Type I interferons (IFNs) activate differential cellular responses through a shared cell surface receptor composed of the two subunits, IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. We propose here a mechanistic model for how IFN receptor plasticity is regulated on the level of receptor dimerization. Quantitative single-molecule imaging of receptor assembly in the plasma membrane of living cells clearly identified IFN-induced dimerization of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. The negative feedback regulator ubiquitin-specific protease 18 (USP18) potently interferes with the recruitment of IFNAR1 into the ternary complex, probably by impeding complex stabilization related to the associated Janus kinases. Thus, the responsiveness to IFNα2 is potently down-regulated after the first wave of gene induction, while IFNβ, due to its ∼100-fold higher binding affinity, is still able to efficiently recruit IFNAR1. Consistent with functional data, this novel regulatory mechanism at the level of receptor assembly explains how signaling by IFNβ is maintained over longer times compared with IFNα2 as a temporally encoded cause of functional receptor plasticity.

Introduction

Functional plasticity, i.e., the ability to elicit differential cellular responses through the same cell surface receptor by means of different ligands, is a frequently observed feature of cytokine receptor signaling (Moraga et al., 2014), which plays an important role for drug development (Schreiber and Walter, 2010). The molecular mechanisms regulating functional plasticity have so far remained unclear, though some common determinants are emerging (Moraga et al., 2014). A prominent paradigm of cytokine receptor plasticity is the type I interferon (IFN) receptor. All 15 members of the human IFN family recruit a shared cell surface receptor comprising the subunits IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 (Uzé et al., 1992, 2007; Novick et al., 1994; Pestka et al., 2004), through which they activate a broad spectrum of defense mechanisms against pathogen infection and malignancy development (Deonarain et al., 2002; Parmar and Platanias, 2003; Decker et al., 2005; Hertzog and Williams, 2013; Schneider et al., 2014). Differential cellular responses activated by different IFNs have been reported for numerous instances (Abramovich et al., 1994; Rani et al., 1996; Coelho et al., 2005; Uzé et al., 2007). Although all IFNs induce antiviral activity with very similar potencies, other cellular responses regulating proliferation and differentiation are much more potently induced by IFNβ compared with IFNα subtypes. Detailed mutational studies on the IFN–receptor interaction (Piehler and Schreiber, 1999b; Runkel et al., 2000; Roisman et al., 2001; Cajean-Feroldi et al., 2004; Lamken et al., 2005; Strunk et al., 2008), as well as extensive low- and high-resolution structural data on the binary and ternary complexes (Chill et al., 2003; Quadt-Akabayov et al., 2006; Li et al., 2008; Strunk et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2011; de Weerd et al., 2013), clearly established that, rather than differences in the structure, the diverse binding affinities of IFNs toward the receptor subunits are responsible for differential signaling (Subramaniam et al., 1995; Russell-Harde et al., 1999; Lamken et al., 2004; Jaks et al., 2007; Lavoie et al., 2011). In particular, the ∼100-fold higher binding affinity toward IFNAR1 observed for IFNβ compared with IFNα subtypes was suggested to be responsible for unique functions attributed to IFNβ (Domanski et al., 1998; Russell-Harde et al., 1999; Lamken et al., 2004). Strikingly, functional properties specific to IFNβ could be very well mimicked by IFNα2 mutants with similar binding affinities toward IFNAR1 (Jaitin et al., 2006; Kalie et al., 2007). The critical role of the binding affinity toward IFNAR1 suggested that recruitment of this low-affinity receptor subunit into the signaling complex plays an important regulatory role in receptor plasticity (Piehler et al., 2012). Quantitative studies of IFN-induced receptor assembly on artificial membranes indeed suggested that, at physiological receptor concentrations in the plasma membrane (typically 0.1–1/µm2), receptor dimerization by IFNα2 may be much less effective than by IFNβ (Lamken et al., 2004; Jaitin et al., 2006).

Recently, ubiquitin-specific protease 18 (USP18) was identified as a negative feedback regulator of IFN signaling (Malakhova et al., 2006), and was shown to be a key determinant for the differential activity of IFNα2 and IFNβ (François-Newton et al., 2011; Francois-Newton et al., 2012). Interestingly, USP18 was found to interfere with IFN binding and uptake without significant alteration of the receptor density (François-Newton et al., 2011), probably acting via an interaction with the cytosolic domain of IFNAR2 (Malakhova et al., 2006; Löchte et al., 2014). This evidence suggests a potential regulatory mechanism of USP18 on the level of receptor assembly. Here, we aimed to pinpoint the mechanism of type I interferon receptor (IFNAR) assembly in living cells in a quantitative manner to define the role of IFNAR1 binding affinity as well as the regulatory function of USP18 for the formation of the ternary signaling complex. Because, according to the law of mass action, the receptor density determines the equilibrium between binary and ternary complex on the plasma membrane (Fig. 1 a), we established single-molecule imaging techniques that were able to monitor and quantify protein–protein interactions on the cell surface at physiological receptor expression levels. For probing dimerization of endogenous receptors, we used fluorescently labeled IFNs with engineered binding affinities as reporters. Moreover, using tagged versions of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 expressed at physiological levels, we established quantitative single-molecule receptor dimerization assays based on dual-color single-molecule colocalization and colocomotion assays (Schütz et al., 1998; Koyama-Honda et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2007, 2012; Low-Nam et al., 2011). We unambiguously demonstrate IFN-induced dimerization of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 and the limiting role of IFNAR1 binding affinity in complex assembly. Interestingly, the dynamic equilibrium between binary and ternary complexes is modulated by USP18, which appears to interfere with cytosolic stabilization likely mediated by the Janus kinases (JAKs). Based on these insights, we propose a model describing how IFN receptor plasticity is regulated at the level of receptor assembly.

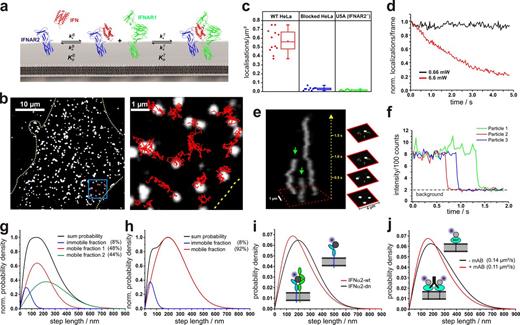

Single-molecule localization and tracking of DY647IFN binding to endogenous cell surface IFNAR. (a) Ligand-induced assembly of a dynamic ternary complex. The effective ligand binding affinity to the cell surface receptor depends on the dynamic equilibrium between the binary and ternary complex. (b) Live-cell IFNα2 binding assay by single-molecule imaging on HeLa. (b, left) A fluorescence image showing individual DY647IFNα2-wt bound to the cell surface receptor. (b, right) Trajectories of IFNα2-wt molecules from the boxed region. The boundaries of the cell are indicated by a yellow dotted line. (c) Density of DY647IFNα2-wt molecules localized on the surface of individual HeLa cells imaged in the presence of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-wt. For comparison, the density of DY647IFNα2-wt molecules on HeLa cells blocked with unlabeled IFNα2-wt is shown in addition to IFNAR2-deficient U5A cells. Data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (closed square), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range) is shown. (d) Normalized bleaching of DY647IFNα2-wt (>150 particles at t = 0) bound to endogenous receptors on HeLa at standard conditions and 10-fold increased laser power. Representative curves are shown for at least five experiments. (e) Single-step bleaching of labeled IFNs depicted as a 3D kymograph. Bleaching events are indicated by green arrows. (f) Single-step bleaching events of three individually labeled IFNs (representative curves for >100 bleached particles). (g) Diffusion properties of cell-bound DY647IFNα2-wt presented as the step length distribution for a time lapse of 160 ms (5 frames, black curve), which was obtained by fitting the step length histogram by considering three components corresponding to an immobile as well as a slow and a fast mobile fraction (Fig. S1). (h) Diffusion properties of cell-bound DY647IFNα2-dn and fit according to a two-component model. (i) Comparison of the step-length histogram for DY647IFNα2-wt and DY647IFNα2-dn. The data shown in g–i are pooled from at least two independent experiments, each with >650 analyzed trajectories (≥15 steps) per IFN mutant. (j) Changes in mobility of a model transmembrane protein dimerized by a monoclonal antibody. The data shown are pooled from eight independent experiments with >400 analyzed trajectories for each experiment (≥15 steps).

Single-molecule localization and tracking of DY647IFN binding to endogenous cell surface IFNAR. (a) Ligand-induced assembly of a dynamic ternary complex. The effective ligand binding affinity to the cell surface receptor depends on the dynamic equilibrium between the binary and ternary complex. (b) Live-cell IFNα2 binding assay by single-molecule imaging on HeLa. (b, left) A fluorescence image showing individual DY647IFNα2-wt bound to the cell surface receptor. (b, right) Trajectories of IFNα2-wt molecules from the boxed region. The boundaries of the cell are indicated by a yellow dotted line. (c) Density of DY647IFNα2-wt molecules localized on the surface of individual HeLa cells imaged in the presence of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-wt. For comparison, the density of DY647IFNα2-wt molecules on HeLa cells blocked with unlabeled IFNα2-wt is shown in addition to IFNAR2-deficient U5A cells. Data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (closed square), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range) is shown. (d) Normalized bleaching of DY647IFNα2-wt (>150 particles at t = 0) bound to endogenous receptors on HeLa at standard conditions and 10-fold increased laser power. Representative curves are shown for at least five experiments. (e) Single-step bleaching of labeled IFNs depicted as a 3D kymograph. Bleaching events are indicated by green arrows. (f) Single-step bleaching events of three individually labeled IFNs (representative curves for >100 bleached particles). (g) Diffusion properties of cell-bound DY647IFNα2-wt presented as the step length distribution for a time lapse of 160 ms (5 frames, black curve), which was obtained by fitting the step length histogram by considering three components corresponding to an immobile as well as a slow and a fast mobile fraction (Fig. S1). (h) Diffusion properties of cell-bound DY647IFNα2-dn and fit according to a two-component model. (i) Comparison of the step-length histogram for DY647IFNα2-wt and DY647IFNα2-dn. The data shown in g–i are pooled from at least two independent experiments, each with >650 analyzed trajectories (≥15 steps) per IFN mutant. (j) Changes in mobility of a model transmembrane protein dimerized by a monoclonal antibody. The data shown are pooled from eight independent experiments with >400 analyzed trajectories for each experiment (≥15 steps).

Results

Single-molecule IFN binding and diffusion

To probe dimerization of endogenous IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, we developed an in situ IFN binding assay based on single-molecule fluorescence imaging. We have previously demonstrated that the dissociation kinetics of IFNs can be taken as a measure for probing the equilibrium between binary and ternary complexes on artificial membranes (Lamken et al., 2004; Gavutis et al., 2005). The key concept is that IFN simultaneously interacting with IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 dissociates much slower than when interacting with IFNAR2 only. Thus, the effective cell surface binding affinity of IFNα2 to cells expressing IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 is typically 10–20-fold higher (Kd = ∼200 pM) compared with the interaction with IFNAR2 only (Kd = ∼3 nM, see Table S1; Cohen et al., 1995; Moraga et al., 2009). To robustly quantify IFN binding to cell-surface IFNAR, we probed binding of fluorescently labeled IFNα2 wild type (IFNα2-wt) to the cell surface in situ by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM). For this purpose, we used site-specific labeling of IFNα2-wt with DY647 via an N-terminal ybbR-tag (DY647IFNα2-wt). Thus, a high fraction of labeled IFNα2-wt (>90%) with a well-defined 1:1 labeling degree and uncompromised receptor binding was obtained (Waichman et al., 2010). Unspecific IFN binding to the cover slide surface was minimized by coating the glass slides with a protein-repelling poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) polymer brush functionalized with an RGD peptide to promote cell adhesion (PLL-PEG-RGD). When HeLa cells cultured on PLL-PEG-RGD–coated cover slides were incubated with DY647IFNα2-wt at saturating concentrations (2 nM), highly specific binding to the cell surface receptor could be observed on the single-molecule level (Fig. 1 b and Video 1). The majority (∼90%) of detected molecules were continuously diffusing, corroborating binding to cell surface receptors rather than to the cover slide surface (Fig. S1). For cells blocked with unlabeled IFNα2-wt or for U5A cells, which do not express the high-affinity receptor subunit IFNAR2, negligible binding of DY647IFNα2-wt was observed (Fig. 1 c and Fig. S1).

Typical IFN binding assay. Individual DY647IFNα2 bound to endogenous IFNAR in HeLa cells imaged by TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Left: overview of an entire cell. The boundary of the cell is outlined in white. Right: enlarged view taken from the boxed region, with trajectories (≥30 steps) of individual DY647IFNα2 shown in yellow.

Typical IFN binding assay. Individual DY647IFNα2 bound to endogenous IFNAR in HeLa cells imaged by TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Left: overview of an entire cell. The boundary of the cell is outlined in white. Right: enlarged view taken from the boxed region, with trajectories (≥30 steps) of individual DY647IFNα2 shown in yellow.

Under typical acquisition conditions optimized for unambiguous single-molecule detection, no significant bleaching was observed within a standard observation time of several seconds (Fig. 1 d). To confirm observation of individual ligand–receptor complexes rather than receptor clusters, imaging was performed at elevated excitation power, leading exclusively to single-step photobleaching events (Fig. 1, d–f; and Video 2). At a DY647IFNα2-wt concentration sufficient to saturate all binding sites at the cell surface, a mean density of ∼0.55 molecules/µm2 was detected, corresponding to 500–1,000 binding sites per cell, which is in line with the estimated concentrations of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 (François-Newton et al., 2011). While the number of detected molecules on the cell surface remained constant during typical experimental observation times at 25°C, a substantial decrease over time was observed at 37°C, which was ascribed to endocytosis of signaling complexes. To minimize the variability due to changes in cell surface concentrations, all further experiments were performed at 25°C.

Photobleaching of individual IFN molecules. Left: DY647IFNα2-dn bound to endogenous IFNAR in HeLa was imaged by TIRFM at elevated laser power (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Right: photobleaching is shown for raw data and a superimposition of the fluorescence intensity is shown as a 3D kymograph (ImageJ volume rendering).

Photobleaching of individual IFN molecules. Left: DY647IFNα2-dn bound to endogenous IFNAR in HeLa was imaged by TIRFM at elevated laser power (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Right: photobleaching is shown for raw data and a superimposition of the fluorescence intensity is shown as a 3D kymograph (ImageJ volume rendering).

Analysis of single-molecule trajectories revealed heterogeneous diffusion properties of DY647IFNα2-wt bound to the cell surface receptor (Fig. 1 g) with a mean diffusion constant of 0.094 ± 0.011 µm2/s (n = ∼4,000 trajectories), which is typical for a transmembrane receptor in the plasma membrane (Kusumi et al., 2012). The immobile fraction (∼10%) obtained by deconvolution of the step length histogram could be largely ascribed to residual nonspecific binding of DY647IFNα2-wt to the cover slide surface, but also included slow-diffusing molecules (Fig. S1). For more robust analysis of ligand binding and diffusion properties, immobile molecules were identified by a spatio-temporal clustering algorithm (DBSCAN; Sander et al., 1998; Roder et al., 2014) and removed before further analyses. Interestingly, an antagonistic IFNα2-wt variant (IFNα2-dn, for details see Table S1), which binds with 20-fold increased affinity to IFNAR2, but does not recruit IFNAR1 (Pan et al., 2008), showed significantly less heterogeneous diffusion properties (Fig. 1 h) and higher mobility compared with IFNα2-wt (Fig. 1 i), with a mean diffusion constant of 0.126 ± 0.008 µm2/s (n = ∼4,000 trajectories; P < 0.001). A comparable difference in mobility was observed for a model transmembrane protein (maltose-binding protein fused to a transmembrane helix) before and after dimerization by a monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1 j). These findings are in line with ligand-induced receptor dimerization leading to reduced mobility of the receptor subunits.

USP18 interferes with ligand binding to the cell surface receptor

For probing receptor dimerization and its regulation by USP18 via IFN binding assays, we used the IFNα2 mutant M148A, which binds IFNAR2 with ∼50-fold reduced affinity (Kd = ∼150 nM) compared with its wt form (Piehler et al., 2000; compare Table S1). At concentrations most suitable for in situ TIRFM binding assays (2 nM), DY647IFNα2-M148A only binds significantly to the cell surface receptor when simultaneously interacting with both IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, and thus is an indirect marker for ternary complex formation. Compared with DY647IFNα2-wt, ∼60% reduced binding of DY647IFNα2-M148A (∼0.25 molecules/µm2) to HeLa cells was observed (Fig. 2 a), which is in line with the effective cell surface receptor binding affinity of 5–10 nM estimated for this mutant. Single-molecule diffusion analysis (Fig. S1) confirmed a substantially reduced mobility of DY647IFNα2-M148A compared with DY647IFNα2-dn (P < 0.001), supporting efficient ternary complex formation by IFNα2-M148A, which is in line with its capability to fully activate cellular responses (see the last paragraph of the Results section).

The role of USP18 in receptor assembly probed by quantitative ligand-binding assays. (a) Density of DY647IFNα2-M148A, DY647IFNα2-YNS-M148A, and DY647IFNα2-dn (α8tail-R120E) on HeLa cells expressing USP18 and wt HeLa cells in comparison. (b) HeLa cells transiently transfected with EGFP-USP18 (green channel, right) after incubation of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-M148A. For comparison, a nontransfected cell is shown in the same image. (c) Localization density in the presence of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-M148A and DY647IFNα2-dn, respectively, on cells stably transfected with USP18 (HU13) and to parental cells (HLLR1). ***, P > 0.001. (d) Life-time of DY647IFNα2-M128A binding to HLLR1 and HU13 cells, respectively, as obtained by trajectory length analysis. Inset: bleaching control. The curves were obtained from >10 independent experiments with >600 analyzed trajectories (≥5 steps) for HU13 and >1,000 trajectories for HLLR1, respectively. Box plots indicate the data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (closed squares), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range).

The role of USP18 in receptor assembly probed by quantitative ligand-binding assays. (a) Density of DY647IFNα2-M148A, DY647IFNα2-YNS-M148A, and DY647IFNα2-dn (α8tail-R120E) on HeLa cells expressing USP18 and wt HeLa cells in comparison. (b) HeLa cells transiently transfected with EGFP-USP18 (green channel, right) after incubation of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-M148A. For comparison, a nontransfected cell is shown in the same image. (c) Localization density in the presence of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-M148A and DY647IFNα2-dn, respectively, on cells stably transfected with USP18 (HU13) and to parental cells (HLLR1). ***, P > 0.001. (d) Life-time of DY647IFNα2-M128A binding to HLLR1 and HU13 cells, respectively, as obtained by trajectory length analysis. Inset: bleaching control. The curves were obtained from >10 independent experiments with >600 analyzed trajectories (≥5 steps) for HU13 and >1,000 trajectories for HLLR1, respectively. Box plots indicate the data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (closed squares), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range).

Upon expression of USP18, however, binding of DY647IFNα2-M148A to the cell surface was substantially further reduced by ∼80% (Fig. 2, a and b; and Video 3). This effect was confirmed to be independent of the catalytic activity of USP18, as expression of the catalytically inactive mutant C61S induced a comparable decrease in DY647IFNα2-M148A binding (Fig. S1). A similar phenotype was observed for HU13 cells, which stably express USP18 (Fig. 2 c and Fig. S1) and were previously established to study the negative feedback by USP18 (François-Newton et al., 2011). Trajectory length analysis of individual DY647IFNα2-M148A bound to HU13 compared with parental HLLR1 cells moreover confirmed the increased rate of ligand dissociation from the cell surface receptor in the presence of USP18 (Fig. 2 d and Video 4).

The effect of USP18 on IFN binding. Left: imaging of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-M148A–bound HeLa cells transiently overexpressing USP18-EGFP (green channel; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Upon expression of USP18, binding of DY647IFNα2-M148A is strongly impaired. TIRF image acquisition was performed with an Olympus IX71 (150×, NA 1.45).

The effect of USP18 on IFN binding. Left: imaging of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-M148A–bound HeLa cells transiently overexpressing USP18-EGFP (green channel; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Upon expression of USP18, binding of DY647IFNα2-M148A is strongly impaired. TIRF image acquisition was performed with an Olympus IX71 (150×, NA 1.45).

The role of USP18 in IFN interaction dynamics. The lifetime of IFN–receptor complexes was probed in the absence (left) and presence (right) of USP18 by tracking DY647IFNα2-M148A (5 nM) bound to HLLR1 and HU13 cells, respectively, with TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Trajectories with ≥30 steps are shown. HU13 shows significantly fewer bound IFNs and on average a shorter trajectory lifetime. Image acquisition was performed at 0.43 mW of a 647-nm laser to minimize photobleaching.

The role of USP18 in IFN interaction dynamics. The lifetime of IFN–receptor complexes was probed in the absence (left) and presence (right) of USP18 by tracking DY647IFNα2-M148A (5 nM) bound to HLLR1 and HU13 cells, respectively, with TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Trajectories with ≥30 steps are shown. HU13 shows significantly fewer bound IFNs and on average a shorter trajectory lifetime. Image acquisition was performed at 0.43 mW of a 647-nm laser to minimize photobleaching.

USP18 was found to interact with the cytoplasmic domain of IFNAR2 and thus potentially down-regulate cell surface expression or binding affinity of IFNAR2. We therefore quantified binding of DY647IFNα2-dn, which does not interact with IFNAR1, in the presence of USP18. Notably, the binding levels observed for this mutant were not affected by expression of USP18 (Fig. 2, a and c). These observations suggested that rather than affecting the binding affinity to IFNAR2, USP18 affects the ability to recruit IFNAR1 to form a ternary complex. This conclusion was further corroborated by binding assays with DY647IFNα2-M148A-YNS, in which the additional mutations (H57Y, E58N, Q61S) lead to a 50–100-fold increased affinity to IFNAR1 without substantially changing the affinity to IFNAR2 (Kalie et al., 2007; compare Table S1). For this mutant, increased binding was observed in both control cells and USP18-expressing cells (Fig. 2 a). The difference in binding levels was only 40%, suggesting that the enhanced IFNAR1 binding affinity can partially compensate the effect of USP18. These results support a two-step assembly mechanism, in which USP18 regulates ternary complex formation by interfering with the recruitment of IFNAR1 on the cell surface.

Ligand-induced receptor dimerization revealed at the single-molecule level

To directly probe receptor dimerization, IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 were N-terminally fused to the HaloTag and the SNAPf-tag, respectively, for posttranslational labeling with photostable fluorescent dyes, and U5A cells stably expressing HaloTag-IFNAR1 and SNAPf-IFNAR2 at near-physiological level were generated (Fig. S2). The functional properties of these cells with respect to JAK and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) phosphorylation (Fig. 3 a) and STAT1 nuclear translocation (Fig. 3 b) matched those of wt cell lines such as HeLa. Moreover, USP18 expression and its differential negative feedback to IFNα2 and IFNβ signaling with respect to STAT phosphorylation was observed (Fig. 3 a), making these cells a viable system for our mechanistic studies. Upon dual-color single-molecule imaging by TIRFM after labeling with HaloTag tetramethyl rhodamine (TMR) ligand and SNAP-Surface 647, respectively, individual IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 could be clearly discerned (Video 5). A typical density of 1–3 molecules/µm2 was observed, i.e., 2–5-fold higher compared with the endogenous receptor level in HeLa cells estimated by ligand-binding experiments described in the “Single-molecule IFN binding and diffusion” section. Highly specific labeling of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 was confirmed, as <0.04 molecules/µm2 could be detected for nontransfected U5A labeled under the same conditions (Fig. S2).

Simultaneous dual-color single-molecule imaging. HaloTag-IFNAR1 posttranslationally labeled IFNAR1/IFNAR2 (unprocessed raw data;). Halo-IFNAR1 and SNAPf-IFNAR2 stably expressed in U5A cells were labeled with HTL-TMR and SNAPsurfaceDY647, respectively, and imaged by TIRFM using a spectral image splitter (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Large signals are caused by endosomal IFNAR1. TIRF image acquisition was performed with an Olympus IX71 (150×; NA 1.45).

Simultaneous dual-color single-molecule imaging. HaloTag-IFNAR1 posttranslationally labeled IFNAR1/IFNAR2 (unprocessed raw data;). Halo-IFNAR1 and SNAPf-IFNAR2 stably expressed in U5A cells were labeled with HTL-TMR and SNAPsurfaceDY647, respectively, and imaged by TIRFM using a spectral image splitter (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Large signals are caused by endosomal IFNAR1. TIRF image acquisition was performed with an Olympus IX71 (150×; NA 1.45).

Receptor dimerization probed by single-molecule colocomotion analysis. (a and b) Functional properties of U5A cells, which were stably complemented with tagged IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 (U5AIFNAR1/IFNAR2) for posttranslational labeling and single-molecule imaging. (a) Western blot analysis of STAT phosphorylation, USP18 expression, and differential desensitization to IFNα2 and IFNβ. (b) IFN-induced translocation of STAT1-EGFP into the nucleus. (c) IFN-induced receptor dimerization revealed by single-molecule colocomotion experiments. Trajectories (80 frames, ∼2.5 s) of individual TMR-labeled IFNAR1 (red), DY647-labeled IFNAR2 (blue), and co-trajectories (magenta) in the absence and presence of 50 nM IFNα2 are shown. The diagram above indicates the possible different species detected in each channel before (left) and after (right) addition of the ligand, taking unlabeled IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 into account. (d) Formation and dissociation of an individual IFNAR1-IFNAR2 dimer in the presence of IFNα2 as observed by an overlay of the individual trajectories (left) and by a distance analysis (right). Shown is a representative curve from >25 curves analyzed. (e) Relative number of colocomotion trajectories for dual-labeled IFNAR2 (positive control) and noninteracting proteins (negative control), as well as IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, in the absence and presence of IFNα2. The box plot indicates the data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (filled square), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range). (f) Diffusion properties represented as step-length distribution of IFNAR1 (left; from >800 trajectories) and IFNAR2 (right; from >500 trajectories) in the absence and presence of IFNα2. For comparison, the step-length distribution of colocomotion trajectories (+IFNα2) is shown (from ∼100 trajectories).

Receptor dimerization probed by single-molecule colocomotion analysis. (a and b) Functional properties of U5A cells, which were stably complemented with tagged IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 (U5AIFNAR1/IFNAR2) for posttranslational labeling and single-molecule imaging. (a) Western blot analysis of STAT phosphorylation, USP18 expression, and differential desensitization to IFNα2 and IFNβ. (b) IFN-induced translocation of STAT1-EGFP into the nucleus. (c) IFN-induced receptor dimerization revealed by single-molecule colocomotion experiments. Trajectories (80 frames, ∼2.5 s) of individual TMR-labeled IFNAR1 (red), DY647-labeled IFNAR2 (blue), and co-trajectories (magenta) in the absence and presence of 50 nM IFNα2 are shown. The diagram above indicates the possible different species detected in each channel before (left) and after (right) addition of the ligand, taking unlabeled IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 into account. (d) Formation and dissociation of an individual IFNAR1-IFNAR2 dimer in the presence of IFNα2 as observed by an overlay of the individual trajectories (left) and by a distance analysis (right). Shown is a representative curve from >25 curves analyzed. (e) Relative number of colocomotion trajectories for dual-labeled IFNAR2 (positive control) and noninteracting proteins (negative control), as well as IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, in the absence and presence of IFNα2. The box plot indicates the data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (filled square), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range). (f) Diffusion properties represented as step-length distribution of IFNAR1 (left; from >800 trajectories) and IFNAR2 (right; from >500 trajectories) in the absence and presence of IFNα2. For comparison, the step-length distribution of colocomotion trajectories (+IFNα2) is shown (from ∼100 trajectories).

Receptor dimerization was explored by single-molecule tracking and colocomotion analysis (Dunne et al., 2009) as schematically depicted in Fig. S2: individual IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 molecules in each frame were localized beyond the diffraction limit with an average precision of ∼20 nm, and trajectories were obtained by tracking individual molecules over multiple frames. For colocomotion analysis, tracking was performed exclusively with IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 molecules colocalized in each frame within 100 nm for ≥10 consecutive steps (∼300 ms). Thus, stochastic colocalization was effectively eliminated (Ruprecht et al., 2010a), as confirmed by a negative control experiment with noninteracting molecules (Fig. S3 and Video 6). While in the absence of IFN no colocomotion of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 was detectable, strong colocomotion (∼15% with respect to IFNAR2) was observed upon addition of IFNα2-wt at saturating concentrations (Fig. 3, c and e; and Video 7). The formation of individual 1:1 complexes was confirmed by single-molecule bleaching experiments (Video 8). More detailed trajectory analysis revealed the dynamic formation of ternary complexes, as both association and dissociation events of individual complexes could be discerned (Fig. 3 d and Video 9). To correctly quantify the number of dimerized receptors from the fraction of colocomotion events, we used a positive control with both the HaloTag and the SNAPf-tag fused to IFNAR2 (Fig. S3). Under these conditions, ∼20% of the trajectories showed colocomotion (Fig. 3 e), which was taken as a reference for 100% complex formation. Thus, 70–80% of IFNAR2 was recruited into ternary complexes upon stimulation with IFNα2-wt.

Negative and positive controls for colocomotion analysis. Left: as a negative control, SNAPf-MBP-TMD and Halo-MBP-TMD expressed in HeLa cells were labeled with HTL-TMR (red channel) and SNAPsurfaceDY647 (blue channel), respectively, and imaged with dual-color TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Right: as a positive control, HaloTag-SNAPf-IFNAR2 expressed in HeLa cells was labeled with HTL-TMR (red channel) and SNAPsurfaceDY647 (blue channel) and imaged by dual-color TIRFM. Colocomotion trajectories (≥10 steps) are depicted in yellow.

Negative and positive controls for colocomotion analysis. Left: as a negative control, SNAPf-MBP-TMD and Halo-MBP-TMD expressed in HeLa cells were labeled with HTL-TMR (red channel) and SNAPsurfaceDY647 (blue channel), respectively, and imaged with dual-color TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Right: as a positive control, HaloTag-SNAPf-IFNAR2 expressed in HeLa cells was labeled with HTL-TMR (red channel) and SNAPsurfaceDY647 (blue channel) and imaged by dual-color TIRFM. Colocomotion trajectories (≥10 steps) are depicted in yellow.

Receptor dimerization probed by colocomotion analysis. IFNAR1 (labeled with TMR, red signals) and IFNAR2 (labeled with DY647, blue signals) were imaged by TIRFM (Olympus IX71) in the absence (left) and presence (right) of IFNα2 (frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Colocomotion trajectories are indicated in yellow.

Receptor dimerization probed by colocomotion analysis. IFNAR1 (labeled with TMR, red signals) and IFNAR2 (labeled with DY647, blue signals) were imaged by TIRFM (Olympus IX71) in the absence (left) and presence (right) of IFNα2 (frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Colocomotion trajectories are indicated in yellow.

Stoichiometry of individual IFNAR complexes. Single-step bleaching events of two IFN-induced IFNAR1/IFNAR2 dimers (magenta) imaged by TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). For the upper dimer, DY647 (IFNAR2, blue) bleaches first, for the lower dimer, TMR (IFNAR1, red) bleaches first.

Stoichiometry of individual IFNAR complexes. Single-step bleaching events of two IFN-induced IFNAR1/IFNAR2 dimers (magenta) imaged by TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). For the upper dimer, DY647 (IFNAR2, blue) bleaches first, for the lower dimer, TMR (IFNAR1, red) bleaches first.

Dynamics of individual receptor dimers. Assembly, colocomotion, and dissociation of an individual IFNAR1-IFNAR2 dimer measured under steady-state conditions by TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Left: overlay of trajectories (IFNAR1, red; IFNAR2, blue; co-trajectory, magenta). Right: distance between IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 within these trajectories.

Dynamics of individual receptor dimers. Assembly, colocomotion, and dissociation of an individual IFNAR1-IFNAR2 dimer measured under steady-state conditions by TIRFM (Olympus IX71; frame rate, 30 Hz; playback, real time). Left: overlay of trajectories (IFNAR1, red; IFNAR2, blue; co-trajectory, magenta). Right: distance between IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 within these trajectories.

To test the possibility of very transient receptor dimerization, which would not be picked up by the colocomotion assay, we analyzed spatial co-organization of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 by particle image cross-correlation spectroscopy (Semrau et al., 2011; Fig. S3). These studies clearly excluded receptor predimerization or co-organization of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 in the absence of ligand and confirmed efficient dimerization by IFNα2-wt (Fig. S3). Ligand-induced ternary complex assembly could also be detected by analyzing the diffusion properties as shown in Fig. 3 f. For dimerized IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, significantly reduced mobility was observed compared with the subunits in the absence of ligand (Fig. 3 f). These findings corroborate that the reduced mobility observed for DY647IFNα2-wt compared with DY647IFNα2-dn (compare Fig. 1 i) was caused by receptor dimerization. By decomposing the distribution observed for the total population of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 in the presence of IFNα2-wt, a fraction of ∼70% IFNAR2-bound IFNα2-wt in complex with IFNAR1 was estimated. These results support the two-step assembly model depicted in Fig. 1 a, and highlight the relevance of equilibrium between binary (IFN/IFNAR2) and ternary complexes (IFN/IFNAR2/IFNAR1) at physiological receptor levels.

IFNAR1 binding affinity of IFNα2-wt is optimized for efficient ternary complex formation

Based on the colocomotion assay, we systematically explored IFNAR dimerization by different IFN subtypes and mutants with altered binding affinities toward IFNAR1. IFNβ and IFNα2-YNS, which both bind IFNAR1 50–100-fold stronger than IFNα2-wt (compare with Table S1), yielded dimerization levels slightly higher than IFNα2 (Fig. 4 a). By comparison with the maximum level observed in the positive control, ∼85% dimerization can be estimated for IFNβ and IFNα2-YNS, compared with ∼70% dimerization achieved by IFNα2-wt. Importantly, dimerization was independent of signal activation, since a similar level of colocomotion was observed for IFNα2-wt in the presence of a JAK inhibitor. These results suggest that the receptor concentrations substantially exceed the two-dimensional binding equilibrium constant (compare with Fig. 1 a) even in the case of IFNα2-wt. However, upon introducing mutations into IFNα2, which reduce the binding affinity toward IFNAR1 (Roisman et al., 2005; Pan et al., 2008), significantly decreased receptor dimerization could be observed (Fig. 4 a). By using quantitative receptor dimerization experiments on solid-supported membranes in vitro (Gavutis et al., 2005) to determine the relative binding affinities of these mutants (Fig. S4), we established a quantitative affinity–dimerization relationship, as depicted in Fig. 4 b. The sigmoidal shape observed for this correlation is in line with the law of mass action governing the equilibrium between binary and ternary complexes, as depicted in Fig. 1 a. The maximum amplitude of <100% colocomotion observed in this plot could be at least partially explained by endogenous IFNAR1, which further reduces the effective degree of labeling. Based on this affinity–dimerization relationship, we estimated a two-dimensional binding affinity of 0.29 molecules/µm2 for the interaction of IFNAR1 with IFNα2-wt bound to IFNAR2 (Table 1). The of IFNβ is too low to be directly quantified at these receptor surface concentrations, but can be estimated to be 0.005 molecules/µm2 based on the relative IFNAR1 binding affinity. Thus, in contrast to IFNβ, the binding affinity of IFNα2-wt toward IFNAR1 is at the edge in order to still allow efficient ternary complex formation at physiological receptor expression levels.

IFNAR dimerization observed for different IFN subtypes and mutants. (a) Relative number of colocomotion trajectories detected in the absence of ligand, in the presence of wt IFNα2, and in several IFNα2 mutants with increased and decreased binding affinities toward IFNAR1and IFNβ (each 50 nM) and IFNα2-M148A (200 nM). The broken line separates different types of mutants. (b) Affinity–dimerization relationship and plot of the law of mass action for naive and primed cells (data points are mean values taken from d). Dimerization for IFNβ is included as well as for IFNα2-wt under JAK inhibition. (c) Receptor dimerization in U5AIFNAR1/IFNAR2 cells in the absence and presence of 50 nM IFNα2, and after priming and ectopic expression of (EGFP)-USP18. (d) Comparison of colocomotion events for 50 nM IFNα2-wt and mutants observed with naive (red) and primed cells (blue). Box plots indicate the data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (closed squares), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range).

IFNAR dimerization observed for different IFN subtypes and mutants. (a) Relative number of colocomotion trajectories detected in the absence of ligand, in the presence of wt IFNα2, and in several IFNα2 mutants with increased and decreased binding affinities toward IFNAR1and IFNβ (each 50 nM) and IFNα2-M148A (200 nM). The broken line separates different types of mutants. (b) Affinity–dimerization relationship and plot of the law of mass action for naive and primed cells (data points are mean values taken from d). Dimerization for IFNβ is included as well as for IFNα2-wt under JAK inhibition. (c) Receptor dimerization in U5AIFNAR1/IFNAR2 cells in the absence and presence of 50 nM IFNα2, and after priming and ectopic expression of (EGFP)-USP18. (d) Comparison of colocomotion events for 50 nM IFNα2-wt and mutants observed with naive (red) and primed cells (blue). Box plots indicate the data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (closed squares), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range).

IFNAR1/IFNAR2 heterodimer fraction α observed for IFNα2-wt and obtained from the law of mass action

| Experimental conditions | α | a |

| µm−2 | ||

| IFNAR2-fl | 0.89 | 0.29 |

| IFNAR2-fl (primed) | 0.41 | 4.3 |

| IFNAR2 (−Δ346) | 0.84 | 0.46 |

| IFNAR2 (−Δ265) | 0.36 | 5.4 |

| Experimental conditions | α | a |

| µm−2 | ||

| IFNAR2-fl | 0.89 | 0.29 |

| IFNAR2-fl (primed) | 0.41 | 4.3 |

| IFNAR2 (−Δ346) | 0.84 | 0.46 |

| IFNAR2 (−Δ265) | 0.36 | 5.4 |

Calculated from mean experimental receptor concentrations corrected for the degree of labeling (IFNAR1, 3.5 µm

−; IFNAR2, 1.3 µm−2). Experimental error: ±50%.

USP18 modulates receptor dimerization efficiency

Based on this quantitative dimerization assay, we next tested the effect of USP18 on the dimerization efficiency. To obtain reproducible and physiologically relevant levels of USP18 in U5A cells stably transfected with HaloTag-IFNAR1 and SNAPf-IFNAR2, we primed cells with IFN (François-Newton et al., 2011), thus inducing the same phenotype as ectopic USP18 expression (Fig. S5). To ensure efficient washout, we used IFNα2-M148A for priming, which is as able to desensitize cells as IFNα2-wt (Fig. S5). Colocomotion assays in primed cells revealed a substantial decrease in receptor dimerization by IFNα2-wt and all mutants with reduced binding affinity toward IFNAR1 (Fig. 4, c and d). This was also true for cells ectopically expressing USP18 (Fig. 4 c). These observations clearly established that negative feedback via USP18 affects receptor dimerization. In contrast, only minor changes in receptor dimerization by IFNα2-YNS were observed in IFN-primed cells (Fig. 4 d). The quantitative affinity–dimerization relationship obtained in the presence of USP18 is in line with a general shift in the two-dimensional binding affinity (Fig. 4 b). For the interaction of IFNAR1 with IFNα2-wt bound to IFNAR2 in the presence of USP18, a of 4.3 molecules/µm2 was estimated (Table 1), i.e., an ∼15-fold increase compared with the interaction in naive cells. These observations clearly established that USP18 acts by attenuating IFNAR1 recruitment into the ternary complex by reducing the 2D affinity.

Associated JAKs stabilize the ternary complex

USP18 has been shown to bind to the cytosolic domain of IFNAR2 and desensitize cells with respect to STAT phosphorylation, independently of its catalytic activity. We therefore hypothesized that USP18 weakens cytosolic interactions between the receptor subunits, which stabilize the ternary complex. Indeed, reduced receptor dimerization by IFNα2-wt, but not IFNα2-YNS, was observed on cells expressing IFNAR2 −Δ265 that lack the cytosolic domain (Fig. 5 a and Table 1). Moreover, dimerization efficiencies were similar to those measured in the presence of USP18. Because USP18 has been suggested to interfere with Jak1 binding to IFNAR2 (Malakhova et al., 2006), we explored in more detail the role of Jak1 for receptor dimerization. Strikingly, similar dimerization levels were observed for full-length IFNAR2 and for IFNAR2 (−Δ346) that is truncated after the Jak1 binding site (Fig. 5 a), which supports the finding that ternary complex stabilization may be mediated via the JAKs. From the ∼18-fold difference in the in the absence and in the presence of the cytosolic domain of IFNAR2, an energetic contribution of ∼7.1 kJ/mol can be estimated from the interactions between the receptor subunits in the cytosol.

The role of Jak1 in stabilizing the ternary complex. (a) Receptor dimerization by IFNα2 (blue) and IFNα2-YNS (red) for full-length (fl) IFNAR2, IFNAR2 truncated after the Jak1 binding site (Δ346), and after the transmembrane domain (Δ265). (b and c) Binding of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-M148A (b) and DY647IFNα2-dn (c) to cell lines deficient in Jak1 (U4C) and IFNAR2 (U5A). For comparison, binding to the parental cell line (2fTGH) and to U4C complemented with Jak1 is shown. Box plots indicate the data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (closed squares), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range).

The role of Jak1 in stabilizing the ternary complex. (a) Receptor dimerization by IFNα2 (blue) and IFNα2-YNS (red) for full-length (fl) IFNAR2, IFNAR2 truncated after the Jak1 binding site (Δ346), and after the transmembrane domain (Δ265). (b and c) Binding of 2 nM DY647IFNα2-M148A (b) and DY647IFNα2-dn (c) to cell lines deficient in Jak1 (U4C) and IFNAR2 (U5A). For comparison, binding to the parental cell line (2fTGH) and to U4C complemented with Jak1 is shown. Box plots indicate the data distribution of the second and third quartile (box), median (line), mean (closed squares), and whiskers (1.5× interquartile range).

We further investigated the role of Jak1 for receptor dimerization using DY647IFNα2-M148A binding assays in the Jak1-deficient cell line U4C. While binding of IFNα2-M148A was comparable on parental 2fTGH, HeLa, and HLLR1 cells, binding on U4C cells was found to be negligible (Fig. 5 b) but was recovered upon complementation with Jak1. Binding experiments with IFNα2-dn confirmed essentially unaltered expression of IFNAR2 in U4C cells (Fig. 5 c). Overall, these observations strongly suggest that Jak1 association to IFNAR2 further stabilizes the ternary signaling complex and that USP18 interferes with this interaction, e.g., by outcompeting Jak1.

USP18 phenotype can be mimicked by IFNs with reduced IFNAR1 binding affinity

An important consequence of reduced receptor dimerization efficiency upon expression of USP18 would be the loss of functional signaling complexes on the membrane, which cannot be compensated by increasing the ligand concentration in solution. Fewer signaling active complexes would in turn affect the maximal STAT phosphorylation level. We therefore explored the role of receptor dimerization for STAT phosphorylation by performing dose–response assays for different IFNα2 variants in the absence (HLLR1 cells) and presence (HU13 cells) of USP18. As expected, dose–response curves revealed a substantial reduction in the maximum level of STAT phosphorylation (pSTAT1 and pSTAT2) upon ectopic expression of USP18 (Fig. 6). Indeed, the maximum amplitudes of pSTAT1 and pSTAT2 were reduced by ∼75% and ∼50%, respectively, which is in line with the reduced maximum number of ternary complexes formed in the presence of USP18 (compare with Table 1). For IFNα2-R120A, a mutant with ∼60-fold reduced IFNAR1 binding affinity, a similar reduction in the maximum binding amplitude was already observed in the absence of USP18. In contrast, for IFNα2-M148A, with its ∼50-fold reduced binding affinity toward IFNAR2, the same maximum level of STAT phosphorylation as for IFNα2-wt was still obtained, though at higher ligand concentrations. Thus, reduction of IFN affinity toward IFNAR1 mimics the phenotype observed for USP18, corroborating the fact that USP18 regulates IFN signaling on the level of IFNAR1 recruitment.

Functional consequences of USP18-mediated interference with ternary complex assembly. (a and b) Western blot analysis of STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation in parental HLLR1 cells versus cells stably expressing USP18 (HU13) stimulated with IFNα2-wt, -R120A, or -M148A. (c and d) Dose–response curve for pSTAT normalized to total STAT calculated from the band intensities in the Western blot (representative data from three independent experiments). Values were normalized to those obtained at the highest dose of IFN wt, which was taken as 100%. The broken lines represent the curve extrapolations for lower IFN doses expected from independent experiments.

Functional consequences of USP18-mediated interference with ternary complex assembly. (a and b) Western blot analysis of STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation in parental HLLR1 cells versus cells stably expressing USP18 (HU13) stimulated with IFNα2-wt, -R120A, or -M148A. (c and d) Dose–response curve for pSTAT normalized to total STAT calculated from the band intensities in the Western blot (representative data from three independent experiments). Values were normalized to those obtained at the highest dose of IFN wt, which was taken as 100%. The broken lines represent the curve extrapolations for lower IFN doses expected from independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we have attempted to uncover the mechanistic basis of IFN receptor plasticity regulated by the negative feedback inhibitor USP18, which was previously shown to be a key determinant for differential activity of IFNα2 and IFNβ. Because USP18 was shown to affect ligand binding, we focused our studies on the assembly of the IFN signaling complex. During the past decade, the mechanism of cytokine receptor assembly has been a matter of controversy because for several homodimeric class I cytokine receptors, ligand-independent predimerization of the receptor subunits has been demonstrated (Remy et al., 1999; Constantinescu et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2007). A similar mechanism was proposed for heterodimeric class I (Damjanovich et al., 1997; Tenhumberg et al., 2006; Zaks-Zilberman et al., 2008) and class II receptors (Krause et al., 2002, 2006a,b), including the IFN receptor (Krause et al., 2013). Here, we have unambiguously shown that IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 are not preassembled in the plasma membrane of living cells, but are efficiently dimerized upon IFN binding. Revealing this assembly mechanism was made possible by exploiting and optimizing single-molecule fluorescence imaging techniques, which allowed studying receptor assembly at a physiological expression level, an absolutely critical prerequisite, as the rate and affinity constants of IFN–receptor interactions are fine-tuned for receptor concentrations corresponding to only a few hundred copies per cell. Quantitative ligand-binding studies with site-specifically labeled IFNs revealed random and nonclustered distribution of signaling complexes at the cell surface at densities of <1/µm2, which is ideally suitable for single-molecule imaging techniques. While diffusion analysis for mutants with different receptor binding characteristics supported the model of IFN-induced dimerization of the endogenous receptor, dual-color single-molecule imaging was applied to identify the mechanism of receptor assembly. Based on posttranslational labeling of ectopically expressed IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 via fusion proteins with bright and photostable organic fluorescence dyes, we succeeded in monitoring IFN-stimulated dimerization and the formation of ternary complexes, which dynamically form and dissociate in the plasma membrane.

Importantly, preassembly of the receptor subunits could be excluded at these receptor concentrations. In contrast to traditional fluorescent proteins, the HaloTag and the SNAPf-tag are strictly monomeric and thus do not promote dimerization. Previous studies claiming IFNAR predimerization (Krause et al., 2013) may have been biased by the much higher (∼100-fold) receptor expression levels required for conventional fluorescence imaging techniques as well as by the interaction between GFP derivatives used for FRET (Shimozono and Miyawaki, 2008). We could not observe any spatial co-organization of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 in the absence of IFN either, as has been previously suggested for several cytokine receptors (Vámosi et al., 2004; de Bakker et al., 2008; Jenei et al., 2009). This is in line with the observation that IFN signaling is independent of membrane microdomains (Marchetti et al., 2006). Yet, we revealed stabilization of the ternary complex via the associated JAKs, which suggests a productive interaction between Jak1 and Tyk2 in the signaling complex. Such productive contacts have been experimentally demonstrated for the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase domains (Zhang et al., 2006) and have been recently proposed for Jak2 in the growth hormone receptor complex (Brooks et al., 2014). Interestingly, previous studies suggesting receptor predimerization identified a critical role of JAKs in this process (Krause et al., 2013). Yet, the <3 kBT binding energy we found for this interaction is clearly not sufficient for predimerization at physiological receptor expression levels.

Quantitative receptor dimerization studies at physiological expression levels allowed us to assess the role of IFNAR1 binding affinity in receptor assembly. Interestingly, at physiological receptor expression levels, the relatively low IFNAR1 binding affinity of IFNα2 allows ∼50% of IFNAR2-bound IFNα2 to form ternary complexes with IFNAR1 (Table S2). Notably, recruitment of the γc chain by IL-4 bound to its high-affinity receptor subunit has been indirectly shown to yield ∼90% dimerization (Whitty et al., 1998), which is in line with the ∼10-fold lower Kd of the IL-4/γc compared with the IFNα2–IFNAR1 interaction. However, this gives rise to the question of whether the IFNAR1 binding affinity of IFNα2 (and other IFNα subtypes) is optimized to be most sensitive to changes in dimerization efficiency caused by the negative feedback regulator USP18. Here we found that USP18 shifts the equilibrium from the ternary toward the binary complex, probably by interfering with the cytosolic interactions between the receptor subunits, which are related to the associated JAKs. Intriguingly, the 2D affinity for IFNα2-wt observed for feedback inhibition by USP18 in primed cells ( = 4.3 µm−2) reaches very similar levels as in the absence of cytosolic interactions in the case of IFNAR2 −Δ265 ( = 5.4 µm−2). This effect is independent of the catalytic activity of USP18, which suggests that USP18 binding to IFNAR2 (Malakhova et al., 2006; Löchte et al., 2014) directly interferes with complex stabilization via the intracellular domains. Interestingly, USP18 has been proposed to compete with Jak1 association to IFNAR2 (Malakhova et al., 2006), which again points toward a critical role of JAKs in stabilizing the ternary complex.

In the presence of USP18, IFNα subtypes lose their ability to efficiently recruit IFNAR1 into the signaling complexes. As the cell surface equilibrium is shifted toward the binary complex, the effective binding affinity of IFNα2 to the cell surface receptor is reduced due to the increased dissociation kinetics as described in the “Single-molecule IFN binding and diffusion” section, which is in line with the shifted dose–response curve in the presence of USP18. In contrast, the substantially higher IFNAR1 binding affinity of IFNβ still ensures efficient receptor dimerization. This mechanism readily explains how IFNβ can maintain signaling much longer than IFNα2 (François-Newton et al., 2011; Francois-Newton et al., 2012), which can account for its specific activities with respect to cell proliferation and differentiation (Uzé et al., 2007). As the concentration of USP18 is constantly changing after IFN stimulation, fine-tuning of cellular responsiveness against IFN subtypes is achieved. Two important implications of this desensitization mechanism are that (1) it can only partially be compensated by IFN concentrations, as the maximum number of complexes is limited by the IFNAR1 binding affinity; and (2) it can be eluded by an increased receptor cell surface expression. Indeed, differential signaling by IFNα2 and IFNβ has been demonstrated to require relatively low receptor expression levels (Moraga et al., 2009; Levin et al., 2011). Likewise, differential signaling has been increased by further decreasing the IFNAR1 binding affinity of IFNα2, thus yielding an IFN with antiviral, but not antiproliferative, activity (Levin et al., 2014), which can be explained by more efficient signal abrogation by USP18. For other IFNα subtypes, a very similar effect as for IFNα2 can be expected, as they all bind IFNAR1 with similar affinity (Lavoie et al., 2011). Notably, the IFNAR binding properties of IFNα1 are closely mimicked by IFNα2-M148A, which we found here to be highly affected by USP18.

Functional plasticity has emerged as a frequent feature in cytokine signaling, which has been linked to differences in ligand binding affinities and interaction rate constants in several cases, e.g., for the IL-2/IL-15 receptor (Ring et al., 2012), the IL-10 receptor (Yoon et al., 2005, 2012), and the IL-4 receptor (LaPorte et al., 2008; Junttila et al., 2012). The novel mechanistic concept of differential IFNα/β signaling being regulated at the level of receptor assembly may thus provide a general paradigm for cytokine receptor plasticity. Comprehensive understanding of functional receptor plasticity therefore will require characterizing the temporal evolution of signaling and its regulation by spatial and temporal feedback mechanisms in much more detail.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs

Ectopic expression of proteins in human cell lines was done under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promotor using the vector backbones of pSems-26m (Covalys Biosciences) and pDisplay (Invitrogen). Plasmids for expression of IFNAR1 fused to an N-terminal HaloTag (pSems-neo HaloTag-IFNAR1) and IFNAR2c fused to an N-terminal SNAPf-tag (pSems-puro SNAPf-IFNAR2) were generated as follows: the genes of full-length IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, respectively, without the N-terminal signal sequences were inserted into pDisplay (Invitrogen) via BglII and PstI restriction sites. Subsequently, genes coding for the HaloTag and SNAPf-tag, respectively, were inserted via the BglII site. The constructs including the signal sequence of the pDisplay vector (Igκ) were transferred by restriction with EcoRI and NotI into modified versions of pSems-26m (Covalys Biosciences) linking the ORF to a neomycin or puromycin resistance cassette, respectively, via an IRES site. Truncations of the SNAPf-IFNAR2c (after residue no. 265, IFNAR2-Δ265, and after residue no. 346, IFNAR2-Δ346) were cloned by PCR and inserted accordingly. USP18 (a gift from Sylvie Urbé, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, England, UK) N-terminally fused to mEGFP was inserted into pSems via EcoRI and NotI. pSems-puro STAT1-mEGFP was generated by insertion of STAT1 via NotI and EcoRV. A positive control for single-molecule colocalization was cloned by insertion of the fusion construct HaloTag-SNAPf-IFNAR2c into pDisplay by EcoRI and PstI. For negative controls, we used fusion constructs of either HaloTag or SNAPf-tag with maltose-binding protein (MBP) linked to an artificial transmembrane domain K(ALA)7KSSR. SNAPf-MBP-TMD and HaloTag-MBP-TMD were inserted into pSems-neo and pSems-puro via EcoRV and NotI.

Protein expression and purification

IFNα2 and mutants fused to an N-terminal ybbR-tag (Yin et al., 2005; IFNα2, IFNα2-YNS, IFNα2-M148A, IFNα2-YNS-M148A, and IFNα2-α8tail-R120E, “dn”) for site-specific posttranslational labeling were cloned by insertion of an oligonucleotide linker coding for the ybbR peptide (DSLEFIASKLA) into the NdeI restriction site upstream of the corresponding genes in the plasmid pT7T3-U18cis (Piehler and Schreiber, 1999a). Proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli (TG1 strain) at 37°C. After solubilization of inclusion bodies and refolding by dilution with 0.8 M arginine (Kalie et al., 2007), the proteins were purified by anion exchange chromatography (HiTrap Q; GE Healthcare) with an NaCl gradient at pH 8.0, as described previously for wt IFNα2 (Piehler et al., 2000). The proteins labeled with DY 647 (Dyomics) were conjugated to Coenzyme A via enzymatic phosphopantetheinyl-transfer (PPT) using the PPTase Sfp according to published protocols (Yin et al., 2005). After the labeling reaction, IFNs were purified by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75; GE Healthcare) in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl (Hepes-buffered saline [HBS]) as described previously (Waichman et al., 2010). A >90% degree of labeling was obtained for all IFNα2 proteins, as determined by UV/Vis spectroscopy. IFNβ was obtained from D. Baker (Biogen Idec Inc., Cambridge, MA). The extracellular domain of IFNAR1 with a C-terminal decahistidine-tag (IFNAR1-H10) was produced in Sf9 insect cells using a baculoviral expression system. The cDNA of IFNAR1-H10 without secretion sequence was cloned into the vector pACgp67B and was cotransfected with linearized baculovirus DNA (BaculoGOLD; BD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After infection of Sf9 cells, the protein was purified from the supernatant by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (HiTrap Chelating; GE Healthcare) and by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200; GE Healthcare) in HBS buffer (Lamken et al., 2004). IFNAR2-H10 was produced in E. coli and purified by anion exchange chromatography (HiTrap Q; GE Healthcare) and size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75; GE Healthcare) in HBS buffer as described previously (Piehler and Schreiber, 1999a).

Cell culture, transfection, and live cell labeling

Cells were cultivated at 37°C and 5% CO2 in minimum essential medium with Earle’s salts and stable glutamine (Biochrom AG) supplemented with 10% FBS (Biochrom AG), 1% nonessential amino acids (PAA laboratories GmbH M11003), and 1% 2 (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (Hepes) buffer without addition of antibiotics. For minimizing background from nonspecifically adsorbed dye molecules, glass coverslips were coated with a poly-l-lysine (PLL)-graft-(polyethylene glycol) copolymer functionalized with RGD peptide (PLL-PEG-RGD), which was synthesized as described previously in principle (VandeVondele et al., 2003). In brief, 36 mg N-hydroxysuccinimidyl-PEG3000-maleimde (PEG molecular mass: 3,000 g/mol; Rapp Polymere) was mixed with 7.6 mg RGD peptide (Ac-CGRGDS-COOH, custom-synthesized by Coring System Diagnostix) in 0.30 ml HBS buffer (100 mM Hepes buffer with saline, pH 7.5) for 15 min. The reaction solution was immediately added to a solution of 7.5 mg PLL (22.5 kg/mol average molecular mass; Sigma Aldrich) in 0.30 ml HBS buffer. The total 0.6-ml solution was mixed vigorously by shaking for 20 h at room temperature, followed by dialysis against MilliQ water for 48 h using a 10-kD cut-off membrane. After dialysis, the product was lyophilized into white powder and stored at −20°C. Before surface coating, cover slides (24 mm Ø, no. 1, VWR International) were cleaned for 15 min using a plasma cleaner (Femto; Diener electronic). 8 µl of 0.4 mg/ml PLL-PEG-RGD in PBS buffer was sandwiched between two plasma-cleaned cover slides for 1 h. The cover slide was washed with MilliQ water and blow-dried with nitrogen gas. After coating, cover slides were directly used for cell culture or stored at −20°C. Cells were plated on PLL-PEG-RGD-coated cover slides in 35-mm cell culture dishes to a density of ∼40% confluence. Typically, cells were transfected 1 d after seeding via calcium phosphate precipitation as described previously (Muster et al., 2010). After 12 h, cells were washed twice with PBS buffer and media was exchanged. Transiently transfected cells were typically used for ligand binding or colocomotion experiments 24 h after transfection.

U5A cells were stably transfected with HaloTag-IFNAR1 and variants of SNAPf-IFNAR2c (full length, −Δ265 and −Δ346) in two steps: U5A cells were transfected by HaloTag-IFNAR1 via G418 selection. Transfected cells were selected for stable neomycin resistance by cultivation in the presence of 800 µg/ml G418 (EMD Millipore). A cell clone with homogeneous and moderate expression of HaloTag-IFNAR1 was chosen and proliferated. In a second step, SNAPf-IFNAR2c (and truncated versions) was transfected and selected via Puromycin resistance at 0.4 µg/ml (EMD Millipore). HaloTag- and SNAPf-tagged proteins were simultaneously labeled with 30 nM HaloTag TMR Ligand (HTL-TMR; Promega) and 80 nM of SNAP-Surface 647 (BG-DY647; New England Biolabs, Inc.) at 37°C for 15 min. After labeling, cells were washed five times with prewarmed PBS to remove unreacted dye. Labeling, washing, and subsequent imaging were performed in custom-made incubation chambers with a volume of 500 µl. Homodimerization of MBP-tagged transmembrane proteins was induced by monoclonal antibody against MBP (r 29.6: sc-13564; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Single-molecule imaging experiments

Single-molecule imaging experiments were performed by TIRFM with an inverted microscope (IX71; Olympus) equipped with a triple-line total internal reflection illumination condenser (Olympus) and a back-illuminated electron multiplied (EM) CCD camera (iXon DU897D, 512 × 512 pixels; Andor Technology). A 150× magnification objective lens with a numerical aperture of 1.45 (UApochromat 150×/1.45 TIRFM; Olympus) was used for TIRFM.

DY647IFNs was excited by a 642-nm laser diode (Luxx 642–140; Omicron) at 0.65 mW (power output after passage of the objective), and a 690/70 bandpass filter (Chroma Technology Corp.) was used for detection. Stacks of 300 frames were recorded at 32 ms/frame. For dual-color acquisition, TMRHaloTag-IFNAR1 was excited by a 561-nm diode-pumped solid-state laser (CL-561-200; CrystaLaser) at 0.95 mW and DY647SNAPf-IFNAR2 by a 642-nm laser diode (Luxx 642–140; Omicron) at 0.65 mW. Fluorescence was detected using a spectral image splitter (DualView; Optical Insight) with a 640 DCXR dichroic beam splitter (Chroma Technology Corp.) in combination with the band-pass filter 585/40 (Semrock) for detection of TMR and 690/70 (Chroma Technology Corp) for detection of DY647 projecting each channel onto 512 × 256 pixels (Fig. S2). Stacks of 300 images were acquired with a time resolution of 32 ms/frame.

All experiments were performed at room temperature in medium without phenol red supplemented with an oxygen scavenger and a redox-active photoprotectant (0.5 mg/ml glucose oxidase [Sigma-Aldrich], 0.04 mg/ml catalase [Roche], 5% wt/vol glucose, 1 µM ascorbic acid, and 1 µM methyl viologene) to minimize photobleaching (Vogelsang et al., 2008). For quantitative ligand-binding studies, 2 nM DY647IFNα2 in medium without phenol red was incubated for at least 5 min and kept in the bulk solution during the whole experiment to ensure equilibrium binding. Receptor dimerization was probed in the presence of the respective unlabeled IFN at a concentration of 50 nM after incubating for at least 5 min if not stated otherwise.

Single-molecule tracking, colocomotion, and particle image cross-correlation spectroscopy (PICCS) analysis

Single-molecule localization and single-molecule tracking were performed by using the multiple-target tracing (MTT) algorithm. The positions of individual fluorescence emitters were determined with subpixel precision in a two-step process, which was developed for high-density single-particle tracking (Sergé et al., 2008), as described previously in detail (Appelhans et al., 2012). Initial emitter positions were identified using a pixel-wise statistical test limiting the rate of false-positive detection to 10−6 per pixel. These initial positions were refined to subpixel accuracy in a second step by maximum likelihood estimation modeling the microscope’s PSF as a 2D Gaussian profile. From the localization data, single-particle tracking was performed, assuming a maximal expected diffusion coefficient of 0.2 µm2/s. Step-length distributions were obtained from single-molecule trajectories (5 steps, ∼160 ms) and decomposed into diffusive subpopulations by a mixture model of Brownian diffusion. Mean diffusion constants were finally determined by the slope in mean square displacement analysis (2–10 steps).

Before colocalization analysis, both imaging channels were aligned with subpixel precision by using a spatial transformation that corrects for translation, rotation, and scaling. To this end, a transformation matrix was calculated based on a calibration measurement with multicolor fluorescent beads (TetraSpeck microspheres, 0.1 µm; Invitrogen) visible in both spectral channels (cp2tform type “affine”; MATLAB release 2009a; The MathWorks Inc.). Immobile molecules were identified by the density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) algorithm (Sander et al., 1998), which forms clusters of points based on the premise of density reachability established between neighboring points that satisfy a given critical density. DBSCAN achieves this task by exploiting the high spatio-temporal persistency of immobile signals. To capture this specific feature, the density estimate, an integration over the number of points within a specified radius, is expanded to include the temporal domain. We further introduce nonlinear distance weighting in our density estimate, specifically a Gaussian weighting that possesses two scaling parameters, one for the spatial and one for the temporal domain. The spatial scaling factor is determined by the expected localization precision while the temporal scaling factor is set according to the expected lifetime of the immobile emitter. Thereby, detections from immobile particles are effectively raised above the critical density via the contribution of all detections of the same emitter due to temporal reoccurrence within a small spatial distance (Waichman et al., 2013). For comparison of diffusive behavior and for colocomotion analysis, immobile molecules, identified by DBSCAN, were removed from the dataset to increase tracking fidelity.

For single-molecule colocomotion analysis, individual molecules detected in the both spectral channels were regarded as colocalized if found in the same frame within a distance threshold radius of 100 nm. In a consecutive step, colocalized particles were subjected to tracking by the MTT algorithm to generate colocomotion trajectories. For the colocomotion analysis, only trajectories with a minimum of 10 steps (∼300 ms) were considered (Ruprecht et al., 2010b). The fraction of colocomotion trajectories was then determined as the number of colocomotion trajectories with respect to the number of IFNAR trajectories. Typically, the stably transfected cell line U5A IFNAR1+IFNAR2 shows a moderate excess of IFNAR1, so IFNAR2 was regarded as the limiting partner and therefor taken as reference for maximal ternary complex assembly. Receptor dimerization was corrected for the effective degree of labeling (DOL) as determined for HaloTag-SNAPf-IFNAR2c:

The shape of the sigmoidal dimerization-affinity relationship was approximated by a Hill function:

PICCS analysis was performed according to Semrau et al. (2011). The algorithm allows estimating the correlated fraction α of particles in channel A colocalized with particles in channel B:

For randomly distributed particles without a correlated fraction α, Ccum linearly increases with increasing search radius l2, with a slope given by the density of particles in channel B.

Quantification of IFNAR1 binding affinities

The relative binding affinities of the IFNα2 mutants toward IFNAR1 were determined by monitoring ligand dissociation kinetics from IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 tethered onto solid-supported membranes by simultaneous total internal reflection fluorescence spectroscopy and reflectance interference detection in a flow system as described previously in detail (Gavutis et al., 2005, 2006b). All binding experiments were performed in HBS at 25°C. Solid-supported membranes were generated by injection of small unilamellar vesicles, prepared from 250 µM 1,2-2dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine containing 2 mol% Tris-nitrilotriacetic acid steroyloctacylamin (Beutel et al., 2014) by sonication, onto a freshly plasma cleaned transducer slide. The membrane was washed sequentially with HBS, 500 mM imidazole in HBS, and 100 mM EDTA in HBS. Finally, 10 mM NiCl2 in HBS was injected to load the Tris-NTA head groups with Ni2+. 25 nM of the deca-histidine–tagged extracellular part of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 was injected for binding to the solid-supported membrane. After loading the receptors to the membrane, 50 nM Dy647IFNα2 was injected. Subsequently, the dissociation of Dy647IFNα2 from the surface was monitored while rinsing for 300 s with HBS buffer at a flow rate of 10 µl/s. After the experiment, all attached proteins were removed by injecting 500 mM imidazole. The subsequent binding assays were performed on the same lipid bilayer.

Relative binding affinities were determined from the ligand dissociation kinetics, which report on the equilibrium between binary and ternary complexes as detailed previously (Gavutis et al., 2005). To this end, the ligand dissociation curve was fitted numerically by a set of differential equations based on a two-step assembly model using Berkeley Madonna software:

[B] and [T] are the surface concentrations of the binary complexes (IFNAR2/IFN) and the ternary complex, respectively. [R1] and [R2] are the surface concentrations of free IFNAR1-H10 and IFNAR2-H10, respectively. [R1]0 and [R2]0 are the total surface concentrations of IFNAR1-H10 and IFNAR2-H10, respectively. The 2D association rate constant experimentally assessed for IFNα2 wt (Gavutis et al., 2005) was fixed and the 2D dissociation rate constant was fitted for the IFNα2 mutants, keeping all other parameters constant. The 2D equilibrium dissociation constants were calculated from and . The relative 3D affinity toward IFNAR1 was estimated from the relative as both affinities are proportional (Gavutis et al., 2006a).

Calculation of 2D binding equilibrium constant in cells

The 2D equilibrium dissociation constant of IFNAR1 recruitment into the ternary complex (molecules/µm2) was calculated according to the law of mass action:

or

where α is the fraction of IFNAR2-bound IFN in ternary complex with IFNAR1 (assuming [IFNAR1] > [IFNAR2]). Receptor cell surface concentrations in stably transfected U5A cells were determined from single particle localizations (molecules/µm2) of TMRHaloTag-IFNAR1 (0.78 ± 0.19) and DY647SNAPf-IFNAR2c (0.56 ± 0.15). The number of localizations was corrected for the degree of labeling. The degree of labeling was determined as described in the “Single-molecule tracking, colocomotion, and particle image crosscorrelation spectroscopy (PICCS) analysis” section, which resulted in effective cell surface concentrations for IFNAR1 (3.5 µm−2) and IFNAR2 (1.3 µm−2). The correlated fraction α was normalized to the maximum dimerization level (0.89) obtained from the dimerization–affinity relationship.

The calculated was applied to other cell lines with different [IFNAR1/2] to determine α. For HLLR1 and HU13-cells, receptor concentrations were measured by quantitative ligand binding assays:

For 0 ≤ α ≤ 1:

The energetic contribution of the intracellular complex stabilization was calculated from the ratio of the equilibrium binding constants:

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows binding and diffusion properties of DY647IFNα2 mutants to endogenous IFNAR. Fig. S2 shows the specificity of posttranslational labeling of HaloTag-IFNAR1 and SNAPf-IFNAR2 via HTL-TMR and BG-DY647, and includes a schematic flowchart for image acquisition, single-molecule localization, colocomotion, and data evaluation. Fig. S3 shows the quantification of receptor dimerization by colocomotion and by PICCS. Fig. S4 shows the in vitro quantification of IFNα2 binding affinities toward IFNAR1. Fig. S5 shows the desensitization of IFN signaling in HeLa cells upon priming with IFNα2-M148A. Table S1 summarizes the binding affinities of IFNs used in this study. Table S2 shows the calculation of dimerization fraction α and according to the law of mass action. Table S3 summarizes affinities of IFNs toward IFNAR1 as obtained in vitro. Video 1 shows imaging of individual DY647IFNα2 bound to endogenous IFNAR in HeLa cells. Video 2 shows single-step bleaching of DY647IFNα2-dn bound to endogenous IFNAR on HeLa. Video 3 shows Imaging of DY647IFNα2-M148A bound to a HeLa cell transiently overexpressing USP18-EGFP compared with a control cell. Video 4 shows interaction dynamics of DY647IFNα2-M148A on HLLR1 and HU13 quantified by single-molecule tracking. Video 5 shows simultaneous dual-color imaging of posttranslationally labeled HaloTag-IFNAR1 and SNAPf-IFNAR2. Video 6 shows negative and positive controls for the colocomotion analysis. Video 7 shows colocomotion of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 in the absence and presence of IFNα2. Video 8 shows the single-step bleaching events of two IFN-induced IFNAR1/IFNAR2 dimers. Video 9 shows assembly, colocomotion, and dissociation of an individual signaling complex.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriele Hikade and Hella Kenneweg (University of Osnabrück) for technical support, Domenik Lisse (University of Osnabrück) for technical advice concerning HaloTag labeling, Rainer Kurre (Center for Advanced Light Microscopy Osnabrück) for support with fluorescence microscopy, Darren Baker (Biogen Idec) Inc. for providing IFNβ, and Ignacio Moraga (Stanford University) for graphic material.

This project was supported by funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Sonderforschungsbereich 944) to J. Piehler and by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 223608 (IFNaction) to J. Piehler, S. Pellegrini, and G. Uzé. S. Pellegrini was supported by Institut Pasteur, Centre National pour la Recherche Scientifique, and Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. V. Francois-Newton was supported by the Ligue contre le Cancer.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- HBS

Hepes-buffered saline

- HTL

HaloTag ligand

- IFN

type I interferon

- IFNAR

type I interferon receptor

- JAK

Janus kinase

- MBP

maltose-binding protein

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PICCS

particle image cross-correlation spectroscopy

- PLL

poly-l-lysine

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TIRFM

total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy

- TMR

tetramethyl rhodamine

- USP

ubiquitin-specific protease

- wt

wild type