Stem cells are maintained in vivo by short-range signaling systems in specialized microenvironments called niches, but the molecular mechanisms controlling the physical space of the stem cell niche are poorly understood. In this study, we report that heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans (HSPGs) are essential regulators of the germline stem cell (GSC) niches in the Drosophila melanogaster gonads. GSCs were lost in both male and female gonads of mutants deficient for HS biosynthesis. dally, a Drosophila glypican, is expressed in the female GSC niche cells and is responsible for maintaining the GSC niche. Ectopic expression of dally in the ovary expanded the niche area, showing that dally is required for restriction of the GSC niche space. Interestingly, the other glypican, dally-like, plays a major role in regulating male GSC niche maintenance. We propose that HSPGs define the physical space of the niche by serving as trans coreceptors, mediating short-range signaling by secreted factors.

Introduction

Understanding how cells receive positional information during tissue assembly and maintenance is a central problem in cell and developmental biology. Spatially controlled extracellular signals can convey this positional information in distinct ways. For example, in a morphogen system, cells in a tissue receive the same signal but in different amounts; this modulation of signal dosage in turn specifies distinct cell fates. In the stem cell niche, a signal is delivered only to cells within a specialized microenvironment, giving them the characteristics of stemness. The mechanism that spatially restricts this signaling and thus defines the physical space of the stem cell niche remains to be elucidated.

The Drosophila melanogaster gonadal niches provide excellent models to investigate how stem cell niches are regulated in vivo. In the Drosophila ovary, germline stem cells (GSCs) are located at the anterior edge of the germarium, directly contacting somatic niche cells called cap cells. The cap cells produce decapentaplegic (Dpp), which regulates GSC maintenance by repressing a target gene, bag of marbles (bam), in GSCs (Xie and Spradling, 1998; Chen and McKearin, 2003; Song et al., 2004). After a GSC divides asymmetrically, Dpp represses bam expression in the daughter cell contacting the cap cells, which will remain a GSC (Deng and Lin, 1997; Xie et al., 2005). In the other daughter cell, which has lost contact with the cap cells, Dpp signaling is not activated, and bam directs differentiation into a cystoblast.

The GSC niche is formed at earlier developmental stages (Zhu and Xie, 2003; Asaoka and Lin, 2004). GSCs are derived from primordial germ cells (PGCs) in the embryonic gonads, which proliferate during larval and pupal stages. At the anterior edge of the early pupal ovary, the cap cells differentiate and secrete Dpp, which represses bam expression in the anterior PGCs (Zhu and Xie, 2003). Dpp thus prevents differentiation of the PGCs in close proximity to the cap cells, allowing them to become GSCs. Eventually, only PGCs directly contacting the cap cells will be GSCs in the adult ovary. Although Dpp is a secreted molecule, in this context, it mediates short-range or contact-dependent signaling in both the pupal and adult stages. The mechanism that spatially limits Dpp signaling and therefore the size of the niche is unknown.

The male GSC niche is controlled by a fundamentally similar mechanism to that of the female GSC niche but by different molecular pathways. At the apical tip of the testis, a group of somatic cells, the hub cells, directly contacts the GSCs and creates a GSC niche. Hub cells produce a secreted ligand, Unpaired (Upd), which activates Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling in adjacent GSCs to control their self-renewal (Kiger et al., 2001; Tulina and Matunis, 2001). A bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)–like ligand, Glass-bottom boat (Gbb), is also critical for GSC maintenance (Kawase et al., 2004).

In many stem cell systems, short-range niche signals are governed by secreted molecules that also serve as long-range morphogens. Interestingly, many such signaling molecules are heparan sulfate (HS)–dependent factors, suggesting that HS proteoglycans (HSPGs) might control niche signals. HSPGs serve as coreceptors for many growth factors and morphogens, including BMPs, Wnts, Hedgehog, and FGFs (Kirkpatrick and Selleck, 2007). In general, HSPGs regulate growth factor signaling in the signal-receiving cells (as canonical coreceptors). In some specific cases, HS expressed by adjacent cells enhances signaling in trans (Kramer and Yost, 2002; Jakobsson et al., 2006), although the general biological significance of HSPGs as trans coreceptors needs to be determined. In this study, we investigate the role of HSPGs in the Drosophila GSC niches. We propose a model in which the differential activities of HS-dependent factors in long- and short-range signaling can be achieved, at least partly, by the differential (canonical and trans coreceptor) activities of HSPGs.

Results and discussion

dally regulates maintenance of the female GSC niche

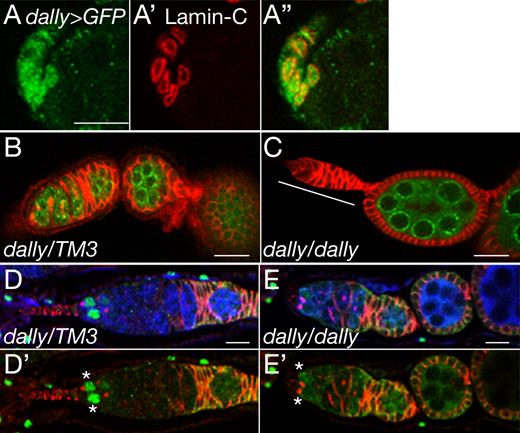

As a first step to study the role of HSPGs in the female GSC niche, we determined expression patterns of two glypican genes, dally and dally-like (dlp), in the adult ovary using enhancer-trap lines. We detected highly specific dally enhancer-trap expression in the anterior-most part of germarium (Fig. 1). These dally-positive cells had nuclei with a flattened shape, directly contacted GSCs, and expressed lamin C, which is a marker for the cap cells (Fig. 1, A–A″; Xie and Spradling, 2000). Based on these characteristics, we concluded that the dally-expressing cells are the cap cells that support the GSC niche. Expression of dlp was not detectable in the cap cells (unpublished data).

dally mutant ovarioles contain empty germaria. (A–A″) dally expression in the cap cells. dally enhancer-trap expression (dally-Gal4 UAS-GFP) is shown in green (A and A″). Cap cells are stained with anti–lamin C antibody (red; A′ and A″). (B and C) dally heterozygous (B) and homozygous (C) ovarioles stained with anti-Hts (red) and anti-Vas (green) antibodies. An empty germarium is marked by the white line. (D–E′) Dpp signaling in dally mutant germarium. Dpp signaling monitored by dad-lacZ expression (green) in dally heterozygous (D and D′) and homozygous (E and E′) germaria. Germline cells and the spectrosome/fusome are labeled with anti-Vas (blue) and anti-Hts (red) antibodies, respectively (see Materials and methods). In dally mutants, dad-lacZ signals were markedly decreased in 30% of the most anterior germ cells (asterisks). See also Fig. S1 B. Anterior is to the left. Bars, 10 µm.

dally mutant ovarioles contain empty germaria. (A–A″) dally expression in the cap cells. dally enhancer-trap expression (dally-Gal4 UAS-GFP) is shown in green (A and A″). Cap cells are stained with anti–lamin C antibody (red; A′ and A″). (B and C) dally heterozygous (B) and homozygous (C) ovarioles stained with anti-Hts (red) and anti-Vas (green) antibodies. An empty germarium is marked by the white line. (D–E′) Dpp signaling in dally mutant germarium. Dpp signaling monitored by dad-lacZ expression (green) in dally heterozygous (D and D′) and homozygous (E and E′) germaria. Germline cells and the spectrosome/fusome are labeled with anti-Vas (blue) and anti-Hts (red) antibodies, respectively (see Materials and methods). In dally mutants, dad-lacZ signals were markedly decreased in 30% of the most anterior germ cells (asterisks). See also Fig. S1 B. Anterior is to the left. Bars, 10 µm.

To test whether dally participates in GSC maintenance, we examined dally mutant ovarioles. In control animals, each germarium contained two or three GSCs with a mean number of 2.6 (n = 75). dally mutant ovarioles had significantly fewer GSCs (mean = 1.8; n = 77; significance: P < 0.005). Strikingly, 14% of these ovarioles had a germarium with no germ cells (Fig. 1 C). This so-called “empty germarium” phenotype results from failure of GSC maintenance (Xie and Spradling, 1998; Ward et al., 2006). Ovarioles with an empty germarium are likely to be lost from the ovary over time; as a result, dally mutants have fewer ovarioles, and this phenotype becomes more severe with age (Fig. S1 A). Collectively, the dally mutant phenotypes suggest that Dally regulates GSC niche maintenance.

To determine whether dally controls Dpp signaling in the ovary, we used the reporter dad-lacZ (Tsuneizumi et al., 1997). In a control germarium, GSCs showed high levels of dad-lacZ expression (Fig. 1, D and D′). In contrast, no signal was detected in 30% of the most anterior germ cells directly contacting the somatic niche cells in dally mutant germaria (Fig. 1, E and E′; and Fig. S1 B), demonstrating that Dpp signaling is severely impaired in the mutants. Staining for Dpp protein revealed that dally mutations reduced Dpp signaling without affecting the ligand expression (Fig. S2, A–B′′′). Remarkably, Dpp protein levels in somatic cells were normal even in an empty germarium (Fig. S2, C–D′). These observations strongly suggest that dally is required for Dpp signal transduction to properly maintain the GSC niche.

dally is required for the establishment of the female GSC niche

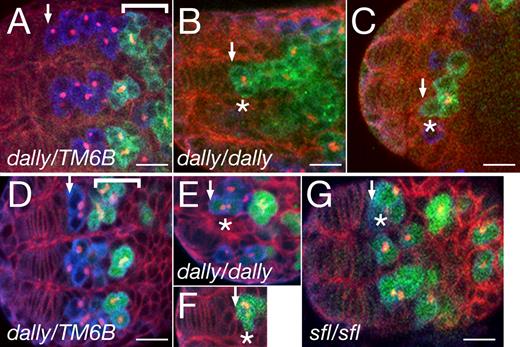

We next asked whether dally is involved in GSC formation at earlier developmental stages. From the third instar larval to pupal stages, like in the adult ovary, dally enhancer-trap expression was detected in somatic niche cells (Fig. S3, B and B′). At the early pupal stage, bam expression was repressed in the anterior PGCs of control animals (Fig. 2, A and D). In contrast, in dally mutant ovaries, the most anterior PGCs abutting the somatic cells expressed bam and had branched fusomes (Fig. 2, B, C, E, and F). Both phenotypes are characteristic of differentiating germ cells (Xie et al., 2005). This premature differentiation of PGCs in dally mutant ovaries suggests that Dally is involved in the formation of the niche, which maintains PGCs in an undifferentiated state.

dally regulates formation of the female GSC niche in the pupal ovary. (A) Early pupal ovary from a dally heterozygous female. Background staining with anti-Hts (red) outlines developing somatic cells in the anterior. PGCs are labeled by anti-Vas antibody (blue). More posteriorly, germ cells start to differentiate (bracket) and express Bam protein (detected by anti-Bam antibody; green). The fusome is stained with anti-Hts. (B and C) Two examples of dally homozygous early pupal ovaries stained with anti-Bam antibody. The most anterior PGCs (asterisks) express Bam protein (green). (D–F) bam expression was also examined using a bam-GFP reporter (green) in dally heterozygous (D) and homozygous (E and F) ovaries. Weak (E) and strong (F) bam-GFP signals were detected in the most anterior PGCs (asterisks). The bracket (D) indicates Bam-positive differentiating germ cells. (G) bam-GFP expression in a sfl mutant ovary. Premature expression of bam in the most anterior PGCs occurred in 20% and 86% of dally and sfl pupal ovaries, respectively. The asterisk indicates the most anterior PGCs. See also Fig. S1 C. (A–G) Arrows indicate the anterior edge of the germ cell population. Anterior is to the left. Bars, 10 µm.

dally regulates formation of the female GSC niche in the pupal ovary. (A) Early pupal ovary from a dally heterozygous female. Background staining with anti-Hts (red) outlines developing somatic cells in the anterior. PGCs are labeled by anti-Vas antibody (blue). More posteriorly, germ cells start to differentiate (bracket) and express Bam protein (detected by anti-Bam antibody; green). The fusome is stained with anti-Hts. (B and C) Two examples of dally homozygous early pupal ovaries stained with anti-Bam antibody. The most anterior PGCs (asterisks) express Bam protein (green). (D–F) bam expression was also examined using a bam-GFP reporter (green) in dally heterozygous (D) and homozygous (E and F) ovaries. Weak (E) and strong (F) bam-GFP signals were detected in the most anterior PGCs (asterisks). The bracket (D) indicates Bam-positive differentiating germ cells. (G) bam-GFP expression in a sfl mutant ovary. Premature expression of bam in the most anterior PGCs occurred in 20% and 86% of dally and sfl pupal ovaries, respectively. The asterisk indicates the most anterior PGCs. See also Fig. S1 C. (A–G) Arrows indicate the anterior edge of the germ cell population. Anterior is to the left. Bars, 10 µm.

HS biosynthesis is required for female GSC niche formation

To determine whether Dally’s role in GSC niche formation depends on HS modifications, we examined pupal ovaries in HS-deficient animals. We used two mutations to disrupt HS biosynthesis, tout-velu (ttv) and sulfateless (sfl). Mutants for ttv, which encodes an HS copolymerase, have no detectable HS (Toyoda et al., 2000). sfl encodes HS N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase, which catalyzes the first step of HS biosynthesis essential for subsequent modifications of HS chains (Toyoda et al., 2000). We found that the HS-deficient mutants showed phenotypes similar to, but more severe than, those of dally mutants (Fig. 2 G and Fig. S1 C). In 86% of sfl mutant pupal ovarioles, the most anterior PGCs expressed bam-GFP. The failure to form the GSC niche in HS-deficient mutants indicates that this process depends on HS modification of Dally. The requirement for HSPGs in the GSC niche appears to account, at least partially, for female sterility in many mutants of HSPG core protein or biosynthetic enzyme genes (Nakato et al., 1995; Kamimura et al., 2006).

The severe phenotype of sfl mutants suggests that other HSPGs may play a partially redundant role in this process. We examined the GSC phenotype of dally dlp double mutants but observed no enhancement of the dally phenotype (Fig. S1 C). It is possible that other HSPGs such as syndecan share this function, but the strong phenotype of dally mutants shows that Dally is a key player in this process.

We next evaluated Dpp signaling in mutant pupal ovaries. Corroborating the result in dally mutant adults (Fig. 1, D–E′), dad-lacZ reporter expression was markedly decreased in sfl mutant ovaries (Fig. S3, C and D). Thus, the loss of GSCs was caused by impaired Dpp signaling both in pupal and adult gonads. sfl mutations caused no detectable change in the expression of lamin C (Fig. S3, E and F), indicating that differentiation of the cap cells was not disrupted. Together, these results place dally and other HSPGs downstream of dpp and upstream of bam in the female GSC niche.

Ectopic expression of dally expands the GSC niche

To examine the effect of ectopic dally expression in GSC niche formation, we expressed upstream activation sequence (UAS)–dally using c587-Gal4 and monitored bam expression. c587-Gal4 drives expression in most somatic cell populations, including inner germarial sheath precursors that directly contact most germ cells (Song et al., 2007). In control ovaries, bam-GFP was expressed in posterior PGCs at the early pupal stage (Fig. 3 A). In striking contrast, ectopic dally completely eliminated bam-GFP expression in c587>dally pupal gonads (Fig. 3 B), suggesting that germ cells failed to differentiate. Similarly, no bam-GFP expression was detected in c587>dally adult ovaries (Fig. 3 D). Instead, they have an increasing number of GSC-like cells with a spectrosome. When cultured at 30°C, the penetrance of these phenotypes was 100%: all c587>dally germaria (n = 50) had >10 GSC-like cells and no bam-GFP signal, whereas no control germarium (n = 35) showed these abnormalities. In addition to expanding the area of undifferentiated cells in both the pupal and adult stages, c587>dally abnormally activated Dpp signaling in the posterior part of the germarium, as revealed by dad-lacZ staining (Fig. 3, F–G′). These results are consistent with the idea that in wild-type ovary, cap cell–specific dally expression spatially restricts Dpp signaling to define the physical space of the GSC niche.

Ectopic expression of dally expands the area of undifferentiated cells in the female GSC niche. (A and B) bam-GFP expression (green) in ovaries from c587-Gal4/+ (A) and c587-Gal4/UAS-dally (B) pupae. Anti-Hts and anti-Vas staining are shown in red and blue, respectively. (C and D) bam-GFP expression in ovaries from c587-Gal4/+ (C) and c587-Gal4/UAS-dally (D) adult germaria. The same markers were used as in A and B. (E and E′) Dpp signaling was monitored by dad-lacZ expression (green) in a c587-Gal4/+ adult germarium. Anti-Hts antibody stains the fusome (red). Strong dad-lacZ signals are seen in GSCs at the anterior edge of the germarium. (F–G′) Two examples of c587-Gal4/UAS-dally adult germaria in which ectopic dally induced abnormal expression of dad-lacZ in the posterior (arrowheads). Ectopic dally resulted in massive accumulation of GSCs throughout the germarium, but strong dad-lacZ expression was observed in a limited number of these cells, most frequently in the posterior. Anterior is to the left. Bars, 10 µm.

Ectopic expression of dally expands the area of undifferentiated cells in the female GSC niche. (A and B) bam-GFP expression (green) in ovaries from c587-Gal4/+ (A) and c587-Gal4/UAS-dally (B) pupae. Anti-Hts and anti-Vas staining are shown in red and blue, respectively. (C and D) bam-GFP expression in ovaries from c587-Gal4/+ (C) and c587-Gal4/UAS-dally (D) adult germaria. The same markers were used as in A and B. (E and E′) Dpp signaling was monitored by dad-lacZ expression (green) in a c587-Gal4/+ adult germarium. Anti-Hts antibody stains the fusome (red). Strong dad-lacZ signals are seen in GSCs at the anterior edge of the germarium. (F–G′) Two examples of c587-Gal4/UAS-dally adult germaria in which ectopic dally induced abnormal expression of dad-lacZ in the posterior (arrowheads). Ectopic dally resulted in massive accumulation of GSCs throughout the germarium, but strong dad-lacZ expression was observed in a limited number of these cells, most frequently in the posterior. Anterior is to the left. Bars, 10 µm.

HS biosynthesis is essential for male GSC niche formation

Our finding that Dally plays a role in the female GSC niche raised an important, interesting question: do HSPGs also regulate the male GSC niche? To address this question, we examined the male GSC phenotype in the HS-deficient mutants. In the anterior larval male gonad, the hub cells were surrounded proximally by GSCs (Fig. 4, A–A″; Xie et al., 2005). Cysts, which are large, differentiating germ cells that express Bam protein and bear branched fusomes, were located more distally. ttv mutant larval testes were substantially smaller than wild-type gonads largely because of a reduced number of germ cells. ttv mutation decreased the number of GSCs without affecting the number of hub cells (Fig. 4, B–D′; and Fig. S1 D). The hub cells directly contacted Bam-positive germ cells in the mutants, suggesting that ttv mutants fail to form or maintain a normal GSC niche and, consequently, that germ cells differentiate prematurely. These observations demonstrated that Drosophila HSPGs regulate the GSC niche in both sexes.

Dlp is required for the GSC niche in the male gonad. (A–D′) HS is required to form the male GSC niche. Testes from ttv heterozygous (A and A′) and homozygous (B–D′) third instar larvae stained with anti-FasIII (hub cells; red), anti-Vas (germ cells; blue), and anti-Bam (differentiating germ cells; green). (A″) Schematic diagram of the image shown in A. Hub cells, GSCs, Bam-negative differentiating germ cells, and Bam-expressing germ cells are shown in orange, blue, light blue, and green, respectively. (E and E′) Specific expression of Dlp in the hub cells. Adult testis stained with anti-Dlp and anti–E-Cad (hub cell marker). (F and F′) Expression of dally in the hub cells. A dally>GFP adult testis stained with anti-FasIII (hub cell). (G and G′) The male GSC niche in a dlp mutant. dlp heterozygous (G) and homozygous (G′) larval testes stained with anti-Hts (green) and anti–E-Cad (red) antibodies. Germ cells were labeled with anti-Vas antibody (blue). In the dlp mutant, the hub cells directly contact cysts that have a branched fusome (yellow arrowhead). Anterior is to the left. Bars, 10 µm.

Dlp is required for the GSC niche in the male gonad. (A–D′) HS is required to form the male GSC niche. Testes from ttv heterozygous (A and A′) and homozygous (B–D′) third instar larvae stained with anti-FasIII (hub cells; red), anti-Vas (germ cells; blue), and anti-Bam (differentiating germ cells; green). (A″) Schematic diagram of the image shown in A. Hub cells, GSCs, Bam-negative differentiating germ cells, and Bam-expressing germ cells are shown in orange, blue, light blue, and green, respectively. (E and E′) Specific expression of Dlp in the hub cells. Adult testis stained with anti-Dlp and anti–E-Cad (hub cell marker). (F and F′) Expression of dally in the hub cells. A dally>GFP adult testis stained with anti-FasIII (hub cell). (G and G′) The male GSC niche in a dlp mutant. dlp heterozygous (G) and homozygous (G′) larval testes stained with anti-Hts (green) and anti–E-Cad (red) antibodies. Germ cells were labeled with anti-Vas antibody (blue). In the dlp mutant, the hub cells directly contact cysts that have a branched fusome (yellow arrowhead). Anterior is to the left. Bars, 10 µm.

dlp regulates the male GSC niche

We next asked whether glypicans regulate the male GSC niche as in females. Both dally and dlp were specifically expressed in the hub cells (Fig. 4, E–F′); in particular, Dlp was detected at high levels. In dlp mutant gonads, the hub cells directly contacted cysts with branched fusomes (Fig. 4, G and G′), showing that GSCs are lost, as in the HS-deficient mutants. Based on the number of GSCs in a testis, the dlp phenotype was equivalent in severity to that of ttv mutants (Fig. S1 E). The number of GSCs was reduced only modestly in dally mutants, and the difference between dlp and dally dlp double mutants was not statistically significant. We concluded that Dlp plays a primary role in the male GSC niche and that Dally may have a minor redundant function.

The dlp mutant phenotype suggests that Dlp affects one or both of the pathways known to control the male GSC niche: JAK/STAT and/or Gbb signaling. Gbb is a member of the BMP family; because Dally serves as a coreceptor for another BMP, Dpp (Fujise et al., 2003; Akiyama et al., 2008), HSPGs may potentially regulate Gbb signaling. Upd, a ligand for the JAK/STAT pathway, is a heparin-binding protein (Harrison et al., 1998), so it is possible that Upd-JAK/STAT signaling is HS dependent in vivo. Further studies are needed to explore the molecular basis for male GSC control by HSPGs.

Mechanisms of glypican function in the GSC niche

Although it has been shown that secreted signaling molecules play fundamental roles as niche factors in many stem cell systems, the mechanisms by which these molecules can spatially control a restricted niche area are poorly understood. In this study, we showed that HSPGs are essential components of the GSC niches in the Drosophila gonads. We propose that HSPGs define the physical space of the niche by restricting the action range of growth factor signaling to the immediate vicinity of the niche cells.

Both Dally and Dpp are critical for making the female GSC niche. Previous studies have shown that Dally acts as a (canonical) coreceptor for Dpp in the developing wing (Fujise et al., 2003; Belenkaya et al., 2004; Akiyama et al., 2008). However, in the GSC niche, unlike typical HSPG coreceptors, dally is expressed in the dpp-expressing cells (cap cells), not in the receiving cells, suggesting that Dally activates signaling in trans. By its nature, trans signaling mediates signaling only to neighboring cells, providing a potential mechanism for contact-dependent Dpp signaling during GSC niche formation. Because Dally coreceptors on the cap cell surface and Dpp receptors on the surface of germ cells meet only at the contacting membranes of these cells, efficient signal transduction and thus the active field of Dpp signaling are limited to this area (Fig. 5 A). This idea is strongly supported by the observation that ectopic expression of dally can expand the GSC niche (Figs. 3 and 5 A″). Thus, the trans coreceptor activity of Dally could account for spatially restricted Dpp signaling.

Models for short-range Dpp signaling. (A) Cap cells (blue) express Dally on the cell surface (red), and germ cells express Dpp receptor (green). A dividing GSC is shown at the top, and two daughter cells are shown at the bottom. Dpp signal transduction occurs (ON) where these molecules meet (yellow). Dpp signaling is not activated in GSCs that do not directly contact the cap cells (OFF), leading to differentiation. (A′) In dally mutants, Dpp signaling is reduced, and GSCs are lost to differentiation. (A″) When dally is ectopically expressed in somatic cells (purple) adjacent to germ cells, Dpp signaling is activated at ectopic sites (yellow), resulting in expansion of the GSC niche and loss of differentiating cells. (B) Dpp (red circle) expressed in the cap cells is presented by Dally (red plus sign) on the surface of these cells, thus limiting Dpp distribution. (B′) In dally mutants, Dpp protein is either destabilized or diffuses away. (B″) Ectopic dally leads to the expansion of Dpp protein distribution.

Models for short-range Dpp signaling. (A) Cap cells (blue) express Dally on the cell surface (red), and germ cells express Dpp receptor (green). A dividing GSC is shown at the top, and two daughter cells are shown at the bottom. Dpp signal transduction occurs (ON) where these molecules meet (yellow). Dpp signaling is not activated in GSCs that do not directly contact the cap cells (OFF), leading to differentiation. (A′) In dally mutants, Dpp signaling is reduced, and GSCs are lost to differentiation. (A″) When dally is ectopically expressed in somatic cells (purple) adjacent to germ cells, Dpp signaling is activated at ectopic sites (yellow), resulting in expansion of the GSC niche and loss of differentiating cells. (B) Dpp (red circle) expressed in the cap cells is presented by Dally (red plus sign) on the surface of these cells, thus limiting Dpp distribution. (B′) In dally mutants, Dpp protein is either destabilized or diffuses away. (B″) Ectopic dally leads to the expansion of Dpp protein distribution.

In addition to its trans coreceptor activity, Dally may independently limit the size of the niche by retaining Dpp protein on the surface of the cap cells. In this model, Dally would serve as a membrane-bound anchor for Dpp, restricting the distribution of Dpp protein (Fig. 5 B). Future studies visualizing Dpp protein distribution will be required to test this possibility. Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that in addition to Dpp, Dally might affect signaling mediated by other HS-dependent factors. Although the signaling pathway controlled by Dlp is still unknown, Dlp is also expressed in the signal-sending cells (hub cells), suggesting that Dlp serves as a trans coreceptor in the male GSC niche.

HSPGs as a general regulator of the stem cell niche

The Mammalian Reproductive Genetics Database (http://mrg.genetics.washington.edu/) shows that most mouse and rat glypican genes are expressed in the testis with differential patterns. Recently, human glypican 3 has been established as a novel marker for testicular germ cell tumors (Zynger et al., 2006). These previous studies together with our observations suggest that glypicans have evolutionarily conserved roles in germline development and stem cell niches both in vertebrates and invertebrates.

Materials and methods

Fly strains

Detailed information for the fly strains used in this study is described in Flybase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/) except where noted. The wild-type strain used was Oregon R. Other strains used were dallyP2, a dally enhancer-trap line; dallygem and dallyΔ527, loss-of-function alleles of dally; dlp1 and dlpA187, null alleles of dlp; sfl9B4, a null allele of sfl; and ttv524, a null allele of ttv. c587-Gal4 (gift from T. Kai, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Republic of Singapore; Kai and Spradling, 2003) and UAS-dally were used to ectopically express dally. bam-GFP (gift from D. McKearin, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX; Chen and McKearin, 2003) and dally-Gal4 were used to monitor expression of bam and dally, respectively. dad-lacZ (gift from T. Tabata, University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan; Tsuneizumi et al., 1997) was used as a reporter for Dpp signaling.

Immunostaining

Antibody staining was performed according to standard procedures (Fujise et al., 2001). The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-Dlp (1:50; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), mouse anti–fasciclin III (FasIII; 1:50; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rabbit anti–β-galactosidase (1:500; Cappel), mouse anti–Hu-li tai shao (Hts; 1:5; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rat anti-Bam (1:300; gift from D. McKearin), rat anti–epithelial cadherin (E-Cad; 1:10; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; Song et al., 2002; Tazuke et al., 2002; Le Bras and Van Doren, 2006), mouse anti–lamin C (1:10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), mouse anti-Dpp (1:5; R&D Systems), rabbit anti-GFP (1:500; Invitrogen), and rat anti-Vasa (Vas; 1:50; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). For anti-Dpp staining, we used Can Get Signal Solution B (TOYOBO) as antibody dilution solution. Stained ovaries and testes were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and imaged with a confocal microscope (TCS SP5; Leica).

Phenotypic analysis of mutant gonads

To analyze the differentiated status of germ cells, spectrosomes and fusomes were stained with anti-Hts antibody (Lin et al., 1994). The spectrosome is a spherical structure in GSCs and cystoblasts. Further differentiated germ cell cysts are characterized by a branched fusome.

To examine the number of GSCs, ovaries were dissected from adult female flies at 2 d after eclosion and stained with anti-Vas and anti-Hts antibodies. The GSCs were identified as spherical-shaped Vas-positive cells that were in direct contact with the cap cells and had a spectrosome. To assess the empty germarium phenotype, the number of germaria with no Vas-positive cells was counted. To analyze the age dependency of the dally mutant phenotype, ovaries were dissected from adult females at the indicated day after eclosion, and the number of ovarioles bearing at least one developing egg chamber was counted.

To examine expression of bam, the differentiation marker of germ cells, in mutant PGCs, ovaries with the indicated genotypes were dissected at early pupal stage and stained with anti-Vas and anti-Hts antibodies. bam expression was examined by either bam-GFP (a GFP reporter gene for bam transcription) or anti-Bam antibody. The most anterior PGCs were defined as Vas-positive cells located at the distal-most part of a developing ovariole in direct contact with the somatic niche cells. The number of ovarioles in which the most anterior PGCs showed bam-GFP expression or anti-Bam staining was counted.

To evaluate the effect of dally mutations on Dpp signaling in the GSC niche, ovaries were dissected from adult females bearing a dad-lacZ transgene and stained with anti–β-galactosidase, anti-Vas, and anti-Hts antibodies. The number of GSCs with detectable dad-lacZ expression was counted.

To assess the effect of ectopic expression of dally on the GSC niche, c587-Gal4/UAS-dally; bam-GFP animals were cultured at 30°C. Adult ovaries were dissected and stained with anti-Vas and anti-Hts antibodies. The number of germaria in which no bam-GFP signal was detected in Vas-positive cells (germaria without bam-GFP) was counted. Also, Vas-positive, round-shaped cells with a spectrosome were referred to as GSC-like cells, and the number of germaria with >10 GSC-like cells was counted.

To count the number of GSCs and hub cells in mutant males, testes were dissected from late third instar larvae and stained with anti-Vas, anti-Hts, and anti–E-Cad antibodies. The hub cells were identified as E-Cad–positive cells at the anterior edge of the testes. GSCs were identified as spherical-shaped, Vas-positive cells in direct contact with the hub cells that had a spectrosome. To assess Bam expression in male GSCs, testes were stained with anti-Vas, anti-FasIII, and anti-Bam antibodies, and the number of Bam-positive GSCs was counted. Two independent criteria were used to evaluate the differentiation status of male GSCs: Bam expression and branched fusomes. It should be noted that Bam expression in the male GSC niche is not necessarily a direct readout for the lack of BMP signaling, as it is in the female. The χ2 and t tests were used to calculate significance.

Microscope image acquisition

Secondary antibodies used were conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, 546, and 633 fluorochromes (Invitrogen). Stained samples were mounted with Vectashield and observed at room temperature. Images were acquired using a TCS SP5 confocal microscope with Plan-Apochromat 20× NA 1.00 and 63× NA 1.20 lenses (Leica) and with acquisition software (Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence; Leica). Acquired images were processed with Photoshop CS3 (Adobe).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows a quantitative summary of the GSC phenotype observed in mutants for dally, dlp, sfl, and ttv. Fig. S2 shows expression of Dpp protein in dally mutant ovarioles. Fig. S3 shows expression patterns of dally in early pupal ovaries and staining for dad-lacZ, bam-GFP, and lamin C in sfl mutant ovaries.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to D. McKearin, T. Kai, T. Tabata, the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, and the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks and reagents. We thank C. Kirkpatrick for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HD042769 to H. Nakato and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas to S. Kobayashi.

References

- Bam

bag of marbles

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- Dlp

Dally-like

- Dpp

decapentaplegic

- E-Cad

epithelial cadherin

- FasIII

fasciclin III

- Gbb

Glass-bottom boat

- GSC

germline stem cell

- HS

heparan sulfate

- HSPG

HS proteoglycan

- Hts

Hu-li tai shao

- JAK/STAT

Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription

- PGC

primordial germ cell

- sfl

sulfateless

- ttv

tout-velu

- UAS

upstream activation sequence

- Upd

Unpaired

- Vas

Vasa