The large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (BKCa) channel of smooth muscle is unusually sensitive to Ca2+ as compared with the BKCa channels of brain and skeletal muscle. This is due to the tissue-specific expression of the BKCa auxiliary subunit β1, whose presence dramatically increases both the potency and efficacy of Ca2+ in promoting channel opening. β1 contains no Ca2+ binding sites of its own, and thus the mechanism by which it increases the BKCa channel's Ca2+ sensitivity has been of some interest. Previously, we demonstrated that β1 stabilizes voltage sensor activation, such that activation occurs at more negative voltages with β1 present. This decreases the work that Ca2+ must do to open the channel and thereby increases the channel's apparent Ca2+ affinity without altering the real affinities of the channel's Ca2+ binding sites. To explain the full effect of β1 on the channel's Ca2+ sensitivity, however, we also proposed that there must be effects of β1 on Ca2+ binding. Here, to test this hypothesis, we have used high-resolution Ca2+ dose–response curves together with binding site–specific mutations to measure the effects of β1 on Ca2+ binding. We find that coexpression of β1 alters Ca2+ binding at both of the BKCa channel's two types of high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites, primarily increasing the affinity of the RCK1 sites when the channel is open and decreasing the affinity of the Ca2+ bowl sites when the channel is closed. Both of these modifications increase the difference in affinity between open and closed, such that Ca2+ binding at either site has a larger effect on channel opening when β1 is present.

INTRODUCTION

Large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (BKCa) channels are crucial for the regulation of arterial tone, where they facilitate a negative feedback mechanism that opposes vasoconstriction (Nelson et al., 1995; Nelson and Quayle, 1995; Brenner et al., 2000). Intravascular pressure increases arterial tone by a complex process that includes membrane depolarization and the subsequent elevation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ via voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. This global increase in Ca2+ leads to vasoconstriction, but it also triggers localized Ca2+ release events from ryanodine receptors on the smooth muscle sacroplasmic reticulum. These release events, termed Ca2+ sparks, activate nearby BKCa channels that then create a hyperpolarizing K+ current known as a STOC. STOCs then oppose further constriction (Nelson et al., 1995; Perez et al., 1999). The BKCa channel's accessory β1 subunit has been show to be critically important in this regulatory process, as mice that lack β1 have greatly reduced STOCs in response to sparks as well as hypercontractile smooth muscle and hypertension (Brenner et al., 2000; Pluger et al., 2000). In heterologous expression systems β1 subunits, four of which assemble with a single channel (Shen et al., 1994), make the BKCa channel substantially more Ca2+ sensitive (McManus et al., 1995; Meera et al., 1996; Cox and Aldrich, 2000a). Thus, in the absence of β1 it appears that BKCa channels lack the Ca2+ sensitivity required for BKCa-mediated feedback regulation of smooth muscle tone.

The mechanism by which β1 enhances the BKCa channel's Ca2+ sensitivity has been the subject of many studies (Wallner et al., 1996; Nimigean and Magleby, 1999b, 2000; Cox and Aldrich, 2000b; Qian et al., 2002; Qian and Magleby, 2003; Bao and Cox, 2005; Orio and Latorre, 2005; Morrow et al., 2006; Orio et al., 2006; Wang and Brenner, 2006; Yang et al., 2008), but it is still unclear. Nimigean and Magleby (1999a,b, 2000) found that β1 increases the length of time that the BKCa channel spends in bursting states and that this effect persists in the absence of Ca2+ (Nimigean and Magleby, 1999a). They suggested that a Ca2+-independent effect underlies most of the channel's increased Ca2+ sensitivity. In support of this notion, Bao and Cox (2005) found, when studying gating currents, that β1 stabilizes voltage sensor activation such that activation occurs at more negative voltages with β1 present. At most voltages this decreases the work that Ca2+ must do to open the channel and thereby increases the channel's apparent Ca2+ affinity. However, to account for the full change in Ca2+ sensitivity brought about by β1, Bao and Cox (2005) also proposed that β1 alters the true affinities of the channel's high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites (Bao et al., 2004), a conclusion supported by the earlier study of Cox and Aldrich (2000).

A recent paper by Yang et al. (2008), however, suggests that this may not be the case. Their experiments revealed that mutation of the voltage sensor residue R167 eliminates the ability of β1 to enhance the BKCa channel's Ca2+ sensitivity, implying that β1 enhances Ca2+ sensitivity solely by altering the conformation or movements of the voltage sensor. Here, to clarify this issue, we have used high-resolution Ca2+ dose–response curves to determine directly whether or not β1 alters the BKCa channel's affinity for Ca2+ at either of its two types of high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites. We find effects of β1 on the real affinities of both sites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Heterologous Expression of BKCa Channels in TSA 201 Cells

TSA 201 cells (modified human embryonic kidney cells) were transiently transfected with expression vectors (pcDNA 3; Invitrogen) encoding the mouse α subunit (mslo-mbr5) (Butler et al., 1993), the mouse β1 subunit of the BKCa channel, enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP-N1; BD), and the empty pcDNA 3.1+ vector (Invitrogen) to control for the total amount of transfected DNA. Cells were transiently transfected using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). The eGFP was used to monitor successfully transfected cells. For transfection, cells at 80–90% confluence in 35-mm falcon dishes were incubated with a mixture of the plasmids (total of 4 μg DNA) Lipofectamine and Optimem (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the mixture was left on the cells 4–8 h after which the cells were replated into recording Falcon 3004 dishes in standard tissue culture media: DMEM with 1% fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (all from Invitrogen). The cells were patch clamped 1–3 d after transfection.

The molar ratio of β1 to α-expressing plasmids transfected was 1 β1 plasmid to between 0.6 and 2 α plasmids for all experiments. These ratios were determined to be well above that required to maximize the effects of β1 on channel gating in experiments in which the relative amount of β1 to α plasmid was titrated until no further effect of β1 was observed. The minimal saturating ratio was determined to be 1 β1 plasmid to 6.8 α plasmids, as determined by the magnitudes of β1-induced G-V shifts at 100 µM [Ca2+]. This is likely due to more efficient transcription and or translation of β1 relative to the much larger α subunit.

Electrophysiology

All recordings were done in the inside-out patch clamp configuration (Hamill et al., 1981). Patch pipettes were made of borosilicate glass (VWR micropipettes) with 0.8–5-MΩ resistances that were varied for different recording purposes. The tips of the patch pipettes were coated with sticky wax (KerrLab) and fire polished. Data were acquired using an Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier and a Macintosh-based computer system equipped with an ITC-16 hardware interface and Pulse acquisition software (HEKA). For macroscopic current recordings, data were sampled at 50 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz. In most macroscopic current recordings, capacity and leak current were subtracted using a P/5 subtraction protocol with a holding potential of −120 mV and leak pulses in opposite polarity to the test pulse, but with BKCa currents recorded with >100 µM Ca2+, no leak subtraction was performed. Unitary–current recordings acquired at 0 mV were sampled at 100 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. All experiments were performed at room temperature, 22–24°C.

Solutions

The pipette solution for macroscopic current recordings contained the following (in mM): 118 KMeSO3, 20 N-methyl-glucamine-MeSO3, 2 KCl, 2 MgCl2, and 2 HEPES, pH 7.20. The pipette solution for current recordings at 0 mV contained the following (in mM): 3 KMeSO3, 135 N-methyl-glucamine-MeSO4, 2 KCl, 2 MgCl2, and 2 HEPES, pH 7.20. 10 µM GdCl3 was added to both pipette solutions to block endogenous stretch-activated channels (Yang and Sachs, 1989; Qian and Magleby, 2003). The bath solution for all recordings contained the following (in mM): 118 KMeSO3, 20 N-methyl-glucamine-MeSO3, 2 KCl, and 2 HEPES, pH 7.20. 1 mM EGTA (Fluka) was used as the Ca2+ buffer for solutions containing 3–500 nM free [Ca2+], 1 mM HEDTA (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the Ca2+ buffer for solutions containing 0.8–20 µM free [Ca2+], and no Ca2+ chelator was used as the Ca2+ buffer in solutions containing between 20 µM and 2.5 mM free Ca2+. 50 µM (+)-18-crown-6-tetracarboxylic acid (18C6TA) was added to all internal solutions to prevent contaminant Ba2+ block at high voltages. Both internal and external solutions were brought to pH 7.20.

The appropriate amount of total Ca2+ (100 mM CaCl2 standard solution; Orion Research, Inc.) to add to the buffered solutions to yield the desired approximate free Ca2+ concentrations of 3 nM to 2.5 mM was calculated using the program MaxChelator (see Online supplemental material below), and the solutions were prepared as described previously (Bao et al., 2002). The Ca2+ concentrations reported above were determined with an Orion Ca2+-sensitive electrode. The solutions bathing the intracellular side of the patch were changed by means of a DAD valve controlled pressurized superfusion system (ALA Scientific Instruments).

Data Analysis

All data analysis was performed with Igor Pro graphing and curve-fitting software (WaveMetrics, Inc.), and the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm was used to perform nonlinear least-square curve fitting. Values in the text are given ± the standard error of the mean.

Conductance–Voltage (G-V) Curves

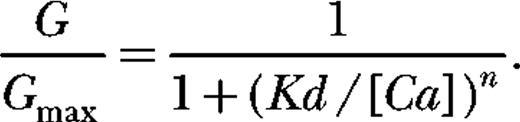

G-V relations were determined from the amplitude of tail currents measured 200 µs after repolarizations to −80 mV following voltage steps to the test voltage. Each G-V relation was fitted with a Boltzmann function,

and normalized to the maximum of the fit.

Single-channel Analysis

Under conditions where the open probability (Popen) is small (<10−2), single-channel openings were observed in patches containing hundreds of channels and IK was measured from steady-state recordings 30 s in duration. NPopen was determined from all-points histograms by measuring the fraction of time spent (PK) at each open level (k) using a half-amplitude criteria and summing their contributions NPopen = Σ kPK, where N is the number of channels in the patch.

Popen versus Ca2+ Curves

The effect of Ca2+ on Popen was determined from the ratio of NPopen at a given [Ca2+] to NPopen at 0.88 or 5.4 µM Ca2+ for all [Ca2+] tested on a given patch. In the presence of β1, the range of total activity per patch obtained over the range of [Ca2+] tested (3 nM to 2.5 mM) was greater than could be covered with a single normalization point. Therefore, in patches with many channels from which we were most interested in making low Popen measurements, the NPopen data at each [Ca2+] was normalized by the NPopen value measured at 0.88 µM [Ca2+]. Such curves were then averaged. Likewise, in patches with fewer channels, from which we were most interested in making higher Popen measurements, the NPopen data at each [Ca2+] was normalized by the NPopen value measured at 5.4 µM [Ca2+], and these curves were then averaged. The curve normalized to 0.88 µM was then adjusted so as to have the same value at 0.88 µM [Ca2+] as the curve normalized to 5.4 µM [Ca2+]. To yield a single curve at the [Ca2+] at which the two curves overlapped, the two values present were subjected to a weighted average, weighted by the number of measurements in each of the two curves being brought together. This yielded a Ca2+ dose–response curve with a value of 1 at 5.4 µM. This curve was then rescaled vertically so that the bottom of the curve equaled 1, or 0 on a log scale. This final curve we plotted as (NPopen/NPopenmin).

In some cases, Popen rather than (NPopen/NPopenmin) was reported as a function of [Ca2+]. This was done by determining Popen for each channel type at a single [Ca2+] in separate experiments, and then adjusting the average log (NPopen/NPopenmin) versus log [Ca2+] curve vertically, such that Popen was correct at the [Ca2+] at which Popen was known. This Popen, used for calibration, was determined at 2.5 mM [Ca2+] from patches whose channel content was apparent (n = 1–4).

Online Supplemental Material

The amount of Ca2+ to add to internal solutions to yield the desired free Ca2+ concentrations was calculated using the program MaxChelator, which was downloaded from http://www.stanford.edu/∼cpatton/maxc.html and is included as executable files.

RESULTS

Steady-state Effects of β1

The BKCa channel is both Ca2+ and voltage sensitive, and the effects of these stimuli are often displayed as a series of G-V relations determined over a series of Ca2+ concentrations. Such a series, determined from current families recorded from BKCa channels expressed in TSA 201 cells, is shown in Fig. 1 C. Representative data used to construct such a series are shown in Fig. 1 A. The data are from an excised inside-out macropatch expressing the mouse BKCa α subunit (mSlo1). Increasing intracellular Ca2+ shifts the channels' G-V curve leftward, an effect that is generally known to be due to three types of Ca2+ binding sites, two of high affinity and one of low affinity (Schreiber and Salkoff, 1997; Bian et al., 2001; Bao et al., 2002, 2004; Shi et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002). The channels in these patches, however, contained the mutation E399N, which eliminates low-affinity Ca2+ sensing (Shi et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002). So here only the effects of Ca2+ binding at the channel's high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites are evident. We refer to the mSlo1 channel carrying this mutation as ΔE. Increasing Ca2+ from 3 nM to 2.5 mM shifts the ΔE G-V relation ∼200 mV leftward.

When the mouse BKCa β1 subunit is expressed with the α subunit (see currents in Fig. 1 B), the Ca2+-induced leftward shifting evident in Fig. 1 C becomes more pronounced (Fig. 1 D), and thus it may be said that β1 increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of the BKCa channel in that it increases its G-V shift in response to a given change in [Ca2+] (McManus et al., 1995). On a plot of half-maximal activation voltage (V1/2) versus [Ca2+], this effect is seen as an increase in slope (Fig. 1 E). At a single membrane voltage, 0 mV for example, it appears as an increase in both the efficacy and the apparent affinity of the channel for Ca2+ (Fig. 1 F). These data reveal that Ca2+ binding to the BKCa channel's low-affinity Ca2+ binding sites (eliminated by the E399N mutation) is not required for β1's effects on Ca2+ sensing. β1 has similar effects on the ΔE channel as it does on wild-type mSlo1 (McManus et al., 1995; Cox and Aldrich, 2000a; Bao and Cox, 2005).

Estimating the Affinities of Each Binding Site with and without β1

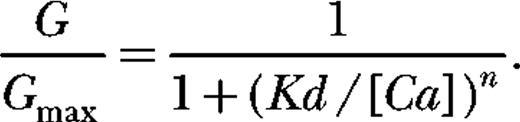

In a previous study we found that much of β1's effects on Ca2+ sensing are due to its effects on voltage sensor movement, but to completely account for our data, we suggested that β1 also has effects on Ca2+ binding (Bao and Cox, 2005). Here, to test this hypothesis we sought to estimate the channel's Ca2+ dissociation constants at each high-affinity Ca2+ binding site in the presence and absence of β1. To do this we used high-resolution Ca2+ dose–response curves (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; Sweet and Cox, 2008). The channel's Popen was measured at a single voltage over a large range of [Ca2+]. Fig. 2 (A and B) shows unitary currents recorded from membrane patches expressing either ΔE or ΔE + β1. Both patches were held at 0 mV and exposed to a range of [Ca2+]. Although each patch contained many channels, Popen was low at 3 nM [Ca2+], such that activity was observed as the infrequent and brief openings of single channels. Increasing intracellular Ca2+ then caused an increase in Popen. From data like these we derived the ΔE and ΔE + β1 channels' Popen versus [Ca2+] relations (Fig. 2 C). So that all parts of each curve could be well determined, Popen was measured over seven orders of magnitude with 21 Ca2+ concentrations. To do this, many patches were used and normalized by their values of NPopen at 5.3 µM, where N is the number of channels in a given patch. The resulting curve was then either normalized to its minimum to yield curves like those in Fig. 3 C or adjusted so as to have the proper Popen at 2.5 mM [Ca2+] (determined in separate single-channel experiments; see Materials and methods). This yielded curves like those in Fig. 2 D.

β1 increases the Ca2+ dependence of Popen at a constant voltage. (A and B) Outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔE channels (A) or ΔE + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relations for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is show. Each point represents the average of between 7 and 30 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM. The Popen curves are fitted with Eq. 1 yielding values of: ΔE, KC1 = 4.3 µM, KO1 = 1.1 µM, KC2 = 7.9 µM, KO2 = 1.3 µM, M = 4.7 × 10−6; ΔE + β1, KC1 = 2.2 µM, KO1 = 0.5 µM, KC2 = 32 µM, KO2 = 0.6 µM, M = 2.0 × 10−8. Additionally, ΔE was fitted assuming that the two types of binding sites are equivalent. The fit yield values of KC = 5.9 µM, KO = 1.2 µM, and M = 4.2 × 10−6.

β1 increases the Ca2+ dependence of Popen at a constant voltage. (A and B) Outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔE channels (A) or ΔE + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relations for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is show. Each point represents the average of between 7 and 30 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM. The Popen curves are fitted with Eq. 1 yielding values of: ΔE, KC1 = 4.3 µM, KO1 = 1.1 µM, KC2 = 7.9 µM, KO2 = 1.3 µM, M = 4.7 × 10−6; ΔE + β1, KC1 = 2.2 µM, KO1 = 0.5 µM, KC2 = 32 µM, KO2 = 0.6 µM, M = 2.0 × 10−8. Additionally, ΔE was fitted assuming that the two types of binding sites are equivalent. The fit yield values of KC = 5.9 µM, KO = 1.2 µM, and M = 4.2 × 10−6.

Mutating all three types of Ca2+ binding sites eliminates the Ca2+ dependence of Popen. Dose–response relationships for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV were obtained by plotting the mean log ratio of NPopen in the presence and absence of Ca2+ for ΔEΔRΔB (open circles) and ΔEΔRΔB + β1 (filled circles) channels. Each point represents the average between 7 and 11 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.

Mutating all three types of Ca2+ binding sites eliminates the Ca2+ dependence of Popen. Dose–response relationships for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV were obtained by plotting the mean log ratio of NPopen in the presence and absence of Ca2+ for ΔEΔRΔB (open circles) and ΔEΔRΔB + β1 (filled circles) channels. Each point represents the average between 7 and 11 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.

Fig. 2 C shows a comparison of the Popen/Popenmin versus [Ca2+] relations at 0 mV of the ΔE channel in the presence (filled circles) and absence (open circles) of β1. The magnitude of the change in Popen induced by Ca2+ (the range the data spans on the ordinate) is ∼100-fold larger for the ΔE + β1 channel than it is for the ΔE channel. This magnitude is determined by the energy Ca2+ binding imparts to the channel's central closed-to-open conformational change, which in turn is determined by the open- and closed-state Ca2+ binding affinities of each binding site. Thus, that this magnitude changes with β1 coexpression indicates that β1 alters Ca2+ binding.

To analyze this effect more rigorously, Popen versus [Ca2+] relations were determined for the ΔE (open circles) and ΔE + β1 (filled circles) channels (Fig. 2 D), and these data were then analyzed as follows. If one assumes that there are four of each type of Ca2+ binding site and that each site influences channel opening by altering the equilibrium constant of a single conformational change between closed and open—as much evidence suggests (McManus and Magleby, 1991; Cox et al., 1997; Cui et al., 1997; Horrigan et al., 1999; Horrigan and Aldrich, 1999, 2002; Rothberg and Magleby, 1999, 2000; Cox and Aldrich, 2000a)—and that there are no interactions between binding sites and no interactions between binding sites and voltage sensors (not rigorously true [Sweet and Cox, 2008], but see below), then at constant voltage the channel's Popen as a function of voltage can be written as

where KC1 and KC2 represent the dissociation constants of binding sites 1 and 2 in the closed conformation, KO1 and KO2 represent the dissociation constants of binding sites 1 and 2 in the open conformation, and M represents the closed-to-open equilibrium constant when no Ca2+ are bound. As relates to the BKCa channel, M is voltage dependent and incorporates all effects of voltage on opening.

In the absence of Ca2+, Eq. 1 reduces to:

which can be rearranged to

Further, at voltages where Popen is much less than 1 (∼10−2 or lower, such as 0 mV, which we have used here), Eq. 3 may be simplified to

Thus, in the absence of Ca2+, M can be determined directly from Popen.

Conversely, at saturating Ca2+, Eq. 1 reduces to

where

and

and, therefore, the top of the Popen versus [Ca2+] curve is determined by M and the ratios (C1 and C2) of the open- and closed-state Ca2+ dissociation constants at the two types of sites.

The ΔE channel's Popen versus [Ca2+] curve at 0 mV (Fig. 2 D, open circles) was fitted with Eq. 1 (solid line). The fit yielded the following values:

Note the large standard errors of the dissociation constants. This suggests that the fit is not unique and that the RCK1 and Ca2+ bowl sites likely have similar affinities at 0 mV, such that changes in the parameters governing one site can be compensated for by changes in the parameters governing the other site. Indeed, the fit was almost as good when we supposed that the two types of sites had identical binding properties (gray curve).

Also shown in Fig. 2 D is the Popen versus [Ca2+] curve we determined for the ΔE channel in the presence of β1. β1 reduces M by 235-fold, which moves the 0 [Ca2+] data point well down the ordinate. This indicates that some of β1's effects are on channel properties that are unrelated to Ca2+ binding, as has been demonstrated (Nimigean and Magleby, 1999b, 2000; Bao and Cox, 2005; Orio and Latorre, 2005; Wang and Brenner, 2006). Fitting this curve with Eq. 1 yielded:

The fit is better determined than the fit to the ΔE (α only) curve, and it suggests that in addition to decreasing M ∼200-fold, β1 increases the affinity of both binding sites when the channel is open, and it reduces the affinity of one site when the channel is closed. This increases C at both sites and thereby the effect of Ca2+ binding on channel opening.

β1 Does not Restore Ca2+ Sensing to Triple Mutant Channels

To test more directly whether β1 affects Ca2+ binding, and if so, at which sites and to what extent, we examined β1's effects on each type of binding site individually using mutations that selectively eliminate the effect of Ca2+ at each type of site. D367A eliminates Ca2+ sensing via RCK1 sites (Xia et al., 2002), and D898A/D900A eliminates Ca2+ sensing via Ca2+ bowls (Bao et al., 2004). Before using these mutations, however, it was important to confirm that in conjunction with E399N, they completely eliminate the effect of Ca2+ on Popen. Shown in Fig. 3 are Ca2+ dose–response relations at 0 mV determined from a patch expressing the triple mutant (E399N)(D367A)(D898A/D900A), which we refer to as ΔEΔRΔB, in the presence and absence of β1. As is evident, the triple mutant shows no response to Ca2+, which demonstrates that the three sites targeted by these mutations can together account for all Ca2+ sensing. Importantly, ΔEΔRΔB + β1 also shows no response to Ca2+. Thus, in our hands, β1 does not restore the Ca2+ sensitivity of one or more of the sites, as has been suggested (Qian and Magleby, 2003), nor does β1 contain Ca2+ binding sites of its own that are coupled to channel opening.

β1 Alters the Affinity of the Ca2+ Bowl Site

We then used the mutant (E399N)(D367A), which we refer to as ΔEΔR, to examine β1's effect on Ca2+ sensing at the Ca2+ bowl. Fig. 4 displays BKCa currents from individual patches expressing ΔEΔR in the absence (A) or presence (B) of β1. Each patch was held at 0 mV and exposed to various [Ca2+]. For the ΔEΔR channels, application of Ca2+ caused an increase in Popen, but the increase was not as great (∼102-fold) as it was with the ΔE channel (∼105-fold), likely because the ΔR mutation eliminates half of the channels high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites. But more importantly, expression of β1 increased the Ca2+ dependence of Popen for the ΔEΔR channels. Fig. 4 C shows a comparison of the Popen/Popenmin versus [Ca2+] relations for the ΔEΔR channel in the presence (filled circles) and absence (open circles) of β1 at 0 mV. Remarkably, for the ΔEΔR channel, the change in Popen produced by saturating Ca2+ is ∼50 times larger in the presence of β1 than it is in its absence. This indicates that β1 increases C at the Ca2+ bowl site and therefore that it affects Ca2+ binding at this site.

β1 alters the affinity of the Ca2+ bowl at constant voltage. (A and B) outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔEΔR channels (A) or ΔEΔR + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relation for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is plotted in C as the ratio of NPopen to NPopenmin versus [Ca2+] and in D as Popen versus [Ca2+]. Each point represents the average of between 8 and 16 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.

β1 alters the affinity of the Ca2+ bowl at constant voltage. (A and B) outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔEΔR channels (A) or ΔEΔR + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relation for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is plotted in C as the ratio of NPopen to NPopenmin versus [Ca2+] and in D as Popen versus [Ca2+]. Each point represents the average of between 8 and 16 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.

To determine the extent to which β1 affects Ca2+ binding, in Fig. 4 D, the Popen versus [Ca2+] relations for the ΔEΔR channels (open circles) and ΔEΔR + β1 channels (filled circles) are plotted. These data are the same as those in Fig. 4 C, except they have been plotted as absolute Popen. The affinities of the intact Ca2+ bowl site in the presence and absence of β1 were then determined from fits with Eq. 8 below, which is analogous to Eq. 1, but represents the case where there is only one type of Ca2+ binding site.

Importantly, the bottom of the curve is still determined by M, but once M is specified, the top of the curve is determined only by C. That is, at saturating Ca2+,

where

.

Thus, when there is a single type of binding site, determining the top and bottom of the channel's Popen versus [Ca2+] curve greatly constrains the fitting. In fact, in leaves only one parameter free, either of the two dissociation constants, to determine the shape of the curve.

Fitting the ΔEΔR channel's Popen versus [Ca2+] curve yielded the fit shown in Fig. 4 D (solid line). Gratifyingly, even with these constraints the fit closely approximated the data and yielded the following parameters (see also Table I):

Next, we fitted the ΔEΔR + β1 curve (Fig. 4 D, dashed line), and again the fit appeared to well approximate the data. This suggests that β1 does not likely alter the assumptions underlying Eq. 8: a single conformational change between opened and closed; four binding sites; and binding at one site does not affect binding at the other sites, except via promoting opening. The fit yielded the following parameter values:

Ca2+ Binding Parameters

| Binding site | Membrane potential (mV) | KC (µM) | KO (µM) | M × 10−6 | C (KC/KO) |

| Ca2+ bowl (ΔEΔR) | |||||

| α | 0 | 2.1 ± 0.28 | 0.55 ± 0.08 | 2.8 ± 5.3 | 3.8 |

| α+β1 | 0 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 0.70 ± 0.13 | 2.2 ± 8.8 | 8.4 |

| RCK1 (ΔEΔB) | |||||

| α | 0 | 15.8 ± 3.1 | 2.10 ± 0.40 | 18 ± 4.5 | 7.5 |

| α+β1 | 0 | 18.5 ± 4.4 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 36 |

| Binding site | Membrane potential (mV) | KC (µM) | KO (µM) | M × 10−6 | C (KC/KO) |

| Ca2+ bowl (ΔEΔR) | |||||

| α | 0 | 2.1 ± 0.28 | 0.55 ± 0.08 | 2.8 ± 5.3 | 3.8 |

| α+β1 | 0 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 0.70 ± 0.13 | 2.2 ± 8.8 | 8.4 |

| RCK1 (ΔEΔB) | |||||

| α | 0 | 15.8 ± 3.1 | 2.10 ± 0.40 | 18 ± 4.5 | 7.5 |

| α+β1 | 0 | 18.5 ± 4.4 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 36 |

Note that the fit is well constrained and suggests that β1 reduces the affinity of the Ca2+ bowl site for Ca2+ both in the opened and the closed channel. The effect on KO however is smaller than on KC and not clearly significant. The effect on KC, however, is large (2.8-fold), and it is predominately this change that increases C for this site and accounts for the expanded Popen range spanned by the ΔEΔR channel's Ca2+ dose–response relation in the presence of β1.

Thus, β1 does alter Ca2+ binding at the Ca2+ bowl site. It lowers the Ca2+ bowl's affinity when the channel is closed. Unexpectedly, however, the loss of the channel's RCK1 sites also had a dramatic effect on β1's influence on the Ca2+-independent properties of channel gating. The β1-induced change in M, which was 235-fold for the ΔE channel (Fig. 2 D), is absent in ΔEΔR channel. Indeed, with the D367A mutation present, it appears β1 no longer effects M. The bottoms of the two curves in Fig. 2 D are at the same place on the log (Popen) axis. This result argues that functional RCK1 sites are required for β1's effect on the intrinsic equilibrium constant between open and closed, usually referred to as L (for an analysis of mouse β1's effects on L see Wang and Brenner 2006).

β1 also Alters the Affinities of the RCK1 Sites

To examine β1's effect on Ca2+ sensing at the RCK1 sites we used the mutant (E399N)(D898A/D900A), which we refer to as ΔEΔB. In Fig. 5, BKCa currents from individual patches expressing ΔEΔB channels in the absence (A) or presence of β1 (B) are displayed. Patches were held at 0 mV and exposed to various [Ca2+]. For ΔEΔB channels application of Ca2+ caused an increase in Popen, but again the increase is not as great (∼104-fold) as it is with the ΔE channel (∼105-fold), presumably because the ΔEΔB channel had lost half of its high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites. More importantly, however, coexpression of β1 increased the maximal effect of Ca2+ on Popen. Fig. 5 C shows a comparison of the Popen/Popenmin versus [Ca2+] relations for the ΔEΔB channel in the presence (filled circles) and absence (open circles) of β1. The effect of β1 on Ca2+ sensing via the RCK1 sites is substantial. For the ΔEΔB channel, the change in Popen produced by saturating Ca2+ is ∼400 times larger in the presence of the β1. This again requires that β1 increase C (KC1/KO1) at the RCK1 site and therefore that it affects Ca2+ binding at this site as well.

β1 alters the affinity of the RCK1 site at constant voltage. (A and B) Outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔEΔB channels (A) or ΔEΔB + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relation for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is shown in C as the ratio NPopen to NPopenmin versus [Ca2+] and in D as Popen versus [Ca2+]. Each point represents the average of between 5 and 22 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.

β1 alters the affinity of the RCK1 site at constant voltage. (A and B) Outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔEΔB channels (A) or ΔEΔB + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relation for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is shown in C as the ratio NPopen to NPopenmin versus [Ca2+] and in D as Popen versus [Ca2+]. Each point represents the average of between 5 and 22 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.

To determine how much each dissociation constant is affected, we plotted (Fig. 5 D) the Popen versus [Ca2+] relations for the ΔEΔB (open circles) and ΔEΔB + β1 (filled circles) channels and fit these relations with Eq. 8. The affinities of the intact RCK1 sites in the presence and absence of β1 were then determined from the fits. The fit to the ΔEΔB data (solid line) yielded the following values (see also Table I):

And the fit to the ΔEΔB + β1 data (dashed curve) yielded the following values (see also Table I):

Thus, there is a small β1-induced change in the affinity of the RCK1 sites when the channel is closed, and a much larger relative change when the channel is open, the opposite of what we observed at the Ca2+ bowl. Most important, however, the changes are diametric and consequently the change in C is large (7.5→36), and it is this change that drives the expansion of the channel's Ca2+ dose–response curve along the ordinate in Fig. 5 C upon β1 coexpression. Interestingly, the β1-induced change in M is ∼200-fold for the ΔEΔB channel, similar to what is observed with the ΔE channel. Thus, unlike functional RCK1 sites, functional Ca2+ bowls are not required for β1's effects on the Ca2+-independent gating properties of the BKCa channel.

Although β1 has very large effects on the ΔEΔB channel's Ca2+ dose–response relation, there is a complicating factor that makes our conclusions about the effects of β1 on this site less than definitive. Our analysis assumes that there are no direct interactions between Ca2+ binding sites and voltage sensors. We have however shown previously (Sweet and Cox, 2008) that Ca2+ binding at the RCK1 site is voltage dependent, an effect that is most reasonably attributed to a direct intrasubunit interaction between voltage sensor and RCK1 Ca2+ binding site. Further, we have estimated the allosteric factor by which voltage sensor activation alters the equilibrium constant for Ca2+ binding at the RCK1 site (E) to be ∼2.8, and Horrigan and Aldrich (2002) arrived at a similar value, 2.4, based on the effect of Ca2+ on voltage sensor movement measured with gating currents. This means that Eq. 8 is not strictly correct for the ΔEΔB channel because as Ca2+ binds and the channels open, more voltage sensors will become active, even if the voltage is held constant, and this could lead to enhanced binding not accounted for by Eq. 8. The magnitude of this effect will depend on E and on the properties of the channel's voltage sensors. In terms of the Horrigan and Aldrich (HA) model, it will depend on L and Vhc, and Vho, zL, and zJ (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002). Furthermore, if β1 changes any of these parameters this could alter the channel's Ca2+ dose–response curve in a way that looks like an increase in C, when no real change in C has occurred.

Ideally, our experiments would have been performed at a negative voltage where the channel's voltage sensors are very rarely active; however, in the presence of the β1 subunit voltage sensors become active at far negative voltages where Popen at 3 nM [Ca2+] is too low to measure well, making this approach impractical. However, we examined whether the effects of β1 on the BKCa channel's voltage sensing parameters could account for its effects on the ΔEΔB channel's Popen versus [Ca2+] curve as follows. We simulated ΔEΔB Popen versus [Ca2+] curves using the HA model and voltage-sensing parameters that have been well established for the wild-type mSlo1 channel (Vho = 27 mV, Vhc = 151 mV, zJ = 0.58, zL = 0.41, L0 = 2 × 10−6, and E = 2.8) and Ca2+ dissociation constants we determined for the RCK1 site (KC = 23.2 µM and KO = 4.9 µM). This led to the Popen versus [Ca2+] curve shown in Fig. 6 B (dark curve). We then simulated the effects of β1 on the voltage-sensing parameters of the channel by lowering L from 2 × 10−6 to 2 × 10−9 to account for the large decline in M (Popen at 3 nM Ca2+), and we altered Vhc to +80 mV and Vho to −34 mV, parameters we have determined previously for α+β1 channels (Bao and Cox, 2005). The resulting curve is also shown in Fig. 6 B (gray curve), and as anticipated, altering these voltage-sensing parameters did increase the maximum effect of Ca2+ on Popen. The change in Popen brought about by saturating [Ca2+] increased 1.55-fold. Thus, some of the changes we have observed in the ΔEΔB channel's Popen versus [Ca2+] curve upon β1 expression likely arise from β1's effects on voltage sensing rather than Ca2+ binding. However, as seen in Fig. 6 A, β1 increases the maximum effect of Ca2+ on Popen 708-fold—far greater than the effect we anticipate due to the linkage between Ca2+ binding and voltage sensing (1.55-fold). In fact the anticipated effect is <1% of the true effect of β1. Thus, this complication not withstanding, it does appear that β1 alters the true Ca2+ affinities of the RCK1 sites as well as the Ca2+ bowl sites.

β1's effects on the BKCa channel's voltage-sensing parameters cannot account for the β1-induced changes in the ΔEΔB channel's Ca2+ dose–response relation. (A) ΔEΔB (open circles) and ΔEΔB + β1 (filled squares) Ca2+ dose–response relations normalized to their minima. (B) Simulated Ca2+ dose–response curves for the ΔEΔB (black curve) and ΔEΔB + β1 (gray curve) channels assuming that β1 only affects the voltage-sensing properties of the channel. The curves were simulated with an HA model using parameters we have determined previously (Bao and Cox, 2005; Sweet and Cox, 2008). For the ΔEΔB (α-only channel): L = 2e-6, Vhc =151 mV, Vho = 27 mV, E = 2.8, and zL = 0.41, and zJ = 0.58, Kc = 23.2 µM, and Ko = 4.9 µM. To simulate the effects of β1, L0 was moved to 2e-9, Vhc to 80 mV, and Vho to −34 mV. The remaining parameters were unchanged.

β1's effects on the BKCa channel's voltage-sensing parameters cannot account for the β1-induced changes in the ΔEΔB channel's Ca2+ dose–response relation. (A) ΔEΔB (open circles) and ΔEΔB + β1 (filled squares) Ca2+ dose–response relations normalized to their minima. (B) Simulated Ca2+ dose–response curves for the ΔEΔB (black curve) and ΔEΔB + β1 (gray curve) channels assuming that β1 only affects the voltage-sensing properties of the channel. The curves were simulated with an HA model using parameters we have determined previously (Bao and Cox, 2005; Sweet and Cox, 2008). For the ΔEΔB (α-only channel): L = 2e-6, Vhc =151 mV, Vho = 27 mV, E = 2.8, and zL = 0.41, and zJ = 0.58, Kc = 23.2 µM, and Ko = 4.9 µM. To simulate the effects of β1, L0 was moved to 2e-9, Vhc to 80 mV, and Vho to −34 mV. The remaining parameters were unchanged.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have examined the mechanism by which the BKCa channel's β1 subunit increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of channel activation. To be as accurate as possible, we used unitary–current recordings from patches containing from a few hundred to just a few channels. This allowed us to determine Popen over seven orders of magnitude. To be as model independent as possible, we made measurements at constant voltage, and where possible low Popen, such that the amplitudes and shapes of the resulting Ca2+ dose–response curves were dependent primarily, if not exclusively, on the channel's Ca2+ binding parameters. The essential assumptions we made in fitting our data were as follows: (1) that there is a single conformational change between open and closed that can occur with any number of Ca2+ bound, an idea that is consistent with a great many single-channel and macroscopic BKCa channel studies and all current models (McManus and Magleby, 1991; Cox et al., 1997; Cui et al., 1997; Horrigan et al., 1999; Horrigan and Aldrich, 1999, 2002; Rothberg and Magleby, 1999, 2000; Cox and Aldrich, 2000a); (2) that there are four of each type of high-affinity site. This has been established for the Ca2+ bowl (Niu and Magleby, 2002), and given the fourfold symmetry of the channel, this seems likely to be the case for the RCK1 site as well; and (3) that there are no interactions between binding sites of the same type or between Ca2+ binding and voltage sensor movement.

We found that the 0 mV Ca2+ dose–response curve of BKCa channels containing only functional RCK1 sites could be well fitted by supposing that each site independently influences opening, and that each site has a dissociation constant of 15.8 µM when the channel is closed and 2.1 µM when the channel is open. These values produce a C value of 7.5, which allows us to calculate that each Ca2+ bound to a Ca2+ bowl site decreases the energy difference between open and closed by 4.9 KJ/mol.

In the presence of β1, the RCK1 site's dose–response curve at 0 mV could also be well fitted with a simple model and yielded values for KC and KO of 18.5 and 0.52 µM, respectively. These values produce a substantial C value of 36 (8.8 KJ/mol per binding event), which we think is in large part responsible for the dramatic increase in the influence of Ca2+ on Popen brought about by β1 in the ΔEΔB channels. As discussed above, however, our estimates of these values are complicated by an interaction between Ca2+ binding and voltage at the RCK1 sites. But we have simulated the influence that this complication will likely have on Ca2+ binding in the presence of β1, and it turns out to very small compared with the effect of β1 observed. Thus, we do not think this linkage has greatly distorted our measurement of KC and KO.

Ca2+ binding to the Ca2+ bowl is not voltage sensitive (Sweet and Cox, 2008); thus, our conclusions drawn from data for the Ca2+ bowl sites are more clear. We found that the Ca2+ bowl's dose–response curve at 0 mV could be well fitted by supposing that each Ca2+ bowl independently influences opening, and that each site has a dissociation constant for Ca2+ of 2.1 µM when the channel is closed and 0.56 µM when the channel is open. These values produce a C of 3.75, which allows us to calculate that each Ca2+ bound at a Ca2+ bowl site decreases the energy difference between open and closed by 3.2 KJ/mol. These numbers may be compared with previous estimates of KC and KO for this site. Xia et al. (2002) estimated KC = 4.5 ± 1.7 µM and KO = 2.0 ± 0.7 µM (C = 2.25), and Bao et al. (2002) estimated KC = 3.8 ± 0.2 and KO = 0.94 ± 0.06 µM (C = 4.0). And in Sweet and Cox (2008), we estimated KC = 3.13 ± 0.28 µM and KO = 0.88 ± 0.06 µM (C = 3.55). Thus, our current estimates are close to our previous estimates, especially in terms of C.

More interestingly, we found that coexpression of β1 changed the ΔEΔR channel's Popen versus [Ca2+] relation in a manner that indicated that the affinity of the Ca2+ bowl site for Ca2+ is changed in the presence of β1. In the presence of β1, the ΔEΔR channel's dose–response curve at 0 mV could be well fitted by supposing that each Ca2+ bowl independently influences opening, and that each site has an affinity of 5.9 µM when the channel is closed and 0.67 µM when the channel is open. These values produce a C value of 8.8, which allows us to calculate that with β1 present, each Ca2+ bound at a Ca2+ bowl decreases the energy difference between open and closed by 5.3 KJ/mol.

These numbers are difficult to compare with previous estimates of the affinities of the BKCa channel in the presence of β1. Bao and Cox (2005) estimated the affinities of the channel in the presence of β1 to be KC = 3.71 µM and KO = 0.88 µM (C = 4.2) for site 1 and KC = 5.78 µM and KO = 0.73 µM (C = 7.9) for site 2. These estimates, however, were based on the assumption that β1 affected the affinity of only one of the two binding sites (site 2), which we now think is not the case. But interestingly, and of relevance here, Cox and Aldrich (2000) observed that the affinity of the channel for Ca2+ in the open conformation must not change upon expression of β1, as β1 does not alter the critical [Ca2+] required to begin to see a leftward shift in the channel's G-V relation (Cox and Aldrich, 2000a). This is in agreement with our data that show that expression of β1 does not appreciably alter KO for the higher-affinity site (Ca2+ bowl: Koα = 0.56 µM, KOα+β1 = 0.67 µM).

In considering the effects of β1 on Ca2+ binding, it is interesting to note that the BKCa β1 subunit has very little intracellular sequence, just its N and C termini—15 and 13 amino acids long, respectively. The rest of the protein is comprised of two transmembrane domains and a large extracellular loop—118 amino acids. Thus, if β1 subunits alter the channel's affinity for Ca2+ by interacting directly with Ca2+ binding sites, generally accepted to be contained within the cytoplasmic C terminus of the channel, they seemingly must do so through these short intracellular termini. Supporting this idea, chimera experiments with β1 and β2 (Orio and Latorre, 2005) and β1 N- and C-terminal deletion experiments (Wang and Brenner, 2006) have shown that these termini play a critical role in transmitting β1's effects to the channel proper.

In addition to β1's effects on Ca2+ binding, and in agreement with the previous findings of Wang and Brenner (2006), we found that mouse β1 reduces Popen at 0 mV in the absence of Ca2+, presumably by lowering L. Strikingly, our results show that a mutation at a Ca2+ binding site (D367A) not only eliminates Ca2+ binding at the RCK1 sites, but it also eliminates β1's ability to reduce Popen at 0 mV in the absence of Ca2+. That is, a single Ca2+ binding site mutation affects both the mechanism by which the channel senses Ca2+ and also the mechanism by which β1 influences the intrinsic energetics of opening.

We also found that when we combine mutations at all three types of Ca2+ binding sites—E399N (low-affinity site), D367A (RCK1 site), and D898/D900 (Ca2+ bowl)—we see no effect of Ca2+ on channel gating in the α-only channel, and we see no restoration of an effect of Ca2+ on channel gating by β1. This in contrast to the work of Qian and Magleby (2003), who found that coexpression of β1 restored some Ca2+ sensitivity to a similar triple mutant. We do not know why we did not see the restorative effect of β1 observed by Qian and Magleby. The most straightforward explanation is that the Ca2+ binding sites were disabled by the mutations and could not be fixed by β1. However, the main differences between the two studies were as follows: our recordings were made at 0 mV, whereas theirs were conducted at +50 mV. The mutations used at each binding site were not exactly the same between the two studies, and Qian and Magleby recorded from single-channel patches, whereas the patches we used typically contained many channels. Furthermore, Qian and Magleby did not see the restorative effect of β1 in every experiment, but rather they reported a large variability from patch to patch. This would seem to suggest that perhaps there is a subtle environmental factor required for the effect they observed that was absent from our experiments.

Our measurements of the effects of β1 on Ca2+ binding also stand in some contrast to the recent paper of Yang et al. (2008). They found that the mutation R167A in the voltage-sensing domain of the mSlo1 channel eliminates β1's ability to alter the channel's G-V curve at all [Ca2+]. This result suggests that by altering just voltage sensor movement one can disrupt the β1-induced enhancement of Ca2+ sensitivity altogether. It seems hard to imagine how such a mutation could simultaneously eliminate β1's effects on voltage sensor movement and Ca2+ binding at both binding sites, unless these processes are physically more intertwined than previously thought.

Perhaps rather than affecting Ca2+ binding directly, the β1 subunit might be affecting a linkage between Ca2+ binding and voltage sensing, which in turn affects Ca2+ binding. Indeed, we have shown recently (Sweet and Cox, 2008) that such a linkage exists between the RCK1 sites and the voltage sensors, so it is possible that an enhancement of the allosteric factor at this linkage, E, could create enhanced binding affinity. It would be interesting to explore this linkage in α+β1 channels. However, we found no such linkage between Ca2+ bowl sites and the channel's voltage sensors (Sweet and Cox, 2008); thus, we do not think that such an effect is involved in the β1-induced changes in the binding affinity we observed at the Ca2+ bowl sites.

In conclusion, we have shown that the BK β1 subunit has effects on the affinities of the BKCa channel's high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites. It primarily increases the affinity of the RCK1 sites when the channel is open, and it primarily decreases the affinity of the Ca2+ bowl sites when the channel is closed. Both of these modifications increase the difference in affinity between open and closed, such that Ca2+ binding at either site has a larger effect on channel opening when β1 is present.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by program project grant P01-HL077378 and predoctoral fellowship F31 NS047823 from the National Institutes of Health.

Edward N. Pugh Jr. served as editor.

References

Abbreviations used in this paper: BKCa, large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium; G-V, conductance–voltage; HA, Horrigan and Aldrich; Popen, open probability.

![Figure 1. β1 increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of BKCa-channel activation. (A and B) Macroscopic currents recorded from ΔE channels in the absence and presence of β1. Currents are from inside-out macropatches from TSA 201 cells exposed to 9.7 µM Ca2+. (C and D) G-V relations determined at the following Ca2+ concentrations: 0.003, 0.360, 1.4, 5.3, 113, and 2,500 µM for the mutant channel ΔE (C) and ΔE + β1 (D). Each curve represents the average of between 4 and 22 individual curves. Error bars indicate SEM. The solid curves are Boltzmann fits with the following parameters: ΔE, 3 nM Ca2+: Q = 1.21 e, V1/2 = 183 mV; 360 nM Ca2+: Q = 1.18 e, V1/2 = 151 mV; 1.4 µM Ca2+: Q = 1.47 e, V1/2 = 101 mV; 5.4 µM Ca2+: Q = 1.38 e, V1/2 = 59 mV; 113 µM Ca2+: Q = 1.00 e, V1/2 = 13 mV; 2.5 mM Ca2+: Q = 1.04 e, V1/2 = −5.7 mV. ΔE + β1, 3 nM Ca2+: Q = 0.46 e, V1/2 = 230 mV; 360 nM Ca2+: Q = 0.51 e, V1/2 = 197 mV; 1.4 µM Ca2+: Q = 0.70 e, V1/2 = 131 mV; 5.4 µM Ca2+: Q = 0.94 e, V1/2 = 46 mV; 113 µM Ca2+: Q = 0.83 e, V1/2 = −57 mV; 2.5 mM Ca2+: Q = 0.87 e, V1/2 = −90 mV. (E) Plots of half-maximal activation voltage (V1/2) versus [Ca2+] for traces shown in C and D. (F) Ca2+ dose–response curves determined for ΔE in the presence and absence of β1 at 0 mV. The curves are fitted with the Hill equation:Fit parameters are as follows: ΔE (Kd = 68 µM, n = 1.4); ΔE + β1 (Kd = 32 µM, n = 1.1).](https://cdn.rupress.org/rup/content_public/journal/jgp/133/2/10.1085_jgp.200810129/6/m_jgp_200810129_lw_fig1.jpeg?Expires=1771341975&Signature=kcvFffR4a2ePiYx4RzQ2HmyXgNdDf-o7y74X1gNESsI6RM~r5K13B~QIJWPLf0iLT9P458CUxXD3~kJs9RmBUCxZGgKYEwlWKzeZ7VDw-aGL3jjrJ~zZeBmrYdr-l1ykDP3GccASwRKW1DqIRU8lTOYi3ywoqVbxWHDKG4mYxLceloV28js8K3~oDhvUG9gzCZFpMv3NYb8dcwosh7xKVAb1m2V13qX7Ke~H7xTkbgobRqXzNg6RMoybjV767FFXg-sMSwOQCW~oGYlBGxNsekFgziwm-aKsLLQGH6DPWQdGxf0AUQNPG4wv6twDjlpxYJcGNa46Zi6WRlU6VO7gcg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. β1 increases the Ca2+ dependence of Popen at a constant voltage. (A and B) Outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔE channels (A) or ΔE + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relations for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is show. Each point represents the average of between 7 and 30 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM. The Popen curves are fitted with Eq. 1 yielding values of: ΔE, KC1 = 4.3 µM, KO1 = 1.1 µM, KC2 = 7.9 µM, KO2 = 1.3 µM, M = 4.7 × 10−6; ΔE + β1, KC1 = 2.2 µM, KO1 = 0.5 µM, KC2 = 32 µM, KO2 = 0.6 µM, M = 2.0 × 10−8. Additionally, ΔE was fitted assuming that the two types of binding sites are equivalent. The fit yield values of KC = 5.9 µM, KO = 1.2 µM, and M = 4.2 × 10−6.](https://cdn.rupress.org/rup/content_public/journal/jgp/133/2/10.1085_jgp.200810129/6/m_jgp_200810129r_lw_fig2.jpeg?Expires=1771341975&Signature=jGeC2Yb7mDneNrIkpyWnv73GkZSw9X-iXqilu2pNx5xRtrmKaTPbAAXEYG8zl0zEeKgBRYnLxEXxJ29~SKNY3TzvzJdu52dplNFHBK4EscOEA0zXSdPCSry4dqTgdvK1~3D7p0ZcPXDcS5cDKr2iEoGVLpN6nEDPYoOLpXlY6uDC8yW947puD0aoP7Q9psfKnd2g-2Y-nj0-xSE5j27DSoo0MwCEFJ3b0qBDxaCSSz31TleNwwpFFfgJ99nJ~0qJ6OdG-RcWUps1AJHetplQXfmWX-TzNInzziSb-qSS1btqklMUi0cnZqMTvzT~Jtvmk0proP7wMwh1MlLbO6wrwg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Mutating all three types of Ca2+ binding sites eliminates the Ca2+ dependence of Popen. Dose–response relationships for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV were obtained by plotting the mean log ratio of NPopen in the presence and absence of Ca2+ for ΔEΔRΔB (open circles) and ΔEΔRΔB + β1 (filled circles) channels. Each point represents the average between 7 and 11 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.](https://cdn.rupress.org/rup/content_public/journal/jgp/133/2/10.1085_jgp.200810129/6/m_jgp_200810129_lw_fig3.jpeg?Expires=1771341975&Signature=j6S~j4V496NeGib48zjQiyuN5-b76KmZlrYiABNJ16jdZ1k6RKyZeSWuRmKIE2u2iSiDIh8RSIBL6F7So-i4UkVNZK9HoyxF7Lf5BInqRqLvEJhPQ3-pgxM16N0cH3rf1R7a0Xw8veM0-GoCd0yA8uWW4ifQG3IpKCyZwkN1YNJnLjGGOaZhLHPetXGu63wnxBCFN3W~86Zf9GujOC0fOseiBePZCopLDPYyuPQUOtscMIR2SpReobcpi4qvkP2yZT~MeZ5PWAaUxOzAkHrQ~kXfnc59g3Ktzl29LTwuzSDpill2tArht~vSR7v7zjHCX42WRDrney~lspcbNUp9Ug__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. β1 alters the affinity of the Ca2+ bowl at constant voltage. (A and B) outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔEΔR channels (A) or ΔEΔR + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relation for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is plotted in C as the ratio of NPopen to NPopenmin versus [Ca2+] and in D as Popen versus [Ca2+]. Each point represents the average of between 8 and 16 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.](https://cdn.rupress.org/rup/content_public/journal/jgp/133/2/10.1085_jgp.200810129/6/m_jgp_200810129_lw_fig4.jpeg?Expires=1771341975&Signature=RuKPV8tGIjDuED73zPbv4JNLFVipJI8bsBZaHUDPEDAi~2-3rrVH4empD7iDtoV-WRZJGxeJbE21Ts6rgMM2pR62e9IjgnwloAOLN0GEDlysEiw6vsD~jPkx-TvuRH9RGf5osz1WIgavNUHWG7UCQnJg7eviiXmugkqt0XCdPAgTUK586aBwKsjm52crZWLJ9toCiPHoEPuEaHZgi-ewtPfdvGBkxlspnu4ha-~~~wUUMtnD2FRDQeIUL2KcfnZg7mqvOGm4R09Em2EjqyuYoy0zhN7cdnwx6Nr~J6GpVE6z3RpcVgWUmjRSDZEr81CVcLYUVw-lDdDf7VfWjS-UbA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. β1 alters the affinity of the RCK1 site at constant voltage. (A and B) Outward K+ currents recorded at 0 mV and filtered at 2 kHz from macropatches containing ΔEΔB channels (A) or ΔEΔB + β1 channels (B) exposed to the indicated [Ca2+]. These currents demonstrate that Popen increases in a Ca2+-dependent manner when voltage is constant. A comparison of the dose–response relation for the effect of Ca2+ on Popen at 0 mV in the absence or presence of β1 is shown in C as the ratio NPopen to NPopenmin versus [Ca2+] and in D as Popen versus [Ca2+]. Each point represents the average of between 5 and 22 patches at each [Ca2+] tested. Error bars represent SEM.](https://cdn.rupress.org/rup/content_public/journal/jgp/133/2/10.1085_jgp.200810129/6/m_jgp_200810129_lw_fig5.jpeg?Expires=1771341975&Signature=OjcUxYIvM4rBNEBspzf5fylOzBvppAw1hxKL3lNUyESvRXkqrhNpfTdxYX3XL3N5jJwyIN2CEeCyI-QJ07-D1gJgi7LLOiIPQPJGyDRFnPTOlXub3BvCsD4rQvYZ35b7rfMkYoBZhxJc9QBZnS5qP3-dqXxBr~oPKdBCAfjtQN7zQD3qZPMJjhKFh9~5rvw8Sz6wypqEN0Yj1cYYO2L5QMnrbalxhpKY44mz0ohZ2pj~qD10lpdXmffFoL~E23eSplgiGCGASQlqAdNKFPTIJSSlQkD-O90ryga6Wsvzpt7tTAg1LekSlMau4lfyolWJmJb-SFhpT1Jp4rxHh2APQQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)