done in parallel to the reporter assays. Pyruvate kinase (PyrK) is shown as loading control. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Activity of WT mouse Nos2 promoter construct (WT) or an NFAT5-binding site mutant (NFAT5 mut) in RAW 264.7 cells after 20 h of LPS stimulation. Luciferase activity normalized to TK-Renilla is represented as fold induction relative to the reporter activity in unstimulated cells. Graphs show the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (D) Activation of the Nos2 promoter in response to different TLR agonists was measured in RAW 264.7 cells cotransfected with the iNOS-Luc and TK-Renilla reporters plus either shGFP or shN5-1 vectors. Transfected cells were stimulated for 20 h with 1 µg/ml Pam3CSK4 (P3C), 300 µg/ml zymosan A (Zym), 100 µg/ml poly I:C (pIC), 25 µg/ml LPS, 1 mM loxoribine (Lox), or 1 µM CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG). Luciferase activity normalized to TK-Renilla is represented as fold induction over the reporter activity in unstimulated cells (−). Graphics show the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (E) RAW 264.7 cells transfected with either shGFP or shN5-1 vectors were left untreated or stimulated with different TLR ligands as in D. Expression of NFAT5, iNOS, and pyruvate kinase (normalization control) was detected by Western blotting. The experiment shown is representative of three independently performed. (F) Nitric oxide production upon 24 h of stimulation with 100 µg/ml pIC or 25 µg/ml LPS in RAW 264.7 cells transfected with either shGFP or shN5-1 vectors. Graphics show the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

NFAT5-dependent activation of the Nos2 promoter and iNOS induction. Activity of the hypertonicity-responsive ORE-Luc reporter (A) and the LPS-responsive mouse Nos2 promoter (iNOS-Luc; B) in RAW 264.7 cells cotransfected with a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vector specific for GFP or two independent NFAT5-specific shRNA vectors (N5-1 and N5-2), together with the control reporter plasmid TK-Renilla. Luciferase was measured 20 h after hypertonicity treatment (500 mOsm/kg) or LPS stimulation (25 µg/ml), normalized to TK-Renilla, and represented as percentage of reporter activity with respect to cells transfected with shGFP and stimulated (100%). Graphs show the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. Bottom panels show the Western blot for NFAT5 done in parallel to the reporter assays. Pyruvate kinase (PyrK) is shown as loading control. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Activity of WT mouse Nos2 promoter construct (WT) or an NFAT5-binding site mutant (NFAT5 mut) in RAW 264.7 cells after 20 h of LPS stimulation. Luciferase activity normalized to TK-Renilla is represented as fold induction relative to the reporter activity in unstimulated cells. Graphs show the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (D) Activation of the Nos2 promoter in response to different TLR agonists was measured in RAW 264.7 cells cotransfected with the iNOS-Luc and TK-Renilla reporters plus either shGFP or shN5-1 vectors. Transfected cells were stimulated for 20 h with 1 µg/ml Pam3CSK4 (P3C), 300 µg/ml zymosan A (Zym), 100 µg/ml poly I:C (pIC), 25 µg/ml LPS, 1 mM loxoribine (Lox), or 1 µM CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG). Luciferase activity normalized to TK-Renilla is represented as fold induction over the reporter activity in unstimulated cells (−). Graphics show the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (E) RAW 264.7 cells transfected with either shGFP or shN5-1 vectors were left untreated or stimulated with different TLR ligands as in D. Expression of NFAT5, iNOS, and pyruvate kinase (normalization control) was detected by Western blotting. The experiment shown is representative of three independently performed. (F) Nitric oxide production upon 24 h of stimulation with 100 µg/ml pIC or 25 µg/ml LPS in RAW 264.7 cells transfected with either shGFP or shN5-1 vectors. Graphics show the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

TLR-induced NFAT5 expression is regulated by the IKKβ–NF-κB pathway

Activation of TLRs induced a progressive accumulation of NFAT5 protein that was preceded by an increase in its mRNA (Fig. 4, A and B) and was dependent on transcription because it was blunted by the RNA synthesis inhibitors actinomycin d and α-amanitin (Fig. 4 C). The accumulation of NFAT5 protein increased slowly in response to TLRs (Fig. 4 B), and during the first 2 h its abundance was largely insensitive to cycloheximide (CHX), whereas by 4 h a more substantial CHX-sensitive accumulation, suggestive of de novo synthesis, was observed (Fig. 4 D). These results suggested that basal levels of preexisting NFAT5 might be sufficient to initiate expression of genes with fast induction kinetics, such as Tnf, whereas its sustained accumulation at later time points could contribute to prolong the expression of genes with slower induction kinetics, like Nos2.

Involvement of the IKKβ–NF-κB pathway on the expression of NFAT5 in response to TLRs. (A) Quantification of NFAT5 mRNA upon stimulation of BMDMs with 10 µg/ml pIC or 10 ng/ml LPS for the indicated times. mRNA content was measured by RT-qPCR, normalized to L32 mRNA, and is shown relative to unstimulated cells, which was given an arbitrary value of 1. (B) Expression of NFAT5 in BMDMs stimulated with 1 µg/ml pIC or 1 ng/ml LPS for the indicated times was analyzed by Western blot. α-Tubulin is shown as loading control. (C) Western blot for NFAT5 in BMDMs left untreated (−), or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS (20 h) after 1 h of pretreatment with actinomycin d (ActD) or α-amanitin (α-Ama) at the indicated concentrations. Pyruvate kinase (PyrK) is shown as loading control. (D) Western blot for NFAT5 in BMDMs treated with 0.5 µg/ml CHX, 1 ng/ml LPS, or both during different times (CHX was added 30 min before LPS). To ensure the complete extraction of NFAT5 from cells we used urea-based whole-cell lysates. IκBα is shown as a de novo synthesis-dependent TLR-induced protein. α-Tubulin was used as loading control. (E) Schematic representation of the promoter region of the Nfat5 gene. Consensus binding sites for NF-κB (capital letters) and flanking sequences are shown for human, dog, mouse, and pig genomes. CpG-rich designate a CpG island, and the small bar under the NF-κB binding sites in the diagram shows the region amplified by the primers used in the ChIP experiments. The bottom panels show the ChIP analysis of NF-κB (p65) binding to the Nfat5 promoter or an irrelevant region (exon 14 of the Nfat5 gene) in BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 or 4 h. A control rabbit IgG (Ig) was included as negative control. Immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to its respective total chromatin (input). Graphics represent the enrichment in chromatin immunoprecipitated by the NF-κB–specific antibody relative to the immunoprecipitation with the control IgG in unstimulated cells (which was given an arbitrary value of 1). (F) NFAT5 mRNA levels in BMDMs stimulated during 2 h with 10 µg/ml pIC or 10 ng/ml LPS without or with a 1-h pretreatment with 10 µM BAY 11–7082, 2 µM BMS-345541, or 0.1 µg/ml actinomycin d (ActD). (G) Western blot for NFAT5 in BMDMs left untreated (−), or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 20 h without inhibitors or with a 1-h pretreatment with 10 µM BAY 11–7082, 2 µM BMS-345541, 10 µM SB202190, 10 µM PD098059, 10 µM SP600125, 1 µM dexamethasone, 20 µM LY294002, or 200 nM rapamycin. DMSO and ethanol (EtOH) are vehicle controls. (H) Western blot for NFAT5 in WT (IKKβ+/+) and IKKβ-deficient (IKKβ−/−) BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 15 h. Graphics in A, E, and F correspond to the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). Results in B, C, D, G, and H are representative of three independent experiments.

Involvement of the IKKβ–NF-κB pathway on the expression of NFAT5 in response to TLRs. (A) Quantification of NFAT5 mRNA upon stimulation of BMDMs with 10 µg/ml pIC or 10 ng/ml LPS for the indicated times. mRNA content was measured by RT-qPCR, normalized to L32 mRNA, and is shown relative to unstimulated cells, which was given an arbitrary value of 1. (B) Expression of NFAT5 in BMDMs stimulated with 1 µg/ml pIC or 1 ng/ml LPS for the indicated times was analyzed by Western blot. α-Tubulin is shown as loading control. (C) Western blot for NFAT5 in BMDMs left untreated (−), or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS (20 h) after 1 h of pretreatment with actinomycin d (ActD) or α-amanitin (α-Ama) at the indicated concentrations. Pyruvate kinase (PyrK) is shown as loading control. (D) Western blot for NFAT5 in BMDMs treated with 0.5 µg/ml CHX, 1 ng/ml LPS, or both during different times (CHX was added 30 min before LPS). To ensure the complete extraction of NFAT5 from cells we used urea-based whole-cell lysates. IκBα is shown as a de novo synthesis-dependent TLR-induced protein. α-Tubulin was used as loading control. (E) Schematic representation of the promoter region of the Nfat5 gene. Consensus binding sites for NF-κB (capital letters) and flanking sequences are shown for human, dog, mouse, and pig genomes. CpG-rich designate a CpG island, and the small bar under the NF-κB binding sites in the diagram shows the region amplified by the primers used in the ChIP experiments. The bottom panels show the ChIP analysis of NF-κB (p65) binding to the Nfat5 promoter or an irrelevant region (exon 14 of the Nfat5 gene) in BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 or 4 h. A control rabbit IgG (Ig) was included as negative control. Immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to its respective total chromatin (input). Graphics represent the enrichment in chromatin immunoprecipitated by the NF-κB–specific antibody relative to the immunoprecipitation with the control IgG in unstimulated cells (which was given an arbitrary value of 1). (F) NFAT5 mRNA levels in BMDMs stimulated during 2 h with 10 µg/ml pIC or 10 ng/ml LPS without or with a 1-h pretreatment with 10 µM BAY 11–7082, 2 µM BMS-345541, or 0.1 µg/ml actinomycin d (ActD). (G) Western blot for NFAT5 in BMDMs left untreated (−), or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 20 h without inhibitors or with a 1-h pretreatment with 10 µM BAY 11–7082, 2 µM BMS-345541, 10 µM SB202190, 10 µM PD098059, 10 µM SP600125, 1 µM dexamethasone, 20 µM LY294002, or 200 nM rapamycin. DMSO and ethanol (EtOH) are vehicle controls. (H) Western blot for NFAT5 in WT (IKKβ+/+) and IKKβ-deficient (IKKβ−/−) BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 15 h. Graphics in A, E, and F correspond to the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). Results in B, C, D, G, and H are representative of three independent experiments.

The oscillatory pattern of NFAT5 mRNA induction in TLR-stimulated macrophages was reminiscent of NF-κB–regulated genes (Hoffmann et al., 2002) and led us to examine whether this factor might control NFAT5 expression. Analysis of the Nfat5 gene revealed two clear NF-κB consensus binding sites upstream of Nfat5 exon 1 that were remarkably conserved across several mammalian species (Fig. 4 E). ChIP experiments showed that p65 (p65/NF-κB) was readily recruited to these sites upon TLR activation (Fig. 4 E). Moreover, TLR-induced accumulation of Nfat5 mRNA was blunted upon inactivation of IKKβ with two independent pharmacological inhibitors, BAY 11–7082 and BMS-345541, to an extent comparable to that of blocking transcription (Fig. 4 F). In addition, pharmacological and genetic inactivation of IKKβ prevented the long-term accumulation of NFAT5 in response to TLRs, but inhibition of other TLR-activated pathways, such as p38, ERK, JNK, PI3K, and mTOR, did not affect it (Fig. 4, G and H). Altogether, these data indicated that de novo expression of NFAT5 after TLR activation required NF-κB–dependent transcription.

Different mechanisms regulate the TLR-induced recruitment of NFAT5 to its target genes

Our results showed that, although NFAT5 was constitutively bound to target genes that are independent of TLR-induced chromatin remodeling, it required TLR stimulation to be recruited to most targets that are expressed upon chromatin remodeling. In this regard, TLR-induced binding of NFAT5 to Nos2 could be detected after 30 min of stimulation and neared a maximum by 2 h (Fig. 5 A). Because this rapid recruitment occurred before any substantial accumulation of newly synthesized NFAT5 (Fig. 4, B and D), it could be used to monitor the effect of different TLR-activated signals on the specific recruitment of NFAT5 to its targets. We observed that binding of NFAT5 to the Nos2 promoter, induced by a 2-h LPS stimulation, was sensitive to inhibition of IKKβ using two chemically unrelated pharmacological inhibitors (Fig. 5 B). Confirmation of the dependence of NFAT5 recruitment to Nos2 on IKKβ was obtained using IKKβ-deficient BMDMs, in which the LPS-induced binding of NFAT5 to the Nos2 promoter was significantly reduced, to a similar extent as the decrease in p65 activation (Fig. 5 C and Fig. S5 A). In contrast, the constitutive association of NFAT5 with Tnf was maintained in LPS-treated IKKβ-deficient macrophages (Fig. 5 C). We also observed that inhibition of the MAP kinases p38, ERK, and JNK did not prevent the TLR-induced binding of NFAT5 to Nos2 (Fig. 5 D). Because p38 is a major activator of NFAT5 in osmostress responses (Ko et al., 2002; Morancho et al., 2008), this result indicated that NFAT5 binding to TLR- or osmostress-responsive genes likely involved different mechanisms.

Effect of TLR-activated signaling pathways, protein synthesis, and HDAC inhibition on the recruitment of NFAT5 to target genes. (A) Time course of NFAT5 recruitment to the Nos2 promoter in BMDMs stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS was analyzed by ChIP. Chromatin in each sample was immunoprecipitated with preimmune rabbit serum (pi) or NFAT5-specific antibodies (N5) and is represented as relative enrichment after normalization to its respective total chromatin (input). The anti-NFAT5–immunoprecipitated chromatin in unstimulated cells was used as reference sample and given an arbitrary value of 1. (B) BMDMs left untreated (−) or pretreated (1 h) with BAY 11–7082 (5 and 10 µM) or BMS-345541 (2 and 6 µM) were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 h and analyzed by ChIP. The anti-NFAT5–immunoprecipitated chromatin in LPS-stimulated cells was used as reference sample and given an arbitrary value of 100%. (C) The association of NFAT5 with the Nos2 and Tnf promoters in IKKβ+/+ and IKKβ−/− BMDMs after stimulation with 10 ng/ml LPS for 1 h was analyzed by ChIP. (D) BMDMs left untreated (−) or pretreated (1 h) with 10 µM SB202190, 10 µM PD098059, and 10 µM SP600125 were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS during 4 h and subjected to ChIP to analyze the recruitment of NFAT5 to the Nos2 promoter. (E) The association of NFAT5 with the promoter regions of Nos2, Tnf, Ccl2, and the enhancer region of Il12b, was analyzed in WT BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated for 2 h with 0.1 ng/ml or 1 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of 10 µg/ml CHX. Immunoprecipitated chromatin in each sample was normalized to its respective total chromatin (input). The anti-NFAT5–immunoprecipitated chromatin in cells stimulated with 1 ng/ml LPS was used as reference sample and given an arbitrary value of 100%. (F) As in E, but cells were left untreated or treated as indicated with TSA for 5 h, or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 h. The enrichment in chromatin immunoprecipitated by the NFAT5-specific antibodies is represented relative to the amount immunoprecipitated by the NFAT5 antibodies upon LPS stimulation (which was given an arbitrary value of 100). Graphics show the mean ± SEM of three (A, B, C, E, and F) or four (D) independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Effect of TLR-activated signaling pathways, protein synthesis, and HDAC inhibition on the recruitment of NFAT5 to target genes. (A) Time course of NFAT5 recruitment to the Nos2 promoter in BMDMs stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS was analyzed by ChIP. Chromatin in each sample was immunoprecipitated with preimmune rabbit serum (pi) or NFAT5-specific antibodies (N5) and is represented as relative enrichment after normalization to its respective total chromatin (input). The anti-NFAT5–immunoprecipitated chromatin in unstimulated cells was used as reference sample and given an arbitrary value of 1. (B) BMDMs left untreated (−) or pretreated (1 h) with BAY 11–7082 (5 and 10 µM) or BMS-345541 (2 and 6 µM) were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 h and analyzed by ChIP. The anti-NFAT5–immunoprecipitated chromatin in LPS-stimulated cells was used as reference sample and given an arbitrary value of 100%. (C) The association of NFAT5 with the Nos2 and Tnf promoters in IKKβ+/+ and IKKβ−/− BMDMs after stimulation with 10 ng/ml LPS for 1 h was analyzed by ChIP. (D) BMDMs left untreated (−) or pretreated (1 h) with 10 µM SB202190, 10 µM PD098059, and 10 µM SP600125 were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS during 4 h and subjected to ChIP to analyze the recruitment of NFAT5 to the Nos2 promoter. (E) The association of NFAT5 with the promoter regions of Nos2, Tnf, Ccl2, and the enhancer region of Il12b, was analyzed in WT BMDMs left untreated (−) or stimulated for 2 h with 0.1 ng/ml or 1 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of 10 µg/ml CHX. Immunoprecipitated chromatin in each sample was normalized to its respective total chromatin (input). The anti-NFAT5–immunoprecipitated chromatin in cells stimulated with 1 ng/ml LPS was used as reference sample and given an arbitrary value of 100%. (F) As in E, but cells were left untreated or treated as indicated with TSA for 5 h, or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 h. The enrichment in chromatin immunoprecipitated by the NFAT5-specific antibodies is represented relative to the amount immunoprecipitated by the NFAT5 antibodies upon LPS stimulation (which was given an arbitrary value of 100). Graphics show the mean ± SEM of three (A, B, C, E, and F) or four (D) independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

LPS-induced expression of iNOS involves a rapid, NF-κB–dependent removal of repressor complexes associated with HDACs from the Nos2 promoter (Ogawa et al., 2004; Pascual et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2009). Moreover, although it has not been specifically determined for Nos2, TLR-induced chromatin remodeling in other secondary response genes depends on de novo protein synthesis (Weinmann et al., 1999; Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2006). Therefore, we analyzed whether the TLR-induced recruitment of NFAT5 to genes such as Nos2 was also sensitive to de novo protein synthesis and HDAC activity. We observed that binding of NFAT5 to Nos2 and Il12b was decreased by blockade of protein synthesis with CHX in LPS-stimulated cells (Fig. 5 E). In contrast, its constitutive association with the primary response genes Tnf and Ccl2 was not affected by CHX (Fig. 5 E), and, moreover, NFAT5 appeared capable of enhancing the induction of Tnf mRNA despite blockade of protein synthesis because CHX-treated WT macrophages induced it better than NFAT5-deficient ones (Fig. S5 B). In the same experiments, CHX abrogated the induction of Nos2 mRNA (Fig. S5 B). Altogether, these results indicated that preexisting, promoter-bound NFAT5 could enhance the transcription of genes such as Tnf without additional protein synthesis, whereas the inducible recruitment of NFAT5 to other genes, like Nos2, required de novo protein synthesis and IKKβ activity.

We then tested the effect of the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) on the chromatin-binding capacity of NFAT5. TSA induced the binding of NFAT5 to the Nos2 promoter in unstimulated macrophages nearly as efficiently as LPS stimulation (Fig. 5 F). Similarly, association of NFAT5 with the Il12b enhancer was induced by TSA in unstimulated macrophages. These observations indicated that, in the absence of TLR stimulation, inhibition of HDACs sufficed to induce the association of NFAT5 with target genes whose expression requires chromatin remodeling. Although it cannot be ruled out that TSA could cause other effects in addition to inhibiting histone deacetylation, this result lends support to the concept that inhibition of HDACs, which occurs upon TLR activation (Glass and Saijo, 2010), could favor the recruitment of NFAT5 to genes such as Nos2. Altogether, our results indicate that recruitment of NFAT5 to these genes might be sensitive to TLR-induced changes in chromatin configuration involving IKKβ–NF-κB, de novo protein synthesis, and HDAC inhibition.

In vivo response of NFAT5-deficient mice to L. major infection

We next sought to determine the impact of NFAT5 deficiency on the in vivo response against L. major infection, a model in which pathogen clearance requires different TLRs and their adaptor molecule MyD88 (de Veer et al., 2003; Muraille et al., 2003; Kropf et al., 2004a; Tuon et al., 2008). Production of nitric oxide by iNOS, whose gene is a major target for NFAT5 in the response to TLRs, is a key mechanism for the control and clearance of L. major in vivo (Bogdan et al., 2000; Kropf et al., 2004b) and, in addition, Nfat5−/− mice and their WT littermates have a 129/sv background, a resistant strain in which L. major causes a localized infection (Swihart et al., 1995; Lipoldová and Demant, 2006). Mice were infected with a low dose of parasites in the ear or a high dose in the footpad. As expected (Diefenbach et al., 1998), macrophages (F4/80+) of WT mice up-regulated iNOS expression at the inoculation site 24 h after infection (Fig. 6 A) which, after a peak at 48 h, decreased to baseline by 72 h with either high or low doses of infection (Fig. 6 B). In contrast, iNOS expression in macrophages from NFAT5-deficient mice was only mildly up-regulated at 48 h after infection (Fig. 6, A and B). Impaired iNOS expression in skin macrophages of NFAT5-deficient mice correlated well with the 5–20-fold higher parasite burden observed in those mice compared with WT ones 72 h after a high-dose infection (Fig. 6 C), and a 20-fold higher parasite burden in the ear and retromaxillar draining lymph nodes 3 wk after a low-dose infection (Fig. 6 D). Notably, although infection was controlled locally and no parasites were detected in the spleen of WT mice, a marked colonization (∼102 parasites/ spleen) was observed in NFAT5-deficient mice (Fig. 6 E). Therefore, our data show that NFAT5 is a key factor in the in vivo response to Leishmania by contributing to iNOS expression in macrophages and control of L. major replication and dissemination.

In vivo response of NFAT5-deficient mice to L. major infection. (A) Intracellular iNOS expression in macrophages from the footpads of WT (left) and NFAT5-deficient (right) mice after infection with L. major. Mice were injected with PBS (filled histogram) or inoculated with 5 × 105 L. major parasites (thick line histogram) in the footpad. After 24 h, cell suspensions from the skin were stained with antibodies to F4/80 and iNOS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The dotted line represents the staining with an isotype control antibody. A representative experiment of a total of eight performed (each footpad from four mice of each group, WT and KO) is shown. (B) As in A, but the median intensity of fluorescence (MFI) of intracellular iNOS staining in F4/80+ macrophages is represented at the indicated time points. The mean ± SEM of four mice per group is shown. For the 0-h time point, the MFI values for intracellular iNOS correspond to PBS injection. (C and D) Parasite load was determined in the locally infected skin and draining lymph node (dLN), 72 h after high-dose infection in the footpad (C) or 3 wk after low-dose infection in the ear (D). The parasite burden for each individual mouse is depicted in logarithmic scale (Log10). The horizontal bars represent the mean values for each group: (C) footpads (Nfat5+/+ n = 12 and Nfat5−/− n = 16) and popliteal dLN (Nfat5+/+ n = 6 and Nfat5−/− n = 8); (D) ears (Nfat5+/+ n = 30 and Nfat5−/− n = 20) and retromaxillar dLN (Nfat5+/+ n = 15 and Nfat5−/− n = 10). (E) Analysis of parasite dissemination after L. major infection. The graph represents the quantification of the parasite load in the spleen of Nfat5+/+ (n = 15) and Nfat5−/− (n = 10) infected mice 3 wk after a low-dose inoculation. The horizontal bars represent the mean values for each group in logarithmic scale (Log10). All but one WT animal had parasite burdens below the detection limit of the technique (2.2 parasites/ organ). For C, D, and E: three series of independent infections were performed. *, P = 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001, Student’s t test of WT compared with NFAT5-deficient mice.

In vivo response of NFAT5-deficient mice to L. major infection. (A) Intracellular iNOS expression in macrophages from the footpads of WT (left) and NFAT5-deficient (right) mice after infection with L. major. Mice were injected with PBS (filled histogram) or inoculated with 5 × 105 L. major parasites (thick line histogram) in the footpad. After 24 h, cell suspensions from the skin were stained with antibodies to F4/80 and iNOS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The dotted line represents the staining with an isotype control antibody. A representative experiment of a total of eight performed (each footpad from four mice of each group, WT and KO) is shown. (B) As in A, but the median intensity of fluorescence (MFI) of intracellular iNOS staining in F4/80+ macrophages is represented at the indicated time points. The mean ± SEM of four mice per group is shown. For the 0-h time point, the MFI values for intracellular iNOS correspond to PBS injection. (C and D) Parasite load was determined in the locally infected skin and draining lymph node (dLN), 72 h after high-dose infection in the footpad (C) or 3 wk after low-dose infection in the ear (D). The parasite burden for each individual mouse is depicted in logarithmic scale (Log10). The horizontal bars represent the mean values for each group: (C) footpads (Nfat5+/+ n = 12 and Nfat5−/− n = 16) and popliteal dLN (Nfat5+/+ n = 6 and Nfat5−/− n = 8); (D) ears (Nfat5+/+ n = 30 and Nfat5−/− n = 20) and retromaxillar dLN (Nfat5+/+ n = 15 and Nfat5−/− n = 10). (E) Analysis of parasite dissemination after L. major infection. The graph represents the quantification of the parasite load in the spleen of Nfat5+/+ (n = 15) and Nfat5−/− (n = 10) infected mice 3 wk after a low-dose inoculation. The horizontal bars represent the mean values for each group in logarithmic scale (Log10). All but one WT animal had parasite burdens below the detection limit of the technique (2.2 parasites/ organ). For C, D, and E: three series of independent infections were performed. *, P = 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001, Student’s t test of WT compared with NFAT5-deficient mice.

DISCUSSION

Regulation of gene expression induced by TLRs must integrate variables such as the type of stimulus, the signal strength, and even the repeated encounter with the pathogen they recognize (Foster et al., 2007; Litvak et al., 2009). Current knowledge on transcriptional regulators and mechanisms involved in the induction of specific genes downstream TLRs is still incomplete. In this study, we identify NFAT5 as a key regulator of gene expression in macrophages in response to TLR stimulation and show that it is required for efficient anti-pathogen responses in vivo. Remarkably, this function of NFAT5 is independent of its previously characterized role in the adaptation to hypertonic stress.

Until very recently, NF-κB proteins were the only Rel-like transcription factors known to be involved in innate immune responses activated by receptors that recognize pathogens. This notion was changed by findings describing that calcineurin-regulated NFATc proteins are activated in innate immune cells by the LPS receptor CD14 or the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1, although not by TLRs (Goodridge et al., 2007; Zanoni et al., 2009; Greenblatt et al., 2010). Our work now reveals that NFAT5, a distinct Rel-like protein with functional and structural features shared with NF-κB and NFATc proteins, is also a regulator of TLR-induced gene expression. It remains to be addressed whether, like other Rel-domain transcription factors, NFAT5 is involved in responses mediated by other pattern-recognition receptors, such as RIG-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors, and NOD-like receptors (Geijtenbeek and Gringhuis, 2009; Takeuchi and Akira, 2010).

NFAT5 controlled the expression of a set of genes involved in different aspects of the response to pathogens. Some of the NFAT5-regulated genes identified here (Tnf and Ccl2) can be also induced by NFAT5 in macrophages under osmotic stress (Roth et al., 2010). However, we found that other genes previously shown to be inducible by osmotic stress in an NFAT5-dependent manner, such as Vegfc and Nfkbia (Machnik et al., 2009; Roth et al., 2010), did not require NFAT5 to be expressed in response to LPS. In addition, TLR stimulation did not induce any of the NFAT5-target genes, such as Hspa1b, Akr1b3, and Slc5a, which are characteristically expressed upon osmostress in numerous cell types (Aramburu et al., 2006). Although microarray studies of osmoresponsive genes in macrophages have not been reported, it seems likely that NFAT5 might be able to regulate some genes under both types of stimuli: TLR and osmotic stress. Nonetheless, the overlapping would be limited, as osmotic stress and TLRs use different signaling pathways and contexts of transcriptional regulators.

The requirement of NFAT5 for the expression of TLR-regulated genes such as Tnf and Il6, particularly under low stimulus doses, suggests a role for this factor in coupling the strength of signal input to the specificity of gene expression. This property of NFAT5 recalls the requirement for C/EBPδ in Il6 induction during persistent, but not transient, TLR4 responses (Litvak et al., 2009). Therefore, NFAT5 and C/EBPδ represent examples of transcription factors capable of selectively regulating gene expression in the low and high ranges of TLR stimulation. In this regard, NFAT5 could be well suited for fine tuning the expression of its target genes by lowering their inducibility threshold.

The ability of NFAT5 to regulate genes with different transcriptional requirements suggests that it could participate in diverse architectures of transcriptional complexes. In this regard, NFAT5 showed two distinct patterns of association with its target genes: it required TLR activation and de novo protein synthesis to bind a subset of them but was constitutively bound to others regardless of stimulation. Genes to which NFAT5 was bound in basal conditions were primary response, whereas genes to which its binding required TLR stimulation were chromatin remodeling dependent. These observations fit the notion that numerous primary response genes, such as Tnf, are already bound by certain transcription regulators and chromatin remodeling complexes in basal conditions, which likely facilitates their rapid induction upon TLR activation (Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2006; Hargreaves et al., 2009). This finding also recalls earlier works describing a constitutive nuclear pool of NFAT5 in different cell types (López-Rodríguez et al., 1999b, 2001) and raises the question of whether this factor might mark a wider set of genes to facilitate their response to diverse stimuli.

The dependence of NFAT5 on de novo protein synthesis for binding to genes such as Nos2 or Il12b did not seem to be a result of new synthesis of NFAT5 itself because its abundance was minimally affected by CHX during the stimulation time used in these experiments (2 h), and it strongly suggests that NFAT5 could require a TLR-induced regulator to be recruited to this group of genes. Binding of NFAT5 to these genes could also be induced without TLR stimulation by inhibiting HDACs with TSA. Although it cannot be ruled out that TSA could act through other mechanisms in addition to inhibiting histone deacetylation, this result suggests that TLR-induced recruitment of NFAT5 to target genes might be primarily controlled by chromatin accessibility. Further analysis showed that recruitment of NFAT5 to Nos2 required IKKβ, which could potentially act through diverse mechanisms, such as causing posttranslational modifications in NFAT5 or regulatory factors, or inducing, via NF-κB, the de novo expression of a chromatin modifier or a potential NFAT5 partner. Although it remains to be determined whether the need of de novo protein synthesis, sensitivity to HDACs, and regulation by IKKβ are part of a common mechanism, our combined results suggest that access of NFAT5 to Nos2 and other genes might be controlled by TLR-activated and/or de novo synthesized factors capable of influencing chromatin configuration. Such interpretation is consistent with works showing that TLR-induced chromatin remodeling of genes such as Il12b and Il6 requires de novo protein synthesis (Weinmann et al., 1999; Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2006). In addition, TLRs induce the expression of transcriptional regulators and proteins with chromatin remodeling activity, such as C/EBPδ, IκBβ, JMJD3, IκBζ, and IKKε (Yamamoto et al., 2004; De Santa et al., 2007; Kayama et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2009; Litvak et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2010), and TLR-activated NF-κB can de-repress genes such as Nos2 by clearing HDAC complexes (Huang et al., 2009; Glass and Saijo, 2010). The finding that recruitment of NFAT5 to some of its targets depends on protein synthesis also illustrates one mechanism by which de novo protein expression could control the induction of certain secondary response genes.

We found that the NF-κB pathway regulates NFAT5 accumulation downstream of TLRs. As shown recently, the NF-κB pathway can adjust the expression of genes in response to persistent TLR signals by controlling the induction of C/EBPδ (Litvak et al., 2009). The regulation of NFAT5 expression by NF-κB, and its being particularly required for the induction of certain genes, such as Il6, at low doses of stimuli, suggest that NFAT5 could be a relevant component in specific NF-κB–regulated coherent feed-forward loops of transcriptional circuits involved in sensing low input signals from TLRs (Shoval and Alon, 2010). In addition, the progressive NF-κB–dependent increase of NFAT5 in TLR-stimulated macrophages could be particularly important to sustain the expression of genes with slow induction kinetics, such as Nos2 or Il6.

Finally, our analysis revealed NFAT5 as a key host factor required for controlling infection by L. major, whose clearance strongly depends on TLRs (Tuon et al., 2008) and iNOS production by macrophages (Bogdan et al., 2000; Kropf et al., 2004b). NFAT5-null mice exhibited defective control of the parasite burden at the point of infection and presented colonization of the spleen, resembling the phenotype described for iNOS-deficient mice (Diefenbach et al., 1998), and, indeed, also displayed reduced iNOS expression in local macrophages during L. major infection. The dissemination of the parasite to organs such as the spleen in NFAT5-deficient mice was indicative of visceral leishmaniasis, the most pernicious manifestation of chronic Leishmania infection in humans (Engwerda and Kaye, 2000). These findings underscore the biological relevance of NFAT5 in the response to pathogens, as they show that its deficiency can cause normally resistant 129/sv mice to become highly susceptible to L. major.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Mice heterozygous for Nfat5 were described previously (López-Rodríguez et al., 2004). Because NFAT5-null mice in a mixed 129/sv-C57BL/6 background had a severe mortality rate from late embryonic development to early perinatal stages (Go et al., 2004; López-Rodríguez et al., 2004), we bred them for >10 generations to a pure 129/sv background and observed that the rate of survival of NFAT5-null mice (Nfat5−/−) increased, with >30% of the expected Mendelian ratio of Nfat5−/− mice reaching adulthood. Nfat5+/− mice were maintained in an isogenic 129/sv background and were crossed to obtain Nfat5−/− mice and control Nfat5+/+ littermates. Conditional mice that lack IKKβ in macrophages, Ikbkbfl/fl,Lys-M-Cre, were generated crossing Lys-M-Cre mice with Ikbkbfl/fl mice. Lys-M-Cre mice (Clausen et al., 1999) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and the Ikbkbfl/fl mice were provided by M. Schmidt-Supprian (Pasparakis et al., 2002). Ikbkbfl/fl,Lys-M-Cre (IKKβ−/−) and littermate Ikbkbwt/wt,Lys-M-Cre or Ikbkbfl/fl control mice (IKKβ+/+) were maintained on a pure C57BL/6 background. All mice were analyzed between 6 and 8 wk of age. Mice were bred and maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions, and animal handling was performed according to institutional guidelines approved by the ethical committee (PRBB/UPF Animal Care and Use Committee).

In vivo infection with Leishmania.

For parasite challenge, L. major parasites clone V1 (MHOM/IL/80/Friedlin; provided by M. Soto, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain) were kept in a virulent state by passage in BALB/c mice. The L. major amastigotes were obtained from popliteal lymph nodes of infected BALB/c mice. For transformation from amastigotes to promastigotes, parasites were cultured at 26°C in Schneider’s medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum. Infective-stage metacyclic promastigotes were isolated from stationary cultures by negative selection using peanut agglutinin (Vector Laboratories; Sacks et al., 1985). Nfat5−/− or littermate control male mice were infected either by intradermal inoculation of 104 metacyclic promastigotes of L. major into the dermis of both ears of each mouse (low dose) or by subcutaneous inoculation in both footpads with 5 × 105 metacyclic promastigotes (high dose). Three series of independent infections were performed. The limiting dilution assay (Buffet et al., 1995) was used to determine the number of parasites. In brief, homogenized ear and footpad tissue, and mechanically dissociated lymph nodes and spleens, were serially diluted in a 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plate containing Schneider’s medium plus 20% FCS. The number of viable parasites was determined from the highest dilution at which promastigotes could be grown after up to 7 d of incubation at 26°C. In the ear, local draining lymph nodes of infected ears (retromaxillary) and footpad (popliteal), and spleen, the parasite load is expressed as the number of parasites in the whole organ. In the footpad, the parasite load is expressed as the number of parasites per microgram of tissue. iNOS protein expression was assessed by flow cytometry after intracellular staining, as previously described (Angulo et al., 2000). At the indicated times after L. major infection, footpad sections and ears were recovered from the infected mice as previously described (Iborra et al., 2005). In brief, the ventral and dorsal sheets of the infected ears were separated. The footpad sections and ear sheets were placed in DME containing 50 µg/ml Liberase CI enzyme blend (Roche). After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the tissues were cut into small pieces, homogenized, and filtered using a cell strainer (70-µm pore size). Cells were first incubated with an antibody to the Fcγ receptor (BD) and then stained for surface F4/80 (APC-conjugated antibody to mouse F4/80; eBioscience), fixed, and incubated with a monoclonal antibody to iNOS during permeabilization (Dako). FITC-conjugated iNOS antibody (BD), or the appropriate FITC-conjugated mouse IgG2a isotype control, was used. Events were acquired using a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD) and data were analyzed using FACSDiva (BD) and FlowJo (Tree Star) software.

Reagents.

Pam3CSK4 was from InvivoGen; zymosan A, polyI:C, LPS from E. coli 055:B5, and loxoribine were from Sigma-Aldrich; CpG DNA was from Hycult Biotechnology; and recombinant mouse IFN-γ was purchased from ImmunoTools. Formaldehyde, sodium chloride, Trizma base, glycine, EDTA, iodoacetamide, sodium pyrophosphate (NaPPi), sodium orthovanadate, β-glycerophosphate, PMSF, leupeptin, pepstatin A, aprotinin, SDS, Tween-20, glycine, methanol, Triton X-100 (TX-100), Nonidet P-40, sodium deoxycholate, actinomycin d, dexamethasone, TSA, and CHX were from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium fluoride (NaF) was from Merck. α-Amanitin, SB202190, PD98059, SP600125, BAY 11–7082, BMS-345541, LY294002, and rapamycin were from EMD.

Isolation of cells and cell culture.

Mouse RAW 264.7 macrophage cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone or Invitrogen), 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen), 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen; complete RPMI medium). To obtain BMDMs, 6–8-wk-old mice were sacrificed and the femoral and tibial marrow was flushed from the bones with DME supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate plus penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen; incomplete medium). Cells were then resuspended in complete DME media (incomplete supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum) with 25% (vol/vol) L929-conditioned medium (as the source of macrophage-colony stimulating factor) and incubated for 7 d in polystyrene dishes. Differentiated macrophages were harvested with PBS plus 1 mM EDTA by gentle pipetting, washed with PBS, and plated in tissue culture plates for Western blot, mRNA, and ELISA analysis (2 × 106 cells/3 ml/well). Where indicated, the culture medium was made hypertonic (500 mOsm/kg) by the addition of 90 mM NaCl from a sterile 4 M stock solution. Osmolality was measured with a vapor pressure osmometer (VAPRO 5520; Wescor).

RAW 264.7 transfection, luciferase assay, and quantification of nitrite levels.

RAW 264.7 cells were transfected by electroporation. In brief, 10 × 106 cells in 0.4 ml of ice-cold complete RPMI medium with 20 µg of DNA per cuvette (4-mm gap width; Isogen) were electroporated in a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 320 V and 975 µF (time constant ranging from 22 to 30 ms). For reporter gene experiments, cells were lysed in passive lysis buffer (PLB; Promega) at 25 × 106 cells/ml and the activity of Firefly and Renilla luciferases was measured with the Dual-luciferase reporter system (Promega) with a Berthold FB12 luminometer (Berthold). Firefly luciferase units were normalized with respect to the activity of Renilla luciferase. The concentration of nitrite produced by RAW 264.7 cells was determined using the Griess assay (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s indications. Experiments in RAW 264.7 cells were done with higher doses of TLR ligands than those used in primary macrophages because these were required to induce a robust activation of the iNOS-Luc reporter and, consequently, high doses were also used for the rest of experiments in this cell line.

Plasmid constructs.

The NFAT5-dependent reporter, ORE-Luc, was previously described (López-Rodríguez et al., 2001), and the iNOS-luc reporter (−1,584 to +161 from the mouse Nos2 gene) was provided by S. Lamas (Centro de Investigaciones Biológica–Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid, Spain). The transfection control plasmid TK-Renilla was from Promega. The GFP-specific shRNA in the pBSU6 vector was previously described (Sui et al., 2002) and the two NFAT5-specific shRNAs were done by inserting the following 21-nt sequences complementary to NFAT5 mRNA in pBSU6: shNFAT5-1 (shN5-1; Drews-Elger et al., 2009), 5′-GGTCAAACGACGAGATTGTGA-3′, coding sequence common for both human and mouse NFAT5, and shNFAT5-2 (shN5-2), 5′-GGCTGACAGCGTCCATCAACA-3′, coding sequence for mouse NFAT5. Site-directed mutagenesis of the NFAT5 binding site in the iNOS-luc reporter was done using the QuickChange site directed mutagenesis system of Stratagene according to the manufacturer’s instructions and using the following primers: 5′-CACTTTCATAATGCTAAATTCCATGCCATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CATGGCATGGAATTTAGCATTATGAAAGTG-3′ (reverse).

Immunoblot assays.

For protein detection by Western blotting, BMDMs were lysed in TX-100 lysis buffer (0.5–1 × 106 cells in 100–200 µl; 1% TX-100, 40 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaPPi, 10 mM β-glycerophophate, 1 mM PMSF, 5 µg/ml leupeptin, 5 µg/ml aprotinin and 1 µg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mM NaF, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate). Protein concentration in the lysates was quantified using the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to ensure loading the same amount of protein per sample in the gels. Lysates in Fig.4 D were obtained by lysing 2 × 106 cells in 150 µl of urea lysis buffer (8 M urea, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM iodoacetamide, 1 mM PMSF, 5 µg/ml leupeptin, 5 µg/ml aprotinin, and 1 µg/ml pepstatin A). Lysates were boiled in reducing 1× Laemmli buffer, and 10–50 µg of total protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE (PAGE) and transferred to PROTRAN (BA83; Schleicher & Schuell) membranes in 25 mM Tris, pH 8.4, 192 mM glycine, and 20% methanol. IRF3 dimers were resolved by native PAGE, as described previously (Iwamura et al., 2001). In brief, BMDMs were lysed in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaPPi, 10 mM β-glycerophophate, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, 5 µg/ml of leupeptin/aprotinin, 1 µg/ml pepstatin A, and 1% Nonidet P-40). Native acrylamide gels (7.5%) were pre-run using 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 192 mM glycine as cathode buffer, and 1% deoxycholate (DOC) as anode buffer for 30 min at 40 mA. Samples were electrophoresed for 90 min at 20 mA. Gels were then transferred to PROTRAN membranes as indicated above. After blocking the membranes with 5% dry milk in TBS, the following antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal NFAT5-specific antibody (Affinity BioReagents) recognizes the last 17 carboxy-terminal amino acids. Goat antibody to pyruvate kinase was from Chemicon. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to iNOS and to IκBα, and mouse monoclonal antibody to α-tubulin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Mouse monoclonal antibody to IKKβ was from Imgenex. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to phospho-p38 (pT180/pY182), to phospho-ERK1/2 (pT202/pY204), and to phospho-JNK/SAPK (pT183/pY185) were from BD. Rabbit polyclonal antibody to phospho-MAPKAPK-2 (pT222) was from Cell Signaling Technology. Rabbit polyclonal antibody to IRF3 was from Invitrogen. The antibody to goat IgG coupled to HRP was from Dako, and the antibody to mouse IgG and to rabbit IgG coupled to HRP were from GE Healthcare. Protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence, using Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Flow cytometry.

2 × 105 cells were blocked for 20 min in 1× PBS containing 10% FBS, 0.1% sodium azide, and 0.2 µg of an antibody to the Fcγ receptor (BD). Cells were then incubated with surface marker-specific antibodies in the same solution (1 µg of antibody for 106 cells) and analyzed with a FACScan flow cytometer and CellQuest software (BD). FITC-labeled antibodies to CD11b (BD) or F4/80 (AbD Serotec) were used.

Measurement of mRNA levels.

Total RNA from BMDMs (2 × 106) was isolated using the High Pure RNA Isolation kit (Roche), quantified in a NanoDrop (ND-1000) spectrophotometer, and 1–2 µg of total RNA (50–100 ng for RNA from peritoneal macrophages) was retro-transcribed to cDNA using SuperScript III reverse transcription and random primers (Invitrogen). For real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche), LightCycler 480 Multiwell Plate (Roche), and the LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche) were used according to the instructions provided by the manufacturers. Samples were normalized to L32 (L32 ribosomal protein gene) mRNA levels using the LightCycler Software, version 1.5. Primer sequences for the PCR reactions are described in Table S2.

Microarray analysis.

2 × 106 BMDMs left untreated or stimulated for 6 h with 0.3 ng/ml LPS were lysed in 300 µl RLT buffer (RNeasy system; QIAGEN) and total RNA was isolated using the same system. The RNA integrity was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Labeling and hybridizations were performed according to protocols from Affymetrix. In brief, 100–300 ng of total RNA were amplified and labeled using the WT Sense Target labeling system and control reagents (Affymetrix), and then hybridized to Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Array (Affymetrix). Washing and scanning were performed using the GeneChip System of Affymetrix (GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640, GeneChip Fluidics Station 450, and GeneChip Scanner 7G). Microarray hybridizations were performed for each experimental condition using BMDMs isolated from four independent Nfat5+/+ or Nfat5−/− mice. Microarray data analysis was performed as follows: the robust microarray analysis algorithm was used for background correction (Bolstad et al., 2003; Irizarry et al., 2003a,b), intra- and inter-microarray normalization, and expression signal calculation. Once the absolute expression signal for each gene was calculated in each microarray, the method called significance analysis of microarray (Tusher et al., 2001) was applied to calculate significant differential expression between samples providing p-values adjusted to multiple testing by using false discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). A false discovery rate cutoff value of 0.1 was used for the differential expression results. All the analysis was done using R and Bioconductor packages. The microarray data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds) under the accession no. GSE26343.

ChIP.

BMDMs, grown in 15-cm-diameter polystyrene dishes (20–25 × 106 cells) and stimulated with poly I:C or LPS, as indicated in figure legends, were fixed with 0.75% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Formaldehyde was then quenched with glycine (final concentration 0.26 M) for 5 min. After washing the plates twice with cold PBS, cells were collected with cell scrapers, lysed in 0.75 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% TX-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 5 µg/ml leupeptin/aprotinin, 1 µg/ml pepstatin A, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate) for 30 min on ice. Lysates were sonicated (Branson 250; Branson Sonic Power) for five cycles of 10 s with constant frequency and intensity 4, to obtain DNA fragments between 500 and 1,000 bp, and centrifuged to remove insoluble debris. Supernatants were collected and 5% of each sample was separated to use as a measure of chromatin input for normalization. The rest of the sample was diluted 10× in dilution buffer (1% TX-100, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, 5 µg/ml leupeptin, 5 µg/ml aprotinin, 1 µg/ml pepstatin A, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate) for immunoprecipitation. Samples were precleared with protein A Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) that were previously pre-adsorbed with fish sperm DNA (Roche) and bovine serum albumin (New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 4°C. Specific antibodies were added after removing the pre-clearing beads. To immunoprecipitate NFAT5, a mixture of two rabbit polyclonal antibodies to NFAT5 specific for its amino-terminal or DNA binding domain regions (López-Rodríguez et al., 1999b) was used, and preimmune serum served as control. To immunoprecipitate NF-κB, an antibody to p65 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used and normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was included as a control. Antibodies were then added to the lysates and incubated overnight at 4°C. Pre-adsorbed protein A Sepharose beads were then added, incubated for 1 h at 4°C, and then washed three times with washing buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% TX-100, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 2 mM EDTA, and 150 mM NaCl) and once with final washing buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% TX-100, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 2 mM EDTA, and 500 mM NaCl). To elute the DNA, beads were incubated with elution buffer (1% SDS and 100 mM NaHCO3) for 15 min at room temperature. To reverse the cross-linking, samples were incubated overnight at 65°C with 6 ng/µl RNase (Roche) and DNA was purified using the QIAGEN PCR purification system. DNA was then subjected to RT-qPCR using the primers described in Table S2. Immunoprecipitated DNA from each sample was normalized to its respective chromatin input.

Cytokine production.

Supernatants from the same cultures (2 × 106 cells in 3 ml of media) from which RNA was processed were harvested and TNF and IL-6 were measured by ELISA (R&D Systems) with an Opsys MR plate reader (Dynex Technologies).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance of the experimental data were determined by the paired Student’s t test.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows the induction of a group of poly I:C–induced genes in NFAT5-deficient macrophages, and also shows the effect of NFAT5 in the expression of iNOS/Nos2 in macrophages stimulated with the combination of LPS plus IFN-γ. Fig. S2 shows that macrophages isolated from the BM of NFAT5-deficient mice differentiate normally and display normal activation of the major signaling pathways downstream TLRs. Fig. S3 shows that in vitro differentiation and TLR-mediated activation of macrophages do not cause an osmotic stress response. Fig. S4 illustrates the potential binding sites for NFAT5 in various target genes, and shows its association with a group of targets upon poly I:C stimulation of macrophages. Fig. S5 displays controls for the effect of IKKβ deletion in macrophages, and also shows the expression of Tnf and Nos2 in response to LPS in NFAT5-deficient macrophages pretreated with CHX. Table S1 lists genes that are differentially expressed between LPS-treated control and NFAT5-deficient BMDMs. Table S2 includes a list of the primers used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We greatly acknowledge Drs. Andrea Cerutti, Angel Corbí, and Miguel López-Botet for insightful comments and critical reading of the manuscript. The authors thank Drs. Carlos Ardavín, Lisardo Boscá, Antonio Celada, Santiago Lamas, Pura Muñoz-Cánoves, and Manuel Soto for reagents, and Dr. Marc Schmidt-Supprian for IKKβ floxed mice. We also thank Drs. Encarna Fermiñán, Diego Alonso, and Lara Nonell for assistance with microarray processing and analysis. We thank Adam Espí for technical assistance with mouse genotyping.

C. López-Rodríguez was supported by the Ramón y Cajal and I3 Researchers Programmes and grants from the Spanish Government (SAF2006-04913 and SAF2009-08066) and European Union (MCIRG516308). J. Aramburu was supported by grants from the Spanish Government (BFU2008-01070 and SAF2011-24268), and Distinció de la Generalitat de Catalunya per a la Promoció de la Recerca Universitària. Research in the laboratories of C. López-Rodríguez and J. Aramburu is also supported by Fundació la Marató TV3 (030230/31, 080730), Spanish Ministry of Health (ISCIII-RETIC RD06/0009-FEDER), and Generalitat de Catalunya (2009 SGR 601). M. Buxadé was supported by a Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral contract from Generalitat de Catalunya. S. Iborra was supported by a Sara Borrell postdoctoral contract from the Ministry of Health of Spain. J. Minguillón and R. Berga-Bolaños were supported by predoctoral fellowships from the Spanish Government.