Inflammation is associated with bone marrow failure syndromes, but how specific molecules impact the bone marrow microenvironment is not well elucidated. We report a novel role for the miR-145 target, Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain containing adaptor protein (TIRAP), in driving bone marrow failure. We show that TIRAP is overexpressed in various types of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and suppresses all three major hematopoietic lineages. TIRAP expression promotes up-regulation of Ifnγ, leading to myelosuppression through Ifnγ-Ifnγr–mediated release of the alarmin, Hmgb1, which disrupts the bone marrow endothelial niche. Deletion of Ifnγ blocks Hmgb1 release and is sufficient to reverse the endothelial defect and restore myelopoiesis. Contrary to current dogma, TIRAP-activated Ifnγ-driven bone marrow suppression is independent of T cell function or pyroptosis. In the absence of Ifnγ, TIRAP drives myeloproliferation, implicating Ifnγ in suppressing the transformation of MDS to acute leukemia. These findings reveal novel, noncanonical roles of TIRAP, Hmgb1, and Ifnγ in the bone marrow microenvironment and provide insight into the pathophysiology of preleukemic syndromes.

Introduction

Bone marrow failure (BMF) syndromes, which may be acquired or inherited, are heterogeneous disorders that result in peripheral blood cytopenias. Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) malignancies, which are characterized by dysplastic morphology, cellular dysfunction, and peripheral blood cytopenias. MDS patients also have a significantly increased risk of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML; Sperling et al., 2017).

Dysregulation of immune responses has been implicated in MDS and other BMF disorders (Starczynowski et al., 2010; Rhyasen et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2013; Medinger et al., 2018; Barreyro, Chlon and Starczynowski, 2018). There is significant evidence for IFNγ playing a key role in BMF syndromes (Pietras, 2017; Smith et al., 2016; Hemmati et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2015). However, there are different theories, which are sometimes conflicting, regarding the mechanism by which IFNγ promotes BMF. On the one hand, IFNγ has been suggested to recruit T cells that mediate cytopenias through immune destruction of hematopoietic cells. On the other hand, T cells produce IFNγ, which is postulated to directly result in the death of bone marrow cells (Gravano et al., 2016; Glenthøj et al., 2016). More recently, IFNγ has been shown to inhibit thrombopoietin (TPO) and possibly erythropoietin signaling through their cognate receptors by forming heterodimeric complexes and interfering with ligand–receptor interactions, thereby leading to impaired megakaryocytic and erythroid differentiation (Alvarado et al., 2019).

However, this does not explain the myelosuppression that is also seen with excess IFNγ (Lin et al., 2014). Recent evidence suggests a role for alarmin-triggered pyroptosis, a Caspase-1–dependent proinflammatory lytic cell death, in mediating myelosuppression in MDS (Basiorka et al., 2016). Alarmins such as S100A8 and S100A9 have been suggested to drive pyroptotic cell death in MDS (Basiorka et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2013; Schneider et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2004; Zambetti et al., 2016). However, the generality of alarmin-triggered BMF across MDS is not known. Given the heterogeneity of MDS, other alarmins may also be involved but have not been studied thus far, and whether IFNγ can also trigger alarmin-induced death is not known. There is also very little information on the triggers that underlie up-regulation of IFNγ in these BMF syndromes (Smith et al., 2016; Hemmati et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2015; Zeng et al., 2004). Interstitial deletion of chromosome 5q is the most common cytogenetic abnormality observed in MDS, accounting for ∼10% of all cases (Zahid et al., 2017). Our laboratory has previously shown that miR-145, which is located on chromosome 5q, targets Toll/IL-1R domain–containing adaptor protein (TIRAP), but the role of TIRAP in BMF has not been studied (Starczynowski et al., 2010).

In this study, we identify a novel role for the innate immune adaptor protein TIRAP in dysregulating normal hematopoiesis through activation of Ifnγ. TIRAP induces Ifnγ through a noncanonical pathway and leads to the development of BMF. TIRAP-induced activation of Ifnγ releases the alarmin, Hmgb1, which suppresses the bone marrow endothelial niche, which in turn promotes myeloid suppression. In contrast, erythroid and megakaryocytic suppression appears to be a direct effect of Ifnγ that is independent of the Ifnγ receptor. In contrast to what has previously been suggested for the mechanism of Ifnγ-induced BMF, BMF induced by the TIRAP–Ifnγ–Hmgb1 axis does not require natural killer (NK) or T cell function or pyroptosis.

Results

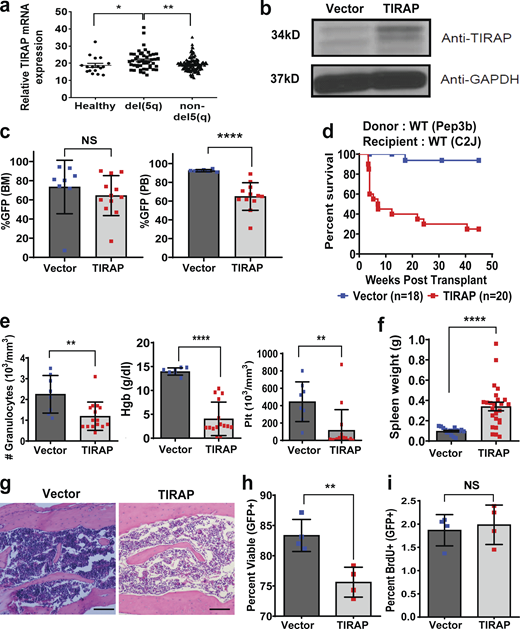

Constitutive expression of TIRAP results in BMF

To examine TIRAP expression across MDS subtypes, we analyzed the results of a gene expression study performed on CD34+ cells from MDS patients and controls (Pellagatti et al., 2010) and found that TIRAP expression was increased in del(5q) MDS compared with healthy controls and in MDS patients diploid at chromosome 5q (Fig. 1 a). To determine whether constitutive expression of TIRAP contributes to BMF, we stably expressed TIRAP or an empty vector control in mouse hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs; Fig. 1 b). Lethally irradiated recipient mice were transplanted with transduced HSPCs, along with WT helper cells, with similar levels of bone marrow engraftment in experimental and control animals (Fig. 1 c). However, the peripheral blood output of TIRAP-expressing cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 1 c). This is in line with what is seen in MDS, where there is bone marrow engraftment but lack of circulation of MDS cells in the peripheral blood. Mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing HSPCs had significantly reduced overall survival due to BMF compared with controls (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1, d–g). There was significant anemia (P < 0.0001), leukopenia (P = 0.007), thrombocytopenia (P = 0.003), and splenomegaly in TIRAP-transplanted mice at 4 wk (Fig. 1, e and f). Histologic examination of bone marrow sections and quantification of bone marrow cellularity revealed a reduction in total cell number in TIRAP-transplanted bone marrow compared with controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 1 g and Fig. S1 a).

Constitutive expression of TIRAP in HSPCs leads to BMF.(a) TIRAP mRNA expression in CD34+ cells isolated from bone marrow (BM) of healthy controls, a del(5q) MDS patient, and patients with normal diploid copy number at chromosome 5q (from data generated in Pellagatti et al., 2010). (b) WT mouse HSPCs transduced with empty vector (n = 8) or TIRAP (n = 10) were sorted for GFP expression and immunoblotted with antibodies against TIRAP and GAPDH. (c) Bone marrow and peripheral blood (PB) engraftment in WT mice transplanted with vector- (n = 8) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 12) bone marrow cells. (d) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for WT mice reconstituted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 18) or TIRAP (n = 20); P < 0.0001. Data pooled from five separate transplants. (e) Granulocyte, hemoglobin (Hgb), and platelet (Plt) counts in the peripheral blood from TIRAP-transduced (n = 15) and vector-transduced (n = 8) WT mice at experimental end point. (f) Spleen weights of vector- (n = 8) and TIRAP-transplanted (n = 15) WT mice at experimental end point. (g) Representative images of H&E-stained bone marrow sections showing bone marrow hypocellularity in TIRAP-transplanted WT mice compared with vector transplantation. Scale bar: 100 µm for 10× magnification. (h) Percentage of viable (Annexin V−/PI−) HSPCs from vector-transplanted (n = 4) or TIRAP-transplanted (n = 4) WT mice 3–4 wk after transplant. (i) BrdU incorporation was measured in WT BM transduced with TIRAP (n = 4) or vector (n = 4) collected at end point after transplantation. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Data pooled from two to four independent experiments (c–i). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

Constitutive expression of TIRAP in HSPCs leads to BMF.(a) TIRAP mRNA expression in CD34+ cells isolated from bone marrow (BM) of healthy controls, a del(5q) MDS patient, and patients with normal diploid copy number at chromosome 5q (from data generated in Pellagatti et al., 2010). (b) WT mouse HSPCs transduced with empty vector (n = 8) or TIRAP (n = 10) were sorted for GFP expression and immunoblotted with antibodies against TIRAP and GAPDH. (c) Bone marrow and peripheral blood (PB) engraftment in WT mice transplanted with vector- (n = 8) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 12) bone marrow cells. (d) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for WT mice reconstituted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 18) or TIRAP (n = 20); P < 0.0001. Data pooled from five separate transplants. (e) Granulocyte, hemoglobin (Hgb), and platelet (Plt) counts in the peripheral blood from TIRAP-transduced (n = 15) and vector-transduced (n = 8) WT mice at experimental end point. (f) Spleen weights of vector- (n = 8) and TIRAP-transplanted (n = 15) WT mice at experimental end point. (g) Representative images of H&E-stained bone marrow sections showing bone marrow hypocellularity in TIRAP-transplanted WT mice compared with vector transplantation. Scale bar: 100 µm for 10× magnification. (h) Percentage of viable (Annexin V−/PI−) HSPCs from vector-transplanted (n = 4) or TIRAP-transplanted (n = 4) WT mice 3–4 wk after transplant. (i) BrdU incorporation was measured in WT BM transduced with TIRAP (n = 4) or vector (n = 4) collected at end point after transplantation. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Data pooled from two to four independent experiments (c–i). Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F1.

BMF is not due to a homing defect, and TIRAP overexpression alters hematopoiesis by affecting both progenitor populations and the bone marrow microenvironment. (a) Trypan blue counts of total cells (live + dead) in the femurs of mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 15) or vector-transduced (n = 6) HSPCs at end point. Data pooled from two independent transplants. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow collected from mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 4) and TIRAP-transduced (n = 4) bone marrow 22 h after transplant and quantification of the total number of transduced cells that homed to the bone marrow per mouse. (c) Schematic illustrating progenitor homing assay. BM, bone marrow; BMT, BM transplantation; CFC, colony-forming cells. (d) Quantification of progenitor homing efficiency. vector, n = 3; TIRAP, n = 3. Homing efficiency was calculated using the following formula: (e) Gating strategy for analysis of contributions of GFP- and YFP-labeled HSPCs to hematopoietic reconstitution in the myeloid cell populations. The CD45.1 gate was used to identify donor cells in the bone marrow of the transplanted mouse. Mac1+Gr1+ cells were identified as myeloid cell populations. The GFP- and YFP-positive cells were gated using negative, GFP-only, and YFP-only controls. FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter. (f) Staining of bone marrow stromal cells was performed as previously described (Schepers et al., 2012). Total endothelial cells were identified as lin−CD45−CD31+, mesenchymal stromal cells were identified as lin−CD45−Sca-1+CD51+, and osteoblastic cells were identified as lin−CD45−Sca-1−CD51+. (g) Representative images of CD31-stained bone sections taken at end point of WT mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing (n = 2) or vector-expressing (n = 2) HSPCs. Scale bar: 50 µm for 20× magnification. Due to extremely low bone marrow cellularity, TIRAP-1 shows nonspecific staining of CD31 in the interstitial spaces. ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

BMF is not due to a homing defect, and TIRAP overexpression alters hematopoiesis by affecting both progenitor populations and the bone marrow microenvironment. (a) Trypan blue counts of total cells (live + dead) in the femurs of mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 15) or vector-transduced (n = 6) HSPCs at end point. Data pooled from two independent transplants. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow collected from mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 4) and TIRAP-transduced (n = 4) bone marrow 22 h after transplant and quantification of the total number of transduced cells that homed to the bone marrow per mouse. (c) Schematic illustrating progenitor homing assay. BM, bone marrow; BMT, BM transplantation; CFC, colony-forming cells. (d) Quantification of progenitor homing efficiency. vector, n = 3; TIRAP, n = 3. Homing efficiency was calculated using the following formula: (e) Gating strategy for analysis of contributions of GFP- and YFP-labeled HSPCs to hematopoietic reconstitution in the myeloid cell populations. The CD45.1 gate was used to identify donor cells in the bone marrow of the transplanted mouse. Mac1+Gr1+ cells were identified as myeloid cell populations. The GFP- and YFP-positive cells were gated using negative, GFP-only, and YFP-only controls. FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter. (f) Staining of bone marrow stromal cells was performed as previously described (Schepers et al., 2012). Total endothelial cells were identified as lin−CD45−CD31+, mesenchymal stromal cells were identified as lin−CD45−Sca-1+CD51+, and osteoblastic cells were identified as lin−CD45−Sca-1−CD51+. (g) Representative images of CD31-stained bone sections taken at end point of WT mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing (n = 2) or vector-expressing (n = 2) HSPCs. Scale bar: 50 µm for 20× magnification. Due to extremely low bone marrow cellularity, TIRAP-1 shows nonspecific staining of CD31 in the interstitial spaces. ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

Bone marrow homing experiments revealed no difference in the homing ability or clonogenic activity of TIRAP-transduced HSPCs (Fig. S1, b–d), suggesting that the BMF was not due to a homing defect. There was increased cell death, but no difference in proliferation in vivo in TIRAP-expressing HSPCs compared with controls (Fig. 1, h and i).

Constitutive TIRAP expression has non–cell-autonomous effects on hematopoiesis

Examination of the bone marrow of moribund mice showed significant impairment of TIRAP-transplanted mice to reconstitute hematopoiesis (Fig. 2). This impairment was evident despite transplantation of sufficient WT helper cells to sustain normal hematopoiesis, suggesting that BMF subsequent to TIRAP expression was likely due to non–cell-autonomous mechanisms. Differentiation into early granulocyte/macrophage populations (CD11b+Gr-1+) and mature granulocytes (Gr-1+) was compromised in TIRAP-transduced HSPCs, as well as in the nontransduced population, in transplanted bone marrow of TIRAP-transduced HSPCs compared with controls (Fig. 2, a–c). Erythroid (Fig. 2, d–f) and megakaryocytic (Fig. 2, g–i) differentiation of TIRAP-transduced HSPCs as well as WT competitor cells were also significantly impaired in transplanted mice (Fig. 2 f). The inability of mice to restore peripheral blood counts following transplantation despite cotransplantation of WT HSPCs led us to question whether the defect in mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced bone marrow was due solely to the reduced survival of mature differentiated cells, or whether there was a block in differentiation at the level of more primitive progenitor cells. To address this question, we quantified the absolute number of progenitor cells (LSK: Lin−, c-Kit+, Sca-1+; granulocyte–monocyte progenitors [GMP]: Lin−, c-Kit+, Sca-1−, CD34+, CD16/32+; common myeloid progenitors [CMP]: Lin−, c-Kit+, Sca-1−, CD34+, CD16/32−; and megakaryocyte–erythrocyte progenitors [MEP]: Lin−, c-Kit+, Sca-1−, CD34−, CD16/32−) in the transplanted mice. We found reductions in the total number of viable CMP and MEP progenitor populations in the TIRAP-transduced bone marrow of transplanted mice (Fig. S1 e), accounting for the observed peripheral cytopenia. Additionally, there was a more pronounced reduction in the number of viable progenitor populations within the cotransplanted WT helper cells, which resulted in reduction of the LSK and GMP populations as well as CMP and MEP populations. Taken together, these findings suggest that non–cell-autonomous mechanisms play a large role in TIRAP-mediated BMF.

Constitutive TIRAP expression disrupts normal hematopoiesis in a non–cell-autonomous manner. (a–i) Immunophenotyping of myeloid (a–c), erythroid (d–f), and megakaryocytic (g–i) lineages from the bone marrow of WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 5) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs 3–4 wk after transplant. Absolute cell numbers of total HSPCs (upper), as well as the contribution of transduced (GFP+; middle) and competitor (GFP−; lower) cells are presented. Data pooled from two independent repeats on mice taken from four independent transplants. (j and k) Enumeration of progenitor cells including LSK, CMP, GMP, and MEP in bone marrow of vector-transplanted (n = 4) or TIRAP-transplanted (n = 4) mice 3–4 wk after transplant. The contributions of transduced (GFP+; j) and competitor cells (GFP−; k) are presented. (l) Cell viability was assessed by Annexin V/PI staining in HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 3) or TIRAP (n = 3). (m) Cell cycling was measured by BrdU incorporation in TIRAP-transduced (n = 5) or vector-transduced (n = 5) HSPCs in vitro. Data pooled from two independent repeats (j–m). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

Constitutive TIRAP expression disrupts normal hematopoiesis in a non–cell-autonomous manner. (a–i) Immunophenotyping of myeloid (a–c), erythroid (d–f), and megakaryocytic (g–i) lineages from the bone marrow of WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 5) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs 3–4 wk after transplant. Absolute cell numbers of total HSPCs (upper), as well as the contribution of transduced (GFP+; middle) and competitor (GFP−; lower) cells are presented. Data pooled from two independent repeats on mice taken from four independent transplants. (j and k) Enumeration of progenitor cells including LSK, CMP, GMP, and MEP in bone marrow of vector-transplanted (n = 4) or TIRAP-transplanted (n = 4) mice 3–4 wk after transplant. The contributions of transduced (GFP+; j) and competitor cells (GFP−; k) are presented. (l) Cell viability was assessed by Annexin V/PI staining in HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 3) or TIRAP (n = 3). (m) Cell cycling was measured by BrdU incorporation in TIRAP-transduced (n = 5) or vector-transduced (n = 5) HSPCs in vitro. Data pooled from two independent repeats (j–m). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

TIRAP alters the bone marrow microenvironment

In contrast to our findings in vivo (Fig. 1, h and i), TIRAP-expressing HSPCs cultured in vitro displayed increased viability and proliferation compared with control HSPCs, suggesting a requirement of the microenvironment for TIRAP-induced BMF (Fig. 2, j and k). Given the role of immune dysregulation in various BMF syndromes, we examined whether the lymphoid populations in the bone marrow of the transplanted mice were affected. The analysis revealed a significant reduction in CD19+ B cells in the bone marrow of TIRAP-transplanted mice compared with controls (Fig. 3 a), as has been previously reported in low-risk MDS patients (Sternberg et al., 2005). Interestingly, there was a significant expansion or recruitment of WT (GFP−) T cells in the bone marrow of TIRAP-expressing HSPCs (Fig. 3 a).

Constitutive TIRAP expression disrupts the bone marrow microenvironment, but T and NK cells are not central for TIRAP-mediated BMF. (a) Immunophenotyping of lymphoid lineages from bone marrow (BM) of WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 5) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs 3–4 wk after transplant. Percentage of total HSPCs, as well as the contribution of transduced (GFP+) and competitor cells (GFP−) are represented. Data pooled from two separate transplants. (b) Kaplan–Meier survival curve for NSG mice transplanted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 7) or TIRAP (n = 8); P = 0.001. Data shown are pooled from two separate transplants. (c) WBC counts, RBC counts, and platelet (Plt) counts in peripheral blood from TIRAP-transplanted (n = 7) and vector-transplanted (n = 8) mice at end point. (d) Outline of experimental schema. WT mice were transplanted with TIRAP- or vector-transduced WT HSPCs (CD45.2) and allowed to condition the bone marrow microenvironment for 3 wk. After 3 wk, mice were myeloablated with busulfan. GFP- or YFP-labeled WT HSPCs (CD45.1) were then transplanted into the myeloablated mice and allowed to engraft for 2 wk, after which bone marrow was harvested (vector-conditioned, n = 7; TIRAP-conditioned, n = 7), pooled, and transplanted competitively into new WT transplant recipients (n = 7). (e) GFP and YFP myeloid and B and T cell chimerism in bone marrow from competitive transplants was measured after 11 wk (n = 7). Data pooled from two independent transplants. GM, granulocyte macrophage. (f) Frequency of Lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells (EC), Lin−CD45−Sca-1+CD51+ mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC), and Lin−CD45−Sca-1−CD51+ osteoblastic cells (OBC) from primary transplanted WT mice reconstituted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 7) or vector-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs. Data pooled from three independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

Constitutive TIRAP expression disrupts the bone marrow microenvironment, but T and NK cells are not central for TIRAP-mediated BMF. (a) Immunophenotyping of lymphoid lineages from bone marrow (BM) of WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 5) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs 3–4 wk after transplant. Percentage of total HSPCs, as well as the contribution of transduced (GFP+) and competitor cells (GFP−) are represented. Data pooled from two separate transplants. (b) Kaplan–Meier survival curve for NSG mice transplanted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 7) or TIRAP (n = 8); P = 0.001. Data shown are pooled from two separate transplants. (c) WBC counts, RBC counts, and platelet (Plt) counts in peripheral blood from TIRAP-transplanted (n = 7) and vector-transplanted (n = 8) mice at end point. (d) Outline of experimental schema. WT mice were transplanted with TIRAP- or vector-transduced WT HSPCs (CD45.2) and allowed to condition the bone marrow microenvironment for 3 wk. After 3 wk, mice were myeloablated with busulfan. GFP- or YFP-labeled WT HSPCs (CD45.1) were then transplanted into the myeloablated mice and allowed to engraft for 2 wk, after which bone marrow was harvested (vector-conditioned, n = 7; TIRAP-conditioned, n = 7), pooled, and transplanted competitively into new WT transplant recipients (n = 7). (e) GFP and YFP myeloid and B and T cell chimerism in bone marrow from competitive transplants was measured after 11 wk (n = 7). Data pooled from two independent transplants. GM, granulocyte macrophage. (f) Frequency of Lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells (EC), Lin−CD45−Sca-1+CD51+ mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC), and Lin−CD45−Sca-1−CD51+ osteoblastic cells (OBC) from primary transplanted WT mice reconstituted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 7) or vector-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs. Data pooled from three independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

Although T cells have been suggested to be key mediators of bone marrow cytopenias, these studies have mostly been associative rather than demonstrating direct causation (Gravano et al., 2016; Glenthøj et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2012). To address whether the expansion or recruitment of effector T cells was required for BMF, we transplanted NSG (NOD/scid/gamma) mice, which are deficient in functional T, B, and NK cells, with WT HSPCs transduced with TIRAP or control in the absence of WT competing cells to avoid WT T cell expansion. Similar to WT transplants, NSG mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing HSPCs developed BMF with pancytopenia in a time frame similar to that of WT mice (Fig. 3, b and c), suggesting that T and NK cells are not central to the development of BMF.

To determine whether TIRAP-expressing cells altered the ability of bone marrow stroma to support hematopoiesis, we tested the ability of GFP- or YFP-labeled HSPCs to competitively repopulate WT mice following exposure to TIRAP- or empty vector–conditioned environments (Fig. 3 d and Fig. S1 f). Following a 3-wk conditioning period, bone marrow was myeloablated with busulfan, followed by transplantation of GFP- or YFP-labeled WT HSPCs. After a 2-wk engraftment period, bone marrow collected from TIRAP- and control-conditioned mice were pooled, and one mouse equivalent of the mixed bone marrow was transplanted into lethally irradiated WT recipients. The contribution of GFP+ and YFP+ cells to hematopoietic reconstitution in the bone marrow was determined after 11 wk (Fig. 3 e). The contribution of myeloid cells derived from TIRAP-conditioned bone marrow was significantly impaired compared with that of cells derived from control-conditioned bone marrow (4.1% compared with 95.9%; P < 0.0001). This is consistent with the reduced bone marrow cellularity observed in mice transplanted with HSPCs constitutively expressing TIRAP, suggesting that exposure to TIRAP-expressing cells reduces the capability of the bone marrow microenvironment to support normal hematopoiesis.

HSPCs are dependent on bone marrow stromal cells to provide signals for proliferation, differentiation, and survival (Zambetti et al., 2016; Goedhart et al., 2018), and several studies have implicated stromal abnormalities in the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies (Zambetti et al., 2016; Kode et al., 2014; Raaijmakers et al., 2010). We thus analyzed the composition of the bone marrow microenvironment to determine whether TIRAP expression in HSPCs alters components of the bone marrow microenvironment (Schepers et al., 2012; Fig. S1 g). We found no difference in the percentage of lin−CD45−Sca-1+CD51+ mesenchymal stromal cells or in lin−CD45−Sca-1−CD51+ osteoblast cells derived from TIRAP-transplanted mice compared with controls (Fig. 3 f). However, lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells were found to be reduced by 45% in TIRAP-transplanted mice (Fig. 3 f). Histologic examination of bone marrow sections also showed reduced CD31+ endothelial cells in TIRAP-transplanted bone marrow compared with controls (Fig. S1 h).

Ifnγ drives TIRAP-induced BMF but limits progression to myeloid malignancy

We postulated that the inhibitory effects of constitutive TIRAP expression on endothelial cells may be due to paracrine factors from TIRAP-expressing cells. To identify soluble factors potentially responsible for the effects on endothelial cells and the subsequent BMF following constitutive TIRAP expression, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to compare the transcriptional profiles of TIRAP-expressing and vector-transduced HSPCs. Using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, we identified possible upstream regulators and found several proinflammatory cytokines to be significantly overrepresented (Table S1 a). Of these, the Ifnγ pathway was identified as the most highly activated pathway in TIRAP-transduced compared with control-transduced HSPCs (Table S1 a). Furthermore, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) identified the Ifnγ response as the single most significantly enriched pathway of the Hallmark gene sets (Fig. 4 a). While most of the enriched gene sets represented proinflammatory pathways, the anti-inflammatory cytokine Il10 was also predicted to be an upstream regulator (Table S1 a). GSEA also revealed enrichment in Il10 signaling in TIRAP-transduced HSPCs compared with controls (Fig. 4 b).

Ifnγ signaling is up-regulated following constitutive TIRAP expression in murine HSPCs via a noncanonical pathway. (a and b) Gene set enrichment plots for Ifnγ response (a) and Il10 pathway (b) obtained from RNA-seq analysis of WT HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 3) or vector (n = 3). NES, normalized enrichment score. (c) Validation of cytokine gene expression in vector- and TIRAP-transduced WT HSPCs by RT-qPCR. (d) Correlation between IFNγ gene expression and TIRAP gene expression in low-risk MDS patients; P = 0.0003. (e) Correlation between IL-10 gene expression and TIRAP gene expression in low-risk MDS patients; P = 0.12. Data were analyzed from a previously published microarray dataset (Pellagatti et al., 2006) for plots in panels d and e. (f and g) Structure of WT (f) and TRAF6-DN (g) RT-qPCR for Il10 and Ifnγ following TIRAP overexpression and knockdown of TRAF6 mutant. (h and i) Structure of WT (h) and MyD88-DN mutant (i) RT-qPCR for Il10 and Ifnγ following TIRAP overexpression and knockdown of MyD88. Data pooled from two to four independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

Ifnγ signaling is up-regulated following constitutive TIRAP expression in murine HSPCs via a noncanonical pathway. (a and b) Gene set enrichment plots for Ifnγ response (a) and Il10 pathway (b) obtained from RNA-seq analysis of WT HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 3) or vector (n = 3). NES, normalized enrichment score. (c) Validation of cytokine gene expression in vector- and TIRAP-transduced WT HSPCs by RT-qPCR. (d) Correlation between IFNγ gene expression and TIRAP gene expression in low-risk MDS patients; P = 0.0003. (e) Correlation between IL-10 gene expression and TIRAP gene expression in low-risk MDS patients; P = 0.12. Data were analyzed from a previously published microarray dataset (Pellagatti et al., 2006) for plots in panels d and e. (f and g) Structure of WT (f) and TRAF6-DN (g) RT-qPCR for Il10 and Ifnγ following TIRAP overexpression and knockdown of TRAF6 mutant. (h and i) Structure of WT (h) and MyD88-DN mutant (i) RT-qPCR for Il10 and Ifnγ following TIRAP overexpression and knockdown of MyD88. Data pooled from two to four independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

We verified expression of the predicted upstream regulators of differential gene expression and examined other cytokines previously implicated in the pathogenesis of MDS by quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR). Ifnγ, Il10, Il1b, Il13, and Tnfa transcript levels were all increased in TIRAP-expressing HSPCs (P < 0.05; Fig. 4 c). As Ifnγ and Il10 showed the greatest differential expression and were among the top predicted regulators of global changes in gene expression following constitutive TIRAP expression, we confirmed increased concentration of Il10 and Ifnγ in the conditioned medium of TIRAP-expressing HSPCs (Fig. S2, a and b). As well, we observed increased concentration of Ifnγ in the serum of mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing HSPCs (Fig. S2 c). Of note, in line with previous studies (Pellagatti et al., 2010, 2006; Zeng et al., 2006), we confirmed up-regulation of IFNγ and IFN-stimulated genes in low-risk MDS patients as compared with healthy controls (Fig. S2 d). Further examination of these datasets (Pellagatti et al., 2010, 2006) also showed that the IL10 signature was up-regulated in low-risk MDS patients compared with healthy controls (Fig. S2 e) suggesting clinical significance of these signaling pathways. TIRAP expression was also positively correlated with IFNγ expression in low-risk MDS patients (P = 0.0003; Fig. 4 d), but not with IL10 expression (P = 0.1268; Fig. 4 e).

Constitutive expression of TIRAP induces Ifnγ, Il-10, and Hmgb1; and confirmation of overexpression of TIRAP and RAGE in HSPCs.(a) Concentration of Il10 detected by ELISA in conditioned medium from HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 3) or vector (n = 3) after 24 h of culture. (b) Concentration of Ifnγ detected by ELISA in conditioned medium from HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 3) or vector (n = 3) after 24 h of culture. (c) Concentration of Ifnγ as detected by ELISA in peripheral blood serum from mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 10) or vector-transduced (n = 13) HSPCs at experimental end point. Data from two independent repeats. (d) GSEA analysis of previously published dataset (Pellagatti et al., 2006) showing enrichment of the IFNγ-stimulated genes in low-risk MDS patients compared with healthy controls. NES, normalized enrichment score. (e) GSEA analysis of previously published dataset (Pellagatti et al., 2006) showing enrichment of IL10 pathway genes in low-risk MDS patients compared with healthy controls. (f and g) Granulocyte counts, hemoglobin (Hgb) levels, and platelet (Plt) counts at experimental end point in WT mice transplanted with Ifnγ−/− or Il10−/− HSPCs transduced with vector or TIRAP. Data from three independent transplants. (h) Spleen weight at experimental end point of Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 9) and TIRAP-transduced (n = 6) HSPCs lacking Ifnγr. Data from two independent transplants. (i) Representative images of H&E-stained sections of the spleen of Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced HSPCs lacking Ifnγr show disruption of the splenic structures compared with vector controls. CD11b-stained spleen sections show increase infiltration of myeloid cells in Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced HSPCs lacking Ifnγr compared with vector. Scale bar: 20 µm for 40× magnification. (j) RT-qPCR data showing increased TIRAP expression in NIH3T3 cells transduced with TIRAP and TIRAP-2A-sRAGE vectors compared with vector control. Increased RAGE expression seen in TIRAP-2A-sRAGE–transduced NIH3T3 cells compared with only TIRAP and vector controls. Data pooled from two independent repeats. (k) WT HSPCs transduced with empty vector (n = 4) or TIRAP (n = 5) or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE (n = 6) were sorted for GFP expression and immunoblotted with antibodies against TIRAP and GAPDH. Representative image shown from one of two independent experiments. (l) Concentration of sRAGE detected by ELISA in conditioned medium from HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 5), TIRAP (n = 5), or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE (n = 5) after 24 h of culture. The ELISA was done in three independent repeats. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

Constitutive expression of TIRAP induces Ifnγ, Il-10, and Hmgb1; and confirmation of overexpression of TIRAP and RAGE in HSPCs.(a) Concentration of Il10 detected by ELISA in conditioned medium from HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 3) or vector (n = 3) after 24 h of culture. (b) Concentration of Ifnγ detected by ELISA in conditioned medium from HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 3) or vector (n = 3) after 24 h of culture. (c) Concentration of Ifnγ as detected by ELISA in peripheral blood serum from mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 10) or vector-transduced (n = 13) HSPCs at experimental end point. Data from two independent repeats. (d) GSEA analysis of previously published dataset (Pellagatti et al., 2006) showing enrichment of the IFNγ-stimulated genes in low-risk MDS patients compared with healthy controls. NES, normalized enrichment score. (e) GSEA analysis of previously published dataset (Pellagatti et al., 2006) showing enrichment of IL10 pathway genes in low-risk MDS patients compared with healthy controls. (f and g) Granulocyte counts, hemoglobin (Hgb) levels, and platelet (Plt) counts at experimental end point in WT mice transplanted with Ifnγ−/− or Il10−/− HSPCs transduced with vector or TIRAP. Data from three independent transplants. (h) Spleen weight at experimental end point of Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 9) and TIRAP-transduced (n = 6) HSPCs lacking Ifnγr. Data from two independent transplants. (i) Representative images of H&E-stained sections of the spleen of Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced HSPCs lacking Ifnγr show disruption of the splenic structures compared with vector controls. CD11b-stained spleen sections show increase infiltration of myeloid cells in Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced HSPCs lacking Ifnγr compared with vector. Scale bar: 20 µm for 40× magnification. (j) RT-qPCR data showing increased TIRAP expression in NIH3T3 cells transduced with TIRAP and TIRAP-2A-sRAGE vectors compared with vector control. Increased RAGE expression seen in TIRAP-2A-sRAGE–transduced NIH3T3 cells compared with only TIRAP and vector controls. Data pooled from two independent repeats. (k) WT HSPCs transduced with empty vector (n = 4) or TIRAP (n = 5) or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE (n = 6) were sorted for GFP expression and immunoblotted with antibodies against TIRAP and GAPDH. Representative image shown from one of two independent experiments. (l) Concentration of sRAGE detected by ELISA in conditioned medium from HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 5), TIRAP (n = 5), or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE (n = 5) after 24 h of culture. The ELISA was done in three independent repeats. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData FS2.

The enrichment of IFNγ and IL-10 signaling pathways and the lack of enrichment of the canonical NF-κB pathway in low-risk MDS bone marrow compared with normal (Table S1 a) led us to question whether TIRAP-induced production of Ifnγ and Il10 is via a noncanonical pathway. To address the question of whether TIRAP overexpression induces changes in gene expression through an alternative signaling pathway, we assessed the ability of TIRAP to induce IL-10 and IFNγ following blockade of the TLR pathway downstream of TIRAP at the level of MyD88 and TRAF6. We coexpressed TIRAP or vector control with either a TRAF6 dominant negative (TRAF6-DN) or one of two MyD88-DN constructs (Fig. 4, f–i). The TRAF6-DN construct is a C-terminal construct consisting of the TRAF and coiled-coil domains only (Fig. 4 f). The MyD88-DN constructs used were either an N-terminal deletion consisting of the TIR domain only or a C-terminal deletion comprising the death domain only (Fig. 4 h). Both of these constructs have been shown to function as dominant-negative molecules (Raschi et al., 2003; Hull et al., 2002). We found that blockade of the TLR signaling pathway at the level of either MyD88 or TRAF6 did not inhibit induction of IL-10 or IFNγ, but rather augmented the IL-10 and IFNγ signals (Fig. 4, g and i), suggesting that TIRAP signals through a noncanonical pathway to activate IL-10 and IFNγ production.

To test the functional role of Ifnγ and Il10 in TIRAP-mediated BMF, WT recipient mice were transplanted with TIRAP- or control-transduced HSPCs from Ifnγ−/− or Il10−/− donor mice, along with WT bone marrow cells. Mice that received TIRAP-transduced Ifnγ−/− HSPCs were rescued from BMF, as evidenced by normalized blood cell counts and improved median survival compared with controls (WT TIRAP vs. Ifnγ−/− TIRAP, P = 0.0004; Fig. 5, a and b, compared with Fig. 1 e). In contrast, transplantation of TIRAP-expressing Il10−/− HSPCs did not lead to improvement in blood counts or overall survival (WT TIRAP vs. Il10−/− TIRAP, P = 0.10; Fig. 5, c and d, compared with Fig. 1 e). Median survival for TIRAP-transplanted mice reconstituted with Ifnγ−/− and Il10−/− HSPCs was 48.6 and 27.2 wk, respectively.

TIRAP requires Ifnγ to promote BMF and inhibit progression to myeloid malignancy. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for transplanted WT mice reconstituted with HSPCs from Ifnγ−/− mice transduced with vector (n = 21) or TIRAP (n = 19). WT TIRAP vs. Ifnγ−/− TIRAP, P = 0.0004; Ifnγ−/− TIRAP vs. Ifnγ−/− vector, P = 0.008. Data pooled from four independent transplants. KO, knockout. (b) Complete blood counts from peripheral blood of mice transplanted with Ifnγ−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 3) or vector (n = 5). Data pooled from four independent transplants. Hgb, hemoglobin; Plt, platelets. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for primary transplanted mice reconstituted with HSPCs from Il10−/− mice transduced with vector (n = 20) or TIRAP (n = 18). WT TIRAP vs. Il10−/− TIRAP, P = 0.10; Il10−/− TIRAP vs. Il10−/− vector, P = 0.0001. Data pooled from three independent transplants. (d) Complete blood counts from WT mice transplanted with Il10−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 5) or vector (n = 8). Data pooled from three independent transplants. Survival curves for mice transplanted with WT HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 10) and vector (n = 6) in panels b and d were repeated along with the Ifnγ−/− and Il10−/− transplants. (e)Ifnγ levels as measured by RT-qPCR at experimental end point in transduced (GFP+) myeloid cells (Mac1+ and Gr1+), NK cells (CD49b+), and T cells (CD3+) in the bone marrow of WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 3) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 3) WT HSPCs. (f) Ifnγ levels as measured by ELISA at experimental end point in transduced (GFP+) myeloid cells (Mac1+ and Gr1+), NK cells (CD49b+), and T cells (CD3+) in the bone marrow of WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 3) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 3) WT HSPCs. Data pooled from two independent experiments (e and f). (g) Distribution of the difference in cause of mortality between WT mice transplanted with WT, Il10−/−, and Ifnγ−/− TIRAP-transduced bone marrow. Statistical significance was assessed using χ2 test. (h) GSEA analysis of a previously published dataset (Mills et al., 2009) showing enrichment of the IFNγ signature in MDS patients compared with all AML subtypes. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

TIRAP requires Ifnγ to promote BMF and inhibit progression to myeloid malignancy. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for transplanted WT mice reconstituted with HSPCs from Ifnγ−/− mice transduced with vector (n = 21) or TIRAP (n = 19). WT TIRAP vs. Ifnγ−/− TIRAP, P = 0.0004; Ifnγ−/− TIRAP vs. Ifnγ−/− vector, P = 0.008. Data pooled from four independent transplants. KO, knockout. (b) Complete blood counts from peripheral blood of mice transplanted with Ifnγ−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 3) or vector (n = 5). Data pooled from four independent transplants. Hgb, hemoglobin; Plt, platelets. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for primary transplanted mice reconstituted with HSPCs from Il10−/− mice transduced with vector (n = 20) or TIRAP (n = 18). WT TIRAP vs. Il10−/− TIRAP, P = 0.10; Il10−/− TIRAP vs. Il10−/− vector, P = 0.0001. Data pooled from three independent transplants. (d) Complete blood counts from WT mice transplanted with Il10−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 5) or vector (n = 8). Data pooled from three independent transplants. Survival curves for mice transplanted with WT HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 10) and vector (n = 6) in panels b and d were repeated along with the Ifnγ−/− and Il10−/− transplants. (e)Ifnγ levels as measured by RT-qPCR at experimental end point in transduced (GFP+) myeloid cells (Mac1+ and Gr1+), NK cells (CD49b+), and T cells (CD3+) in the bone marrow of WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 3) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 3) WT HSPCs. (f) Ifnγ levels as measured by ELISA at experimental end point in transduced (GFP+) myeloid cells (Mac1+ and Gr1+), NK cells (CD49b+), and T cells (CD3+) in the bone marrow of WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 3) or TIRAP-transduced (n = 3) WT HSPCs. Data pooled from two independent experiments (e and f). (g) Distribution of the difference in cause of mortality between WT mice transplanted with WT, Il10−/−, and Ifnγ−/− TIRAP-transduced bone marrow. Statistical significance was assessed using χ2 test. (h) GSEA analysis of a previously published dataset (Mills et al., 2009) showing enrichment of the IFNγ signature in MDS patients compared with all AML subtypes. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

As Ifnγ is thought to be produced mainly by T and NK cells (Schoenborn and Wilson, 2007), the lack of requirement for T and NK cells in driving BMF (Fig. 3) was a surprise. We thus examined which cells express Ifnγ following TIRAP expression. This analysis showed that myeloid and NK cells were the cells most responsible for the increased production of Ifnγ (Fig. 5, e and f), suggesting that myeloid-derived Ifnγ is sufficient to drive TIRAP-mediated BMF in NSG mice.

Although survival of mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing Ifnγ−/− HSPCs was extended, these mice still began to die ∼15 wk after transplant (Fig. 5 a). Moribund mice presented with leukocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytopenia (Fig. S2 f). No improvement in overall survival was observed for recipients of Il10−/− HSPCs (Fig. 5 c and Fig. S2 g). In contrast to mice that received TIRAP-transduced Ifnγ−/− HSPCs, there was no significant increase in myeloid expansion in mice that received TIRAP-transduced Il10−/− HSPCs (Fig. 5 g). The significant increase in myeloid expansion in the context of Ifnγ deficiency suggests that Ifnγ plays a role in the suppression of both normal and malignant hematopoiesis and implies that leukemic progression may require suppression of Ifnγ signaling. Indeed, GSEA analysis of gene expression data comparing MDS and AML patients (Mills et al., 2009) showed enrichment of the IFNγ signature in MDS patients compared with all AML patients (Fig. 5 h), suggesting that IFNγ signaling is preferentially up-regulated in MDS and that repression of this pathway may be important for leukemic transformation.

Ifnγ has an indirect effect on bone marrow stromal cells

As IFNs have been shown to be associated with inflammasome formation and pyroptosis (Kopitar-Jerala, 2017), and S100 alarmin-driven BMF has been associated with pyroptosis (Basiorka et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2013; Schneider et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2004; Zambetti et al., 2016), we asked whether pyroptosis was activated in this model, by immunoblotting transduced HSPCs for Caspase-1. Increased levels of Caspase-1 were noted in TIRAP-transduced HSPCs compared with controls, and flow cytometry revealed an increase in activated Caspase-1 in TIRAP-expressing bone marrow cells from TIRAP-transplanted mice compared with controls (Fig. 6, a and b). Caspase-1 activation was mainly observed within the myeloid compartment and was present in both the transduced population and the WT helper cell population (Fig. 6 b). However, deletion of Caspase-1 did not eliminate Ifnγ or Il10 expression (Fig. 6 c). To determine whether the increase in Caspase-1 activation was required for myelosuppression, we constitutively expressed TIRAP or empty vector in Casp1−/− HSPCs and transplanted cells into lethally irradiated Casp1−/− recipient mice. Loss of Caspase-1 did not reverse TIRAP-induced pancytopenia, and mice succumbed to BMF within 4 wk of transplantation, similar to TIRAP-transduced and transplanted WT animals (P = 0.0002 compared with vector controls; Fig. 6, d and e; and Fig. 1 d), suggesting that in this model, pyroptosis may be an epiphenomenon rather than the cause of BMF.

Caspase-1 is not required for TIRAP-induced BMF.(a) Immunoblots for Caspase-1 from WT HSPCs transduced with TIRAP or vector. (b) Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of activated Caspase-1. CD11b+ cells were selected to measure the active Caspase-1 within myeloid populations. Bone marrow from four mice was pooled and analyzed for activated Caspase-1. (c) RT-qPCR measuring Ifnγ and Il10 in Casp1−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 4) or vector (n = 4). (d) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Casp1−/− mice transplanted with Casp1−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 10) or vector (n = 8); P = 0.0002. Data pooled from two independent transplants. (e) Complete blood counts at experimental end point from Casp1−/− mice transplanted with Casp1−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 10) or vector (n = 8). Plt, platelets. *, P ≤ 0.05; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

Caspase-1 is not required for TIRAP-induced BMF.(a) Immunoblots for Caspase-1 from WT HSPCs transduced with TIRAP or vector. (b) Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of activated Caspase-1. CD11b+ cells were selected to measure the active Caspase-1 within myeloid populations. Bone marrow from four mice was pooled and analyzed for activated Caspase-1. (c) RT-qPCR measuring Ifnγ and Il10 in Casp1−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 4) or vector (n = 4). (d) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Casp1−/− mice transplanted with Casp1−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 10) or vector (n = 8); P = 0.0002. Data pooled from two independent transplants. (e) Complete blood counts at experimental end point from Casp1−/− mice transplanted with Casp1−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 10) or vector (n = 8). Plt, platelets. *, P ≤ 0.05; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F6.

To determine whether BMF mediated by TIRAP via Ifnγ was directed through the Ifnγ receptor (Ifnγr), we performed transplants in which Ifnγr−/− recipient mice were transplanted with Ifnγr−/− HSPCs constitutively expressing TIRAP or control, as well as Ifnγr−/− helper cells. Unexpectedly, transplantation of TIRAP-expressing Ifnγr−/− HSPCs resulted in death by 19 wk after transplant (P = 0.0013 compared with vector controls; Fig. 7 a). In contrast to Ifnγ−/− transplants (Fig. 5, a and b), RBC and platelet counts did not improve in mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing Ifnγr−/− HSPCs, although white blood cell (WBC) counts were maintained (Fig. 7 b). The difference between the Ifnγ−/− model and the Ifnγr−/− model may be reconciled based on the continued expression of Ifnγ in the Ifnγr−/− mice, which has been reported to directly interfere with TPO signaling (Alvarado et al., 2019). As noted, similar to the Ifnγ−/− model, deletion of Ifnγr resulted in maintenance of the myeloid population (Fig. 7 b). All Ifnγr−/− mice expressing TIRAP displayed massive splenomegaly (mean spleen weight 239 mg in TIRAP vs. 89 mg in control mice, P = 0.0014) due to myeloid infiltration of the spleen (Fig. S2, h and i). This finding is reminiscent of the myeloproliferation seen in TIRAP transplants using Ifnγ−/− HSPCs above. The absence of Ifnγ-sensitive cells in both donor and recipient mice led to maintenance of the bone marrow endothelial population (Fig. 7 c), suggesting that the reduction seen in the endothelial population in WT mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing HSPCs is due to Ifnγ and that endothelial cells support the myeloid population.

Ifnγ has an indirect effect on bone marrow endothelial cells. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Ifnγr−/− transplanted mice reconstituted with Ifnγr−/− HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 11) or TIRAP (n = 8); P = 0.0013. Data pooled from two independent transplants. (b) Complete blood counts at experimental end point of Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with Ifnγr−/− HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 11) or TIRAP (n = 8). Plt, platelets. (c) Frequency of Lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells from Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 8) or vector-transduced (n = 11) HSPCs. Data pooled from two independent transplants (b and c). (d) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Ifnγr−/− recipient mice reconstituted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 9) or TIRAP (n = 11); P < 0.0001. Data pooled from three independent transplants. (e) Complete blood counts at experimental end point of Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 11) or vector-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs. (f) Frequency of Lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells in Ifnγr−/− recipient mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 11) or vector-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs. Data pooled from two independent transplants (e and f). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

Ifnγ has an indirect effect on bone marrow endothelial cells. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Ifnγr−/− transplanted mice reconstituted with Ifnγr−/− HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 11) or TIRAP (n = 8); P = 0.0013. Data pooled from two independent transplants. (b) Complete blood counts at experimental end point of Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with Ifnγr−/− HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 11) or TIRAP (n = 8). Plt, platelets. (c) Frequency of Lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells from Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 8) or vector-transduced (n = 11) HSPCs. Data pooled from two independent transplants (b and c). (d) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Ifnγr−/− recipient mice reconstituted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 9) or TIRAP (n = 11); P < 0.0001. Data pooled from three independent transplants. (e) Complete blood counts at experimental end point of Ifnγr−/− mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 11) or vector-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs. (f) Frequency of Lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells in Ifnγr−/− recipient mice transplanted with TIRAP-transduced (n = 11) or vector-transduced (n = 9) WT HSPCs. Data pooled from two independent transplants (e and f). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

To test whether Ifnγ was directly responsible for the inhibitory effects on bone marrow endothelial cells, we transplanted Ifnγr−/− recipient mice with WT HSPCs transduced with either TIRAP or control as well as WT helper cells. Surprisingly, these mice had no improvement in overall survival (P < 0.0001 compared with vector controls) and developed BMF characterized by anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia, similar to WT recipients, despite the insensitivity of bone marrow stromal cells to Ifnγ (Fig. 7, d and e). Furthermore, the bone marrow endothelial population was depleted, suggesting an indirect effect of Ifnγ on the bone marrow endothelium (Fig. 7 f).

Hmgb1 acts downstream of Ifnγ to deplete bone marrow endothelium and suppress myelopoiesis independent of pyroptosis

We examined the RNA-seq data comparing TIRAP-expressing HSPCs to vector-transduced HSPCs (Table S2), to identify signaling pathways downstream of Ifnγ that are potentially responsible for the endothelial defect. Although pyroptosis is not a cause of BMF in our model (Fig. 7), we found the Hmgb1 pathway, but not S100A8 or S100A9, to be significantly activated in TIRAP-expressing HSPCs (Fig. 8 a and Table S1 b). We confirmed that Hmgb1 was present in the supernatant of TIRAP-expressing HSPCs 2 d after transduction (Fig. 8 b). To determine whether Hmgb1 was released downstream of Ifnγ, we transduced Ifnγ−/− or WT HSPCs with TIRAP and assayed for Hmgb1 in the supernatant. As shown in Fig. 8 c, Hmgb1 release was blocked in Ifnγ−/− HSPCs expressing TIRAP. On the other hand, Hmgb1 release was not blocked in Casp1−/− HSPCs (Fig. 8 c), suggesting pyroptosis-independent release of Hmgb1 in this model of TIRAP-mediated BMF.

Hmgb1 acts downstream of TIRAP and Ifnγ to deplete bone marrow endothelium and suppress myelopoiesis. (a) GSEA showing enrichment in Hmgb1 signaling in HSPCs expressing TIRAP compared with vector. NES, normalized enrichment score. (b) ELISA for Hmgb1 in supernatant collected from WT HSPCs expressing TIRAP (n = 13) or vector (n = 16). Data pooled from three independent repeats. (c) Relative induction of Hmgb1 in WT, Ifnγ−/−, and Casp1−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 4) or vector (n = 4), as determined by ELISA of supernatant of vector- or TIRAP-transduced cells. Data pooled from two independent experiments. (d) Percent viability of HUVECs after 24-h treatment with Hmgb1 with or without glycyrrhizin. The assay was done on three different HUVEC samples, with each sample repeated three times. (e) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for WT transplanted mice reconstituted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 8), TIRAP (n = 5), or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE (n = 7); TIRAP vs. vector, P = 0.001; TIRAP vs. TIRAP-2A-sRAGE, P = 0.008; TIRAP-2A-sRAGE vs. vector, P = 0.27. Data pooled from three independent transplants. (f–h) Complete blood counts in peripheral blood of WT mice transplanted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector, TIRAP, or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE. Plt, platelets. (i) Frequency of Lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells from WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 8), TIRAP-transduced (n = 5), or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE–transduced (n = 7) HSPCs. Data pooled from three independent transplants (f–i). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

Hmgb1 acts downstream of TIRAP and Ifnγ to deplete bone marrow endothelium and suppress myelopoiesis. (a) GSEA showing enrichment in Hmgb1 signaling in HSPCs expressing TIRAP compared with vector. NES, normalized enrichment score. (b) ELISA for Hmgb1 in supernatant collected from WT HSPCs expressing TIRAP (n = 13) or vector (n = 16). Data pooled from three independent repeats. (c) Relative induction of Hmgb1 in WT, Ifnγ−/−, and Casp1−/− HSPCs transduced with TIRAP (n = 4) or vector (n = 4), as determined by ELISA of supernatant of vector- or TIRAP-transduced cells. Data pooled from two independent experiments. (d) Percent viability of HUVECs after 24-h treatment with Hmgb1 with or without glycyrrhizin. The assay was done on three different HUVEC samples, with each sample repeated three times. (e) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for WT transplanted mice reconstituted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector (n = 8), TIRAP (n = 5), or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE (n = 7); TIRAP vs. vector, P = 0.001; TIRAP vs. TIRAP-2A-sRAGE, P = 0.008; TIRAP-2A-sRAGE vs. vector, P = 0.27. Data pooled from three independent transplants. (f–h) Complete blood counts in peripheral blood of WT mice transplanted with WT HSPCs transduced with vector, TIRAP, or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE. Plt, platelets. (i) Frequency of Lin−CD45−CD31+ endothelial cells from WT mice transplanted with vector-transduced (n = 8), TIRAP-transduced (n = 5), or TIRAP-2A-sRAGE–transduced (n = 7) HSPCs. Data pooled from three independent transplants (f–i). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

To study the role of Hmgb1 in endothelial cell depletion, we treated human endothelial cells with either Hmgb1 alone or Hmgb1 and its inhibitor, glycyrrhizin. There was a significant reduction in the viability of the Hmgb1-treated endothelial cells by 24 h compared with PBS-treated (control) cells (P = 0.008; Fig. 8 d). Treatment with glycyrrhizin restored the viability of the endothelial cells (P = 0.009 compared with HMGB1 treatment; Fig. 8 d), implicating a cytotoxic effect of Hmgb1 on endothelial cells.

Finally, to study the in vivo effects of blocking Hmgb1, we overexpressed the soluble form of RAGE, an Hmgb1 receptor, and TIRAP within the same construct (TIRAP-2A-sRAGE). The overexpressed sRAGE acts as a decoy receptor for the Hmgb1 produced by TIRAP expression (Geroldi et al., 2006; Kalea et al., 2011). We transplanted WT recipient mice with WT HSPCs transduced with TIRAP, TIRAP-2A-sRAGE, or vector control, as well as WT helper cells (Fig. S2, j–l). By 4 wk after transplant, WBC, RBC, and platelet counts were low in mice expressing TIRAP, which resulted in mortality by 10 wk after transplant (Fig. 8, e–h) On the other hand, mice with TIRAP-2A-sRAGE–expressing HSPCs had rescued WBC, RBC, and platelet counts comparable to vector controls, resulting in rescued survival of these mice (Fig. 8, e–h). However, the peripheral blood counts at 28 wk after transplant were similar to those of the Ifnγr−/− transplants (Fig. 7, a and b), with WBC counts remaining at levels similar to controls and reduced RBC and platelet counts (Fig. 8, f–h). This finding supports the indirect role of Ifnγ via Hmgb1 on myeloid, but not erythroid or megakaryocytic, suppression. Further, blocking Hmgb1 by sRAGE expression led to maintenance of the bone marrow endothelial population (Fig. 8 i) suggesting that the reduction seen in the endothelial population in WT mice transplanted with TIRAP-expressing HSPCs is due to the increase in Hmgb1 expression and that endothelial cells support the myeloid population in this model.

Discussion

Dysregulation of the immune system has been reported in all subtypes of MDS (Lam et al., 2018). Aberrant activation of various components of the innate immune pathway, such as TLRs and IRAK1, has been implicated in altering normal hematopoiesis (Rhyasen et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2013; Varney et al., 2015). In this study, we show that aberrant expression of the innate immune adaptor protein TIRAP dysregulates normal hematopoiesis. The constitutive expression of TIRAP in HSPCs has non–cell-autonomous effects on other HSPCs and the microenvironment, leading to the development of BMF, characterized by myeloid, megakaryocytic, and erythroid suppression. Based on our results, we propose a model of BMF in which aberrant TIRAP overexpression in hematopoietic cells releases Ifnγ, which indirectly suppresses myelopoiesis through the release of the alarmin, Hmgb1, but directly impacts on megakaryocyte and erythroid production. Hmgb1 disrupts the bone marrow endothelial compartment which suppresses myelopoiesis. Thus, TIRAP-Ifnγ-Hmgb1–mediated BMF is due to two different mechanisms, and contrary to current dogma, both mechanisms are independent of T cell function or pyroptosis.

Previous studies have focused on immune and inflammatory activation of canonical TLR4–TRAF6–NF-κB activation in MDS (Starczynowski et al., 2010; Rhyasen et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2013). Activation of TRAF6, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, has been shown to account for neutropenia and thrombocytosis as well as progression to AML (Starczynowski et al., 2010). In del(5q) MDS, the up-regulation of TRAF6 is due to haploinsufficiency of miR-146a, located on the long arm of chromosome 5. However, miR-146a is lost in only about half of patients with del(5q) MDS (Lam et al., 2018), as it is not located in the minimally deleted region. In contrast, miR-145 is present within the commonly deleted region of chromosome 5q that is universally deleted in del(5q) MDS (Starczynowski et al., 2010). TIRAP, a target of miR-145, lies upstream of TRAF6 and is required for TLR2- and TLR4-dependent activation of TRAF6 (Starczynowski et al., 2010). Interestingly our data show that TIRAP activates Ifnγ but not Il6, independent of functional MyD88 and TRAF6. TRAF6 expression, on the other hand, induces Il6 but not Ifnγ (Starczynowski et al., 2010), suggesting that BMF induced by constitutive TIRAP expression is independent of canonical TRAF6–NF-κB–mediated signaling. Further, while TRAF6 overexpression leads to leukemia in half of cases (Starczynowski et al., 2010), constitutive TIRAP expression does not cause myeloproliferation unless Ifnγ is blocked.

Dysregulation of the bone marrow microenvironment due to genetic aberrations in stromal cells has been shown to lead to ineffective communication between HSCs and the surrounding microenvironment, contributing to the inability of the bone marrow to sustain normal hematopoiesis (Zambetti et al., 2016; Schepers et al., 2015). In line with these studies, we demonstrate the role of the bone marrow microenvironment specifically in maintaining normal myelopoiesis. Interestingly, in our model, we do not see any effect on mesenchymal stromal cells and osteoblasts. Rather, we see a reduction in the endothelial cell component of the microenvironment. HSCs have been shown to reside in close proximity to the bone marrow sinusoidal endothelium, and endothelial cells are essential for the maintenance of HSCs and promoting normal hematopoiesis (Kiel et al., 2005; Ramalingam et al., 2017). Consistent with previous data, our results demonstrate the crucial role that endothelial cells play in supporting the myeloid population within the bone marrow (Ziyad et al., 2018).

IFNγ is known to play a role in HSC development (de Bruin et al., 2013; Morales-Mantilla and King, 2018) and has been implicated in the pathophysiology of BMF syndromes (Smith et al., 2016; Hemmati et al., 2017). A previous study has shown that IFNγ augments the expression of Fas and other proapoptotic genes and causes destruction of hematopoietic cells via Fas-mediated apoptosis (Chen et al., 2015). This study suggested that the destruction of functionally active HSCs, upon exposure to IFNγ, is immune mediated through activated cytotoxic T cells (Chen et al., 2015). Additionally, it has been suggested that immune-mediated destruction of HSCs leads to BMF in aplastic anemia (Medinger et al., 2018). However, in the current study in the context of immune-deficient NSG mice, the lack of functional T, B, and NK cells did not attenuate TIRAP-mediated BMF. In our model, BMF, although mediated by IFNγ, is not solely due to T cell–mediated immune destruction of the HSPCs, suggesting a context-dependent role of IFNγ in regulating hematopoiesis. We cannot rule out that T cells are involved in BMF, but our data suggest that they are not central in this model, as Ifnγ derived from myeloid cells is sufficient to drive the phenotype.

Adding to the pleiotropic role of IFNγ, the negative impact of IFNγ on HSPC survival and proliferation has also been attributed to the direct interaction of IFNγ with TPO and possibly erythropoietin (Alvarado et al., 2019). IFNγ was shown to bind to TPO and perturb TPO–c-MPL interactions, thereby inhibiting TPO-induced signaling pathways (Alvarado et al., 2019). TPO is known to promote megakaryocytic and erythroid differentiation (Ng et al., 2012). Thus, the interaction of IFNγ with TPO may explain the lack of rescue in RBC and platelet counts in TIRAP-transplanted mice that lack the Ifnγ receptor.

While Ifnγ appears to directly affect the erythroid and megakaryocyte populations, we noted an indirect effect on the endothelial population of the bone marrow microenvironment. This indirect effect occurs via Hmgb1, which we show to be elaborated downstream of Ifnγ. Hmgb1 is a nonhistone chromatin binding protein and a member of the alarmin family (Yasinska et al., 2018; He et al., 2017). It is known to function as a mediator of inflammatory processes by binding to its receptors, including RAGE, and a subset of TLRs (Ng et al., 2012). HMGB1 has been shown to be present in MDS bone marrow plasma at greater than three times the levels seen in normal bone marrow plasma (Kam et al., 2019; Velegraki et al., 2013), which is similar to the levels seen in the TIRAP model presented here, providing functional relevance to the role of HMGB1 in BMF syndromes. Alarmins, in particular S100A8 and S100A9, have been shown to direct NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated activation of Caspase-1, which has been suggested to lead to pyroptotic cell death of HSPCs in MDS (Basiorka et al., 2016). This mechanism has been proposed to be non–cell-autonomous, where S100A9 in “nonmalignant” myeloid-derived suppressor cells activates inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis of HSPCs in MDS (Basiorka et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2013). However, S100A8 and S100A9 have also been shown to cause an erythroid differentiation defect in Rps14-haploinsufficient HSPCs in a cell-autonomous manner (Schneider et al., 2016). Although HMGB1 has been shown to be present at high levels in MDS bone marrow plasma, the role of this alarmin in the disease phenotype has not been studied (Kam et al., 2019; Velegraki et al., 2013). Our data with TIRAP-induced BMF suggests that Caspase-1–mediated pyroptosis is not a driving factor for the observed BMF, as TIRAP expression in Casp1−/− cells did not rescue TIRAP-induced BMF or mortality. Rather, our findings suggest that Ifnγ-stimulated Hmgb1 release occurs in different cell types in a cell-autonomous and non–cell-autonomous manner. Thus, although Hmgb1 is involved in mediating BMF, activation of Caspase-1 is likely an epiphenomenon that is not causative of the BMF seen in this model.

The current study highlights a noncanonical effect of aberrant TIRAP expression on the endothelial cell component of the bone marrow microenvironment. We further show a non–cell-autonomous and nonpyroptotic role of the alarmin Hmgb1 on the bone marrow endothelial compartment, which results in myelosuppression. As Hmgb1 is a targetable molecule (He et al., 2017; Kam et al., 2019), further understanding of the mechanisms by which it affects endothelial cells and myelopoiesis would open up avenues for developing new therapies for BMF.

Materials and methods

Mice

Pep3b (Ly5.1), C57Bl/6J-TyrC2J (Ly5.2), and NSG (NOD scid gamma–NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) mice were originally obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and were bred and maintained at the Animal Resource Centre of the British Columbia Cancer Research Centre. Ifnγ−/− (B6.129S7-Ifngtm1Ts/J; stock #002287), Il-10−/− (B6.129P2-Il10tm1Cgn/J; stock#002251), Casp1−/− (B6N.129S2-Casp1tm1Flv/J; stock#016621), and Ifnγr−/− mice (B6.129S7-Ifngr1tm1Agt/J; stock #003288) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All strains were maintained in-house at the BC Cancer Research Centre Animal Resource Centre.

Retroviral vectors and packaging cell lines

Flag-TIRAP was PCR amplified from pCMV2-flag-TIRAP (a gift from Ruslan Medzhitov, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD). The amplified Flag-TIRAP was cloned into the MSCV-IRES-GFP (MIG) retroviral vector (plasmid 20672; Addgene). To clone the TIRAP-2A-sRAGE construct, Flag-TIRAP was cloned into the pIRES vector (631605; Clontech). The IRES sequence in the pIRES vector was replaced with the E2A sequence encoding a self-cleaving peptide that was PCR amplified from pWpT-E2A-EGFP (Martinez-Høyer et al., 2020). The E2A sequence was followed by soluble RAGE, which was PCR amplified from the pcDNA3.1-RAGE construct (plasmid 71435; Addgene) using primers designed against the extracellular domain of RAGE protein. The final TIRAP-2A-sRAGE was then cloned in front of the IRES-GFP sequence in the MIG retroviral vector.

Virus packaging and infection of ecotropic packaging cell lines (GP+E86) was performed as previously described (Starczynowski et al., 2010) to obtain stable MIG-TIRAP and MIG-TIRAP-2A-sRAGE lines. Sequencing information confirmed the expression of human TIRAP isoform b in the MIG-TIRAP and the extracellular domain of RAGE in MIG-TIRAP-2A-sRAGE constructs and cell lines.

Bone marrow transplants

8–12-wk-old donor mice were injected i.v. with 5-fluorouracil (150 mg/kg), and bone marrow was harvested after 4 d. Bone marrow cells were retrovirally transduced with MIG or MIG-TIRAP, and GFP+ cells were sorted. Lethally irradiated (810 rad) recipient mice were transplanted i.v. with 300,000 GFP+ cells and 100,000 nontransduced helper cells. Irradiated mice were given ciprofloxacin/HCl in the drinking water for 1 mo following transplantation. Peripheral blood counts were determined at 4-wk intervals using the scil Vet abc Blood Analyzer. When mice became moribund, as defined by the Animal Resource Center rules, they were sacrificed and processed to obtain peripheral blood via cardiac puncture, bone marrow, and spleen at end point.

Niche conditioning transplants

Bone marrow transplants were performed as described above. After 3 wk of bone marrow conditioning, 50 mg/kg of busulfan was administered i.p. over 2 d, and mice were allowed to recover from weight loss for 2 d following the last injection. 200,000 GFP- or YFP-labeled WT bone marrow cells, along with 100,000 helper cells, were then injected i.v. into mice with TIRAP- or MIG-preconditioned bone marrow. GFP- and YFP-expressing cells were allowed to engraft for 2 wk. Marrow cells were then collected from the TIRAP- and MIG-conditioned mice and mixed together, and one mouse-equivalent of bone marrow was transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients. GFP and YFP chimerism in the peripheral blood was then monitored.

Flow cytometry

For immunophenotypic analysis, bone marrow cells were washed and resuspended in PBS containing 2% calf serum, followed by primary monoclonal antibody (PE- or allophycocyanin-labeled) staining overnight, followed by analysis on a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Specific antibodies used are detailed in Table S3 a. Cells were analyzed on a BD FACS Aria III.

Apoptosis assay

For Annexin V staining, 2 × 105 cells were washed in PBS and resuspended in 100 µl Annexin V binding buffer (10 mM Hepes, 140 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and allophycocyanin-conjugated Annexin V (1:50), and propidium iodide (1:1,000) was added. Following 15-min incubation, an additional 200 µl Annexin V binding buffer was added, and samples were analyzed by flow cytometry.

BrdU proliferation assay

The in vitro BrdU assays were performed on 5-fluorouracil–treated bone marrow cells, which were transduced with either TIRAP or vector control construct. To measure BrdU incorporation in vitro, the transduced cells were serum starved overnight in DMEM + 2% FBS, followed by a media change to DMEM + 10% FBS, and were treated with BrdU (1 µM) for 4 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized using the BD cytofix/cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization solution kit. BrdU incorporation was measured by flow cytometry using eBiosciences BrdU Flow kit according to the manufacturer’s directions. To measure in vivo BrdU incorporation, we transduced 5-fluorouracil–treated bone marrow cells with either TIRAP or vector control and transplanted the transduced cells into recipient mice. Bone marrow cells were harvested from the mice at end point, and BrdU incorporation was measured as outlined above for the in vitro measurement by gating on CD45+ cells.

Immunohistochemistry

The pelvic bone was collected from mice at end point and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. The bone was decalcified for 48 h at 4°C using 15% EDTA. The fixed and decalcified bones were embedded in paraffin and sectioned on slides. The bone sections were stained with CD31 antibody (JC70A) and/or H&E on the Dako OMNIS automated platform.

RT-qPCR

RNA was isolated from bone marrow cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) or TRIzol (Invitrogen). cDNA was prepared using SuperScriptII (Invitrogen) and amplified using PowerSybr Green Master (Applied Biosystems) and HT7900 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) per manufacturer specifications. Primers used are detailed in Table S3 b. GAPDH or hHPRT served as reference control, and differences in mRNA expression levels were calculated as fold-changes by the ΔΔCt method (Ct, cycle threshold).

ELISA

We plated TIRAP- or vector-transduced bone marrow cells at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml in serum-free DMEM supplemented with 1% BSA and cultured them overnight. We recovered the supernatants, and centrifuged (3,500 rpm, 5 min) and assayed them for Ifnγ, Il10, and Hmgb1. Serum from peripheral blood collected at end point from mice transplanted with TIRAP- or vector-transduced HSPCs was used to measure Ifnγ. Mouse IL-10 ELISA Ready-Set-Go!, Mouse IFNγ "Femto-HS" High Sensitivity ELISA, and HMGB1 ELISA kits from eBioscience were used according to manufacturer’s instructions. Similarly, overnight-conditioned medium was collected from 106 bone marrow cells transduced with TIRAP, TIRAP-2A-sRAGE, or vector control to perform ELISA to detect soluble RAGE (sRAGE) using the Human RAGE Quantikine ELISA kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Homing assay

3 × 105 retrovirally transduced bone marrow cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice. Mice were euthanized 22 h after transplant, and GFP content was analyzed by flow cytometry. The total number of transduced GFP+ bone marrow cells was determined. Homing efficiency of progenitor cells was determined by comparing the proportion of GFP+ colonies formed in a colony-forming assay before transplantation and 22 h after transplantation. GFP+ colonies were counted using an Axiovert S100 fluorescent microscope (Zeiss). Homing efficiency was calculated using the following formula:

Endothelial cell cytotoxicity assay

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were grown in MCDB131 medium supplemented with 20% FBS, 50 µg/ml heparin, and 50 µg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement. 8 × 104 HUVECs were seeded in 200 µl of minimal medium (MCDB 131 supplemented with insulin, sodium selenite, transferrin, and 0.1% BSA) in 96-well plates, 24 h before starting treatment. To measure the cytotoxic effect of HMGB1, HUVECs were treated with 200 ng/ml HMGB1 or 200 ng/ml HMGB1 + 500 µg/ml glycyrrhizin (inhibitor of HMGB1) or PBS (as control) in minimal medium. After 24 h of treatment, cell viability was measured by adding 44 µM of resazurin solution to the wells and incubating for 4 h. Fluorescence was measured at 560-nm excitation. Percentage viability was calculated as

RNA-seq

Total RNA samples were checked using Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA nanochip or Caliper GX HT RNA LabChip. Samples that passed quality check were arrayed into a 96-well plate. Next, polyA+ RNA was purified using the 96-well MultiMACS mRNA isolation kit on the MultiMACS 96 separator (Miltenyi Biotec) from total RNA with on-column DNaseI treatment per the manufacturer’s instructions. The eluted polyA+ RNA was ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 10 µl of diethyl pyrocarbonate–treated water with 1:20 SuperaseIN (Life Technologies). Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized from the purified polyA+ RNA using the Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and random hexamer primers. Quality-passed cDNA plate was fragmented by Covaris LE220 for 2 × 65 s at a duty cycle of 30%. The paired-end sequencing library was prepared following the BCCA Genome Sciences Center paired-end library preparation plate-based library construction protocol on a Biomek FX robot (Beckman-Coulter). Briefly, the cDNA was subject to end repair and phosphorylation by T4 DNA polymerase, Klenow DNA Polymerase, and T4 polynucleotide kinase in a single reaction, followed by cleanup using magnetic beads and 3′ A-tailing by Klenow fragment (3′ to 5′ exo minus). After cleanup, adapter ligation was performed. The adapter-ligated products were purified using magnetic beads, then UNG digested and PCR amplified with Phusion DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Illumina’s PE primer set in a single reaction, with cycle conditions 37°C for 15 min and 98°C for 1 min followed by 13 cycles of 98°C for 15 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, and finally 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were purified and size selected using magnetic beads, checked with Caliper LabChip GX for DNA samples using the High Sensitivity Assay (PerkinElmer), and quantified with the Quant-iT dsDNA HS Assay Kit using Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen). Libraries were normalized and pooled. The final concentration was double checked and determined by Qubit dsDNA HS Assay for Illumina Sequencing. The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through accession no. GSE172147.

Gene expression and pathway analysis

RNA-seq data were aligned using JAGuaR (v2.0.3), using the mm10 reference. RNA-SeQC (DeLuca et al., 2012) was used to gather quality metrics for the RNA-seq libraries. Expression quantification was performed with sailfish (v0.6.2; Patro et al., 2014) using RefSeq gene models. Both isoform- and gene-specific quantifications were generated, and raw estimated counts as well as transcripts per million estimates were used in downstream analysis. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (v1.10.1; Love et al., 2014), using a false discovery rate–adjusted P value cutoff of 0.1 to identify differentially expressed genes between the two groups.